'Associations between cognitive

functioning, neuropsychiatric

symptoms and quality of life, and

physical activity and fitness in

Portuguese patients with dementia'

Word count: 8,678Ellen Geens and Aïsha Vandenbroucke

Student numbers: 01804882 and 01811528Promotor: Prof. dr. Maïté Verloigne

Copromotor: Prof. Andreia Pizarro

Extra supervisor: Prof. Arnaldina Sampaio

A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Health Promotion

'Associations between cognitive

functioning, neuropsychiatric

symptoms and quality of life, and

physical activity and fitness in

Portuguese patients with dementia'

Word count: 8,678Ellen Geens and Aïsha Vandenbroucke

Student numbers: 01804882 and 01811528Promotor: Prof. dr. Maïté Verloigne

Copromotor: Prof. Andreia Pizarro

Extra supervisor: Prof. Arnaldina Sampaio

A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Health Promotion

Preamble

The goal of our Erasmus stay in Portugal from the beginning of February to the beginning of May 2020 was to write our thesis at the University of Porto. Professors Andreia Pizarro and Arnaldina Sampaio helped us with this research project on the benefit of physical activity for elderly people with dementia. We agreed on some deadlines for the written parts of our thesis and they made a schedule for us to complete the required fifty hours of fieldwork by observing physical activity classes, creating our own exercise program, inserting data in SPSS, and so on. After one month, we were making progress with the research and with the fieldwork hours. We thought we would definitely make the deadline of the master thesis and, as planned, we would defend our master thesis in Belgium.

As a result of the corona pandemic and the accompanying measures, we had to return from Portugal earlier (mid-March 2020). Due to these circumstances, it was impossible to carry out the research and fieldwork as we originally planned. Normally we would have more participants for the master thesis research, but because of the virus the research slowed down. A lot of the elderly people did not find it safe enough to come to the data collection moments and to the exercise classes so the research got postponed. Therefore, the number of participants in our thesis is lower than we anticipated. The writing of our thesis went more slowly because the researchers were working hard to find a solution for their project and did not find much time to support us in writing or giving feedback. Because of the impact of the virus, Ghent University agreed to give us an exemption of 20 hours of fieldwork for the first exam period. Ellen already had enough hours, but Aïsha helped for another eight hours with a literature study of a paper that some researchers at Ghent University planned on writing. Following our return to Belgium, we had regular online meetings with our promoter from Ghent University (Maïté Verloigne) to discuss how we could proceed with our thesis. In addition, we had weekly online meetings with Andreia Pizarro and Arnaldina Sampaio to communicate our progress on the master thesis, ask for feedback and for some missing information.

This preamble was approved by both parties in consultation with both students and the promoter.

Table of contents

Acknowledgements ... 6

Introduction ... 7

Scientific article ... 9

Abstract – English version... 9

Abstract – Dutch version ... 10

1. Literature review ... 11

1.1 Scientific background of the research project ... 11

1.2 Description of the research problem ... 16

1.3 Description of the research questions and hypotheses ... 16

2. Research methodology ... 17 2.1 Study procedure ... 17 2.2 Measuring instruments ... 18 2.3 Statistical analyses ... 21 2.4 Ethical aspects ... 22 3. Results ... 23 4. Discussion ... 28 5. Conclusion ... 32 Bibliography ... 34 Appendices ... 1 Appendix 1: Questionnaires ... 1

Appendix 2: Informed consent ... 1

Appendix 3: Consent forms ethical committee ... 1

Appendix 4: Fieldwork log ... 1

Acknowledgements

The last step in finishing our ‘Master of Science in Health Promotion’ at Ghent University has been to work together as a team in Porto and later in Belgium to bring this thesis to a successful end. The research project has been an interesting journey.

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the persons who helped us this last year. First of all, we would like to thank our supervisor from Ghent University, Maïté Verloigne, for helping us wherever she could. She stood by our side and guided us with her expertise and feedback throughout the research. We would like to thank Prof. Joana Carvalho, leading researcher of the bigger study ‘Body and Brain’, for letting us join this research project, through straight articulation with Andreia Pizarro and Arnaldina Sampaio from the University of Porto. We are thankful for their help, support, expertise, and feedback. Our gratitude also goes to our family, our fellow students, and our friends for being there for us and for their encouragement. We hope this thesis will be as interesting for you as a reader, as it was for us to conduct the research.

Introduction

Dementia is a worldwide problem and a major cause of disability and dependency among elderly people (WHO, 2019). Therefore, conducting research about the role of physical activity (PA) and physical fitness as preventable factors of dementia or as factors that can reduce the progression of dementia is a relevant topic in this research domain. In the literature, there is also the need to carry out more studies that focus on the effect of PA on neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with dementia (Fleiner et al., 2017; Sobol et al., 2018) because so far, studies show opposite results. The focus on quality of life (QoL) in people with dementia is an important research field as well (Logsdon et al., 2002). It would be interesting to further examine the effect of physical fitness on QoL in persons with dementia as physical fitness is linked with functionality and independency which could influence the QoL (Ruthirakuhan et al., 2012). Hence, this master thesis focuses on investigating PA and physical fitness as mediators in the association between cognitive functioning and neuropsychiatric symptoms, and between cognitive functioning and QoL respectively in Portuguese people with dementia.

This cross-sectional study is part of our Erasmus exchange program at the University of Porto. Together with our copromotor and extra supervisor there, it was possible to be a part of this research and to carry out this study. This topic belongs to the larger interventional study ‘Body and Brain’ in which the participants are Portuguese, elderly people with dementia who are undergoing a 10-month physical exercise intervention. Three measurings are being conducted but for this cross-sectional study only the baseline data were used. Participants were recruited by advertisements in hospitals, community centers, and nursing homes, considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria mentioned later in this paper. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the bigger research is suspended until safety of the participants is assured. Therefore, data on the variables of interest were collected for only 26 participants. ‘Body and Brain’ was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Sports of the University of Porto and by the Foundation for Science and Technology in Portugal. Our master thesis research was approved by the medical ethics committee of Ghent University in Belgium.

For our analyses, only patients with mild and moderate dementia were included so our sample consisted of only 19 participants. Different measuring instruments were used to collect different variables. An anamnesis questionnaire was used to collect demographic and medical variables, a SECA 213 Stadiometer was used to measure height, a Tanita weighing scale to measure weight, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) to measure cognitive functioning, a GT3X Actigraph accelerometer to measure PA variables, the 2-minute Step Test and the grip strength dynamometer to measure physical fitness variables, the NPI-Q for the assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms, and the QoL-AD for assessment of QoL in patients

with dementia. Both the MacKinnon test and the Sobel test were used to examine the mediating effects.

First of all, a thorough literature review was carried out to explore the theme of our research in order to create a picture about the problem, research questions, and hypotheses. In the second part, the research methodology containing the study procedure, measuring instruments, statistical analyses, and ethical aspects was described. After that, the results were presented and finally the discussion and conclusion were written down.

We contributed to this research by doing some fieldwork hours. The main part consisted of observing the different PA classes for the elderly people and writing down our observations in a report. We also had the possibility to help with the data collection. Furthermore, we inserted some data in SPSS in order to carry out the analyses later. All decisions about the master thesis were made together and all analyses were performed by both students. The acknowledgements, introduction, abstracts, literature review, research methodology, results, discussion, conclusion and bibliography were written down by both students to complement each other. In the end everything was reread by both students.

Scientific article

Abstract – English version

Background: The number of people with dementia is rising worldwide. Dementia is

characterised by cognitive decline which can in turn be associated with health and behavioural consequences. Therefore, the first aim was to investigate the association between cognitive functioning, and neuropsychiatric symptoms and QoL. Secondly, the mediating effects of (a) PA indicators on the association between cognitive functioning and neuropsychiatric symptoms and (b) physical fitness indicators on the association between cognitive function and QoL were investigated.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was performed with 19 Portuguese participants with dementia (mean age 75.21 (± 7.77) years; 78.9% female). Objective and subjective measuring instruments were used to assess the different variables. Mediating analyses using the Mackinnon test were conducted in SPSS 26.

Results: There was no significant association between cognitive function and neuropsychiatric

symptoms, and sedentary time and moderate to vigorous PA (MVPA) did not significantly mediate this association. There was a significant positive association between cognitive functioning and QoL reported by the caregiver (Beta=-5.02, SE=1.27, 95% BI=-7.50;-2.54) and QoL total score (Beta=-3.68, SE=1.57, 95% BI=-6.76;-0.60), but not for QoL reported by the patient. Aerobic endurance and handgrip strength did not significantly mediate these associations.

Conclusion: Very few significant associations were found, so future studies should explore if

similar research findings are found among a larger sample size.

Number of words article: 8678 (exclusive foreword, table of contents, introduction, abstract, appendices, tables and reference list)

Abstract – Dutch version

Achtergrond: Het aantal mensen met dementie neemt wereldwijd toe. Dementie wordt

gekenmerkt door cognitieve achteruitgang die op zijn beurt geassocieerd kan worden met gevolgen op vlak van gezondheid en gedrag. Hierdoor was het eerste doel de associatie te onderzoeken tussen cognitieve functie, en neuropsychiatrische symptomen en levenskwaliteit.

Ten tweede werden de mediërende effecten van (a) fysieke activiteitsindicatoren op de associatie tussen cognitieve functie en neuropsychiatrische symptomen en (b) fysieke fitnessindicatoren op de associatie tussen cognitieve functie en levenskwaliteit onderzocht.

Methoden: Een cross-sectionele studie met 19 Portugese deelnemers met dementie

(gemiddelde leeftijd 75.21 (± 7.77) jaar; 78.9% vrouwen) werd uitgevoerd. Objectieve en subjectieve meetinstrumenten werden gebruikt om de verschillende variabelen te beoordelen. Mediatie-analyses met behulp van de MacKinnon-test werden uitgevoerd in SPSS 26.

Resultaten: Er was geen significante associatie tussen cognitieve functie en

neuropsychiatrische symptomen, en sedentaire tijd en matige tot krachtige fysieke activiteit waren geen significante mediatoren op deze associatie. Er was een significante positieve associatie tussen cognitieve functie en levenskwaliteit aangegeven door de mantelzorger (Beta=-5.02, SE=1.27, 95% BI=-7.50;-2.54) en totale levenskwaliteitscore (Beta=-3.68, SE=1.57, 95% BI=-6.76;-0.60), maar niet voor levenskwaliteit aangegeven door de patiënt. Aëroob uithoudingsvermogen en handgreepsterkte waren geen significante mediatoren op deze associaties.

Conclusie: Er werden weinig significante associaties gevonden. Toekomstige studies zouden

moeten nagaan of soortgelijke onderzoeksresultaten bij een grotere steekproefomvang gevonden worden.

Aantal woorden artikel: 8678 (exclusief woord vooraf, inhoudstafel, inleiding, abstract, bijlagen, tabellen en referentielijst)

1. Literature review

1.1 Scientific background of the research project

Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease

Due to worldwide ageing populations, the number of people with dementia is quickly climbing. As reported by the World Health Organization (WHO) (2019), around 50 million people worldwide have dementia and there are almost 10 million new cases every year. Every three seconds, there is a person that develops the disease (Alzheimer’s Disease International,

2019). According to Livingston and colleagues (2017) dementia is the greatest global challenge for health and social care in the 21st century. The WHO pronounced the disease to be a public health priority in 2012 (Wortmann, 2012). Dementia is a syndrome that has negative consequences on different domains like cognition, memory, behaviour, ability to perform everyday activities, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and comorbid physical illnesses. Age is the main risk factor, especially after the age of 65 (Livingston et al., 2017). There are various types of dementia that differ from each other and Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type with 60 to 70 percent of all cases (Van Praag, 2018).

Alzheimer’s disease is categorized under the neurodegenerative diseases which are characterized by nerve cells in the brain or peripheral nervous system who lose function over time and die (Gitler, Dhillon, & Shorter, 2017; National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, 2019). Alzheimer’s disease can affect the well-being of individuals who have the disease in very intensive ways (Karttunen et al., 2011), and is an important cause of dependency and disability in elderly people (WHO, 2019). Unfortunately, the impact does not only relate to the person who has the disease. Informal caregivers and families can also be affected because of the stress caused by dementia (Forbes, Forbes, Blake, Thiessen, & Forbes, 2015; Merrilees, 2016). Next to this psychological influence, it can be physically demanding to take care of a person with dementia. A social impact can also be present, for example time for social activities that is replaced by caregiving, leading to caregiver burden. Furthermore, it causes an increased cost to society because of possible medical care expenses (WHO, 2019).

The symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease vary from person to person and as the disease progresses, but one of the most common symptoms is progressive memory deterioration (Cass, 2017). Moreover, global cognitive functioning is also progressively affected by Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia. Therefore, a cognitive function tool, such as the widely used MMSE, is used as a surrogate measure to reflect dementia (Perneczky et al., 2006). The measure assesses in an easy way seven areas of cognitive functioning: orientation

in time, orientation in place, registration, attention and calculation, recall, language, and visual construction (Huisingh, Wadley, McGwin Jr, & Owsley, 2018). This tool ranges cognitive function from zero to 30, whereby lower scores indicate greater cognitive impairment (Logsdon,

Gibbons, McCurry, & Teri, 2002). The longitudinal study of Lo and colleagues (2019) stated that there is an association between dementia stage and MMSE, whereby a further stage reflects a lower MMSE. Logsdon and colleagues (2002) also concluded that MMSE can be used to classify patients by their level of dementia.

The association between dementia and neuropsychiatric symptoms

Neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia, also known as behavioral and psychological symptoms, are various. There are four common clusters of these symptoms: (1) the hyperactivity cluster that consists of agitation, aggression, euphoria, disinhibition, irritability, and aberrant motor activity, (2) the psychosis cluster that consists of hallucinations and delusion, (3) the affective cluster that contains depression and anxiety, and (4) the apathy cluster that includes appetite disturbance, sleep disturbance, and apathy (Aalten et al., 2007; Petrovic et al., 2007). According to a study of Yatawara, Hiu, Tan, and Kandiah (2018) the prevalence of these symptoms is high, namely 85% of the people with mild to moderate dementia have at least one of these symptoms. Several studies confirm that they are common in all stages of the disease, even the early ones (Christofoletti et al., 2011; Karttunen et al., 2011; Savva et al., 2009). Lo and colleagues (2019) concluded in their six-year research about the association between neuropsychiatric symptoms, MMSE, and the conversion to Alzheimer’s disease, that there is a negative correlation between neuropsychiatric symptoms and cognitive function (i.e. the lower the MMSE score, the more neuropsychiatric symptoms). Also the study of Srikanth, Nagaraja, and Ratnavalli (2005) showed that some of the neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as disinhibition and aberrant motor behaviour, are more common in a later stage of dementia.

The development of neuropsychiatric symptoms can be genetic, psychological, or neurobiological, but also social aspects can contribute (Alzheimer’s Association, 2015; Cerejeira, Lagarto, & Mukaetova-Ladinska, 2012). Neuropsychiatric symptoms usually are distressful on both people with dementia and their caregivers, thus, the treatment of these symptoms is an important challenge in dementia care (Fleiner, Dauth, Gersie, Zijlstra, & Haussermann, 2017). Pharmacological therapies have limited positive effects and substantial side effects so they must be reserved for more severe stages (Livingston et al., 2017). In opposition, the relevance of non-pharmacological therapies for neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia, such as exercise, is increasing (Marques-Aleixo et al., 2020).

The association between dementia and quality of life

Interventions for people with dementia or neurodegenerative diseases mainly focus on maintaining the ability to perform activities of daily life and QoL (Marques-Aleixo et al., 2020). QoL is described as a multidimensional and complex concept that focuses on several aspects such as physical, psychological, and social functioning (Karttunen et al., 2011). The field of QoL measurement is expanding at high speed, simultaneous with the incorporation of this form of measurement into many clinical trials (Eldredge et al., 2016). QoL appraisals contribute to a format for individuals, their caregivers, and researchers to examine if an intervention made a far-reaching impact on the patient’s life. In this way, researchers can figure out which treatments have clinically significant benefits for the patient (Logsdon et al., 2002). For instance, a deceleration of both cognitive decline and the development of dependence in activities of daily living is important for enlarging the QoL for people suffering from dementia (Forbes et al., 2015).

Kazazi, Foroughan, Nejati, and Shati (2018) conducted a research about the association between cognitive decline and health related QoL, which is only about the aspects of QoL that are affected by health, in older Iranian individuals. The study concluded that the better the cognitive function is, the better the health-related QoL. Also Missotten and colleagues (2008) stated that MMSE has a significant impact on QoL whereby people with dementia have a lower QoL than people with mild cognitive impairment.

The role of physical activity

A lot of research has already focused on the prevention of dementia (Livingston et al., 2017). According to the World Alzheimer Report of 2019 one out of four people think that there is nothing that can be done in order to prevent dementia and around 80 percent of the population is concerned about developing it (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2019). However, the Lancet Commission claims that more than a third of the dementia cases might be preventable. Some adjustments will not make a difference and some risks of dementia are not preventable because they are genetically determined. Nevertheless, effective dementia prevention, intervention, and care could alter the future for individuals suffering from dementia, their families, and society (Livingston et al., 2017). In our research, there is a focus on people who already received the diagnosis of dementia, mild cognitive impairment, or neurodegenerative disease.

A possible way to tackle dementia or postpone its effects is with non-pharmacological treatment, such as engaging in PA (Forbes et al, 2015). There is a growing interest in this theme which seems to be effective in both prevention and treatment of dementia (Cass, 2017; Fleiner et al., 2017; Ströhle et al., 2015; Thuné-Boyle, Iliffe, Cerga-Pashoja, Lowery, & Warner,

2012). PA is defined by the WHO (2020a) as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that requires energy expenditure.

A meta-analysis of Heyn, Abreu, and Ottenbacher (2004) and a study of Laurin, Verreault, Lindsay, MacPherson, and Rockwood (2001) showed that there is an inverse relation between PA and the risk of dementia. Being physically active is advantageous for people in general for a variety of reasons, including cardiovascular health, strength, protection against diabetes, obesity, and frailty. PA also has a significant protective effect on cognitive decline, whereby the higher the level of PA, the more it is protective. Older adults with dementia and cognitive impairment who are physically active have a higher chance to maintain cognition than the ones who are not physically active (Livingston et al., 2017). It improves physical functions and helps people with dementia to uphold activities of daily living (Blankevoort et al., 2010; Forbes et al., 2015; Littbrand, Stenvall, & Rosendahl, 2011). Although most studies demonstrated evidence for a link between PA and cognitive functioning, the study of Daimiel and colleagues (2020) showed that there is only a positive association between physical fitness, which will be described below, and cognitive function, but not between the level of PA and cognitive function. Besides having a possible effect on cognitive function, PA might also ameliorate neuropsychiatric symptoms (Christofoletti et al., 2011). PA seems to have a positive effect on plasticity, volume in brain regions, and other biological processes that are involved in the different neuropsychiatric symptoms (Hayes, Alosco, & Forman, 2014; Mah, Binns, Steffens, & Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, 2015; Matura, Carvalho, Alves, & Pantel, 2016; Trzepacz et al., 2013). The conditions that seem to be most positively affected by PA are apathy, depressive symptoms, sleep disturbances, agitation, emotional welfare, and functional capacity (Neil & Bowie, 2008; Woodhead, Zarit, Braungart, Rovine, & Femia, 2005). However, the evidence is inconsistent. According to a meta-analysis of Veronese, Solmi, Basso, Smith, and Soysal (2018) there is no link between PA and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Nevertheless, different studies demonstrated a favourable effect of PA on depression and sleep disturbance (de Souto Barreto, Demougeot, Pillard, Lapeyre-Mestre, & Rolland, 2015; McCurry et al., 2011; Nascimento et al., 2014; Regan, Katona, Walker, & Livingston, 2005; Teri et al., 2003; Williams & Tappen, 2008) while others said the opposite (Kurz, Pohl, Ramsenthaler, & Sorg, 2009; Yu et al., 2013).Next to that, there can be a positive effect of PA on sleep disorders in people with vascular dementia, but the overall reduction of neuropsychiatric symptoms because of PA is not present in patients with mixed dementia (Christofoletti et al., 2011). Contradictory evidence could be related to the heterogeneity of study designs and interventions (Forbes, et al., 2015).

The role of physical fitness

Exercise is a subcategory of PA and has the goal to improve or maintain physical fitness, which indicates a set of health or skill-related attributes, such as muscular strength or athletic ability (Caspersen, Powell, & Christenson, 1985). The type of exercise that seems to have the best effects on older adults with neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, is multicomponent training (Hernández et al., 2015). It mostly consists of aerobics, resistance training, balance, and postural exercises (Baker, Atlantis, & Fiatarone Singh, 2007). In addition, it seems to encourage adherence and satisfaction in elderly people (Carvalho, Marques, & Mota, 2008).

Physical fitness, also known as physical functioning and functional fitness, comprises muscle strength, flexibility, balance, agility, and aerobic endurance (Justine, Hamid, Mohan, & Jagannathan, 2011). A study of Ruthirakuhan and colleagues (2012) showed that physical exercise and therefore better physical functioning seems to be beneficial for patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Better physical functioning leads to improved performance of activities of daily living as well and to less cognitive decline and even to cognitive improvement in some cases. Some other studies confirmed that better physical fitness reduces the risk of dementia and has a number of other benefits like improving cognition and autonomous functional capacity (Pitkälä, Savikko, Poysti, Strandberg, & Laakkonen, 2013; Sampaio et al., 2020). Physical fitness is globally acknowledged as a crucial component of QoL and as an indicator of health status in older adults (Justine et al., 2011; Kawamoto, Yoshida, & Oka, 2004). Engaging in exercise is associated with statistically significant positive treatment effects in older patients with dementia and cognitive impairments. The meta-analysis of Heyn and colleagues (2004) suggested a medium to large treatment effect for health-related physical fitness components, and an overall medium treatment effect for combined physical, cognitive, functional, and behavioral outcomes. Again, no consensus was found between different studies. Some studies did find a significant positive effect of physical fitness on QoL in older individuals (Singh, Clements, & Fiatarone, 1997; Teri et al., 2003), in contrast to other studies who did not find a significant improvement on QoL in elderly people with Alzheimer’s disease (Steinberg, Leoutsakos, Podewils, & Lyketsos, 2009). Therefore, the systematic review of Potter, Ellard, Rees, and Thorogood (2011) concluded that strong evidence about the improvement on QoL is lacking.

1.2 Description of the research problem

A considerable amount of research that assesses dementia using the MMSE is available (Logsdon et al., 2002; Perneczky et al., 2006) but not a lot of studies are conducted about the association between cognitive function stage of elderly people with dementia and neuropsychiatric symptoms or about the association between cognitive function stage and QoL. So, further research about these associations is recommended.

Although an increasing body of literature has been addressing the relationship between dementia and PA (Forbes et al., 2015; Heyn et al., 2004; Rolland et al., 2007), more research is needed about different aspects in neuropsychiatric symptoms among elderly people with dementia and PA. There is a need for more specific studies about the effects of PA on neuropsychiatric symptoms separately (Fleiner et al., 2017; Sobol et al., 2018). Overall, more studies are needed addressing the efficacy of different PA interventions in the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms (Forbes et al., 2015).

Furthermore, the appraisal of QoL in patients with dementia is an essential and fruitful field for future research (Logsdon et al., 2002). The field of QoL is developing at high speed (Eldredge et al., 2016) but not a lot of studies are conducted about the associations between physical fitness and QoL. Thus, it would be interesting to examine the effect of physical fitness on QoL in persons with dementia as a better physical fitness can be a surrogate for autonomy in elderly people (Sampaio et al., 2020).

1.3 Description of the research questions and hypotheses

The goal of this research is to determine if there are associations between cognitive functioning and neuropsychiatric symptoms, and cognitive functioning and QoL and if PA and physical fitness respectively could mediate these associations in older adults with dementia in Portugal.

The specific research questions below focus on studying the associations between these variables in elderly people, from 65 to 94 years, with dementia. Two research questions were drafted in the context of this research:

1. a) Is there a negative association between cognitive function stage of elderly people with dementia and neuropsychiatric symptoms?

b) Is there a positive association between cognitive function stage of elderly people with dementia and QoL (reported by the patient and caregiver)?

2. a) Is there a mediating effect of PA variables (sedentary time and MVPA) on the association between cognitive function stage and neuropsychiatric symptoms in elderly people with dementia?

b) Is there a mediating effect of physical fitness (measured by 2-minute Step Test and handgrip strength test) on the association between cognitive function stage and QoL (reported by the patient and caregiver) in elderly people with dementia?

The following research hypotheses indicate the results that the study expects to generate when studying cognitive functioning, neuropsychiatric symptoms and QoL, and PA and physical fitness of elderly people from 65 to 94 years with dementia in Portugal, based on the literature review.

1. a) There is a negative association between cognitive function stage of elderly people with dementia and neuropsychiatric symptoms.

b) There is a positive association between cognitive function stage of elderly people with dementia and QoL (reported by the patient and caregiver).

2. a) There is a mediating effect of PA variables (sedentary time and MVPA) on the association between cognitive function stage and neuropsychiatric symptoms in elderly people with dementia.

b) There is a mediating effect of physical fitness (measured by 2-minute Step Test and handgrip strength test) on the association between cognitive function stage and QoL (reported by the patient and caregiver) in elderly people with dementia.

2. Research methodology

2.1 Study procedure

This research has a cross-sectional study design and is part of a larger interventional study, named ‘Body and Brain’ (National Library of Medicine, 2019). The target population are elderly people with a medical diagnosis of dementia who undergo a 10-month physical exercise intervention twice a week. Measurements of ‘Body and Brain’ take place at three points in time:

at baseline, at ten months and three months after the intervention. For this particular research only baseline data were used. The recruitment of ‘Body and Brain’ was done by advertisements

in two hospitals, two community centers, three nursing homes, five day care centers, and five centers who are as well day care centers as nursing homes.The recruitment for our research project was done by advertisements in only two hospitals, two community centers, and two nursing homes.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were lined up. The inclusion criteria consist of the following aspects: (1) age equal to or above 65 years, (2) clinically diagnosed with dementia by a

physician, and (3) having the ability to mobilize independently. The exclusion criteria were the following: (1) presence of dementia in an advanced stage, (2) engagement in regular exercise training or being involved in a cognitive stimulation program, (3) personal history of major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or another major neuropsychiatric disorder, and (4) the presence of health conditions, like cardiovascular pathologies, that lead to no participation in practice sessions. The baseline data of 26 participants were collected, however, for the analysis only 19 participants were included, namely the ones with mild and moderate dementia. The caregivers of the participants were also asked some questions via a questionnaire to complete the baseline data.

2.2 Measuring instruments

Demographic and medical variables

Demographic variables, such as age, gender, and number of education years, and medical information, like the amount of medication and the diagnosis of dementia, were obtained by an anamnesis questionnaire. There was no specific test for the reliability or validity of this questionnaire, but the ethical committee and personal data unit of the University of Porto agreed with the format and content.

Body Mass Index

The weight and height of the participants were measured by the Tanita weighing scale and the SECA 213 Stadiometer respectively, according to standardized procedures. The Body Mass Index (BMI), the ratio of the body weight to squared height (kg/m

²

) (Vagetti et al., 2015), was calculated and WHO cut points for underweight, normal weight, overweight and obesity were used to classify the ponderal status (WHOb, 2020). Test-retest showed a good level of reliability for the Tanita scale and the measuring instrument showed acceptable validity (Blakley, 2019; Jebb, Cole, Doman, Murgatroyd, & Prenctice, 2000). Also the SECA 213 Stadiometer scores high on reliability and is found to be valid (Baharudin et al., 2017).Mini-Mental State Examination

The MMSE evaluates the cognitive function in a range from zero to 30, whereby lower scores indicate greater cognitive impairment (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975; Logsdon et al., 2002). In the first part, the orientation of the participant is tested, followed by a retention test. Attention and calculation are also checked, just as questions about language and constructive capacity (Baek, Kim, Park, & Kim, 2016). The method is shown to have satisfactory test-retest reliability and construct validity. The validity of the MMSE was compared against a variety of gold standards that identify and measure cognitive impairment, such as DSM-III-R criteria and

activities of daily living measures. MMSE has acceptable sensitivity and specificity to detect mild to moderate stages of dementia (Tombaugh & McIntyre, 1992).

Physical activity variables

Two variables for PA were used in the analysis: sedentary time expressed in percentage spent per day and time in MVPA also expressed in percentage spent per day. MVPA is defined as more than 3.0 metabolic equivalents (METs). MET is the amount of energy that a certain physical effort takes (Copeland & Esliger, 2009). Both variables were assessed by using model GT3X of the Actigraph accelerometers. The activity monitors were attached to an elastic belt and placed above the right iliac crest for seven consecutive days. Instructions were given to the participants to wear the monitors all the time except while sleeping, bathing, swimming, or during other water activities. Data were collected within intervals of 30 seconds and a minimum recording of 10 hours on at least four days, of which one weekend day, was considered as valid data. Sixty minutes of consecutive zeros was considered as non-wear time. The data were processed with the Actilife software. Sedentary time was defined as 100 counts/min and MVPA as at least 1041 counts/min according to Copeland and Esliger (2009).

The interinstrument reliability of the Actigraph GT3X is high for raw count and derived intensity outputs, except for vigorous and very vigorous activity. Reliability therefore decreases beyond moderate intensities. So, MVPA displays stronger interinstrument reliability in the GT3X activity monitors than individual intensity categories (Jarrett, Fitzgerald, & Routen, 2015). The GT3X accelerometer is proved to be a valid method of assessing PA (Pulakka et al., 2013).

The study of Gardiner and colleagues (2011) found that the total sedentary time measured with the ActiGraph model GT1M has good repeatability and modest validity and is sufficiently responsive to change, which might imply that it is also suitable for older adults. According to Robusto and Trost (2012) the generations GT1M and GT3X of the ActiGraph provided comparable outputs thus making it acceptable for researchers to use different ActiGraph models within a given study. But caution is necessary because in a recent study it is suspected that the criteria researchers use for classifying the epoch as sedentary instead of as non-wear time, can be different for older adults than for younger ones. It is not clear yet what the required number of hours and days of wear for valid estimates of sedentary time in older adults is

(Heesch, Hill, Aguilar-Farias, van Uffelen, & Pavey, 2018).

Physical fitness variables

Two tests for physical fitness were used in the analysis: the 2-minute Step Test to assess aerobic endurance and the handgrip strength test for handgrip strength.

2-minute Step Test

The Senior Fitness Test aims to evaluate the global fitness status of older people. This battery of tests consists of six assessments, namely lower and upper limb strength and flexibility, balance, endurance, and agility and all have good reliability (Rikli & Jones, 2013). One of the six items is the 6-minute Walk Test which is established in distance (meters) and reflects aerobic endurance. If this is not feasible for the participant, the 2-minute Step Test is used which measures the number of full steps completed in two minutes. The participant raises his knee to the required height, namely the point midway between the kneecap and the iliac crest. The score is equal to the number of correct raises with the right knee (Jones & Rikli, 2002). Validity for this test was good and checked by comparing it with a gold standard, namely the 1-mile walk time (Langhammer & Stanghelle, 2015).

Handgrip strength test

The grip strength dynamometer is useful for testing the maximum isometric strength of the hand and forearm muscles (Wood, 2009). It is a possible tool for the measurement of upper body and overall strength (Litchfield, 2013). The handgrip strength was measured by the participant using the grip strength dynamometer of the brand Jamar plus in the right hand because for all the participants this was the dominant hand. The participant was seated with the shoulder and flexed elbow at 90º without supporting the arm on the body and the forearm in the neutral position, and pulse between zero and 30° of dorsiflexion.The test was performed three times and only the best value was included in the database. According to Hamilton, McDonald, and Chenier (1992) the grip strength dynamometer exhibits good within-instrument reliability. The validity of the grip strength measurement is acceptable and can be utilized with confidence.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms

To measure neuropsychiatric symptoms the Neuropsychiatric Inventory, NPI-Q, was used. The NPI-Q is a questionnaire filled out by the caregiver via an interview to measure the neuropsychiatric symptoms of the patient. Ten symptoms are measured: delusions, hallucinations, agitation/aggression, depression/dysphoria, anxiety, euphoria, apathy, disinhibition, irritability/lability, and aberrant motor activity. For each symptom the caregiver responds with ‘yes’ or ‘no’. If the answer is yes, the caregiver rates the frequency on a four-point Likert scale (one to four) and gravity on a three-four-point Likert scale (one to three) whereby a lower score on the Likert scale represents less frequent symptoms and less severe symptoms respectively. Frequency and gravity are multiplied to result in a score per symptom. At the end, a total score is made and may range from zero to 36, where higher scores represent

Quality of life

The Quality of Life in Alzheimer's disease (QoL-AD) is used to check the QoL in patients with dementia. The questionnaire is completed by the patient via an interview and measures 13 different aspects of QoL on a four-point Likert scale (weak, reasonable, good, great): physical health, energy, mood, living situation, memory, family, marriage, friends, self as a whole, ability to do chores around the house, ability to do things for fun, money, and life as a whole. All the scores of the QoL-AD are added up and divided by 13 to get the total score of the patient. The QoL-AD seems to be reliable and valid for individuals with MMSE scores higher than 10. In addition, the study of Logsdon and colleagues (2002) demonstrated that it is feasible for individuals with mild to moderate dementia to reliably and validly rate their own QoL. There is also the QoL-AD reported by the caregiver in which the caregiver fills in the same questionnaire for the patient, also via an interview. Again, the 13 scores of the QoL-AD are added up and divided by 13 to get the total score of the patient from the perspective of the caregiver. From these two different perspectives, one weighted composite score is made with the formula (2*patient + caregiver)/3 (Logsdon, Gibbons, McCurry, & Teri, 1999). For the statistical analyses all three total outcomes were used: QoL reported by the patient, QoL reported by the caregiver and the composite QoL total score.

2.3 Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 26.0. For all the statistical analyses a 0.05 level of statistical significance was used. For the sample of 26 participants, the frequencies were checked to see if there were outliers or missing values. For the variable ‘percentage time in MVPA’ two outliers were found and removed. For the smaller sample of 19 participants, two outliers were found and removed for the variabele ‘BMI’. The continuous variable MMSE was recoded into two categories: 11-20 (moderate dementia) and 21-25 (mild dementia) (Perneczky et al., 11-2006). The continuous variable BMI was recoded into four categories: <18.5 (underweight), 18.5-24.9 (normal), 25-29.9 (overweight) and ≥30 (obesity) (WHOb, 2020). Before starting the analysis, potential quantitative confounders were explored via correlation analysis, after normality tests were conducted for each of these variables. Number of medication was included as a confounding variable for neuropsychiatric symptoms (p=0.04) and QoL reported by the caregiver (p=0.01). Furthermore, Independent Samples T and Mann-Whitney U tests were carried out to see if there were significant differences between the two MMSE subgroups. Also, the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was performed to compare the mean handgrip strength values of both men and women with the general Portuguese population values and to compare the 2-minute Step Test values of both men and women with the global population values.

A mediating analysis was performed on the baseline data. Mediating analyses are used to test hypotheses about diverse intervening mechanisms by which causal effects function (Hayes, 2013). First, the main associations between MMSE and neuropsychiatric symptoms, and MMSE and QoL were examined (τ-coefficient). The results of these analyses were the answer to the first research question. Second, the mediating roles of PA and physical fitness were examined using the product-of-coefficients test of MacKinnon which consisted of three steps. The first step was the estimation of the associations between MMSE and the potential mediators PA and physical fitness (α-coefficients or a-path). The second step was the estimation of the associations between the potential mediator PA and neuropsychiatric symptoms and between the potential mediator physical fitness and QoL (β-coefficients or b-path), with adjustment for the MMSE variable. The last step was the calculation of the product-of-coefficients (αβ), which represented the mediating effect of PA and physical fitness (MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007). The potential qualitative confounder gender was explored during the mediating analyses by adding this variable in the analysis and removing it again when it was clear that this variable had no confounding effect on the associations. Statistical significance of the mediated effects was estimated by dividing αβ by its standard error (SE). The Sobel test was used for calculating SE with the formula: SE(αβ)=√(α2*SE(β)2+β2*SE(α)2) (Sobel, 1982). By dividing αβ by the τ-coefficient, the percentage that mediated the associations between MMSE and neuropsychiatric symptoms and QoL was obtained.

2.4 Ethical aspects

The research project was approved by the ethics committee of Ghent University in Belgium, process no. BC-07471 and BC-07472. The global research ‘Body and Brain’, of which this

research project is a part of, was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Sports of the University of Porto, under the reference CEFADE22.2018 and by the Foundation for Science and Technology in Portugal, under the reference POCI-01-0145-FEDER-031808. The research was registered on the website ClinicalTrials.gov with Identifier: NCT04095962. All the participants and their caregivers had to agree to participate in the study and therefore signed the informed consent form. Withdrawing from the study was permitted at any time during the research process. The exposure of the participants was minimized by coding and anonymizing the collected data and by using data exclusively for research purposes.

3. Results

Descriptive statistics

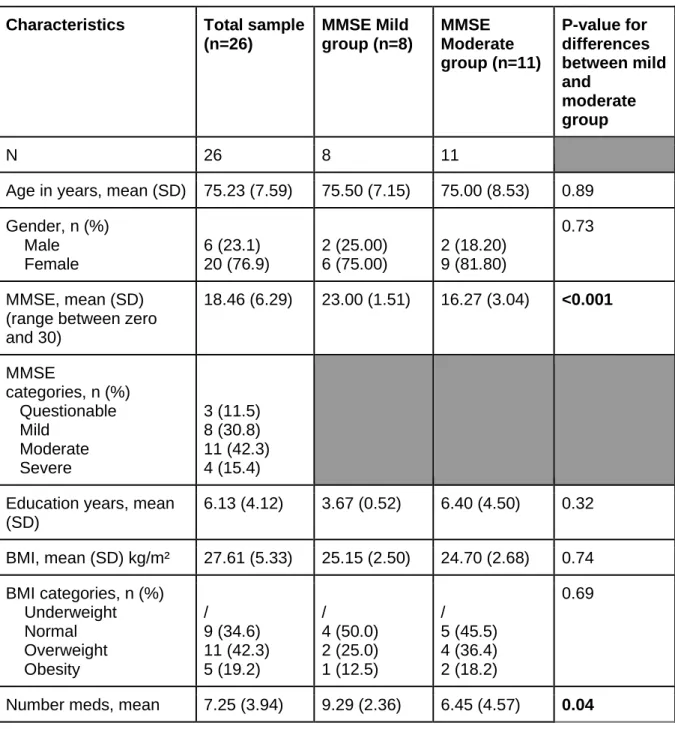

Twenty-six elderly people participated in the baseline measurements with a mean age of 75.23 ± 7.59 years. The mean values or percentages of the important variables are presented in Table 1 in the second column. In the third and fourth column, a division is made between mild and moderate dementia (total n=19). Only the participants of the mild and moderate group were included in the mediating analyses. In the last column the p-values for the differences between the mild and moderate group were reported. Only for the variables MMSE and the amount of medication, significant differences were found. These values are shown in bold.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of the study participants

Characteristics Total sample

(n=26) MMSE Mild group (n=8) MMSE Moderate group (n=11) P-value for differences between mild and moderate group N 26 8 11

Age in years, mean (SD) 75.23 (7.59) 75.50 (7.15) 75.00 (8.53) 0.89 Gender, n (%) Male Female 6 (23.1) 20 (76.9) 2 (25.00) 6 (75.00) 2 (18.20) 9 (81.80) 0.73 MMSE, mean (SD) (range between zero and 30) 18.46 (6.29) 23.00 (1.51) 16.27 (3.04) <0.001 MMSE categories, n (%) Questionable Mild Moderate Severe 3 (11.5) 8 (30.8) 11 (42.3) 4 (15.4) Education years, mean

(SD) 6.13 (4.12) 3.67 (0.52) 6.40 (4.50) 0.32 BMI, mean (SD) kg/m² 27.61 (5.33) 25.15 (2.50) 24.70 (2.68) 0.74 BMI categories, n (%) Underweight Normal Overweight Obesity / 9 (34.6) 11 (42.3) 5 (19.2) / 4 (50.0) 2 (25.0) 1 (12.5) / 5 (45.5) 4 (36.4) 2 (18.2) 0.69

(SD) Diagnosis, n (%) Not applicable Alzheimer’s disease Vascular dementia Multiple etiologies Mild cognitive impairment Neurodegenerative Other 1 (3.8) 8 (30.8) 2 (7.7) 5 (19.2) 2 (7.7) 6 (23.1) 2 (7.7) / 1 (12.50) 1 (12.50) 1 (12.50) 2 (25.00) 3 (37.50) / / 6 (54.40) 1 (9.10) / / 3 (27.30) 1 (9.10) 0.30

Total score QoL, mean (SD) (range between zero and 52)

Total score patient Total score caregiver

29.54 (4.07) 30.23 (5.41) 28.15 (3.79) 31.17 (2.29) 31.00 (2.93) 31.50 (2.33) 27.48 (3.97) 28.18 (5.88) 26.09 (2.43) NPI Total, mean (SD)

(range between zero and 36) 13.12 (8.91) 9.38 (6.09) 16.18 (7.97) Percentage of sedentary time, mean (SD) Percentage of time in MVPA, mean (SD) 77.26 (11.95) 0.47 (0.53) 75.95 (14.08) 0.46 (0.36) 79.50 (8.82) 0.57 (0.72) 2-minute Step Test,

mean (SD)

Right handgrip best value, mean (SD) 62.65 (20.75) 20.70 (6.25) 67.88 (24.49) 21.69 (7.89) 55.27 (18.85) 19.60 (6.05)

N: number of participants, P-value: calculated probability, SD: Standard Deviation, MMSE: Mini-Mental State Examination, %: percentage, BMI: Body Mass Index, QoL: Quality of Life, NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory, MVPA: Moderate to vigorous physical activity

To analyse if our sample was similar to the general Portuguese population and the global population, some comparisons were made. The handgrip strength values of the general Portuguese population aged 65 or older were 30.3 ± 9.2 Kgf for men and 18 ± 5.4 Kgf for women (Mendes et al., 2017). In the total sample the mean right handgrip strength values were 26.73 ± 9.83 Kgf for men and 18.81 ± 4.89 Kgf for women. It became clear that the results of the handgrip strength test were comparable between the general Portuguese population aged 65 or older and our sample. The 2-minute Step Test values of the global population aged 60 or older were 93 ± 25 for men and 83 ± 25 for women (Rikli & Jones, 1999). The mean values of the 2-minute Step Test were 66 ± 36.72 for men and 59.13 ± 17.51 for women. When comparing the results of this physical fitness test, only aerobic endurance was comparable

the female global population aged 60 or above and our female sample. So, the values of our female sample were below the global reference values.

Association between physical activity, neuropsychiatric symptoms and MMSE

1. Association between cognitive function stage and neuropsychiatric symptoms (τ-coefficient)

First, the association between cognitive function stage and neuropsychiatric symptoms was analysed (τ-coefficient). There was no significant association between cognitive function stage and neuropsychiatric symptoms (Beta=6.51, SE=3.54, 95% CI (confidence interval)= -0.43;13.45), which means that there was no difference in neuropsychiatric symptoms between elderly people with mild cognitive function and elderly people with moderate cognitive function.

2. Associations between cognitive function stage and potential mediators (α-coefficients)

There was no significant association between cognitive function stage and sedentary time (Beta=5.29, SE=6.11, 95% CI=-6.67;17.26) and between cognitive function stage and MVPA (Beta=-0.15, SE=0.32, 95% CI=-0.78;0.48).

3. Associations between potential mediators and neuropsychiatric symptoms (β-coefficients)

There was no significant association between sedentary time and neuropsychiatric symptoms (Beta=-0.09, SE=0.15, 95% CI=-0.39;0.21). However, for MVPA, there was a significant positive association with neuropsychiatric symptoms (Beta=9.10, SE=2.21, 95% CI=4.77;13.43). For each additional percentage MVPA, there was an increase of 9.10 in the total score of neuropsychiatric symptoms.

4. Mediating effect of physical activity on the associations between cognitive function stage and neuropsychiatric symptoms (αβ-coefficients)

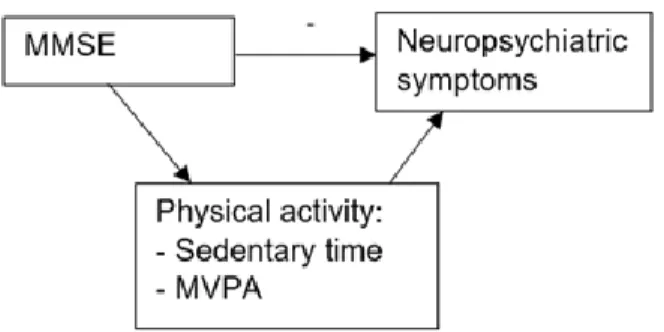

Figure one shows a visual presentation of the possible mediators on the association between cognitive function stage and neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Figure 1: Visual presentation of the possible mediators of the association between MMSE & neuropsychiatric symptoms

Sedentary time did not significantly mediate the association between cognitive function stage and neuropsychiatric symptoms (Beta=-0.49, SE=0.99, 95% CI=-2.43;1.45). Also MVPA did not significantly mediate the association between cognitive function stage and neuropsychiatric symptoms (Beta=-1.37, SE=2.96, 95% CI=-7.17;4.42).

Association between physical fitness, quality of life and MMSE

1. Association between cognitive function stage and quality of life (τ-coefficient)

Hereafter, the associations between the subgroups of cognitive function stage and QoL were analysed. There was a significant positive association between cognitive function stage and QoL reported by the caregiver (Beta=-5.02, SE=1.27, 95% CI=-7.50;-2.54). The mean score of QoL reported by the caregiver for the elderly people with moderate dementia was 5.02 points lower than the mean score of QoL reported by the caregiver for the elderly people with mild dementia. For QoL reported by the patient, there was no significant difference between the mild and moderate dementia group (Beta=-2.82, SE=2.27, 95% CI=-7.27;1.63). There was also a significant positive association between cognitive function stage and QoL total score (Beta=-3.68; SE=1.57, 95% CI=-6.76;-0.60). The mean QoL total score for the elderly people with moderate dementia was 3.68 points lower than the mean QoL total score for the elderly people with mild dementia.

2. Associations between cognitive function stage and potential mediators (α-coefficients)

There was no significant association between cognitive function and physical fitness measured by the 2-minute Step Test (Beta=-20.20, SE=10.33, 95% CI=-40.45;0.05 with confounder & Beta=-12.60, SE=9.92, 95% CI=-32.05;6.84 without confounder) and between cognitive function stage and physical fitness measured by the handgrip strength test (Beta=-1.97,

3. Associations between potential mediators and quality of life (β-coefficients)

There were no significant associations between physical fitness measured by the 2-minute Step Test and QoL reported by the caregiver (Beta=-0.03, SE=0.03, 95% CI=-0.09;0.04), QoL reported by the patient 0.06, SE=0.06, 95% CI=-0.17;0.05) and QoL total score (Beta=-0.05, SE=0.04, 95% CI=-0.13;0.02). There were no significant associations between physical fitness measured by the handgrip strength test and QoL reported by the caregiver (Beta=-0.04, SE=0.09, 95% 0.22;0.14), QoL reported by the patient (Beta=-0.16, SE=0.17, 95% CI=-0.50;0.19) and QoL total score (Beta=-0.11, SE=0.12, 95% CI= -0.35;0.12).

4. Mediating effect of physical fitness on the associations between cognitive function stage and quality of life (αβ-coefficients)

Figure two shows a visual presentation of the possible mediators on the association between cognitive function stage and QoL.

Figure 2: Visual presentations of the possible mediators of the association between MMSE & QoL

The patient’s physical fitness, measured by the 2-Minute Step Test, did not significantly mediate neither the association between cognitive function stage and QoL reported by the caregiver (Beta=0.55, SE=0.70, 95% CI=-0.83;1.93), nor the association between cognitive function stage and QoL reported by the patient (Beta=0.76, SE=0.91, 95% CI=-1.04;2.55), nor did it mediate the association between cognitive function stage and QoL total score (Beta=0.66, SE=0.70, 95% CI=-0.71;2.02).

The patient’s physical fitness, measured by the handgrip strength test, did not significantly mediate the association between cognitive function stage and QoL reported by the caregiver (Beta=0.08, SE=0.23, 95% CI=-0.38;0.54), nor the association between cognitive function stage and QoL reported by the patient (Beta=0.32, SE=0.61, 95% CI=-0.88;1.53), nor the association between cognitive function stage and QoL total score (Beta=0.23, SE=0.44, 95% CI=-0.62;1.09).

4. Discussion

We examined if there was a negative association between cognitive function stage of elderly people with dementia and neuropsychiatric symptoms and if there was a positive association between cognitive function stage of elderly people with dementia and QoL. On top of that, we explored if PA variables, sedentary time and MVPA, and physical fitness, measured by the 2-minute Step Test and the handgrip strength test, were significant mediators on the association between cognitive function stage and neuropsychiatric symptoms and between cognitive function stage and QoL respectively. The results of our research were not completely as they were postulated in the first and second hypotheses. No significant association was found between cognitive function stage and neuropsychiatric symptoms and no significant association was found between cognitive function stage and QoL reported by the patient. However, a significant positive association was found between cognitive function stage and QoL reported by the caregiver and between cognitive function stage and QoL total score. PA and physical fitness were no significant mediators on the associations between cognitive function stage and neuropsychiatric symptoms, and between cognitive function stage and QoL respectively. Throughout the discussion, we will elaborate on the different associations that were examined.

In this study, there was no significant association between cognitive function stage and neuropsychiatric symptoms in contrast to the research of Lo and colleagues (2019) who stated that there was a negative correlation in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. A possible explanation could be that the occurrence of neuropsychiatric symptoms do not depend only on the stage of dementia, but also on the type of dementia. For example, a study of Srikanth and colleagues (2005) found that neuropsychiatric behaviours could differentiate between Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia, and frontotemporal dementia. Different symptoms occur in different types of dementia. More recently, Chiu, Tsai, Chen, Chen, and Lai (2016) studied neuropsychiatric symptoms among three types of

dementia. This study showed that symptoms in Parkinson’s disease dementia are similar to those in Alzheimer’s disease but not to those in Lewy body dementia.

No significant association was found between cognitive function stage and sedentary time. The meta-analysis of Maasakkers et al. (2020), who analysed five studies about the association between cognitive function and sedentary behaviour, also showed no significant association between these two variables. The studies included in this review measured sedentary time by accelerometers or questionnaires. Maasakkers et al. (2020) concluded that specific types of sedentary behaviour, such as watching television or reading, may have a different influence on cognitive function and that further research is recommended. The study of Hamer and Stamatakis (2014) confirmed this and says that watching television may be associated with lower cognitive function and using the internet with higher cognitive function. So, as we measured the total time sedentary time spent per day without taking into account the context, this might explain the non-significant association.

Further in our research, no significant association was found between cognitive function stage and MVPA. This is in line with the study of Vásquez and colleagues (2017) among 7.478 adults aged 45 to 74 years. The cognitive tests used in this study were more extensive than in our study, but the results were the same. Despite these results, the study of Zhu et al. (2017) did find a significant positive association between cognitive function stage and MVPA. A possible explanation could be the larger sample size of more than 6.000 participants in comparison to our sample. Another explanation for the absence of a significant association in our study could be the low percentage time spent in MVPA by the participants. Obviously, this low percentage could influence our results.

Moreover, no significant association was found between sedentary time and neuropsychiatric symptoms. The study of Hamer and Stamatakis (2014) stated that there was no association between sedentary behaviours and a change in depressive symptoms, but of course not only depressive symptoms were investigated in our research so this might only explain a part of our result. To continue, a significant positive association was found between neuropsychiatric symptoms and MVPA. For each additional percentage MVPA, there was an increase of 9.09 in the total score of neuropsychiatric symptoms. We are not sure what the exact reason is for this unexpected outcome. Possibly wandering, walking around without knowing what you are doing, may influence the percentage time in MVPA because this is in some cases a result of Alzheimer’s disease and the according neuropsychiatric symptoms (Logsdon et al., 1998). Presumably in part this can explain the higher MVPA, however, this is just a hypothesis and needs further investigation.

There was only a significant positive association between cognitive function stage and QoL reported by the caregiver and QoL total score, but not with QoL reported by the patient. Normally individuals with mild to moderate dementia can reliably and validly rate their own QoL (Logsdon et al., 2002). The studies of Kazazi and colleagues (2018), and Missotten and colleagues (2008) stated respectively that the better the cognitive function, the better the health-related QoL and that MMSE has a significant impact on QoL whereby people with dementia have a lower QoL than people with mild cognitive impairment. So, based on this research, the expected result was thus the more severe the symptoms of dementia, the lower the QoL of the person with dementia. Contrary to our expectations, this was only present for QoL reported by the caregiver and for QoL total score. A possible reason for this result may be that the burden for the caregiver is higher for patients with more severe symptoms so that they would rate the QoL of the patient lower than the patient would rate his own QoL. Logsdon et al. (2002) found that caregivers’ reports of QoL of the patient were affected by their own experiences and level of burden with a negative bias as a result. Furthermore, Conde-Sala, Garre-Olmo, Turró-Garriga, López-Pousa, and Vilalta-Franch (2009) concluded that the degree of caregiver burden was inversely correlated with the QoL-AD. The appraisal of QoL may also be influenced by the perception of the caregiver about the level of cognitive functioning of the patient with dementia while scoring the QoL of this patient. When looking for reasons for the significant difference in QoL total score between the two groups, the calculation method of QoL total score is probably responsible for this result because the QoL total score is based on the perceptions of both caregiver and patient.

Furthermore, for cognitive function stage and physical fitness, measured by the 2-minute Step Test and the handgrip strength test, no significant associations were found as well. This is in contrast with different studies who did find significant positive associations (Alosco et al., 2012; Fritz, McCarthy, & Adamo, 2017; Jang & Kim, 2015; Plácido et al., 2019). The similarities between our study and these studies are the used measuring instruments. The greatest difference is the larger sample size of the other studies, on which we will elaborate further in the discussion.

For QoL reported by the caregiver, QoL reported by the patient and QoL total score no significantassociations were found with physical fitness measured by the two tests which is in contrast to our expectations and recent findings (Arrieta et al., 2018; Hsu et al., 2014). No significant associations were found between aerobic endurance and any of the QoL variables

elderly females. The difference in results may be due to the fact that different measures were used for QoL and aerobic endurance. The review of Bohannon (2019), about grip strength as a predictor of QoL, found inconsistency about this topic. A possible reason for the different findings could be the lack of standardized testing. Different studies use different procedures or cut points which can explain the inconsistent results (Bohannon, 2019).

In the end, sedentary time and MVPA did not significantly mediate the association between cognitive function stage and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Also physical fitness, measured by the two tests, was no significant mediator on the associations between cognitive function stage and QoL reported by the caregiver, by the patient, and total score. However, no studies have already performed mediating analyses related to this topic. A few studies have already taken the same variables into account, but explored other research questions instead of mediating analyses (Arrieta et al., 2018; Hsu et al., 2014; Sampaio et al., 2020; Sobol et al., 2018).

Unfortunately, this study has some limitations which can be possible explanations for the results that were found. The first limitation is the small sample size of only 19 participants which may result in insufficient power to detect significant results. It is possible that including more participants would reveal significant results. Also, due to the small sample size the results of this study may not be representative of the elderly population with dementia in Portugal. This can also be due to the higher percentage of women compared to the percentage of men and to the high percentage of overweight participants in the sample. A second limitation is the occurrence of selection bias. One exclusion criterium of this study was to be involved in regular PA programs. So, some participants were more likely to be selected than others, namely elderly people who spent almost no time in their day in MVPA, with the result that the study population is not representative of the target population (Nour & Plourde, 2018). A third limitation might be that only persons with mild and moderate dementia were compared, so it could be that, if more stages were included, more significant differences would have been found for several variables (e.g. neuropsychiatric symptoms, QoL, PA, etc.). At last, it might be that other confounders might have been relevant to include in the analyses. For example, the social network of the participants could have been explored, as this is an important influencing factor for the patients’ QoL and PA (Raggi et al., 2016; Soósová, 2016; Josey & Moore, 2018). However, no data for social network were available.

The main strength of this study is that it is one of the first studies that conducted research about the associations or the mediating effect of these specific variables of PA and physical fitness on neuropsychiatric symptoms and QoL, suggesting it can be an important contribution to literature. Another strength is that for both PA and physical fitness two indicators were

involved in the analyses instead of only one, which means that multiple aspects are taken into account. A third strength is the focus on elderly people with dementia. These people are an important target group since dementia is viewed as the greatest global challenge for health and social care in the 21st century (Livingston et al., 2017). Including the amount of medication as a confounder in the analyses is another strength. For the elderly people with symptoms or a diagnosis of dementia and certainly for the persons with neuropsychiatric symptoms, many pharmaceuticals are prescribed by the physician, such as galantamine, memantine or antidepressants (Alzheimer’s Society, 2020). The use of these pharmaceuticals may have a lot of side effects which may be one of the reasons that medication was a confounding factor for some of the associations. To end, PA is measured by using accelerometers in this research which makes the research more objectively.

5. Conclusion

This study is relevant to practice as it contributes to a better understanding of the associations of how PA variables, sedentary time and MVPA, and physical fitness, measured by 2-minute Step Test and handgrip strength test, seems to influence the association between cognitive function stage and neuropsychiatric symptoms, and the association between cognitive function stage and QoL respectively. There appears to be only a significant positive association between cognitive function stage and QoL reported by the caregiver and between cognitive function stage and the QoL total score. It seems that there is no mediating effect of PA and physical fitness on the association between cognitive function stage and neuropsychiatric symptoms and between cognitive function stage and QoL respectively in Portuguese elderly people with dementia. Future studies should explore if similar research findings are found among a larger sample size.

Various recommendations can be made for further research, of which some were already mentioned in the discussion. First, further research could investigate the influence of specific subtypes of sedentary behaviour (e.g. watching television, reading, etc.) on cognitive functioning. Another recommendation is to collect data about the possible confounder social network by, for example, using a questionnaire which also covers this topic. Also, light PA could be used as an outcome variable in future research instead of MVPA because elderly people are more physically active in light intensities than in moderate to vigorous intensities. Furthermore, instead of investigating the influence of PA and physical fitness via cross-sectional data, future longitudinal studies could investigate the effect of an intervention to promote PA and enhance physical fitness on neuropsychiatric symptoms and QoL in elderly