ANALYSIS OF THE SOCIAL MEDIA

USE BY GHENT UNIVERSITY

TOWARDS STUDENTS DURING THE

COVID-19 CRISIS

Word count: 10,820

Meike Van Eynde

Student number: 01508814

Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Geert Jacobs

A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Multilingual Business Communication

Acknowledgements

I am delighted that last year I chose to do another year of Multilingual Business Communication. It was a year in which I acquired new professional skills, got to know a lot of interesting people and pushed my boundaries. Of course, I would like to thank some people for this.

First of all, I would like to thank my supervisor Geert Jacobs. Not only for his thoughtful advice and constructive feedback but also for allowing me freedom in choosing my thesis topic. It was a pleasure to have a promoter who radiates so much tranquillity.

Secondly, I could not have written this master description without the help of my five interviewees. I really appreciate the time these students made during their busy exam period.

Thirdly, a massive thank you to my boyfriend Stan, my parents, my sisters and my brother for always being so supportive. You were the best support I could have wished for.

A final thank you goes out to my MBC colleagues for making this last year the perfect ending of my study career.

Thank you all.

Meike Van Eynde 19 June 2020

Executive summary

Purpose – This study aims to investigate whether the crisis communication of Ghent University via

social media met students’ expectations during the corona crisis. The social media channels examined are Twitter and Facebook since Ghent University used these channels most often to communicate about Covid-19. This research is relevant because the relationship between social media and health crisis communication remains understudied, especially in an educational setting.

Research questions – First, the main question is to find out if Ghent University fulfilled students’

expectations regarding health crisis communication via social media (RQ1). Second, effective health crisis communication goes hand in hand with effective leadership. That is why this study investigates how Ghent University can use social media to demonstrate effective health crisis leadership (RQ2). The third question explores how Ghent University can use social media to demonstrate effective health crisis

communication (RQ3).

Methodology – To answer RQ1, I conducted five in-depth interviews with students from Ghent

University. Topics included expected information from Ghent University, update speed, channel choice and social media content. RQ2 was tackled by collecting best practices on language use for leaders. Next, these best practices were mirrored to the tweets of the rector of Ghent University. The same method was applied to RQ3. I drew up ten best practices on how Ghent University should behave on social media during a health crisis. Then I compared these best practices with both Twitter and Facebook posts.

Findings – It might be concluded that Ghent University fulfilled most of the students’ expectations via

social media. However, it seems like social media mainly plays a supportive role to communicate updates during a health crisis (RQ1). The rector of Ghent University can show effective health crisis leadership on social media by recognizing and thanking other people, referring to actions, taking personal responsibility, humanizing the situation, emphasizing facts, data and numbers, addressing the emotional aspects, acknowledging uncertainty and using simple syntax (RQ2). Finally, Ghent University should be open and honest, radiate trust, refer to credible sources, listen to the students’ opinions, acknowledge the uncertainty, apply user-friendly language, tell how to protect, create a hashtag, use photos and thank all their stakeholders (RQ3).

Recommendations – Ghent University should spread updates always first via Ufora and webmail, while

Facebook should be the most used social media channel to share updates on. Posts should focus on content where the student is central and if a new measure applies, always explain why this is necessary. The most crucial recommendation for the rector is to address more emotional aspects in future health crises. Besides, Ghent University could create its own hashtag, like #ghentuniversityagainstcorona, so students can easily find information related to the virus from their own educational institution.

Table of contents

Acknowledgements ... I Executive summary ... II Table of contents ... III List of figures ... IV

1 Introduction ... 1

2 Research questions ... 2

3 Literature review ... 3

3.1 Health crisis ... 3

3.2 The relationship between social media and health crisis communication ... 3

3.2.1 The role of social media... 3

3.2.2 Advantages and challenges of social media ... 4

3.2.3 Twitter and Facebook ... 5

3.3 The role of leadership in crisis communication ... 6

3.3.1 The function of language ... 7

3.4 Effective health crisis communication via social media ... 7

3.4.1 Best practices for educational institutions ... 12

4 Research ... 13

4.1 Methodology ... 13

4.2 Results ... 14

4.2.1 Analysis of language use ... 14

4.2.2 Analysis of best practices ... 14

4.2.3 In-depth interviews ... 16

4.2.3.1 Health crisis communication by Ghent University ... 16

4.2.3.2 Health crisis communication via social media ... 17

4.2.3.3 General evaluation... 18

4.2.3.4 Conclusion ... 19

5 Conclusion and recommendations for Ghent University ... 20

6 Limitations and future research ... 23 7 Bibliography ... V 8 Appendix ... VIII 8.1 Collection of tweets ... VIII 8.2 Collection of Facebook posts... XX 8.3 Analysis of Rik Van de Walle’s language use ...XXV 8.4 Analysis of best practices ...XXVI 8.4.1 Twitter ...XXVI 8.4.2 Facebook ...XXIX 8.5 Interview guide ...XXXI 8.6 Summary of in-depth interviews ... XXXIV

List of figures

Figure 1 Who does the public believe in health questions? 9

1 Introduction

Covid-19 is a coronavirus that came alive in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. It can cause respiratory infections with symptoms such as fever, tiredness, and dry cough. 1 out of 6 people infected with the virus become seriously ill and have difficulties with breathing. This infectious disease is spread from person to person via small droplets released by coughing and sneezing (WHO, 2020a). Moreover, Covid-19 can be qualified as a pandemic since it is a novel virus, virulent, and it can be easily transmitted from person to person (Reynolds & Quinn, 2008).

The first Belgian infected with Covid-19 was noted on 4 February 2020. Since then, the virus has spread rapidly throughout Belgium, mainly by tourists returning from skiing holidays in Northern Italy. This led to a Belgian epidemic of Covid-19 cases during March and April 2020 (Info coronavirus, 2020). At the time of writing, no effective vaccine to prevent further transmission of Covid-19 exists.

The novel coronavirus has also had a powerful impact on the Belgian education network. Since 11 March 2020, multiple universities, including Ghent University, have focused on education on a distance due to Covid-19 (Ghent University, 2020a). Lessons and practicals are done remotely and are replaced by digital teaching sessions at least until June 2020. Besides, telework has become the norm for all staff members.

One group of stakeholders severely affected by the unusual measures due to Covid-19 are students. Students represent the largest and one of the most critical group of stakeholders for Ghent University. The consequences for students were quite drastic since all lessons suddenly became digital, presentations had to be given online, and it was no longer possible to meet with their supervisors in real life.

Crises can generate uncertainty, confusion and ambiguity (DiStaso, Vafeiadis, & Amaral, 2015), so effective communication towards students to inform them with current measures during this health crisis is therefore key. One way of reaching this group is via social media. Bratu (2016) underlines that social media can be adopted to more effectively handle a critical situation. In times of crisis, stakeholders tend to make more use of social media to have immediate access to information and recent updates (DiStaso et al., 2015). These findings are consistent with Roshan, Warren, & Carr (2016), who state that social media is deployed by organisations to provide quick and convenient access to crisis information. Hence, this paper aims to explore whether Ghent University has communicated effectively via social media towards students during the Covid-19 crisis. The social media channels that will be investigated are Facebook and Twitter, as these are most used to communicate about the crisis.

The remainder of the paper is set out as follows. First, I will discuss the research questions, followed by a comprehensive literature review. Second, this paper will analyse Rik Van de Walle's language use, Twitter and Facebook posts from Ghent University and in-depth interviews with students. To conclude, specific recommendations for Ghent University will be given, together with some limitations and inspiration for future research.

2 Research questions

This research is both scientifically and socially relevant. First, there is a dearth of research on how stakeholders use technology to deal with health crises such as a pandemic (Gui, Kou, Pine, & Chen, 2017). Also DiStaso et al. (2015) claim that the relationship between social media and health crisis communication remains understudied. Moreover, they encourage research that examines what type of crisis response strategy is appropriate to preserve stakeholder’s trust. In addition, limited research has investigated messages on social media during a health crisis and if the content of these messages enable individuals to understand the crisis and respond effectively (Vos & Buckner, 2016). Guidry, Jin, Orr, Messner, & Meganck (2017) suggest exploring Facebook next to Twitter since this is also a significant and influential platform. Finally, there is little guidance in literature on the connection between health crisis communication and social media in an educational setting.

A mentioned before, this paper is also socially relevant. It is the first time in history that Ghent University is experiencing such an unexpected health crisis, a situation they might not have been prepared for. Nevertheless, delivering up-to-date information via social media to stakeholders can reduce their stress level because it eliminates some of the uncertainty (Utz, Schultz, & Glocka, 2013). Next to that, recommendations formed in this paper may stimulate Ghent University to modify and improve their health policy. At the time of writing this paper, the crisis is still in full swing. This allows to monitor all relevant information about Covid-19 in real-time.

The purpose of this paper is to address the gaps in the literature by carrying out a qualitative analysis. This analysis will check whether the crisis communication of Ghent University via social media met students’ expectations during the corona crisis. Recommendations for Ghent University will be formed based on a literature review and in-depth interviews. Consequently, this leads to the following research question:

Did Ghent University meet students’ expectations concerning health crisis communication via social media during the Covid-19 crisis?

In addition, this paper will search for best practices for effective leadership and effective health crisis communication through the literature review. Therefore, two additional research questions can be formed:

How can an educational institution such as Ghent University use social media to demonstrate effective health crisis leadership?

How can an educational institution such as Ghent University use social media to demonstrate effective health crisis communication?

3 Literature review

3.1 Health crisis

In general, a crisis can be defined as “an unpredictable event that threatens important expectancies of stakeholders and can seriously impact an organisation’s performance and generate negative outcomes” (Coombs, 2014, p. 3). However, in this case, the “unpredictable event” is the ongoing disease Covid-19, so a more specific definition of a health crisis should be used. Peralta (2008) describes a public health crisis as “a sequence of events following a public health threat, where the limited time available for deciding and the large degree of uncertainty leads to overburdening the normal response capacity and undermining of authority” (p. 2). Besides, she states that all health crises are also communication crises.

According to Peralta (2008) and several other authors (e.g. DiStaso et al., 2015; Gui et al., 2017; Holmes, Henrich, Hancock, & Lestou, 2009), one of the main characteristics of a health crisis is the presence of uncertainty, which leads to fear and panic. Other key elements of a health crisis are that there is little known about the disease, no cure exists, and there is a lack of trustworthy information (Peralta, 2008). Examples of past health crises are Ebola and the Zika virus (Gui et al., 2017; Guidry et al., 2017).

During a crisis, one can make a distinction between companies according to the responsibility they bear for the crisis. Coombs and Holladay (2002) introduce three clusters of crises: the victim cluster,

accident cluster and preventable cluster. The first one contains crises where stakeholders believe

the organisation holds little responsibility for what happened such that the organisation is a victim of the crisis. The accident cluster includes crises that are considered as unintentional and uncontrollable, so the organisation still bears relatively little responsibility. However, a crisis in the preventable cluster incorporates crises where the organisation is supposed to be consciously involved in the behaviour that caused the crisis. In this case, the organisation is deemed to be responsible for the crisis.

It should be clear that Ghent University and the Covid-19 crisis belong in the victim cluster. In other words, Ghent University is undoubtedly a victim of the Covid-19 crisis and bears no responsibility for the emergence of this crisis. Since the perception of an organisation’s responsibility is positively related to the reputation damage (Schultz, Utz, & Göritz, 2011), it is unlikely that Ghent University will suffer major reputational damage as a result of this crisis.

3.2 The relationship between social media and health crisis

communication

3.2.1 The role of social media

Social media can be defined as “online practices that utilize technology and enable people to share content, opinions, experiences, insights, and media themselves” (Lariscy, Avery, Sweetser, & Howes, 2009, p. 1). Examples of social media are Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. While social media mostly

serves as a popular platform to share pictures or information with friends, or to engage in marketing as an organisation (Roshan et al., 2016), these sites also fulfil several other roles during a crisis.

According to Guidry et al. (2017), social media is playing a critical role in the dissemination of information in times of crisis. Moreover, they argue that social media has resulted in new ways of communicating with stakeholders by offering the opportunity to engage in direct dialogue with a company. Also Roshan et al. (2016) state that social media can support organisations to respond quickly to stakeholders’ questions and concerns, thus better serving stakeholders’ crisis needs and providing greater clarity. The fact that social media has met the public’s demand for personal and direct communication makes social media indispensable for crisis management (Bratu, 2016). In short, social media allows organisations

to inform their stakeholders and to directly communicate with the public during a crisis (Lin,

Spence, Sellnow, & Lachlan, 2016; Utz et al., 2013).

In addition, social media fulfils a social role. It enables the public to connect (Smith & González-Herrero, 2008), and it also provides emotional support (Jin, Liu, & Austin, 2014). In line with Vos & Buckner (2016) findings, individuals can use social media to make sense of an emerging crisis. Next to that, social platforms can serve as a tool to provide aid in emergency response (Lin et al., 2016). Besides, younger people are more active on social media during a crisis than elder people (Schroeder, Pennington-gray, Donohoe, & Kiousis, 2013), which shows the importance of the use of social media by Ghent University towards its students during the Covid-19 crisis.

Furthermore, social media plays a crucial role in crisis leadership. Thanks to the swift, two-way communication of these platforms, organisations such as universities can promptly reach students without being filtered by other media (Brennan & Stern, 2017). On top of that, these authors distinguish three ways to adopt social media in crisis management. First, leaders can use it bottom-up as a situational awareness tool. A second approach is to use it top-down like an official communication tool. Lastly, they can use social media multi-way, so there is a dynamic interaction.

3.2.2 Advantages and challenges of social media

As reported by Roshan et al. (2016), an organisation can benefit from social media in three ways. Firstly, it has allowed organisations to engage in two-way communication, in the sense that they have an active relationship with the public in which they listen and respond to their concerns. This switch from one-way to two-way communication was also noted by Gui et al. (2017). Secondly, social media provides instant access to real-time data, which keeps the public up-to-date. Thirdly, social media platforms are a cost-efficient way to communicate with stakeholders. Another advantage of social media is that they support a rapid correction of rumours so that rumours do not develop into facts, and the crisis does not escalate (DiStaso et al., 2015). Social media is also more dialogic, interactive and faster than traditional media (Schultz et al., 2011). Moreover, the latter authors argue that these platforms are able to reach large audiences. To sum up, Roshan et al. (2016) state that social media are an interactive tool that can reach a broad audience and enable organisations to respond quickly to stakeholder messages.

Nevertheless, social media also faces some challenges. According to Gui et al. (2017), social platforms have different roles and responsibilities, which can lead to problems such as data overload, insufficient

access to information, concerns with reliability and a lack of trust. Besides, there is an organisational lack of control since businesses cannot determine what is said on social media, which increases an organisation’s vulnerability (Roshan et al., 2016). Next to that, traditional news sources, such as newspapers or TV news programs, are regarded as more credible than social media (Utz et al., 2013). However, this contradicts the findings of Schultz et al. (2011) as they believe social media is very credible. Social platforms can also quickly convey dubious and inaccurate information, and inefficient social media use can worsen a crisis (DiStaso et al., 2015). They even state that dissatisfied stakeholders going viral can worsen the trust, credibility and reputation towards an organisation. This corresponds to Coombs’ (2014) findings that failing to tackle a crisis online may arouse suspicion among stakeholders, which could trigger them to use other sources of communication.

3.2.3 Twitter and Facebook

The two channels that will be analysed in this paper are Twitter and Facebook since these social media platforms are most used by Ghent University to communicate about the Covid-19 crisis. Besides, Twitter and Facebook can assist people affected by the crisis to develop situational awareness, to search for help and to recover from what happened (Gui et al., 2017).

Twitter, launched in 2006, is a free microblogging site and application on which users can share short

messages of maximum 280 characters, also referred to as tweets (Guidry et al., 2017). The goal of this social networking site is to show what people are talking about right now. Today, Twitter has over 300 million active users worldwide (Twitter, 2020). Since Suh, Hong, Pirolli, & Chi (2010) suggest there exists a positive relationship between the reach of tweets and the number of followers, Twitter has a lot of potential to reach many people. Thanks to the platform’s increased popularity, more and more organisations work with Twitter to communicate with their audience (Vos & Buckner, 2016). By consequence, Twitter can serve as an effective information and communication platform, especially during a crisis (Jin et al., 2014).

According to Schultz et al. (2011), Twitter can be used more efficiently to engage in two-way communication compared to traditional media. Moreover, they claim that the medium used in a crisis, i.e. Twitter, newspaper or a blog, is more important than the message content. For example, it turned out that crisis communication via newspapers and blogs caused less positive reactions than via Twitter. In addition, the authors suggest that short tweets ensure stronger communication. A preference for short social media posts was also found by DiStaso et al. (2015).

While Twitter messages have to be concise (Guidry et al., 2017), this is not the case on Facebook. The platform was created in 2004 and has over 2.6 billion monthly active users, which makes Facebook the most prominent social network worldwide (Statista, 2020). Facebook can be used to share pictures, articles, videos etc. with your Facebook friends, who can then like the posted content, share it or comment on it (Facebook, 2020). As reported by Guidry et al. (2017), health organisations should focus on sending positive and solution-based messages to the public instead of negative or problem-based messages. They claim that too many negative posts on Facebook can hamper stakeholders in receiving the message intended for them. However, DiStaso et al. (2015) argue that organisations should avoid

posting too many sympathetic Facebook posts in the event of a health crisis because this could harm the image of the organisation even more. Nevertheless, this mainly applies to companies in the accident or preventable cluster (cf. 3.1 Health crisis), which is not the case for Ghent University. Furthermore, Utz et al. (2013) showed that the medium used during a crisis, i.e. Facebook, Twitter or an online newspaper, is more important than the crisis type. It was found that crisis communication via Facebook affected a company's reputation better than crisis communication via an online newspaper.

3.3 The role of leadership in crisis communication

Crisis leadership is a role not to be underestimated. According to Wooten & James (2008), crisis leadership consist of more than just communicating effectively. They define leadership competencies as “the knowledge, skills, or abilities that facilitate one’s ability to perform a task” (p. 354). More specifically, the authors describe the following crisis leadership competencies: communicating effectively, sustaining a productive business culture, decision making, ensure the well-being of its stakeholders, making rapid decisions under pressure, creating organisational opportunities, thinking creatively, developing human capital, and learning and reflection. They even claim that effective crisis leadership results in an organisation that is better off after a crisis than it was before.

Also Brennan & Stern (2017) state that crisis communication is more than only making decisions. Apart from this, leaders need to maintain an organisation’s legitimacy and credibility by communicating these decisions well. Besides, they argue it is especially difficult for universities to deal with a crisis since they do not have the time to study a problem thoroughly or involve large numbers of stakeholders like they usually do. Instead, information is often inaccurate, while decisions must be made briskly. Gainey (2010) confirms that effective crisis management is not an event but a process. Even though leaders have often prepared themselves for a crisis, they also need to learn from the past by analysing their own and other crisis experiences.

Brennan & Stern (2017) identified six core leadership tasks, namely preparing, sense-making, decision-making, meaning-decision-making, terminating and learning. Preparing is about creating framework conditions for cooperation and effective and legitimate action in crisis situations, such as planning, organising and exercising. Sense-making refers to the establishment of an appropriate interpretation of a changing, ambiguous, and complicated situation. Weick, Sutcliffe, & Obstfeld (2005) define sense-making as “turning circumstances into a situation that is comprehended explicitly in words and that serves as a springboard into action”(p. 409). In this phase, a leader should understand what is happening right now, but also what the consequences are for the organisation and the different stakeholders. A third core leadership task is decision-making. This implies that the leader has to make crucial decisions, set priorities and adjust its policies. Next, meaning-making ensures the public understand what has happened and how to put in a broader perspective. The words of managers can bring hope and courage if they show empathy and caring leadership. Terminating is another important and necessary task in which the leader needs to find the right time and means to end a crisis. The last task, but maybe the most important one, is learning. Learning from the past can strengthen safety, performance and capabilities in the future.

To conclude, Brennan & Stern (2017) state that higher education leaders should adopt a crisis mindset. This means “quickly acknowledging that a crisis exists, having a bias towards taking the initiative and moving rapidly, working to make sense of what has happened and sharing that understanding broadly, becoming comfortable with making decisions and communicating without complete information, and empowering people to act and communicate without onerous prior approvals” (p. 130).

3.3.1 The function of language

Just as Brennan & Stern (2017), Vásquez (2020) believes that effective leadership is especially important during times of crisis. In a YouTube lecture for the Association for Business Communication, she discusses the role of language in leadership and crisis communication during the Covid-19 crisis. According to this professor of applied linguistics, effective leadership corresponds to the proper use of language and communication. This is why she formulated eight suggestions that show effective leadership.

Firstly, leaders should recognize and thank other people such as the public, colleagues and health workers during a crisis.

Secondly, it is essential to refer to decisive collective actions being taken. One linguistic recommendation for this is to use the word “we” frequently. Managers have to show that everything that can be done is being done.

Thirdly, a leader should take personal responsibility and prove to the public that he or she is taking action himself/herself.

Next to that, the person guiding the crisis should humanize the situation in order to make people feel like the crisis is manageable.

Another valuable advice is to emphasize facts, data and numbers to reassure the public. Vásquez (2020) also recommends addressing the emotional aspects of a crisis.

Furthermore, a leader should not act like he or she knows everything. It is essential to acknowledge uncertainty and to refer to experts.

Finally,simple, straightforward and uncomplicated syntax should be used.

The leader in the case of Ghent University is Rik Van de Walle, rector since 1 October 2017 (Ghent University, 2020b). Later in this paper, the language use of some of Rik Van de Walle's Twitter posts will be analysed based on these findings in literature.

3.4 Effective health crisis communication via social media

In order to be able to answer the research question, it is also necessary to examine what effective crisis communication in the event of a health crisis entails.“Effective communication can guide the public, the news media, healthcare providers, and other groups in responding appropriately to outbreak situations and complying with public health recommendations” (Reynolds & Quinn, 2008, p. 14). According to

Smith & González-Herrero (2008), there is so much information available just at the push of a button these days, which makes crisis communication more important than ever. This is in line with Holmes et al. (2009) observations’ that effective communication during an infectious disease outbreak is crucial. One obvious goal of crisis communication is to help manage the health crisis such that people act on expert advice (Holmes et al., 2009), but also to reduce and contain harm (Seeger, 2006). In addition, crisis communication should ensure that an organisation’s reputation and the trust of stakeholders is restored (Utz et al., 2013). When a health crisis occurs, crisis communication should contain information that encourages people to make sense of the crisis and respond effectively (Vos & Buckner, 2016), i.e. how to prevent further spread of the virus. Besides, incorporating social media use in an organisation’s crisis decision-making policy is essential (Lin et al., 2016).

Sturges (1994) has defined three categories of information that can be disseminated to stakeholders during a crisis. First, he distinguishes instructing information. This kind of information gives stakeholders instructions on how to protect themselves physically. Applied to the Covid-19 crisis, instructing information would include protective measures such as regularly and thoroughly cleaning your hands, maintaining social distance or avoid touching your mouth (WHO, 2020b). Next to that,

adjusting information “helps stakeholders cope psychologically by expressing sympathy or explaining

the crisis” (Roshan et al., 2016, p. 351). For example, Ghent university giving more information about the emergence of Covid-19 could be seen as adjusting information. The third type of information is

internalising information. This helps stakeholders to develop an image of the organisation.

Based on literature, this paper formulates ten best practices for any organisation on how they should behave on social media during a health crisis. These practices will be applied to educational institutions, such as Ghent University, in the following section.

1) Be open and honest

One important rule in crisis communication is the practice of openness and honesty. Being open about the risks of a health crisis can promote an environment where both the public and agencies accept responsibility to cope with the different health risks (Seeger, 2006). According to this author, an effective crisis communicator is honest, candid and open when addressing the public. He describes honesty as “not lying”, while “candour refers to communicating the entire truth as it is known, even when the truth may reflect negatively on the agency or organisation. Openness in crisis communication refers to a kind of accessibility and immediacy that goes beyond even a candid response” (p. 239). Also Covello (2003)stresses the importance of being truthful, frank, open and honest. He states it is crucial to fill information vacuums and to tell the truth instead of exaggerating or minimizing the level of risk. In case the organisation is in doubt about certain information, he recommends to share more information instead of less such that people do not think anything is concealed.

2) Trust is key

A significant body of crisis communication research underlines that trust is an essential ingredient in crisis communication (e.g., Gainey, 2010). Moreover, it seems like trust is the new

currency, and people only accept transparent and authentic company messages in a human tone (Smith & González-Herrero, 2008). Trust is a key element of persuasive communication and can be expressed through expertise, dedication, openness and empathy (Reynolds & Quinn, 2008). DiStaso et al. (2015) define trust as “the shared group perception that the other party will be open, honest, fulfil its responsibilities, and refrain from exploiting others” (p. 224). Effective health crisis communication therefore reduces uncertainty and promotes trust (Holmes et al., 2009).

As reported by Guidry et al. (2017), trust is critical to make sure the public does not ignore health information or essential guidelines. They point out that the level of trust will dwindle if there is a lack of coordination, late sharing of information, disagreement among professionals, poor risk management and reluctance to acknowledge risks. Instead, they recommend discussing negative aspects of infectious diseases to establish trust. Also Reynolds, Deitch, & Schieber (2007) highlight that trust can only be built by disseminating scientific and accurate information about the pandemic in a clear and timely manner. Besides, an organisation should involve its stakeholders in making important decisions in such a way that they feel respected and trust the organisation (Covello, 2003).

3) Use credible sources

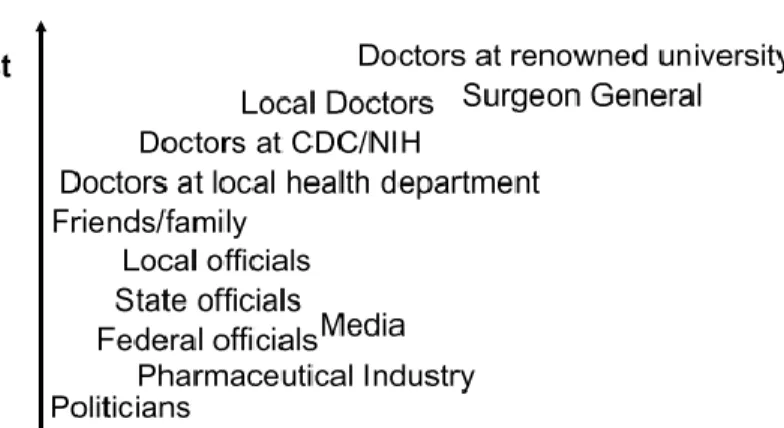

A third best practice is to refer to credible sources in social media posts since source credibility is crucial for the interpretation and acceptance of information (Lin et al., 2016). While credibility “is the confidence stakeholders have in the validity and veracity of the received message” (p. 224), source credibility describes “attributes of the communicator such as expertise, attractiveness, trustworthiness, or power, which, if present, enhance the believability of the transmitted information for message recipients” (DiStaso et al., 2015, p. 224). According to Peralta (2008), there exists a positive relationship between the level of trust and source credibility in a health crisis (figure 1). Her research showed that doctors at a renowned university are considered the most credible source, while politicians seem the least credible.

This does not fully reflect Holmes et al. (2009) findings that individuals especially see their friends and family as a reliable source. However, they also state that medical advisors or institutions such as public or health agencies can be seen as equally reliable if an individual has established a relationship with them. In addition, these authors argue that it is especially important to build partnerships with journalists during a health crisis because mass media also plays an essential role in the spread of information. In the same way, Covello (2003) advises to collaborate with other credible sources and to show this to the public by citing them. In fact, these partnerships should already be made in advance (Gualtieri, 2010). It is therefore important to prevent the public from using less credible sources by ensuring that crisis communication is honest, fair and receptive (Bratu, 2016). In order to be perceived as a credible source, both health organisations and government agencies should be present on social media with their own official account (Lin et al., 2016).

4) Demonstrate empathy

Furthermore, the credibility of a message increases if crisis communication reflects empathy, compassion and concern (Seeger, 2006). Covello (2003) suggests to listen to your public and to discover what they think, feel and want. In addition, he states it is useful to work with communication channels that promote dialogue, listening, participation and feedback. In other words, reacting quickly to your stakeholders’ preoccupations shows concern (Utz et al., 2013). Moreover, an organisation should disseminate messages that allay fears in exchange for public trust (Gualtieri, 2010; Guidry et al., 2017).

5) Acknowledge the uncertainty

Another best practice in health crisis communication is to acknowledge uncertainty (Holmes et al., 2009). During a pandemic, people value information about the crisis even more since health risks are extremely uncertain (Reynolds et al., 2007). According to Seeger (2006), it is better for an organisation to admit they do not have all the facts yet instead of creating their own facts that may not be true. In this sense, organisations should monitor and correct misinformation on their platforms (Guidry et al., 2017). Lin et al. (2016) argue that rumours are a common type of misinformation on social media. They may arise due to a lack of information from traditional sources, or because there is not enough accurate information.

In line with Peralta's (2008) findings, uncertainty can be reduced by proper communication, which is the result of careful preparation. Organisations should have a prepared plan on how to tackle each type of crisis, so also for a health crisis (Gualtieri, 2010). Preparation is key, and this is only possible if a company has an integrated communication strategy that makes it possible to spread consistent messages through different channels (Utz et al., 2013). Moreover, crisis managers will need to determine how they will use various social media channels to disseminate important health information (Smith & González-Herrero, 2008).

6) Communicate clearly, on time and two-way

The way a company gets its message across is also very relevant. They should carefully create messages to communicate the necessary information concisely (Gualtieri, 2010). For example, Covello (2003) recommends using non-technical language appropriate for each target group. In that way, the chance of speculation will be reduced during an influenza pandemic (Reynolds et al., 2007). It is in the organisation's advantage to communicate with stakeholders on time via social media. Otherwise, there is a risk that rumours or negative messages will emerge on social media that will harm the company's reputation (Roshan et al., 2016). Also Lin et al. (2016) claim that people active on social media prefer quick social media updates since these are perceived as more relevant or as breaking news. Being fast with new information updates is therefore a key element of effective health crisis communication. Furthermore, an organisation should engage in two-way crisis communication with the public, so they can listen and respond to stakeholders’ concerns (Lin et al., 2016; Roshan et al., 2016).

7) Tell your stakeholders how to protect themselves

One essential element of health crisis communication is to tell stakeholders how they should protect themselves, their colleagues and their family and friends (Reynolds et al., 2007). Moreover, a company should give specific instructions on how to prevent yourself from getting the virus, also called instructing information (Sturges, 1994). This is the only way to maintain control of the infectious disease (Covello, 2003).

8) Create your own hashtag

Another suggestion is to create your own company hashtag during a health crisis. This hashtag can be used for the transmission of official information or to update or warn your audience (Lin et al., 2016). By consequence, stakeholders have instant access to the most critical messages by merely looking up the organisation’s hashtag.

9) Use imagery

Guidry et al. (2017) believe that crisis communication on social media is most effective if visual imagery is used. A company should use graphics, photos or other imagery to make the message even more apparent to the audience (Covello, 2003). The latter author states that visuals stay longer in people’s memories, which is especially valuable in stressful situations where the processing of information can be hindered. Besides, a message including a photo or video will reach more people on Facebook than a non-visual post (Social Lemon, 2017).

10) Thank your stakeholders

Last but not least, companies should thank their stakeholders for the efforts they have made, also during the post-crisis (Smith & González-Herrero, 2008). Thanking those who helped the organisation is also a form of effective crisis leadership (Vásquez, 2020).

3.4.1 Best practices for educational institutions

The above best practices can also be applied to educational institutions such as Ghent University. Moreover, this section will tell how Ghent University (organisation) should have used social media for its students (stakeholders) during the Covid-19 crisis (the health crisis).

First of all, Ghent University has to be open and honest towards its students. It is essential to share all the information they know about Covid-19 as quickly as possible on social media, knowing that students are more likely to be on social media than older people (Schroeder et al., 2013). Secondly, Ghent University should radiate trust. They can do this by discussing scientific, accurate and truthful information about the pandemic, but also by involving students in the decisions they make.

Next to that, Ghent University should refer to credible sources in their social media posts, such as medical experts, health agencies or doctors (from the university), but definitely not to politicians. Besides, this educational institution should build partnerships with journalists in order to disseminate as much information as possible about the Covid-19 measures. This can be journalists from VRT1, but it

might as well be journalists from popular platforms among students. Another recommendation is to

listen to the students’ opinions and try to incorporate their concerns as much as possible into crisis

management. Entering into a dialogue with someone from the university can calm down students. Furthermore, Ghent University has to acknowledge the uncertainty surrounding the Covid-19 virus. Since the beginning of the crisis, a lot of questions have arisen among students: what will happen with the exams? Will I be able to finish my internship? And what about the scheduled appointments with my supervisor? The university should try to give as many answers as possible, but they also have to dare to admit when they do not have certain information yet. In this context, it is crucial to handle misinformation on social media and to erase this type of information as soon as possible. In addition, uncertainty is also outweighed by a clear social media plan in which consistent messages are spread. The university should also make sure that they apply user-friendly language in their social media posts and to keep it short. In order to avoid rumours, it can be advantageous to communicate quickly to students. Additionally, Ghent University has to give specific instructions to students on how to protect themselves and their families from Covid-19, both physically and mentally. Furthermore, it can be interesting to create a hashtag of Ghent University, like #ghentuniversityagainstcorona, so students can easily find information related to the virus from their own educational institution. Another recommendation is to use photos or other imagery with social media posts, to make the posts more attractive and eye-catching. Lastly, Ghent University should thank all their stakeholders, not only the students, for everything they did during the health crisis.

4 Research

This study aims to find out if Ghent University has communicated effectively towards students via social media during the Covid-19 crisis. To do so, I will use three methods. First, this section will analyse the language use on Twitter of Rik Van de Walle, rector of Ghent University. Second, an analysis of Twitter and Facebook posts will be carried out, based on ten best practices from the literature review. Third, a qualitative approach will be used to interview students from Ghent University.

4.1 Methodology

To examine the health crisis communication strategy carried out by Ghent University during the Covid-19 crisis, I collected 69 tweets (Appendix 8.1) and 28 Facebook posts (Appendix 8.2) from the official Ghent University accounts. All selected messages were related to Covid-19 and posted between 11 March 2020 and 15 May 2020. These posts were then used as the basis for the following three research methods: analysis of language use by the rector of Ghent University, analysis of Twitter and Facebook posts following the best practices, and five in-depth interviews.

Since effective university leadership is linked to effective crisis communication on schools (Brennan & Stern, 2017), the first step was to examine whether Rik Van de Walle’s activity on Twitter can be considered as effective leadership. Moreover, out of the 69 tweets collected from the Twitter page of Ghent University, 15 tweets were retweets from Rik Van de Walle. It was then checked whether these

retweets met Vásquez’ (2020) eight suggestions regarding good language use for effective leadership

(3.3.1 The function of language).

Secondly, it was investigated which Twitter and Facebook posts met the ten best practices from the literature review (3.4.1 Best practices for educational institutions). In this way, it was possible to see which best practices were most frequently used and which best practices are lacking in the communication policy of Ghent University.

Thirdly, a qualitative research was conducted in the form of online in-depth interviews. The interviews took place via the communication tool Skype due to the Covid-19 measures. This qualitative method was chosen because in-depth interviews can provide very detailed information without being influenced by others, as is the case with focus groups (Into the minds, 2020). Besides, I believe students feel more comfortable in sharing their opinions one-to-one than in a group of strangers, given the fact the interviews were conducted on a computer screen.

Therefore, I carried out five in-depth interviews with students from Ghent University between 28 and 30 May. Since students were in the middle of their exams and consequently did not have much time, the interviews were limited to roughly 30 minutes. Participants were asked an average of 28 open-ended questions about health crisis communication by Ghent University and health crisis communication via social media. More specifically, questions were asked about which channels they prefer for health crisis communication and what is important in terms of message content. Additionally, some Twitter and Facebook posts were shown to participants in order to find out what feelings these posts aroused. The complete interview guide can be found in Appendix 8.5.

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Analysis of language use

I analysed 15 tweets from the rector of Ghent University based on Vásquez’ (2020) eight suggestions regarding effective leadership (Appendix 8.3). At first glance, it became clear that each suggestion was met at least once. The rector most often fulfilled the following recommendations: using simple, straightforward and uncomplicated syntax (100%), humanizing the situation (87%) and referring to actions (80%). Next, the rector does not act like he knows everything and acknowledges uncertainty in more than half the tweets (53%). He also takes personal responsibility in 40% of the Twitter posts. Further, Rik Van de Walle recognizes and thanks people (colleagues, teachers, etc.) and emphasizes facts, data or numbers in respectively 27% and 20% of the tweets. Lastly, he addresses emotional aspects in only 7% of the Twitter posts.

Even though only 15 tweets were analysed, the rector met each suggestion at least once. This can be regarded as a first indication of effective leadership. Next to that, four out of eight recommendations were used in more than half of the tweets. This means the rector of Ghent University made excellent use of simple and clear language in his tweets. He knew how to humanize the Covid-19 crisis and often referred to decisive actions being taken. Moreover, Rik Van de Walle frequently used the word "we" and showed through his tweets that Ghent University did everything within its possibilities.

However, there is some room for improvement in thanking people and emphasizing facts, data or numbers. Mainly the use of numbers is missing in his posts. Nevertheless, a real concern is to address more emotional aspects, such as the lack of social contact due to online classes. The rector humanized the corona crisis very well. Still, he could go a little deeper into the emotional aspect, knowing that many students can use some additional mental support during the crisis. Altogether, the rector of Ghent University did not underestimate his role as crisis leader and definitely performed effective health crisis leadership via Twitter during the Covid-19 crisis.

4.2.2 Analysis of best practices

In order to see which social media posts of Ghent University met the ten best practices from the literature review, I analysed all 69 Twitter and 28 Facebook posts (Appendix 8.4). I will first discuss the results of the Twitter posts, followed by the results of the Facebook posts. To conclude, I will make a comparison between these two social media channels.

Nine out of ten best practices were applied at least once in the Twitter posts. More specifically, there were no less than four best practices that were fulfilled in all 69 tweets: being open and honest (100%), radiating trust (100%), communicating clearly (100%) and using imagery (100%). Since I had the feeling that Ghent University shared all the information they knew on their social media accounts, all posts were regarded as open and honest. When a post radiated expertise, dedication, openness or empathy, or when scientific information or negative issues were shared, the item was considered to be trustworthy. Consequently, every tweet that was seen as open was also seen as reliable. In addition, all Twitter posts

applied user-friendly language, so Ghent University definitely communicated clearly. Every tweet was also accompanied by a picture or other imagery, which made the posts even more appealing.

Next to that, Ghent University was also very successful in acknowledging uncertainty (88%). They tried to give as many answers as possible and counteracted misinformation by sharing numerous links containing more information. Almost half of the tweets referred to a credible source (43%), such as professors or researchers from Ghent University. In addition, 29% of the Twitter posts reflected some empathy, compassion or concern with the students. Ghent University also mentioned in 13% of the posts how students could protect themselves against the coronavirus, both physically and mentally. However, the focus was mainly on the mental well-being of the student. Besides, barely 9% of the tweets contained a thank-you message. There was one best practice that was not met, namely the creation of an own Ghent University hashtag (0%).

When it comes to Facebook posts, similar results were found. Again, the same best practices were implemented in all 28 Facebook posts: being open and honest (100%), radiating trust (100%), communicating clearly (100%) and using imagery (100%). Furthermore, 82% of the posts acknowledged uncertainty by disseminating the most important information about Covid-19. More than one-third of posts demonstrated empathy (36%) or referred to a credible source (32%). Then there was a joint penultimate place in the number of posts that mentioned how students should protect themselves (14%) and posts in which Ghent University thanked its stakeholders (14%). Unfortunately, Ghent University has not created its own hashtag on Facebook either (0%).

Although there was certainly overlap between the Twitter and Facebook posts, some differences can be noticed. First of all, there were a lot more messages posted on Twitter than on Facebook between 11 March and 15 May 2020. It seems like Twitter is more often used as a platform to provide short and frequent updates than Facebook. Next to that, Ghent University rather used Facebook to share videos, while on Twitter, they only used photos. This again shows that Twitter is a platform where content is consumed very quickly, and there is no time for videos.

When comparing the results of the analysis, it was striking that these were very similar, except for two best practices. Ghent University referred more to a credible source on Twitter (43%) than on Facebook (32%). In addition, they used Facebook more as a platform to demonstrate empathy (36%) than Twitter (29%). This may be coincidental, but in general it seems like there is less space and time on Twitter to share empathetic posts than on Facebook. Besides, it seems that the use of credible sources is more important on Twitter than on Facebook.

In conclusion, Ghent University has met nine out of ten best practices on both social media channels, which is undoubtedly an outstanding result. The content of the posts was candid and trustworthy, and they always communicated very clearly in terms of language. Moreover, Ghent University used a picture or other imagery with every post, which makes it more attractive and eye-catching. It did a great job in acknowledging uncertainty by sharing crucial information for students and handling misinformation. Nevertheless, there were also some best practices that they applied less often, such as referring to credible sources or demonstrating empathy. A real area of improvement however is to tell students more

often how to protect themselves. In addition, there may be more posts in which Ghent University thanks its stakeholders, although this is certainly not necessary in every post. Finally, it can be interesting to create a private hashtag during a health crisis. In this way, students have instant access to the most important measures of Ghent University.

4.2.3 In-depth interviews

This section discusses the results of five in-depth interviews with students from Ghent University. First, I will focus on health crisis communication by Ghent University and then elaborate on the communication via social media of this university. Lastly, I will review the general evaluation of the students interviewed. A summary of the in-depth interviews can be found in Appendix 8.6. To guarantee anonymity, only the first letter of the interviewees' names is used:

1) M – bachelor student – woman – criminology student 2) L – master student – man – law student

3) V – master student – woman - pedagogical science student 4) F – master student – woman – psychology student

5) N – master student – woman – law student

4.2.3.1 Health crisis communication by Ghent University

Expected information

In general, all students expected Ghent University to provide them with sufficient and clear information, especially at the beginning of Covid-19. As both M and V described it, they mainly wanted to know more about things relevant to them, such as exams and lessons. The majority also indicated that they expected to know how they could finish this academic year. Besides, L stated that the content of an update depends on the phase of the crisis. In the beginning, there is an alert phase in which he mainly expected information about prevention and awareness of the virus. L also indicated that he prefers Ghent University to say that they do not know anything yet instead of remaining silent about it.

With regard to expectations in terms of communication, N and L signalled it was essential to communicate quickly and to get no abundance of mails, which was sometimes the case. Too much information (update from the rector, from a professor, from a supervisor) can make people drop out. However, N mentioned she attaches more importance to a professor's mail than the rector's. Even though the majority said they did not read the rector's mails thoroughly, they still thought it was necessary as rector to give students courage. In addition, F noted that she felt it was very good that there was also an information moment with the dean since each faculty had its own specific rules.

Update speed

L, V and N stated they only wanted to receive a new update from Ghent University when a new decision was made to counteract the abundance of information. While F expected a weekly update at the beginning of the crisis, M expected at least a monthly update during the crisis. Although most students

indicated they received updates and all necessary information on time, M reported that she often heard updates first via a newspaper or the news2 instead of an official Ghent University channel.

Almost all students agreed it is more logical and professional when updates first appear on an official Ghent University channel (Ufora or webmail), rather than in the news or newspaper. L said it strengthens the bond of trust with students when they are the first to know something, or as M put it: "In the end, the

message is intended for students. Students should be the number one priority because without students, there is no university." N even expressed that she waits for an update to appear on Ufora before

considering it official since she finds Ufora more reliable than the news. However, M and L indicated that in the end, it is most important that students know the information, and not via which channel.

4.2.3.2 Health crisis communication via social media

Channel choice

The most common channels used to stay informed about the coronavirus were the news, the newspapers, online articles and the VRT NWS app. Apart from this, M, F and N followed the Facebook or Instagram page of Ghent University (or their faculty). In contrast, L and V did not follow any social media accounts of the university. When I asked the interviewees which channels are the most appropriate for communicating the corona updates of Ghent University, they all answered Ufora or webmail. V revealed that this is because she trusts these channels more than social media.

If they only had a choice out of social media channels, then 4 out of 5 found that Facebook was the best platform to communicate the updates to students. M believes Instagram is too informal, while Facebook comes across more professional. L noted that you can also put more text on Facebook than on Twitter. According to N, all detailed information about the measures should be available on Ufora and webmail, while there should be a shortened, more casual3 version on social media.

Furthermore, there exists some disagreement about the reliability of Ghent University’s social media posts. M stated social media is less formal than the news or newspapers, but not less reliable, so there is a difference in formality instead of reliability. L and N trusted a social media post of Ghent University more, while V trusted social media less than the news and newspapers. F was impartial.

However, they all agreed that there are many benefits for Ghent University by using social media. First, M mentioned it is a way to get closer to your students, to create more interaction and to provide some casual posts. According to L, social media makes it possible to keep in touch with students: “In the

future, social media will play a vital role in keeping track of what's happening, maybe even a bigger role than a newspaper or the news.” F pointed out that a university can reach students more easily via social

media, e.g. by organising a question session with the rector: “This is a much lower barrier to ask a

question than via email.” She also signalled that the chance to reach a student via social media is higher

2 When talking about “the news”, this paper refers to the daily news broadcast on television at VRT. 3 When using the word "casual", it refers to the Dutch version of the word "luchtig".

thanks to the different social media channels. Besides, N thinks a social media post is more attractive to read than a long mail, especially by using photos or videos.

Nevertheless, the interviewees mentioned also some drawbacks of social media. M finds it a disadvantage that Facebook works with algorithms, which causes not every post to appear on her timeline. Moreover, V noted that students spend even more time on their mobile phones when information is disseminated via social media. Finally, N mentioned that social media posts alone are not enough because students might miss out on important details.

Social media content

According to most students, it is okay to post some more casual things on social media, like encouraging tips for students or little videos. M indicated that this can be a relief in corona times, or like N said: “It

shows that Ghent University is more than just school.” However, L mentioned Ghent University should

watch out that the post are not too casual, since it may then appear as if the virus is no longer being taken seriously. In addition, all students expected the posts to mainly provide information on corona updates and measures. N added that Ghent University should also respond via social media to open letters written by students. Both L and V expressed that they do not expect to find personal information on social media. Besides, L noted that a post should be short, clear, and adapted to the medium used: “When there is too much text, students will not read it.”

The majority signalled Ghent University does not need to repeat on their social media channels how students should protect themselves against the virus, although repetition is not bad. F and V thought that they should focus on telling students how to protect themselves during an exam. Furthermore, everybody agreed that the posts should be available in both Dutch and English.

After showing some Twitter and Facebook posts, the students explained what they thought was good or less good about the messages. M liked the fact that they used photos or videos with every post. Additionally, all students noticed that Ghent University had an eye for the students’ well-being (e.g. tips to overcome the “block-down” routine), which they all appreciated. V and M thought it is good that most posts included a link, so students have the choice if they want more information or not. However, V liked the (showed) Facebook posts more than the Twitter posts: “Posts about research seem less relevant to

me and are more like a promotion for Ghent University. I believe posts should focus more on students.” L and N shared the same opinion.

4.2.3.3 General evaluation

It was striking that the students were very tolerant for Ghent University because “it is the first corona crisis for everyone”. For the most part, they were very pleased with the health crisis communication by

Ghent University. However, M, L and F noted it would have been better if Ghent University had communicated quicker with students. L added that they could have given more information about the virus itself in order to understand the measures better. This corresponds to N who expected additional information on the "why" of certain measures. Even though, the perception the students had of Ghent University did not change during the corona crisis. To conclude, four out of five students indicated that

Ghent University fulfilled their expectations concerning health crisis communication via social media during the Covid-19 crisis.

4.2.3.4 Conclusion

First, it is important to notice that the opinions of these five students should not be generalized. Nevertheless, the results do provide useful information for Ghent University.

The interviewees expected above all quick, clear and relevant information, but also no overload of information. Besides, most students found it logical that they first hear about an update via an official Ghent University channel, and only then via other media. It seems that Ghent University should pass on their updates first to the news, the newspapers and the VRT NWS app since these channels were most often used to check on updates regarding corona.

In addition, all students expect an update appears first on Ufora or webmail. Given that updates usually first appear on the website of Ghent University, and only then on Ufora and webmail, this should change. Furthermore, these students found Facebook the most appropriate social media channel to communicate updates. Since there was some disagreement about the reliability of social media channels, one might conclude that Ufora and webmail are the most important channels to share updates with students. However, social media, and especially Facebook, can play a supporting role in this. Besides, the interviewees summed up a lot of social media benefits, such as keeping in touch with students or displaying the updates in a more attractive way. One drawback is that not every social media posts appears on every student’s timeline. In order to solve this, Ghent University may sponsor its messages. Posts on Twitter and Facebook can definitely be casual according to the students. They also recommend keeping the posts short and clear, even the annexes.

Additionally, Ghent University should mainly tell how to protect yourself during an exam, and not only how to protect yourself in daily life. Displaying posts both in Dutch and English is important since social media can be an essential source of information for Erasmus students. Moreover, the interviewees believed it is important to focus on students in both Twitter and Facebook posts, and less on research. In general, the students found it especially good that Ghent University focused both on providing general information and paying attention to the well-being of the students. It could be useful however to give more details on the “why” of measures. Although the communication could have been quicker sometimes, the majority indicated Ghent University fulfilled their expectations via social media.

5 Conclusion and recommendations for Ghent University

The purpose of this paper was to find an answer to the three research questions. These answers will be discussed in this section, together with specific recommendations for Ghent University. The recommendations are formed based on the literature review, the analysis of the social media posts and the in-depth interviews.

1) Did Ghent University meet students’ expectations concerning health crisis communication via social media during the Covid-19 crisis?

Based on five in-depth interviews with students from Ghent University, it might be concluded that Ghent University fulfilled most of the students’ expectations. In general, they expected that Ghent University provided clear, quick and relevant information. Besides, it seemed like Facebook was the most appropriate social media channel to spread updates for the students. Twitter was not mentioned once as the most appropriate channel, although Twitter has the ability to serve as an effective information and communication platform (Jin et al., 2014). Twitter may be more popular with other age groups, which is something worth investigating.

However, social media mainly plays a supportive role to communicate updates, since the interviewees expected updates to first appear on Ufora or webmail. Nevertheless, they mentioned social media has many advantages and opportunities, such as reaching more students, showing updates in a more attractive way and creating additional interaction. Furthermore, students appreciated that Ghent University did not only focus on providing general information but also on the well-being of students. This is especially important knowing that the number of students with mental issues raised during the corona crisis (VRT NWS, 2020).

Although the results of these interviews cannot be generalised, they served as inspiration for the following recommendations:

1) Do not overload students with information. Too much information will cause students to get confused and not know what to read first. Therefore it is recommended only to share an update if a new decision is made.

2) Students expect to hear an update first via Ufora or webmail, and only then via other channels. By consequence, I suggest the following order to spread updates: Ufora/webmail – website of Ghent University – social media channels of Ghent University - media such as the news, newspapers and the VRT NWS app.

3) Investigate in a quantitative way if Facebook is indeed the most popular channel to share updates and if yes, make sure this is the first channel that will be used to share updates. To reach more students, it can be interesting to sponsor these posts.

4) Keep the posts short and clear, and keep on going using links providing more information. As stated by Schultz et al. (2011), short messages ensure more persuasive communication.