MASTER IN DE ERGOTHERAPEUTISCHE WETENSCHAP

Interuniversitaire master in samenwerking met: UGent, KU Leuven, UHasselt, UAntwerpen,

Vives, HoGent, Arteveldehogeschool, AP Hogeschool Antwerpen, HoWest, Odisee, PXL, Thomas More

Faculteit Geneeskunde en Gezondheidswetenschappen

Acoustics and challenging behaviour in dementia

Ine DECOUTEREMasterproef voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Master of science in de ergotherapeutische wetenschap

Promotor: prof. dr. Patricia De Vriendt Co-promotor: prof. dr. Dominique Van de Velde

MASTER IN DE ERGOTHERAPEUTISCHE WETENSCHAP

Interuniversitaire master in samenwerking met: UGent, KU Leuven, UHasselt, UAntwerpen,

Vives, HoGent, Arteveldehogeschool, AP Hogeschool Antwerpen, HoWest, Odisee, PXL, Thomas More

Faculteit Geneeskunde en Gezondheidswetenschappen

Acoustics and challenging behaviour in dementia

Ine DECOUTEREMasterproef voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Master of science in de ergotherapeutische wetenschap

Promotor: prof. dr. Patricia De Vriendt Co-promotor: prof. dr. Dominique Van de Velde

PREAMBLE: COVID-19

Due to the outbreak of COVID-19, the student was compelled to make changes in the method of the research. Five nursing homes were included in the study and gave their permission to collaborate in the research, resulting in the possibility to observe a total of 25 participants. As a result of the outbreak of the virus, the planned observations could not take place in the last nursing home and therefore only twenty participants were observed. Therefore, the thesis is completed on the basis of the data already available and the results are based on the observations of twenty participants. Consequently it was not possible to increase the sample if saturation was not achieved.

This preamble was drawn up in consultation between the student and the supervisor and approved by both.

ABSTRACT (NL)

Achtergrond: Dementie is een progressieve ziekte, gekenmerkt door cognitieve en functionele achteruitgang en komt vaak samen voor met een verandering in gedrag. ‘Uitdagend gedrag’ (UG) is een groep van gedragingen, reacties en symptomen als gevolg van dementie, die uitdagend kan zijn voor de (professionele) zorgverlener en kunnen uitgelokt worden door de omgeving. Het doel van het onderzoek is om de invloed van de akoestiek op UG bij personen met dementie (PmD) te onderzoeken.

Methode: Een etnografisch design werd gebruikt om het dagelijkse leven van PmD in een woonzorgcentrum te bestuderen met een specifieke focus op hoe mensen reageren op dagelijkse geluiden. Op basis van een doelgerichte, homogene steekproef werden twintig bewoners geïncludeerd in 4 WZC. Participatieve observaties (24/7) werden geanalyseerd op basis van een fenomenologisch-hermeneutische methode: een naïef begrip, een structurele analyse en een allesomvattend begrip.

Resultaten: Het ontstaan van UG lijkt af te hangen van de aan- of afwezigheid van een gevoel van veiligheid bij de PmD en lijkt te worden getriggerd door een overdaad aan auditieve prikkels of een gebrek eraan. De hoeveelheid prikkels die UG zal uitlokken, is zeer persoonlijk en kan afhankelijk zijn van verschillende factoren zoals de persoon zelf of het tijdstip van de dag. Daarnaast is de aard van de stimuli, gekend of ongekend, ook een bepalende factor voor het ontstaan en de voortgang van UG.

Conclusie: UG is een indirect gevolg van iets dat het welbevinden van de PmD bedreigt. Dit bedreigend gevoel kan zijn aanleiding vinden in de akoestische omgeving. De resultaten kunnen een belangrijke basis vormen voor het ontwikkelen van soundscapes, om zo de PmD een veilig gevoel te geven en UG te reduceren.

Sleutelwoorden: Akoestiek, Akoestische Prikkels, Akoestische Triggers, Dementie, Gedrags- en Psychologische Symptomen van Dementie, Geluidsomgeving, Uitdagend Gedrag

ABSTRACT (EN)

Background: Dementia is a progressive illness, characterized by cognitive and functional decline and often co-occurs with a change in behaviour (Azermai, 2015). ‘Challenging behaviour’ (CB) is a group of behaviours, reactions and symptoms due to dementia, which can be challenging for the (professional) caregiver. The aim of the study is to research the influence of the acoustics on CB in people with dementia (PwD).

Method: An ethnographic design was used to study the daily life of PwD in their nursing homes with a specific focus on how people react to normal day-to-day sounds. Based on a purposeful, homogeneous, group characteristics sampling, twenty residents were included in the sample. Empirical data were collected using 24/7 participatory observations. The collected data were analysed based on a phenomenological-hermeneutical method: a naïve understanding, a structural analysis and a comprehensive understanding.

Results: The onset of CB seems to depend on whether the resident feels safe or not and appears to be triggered by an excess or lack of stimuli. When and if there is an excess or shortage of stimuli is highly personal and can depend on various factors such as the person himself or the time of day. In addition, the nature of the stimuli, familiar or unknown, is also a determining factor for the onset and progression of CB.

Conclusion: CB is an indirect consequence of something that threatens the well-being of the PwD. This threatening feeling can find its cause in the acoustic environment. The results can form an important basis for the development of soundscapes, in order to make the PwD feel safe and reduce CB.

Keywords: Acoustics, Acoustical Triggers, Auditive Stimuli, Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD), Dementia, Challenging Behaviour (CB), Sound Environment

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction ... 1 Method... 3 Research design ... 3 Sampling ... 3 Ethical procedure ... 4 Data collection ... 4 Data analysis ... 5 Quality insurance ... 6 Results... 6 Naïve understanding ... 7 Structural analysis ... 8 Comprehensive understanding ...14 Discussion ...15Strenghts and limitations ...17

Recommendations work field...19

Conflict of interest ...20

References ...21

Appendices ... 1

PREFACE

Before you lies the thesis “Acoustics and challenging behaviour in dementia”. This study is part of a larger research project to apply tailored soundscapes in persons with Dementia (PwD) to decrease their level of challenging behaviour (CB). To be able to do so, a comprehensive understanding of how sounds impacts the PwD’s behaviour is necessary.

This thesis is a wonderful way to end two intensive but enlightening years and has been written to fulfil the graduation requirements of the Master of Occupational Science at Ghent University (UGent). I chose this particular subject to research because of my love for the care for the elderly and my deep interests in dementia.

I would have never succeeded this study without the help of important key figures. First and foremost, I want to thank my promoter Prof. dr. Patricia De Vriendt for the ongoing support and constructive feedback based on extensive experience in and knowledge of dementia and challenging behaviour. My co-promoter, Prof. dr. Dominique Van de Velde, should also be mentioned and thanked for the support with which he always steered me in the right direction. In addition I would like to thank Tara Vander Mynsbrugge, for guiding me in conducting the observations and in recording them.

At last I would like to thank my mother, my life partner and very close friends Annouk, Kaat, Hanne, Justien and Annelien, for the ongoing support they gave me while writing my thesis.

1

INTRODUCTION

Countries are constantly developing socio-economically which leads to a risen life expectancy, creating an increasingly ageing population (WHO, 2015). As the population ages, health issues become more complex, more chronic and multimorbidity becomes more common (WHO, 2018). The prevalence of chronic diseases, such as dementia, increases. The World Alzheimer report of Alzheimer’s Disease International states that in 2015 5.2% of the world's population aged 60 and over, which represents 46.8 million people, are living with dementia. In Central Europe, the number of people diagnosed with dementia corresponds with 4.6% of the population aged 60 and older (Prince et al., 2015) and 122,161 people were living with dementia in Flanders in 2015 (Steyaert, 2016).

Every 20 years, the number of people with dementia (PwD) almost doubles, meaning that by 2050, 131.5 million people worldwide will be living with dementia. The growth of the number of PwD is accompanied by an enormous impact on society and healthcare costs (Prince et al., 2015; Joling et al., 2015; Ricci, 2019; Takizawa et al., 2015). The global cost for the society is estimated on 818 billiard US dollars in 2015, an increase of 35.4% since 2010, and is predicted to be approximately 2 trillion US dollars by 2030 (Prince et al., 2015; Wimo et al., 2016).

Dementia is a progressive illness, characterized by cognitive and functional decline. This decline often co-occurs with a change in behaviour such as restlessness and aggression. In the literature, this behaviour is mainly referred to as behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) (Finkel, 2000; Azermai, 2015). However, the term ‘challenging behaviour’ (CB) is perhaps more correct to use as it is less stigmatizing. Challenging refers to the challenge for the informal and professional caregivers to deal with this behaviour while BPSD describes the behavioural symptoms from a more biomedical perspective.

CB represents a heterogeneous group of challenging behaviours, reactions and symptoms due to dementia. It is very frequent in PwD and more strongly present in individuals in a more severe stage of dementia (Benoit et al., 2005). Ninety percent of individuals with Alzheimer's exhibit at least one of these behaviours sooner or later and about one third experience serious problems (de Oliveira et al., 2015; Liperoti et al., 2008). Several studies have shown that most CB do not seem to occur isolated, they occur together in clusters (Petrovic et al., 2007). These clusters vary by time, severity, diagnosis and intervention. Van der Linde and collegues (2014) made a subdivision within CB consisting of four groups; (1) affective symptoms, including depression & fear; (2) psychosis; Including hallucinations & delusions; (3) hyperactivity, including irritability & aggression and (4) euphoria.

Overall, CB has several consequences in different domains. Previous studies have shown that CB significantly contribute to the overall cost of dementia care (Finkel 2000; Ricci,

2 2019). For PwD and their environment, CB is an important contributing factor for a poorer prognosis, a more rapid rate of cognitive decline, an increased number of hospitalization and visits to the urgent care, for early institutionalization in nursing homes (NH) and excessive disability (Finkel 2000; Aguero-Torres et al., 2001; Wergeland et al., 2015). Moreover, CB also has a major impact on the quality of life (QOL) of both the PwD and their environment as well as the health care provider (HCP) (Fauth and Gibbons, 2014; Feast et al., 2016; Hurt et al., 2008; Samus et al., 2005).

Currently there is no cure available for dementia. There are only treatments available that address the symptoms, such as CB (Ricci, 2019). Overall, dementia guidelines recommend first treating CB with non-pharmacological interventions. If it has been demonstrated that the non-pharmacological interventions produce little to no results, pharmacological interventions can be carried out (Cook et al., 2012). In practice however, the pharmacology is often the first choice of approach to treat CB (Azermai, 2015).The number of PwD using antipsychotics is estimated to be between 19% and 46% in European NH. Its use however is controversial because of the potential benefits being overshadowed by the potential harm (Liperoti et al., 2008). Although the effectiveness of antipsychotics has been investigated in several studies, there is little to no evidence of its effectiveness (Liperoti et al., 2008; Azermai, 2015). Moreover, the use of antipsychotics entails many risks. Potential adverse effects occur frequently and can be dangerous (O’Neil et al., 2011; Ervin et al., 2013; Azermai, 2015). The US Food and Drug Administration even warned about increased mortality risk associated with the use of antipsychotics in older PwD (cited in Liperoti et al., 2008; cited in Azermai, 2015).

Clear, consistent data that support the use of non-pharmacological treatment for CB is lacking (O’Neill et al., 2011; Azermai 2015). Many reviews report mixed results with little to no consistency of evidence to recommend or reject an intervention. A systematic review of Abraha et al. (2016) examined nineteen different non-pharmacological interventions to treat CB for PwD, including three studies that were environment-based interventions. One of these was the study of Whear et al. (2014) that examined the effect of music on the background during dinnertime. Whear et al. (2014) concluded that CB rose when music was played during dinnertime. The overall conclusion of the SR of Abraha et al. (2016) was that only two of them, music therapy and behavioural management techniques (BMT), were effective for reducing CB. Part of the BMT is functional analysis (FA), a behavioural intervention that requires the therapist to look for the underlying function, meaning or problem that is causing the person’s distressed behaviour (Cook et al., 2012). Dyer and colleagues (2018) stated that FA-based interventions should be the first choice.

Together with the growing evidence of non-pharmacological interventions, there is an increasing interest in adapting the environment, in specific, the sound environment, which is

3 already a topic in many investigations in various settings such as schools, restaurants and parks (Shield et al., 2018; To and Chung, 2015; Wilson et al., 2016). Brown et al. (2015) describe the role of sound in clinical environments and the damaging effects of sound, emphasizing on mental health care. Excess unwanted noise can be harmful to health and impede recovery (Brown et al., 2015). Sound as a part of the environment has an impact on people's behaviour and their QOL. Quiet and pleasant sounds promote health and nuisance noises limit health (Andriga and Lanser, 2013).

In healthcare, soundscapes – emphasizing the relationship of people to any sonic environment, whether natural, musical or synthesized – are increasingly used to reduce adverse consequences and improve positive effects (Truax, 1977). Soundscapes usually encompass different sounds that occur simultaneously or consequently (Axelsson et al., 2010). In fact, there are little to no studies on the effect of soundscapes on CB. Though it is not wrong to think that soundscapes might have a positive influence on the CB, since CB has a neurological basis which makes the PwD more vulnerable to environmental, physical and psychological factors (Benoit et al., 2005; Liperoti et al., 2008).

The aim of this research is to explore the factors that are on the onset and progression of CB in PWD living in NH. Based on this, later research can be used to develop a valid model for enhancing QOL and modifying behaviour in PwD in NH through soundscapes. The research question that is being formed is "What is the influence of acoustics on challenging behaviour in people with dementia?" .

METHOD

This thesis shall be drawn up on the basis of the instructions for authors of the International Psychogeriatrics (International Psychogeriatric Association, n.d.).

RESEARCH DESIGN

An Ethnographic design was used to study the daily life of PwD in their NH with a specific focus on how people react to normal day-to-day sounds in the NH. The daily lives will be studied by completely immersing in the context of the PwD. The PwD’s experiences regarding sounds will be observed, promoting a comprehensive understanding of their experiences and their behaviour.

SAMPLING

The NH were selected on the basis of convenience sampling (Portney and Watkins, 2014). The researcher contacted NHb y e-mail and asked if they want to cooperate in the research. The NH had to have a separate department for PwD, private rooms for the residents, a dining room, a sitting area and a cafeteria and the NH had to have a (para)medical and

4 nursing team as imposed by the Flemish government (Agentschap Zorg en Gezondheid, 2017). It was set out to include four NH and Within each NH, five PwD were selected on the basis of a purposeful, homogeneous, group characteristics sampling (Patton, 2015). These people were selected in consultation with the head of each NH. The inclusion criteria are: People living with dementia, which is assessed with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), living in a department for PwD in a NH for at least one year (Folstein et al., 1975; Kok and Verhey, 2002). They have to show CB, which was evaluated based on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q), an adjusted version of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI). This is a self-administered questionnaire that is being filled in by a caregiver of which the score represents a sum of individual symptom scores ranging from 0 to 36. (Kaufer et al., 2000). In addition they have to have a D or CD care dependency profile on the Katz-index scale Belgian version, which stands for having a diagnosis of dementia or having some characteristics linked to dementia such as disorientation (Katz et al., 1963). Palliative residents and/or residents who recently started a new medication plan that is still being tested were excluded. If it was determined that saturation was not achieved with this sample size the sample was expanded (Howitt, 2016).

ETHICAL PROCEDURE

The PwD’s legal representative, the managing director and the staff agreed with the study and gave their approval, by means of an informed consent (Appendix A). The family of the PwD were informed about the participatory researcher and the observations made. For the resident himself, the researcher was considered as one of the staff members. The PwD was not aware of a researcher present in the NH. The study is registered under the registration number B670 2019 41 367 – 2019 41 368 at the commission for Medical Ethics of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences at Ghent University and Ghent University Hospital. The data were collected in accordance with the GDPR legislation (General Data Protection Regulation).

DATA COLLECTION

Empirical data were collected using 24/7 participatory observations in the four selected NH. There was unilateral blinding, on the part of the subjects. Both residents and staff were explained that the study aims to map out what an average day in a residential care centre looks like to prevent people from behaving in a more desirable way (e.g. making less noise, speaking less loudly, being more attentive for environment ...). In each NH, the five purposively selected people were observed by the researcher during three different time slots of eight hours each. The time slots were from 7:00 AM to 3:00 PM, from 3:00 PM to 11:00 PM and from 11:00 PM to 7:00 AM. Through these three shifts, an observation of a full day (24 hours) was ultimately

5 performed within each NH. The focus of the observations were on the five key-participants, but also care providers and the residents around the included residents were observed.

The observations were held in the private room, the sitting room and the dining room during all activities of daily life; eating, washing, resting, sleeping, playing, watching TV ... and even seemingly doing nothing. A characteristic of the participating observation is that the researcher participated in the activities carried out. The researcher blended in as a member of the care team working in the department and assisted the team where possible. The researcher always kept focus on creating possibilities to observe and stayed close to one of the five included residents. The observations were written down out of sight of the key-participants, this is to avoid suspicion among the residents. The researcher described the situation and the environment, followed by the behaviour, the incident, the interaction ... and how they are responded to. During the writing, attention is paid to exclusively writing down literal, objective observations to stay as close as possible to the data. The field notes are reconstructed at the end of each observation shift into a detailed observation transcript. Each event was also time-stamped. A member check is carried out with employees or family present, whereby checks are made as to whether the observations are correct and whether they have other additional observations. In addition, the medication records are always placed next to the fieldnotes, so that it can be excluded that certain behaviour is due to possible medication. No use was made of audio or video recording.

DATA ANALYSIS

The collected data, in the form of a detailed observation transcript, will be involved in an iterative process and constant comparison of the transcripts (Taylor, 2017). The data analysis followed an phenomenological-hermeneutical method in three phases: a naïve understanding, a structural analysis and a comprehensive understanding.

In the first phase, a naïve understanding was formulated (Lindseth and Norberg, 2004). In the second phase, a structural analysis was conducted. First, the author divided the transcripts in ‘meaning units’ according to the events that occurred. Therefore the Antecedent-Behaviour-Consequence (ABC) model was used. Behaviour is determined by a specific antecedent, something that happens before a behaviour (Volicer and Hurley, 2003). The consequence of the behaviour is what happens afterwards. The consequence is not always visible or observable as it can be for instance a feeling, such as ‘feeling safe’. Each meaning unit, containing ABC was considered to be one of the units for analysis. When the transcript was divided into meaning units, some events seemed to not occur as a consequence of the sound environment. When the behaviour of the PwD follows an antecedent with e.g. clear visual stimuli, pain, touching or a conversation, the meaning unit is not included in the analysis.

6 The next step in the structural analysis was condensing the meaning units, i.e. the essence of each ‘meaning unit’ is expressed as briefly as possible (Lindseth and Norberg, 2004). Both the identification of the meaningful units and the condensation of these units were done by two independent researchers.

Via an iterative process, the condensed meaning units were cross-validated with the second researcher until consensus was reached. The condensed meaning units were examined on regarding similarities and differences. They were sorted and similar condensed meaning units were abstracted to form subthemes. The condensed meaning units and subthemes were constantly compared and discussed amongst the entire research team through which patterns could be identified showing the relation between sound and behaviour. The subthemes eventually were assembled into themes, which were then reflected on in relation to the naïve understanding. Note that these steps are presented here in a rather linear way but in reality these phases were characterized by going back and forth between them. Lastly, the themes and subthemes were reflected on in relation to the research question and the context of the study and reported in a final synthesis.

QUALITY INSURANCE

Several quality criteria are taken into account in the procedure (Portney and Watkins, 2014). The first author, who performed the participatory observations, was not employed on either of the study wards to decrease expert bias by being too familiar or too connected to the staff and the key-participants and to increase the trustworthiness of the data. The confirmability was reinforced by taking field notes and supplementing observations based on a member check at the care providers. To increase the credibility, two researchers condensed the meaningful units independently of each other and a peer-debriefing of the different steps throughout the analysis were performed. Transferability was increased by inclusion and exclusion criteria for the sample and a detailed description of the characteristics of the applied example. As a result, sufficient information is mentioned to be able to judge separately in other contexts if the results can be transferred to one's own context.

RESULTS

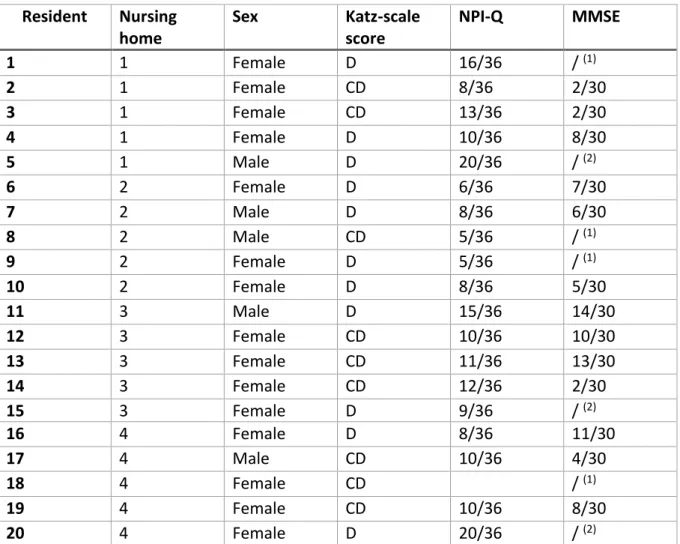

In total, twenty key-participants were included in the final sample, considering the in- and exclusion criteria, and observed during the 24-hours-observation. During the observations fieldnotes were written and a transcript was generated. In table 1 are the main characters displayed per resident, to present a description of the sample.

7

Table 1: Description sample

Resident

Nursing

home

Sex

Katz-scale

score

NPI-Q

MMSE

1

1

Female

D

16/36

/

(1)2

1

Female

CD

8/36

2/30

3

1

Female

CD

13/36

2/30

4

1

Female

D

10/36

8/30

5

1

Male

D

20/36

/

(2)6

2

Female

D

6/36

7/30

7

2

Male

D

8/36

6/30

8

2

Male

CD

5/36

/

(1)9

2

Female

D

5/36

/

(1)10

2

Female

D

8/36

5/30

11

3

Male

D

15/36

14/30

12

3

Female

CD

10/36

10/30

13

3

Female

CD

11/36

13/30

14

3

Female

CD

12/36

2/30

15

3

Female

D

9/36

/

(2)16

4

Female

D

8/36

11/30

17

4

Male

CD

10/36

4/30

18

4

Female

CD

/

(1)19

4

Female

CD

10/36

8/30

20

4

Female

D

20/36

/

(2)(1) not possible to take the test (2) refuses to take the test

NAÏVE UNDERSTANDING

The acoustical environment of the included NH was overall very similar. During the day, the living space was filled with the sound of a radio or a TV but the soundscapes were very monotonous. In addition, the hallways and bedrooms were very quiet. The PwD were resting or wandering around without meeting each other and as a result there was little to no speech sound. On the other hand, during breakfast-, lunch- and dinnertime, there was a lot of noise and the acoustic environment was very busy and heterogeneous. All the PwD were seated in one area and all the (professional) caregivers were also present in this room. The sound of voices, cutlery and crockery and plates being stacked or passed around dominated the acoustic environment. At night, the acoustic environment was silent. When the caregivers of the night shift pass by for check-ups, there was a brief burst of human noise and the sound of closing doors and rolling carts.

It has been observed that PwD cannot always interpret sound correctly. It seemed that they didn’t always understand what the meaning of the sound was, where the particular sound was coming from or why it was happening. It has been observed that PwD reacted to sound

8 but also to the absence of sound. It appeared that when PwD were overstimulated with auditory stimuli, they tended to leave the noisy space, to avoid the rumour and – probably - to feel save. When they couldn’t flee, it looked like they became nervous and angry. It also has been observed that when there are not enough auditory stimuli, PwD became scared. They tended to start wandering around or creating stimuli themselves by talking or making noises or manipulating objects.

STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS

The structural analysis resulted in 125 meaning units. In table 2, five meaning units are shown to illustrate the way the transcript was divided and structured and themes were formulated.

9

Table 2: Examples of units of the structural analysis

Meaning unit Condensation Subtheme Theme

Antecedent Behaviour Consequence

The caregiver goes to the wardrobe (which is against the outside wall of the bathroom). She opens the door of the wardrobe with a key (it makes a lot of noise). The doors are closed again, making a loud slamming noise. The room was completely silent, making the sound very noticeable.

Resident 1 yells, while standing in the bathroom: boo boo!

The caregiver yells back at her: “It’s okay, I am just messing around in the wardrobe.”

Yelling in response to a striking sound that is very noticeable in an completely silent space. Vocal reaction to sound that is not understood. Not under-standing the sound

Resident 14 sits at the table in the dining room. The food is scooped out. There's the clatter of cutlery. People (staff and volunteers) walk around in the room and provide everyone with a plate of food. There is talk at the tables.

Resident 14 gets up and walks out of the dining area towards the hallway with rooms and the sitting area.

The caregiver asks her: "Wouldn't it be better to stay seated? Your food will be served in a minute.”

Getting up and leaving the dining room which is very crowded with voices and clatter of cutlery. Moving away from a noisy and crowded space. Too much stimuli

Resident 17 sits in the dining room/living at the table. There are twelve other residents in the room, four aid workers and a family member. The family member talks to the resident at the table next to resident 17. The care workers stand behind him talking. Sometimes the cat meows. You can hear spoons sounding against porcelain.

Resident 17 eats soup and looks over his shoulder at where he's talking.

He starts talking to the residents at his table. He talks to himself but directs it to others at the table.

Looking over the shoulder in the direction of the voice and then talking to oneself and people at the table in a room with a lot of ambient noise. Looking in the direction of the sound. After determining he's safe, resume activity. Identifying the sound

10 In the living room the TV and radio

are on at the same time. The robocat is making a purring sound on the table.

Resident 16 talks in the cat's ear and says, "So sweet, you're so sweet."

/ Calmly and sweet

talking to the robocat.

Calmly talking

No CB

The hallway is quiet. The sound of the dining area is occasionally audible in the distance. On some parts of the corridor it is not audible at all.

She begins to walk down the corridor (these are endless, arranged in a square). She talks to herself and walks down the corridor.

She keeps walking around and talking to herself.

Wandering around in a very quiet hallway and talking to oneself. Wandering around because of under-stimulation Not enough stimuli

11

Theme 1: Acoustics can prevent the onset of CB

Out of the observations and the corresponding analysis it could be concluded that residents didn’t show any CB when they experienced the right amount and right type of stimuli. There were numerous observations endorsing this analysis such as a situation where a certain resident was standing in a room and was calm. As soon as people walked in the room, busy talking, the resident left the room. But right before he actually left the room the people stopped talking, and the resident froze, turned around, went to a chair and sat down.

Although, it became clear that the right amount was highly personal and precarious. The right amount is not the same for every resident. In the same acoustic environment, some residents were calm while for other residents it was too busy leading to the onset of CB. Furthermore, the right amount changed constantly for each individual resident depending on, for example, the time of day or the mood the person was in. CB were triggered by a variety of contextual aspects and the residents’ behaviour changed any moment.

When the sound was a familiar sound, the reaction of the resident appeared to be more predictable, triggering less CB. Sounds that were not that common or familiar, evoked CB.

Seven residents are sitting around the table in the kitchen. … The residents drink coffee. The doorbell rings; it sounds throughout the building. Resident 7 gets up and

walks towards the corridor, …

Further analysis showed that the residents endured more complex sound environments when they were around loved ones, i.e. people that the resident trusts. The resident seemed to feel safe and showed no CB.

Resident 7 is seated with another resident, whom he considers to be his wife. ... Another resident comes along talking and humming … The caregiver walks by with

rattling keys … The footsteps of the caregiver are clearly audible. A TV and music can be heard in the distance. Resident 7 talks inside mouth to the resident with

which he is holding hands and is calm.

Theme 2: The absence of acoustical triggers causes anxiousness and mistrust.

Wandering, talking or manipulating objects can create a feeling of safety.

However, it happened more often that the amount and type of stimuli was not optimal, meaning that it didn’t apply perfectly to the individual. Overall, it seemed that residents tried to add stimuli in order to eliminate the feeling of being unsafe by either creating a sound, searching for a sound or presenting themselves with other stimuli such as visual or sensory stimuli.

12 The sound on the ward could be very quiet or monotonous during the day. This was the case for the moment after breakfast, when people had finished eating and the tables were cleared and wiped, up until the moment later on, when the tables were set for lunch and the residents were brought into the dining room. This also applied to the moment after lunch until dinner and the moment after dinner until bedtime. At these moments many residents rested, but not all of them. Some of them were sitting in the living room or in a sitting area.

It appeared that residents had an overall feeling of being unsafe and showed fear or mistrust if insufficient stimuli were present. Different forms of behaviour of the resident were observed, seemingly to create a sense of safety. Some of them were humming, singing or talking to themselves or to people passing by, not necessarily having a proper conversation. It seemed that these people were talking or making a sound to break the silence.

“The hallway is empty and quiet. The night shift cart is being driven around, the wheels run on the floor tiles. The caregivers whisper … enters the room as quietly as

possible. Resident 5 sits on his chair in his room. He has his eyes open and is chatting to himself.”

It was also observed that some residents started manipulating object like sofas, garbage bins, gloveboxes or closed doors that they found in the area or encountered on the way. They moved the objects, tried to open them or played or tinkered with them. By doing so, it could be the goal to create more stimuli.

"It's night, all the residents are in bed and it's very quiet in the ward. Resident 7 is standing in the kitchen, turning the knobs on the radio. The radio is off. ... He keeps

doing this for 20 minutes."

When the residents had nothing to do they started wandering around the ward. Some residents stepped towards the sound, possibly to look for auditory stimuli. Other residents continued to wander around, walking up and down the corridors or going back and forth between the sitting room, the dining room, his own room, etc.

“The television's on in the dining room. … The TV is very loud. … Resident 1 comes out of the silent corridor through the door and walks halfway in the room while watching the TV, ... She stays halfway the room and continues watching the TV from

a distance.”

For residents that were unable to walk or move around independently, they continuously tried to leave the room by for example, continuously trying to get out of the wheelchair.

13

Theme 3: Complex sound environments cause an uncomfortable or angry feeling,

which can be solved by behaviour of the resident that is set out to avoid or reduce the

noise.

On the other end of the spectrum, when there is a lot of different noises in the area the resident could feel overstimulated. This mainly occurred during eating times when there were many people in the room who were talking to each other. Moreover, there was a lot of noise from cutlery and crockery and there were staff members walking around making extra noises such as footsteps, rolling with a food cart, etc. But it could also happen during the day when larger groups of people were talking together while, for example, the sound of the TV or radio was present in the background. When the acoustics were loud and heterogeneous, it was observed to create an uncomfortable feeling, a feeling of suspicion or it made the resident restless or angry.

Resident 2 is still in the dining room, back to back with resident 1. Resident 1 talks a lot … loud and well audible. In the meantime classical music … not dominant. … she

looks angry over her shoulder several times when resident 1 talks loud.

The resident tried eliminating the overdose of sound. Some residents would leave the room and go look for a place that was more quiet. Those who were wandering around on the ward tended to avoid the overly crowded and loud rooms by turning around or by passing the door and walking towards other spaces.

Resident 14 sits at the table in the dining room. The food is scooped out. There's the clatter of cutlery. People (staff and volunteers) walk around … People are talking at

the tables. Resident 14 gets up and walks out of the dining area …

But not all people for whom the space was too noisy, would leave the room. Some of them would stay angry and frustrated not knowing how to act to become less agitated. Other people were physically not able to move away from the source of the noise. They kept trying to e.g. stand up out the wheelchair or try to eliminate the sound by e.g. putting their fingers in their ears.

After dinner resident 8 sits at the table in his wheelchair, fixated with a belt around the waist. There is a lot of talking … and there is singing. Resident 8 constantly tries

to stand up straight from his wheelchair. This doesn't work because of the fixation. After resident 14 has been taken out of the bath and dressed, the caretaker starts blow-drying the hair. Resident 14 sits on a chair and allows this but puts the fingers

14

Theme 4: PwD can misinterpret sounds and therefore do not react in a way that is

expected.

It was possible that residents heard a sound but didn’t understand the sound or were unsure whether they were safe. To make sure the sound didn’t accompany danger, residents looked up in the direction of the sound. They looked for affirmation that they were still safe and that the sound was no threat. Determining the cause of the sound and being able to conclude that there was no danger, could be enough for the resident to feel safe and pursue what they were doing before the sound was heard.

Resident 7 sits in the seats in the hallway with his eyes closed. It's very quiet on the ward. A laptop on the table makes a noise. Resident 7 looks up in the direction of the

laptop, then looks back in front of him and closes his eyes again.

Some residents didn’t have the reflex to look up in the direction of the sound to locate the source and determine whether they were still safe. If residents didn’t recognize the sound or didn’t understand it, they reacted in a way that was not expected in the situation. Common reactions from the residents were yelling in the direction of the sound, laughing with for instance the sound of broken glass or dancing to a ringing phone. Some residents shook their head or raised their eyebrows at a sound they didn’t comprehend.

Resident 10 gets up from the toilet. The caregiver flushes the toilet behind him without announcing it. Resident 10 reacts by saying: “Oh God, who was that?”.

When the caregiver would make a sound and didn’t announce this to the resident, the resident could scare. By telling what the resident could expect sound wise, the unsafe feeling could be prevented. When the resident did understand the sound and the expectation attached to it, it seemed that they could react in the way they were expected. E.g. going to the door when the bell rings, whispering when someone nearby is on the phone, …

All seven residents sit around the table in the kitchen. ... The doorbell rings, the sound is audible throughout the building. Resident 7 stands up and walks towards

the corridor.

COMPREHENSIVE UNDERSTANDING

In a comprehensive understanding, the subthemes and themes are reflected on in relation to the research question: "What is the influence of acoustics on challenging behaviour in people with dementia?".

15 The reaction of the PwD to the acoustical environment was very complex. The onset of CB seemed to depend on whether the resident felt safe ‘in the soundscape’ or not. When the PwD felt threatened, CB would occur. Different causes could be at the root of the feeling of unsafety and thereby generate CB. It appeared that CB was triggered by an excess or lack of stimuli. When and if there was an excess or shortage of stimuli was highly personal and could depend on various factors such as the person himself or the time of day. In addition, the nature of the stimuli, familiar or unknown, was also a determining factor for the onset and progression of CB. Familiar sounds, the amount of which is tuned to the capacity of the PwD, can reduce CB. On top of that, the presence of significant others could influence the reaction on the acoustical environment, possibly because being around significant others increased the feeling of being safe.

It could be concluded that the emergence and progression of CB is highly individual (relying on personality and typical characteristics of dementia) and depends on the interaction between personal and acoustical environmental factors.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine the influence of acoustics and acoustical triggers on CB. CB is seen an active attempt by the person to articulate an unmet need and is a very common problem in PwD (Krishnamoorthy and Anderson, 2011). It puts a burden on caregivers, reduce QOL and increase a risk of institutionalisation (Feast et al., 2016; Finkel, 2000; Wergeland et al., 2015). Therefore it is important to try to reduce CB as much as possible.

However, managing CB is not easy. The antipsychotic practice guideline in care homes formed recommendations concerning the use of antipsychotics as a treatment for CB. The recommendations are that they should never be used as a first-line approach. Non-pharmacological interventions should be tried first and if antipsychotics are used, it must be combined with non-pharmacological interventions (Liperoti et al., 2008; Azermai, 2015; Zuidema et al., 2015). In order to manage CB non-pharmacologically, it is important to understand the reason behind the behaviour (Cook et al., 2012; Gerritsen et al., 2019; Krishnamoorthy and Anderson, 2011). Much research has already been done into influencing factors that lead to CB. CB can be influenced by physical factors, psychological factors and communicational or social factors as well as environmental factors (Krishnamoorthy and Anderson, 2011; Tible, 2017).

Knowledge of the factors that lead to CB can create the opportunity to adapt those factors so they can prevent or reduce CB non-pharmacologically. A lot of non-pharmacological approaches to manage CB, such as physical exercise, animal-assisted therapy or touch

16 therapy, are already the subject of many researches (Abraha et al., 2016; de Oliveira et al., 2015). Nonetheless they are often very individually and time-consuming (Abraha et al., 2016). Therefore it can be interesting to look into the possibility of adapting the environment in order to positively influence CB.

In the literature, adapting the environment is already a topic of interests. Approaches such as light therapy or aromatherapy have been intensively researched (Abraha et al., 2016; de Oliveira et al., 2015). Sound is also a subject of examination. However, it seems that within sound, research is often about music therapy (Wang et al., 2018) or the addition of music to the environment (Chaudhury et al., 2013), while acoustics and soundscapes seem to be less studied. Although it gets increasing interests in the research field, within various target groups, such as secondary school pupils (Shield et al., 2018), people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities (van den Bosch; et al., 2016) or PwD (Devos et al., 2019).

The observations show that CB seems to be influenced by an excess or lack of auditory stimuli. Whether or not there is excess or lack of auditory stimuli however is very personal. It can vary between people but also within one person between different times of the day or even the state of mind they are in as well as the familiarity and recognition of the sound. CB seems to diminish if the amount of auditive stimuli can be adapted and if the PwD feels safe, which seems to be created by familiar sounds or sounds that are comprehensible as well as being around people they trust.

Possible explanations for these results are the ‘ecological equation’ of Kurt Lewin (cited in Lawton, 1977) and the ‘ecological model of aging’ of Lawton himself (1977). Lewin’s concept ‘ecological equation’ state that behaviour is the result of the person and the environment. These transactional models such as the Person-environment-fit-model (Law et al.,1996) and the Ecology of Human Performance framework (Turpin & Iwama, 2011) support this concept stating that the person cannot be seen separately from his or her environment, but there is a continuous interaction between the two. This is consistent with the finding that CB is a consequence of the person's environment. This corresponds with Gerritsen et al. (2019) their remark that CB is not a direct symptom of dementia, but rather an indirect consequence of something, possibly present in the environment. CB functions as a signal that well-being is threatened.

Besides ‘ecological equation’ to comprehend the interaction between person and environment, Lawton (1977) designed an ecological model of aging which displays that behaviour is a function of the competence or capacity of the individual and the environmental press of the situation. The environmental press corresponds to the demand the environment imposes on the individual and can be behaviour-activating to some individuals (Lawton, 1977). Adaptation to environmental stressors may be dependent on the individual’s level of

17 competence (Lawton, 1986). Various situations with various levels of press can have various behavioural outcomes for the person. This was also concluded from the observations. The capacity of the PwD can change during different moments during the day, where e.g. the PwD can show more CB in the evening and less CB in the morning, although the acoustic environment is similar. Krishnamoorthy and Anderson (2011) discuss ‘lack of stimulation’ to be a possible reason for wandering.Tible et al. (2017) also addresses an optimization of levels of stimulation, considering the capacity of each individual. The optimization of this level of stimulation is seen as an environmental characteristic that is related to lower levels of CB.

Krishnamoorthy and Anderson (2011) briefly describe that persistent noise can cause stress and annoyance. This seems to correspond to that e.g. PwD want to leave the room or become agitated while sitting at the dining table and eating their meal in a room filled with noises such as talking and cutlery on crockery. Krishnamoorthy and Anderson (2011) also state that a familiar space can reduce CB, which can be an explanation for the observation of reduced CB when being around familiar people. Recognizability and familiarity seems to create a safe feeling, making CB less present. Interestingly, they also discuss the use of simulated presence therapy, by which audio recording of significant others are used to create a feeling of family proximity, but evidence for this treatment approach is still lacking.

The results also showed that one of the residents was very calm when a robocat was placed in front of her. The robocat made cat noises and the resident talked to the robocat. Wang et al. (2018) describe similar findings in his systematic review, discussing the effect of a robot seal generating movement and sound on agitation and depression. Which was found to reduce it significantly.

STRENGHTS AND LIMITATIONS

This participatory observational study has some strengths. Firstly, the sample was very large. Twenty PwD were observed in four different NH and at different times throughout the day, resulting in observations of an entire 24 hours. In total, there were 96 hours of observations. This ensured that the collected data is very extensive and varied. Secondly, It is very innovative to conduct research on the influence of the acoustic environment on CB in order to create a basis for the development of a soundscape, for sound and acoustics have only been studied to a limited extent. Qualitative research was in addition the best way to bring these insights to the surface and to form a clear understanding of the influences. Thirdly, the analysis was very structured using the ABC-method to structure the separated meaning units to then condense the meaning units to eventually form subthemes and themes. Based on peer debriefing among the different researchers, the condensed meaning units, subthemes and themes were cross-validated, increasing the credibility. Because of the clear description of the

18 residents included in the sample, it is easier to judge if the results apply for the own sample and transferability is increased.

Of course, this study has also some limitations. The 24 hours observations were split up into 3 different timeslots, which were performed on different days. Because of this it could be that interesting data was missed or links between behaviour and earlier events could be overlooked. It is however not practically possible to be present for 24 consecutive hours. No video was recorded during the observations which made it not possible to go back to recordings to confirm the fieldnotes or to complete incomplete fieldnotes. Due to the dynamic nature of the observations it would be difficult to record the observations, even more so, it would not be ethical to record PwD's CB. The researcher did do a member check with care providers who worked during the shift, when the field notes were not complete, in order to improve the confirmability.

During the observations, it was not always very clear whether or not CB occurred as a consequence of the acoustical environment. It was observed that some residents started manipulating objects like sofas, garbage bins, gloveboxes or closed doors that they found in the area or encountered on the way. They moved the objects, tried to open them or played or tinkered with them. By doing so, it could be the goal to create more stimuli. We can however not be certain that the lack of stimuli makes them start manipulating, or that the sight of the object lures them to manipulate it. It can however be seen as aberrant motor behaviour, a form of CB (Zhao et al., 2016). It is, in addition, impossible to eliminate every other stimulus such as a visual stimulus or the experience of pain, which are proven to have also an influence on CB (Hodgson et al., 2014; Krishnamoorthy and Anderson, 2011). A solution could be to design an experimental study, though it would not be ethical to try to provoke CB by creating too much stimuli or leaving the PwD under-stimulated. During the inclusion of the meaning units however, this uncertainty has been taken into account. When there was some doubt about the trigger of CB, the meaning unit was omitted.

The conclusion of being able to cope better in a complex sound environment when a significant other is around was only observed by one participant. Due to the outbreak of the corona-virus however, it was not possible to include more participants to reach saturation. It can be the subject of future research to validate this finding. In addition, it can be studied if a high turnover of staff, i.e. constantly being cared for by new caregivers, people that the PwD is not familiar with, influences the feeling of being safe and thus influences the onset of CB.

It is beyond the scope of this study to map out the ideal type of sound, since there were no sounds created during the observations. The sound environment is seen as a whole and during the structural analysis it was only concluded that familiar sounds or sounds that the PwD recognizes, such as a ringing doorbell or the sound of talking, can create more peace

19 than unknown sounds or sounds that the PwD doesn’t recognize at that time, such as a plane flying over. Further research should be undertaken to explore the ratios of different sounds, sound volume and their influence on CB as well as the personal capacity of an individual to eventually create a soundscape, suited for the resident. It can also be an interesting aspect to study acoustic comfort in NH by hearing-impaired people and PwD, which will give more insight in how PwD experience acoustics and can contribute to the development of soundscapes. Wiratha and Tsaih (2015) assessed this already based on the evaluation by normal hearing individuals and concluded that sounds of nature contributed to a positive impression of the acoustical environment. Aletta et al. (2018) mapped out the holistic perception of the sound environment in the NH of a group of professionals working there.

RECOMMENDATIONS WORK FIELD

To the best of our knowledge there are no interventions targeting soundscapes in nursing homes, although there are interventions considering sound like music therapy (Wang et al., 2018) or the adding of classical music (Chaudhury et al., 2013). It can be a first step to view each person individually and to try mapping out the sounds and the amount and volume of these sounds that make this person in particular feel safe. It should be taken into account what is recognizable and familiar for the person. Being aware of the particular soundscape and knowing the resident and its history and interests quit good, can enable the caregivers to actively influence this (e.g. support a recognizable sound environment) or to design the physical acoustical environment to the needs of the residents with dementia. It can also be helpful to create a space away from the crowded places with a sound environment that is too complex, where there are less acoustical triggers and where the PwD can go and sit peacefully.

Based on the findings in this study, when soundscapes are created to improve the quality of care and reduce BPSD in residents, it can be taken into account that it is important to work with familiar and recognizable sounds. The amount of different noises, determining the level of heterogeneousness of the soundscape, should consider individual differences as well as the capacity of the people on different moments during the day. The soundscape can then function as a non-pharmacological approach to reduce CB.

It was observed that the resident showed less CB when the sounds were expected because they were announced or because the person could identify the source of the sound by looking up and giving the sound a meaning. Therefore it is advisable to notify the resident of each action during the care in order to announce the resident instead of scaring them with an unexpected noise.

In conclusion can be stated that with these findings important aspects for the ideal soundscape have come to light. Taking these aspects into account, such as familiarity of sound

20 and the capacity of each individual, a first step can be taken towards soundscapes as a non-pharmacological intervention for the management of CB. Further research into which sounds are familiar and into the capacity of a PwD is necessary to optimize the development of soundscapes.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.21

REFERENCES

Abraha, I. et al. (2016). Systematic review of systematic reviews of nonpharmacological interventions to treat behavioural disturbances in older patients with dementia. The SENATOR-OnTop series. BMJ Open. 1(7), 1-30.

doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012759

Agentschap zorg en gezondheid. (2017). Besluit van de Vlaamse regering tot wijziging van bijlage XII bij het besluit van de Vlaamse regering van 24 juli 2009 betreffende de programmatie, de erkenningsvoorwaarden en de subsidieregeling voor woonvoorzieningen en verenigingen van gebruikers en mantelzorgers, wat de voorwaarden infrastructuur betreft. Retrieved from https://www.zorg-en-

gezondheid.be/sites/default/files/atoms/files/16-17044%20BVR%20wijz%20bijlage%20XII%20infrastructuurvoorwaarden.pdf on May 20th 2019.

Aguero-Torres, H., Von Strauss, E., Viitanen, M., Winblad, B. and Fratiglioni, L. (2001). Institutionalization in the elderly: the role of chronic diseases and dementia. Cross-sectional and longitudinal data from a population-based study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54, 795–801.

Aletta, F. et al. (2018). Awareness of 'sound' in nursing homes: A large-scale soundscape survey in Flanders (Belgium). Building Acoustics,

doi: 10.1177/1351010X17748113.

Andringa, T. and Lanser, J. (2013). How pleasant sounds promote and annoying sounds impede health: A cognitive approach. International journal of environmental research and public health, 10(4), 1439-1461.

Axelsson, Ö., Nilsson, M. E. and Berglund, B. (2010). A principal components model of soundscape perception. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 128(5), 2836-2846.

doi: 10.3390/ijerph10041439

Azermai, M. (2015). Dealing with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a general overview. Psychology research and behavior management, 8, 181-185. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S44775

Benoit, M. et al. (2006). Professional consensus on the treatment of agitation, aggressive behaviour, oppositional behaviour and psychotic disturbances in dementia. The journal of nutrition, health & aging, 10(5), 410-415.

22 Brown, B., Rutherford, P. and Crawford, P. (2015). The role of noise in clinical environments with particular reference to mental health care: A narrative review. International journal of nursing studies, 52(9), 1514-1524.

doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu2015.04.020

Chaudhury, H., Hung, L. and Badger M. (2013). The role of physical environment in supporting person-centered dining in long-term care: a review of the literature. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 28, 491–500.

doi: 10.1177/1533317513488923

Cook, E. D. M., Swift, K., James, I., Malouf, R., De Vugt, M. and Verhey, F. (2012). Functional analysis‐based interventions for challenging behaviour in dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2).

doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006929.pub2.

de Oliveira, A. M. et al. (2015). Nonpharmacological Interventions to Reduce Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia: A Systematic Review. BioMed Research International, 2015, 1–9.

doi: 10.1155/2015/218980

Devos et al. (2019). Designing supportive soundscapes for nursing home residents with dementia. International journal of environmental research and public health 2019, 16(4904).

doi: 0.3390/ijerph16244904

Dyer, S.M., Harrison, S.L., Laver, K., Whitehead, C. and Crotty, M. (2018). An overview of systematic reviews of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(3), 295-309.

doi:10.1017/S1041610217002344

Ervin, K., Cross, M., and Koschel, A. (2013). Barriers to managing behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: Staff perceptions. Collegian, 21(3), 201-207. doi: 10.1016/j.colegn.2013.04.002

Fauth, E. B. and Gibbons, A. (2014). Which behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia are the most problematic? Variability by prevalence, intensity, distress ratings, and associations with caregiver depressive symptoms. International journal of geriatric psychiatry, 29(3), 263-271.

doi: 10.1002/gps.4002

Feast, A., Moniz-Cook, E., Stoner, C., Charlesworth, G. and Orrell, M. (2016). A systematic review of the relationship between behavioral and psychological symptoms (BPSD) and caregiver well-being. International Psychogeriatrics. 28(11), 1761-1774.

23 doi:10.1017/S1041610216000922

Finkel, S. I. (2000). Introduction to behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). International journal of geriatric psychiatry, 15, 2-4.

Folstein, M.F., Folstein, S.E. and McHugh, P.R. (1975) "Mini-mental state": a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res,12(3), 189-198.

Hodgson, N., Gitlin, L.N., Winter, L. and Kauch, W.W. (2014). Caregiver’s Perceptions of the Relationship of Pain to Behavioral and Psychiatric Symptoms In Older Community Residing Adults with Dementia. Clin J Pain, 30(5), 421–427.

doi:10.1097/AJP.0000000000000018

Howitt, D. (2016). Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods in Psychology. Loughborough: Pearson.

Hurt, C. et al. (2008). Patient and caregiver perspectives of quality of life in dementia. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders, 26(2), 138-146.

doi: 10.1159/000149584

International Psychogeriatric Association. (n.d.). Instructions for authors. Retrieved June 1, 2020, from https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-psychogeriatrics/information/instructions-contributors

Joling, K. J. et al. (2015). Predictors of societal costs in dementia patients and their informal caregivers: a two-year prospective cohort study. American association for geriatric psychiatry, 23(11), 1193-1203.

doi: 10.1016/j;jagp.2015.06.008

Katz, S., Ford, A. B., Moskowitz, R. W., Jackson, B. A., and Jaffe, M. W. (1963). Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA, 185, 914–919.

Kaufer, D. I. et al. (2000). Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the neuropsychiatric inventory. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 12(2), 223-239. Kok, R. and Verhey, F. (2002). Dutch translation of the Mini Mental State (Folstein et al.,1975). Krishnamoorthy, A. and Anderson, D. (2011). Managing challenging behaviour in older

adults with dementia. Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry.

Law, M. et al. (1996). The person-environment-occupation model: a transactive approach to occupational performance. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(1), 9-23. Lawton, M.P. (1986). Environment and aging. Albany, NY: Center for the Study of Aging. Lawton, M. P. (1977). An ecological theory of aging applied to elderly housing. Journal of

24 Lindseth, A. and Norberg, A. (2004). A phenomenological hermeneutical method for

researching lived experience. Scand J Caring Sci, 18, 145-153.

Liperoti, R., Pedone, C. and Corsonello, A. (2008). Antipsychotics for the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). Current neuropharmacology, 6(2), 117- 124.

O'Neil, M. E., Freeman, M., Christensen, V., Telerant, R., Addleman, A. and Kansagara, D. (2011). A systematic evidence review of non-pharmacological interventions for behavioral symptoms of dementia. Health Services Research & Development Service. VA-ESP Project 5(225), 1-69.

Patton, M.Q. (2015). Qualitative research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating theory and practice. Fourth edition. SAGE Publications, Inc.

Petrovic, M. et al. (2007). Clustering of behavioural and psychological symptoms in dementia (bpsd): a European alzheimer’s disease consortium (EADC) study. Acta Clinica Belgica. 62(6), 426-432.

doi: 10.1179/acb.2007.062.

Portney, L. G., & Watkins, M. P. (2014). Foundations of Clinical Research Applications to Practice. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited.

Prince, M., Ali, G. C., Guerchet, M., Prina, A. M., Albanese, E., and Wu, Y. T. (2016). Recent global trends in the prevalence and incidence of dementia, and survival with dementia. Alzheimer's research & therapy, 8(1), 23.

Ricci, G. (2019). Social Aspects of Dementia Prevention from a Worldwide to National Perspective: A Review on the International Situation and the Example of Italy. Behav Neurol. 2019, 1-11.

doi: 10.1155/2019/8720904.

Samus, Q. M. et al. (2005). The association of neuropsychiatric symptoms and environment with quality of life in assisted living residents with dementia. The Gerontologist, 45(suppl_1), 19- 26.

Shield, B., Connolly, D., Dockrell, J., Cox, T., Mydlarz, C., and Conetta, R. (2018). The impact of classroom noise on reading comprehension of secondary school pupils. In Proceedings of the Institute of Acoustics, 40(1), 236-244.

Steyaert, J. (2016). ‘Prevalentie: hoeveel personen in Vlaanderen hebben dementie?’, in Vermeiren, M. (Red.), Dementie, van begrijpen naar begeleiden. Brussel: Politeia. Takizawa, C., Thompson, P. L., van Walsem, A., Faure, C. and Maier, W. C. (2015).

Epidemiological and economic burden of Alzheimer's disease: a systematic literature review of data across Europe and the United States of America. Journal of Alzheimer's disease, 43(4), 1271-1284.

25 doi: 10.3233/JAD-141134

Taylor, R. R. (2017). Kielhofner's Research in Occupational Therapy. [FADavis]. Retrieved from https://fadavisreader.vitalsource.com/#/books/9780803642164/ on May 15th 2019.

Tible, O.P., Riese, F., Savaskan, E. and von Gunten, A. (2017). Best practice in the management of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Ther Adv Neurol Disord, 10(8), 297-309

doi: 10.1177/1756285617712979

To, W. M., and Chung, A. W. L. (2015). Restaurant noise: Levels and temporal characteristics. Noise & Vibration Worldwide, 46(8), 11-17.

Truax, B. (1977). The soundscape and technology. Journal of New Music Research, 6(1), 1-8.

Turpin, M, & Iwama, M. (2011). Using occupational therapy models in practice. Churchill Livingstone: Elsevier

van den Bosch, K.A., Andringa, T.C., Baskent, D. and Vlaskamp, C. (2016). The role of sound in residential facilities for people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 13(1), 61-68. doi: 10.1111/jppi.12147

van der Linde, R. M., Dening, T., Matthews, F. E., and Brayne, C. (2014). Grouping of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. International journal of geriatric psychiatry, 29, 562-568.

doi: 10.1002/gps.4037.

Volicer, L. and Hurley, A.C. (2003). Review Article: Management of behavioural symptoms in progressive degenerative dementias. The hournals of Gerontology, 58(9); M837-M845.

Wang, G., Albayrak, A. and van der Cammen, T.J.M. (2018). A systematic review of non-pharmacological interventions for BPSD in nursing home residents with dementia: from a perspective of ergonomics. International Psychogeriatrics, 31(8), 1137-1149; doi:10.1017/S1041610218001679

Wergeland, J. N., Selbæk, G., Bergh, S., Soederhamn, U., and Kirkevold, Ø. (2015). Predictors for nursing home admission and death among community-dwelling people 70 years and older who receive domiciliary care. Dementia and geriatric cognitive disorders extra, 5, 320-329.