CONSUMER

ATTITUDES

AND

BEHAVIORAL INTENTS TOWARDS A

MORE

ENVIRONMENTALLY

SUSTAINABLE DIET: A SYSTEMATIC

REVIEW

Word Count: 22.083

Stamnummer : 01602387

Promotor: Prof. Dr. Anneleen Van Kerckhove

Co-promotor: Prof. dr. jolien.vandenbroele@ugent.be

Masterproef voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van:

Master in de handelswetenschappen: Commercieel Beleid

Academiejaar: 2019-2020“Why do we bite the hand that feeds us?”

– Jager (2000)

PERMISSION

I declare that the content of this Master’s Dissertation may be consulted and/or reproduced, provided that the source is referenced.

Important note

Summary

This dissertation will provide a systematic literature review as regards 1. consumer awareness of the environmental impact of meat, and 2. consumer perceptions, acceptance and behavior towards reducing meat consumption and alternative sources of protein.

Whilst research on the matter still is rather limited, it appears that there is not yet a widespread awareness/understanding with consumers of the negative impact of meat consumption on the environment. In countries where research was conducted on awareness of the problem, most consumers are in doubt or ignorant about the problem.

And what about willingness to reduce meat consumption? Aligned with the above, various studies indicate we are confronted with what is called the ‘Meat Paradox’: many consumers say they are willing to reduce meat consumption but do not act upon (Vainio, 2019). Indeed, a majority of

consumers have not yet reduced their meat consumption or transitioned to an alternative diet, although they claim to be willing to do so (Vainio, 2019).

The review also explored attitudes of consumers towards different options they have for changing their diets. Today, plant-based alternatives are best accepted among consumers. Acceptance of cultured meat and insects is (still) much lower. However, acceptance has been growing over the years and is likely to be accelerated via proper communication on the benefits of these products.

Samenvatting

Deze literatuurstudie zal handelen over 1. in welke mate consumenten bewust zijn van de negatieve impact van vleesconsumptie op het milieu, en 2. percepties, attitudes en gedrag m.b.t. het verminderen van vleesconsumptie en consumptie van andere proteïnebronnen als alternatief voor vlees.

Hoewel er nog een tekort is aan onderzoek over het onderwerp, kunnen we wel besluiten dat de meerderheid van de consumenten zich niet bewust is van de nadelige impact van vleesconsumptie op het milieu. In de landen waar onderzoek werd gevoerd, konden we concluderen dat consumenten onzeker of onwetend zijn omtrent milieu-impact.

Verder kunnen we spreken over de ‘Meat Paradox’: veel consumenten hebben de intentie om hun vleesconsumptie te minderen, maar doen dit niet (Vainio, 2019). En inderdaad, de meerderheid van de consumenten heeft de vleesconsumptie nog niet geminderd of is nog niet overgegaan naar een meer milieubewust dieet, alhoewel ze wel beweren dit te hebben gedaan (Vainio, 2019).

Percepties, attitudes en gedrag omtrent alternatieve proteïnebronnen werd ook bestudeerd. Hieruit kunnen we besluiten dat plantaardige alternatieven het best geaccepteerd worden. Kweekvlees en insecten ondervinden nog veel weerstand, alhoewel het steeds beter aanvaard wordt. Verder is

duidelijk dat aanvaarding wel versneld kan worden via goede communicatie omtrent de voordelen van deze producten.

Preamble

The work on this thesis was performed during the global Covid-19 pandemic. The

the Covid-19 situation did not significantly impact the writing of this dissertation, since it was a systematic literature review. However, Covid-19 underscored the relevance of the topic of this thesis, i.e. need for reduced meat consumption. People with underlying health issues (that are also caused by the consumption of red meat), are the most vulnerable and were hit the hardest. Furthermore, the consumption of animals (whether these are wild or domesticated), has also contributed to this pandemic. SARS-CoV-2 is a zoonotic virus which was transferred to humans due to consumption-related contact with animals (Frank, 2007). This shows the need to transition to healthier and more environmentally friendly diets.

This preamble is drawn up in consultation between the student and the supervisor and is approved by both.

Acknowledgement

I would like to show my gratitude to the people who helped me accomplish this master thesis. I would like to thank my supervisors Dr. Anneleen Van Kerckhove and Dr. Jolien Vandenbroele. Especially Dr. Vandenbroele for her guidance and useful feedback. Without her, I would also not be aware of this problematic topic so much as I am now.

I would like to acknowledge my father, for investing so much time in me, improving my academic writing and proofreading this dissertation. I would also like to thank my mother, for the support, understanding, dedication throughout the years and the sense of responsibility she has given me.

Table of contents

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ...I

LIST OF TABLES ... II

LIST OF FIGURES ... II

1.INTRODUCTION ... 1

2.LITERATURE STUDY ... 5

2.1. The history of meat consumption: a timeline ... 5

2.2. Sustainability: history & definitions ... 8

2.3. Sustainability and behavior ... 10

2.4. Instigating behavioral change through policy measures ... 17

2.5. Role of proteins and their sources ... 19

2.6. Comparison between plant-, insect- and meat-based diets ... 21

2.7. Hypotheses ... 26

3.METHODOLOGY... 27

3.1. Search strategy and study selection procedure ... 27

3.2. Elucidation to the systematic review ... 28

4.RESULTS ... 29

4.1. Perceived environmental impact of meat production and consumption by consumers... 29

4.2. Attitudes towards alternative protein and/or willingness to replace meat with alternative protein. .... 30

4.3. Conclusions ... 45

5.DISCUSSION ... 47

5.1. Awareness of the problem ... 47

5.2. Consumer willingness to reduce and/or replace meat with alternative protein ... 49

5.3. Limitations ... 53

5.4. Suggestions for future research... 53

5.5. Implications ... 54 6.REFERENCES ...I

List of abbreviations

Abbreviation Full form

BCE Before The Common Era

BSSS Brief Sensation Seeking Scale

CAGR Compound Annual Growth Rate

E.g. Exempli Gratia, ‘For Example’

GHG Greenhouse Gas

I.e. Id Est, ‘That Is’

IVM In-Vitro Meat

M Mean

N Amount

N.a. Not Available

N.d. No Date

P Probability Value

SD Standard Deviation

S.n. Sine Nomine, ‘Without A Name’

Vs. Versus

WTB Willingness To Buy

List of tables

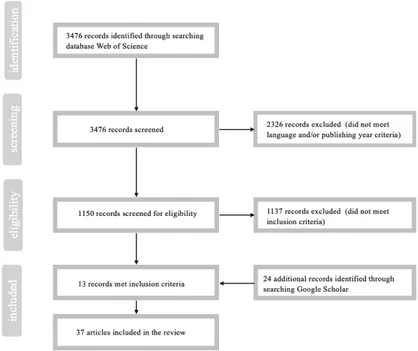

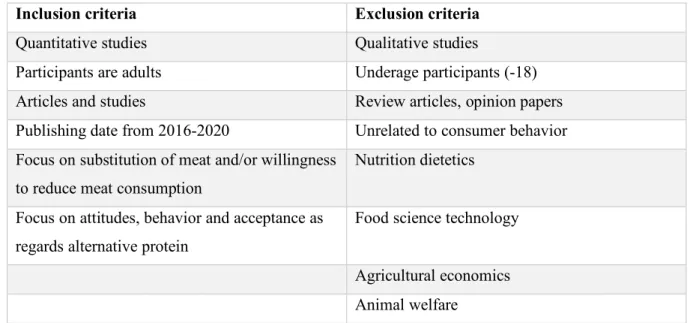

TABLE 1:ARTICLE SELECTION CRITERIA ... 28

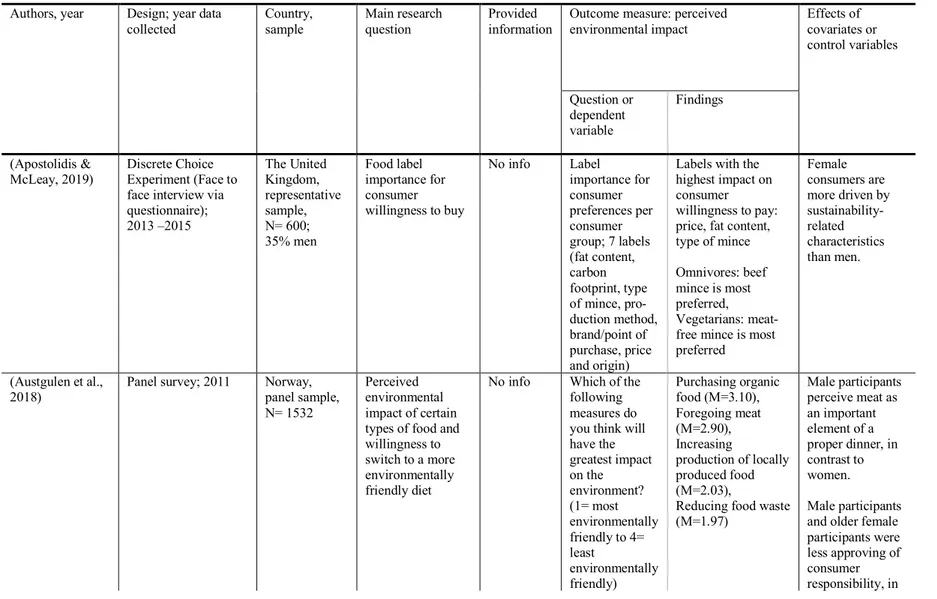

TABLE 2:PERCEIVED ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT OF MEAT PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION...XX

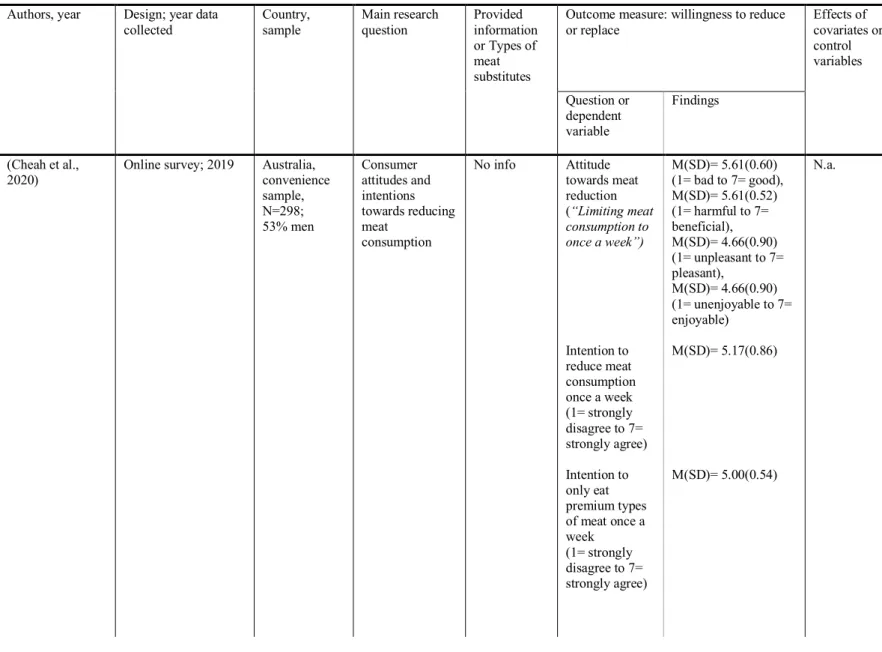

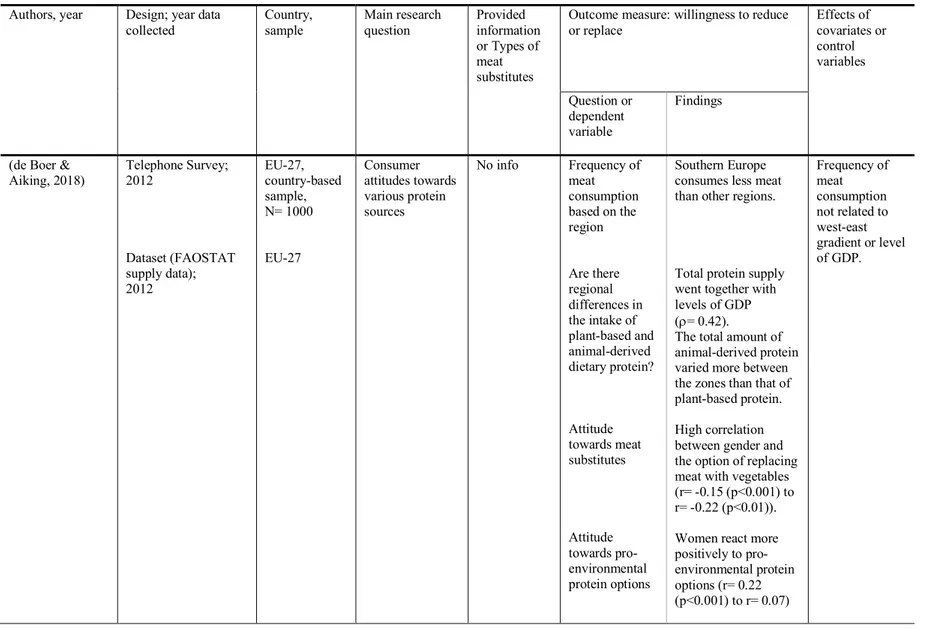

TABLE 3:ATTITUDES TOWARDS AND/OR WILLINGNESS TO REDUCE MEAT OR CHANGE DIET ... XXIV

TABLE 4:ATTITUDES TOWARDS AND/OR WILLINGNESS TO REPLACE MEAT WITH PLANT-BASED ALTERNATIVES ... XXVII

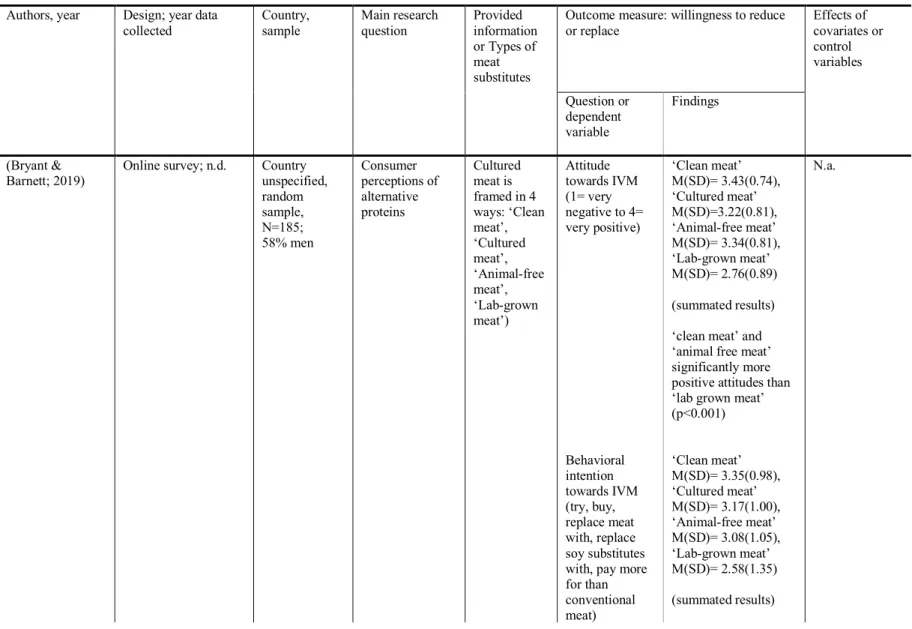

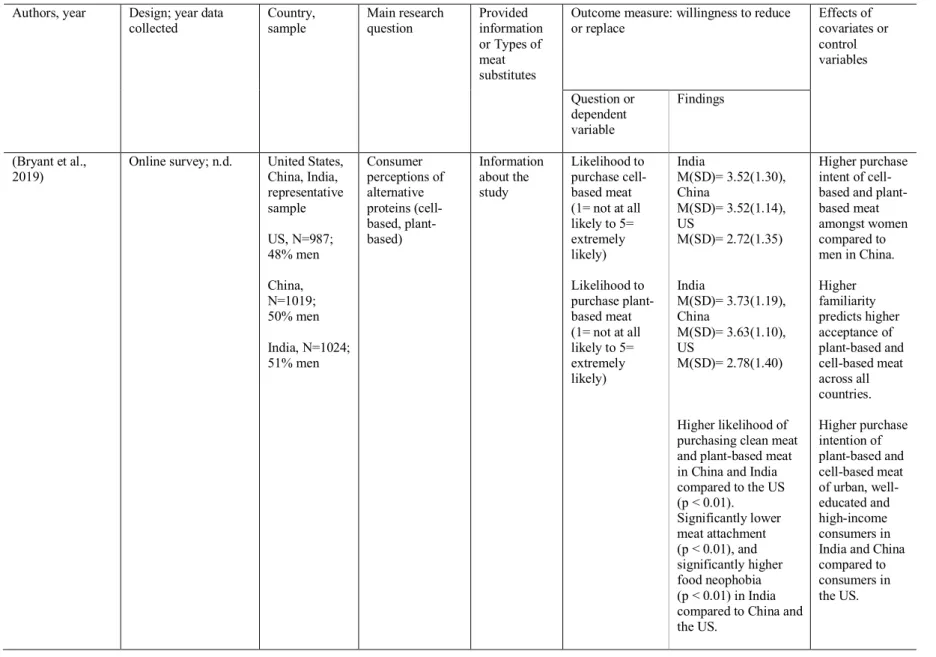

TABLE 5:ATTITUDES TOWARDS AND/OR WILLINGNESS TO REPLACE MEAT WITH CELL-BASED ALTERNATIVES... XXX

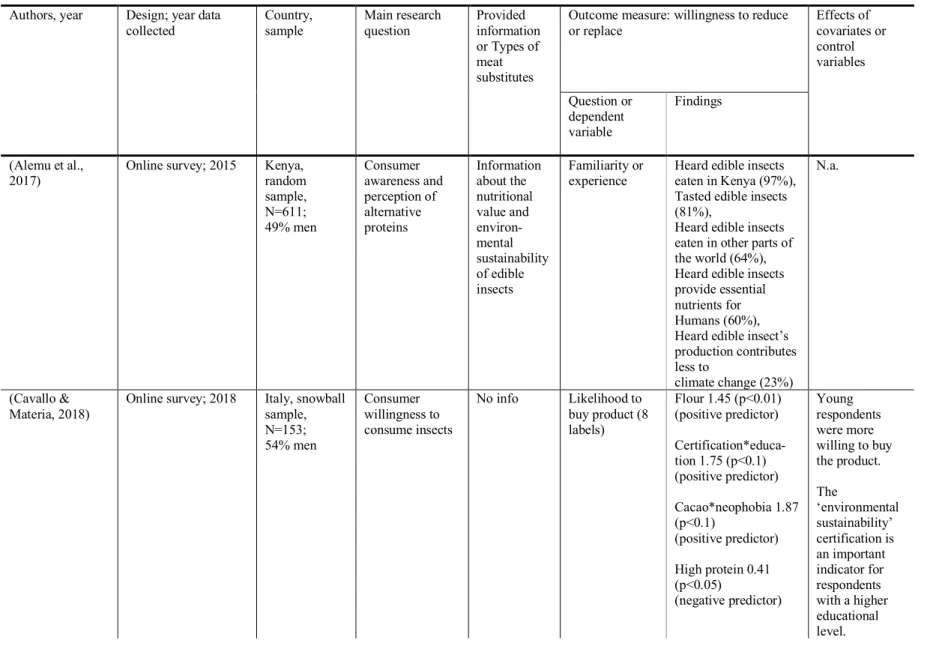

TABLE 6:ATTITUDES TOWARDS AND/OR WILLINGNESS TO REPLACE MEAT WITH INSECT-BASED ALTERNATIVES ... XXXVIII

TABLE 7:COMPARING ATTITUDES TOWARDS AND/OR WILLINGNESS TO REPLACE MEAT WITH ALTERNATIVE PROTEINS ... XLVIII

List of figures

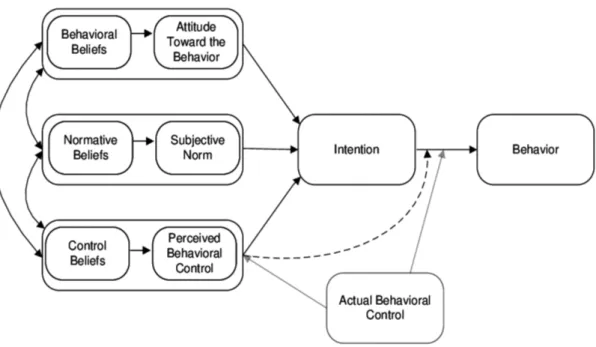

FIGURE 1:THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOR (AJZEN,1991) ... 13

1. Introduction

BackgroundAs will be shown further on, there is clear and urgent need to instigate behavioral change with consumers to switch to more sustainable diets reduced in meat content.

The focus of this dissertation is to gain insight in consumer awareness of the environmental impact of meat consumption and attitudes/behaviors of consumers towards more environmentally sustainable diets.

Meat is for the majority of consumers “the preferred source of protein” (Frank, 2007, p. 320). However, its production entails a lot of environmental issues and is a very unsustainable food supply. Today, livestock contributes to 14.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions, 83% of agricultural land use and 27% of fresh water consumption (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2013; Gerber, Steinfeld, Henderson, Mottet, Opio, Dijkman, Falcucci, & Tempio, 2013; Horgan, Scalco, Craig, Whybrow, & Macdiarmid, 2019; Pimentel & Pimentel, 2003). In addition to this, 30% of total global land is used to raise cattle (Steinfeld, Gerber, Wassenaar, Castel, Rosales, Haan, 2006). Furthermore, cropland suitable for human consumption is instead, being used to cultivate livestock feed (Frank, 2007). The constant increase in consumption of animal products is leading to the loss of biodiversity, greenhouse gas pollution and an excessive use of water, energy and natural resources (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017; Ferrari, Cavaliere, De Marchi, & Banterle, 2019). Additionally, when land is cleared in favor of agriculture (to grow feed for animals, or grazing land) in combination with the already heavy emission in GHG by the meat industry, the greenhouse effect is enhanced, warming the earth’s surface even more (NASA, n.d.). As a result, weather has become unpredictable and natural disasters, such as hurricanes, forest fires, and the rise of sea levels and floods due to the melting of ice sheets and glaciers, have become more frequent (National Geographic Society, 2019). Furthermore, climate change has impacted agriculture, since what used to be good regions to establish farmland, are now unreliable regions because of changed temperatures and unexpected rainfalls (National

Geographic Society, 2019).

If nothing is done, the situation will only exacerbate in the future. The global population is expected to increase by 2 billion peoplein the next 30 years, resulting in an Earth’s population of 10 billion people by 2050 (United Nations, 2019). As a consequence, GHG emissions derived from food and livestock will increase by 80% if we maintain the status quo (Bonnet, Bouamra-Mechemache, Réquillart, & Treich, 2020), and food supply will need to increase by 70% in order to feed every human being (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, 2009). Moreover, demand for these products (at

the individual consumer level) is increasing in developing and some developed countries (Ritchie, 2017).

And yet, if we change our eating habits, we can turnaround this path to self-destruction. In this respect, a very interesting study was conducted by Tilman and Clark in 2014. The research showed that if globally, everyone would follow the Mediterranean1, pescatarian2 and vegetarian3 diet, greenhouse-gas

emissions per capita would reduce by respectively 30%, 45% and 55% (Tilman & Clark, 2014). Furthermore, there would be no net increase in food production emissions by 2050 when the global population would stick to these diets (Tilman & Clark, 2014). This contrasts with the 32% GHG emissions increase per capita (hence, a global net effect of +80% GHG emissions) if we would maintain the status quo (Tilman & Clark, 2014).

Evidently, feeding the entire population and climate change are interrelated and are combined the most pressing challenges for the future. So, because of the detrimental impact on the environment, our health and overpopulation, people need to transition to more sustainable diets. But this transition will face significant resistance and barriers.

Food has an emotional, social and cultural meaning and meat is culturally and institutionally entrenched in the lives of people (Bereza, 2019). Especially, the love for livestock-derived foods is strengthened by advertising and false beliefs, such as the common belief that it is superior in terms of being healthy and nutritious (Lacroix & Gifford, 2019). Other drivers for the love for meat are that meat represents a symbol of strength, is part of traditions and has an appealing taste and texture (Marinova & Bogueva, 2019). Social norms have a big impact on consumer attitudes and friends and/or family influence a person’s diet routines (Cheah, Sadat Shimul, Liang, & Phau, 2020). What will become clear in this thesis, is that willingness to consume alternative sources of proteins is mostly inhibited by a person’s culture, individuality, food neophobia and the perception of a meat-free diet as ‘different’. To conclude: Eating habits are routinized, hard to change and there is a lack of willingness and social acceptability of consumers to change their diet.

1 Diet that consists of mostly plant-based foods, grains, olive oil, beans, seafood, and a very limited amount of

meat and seafood (Brazier, 2020)

2 Diet that excludes meat

Theoretical framework: The ‘Commons Dilemma’ discusses consumer behavior with regards to consumption of a collective environmental resource (Jager, 2000). In the case of meat consumption, meat derived from livestock might be seen as a collective resource with growth capacity, since these animals are cultivated. This is not so much for fish, where in most cases, consumption exceeds the natural growth rate, hence the risk of extinction (Jager, 2000). Since cultivation of livestock requires grazing lands and arable land to grow livestock feed, deforestation and freshwater consumption on its turn are resources that are being depleted (Jager, 2000). In addition to this, nowadays, meat products are easily accessible (whether it is due to price or supply), and the easier resources are available, the quicker they are exhausted by man (Jager, 2000). This might also contribute to the high consumption of livestock-derived products. Environmental activists (e.g. Greta Thunberg, Jane Fonda) have gained attention and actions (e.g. respectively ‘School strike for climate’ and ‘Fire drill Fridays’) have

gathered thousands of people to demand action in favor of the planet. However, while it seems that the majority of people is aware there are some real disastrous environmental problems, there is not much talk about what consumers, as individuals, can do. People often find the problem is too big for them to handle and therefore refuse to change behaviors (Austgulen, Skuland, Schjøll, & Alfnes, 2018). And for those who do feel we are on the wrong track and need to change diets, we can speak about an intention-behavior gap, also called the ‘Meat Paradox’: many consumers say they are willing to reduce meat consumption but do not act upon (Vainio, 2019). And, indeed, a majority of consumers have not yet reduced their meat consumption or transitioned to an alternative protein diet, although they claim to be willing to do so (Vainio, 2019).

This intention-behavior gap is explained by The Theory of Planned Behavior. This theory, developed by Ajzen in 1991, based on The Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), claims that the immediate predictor to one’s behavior is one’s intention. However, these theories assume that humans are rational beings, and perceive a low level of need satisfaction or behavioral control (Jager, 2000). Nevertheless, people act emotionally and do not often make the most rational choices (Jager, 2000). In many occasions, intentions are not enacted upon: conflicts often rise between the intention (what one planned to do or should do) and the willingness one feels at the moment (Sheeran & Webb, 2016). People seek to justify current behavior in order to be able to indulge, resulting in undermining the intention realization (Sheeran & Webb, 2016).

To conclude, intentions do not always lead to behavior or behavioral change. Liobikienė, Mandravickaitė, and Bernatonienė (2016) concluded that subjective norms, in part, determined sustainable purchase behavior. In addition to this, Vermeir and Verbeke (2006) also concluded that social pressure has a bigger significant impact on willingness to buy (behavior) than personal attitudes. Indeed, research has shown that intentions do not necessarily lead to sustainable consumption (Park & Lin, 2018). For example, in research executed by Park and Lin (2018), an actual gap was reported

between intentions to buy sustainable fashion and actual behavior: more than 35% of participants showed high intentions but did not anticipate behavior.

Research gap & relevance: As indicated earlier, this dissertation focuses on the need to instigate behavioral change with consumers to switch to more sustainable diets reduced in meat content. In 2017, Hartmann and Siegrist published a systematic review related to the above-mentioned topic. They analyzed 1. the extent to which consumers are aware of the environmental problems related to meat, and 2. consumer attitudes and behaviors towards more sustainable food sources of protein (plants, insects, cultured meat). In their review, they included articles with a publishing date up until 2016. At the time of this systematic review, articles on this subject were still scarce and there is a need for an updated systematic review of the same topic.

Research question 1: Has consumer awareness as regards the environmental impact of meat increased since what has been concluded by Hartmann and Siegrist in 2017?

Research question 2: Have consumer attitudes, perceptions and behaviors as regards reduced meat consumption changed since what has been concluded by Hartmann and Siegrist in 2017?

Research question 3: Have consumer attitudes, perceptions and behaviors as regards alternative protein sources for meat changed since what has been concluded by Hartmann and Siegrist in 2017? This master thesis is especially relevant for:

• Policy-makers, since measures at governmental level must be taken in order to develop collective behavioral change; and

• Researchers, to provide them with a summary of what has been done and what still needs to be done in the space covered by this dissertation.

Outline: This dissertation will firstly, provide a comprehensive literature study of all underlying issues at play,then explain the method on how studies focusing on the research questions were combined and analyzed and lastly, provide insight into awareness of consumers of the environmental issues related to meat consumption and their attitudes & behaviors towards more sustainable alternatives to meat (plant-, insect-, and cultured meat protein).

2. Literature study

2.1. The history of meat consumption: a timeline

In contrast to many common beliefs, early hominid (2 to 3 million years ago) consumption patterns consisted of herbivorous diets (Longo & Malone, 2006). Hunter-gatherers (1.8 million years ago) first secured food provision through maintaining an herbivorous diet, additionally collecting insects and remains of animal flesh left behind by predators (Mithen, 1999; Perlès, 1999). Advancements in tool technology then humankind the opportunity to hunt bigger animals and provide their families with higher in quantity and quality fats (Smil, 2013). However, animal-flesh protein was only

complementary as research regards fossilized human teeth has shown (Flandrin et al., 1999; Perlès, 1999). These newer and better hunting tools have led to the extinction of various animals and disastrous consequences on biodiversity: humankind killed more than necessary for survival, which impacted species suitable for human consumption as well as existing predators (Kalof, 2007; Smith, 1975).

Due to the combination of extinct animals and changes as regards climate, food provision alternatives emerged in the Early Neolithic period (Bar-Yosef, 2002; Diamond, 2002). Some hunter-gatherers domesticated animals and plants, and transitioned to a sedentary lifestyle (Bar-Yosef, 2002; Diamond, 2002). Culturally seen, proprietorship of livestock symbolized high social standing (Goudie, 2000; Marciniak, 2005; Simoons, 1994). However, in order to protect their livestock, hunter-gatherers terminated predators (Redman, 1999). In combination with animal habit loss due to their sedentary lifestyle (Verhoeven, 2004), this resulted in the extinction of several species (Redman, 1999; Verhoeven, 2004). Crop husbandry and farming animals were not always executed in an efficient manner (Marciniak, 2005). Poor crop cultivation resulted in land damages, and domesticating animals were more labor-intensive compared to the hunting of wild animals (Marciniak, 2005). Furthermore, animal agriculture did not always lead to a sufficient supply of food (Marciniak, 2005). Lastly, the close relationship between humankind and animals also introduced the risk of zoonotic diseases (Redman, 1999).

The sedentary lifestyle, in which humans cultivated crops and domesticated animals, became a

superior way of survival (Diamond, 2002; Verhoeven, 2004). Domestication gained interest, and more hunter-gatherers transitioned during the Middle/Late Neolithic period (Diamond, 2002; Verhoeven, 2004). Also, the domestication of animals gained new uses: labor and extraction of new animal-derived products, i.e. farm manure, wool, eggs and milk (Verhoeven, 2004). Hence, the possession of domesticated animals became more profitable (Verhoeven, 2004). In addition to this, cultural and

political-economic tendencies influenced the superiority of some animals (Chiles & Fitzgerald, 2017; Marciniak, 2005; Simoons, 1994).

As we transition into the Bronze Age (2500 BCE), social systems became more complex and higher degrees of social stratification were established (Chiles & Fitzgerald, 2017). Again, proprietorship of livestock, and the ability to consume meat, signaled wealth and status (Spencer, 1993). In addition to this, social pressure was high: those who refused to engage in meat consumption, were not considered society members (Preece, 2009). However, meat was consumed in little amounts, mostly during events (Montanari, 1999). Ecologically seen, farming animals was still at the environment’s expense and resulted in land degradation, soil erosion and damage to plants (Redman, 1999; Williams, 2005). As the global population increased in the Iron age (1200 - 600 BCE, depending on region), agriculture and dependence on livestock intensified, in contrast to hunting practices (Chiles & Fitzgerald, 2017; Raish, 1992). However, meat was not necessary for survival (in contrast to grain) and was thus seen as a luxury product for the wealthier (Dupont, 1999). Especially so in Rome, where the consumption of meat was a way of culturally superior differentiation as regards other societies (Dupont, 1999). And again, meat production practices negatively impacted the environment while ideologies justified animal slaughter (Cockburn, 1996; Soler, 1999; Spencer, 1993; Preece, 2009).

In the early Middle Ages, meat production amplified and land was increasingly being converted into grazing land (Hoffmann, 2014). As a result, similar to what happened in the hunter-gatherer era and early Neolithic period, predator animals (i.e. certain bears and wolves) went extinct because men hunt them down in order to safeguard livestock (Hoffmann, 2014). Over time, deforestation and the exhaustion of land have led to issues as regards crop cultivation and the dependence on international trade for beef consumption in central Europe (Hoffmann, 2014). To elaborate, while meat production had caused problems as regards land exhaustion and deforestation, land became unsuitable for crop agriculture as well, which would have provided people more food in the first place (Hoffmann, 2014). After the Black death had appeared in Europe, population size, demand for food and labor stock shrunk (Edwards, 2011). Labor deficits resulted in more employment, which meant higher salaries and thus granting more people the opportunity to consume meat (Kalof, 2007). It had become clear that the economic value of meat was more stable than that of crops, hence the increase in investments in livestock and the increase of land repurposed as grazing lands (Wallerstein, 2011). These insights are considered to be the root of capitalism (Rifkin, 1992; Wood, 2002). The consumption of meat was also strongly impacted by the common belief meatless diets ware harmful to one’s health, and in addition to this, many influential people (i.e. Descartes), promoted animal exploitation (Preece, 2009; Spencer, 1993).

Colonized America (as of 1607) was very attractive because of its cheap land (Anderson, 2004; Cronon, 2011). The ownership of livestock by primary colonizers was highly determinant for food provision and economic prosperity (Anderson, 2004; Cronon, 2011). Again, the overexploitation of livestock meant the destruction of vegetation in certain areas and settlers would simply reallocate their business elsewhere, resulting in further deforestation (Cronon, 2011).

After the American Revolution (1765-1783) took place, the new established American government promoted international trade and investments were made as regards infrastructure and land (Danbom, 2006; Ogle, 2013). The establishment of a meat byproduct industry made developing new products based on (previously wasted) animal remains possible (Danbom, 2006; Ogle, 2013). Technological advancements (i.e. refrigerating technology) made it possible to establish an increased distance

between where production, process and consumption took place (Fitzgerald, 2015). In addition to this, heavy competition and the desire to acquire profit, resulted in overgrazing (Sheridan, 2007). At a certain point, American meat consumption was promoted both by farmers (in favor of profit) and the government (Preece, 2009). Governmental measures (in 1832, after a cholera outbreak) were taken to the drastic extent of a national ban, restricting fruit and vegetable consumption and encouraging meat and alcohol intake (Preece, 2009). Additionally, articles published in certain American medical journals, criticized, ridiculed and stereotyped consumers who maintained meatless diets (Iacobbo & Iacobbo, 2004). Again, influential figures, in this case George Beard, stereotyped meat-eating consumers to be superior to others (Belasco, 2006).

As from 1890, meat has been produced at “the largest scale possible” in order to maximize profits (Chiles & Fitzgerald, 2017, p. 12; Ogle, 2013; Stull & Broadway, 2004). Industrializing the meat industry made governmentally-desired economic growth possible (Roberts, 2009). Additionally, during World War II, meat was promoted to be the key ingredient in one’s diet, especially as regards soldiers (Belasco, 2006). The fact that meat was promoted as a major component of a man’s diet, lead to the masculine symbol it is today (Chiles & Fitzgerald, 2017). In addition to meat framing as a superior ingredient in one’s meal, mocking meatless diets went as far as being broadcasted on television (Iacobbo & Iacobbo, 2004).

To conclude, history has made clear why the consumption of meat has evolved in the form of a habit. Food is one of few products that is more susceptible to be consumed in a symbolic context, and that is why it signals who we are (Dolfsma, 1999). Meat has always represented a symbol of food security and social status (Montanari, 1999), to the extent of ridiculing meatless diets (Chiles & Fitzgerald, 2017). Unfortunately, all this is at the expense of the environment (Chiles & Fitzgerald, 2017).

2.2. Sustainability: history & definitions

Sustainability has its roots in the 18th century (Caradonna, 2014), but only came to the attention in the

late 1980s and eventually got shape by The United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development in 1987 when Our Common Future was published (Dresner, 2008).

Sustainability is derived from the term ‘sustainable’ which can be best explained as ‘the capability of being continued’ (“Sustainable,” 1965). The term focusses on the present, in contrast to sustainable development which has a more long-term focus (Brundtland, 1987). As infamously cited from the Our Common Future Report by Gro Harlem Brundtland (1987), the definition of sustainable development is as follows: “Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” (p. 41).

However, Brundtland’s definition entails following misconception: the ‘development that meets the needs of the present’ criterion cannot be met (Károly, 2011). Technological development creates newer needs every day and in addition to this, needs vary across the globe because of economic differences with regards to developed and developing countries (Károly, 2011). According to Maslow’s pyramid of needs, five types of needs are identified (in order of highest importance) (Maslow, 1943; Mcleod, 2020):

• Basic needs:

o Physiological needs

§ Air, water, food, shelter, sleep, clothing, reproduction o Safety needs

§ Personal security, employment, resources, health, property • Psychological needs

o Social needs

§ Friendship, intimacy, family, sense of connection o Esteem needs

§ Respect, self-esteem, status, recognition, strength, freedom • Self-fulfillment needs

o Self-actualization needs

§ The desire to become the most a person can be.

We can derive from this that needs in developing countries will be met faster because the focus primarily lies on basic needs (Chand, 2014). This in contrast to developed countries, where basic human needs are more straight-forward and people will pay more importance to realize esteem and

self-actualization needs (Chand, 2014). It is in human nature that when one need is satisfied, humans will be motivated to satisfy the next one (Chand, 2014). People always desire more needs to be fulfilled (Chand, 2014). In addition to this, we can categorize needs into ‘quick-needs’ and ‘slow-needs’, respectively needs that are satisfied rather fast and needs that need time to be satisfied (Jager, 2000). Hence, here as well, developing and developed countries show differences between what needs may be defined as ‘quick-needs’ and ‘slow-needs’.

Economically seen, sustainability is not interesting unless it maximizes return on investment, which does not happen often and most of the time requires investing in resources (Jager, 2000), e.g.

sustainable forestry in order to equalize deforestation in favor of livestock grazing/crop land. Hence, it is important to note that the terms ‘growth’ and ‘development’ are completely different from each other. As Goodland (1995) wrote: “Growth implies quantitative physical or material increase; development implies qualitative improvement or at least change.” (p.9). Environmentally sustainable development does not support (sustained) economic growth because sustainable levels of production and consumption are below those that would lead to a growth in the economy (Goodland, 1995). Higher levels of production and consumption that result in economic growth lead to higher carbon emissions and are disastrous for the environment (Ma & Jiang, 2019). In addition to this, developing countries that desire to accelerate their growth neglect environmental issues and consumers in developed countries have established an excessive demand for resources unnecessary for sensible living (Mittal & Gupta, 2015). Economic growth has in the past led to resource depletion and overexploitation (Mittal & Gupta, 2015). This is due to sophisticated technology, consumerism, intense competition and an unequal distribution of resources (Mittal & Gupta, 2015).

Furthermore, sustainability is constituted of three pillars: social, economic and environmental

sustainability (Goodland, 1995). Hence, it is not possible to talk about sustainable development across the social and economic pillar, when environmentally seen, it is not sustainable at all (Goodland, 1995).

2.3. Sustainability and behavior

People rely on the planet to live. However, we wreak havoc to the place that provides us the means to survive (Jager, 2000).

To begin, we need to distinguish the differences between attitudes, intentions, behaviors and habits. Attitude refers to how much a person (dis)likes something, based on three components: cognitive, affective and behavioral information (Maio, Haddock, & Verplanken, 2018). A person’s intention is one’s motivation to execute a plan or perform certain behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Maio et al., 2018). However, intention is not to be confused with one’s motive, what is the underlying reason to perform an act or certain behavior (Surbhi, 2020). A person’s behavior is the way one acts, individually or towards others, as a reaction to a preceding stimulus or is established over a longer period of time (“Behavior,” 1989). Lastly, habits can be defined as repeated behavior (Frank, 2007).

Eating habits find their roots when we are children, since parents decide our consumption choices (Frank, 2007). Whether somebody has established the habit of (not) consuming meat is dependent on the family and society he/she is born in (Frank, 2007). Hence, institutions (i.e. family, government, economy, education, religion) influence one’s habits (Frank, 2007). Friedman (1990) explains that what we consume represents our social identity: how we regard ourselves and how we want to be regarded as by others. Evidently, when people do not comply to the average social identity and social norms (e.g. consuming meat), combined with historical deep-rooted associations with meat

(masculinity, wealth, power) (Adams, 1990), negative reactions of peers will follow (Frank, 2007). Frank (2007) concludes that “social forces drive individual habits” (p.335). We speak of ‘path dependency’ and ‘lock-in’ since people cannot choose what situation they end up in as a newborn, which evidently impacts early-life choices that influence future perspectives and decisions (Frank, 2007). The latter affects on its turn perceived choice variety (North, 1993). As regards meat consumption, familiarity with meat products and meat-including recipes provoke repeated

consumption behavior (Frank, 2007). Many times, consumers are not aware of alternatives, enforcing repeated purchase behavior, since these alternatives are not present in their ‘mental choice set’ (North, 1993). In addition to this, even when consumers are aware of environmental problems and meat substitutes, it is hard to kick the habit (Festinger, 1957). Marketing and advertising meat consumption also impact one’s habits, since it promotes meat consumption as ‘desirable’ behavior (Frank, 2007). Advertising meat as desirable consumption has the ability to affect children’s food preferences and discourage consumers to behave in a more sustainable way (Institute of Medicine 2006; Redmond, 2000). The meat market can also be called a ‘locked-in’ market, since consumers are satisfied as regards their consumption, and therefore copy their own behavior (Jager, 2000).

In cases of uncertainty as regards options, they will copy others (Jager, 2000). Therefore, it is difficult to gain wide acceptance and purchase intents of superior substitutes (Jager, 2000). However, when cognitive dissonance is apparent, bad habits such as unsustainable (meat) consumption can break (Festinger, 1957). Festinger (1957) explains the theory as a conflict between beliefs/perceptions and behavior. He states that when habits are deep-rooted, like meat consumption, changing beliefs and perceptions can ultimately change repeated behavior (Festinger, 1957).

In a more elaborate way, Jager (2000) states that behavior, or behavioral change for that matter, is susceptible to micro-level and macro-level drivers. Micro-level drivers are defined as needs,

opportunities, abilities, behavioral control and uncertainty (Jager, 2000). These micro-level drivers are interrelated (Jager, 2000). Consumers use opportunities to satisfy needs and/or change abilities (Jager, 2000). The abilities one has are defined as one’s “physical, financial, legislative and social/cognitive resources” (Jager, 2000, p. 108). Behavioral control refers to one’s ability and resources to influence individual control over opportunities (Jager, 2000). Uncertainty concerns the gap between consumer expectations and performed behavior, and when uncertainty is high, consumers will copy others’ behavior (Jager, 2000). This phenomenon is also called automatic social processing, since not much elaboration is done by the consumer, except the decision to imitate others (Jager, 2000). Consumers use a ‘mental map’ in which the way needs are usually satisfied, and abilities to change opportunities are usually done, are memorized (Jager, 2000). Thus, if consumers lack behavioral control over purchase behavior, for example in contexts of low opportunity to buy meat products, abundance of opportunities to buy meat substitutes, low ability to pay for conventional meat (in case prices have risen), and high financial ability to purchase meat substitutes (in case prices are lower than those of conventional meat), basic needs will be satisfied by consumption of substitutes. Uncertainty will always be a burden to overcome in the beginning of a drastic behavioral change, however, the mental map will quickly be updated (Jager, 2000).

Next to above-mentioned micro-level drivers of behavior, macro-level factors also determine behavior (Jager, 2000). Macro-level drivers of behavior include technological, economical, demographical, institutional and cultural changes (Vlek, 1995). Changes at technological level discuss one’s ability to perform behavior and measures like decreasing/increasing supply of respectively meat and meat substitutes (Vlek, 1995). Economical changes are changes at a financial level (Vlek, 1995), e.g. increasing prices for meat products and decreasing prices for meat substitutes (whether it is through taxes or subsidies). Third, demographic drivers of behavior such as the increasing global population and the need to increase food supply will also impact availability of food and thus impact

opportunities to buy and hence buying behavior (Vlek, 1995). Fourth, institutional changes (Vlek, 1995), regarding the topic would not be concerning supervision on consumption, but could be done by

implementing laws that repurpose land and/or forbid unsustainable deforestation in favor of livestock. Lastly, cultural changes may include a reorganization of the importance of needs (Vlek, 1995), which depends on whether the respective country is already developed or in a developing phase.

Jager (2000) also explains that behavior develops over time and that certain dynamics take place in order to make behavioral changes. He distinguishes two types of dynamics that constitute behavior and behavioral change: herd and habit behavior (Jager, 2000). First of all, herd behavior concerns the way people imitate each other, whether this is due to a high level of uncertainty, satisfaction or desires (Jager, 2000). The more people engage in this behavior, the more the impact it has on the macro-environment (Jager, 2000). This means that, in the case of consumption behavior, the more people consume meat and live in an unsustainable way, the more people will copy it, and the larger the effect will be on the environment. Second, if certain unsustainable behavior leads to the satisfaction of needs, this will result in repetition and habit formation, in which the consumer does not carry out an extensive amount of cognitive processing (or automatic processing) (Jager, 2000). When for example, the consumption of meat results in the satisfaction of social and physiological needs, consumption yields reward and will therefore become recurrent behavior. However, when meat prices rise and supply decreases, chances are the consumer will break this ‘habit barrier’ and automatic processing will transition into an elaborated amount of cognitive processing (reasoned processing) in order to obtain suitable substitutes.

As mentioned in the introduction, the theoretical framework this dissertation is based on is The Theory of Planned Behavior by Ajzen (1991), which is on its turn based on The Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). The theory explains the determinants of one’s intention and that intentions are the preliminary factor to behavior.

Figure 1: Theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991)

Elucidation to the figure: • Behavioral beliefs

o The belief in the probability that one’s behavior will result in a certain outcome (University of Massachusetts, n.d.a)

§ Behavioral beliefs influence attitudes (Maio et al., 2018). • Normative beliefs

o The belief that concerns the perceived behavioral expectations of peers (University of Massachusetts, n.d.b)

§ Normative beliefs constitute determinants of subjective norms (Ajzen, 1991) • Subjective norms concern the perceived social pressure (Maio et al.,

2018) • Control beliefs

o The believed difficulty one feels to display certain behavior

§ Perceived behavior control concerns the resources, opportunities and hindrances one beliefs one has (Madden, Ellen, & Ajzen, 1992)

§ The more perceived resources and opportunities, and the lower hindrances, the higher the perceived behavior control (Madden, Ellen, & Ajzen, 1992) • Actual behavioral control

o One’s actual ability and resources to display certain behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Intentions to transition to more sustainable diets do not always lead to sustainable behavior, and positive attitudes towards a more sustainable lifestyle, do not always lead to intentions to make (sustainable) behavioral change (Jager, 2000). The fact that intentions do not always lead to behavior is due to the previous-mentioned behavioral dynamic: habit formation behavior (Aarts, Knippenberg, & Verplanken, 1992; Bentler & Speckart, 1979; Eagly & Chaiken, 1993; Ronis, Yates, & Kirscht, 1989; Triandis, 1977; Verplanken & Aarts, 1994). When habits have been formed, it undermines the ability of intentions to take place in the form of behavior, however, when behavior has not transformed into habits, but instead is new, the intention-behavior relationship will be stronger, and the intention is more likely to transition to performed behavior (Aarts, Knippenberg, & Verplanken, 1992; Bentler & Speckart, 1979; Eagly & Chaiken, 1993; Ronis, Yates, & Kirscht, 1989; Triandis, 1977; Verplanken & Aarts, 1994).

Regarding a sustainable lifestyle, consumers show big discrepancies between positive attitudes and intentions compared to enacted behavior. As Jager (2000) stated in his paper: people are aware of, and have formed their own opinion about environmental issues. However, this is not conformed to their actual behavior that is “far from sustainable” (Jager, 2000, p. 3). The commons dilemma discusses consumer behavior with regards to collective resource harvesting (Jager, 2000). The central question here is why some disregard the environment and others do their best to preserve (Jager, 2000). Four dilemmas in a meat consumption context are discussed: benefit-risk-, temporal-, spatial- and social dilemma (Jager, 2000). First, the benefit-risk dilemma concerns the satisfaction of the level of need fulfilment and its associated environmental risks (Jager, 2000). Second, the temporal dilemma discusses the balance between current satisfaction (as regards: security, comfort, wealth) and future survival (Jager, 2000). Third, the spatial dilemma discusses to what extent people should limit their own need fulfilment in order to preserve the environment (Jager, 2000). Lastly, the social dilemma discusses to what degree people should limit their own need fulfillment in order to safeguard collective well-being (Jager, 2000). In a meat consumption context, it becomes clear throughout this dissertation that consumers prioritize their own need satisfaction to future well-being of the

community and the environment. These dilemmas especially highlight the equilibrium between individual short-term gains versus collective long-term gains (Jager, 2000). Indeed, research has shown that individual short-term need satisfaction is prioritized (Dawes, 1980; Hardin, 1968; Vlek, 1996). Hence, to conclude, there are several reasons that might explain the intention-behavior gap in an environmental setting: people are not aware, underestimate or are uncertain about the problem, are

incapable of changing behavior, feel that changing to more sustainable behavior might deteriorate their quality of life, have the perception of ‘individual change will not have impact on the issue’ and lastly, they are waiting for others to change behaviors first (Austgulen et al., 2018; Jager, 2000; Vermeir & Verbeke, 2006).

Hartmann and Siegrist concluded in their previous systematic review in 2017 that awareness of the environmental impact of meat is very low. Participants in the various studies conducted,

underestimated the detrimental environmental impact of meat consumption (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017). In two out of three studies, gender differences were found with women expressing more concerns about the environmental impact compared to men (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017). Two studies in which no information about the environmental impact of meat was given prior to asking the

questions, showed that most consumers are unaware of the environmental consequences (in the two studies, only respectively 18% and 38% agreed with the fact there is an environmental issue related to meat consumption) (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017). However, even when information is given about the issue prior to answering the questions, people still underestimate the seriousness of the issue

(respectively 58% and 64% agreed with the fact there is an environmental issue related to meat consumption) (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017).

Also, no clear picture emerged from the studies researched by Hartmann and Siegrist (2017) on consumer willingness to reduce meat consumption. Different studies show very large variation in the reported ‘willingness to consume’ figures. At least in part, this is due to the fact that in some studies information was provided prior to the survey about the environmental, animal and health impact of meat (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017). When information was provided, willingness to reduce meat consumption was found to be higher (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017). However, one study examined the direct correlation between providing information and willingness to reduce meat consumption (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017). The results showed that there were no big changes in behavioral intents prior or after information was given (Cordts, Nitzko, & Spiller, 2014). Hartmann and Siegrist (2017) concluded that this relationship remained unclear, in contrast to a clearly defined relationship between knowledge (participants already possessed) about the topic and higher willingness to reduce meat consumption. Willingness to reduce meat consumption also showed strong variation across different profiles of people. It was especially low for males and for people of certain ethnic backgrounds (e.g. participants from Turkish backgrounds were less likely to reduce meat consumption compared to Chinese and Dutch people) (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017). Furthermore, health considerations were identified as a more convincing driver for a reduction in meat consumption than environmental considerations (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017). The systematic review suggested that more research needed to be done concerning behavioral differences across ethnic backgrounds (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017).

As will become clear in this dissertation, the majority of consumers is rather unaware of the relationship between individual (diet) behavior on collective behavior and the environment. This is especially so for issues like resource depletion and climate change, since negative outcomes are only visible over time (Jager, 2000). Furthermore, uncertainty about (the seriousness of) environmental issues leads to a either an overestimation of resources or a justification for over-consuming (Jager, 2000). Also, some consumers might not be intellectually capable of understanding the issue and the relationship, or they might not be financially capable to transition to a more environmentally friendly lifestyle, since, meat substitutes are more expensive than conventional meat. Regarding quality of life, as mentioned before, consumers pay more importance to short-term individual benefits rather than long-term collective well-being (Jager, 2000). In addition to this, consumers perceive long-term collective issues to be beyond their control (Austgulen et al., 2018). Lastly, behavior of others also affects individual behavior since those parties attempt to change one’s behavior, for example by applying social pressure (Jager, 2000).

So, if a hypothetical question was asked like ‘If the neighbor does not change his behavior, why should I?’, the answer to this question is quite straight-forward: because accumulated individual behaviors affects the environment at the macro-level (Jager, 2000). However, at the end of the day, consumers are emotional beings that compare behaviors (reasoned social processing) (Jager, 2000), and most of time, feel the need to conform (Asch, 1955). Social norms, as explained in The Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991), influence intentions and behavior. So, if social norms do not promote sustainable behavior, it is harder for individuals to transition.

2.4. Instigating behavioral change through policy measures

Because of above-mentioned issues on an individual level, governmental measures must be taken in order for individuals to make collective behavioral change. Jager (2000) explains five strategies to develop individual behavioral change that can be incorporated in policy instruments.

First, the provision and (re)arrangements of physical alternatives (Jager, 2000). This first strategy focusses on the fact that one’s physical environment can facilitate and shape behavioral change (Jager, 2000). In the case of reducing meat consumption and increasing purchase of meat substitutes the following could be done: decreasing meat availability (or not provide any at all in certain periods or areas) in stores and increasing the amount of more sustainable alternatives. This will impact purchase behavior because the consumer lacks control over the amount of meat available and one’s opportunity to consume will drop (Jager, 2000). Nonetheless, consumers will look for substitutes to satisfy their needs (Jager, 2000), in this case meat substitutes.

The second strategy aims at regulations and enforcement (Jager, 2000). Enforcement and law-making regarding meat consumption are not likely to be possible solutions. Supervision on limited meat consumption is undoable and criminalization of meat consumption would probably result in illegal meat trading. However, as mentioned before, redefining purpose of land in favor of sustainable agriculture (crops, legumes, fruit, grains) and prohibiting deforestation of land in order to feed livestock or develop grazing lands, would greatly impact the supply side and hence consumption. The third strategy discusses rewarding or punishing behavior with respectively: discounts and subsidies, and, taxes and fines (Jager, 2000). Increasing taxes and lowering subsidies granted to the meat industry will result in a lower availability of meat and higher in-store prices, and probably also in in factories closing down. Price is the biggest determinant of willingness to buy (Apostolidis & McLeay, 2019), hence when it becomes more expensive for consumers to buy meat, they will look for suitable and cheaper substitutes. To further influence this behavioral change on consumer level, consumers should be awarded by discounting sustainable food choices.

Fourth, social and cognitive stimulation like increasing public awareness around the issue and education can motivate consumers to make those necessary dietary choices (Jager, 2000). Consumer behavior is greatly impacted by social norms and customs (Jager, 2000). The absence of social support is one of the main reasons why people do not transition to a more sustainable diet, or relapse into a meat-including diet (Barr & Chapman, 2002). Furthermore, food consumption is often set in a social setting and divergent food choices can cause bitter reactions and social pressure to comply (Frank, 2007). Hence, when consumption of meat substitutes becomes more widely accepted, and/or

influential people with high status promote this behavior, consumers’ will be more likely to replicate this behavior (Jager, 2000). Furthermore, if people are more educated about the root of the problem, intrinsic motivation rises as well in order to change individual behavior (Jager, 2000).

Finally, changing values and morality, hence targeting the conscience of consumers in attempts to intensify altruism in order to collectively make better dietary choices for the planet and future generations (Jager, 2000). When consumers decide to give more importance to the environment instead of own short-term need fulfilment, this will result in lifestyle changes (Jager, 2000). As Jager (2000) states, these five strategies combined, or alone, can be integrated in policy

instruments, which he cites from Klok (1991) as “all means an actor has decided to use to achieve one or more policy goals” (Jager, 2000, p. 92). Three aspects of policy instruments are classified by van der Doelen (1989): directing versus constituting tools, collective versus individual tools, and lastly, restricting freedom or extending freedom tools. In the case of reducing meat consumption and increasing the consumption of meat substitutes, directing policy instruments would be influencing consumers through prices and constituting measures would be educating consumers regarding the topic (Jager, 2000). Concerning choosing between collective and individual measures, governmental policies should focus on collectively influencing the people by (educational) campaigns and

regulational measures (e.g. taxes) (Jager, 2000). Lastly, as mentioned before, restricting freedom and extending freedom tools would go together, as this concerns taking opportunities away, or adding responsibilities (Jager, 2000). In this case, the availability of meat should be reduced, whereas the availability of meat substitutes would have to increase.

However, many governmental policies fail to change behavior because the complex dynamics (herd and habit formation) underlying to behavioral change are not yet fully understood (Jager, 2000).

2.5.

Role of proteins and their sources

The human diet consists of three macronutrients: carbohydrates, fats and proteins. Proteins are especially important to the body as regards:

• Building, repairing and maintaining tissues (Bosse & Dixon, 2012; Frankenfield, 2006; Paddon-Jones, Short, Campbell, Volpi, & Wolfe, 2008; Pasiakos, McLellan, & Lieberman, 2014);

• The production of certain enzymes and hormones (Cooper, 2000; Nussey & Whitehead, 2001);

• The production of immunoglobulins (antibodies) (Li, Yin, Li, Woo Kim, & Wu, 2007; Schroeder & Cavacini, 2010);

• The balance between acids and bases (in order to maintain a proper pH) (Hamm, Nakhoul, & Hering-Smith, 2015; Lamanda, Cheaib, Turgut, & Lussi, 2007); • Maintaining fluid balance in blood by attracting and retaining water (Busher, 1990;

Hankins, 2006);

• Transportation of nutrients throughout the bloodstream (Hashimoto & Kambe, 2015; Levy, Spahis, Sinett, Peretti, Maupas-Schwalm, Delvin, Lambert, & Lavoie, 2007; Seetharam & Yammani, 2003); and

• Providing energy (Berg, Tymoczko, & Stryer, 2002; Carbone, Pasiakos, Vislocky, Anderson, & Rodriguez, 2014; Rui, 2014).

Furthermore, we can distinguish complete proteins from incomplete proteins (Johnson, 2020). The building blocks for proteins are called amino acids, in total we can characterize 22 types of amino acids, consisting of nine essential and 13 essential amino acids (Johnson, 2020). The 13 non-essential amino acids, the body can produce by itself (Johnson, 2020). The nine non-essential amino acids, it has to absorb from food (Johnson, 2020). A complete protein source is a type of source that contains in adequate quantity all nine amino acids the body cannot produce (Johnson, 2020).

Whilst the preferred protein source for most people is meat (Frank, 2007), there are a number of alternative sources of proteins which can replace meat and which are proven to be more

environmentally friendly and healthier, such as plants, insects and cell-based meat (Tuso, Ismail, Ha, & Bartolotto, 2013).

A plant-based diet is one that relies on the consumption of legumes, nuts, seeds, grains and fruit (Nadathur, Wanasundara, & Scanlin, 2016). Hence, it excludes all animal-derived foods, and protein are only extracted from non-animal sources.

Entomophagy is the consumption of insects, the word is derived from the Greek word éntomos (insect) and phăgein (eating) (Ferranti, Berry, & Jock, 2019). It is a common practice in many cultures to consume insects (Shockley & Dossey, 2014). Especially poor countries, particularly in Africa, include insects in their diet (Shockley & Dossey, 2014). The manner of consumption varies across regions, preferences and sociocultural significance (Shockley & Dossey, 2014). However, in Western societies (e.g. the United States, Europe) taboos have been established on entomophagy in the past and present. However, interest and cultural acceptance are on the rise (Shockley & Dossey, 2014). In addition to this, insects have been incorporated in a variety of food products and consumers are often unaware of the fact they are consuming insects (University of California Riverside, n.d.).

Cultured meat is the production of meat using in-vitro cell culture (MosaMeat, n.d.).

The production process is as follows: muscle tissue from the animal is extracted under anesthesia and myosatelite cells4 are isolated (MosaMeat, n.d.). These cells are then separated into muscle cells and

fat cells (MosaMeat, n.d.). Next, individual cells are removed from the muscle cell and then placed together in a bioreactor with nutrients and natural growth factors5, in order to create the animal-like

environment and grow (MosaMeat, n.d.). When cultured, the cells divide and about one trillion cells can be grown (MosaMeat, n.d.). Eventually, the cells will naturally merge and form myotubes6 , which

are then placed in a rig around a gel because muscle cells have the tendency to contract and put on bulk (MosaMeat, n.d.). This results in the creation of a strand of muscle tissue (MosaMeat, n.d.). When all the muscle tissue strands are combined, we achieve meat ready for consumption (MosaMeat, n.d.).

Synonyms of cultured meat used in this dissertation are: • Animal-free meat • Cell-based meat • Clean meat • In-vitro meat • Lab-grown meat

4 Stem cells of muscles that function to regrow muscle when injured (MosaMeat, n.d.) 5 Proteins that regulate cellular function (Brady, Siegel, Albers, & Price, 2012) 6 Primitive muscle fiber, about 0.3 mm long (MosaMeat, n.d.)

2.6. Comparison between plant-, insect- and meat-based diets

Every consumer has their own unique dietary choices, however with the environmental problems we are facing today, consumers need to be aware of their own climate responsibility. By maintaining a sustainable diet, each individual has the opportunity to minimize their environmental impact (Liobikienė et al., 2016). As Vermeir and Verbeke (2006) state, sustainable consumption is an

individual’s decision to incorporate one’s needs, desires and one’s social and/or climate responsibility. A sustainable diet is a diet that has a low environmental impact, one that consists (mainly) of whole7

seasonal and local ingredients which do not result in waste (Sabaté & Jehi, 2019). The most well-known sustainable diets are the Mediterranean, pescatarian and the vegetarian diet (Tilman & Clark, 2014). These diets contain very few or no meat proteins.

As regards previous conclusions made by Hartmann and Siegrist (2017), acceptance of plant-based meat substitutes depends on the type of product and its features, meal context, previous experiences and familiarity. When people are more familiar with the product, people are more open to such consumption, and when unfamiliar participants increased consumption, the liking of the products increased as well (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017). Furthermore, studies showed that meat substitutes were not accepted in all meal contexts (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017). In the timeframe the studies regarding cell-based meat were conducted, the knowledge with people about the existence of this type of product was very scarce (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017). The majority of participants were not willing to try cultured meat and reported willingness to buy was really low (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017). Whilst willingness to consume insects was found to be very low in general, this willingness increased when insects are processed (versus unprocessed) (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017). However, overall, consumers still prefer non-insect products over insect-containing products and initial liking is almost always lower compared to conventional protein products (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017). Although insect-based products are perceived as inferior at first, this does not affect actual liking when the foods are actually tried out (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017). Availability of insect-based products, food

neophobia and familiarity were the biggest barriers into consumption (Hartmann & Siegrist, 2017).

In the next paragraphs we will discuss nutritional value and environmental impacts of these various diets.

2.6.1. Nutritional value

Proteins are both present in plants, insects and meat. As said earlier, proteins can be defined as complete or incomplete.

Meat, fish, eggs and dairy products are considered complete protein sources because they contain all nine essential amino-acids (Johnson, 2020).

Most plants are incomplete sources of protein because they lack at least one of the nine essential amino acids, or do not contain those in sufficient amounts (Johnson, 2020). In addition to this, animal proteins are higher in nutrients like Vitamin B12,Vitamin D, Zinc, and Iron (Cotton, Subar, Friday, &

Cook, 2004; Pawlak, Lester, & Babatunde, 2014; Romagnoli, Mascia, Cipriani, Fassino, Mazzei, D’Erasmo, Carnevale, Scillitani, Minisola, 2008; Young, 2012). At first sight, this seems to indicate that people who follow a meatless diet might be more vulnerable to deficiencies (Pawlak et al., 2014). Insect protein is quite surprising and could really make a difference in the future. It is high in protein, essential minerals and fats (University of California Riverside, n.d.). As such they are good for high-caloric diets, which is especially important for countries with famine issues (Dossey, 2018).

Some, but not all, insects are considered complete protein sources since protein levels are similar to those of beef and milk (Dossey, 2018).

Thefact that not all amino acids in insect- and plant protein are complete, or that plants do not contain enough proteins, should not be used as justification for an increase in animal-based consumption (Millward, 1999). If one’s diet is balanced and contains a sufficient number of calories derived from low-in sugar foods, there is no risk of protein deficiency (Marcus, 2013).

2.6.2. Environmental impact

2.6.2.1. Plants versus meat

Meat production is conducted with few regards to efficiency (Frank, 2007). First, land suitable to grow crops for feeding the global population, is being used to grow livestock feed (Frank, 2007). In addition to this, the nutrients and calories necessary for humans are being produced very inefficiently in the case of meat production (Frank, 2007). Frank (2007) also explains that disturbingly more land, water, and energy is needed to obtain meat protein, for the same amount of plant protein. In the case of water use that would be a hundred times more water to produce 1 lb8 of animal protein versus producing 1 lb

of vegetable protein (Dutilh & Kramer, 2000). If we would switch from consuming beef, pork, dairy, poultry and eggs to a plant-based diet, we would be able to produce respectively 96%, 90%, 75%, 50% more protein on the same amount of land (Shepon, Eshel, Noor, & Milo, 2018). Consequently, Shepon et al. (2018) conclude this is a form of food waste, as they call it “opportunity food loss” (Shepon et al., 2018, p. 3804). Shepon et al. (2018) also claim that if all animal-derived foods were replaced with plant-based alternatives in the US alone, an additional 350 million people could be fed with the protein which then comes available.

Although plant-based diets are more water- land and energy resourceful, diets that include meat are, in general, less expensive (Frank, 2007). The fact that a meat burger is cheaper than a plant-based burger, raises questions. Nonetheless, answers are provided. First, the meat industry takes advantage of externalities (Frank, 2007). To elaborate: the combination of political influence and interests, government subsidies and affordable, but unbearable living conditions for animals has resulted in artificially reduced meat prices (Scully, 2005). Thereby transferring the real costs to the community as regards traffic, pollution, health and social problems (Frank, 2007). Second, the meat industry benefits economies of scale, especially compared to more sustainable alternatives (Frank, 2007). In addition to this, since meat consumption is an already well-established habit, less marketing and distribution costs are needed compared to vegetarian or plant-based options (Frank, 2007). Third, the vegetarian and plant-based consumer segment is still a niche market which also explains higher prices (Frank, 2000). Lastly, since consumers have a predefined thought regards taste and texture of meat and meat

substitutes, respective companies allocate an abundance of resources towards this one element (Frank, 2000).

However, the meat industry gains much support by governments. The sector is heavily subsidized, despite all environmental concerns. In the European Union, subsidies lie between 28.5 and 32.6 billion euros (Greenpeace, 2019). In a timespan of three years, 60 million euros of this budget has been spent on meat marketing campaigns (Boffey, 2020). As regards the United States, that number is around 38 billion US dollars9, compared to less than 38 million US dollars granted to vegetable and fruit farming

industry (Simon, 2013). Without subsidies, this industry would not be profitable at all, and companies would be unable to pay out dividends (Simon, 2013). Additionally, transferring these subsidies to the plant-based industry could lift people out of poverty, decrease famine in developing countries and water scarcity (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, 2002; Hoekstra, 2012). As Turner (2019) uses as an example: if all animal agricultural land (around 3.5 billion acres) would transition into arable land in favor of fruits and vegetables, we would be able to feed 10 billion people. Additionally, because of artificially reduced meat prices, farmers in developing countries cannot compete and therefore exit the market (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, 2002).

2.6.2.2. Insects versus meat

While we have the perception of meat as a protein-rich source of food, livestock animals are not efficient in absorbing proteins in feed: only about 4% of proteins in feed transition into edible proteins useful for human consumption (Duthil & Kramer, 2000).

If people would replace meat by insects, the impact on the environment would be significantly lower (Dossey, 2018; University of California Riverside, n.d.). Indeed, producing insects is more

environmentally and economically sustainable (Dossey, 2018). This is mostly because insects develop and reproduce very quickly (Dossey, 2018). Compared with livestock, insects are much more efficient as regards transforming feed to edible body mass (Dossey, 2018). To make a comparison: 100 g of crickets equals 21 g of protein versus 100 g of beef/milk equals 26 g of protein, meaning they are both similar regards protein content (Dossey, 2018). However, insects only need a maximum of 2 g of feed for 1 g weight gain, in comparison to cows, who need 8 g of feed for 1 g weight gain (Dossey, 2018). Additionally, some insects are able to feed on waste, while in contrast, humans and livestock cannot (Dossey, 2018). This means that, insects need less feed per gram edible body mass and can consume waste (and thus they do not compete with food suitable for human consumption) (Dossey, 2018). If possible to produce on a big scale, this will result in less waste generation and a more efficient, more environmentally friendly high in protein human nutrition source (Dossey, 2018).

Nevertheless, there is lack of knowledge regarding sustainable farming and which insects would be suited best (Dossey, 2018; University of California Riverside, n.d.).

2.6.2.3. Cultured meat versus traditional meat

Cultured meat is also an alternative to traditional meat protein and could be more sustainable. In-vitro meat can be produced with very few animals and would contribute to feeding the global population, food-borne and nutrition-related diseases, protecting the environment and the wellbeing of animals (Hocquette, 2016). Furthermore, less water, antibiotics and land are needed compared to conventional meat (Askew, 2019).

However, in this industry, trade-offs will need to be made : lower land and water use versus a very big increase in energy use (Mattick, Landis, Allenby, & Genovese, 2015). In short: this could lead to a new industrial phase which entails new trade-offs (Mattick et al., 2015).

Furthermore, current technology has still got some unresolved problems. Implications such as: cell multiplication resulting in cancerous cells, growth factors and hormones needed to culture the cells, the issue of scalability, the very high production cost, and compounds that have to be prepared by the chemical industry which could generate waste, pollution and a lot of energy (Hocquette, 2016). To conclude: the process of creating cultured meat is still in an exploratory phase and further research and development is necessary.

2.7. Hypotheses

Based on the literature study above, two hypotheses have been formed for the new systematic review which will be discussed in chapter 4.

• Hypothesis 1: Consumer awareness of the environmental impact of meat production and consumption will still be very low and comparable to Hartmann and Siegrist’s findings in 2017.

• Hypothesis 2: Consumer attitudes, perceptions and behaviors are expected to be similar to Hartmann and Siegrist’s conclusions in 2017, as regards willingness to reduce meat consumption.

• Hypothesis 3: Consumer attitudes, perceptions and behaviors are expected to be similar to Hartmann and Siegrist’s conclusions in 2017, as regards plant-based protein, insect-based protein or cultured meat.