ENGLISH

AS

AN

ATTRACTIVE

ALTERNATIVE FOR DUTCH: REASONS

FOR SPONTANEOUS USE OF ENGLISH

IN YOUNG FLEMISH CHILDREN

Word count: 17.234

Annelien Everaert

Student number: 01605404Supervisor: Prof. Dr. June Eyckmans

A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Multilingual Communication Dutch-English-French

Verklaring i.v.m. auteursrecht

De auteur en de promotor(en) geven de toelating deze studie als geheel voor consultatie beschikbaar te stellen voor persoonlijk gebruik. Elk ander gebruik valt onder de beperkingen van het auteursrecht, in het bijzonder met betrekking tot de verplichting de bron uitdrukkelijk te vermelden bij het aanhalen van gegevens uit deze studie.

Preambule Covid-19

Het schrijven van deze masterproef werd niet gehinderd door het coronavirus. Alle data werden verzameld in november en december 2019 en er werden geen aanpassingen gedaan aan het geplande verloop van deze masterproef. Deze preambule werd in overleg tussen de student en de promotor opgesteld en door beide goedgekeurd.

Acknowledgements

This study was quite a challenge that I would not have been able to accomplish without the support and help of a few important people to whom I am incredibly grateful.

First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor Prof. Dr. June Eyckmans of the Department of Translation, Interpreting and Communication at Ghent University. I could contact her with all my inquiries and she was always ready to give me valuable advice if I needed it. She guided me through this process and thanks to her feedback, this master’s dissertation turned into a well-structured whole.

I would also like to express my gratitude to the children of the age groups ‘Kabouters’ and ‘Welpen’ of Scouts and Gidsen Berlaar for their enthusiastic cooperation during the test and the focus group discussions. I would also like to thank the scouts leaders of these groups and the parents of the participating children for their permission to let me collect my data with their children.

Last but not least, I would like to thank my parents for their unconditional support and encouragement. They pushed me to persevere and not to give up when the process was going slow.

Table of contents

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES ... 1

A. Tables ... 1

B. Figures ... 1

C. Fragments ... 1

1 INTRODUCTION ... 4

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND ... 7

2.1 English as a global language ... 7

2.1.1 English as a foreign language in Europe ... 7

2.1.2 English as a foreign language in Belgium ... 8

2.1.2.1 Formal instruction of English in Flanders ... 8

2.2 Second language acquisition ... 9

2.2.1 Incidental language learning ... 10

2.2.1.1 Incidental vocabulary acquisition... 10

2.3 Activities influencing incidental language acquisition ... 11

2.3.1 Watching TV with subtitles in the mother tongue ... 12

2.3.2 Listening to music ... 13

2.3.3 Reading ... 14

2.3.4 Gaming ... 14

2.3.5 Using the Internet, YouTube and social media ... 15

2.3.6 Speaking ... 16

2.4 Individual characteristics influencing incidental language acquisition ... 17

2.4.1 Age ... 17

2.4.2 Gender ... 18

2.4.3 Attitude towards the foreign language ... 19

3 RESEARCH ... 20

3.1 Research questions and hypotheses ... 20

3.2 Methodology ... 21

3.2.1 Participants ... 21

3.2.2 Instruments ... 22

3.2.2.1 Questionnaire ... 23

3.2.2.2 Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test ... 24

3.2.2.3 Focus group discussions ... 25

4 RESULTS ... 28

4.1 Quantitative analysis ... 28

4.1.2 Relationship between PPVT results and language input activities ... 29

4.1.3 Relationship between PPVT results and individual characteristics ... 31

4.1.3.1 Age ... 31

4.1.3.2 Gender... 32

4.1.3.3 Attitude towards English ... 33

4.1.4 Situations in which the participants speak English ... 34

4.1.5 Comparison with previous study on spontaneous English language use by Flemish 10-12-year-olds ... 36

4.2 Qualitative analysis: focus group discussions ... 38

4.2.1 Speaking English... 38

4.2.1.1 Speaking English while on vacation ... 38

4.2.1.2 Speaking English with parents and/or siblings ... 39

4.2.1.3 Speaking English with friends ... 41

4.2.1.4 Speaking English while talking to themselves ... 43

4.2.1.5 Speaking English while cursing ... 43

4.2.1.6 Speaking English while counting ... 44

4.2.2 Speaking English online ... 45

4.2.2.1 Speaking English while gaming ... 45

4.2.3 Engaging in language input activities in English ... 46

4.2.3.1 Listening to English music and singing ... 47

4.2.3.2 Watching TV in English ... 48

4.2.3.3 Watching online content on YouTube and/or social media ... 49

4.2.4 Reasons for speaking English ... 50

4.2.4.1 English as a fun language ... 51

4.2.4.2 Speaking English for future-oriented purposes ... 54

4.2.5 Attitude towards English ... 54

4.2.5.1 English as an easy language ... 55

4.2.5.2 English as a valuable language ... 56

4.2.6 Comparison with previous study on spontaneous English language use by Flemish 10-12-year-olds ... 57

5 DISCUSSION ... 58

6 CONCLUSION ... 622

7 LIMITATIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH ... 655

BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 677

APPENDIX ... 722

A. Questionnaire for the participants ... 722

B. Questions for the focus group discussions ... 733

D. Solution sheet PPVT-4 for the examiner ... 788 E. Transcriptions of the focus group discussions ... 80

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

A. Tables

Table 1. Questionnaire form ... 23

Table 2. Transcription conventions... 27

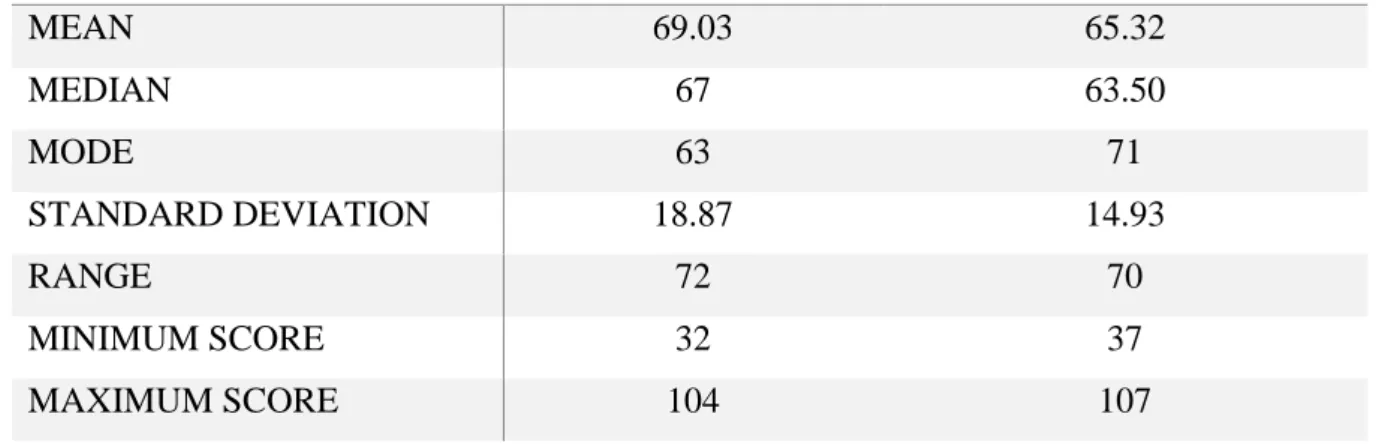

Table 3. Descriptive statistics fort he administered PPVT-4 (n=59) ... 28

Table 4. Relationship between language input activities in English and PPVT scores as measured by linear regression ... 31

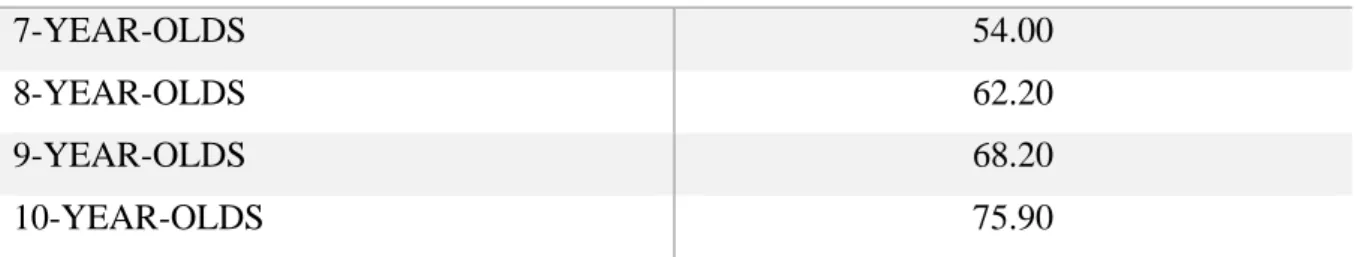

Table 5. Mean scores on PPVT-4 per age category (n=59) ... 32

Table 6. Relationship between individual variable ‘age’ and PPVT scores as measured by linear regression ... 32

Table 7. Descriptive statistics for the administered PPVT-4 according to gender ... 33

Table 8. Relationship between individual variable ‘gender’ and PPVT scores as measured by linear regression ... 33

Table 9. Mean scores PPVT-4 in relation to the participants’ attitude towards English ... 34

Table 10. Relationship between individual variable ‘attitude towards English’ and PPVT scores as measured by Independent Samples T Test ... 34

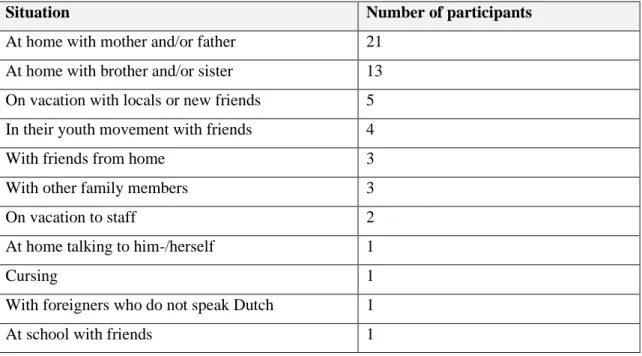

Table 11. Situations in which the participants speak English ... 35

Table 12. Comparison PPVT-4 scores with those of De Bleecker’s study ... 36

Table 13. Comparison mean scores PPVT-4 for boys and girls with those of De Bleecker’s study ... 37

B. Figures Figure 1. First slide of the PPVT-4 ... 24

Figure 2. PPVT-4 answer sheet ... 24

Figure 3. Individual results PPVT-4 ... 29

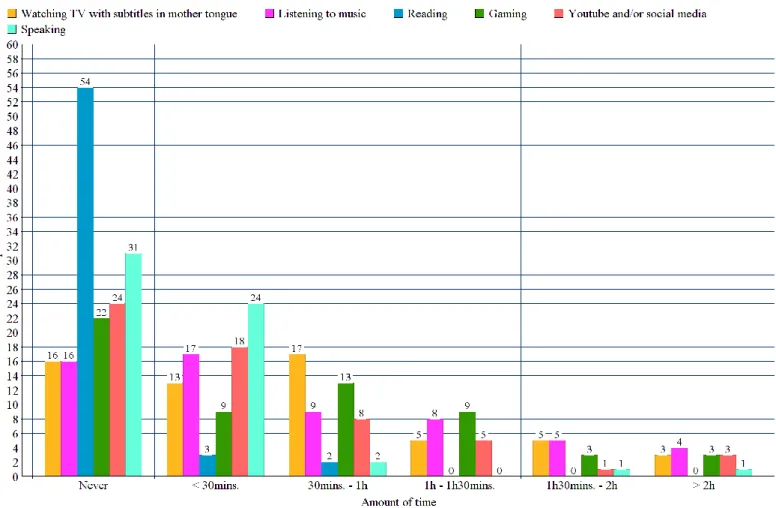

Figure 4. Daily contact with language input activities in English ... 30

Figure 5. Questionnaire section ‘Do you sometimes speak English yourself?’ ... 35

C. Fragments Fragment 1. Speaking English while on vacation (A) ... 39

Fragment 2. Speaking English while on vacation (B) ... 39

Fragment 4. Reasons for speaking English with parents (A) ... 40

Fragment 5. Reasons for speaking English with parents (B) ... 40

Fragment 6. Speaking English with siblings (A) ... 40

Fragment 7. Speaking English with siblings (B) ... 41

Fragment 8. Speaking English with siblings (C) ... 41

Fragment 9. Speaking English with friends (at scouting activities) (A) ... 41

Fragment 10. Speaking English with friends (at scouting activities) (B) ... 42

Fragment 11. Speaking English with friends (at school) (A) ... 42

Fragment 12. Speaking English with friends (at school) (B)... 42

Fragment 13. Speaking English while talking to themselves (A) ... 43

Fragment 14. Speaking English while talking to themselves (B) ... 43

Fragment 15. Speaking English while cursing ... 44

Fragment 16. Speaking English while counting (A) ... 44

Fragment 17. Speaking English while counting (B) ... 45

Fragment 18. Speaking English while gaming (A) ... 46

Fragment 19. Speaking English while gaming (B) ... 46

Fragment 20. Speaking English related to gaming ... 46

Fragment 21. Listening to English music (A) ... 47

Fragment 22. Listening to English music (B) ... 47

Fragment 23. Listening to English music (C) ... 48

Fragment 24. Watching TV in English (A) ... 48

Fragment 25. Watching TV in English (B) ... 49

Fragment 26. Watching TV in English (C) ... 49

Fragment 27. Watching online content on TikTok ... 50

Fragment 28. Watching online content on YouTube ... 50

Fragment 29. Reasons for speaking English (A) ... 51

Fragment 30. Reasons for speaking English (B) ... 51

Fragment 31. English as a fun language (A)... 52

Fragment 32. English as a fun language (B) ... 52

Fragment 33. English as a fun language (C) ... 53

Fragment 34. English as a fun language (D)... 53

Fragment 35. English as a fun language (E) ... 53

Fragment 36. English as a fun language (F) ... 53

Fragment 38. Speaking English for future-oriented purposes (B) ... 54

Fragment 39. Attitude towards English (A) ... 54

Fragment 40. Attitude towards English (B) ... 55

Fragment 41. Attitude towards English (C) ... 55

Fragment 42. English as an easy language (A) ... 55

Fragment 43. English as an easy language (B) ... 56

Fragment 44. English as a valuable language (A) ... 56

1 INTRODUCTION

The use of English has become omnipresent, not only in Belgium’s everyday society, but in that of many countries all over the world. Films, TV shows, songs, commercials, etc. create a daily contact with English. The globalisation of the economy intensifies the importance of English, as it is seen as a lingua franca, a “common language” (Crystal, 2003, p. 11) to simplify the communication between different international institutions and companies.

The ever-present availability of the Internet in today’s society contributes to an increasing contact with the English language as well. The online world is accessible for everyone and social media channels facilitate the dissemination of English. Since children receive a mobile phone, tablet or other game console at an increasingly younger age, they are able to spend a significant amount of time online. Through gaming, scrolling on their social media platforms or watching videos on YouTube or other popular channels such as TikTok, they pick up a substantial amount of words and phrases in English. Various researchers such as De Wilde & Eyckmans (2017), Kuppens (2007) and Willems (2016) have demonstrated that the media usage of young Flemish children has a positive influence on foreign language learning, and more particularly on their lexical acquisition of English.

Previous research (De Wilde & Eyckmans, 2017) has revealed that young Flemish children usually show a positive attitude towards the English language and that this might be a reason for them to also productively use English in their daily life. This study will further analyse in which situations they have a tendency to speak English themselves and why they sometimes prefer the use of English instead of their mother tongue.

In this master’s dissertation the lexical knowledge in English of children aged 7 to 10 years old will be examined. The aim of this research is to map out the participants’ daily exposure to English as well as their own use of the foreign language. Their attitude towards the English language will be taken into account, as well as other variables such as age and gender to analyse if those variables have an influence on the incidental vocabulary size of the children. The innovative aspect of this study is the age of the participants. Previous research (Boone, 2018; De Bleecker, 2019; Degrieck, 2018; De Wilde & Eyckmans, 2017; Van Hoecke, 2017) on incidental language learning in young Flemish children mainly focussed on children from the last two years of primary school who are between 10 and 12 years old. This study, on the other

hand, will analyse the use of English in younger Flemish children who are in the third to fifth grade of primary school and are thus between 7 and 10 years old.

Following De Bleecker’s (2019) example, this study will investigate the receptive vocabulary size in English of young Flemish children before they have received any form of formal instruction in English. To measure the participants’ receptive vocabulary size, they will be administered the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (Dunn & Dunn, 2013). Furthermore, the children’s daily activities in English will be examined in order to create an overview of their extracurricular exposure to English. The aim is to determine whether these activities have a positive impact on the participants' incidental language learning in English.

The major difference between this research and De Bleecker’s (2019) study is the age of the participants. De Bleecker’s results of 10 to 12 year-old Flemish pupils will be compared with the results of 7 to 10-year-olds in order to examine if the difference in age has an effect on the PPVT scores. A difference in scores might be due to a difference in daily exposure to English since older children have been longer exposed to English than younger children. On top of that, it is interesting to examine whether younger children use English in different situations and for the same reasons as older children. Moreover, the attitude towards the English language of the participants in both studies will be compared to analyse the possible differences.

This master’s dissertation commences with a theoretical overview of relevant studies to this research in chapter 2. The focus lies on second language acquisition, and more specifically on incidental language learning and the extracurricular activities that may influence this process such as gaming, using the internet, listening to music, etc. Furthermore, this section will discuss the impact of individual characteristics such as age, gender and attitude towards the foreign language on the process of incidental language learning.

Chapter 3 and 4 elaborate on the study itself. Firstly, the research questions and hypotheses are described in chapter 3, followed by the methodology including information details on the participants and instruments. Three different methods of data collection were used: the PPVT, a questionnaire and seven focus group discussions. Chapter 4 displays the results of this research, consisting of a quantitative analysis of the PPVT scores in correlation to the extracurricular activities and individual characteristics, and of a qualitative analysis that discusses the results of the focus group discussions, giving a clearer image on the children’s

motivation to speak English and the situations in which they use it. The results of the qualitative analysis constitute the primary focus of this research.

Subsequently, chapter 5 presents an interpretation of the results. Chapter 6 provides a final conclusion where the main findings of the research are summed up. Lastly, chapter 7 enumerates the limitations of this study and suggests possible directions or approaches for further research.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

2.1 English as a global language

According to Crystal (2003) a language acquires a genuinely global status when it is assigned a special role that is acknowledged in every country. In order to achieve such a status, the language must be adopted by different countries all over the world. Crystal (2003) argues that the spread of English is due to Britain’s political imperialism and its role as world leader in terms of industrial revolution and trading during the nineteenth century. Followed by the rise of North America as a global economic superpower during the twentieth century, the dissemination of the English language was preserved.

In the 1950s, the demand for a common language between different parties with another linguistic background strongly emerged when the first international organisations such as the United Nations and the World Bank were created. It had never happened before that so many countries came together to discuss certain matters. Consequently, a common language was essential in order to facilitate communication between the different countries and to avoid high translation and/or interpretation costs (Crystal, 2003). Such common language is also often called a lingua franca and at present, the concept ‘English as a lingua franca’ (ELF) refers to the communication in English between speakers with a different mother tongue (Seidlhofer, 2005).

The dissemination of English endured, because in today’s globalised society, the English language still holds an important role. Especially in international business transactions and relationships, English is generally adopted as the lingua franca. In addition, English holds an important position in education, as it is the most widely taught foreign language in the world (Crystal, 2003).

2.1.1 English as a foreign language in Europe

In the European context as well, speakers with different linguistic backgrounds most often use English to interact and communicate with each other. A study from the European Commission (2006) has shown that 38% of EU citizens indicate that they are sufficiently proficient in

English to hold a conversation. The study also considered the respondents’ self-rated language skills in the five most widely spoken foreign languages including English, German, Spanish, Russian and French. The results show that the participants rate their English language skills to be the best in comparison to the other four languages and 69% indicated to speak English well or very well. According to Berns, De Bot & Hasebrink (2007) Europeans also regard English as the most useful language to master in addition to their mother tongue.

2.1.2 English as a foreign language in Belgium

Even though English is not one of Belgium’s official languages, it still has developed a significant status in the country’s civilisation and certainly in situations with people from different linguistic backgrounds, such as the communication between employees of multinational companies. Belgium has three official languages: Dutch, French and German, but this does not mean that Belgians master these three languages. Most Belgians are not even capable of speaking two of the three languages fluently. In fact, the EU Commission study (2006, p.13) revealed that of the languages Belgians speak well enough in order to be able to have a conversation, excluding their mother tongue, 59% indicated English, compared to only 48% for French and 27% for German.

2.1.2.1 Formal instruction of English in Flanders

In comparison to other European countries, Flemish pupils start learning foreign languages relatively late. The average European pupil is already taught foreign languages at the beginning of primary school (Declercq, Denies & Janssen, 2012). In Flanders, pupils only learn a foreign language from the fifth grade of primary school onwards, when they are approximately 10 years old. The first foreign language to be taught is French. English is taught as a second foreign language starting from the first or second grade of secondary school, when the children are 12-13 years old (Denies, Heyvaert & Janssen, 2015).

The Flemish report of the European Survey on Language Competences (Declercq et al., 2012), revealed that Flemish pupils achieve the best results for their second language compared to the results of other countries for their second language. It is important to note that in the vast

majority of countries English is taught as the first foreign language, whereas for Flanders it is only the second foreign language taught.

Although Flemish pupils are firstly taught French and receive formal instruction in English only two or three years later, they indicate that this is the opposite order in which the languages are present in their daily environment. Even though French is the first foreign language taught in Flanders, young people come into contact with English much more often outside school than French because they listen to English music, watch English TV shows or films, and spend time online browsing English websites or social media channels (Declercq et al., 2012).

2.2 Second language acquisition

Second language acquisition (SLA) refers to the process of learning a non-native language after the mother tongue has been learned. Although the term second language acquisition sometimes includes learning a third, fourth or fifth language, it is used as a comprehensive term for learning any language after the native language. The second language is usually mentioned as the L2, whereas the mother tongue is referred to as the L1 (Ellis, 2015; Gass, Behney, & Plonsky, 2013). Ellis (2015) adds that L2 acquisition is influenced by the mother tongue, since it occurs after L1 acquisition.

A distinction is commonly made between second and foreign language acquisition due to different learning contexts. Second language acquisition refers to the learning of a non-native language in an environment where that language is part of everyday society, for example, emigrated Belgians learning English in the United Kingdom. Learners are immersed in the language and they are faced with situations in which they have to communicate with native speakers. It is assumed that learners will pick up part of the language through the daily encounters they experience (Ellis, 2015; Gass et al., 2013).

Foreign language acquisition, on the other hand, refers to the learning of a foreign language in the environment of one’s mother tongue, for example, Dutch speakers learning English in Flanders. Foreign language acquisition usually takes place in the context of a classroom where the second language is taught without many opportunities to use the language in everyday life (Ellis, 2015; Gass et al., 2013). Ellis (2015) adds that although the distinction between second

and foreign language acquisition is generally made, second language acquisition is often still used to refer to the process of acquiring a second language in both contexts.

2.2.1 Incidental language learning

As mentioned before (cfr. 2.1.1.2), Flemish children often come into contact with English outside a school setting through listening to music, watching TV shows or films in English, watching online content in English on websites or social media channels, etc. As a result of the children’s frequent engagement in these activities, they pick up a significant amount of English words before they have even received formal instruction of English. Even though the children learn new words, they had never the intention to learn. This process is called incidental language learning and refers to “the acquisition of a word or expression without the conscious intention to commit the element to memory, such as “picking up” an unknown word from listening to someone or from reading a text” (Hulstijn, 2013, para. 1).

In opposition to incidental language learning, intentional learning refers to the learner making deliberate attempts to memorise certain information. This process often involves repetition techniques, such as when one is studying for a test or wants to learn a song by heart (Hulstijn, 2013).

2.2.1.1 Incidental vocabulary acquisition

Hulstijn (2001) states that in literature on L1 and L2 vocabulary acquisition, it is generally believed that learners acquire most vocabulary items incidentally, “as a by-product of the learner being engaged in a listening, reading, speaking or writing activity” (p. 266) and that only a small amount of words are acquired intentionally as a result of explicit learning techniques in order to memorise vocabulary items.

Restrepo Ramos (2015) stresses the importance of vocabulary in the incidental learning process and depicts vocabulary as “the building blocks from which learners start their second language (L2) acquisition” (p. 158). He adds that although vocabulary is an important aspect of incidental language learning, researchers still do not fully understand how incidental vocabulary acquisition occurs, as several factors play a role in the success of the learner trying to infer the

meaning of a word, such as the exposure amount, wordguessing strategies, and the context quality facilitating the learner’s lexical inference activities.

According to Webb & Chang (2015), incidental vocabulary learning is a gradual process in which knowledge is acquired through repeated encounters in a particular context. They state that the process typically starts with learning the form of a word in the first few encounters, and that as the repetitions increase, the connection form-meaning and collocations are acquired as well.

Laufer (1998) agrees with this statement as she explains that lexical knowledge is not an “all-or-nothing phenomenon” (p. 256), but that it consists of different levels of knowledge. She distinguishes between passive (receptive) knowledge, implying that one understands the most common and core meaning of a word, and two forms of productive knowledge: controlled and free. The first type of productive knowledge means that one can produce words when requested in a task, while free productive knowledge refers to the voluntary use of words, without being prompted to do so. Additionally, Laufer indicates that when learning a word, the level of knowledge usually advances from receptive to productive knowledge.

2.3 Activities influencing incidental language acquisition

The position of the English language in Belgium is becoming increasingly important. English is ubiquitous in today's media landscape and as a result, young children come into contact with the language early on, even before they are taught English at school (De Wilde & Eyckmans, 2017). Previous research has shown that media exposure has a strong effect on language acquisition and that this English media input enables children to process the information they see and to adopt a significant amount of words and/or phrases (De Wilde & Eyckmans, 2017; Kuppens, 2010; Lekkai, 2014; Sundqvist, 2009; etc.).

The children’s media exposure is largely due to the technological devices that they have at their disposal from an early age onwards. A recent study by Mediaraven, Mediawijs & imec-MICT (2018) on media ownership and media use among Flemish children aged 6 to 12 years old has revealed that 67% of the surveyed children use a tablet regularly and that 56% of the 9 to 12-year-olds possess their own tablet. Other popular devices for the children’s media use are the

television (61%), the computer (57%) and the smartphone (49%). The study also showed that the older the children, the higher the percentage that possesses their own mobile phone or smartphone. However, 1 out of 5 children under the age of 8 already owns their personal device.

The participants in this study were asked to indicate how much time they spent participating in the six following language input activities on a daily basis: watching TV in English with subtitles in the mother tongue, listening to English music, reading in English, gaming in English, using YouTube and/or social media in English and speaking English. In the following paragraphs, the impact of these activities on incidental language acquisition will be discussed.

2.3.1 Watching TV with subtitles in the mother tongue

The TV has become the perfect medium to obtain information from all over the world due to the vast range of different channels and has also become a popular means for children to acquire new knowledge (Lekkai, 2014). Furthermore, the media aimed at young people largely consists of English television programs, films and music (Kuppens, 2010). This is especially true in small European countries such as Belgium and the Netherlands where large numbers of foreign language programs are imported and which are generally subtitled. This is in contrast to large European countries where these programs are usually dubbed (Koolstra & Beentjes, 1999).

Previous research has demonstrated that watching television with subtitles has a beneficial effect on incidental foreign language acquisition (d’Ywalle & Van de Poel, 1999; Lekkai, 2014; Kuppens, 2010). According to Rodgers (2013), the process of incidental vocabulary learning can also be stimulated by the nature of the programs. Many programs or TV shows consist of several episodes which allows viewers to watch television on a regular basis. Webb & Rodgers (2009) also state that “increased viewing would increase the likelihood of incidental learning” (p. 341). Kuppens (2007) confirms this statement because her research revealed that children who watched subtitled English TV programs on a daily basis possessed a larger active vocabulary knowledge than children who did not. She also adds that this observation confirms the long-term effect of watching TV on language proficiency.

When watching subtitled television one can hear the original language of the program or film while the subtitles in the target language are visible at the bottom of the screen (Lekkai, 2014). According to Koolstra & Beentjes (1999), vocabulary is learned from natural language by

trying to understand what is being said, sung or written on the television screen, and not because the viewer actually wants to learn the words. The viewer must deduce the meaning of the word from the context. Koolstra & Beentjes consider this learning method to be a step-by-step process in which the learner tries to understand the meaning of the word by using the syntactic and semantic hints provided by the context.

2.3.2 Listening to music

Music is another popular medium through which young people are exposed to English to a large extent. As De Wilde & Eyckmans (2017) indicate, in Flanders the majority of the music played on the radio has English lyrics. Therefore, Flemish children automatically come into contact with English music, even if they do not necessarily feel the need to.

Kuppens (2010) states that a profound proficiency in English is not essential for pupils to understand a subtitled English film or TV program, to enjoy listening to English music or to play an English computer game. Maneshi (2017) also found that even learners with a very small vocabulary size could incidentally acquire words by listening to songs. According to her, songs create the perfect environment for vocabulary acquisition as a result of the repeated encounters with words that recur in different songs and the large amount of time people spend listening to music. Similarly, Schwarz (2012) considers pop music to be an optimal medium for vocabulary acquisition since foreign language input is linked with the learners’ personal interests and enjoyment. According to Kuppens (2007), English words from music can possibly be memorised more easily because one can sing along with song lyrics.

Previous research by Kuppens (2007) demonstrated that young people who listen to English music on a daily basis know more words that are unrelated to the mother tongue than young people who listen to English music less often. Furthermore, Maneshi (2017) found that listening to a song multiple times positively affects young people’s incidental vocabulary acquisition. However, it is important to keep in mind that some people also intentionally acquire vocabulary from music. A study by Schwarz (2012) conducted with Austrian 13-15-year-olds revealed that some youngsters consciously tried to understand the meaning of songs in order to improve their English skills, by looking up the song lyrics or their translation.

2.3.3 Reading

In the field of second language acquisition, reading has gained the status of being a solid asset for vocabulary acquisition that can induce incidental vocabulary learning (Ponniah, 2011). Ponniah states that by reading unknown words, at least parts of the new words’ meanings are acquired. He explains that incidental vocabulary acquisition occurs when readers concentrate on the meaning of the text and not on the unfamiliar words they encounter in the text. As a result, they do not realise that they are acquiring new words, but they subconsciously absorb their meaning. Krashen (2004) refers to this process of subconscious learning as the Comprehension Hypothesis.

However, Waring & Nation (2004) warn that when a text contains too many unfamiliar vocabulary items, second language reading turns into a study activity because the reader has to digest the text intensively and slowly rather than unconsciously. Several researchers (Kweon & Kim, 2008; Ponniah, 2011; Waring & Nation, 2004) also stress the importance of frequency in incidental learning through reading: the more readers are exposed to language input, the more vocabulary they will acquire.

Ponniah (2011) observed that learners who had incidentally acquired vocabulary through reading could use these words in sentences, whereas learners who had consciously learned words could not. Thus, the readers who did not realise that they were reading to increase their vocabulary size, did not only unconsciously absorb the meaning of the words, but also the grammar. On the other hand, Yali (2010) found that inferring the meaning of words through incidental vocabulary learning while reading does not imply that the meaning of those words will be retained by the reader in the long term. She discovered that when incidental learning through reading was not followed by certain comprehension tasks (intentional learning), the acquired vocabulary was badly memorised.

2.3.4 Gaming

Today, digital games constitute an important part of young people’s daily activities. Research by Mediaraven, Mediawijs & imec-MICT (2018) (cfr. 2.3) demonstrated that 75% of Flemish 6-12 year-olds use their technical devices such as tablets, smartphones and computers to play digital games. Many of those games are originally in English, which provides children with a

“linguistically rich and cognitively challenging virtual environment that may be conducive to L2 learning, as learners get ample opportunities for L2 input and scaffolded interaction in the L2” (Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012, p. 302).

According to Jensen (2017), it is not remarkable that gaming can have a positive impact on incidental vocabulary acquisition because normally the gamer is motivated to understand the content of the game and what is being said. That motivational factor is probably related to the fact that gamers voluntarily choose to play certain games, and that they engage in this activity purely for their personal enjoyment (Jensen, 2017; Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012). Rudis & Poštić (2018) also add that learning a foreign language while gaming is highly effective as it is very motivating for gamers that they do not feel the pressure to perform well in the foreign language, which would be the case in a school environment.

In terms of the type of games, Sylvén & Sundqvist (2012) observed a difference in gender. Girls were more likely to opt for single-player simulation games, while boys preferred first-person shooter games or multiplayer games. The latter are often considered as a valuable source for L2 acquisition as they create opportunities for gamers to interact in the foreign language. According to Rudis & Poštić (2018), teamwork-focused games provide the players with “on the spot communication” (p. 113) which is beneficial for the development of the gamers’ communication and verbal skills. Kuppens (2010) states as well that multiplayer online games can allow gamers to build global friendships using new forms of language learning to communicate with each other.

2.3.5 Using the Internet, YouTube and social media

The Internet is an inexhaustible source of information that is accessible for anyone who owns a computer or other Internet-connected device. The online world has expanded considerably in recent years and now consists of various search engines, billions of websites, social media channels, etc. A large part of the content that can be found online is written in English, and because everyone can search for information to their own liking, it is very likely that children are exposed to English while browsing various websites, watching videos on platforms such as YouTube, or while watching content on social media.

The study by Mediaraven, Mediawijs & imec-MICT (2018) (cfr. 2.3) that inquired into the media use of Flemish children aged 6-12 years old, discovered that YouTube is the most popular platform among children in this age category: 82% of them use it regularly. The success of YouTube is probably due to the fact that it fully satisfies the children’s great interest in videos and music. With regard to the children’s social media use, the study showed that the percentage of children using social media increases with age. A study by Kuppens (2010) with 374 Flemish pupils in the last year of primary education revealed that browsing the internet is an activity that is strongly connected to the English language, as 57.6% of the respondents indicated that they visit English websites at least once a week.

De Jans (2013) found in his study that surfing on the Internet appeared to have the largest influence on the children’s productive English vocabulary. He also observed that the amount of Internet exposure impacted the children’s incidental vocabulary acquisition. Children who spent more time browsing on the Internet, would also acquire more vocabulary items. In addition, De Jans discovered that children who sometimes chat online in English with foreign friends or acquaintances scored significantly better on the vocabulary test.

2.3.6 Speaking

Speaking is an essential part of learning a new language and within the field of second language acquisition, many linguists believe that students can learn to speak in the second language by interacting with others (Kayi, 2006). According to Kayi, being able to communicate in a second language is also a great advantage for the learner, as it improves the learner’s success at school, as well as in every later stage of life.

Swain (2007) discusses the output hypothesis which states that the act of producing language through speaking or writing can, under certain circumstances, contribute to second language acquisition. Ponniah & Krashen (2008) add to this hypothesis that output can indirectly enhance second language acquisition if input is also involved, and that output has a positive effect on cognitive development.

In addition, a study by Sundqvist (2009) demonstrated that students who regularly spoke English in their spare time, were more exposed to out-of-school English than others as a result

of their engagement in certain language input activities such as playing video games, surfing the Internet, etc. Furthermore, she states that speaking English regularly has a positive influence on the students’ oral proficiency. Sundqvist defines oral proficiency as “as the learner’s ability to speak and use the target language in actual communication with an interlocutor” (p. i, abstract).

2.4 Individual characteristics influencing incidental language acquisition

In the previous chapter it became clear that some language input activities can influence incidental language acquisition. However, it is important to keep in mind that there are some individual characteristics that may impact one’s vocabulary size as well. Those characteristics can be seen as a possible reason why for example, one obtains higher vocabulary gains than others. In this chapter, the characteristics age, gender and attitude towards the foreign language are discussed.

2.4.1 Age

There are significant differences in the age at which people start learning a second language. Some start learning a second language in their early childhood, while others only learn it in high school or when they are already adults. Rod Ellis (2015) devoted a chapter in his book ‘Understanding Second Language Acquisition’ to the effect of age on L2 acquisition since a considerable amount of research has already been conducted on this subject, but many different conclusions were drawn. The main findings of the chapter will be summarised here.

Firstly, the Critical Period Hypothesis will be discussed. This hypothesis was first mentioned by Penfield and Roberts in 1959 and states that there is a period (often considered to be the period until the onset of puberty) until when learners can easily and implicitly acquire a second language and until when they can reach native-speaker skills. After that period, however, the second language is more difficult to acquire and the process is often not completely successful. Even though many linguists believe in this hypothesis, there is no clear agreement as to when this critical period for second language acquisition exactly comes to an end (Ellis, 2015).

Ellis (2015) observed that regardless of the learning context, older children outperform younger children and adults and adolescents improve faster than children. This first observation corresponds to a study by Lekkai (2014) who found that older children acquired more vocabulary by watching subtitled television than younger children. Furthermore, Ellis states that initially older learners have an advantage over younger learners in terms of grammar and vocabulary because older learners benefit more from conscious learning strategies. Children, on the other hand, make more use of implicit learning strategies which eventually allows them to catch up and surpass the older learners.

2.4.2 Gender

From previous research, it is often concluded that girls generally perform better in languages than boys at school. According to Sundqvist (2009), this conclusion can be linked to the neuroscience that uncovered the differences between the brains of boys and girls. It showed that most women's brains evolve faster than men's brains, meaning that girls mature at an earlier age than boys.

A large study by van der Silk, van Hout & Schepens (2015) that looked into the effect of gender on second language acquisition, which was based on data from more than 25 000 immigrant adult learners with Dutch as their L2, showed significant differences in proficiency between sexes. The results of the study demonstrated that in terms of speaking and writing skills, women scored better than men, regardless of their country of origin and mother tongue. The difference in proficiency also remained visible after taking into account individual characteristics such as education, age of arrival, length of stay, etc. Regarding listening skills, no gender differences were measured, but for reading skills the differences were in favour of the male learners: they significantly outperformed the female learners on the reading test.

However, it is important to remember that the aforementioned study was conducted with adult participants. In this study, young children from 7 to 10 years old are observed and as mentioned above, other individual characteristics such as age can play a role as well in the children’s second language proficiency.

2.4.3 Attitude towards the foreign language

Attitudinal factors play a crucial role in second or foreign language acquisition and they are believed to influence the learner’s success and achievement in the new language. The factors stimulate the learner to initiate the productive learning process and serve as a source of perseverance during the tiresome process of mastering a second or foreign language (Mustafa et al., 2015). In this part, language attitude and motivation are discussed. Language attitude is understood as the learner’s negative or positive feelings towards a language whereas motivation consists of the combination of the desire to learn the language and the positive attitude towards the learning process, as well as the effort the learner is willing to put into the process (Mihaljevic Djigunovic, 2012).

Mertens (2016) investigated the attitude and perception of English among Flemish primary school children. Children of the first, third and fifth grade watched two versions of the same video fragment with a superhero as the main character. The first time he had a Dutch name and spoke Flemish, the children’s mother tongue, and the second time he had an English name and used a number of English words throughout the fragment. Afterwards, the children were asked which of the two superheroes they liked the most. The results show that Flemish primary school children generally have a positive attitude towards the English language. The English superhero was most popular in the third grade with a preference of 71.43%. In the first and fifth grade the percentages were considerably lower with 57.14% in the first grade compared to 58.82% in the fifth grade.

Attitude towards a language and the motivation to learn a language are often closely intertwined. In the study by Mustafa et al. (2015) all the students had a positive attitude towards the English language and they were highly motivated to improve their English. They believed that mastering the English language would be beneficial for their future as it would make them better educated and it would help them to get a better job. The researchers also found that the more positive the attitude towards English, the greater their motivation to learn the language. Alsayed (2003) observed that motivation correlated strongly with the students’ language proficiency and that it was a very important factor that could predict their overall performance in English.

3 RESEARCH

This master’s thesis contributes to the research cluster ‘Language Learning’ of MULTIPLES (Research Centre for Multilingual Practices and Language Learning in Society) from Ghent University, and is situated within the field of Second Language Vocabulary Acquisition.

3.1 Research questions and hypotheses

This study consists of three main objectives. The first objective is to determine the English receptive vocabulary size of Flemish children aged 7-10 years old from the third to the fifth grade of primary school. The second objective is to examine why and in which contexts these children use English, before they have received any form of formal instruction in English. Lastly, the data will be compared with De Bleecker’s (2019) results, who carried out a similar study with children aged 10-12 years old. The quantitative analyses of both studies will be compared to identify potential differences or similarities in the participants’ PPVT scores in relation to English language input activities and individual characteristics. On top of that, the qualitative analyses of both studies will be compared to examine the differences or similarities in the outcome of the focus group discussions that were carried out to investigate the situations in which the participants speak English, their reasons for speaking English and their attitude towards the language.

In order to reach these objectives, this study will try to provide an answer to the following research questions:

1. What is the English receptive vocabulary size of Flemish children aged 7-10 years old from the third to the fifth grade of primary school before they have received formal instruction in English?

2. Do these children sometimes use English productively? And if so, why do they use English and in which contexts?

3. Are there differences or similarities in the participants’ English receptive vocabulary size and their reasons for speaking English in certain contexts compared with the data De Bleecker (2019) has collected in her study on the same topic with children aged 10-12 years old?

Two hypotheses were formed as a starting point to this research. Firstly, it is strongly assumed that the children will sometimes use English productively since previous research (i.e. De Bleecker, 2019; De Wilde & Eyckmans, 2017) has demonstrated that children from the age of 10 to 12 speak English sometimes. Since children from 7 to 10 years old are exposed to English on an almost daily basis, it is believed that they will use English as well in certain situations. Secondly, it is estimated that the PPVT scores of the younger children will be lower than those of the older children since younger children have not been exposed to English as long as the older children. On top of that, they are less likely to possess their own technical devices such as tablets and smartphones which limits their exposure to English more. Lekkai (2014) also discovered that among children who watch television with subtitles, the older children learn more words and have a larger language acquisition than the younger children.

3.2 Methodology

This chapter will provide more background information about the participants and the instruments used to carry out the study.

3.2.1 Participants

Since previous research (Boone, 2018; De Bleecker, 2019; Degrieck, 2018; De Wilde & Eyckmans, 2017; Van Hoecke, 2017) on incidental language learning in English in young Flemish children has mostly focussed on children from the last two years of primary school, this study will focus on younger Flemish children who are in the third to fifth grade of primary school.

For this study, data were collected from 61 Flemish children of whom 29 were girls and 32 were boys. The children did not participate in the study during school hours, but on Sundays during the activities of their youth movement Scouts en Gidsen Berlaar. The children constituted the age groups Kabouters (girls) and Welpen (boys). They were all in the third to fifth grade of primary school and they were between 7 and 10 years old. The data collection took place in November and December 2019.

Considering that the data collection took place at the youth movement of the children, they participated in the PPVT test, the questionnaire and the focus group discussions in a much more informal environment than if the data collection would have been conducted in a classroom.

The children’s parents were contacted in advance and informed about the study and the date when the data would be collected. All the boys participated in the study on the same day. The data collection for the girls happened on two different Sundays since the first day was during a holiday and only 14 girls were present. To even out the number of boys and girls, another 15 girls were tested on a second Sunday a few weeks later. For the focus group discussions, the boys were divided into two groups of 11 children and one group of 9 children, and the girls were divided into three groups of 7 children and one group of 8 children.

During the analysis of the PPVT and the questionnaire, the data of one boy and one girl had to be discarded since they did not properly fill in the test and the questionnaire form. Subsequently, the data of 59 participants (28 girls and 31 boys) were included in the quantitative analysis.

None of the children indicated that they were bilingual in English. One girl mentioned that she sometimes spoke English with her Danish stepfather but since she was not raised bilingually with English as her second language, she was still included in the study.

3.2.2 Instruments

Three different instruments were used in order to measure the children’s receptive vocabulary size, their extracurricular exposure to English, and their productive use of the English language. The data was collected in three following steps.

Firstly, the children filled in a questionnaire enquiring about their language situation at home, their daily contact with English in the form of six specific activities, their attitude towards English and their own use of English. Secondly, the children’s English receptive vocabulary size was tested through the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test. Thirdly, the children were divided into smaller groups of approximately 10 children and participated in focus group discussions in which they reported on their English language use and their reasons for doing so.

3.2.2.1 Questionnaire

As mentioned above, the questionnaire outlined the language situation in the children's homes, their daily exposure to English, their attitude towards English, and the situations in which they use English themselves. The same questionnaire was used as the one De Bleecker (2019) applied in her study, and which was based on a questionnaire from De Wilde, De Meyer & O’Neill (2016) who used a longer version for a large-scale investigation into early acquisition of English in Flanders.

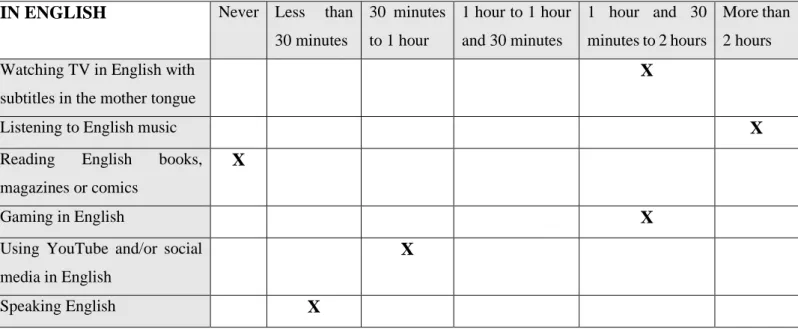

The first question the children had to answer enquired about the languages they spoke at home, with their parents and brothers and/or sisters, but also about the languages they used when talking to friends. Subsequently, the participants had to fill in a table in order to be able to estimate their daily contact with English. Six activities were listed and the children had to indicate for each activity how much time they spent on that particular activity per day. The six activities that were listed were watching TV in English with subtitles in the mother tongue, listening to English music, reading English books/magazines/comics, gaming in English, using YouTube and/or social media in English and finally speaking English themselves. The participants could choose between a time span per activity going from ‘no time at all’ to ‘more than two hours’, increasing by half an hour per column, as is visible in the following table:

IN ENGLISH Never Less than

30 minutes 30 minutes to 1 hour 1 hour to 1 hour and 30 minutes 1 hour and 30 minutes to 2 hours More than 2 hours Watching TV in English with

subtitles in the mother tongue

X

Listening to English music X

Reading English books,

magazines or comics

X

Gaming in English X

Using YouTube and/or social media in English

X

Speaking English X

Table 1. Questionnaire form

Subsequently, the children had to answer whether they like the English language or not. In the last part of the questionnaire they were asked whether they sometimes spoke English and with

whom. They had to answer this question for four specific contexts: on holiday, at home, at a sports club or youth movement or in another situation. In chapter 4, the results of the questionnaire are presented and discussed.

3.2.2.2 Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test

The fourth edition of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT-4) was used to measure the participants’ receptive vocabulary knowledge in English. The test was developed for the first time in 1959 and was revised for the fourth time in 2007 by L.M. Dunn and D.M. Dunn (2013).

The PPVT is a tool designed to assess the receptive vocabulary performance of English-speaking adults and children from 2 years and six months old to 90 years or older (Community-University Partnership for the Study of Children, Youth, and Families, 2011). Per age category, participants have to identify a different amount of words which constitute vocabulary items that they should be able to recognise at that particular age. For this study, participants had to identify 120 English words.

The PPVT was presented by means of a PowerPoint presentation that displayed four illustrations per slide. Each slide was accompanied by an English vocabulary item that had been recorded and then the participants had to indicate which image belonged to the word that they had heard. The children received an answer sheet where they had to fill in the results for the 120 vocabulary items. Per item, numbers 1 to 4 were listed, representing the four illustrations per slide. An example is presented and explained below.

Figure 1. First slide of the PPVT-4 Figure 2. PPVT-4 answer sheet

Slide number 1

Recording word ‘ball’ Correct image

Slide number 1 Correct answer: ‘ball’ = image 3

Each time the participants heard the recorded voice pronouncing a vocabulary item, they had to circle the number on their answer sheet that they thought corresponded with the word they heard. In this example, the children heard the word ‘ball’ and thus they had to circle number 3 on the answer sheet as that image represents a ball.

Before starting the actual test, the participants first heard two vocabulary items in their mother tongue Dutch to practice the test procedure and to make sure that they all understood what was expected of them. The participants were asked to leave a blank space if they did not know the correct answer. They were told that they were allowed to guess if in doubt between two items but it was emphasized that wild guesses were not allowed. When the children decided to skip an item, they were encouraged to cross out the number of the item row in order to prevent them from indicating their next answer in the wrong row. However, these directives did not prevent certain children from sometimes filling in the answer in the wrong spot. In order to avoid these mistakes from happening, the researcher started to announce the number of each slide so that the participants could follow the sequence more easily.

The test’s duration took between 45 minutes and an hour each time. The children could earn 120 points in total, with one point for each correct item. The participants did not receive points if they skipped an item or if they circled the wrong answer. The PPVT scores are discussed in chapter 4.

3.2.2.3 Focus group discussions

Focus group discussions were organised to gain a better insight into when the participants productively use English and whether they have specific reasons for doing so. In qualitative research, focus group discussions have shown to be a valuable method for data collection (Colucci, 2007). The prime concern of a focus group discussion is the interaction between participants including the possibility to discuss with each other or to add something to what another person has said. The researcher acts as moderator and collects all useful information while observing the participants (Ólafsson, Livingstone & Haddon, 2013).

As Gibson (2012) indicates, focus group discussions give researchers the opportunity to understand children’s perspectives on certain issues. She also adds that children may be more

at ease during a focus group conversation because it is natural for them to interact with peers, while a one-on-one conversation with an adult might be more challenging for them.

Before the focus group discussions started, some rules were discussed with the participants. For example, the children were asked not to talk to each other while someone else was telling his or her story, but to listen to each other. Side conversations that are unrelated to the larger conversation are in fact distracting for the other children and cause a loss of attention after which the researcher has to reformulate the question. On the other hand, when the side conversation is relatable to the larger conversation, the researcher and other children might miss out on information that is valuable to the discussion (Gibson, 2012). Subsequently, the children were asked to raise their hand when they wanted to say something.

In order to ensure that the conversations went smoothly, the participants were divided into small groups. The boys were divided in two groups of 11 children and one group of 9 children. The girls were divided in three groups of 7 children and one group of 8 children. The focus group discussions lasted between 5 and 10 minutes and continued until the participants had nothing left to tell about their use of English.

Another important aspect of focus group discussions is to create a friendly relationship between the interviewer and the participants in order to gain the children’s trust (Gibson, 2012). In this study, the focus group discussions took place at the participants’ youth movement and since the interviewer was an scouts leader there, most of the children had a personal connection with her. As a result, most children were at ease during the conversations and had no difficulty expressing their opinions.

Furthermore, the setting of a focus group discussion matters as well. Ólafsson et al. (2013) state that a setting where children feel that they have to provide clever and right answers (i.e. a school) should be avoided. This was certainly the case in this research since the focus group discussions where held at the children’s youth movement which is an informal and playful environment for them. The participants were asked to sit in a circle and the interviewer sat together with them as a part of the group.

Every focus group discussion was video recorded with permission of the children’s parents so that the conversations could be thoroughly analysed afterwards. That way, no important

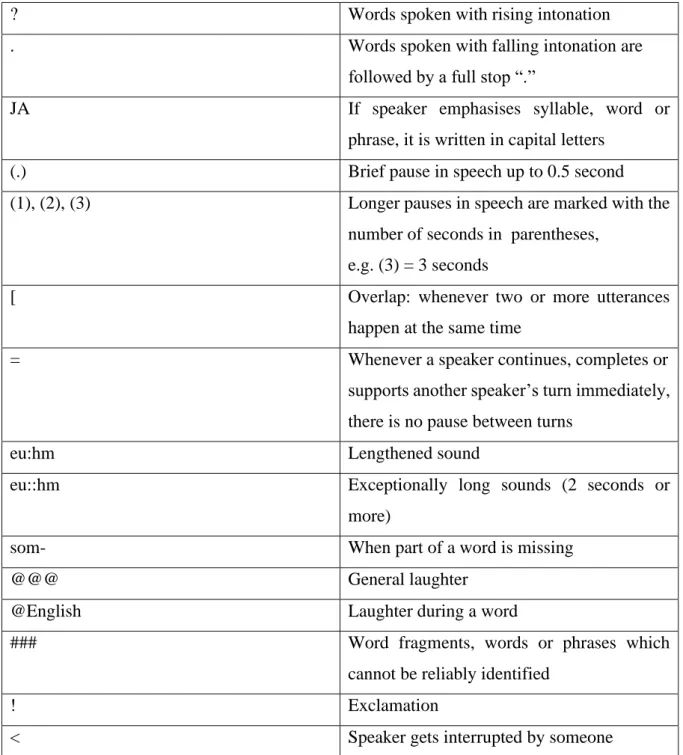

information or remarks were left out during the analysis of the discussions. On top of that, it was interesting to examine the body language of the participants to see if there were differences in their reactions towards the different questions. The focus group discussions were transcribed according to the following conventions (De Bleecker, 2019; VOICE, 2007):

? Words spoken with rising intonation

. Words spoken with falling intonation are

followed by a full stop “.”

JA If speaker emphasises syllable, word or

phrase, it is written in capital letters

(.) Brief pause in speech up to 0.5 second

(1), (2), (3) Longer pauses in speech are marked with the

number of seconds in parentheses, e.g. (3) = 3 seconds

[ Overlap: whenever two or more utterances

happen at the same time

= Whenever a speaker continues, completes or

supports another speaker’s turn immediately, there is no pause between turns

eu:hm Lengthened sound

eu::hm Exceptionally long sounds (2 seconds or

more)

som- When part of a word is missing

@@@ General laughter

@English Laughter during a word

### Word fragments, words or phrases which

cannot be reliably identified

! Exclamation

< Speaker gets interrupted by someone

4 RESULTS

This chapter will present the results of this study on the basis of a quantitative analysis which reveals the participants’ PPVT scores, and a qualitative analysis in which the focus group discussions are thoroughly examined.

4.1 Quantitative analysis

In this part, the results of the PPVT will be discussed in relation to the extracurricular activities and the individual characteristics that may have an influence on the PPVT scores. Moreover, a comparison will be made with the quantitative analysis of De Bleecker’s (2019) study to analyse potential similarities or differences in the PPVT scores, and in the participants’ daily exposure to English.

4.1.1 Scores on the PPVT

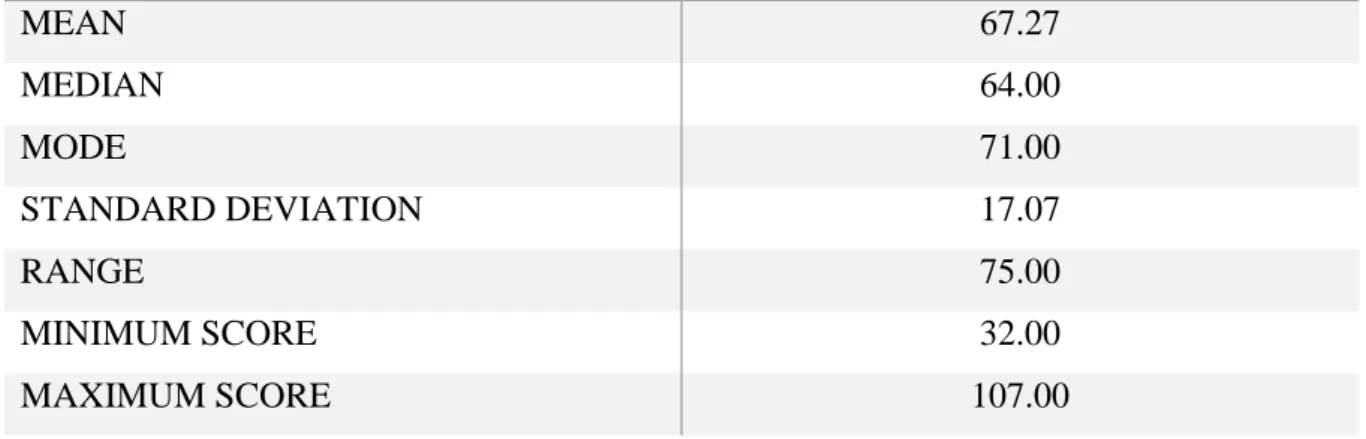

Table 3 depicts the wide range of test scores that the participants obtained for the PPVT. The participants could achieve a maximum of 120 points on the vocabulary test. The highest score amounted to 107 points and the lowest score to 32 points, which accounts for a range of 75 points. The mean score is 67.27/120, which equals 56.06%. The median reaches 64/120 and the mode 71/120. PPVT-4 (ON 120) MEAN 67.27 MEDIAN 64.00 MODE 71.00 STANDARD DEVIATION 17.07 RANGE 75.00 MINIMUM SCORE 32.00 MAXIMUM SCORE 107.00

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for the administered PPVT-4 (n=59)

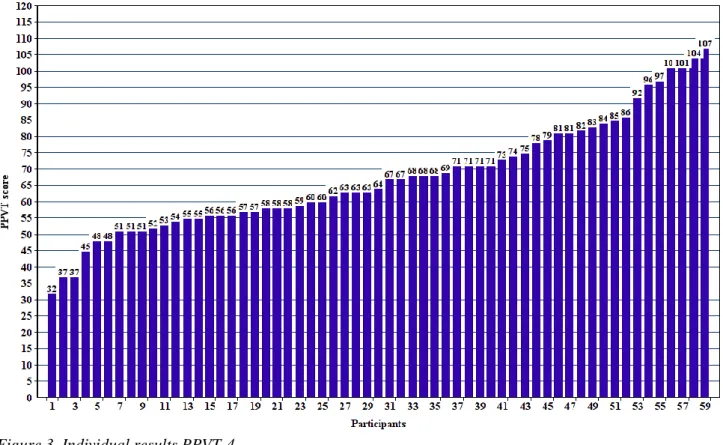

The following graph presents the participants’ individual score on the PPVT. Out of the 59 children, 23 obtained a score below 60/120. This means that 39% of the participants knew less

than half of the words of the PPVT, while a majority of 61% of the children passed the test and was able to indicate half of the items or more correctly.

Figure 3. Individual results PPVT-4

4.1.2 Relationship between PPVT results and language input activities

In this chapter, the relationship between the participants’ PPVT results and their average daily exposure to English based on six specific activities will be analysed. These activities are likely to be the cause of the children’s incidental language learning of English and include watching TV in English with subtitles in the mother tongue, listening to English music, reading in English, gaming in English, using YouTube and/or social media in English and speaking in English.

Figure 4 depicts the results of the table that the children filled in during the questionnaire and shows how many participants perform a certain activity for a certain amount of time per day. What immediately stands out, is the fact that 54 (92%) children indicate that they never read books, magazines or comics in English and that 31 children (53%), which is more than half of the participants, indicate to never speak English. The latter is in contrast to the participants’ answers during the focus group discussions which will be discussed in chapter 4.2. The amount

of time that is mostly spent on an activity lies between less than half an hour and half an hour to one hour per day. Another striking remark is that one participant indicates that he or she speaks English more than two hours a day. However, it is important to keep in mind that it might be hard for children to estimate the amount of time they spent on certain activities each day, and even harder for the youngest participants aged 7-8 years old.

Figure 4. Daily contact with language input activities in English

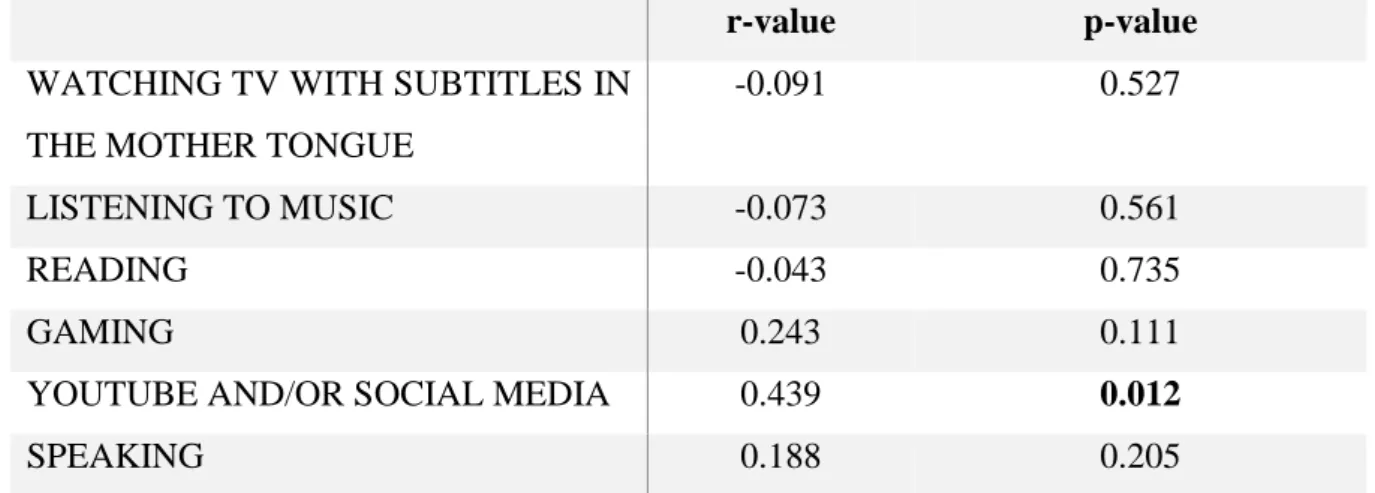

To measure the relationship between the six language input activities in English and the PPVT scores, a linear regression was run in order to examine if exposure has an effect on the participants’ incidental receptive vocabulary size. Significance was set at p < 0.05. The results of the test are presented in table 4. For five of the six language input activities, no significant relationship was found with the PPVT scores. On the other hand, the analysis showed a significant relation between ‘using YouTube and/or social media in English’ and the PPVT scores (p < 0.012). However, the correlation is rather weak (r = 0.439). Therefore, the effect of

exposure through language input activities in English on the incidental receptive vocabulary size is to be further examined, preferably with a larger number of participants.

ACTIVITIES IN ENGLISH PPVT-4

r-value p-value

WATCHING TV WITH SUBTITLES IN THE MOTHER TONGUE

-0.091 0.527

LISTENING TO MUSIC -0.073 0.561

READING -0.043 0.735

GAMING 0.243 0.111

YOUTUBE AND/OR SOCIAL MEDIA 0.439 0.012

SPEAKING 0.188 0.205

Table 4. Relationship between language input activities in English and PPVT scores as measured by linear regression

4.1.3 Relationship between PPVT results and individual characteristics

This chapter focusses on the relation between the PPVT results and the individual characteristics of the participants such as age, gender and their attitude towards the English language.

4.1.3.1 Age

To examine whether age had an influence on the PPVT scores of the participants, the mean scores were calculated for each age category. Since the data collection took place before New Year, 2 children were still 7 years old. The other age groups were better represented: 20 children were 8 years old, 25 children were 9 years old and 12 of the participants were 10 years old.

The following graph shows a significant difference between the mean scores of the various age groups. The younger the participants, the lower their PPVT scores are. The mean score for the 7-year-olds even lies below 50%. However, this mean score cannot be considered as valid since this age group was only represented by two participants. The 8-year-olds achieve a mean score just over half with 62.20 points, which amounts to 51.8%. The 9-year-olds do better with a