EARLY CAREER TEACHER

ATTRITION

EARLY CAREER TEACHER ATTRITION

Hans Tierens & Mike Smet

Promotor: Mike Smet

Research paper SSL/2015.28/3.1

Leuven, March 2015

Het Steunpunt Studie- en Schoolloopbanen is een samenwerkingsverband van KU Leuven, UGent, VUB, Lessius Hogeschool en HUB.

Gelieve naar deze publicatie te verwijzen als volgt:

Tierens, H. & Smet, M. (2016). Early Career Teacher Attrition. Leuven: Steunpunt SSL, rapport nr. SSL/2015.28/3.1.

Voor meer informatie over deze publicatie hans.tierens@kuleuven.be; mike.smet@kuleuven.be

Deze publicatie kwam tot stand met de steun van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap, Programma Steunpunten voor Beleidsrelevant Onderzoek.

In deze publicatie wordt de mening van de auteur weergegeven en niet die van de Vlaamse overheid. De Vlaamse overheid is niet aansprakelijk voor het gebruik dat kan worden gemaakt van de opgenomen gegevens.

D/2015/4718/typ het depotnummer – ISBN typ het ISBN nummer © 2015 STEUNPUNT STUDIE- EN SCHOOLLOOPBANEN

p.a. Secretariaat Steunpunt Studie- en Schoolloopbanen HIVA - Onderzoeksinstituut voor Arbeid en Samenleving Parkstraat 47 bus 5300, BE 3000 Leuven

Early Career Teacher Attrition | v

Content

Content v

Beleidssamenvatting vii

Introduction 1

Chapter 1. Determinants of Teacher Attrition 5

1.1 Definition of Early Career Teacher Attrition 5 1.2 Determinants of Early Career Teacher Attrition 6

1.2.1 Individual level of analysis 6

1.2.2 Contextual level of analysis 7

1.2.2.1 Teaching Professional Environment 7

1.2.2.2 School Environment 8

1.2.2.3 Geographical Environment 9

Chapter 2. Data & Methodology 11

2.1 Data 11

2.2 Descriptives 12

2.3 Methodology 19

Chapter 3. Results on Early Career Attrition 21

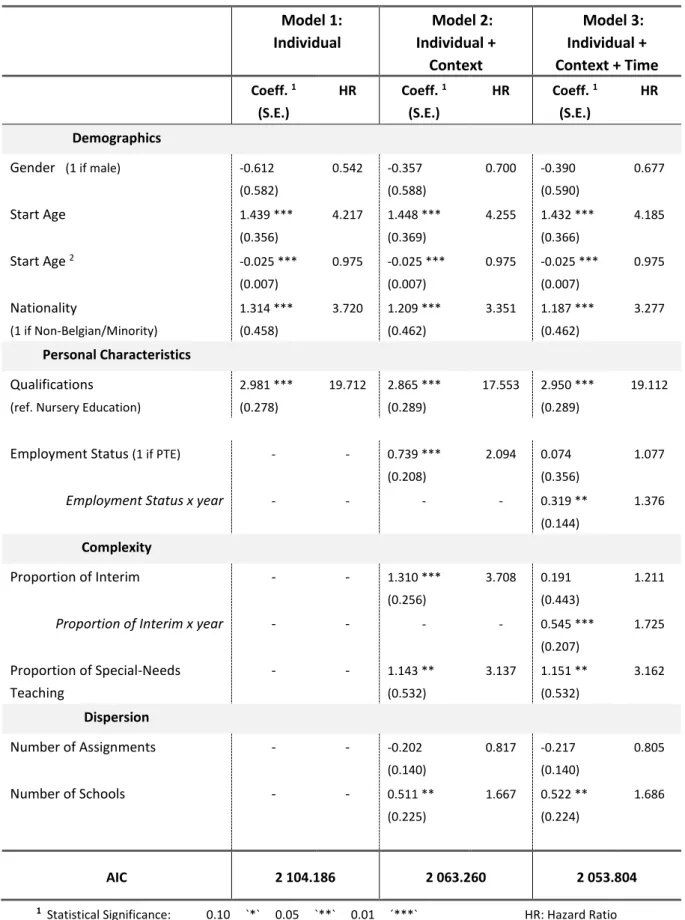

3.1 Nursery School Teachers 21

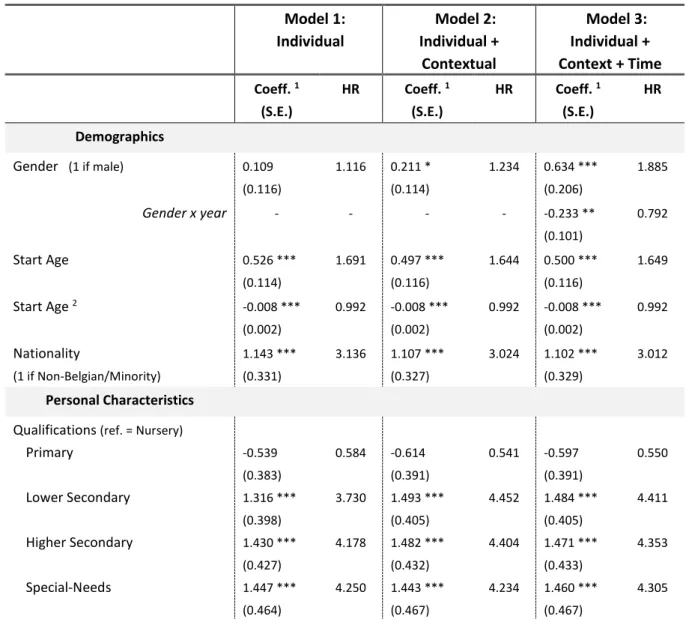

3.2 Primary School Teachers 25

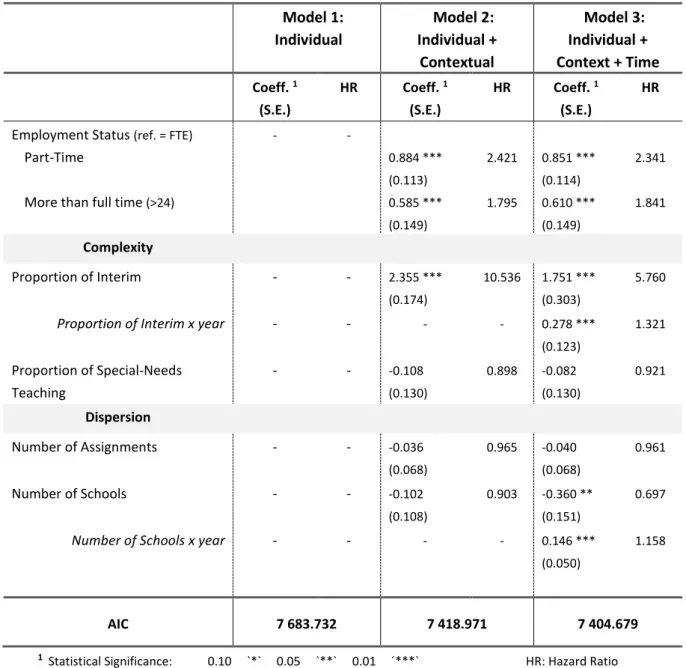

3.3 Secondary School Teachers 28

Chapter 4. Discussion & conclusions 33

4.1 Conclusions on Early Career Teacher Attrition in Flanders 33

4.2 Limitations & Further Research 37

Early Career Teacher Attrition | vii

Beleidssamenvatting

Een centrale doelstelling van de overheid, en meer bepaald het Departement Onderwijs en Vorming, is het voorzien van een onderwijssysteem dat er in samenwerking met scholen in slaagt om elke leerling te voorzien van kwaliteitsvol onderwijs. Hierin kan het belang van voldoende vaardige en gemotiveerde leerkrachten niet onderschat worden. Desalniettemin staat de arbeidsmarkt voor leerkrachten steeds vaker onder druk. Er wordt verwacht dat in de nabije toekomst (binnen een termijn van ongeveer 10 jaar), wanneer de vergrijzende bevolking en ook een vergrijzend leerkrachtenbestand de pensioengerechtigde leeftijd nadert, een tekort kan ontstaan aan leerkrachten, voornamelijk in het secundair onderwijs1. Bovendien stelt de tendens zich dat ook

nieuwe, jonge leerkrachten heel snel weer uit het leerkrachtenberoep uitstromen2. Dit heeft vele

negatieve gevolgen; enerzijds de directe (financiële) kost voor het aantrekken, rekruteren en selecteren van nieuwe leerkrachten en de indirecte (financiële) kost voor het inwerken en verder ontwikkelen van de nieuwe leerkrachten (die verloren gaat bij vroege uitstroom), anderzijds ook de negatieve impact op leerlingenprestaties, door een abrupte onderbreking van het leerproces, en het resterende leerkrachtenkorps, dat een discontinuïteit ervaart bij hoog personeelsverloop.

Personeelsverloop bij leerkrachten kan verschillende vormen aannemen. Zo kan een leerkracht veranderen van school en/of onderwijsniveau, maar toch werkzaam blijven als leerkracht binnen de onderwijssector. Deze vorm benoemen we als migratie. Het is geen zuivere uitstroom, maar ontdoet het onderwijssysteem zeker niet van alle negatieve effecten van verloop. Een tweede vorm is de uitstroom/attritie van leerkrachten, wanneer de leerkracht de onderwijssector verlaat. Deze vorm van verloop wordt gekoppeld aan alle negatieve gevolgen van verloop. In dit onderzoek wordt uitstroom gedefinieerd als het beëindigen van alle onderwijsopdrachten binnen een specifiek onderwijsniveau (i.e., kleuteronderwijs, lager onderwijs en secundair/middelbaar onderwijs). Hiervoor werd steekproef afgelijnd door leerkrachten die exclusief binnen één van deze onderwijsniveau’s werkzaam zijn/waren als leerkracht, aldus werden de ‘migrerende’ leerkrachten weggelaten uit de steekproef.

Dit onderzoek gaat na of de uitstroom in de vroege stadia van het leerkrachtenberoep, beperkt tot de 5 à 7 eerste jaren als leerkracht, verklaard kan worden op basis van persoonskenmerken en enkele kenmerken van het leerkrachtenberoep. Hiervoor werden enkele databanken, ter beschikking gesteld door het Departement Onderwijs en Vorming, aan elkaar gekoppeld. Dit resulteerde in een rijke dataset van leerkrachten die hun diploma behaalden aan hogescholen en universiteiten (i.e., de specifieke lerarendiploma’s aan Centra voor Volwassenenonderwijs (CVO) werden weggelaten). Er werd informatie verkregen over de demografische kenmerken van de individuele leerkrachten, de hogere onderwijs-diploma’s van de leerkracht, de mate van arbeidsinhoud (deeltijds vs. voltijds), het onderwijsniveau waar de leerkracht tewerkgesteld is, het aandeel van interim-opdrachten alsook het aantal opdrachten en het aantal scholen waar de leerkracht werkzaam is. Op basis van deze gegevens werd getracht om de uitstroom te verklaren en daarmee een overzicht te krijgen van waar het schoentje lijkt te knellen bij jonge leerkrachten. Op deze manier kan informatie verkregen worden om de nakende onderwijshervormingen met betrekking tot het leerkrachtenberoep richting te geven.

1 Voor een uitgebreide bespreking van de prognoses: Vlaams Ministerie van Onderwijs en Vorming (2015). Toekomstige

arbeidsmarkt voor onderwijspersoneel in Vlaanderen 2015-2025. (D/2015/3241/342), geraadpleegd via:

http://www.ond.vlaanderen.be/beleid/personeel/files/2015_11_19_WEB_Toekomstige_arbeidsmarkt_voor_onderwijsp ersoneel_in_Vlaanderen_2015_2025.pdf

Om een antwoord te kunnen geven op deze onderzoeksvraag wordt gebruik gemaakt van ‘Cox Proportional Hazards’ modellen, die gebruikt worden om niet alleen na te gaan welke leerkrachten uitstromen, maar ook wanneer deze leerkrachten het leerkrachtenberoep verlaten. Deze modellen vormen een krachtige tool om verloop en uitstroom te begrijpen en verklaren op basis van zowel tijdsonafhankelijke kenmerken van de leerkrachten als tijdsafhankelijke (dynamische) kenmerken van het leerkrachtenberoep.

De resultaten tonen dat ongeveer 11.7% van de nieuwe leerkrachten in het kleuteronderwijs reeds uitstroomden na vijf jaar. In het lager onderwijs bedraagt het uitstroompercentage 15.1%. Het hoogste uitstroompercentage werd gevonden voor het secundair onderwijs, waar ongeveer 31.3% van de nieuwe leerkrachten na vijf jaar reeds het beroep de rug toekeerden. Deze uitstroompercentages geven aan dat de omvang van de uitstroomproblematiek niet gering is en mogelijk een enorm kwaliteitsverlies met zich meebrengt, waardoor de toekomst van het huidige onderwijs(systeem) in het gedrang gebracht wordt. Een vergelijking van de uitstroompercentages uit het leerkrachtenberoep met verloopcijfers van andere beroepen toonde eerder al aan dat de verschillen niet enorm sterk zijn. Het probleem dient waarschijnlijk niet louter bij onderwijs zelf gezocht te worden, wat niet wil zeggen dat de problematiek genegeerd mag worden.

Ingersoll (2001) benoemde het leerkrachtenberoep niet zomaar als een ‘draaideur’-beroep, waarin jonge afgestudeerden even verblijven waarna vervolgens snel weer uit te stromen. Mogelijke verklaringen kunnen gezocht worden in de aanwezigheid en relatieve aantrekkelijkheid van andere beroepen. Hierbij kan het leerkrachtenberoep eventueel gebruikt worden als tijdelijk betaald verblijf of zelfs als springplank richting andere arbeidsmarktposities. Een andere verklaring ligt mogelijk bij werkzekerheidsmotieven. In tijden van economische crisis, in combinatie met eventuele verwachte tekorten aan leerkrachten, lijkt voor velen het leerkrachtenberoep het beroep bij uitstek om enige werkzekerheid te verkrijgen. Hoewel, het huidige onderwijssysteem, meer bepaald het vaak bekritiseerde vastbenoemingssysteem, hanteert anciënniteit vaak als belangrijkste maatstaf voor een vaste benoeming. Dit resulteert in een ‘last-in, first-out’-principe bij personeelsverloop, wat ervoor zou kunnen zorgen dat nieuwe, jonge leerkrachten, als frisse wind door het onderwijssysteem, niet de kansen krijgen die zij zouden verdienen en snel weer verdwijnen uit het onderwijs.

Vooreerst lijken de resultaten met betrekking tot de demografische kenmerken van nieuwe leerkrachten te tonen dat mannelijke leerkrachten, ondanks hun reeds geringe instroomaantallen, sneller uitstromen. Verder lijkt het ook belangrijk om de werk-levenbalans in orde te brengen, opdat het leerkrachtenberoep werkbaar en leefbaar werk wordt/blijft. De resultaten toonden immers ook dat leerkrachten die voor hun dertigste levensjaar hun leerkrachtencarrière startten een hogere uitstroomkans hebben dan wanneer zij later hun carrière in onderwijs zouden starten. De oorzaak kan hier gezocht worden in de veranderingen in de levensloop van de leerkrachten. De leeftijd van dertig jaar gaat vaak gepaard met een huwelijk of samenwonen, het starten van een eigen familie, het krijgen van kinderen. Deze ingrijpende veranderingen zullen waarschijnlijk een grote impact hebben op het beroepsleven van deze leerkrachten, hoewel leerkrachten reeds gebruik maken van de beschikbare verlofstelsels die werden uitgewerkt om deze overgang en werk-levenbalans te bevorderen. De vraag kan echter nog steeds gesteld worden of het leerkrachtenberoep, ondanks de reeds beschikbare hulpmiddelen, eventueel makkelijker gecombineerd kan worden met het uitgebreide gezinsleven van leerkrachten.

Early Career Teacher Attrition | ix

Het is ook primordiaal om als (onderwijs-)authoriteit te trachten om de juist gekwalificeerde leerkracht op de juiste plaats in te zetten. Uit de resultaten blijkt dat (om het risico op vervroegde uitstroom te beperken) het ook belangrijk is om het onderwijsniveau waar de nieuwe leerkracht tewerkgesteld wordt zo goed mogelijk te laten aansluiten op het onderwijsdiploma. Zo zouden leerkrachten die een specifieke lerarenopleiding (SLO) gevolgd hebben best ingezet worden in hoger secundair onderwijs (derde graad van het secundair onderwijs) om zo hun academische kennis en kwaliteiten zo goed mogelijk te benutten. Anders is de kans zeer groot dat deze personen snel zullen uitstromen omdat in andere beroepen hun kwaliteiten beter benut kunnen worden. Desalniettemin dient hierbij steeds rekening gehouden te worden met de kwaliteiten en competenties als leerkracht. Deze vaardigheden bepalen de kwaliteit van de leerkracht als lesgever van de nieuwe generaties, de welke niet steeds congruent zijn aan expertisedomein en algemene academische kennis.

Het dient opgemerkt te worden dat vroegtijdige uitstroom van leerkrachten niet steeds als dusdanig negatief hoeft beschouwd te worden. De jobmobiliteit zou beschouwd kunnen worden als een kenmerk van een efficiënte(re) arbeidsmarkt, aangezien de mobiliteit erin kan voorzien om de juiste persoon met de juiste competenties de juiste positie in de arbeidsmarkt kan bekleden. Indien pas-afgestudeerde leerkrachten vlak na instroom in het beroep tot het besef of de ervaring komen dat zij niet ‘gemaakt zijn om leerkracht te worden/zijn/blijven’, lijkt vroegtijdige uitstroom uit het beroep een logisch gevolg (e.g., Kip Viscusi, 1980). Het besef dat de persoon en het beroep niet met elkaar ‘fitten’ kan een verscheidenheid aan oorzaken hebben, zoals mismatch tussen theorie en praktijk van het beroep, hoge onzekerheid met betrekking tot pedagogische vaardigheden, gebrek aan collegialiteit en administratieve ondersteuning of lage jobtevredenheid in het beroep. De kans is groot dat als deze ontevreden personen toch vasthouden aan het leerkrachtenberoep, zij waarschijnlijk minder gelukkig zullen zijn in hun job en mogelijk zelfs ondermaats gaan presteren als leerkracht, wat waarschijnlijk nog negatievere gevolgen met zich meebrengt dan wanneer deze persoon vroeg uitstroomt.

Een laatste belangrijk resultaat met een koppeling naar het beleid betreft het vastbenoemingssysteem. Het is treffend dat wanneer er leerkrachtentekorten verwacht worden, althans op het secundaire onderwijsniveau, er nog steeds een meerderheid aan leerkrachten werkt op deeltijdse aanstellingen of vaak het ene interim-contract aan het andere rijgt, zelfs na enkele jaren als leerkracht gewerkt te hebben. Uit het onderzoek blijkt immers dat deeltijds werk en een grotere proportie aan interim-opdrachten de kans op vervroegd uitstromen aanzienlijk vergroot. Het belang van het personeelsbeleid binnen de onderwijssector betreft het selecteren en behouden van de beste leerkrachten. Aangezien de vaste benoeming voorlopig voornamelijk gebaseerd is op het gegeven anciënniteit, zonder in grondige mate de geschiktheid en de resultaten van de leerkracht op de werkvloer in rekening te brengen, en bovendien ook ongelimiteerd is in duurtijd, maakt dat jonge leerkrachten vaak stuiten op een systeem waar geen plaats lijkt voor hen, waardoor zij waarschijnlijk zeer snel zullen uitstromen uit het onderwijs.

Introduction

Providing high quality education for the next generations is an important objective in a Learning Economy. The capability of providing such qualitative education depends heavily on the strength and size of the teaching corps. UNESCO states that teacher education, recruitment, retention and working conditions are among their top priorities (UNESCO, 2014). In Belgium, a (growing) shortage of teachers is attributed to lacking recruitment into teacher education, scanty job entrance of newly qualified teachers and ample attrition of teachers (Johnson, Berg, & Donaldson, 2005; Rots, Aelterman, Devos, & Vlerick, 2010). The teacher shortages vary by geographical regions (or countries), but also by specialty field (Kersaint, Lewis, Potter, & Meisels, 2007). The shortage may in time become more severe in bottleneck-subjects such as mathematics, sciences, technology and (foreign) languages (European Commission, EACEA, & Eurydice, 2012). Huyge et al. (2009) identify the major policy challenge as the need for some breath of fresh air for schools, by attracting young, proficient and motivated newly qualified teachers, and the retention of high potentials and motivated professionals. A lot of attention is paid to the quality of teacher training and the recruitment of entrants into higher education into the teacher training programs, in order to optimize the proficiency and numeric magnitude of newly qualified teachers potentially entering the teaching profession. The suggestions of Huyge et al. (2009) consist of the urge to tailor a new suit of attractiveness, balance, proficiency and expertise to the teaching profession and the necessity to get rid of the self-depriving image caused by the suing culture, which currently seems to haunt the teaching profession. Lindqvist, Nordänger and Carlsson (2014) identify that the most common measures to overcome potential (future) shortages of teachers are focused on increasing recruitment into the teaching profession. However, building on the results of Ingersoll (2007), Lindqvist et al. (2014) highlight that a more efficient strategy might consist of intensifying the efforts in retention and support of the currently active teaching corps. Metaphorically speaking; “it is better to patch the holes in the bucket before trying to fill it up” (Lindqvist et al., 2014: p.95).

With respect to the entrance into the teaching profession, a recent study by Tierens and Smet (2015) indicates that on average 30% of the newly qualified teachers in Flanders did not enter the teaching profession after obtaining a teacher diploma in higher education (excluding adult education teaching programs). Similar figures were found for the whole of Belgium (Struyven & Vanthournout, 2014) and the Netherlands (Bruinsma & Jansen, 2010). Tierens and Smet (2015) also indicate quite a lot of variability in the entrance rates across educational levels. About 83.0% and 81.1% of newly qualified teachers, in nursery and primary education respectively, enter the teaching profession within the year. The entrance rates for teaching graduates on the level of secondary education are remarkably lower, where about 66.3% of graduates trained to become lower secondary education teachers and only 51.3% of graduates effectively become higher secondary education teachers within one year after graduating higher education.

Reflecting on the quality of the renewing teacher corps, no significant differences with respect to academic ability were found between the newly qualified teachers who did and did not enter the teaching profession (Tierens & Smet, 2015). This might indicate a missed opportunity to attract equally proficient potential teachers into the profession. In combination with the sizable reorientation rates (i.e., newly qualified teachers who do not enter the teaching profession after graduation), it is deemed even more important to retain the most able early career teachers in the teaching profession.

Early Career Teacher Attrition | 2

The observation of high turnover rates of teachers proves to be a persistent issue of concern for the authorities, which are ought to ensure provision of a qualitative education for all. As Goldhaber and Cowan (2014: p.450) state: “the longevity of teacher careers should be of interest to policymakers given that teacher attrition has both financial and academic consequences for districts and students”. The (financial) costs include the direct costs of recruitment and hiring of replacement teachers as well as the indirects costs of training, orientation and professional development (Goldhaber & Cowan, 2014). The academic consequences are linked to both teacher effectiveness and student achievement. Due to the replacement of more experienced teachers on the job with novices, the average teacher quality of the full teacher corps may decline. In line with Ronfeldt, Loeb and Wyckoff (2013), teacher turnover is disruptive to instructional programs and the development of a collaborative teacher network within a school. In the end, these consequences are highly likely to negatively affect student development and attainment (Rinke, 2008) and even may cause a loss of morale of those teachers who stay (Macdonald, 1999). On the other side of the same coin, teacher attrition is not necessarily bad to the core. Murnane (1984) indicated that the least effective teachers are most likely to attrite after a few years of teaching. This selective attrition does not comply with the hypothesis that the whole pattern of teacher turnover has a detrimental effect on the quality of the teaching corps. As the selective attrition was found to occur during the first years on the job (Murnane, 1984), only the most effective teachers will be retained, which increases the average quality of the teaching corps, and the (unneccesary) accumulation of large amounts of indirect costs after attrition is avoided.

Even though turnover is high for the teaching profession as a whole, it especially seems to affect both teachers in the early stages of their professional teaching career and the most experienced teachers reaching retirement ages (Grissmer & Kirby, 1997). Macdonald (1999) observed that the majority of teachers tend to leave the teaching profession before reaching the legal retirement age. The attrition rates were consistently found to follow a U-shaped curve (Borman & Dowling, 2008), where attrition occurs primarily during the early and late career stages.

Attrition rates were found to vary substantially across countries, often regardless of differences in their educational systems. Recent studies report attrition rates of early career teachers ranging between 10% and 50% during the first five years in the teaching profession (Hughes, 2012; Rinke, 2008; Struyven & Vanthournout, 2014). The lowest attrition rates were found in Scandinavian countries in Europe (e.g., Norway, Finland and Sweden) (Lindqvist et al., 2014; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2011) and the highest rates in the UK and the United States. In Flanders, attrition rates vary around 16% (Struyven & Vanthournout, 2014). A recent report by the Flemish Department of Education and Training (2013) shows that respectively 12%, 14% and 22% of early career nursery, primary and secondary school teachers quit the teaching profession. Struyven and Vanthournout (2014) postulate that these lower attrition rates may be explained by the current government policy attempting to improve the perception of the teaching profession, making it a more attractive career alternative where emancipation, autonomy and professionalism are highly valued. A second explanation may be that the combination of an upcoming teacher shortage and times of economic crisis induces the perception of the teaching profession granting a higher degree of job security (Struyven & Vanthournout, 2014). However, Vandenberghe (2000) nuances that, in Belgium, non-tenured teachers are always the first to be asked to leave and can even be pushed out by senior colleagues. This is due to the educational system’s premise, as in most Western countries, to base access to tenure on seniority. This causes the ‘last-in, first-out’ rule to prevail, resulting in higher attrition rates and lower job certainty/security among early career teachers.

Ingersoll (2001) even framed the teacher profession as a ‘revolving door’ occupation, characterized by “relatively large flows in, through, and out of schools in recent years, only partly accounted for by student enrollment increases or teacher retirements” (Ingersoll, 2001: p.514). Rinke (2008) intuitively links the ‘revolving door’-phenomenon to the observation that the current generation of teachers has numerous job opportunities available to them (Johnson & Birkeland, 2003). This generational characteristic might contribute to the increase in early career teacher attrition, whereas the new generation of teachers quickly gets tired of the teaching profession and/or uses the teaching profession as an intermediate ‘stepping-stone’-career alternative. Heyns (1988) noted that about 33% of the teachers who quit teaching (i.e., about 54% after 5 years) eventually returned to the teaching profession, which suggests that ‘taking breaks from teaching’ is not uncommon practice either. A comparison of teacher attrition rates with job change rates in other professions shows similarities in magnitude and temporality, suggesting that it is erroneous to attribute high early career attrition to the teaching profession alone (Harris & Adams, 2007; Kersaint et al., 2007; Lindqvist et al., 2014). Teacher turnover is often used as an umbrella term for teachers moving within or leaving from the teaching profession (Lindqvist et al., 2014). Thus, recent studies differentiate in the definition and consecutive operationalization of turnover and attrition (Borman & Dowling, 2008). There are several types of turnover which need to be reflected upon (Boe, Bobbitt, Cook, Whitener, & Weber, 1997; Rinke, 2008). A first type of turnover is denoted as teacher mobility, which are teachers who transfer from one teaching assignment to another teaching assignment. This migration may occur both within the same district or school community, which is denoted as reassignment, and between districts or school communities, denoted as migration (Hanushek, Kain, & Rivkin, 2004). Even though teacher mobility does not affect the aggregate supply of teachers, the direct recruitment and hiring costs are still incurred. The causes of mobility may both be voluntary, such as starting to teach in a school closer to the place of residence, and involuntary, for example due to a lack of vacant teaching hours at one school which may be substituted with available teaching hours at another school (within the same school community). A second type of turnover is teacher exit attrition, which consists of teachers who really stop their teaching careers and, thus, quit the teaching profession. Again a distinction can be made based on the causes of attrition (Struyven & Vanthournout, 2014). Involuntary attrition may be driven by natural causes (e.g., retirement, maternal leave, incapacitating illness or even death), which is denoted as wastage, or policy-related causes (e.g., school closure, forced-retirement or even dismissal), which is denoted as lay-off (Singer & Willett, 1988). The involuntary causes are often external to the teacher, except for dismissals due to insufficient performances at the teaching profession. Voluntary attrition is more often regarded as a rational decision of the teacher him- or herself. It reflects the loss of motivation or drive to continue being active as a teacher in favor of more attractive opportunities outside the teaching profession.

The responsibility for the provision of a proficient and large enough teacher corps lies primarily within the fold of the government. Since the government invests great sums of money into the education, recruitment, induction and development of the teacher corps, they also have the most to lose when a teacher quits the teaching profession in the early career stages already. Obviously, there are many (professional) life cycle factors that the government cannot influence. However, it is always important to know what characteristics of teachers and their professional careers are related to teacher retention (Adams, 1996), in order to adjust and focus policies. In the remainder of this report, an overview will be given on the most important characteristics related to teacher attrition. The aim and focus of this research will be elicited and the most important results will be linked to existing scientific research. Lastly, some interesting extensions and directions for further research will be explained.

Chapter 1. Determinants of Teacher Attrition

1.1 Definition of Early Career Teacher Attrition

In scientific research, a multitude of definitions and operationalizations of teacher turnover have been used (Borman & Dowling, 2008). The interconnectedness of all aspects of teacher turnover, such as retention, attrition and migration, results into a hard-to-define and/or operationalize focus of scientific research and its interpretability and relevance to policy makers.

This study will focus on exit attrition, based on the definition of Ingersoll (2001: p.503): “those who leave the occupation of teaching altogether”. These teachers decide to quit their teaching career semi-definitely, meaning that they will probably not return to the teaching profession on the short term. The teachers who quit the teaching profession were identified as ‘attrited’ at the moment where all current teaching assignments ended and no further teaching assigments were started before the end of the available observations in the data (i.e., end of school year 2014-2015)3. Since exit attrition

implies a net loss in the size of the current teacher corps, in addition to the highest direct and indirect (financial) costs to the schools and government among all aspects of teacher turnover, we tend to believe that policy-relevant information is most relevant to “patch the holes in the bucket” (Lindqvist et al., 2014: p.95).

In this study, exit attrition was defined separately on each teaching level (i.e., separating nursery school, primary school and secondary school teaching). Teachers teaching simultaneously and/or consecutively in multiple teaching levels (i.e., nursery, primary and secondary) were not taken into account in order to facilitate further identification of the (exit) attrition decision. The ‘event’ of the exit attrition decision becomes confounded when teachers might be ‘lost to one teaching level’, while not being ‘lost to the teaching profession’ as a whole, especially since dynamics in teaching assignments across multiple teaching levels might occur quite frequently. It is still informative and useful to examine those people lost to a specific teaching level, which informs and focusses educational policy reforms towards each teaching level.

Struyven and Vanthournout (2014) noted that in scientific research a certain degree of consensus is met that attrition rates reach a turning point after a period of five years. After these five years in the profession, attrition numbers tend to decrease steadily (Grissmer & Kirby, 1997; Struyven & Vanthournout, 2014). In contrast to the recent study of Struyven and Vanthournout, where exit attrition up until five years after graduation was being examined, our research is aimed at exit attrition during the early career stages (i.e., about five years in the teaching profession). The main rationale for this definition is to mitigate the impact frictional unemployment may have on the observation of the attrition decision within the time frame of the study. Since there is a substantial degree of non-entrance of newly qualified teachers within one year after graduation (Tierens & Smet, 2015), this impact is likely to have a considerable confounding impact on the results.

3 This operationalization of exit attrition, therefore, neglects the temporary breaks in the teaching profession. It is implicitly

assumed that when teachers spend their ‘unemployed time’ looking for new teaching assignments, which is realized when starting a new teaching assignment. This type of process should not be regarded as exit attrition.

Early Career Teacher Attrition | 6

1.2 Determinants of Early Career Teacher Attrition

The determinants of early career teacher attrition can be categorized into multiple levels. Rinke (2008) noted that both the individual level of analysis and the contextual level of analysis are important predictors for attrition/retention decisions. This has been confirmed in multiple studies such as Boe et al. (1997), Vandenberghe (2000), Omenn Strunk and Robinson (2006), Kersaint et al. (2007) and Hughes (2012). Omenn Strunk and Robinson (2006) identify the individual level (i.e., teacher characteristics), the school level (i.e., school attributes and district traits) and the geographical level (i.e., the larger state context). These levels are comparable to the levels proposed in the study by Tierens and Smet (2015) on entrance into the teaching profession.

1.2.1 Individual level of analysis

Rinke (2008) clarifies that the individual level of analysis often retrospectively analyses demographic (e.g., gender, age, race, socioeconomic status) and personal (e.g., education level and academic ability) characteristics as predictors to retention/attrition “over and above explaining the process by which these decisions are made” (Rinke, 2008: p.3). The most important characteristics, as discussed in the scientific literature, will be discussed below.

Gender – Several studies incorporated the gender of the teacher as a predictor for attrition. However,

the findings on the direct impact of gender on retention/attrition are quite inconsistent (Guarino, Santibanez, & Daley, 2006; Omenn Strunk & Robinson, 2006; Rinke, 2008). Some studies report higher attrition rates for males than for females (Heyns, 1988; Ingersoll, 2001), even though the meta-analysis by Borman and Dowling (2008) suggests that the inverse conclusion has been found more often. Rees (1991) has found more or less similar results, until after marriage, when female teachers seem to quit the profession at a faster pace. Murnane, Singer and Willett (1988) also tested the interaction between gender and age, finding that females attrite faster after age thirty. These findings suggest that women may be more likely to quit the teaching profession when they start rearing their own children (Murnane & Olsen, 1990). This fits quite well with the view proposed by Rinke (2008), who argues that teacher retention should be linked to professional lives and life stages, which are time-varying.

Age/Experience – The link between age and retention/attrition is one of the most consistent findings

in scientific studies. The relation between age and attrition is found to be U-shaped (Boe et al., 1997; Borman & Dowling, 2008; Guarino et al., 2006; Rinke, 2008), implying that attrition rates are higher during the early career stages and when nearing retirement ages. Integrating the findings with respect to gender and age, Boe et al. (1997) recommended that school authorities should focus on hiring older, more experienced teachers who have dependent children of at least five years old, which implies focusing on teachers beyond their early life cycle changes (referring primarily to changes in marital status and rearing children (Boe et al., 1997; Borman & Dowling, 2008)) and early career explorations. Firstly, with respect to the early life cycle changes, Borman and Dowling (2008) found consistent evidence that teachers starting their teaching careers at 31 or older were less likely to leave the teaching profession compared to their colleagues starting to teach at a younger age. Secondly, with respect to the early career explorations, Omenn Strunk (2006) mention the potential importance of the ‘probationary period’. In their interpretation, the probationary period lasts about two or three years, until a teacher is eligible for a tenure position. Vandenberghe (2000) already stated that tenure in Belgium is primarily based on seniority, resulting in a ‘last-in, first-out’ attrition process of teachers

which alludes to the uncertainty of newly qualified teachers during the early career stages. This may result in high transfer and attrition rates during the early career changes, as was found by Boe et al. (1997).

Ethnicity/Race – Ethnicity appears to be another important predictor of teacher attrition (Rinke, 2008).

Most studies find that minority teachers are least likely to attrite from the teaching profession (see e.g., Adams, 1996; Borman & Dowling, 2008; Imazeki, 2005; Ingersoll, 2001). Omenn Strunk and Robinson (2006) put these results in a broader perspective by investigating the effect of a match between the teacher’s ethnic background and the racial composition of the student-body within the schools where they are teaching. In summary, it has been found that non-minority teachers are more likely to attrite from the teaching profession and even more so in schools with high proportions of minority students (Imazeki, 2005; Omenn Strunk & Robinson, 2006).

Education/Certification – Several researchers have attempted to create proxy variables to measure

teacher quality when standardized tests scores are missing from the data, as is very often the case. It is quite important to ensure that the teaching corps is proficient enough and, thus, governments and other authorities strive to recruit and retain the highest quality teachers into the teaching profession. Podgursky, Monroe and Watson (2004), however, found that the most academically able teachers tend to leave the teaching profession. However, it should be noted that it isn’t always the case that the most academically able teachers are the most proficient at ‘teaching’. Therefore, researchers often use experience (discussed above) or certification route as a proxy. However, results are often inconclusive. It can be argued that multi-graduate teachers experience higher switching costs, which results in a lower attrition probability, but also faces many (and possibly more attractive) alternative career options, which may result in a higher attrition probability (Adams, 1996; Imazeki, 2005; Omenn Strunk & Robinson, 2006). The likelihood of the presence of more attractive career opportunities is also related to the subject specialty of (secondary education) teachers (Boe et al., 1997; Ingersoll, 2001; Murnane & Olsen, 1990). Subject specialists in exact and natural sciences, mathematics (Guarino et al., 2006; Murnane & Olsen, 1990) and even special-needs education teachers (Ingersoll, 2001) are more likely to attrite from the teaching profession, unless the nonpecuniary benefits are set disproportionally high to retain these teachers (Omenn Strunk & Robinson, 2006).

1.2.2 Contextual level of analysis

1.2.2.1 Teaching Professional Environment

Since it may be debatable whether the workload or the type of teaching assignment is at the individual level of analysis or should better be categorized as a professional context-oriented variable, we categorize this perspective as a separate level of determinants. The determinants are interpreted as the workload and complexity of the specific actual assignment(s) experienced by the individual, without a one-to-one linkage with the school in which the individual teacher works.

Employment Status – The employment status has not often been taken into account as a potential

predictor of (early) career attrition before the study of Boe et al. (1997). A full-time employment opportunity can be regarded as more attractive compared to a part-time (incomplete) teaching assignment, both because the remuneration as a full-time equivalent and the eligibility requirements

Early Career Teacher Attrition | 8

for obtaining a tenure position. Vandenberghe (2000) found that full-time employment reduces the attrition rate dramatically.

Teaching Level – The educational level at which a teacher teaches is often accounted for by contrasting

nursery, primary and secondary education. However, Boe et al. (1997) did not find any significant differences across these teaching levels. Nonetheless, because Tierens and Smet (2015) found significant differences in entrance rates into the teaching profession with respect to the teaching level, it is still interesting to examine possible differences in attrition rates. The rationale of the presence of alternative career options is an attractive and plausible rationale to expect differences across the teaching levels, especially for secondary education. In addition, at the secondary education level, a distinction can be made with respect to general, technical and vocational (and artistic) secondary education. It can be argued that both the achievement levels of the student body and the exploitation of the teachers’ subject specific knowledge/abilities differ across these teaching levels. This might influence the satisfaction and feelings of belonging of a teacher, which influences the attrition decision.

Salary – An extensive part of scientific research has been awarded to the review of compensation

policies and their effects on retention/attrition (Imazeki, 2005; Ingersoll, 2001; Murnane & Olsen, 1990; Rinke, 2008). It is one of the strongest workplace variables in order to predict attrition (Boe et al., 1997). All studies tend to find a positive impact of increasing salaries on the retention of teachers. However, since the remuneration of teachers is set by Flemish authorities/government (i.e., Ministry of Education) using uniform seniority-based salary scales, the schools cannot one-sidedly decide to differentiate on remuneration of the teachers.

Complexity and Dispersion – The teaching profession is characterized by a substantial complexity and

uncertainty. Clandinin et al. (2015) refer to the likelihood of getting jobs, where employment opportunities often seem quite sparse. Newly qualified teachers, while desiring continuity of employment as a teacher, are often perceived as willing to do anything to enter the profession and secure their job. As a consequence, newly qualified teachers often resign themselves to substitute teaching and less desirable positions, such as assignments outside their area of expertise, across a wide variety of classes and grade levels and/or even geographically distant from home (Clandinin et al., 2015). It should be noted that substitute teaching positions often entail a lot of job uncertainty (Correa, Martínez-Arbelaiz, & Aberasturi-Apraiz, 2015) and “hopping from one school to the next leaves a trace of insecurity in performance” (Correa et al., 2015: p.71). However, Vandenberghe (2000) examined the influence of the number of schools on attrition from the teaching profession, indicating that working in multiple schools reduces the risk of attrition. It should be noted, however, that these results may only hold when teachers simultaneously, rather than consecutively, work in multiple schools.

1.2.2.2 School Environment

Working Conditions – The working conditions of teachers within a school have been found to predict

retention/attrition quite well. Hanushek et al. (2004) state that, as was firstly proposed by Antos and Rosen (1975), teachers might be willing to sacrifice a portion of their salaries in exchange for better working conditions. Firstly, several studies control for the impact of school size, class size and student-staff-ratio (Boe et al., 1997; Borman & Dowling, 2008; Rinke, 2008) as well as school type/sector (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Guarino et al., 2006; Vandenberghe, 2000). School culture and school leadership also contribute positively to the probability of staying in the teaching profession (Rinke, 2008). These descriptors of the school culture and agreeableness of the professional working

environment is often related to support (Clandinin et al., 2015). Mentoring support of starting teachers, often taking the form of initial in(tro)duction and continuous support by more experienced colleagues within the school, has been found to be critical for early career teachers to stay in the teaching profession (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Clandinin et al., 2015; Guarino et al., 2006; Odell & Ferraro, 1992; Rinke, 2008; Smith & Ingersoll, 2004). Administrative support by the school leadership and the provision of adequate autonomy for teachers has also been found to positively influence retention (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Guarino et al., 2006; Ingersoll, 2001). Johnson et al. (2014) highlight that lack of induction or mentoring causes early career teachers to gain experiences by ‘trial and error’, leaving them in a ‘sink or swim’-situation where many teachers succumb and leave the teaching profession. Lack of support may be perceived as deskilling and demotivates professional enthusiasm and innovativeness (Johnson et al., 2014). These demotivating feelings often result from a mismatch between the innovativeness and enthusiastic novel teaching ideas by newly qualified teachers and the old-timers’ stagnation and normalized practices (Correa et al., 2015).

Student-body Composition – Far more often, the student population at the school has been found to

exert an important influence on the retention/attrition decisions of teachers (Rinke, 2008). The student-body composition with respect to ethnicity and socioeconomic status has received the most attention. It has been found that high proportions of minority students increase the probability of quitting the teaching profession (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Guarino et al., 2006; Omenn Strunk & Robinson, 2006). As has been noted above, several studies put this observation into a different perspective, whereas primarily the ‘discrepant teachers’ attrite at a faster pace (Imazeki, 2005; Omenn Strunk & Robinson, 2006). Teaching in schools with high proportions of student with a low socioeconomic status, which is often measured by income and eligibility to free lunch, increases the probability of attrition (Hanushek et al., 2004; Ingersoll, 2001; Stinebrickner, 1998). It should be noted, however, that the socioeconomic status is often attributed to and correlated with a minority status (Omenn Strunk & Robinson, 2006). The average student achievement within the school population was also found to influence teacher retention/attrition. Low student achievement scores might start to demotivate teachers, harm their teacher self-efficacy or even make them feel as if their capacities are undervalued or underutilized. This may increase the probability of quitting the teaching profession (Omenn Strunk & Robinson, 2006). However, the effect of student achievement on teacher attrition may be driven by an endogeneity process. Since teachers attrite at a faster pace from schools with low achieving students, these students are more likely to be confronted with instabilities of education and volatilities in the new and unexperienced teacher corps, which harms student achievement. In addition, this tendency causes a negative spiralic cycle, matching lower quality teachers with the neediest children (Omenn Strunk & Robinson, 2006).

1.2.2.3 Geographical Environment

Urbanity – There are mixed research findings with respect to the influence the schools’ environment

may have on teacher turnover. The urbanity of the school’s location has been primarily found to positively relate to high attrition rates (Guarino et al., 2006; Rees, 1991). However, Ingersoll (2001) found the inverse relation, whereas Omenn Strunk and Robinson (2006) and Imazeki (2005) did not find any significant influence at all. Urban schools are often related to high concentrations of poor, minority and low-performing students (Boyd, Lankford, Loeb, & Wyckoff, 2005), which likely results, based on the literature, in hard-to-staff schools. Vandenberghe (2000) used dummy variables to account for the school location to account for the unobserved socioeconomic context of the school.

Early Career Teacher Attrition | 10

Labor Market Opportunities – As has been argued above, the choices to enter the teaching profession

and the retention within the teaching profession are influenced by alternative labor market opportunities. Vandenberghe (2000) controlled for the general state of the external labor market, as a proxy of the probability of being confronted with (an ample amount of) alternative career options, using the district/province unemployment rate. No significant results have been found by Imazeki (2005) and Vandenberghe (2000). At the other side of the same coin, the tightness of the (internal) teaching labor market should be taken into account as well. The tighter this market, reflected by a large unemployment rate of qualified teachers, the harder it will become for young teachers to remain active in the teaching profession (Vandenberghe, 2000). However, there is still a lack of empirical results on this (Vandenberghe, 2000).

Distance – Boyd et al. (2005) examined the relation of differential access to employment with

residential segregation/spatial mismatch for teacher labor markets, finding that teaching labor markets are ‘local’ and often geographically small. They use the distance, as a straight line, from the teacher’s hometown to the school and find that teachers prefer their workplace to be “very close to their hometowns and in regions that are similar to those where they grew up” (Boyd et al., 2005: p.127) or live. Therefore, it is important to take (approximations of) the commuting distance into account in research on retention/attrition.

Chapter 2. Data & Methodology

2.1 Data

The data used in this report are subsets of recently linked administrative data provided by the Flemish Ministry of Education. The linked databases consist of rich data on educational administration of students (in higher education) and teachers in Flanders. A subset of the database containing newly qualified/ graduated teachers in regular higher education (i.e., university colleges and universities; thus, excluding adult education graduates), containing 31 961 individuals4 who obtained a teaching

degree between academic year 2007-2008 and 2012-2013, was linked to a subset of the teacher administration database, which contained data on 34 106 individual teachers that obtained a teaching assignment between 2005-2006 and 2014-2015. The Ministry of Education centrally gathers, checks, combines, processes and stores all these data on teaching assignments of all teachers submitted by their respective school’s administration5. The schools are implicitly obliged to report the employment

of all teachers within their schools in order to receive the financial means to pay their salaries, which is centrally governed and distributed by the educational authorities.

The linkage between these databases, yielding 26 707 matching individuals, enabled the selection of newly qualified teachers from higher education who did enter the teaching profession between school years 2008-2009 and 2012-2013 (retaining 21 851 individuals), teaching in either ordinary and/or special-needs nursery, primary and secondary education, respectively and exclusively6 (retaining

12 914 individuals). In the sample, data were obtained from 1441 nursery education teachers, 3613 primary education teachers and 7860 secondary education teachers. All these early career teachers were traced throughout their teaching careers from the time of starting their teaching careers up to the end of school year 2014-20157 (resulting in administrative ‘right censoring’ of the data). After this

timepoint, we do not observe the teachers anymore. We are only able/ allowed to state that they were still active in the teaching profession on the endpoint of our study.

The use of this detailed administrative database ensures that the data is rather clean, complete and exact. Detailed information was obtained on most determinants of teaching attrition on the individual level; such as gender, starting age, nationality (as a crude proxy to ethnicity/race), education and certification. These data were cross-checked and completed using the database on higher education enrollments and graduation (see footnote 4). Information on the contextual levels of analysis were restricted to the level of the teachers’ professional environments, reflecting on employment status (and working hours), teaching level, and complexity and dispersion of the teaching assignments (i.e.,

4 This dataset was previously used in the study by Tierens, H., & Smet, M. 2015. Determinants of Starting a Teaching Career:

A Multilevel Analysis. Leuven: Steunpunt SSL, rapport nr. SSL/2015.16/3.1.. Determinants of Starting a Teaching Career: A Multilevel Analysis. Leuven: Steunpunt SSL, report nr. SSL/2015.16/3.1.

5 The WebEDISON-tool has been designed and supported by AgODi to facilitate these administrative requirements. For

more information, we refer to the following websites (in Dutch): http://onderwijs.vlaanderen.be/nl/aanwerving-en-indiensttreding and http://onderwijs.vlaanderen.be/nl/een-indiensttreding-melden-aan-het-werkstation .

6 Teachers teaching simultaneously and/or consecutively in multiple teaching levels (i.e., nursery, primary and secondary)

were omitted from the sample in order to facilitate further identification of the (exit) attrition decision.

7 This period corresponds to the last timepoint where data accuracy and data completeness could be assured by the Flemish

Early Career Teacher Attrition | 12

measured by the number of simultaneous teaching assignments and the number of schools in which an individual is (simultaneously) teaching). Because the different teaching levels are somewhat different in structure, we will analyze these levels separately in the remainder of this report.

The incorporation of the school environment and the geographical context of the schools were not yet included in the analysis. This is due to the complexity of the extension of cross-classified, multilevel multiple membership models to our empirical setting (i.e., cross-classified, multiple membership random effects/frailty models for survival analysis). This will be an extension the authors are currently working on. This extension will probably provide more insights into the school environments with which early career teachers are confronted, without neglecting school mobility during the early career stages. The multiple membership setting refers to teachers working in multiple schools at the same time, which requires the random school effects to contribute to the risk of attrition through a weighted summation of random effect predictions. The cross-classification aspect of the model alludes to the school mobility and, thus, the time-dependency of the (multiple) membership to the school (set). Further research on the estimation of such models in an educational context is forthcoming in the (near) future.

2.2 Descriptives

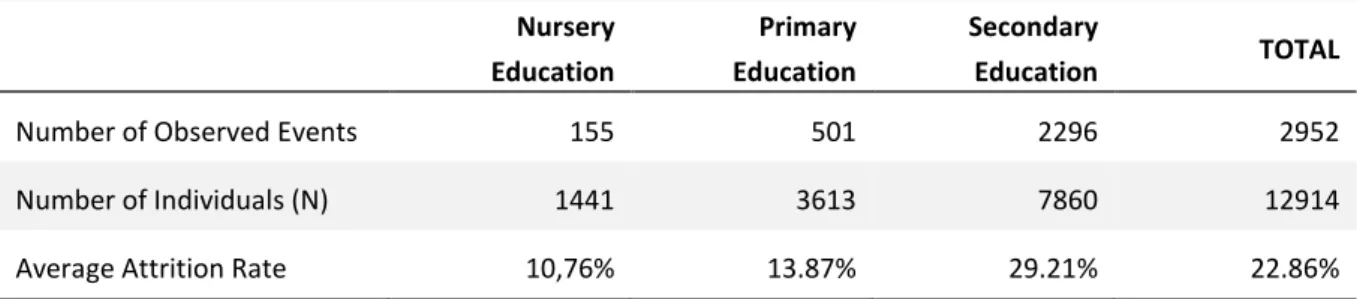

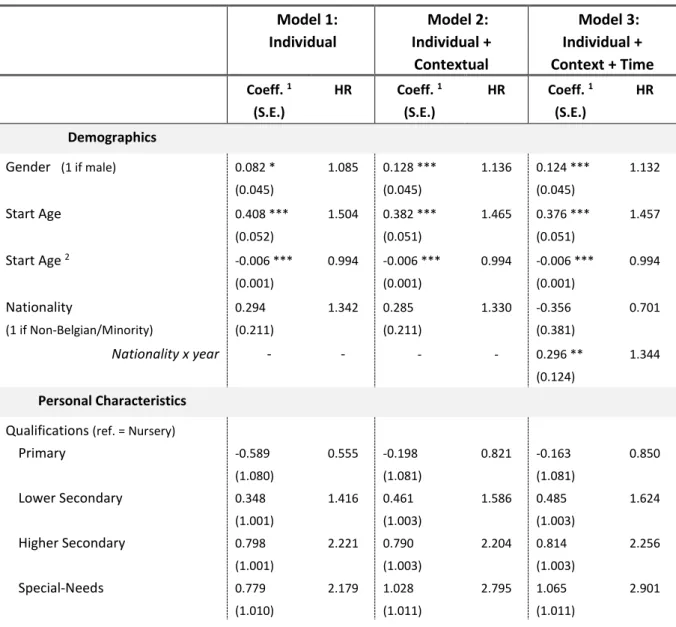

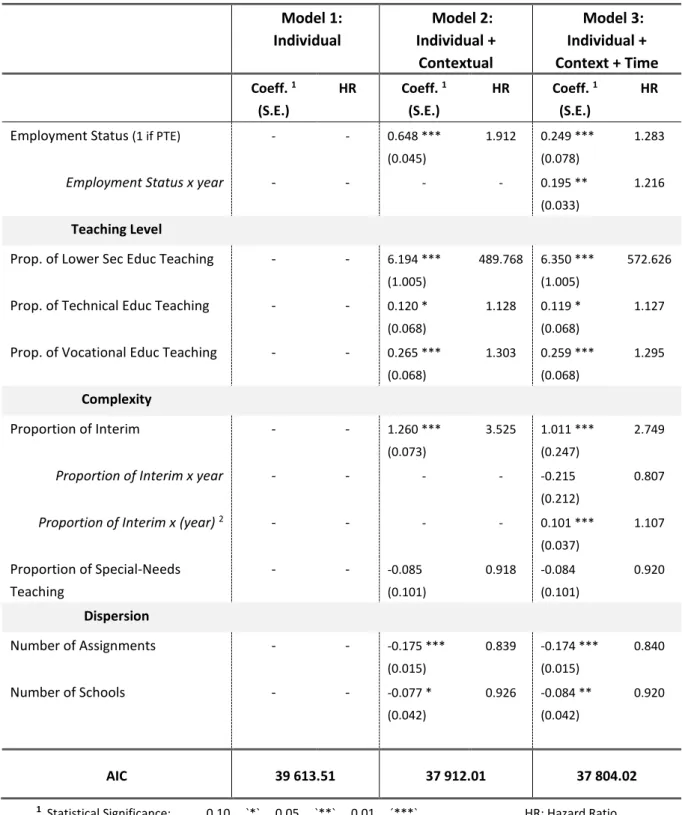

The average exit attrition rates in Flanders were found to vary around 16% according to Struyven and Vanthournout (2014). In our sample, the (naïve) average attrition rate, disregarding the variability across teaching levels, amount to 22.86% (see Table 1). This amount is somewhat larger than reported in previous studies, which may be due to the fact that we did not terminate the follow-up of early career teachers at exactly five years in the teaching profession. The Flemish Department of Education and Training (2013) reported attrition rates varying around 12%, 14% and 22% in nursery, primary and secondary education respectively. Our sample resonates the reported attrition rates for nursery and primary education quite well, showing attrition rates of respectively 10.8% and 13.9%. However, a higher attrition rate has been found for early career teachers in secondary education, where 29.2% of early career teachers quit the teaching profession after a few years. This last difference may be caused by the definition and operationalization of exit attrition in this study and the available data. The Flemish Department of Education and Training used a larger database containing also some information on newly qualified teachers who obtained a teaching diploma through adult education.

Table 1: Early Career Attrition Rates

Nursery Education Primary Education Secondary Education TOTAL

Number of Observed Events 155 501 2296 2952

Number of Individuals (N) 1441 3613 7860 12914

Average Attrition Rate 10,76% 13.87% 29.21% 22.86%

The naïve estimates of the overall attrition rates, computed as the ratio of the number of observed events by the total number of individuals, do not take the right-censoring in the data into account and therefore result in a more optimistic point of view on the attrition rates over time. In order to get a more nuanced picture of the early career attrition rates, the estimated survival plots can be studied

(see Figure 1, Figure 2 & Figure 3). These plots are based on the non-parametric Kaplan-Meier estimates of the survival probabilities. The non-parametric nature of these estimates has the advantage of being fully data-driven and, thus, the estimates reflect the observed data as close as possible. It should be noted that in the tables in Figures 1-3, the population at risk consists of the all observed individuals at each timepoint. This means that at each timepoint, not only the number of individuals who experienced the event disappear from the population at risk, but also the number of censored individuals (i.e., ‘observations at the end of the observation period’).

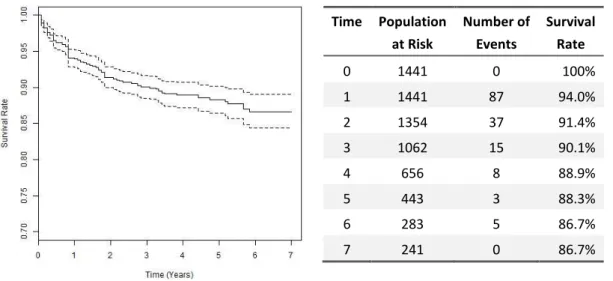

Early career attrition for teachers in nursery education (see Figure 1) seems largest in the very early years, showing the sharpest declines in survival rates in the early years. The survival curve levels out after three years in the teaching profession. After five years in the teaching profession, about 11.7% of the teachers attrite from the teaching profession and 13.3% of the early career nursery teachers in the sample quit the teaching profession at the end of our study (i.e., after seven years in the teaching profession). These rates do not differ much from the attrition rates found in the scientific literature and in the reports from the Flemish Department of Education and Training (2013).

Figure 1: Survival Curve of Early Career Teachers in Nursery Education

Time Population at Risk Number of Events Survival Rate 0 1441 0 100% 1 1441 87 94.0% 2 1354 37 91.4% 3 1062 15 90.1% 4 656 8 88.9% 5 443 3 88.3% 6 283 5 86.7% 7 241 0 86.7%

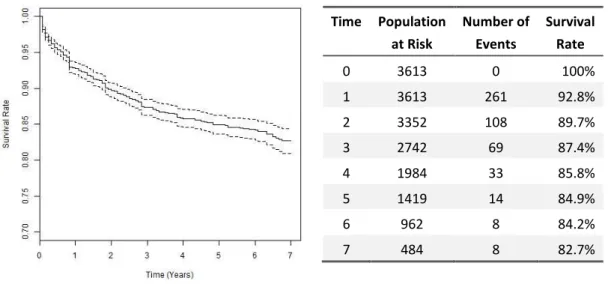

The survival curve for early career teachers in primary education, depicted in Figure 2, shows a more continuous decline in the survival probabilities, without levelling out after a few years. The attrition rates are in general always a little higher for primary school teachers when compared to nursery school teachers. After five years in the profession, 15.1% of early career teachers in primary education have quit the teaching profession. At the end of our study, 17.3% of the early career teachers in our sample have left the profession. These rates are a little higher than the rates reported by the Flemish Department of Education and Training (2013).

Early Career Teacher Attrition | 14

Figure 2: Survival Curve of Early Career Teachers in Primary Education

Time Population at Risk Number of Events Survival Rate 0 3613 0 100% 1 3613 261 92.8% 2 3352 108 89.7% 3 2742 69 87.4% 4 1984 33 85.8% 5 1419 14 84.9% 6 962 8 84.2% 7 484 8 82.7%

The early career attrition of teachers in secondary education (see Figure 3) is a lot larger than in nursery and/or primary education. The survival curve shows a very steep decline in the first year, where already 14.9% of early career teachers quit the teaching profession. The following years the attrition rates become smaller, showing a smoother but still steady decline of the survival curve. Only 68.7% of the early career teachers are still in the teaching profession after five years, which is equivalent to an attrition rate of 31.3%. After the five year ‘turning point’, the survival curve seems to flatten out. Hence, at the end of the study, about 33.6% of the early career teachers have quit the teaching profession.

Figure 3: Survival Curve of Early Career Teachers in Secondary Education

Time Population at Risk Number of Events Survival Rate 0 7860 0 100% 1 7860 1170 85.1% 2 6690 475 79.0% 3 5552 338 74.0% 4 4178 180 70.6% 5 3017 77 68.7% 6 2068 44 67.2% 7 1101 12 66.4%

As has been previously stated, the early career teacher attrition will be examined and explained based on both individual-level covariates and contextual characteristics of the professional environment of the individual. The linked databases provided quite rich and detailed information for each of these levels of analysis.

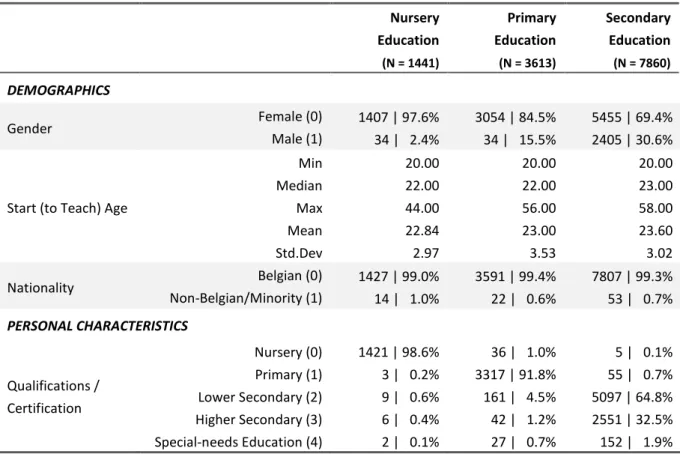

The descriptive statistics of the individual covariates are reported in Table 2. With respect to the demographic covariates, the early career teachers in our sample seem to be young –on average 23 years old when they start to teach, which is a little after regular graduation age from teacher training– and have the Belgian nationality. There are a few older people who decided to pursue a teaching career at later stages in life, possibly after the termination of a previous career outside of education. The feminization of the teaching profession seems to be a consistent and persistent trend, which we find to be present in our sample as well. The gender balance shows to be most unequal in nursery education, where the vast majority is female (more than 97%). The gender balance becomes only marginally better in primary education (15% of male teachers) and secondary education (30% of male teachers). With respect to qualifications of the early career teachers, it can be concluded that there is a good match between the teaching levels to which a teaching diploma grants access and the teaching level where the teacher is employed. At least 90% of early career teachers teach at the respective teaching level for which their teaching certificate was meant. This variable was measured as an adapted generalization of the ISCED-classification8 (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2012). The

first three levels of the qualifications covariate (i.e., nursery (0), primary (1) and lower secondary (2)) correspond to teacher training through a three-year professional bachelor program, whereas the fourth level (i.e., higher secondary (3)) certification can only be obtained through a specific teacher training program at universities after having obtained an academic (master’s) degree. The special-needs education-level corresponds to teachers having obtained a teacher certification at an ‘advanced level’ (such as an advanced bachelor (-after-bachelor) program).

8 ISCED stands for ‘International Standard Classification of Education’. The first four levels, ranging from 0 up to 3, follow

Early Career Teacher Attrition | 16

Table 2: Descriptives of the Individual-level Covariates

Nursery Education (N = 1441) Primary Education (N = 3613) Secondary Education (N = 7860) DEMOGRAPHICS Gender Female (0) Male (1) 1407 | 97.6% 34 | 2.4% 3054 | 84.5% 34 | 15.5% 5455 | 69.4% 2405 | 30.6%

Start (to Teach) Age

Min Median Max Mean Std.Dev 20.00 22.00 44.00 22.84 2.97 20.00 22.00 56.00 23.00 3.53 20.00 23.00 58.00 23.60 3.02 Nationality Belgian (0) Non-Belgian/Minority (1) 1427 | 99.0% 14 | 1.0% 3591 | 99.4% 22 | 0.6% 7807 | 99.3% 53 | 0.7% PERSONAL CHARACTERISTICS Qualifications / Certification Nursery (0) Primary (1) Lower Secondary (2) Higher Secondary (3) Special-needs Education (4) 1421 | 98.6% 3 | 0.2% 9 | 0.6% 6 | 0.4% 2 | 0.1% 36 | 1.0% 3317 | 91.8% 161 | 4.5% 42 | 1.2% 27 | 0.7% 5 | 0.1% 55 | 0.7% 5097 | 64.8% 2551 | 32.5% 152 | 1.9%

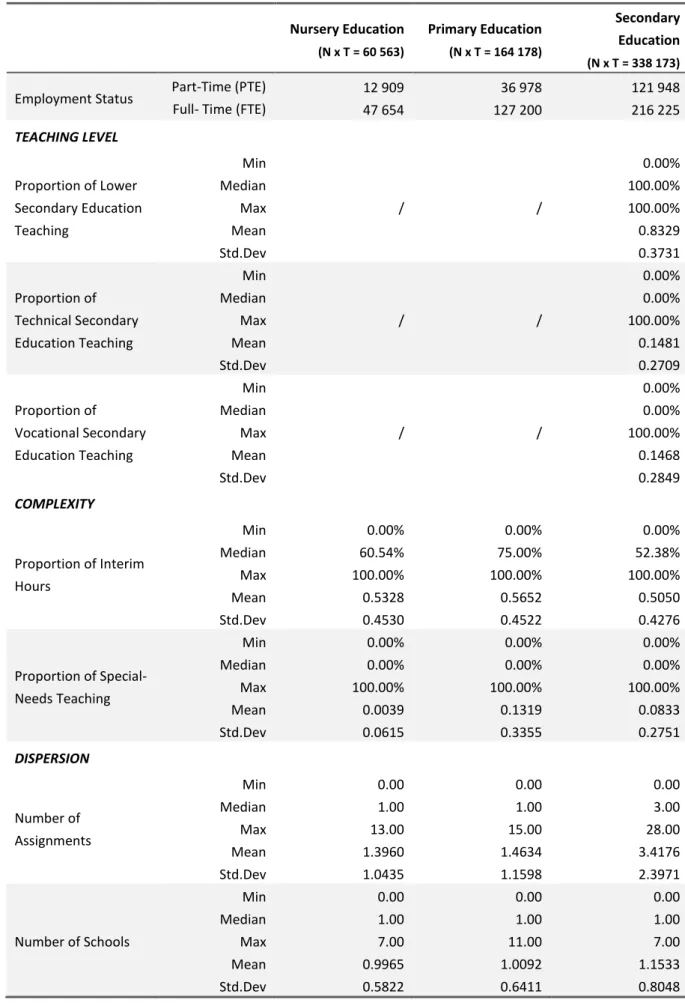

The descriptive statistics of the contextual level of analysis, consisting of the professional environment of the early career teachers, can be found in Table 3. Note that the sample size in this table corresponds to the number of records (i.e., data lines) in the person-period structured dataset. Thus, each record reflects a month in which an individual teacher is active in the teaching profession. The total sample size, as such, equals the aggregated number of teaching months performed by the total early career teaching corps in the sample.

Early career teachers seem to be working as full-time equivalents quite often. We operationalized working as a full-time equivalent as a binary variable, indicating whether the cumulative working hours over all teaching assignments within one month exceeded the threshold of 20 hours (a week). In both nursery and primary education, early career teachers tend to work about one fifth of their time as a part-time equivalent. However, in secondary education, early career teachers work as a part-time equivalent 36% of their time, nearly twice as much as nursery or primary education teachers.

The teaching level covariates are only relevant for secondary school teachers, since secondary education can be split up further. Firstly, one can distinguish between lower secondary education (grades 1-4 of six) and higher secondary education (grades 5-6(/7)). Only the descriptives for the proportion of lower secondary education teaching are shown, because the complementarity of the proportion of higher secondary education teaching (i.e., the sum of both proportions equals 100%). In regular situations, only teachers who have obtained a master diploma are allowed to teach in higher secondary education, whereas teaching positions in lower secondary education are filled by teaching graduates having obtained a teaching diploma through professional bachelor programs. On average, about 83.3% of the total time, early career teachers teach in lower secondary education. The disproportionate proportion of lower secondary school teaching (i.e., one would expect the ratio to be

closer to 2/3 = 66.7%) might be due to seniority- and/or experience-based distribution of teaching assignments within the school among its staff. Secondly, (the last four grades of) secondary education can be split up into four ‘tracks’: general, technical, vocational and artistic secondary education. Since the general and artistic track are the most similar in terms of educational content, they are used as a homogeneous reference category. Their complements consist of technical secondary education, where on average 14.8% of total teaching time is being apportioned, and vocational secondary education, where early career teaches spend another 14.7% of their teaching time. The median proportions of teaching in either technical and/or vocational secondary education suggest that more than half of the early career teachers do exclusively teach in general and/or artistic secondary education.

The remainder of Table 3 shows the descriptives of covariates related to the complexity and the dispersion of the teaching profession. With respect to the complexity of the teaching profession, especially for early career teachers, the proportion of hours worked in interim assignments (i.e., often substitute teaching) has been computed. On average, about 50% to 56% of the aggregated teaching hours are performed in interim assignments. These assignments might put considerable constraints on the feeling of continuity of employment in the teaching profession. Since interim assignments can be quite easily prematurely terminated, this leaves the early career teacher with uncertainty about further employment as a teacher and continuous insecurity during employment through interim contracts. A second aspect of the complexity of the teaching profession is the proportion of hours taught to special-needs students. In this report, the assigned hours corresponding to teaching assignments in special-needs education (in Dutch: “bijzonder onderwijs”) are considered to be ‘special-needs teaching hours’. Even though a teacher, regularly, requires an additional (advanced-level) certificate to teach in special-needs schools, these teaching duties are considered to be more demanding than teaching non-needs students. In nursery education, only 0.4% of aggregated teaching time is attributed to teaching in special-needs schools. In primary education and secondary education, respectively, this proportion amounts to 13.2% and 8.3% of teaching time spent at teaching in special-needs schools.

The teaching career of early career teachers may, especially during the early career stages, be somewhat dispersed and unstable. Firstly, the number of simultaneous teaching assignments in each month is recorded. In nursery education, the number of assignments per month varies between zero9

and thirteen simultaneous assignments. The average number of assignments was 1.39. This is close to the observed number of simultaneous teaching assignments in primary education, ranging between zero and fifteen, with an average of 1.46. In secondary education, the number of simultaneous assignments ranges between 0 and 28, with an average of 3.42 assignments. This is more than double of primary and secondary education. This observation might be due to the multiple grades in which a teacher can be active and a multitude of courses a teacher is able to teach. Nevertheless, an early career teacher in secondary education seems to be expected to apply for each vacancy in order to be assigned some teaching hours (eventually building up to a full-time teaching position), which can be regarded as a complex and burdensome process. Secondly, teachers may be simultaneously teaching in multiple schools. The number of schools ranges in all teaching levels between 0 and 7 (11 in primary education), with the average and median number of schools around 1. This mitigates the potential geographical dispersion of the teachers’ careers across multiple schools.

9 This might happen when the teacher was not assigned as a teacher in the respective month, which can be both because

Early Career Teacher Attrition | 18

Table 3: Descriptives of the Contextual-level Covariates – Professional Environment

Nursery Education (N x T = 60 563) Primary Education (N x T = 164 178) Secondary Education (N x T = 338 173) Employment Status Part-Time (PTE)

Full- Time (FTE)

12 909 47 654 36 978 127 200 121 948 216 225 TEACHING LEVEL Proportion of Lower Secondary Education Teaching Min Median Max Mean Std.Dev / / 0.00% 100.00% 100.00% 0.8329 0.3731 Proportion of Technical Secondary Education Teaching Min Median Max Mean Std.Dev / / 0.00% 0.00% 100.00% 0.1481 0.2709 Proportion of Vocational Secondary Education Teaching Min Median Max Mean Std.Dev / / 0.00% 0.00% 100.00% 0.1468 0.2849 COMPLEXITY Proportion of Interim Hours Min Median Max Mean Std.Dev 0.00% 60.54% 100.00% 0.5328 0.4530 0.00% 75.00% 100.00% 0.5652 0.4522 0.00% 52.38% 100.00% 0.5050 0.4276 Proportion of Special-Needs Teaching Min Median Max Mean Std.Dev 0.00% 0.00% 100.00% 0.0039 0.0615 0.00% 0.00% 100.00% 0.1319 0.3355 0.00% 0.00% 100.00% 0.0833 0.2751 DISPERSION Number of Assignments Min Median Max Mean Std.Dev 0.00 1.00 13.00 1.3960 1.0435 0.00 1.00 15.00 1.4634 1.1598 0.00 3.00 28.00 3.4176 2.3971 Number of Schools Min Median Max Mean Std.Dev 0.00 1.00 7.00 0.9965 0.5822 0.00 1.00 11.00 1.0092 0.6411 0.00 1.00 7.00 1.1533 0.8048