EUROPEAN DEVELOPMENT AID AS A

TOOL TO MANAGE MIGRATION FROM

AFRICA: AN EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

Aantal woorden: 15263

Stamnummer : 01809812

Promotor: Prof. Dr. Ilse Ruyssen

Masterproef voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van:

Master in de bedrijfseconomie: bedrijfseconomie

Deze pagina is niet beschikbaar omdat ze persoonsgegevens bevat.

Universiteitsbibliotheek Gent, 2021.

This page is not available because it contains personal information.

Ghent University, Library, 2021.

iii

Samenvatting

In 2015 worstelde de Europese Unie met de gevolgen van een groeiende instroom van asielzoekers vanuit het Midden Oosten en Afrika. Als reactie op deze ‘vluchtelingencrisis’ werd er een

internationale top gehouden in november 2015 op Malta. Staatshoofden van de Europese Unie en van verschillende Afrikaanse landen bespraken hier nieuwe mogelijkheden tot samenwerking tussen beide regio’s rondom het thema van migranten. Het eindresultaat van deze top was de lancering van een nieuw fonds: het EU Noodfonds voor Afrika (EUTF).Het doel van dit fonds was de onderliggende oorzaken van migratie te adresseren door het sturen van gerichte ontwikkelingshulp en door samenwerking met lokale actoren. Volgens deze logica zou illegale migratie terug kunnen worden gedrongen. Deze masterproef onderzoek de impact van Officiële Ontwikkelingshulp (ODA), zoals de hulp vanuit het noodfonds, op de aantallen asielzoekers vanuit Sub-Sahara Afrika richting de EU tussen 2008 en 2018. Het doel van dit onderzoek is om vast te stellen –door middel van een Poisson Pseudo Maximum Likelihood Model (PPML) – of ODA daadwerkelijk leidt tot minder asielaanvragen en om de effecten van het noodfonds op asielaanvragen te isoleren. Op deze manier draagt de masterproef bij aan de literatuur over migratie en ontwikkeling(hulp) en aan beleid door aan te tonen of ODA effectief migratiestromen vermindert. Eerder onderzoek geeft een wisselend beeld, echter het meeste recente werk laat zien dat ODA leidt tot lagere migratiestromen. Het huidige onderzoek bevestigt deze conclusies, aangezien het bewijs vindt voor het feit dat ODA vanuit de EU leidt tot minder migratie vanuit Afrika naar de EU. Bovendien toont het aan dat het noodfonds de onderliggende oorzaken van migratie weet aan te pakken

iv

Abstract

In 2015, Europe was struggling to deal with the growing number of asylum seekers that arrived to the European Union from the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa. As a reaction to this ‘refugee crisis’, a summit was held in November 2015 in Valletta, Malta. Leaders of the European Union and Sub-Saharan countries discussed new avenues for cooperation between both regions with a focus on migration management. The end-result of the Valletta Summit on Migration was the launch of a new fund: the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF for Africa). The objective of the fund was to address the root causes of migration through targeted development aid and cooperation with local governments. In that way, illegal migration could be reduced. This thesis researches the impact of Official Development Assistance (ODA) such as the aid given through the EUTF on the amount of asylum applications from Sub-Saharan Africa to the European Union between 2008 and 2018. The aim is to determine - by using a Poisson Pseudo Maximum Likelihood Model - whether ODA is effective in decreasing the levels of migration for the whole period and to isolate effects of the EUTF on migration. In this way, this thesis adds to the academic literature and policy by showing whether ODA is an effective tool for tackling the root causes of migration. Literature on the topic provides mixed empirical evidence; however, work that is more recent indicates that ODA leads to fewer asylum applications. This thesis underlines these conclusions, as it finds that aid given by European countries to Sub-Saharan Africa leads too lower levels of asylum applications. Furthermore, the current research shows how the EUTF is effective in decreasing migration from the countries that are part of the EUTF-framework.

v

Preface

Coming from a humanities background, starting a second master in business economics was a big leap. After one and a half year, I can say that I am happy I took that step, because of all the new skills and knowledge I picked up at Ghent University. Writing this thesis would not have been possible without the courses taken in these three semesters. Especially the course Research Methods in Corporate Finance proved to be vital. Moreover, I thank the University for allowing me to write about this topic, as it is something I am passionate about and hope to continue to work on this topic in the future.

I thank my family for putting up with me these last days and helping me with valuable advice and shelter. In addition, I would like to thank my girlfriend Joey who always inspires me to push further. Finally, I would like to thank my supervisor dr. prof. Ilse Ruyssen. I immensely appreciate the time she took to answer my questions even on short notice. Dr. Prof. Ruyssen pointed me in the right

direction when I had questions I look forward to a new chapter after university.

vi

Contents

Samenvatting ... iii Abstract ... iv Preface ... v Contents ... vi Abbreviations ... viiList of Tables ... vii

List of Figures ... vii

List of Graphs ... vii

1. Introduction ... 1

Relevance ... 2

2. Literature Review ... 5

Neoclassical Theories of Migration ... 6

Alternative Migration Theories ... 8

Development and Migration: An inverted-U ... 9

Evidence for an Inverted-U relation ... 10

Development aid and migration ... 11

3. Hypothesis ... 14

4. Sample and Descriptive Statistics ... 16

Sample ... 16 Descriptive statistics ... 17 5. Methodology ... 24 Econometric Specification ... 24 6. Results ... 29 Robustness Checks ... 37 Aid equation ... 37

EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF) ... 39

Analysis of EUTF Effectiveness ... 41

Limitations ... 44 7. Conclusion ... 44 Hypotheses ... 46 Other findings... 47 8. Works Cited ... 48 9. Appendix ... 53

Appendix 1: Overview of Variables ... 53

vii

Appendix 3: List of countries ... 56

Abbreviations

ODA = Official Development Assistance EU = European Union EUTF = EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa OECD = Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development PPML = Poisson Pseudo Maximum Likelihood GDP = Gross Domestic ProductList of Tables

Table 1: Theory overview ... 5Table 2: Share of zeros in the dependent variable ... 16

Table 3: Amount of asylum applications received by countries European Union ... 18

Table 4: Ranking asylum application receiving European Countries and Sub-Saharan Africa countries of origin ... 21

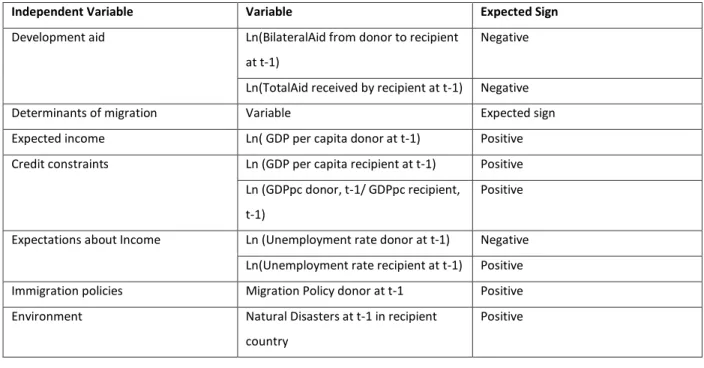

Table 5: List of variables with their expected sign ... 26

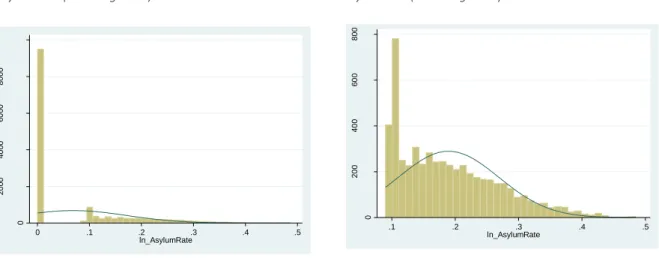

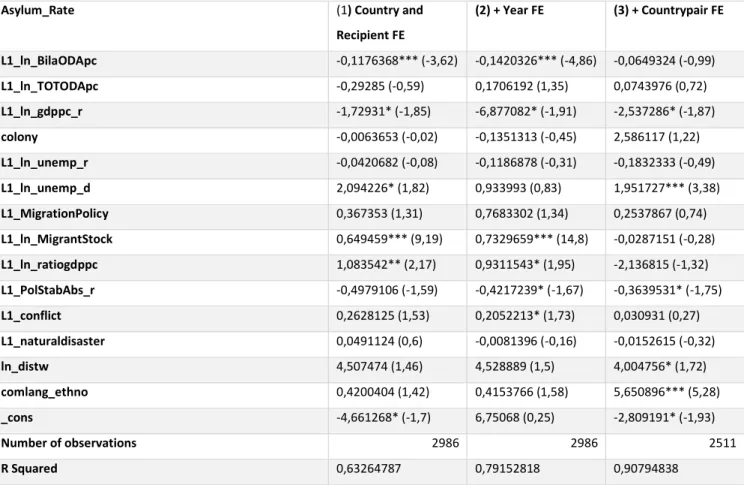

Table 6: Linear regression ... 31

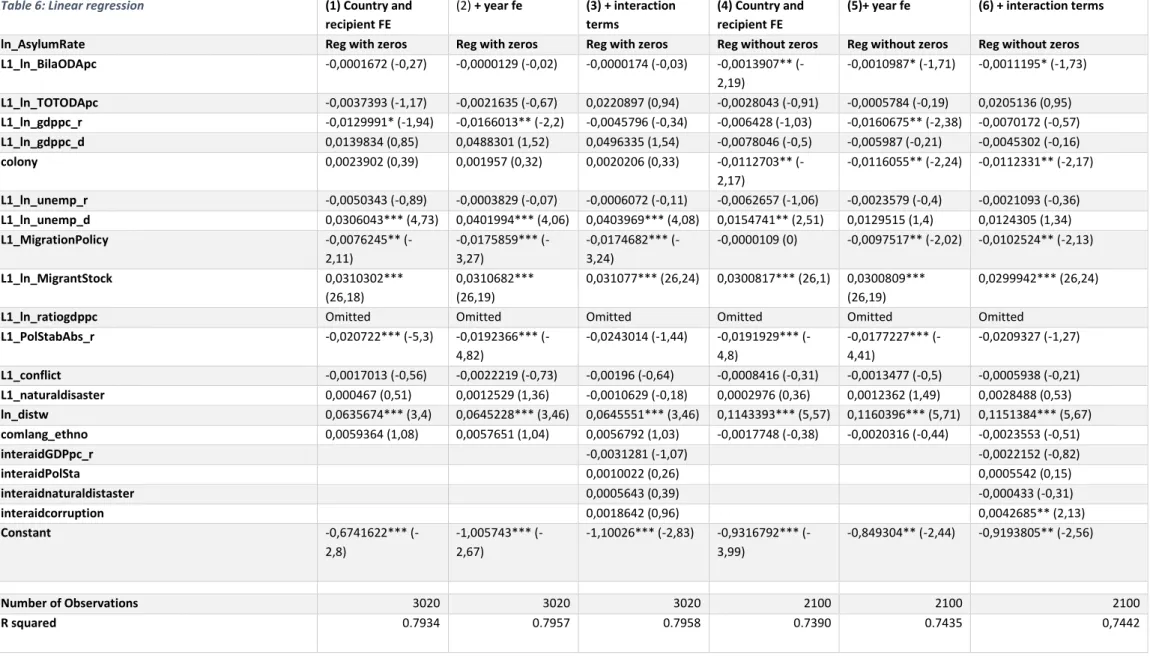

Table 7: outcomes regression using official immigration data ... 32

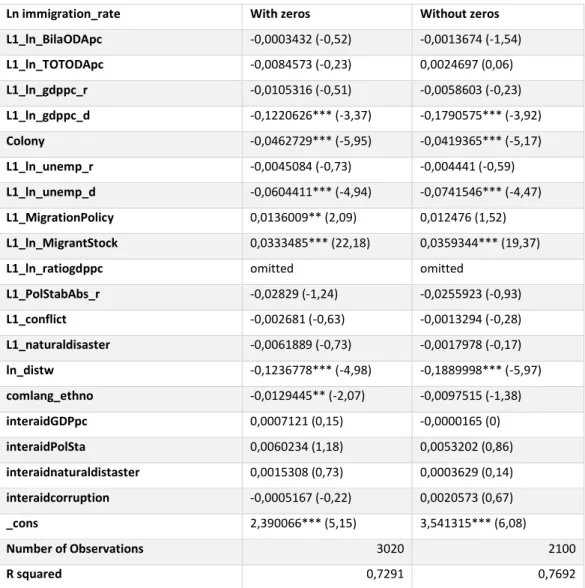

Table 8: PPML regression ... 33

Table 9: PPML regression + interaction variables ... 36

Table 10: Aid equation ... 38

Table 11: Method 1;Interaction and dummy variables ... 41

Table 12: Method 2; Split Sample ... 43

List of Figures

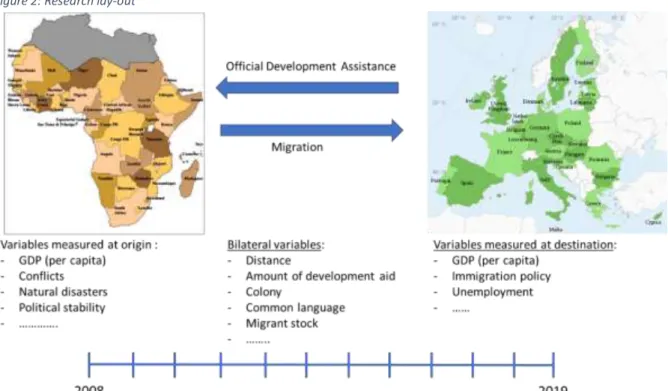

Figure 1: Allocation of EUTF funds according to objective ... 15Figure 2: Research lay-out ... 25

Figure 3: EUTF Countries ... 40

List of Graphs

Graph 1: Average values asylum applications Sub-Saharan Africa countries and aid received ... 19Graph 2: Average asylum applications received and aid provided by European Countries ... 19

Graph 3: Preliminary relation between Asylum Rates and Total Aid ... 20

Graph 4: Relation GDP per capita and Asylum Rate (excluding zeros) ... 21

Graph 5: Relation GDP per capita and Asylum Rate ( including zeros) ... 22

Graph 6: Split sample Log asylum rate Sub-Saharan Africa countries high GDP ... 22

Graph 7: Split sample Log asylum rate Sub-Saharan Africa countries low GDP ... 23

Graph 8: Distribution of the dependent variable AsylumRate (excluding zeros) ... 29

Graph 9: Distribution of the dependent variable AsylumRate (including zeros) ... 29

1

1. Introduction

The past years we have seen the images of migrants trying to cross into Europe on small boats that often do not reach the mainland. These images of the so-called refugee crisis are confrontational and led to a restructuring of Europe’s approach to illegal migration. The crisis experienced its peak around 2015 and 2016. The influx of migrants from the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa took a toll on the ability of countries to harbor and welcome these migrants. To highlight the task European leaders faced: in total 1.3 million people filed for asylum in the European Union in 2015. Spurred leaders of the European Union to find a way to curb migration (European Parliament, 2018). Besides the group of people that fled the conflicts in Syria and Afghanistan, the surge of violence in Sub-Saharan countries such as South Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea and Nigeria also resulted in a growth of asylum seekers from these countries (Frontex, 2019). As a reaction to this ‘refugee crisis’, a summit was held in November 2015 in Valletta, Malta. Leaders of the European Union and Sub-Saharan countries discussed new avenues for cooperation on migration management between both regions. The end-result of the Valletta Summit on Migration was the launch of a new fund: the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF for Africa). The objective of the fund was to address the root causes of migration through targeted development aid and cooperation with local governments. In that way, illegal migration could be reduced.

The idea that illegal migration can be managed through development aid is not new. For many years, policy makers have tried to curb migration through development aid. Already in 1947, research by Julius Isaac suggested that migration could be addressed through kick starting industrialization in the sending countries. In addition, the International Labor Organization (ILO) recommended government to bring “capital and technical knowledge” to developing countries through ‘multilateral and bilateral cooperation’ (Clemens, 2014; ILO 1976). Through sending development aid, ILO argued, the necessity to migrate would be removed. Thus, development, or rather the lack of it, was a so-called root cause of migration. Furthermore, the European Commission views economic development as the way through which illegal migration can be halted (EC 2005). The Belgian government follows a similar approach to migration. For instance, they support projects that aim to take away the incentives for migration through projects aimed at fostering economic development. Belgium even organized the first ever International Forum on Migration and Development in 2007, a discussion platform that is aimed at the connection between development and migration. The EUTF’s objectives of addressing the root causes of migration through bringing economic development is consistent with earlier policies.

The notion that an increase in economic development leads to a decrease migration is based on the assumption that people are less likely to leave their home if they have more economic resources at

2 home (Clemens 2014). Furthermore, neoclassical economist argued that the force driving migration is the difference in wages between countries (Massey et al., 1993). They would have to give up the security of their income and work at home in exchange for the insecurity that comes with migrating (il)legally to Europe. This supposed relationship between migration and development has been a topic of discussion within the migration literature for several decades. In spite of the many studies, or exactly because of that, the academic literature shows a very complex image of the relationship between migration and development where the correlation is not always linear (either positive or negative). Many scholars have actually shown the existence of a so-call ‘inverted-u relation’ between development and migration. Thus, development actually leads to more migration for the poorest countries. Only when a certain threshold of development has been met, migration actually does decrease. One of the reasons for this inverted-u relation is that economic development gives

prospective migrants the resources to undertake the journey. In contrast to the connection between development and migration, the effectiveness of development aid (Official Development Assistance; ODA1) as a tool for managing migration is far less documented. The few studies that researched this question also show a mixed image of the exact relation between development aid and migration (Berthélemy, Beuran & Maurel 2009; Belloc 2014; Gamso & Yuldashev 2018; Lanati & Thiele 2018). This master thesis has as its goal to provide more insight in the relation between ODA and migration. In doing so I will look at the impact the EUTF for Africa has had. Thus, I will also contribute to policy-making as this thesis shows whether policies aimed at addressing migration through sending development aid are effective. Finally, I will look to answer the question: How does European

Development Aid affect migrant flows from Sub-Saharan Africa?

In this paper, I argue that Bilateral Aid is effective in decreasing levels of migration. Furthermore, I find that even though countries that receive aid via the EUTF-framework record higher levels of migration in general, that the aid allocated to those countries is more effective in decreasing levels of migration. Thus, this shows that the policy objectives of the EUTF are met. Furthermore, as GDP at the country of origin increases, the effect of aid on decreasing migration becomes stronger

Relevance

The relevance of this paper is twofold. Firstly, it adds to the academic literature on the relation between migration and economic development. Next to this, it follows more recent work on the effect of development aid on migration. This is done through researching the question that is prevalent within the EU: how to manage (illegal) migration effectively. This paper tries to give an

1 Official Development Assistance (ODA) is “government aid that promotes and specifically targets the

3 answer by looking at the effectiveness of development aid, through programs such as the EUTF, in curbing migration. To my knowledge, this thesis is the only one until now that specifically looks at the impact of the EUTF. Other scholars looked at the relation between all Development Aid donors and recipients rather than limiting their research to on region. Research before 2015 find that

Development Aid has a reinforcing effect on migration levels, while the most recent work finds the opposite. This thesis adds to this body of literature through examining whether something has fundamentally changed in the effect of development aid on migration.

Moreover, there has been little research into the effectiveness of funds like the EUTF for Africa in diminishing migrant flows. Thus, this thesis adds to the existing theories on migration, which say the relation between development and migration resembles an inverted-u. An overview of all theories on migration can be found in the literature review. Secondly, the relevance of the thesis lies in the implications for policy. Even though the relation between development and migration has been studied a lot, policy makers tend to rely on research that says that more development/ more

economic resources in countries of origin will lead to fewer migrants. However, as mentioned, many researchers argue the opposite or find a more nuanced relationship. I will further expand on this in the literature review. Finally, in contrast to previous studies, this paper uses bilateral flow data, both on migration (asylum applications) and on bilateral development aid. This allows for more specific conclusions about the impact of restrictive migration policies on asylum applications. Moreover, it permits controlling for Multilateral Resistance to Migration (MRM) (Beine, Bertoli & Fernandez-Huertas Moraga, 2016). Finally, trough using bilateral flow data on asylum applications I can directly see whether the goal of the EUTF (to effectively manage illegal migration flows and tackle root causes of migration) has been effective.

The data used covers Bilateral Aid and Asylum flows between all 28 countries from the European Union (EU) and 50 Sub-Saharan African countries. The period under investigation is from 2008 until 2018. This makes it possible to see a possible change in the effect of Development aid after the implementation of the EUTF.

This thesis uses a Poisson Pseudo Maximum Likelihood Model to regress all variables and to account for MRM. Here, I follow the practitioner’s guide by Beine, Bertoli & Fernandez-Huertas Moraga (2016) who demonstrate clearly how using this model is an effective method for gravity models of international migration. Furthermore, PPML is able to account for the large share of zeros in the dataset. By adding origin, destination and time fixed effects this model is able to account for shocks in time not accounted for by other control variables. Finally, through adding an appropriate set of control variables and later adding interaction variables, the model is able to account for a large share of the variation in the Asylum Rates.

4 The layout of this thesis is as follows. Firstly, the development of academic scholarship on migration will be outlined. Through an overview of theories of migration, I will be able to select the relevant control variables for my model. In addition, it gives an idea of the complexity of the relation between development and migration. Following the literature review, I will present the hypotheses. After an explanation of the research design, sample collection and econometric approach, the results will be presented. Finally, this thesis ends with a discussion of possible shortcomings, conclusions, and implications for future research and policy. The discussion will also focus on the effectiveness of Europe’s most recent policy to manage illegal migration: the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF). In light of the regression outcomes, is the way the EUTF is setup likely effectively address migration in source countries? Its first objective is to increase economic development, which

according to previous research does not decrease migration. However, through the inclusion of good governance projects and the improvement of public services the EUTF is likely to address root causes for migration successfully.

5

2. Literature Review

Many theories have been developed in order to explain why migration occurs. These studies have had different spatial contexts, they have conducted research in different times and naturally they have led to the development of different theories. This section will list the most important theories on migration and give an overview of the causes of migration, which different scholars have identified. Secondly, I will look at how different scholars have linked economic development and migration. Finally, I will give an overview of the most recent literature that has looked at how development aid has influenced levels of migration.

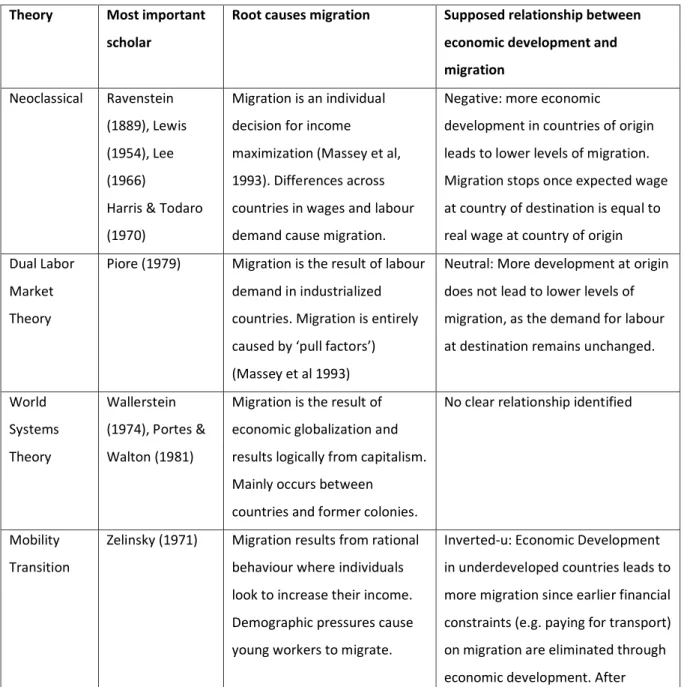

Table 1: Theory Overview

Theory Most important

scholar

Root causes migration Supposed relationship between

economic development and migration

Neoclassical Ravenstein (1889), Lewis (1954), Lee (1966)

Harris & Todaro (1970)

Migration is an individual decision for income maximization (Massey et al, 1993). Differences across countries in wages and labour demand cause migration.

Negative: more economic

development in countries of origin leads to lower levels of migration. Migration stops once expected wage at country of destination is equal to real wage at country of origin Dual Labor

Market Theory

Piore (1979) Migration is the result of labour demand in industrialized countries. Migration is entirely caused by ‘pull factors’) (Massey et al 1993)

Neutral: More development at origin does not lead to lower levels of migration, as the demand for labour at destination remains unchanged.

World Systems Theory Wallerstein (1974), Portes & Walton (1981)

Migration is the result of economic globalization and results logically from capitalism. Mainly occurs between

countries and former colonies.

No clear relationship identified

Mobility Transition

Zelinsky (1971) Migration results from rational behaviour where individuals look to increase their income. Demographic pressures cause young workers to migrate.

Inverted-u: Economic Development in underdeveloped countries leads to more migration since earlier financial constraints (e.g. paying for transport) on migration are eliminated through economic development. After

6

Neoclassical Theories of Migration

Already in 1885, Ernst Ravenstein looked at the root causes for migration to Great Britain. Later in 1889, he conducted a similar study for twenty European Countries. Through an early version of the gravity model he identified several laws of migration, which have remained impactful throughout the last century. According to Ravenstein migration is fueled by an innate desire ‘to better themselves in material terms’ (Ravenstein 1889). Thus, people move to countries where there is more demand for labor. Furthermore, he showed that people choose those countries that are closest to their own.

Subsequent authors build their own theories on these laws of migration. For example, Lee (1966) expands on Ravenstein’s work and proposes better-defined laws of migration. Both authors identify poverty and migration as causes of migration and note that distance plays an important role in the destination for migration. Lee also wrote the first well-defined definition of migration, which I will also use in this thesis.

“Migration is defined broadly as a permanent or semi-permanent change of residence. No

restriction is placed upon the distance of the move or upon the voluntary or involuntary nature of the act, and no distinction is made between external and internal migration” (Lee 1966)

However, in contrast to Lee, this thesis will only look at the external component of migration. This means that I will not look at migration movements within countries but only to those migration movements from African countries towards Europe.

The distinguishing fact about Lee’s analysis of migration is the identification of push (factors associated with area of origin) and pull (factors associated with area of destination). However, prospective migrants are often not fully aware of the actual (labor) conditions at their desired destination. They thus base their migration decision on expected economic conditions in the country of destination (Lee 1966). As Lee puts it: “is not so much the actual factors at origin and destination

as the perception of these factors which results in migration”

Overall, the (expected) benefits at destination must outweigh the costs if immigration and must lead to an improvement from the conditions at home. Furthermore ‘intervening obstacles’ play an

Presence of a diaspora from an African country in possible countries of destination lead to higher level of migration to that particular country.

transitioning into middle-income country more development leads to less migration

7 important role in the decision to migrate or not. These intervening obstacles include actual walls or fences, immigration policies of countries of destination, distance between countries of origin and destination and monetary costs related to migration.

These papers form the foundation of the neoclassical theory of migration, which states that

differences in wages and international labor demand fuel migration. The decision to migrate is then result of disparities in wages in countries of origin and destination. The neoclassical theory of migration was also influenced by Lewis (1954) and Ranis & Fei (1961) who look at the shift of labor from the agricultural to the industrial sector. They identified how the surplus of labor in the agricultural sector and the shortage of labor in the industrial sector led to migration movements from rural areas to industrial zones. Ranis & Fei identified how surplus laborers in the agricultural sector move to the industrial sector until the differential in labor supply levels out. The same mechanism applies to migration, as demonstrated by Harris & Todaro (1970). Rural-urban migration occurs as long as expected wages at destination are higher than at origin. They state that

‘prospective migrants behave as maximizers of expected utility’. Thus, migration is a result of imbalances in the global labor market, which can be reversed by supporting the labor market at country of origin. As long as equilibrium wages at country of origin are lower than in the country of destination, migration flows will continue to take place. This idea is the foundation of many immigration policies as Massey et al. (1993) and Castles (2008) demonstrate. These led to the implementation of policies aimed at leveling wage differences and increasing development at countries of origin.

Yet Todaro (1969) and Harris & Todaro (1970) noted that rural-urban migration continued regardless of high unemployment rates in the urban centers. They explained this seemingly contradictory phenomenon through highlighting how prospective migrants look at the expected wage at destination. This expected wage is a function of the real wage and the probability of finding a job (Todaro, 1969). Thus, migrants perform a discounted present value calculation where they look at the probability of finding employment at destination and the real wages at destination (Todaro, 1969). Even if migrants cannot find work in the short term, relocating to an urban environment might lead to higher income in the long term. Migration is then an investment into human capital (Sjaastad, 1962). Borjas (1989) extended Harris and Todaro’s model of rural-urban migration to an international context. He developed a model for migration where every person is a potential migrant and is constantly evaluating whether to migrate to a particular host country or stay in their country of origin. Individuals base their decision through “[…] considering the values of the various alternatives,

8

and choosing the option that best suits them given the financial and legal constraints that regulate the international migration process.”

The constraints Borjas refers to are not only financial costs, but also refer to immigration policies in country of destination.

However, the neoclassical theory of migration has been criticized for several reasons. Firstly, it only looks at the labor market as an explanatory factor for migration. Secondly, it assumes that individuals are rational actors and therefore that prospective migrants possess all the information on the

destination’s labor market (Ruyssen, 2013). Despite its intuitive character and its impact on public thought and policy, neoclassical theory is therefore not sufficient to explain the present migration flows. Borjas (1989), as demonstrated, made a start in tackling these issues, by adding more explanatory variables that influence the decision to migrate. Harris & Todaro also did this through the inclusion of the probability of employment and the expected wage at destination in their formula of migration. Yet, neoclassical economic theory is unable to explain fully the occurrence and size of migrant flows.

Alternative Migration Theories

Several theories attempt to address the aforementioned critiques. Firstly, Michael A. Piore

developed the dual market labor theory (1979). In contrast to the neoclassical theory, the dual labor market theory argues that migration is not the result from rational decisions by individuals (migrants) but is instead demand-driven (Massey et al., 1993). Dual labor market theory identifies the need for foreign workers at the destination/ developed markets as the driving force behind migration (Piore, 1979). Developed countries have an insatiable demand for workers, which migrants from

underdeveloped countries supply. As an example, Piore uses jobs that are less favorably viewed and are more unlikely to be occupied by laborers from the host country. In order to fill the positions, employers will look for migrants to occupy those jobs. According to Piore, migrants will also accept these lowly paid jobs. Thus, wage differentials are no longer the sole explanatory factor for

migration.

Secondly, the World Systems Theory, based on Wallerstein’s (1974) work, links migration to the penetration of capitalist economic systems into underdeveloped countries (Mabogunje, 1970; Portes & Walton, 1981; Petras, 1981; Castells, 1989; Sassen, 1988, 1991; Morawska, 1990). From the 19th century, the capitalist market system gained prominence, first in Europe first and then was diffused to other parts of the world (Wallerstein, 1974). As ‘elites’ at the core of the system search for profit, materials and labor in the ‘periphery’, local markets are ‘disrupted’, which lead to migration patterns

9 from the periphery to the core (Massey et al., 1993). One of the first authors to use the term

‘systems’ was Nigerian scholar Akin Mabogunje (he referred to ‘General Systems Theory’). He noticed that formerly rural areas in Africa were being affected by the migration of their residents to urban areas. Increasing economic prosperity and connection to the core (through colonization) made rural areas more vulnerable to changes in the economy in the core. The increasing connection with the core leads to people being more prone to move there, as they are more aware of what opportunities lie there. (Mabogunje, 1970). It therefore increases individuals’ relative deprivation and migration aspirations. As the prosperity of the core becomes more visible to the periphery relative deprivation (e.g. people’s own economic situation compared to the city or Europe) increases. Even though the economic situation of those in the periphery also increase, the exposure to possibilities for further economic growth in Europe fuels their aspirations to leave their own (often stable)2 economic situation behind and migrate towards Europe (UNDP, 2019).

Development and Migration: An inverted-U

In line with neoclassical economic theory’s emphasis on the role of wage disparities as the decisive factor in the decision to migrate, many governments have targeted their migration policy at increasing development in countries of origin. Since economic development decreases wage disparities, people would be less likely to migrate (Julius, 1947; ILO, 1984; Barroso, 2005; EC, 2008; Clemens, 2014). However, this relationship did not hold in several empirical studies conducted in the last decennia. Therefore, scholars devised a theory that better fit the empirical evidence they found.

One of the earliest scholars to find a differently shaped correlation between development and migration was Wilbur Zelinsky. Already in 1971, Zelinsky developed the Mobility Transition Theory. He postulates that the first phases of economic development results in an increase in migration rather than a decrease. The first phases of economic development are accompanied by a

demographic transition where mortality rates fall, but fertility stays high (Zelinsky, 1971). This leads to a growing population in a tight job market. Therefore, even if on a country level, GDP is rising, the population growth is paired with rising unemployment. Even though wages rose initially, the

presence of high unemployment signifies a push factor on individuals to migrate to countries where there is a higher demand for labor. Furthermore, as income rises, previous intervening obstacles, such as the ones Lee (1966) identified, are overcome. For instance, the costs associated with moving abroad are no longer a constraining factor as wages in country of origin rise (Clemens, 2014).

2 The recently published UNDP report “Scaling Fences Voices of Irregular African Migrants to Europe” shows

10

Evidence for an Inverted-U relation

As described above, the relationship between economic development and migration in academic literature is complex and is contingent on many factors. Scholars have not reached consensus nor have they developed one comprehensive theory. As Clemens (2014) demonstrates in his extensive literature review, studies that use time series have inconsistent findings. For example, Vogler & Rotte (2000) establish an inverted-u relationship between development in Sub-Saharan Africa and

migration to Germany. However, both Mayda (2010) and Naudé (2010) do not find a correlation between the two variables. Negative relations are also found, for example by Clark, Hatton and Williamson (2004), Bertoli and Fernandez-Huertas (2012) and Ortega and Peri (2013), when using fixed effects.

The majority of studies, however, identify a positive relationship or an inverted-u relation between development and migration. Even though the scope of their research differs, Letouzé et al (2009) in their research of migration to developing countries find similar results as Ortega and Peri (2009) in their study of migration to developed countries. Both of them find an inverted-u relation for development at origin. Until countries reach a threshold of around 7,000-8,000 USD in income per capita, an income rise results in higher levels of migration (Clemens, 2014). Furthermore, they show how GDP at destination is positively related to migration in that country. This is intuitive as migrants are more likely to migrate to those countries where income is higher. Next to using GDP as an indicator of development, De Haas (2010) uses the Human Development Index (HDI) to establish whether higher human development leads to more migration. In his study, he finds a similar inverted-u relationship.

Scholars offer many explanations as to why the inverted-u relationship exists next to the

demographic transition that Zelinsky highlights (Clemens, 2014). Firstly, so called credit constraints are lifted when income increases in origin countries. Migration from origin to destination needs to be financed. Migrants need to pay for transport, smugglers, official documents (passports, visa) and others (McKenzie, 2007; Salt & Stein, 1997). Secondly, information asymmetry is reduced through economic development (Massey, 1988). Following the migration of a small group of people from e.g. the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) toward Belgium, people that stayed behind in the DRC will have access to more information about the economic prospects and avenues for migration to

Belgium. This is the result of increased information networks between the country of destination and origin. As more and more people migrate to Belgium from the DRC, and information arrives about the economic success of that endeavor, more people will wish to follow that example. However, this positive relation only continues until the total stock of DRC nationals in Belgium reaches a threshold,

11 after which the existence of such a diaspora will be negatively related to the propensity to migrate since wages will decrease with every extra migrant (Epstein, 2008).

The third argument is in line with the World Systems Theory. An increase in economic development will lead to ‘structural dislocation’ of rural workers (Flahaux & De Haas, 2016). As economic

development occurs, developing countries transition from agricultural societies to urban societies. This change brings along a disruption of the periphery, leading people to move to urban areas and abroad (Zelinsky, 1971; Massey, 1988).

A fourth explanation is that economic development is distributed unevenly across the population. The portion of the population that does not reap the benefits of increased prosperity do witness the increased welfare of their compatriots. Their ‘relative deprivation’ increases, which leads to higher levels of migration (Stark & Taylor, 1991). Furthermore, as more people migrate, remittances to families at home increase. Those families that receive remittances see their income rise,3 whereas the income of those families without migrant family, see their income stagnate relative to families that receive remittances from abroad. This increases peoples’ aspirations and incentivizes families to send relatives abroad to earn an income there (Massey, 1993). Thus, “relative income” is more important in the decision to migrate (Stark & Taylor, 1989, 1991). Once, economic development continues to increase, the benefits of this will reach a larger part of the populations, whose incentives to migrate is then taken away.

Finally, Clemens argues that as income rises, residents looking to migrate are more likely to be eligible to receive a visa. Because many developed countries use a point system to evaluate visa applications, prospective migrants with a higher income will “earn” more points. These explanations do not function in isolation, but instead are closely intertwined, as literature on migration and development has shown. Nevertheless, the exact drivers of migration and the shape of the relationship between development and migration are still unclear.

Development aid and migration

In contrast to many earlier studies, this thesis focuses on development aid as the independent variable rather than GDP per capita. Previous research on the effect of development aid on migration flows has not been decisive. For example, Berthélemy, Beuran & Maurel (2009) find a positive relation between development aid and migration stock. They point to increased information about ‘labor markets’ in the donor countries, which leads more people to migrate. They coin this as the network effect of bilateral aid. Furthermore, in theory development aid raises the income in the developing country, which takes away credit constraints that functioned as a barrier to migration.

3 Remittances can be as high as 15% of total GDP of a country (The Gambia).

12 This study follows the mobility transition model, as it identifies a threshold after which more

development aid leads to less migration (approx. 7,300 USD in PPP). Lanati & Thiele (2018) point out that most countries receiving development assistance have an income per capita below the

threshold. This would mean that development assistance as a tool to curb migration is not effective, because according to the Mobility Transition Model, rising income in a country below the threshold would lead to higher levels of migration.

Belloc (2014) complements the previous study as he identifies how aspirations play an important role in the decision to migrate. As an explanation for the positive relation he finds, Belloc uses De Haas’ (2010) notion of migration aspirations. Development aid improves public services, education and most importantly information about possible destinations. Knowledge of economic development in Europe, leads young people to aspire to have the same amount of economic prosperity. This is line with earlier World Systems Theory but also with the Mobility Transition Model, which says that more information of possible destinations raises aspiration of prespective migrants. Since these migrants-to-be are not able to fulfill their aspirations at home, or the benefits of development aid does not reach them, they choose to migrate towards Europe.

Lanati & Thiele (2018), even though their study is modelled after Berthélemy, Beuran & Maurel, find a negative relation between development aid and migration flows. Rather than migrant stocks as the dependent variable, they use migrant flows to measure the effect of development aid. They find that this difference explains the different statistical relation they find. An interesting aspect of their study is that they include migrant stocks as a control variable to control information flows/network effects. They conclude that this cancels out much of the network/information effect of development that is found by Berthélemy, Beuran & Maurel. The explanation for this is that more recently development has been geared towards fulfilling the Sustainable Development Goals and Millennium Goals. Under this framework, development aid is directed at improving public services rather than income. Therefore, the idea that aid takes away credit constraints is no longer valid. Thus, the income raising aspect (which under the Mobility transition model would lead to more migration) is countered by the improvement of public services and governance. This conclusion is consistent with research by Clemens, Radelet, Bhavnani & Bazzi (2012) who find that aid only leads to a very small increase in GDP. Furthermore, Gamso & Yuldashev (2018) find that, even though in general, development aid leads to an increase in migration, development aid aimed at governance building and public infrastructure, decreases migration.

13 Summarized this literature overview shows the following. Firstly, scholars assumed migration was the result only of a (expected) difference of income between country of origin and country of

destination. Policy makers therefore allocated development aid in order to increase GDP, since this would naturally lead to lower differences in income. These conclusions are in line with the

neoclassical theory. Subsequently, empirical evidence pointed towards a so-called inverted-u relationship between economic development and migration. An increase of GDP would lead to an increase of migration because financial constraints that formerly limited people in their movements were lifted as a result of economic development. This correlation holds until the threshold of approx. 7,000/8,000 USD was reached. Only after a country reaches this threshold, would migration decrease. Focusing development aid solely on improving the economic conditions would therefore be counterproductive, since those countries that receive development aid have a GDP per capita below the mentioned threshold.

In this light policy makers shifted their development aid to include strengthening resilience, improving public services and infrastructure and investing in migration management. In this way, they better address the root causes of migration. Berthélemy, Beuran & Maurel (2009) conclusion is not surprising seeing that they use different measures of migration and conducted their study in a different period.

14

3. Hypothesis

The research will be aimed at 50 Sub-Saharan Africa countries concerning the period 2008 up and until 2018. Figures regarding aid provided are available up to and including 2017. Figures on asylum applications and other variables are available up to and including 2018. At a general level, I will look into the effect of the Total Aid provided to these countries. Total Aid is defined as the total sum of development aid received by these countries provided by all countries throughout the world. At a more detailed level, I will look into the effects of the Bilateral Aid provided to these countries by the 28 countries of the European Union. As more detailed information and numbers are present per individual country, I will try to relate push, pull and pair factors in order to analyze effects on immigration and explaining variables.

As shown in the literature review, previous studies have not reached consensus on the effect of development aid on migration levels. It is therefore difficult to hypothesize the sign of the relation between development aid and migration. Previously, I would hypothesize that development aid leads to higher levels of migration because of the income raising effect. This would be in line with the work by Berthélemy, Beuran & Maurel (2009) and Belloc (2014). However, as the most recent work finds that ODA leads to lower levels of migration. I have shown that development aid has recently been geared towards institution building rather than improving economic well-being at countries of origin, this thesis argues that the income-raising effect of aid is only limited. This is also supported by Clemens, Radelet, Bhavnani & Bazzi (2012) who found that development aid only has a limited positive effect on income. Therefore, credit constraints are not lifted and even if they are, the increased public infrastructure and governance through development aid leads to a lower desire for migration.

This thesis uses two methods to measure the effect of ODA on Asylum Applications. Firstly, it looks at bilateral flows of ODA between countries from the European Union and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Subsequently, a second independent variable is added to measure the effect of ODA received by an African country by all donors, also non-EU. Therefore, the main hypothesis of this thesis is that: Hypothesis 1: Official Development Assistance from the EU towards Sub-Saharan Africa is

negatively correlated to the amount of Asylum Applicants the European Union receives from Sub-Saharan Africa

This logic also applies to the second independent variable. This variable better captures the impact of the EUTF since the development aid allocated through this program falls under all Donors. It is not registered within the ODA a single EU country sends to Africa.

15 Hypothesis 2: Total Official Development Assistance is negatively correlated has a negative impact on the level of migration flows from Sub-Saharan Africa to the European Union.

Next to looking at the general impact of the ODA on the level of Asylum Applications, this thesis also researches the effect of the EUTF on the number of Asylum Applicants. Since the EUTF was

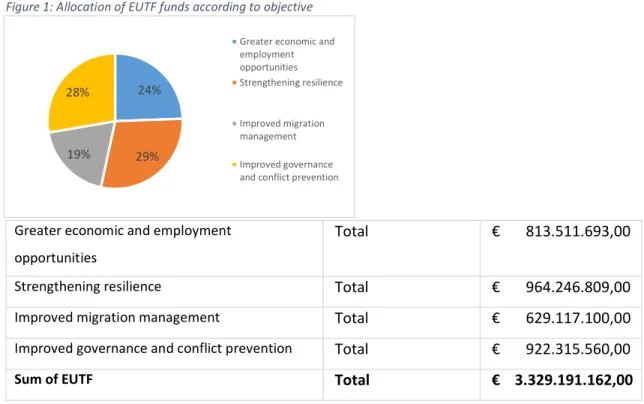

implemented in 2015, I expect to see a distinct difference in the amount of development aid allocated to Sub-Saharan Africa from 2015 onwards. Moreover, since 75% of all aid within the EUTF was aimed at goals other than improving economic conditions, I expect the income raising effect of the EUTF to be relatively small (see figure 1). In total 3.3 billion dollar has been allocated to the EUTF until 2019, which are divided according to the four objectives.

Hypothesis 3: The correlation between Total ODA and the level of Asylum Applications is stronger after the implementation of the EUTF in 2015, all other things equal

Thus, I expect to find a difference in the level of the correlation of Total ODA and Asylum Rate before and after 2015.

Figure 1: Allocation of EUTF funds according to objective

Greater economic and employment opportunities

Total € 813.511.693,00

Strengthening resilience Total € 964.246.809,00 Improved migration management Total € 629.117.100,00 Improved governance and conflict prevention Total € 922.315.560,00

Sum of EUTF Total € 3.329.191.162,00

24%

29% 19%

28%

Greater economic and employment opportunities Strengthening resilience Improved migration management Improved governance and conflict prevention

16

4. Sample and Descriptive Statistics

Sample

The dataset contains information on 28 donor countries of official development aid towards 50 Sub-Saharan African countries. In total, this leads to 1,400 unique country pair flows of migrants and bilateral aid. The data points are collected for the period 2008-2018, since 2018 is the most recent year the European Union has released data. Thus, the total amount of observations is 15,400.

Table 2: Share of zeros in the dependent variable

The dependent variable Asylum Rate consist for more than 60% of zeros. This means that for 60% of the observations, zero asylum applicants were registered. For instance, this is the case for the level of asylum applicants from Cape Verde to Germany in 2008.

Bilateral migration flows are available on Eurostat and are measured as the level of official Asylum Applicants in one of the 28 EU countries from one of the 50 Sub-Saharan countries. The Asylum Applicants include all persons who have submitted an asylum application. Even if this measure excludes people who entered the country illegally, this is a good approximation of the level of migration, which countries have to deal with in their official migration management systems. It is also the amount of asylum seekers –not official immigrants - that EU policies such as the EUTF target. Furthermore, Eurostat publishes information on statistics on bilateral immigration; however, this does not include people whose asylum applications was rejected. Finally, the OECD has data on migrant stocks from country of origin in country of destination. Using this information, it is possible to distill the change in migrant stock. However, when using this variable, the variable will also take on negative values whenever migrant stocks from an African country in a European country decrease. Moreover, it is not a relevant variable for the current research since it does not accurately capture the amount of asylum applications a country receives. It is also possible that citizens from e.g. Nigeria

4 Used by Lanati & Thiele (2018): They use Bilateral Flows of Emigrants using the OECD International Migration

Database. I use Eurostat, as this has more accurate information on migration flows towards the EU

5 Change in Migrant Stock is calculated as the difference in Migrant Stock from origin country in destination

country between t and t+1

6 Used by Berthelemy, Beuran & Maurel (2009); Beine & Parsons (2015) use change in migrant stock as their

dependent variable.

7 Change in Migrant Stock is calculated as the difference in Migrant Stock from origin country r in destination

country between t and t+1

Independent Variable Asylum Applicants Immigration4 Change in Migrant

Stock567

Observations 15,400 15,400 6,001

Number of zeros 9,804 10,408 1,283

17 that were previously living in France, moved to the UK. This movement, however, does not require any asylum application because they were already registered citizens of the European Union. Therefore, the variable that best captures what the European policy makers attempt to achieve through the EUTF (i.e. better manage illegal migration flows from Africa) is the level of Asylum Applicants. It is exactly the amount of people arriving and applying for asylum that puts pressure on the European asylum and refugee system. Through regressing other variables on Asylum Applications this thesis is able to identify what makes a country more or less attractive to prospective migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa. Asylum applications are weighed by the total population of the country of origin to calculate the dependent variable Asylum Rate.

For my independent variables I use the DAC database of the OECD. 8 The OECD has published data on ODA up to 2018. However, I will only use the data up to 20179, because the last years have not been fully updated. Using data until 2018 would thus show an inaccurate decrease in ODA in 2018

compared to previous years. The dataset of the OECD is used for the dependent variables Bilateral Aid and Total Aid. Both are taken as per capita net disbursements to weigh the flows of development aid destined for each country accurately. Control variables are obtained from sources such as the “World Bank: World Development Indicators” and the UCDP Conflict dataset. In contrast to for example Belloc (2014), I divide Development Aid by the population of the recipient country, rather than the GDP of the recipient country. Weighing development aid by population better reflects how much development aid is approximately destined for each person. However, this thesis does look at whether countries with higher GDP (per capita) receive more aid in general through a separate regression on the determinants Bilateral Aid.

A full list of variables with methods of calculation and the sources is available in the appendix 2.

Descriptive statistics

We can see that from 2008 until 2018, absolute numbers of asylum applications have risen

significantly from ‘only’ 68,505 applications in 2008 to 220,370 at its peak in 2016. Even though these numbers are quite high, compared to the total amount of applications the share of Sub-Saharan African asylum seekers is relatively low. For comparison, in 2015, the European Union received 1.3 million asylum applications. Whereas in 2008, asylum seekers from Africa made up almost a third of total applications, this share dropped to 13.4 % in 2015. Nevertheless, this share rose again after the

8 As ODA consists of loans and gifts the outcome can also be negative in a certain year in case a receiving

country pays back more of the loan provided in earlier years than aid received.

9 Since all independent variables and control variables are lagged by one year (if relevant) the fact that Aid is

only measured until 2017 does not have an impact on the regression, since I make the assumption that changes in thecontrol variables will only impact the Asylum Applications in the following year.

18 peak of the refugee crisis, showing how the inflow of migrants from Africa is still very relevant today. Other applicants mainly come from countries in conflict-areas such as Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Table 3: Amount of asylum applications received by countries European Union

Sub-Saharan Africa countries received on average 880 mln USD in 2008 to 1,200 mln USD in 2017 per year. Of which the bilateral aid out of the European Union amounted to approx. 250 mln USD per year. Except for 2008 and 2017, the share of bilateral aid out of the European Union remained consistent over the years. Per Sub-Saharan country on average 1,370 asylum applications were filed in the European Union in 2008. In 2016, this average reached its peak with on average 4,407 applications. Year Asylum Applications: Sub-Saharan Africa Asylum Applications: Total Share 2008 68.505 225.150 30,43% 2009 75.550 263.920 28,63% 2010 61.685 259.630 23,76% 2011 84.505 309.040 27,34% 2012 72.980 335.290 21,77% 2013 97.100 431.095 22,52% 2014 152.730 626.960 24,36% 2015 177.845 1.322.845 13,44% 2016 220.370 1.260.910 17,48% 2017 203.405 712.235 28,56% 2018 143.745 647.165 22,21%

19

Graph 1: Average values asylum applications Sub-Saharan Africa countries and aid received

Countries of the European Union received on average 2.447 asylum applications out of the Sub-Saharan Africa countries in 2008. Rising to 7.870 on average in 2016. The amount of aid provided fluctuates around 480 mln USD throughout the years. A decrease can be seen until 2014, after which the bilateral aid increases again.

Graph 2: Average asylum applications received and aid provided by European Countries

A preliminary view on the Bilateral Aid received and Total Aid received by Sub-Saharan Africa countries shows that aid has not risen in the same fashion as the Asylum Rate. This can also be seen in graph 1 where a rise in Total Aid results in only minor increase in Asylum Rate. Whereas the average asylum applicant per African country increased from 1,370 in 2008 to 4,407 in 2016 (a yearly

1370 1511 1234 1690 1460 1942 3055 3557 4407 4068 2875 300 270 260 280 270 260 220 220 270 260 880 980 950 990 970 1000 910 990 1000 1200 0 500 1000 1500 2000 2500 3000 3500 4000 4500 5000 0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 1400 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 N u mb er o f As yl u m AP p lic an ts Ai d in M ill io n s USD Year

Average Asylum Applicants Average Total Bilateral Aid Average Total Aid

2.447 2.698 2.203 3.018 2.606 3.468 5.455 6.352 7.870 7.264 5133,75 540 480 470 510 480 460 390 400 480 470 0 1.000 2.000 3.000 4.000 5.000 6.000 7.000 8.000 9.000 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 N u mb er o f As yl u m Ap p lic at io n s Ai d in M ill io n s USD Year

20 growth rate of 15,73%), in the same period bilateral aid decreased and total aid flows only increased by 1,61% on a yearly basis. However, only a slight increase in Total Aid was recorded after the height of the refugee crisis in 2016. This could indicate an inverse causal relation between Aid and Asylum

Rates, where countries receive more aid because asylum rates increased. However, this is only reflected in the amount of Total Aid received by countries of origin and not in Bilateral Aid received by African countries form European countries. The correlation between Bilateral Aid and the Asylum Rate appears to be even lower in this preliminary scatter plot [see appendix]

On average African countries had 4,007 asylum applicants to the European Union in 2016. However, there are some major outliers such as Nigeria, Eritrea, and Somalia with 47,765, 34,465 and 20,060 applicants respectively. Yet there were 28 Sub-Saharan Africa countries that recorded less than 1,000 asylum applicants. Countries of destination in the EU received 7,870 asylum applicants on average. In addition, here, there are major outliers such as Italy, Germany and France, which recorded 8538, 70,455 and 29,015 asylum applications respectively. Eastern European and the Baltic states received relatively few migrants.

R² = 0,0777 -2,5 -2 -1,5 -1 -0,5 0 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Lo g As yl u m Rat e

Log Total Aid

21

Table 4: Ranking asylum application receiving European Countries and Sub-Saharan Africa countries of origin

Rank Country of Destination

Year Asylum Applications

Rank Country of origin Year Asylum Applications 1 Italy 2017 88665 1 Nigeria 2016 47765 2 Italy 2016 85385 2 Nigeria 2017 41095 3 Germany 2016 70455 3 Eritrea 2014 36950 4 Italy 2015 50750 4 Eritrea 2016 34465 5 Germany 2017 45400 5 Eritrea 2015 34130 6 France 2018 44220 6 Nigeria 2015 31235 7 Italy 2014 41430 7 Nigeria 2018 25955 8 Germany 2018 36170 8 Eritrea 2017 25115 9 Germany 2015 36120 9 Somalia 2015 21030 10 Germany 2014 33930 10 Somalia 2016 20060

As shown in an earlier section, several studies have shown an inverted u-relationship between GDP per capita at country of origin and emigration rates. In contrast to other studies, this thesis only includes Sub-Saharan Africa countries as country of origin. Therefore, GDP per capita often does not surpass the threshold other studies identified of 7,000-8,000 USD. More surprising therefore is the slight negative relationship found between Asylum rate and the GDP per capita in the recipient country as seen in graph 2 and 3.

R² = 0,1623 -2,5 -2 -1,5 -1 -0,5 0 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Lo g As yl u m Rat e

Log GDP per capita recipient country

22

Graph 5: Relation GDP per capita and Asylum Rate (including zeros)

However, when eliminating the top half with the highest GDP per capita we see that there is a more pronounced negative relationship. The ‘poorest countries’ however record a slight positive

relationship between Asylum Rates and GDP per capita.10 This is consistent with the theory that above a certain threshold an increase of GDP leads to an decrease of emigration. In contrast, for countries below that threshold an increase in GDP per capita leads to an increase of emigration.

10Amongst the countries that surpass the threshold of 7,000-8,000 USD are island countries Mauritius,

Seychelles and oil-rich countries Equatorial Guinea and Gabon.

R² = 0,1315 0 0,1 0,2 0,3 0,4 0,5 0,6 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Lo g As yl u m Rat e

Log GDP per capita recipient country

-2,5 -2 -1,5 -1 -0,5 0 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Lo g As yl u m Rat e

Log GDP per capita recipient: high

23 -2,5 -2 -1,5 -1 -0,5 0 5 5,5 6 6,5 7 7,5 8 8,5 9 9,5 10 Lo g As yl u m Rat e

Log GDP per capita recipeint: low

24

5. Methodology

Econometric Specification

𝑨𝒔𝒚𝒍𝒖𝒎𝑹𝒂𝒕𝒆 = 𝛽1ln(𝐵𝑖𝑙𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑎𝑙𝐴𝑖𝑑𝑟𝑑,𝑡−1)+ 𝛽2+ ln(𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙𝐴𝑖𝑑𝑟𝑑,𝑡−1) + 𝛽3ln($𝐺𝐷𝑃𝑝𝑐𝑟,𝑡−1) + 𝛽4ln( $𝐺𝐷𝑃𝑝𝑐𝑑,𝑡−1) + 𝛽5ln(𝐶𝑜𝑙𝑜𝑛𝑦𝑑𝑟) + 𝛽6ln(𝑈𝑛𝑒𝑚𝑝𝑙𝑜𝑦𝑚𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑟,𝑡−1) + 𝛽7ln(𝑈𝑛𝑒𝑚𝑝𝑙𝑜𝑦𝑚𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑑,𝑡−1) + 𝛽8(𝑀𝑖𝑔𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛𝑃𝑜𝑙𝑖𝑐𝑦)𝑑,𝑡−1+ 𝛽9ln(𝑀𝑖𝑔𝑟𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑆𝑡𝑜𝑐𝑘𝑟𝑑,𝑡−1) + 𝛽10ln(𝑅𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝐺𝐷𝑃𝑝𝑐𝑟𝑑,𝑡−1) + 𝛽11(𝑃𝑜𝑙𝑆𝑡𝑎𝑏𝑖𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑦𝑟,𝑡−1) + 𝛽12( 𝐶𝑜𝑛𝑓𝑙𝑖𝑐𝑡𝑟,𝑡−1) + 𝛽13(𝑁𝑎𝑡𝑢𝑟𝑎𝑙𝐷𝑖𝑠𝑎𝑠𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑟,𝑡−1) + 𝛽14𝑙𝑛(𝑁𝑎𝑡𝑢𝑟𝑎𝑙𝐷𝑖𝑠𝑡𝑎𝑛𝑐𝑒𝑟𝑑) + 𝛽15(𝐿𝑎𝑛𝑔𝑢𝑎𝑔𝑒𝑃𝑟𝑜𝑥𝑖𝑚𝑖𝑡𝑦𝑟𝑑) + 𝛼𝑟+ 𝛼𝑑𝑡+ 𝜖𝑟𝑑,𝑡The econometric model used to describe the relation between aid and bilateral migration flows is based on the Gravity Model of International Migration as described by Beine, Bertoli & Fernandez-Huertas Moraga (2016) and Bertoli & Fernandez-Fernandez-Huertas Moraga (2012). This equation builds upon the Random Utility Maximization (RUM) model where prospective migrants assess the added utility of all possible destinations. The choice to emigrate is a so-called discrete choice. A person in country X can choose to emigrate or to stay at home. Moreover, that person has the choice between a diverse set of countries. In this thesis, this set of countries contains all European Union countries. The RUM model describes the expected utility or benefit for a migrant to choose country A over Country B. Furthermore, it allows controlling for changes in the utility of other countries.

This thesis adds Bilateral Aid flows between Sub-Saharan Africa countries (recipient, r) and European countries (donor, d), as well as the Total Aid, to the gravity model developed by Beine, Bertoli & Fernandez-Huertas Moraga (2016). This is done to see whether development aid is an effective tool for reducing migration. Migration is measured as the amount of Asylum applications from nationals of country (r) in country (d) at time t divided by the population from country(r). Other studies have used migrant stock to measure emigration rates. However, this measure also includes people who have been living in the country of destination for many years. Another option would have been to calculate the change using migrant stocks from year to year as Beine & Parsons (2015) have done I will use this measure in my robustness checks, since this also includes return migration. It could be interesting to see if ODA has a positive effect on the levels of migrants willing to return to their country

Utility for a prospective migrant is defined by various variables like the ones in the table below. Beine, Bertoli & Fernandez-Huertas Moraga (2016) in their guide to the gravity model introduce several explanatory variables for the different levels of emigration rate. Firstly, income at origin and income at destination are introduced. These overlap with the neoclassical theory of migration, which

25 identifies wage gaps as the driving factor behind migration. This thesis captures this variable through the inclusion of the natural log of the GDP per capita at origin and destination, lagged by one year as the effect of aid in year t could not expected to affect immigration in the same year but at the earliest in year t+1. Furthermore, as a control variable the equation includes the ratio of GDP per capita at destination divided by GDP per capita at origin.11 These variables also control for the credit constraints that are identified by the migration hump theory as determinants of migration (Vogler & Rotte, 2000; Clark, Hatton & Williamson 2007). As Harris and Todaro (1970) showed, migrants take into accounted the expected wage at destination and origin when assessing the utility of emigrating. This is captured through adding unemployment rate in donor country (d) and recipient country (r). Non-monetary barriers also play a role in the attractiveness of migration destinations. This is captured through the inclusion of the Migration Score, developed by the Center for Global Development. A higher score on this index implies a more open immigration policy, implying a positive relationship between this variable and the dependent variable.

Massey (1988) showed how the presence of diaspora’s in countries of destination increases the information people in countries of origin have about that destination country. They show how early migrants influence the presence of information about economic prospects at destination. It is hypothesized that this has a positive effect on the levels of migration towards that destination country (Lanati & Thiele, 2018). Through including ln(𝑀𝑖𝑔𝑟𝑎𝑛𝑡𝑆𝑡𝑜𝑐𝑘𝑟𝑑,𝑡−1) this equation controls for network effects. Furthermore, political stability and the presence of conflict in countries of origin function as push factors for migration. In addition, the occurrence of natural disasters play a role in

11 PPP, constant 2011 USD dollars.

26 the decision to migrate. These factors are included through 𝑃𝑜𝑙𝑆𝑡𝑎𝑏𝑖𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑦𝑟,𝑡−112 𝐶𝑜𝑛𝑓𝑙𝑖𝑐𝑡𝑟,𝑡−1 𝑁𝑎𝑡𝑢𝑟𝑎𝑙𝐷𝑖𝑠𝑎𝑠𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑟,𝑡−1 respectively. Finally, distance and language proximity are added as indicators of (cultural) proximity between origin and destination countries.

Overall, there are four kinds of variables. Firstly, the bilateral variables such a BilateralAid, Asylum Rate. Secondly, variables that change in time at origin, for example $𝐺𝐷𝑃𝑝𝑐𝑟,𝑡−1

and 𝑃𝑜𝑙𝑆𝑡𝑎𝑏𝑖𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑦𝑟,𝑡−1. Finally, there are variables that change in time at destination such as 𝑈𝑛𝑒𝑚𝑝𝑙𝑜𝑦𝑚𝑒𝑛𝑡𝑑,𝑡−1 and𝑀𝑖𝑔𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛𝑃𝑜𝑙𝑖𝑐𝑦. Next to these variables that change over time, there are time-invariant factors such as Common Language and Distance between origin and destination. In line with Bertoli & Fernandez-Huertas-Moraga (2016), this thesis makes use of a PPML (Poisson Pseudo Maximum Likelihood) regression, since this method allows accounting for several factors, which other methods do not account for. Firstly, a PPML regression deals with the problem of many zeros in the dataset (see table 1). This is the case for my dependent variable Asylum Rate, which has zeros that for more than 60 % of the dataset. This is common when using bilateral migration flows considering that not all countries receive migrants from every African country. This is especially so in this thesis where the dependent variable is the total number of Asylum Applicants. Also for

robustness tests where I use Immigration numbers as dependent variable, will PPML be the correct estimation method. Only when using change of Migrant Stock does a regular linear model or a two-stage selection model suffice.

Table 5: List of variables with their expected sign

12 Political Stability is measured on a scale from -25 to 2,5 where a higher score indicates a higher level of

political stability, source World Bank Development Indicators.

Independent Variable Variable Expected Sign

Development aid Ln(BilateralAid from donor to recipient at t-1)

Negative

Ln(TotalAid received by recipient at t-1) Negative

Determinants of migration Variable Expected sign

Expected income Ln( GDP per capita donor at t-1) Positive

Credit constraints Ln (GDP per capita recipient at t-1) Positive Ln (GDPpc donor, t-1/ GDPpc recipient,

t-1)

Positive

Expectations about Income Ln (Unemployment rate donor at t-1) Negative Ln(Unemployment rate recipient at t-1) Positive

Immigration policies Migration Policy donor at t-1 Positive

Environment Natural Disasters at t-1 in recipient

country

27 Secondly, through using the PPML model it is possible to account for multilateral resistance to

migration (MRM). Bertoli & Fernandez-Huertas Moraga (2012) show the significance of accounting for this. They describe how change in the attractiveness of one country (x) also has an effect on the levels of migration from an African country (y) to a third country(z). For example, if Belgium

unilaterally raises visa requirements for Congolese citizens, this automatically makes neighboring countries such as France more attractive for Congolese migrants (assumed all other factors equal) (Beine, Bertoli & Fernandez-Huertas Moraga, 2016). This model is able to account for the utility of all possible destination countries for a prospective migrant, rather than only the utility of one country (Beine & Parsons, 2015). MRM can be captured through including origin and destination-time fixed effects. This is done through adding 𝛼𝑟+ 𝛼𝑑𝑡 to the equation above13. Finally, PPML is able to perform well even if the dependent variable is not Poisson distributed (Santos Silva & Tenreyro, 2011).

However, previous literature indicates that bilateral migration might also influence the allocation of aid (Berthélemy, Beuran & Maurel, 2009; Belloc, 2014; Lanati & Thiele, 2018). Therefore, to account for endogeneity and reverse causality this thesis follows Berthélemy, Beuran & Maurel (2009) by adding a second regression to determine how bilateral aid is allocated. It is possible that countries send more aid to countries that have higher levels of migrants from that country living within their borders. The political influence these groups might exert on politics could lead to a bias in where countries send their ODA (Lanati & Thiele, 2018). The equation below captures those variables that

13When using PPML to estimate a gravity model it is necessary to include origin time dummies (Beine, Bertoli and Fernandez-Huertas Moraga 2016)

Information networks Migrant Stock of recipient country in donor country at t-1

Positive

Proximity Language proximity donor and

recipient country recipient country

Positive

Natural Distance Negative

Former Colony Positive

Presence of Conflict Conflict in recipient country at t-1 Positive Political Stability in recipient country at

t-1

Positive

Distance NaturalDistance Negative

Lack of public services Corruption Positive

European Emergency Trust Fund for Africa

EUTF Negative