ATTITUDES TOWARDS NATIVE AND

NON-NATIVE ACCENTS OF ENGLISH

A Comparative View From Flanders and the UK

Word count: 24,312

Marieke Martens

Student number: 01606298Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Stef Slembrouck

A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics and Literature

2

Acknowledgements

This thesis is the product of what has occupied most of my mind for the past couple of months. Finishing this thesis during a pandemic proved to be extra challenging. The mental pressure of conducting research and writing during a global health crisis, on top of a ‘usual’ stressful master year, did not make things easier. Not only did the workload suddenly shift from classes and exams to papers and online Zoom-seminars, the lack of social activities resulted in a ‘never not working’ situation. Nonetheless, the nurses and doctors who have been working for months on end kept me grounded and made me realise I should count my blessings.

Of course, this thesis would not have been possible without the help of others. First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor Prof. Dr. Stef Slembrouck, whose knowledge and advise have helped me tremendously in the writing process. I enjoyed discussing linguistic matters and interpreting the data, as well as following his sociolinguistic classes which gave me the right basis to finish this thesis. A thank you goes to Dr. Ludovic De Cuypere, who has helped me with the data incorporation and visualisation. I would also like to thank the people who shared my surveys via Facebook, and the many respondents who filled them out. Next, my parents and friends deserve to be thanked. They were the ones to push me forward or stop me from pushing myself too far. Lastly, a special thank you goes to my boyfriend Daan, for discussing linguistic developments and ideas with me, for reading every word, sentence and paragraph of this thesis, for motivating me, pushing me forward, and inspiring me to become a better writer and (aspiring) scientist. All in all, this thesis has confirmed the reason why I started studying Linguistics and Literature in the first place: I am deeply passionate and curious about languages.

3

Abstract

In sociolinguistic research, attitudes towards native varieties have long been at the centre of attention. However, in recent years, attention has gone to non-native varieties as well. Newly emerging local varieties cannot be accounted for by a colonial history or large-scale immigration. In the context of globalisation and English as a lingua franca, academic interest goes out to the attitudes towards those local varieties. This study contributes to attitudinal research on those new varieties in the Expanding Circle of English, by conducting a quantitative study on the attitudes of 155 Flemish and 77 British people towards different English accents, i.e. a light Flemish accent (LF), a heavy Flemish (HF) accent, a heavy Dutch (HD) accent and a Received Pronunciation (RP) accent. An online survey was used to indirectly elicit attitudes towards the different (strengths of) accents by means of a matched-guise test. It was found that the Flemish respondents prefer the RP accent on both status and social attractiveness, followed by the LF accent, the HF accent and the HD accent. The degree of accentedness seemed to influence the ratings negatively. We argue that the Flemish are still exonormatively oriented towards the native standard, but the tolerance for LF seems to suggest a normative evolution towards an acceptance of the local Flemish accent. What the British respondents are concerned; the data show an acceptance of non-native accents. Remarkably, the native RP scored the least positively on almost all traits. The evaluations of the Brits reflect, amongst other influences, the virtue of localness in an increasingly globalised world.

Keywords: Attitudes, globalisation, non-native varieties, degree of accentedness

In sociolinguistic research, attitudes towards native varieties have long been at the centre of attention. However, in recent years, attention has gone to non-native varieties as well. The emergence of non-native varieties as English became the lingua franca across the world, no longer all have roots in a colonial past. This study contributes to research on those emerging new varieties in the Expanding Circle of English, by conducting a quantitative study of the attitudes of 155 Flemish and 77 British people towards different English accents, i.e. a light Flemish accent (LF), a heavy Flemish (HF)accent, a heavy Dutch (HD accent and a Received Pronunciation (RP) accent. An online survey was to indirectly elicit attitudes towards the different (strengths of) accents by means of a matched-guise test. The results showed the Flemish respondents prefer the RP accent on both status and social attractiveness, followed by the LF accent, the HF accent and the HD accent. The degree of accentedness influenced the ratings negatively. We argue the Flemish are exonormatively still oriented towards the native standard, but the tolerance to LF seems to suggest a normative evolution. For the British respondents, the data show an acceptance of non-native accents. Remarkably, the native RP scored the least positive on almost all traits. The British evaluations reflect, amongst other influences, the virtue of localness in an increasingly globalised world.

Keywords: Attitudes, globalisation, non-native varieties, degree of accentedness

In sociolinguistic research, attitudes towards native varieties have long been at the centre of attention. However, in recent years, attention has gone to non-native varieties as well. The emergence of non-native varieties as English became the lingua franca across the world, no longer

4

Table of Contents

Abstract ... 3

List of Abbreviations ... 6

List of Figures ... 7

List of Tables ... 8

1 Introduction ... 9

2 Literature review ... 12

2.1 World Englishes Paradigm ... 12

2.2 Defining language attitudes ... 13

2.3 Measuring language attitudes ... 14

2.3.1 Direct Approach ... 14

2.3.2 Indirect approach: Matched & Verbal Guise Test ... 14

2.3.3 Strengths and Weaknesses of the Matched Guise Test ... 15

2.4 Previous Research on Language Attitudes ... 16

2.4.1 Native Speakers’ Language Attitudes ... 17

2.4.2 Non-Native Speaker’s Language Attitudes ... 20

2.4.3 Attitudinal Studies in Flanders and The Netherlands ... 21

3 Research Questions, Hypotheses & Methodology ... 25

3.1 Research Questions and Hypotheses ... 25

3.2 Design of the Survey ... 25

3.2.1 Ethics: Introduction with Consent ... 26

3.2.2 Matched Guise Test ... 26

3.3.2.1 Selection Recorded Speech Samples ... 26

3.3.2.3 Selection of Traits for the Semantic Differential Scale... 28

3.2.3 Background Information Section ... 29

3.2.3.1 Informants ... 29

3.2.3.2 Social Variables ... 29

3.2.3.3 Familiarity Scores ... 30

3.4 Data Collection Procedure ... 31

3.4.1 Rationale for an Online Survey ... 31

3.4.2 Sharing Procedure ... 31

3.5 Incorporation of the data ... 32

4. Results and Discussion... 34

4.1. Flemish Attitudes ... 34

4.1.1 Attitudes to LF & RP: Light Flemish is Okay, but RP stays Best... 34

4.1.1.1 Linguistic Landscape in Flanders ... 35

4.1.1.2 Standard Language Ideology ‘Transfer’ to RP ... 37

4.1.1.3 LF’s Covert Prestige in Late Modernity ... 39

4.1.2 Attitudes to HF & HD: the Flemish In-Group and the Dutch Out-Group ... 42

4.1.2.1 Negative Impact of Degree of Accentedness ... 42

5

4.2 British ratings ... 45

4.2.1 Attitudes to RP: North-South Division in the UK ... 47

4.2.1.1 The Social Evaluation of RP ... 47

4.2.1.2 Methodological Considerations: Unmasking the Guise ... 48

4.2.2 Attitudes to LF & HF & HD: Localness as Virtue ... 50

4.2.2.1 British Social Norms in Favour of Acceptance... 50

4.2.2.2 Linguistic Background of Respondents ... 51

4.2.2.3 Social Stereotypes & Intergroup Relations between the UK, Flanders and The Netherlands ... 52

4.3 The Impact of Sociolinguistic Factors ... 53

4.3.1 Familiarity ... 53 4.3.2 Gender ... 59 4.3.3 Age ... 59

5 Conclusion ... 64

5.1. The ‘What’-Question ... 64 5.2 The ‘Why’-Question ... 655.3 Limitations, Implications & Suggestions for Further Research ... 66

6 References ... 69

6

List of Abbreviations

ELF English as a Lingua Franca

ESL English as a Second Language

EFL English as a Foreign Language

GA GA

RP Received Pronunciation

NS Native Speaker

NNS Non-Native Speaker

UK United Kingdom

MGT Matched Guise Technique

VGT Verbal Guise Technique

ENL English as a Native Language

L1 First Language

L2 Second Language

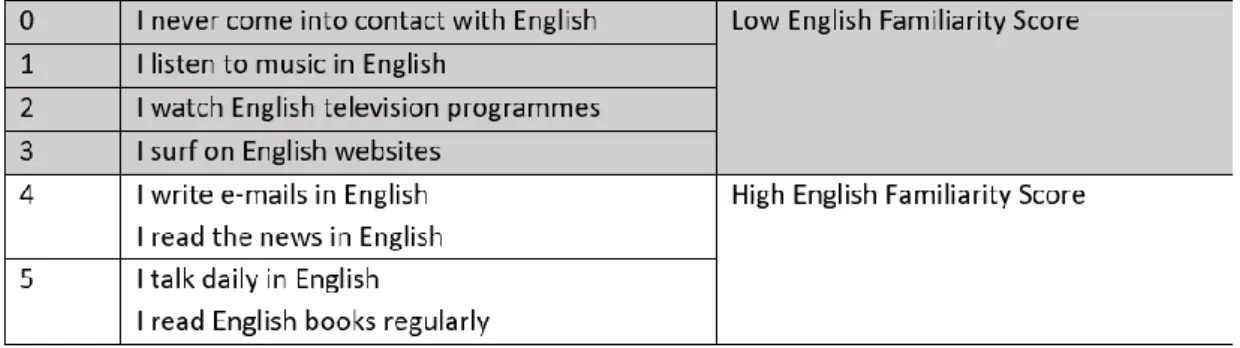

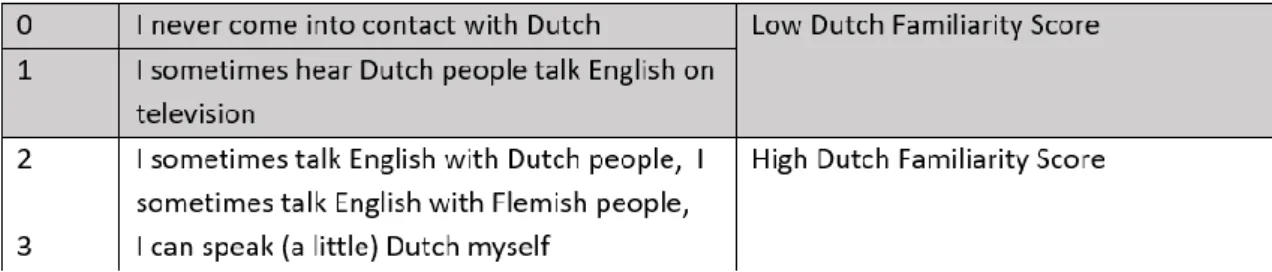

EFS English Familiarity Score DFS Dutch Familiarity Score

7

List of Figures

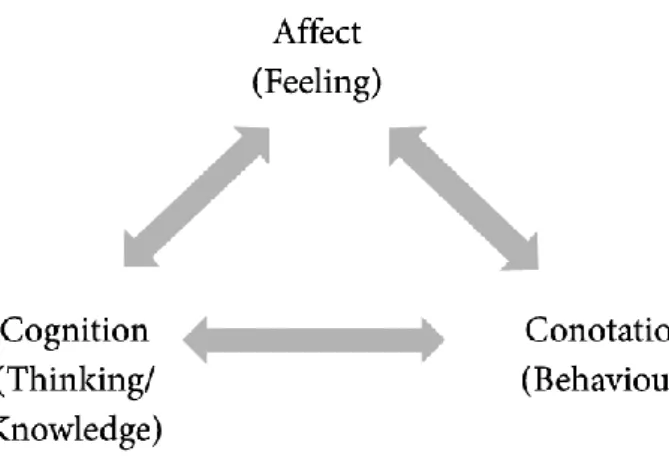

Figure 1 Three Components of Attitudes ... 14

Figure 2 Example Visualisation ... 33

Figure 3 Flemish Ratings ... 35

Figure 4 British Ratings ... 46

Figure 5 Flemish Ratings – Low Familiarity English ... 54

Figure 6 Flemish Ratings – Low Familiarity English ... 54

Figure 7 British Ratings – Low Familiarity Score ... 56

Figure 8 British Ratings – High Familiarity Score ... 56

Figure 9 Flemish Female Ratings ... 57

Figure 10 Flemish Male Ratings ... 57

Figure 11 British Female Ratings ... 58

Figure 12 British Male Ratings ... 58

Figure 13 Flemish Ratings 18-40... 60

Figure 14 Flemish Ratings 40-60... 60

Figure 15 British Ratings 18-40 ... 61

8

List of Tables

Table 1 Distribution Gender and Age of Respondents ... 29 Table 2 English Familiarity Score ... 30 Table 3 Dutch Familiarity Score ... 31

9

1 Introduction

English is expected to become progressively more significant in Europe, even post-Brexit. On the contrary, in post-Brexit Europe, the sociolinguistic space for European varieties of English will become more distinctive, “given the absence of Britain as an arbiter of correctness and standardization”(Modiano, 2017:314). The growing status of English on continental Europe cannot be accounted for by colonial history or large-scale immigration of Inner Circle speakers (cf. infra) (Modiano, 2017). Instead, large-scale acquisition of English on the continent is the result of major efforts to pursue proficiency in an ever-more useful lingua franca: the English language. Within Europe, English serves a myriad of functions: “governmental, educational, informational, and work-related functions” as well as “an increasing utility in the creation of intellectual properties” (Modiano, 2017: 314). Against the international backdrop of English as a lingua franca (ELF), new varieties are emerging in the multilingual community of continental Europe (ibid.). The term ‘New Englishes’ has been used to refer to these new ‘nativized’ or ‘indigenised’ varieties that are used to express social identity (ibid.). Academic attention has increasingly gone to the emergence of endonormative varieties in Outer Circle countries, i.e. varieties which normatively focus ‘inwards’. The question remains whether native varieties should still be used as a model for learners of English in the European Expanding Circle countries (cf. infra) (Kachru, 1983). Even though the native standard is still prevalent in a lot of non-native speech communities, many researchers advocate for more tolerance for non-non-native varieties of English (Jenkins, 2009:137; Kachru, 1992), as many English as second (ESL) and foreign language (EFL) learners cannot attain or master a native accent, such as General American (GA) or Received Pronunciation (RP) (Nejjari et al., 2012). Instead, researchers argue English nowadays belongs those who want to speak it. As research has shown, evolving norms and innovations prototypically emerge in spoken language first (Ghyselen, 2017). Researchers have also highlighted the lacuna in research on non-native variants of English, particularly the English spoken in countries of the Expanding Circle (Kachru, 1983). They also point to the relevance of the degree of accentedness/foreignness and the need for more research in this subfield (Van Meurs & Hendriks, 2017). Attitudes towards native and non-native accents are significant and are worthy of investigation since they are part of a powerful stereotyping construct in the mind of the general public.

This thesis intends to answer the following question: with growing numbers of non-native speakers of English and the emergence of new local normative varieties of the language, what are the attitudes towards native and non-native accents by both native (NS) and non-native speakers (NNS)? In other words, do speakers of the Expanding Circle countries feel like they still have to adhere to an exonormative standard and how do native speakers feel about those new emerging varieties?

10 Furthermore, does the degree of accentedness play a role in the evaluation? This study focuses on two specific speech communities: first, the United Kingdom (UK), an Inner Circle country, and second, Belgium, an Expanding Circle country. We concentrate on Belgium, and more specifically its Dutch-speaking region of Flanders, because it has received little to no attention in studies on newly emerging varieties of English. This is remarkable, perhaps, since a great deal of similar research on so called Dutch English, Dutch-accented English or ‘Dunglish’ has been conducted in the Netherlands (Edwards, 2016). I would argue that researching Belgian Dutch English – what some would also call Flemish English or ‘Flemenglish’ – is valuable and worthwhile because Flemings are not only highly proficient in English, meaning they might develop their own endonormative standard in the future, but also considering the comparative potentialities of attitudinal data from the two neighbouring regions, Flanders and The Netherlands, due to their shared history (linguistic and other).The English language trickles down in many areas of Flanders’ society. As Dutch belongs to the West-German language group as well, English is quite easy to learn for Flemish people (Goethals, 1997). Series and films are spoken in English (Flanders is known as a ‘subbing’ community), English songs are prevalent (Goethals, 1997), and in most restaurants English menus are available. The language is taught from the age of 14, yet, in contrast to the Netherlands, it does have to be noted the higher education systems generally still focus on Dutch (Simon, 2005; Edwards, 2016). In professional contexts, employees are expected to have a high level of English proficiency to function in international communication. According to Education First’s 2019 English Proficiency Index, 65,01% of Flemings are ‘very high in proficiency’, in contrast to the French speaking population in Wallonia, which scored 58,77% (‘English Proficiency Index’)

This thesis investigates attitudes of Flemish and British respondents towards different accents by means of empirical-experimental methods. The accents that were chosen to elicit these attitudes were three non-native ones, viz. two Flemish English and one Dutch English accent, together with one native accent, Received Pronunciation (RP). The non-native accents imitated degrees of ‘accentedness’ or ‘foreignness’. Dutch and Flemish speakers have a transfer from their Dutch mother/native language (L1), or one of its dialects. It results in a typical ‘Dunglish/Nederengels’ or ‘Flemenglish/Vlengels’ pronunciation of English which consists of a combination of American and British features as well as some typical Dutch mother tongue transfers such as the r-colouring, devoicing of all final obstruents, th-stopping, and the lack of an /e ~ æ/ contrast (Nejjari et al, 2012). Van den Doel (2006:57-64) gives an extensive overview of features of Dutch-accented English. On one recording respondents could hear a Flemish-flavoured pronunciation closer to the standard (more towards RP) and a second and third showed much more distinct features of the speaker’s L1, i.e. the northern Dutch variety and the southern Flemish variety. The experiment involved 156 Flemish and 77 British respondents and was conducted by an online survey and an indirect measuring technique called the matched guise

11 technique (henceforth MGT), developed by Lambert, Hodgson, Gardner, and Fillenbaum (1960), the workings of which we will extensively address in chapter 3. This study hopes to fill some gaps in academic knowledge by (1) focussing on an as yet largely unexplored second language (L2) variety of an Expanding Circle country, i.e. Belgium and Flemish-accented English (2) examining both non-native (Flemish) and native speaker (British) perspectives and (3) incorporating different degrees of accentedness (heavy accented ‘Flemenglish’ and heavy accented ‘Dunglish’).

After this introductory chapter, chapter 2 will provide a general discussion of the study of language attitudes. Subsequently, the different ways of measuring will be discussed. A more in-depth presentation of the strengths and weaknesses of the MGT will be included as well. Chapter 2 also gives a short overview on previous research on attitudes towards different English contexts, in which both the native and non-native speakers’ attitudes will be given attention. Additionally, the chapter will explore research in Dutch and English contexts, which will offer an important theoretical and empirical background for the design, method and analysis of the present study. Chapter 3 will focus on methodology. First of all, the research questions and certain hypotheses will be stated. The second part accounts for reasoning behind the choice of the indirect measurement technique and the design of the survey. The chapter also explains how the data were processed and which programs were used. Chapter 4 discusses our results. The main findings for the data collected on Flemish participants’ attitudes will be presented and compared to relevant attitudinal research in similar contexts. Next, the section takes up the same format for the British respondents’ attitudes towards the different accents. The chapter explores some of the factors which might have influenced the results. Subsequently, the social background factors familiarity, age and gender will be considered. Lastly, chapter 5 offers a summary of the experiment and its key findings. It will also include certain limitations that came with this study highlights the contributions it makes to the overall field of research and provides suggestions for further research.

12

2 Literature review

2.1 World Englishes Paradigm

This study is situated within the ‘World Englishes paradigm’, the sociolinguistic discipline that examines the international position of English in various language communities (Ghyselen, 2017:264). Several approaches have been put forward to conceptualise the spread of English around the world, such as McArthur’s Circle Model of World English (2001), Schneider’s Dynamic Model of Postcolonial English (2007) and Kachru’s Circle Model (1992). The varieties under investigation are labelled based on the latter (Kachru, 1992), a theoretical model which proved highly influential within the World Englishes paradigm (Ghyselen, 2017:264).

Kachru’s Circle Model (1992) is a comprehensive schematic representation of the spread, acquisition and use of English. The Inner Circle represents the traditional basis of English, comprising of regions in which it acts as a primary language. Nations such as UK, Ireland, Australia, South Africa and Canada come to mind. Speakers of the Inner Circle have English as a native language (ENL). In the Outer Circle, English has a special status as an ‘official’ language: it is the main language to carry on the affairs of government, education, commerce, the media and it is spoken as a second language (ESL). This category encompasses over 75 territories, such as India, Bangladesh or Pakistan in which English is selected to avoid a choice between one of many indigenous languages. According to Kachru (1992), the Outer Circle consists of nations with a colonial background. Lastly, the Expanding Circle encompasses countries where English is learnt as a foreign language (EFL) in schools and institutions of higher education. In terms of normative standards, the ENL varieties are seen to be ‘norm-providing’. In contrast, the ESL varieties as ‘norm-developing’; i.e., “their users are seen as agentively shaping the language for their own sociocultural ends” (Edwards & Laporte, 2015:136). The EFL varieties are seen as ‘norm dependent’, they are considered ‘learner’ varieties whose speakers look at ENL varieties as a target norm (Edwards & Laporte, 2015:136). Examples are the Englishes that are spoken in many European countries, such as France or Germany.

This model has received some criticism as well (e.g. see Jenkins 2009). Critics of Kachru’s model point to its categorisation of nations instead of populations. Moreover, some scholars indicate that in the context of globalisation, English can be used as a second language outside postcolonial contexts. (Modiano, 2017). Researchers argue these clear-cut distinctions may not be applicable anymore, since European varieties of English appear to be increasingly endonormative and thus likely to develop their own norms in the future (Modiano, 2017). For example, some scholars have argued that English in the Netherlands has shifted from EFL status to ESL status (cf. Edwards 2016). Others, however, contradict this hypothesis by stating that, while Dutch people do have passive knowledge, this does not

13 automatically infer that the majority of Dutch people are effectively bilingual (cf. Ghyselen 2017). For the purposes of this thesis, we will categorise the English of the UK as ENL, the English of the Flemish as EFL and the status of English in the Netherlands as somewhere between the EFL and ESL spectrum, on the grounds that boundaries between the circles can be fluid.

2.2 Defining language attitudes

Before engaging in a specific discussion on the field of research mainly interested in language attitudes towards different varieties, it is necessary to establish from the outset what we mean by ‘language attitudes’. Multiple definitions of this notion have been suggested throughout the years. To name one or two examples, while Allport (1935:801) defined ‘attitude’ as “a learned disposition to think, feel and behave towards a person (or object) in a particular way”, Ryan and Giles (1982:7) consider it to be “any affective, cognitive or behavioural index of evaluative reactions towards different language varieties or speakers”. In this thesis, we will adopt Garett’s definition (2005:1251), in which ‘attitude’ entails “prejudice held against or in favour of regional or social varieties of language” as well as “allegiances and affiliative feelings towards one’s own or other groups’ speech norms and stereotypes of speech styles within sociolinguistic communities”. Garrett’s interpretation specifically classifies “regional or social varieties of language” (ibid.), which is useful for this study, because of the focus on the perception of English varieties of different regions . Moreover, Garret’s particular viewpoint is relevant in light of the often-heard claim that reactions are generally not aimed at the different varieties as such, but concern the speaker and, by extension, the whole speech community to which he or she belongs (e.g. Baker, 1992; Trudgill, 1999; Garrett, 2010). Moreover, attitudes are believed to be stable and tend to be longer lasting if they are acquired early in life (Garrett, 2010).

Attitudes are often conceptualised as having three components, which all influence one another: cognition, affect and behaviour (Figure 1). Firstly, attitudes are cognitive because they deal with thoughts and beliefs about the world, and “the relationship between objects of social significance” (Garrett, 2010:23) (e.g. a person that speaks dialectal tends to be associated with low-status jobs). Secondly, attitudes are affective, as they always come with certain feelings towards language varieties. Those feelings tend to be scalar: we may severely dislike a certain accent or only mildly dislike it. Thirdly, attitudes are seen as having a behavioural component as well, in that they influence a tendency to act in a certain way (e.g. a person may or may not hire a certain individual because their accent makes them seem less professional). Other underlying factors to language attitudes include ideology, habits, beliefs or social stereotypes (Garrett, 2010). All these components to language attitudes

14 ultimately make them challenging to research, particularly when placed along the methodological difficulties of certain measuring techniques which we will present in section 2.3.

2.3 Measuring language attitudes

Three broad approaches to study linguistic attitudes can be identified: direct measures, indirect measures, and the analysis of societal treatment of language varieties. We shall discuss only the former.

2.3.1 Direct Approach

As the name of this approach suggests, people are directly asked for their evaluations (Garrett, 2010:39). Informants explicitly express their opinions on different languages, accents and other linguistic phenomena. Additionally, a Likert scale is sometimes used, which allows participants to indicate how strongly they ‘agree’ or ‘disagree’ with the statements on a certain continuum (cf. e.g. Baker’s study on explicit attitudes towards bilingualism in Wales 1992). Evidently, respondents are aware that their opinions will be used as data, a realisation which may trigger the so-called ‘social desirability bias’ (Garrett, 2010:38), which leads respondents to change their attitudes in favour of the ‘socially desirable’ answer. Because of this, a direct approach to measure language attitudes is sometimes avoided.

2.3.2 Indirect approach: Matched & Verbal Guise Test

The indirect approach – also known as the ‘speaker evaluation paradigm’ – indirectly tries to elicit the participants’ beliefs on language use, which researchers who prefer this method believe to be impossible to draw out explicitly (Garrett, 2010). Since Lambert et al.’s introduced the test in 1960, the influential matched guise technique (MGT) has become widely used as a means to measure attitudes indirectly. Traditionally, respondents listen and evaluate a recording of one single speaker, who is fluent in two or more varieties – fluent enough, even, so that they pass off as a native speaker (Lambert et al., 1960; Giles, 1970; Baker, 1992; Garrett, 2010). The goal is to make the recordings in all ways

15 identical, except for the accent the speaker uses. This also means that the speaker has to go to great lengths to eliminate other features of speech such as intonation, speed and pauses. Most often, that speaker will be evaluated by respondents on two main attributes, viz. status and social solidarity (Chien, 2018). Since respondents often do not know the real object of study (and will sometimes even be told they hear different speakers), this particular test is able to subtly asses covert language attitudes.

A similar method is the verbal guise technique (VGT), in which the recordings are made by different native speakers, the obvious advantage of which is the ability to represent the accents accurately and authentically every single time (Garrett, 2010). On the other hand, however, the technique cannot guarantee the elimination of other speech qualities such as intonation, tone of voice, etc. because there are different speakers involved in every recording.

The MGT has been used to study numerous languages and varieties (cf. 2.4) (Garrett, 2010). Recently, more scholars have started to encourage the use of the MGT as a means to compare non-native with other native and non-native English accents (McKenzie, 2015). This study attempts to respond to those calls by offering a comparative view between non-native and native accents.

2.3.3 Strengths and Weaknesses of the Matched Guise Test

Naturally, the MGT comes with its own strengths and weaknesses. In Attitudes to Language (2010), Garrett considers the indirectness of the MGT as one of its main affordances. In contrast to the direct method, the MGT aims to elicit private attitudes and thus avoids the ‘social desirability’ bias. By employing the same speaker in each accented recording – ‘matching the guises’ – the MGT eliminates the influence of other background variables such as voice quality and ensures that speaker-evaluations are only a reflection of attitudes towards accent. Additionally, comparability of findings is possible, as the MGT has been used in an extensive number of studies internationally. Due to the rich history of attitudinal studies, researchers “have been able to establish the main dimensions of language evaluation (prestige, social attractiveness and dynamism), thereby also contributing to our sociolinguistic understanding of language variation” (Garrett 2010:57). Most importantly, “it has provided foundations for research at the interface of sociolinguistics and the social psychology of language”, which, according to Garret, is one of its most important accomplishments (ibid.)

Notwithstanding, the MGT has not been spared from critique or controversy. Several issues have been raised by Garrett (2010):

• The salience question: concerns have been voiced regarding the vocal representations of the language varieties (Garrett, 2010:57). Some researchers argue that recordings may exaggerate certain features of language variations.

16 • The style-authenticity question: in most studies, the recorded audio is a reading of a written text. However, one cannot be sure the text of a relatively formal style will be evaluated the same way as more spontaneous speech. Garrett (ibid.) argues “the style implications of reading aloud for the preparation of speech samples for attitude studies has tended to be ignored or overlooked”.

• The neutrality question: the choice of text itself raises questions as well. The ideal text is generally claimed to be ‘factually neutral’ – e.g. a route description – because such texts prevent content-related evaluations. Nevertheless, as Garrett argues, “one needs to be mindful of the limitations to the effectiveness of this. Given the ways in which we interpret texts as we read them, drawing upon pre-existing social schemata, the concept of a ‘factually neutral’ text cannot be assumed to be unproblematic” (2010:59).

• The perception question: it must be acknowledged that the respondents might identify the accents incorrectly. Some criticism has therefore been raised concerning the ‘perception question’ (Garrett, 2010:58). In order to resolve this issue, respondents are at times asked to identify the accent they heard.

• The accent-authenticity question: in spite of the relative stability of factors such as intonation, stress, rhythm or rate of speech, these features may co-opt with accent characteristics (ibid.). The RP accent, for instance, comes with a more pronounced intonation pattern. In minimising such perceived paralingual features to stand out less against another accent, however, the recorded RP intonation might be ‘blander’ than in natural speech.

• The mimicking-authenticity question: this question is about dubious accuracy. As Garrett indicates, respondents might notice a voice to be ‘odd’ in some way, regardless of an accent-validating pilot test, because inaccuracies can always occur when people are asked to mimic varieties that are not their own (ibid.).

That being said, the MGT’s influence can hardly be overlooked. It has played a major role in research on language attitudes from the 1960s onwards and has strengths we can most definitely exploit in this study. While the case remains, the technique has received just criticism, as any research method invariably does. After all, there is no perfect research method. They can, inevitably, only ever achieve partially reliable and valid results

2.4 Previous Research on Language Attitudes

Language attitudes are generally analysed in light of two central concepts: status and solidarity (Garrett, 2010:66). The status dimension is linked to prestige and evaluated on traits such as intelligence, competence and education. The other dimension, solidarity, is associated with integrity, social attractiveness and friendliness. Those two dimensions act as ‘paired opposites’ of the personality

17 traits: where one dimension is strong, the other is weak and vice versa. They are generally measured on a bipolar semantic-differential scale (Preston and Robinson, 2005: 7), the “type of attitude-rating scales most typically used […]. They need only involve using equidistant numbers on a scale (e.g. 1 to 7) with semantically opposing labels applied to each end (e.g. friendly-unfriendly)” (Garret, 2010:55). The biggest difference between a Likert scale and semantic-differential scale is that the former asks respondents to agree or disagree with a certain statement, whereas the latter requires the respondents to complete a statement, offering two polarising traits applied to each end (e.g. friendly-unfriendly)(Garrett, 2010).

2.4.1 Native Speakers’ Language Attitudes

Research on language attitudes has focused largely on the Inner Circle English speaking countries, including Canada (e.g. Lambert et al., 1960), Australia (Ball, 1983; Bayard et al., 2001), the USA (e.g. Preston, 1999) and the UK (e.g. Garrett et al., 2003; Coupland and Bishop, 2007). One of the first major works on language attitudes has been conducted some sixty years ago, in 1960, when Lambert, Hodgson, Gardner, and Fillenbaum introduced the MGT to measure language attitudes. Their research intended to elicit attitudes towards French and English in the French part of Canada. Recordings of the same text were made by bilingual speakers both in English and French. The respondents evaluated the speakers on a six-point scale with regard to the speaker’s intelligence, ambition, kindness and so on (Garrett, 2010: 70). They concluded the English speaker was rated more positively on most traits by both the French and English speakers . Moreover, the French respondents were less tolerable towards French than the English respondents were. Lambert et al. used that last finding as evidence for “a minority group reaction on the part of the French speaking respondents” (Garrett, 2010:71). Lambert et al.’s study has set the tone for the study of language attitudes around the globe in the following decades (Garrett, 2010:71).

In the case of the USA, a study by Preston (1999) showed that attitudes to different accents in the USA are largely based on the regionality of the varieties. His investigations focused on the responses of Michigan college students who identified and evaluated fourteen dialect areas of the USA. Preston found that salient accents from the southern states are rated quite unfavourably, in particular due to associations with rural poverty, low education standards and low levels of intelligence, and take comfort in social attractiveness, while regions of great linguistic security are judged highly in terms of status. Furthermore, the standard model of American English is usually rated more positively on the status dimension than other regional accents such as Mexican American English, Spanish accented English or African American English, which are prejudiced-against varieties (Preston, 1999).

18 Multiple studies have been carried out in Australia, as well. In his seminal study (1983) of Tasmanian Psychology students, for instance, Ball asked his informants to evaluate RP, Glasgow, Scots, Australian, and French accents on 7-point bipolar scales and a socio-economic status scale. The data showed the Anglo-Australians rated RP highly with regard to status, but low in social attractiveness. The local Australian accent was evaluated as quite incompetent but very socially attractive. Non-native accents were rated as well: a German accent was assessed to be more attractive than standard voices, and as more competent than other non-native accents. General American was regarded as prestigious as well. Another example is the verbal guise test study of Bayard et al. (2001) which researched the opinions of Inner Circle university students within New Zealand, Australia and the United States towards New Zealand English, Australian English, American English and RP. The NSs strongly favoured the American accent on the status and power dimensions, which might indicate shifting standards from the previously highly regarded RP to American English as the preferred variety. This might imply that GA is now more and more recognised as the international standard amongst NSs (Bayard et al., 2001). Bayard et al. (2001) noted the students’ positive attitudes might be the result of widespread exposure to American media.

If we shift our gaze to the UK, the speech community this thesis focuses on, we will notice a considerate amount of studies have been conducted in the region (e.g. Giles, 1970; Giles, 1971; Giles & Coupland, 1991; Milroy, 2002; Hiraga, 2005; Coupland & Bischop, 2007; McKenzie, 2015). Traditional research showed that the native speakers of English hold negative attitudes towards urban non-standard varieties. The most stigmatised varieties are the vernaculars spoken by the working class in industrial centres such as Liverpool (Scouse accent), Birmingham (Brummie) or Glasgow (Glaswegian) (Giles & Coupland, 1991; Milroy, 2002). The industrialised centres are traditionally associated with high levels of poverty, low levels of education and a higher crime rate which might explain the negative ratings. One of the most referenced varieties in research on British attitudes towards English varieties is RP or ‘the Queen’s English’, which is spoken by an elite social class (Coupland & Bishop, 2007). RP is usually associated with a relatively high social status, because of its association with education, power and prosperity. According to Crystal (2010), RP traditionally received top rankings for all positive values, not only for status but also for variables of solidarity. This may also derive from its prevalent status in English language teaching settings.

However, this tendency has changed significantly in the past decades, in Crystal’s (2010) view due to two major trends: an increase in positive attitudes towards certain regional accents and an increase in negative attitudes towards RP. Regional accents now attract more positive evaluations on solidarity markers such as ‘friendliness’ and ‘naturality’, and the RP accent is even regarded as ‘insincere’ and

19 ‘distant’ (Crystal, 2010:27). In recent years, non-standard varieties have begun to be perceived as much more socially attractive (Giles, 1970; Coupland & Bischop, 2007). The study of Giles (1971) shows that ‘accent loyalty’ has an influence on British speakers’ evaluations of regional dialects: informants from Wales for example, rated the Welsh dialect much more positively over RP with regard to social integrity traits such as “seriousness, talkativeness, good-naturedness and humorousness” (Giles, 1971:281). Giles further mentions that the evaluations might be influenced by “more diverse, yet nonetheless stereotyped, social qualities and temperaments characteristic of specific regional communities” (ibid.), next to evaluations which are based on social prestige. The RP accent still manages to score highly on variables relating to status and is still regarded as highly ‘educated’ and ‘competent’. Nonetheless, it receives negative judgements on solidarity dimensions by NSs from the UK. Hiraga (2005) found, for instance, that a rural Yorkshire accent is rated more positively on solidarity than RP on status, proving once again that accent loyalty is important for the British. Likewise, research by Coupland and Bischop (2007) indicated that regional accents of Newcastle and Southern Irish English are perceived as less standard than the Queens’ English but received more positive ratings on solidarity traits. The regional accents of the UK, i.e. the rural, non-standard accents, have gained a more public presencenot only because of the increased mobility of speakers but also through radio, television and new media, which in turn has led to an attitudinal change towards those individual accents (Crystal, 2010:28).

Together with the acceptance towards regional accents in the UK grew familiarity with non-native accents. An example is the “outsourcing of call centres to India” (Crystal, 2010: 32), where native speakers would hear an Indian accent on the phone. In the beginning, this did not always lead to positive reactions, yet, nowadays, most native Brits are used to it. Crystal (ibid.) questions whether these non-native accents will gain more positive ratings once people become more familiar with them. Research has shown the tendency of Inner Circle speakers to evaluate non-native speakers low in competence, but higher in social attractiveness. However, the results reveal British participants stigmatise non-native varieties, such as Indian English (e.g., Giles, 1970; McKenzie, 2015), French accented English (e.g., Giles, 1970; Coupland and Bishop, 2007), German accented English (e.g., Giles, 1970; Coupland and Bishop, 2007), Chinese accented English (e.g., McKenzie, 2015) and Japanese accented English (e.g., McKenzie, 2015). The study by Giles (1970) showed the Indian English was systematically rated lower than the other varieties such as South Welsh English or Scottish Standard English in both status and solidarity dimensions. Chien (2018) states that indicates “the speech of NNSs is generally denigrated in comparison to British English dialects spoken by people in the UK” (p. 43), which other research has pointed to as well (Giles 1970; Lippi-Green, 1994; Coupland and Bishop, 2007; McKenzie, 2015). The studies show that L1 speakers transfer negative attitudes towards a foreign accent into negative attitudes towards speakers of the accent and vice versa. Some scholars showed

20 that negative evaluations of a speaker’s accent influence the perceived aptness for higher end jobs: native speakers are judged to be more suitable for higher-end job positions than non-native speaker (Nejjari et. al, 2012). Lindemann (2002: 426-434) also found that negative attitudes have an impact on the communicative behaviour of native speakers, in that they regularly pretend not to understand L2 speakers and are inclined to interrupt L2 speakers more often than L1 speakers.

Even though non-standard speech is prejudiced against, non-standard English varieties are recurrently rated positively on traits associated with personal integrity or social attractiveness, such as friendliness, trustworthiness or honesty (e.g. Preston, 1999). Moreover, the solidarity mechanism towards standard dialects is enforced when the respondents themselves are speakers of a non-standard dialect, due to its community identity and language loyalty. Put differently, in-group identity plays a vital role in the evaluation of non-standard varieties (e.g. Giles, 1971). Point in case is a study by Preston (1999), where the Southern US English speakers thought of their own regional accent as a marker of solidarity, identity and local values and consequently rated their own variety higher on solidarity markers as casualness, friendliness, and politeness than varieties spoken in the North. Likewise, in another study, New Zealanders rated New Zealand English higher on social attractiveness than RP or North American English because of in-group solidarity (Bayard et al., 2001).

In sum, two general observations can be put forward in a review of the vast body of literature on attitudes towards English varieties: (1) standard varieties are generally perceived as prestigious1 and

secondly while (2) standard varieties score high on social attractiveness by both native and non-native speakers.The uniformity of these evaluation patterns is remarkable. Edwards (1999: 102-103) offers some of the possible explanations for this pattern. It may be the case that language attitudes reflect intrinsic beliefs about the linguistic superiority and inferiority of various varieties. Perhaps, aesthetic qualities have an influence too, where some varieties are considered gentler than others or as having a potentially attractive sing-song intonation (McKenzie, 2010: 57). Although those views might be held by the general public, linguists generally agree that no variety is in any way superior to others (ibid.). In the next section, we shall explore whether the aforementioned pattern is found in research towards non-native speakers’ language attitudes as well.

2.4.2 Non-Native Speaker’s Language Attitudes

Many language studies have focused on either NS to NS or NS to NNS interactional contexts (McKenzie, 2010: 58). McKenzie notes that the majority of studies which focused on non-native attitudes “ignored

1

In the present study, the terms ‘standard’ and ‘non-standard’ are seen as sociopsychological constructions and the process of standardisation is considered an ideological development in itself (McKenzie, 2010:54). We also want to remark that the notions of ‘legitimacy’ and ‘correctness’ are viewed as a social construct too (ibid.).

21 evaluations of the social and geographical variation within Englishes, whether of the inner, the outer or the expanding circle of English use. The tendency has been to investigate non-native speaker attitudes towards ‘the English language’, conceptualised as a single entity” (McKenzie, 2010: 58). Research towards ‘the English language’ showed that generally, respondents have a positive attitude towards English, although the negative influence of the spread of English on indigenous languages has been noted. However, over the last couple of years, the field has seen a surge in interest on NNS attitudes towards various English varieties.

The overall findings of attitudinal studies on NNS show that, similarly to the native speakers, the native Inner Circle varieties such as GA and RP are rated more positively in terms of status, and non-native varieties are rated more positively with regard to social attractiveness (Dalton-Puffer et al., 1997; Ladegaard, 1998; Chien, 2018; McKenzie, 2015). Dalton-Puffer et al. (1997) used the verbal guise technique to examine the attitudes of university students of English in Austria, who had to rate Austrian English non-native accents, GA, RP and ‘near-RP’ accents. The results indicate an overall preference for the native accent. The researchers explain the preference for RP in particular by the respondents’ familiarity with the accent (it is the variety generally used by English teachers in Austria). Ladegaard (1998) researched the attitudes of Danish secondary and university students towards five varieties (RP, GA, Cockney, General Australian and Scottish Standard English), by means of a verbal guise technique. By the same token, RP was the unmatched prestige variety, due to the focus on RP in Danish educational contexts. McKenzie argues the positive evaluations of RP can be linked to the learners’ familiarity through educational exposure – in a European context at least, RP is arguably the model for pronunciation amongst ESL learners – and the media. However, a general preference for inner circle varieties might also explain RP’s high score (2010: 62).

2.4.3 Attitudinal Studies in Flanders and The Netherlands

Research into attitudes towards English in a Flemish context is scarce. To our knowledge, no research has focused on native attitudes towards Flemish-accented English. Some studies have focused on opinions of Flemings towards English, often in light of an educational context with a focus on RP. Simon (2005) used Flemish students and a small number of university teachers as a target group to elicit their attitude towards the English pronunciation target for Flemish advanced learners of English. She questioned whether the until now prevailing pronunciation model of RP in both secondary and higher education is still tenable in contemporary Flemish society. The results of the survey she conducted, containing a number of multiple-choice questions, showed that “Flemish students of English appear to be very RP-oriented” (Simon, 2005:19). The vast majority of the lecturers expressed that it is important to speak with a native-like accent. Additionally, nearly all the students claimed that they aim at an RP-like variety of English, which led Simon to conclude that no change in the RP pronunciation model

22 seems to be detectable. However, she remarked that results could potentially be influenced by the particular target group used in her survey: “[It] should be kept in mind that the target group discussed in this paper is formed by students majoring in English at university level. Their aspirations as far as the mastering of English is concerned might be very different from those of students taking English as minor subject (14-15)”.

Like Simon, Goethals (1997) highlights that English pronunciation in Flanders is mainly following a British standard but seems increasingly by American influences” (110). In his article English in Flanders

(Belgium), Goethals indicated the existence of a Flemish variant of ‘educated European English’ –

sometimes referred to as ‘Flemenglish’ – which displays its own type of pronunciation together with a number of grammatical or lexical ‘errors’ and which is “as recognisably different from the Dutch English in the Netherlands as from the German or French Englishes” (ibid.).

Dewaele (2005), focused on Flemish students’ attitudes towards English and French. He found that Flemish students rated English much more positively. He linked this to their politico-cultural identity, which is influenced by tense socio-political relations between Dutch and French in Flanders. Dewaele also found that self-perceived competence lead to positive ratings, and ‘foreign language anxiety’, the unease and stress many language learners experience when learning a foreign language, might lead to negative ratings towards French (2005:133). Another factor he discussed is the self-proclaimed proficiency: “attitudes towards foreign languages are clearly determined by the individual’s perception of his/her capacity to sustain successful authentic and relatively error-free interactions in that language (i.e. without losing face)” (ibid.). Dewaele claims that an individual’s own favourable perception of proficiency results in improved attitudes towards a language and their community. The positive associations become an even stronger motivation to learn the foreign language, which in turn results in more frequent communication, higher levels of proficiency, more self-confidence and lower levels of communicative anxiety (2005: 134). In order to compare findings with Dewaele’s study, this thesis will consider the respective familiarity of the respondents with the language variety they hear.

Given the dearth of scholarly interest into ‘Flemenglish’, significantly more research has, by contrast, focused on the opinions of native and non-native speakers towards Dutch-accented English, which does offer comparative potentialities of attitudinal data from the two neighbouring regions, Flanders and the Netherlands. Van den Doel (2006) has shown that British and Americans respondents were annoyed with typical Dutch pronunciation ‘inaccuracies’ in that, to them, they were regarded as incomprehensible and unenjoyable. Nejjari et al. (2012)’s research is particularly interesting for the present study. They researched different reactions of British native speakers to Dutch-English accents

23 in a telephone sales talk. 144 highly educated British native speakers – consisting of a group both familiar and one unfamiliar with Dutch – rated a slight Dutch English accent, a heavier Dutch English accent and an RP accent not only with regard to personality traits, status and affect, but also on their intelligibility and comprehensibility. The study showed that RP was perceived higher in status than the Dutch-English accents, and the slight Dutch accent as well as the RP evoked more affect than the heavier Dutch English accents. Moreover, British respondents familiar with Dutch-accented English perceived the speakers with a heavier Dutch accent as lower in status than the ones who had no familiarity with Dutch accented English.

Hendriks et al. investigations (2016; 2017) suggest that not only native speakers rate the strong Dutch-accented English more negatively than a lighter Dutch-Dutch-accented English (cf. also Nejjari et al., 2012), but also that native speakers of French, German, Spanish and even Dutch are of this opinion. Therefore, the degree of accentedness should be considered, which is what the present study does. In a fairly recent study, Hendriks et al. (2016) investigated the Dutch university students’ evaluations of English-speaking lecturers’ competence, likability and dependability, and considered the degree of accentedness. Their results indicated moderately accented fragments were rated less positively than slight accented and native English ones, and slightly accented lecturers received more positive ratings concerning social attractiveness than those that were native accented. The authors explained these preferences by referring to an in-group solidarity mechanism, stating: “individuals are attracted to others if these others are felt to be similar to themselves.” (2016:11). Their study implies that having a ‘slight’ accent may lead to more positive ratings on social attractiveness by speakers with the same L1.

In a study from 2017, Hendriks et al. wanted to research how other EFL speakers would evaluate Dutch-accented English. They conducted a verbal guise experiment, consisting of three female speakers which represented three degrees of accentedness: strong/slight accented-Dutch and native-accented English. It became apparent that the strong accent triggered rather negative attitudinal evaluations, especially concerning competence, whereas the slight and native accent did not. Remarkably, the study found that the slightly accented non-native varieties received equal ratings as the native varieties regarding comprehension and attitudes. Hendriks et al. (2017) suggest the slight Dutch accent may be rated even more positively than a regional native English accent and emphasise the need for further research. They also highlight the need for follow-up studies on “the effect of degree of accentedness on both comprehensibility and attitudes for speakers with different L1 backgrounds”(61), a factor this study has included.

24 Another study by Hendriks et al. (2018) focused on the attitudes of Dutch and German students’ evaluations towards Dutch and German lecturers speaking English with a moderate non-native accent, a slight one and a native accent. The data indicated that the lecturers with a moderate non-native accents received less positive ratings than lecturers with a native accent. Their findings are interesting to our study, as they have focused on the opinions towards the accent of a typologically related languages. Hendriks et al. (2018) suggest lecturers who teach English should engage in pronunciation trainings to minimise their strong mother tongue features, but the researchers do note it is important to “to challenge non-native students' ideas about pronunciation standards” (61).

25

3 Research Questions, Hypotheses & Methodology

3.1 Research Questions and Hypotheses

This study will attempt to provide an answer to the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1: (a) Are native speakers more tolerant than non-native speakers towards different levels of accentedness of non-native speech? (b) What is the relative impact of the degree of accentedness?

RQ2: Do the scores of variables have any correlation with each other?

RQ3: (a) Does familiarity with the ‘foreign accent’ play a role in native speakers’ attitudes? Does familiarity with the ‘native accent’ play a role in non-native speakers’ attitudes? (b) do the background variables of gender and (c) age have an impact on the attitudes?

We can formulate some hypotheses (H), based on previous research discussed in chapter 2.

H1: Non-native speakers are expected to be more tolerant towards different degrees of foreignness. Non-native speakers will rate the non-native accents positively (especially on social attractiveness), in light of the contemporary status of English as a lingua franca and the rise of endonormative varieties. The native speakers will rate the non-native accents more negatively (especially on the status dimension), as foreign accents are generally prejudiced against by Inner Circle speakers.

H2: Negative attitudes towards non-native accents result in even more negative attitudes when the degree of accentedness is higher.

H3: We expect a correlation between status markers (i.e., variables concerning education, intelligence, culturedness, competence, authority) and solidarity markers (i.e. variables concerning friendliness, pleasantness, considerateness) as ‘paired opposites’: where one increases, the other decreases and vice versa.

H4: Familiarity with a particular language variety will result in more positive attitudes towards that variety.

3.2 Design of the Survey

The respondents voluntarily filled out a survey, which, apart from a brief introduction, consisted of two major parts: (1) a matched guise test which investigates the attitudes towards the recorded samples and (2) a background questionnaire.

26

3.2.1 Ethics: Introduction with Consent

A brief introduction on a separate welcoming page familiarised the respondents with the nature of the study. In order to prevent preconceptions, the introductory paragraph only briefly touched upon the research objective of evaluating respondents’ attitudes towards varieties of English. For both the Dutch and English surveys, potential respondents were informed that the study would be conducted anonymously, and the data would only be used for the academic purpose of a master thesis. The introduction ensured the respondents no wrong answers were possible, and they would be able to give feedback at the end, should they wish to do so. The closing statement specified that when informants proceeded to the next page of the survey, they gave their consent for participating in the research.

3.2.2 Matched Guise Test

Based on existing research into language attitudes, this thesis has used the MGT as an indirect method to examine Flemish and British participants’ implicit, mostly subconscious, perceptions. For the ‘control accent’ heavy Dutch, a verbal guise was employed, in order to ensure a natural sounding voice. Therefore, this study can be seen as using a mix between a MGT and a VGT, combining the advantages of both techniques. The respondents judged the different English accents on bipolar semantic-differential scales in the MGT and VGT studies. The application of the MGT and VGT offers the opportunity for comparison of the present results with existing studies discussed in chapter 2. Since the scale is gradable, this allows us to measure the ‘attitude intensity’. Strong attitudes towards particular accents are more likely to results in “resistance to change and to persist over a longer period of time” (Chien, 2018:81). The results of this study show the correlation between different accents and its effect on attitudes and the stereotypes that underlie listener’s perceptual judgements (cf. Chien, 2018).

3.3.2.1 Selection Recorded Speech Samples

The passage of the auditory stimulus used for this study, the first page of Lewis Caroll’s Alice in

Wonderland (1992), consists of 253 words (see Appendix A). Even though the advantages of a

spontaneous speech recording as auditory stimulus have been pointed out (McKenzie, 2010), in this study a read passage was chosen in order to avoid the effect of other lexical, syntactical or morphological variations. By using a pre-existing stimulus text, the length of the passage was controlled. Moreover, the passage could be re-recorded if necessary. The stimulus is neutral content-wise and is characterised by its lexical and grammatical simplicity. Alice in Wonderland is a children’s book, which made it comprehensible for both the native and non-native listener group. A neutral text is preferred in attitudinal research, as explicitly political or scientific texts might elicit other opinions which focus on content rather than accent.

27 In total four audio samples were recorded to represent the four different accents, of which three were matched guises and one a verbal guise. One Flemish woman produced the matched guises and one Dutch woman produced the verbal guise. Finding a speaker who could produce all four accents was challenging, “because one cannot be both a native and a non-native speaker of one language” (Nejjari et al., 2018: ). After a screening of four speakers (two female, two male), one woman’s guises were chosen as the most representative of the light Flemish, heavy Flemish and RP accent. The speaker is a native Flemish speaker who studies English literature and linguistics, and managed to adopt the RP accent in the course of secondary and higher education. She mastered the accent during an Erasmus experience in Cambridge. As the literature suggests, it is difficult to find a speaker who can mimic all variations, which this woman could produce almost perfectly. It was decided to include a heavy Dutch accent as a ‘control accent’, in order to assess whether or not native speakers of Flemish and English would rate the heavier variants differently. The Dutch variant was not produced by the first speaker, as it proved to be too difficult in the short amount of time: she would have to produce a familiar yet foreign accent in a foreign language, which led to an unnaturally sounding recording. Therefore, the choice was made to record the heavy Dutch variant separately by a native Dutch speaker from the Netherlands, who was selected out of three women who sent in a recording. Hence, this research also includes a verbal guise. However, since both speakers were young women with the same L1, other determining factors such as age, mother tongue, gender were hoped to be avoided. This supports earlier research which demonstrate that finding representative matches for both a non-native and native accent is difficult.

The first speaker was instructed to produce an RP accent, a heavier Flemish accent and a lighter Flemish accent. The speaker was able to produce the Flemish accent quite intuitively. According to her, “you hear [the accent] around you” and “they mock it on tv”. Even though multiple articles, books and handbooks reporting on the pronunciation difficulties for a native Flemish speaker can be found, there is no standard work for the ‘Flemenglish’ pronunciation, since it is not a separate variety of English, such as South African English or Singapore English. The same text sample (i.e., the first chapter of Alice

in Wonderland) was purposefully read in a quite neutral, perhaps even bland way, in order not to

distract listeners from the accent. The second speaker was instructed to read the text in a neutral way and only had to produce a heavy Dutch accent, which according to her “came naturally since a lot of older people talk like that”. Multiple tapes were recorded before deciding on the final audio sample. To test whether the matched guise ‘sounded native-like’, Nejjari et al. (2018) argue the assessments of native listeners are crucial to check whether the matched guises are in fact representative or not. To test representativeness, the 4 samples were evaluated on a degree of ‘nativeness’ by not only native ‘linguistically lay’ listener groups (an English, a Flemish and a Dutch native speaking group) but also a

28 group of trained experts from the Department of Linguistics at the University of Ghent. Both the ‘lay’ and ‘expert’ groups confirmed that the samples accurately represent the four variations, as closely as is possible in for the purpose of this research, and in a way which fulfils the research requirements Nejjari et al. (2019) put forward. However, some participants (4 people out of a total of 76 British listeners) commented on the RP accent: they noticed the speaker was not a native yet spoke very clearly and sounded “almost standard-like”. This might have to do with the very high education level of the commenters.

3.3.2.3 Selection of Traits for the Semantic Differential Scale

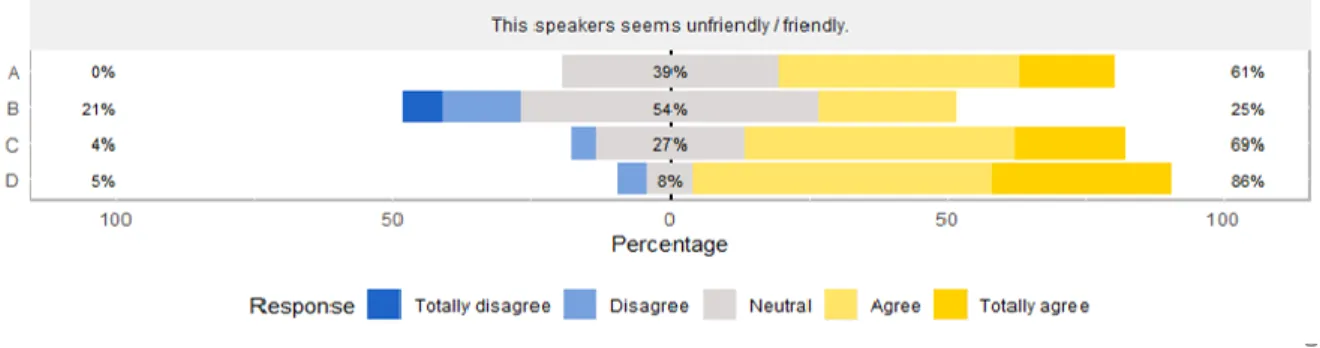

The choice of personality traits used in the semantic differential scale is central in the study of language attitudes. The semantic differential scale requires the respondents to complete a statement, and then offers two polarizing options and some middle options (Garrett, 2010). In our case, the statements were: I presume this speaker is…/ I think this speaker is…/ This speaker comes across as…/ This speakers sounds…/ This speaker seems…/ This speaker speaks…The nine traits were chosen on the basis of previous, similar research (Van der Haagen, 1998, Gerritsen et. al., 2000), but slightly adapted due to some idiomatic difficulties for the translation between Dutch and English. The nine semantic-differential scales were:

Incompetent (Onbekwaam) 1 2 3 4 5 Competent (Bekwaam)

Irritating (Vervelend) 1 2 3 4 5 Pleasant (Aangenaam)

Uneducated (Laagopgeleid) 1 2 3 4 5 Educated (Hoogopgeleid)

Inconsiderate (Ondoordacht) 1 2 3 4 5 Considerate (Bedachtzaam)

Stupid (Dom) 1 2 3 4 5 Intelligent (Intelligent)

Without authority (Zonder kennis van

zaken)

1 2 3 4 5 With authority (Met kennis van zaken)

Uncultured (Onbeschaafd) 1 2 3 4 5 Cultured (Beschaafd)

Unfriendly (Onvriendelijk) 1 2 3 4 5 Friendly (Vriendelijk)

Artificial (Gemaakt) 1 2 3 4 5 Natural (Natuurlijk)

The odd-numbered scale gave the respondents the option to opt out should they not have an opinion. Unfortunately, the Google Surveys software did not provide a separate option to opt out, so the guidance section on top of the page explained respondents could tick the middle option in case they had no strong opinion and/or wanted to opt out of that particular question. A careful translation of the traits in the Dutch survey allowed for a better comparison between the Dutch and English results. For example, inconsiderate-considerate does not have a Dutch literal translation, nor does Dutch have

29 the same semantic opposites, and the trait ‘with or without authority’ was translated to ‘met/zonder

kennis van zaken’. We placed the negative and positive differentials unevenly on different sides, to

avoid habituation when filling in the survey. Lastly, the participants had the option to add any comments or remarks in an open-end question.

3.2.3 Background Information Section

3.2.3.1 Informants

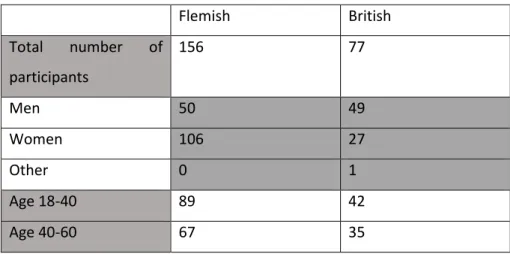

A total of 77 British respondents and 156 Flemish people filled out the survey. It proved to be more difficult to find British respondents, as the experiment was conducted online from Belgium. The Flemish group consisted of 106 women to 50 men, meaning generally 2/3 of the informants were women and 1/3 were men. The age variable is more balanced: 89 people belonged to a younger age category (18 to 40-year-olds) and 67 people belonged to an older age category (40 to 60 years old). The British respondents had a similar gender distribution: 49 women and 27 men filled out the survey, which corresponds to the 2/3 female to 1/3 male distribution found for the Flemish ratings. One person selected the option ‘other’. 42 British people belonged to the younger age category and 35 British informants can be placed in the older age category, a similar balance as that of the Flemish respondents. Table 1 presents an overview of the groups with respondents.

Table 1 Distribution Gender and Age of Respondents

3.2.3.2 Social Variables

The background survey required the respondents to fill out personal information such as gender, age, (English) education level, recognition and familiarity with the particular variety under investigation. Some questions, for example the one which focused on familiarity with English or Dutch, may have influenced the respondents’ self-perceptions of their English/Dutch proficiency. Therefore, the background survey was completed at the end of the experiment in order to prevent certain preconceptions from entering into the value judgements. The four Dutch surveys and four English surveys were almost identical, apart from the background information section. For instance, the

Flemish British Total number of participants 156 77 Men 50 49 Women 106 27 Other 0 1 Age 18-40 89 42 Age 40-60 67 35