DETERMINANTS OF TAX AVOIDANCE:

EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE FROM BELGIAN

AND DUTCH FIRMS

Word count: 17,730

Limpens Rik

Student number : 01601236

Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Annelies Roggeman

Master’s Dissertation submitted to obtain the degree of: Master in Business Economics: Accountancy

Deze pagina is niet beschikbaar omdat ze persoonsgegevens bevat.

Universiteitsbibliotheek Gent, 2021.

This page is not available because it contains personal information.

Ghent University, Library, 2021.

P

REFACE

Writing a master’s dissertation requires determination, but gives a lot of satisfaction in return. It means the end of a major chapter and the beginning of a better one. But I would not be able to have turned this page without the help of my supervisors, friends and family. Therefore, I would like to specifically thank some people.

First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor Prof. Dr. Annelies Roggeman, for reading this master’s dissertation and giving me useful and insightful feedback. Her guidance and support helped me throughout the process of writing this thesis.

Second, I would like to express my gratitude to my family for supporting me and being proud of what I have achieved.

Finally, I would like to thank my friends for making these last four years an amazing and unforgettable period.

T

ABLE OF

C

ONTENTS

Preface ... I Table of Contents ... II List of Abbreviations ... IV List of Figures ... V List of Tables ... VI 1 Introduction ... 12 Theoretical framework and literature review ... 3

2.1 Multinational corporations in the globalized economy ... 3

2.2 Tax evasion and tax avoidance ... 4

2.3 Tax avoidance strategies ... 5

2.3.1 Double non-taxation ... 6

2.3.2 Treaty shopping ... 7

2.3.3 Minimization of taxable base in a heavily taxed jurisdiction ... 9

2.3.4 Corporate inversions ... 12

2.3.5 Transfer pricing ... 13

3 Regulatory framework ... 24

3.1 European framework ... 24

3.1.1 Base erosion and profit shifting ... 25

3.1.2 Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive ... 29

3.2 Belgian framework ... 30

3.2.1 Abnormal and benevolent advantages ... 30

3.2.2 Market price of a controlled transaction ... 32

3.2.3 Interest on loans ... 33

3.2.4 Anti-abuse provision ... 34

3.2.5 Sanctions for non-compliance behavior ... 35

3.3 Dutch framework ... 36

4 Hypotheses development ... 39

4.2 Corporate social responsibility strategy score ... 40

4.3 Environmental, social and governance controversies ... 42

4.4 Transfer pricing aggressiveness ... 42

4.5 Timing ... 43

5 Research design... 45

5.1 Sample selection and data source... 45

5.2 Dependent variable ... 46

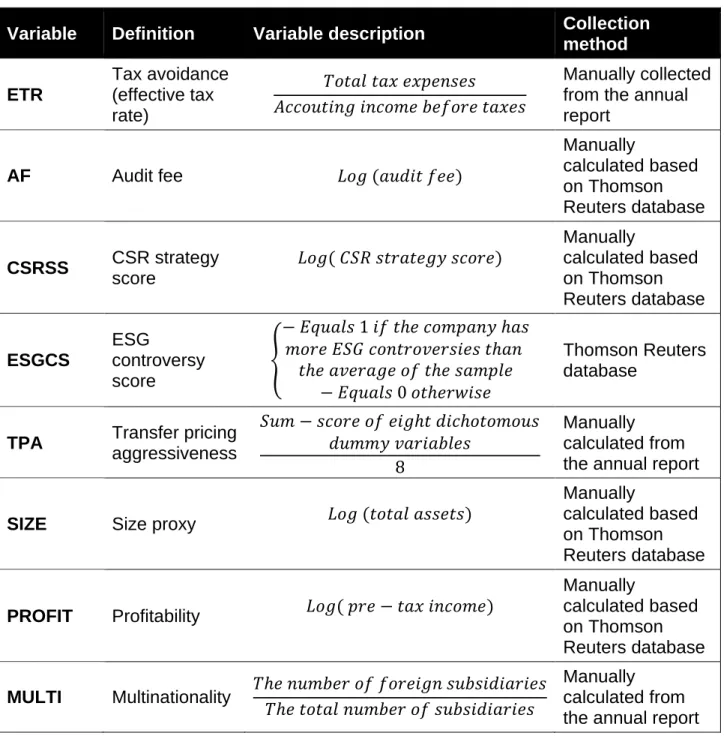

5.3 Independent variables ... 48

5.4 Control variables ... 50

5.5 Base regression model ... 52

5.6 Paired sample t-test ... 54

6 Empirical results ... 55

6.1 Descriptive results ... 55

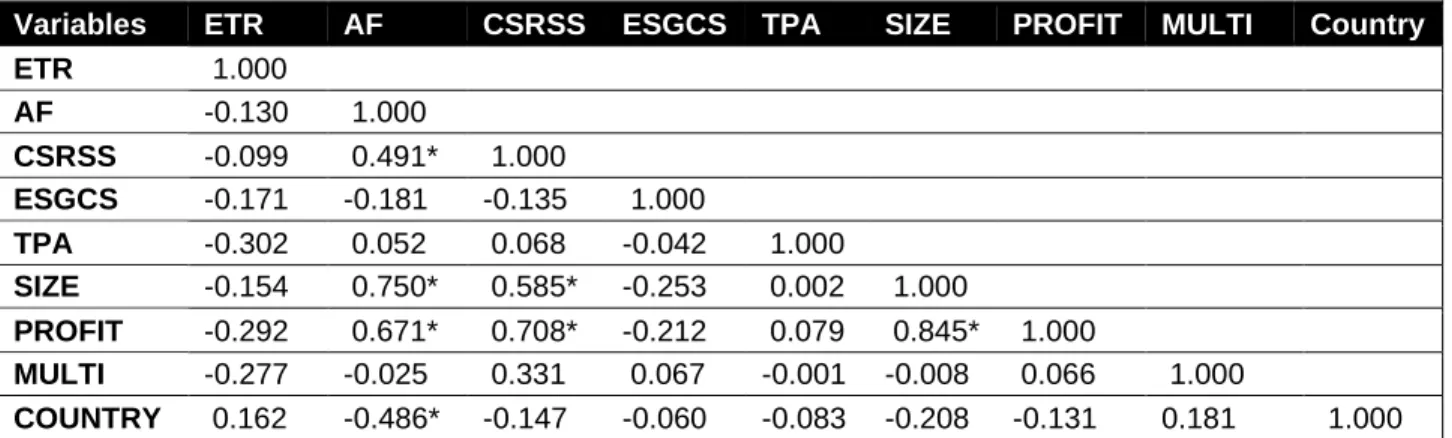

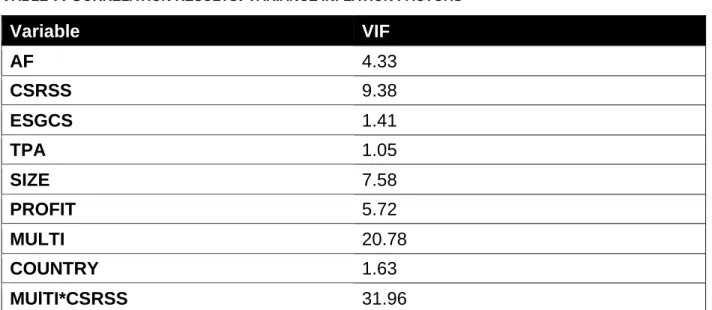

6.2 Correlation results ... 56

6.3 Regression results ... 58

6.4 Results of the paired sample t-test ... 60

7 Conclusion ... 61 References ... VII Income Tax Code ... XVIII 8 Appendices ... XIX 8.1 Appendix A: Checklist and decision rules for scoring the eight TPA index items ... XIX 8.2 Appendix B: Examples of the coding of the eight TPA index items ... XXI

L

IST OF

A

BBREVIATIONS

ATADBEPS

Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive Base erosion and profit shifting CBC Country-by-country

CPB Centraal Planbureau

CPM Cost-plus method

CSR Corporate social responsibility CUP Comparable uncontrolled price

EBITDA Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization ESG Environmental, social and governance

ETR Effective tax rate

EU European Union

EY Ernst and Young

G20 Group of Twenty

GDP Gross domestic product GRI Global Reporting Initiative HTVI Hard-to-value-intangibles

ITC Income Tax Code

KPMG Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler MNC

MNE

Multinational corporation Multinational enterprise

OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development PPL Profit-participating loan

PWC PricewaterhouseCoopers RPM Resale price method

TNMM Transaction net margin method VIF Variance inflation factor

L

IST OF

F

IGURES

Figure 1: Top marginal corporate tax rates have declined since 1980 ... 4

Figure 2: Example of double non-taxation (PPL) ... 7

Figure 3: Example of treaty shopping ... 8

Figure 4: Example of interfirm royalties ... 10

Figure 5: Example of setting up a cash pooling unit ... 11

Figure 6: Example of transfer pricing ... 15

Figure 7: Example of the comparable uncontrolled price method ... 17

Figure 8: Example of the resale price method ... 18

Figure 9: Example of the cost-plus method ... 19

Figure 10: Example of the transaction net margin method ... 21

Figure 11: Example of profit split method ... 23

L

IST OF

T

ABLES

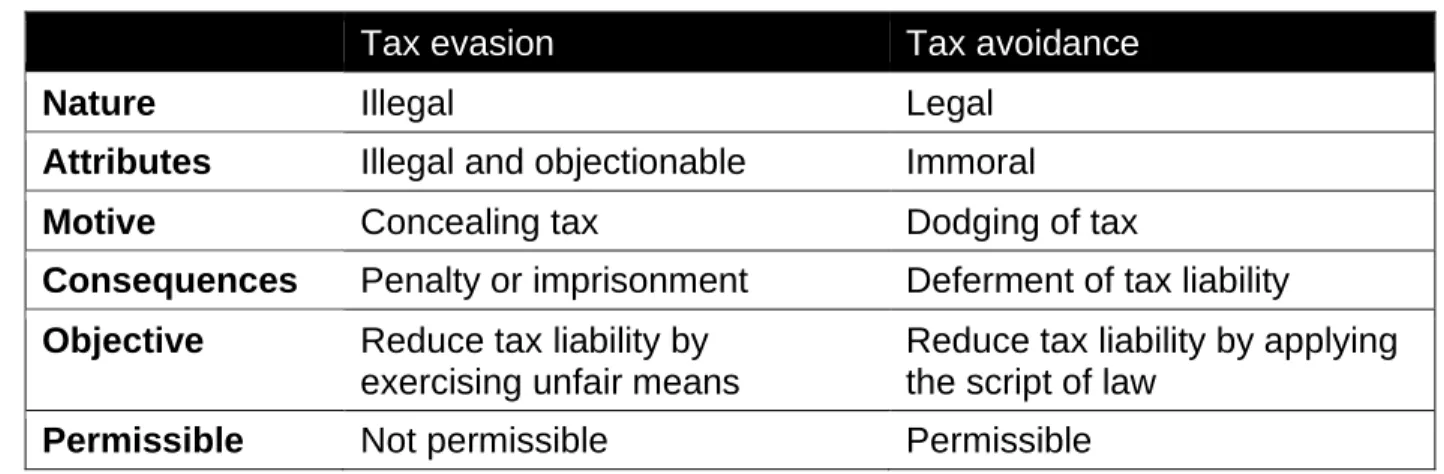

Table 1: The difference between tax evasion and tax avoidance summarized ... 5

Table 2: Distribution of companies in final sample over different sectors ... 45

Table 3: Descriptive statistics of the different items that compose transfer pricing aggressiveness ... 49

Table 4: Description of variables used in the base regression model ... 53

Table 5: Descriptive statistics of the sample variables ... 55

Table 6: Correlation results: Pearson correlation matrix ... 57

Table 7: Correlation results: variance inflation factors ... 58

Table 8: Base regression model results ... 59

Table 9: Paired sample correlation ... 60

1 I

NTRODUCTION

International corporate tax avoidance represents a significant concern for many Western countries (Christensen et al., 2004). Many national governments lose billions as a result of this phenomenon. According to a study led by the Socialist and Democrats’ group (2019), tax avoidance costs the European Union nearly 825 billion euros every year. In order to reduce this loss as much as possible, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) developed a plan to address base erosion and profit shifting (OECD, 2013).

Recently, the aggressive tax avoidance behavior of some multinationals has attracted a lot of media attention. Many of these firms appear in the newspapers with very low effective tax rates (ETR). An example of such a company is Amazon, which only has an effective tax rate of 1.2% for 2019 (Rubin, 2019). This master’s dissertation examines the major determinants of tax avoidance as a means by which firms can significantly reduce their corporate tax liabilities. Based on a hand-collected sample of 40 publicly listed Belgian and Dutch firms for the 2018 year, we develop a model that defines the different antecedents of tax avoidance.

This research contributes to the existing literature in several ways. First, more and more studies have already examined the influence of company-specific characteristics, such as company size, capital structure and profitability (Rego, 2003; Richardson and Lanis, 2013). Unfortunately, these models have low explanatory power. The model in this master's dissertation wants to add some unique variables that have not been researched yet before. For this reason, variables such as audit fees, transfer pricing aggressiveness, corporate social responsibility strategy scores and environmental, social and governance controversies are added. Second, this study provides valuable information about the major determinants of tax avoidance to policymakers and regulators who can find these results interesting in terms of developing policies and regulations. Finally, this study examines the impact of the interaction between multinationality and corporate social responsibility scores.

The remainder of this master’s dissertation is structured as follows. The second section provides an overview of the existing literature and defines the most important concepts. The third section summarizes the legislation on a global and local level. In the fourth section, the various hypotheses are developed. The fifth section provides information on the data collection and the measurement of the different variables. The following section presents the statistical analysis and describes the research results. Finally, an overall conclusion is provided followed by some limitations and recommendations for future research.

2 T

HEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND LITERATURE

REVIEW

2.1 Multinational corporations in the globalized economy

This master's dissertation focuses predominantly on multinationals. This concept has many synonyms in the literature, such as multinational enterprise (MNE), multinational corporation (MNC), transnational corporation (TNC), etc. Richard Caves (1996), who is recognized for his work on multinational enterprises, defines multinationals as follows: “A

multinational is an enterprise that controls and manages production establishments or plants, that are located in at least two countries” (p.1). This definition highlights two

essential aspects. First, it is important to emphasize the international aspect. We do not talk about a multinational when it only operates in one country. Second, it is essential to notice that a multinational enterprise is a collection of multiple entities under the control of one single corporate structure or entity.

Nowadays, multinationals play a conspicuous and controversial role in the global economy. Their profit-seeking interest brings them often into conflict with the interests of the citizens of the countries in which they operate. Recent research conducted by the Financial Times (2018) shows that while citizens have started to pay more taxes over the past ten years, multinationals are losing less to the tax authorities. For the study, the British business newspaper surveyed one hundred of the largest listed companies worldwide, spread across nine economic sectors. This research created a lot of commotion, followed by various political discussions. One possible explanation for the falling taxes is the Western tax competition (Keuschnigg et al., 2014). In order to attract more activity or to prevent companies from leaving, countries start to lower their tax rates as illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1:TOP MARGINAL CORPORATE TAX RATES HAVE DECLINED SINCE 1980

SOURCE:TAX FOUNDATION.DATA COMPILED FROM NUMEROUS SOURCES INCLUDING:PWC,KPMG,

DELOITTE AND THE USDEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE.

2.2 Tax evasion and tax avoidance

Tax evasion and tax avoidance are two concepts that are often used interchangeably. Nevertheless, they have a different meaning. This difference has a huge consequence: where tax avoidance will lead to paying fewer taxes, tax evasion could result in paying fines and possible imprisonment. In the event of tax evasion, it is no longer feasible to speak of legal behavior. It is considered as an illegal activity in which a person or entity intentionally avoids paying taxes. This often involves illegal practices such as making false statements, presenting personal expenses as business expenses, etc. (Roggeman, 2019).

The European Union (2018) stated that “every single day around a fifth of all public money

in Europe is lost to tax fraud and evasion" (p.78). The fight against tax fraud and tax

evasion has become more and more challenging. In this context, it is increasingly important to exchange information between the various tax authorities. The collecting of taxes and the fight against tax evasion are the responsibility of the national authorities. However, nowadays a lot of tax evasion happens across borders. Interventions at an international level are needed to address such problems.

In the continuum of tax planning strategies provided by Hanlon and Heitzman (2010), we find that tax avoidance or “the choice of the least taxed” can be situated next to tax evasion. The big difference with tax evasion is that tax avoidance is considered as a legal act. For example, businesses can avoid paying taxes by taking all legitimate deductions. Table 1 shows the main differences between tax evasion and tax avoidance.

TABLE 1:THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN TAX EVASION AND TAX AVOIDANCE SUMMARIZED

Tax evasion Tax avoidance

Nature Illegal Legal

Attributes Illegal and objectionable Immoral

Motive Concealing tax Dodging of tax

Consequences Penalty or imprisonment Deferment of tax liability Objective Reduce tax liability by

exercising unfair means

Reduce tax liability by applying the script of law

Permissible Not permissible Permissible

SOURCE: OWN PROCESSING

Within tax avoidance, however, companies often act against the limits of the law. This is why it is often called the “grey zone”. An example is the case when a company interprets the law extremely strictly to get a tax reduction, in a situation in which it was not the intention of the legislator. The intentions of the companies (the subjective element) are, therefore, sometimes questioned. This is commonly described as hard tax planning. As a company, you must be able to demonstrate that, in addition to tax advantages, there are also economic motives (Beer et al., 2018).

2.3 Tax avoidance strategies

Over the last decade, tax avoidance has been a much-discussed topic on the global political agenda since it affects different stakeholders in society (Lord, 2017). First, national authorities lose a large part of their revenues on taxes. The Tax Justice Network (n.d.) estimated that around $500 billion of tax revenues are lost on tax avoidance. In this

of the State, the individual taxpayers. As a result of the lost revenues of the State, they have to bear more tax charges. The last group to mention are the small enterprises. They lose part of their competitive position because they cannot shift their profits. This creates an unfair competition (Gravelle, 2010; Contractor, 2016).

Corporate taxes are an enormous cost for companies. For this reason, they generally assess the implications of taxes for every decision. In this master’s dissertation, we will give an overview of several tax avoidance strategies. The next sections will provide an overview of how companies can reduce their tax burden. The following most important strategies will be discussed: double non-taxation, treaty shopping, the minimization of the taxable base in a heavily taxed jurisdiction, corporate inversions, and transfer pricing (Contractor, 2016).

2.3.1 Double non-taxation

Double non-taxation can occur when there are certain distortions in the law between two different countries, States or jurisdictions. Furthermore, this situation takes place when two countries are not aligned fiscally. A well-known example is the profit participating loan (PPL), which is illustrated in Figure 2. The PPL is a special form of a loan, a so-called hybrid financing instrument. In this case, the instrument is qualified differently in both countries. In the illustrated example, suppose that the company in Luxembourg is going to buy shares of the Belgian company. In Luxembourg, this transaction is qualified as a capital participation in equity. However, in Belgium, it can be categorized as borrowed capital. In this situation, we classify the paid money as interest which will be deductible from the taxable result. In Luxembourg, the received dividend is exempt as income. As a result of this construction, taxes are saved (Deloitte, 2014; Roggeman, 2019).

In order to better illustrate the tax savings that can be achieved, we will make a brief comparison in numbers between the correct classification and the incorrect classification as PPL. The first situation shows the case wherein both countries classify it as a loan, while the second situation shows the case where it is classified as a PPL. For the year 201X, the interest was €500. If the Belgian company has a profit of €1,000, it can now

reduce its taxable base by deducting the interest. In this case, only €500 will be taxable. Assuming that the tax rate is 34%, we can conclude that the Belgian company needs to pay €170 on taxes (€500*34%). In Luxembourg, however, the tax rate is only 21%. Hence, they will have to pay €105 (€500*21%). Therefore, the company will have to pay €275 in the first situation. In the second case of hybrid financing, the Belgian company again needs to pay €170 on taxes as illustrated above. For Luxembourg, however, the situation is different now. If you receive a dividend within European entities, the receiving party does not have to pay taxes on it. A dividend is assumed to be taxed as part of its profit. Hence, you would get double taxation. For this reason, it is exempt. This makes that in Luxembourg you do not have to pay any taxes (Roggeman, 2019).

FIGURE 2:EXAMPLE OF DOUBLE NON-TAXATION (PPL)

SOURCE: OWN PROCESSING BASED ON DELOITTE (2014)

2.3.2 Treaty shopping

The second example of a contentious tax avoidance strategy is treaty shopping. The term itself has never been properly defined or explained by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). In the documentation of the OECD, the emphasis is on eliminating this phenomenon. The first operational definition of treaty shopping was provided when the OECD released its action plan against it in 2015. The definition goes as follows: “Treaty shopping occurs when companies seek to take advantage of tax

treaties between two contracting states using a shell company based in a third jurisdiction.” (OECD, 2015, p.23). In this method of tax avoidance, the company is looking

Even though a company is not a resident of the two States that conducted a tax treaty for its residents, there is a possibility to get benefits through treaty shopping. This often happens in States with desirable tax treaties. In literature, this is often referred to as “shell companies” or “letterboxes” since these companies only exist on paper and do not have any substance in reality. Typically, this type of corporation does not provide any actual products or services (Reinhold, 2000; Bonckaert et al., 2017).

FIGURE 3:EXAMPLE OF TREATY SHOPPING

SOURCE: OWN PROCESSING BASED ON OECD(2015)

In Figure 3, an example of treaty shopping is given. Company A, a resident at the Cayman Islands, is licensing its intellectual property to company B in South Africa. With the help of a letterbox company in Slovakia, there is a possibility of treaty shopping. In this example, there is no tax treaty in place between the Cayman Islands and South Africa. Slovakia, on

the other hand, does have a tax convention with South Africa under which no withholding tax is applied on royalties. Since Slovakia’s domestic law does not call for withholding tax on outbound payments, royalties for the group are not taxable in either company A, B, or C (OECD, 2015).

2.3.3 Minimization of taxable base in a heavily taxed jurisdiction

During this minimization, the taxable base in less heavily taxed jurisdictions is maximized. Various methods are possible to reach this result (Bonckaert & De Muer, 2017; Gashenko et al., 2018).

For the first method, we are looking at the payment of royalties. These are fees paid to the owners of legally protected intangible property by those who use these intangible assets. You can avoid taxes by entering into internal royalty contracts. In this case, the most heavily taxed jurisdiction pays royalties to the less heavily taxed jurisdiction. The results are twofold: on the one hand, you will have a higher amount that is taxed at a lower rate, while on the other hand you will have a lower amount taxed at a higher rate (Claeys & Verborgt, 2019).

The popularity of interfirm royalty payments can be explained by several rationales. First, it can be explained by looking at our current society, which is becoming more and more technology-oriented. From this point of view, it is therefore logical that royalties are becoming more and more common in companies. A second reason to opt for royalties is the deductibility. Most governments allow deductions for royalty payments, which reduces the tax liability of a company. This is even the case if the licensee is part of the multinational. As a result, the company’s overall tax burden is reduced (Claeys & Verborgt, 2019).

An example of how interfirm royalties can reduce your tax liability is provided in Figure 4. In this illustration, we have a company A, which is located in Japan. This company has done a lot of research and development and established a subsidiary in the United States, named company B. The Japanese parent has signed an agreement with its US subsidiary

in the US and increases the total remittance in Japan. By showing this example, it is clear that a side royalty agreement is only interesting in the case where the effective tax rate in Japan is lower than the US tax rate. It can even be more interesting to transfer the patent rights to a subsidiary in a low-taxed jurisdiction, such as the Cayman Islands, Ireland, etc. By making them the licensor, they would be taxed at an even lower corporate tax rate (Contractor, 2018). This technique is very popular according to the Independent (2018), a British online publisher of news, which states that almost a quarter of Ireland’s gross domestic product (GDP) is made out of tax avoidance royalties. Ireland is a popular country since the corporate tax is only 12.5%, which is half of the OECD’s average.

FIGURE 4:EXAMPLE OF INTERFIRM ROYALTIES

SOURCE: OWN PROCESSING BASED ON CONTRACTOR (2018)

A second method to minimize the taxable base is to set up a cash pooling company in a country with a lower tax burden. This company provides several loans to affiliated companies that are located in other countries. As a result, revenues will increase in the country with the low tax burden in which they will be taxed less. The interest expenses for the affiliated company are deductible. Consequently, the tax burden is likely to decrease (Bonckaert & De Muer, 2017).

In recent years, the legislation has evolved in this domain. These changes have become permanent as from assessment year 2020. The financing cost surplus, which is equal to the difference between the interest cost and interest income, is not deductible if it exceeds the amount of €3,000,000 or 30% of the fiscal earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation

and amortization (EBITDA). This rule applies to foreign intra-group interest and interest to third parties. The old thin-capitalization rule continues to apply for interests payable to tax haves and interests on loans contracted before June 17, 2017. Interest payments that excess a 5:1 debt-to-equity ratio are not deductible. Equity is in this definition interpreted as the sum of the taxed reserves at the beginning of the taxable period and the paid-up capital at the end of the taxable period. However, according to Article 54 ITC, if the interest rate exceeds the market rate, it will all be rejected. The company can, nevertheless, prove that these transactions were genuine and sincere and that they fall within the normal limits (Roggeman, 2019).

FIGURE 5:EXAMPLE OF SETTING UP A CASH POOLING UNIT

SOURCE: OWN PROCESSING BASED ON MESSNER (2001)

In Figure 5, a practical example of a cash pooling unit is illustrated. As mentioned before, a central company is established in a country where the tax rate is low. In this case, the chosen country is Albania, where the tax rate is only 15%. Various loans will be given towards affiliated companies, which are located in different countries with a higher tax

rate. By issuing these loans, the Albanian company will obtain interest income from the other companies. This income will be taxed at a much lower rate. As a result, the overall tax burden of the entire company decreases (Messner, 2001).

2.3.4 Corporate inversions

Another strategy that many multinational corporations use to change how and where their income is taxed, is called a corporate inversion. This fourth technique follows roughly the same reasoning as the previous ones: it tries to reduce the worldwide tax payments for a company by changing the company’s headquarters to a lower-taxed jurisdiction. This scenario is achieved through a merger or acquisition with a foreign firm. In other words, an inversion changes the way of taxation by relocating the operations of the company (Bonckaert et al., 2017; Neely et al., 2017).

Corporate inversions are often used by companies that have a significant portion of their sales in foreign countries. Consequently, they are typically taxed twice: once abroad and once in their country of origin. By doing a corporate inversion, they domicile their daily activities in the new country. Hence, they will be taxed only once at a lower rate than before (Neely et al., 2017). The Congressional Budget Office (2017) estimated that among companies that inverted from 1994 through 2014, the corporate taxes fell by, on average, $45 million in the financial year after the inversion. As long as multinationals have the perception that their home nation taxes are excessive towards other nations, inversions will resume in the future.

There is a great deal of resistance to corporate inversions by world leaders. Obama (2016) targeted this phenomenon and described it even as an “insidious loophole”. He tried to eliminate some of the injustices in the tax system. Therefore, he included provisions that were meant to discourage companies from shifting profits in order to reduce the corporate inversions. This action was credited by many tax analysts. However, as it is often the case, world leaders do not always have the same vision. From this point of view, President Trump (2017) has, therefore, decided to declare the legislation under Obama annulled (Tankersly, 2019).

2.3.5 Transfer pricing

The last tax avoidance method is the most important one in the context of this master’s dissertation. The method we are now discussing is called transfer pricing. Nowadays, there is a growing national and international interest in this concept. De Tijd, a financial newspaper in Belgium, published the following headline in February 2019: “Tax authorities

claim record amount from multinationals” (p.13). In this article, it is stated that a large

number of transfer pricing matters continue to reach the court. The investigations are in the hands of a specialized unit in the Belgian tax department. As a result of much media attention, the number of transfer pricing controls has increased. In 2019, the Belgian government even announced that it was one of the objectives of the tax administration to detect the misuse of transfer pricing. During that year, the special unit dealt with 132 files and claimed over €89.74 million in taxes from the targeted multinationals (Bové, 2019). In the following sections, the concept of transfer pricing is first explained and further clarified with an example. Next, the most important transfer pricing methods are discussed.

2.3.5.1 Concept

Transfer pricing is an important consideration for all companies with cross-border or intra-group transactions. After all, it can bring a lot of strategic advantages. In order to be able to discuss these benefits, we first need to gain a better understanding of the concept (Heimert et al., 2018). The European Commission stated in 2009 that transfer prices are “the prices at which an enterprise transfers physical goods and intangible property or

provides services to associated enterprises” (p.19). In other words, a transfer price or

transfer cost is the price at which related parties transact with each other. Related parties have to be connected through a commercial relationship. This is the situation when one company has a direct or indirect participation in management, control or capital of another company. Another case of this situation is when both companies are part of the same group. The content of the transaction can also be very divergent. It can range from goods to services, intellectual property or even financial arrangements.

Multinationals can manipulate transfer pricing in order to reduce the taxable base. Moreover, they can shift profits from a high to a low-tax jurisdiction. This is achieved by asking high prices to associated companies that are localized in a low-tax country. By following these steps, they make larger profits in a low-tax jurisdiction, while they make fewer profits in high-tax regions. Companies can gain a lot of tax benefits through this method by altering their taxable income and thus reducing their overall taxes. They use transfer pricing as a method of allocating their EBIT among its subsidiaries within the organization (Rugman et al., 2017).

Transfer pricing is not illegal or abusive as long as we are not talking about transfer mispricing. In this case, the multinational is simulating his numbers to deceive the tax authorities. For this reason, the arm's length principle was introduced. In brief, this means that the price should be the same as if two independent companies were involved. Other measures taken by public authorities to counteract the event of transfer mispricing are provided in Section 3. This makes that additional time, money and manpower is required for matching the accounting system with the rules (Tax Justice Network, n.d.).

Figure 6 explains how transfer pricing can manipulate the results. In this case study, we have three companies: mother company A that is situated in Indonesia, daughter company B that is situated in Liberia, and daughter company C that is situated in Serbia. Due to the fact that A participates directly in the capital of both B and C, they are all associated entities. An internal sale is controlled by the multinationals and is, therefore, called a controlled transaction. This is not the case when selling goods to an independent third party, where the prices are set by supply and demand. The price at which the car is sold by B towards C affects their individual financial performance. If B asks a high price, B will make more profit and vice versa. From a commercial perspective, the price does not matter due to the fact that we look at the consolidated results. However, from a tax perspective, it does matter. As mentioned above, both companies are located in different countries with other corporate tax rates. The multinational wants to maximize its profit after taxes as much as possible. In this way, he wants to achieve the highest profits in

Serbia, where the company needs to pay the lowest taxes. Therefore, he wants that the car is sold at the highest price possible.

FIGURE 6:EXAMPLE OF TRANSFER PRICING

SOURCE: OWN PROCESSING OF A SELF-INVENTED EXAMPLE

2.3.5.2 Methods

The OECD’s Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations provide several methods to determine an accurate arm’s length price. Moreover, it also explains how these methods can be used in practice. According to these guidelines, five methods are consistent with the arm’s length principle. The choice of methodology depends on different facts and considerations: the strengths and weaknesses of each method, the type of the controlled transaction, the availability of reliable information that is needed and the degree of comparability between the controlled and uncontrolled transactions. It is, therefore, important to understand the whole process of the transaction (KPMG, 2016).

The five methods are divided into two general categories. On the one hand, we have the

traditional transaction methods, which include the comparable uncontrolled price method,

the cost-plus method and the resale price method. On the other hand, we have the

transactional profit methods, which include the transactional net margin method and the

profit split method. Traditional transaction methods measure the terms and conditions of the actual transactions, while transactional profit methods do not look at the actual transactions. The transactional profit methods are less accurate than the traditional transaction methods, even though they are more often applied in practice. This is due to the fact that traditional methods require more detailed information which is not always available (Feinschreiber, 2004).

Each of the previous methods will be discussed below. For more complex operations, one single method may not always be accurate. Therefore, different methods must be combined. As soon as the choice has been made for a particular approach, this approach must be followed consistently. The method must be determined on a case-by-case basis. Hence, no method applies to all situations. It will, therefore, always be necessary to determine which methods are applicable in order to determine which method can be used (Feinschreiber, 2004).

The OECD guidelines create a certain hierarchy among the different methods in order to simplify the choice. The comparable uncontrolled price (CUP) method is recommended as the first method to be tested. This is because the CUP method is the most direct and reliable. If the CUP method cannot be applied, companies are allowed to look at the other methods. In that case, however, the OECD guidelines recommend to first look at the traditional transaction methods (OECD, 2010).

2.3.5.2.1 Comparable uncontrolled price method

The most common method is the comparable uncontrolled price method, often referred to as the CUP method. In this case, the price of the services or property of a controlled transaction between two related parties can be compared with three different options. The first choice can be to compare it with the price of a similar transaction between the

company and an unrelated party. This is called the internal price. A second possibility is to look at the external price, which is the price of a comparable transaction between two unrelated parties. The last option is to look at publicly available information on comparable transactions between two unrelated parties. This concept is called the aggregated information on external prices. If the comparison shows large differences, this may be an indication that the transaction was not carried out at arm’s length (Dalloshi et al., 2012). In order to carry out this comparison correctly, there are some requirements attached to it. One requirement is that there should be no material differences between the transactions. These discrepancies could otherwise have an impact on the price. Therefore, issues such as delivery terms, contractual terms, etc., should be included in the analysis. The OECD has listed all possible issues. It can be noted that this hampers the comparison. It will always be difficult to know all the details of every transaction. Consider, for example, services or intellectual property. In these cases, there is often not even a duplicate. Therefore, it needs to be assessed individually. Despite this disadvantage, this method is used quite frequently (Dalloshi et al., 2012).

FIGURE 7:EXAMPLE OF THE COMPARABLE UNCONTROLLED PRICE METHOD

In Figure 7 an example of the CUP method is illustrated. Company A is a corn producer that is selling its product to an associated entity B. The controlled transaction and the other transactions (internal and external transaction) can be seen as comparable if they happen at a similar time and take place in the same stage of the production chain. The price of the controlled transaction can now be compared with the price of the external and/or internal transaction. If there is no significant difference between the prices, the transfer price is at arm’s length.

2.3.5.2.2 Resale price method

The resale price method (RPM) is a second method to verify whether a transaction reflects the arm’s length principle. It starts by analyzing the selling price of a third party whereby the gross margin is calculated. This ratio is defined as the net sales minus the costs of goods sold. Subsequently, this margin will be used to calculate the market price. In this method, the arm’s length price is determined by deducting the margin from the sales price requested by the unrelated entities (Feinschreiber, 2004).

As with the CUP method, individual differences in transactions must be taken into account. If material differences are affecting the price, this method cannot be used. It is also important to note that the costs must be calculated accurately. Thus, the disadvantage of this method is that it can be very difficult to have the appropriate data available (Valentiam, 2019).

FIGURE 8:EXAMPLE OF THE RESALE PRICE METHOD

To facilitate the understanding of this principle, Figure 8 is introduced. In the example in this figure, company A and B are associated enterprises. Company B is a wholesaler and will further distribute this pie towards various markets. Company A charges €10 for a pie and company B sells this product to its customers for €15. The challenge is now to find independent transactions in the same market. Suppose that the independent market in this example has a gross margin of 10%. The fee between companies A and B will then not be in line with the market. The correct price for this transaction should, therefore, be €13.50 (€15-(15*10%)).

2.3.5.2.3 Cost-plus method

The third method that is provided by the OECD is the cost-plus method (CPM). Hereby, the market price is determined by adding a specified mark-up to the costs that were incurred. This mark-up is determined by analyzing and reviewing companies that do similar uncontrolled transactions. Hence, the market price equals the costs plus a profit margin. Determining the accurate price is not an effortless task. Usually, companies do not have a correct image of how the cost of competitors differentiates. They will often have a general idea of the costs, but they will not be able to determine in detail which cost is incurred for which product (Feinschreiber, 2004).

FIGURE 9:EXAMPLE OF THE COST-PLUS METHOD

Figure 9 provides an example where we assume that we have a reliable estimate of the costs of comparable competitors. In this example, company A is a milk producer that sells its milk to its affiliated company B. In order to determine the price, a similar independent company that also manufactures milk should be considered. In this case, the producers of similar products will use a margin of 15% on top of the costs that were incurred. If the cost of production for company A is €1, then the correct market price is €1.15 (1+(1*0.15)). The cost-plus method is the reverse situation of the resale price method. The RPM will deduct a margin from the income to determine an appropriate arm’s length price, while the CPM adds a margin to the cost price in order to determine the arm’s length price (De Smet, 2016).

2.3.5.2.4 Transactional net margin method

In this and the next section, the transactional profit methods are discussed. These methods are mainly used in situations when there is insufficient information to apply the previous methods. In these circumstances, it is not possible to determine a clear and accurate market price. The OECD (2010) advises to only use these methods in these predefined situations. The transactional net margin method (TNMM) examines the arm’s length character of a transaction. Moreover, it compares the operating profit that is obtained in a controlled transaction with the operating profit that is obtained in an uncontrolled transaction (Boquiest, 2009; De Smet, 2016).

The TNMM will specifically examine the net operating profit of a controlled transaction. The importance of similar transactions is also emphasized with this method. If the company does not have similar transactions with an uncontrolled company, other companies that have such transactions should be sought. As with the previous methods, attention should be given to the individual details of the transaction. (Boquiest, 2009). The OECD (2010) advises doing a comparative analysis. The main disadvantage of this method is that net margins have high volatility and that they are usually influenced by many factors. Moreover, we may also need a lot of information that may not be available to us. If we do have this information at our disposal, this method can turn out to be very

expensive. Collecting information needs to be detailed, which can consume a lot of time and money.

Figure 10 illustrates the TNMM through an example. In this case study, there is a company A that sells laptops to its associated company B. Company B will have to pay a correct transfer price for these laptops. In the event that company A does not sell laptops to other unrelated companies, it will be necessary to look for similar companies within the laptop production market. Once these entities are found, a net operating margin can be determined by analyzing the figures. All these companies will have their own different margin, which ends up in a range of possible margins. Suppose that the mark-up on total operating costs is found to be at a minimum of 0.5% and a maximum of 5.5%, with a median of 3.5%. The company will then have to defend itself why it chooses a certain percentage that falls within this selection. Assume that the company has chosen a mark-up of 3%. Given that the operating costs equal €500, the arm’s length price will be €515.

FIGURE 10:EXAMPLE OF THE TRANSACTION NET MARGIN METHOD

SOURCE: OWN PROCESSING OF A SELF-INVENTED EXAMPLE

The TNMM shows similarities with both the RPM and CPM. They are all trying to achieve the same result, but each in a different way. While the TNMM will look at the costs or revenues divided by the profit, the two other methods will look at the price of the transaction in order to determine the correct margin (De Smet, 2016).

2.3.5.2.5 Profit split method

The last approach that is discussed is the profit split method. This method aggregates the operating profits of associated companies. According to a certain distribution key, these profits are split. The distribution of these aggregated profits takes place in two phases. In the first phase, the OECD wants to ensure that each entity receives a minimal compensation for the tasks that were performed. Hence, the purpose of this phase is to guarantee that all costs are covered for both entities. In the second phase, the remaining profits are distributed. For the allocation, companies need to look at how independent firms distribute their profits. The choice of a specific distribution key must always be justified by an in-depth functional analysis (Feinschreiber, 2004; KPMG, 2016).

First and foremost, in order to be able to use this method, companies must be closely working together. Moreover, they must make a significant contribution to the value creation of the product. As a result of this close cooperation, independent companies would choose to share in the profits. Since both companies are analyzed, there is no possibility to create a disproportional distribution of profits. The analysis of both companies ensures that each company gets the share it is entitled to. The two-sided analysis provides a more precise overview (Feinschreiber, 2004; KPMG, 2016).

This method also has some disadvantages. First, it requires a lot of information, which is also very difficult to obtain. As a result of this excessive need of information, this method turns out to be very expensive. Second, it can only be used in some limited cases. The optimal number of companies in this method is two. After all, if there are too many companies, it will be too difficult to obtain a correct allocation key (Feinschreiber, 2004; KPMG, 2016).

Figure 11 further demonstrates this method with an example. Company A and B are associated companies. Company A is a developer of vaccines, while company B is responsible for its distribution. The companies are closely linked and cannot operate without each other. Company A needs to sell its vaccines at a market price towards B. When using the profit split method, all revenues will first be added together. Suppose that

the combined revenues are €2,000. These €2,000 will first be used to cover the costs of both companies. After deducting these costs, €800 remain to be distributed (€2,000 - €800 - €400). For this further distribution, both companies need to be analyzed. This analysis can look at the total assets, employees, costs, etc. In this example, the distribution key is assumed to be 70/30. This results in a profit of €560 for company A and a profit of €240 for company B.

FIGURE 11:EXAMPLE OF PROFIT SPLIT METHOD

3 R

EGULATORY FRAMEWORK

According to the various concepts cited in the previous section, it appears that multinationals shift their profits in order to pay fewer taxes. As a consequence, a great deal of the national revenues is lost. Unfortunately, there is rarely anything a country can do individually. Hence, in order to tackle this problem, a certain form of cooperation is needed. In addition, it is not always easy to change legislation quickly. Businesses must be given a transitional period to apply with these regulations (Kavelaars, 2013).

In order to help dealing with the problem of national revenue losses, the OECD has introduced fifteen guidelines (OECD, 2013). In this master’s dissertation, the most important ones in the context of transfer pricing are discussed. Concerning the implementation of these guidelines, good coordination between the various countries was and is required. Even now, we can still see that this is not evident.

3.1 European framework

In the past few years, the international tax landscape has changed radically. The globalization of companies has created new challenges and possibilities. As a consequence, many governments suffer from major losses. The OECD (2013) estimated an average annual revenue loss of €170 billion due to base erosion and profit shifting. As a result of these large losses, there was a lot of pressure to deal with this problem. The solution offered by the OECD is discussed in detail below: the BEPS.

In addition to the BEPS, other initiatives are provided by different actors. One of these initiatives is the strategic plan which is published by the European Commission. This plan is always written for a specific European legislature. The current fiscal objective is in line with the BEPS. It focuses on coherence and uniformity within Europe (Bonckaert et al., 2017). However, the objectives of the European Commission fall outside the scope of this master’s dissertation and will, therefore, not be further discussed.

3.1.1 Base erosion and profit shifting

In 2013, the OECD published an action plan to tackle the problem of base erosion and profit shifting. These two issues have a negative impact on the national taxation income. The phenomenon of profit shifting occurs when profits are shifted to countries where there are no or hardly any activities. These are the aforementioned letterbox companies that operate in countries with a low tax rate. The other phenomenon of base erosion occurs when a company develops a strategy to reduce its tax base. Therefore, gaps are sought in the legislation. The OECD wants to counter these practices and has therefore developed the BEPS (Bonckaert et al., 2017; OECD, 2013).

In October 2015, the OECD and the G20 proposed a number of reports containing specific measures in the context of the BEPS Project. With this Action Plan, the OECD sets out fifteen action points that address base erosion and profit shifting. These action points should ensure that fewer abuses occur. More than 135 countries and jurisdictions are currently working together for their implementation (OECD, 2013).

The fifteen actions that the OECD (2013) has developed are: ❖ “Action 1: address the challenges of the digital economy;

❖ Action 2: neutralize the effects of hybrid mismatch arrangements; ❖ Action 3: strengthen controlled foreign company rules;

❖ Action 4: limit base erosion via interest deductions and other financial payments; ❖ Action 5: counter harmful tax practices more effectively, taking into account

transparency and substance;

❖ Action 6: prevent the granting of treaty benefits in inappropriate circumstances; ❖ Action 7: prevent the artificial avoidance of Permanent Establishment status; ❖ Action 8: assure that transfer pricing outcomes are in line with value creation of

intangibles;

❖ Action 9: assure that transfer pricing outcomes are in line with value creation of

❖ Action 10: assure that transfer pricing outcomes are in line with value creation of

other high-risk transactions;

❖ Action 11: establish methodologies to collect and analyze data on BEPS and the

actions to address it;

❖ Action 12: require taxpayers to disclose their aggressive tax planning

arrangements;

❖ Action 13: re-examine transfer pricing documentation;

❖ Action 14: make dispute resolution mechanisms more effective; ❖ Action 15: develop a multilateral instrument.” (p.3).

These action points will become more and more important for the future. However, an in-depth analysis of all of these actions would take us too far away from the purpose of this master’s dissertation. It was therefore decided to discuss the most important action points within the context of this master’s dissertation.

A very important aspect in this whole process are the three pillars on which all of these actions are based: coherence, substance and transparency. The aim of the coherence pillar is to achieve an international consistency in corporate taxation. In this way, it tries to conquer three phenomena: double taxation, double non-taxation and the fight of international tax competition. With the second pillar, substance, the OECD aims to achieve a correct taxation. It wants to ensure that the taxation is in line with the content. A company should be taxed when it creates its value. This refers to the place where activities take place, added value is created, decisions are made, etc. Weaknesses in transfer pricing should be identified within the current system. Finally, transparency between countries also becomes an important value. With its action points, the OECD wants to create an exchange of information between the various international tax authorities. This international cooperation would reduce the lack of knowledge about transfer pricing. The improved transparency and data will also help to evaluate the impact of BEPS. Thus, on the basis of these three values, the given fifteen action points were drawn up (OECD, 2013; Lippert, 2016).

3.1.1.1 Action 6

Action 6 is developed in order to avoid treaty shopping, a concept that is already explained in Section 2.3.2. Shortly re-explained, this is a technique in which companies create entities by making use of a double tax treaty. For the OECD, this is one of the most important sources of BEPS concerns. Companies that are involved in treaty shopping undermine tax sovereignty by seeking for benefits in inappropriate circumstances, thereby depriving countries of tax revenue. Countries will, therefore, introduce anti-abuse provisions (Avi-Yonah et al.,2010; OECD, 2015).

The minimum standard on treaty shopping presupposes jurisdictions to include two elements in their tax agreements: “an explicit statement on non-taxation (usually in the

preamble) and one of the three methods of dealing with Treaty shopping” (OECD, 2015,

p.101). Hence, the limitations are now set on the benefits. Entities will have to meet certain conditions before they can take advantage of the benefits of the double tax treaties (Andrew, 2008; Avi-Yonah et al., 2010).

3.1.1.2 Action 8 through 10

With Action points 8 through 10, the OECD deals with the issue of transfer pricing. The transfer pricing results must be in line with the value creation of the multinational group, which corresponds with pillar two (substance). This particular objective was split into three different action points according to the specific “problem” categories, namely intangible assets, risks and capital, and other high-risk transactions (Wright et al., 2016).

Action 8 aims to avoid erosion of the taxable base and profit shifting through the transfer of intangible assets in controlled transactions. The problem with intangibles is that they are mobile and extremely hard to value. By misallocating these assets, the profits are often allocated to less heavily taxed jurisdictions (OECD, 2013; Wright et al., 2016). Action 9 tries to tackle the same problems as Action 8, but only the cause of the profit shifting differs. In this case, it is mainly about the contractual allocation of risks. Allocating risks can include the allocation of profits to these risks. The OECD stated that there should

be some rules that ensure that the profits correspond to the location where they are carried out (OECD, 2013).

Finally, there is Action 10, which focuses on high-risk transactions. One of the topics it deals with is the distribution of profits that come from a controlled transaction and that do not appear to be commercially rational at first sight. This action point also further clarifies the scope of the different transfer pricing methods. Lastly, it also deals with the issue of eroding the taxable base through management fees and head office expenses (OECD, 2019).

3.1.1.3 Action 13

Transparency is one of the core values of the OECD's action points. We already know that, due to the lack of information on corporate income tax, a lot of income is lost by national authorities. Action 13 wants to tackle this lack of knowledge on the part of the tax authorities. As a consequence of this action, all large multinationals are obligated to prepare a country-by-country (CbC) report. This document includes information on the overall allocation of profits, income, taxes, etc. Furthermore, it also includes an accurate description of where the economic activities take place. This document has to be provided to the national authorities, which will then have a better knowledge of the structure of the MNE (Seer et al., 2016).

The article demands more than only a CbC report. Moreover, it states that three documents must be submitted to the authorities: the master file, the local file and the aforementioned country-by-country report. First, there is the master file, which is an umbrella document provided by the parent company. This document emphasizes the structure of the multinational. It identifies the entities that comprise the multinational and tells how these entities play a role in the daily life of the multinational. Second, there is the local file, which is drawn up for each country. It contains specific information on controlled transactions. Moreover, it provides the necessary explanations as to why a particular price or method was chosen. Last, there is the CbC report in which all entities of the MNE are listed. This report includes information on turnover, turnover of controlled transactions,

number of employees, year of incorporation, etc. By providing all this information, the OECD hopes that strange situations, such as letterbox companies, will be noticed more quickly (Marek, 2018).

According to ITC Article 321/3 §1, the master file and the local file are also required as soon as two of the following criteria values are exceeded:

(1) “A total operating and financial income of 50 million euros excluding the non-recurring income;

(2) a balance sheet total of 1 billion euro;

(3) an annual average workforce of 100 full-time equivalents.”

In Belgium, this should be assessed based on the individual annual accounts of the Belgian entity for the previous financial year (Deloitte, 2019).

3.1.2 Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive

The European Commission wants to play an indispensable role in the fight against tax avoidance. Many countries stated that this battle had to be fought on a global level. For this reason, they have developed the Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (ATAD). This directive lays down five minimum standards for all EU Member States. The majority of the new rules apply as of January 1, 2019 (Cédelle, 2016).

In essence, these five rules against tax avoidance established by the ATAD are:

(1) Companies that relocate profit to a jurisdiction with a lower tax rate, still have to pay European taxes;

(2) Member States can court actions against tax structures that are not prohibited by other laws;

(3) companies can have an interest deductibility limitation if the borrowing costs exceed 30% of the EBITDA;

(4) companies have to pay European taxes on profits of products that were paid just before distributing it out of the EU;

(5) companies that invest in subsidiaries in low-tax countries have to pay a dividend tax, that is based on the dividends received by the EU, when little or no tax has been paid on them in the other country (PwC, 2019).

3.2 Belgian framework

Belgium has no specific transfer pricing legislation. However, there are some laws in the Income Tax Code (ITC) which establish rules to ensure that the arm’s length principle is respected. Nevertheless, more and more work is being done on regulation. Recently, for example, BEPS 13 was integrated into the Belgian legislation (EY, 2019).

In the following sections, we will present the most important articles concerning the regulation of transfer pricing. First, we will start with abnormal and benevolent advantages. Hereby, we will be discussing both the perspective of the beneficiary and the perspective of the granter. This is followed by a brief explanation of Article 185 ITC, which deals with the market price of a controlled transaction. Subsequently, the interest on loans between related companies is discussed. Here, both the old and the new legislation are examined. Fourthly, the general anti-avoidance legislation is discussed. Finally, we conclude with the sanctions for non-compliance behavior.

3.2.1 Abnormal and benevolent advantages

An important article in the Belgian legislation is Article 26 ITC, which addresses abnormal and benevolent advantages. In order to understand this law properly, we must first comprehend these two types of advantages. The Administrative Guidelines of the Belgian tax authorities (1993) define an advantage as “the situation in which an acquirer is

enriched and the provider does not receive remuneration equivalent to the advantage provided” (p.6). Now the difference between abnormal and benevolent has to be

explained. An advantage is abnormal when it is contrary to usual commercial practices. In other words, it would not be granted in normal circumstances. Finally, we call an advantage benevolent when there is no quid pro quo in return.

The following examples present situations where there is an abnormal or benevolent advantage.

(1) Selling goods without a profit margin (= at cost price) or selling goods at a reduced profit margin;

(2) buying goods at a higher price than the market price; (3) the granting of loans or advances without any interest; (4) not commanding claims receivables after the due date; (5) the transfer of fixed assets below their actual value.

Under Article 26 ITC’92, it is allowed to increase the taxable basis of a Belgian company by including the abnormal or benevolent advantages that the company has provided to a non-Belgian company. In this situation, these advantages are added to their profit by means of disallowed expenses. However, the legislator does provide one escape clause: the benefit will not be taxable if it directly or indirectly qualifies for the determination of the taxable income of the acquirer. As a result of this clause, the benefit will not be taxable if the recipient of the benefit is a Belgian company that is subject to the corporation tax. Moreover, this is also the case when the acquirer is a foreign company that is taxed on the advantage it has acquired (Asselman, 2009; Roggeman 2018).

The legislator, however, provides an exception for this escape clause in three cases. According to Article 26, paragraph 2 of the Income Tax Code, an abnormal or gratuitous advantage is always added to the profits of the Belgian company when it is granted to a foreign company that is referenced in Article 227 ITC. This exception holds when the advantages are granted to (Article 26 ITC, paragraph 2, 1°, 2°, and 3°):

(1) “A [non-resident enterprise] with which has, directly or indirectly, any links of interdependence in regard to the enterprise established in Belgium;

(2) a [non-resident enterprise] or a foreign establishment which pursuant to the legislation of the country in which it is established is not subject to income tax or is subject to a tax regime which is considerably more favorable than that which governs the enterprise established in Belgium;

(3) a [non-resident enterprise] which has interest in common with the taxpayer or the establishment mentioned in (1) or (2).”

In these situations, the legislator assumes that the advantage is not taxed and, therefore, the escape clause cannot be invoked.

There is, nevertheless, one further point to be made with regard to Article 26. To summarize, Article 26 ITC states that no economic double-taxation should occur when the benefits are taxed on the acquirer. However, this article applies without prejudice to the application of Article 49 ITC and Article 54 ITC. This means that these articles have priority. The deduction of abnormal expenses may be rejected based on Article 49 ITC (even if the acquiring company is taxed on these benefits). The same reasoning applies to Article 54 ITC. Moreover, Article 26 does not apply when Article 54 can be invoked. In this way, benefits provided in the form of excessive expenses are included in the tax result as disallowed expenses (Roggeman, 2019).

The above all covered the granting of abnormal and benevolent advantages. The legislator also deals with the opposite scenario, in which a company receives abnormal or benevolent benefits. According to Article 79 ITC, the acquirer of an abnormal or benevolent benefit cannot deduct current losses from the benefit it obtained. Hence, the advantage will have to be taxed. However, this is on one condition: the advantage must be given by a directly or indirectly linked company. Another article dealing with this subject is Article 207 ITC, which defines which costs cannot be deducted from the obtained abnormal or benevolent advantages.

3.2.2 Market price of a controlled transaction

The key article for the application of transfer pricing within the Belgian legal framework is Article 185 ITC’92. An important element within the transfer pricing concept is the arm’s length principle. The law of June 2004 extended Article 185 with a second paragraph in order to explicitly mention this principle in the Code. This paragraph ensures that profits realized by a Belgian taxpayer, that is part of a multinational group in a cross-border transaction with an associated company, can be adjusted upwards or downwards. This

adjustment occurs when the price of the related transaction is not in line with the market price (Heimert et al., 2018).

The taxable profit can, therefore, go in two directions: upwards and downwards. In the first situation, we talk about profits that should be included in a company's profits if a market price was paid. Therefore, these profits should be added to the taxable base. In other words, the profits that the domestic company should have realized under conditions of free competition between two independent parties, can now be included in its taxable profit. The second situation relates to a company that has included profits to which it is not entitled. These profits must then be taken out of the taxable base (Bonckaert et al; 2017).

Lowering the tax base is causing a lot of commotion within the European Commission. The Belgian government had to justify itself for this action. They were not vindicated by the Commission, which abolished their downward system. Currently, this article can therefore no longer be applied. Belgium was requested to repay an amount of €700 million. Unfortunately, the Committee did not stop there. In September 2019, they announced that they would launch an investigation into the reduction of the taxable base of 39 companies granted by the Belgian State (KPMG, 2019).

3.2.3 Interest on loans

An interesting area to look at in terms of transfer pricing is the interest on loans. This was already briefly mentioned in Section 2.3.3. Interests on borrowed capital from third parties are, in theory, deductible. This rule applies to interests paid to Belgian financial institutions. Out of prudence, some restrictions have been foreseen for other third parties. Moreover, Article 55 ITC states that only the market interest rate is deductible. However, several factors need to be taken into account, such as the nature of the loan, the amount, the term, etc. When a manager grants a loan to his company, the interest can be reclassified as a dividend. Therefore, the interest is only deductible for a limited amount. The revalued part equals the amount at which the interest rate exceeds the market rate or where the advance payments exceed the summation of the paid-up capital (at the end of the taxable

period) and the taxed reserves (at the beginning of the taxable period) (Van Loock, 2014). From assessment year 2021 onwards, there will be a reform of company law, whereby the concept of market interest rates will now be clearly defined by the legislator (Roggeman, 2019).

Interests paid to foreign entities are not deductible when the recipient operates under a significantly more favorable tax regime or when the recipient is established in a tax haven. However, there is one exception to this limitation of deductibility. If the taxpayer can prove that the transaction is genuine and sincere and that it takes place within normal limits, the interest is nevertheless deductible. Another article that covers interest to (suspect) foreign providers is Article 198, §1, 11° ITC. It relates to interest paid to companies that are located in a tax haven or to groups. The interest is deductible to the extent that the total amount of the loans exceeds five times the sum of the paid-up capital (at the end of the taxable period) and the taxed reserves (at the beginning of the taxable period).

In recent years, the legislation has evolved in this domain. These changes have become permanent as from assessment year 2020. The financing cost surplus, which is equal to the difference between the interest cost and interest income, is not deductible if it exceeds the amount of €3,000,000 or 30% of the fiscal EBITDA. This rule applies to foreign intra-group interests and interests paid to third parties. The old thin-capitalization rule continues to apply for interests that are payable to tax havens and interests on loans contracted before June 17, 2017 (Roggeman, 2019).

3.2.4 Anti-abuse provision

In 1993, the Belgian tax authorities introduced Article 344 ITC which created a general tax anti-abuse provision. This article ensures that a company can no longer easily create tax abuse. Tax abuse can arise in two ways: through an objective element or a subjective element. The objective element implies that the taxpayer is acting contrary to the objectives of the legal provision. This is often referred to as the spirit of the law. The subjective element implies that the taxpayer deliberately aims for a tax benefit, or in other words, he is creating this tax benefit intentionally. Proving these elements is easier in