FAMILY PARTICIPATION IN THE

CARE OF OLDER HOSPITALISED

PATIENTS

A MULTICENTRIC QUANTITATIVE STUDY WITH PATIENTS,

FAMILY CAREGIVERS AND NURSES

Aantal woorden: 6102

Shani Lepoudre

Stamnummer: 01800585Laura Verstappen

Stamnummer: 01812839Promotor: dr. Liesbeth Van Humbeeck Copromotor: Dhr. Sander Aerens

Masterproef voorgelegd voor het behalen van de graad van master in de verpleegkunde en de vroedkunde

©Copyright UGent

Without written permission of the thesis supervisor and the authors it is forbidden to reproduce or adapt in any form or by any means any part of this publication. Requests for obtaining the right to reproduce or utilize parts of this publication should be addressed to the promotor.

A written permission of the thesis supervisor is also required to use the methods, products and results described in this work for publication or commercial use and for submitting this publication in scientific contests.

FAMILY PARTICIPATION IN THE

CARE OF OLDER HOSPITALISED

PATIENTS

A MULTICENTRIC QUANTITATIVE STUDY WITH PATIENTS,

FAMILY CAREGIVERS AND NURSES

Aantal woorden: 6102

Shani Lepoudre

Stamnummer: 01800585Laura Verstappen

Stamnummer: 01812839Promotor: dr. Liesbeth Van Humbeeck Copromotor: Dhr. Sander Aerens

Masterproef voorgelegd voor het behalen van de graad van master in de verpleegkunde en de vroedkunde

Deze pagina is niet beschikbaar omdat ze persoonsgegevens bevat.

Universiteitsbibliotheek Gent, 2021.

This page is not available because it contains personal information.

Ghent University, Library, 2021.

Deze pagina is niet beschikbaar omdat ze persoonsgegevens bevat.

Universiteitsbibliotheek Gent, 2021.

This page is not available because it contains personal information.

Ghent University, Library, 2021.

Content

Acknowledgements ... I Motivation duo thesis ... II Abstract (EN) ... III Abstract (NL) ... IV

INTRODUCTION ... 1

METHODS ... 4

Study design ... 4

Setting and participants ... 4

Questionnaire ... 5 Data collection ... 7 Data analysis ... 8 Ethical considerations ... 8 RESULTS ... 9 Descriptive statistics ... 9

Attitude towards open visiting hours and satisfaction with the provided care 11 Family collaboration and open visiting hours ... 11

Discrepancies between patients, family caregivers and nurses concerning performance of care tasks ... 12

Experiences of the family caregivers with FCC at the participating wards .... 14

DISCUSSION ... 17

Strengths and limitations ... 21

Recommendations for further research ... 21

Relevance for practice ... 22

CONCLUSION ... 23

ANNEXES ... 30

Annex 1: Questionnaire of the patients ... 30

Annex 2: Questionnaire of the family caregivers ... 38

Table list

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of patients and family caregivers 10 Table 2: The mean scores and standard deviations of the multi-item

questionnaires ... 11 Table 3: Family collaboration and open visiting hours regarding family

caregivers ... 12 Table 4: Discrepancies in performance of care tasks between three

Acknowledgements

This thesis marks the end of our Masters’ degree. Despite the immense work, we have learned a lot from this. This thesis would not exist without the help of a number of people. Therefore, we would like to thank these people.

First, we would like to thank our promoter and copromoter, dr. Van Humbeeck and mr. Aerens for their guidance, expertise and critical reflection. We are thankful for all the time they have invested in this study. An extra word of thanks goes to dr. Malfait for his expertise and help with the statistical analyses.

Furthermore, we would like to thank the participating wards for opening their doors to us. An appreciation also goes out to the participants because without them this study would not have been possible.

Next, a special thanks goes out to our families and partners for their support, encouragement and motivation. Even though it was not an easy period, thank you for always standing next to us during our education.

Finally, we would like to thank our friends and fellow students for reading and giving feedback on this work. We will not forget their encouraging words.

Motivation duo thesis

For this study, a duo thesis was carried out. Both students were equally responsible for all parts of this thesis.

First, the research domain of this study had a broad scope. Therefore, an exploratory design was used. The following components were examined within this study: (i) performance of certain care tasks, (ii) attitude towards an open visiting policy, (iii) general satisfaction with the provided care and (iv) experienced collaboration of family caregivers with geriatric nurses. In addition, three stakeholders were questioned, namely patients, family caregivers and nurses. Because of this broad view, multiple analyses could be carried out which could give a deeper insight into the research domain.

Second, questionnaires had to be developed. This included searching for useful questionnaires, the development of a matrix of questionnaires, forward and backward translation and making adjustments if necessary. Furthermore, three different versions of the questionnaire needed to be developed for the various stakeholders.

Third, questionnaires were handed out on nine wards that were spread over three hospitals. This resulted in a lot of data on which further analyses were carried out. This data had to be manually entered into SPSS 26. It would have been a lot of work for one researcher to process this data alone.

Finally, field work had to be carried out for the geriatric population. Every week, the researchers visited the nine hospital wards to help patients who were not able to complete the questionnaire by themselves. It would not have been possible for one researcher to visit all nine hospital wards within the inclusion period.

Abstract (EN)

Introduction: Current literature on family-centred care and open visiting policy

(OVP) mainly focuses on intensive and paediatric care units. Due to the specific nature of these departments, it remains unclear whether these findings can be translated to a geriatric hospital setting. Therefore, this study aimed to gain insight into (i) the care tasks that family caregivers may, can and are willing to perform, (ii) the attitude towards OVP and (iii) the experienced collaboration of family caregivers with nurses.

Method: A survey study with a cross-sectional design was conducted between

October 2019 and March 2020 in eight geriatric wards and one geriatric revalidation ward within three hospitals in East Flanders, Belgium. Three stakeholders were included, namely patients (n=330), their family caregivers (n=133) and nurses (n=67).

Results: Most patients would let their family caregiver perform many care tasks

without a nurse being present. The majority of family caregivers were more reluctant to perform intimate care tasks. Nurses had a more dynamic perspective towards care tasks that family caregivers can perform. Patients, family caregivers and nurses had a different attitude towards OVP (p<.001). The experienced collaboration between family caregivers and nurses was positively correlated with the satisfaction of family caregivers (r=0.710; p<.01).

Conclusion: This study gives insight into the care tasks that family caregivers

may, can and are willing to perform, the attitude towards OVP and the experienced collaboration of family caregivers with nurses. Further research, both quantitative and qualitative, is necessary within this research domain.

Keywords: family-centred care, open visiting hours, hospital, geriatric patients,

Abstract (NL)

Inleiding: De huidige literatuur omtrent familiegerichte zorg en open

bezoekbeleid (OVP) richt zich voornamelijk op intensieve en pediatrische zorgafdelingen. Door het specifieke karakter van deze afdelingen blijft het onduidelijk of de onderzoeksresultaten vertaald kunnen worden naar geriatrische ziekenhuisafdelingen. Het doel van dit onderzoek is om inzicht te verkrijgen in (i) de zorgtaken die mantelzorgers mogen, kunnen en willen uitvoeren, (ii) de attitude ten opzichte van OVP en (iii) de ervaren samenwerking van mantelzorgers met verpleegkundigen.

Methode: Een surveyonderzoek met een cross-sectioneel design werd

uitgevoerd tussen oktober 2019 en maart 2020 op acht geriatrische afdelingen en één geriatrische revalidatieafdeling binnen drie ziekenhuizen in Oost-Vlaanderen, België. De deelnemers waren patiënten (n=330), hun mantelzorgers (n=133) en verpleegkundigen (n=67).

Resultaten: De meeste patiënten zouden hun mantelzorgers de meerderheid

van de zorgtaken laten uitvoeren zonder dat er een verpleegkundige aanwezig is. Het merendeel van de mantelzorgers waren terughoudender om intieme zorgtaken uit te voeren. Verpleegkundigen hadden een meer dynamisch perspectief omtrent de zorgtaken die mantelzorgers mogen uitvoeren. Patiënten, mantelzorgers en verpleegkundigen hadden een andere houding ten opzichte van OVP (p<.001). De ervaren samenwerking tussen mantelzorgers en verpleegkundigen was positief gecorreleerd met de tevredenheid van de mantelzorgers (r=0,710; p<.01).

Conclusie: Dit onderzoek geeft inzicht in de zorgtaken die mantelzorgers

mogen, kunnen en willen uitvoeren, de attitude ten opzichte van een OVP en de ervaren samenwerking van mantelzorgers met verpleegkundigen. Verder onderzoek, zowel kwantitatief als kwalitatief, is noodzakelijk binnen dit onderzoeksdomein.

Zoektermen: familiegerichte zorg, open bezoekuren, ziekenhuis, geriatrische

‘DE MASTERPROEF IS IN ARTIKELVORM GESCHREVEN. DE UITGEBREIDE RAPPORTAGE VAN DE SYSTEMATISCHE LITERATUURSTUDIE MAAKT

GEEN DEEL UIT VAN HET GESCHREVEN ARTIKEL. DE

LITERATUURSTUDIE WERD EERDER BEOORDEELD IN HET

GELIJKGENOEMDE OPLEIDINGSONDERDEEL.’

INTRODUCTION

Hospitalisation can be a stressful event for both the patient and his or her loved ones (Lindhardt, Nyberg, & Hallberg, 2008). Both are ripped out of their daily routine and are forced to adapt to new circumstances and routines of the hospital (Bridges, Collins, Flatley, Hope, & Young, 2020). It is important to acknowledge that a family caregiver can play a key role in the patient's life (Bookman & Harrington, 2007; Engström, Uusitalo, & Engström, 2011; Kokorelias, Gignac, Naglie, & Cameron, 2019). They can form a familiar face within a strange environment and play an integral role in the older person’s care (Kokorelias et al., 2019). Therefore, nurses must take the patient's family caregivers into account and try to involve them as much as possible into the patient’s care (McConnell & Moroney, 2015).

Family caregivers can be defined as a family member, a close friend or a neighbour who provides unpaid assistance with daily activities such as care coordination, financial affairs and/or hands-on care (Brodaty & Donkin, 2009; Collins & Swartz, 2011; Kokorelias et al., 2019). Family caregivers may be motivated to care because of several reasons (e.g. a sense of love or reciprocity, spiritual fulfilment, a sense of duty, guilt, social pressure and greed) (Brodaty & Donkin, 2009). Often family caregivers perform more complex care duties when the patients’ healthcare needs increase over time (Collins & Swartz, 2011; Kokorelias et al., 2019).

When looking at the involvement of family caregivers in the care for patients the following term comes along: family-centred care (FCC) (Coyne, O'Neill, Murphy, Costello, & O'Shea, 2011; Kokorelias et al., 2019). The Institute for Patient- and Family Centered Care defines FCC as “mutually beneficial partnerships between

health care providers, patients, and families in health care planning, delivery, and evaluation.” (Kokorelias et al., 2019, p. 2). With the current ageing population and growing number of older people, FCC can improve the quality of life of patients and their family caregivers. FCC has been proposed to address the needs of the patient, but also the needs of their family caregivers (Kokorelias et al., 2019). It is a term that is mostly used in paediatrics, neonatal intensive care units (NICU) and intensive care units (ICU), but is starting to emerge in the adult inpatient population (Ciufo, Hader, & Holly, 2011; Hardin, 2012; Kokorelias et al., 2019). Within the geriatric population, the following advantages of FCC occur: enhancement of the quality of care, reduction of possible complications, easing the experience of hospitalisation, shortening the admission duration and reduction of readmission rate (Laitinen-Junkkari, Merilainen, & Sinkkonen, 2001; Moyle, Bramble, Bauer, Smyth, & Beattie, 2016; Nayeri, Gholizadeh, Mohammadi, & Yazdi, 2015).Family caregivers and patients feel less anxious, their wellbeing has improved and they feel more satisfied. Also the family caregivers feel more prepared for caregiving in the hospital and at home (Boltz, Resnick, Chippendale, & Galvin, 2014; Kelley, Godfrey, & Young, 2019; Nayeri et al., 2015). When family caregivers carry out certain care tasks, the nurses have more time to concentrate on more vital care activities (Nayeri et al., 2015). The care tasks that family caregivers perform for their relative during a hospitalisation are mostly standard activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) along with tasks related to providing emotional support (Auslander, 2011; Laitinen-Junkkari et al., 2001; Pena & Diogo, 2009; Riffin, Van Ness, Wolff, & Fried, 2017).

Next, when a hospital ward wants to apply FCC, it may be important to implement an open visiting policy (OVP) (Ciufo et al., 2011). The literature indicates that the principles of FCC are in fact linked to an OVP (Ciufo et al., 2011; Coyne et al., 2011; Ellis, 2018; Hurst, Griffiths, Hunt, & Martinez, 2019; Kokorelias et al., 2019). According to Berti, Ferdinande, and Moons (2007, p. 1060), an OVP implies the following: “a policy that imposes no restrictions on the time of visits, length of visits, and/or number of visitors.” This policy can promote the family caregivers’

involvement in care which is recognised as important for patients’ recovery (Hurst et al., 2019; Shulkin et al., 2014). OVP has a number of advantages, namely better communication, better possibility of family participation, higher patient and family caregiver satisfaction, lower anxiety of patient and family caregivers, improvement of patient’s emotional wellbeing and nurses have better access to useful information (Bélanger, Bussières, Rainville, Coulombe, & Desmartis, 2017; Berti, Ferdinande, & Moons, 2007; Hurst et al., 2019; Monroe & Wofford, 2017). Current FCC and OVP literature mainly focuses on paediatrics, NICU and ICU. Due to the specific nature of these departments, it remains unclear whether the research findings can be translated to the geriatric hospital setting. In addition, knowing what family caregivers are actually willing to do for their hospitalised older relatives could be beneficial in helping nurses with care provision, allowing them to guide family caregivers’ participation, providing opportunities for education and supporting the goal of maintaining lifestyles and routines for older adults and their family caregivers. Also, a scarcity of literature exists on the nurses’ attitude towards OVP in a geriatric hospital setting. Therefore, this study aimed to gain insight into (i) the care tasks that family caregivers may, can and are willing to perform, (ii) the attitude towards open visiting hours in a geriatric hospital setting and (iii) the experienced collaboration of family caregivers with geriatrics nurses.

METHODS

Study design

A survey study with a cross-sectional design was conducted to obtain information about the possible care tasks that family caregivers could perform, the attitude towards open visiting hours and the experienced collaboration of family caregivers with nurses.

Setting and participants

The data were collected in eight geriatric wards and one geriatric revalidation ward within three hospitals in the province of East Flanders, Belgium. This study contained three hospitals, namely one university hospital (hospital A), one mayor city hospital (hospital B) and one rural hospital (hospital C). In hospital A the data was collected within one ward. In hospital B the data was collected on six wards and in hospital C on two wards. All wards had a closed visiting policy. A consecutive sample was obtained from geriatric patients admitted to one of the participating wards and their family caregivers. In addition, a convenience sample of all nurses working in one of the nine geriatrics wards was obtained.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were drawn up for each stakeholder (geriatric patients, family caregivers and nurses). First, only geriatric patients (Geriatric Risk Profile [GRP] > 2) aged 75 or older were included. A geriatric patient is distinguished from the vital older patient by the following characteristics: polypharmacy, polypathology, geriatric syndromes, psychosocial problems, etc. (Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre, 2015). In addition, the patient had to have sufficient knowledge of the Dutch language and had to be admitted to one of the participating wards for at least three days. Patients with dementia, patients who were too sick, patients who were extremely confused or who were sight-impaired in combination with a speech problem were excluded.

Second, one family caregiver per geriatric patient was included. The patient, if possible, labelled his or her primary family caregiver. Family caregivers who did not speak the Dutch language were excluded.

Finally, nurses (with Master's, Bachelor's or Associate’s degree) working on a geriatric ward were included. Nurses working on the mobile team were excluded. The nurses needed to be working on the participating ward for at least six months. Nurses who did not carry out care tasks were excluded (e.g. head nurses). The same applied to nurses on maternity leave, long-term absence and students.

Questionnaire

Beliefs and Attitudes toward Visitation in ICU Questionnaire (BAVIQ)

The BAVIQ was used in the questionnaire for all stakeholders. The BAVIQ comprises two dimensions, ‘the beliefs towards visitation’ and ‘the attitudes towards visitation’. In the questionnaire of this study, only the attitude section (14 items) was used. A 5-point Likert scale was used with the answer categories 'strongly disagree' to 'strongly agree'. There were two closed questions to which the stakeholders had to answer with a number. This questionnaire was not tested on its validity or reliability (Berti et al., 2007). Permission to use the licensed BAVIQ was granted by Prof. dr. Moons (Academic Centre for Nursing and Midwifery, University of Leuven). Permission to only use the attitude section and to adjust it for the geriatric setting was also granted. A reliability analysis was performed by the researchers. The analysis showed that the BAVIQ had a good overall internal consistency (α=0.80). The two closed questions were not included in this analysis.

Family Collaboration Scale (FCS)

The FCS was included in the questionnaire for solely the family caregivers in order to measure how family caregivers experience their collaboration with nurses. The instrument is valid and reliable in Dutch context. It is composed of 20 items and is subdivided into three dimensions, namely ‘trust in nursing care’ (5 items), ‘accessible nurse’ (6 items) and ‘influence on decisions’ (9 items). The answer possibilities were expressed in a 5-point Likert scale. Response alternatives were ‘never’ to ‘always’ or ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. The higher the score, the higher the experience of collaboration with nurses (Hagedoorn et al., 2019). A reliability analysis showed that the total FCS had a

good overall internal consistency (ɑ=0.91). The three dimensions had an internal consistency of 0.62-0.87.

Care tasks questionnaire based on the Royal resolution 78 (18th June 1990) The Royal resolution 78 contains a list of the technical nursing tasks reserved for the nursing profession (Nationaal Verbond van Katholieke Vlaamse Verpleegkundigen en Vroedvrouwen [NVKVV], 2015). With the help of seven registered nurses, 25 items were developed based on the list of nursing care tasks of the Royal resolution 78. These items were used in the questionnaires of all stakeholders. The aim of this part of the questionnaire was to examine how willing family caregivers were to perform a particular care task and if patients and nurses thought it was acceptable that a certain care task was performed by a family caregiver (perform alone, perform together with a nurse, do not perform). Before completing the questionnaire the participants were informed about the importance of an informal care certificate. This certificate allows the family caregiver to legally carry out a certain care task for a certain period. This implies that the family caregiver is trained by a nurse to perform a certain care task, but also receives additional information about the disease or disorder, the possible complications or problems and points of attention. The patient must always give permission for the family caregiver to perform a certain care task (Belgisch Staatsblad, 2014; NVKVV, 2015). In addition, a reliability analysis was performed by the researchers. The analysis showed that the care tasks questionnaire had an excellent internal consistency (ɑ=0.98).

Satisfaction with provided care

Patients and family caregivers were asked about their general satisfaction of the ward and the healthcare providers. This self-developed questionnaire consisted of three items and were all scored on a 5-point Likert scale (‘very dissatisfied’ to ‘very satisfied’). The higher the score, the more satisfied the patient or the family caregiver was with the provided care. A reliability analysis showed that the satisfaction questionnaire had a good overall internal consistency (ɑ=0.81).

Single items

For the questionnaire of the family caregivers seven single items were developed. These seven single items focused on the practical experience of the family caregivers with FCC. Most of the questions were ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions.

Data collection

Data collection took place from October 2019 to March 2020 and was carried out by three researchers. Each researcher was responsible for three wards. Each ward was visited weekly by the responsible researcher to help patients fill in the questionnaire. At the ward, all patients who met the inclusion criteria were identified and asked to participate in the study by the researchers. In addition, an instrument was used for the patients to visualise the answer options. Family caregivers were also approached by the researchers to fill in the questionnaire when present. If the family caregiver was not present, the questionnaire was left behind for them to fill in. All questionnaires and informed consents of patients and family caregivers were on paper. The questionnaire of the patients and the family caregivers can be found in Annexes 1 and 2.

Eligible nurses who met the inclusion criteria were identified and asked to participate in the study by the researchers and the head nurses. The care managers were also involved with recruiting eligible nurses. For hospital A and C, the questionnaires and the informed consents of the nurses were given on paper. The nurses were reminded to fill in the questionnaire when the researchers visited the ward. Hospital B requested a digital questionnaire for which the online web application LimeSurvey version 2.05 was used. When the nurses had signed an informed consent, they received an online link for the questionnaire by email. In order to facilitate recruitment more, the researchers decided to use an online informed consent for hospital B. Reminder emails were sent to the nurses. The questionnaire of the nurses can be found in Annex 3.

Data analysis

All statistical analysis were performed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 26 (SPSS 26). Data with a p-value of 0.05 or less were considered significant (Twisk, 2016). Demographic characteristics were described with descriptive statistics. Descriptive statistics were also used to calculate the distribution of the variables. For all multi-item questionnaires, the mean scores and standard deviations were calculated.

Quantitative correlations were calculated using Pearson correlation. Pearson Chi-Square analyses were used to test for differences between the independent groups regarding the performance of care tasks. A Bonferroni correction was used to adjust p-value (p<.017). The difference in attitude towards open visiting hours between the independent groups, the predictors of attitude towards open visiting hours and the difference in satisfaction of the provided care between the patients and family caregivers were analysed using a generalized linear mixed model. Difficulties with multilevel data clustering were addressed using this statistical analysis (Heck, Thomas & Tabata, 2012; Jaeger, 2008). Within this study, three levels of possible clustering were identified: (i) the stakeholders, (ii) the wards and (iii) the hospitals.

Ethical considerations

The Ethical Committee of Ghent University Hospital approved the study protocol (B670201940434 and B670201940435). All patients, family caregivers and nurses were informed about the aims of the study and were asked to read the informed consent. Before entering the study the informed consent was signed. If the informed consent form was not signed, but the questionnaire was completed in full, the researchers assumed implied consent. The respondents were also assured that they could withdraw from completing the questionnaire at any time and that this would not have an influence on the care. The researchers ensured the anonymity of the participants throughout the study. Only the researchers had access to the data.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

A total of 579 eligible patients were asked to participate, from which 330 patients filled in the questionnaire (response rate: 60.0%). The majority of patients were between 80-89 years old (62.3%) and 68.7% were female. Almost half of the patients lived independently (49.7%). Of 446 family caregivers, 133 completed the questionnaire (response rate: 29.8%) of which 70.8% were female and age ranging between 30 years and 95 years old (Mage=67 years; SD=13.46). When looked at the relationship of the family caregiver towards the patient, 52.7% were children, 31.0% were the patient’s partner, 3.1% were siblings and 13.2% were other persons such as a grandchild, niece/nephew or friend. Family caregivers were asked if they saw themselves as their family member's primary caregiver, 30.8% answered ‘no’. Patients’ and family caregivers’ socio-demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Of 149 eligible nurses, 67 responded to the questionnaire (response rate of 45.0%). Most nurses were female (83.6%). When it comes to education, 46.3% had an Associate’s degree, 49.3% a Bachelor’s degree and 4.5% a Master’s degree. Over three-quarters of nurses (85.1%) worked more than sixty percent on the ward. Most of participating nurses (53.7%) had less than five years of working experience on a hospital ward, 19.4% had between five and fifteen years of experience and about a quarter of the nurses (26.9%) had more than fifteen years of experience. When asked if they considered themselves as a family caregiver, 80.6% answered 'no'.

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of patients and family caregivers Characteristics patients n (%) Characteristics family caregivers n (%) Gender Woman Men 226 (68.7) 103 (31.3) 92 (70.8) 38 (29.2) Age 30-49 50-59 60-69 70-79 80-89 90-99 - - - 43 (13.1) 205 (62.3) 81 (24.6) 7 (5.4) 38 (29.5) 32 (24.8) 21 (16.3) 26 (20.2) 5 (3.9) Living situation Living alone Living with partner Living with child(ren)

Living with other members of the family Residential care centre

Other 163 (49.7) 92 (28.0) 22 (6.7) 8 (2.4) 37 (11.3) 6 (1.8) 17 (13.4) 88 (69.3) 10 (7.9) 7 (5.5) 4 (3.1) 1 (0.8) Living with family caregiver/patient

No Yes 218 (66.7) 109 (33.3) 82 (62.5) 49 (37.4) Education None Primary education Secondary education Higher Education University education 8 (2.4) 160 (48.8) 121 (36.9) 32 (9.8) 7 (2.1) 4 (3.1) 24 (18.3) 50 (38.2) 44 (33.6) 9 (6.9) Children No Yes 71 (21.6) 258 (78.4) 26 (19.8) 105 (80.2)

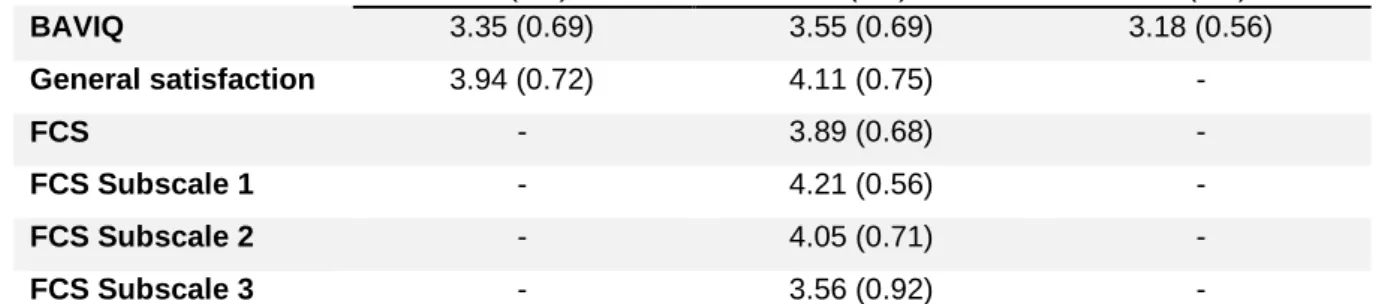

Family caregivers (M=3.55; SD=0.69) had a higher mean score than patients (M=3.35; SD=0.69) and nurses (M=3.18; SD=0.56) for the questionnaire ‘attitudes towards open visiting hours’ (BAVIQ). In terms of general satisfaction, family caregivers (M=4.11; SD=0.75) had a higher mean score when compared to patients (M=3.94; SD=0.72). Next, a mean score of 3.89 (SD=0.68) was found for the experienced collaboration between family caregivers and nurses (FCS). A lower mean score was found for subscale ‘influence on decisions’ (M=3.56; SD=0.92) compared to subscale ‘trust in nursing care’ (M=4.21; SD=0.56) and subscale ‘accessible nurse’ (M=4.05; SD=0.71). An overview of the mean scores and standard deviations of the multi-item questionnaires can be found in Table 2.

Table 2: The mean scores and standard deviations of the multi-item questionnaires Patients M (SD) Family caregivers M (SD) Nurses M (SD) BAVIQ 3.35 (0.69) 3.55 (0.69) 3.18 (0.56) General satisfaction 3.94 (0.72) 4.11 (0.75) - FCS - 3.89 (0.68) - FCS Subscale 1 - 4.21 (0.56) - FCS Subscale 2 - 4.05 (0.71) - FCS Subscale 3 - 3.56 (0.92) -

Attitude towards open visiting hours and satisfaction with the provided care

Patients were less satisfied with the provided care than family caregivers (p=.032; β=-0.162; 95% CI -0.310 to -0.014). Nurses, family caregivers and patients had a different attitude towards OVP (p<.001). Family caregivers had a better attitude towards OVP than nurses and patients (p<.001; β=0.333; 95% CI 0.141 to 0.525). Patients had no other attitude towards OVP compared to nurses (p=.095; β=0.147; 95% CI -0.026 to 0.321). Also, 25.4% of the patients, 43.9% of the family caregivers and 30.5% of the nurses thought their ward had an OVP.

There was no difference in attitude compared to open visiting hours based on gender (p=.508) and training (p=.317) for all stakeholders. Family caregivers and nurses who identified themselves as informal caregivers had no other attitude towards visiting hours (p=.551). Age (p=.494), having children (p=.386), living with family caregiver or patient (p=.319) or living situation (p=.460) did not have an influence on the attitude towards open visiting hours for the family caregiver or the patient.

Family collaboration and open visiting hours

The degree of experienced collaboration between family caregivers and nurses (r=0.710; p<.01) and its three dimensions, namely 'trust in nursing care' (r=0.496; p<.01), 'accessible nurse' (r=0.729; p<.01) and 'influence on decisions’ (r=0.646; p<.01), were moderate to strongly correlated with the degree of satisfaction of the family caregivers. No association was found between open visiting hours and the

degree of experienced collaboration between family caregivers and nurses (p=.519). Also, no association was found between open visiting hours and the degree of satisfaction for patients and for family caregivers (p=.588; p=.808). The Pearson correlations coefficients of the family caregivers are presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Family collaboration and open visiting hours regarding family caregivers

1 2 3 4 5 6

1 General satisfaction 1

2 BAVIQ -0.021 1

3 Trust in nursing care 0.496** 0.028 1

4 Accessible nurse 0.729** -0.031 0.647** 1

5 Influence on decisions 0.646** -0.085 0.666** 0.716** 1

6 FCS 0.710** -0.062 0.804** 0.878** 0.944** 1

*p < .05; **p <.01

Discrepancies between patients, family caregivers and nurses concerning performance of care tasks

For the care task questionnaire a Chi-square analysis (3x3) was carried out for the three stakeholders. Each care task was significant (p<.001). An overview of the Chi-square analyses can be found in Table 4. Next, a total of three post-hoc analyses were performed per care task. These sub-analyses (2x3) were carried out in order to see a clear difference between the following subgroups: patients – family caregivers, patients – nurses and family caregivers – nurses. For the sub-analyses of patients and family caregivers the following care tasks were not significant: (i) giving food without swallowing problems (p=.051), (ii) brushing teeth or dentures (p=.019), (iii) giving oral medication (p=.019) and (iv) placement of safety tray (p=.030). For the sub-analyses of family caregivers and nurses following care tasks were not significant: (i) emptying the urine bag (p=.036), (ii) giving rectal medication (p=.021), (iii) giving a subcutaneous injection (p=.057) and (iv) applying tension stockings (p=.036).

When looked at the sub-analysis of feeding with swallowing problems between the nurses and the patients (χ²=153.256; df=2; p<.001), 62.1% of nurses indicated that helping the patient with eating can be done together while only 4.1% of the patients gave the same answer. Sixty-five percent of patients felt that

the family caregiver could help with feeding without a nurse present. The same trend was visible between the family caregivers and the nurses (χ²=32.001; df=2; p<.001), 45.2% of the family caregivers wanted to perform it alone, 20.9% with a nurse and 33.9% didn’t want to perform it. For the sub-analysis feeding without

swallowing problems, none of the nurses indicated that the family caregivers

could not perform this care task alone.

For the subsection washing body there is a significant difference between patients – family caregivers (χ²=23.164; df=2; p<.001), patients – nurses (χ²=79.942; df=2; p<.001) and family caregivers – nurses (χ²=29.678; df=2; p<.001). Of the 67 nurses, 54.5% stated that the family caregiver could perform the care task alone, 37.9% stated that it should be performed together and 7.6% stated that the family caregiver could not perform this task. However, only 3.8% of patients indicated that the family caregiver is allowed to perform the care task with the nurse and 36.9% indicated that their family caregivers are not allowed to perform this care task. When comparing the results of the family caregiver against the results of the patient, the same dynamics could be detected.

Next, the subsection helping the patient to toilet and clean up afterwards also had a significant difference between patients – family caregivers (χ²=15.557; df=2; p<.001), patients – nurses (χ²=39.821; df=2; p<.001) and family caregivers – nurses (χ²=19.497; df=2; p<.001). A clear difference between not wanting or not being allowed to perform the care task is found between two subgroups, namely patients – nurses and family caregivers – nurses. Of the patients and the family caregivers, 37.8% answered ‘do not perform’, while only 7.7% of the nurses answered the same answer option.

When looking at the subsection subcutaneous injection there was solely a significant difference between patients – family caregivers (χ²= 11.303; df=2; p=0.004) and patients – nurses (χ²=26.501; df=2; p<.001). Almost half (46.5%) of the patients indicated that the family caregiver can perform this care task alone, while 17.9% of the nurses agreed. Of the 67 nurses, 23.9% found that the family caregiver could perform this task while supervised by the nurse. It was noticeable that 33.8% of family caregivers wanted to perform this task alone and 16.9%

wanted to do it together with a nurse. Approximately half of the family caregivers (49.2%) did not want to perform this task.

Experiences of the family caregivers with FCC at the participating wards

Almost forty percent of family caregivers (39.4%) did not know who they could contact within the treating team. When asked if there had been contact with the treating team, 43.3% of the family caregivers replied that they contacted the treating team first, 33.1% replied that the treating team had contacted them first and 23.6% replied that no contact had taken place. The family caregivers were mainly in contact with the team to get acquainted (18.7%), get information (35.7%) and prepare for discharge (20.9%). Most family caregivers (91.1%) had not received any information on the existence of peer contact and initiatives to support them. Finally, more than half of the family caregivers (52.4%) had no need for emotional support from the team. Almost half (49.6%) indicated that there was no need for practical support.

Table 4: Discrepancies in performance of care tasks between three stakeholders

Patients Family caregiver Nurses Chi- square

Perform alone n (%) Perform together with nurse n (%) Do not perform n (%) Perform alone n (%) Perform together with nurse n (%) Do not perform n (%) Perform alone n (%) Perform together with nurse n (%) Do not perform n (%) Nutrition Feeding without swallowing problems Feeding with swallowing problems 223 (70.8) 204 (65.0) 7 (2.2) 13 (4.1) 85 (27.0) 97 (30.9) 89 (72.4) 52 (45.2) 8 (6.5) 24 (20.9) 26 (21.1) 39 (33.9) 63 (95.5) 11 (16.7) 3 (4.5) 41 (62.1) 0 (0.0) 14 (21.2) X2 = 37.312* a X2 = 146.868* Mobility

Help from bed to seat Changing position in bed Using a hoist 235 (74.6) 215 (68.5) 167 (53.2) 8 (2.5) 18 (5.7) 41 (13.1) 72 (22.9) 81 (25.8) 106 (33.8) 80 (65.6) 53 (43.1) 38 (31.1) 12 (9.8) 27 (22.0) 32 (26.2) 30 (24.6) 43 (35.0) 52 (42.6) 50 (76.9) 31 (47.0) 10 (15.2) 13 (20.0) 31 (47.0) 38 (57.6) 2 (3.1) 4 (6.1) 18 (27.3) X2 = 40.109* X2 = 92.127* X2 = 76.956* Hygiene

Brushing teeth or dentures Washing hair Washing body 220 (71.9) 209 (68.5) 186 (59.2) 5 (1.6) 5 (1.6) 12 (3.8) 81 (26.5) 91 (29.8) 116 (36.9) 70 (59.8) 71 (58.7) 51 (40.8) 6 (5.1) 13 (10.7) 19 (15.2) 41 (35.0) 37 (30.6) 55 (44.0) 65 (98.5) 64 (97.0) 36 (54.5) 1 (1.5) 1 (1.5) 25 (37.9) 0 (0.0) 1 (1.5) 5 (7.6) X2 = 45.481* a X2 = 51.078* a X2 = 82.685* Excretion

Helping patient to toilet Helping patient to toilet and cleaning afterwards. Renew incontinence material

Emptying the urine bag Enema/clyster 203 (64.4) 185 (58.7) 178 (56.9) 169 (54.0) 144 (46.0) 7 (2.2) 11 (3.5) 10 (3.2) 12 (3.8) 13 (4.2) 105 (33.3) 119 (37.8) 125 (39.9) 132 (42.2) 156 (49.8) 80 (64.0) 62 (48.8) 55 (44.4) 52 (43.0) 21 (17.2) 14 (11.2) 17 (13.4) 18 (14.5) 19 (15.7) 17 (13.9) 31 (24.8) 48 (37.8) 51 (41.1) 50 (41.3) 84 (68.9) 56 (86.2) 47 (72.3) 37 (56.1) 24 (36.4) 6 (9.1) 7 (10.8) 13 (20.0) 24 (36.4) 21 (31.8) 22 (33.3) 2 (3.1) 5 (7.7) 5 (7.6) 21 (31.8) 38 (57.6) X2 = 39.145* X2 = 43.335* X2 = 80.529* X2 = 51.459* X2 = 87.744* Medical care

Simple wound care 206 (65.6) 16 (5.1) 92 (29.3) 68 (53.1) 22 (17.2) 38 (29.7) 14 (20.9) 24 (35.8) 29 (43.3) X2 = 69.772*

Table 4: Discrepancies in performance of care tasks between three stakeholders (continued)

Patients Family caregiver Nurses Chi- square

Perform alone n (%) Perform together with nurse n (%) Do not perform n (%) Perform alone n (%) Perform together with nurse n (%) Do not perform n (%) Perform alone n (%) Perform together with nurse n (%) Do not perform n (%) Medication examination Oral Medication patches Airway

Nose, eye and ear drip Rectal Subcutaneous injection 236 (74.9) 226 (71.7) 217 (69.3) 232 (74.1) 156 (50.0) 146 (46.5) 7 (2.2) 11 (3.5) 12 (3.8) 6 (1.9) 12 (3.8) 24 (7.6) 72 (22.9) 78 (24.8) 84 (26.8) 75 (24.0) 144 (46.2) 144 (45.9) 99 (79.2) 84 (68.9) 76 (60.8) 87 (70.2) 43 (33.6) 44 (33.8) 8 (6.4) 13 (10.7) 15 (12.0) 10 (8.1) 18 (14.1) 22 (16.9) 18 (14.4) 25 (20.5) 34 (27.2) 27 (21.8) 67 (52.3) 64 (49.2) 39 (58.2) 25 (37.3) 26 (38.8) 32 (47.8) 22 (32.8) 12 (17.9) 20 (29.9) 22 (32.8) 30 (44.8) 24 (35.8) 20 (29.9) 16 (23.9) 8 (11.9) 20 (29.9) 11 (16.4) 11 (16.4) 25 (37.3) 39 (58.2) X2 = 69.399* X2 = 64.123* X2 = 92.844* X2 = 86.877* X2 = 50.699* X2 =29.907* Freedom restrictions

Use of bed fences 241 (77.0) 7 (2.2) 65 (20.8) 81 (66.9) 15 (12.4) 25 (20.7) 45 (67.2) 21 (31.3) 1 (1.5) X2 = 70.609*

Fixation Safety tray Seat belt 236 (75.4) 219 (70.0) 9 (2.9) 10 (3.2) 68 (21.7) 84 (26.8) 90 (75.0) 79 (66.9) 10 (8.3) 12 (10.2) 20 (16.7) 27 (22.9) 36 (53.7) 23 (34.3) 29 (43.3) 38 (56.7) 2 (3.0) 6 (9.0) X2 = 108.778* X2 = 150.224* Others

Applying tension stockings Taking blood pressure, temperature & pulse

214 (68.2) 221 (70.4) 8 (2.5) 10 (3.2) 92 (29.3) 83 (26.4) 60 (47.6) 70 (56.0) 21 (16.7) 16 (12.8) 45 (35.7) 39 (31.2) 25 (37.3) 12 (17.9) 22 (32.8) 17 (25.4) 20 (29.9) 38 (56.7) X2 = 71.431* X2 = 77.435*

DISCUSSION

This study extended the understanding of the scope and variety of care tasks that family caregivers can and are willing to perform during their older relatives’ hospitalisation. Most patients would let their family caregiver perform a large part of the listed care tasks without a nurse being present. The majority of family caregivers would want to participate in many caregiving activities with a nurse or without a nurse, but they were more reluctant to perform intimate care tasks. Nurses had a more dynamic perspective towards the listed care tasks. Next, this study also extended the insight into the attitude towards an OVP. It appeared that the three stakeholders had a different attitude towards this policy. Furthermore, a better insight is gained into the experienced collaboration between family caregiver and nurses. Family caregivers experienced an overall good collaboration with the nurses.

First, it is noticeable that nurses would prefer to perform more complex or intimate nursing tasks by themselves or together with the family caregiver. In other words, the nurses would allow family caregivers to perform rather simple care tasks. This phenomenon is also seen in the ICU, where nurses have a positive perception of family involvement when it comes to simple care tasks (Garrouste-Orgeas et al., 2010; Hetland, Hickman, McAndrew, & Daly, 2017; Hetland, McAndrew, Perazzo, & Hickman, 2018; Kydonaki, Kean, & Tocher, 2020). Within this setting various explanations were given. These explanations are interwoven with each other and may also apply to geriatric nurses. To start, nurses feel responsible for the care of the patient whereby guarantying safety is one of their main priorities (Hagedoorn et al., 2017; Kydonaki et al., 2020). They may feel that the safety of the patient is not assured (Hetland et al., 2018) when family caregivers are performing a certain care task alone. Nurses are afraid that family caregivers will make mistakes more quickly, will make wrong interpretations and that additional injuries will occur (Hetland et al., 2017; Hetland et al., 2018; Heydari, Sharifi, & Moghaddam, 2020; Liput, Kane-Gill, Seybert, & Smithburger, 2016). They do not only fear the consequences for the patient, but they also fear the possibility of family caregivers hurting themselves while performing a certain task (McConnell

& Moroney, 2015). Building a trusting relationship with the family caregiver is needed in order to let them perform a certain care task (Kydonaki et al., 2020; Mackie, Mitchell, & Marshall, 2019). Because of this, nurses may be able to let go of some of their controlling tendencies. Nurses may also feel that the patient's privacy can be violated when family caregivers perform certain intimate care tasks such as bed baths (Hetland et al., 2018; Heydari et al., 2020; McConnell & Moroney, 2015). They thought this was going to lower the patient's dignity (McConnell & Moroney, 2015). Within this study, this trend is less explicit. However, they were more reluctant to let family caregivers perform extremely intimate care tasks such as administering rectal medication. Patients would let the family caregivers carry out more care tasks than what their family caregivers actually want to provide. Nurses may be more concerned about the complex or intimate nursing tasks than necessary.

In Belgium, family caregivers need a certificate to legally perform technical nursing tasks for a certain period. This implies that the family caregiver is trained by a nurse to perform a certain care task (NVKVV, 2015). Therefore, it is evident that proper preparation and education of family caregivers is important in both physical and non-physical care because a lack of knowledge and skills can be a barrier to participate in care (Heydari et al., 2020). Consequently, the nurse should provide education about the particular care task (Heydari et al., 2020; Kokorelias et al., 2019). It is desirable that nurses learn how to deal with family caregivers, how to guide them and how to have better communication with them (Hardin, 2012).

In addition, the questionnaire of the care tasks consisted mainly of technical nursing care activities. These care tasks were particularly related to the physical care of the patient. In other studies the emphasis was rather on standard ADL and IADL tasks and on tasks related to providing emotional support (Auslander, 2011; Laitinen-Junkkari et al., 2001; Pena & Diogo, 2009; Riffin et al., 2017). Providing care can be interpreted as providing physical care, but also as fulfilling non-physical care tasks such as emotional support, psychological support and cognitive support (Hardin, 2012; Heydari et al., 2020; Wilkins, Bruce, & Sirey,

2009). It is important that nurses, but also family caregivers and patients, have insight into the different ways in which care can be provided and that providing care does not necessarily mean providing physical care.

Second, this study shows that nurses and patients have a lower attitude towards open visiting hours compared to family caregivers. In the literature several reasons can be found for a lower attitude of nurses towards OVP. First, there is a dichotomy. Nurses do see the benefits of open visiting policy (e.g. better satisfaction, less anxiety and stress of patients and family caregivers, etc.), but these are often outweighed by the disadvantages such as interference with the nurses’ tasks, increased stress of nurses and increased workload (Bélanger et al., 2017; Berti et al., 2007; Ellis, 2018; Hurst et al., 2019; Khaleghparast et al., 2017; Monroe & Wofford, 2017). Second, the beliefs and perceptions that nurses have towards OVP can play an important role. Negative and positive beliefs or perceptions have an impact on determining whether an OVP will be successful. They are especially worried about their possible loss of control, the time visitors would come to the ward and the possibility that visitors would disturb them (Hurst et al., 2019; Khaleghparast et al., 2017). Finally, the lack of confidence can play a crucial role. Some nurses feel that they do not have sufficient communication skills to send family caregivers away at crucial moments (e.g. when they want to perform intimate physical care tasks) (Ellis, 2018; Hurst et al., 2019). Moreover, nurses often do not feel confident enough to perform a care task in front of a family caregiver because they feel like they are under surveillance (Hurst et al., 2019; Monroe & Wofford, 2017).

In addition, there are also possible explanations within the literature on why patients can have a lower attitude towards OVP. Cooper (2008) indicates that the patient's attitude towards visiting hours depends on his or her physical and psychological condition (Cooper et al., 2008). Open visiting hours can disturb patients’ rest and sleep (Bélanger et al., 2017; Berti et al., 2007) and can jeopardise the patients’ privacy (Hurst et al., 2019; Shulkin et al., 2014). Patients are also worried that the nurses will not have enough time to care for them (Berti et al., 2007; Cooper et al., 2008). Open visiting hours can be perceived as

intrusive (Bélanger et al., 2017; Cooper et al., 2008), especially when the patient does not have a close relationship with the visitor (Cooper et al., 2008). However, patients can have a positive perception towards open visiting hours when it comes to their family caregiver or someone that they are close with (Bélanger et al., 2017; Cooper et al., 2008). All these aspects may have influenced the patients when completing the questionnaire.

Within all participating wards there was a closed visiting policy, yet 25.4% of the patients and 43.9% of the family caregivers thought there was an OVP. Possible explanations are that they did not understand or read the definition of OVP in the questionnaire, that they did not get enough information about the visiting policy on the ward or they experienced flexibility from the healthcare team with regard to the open visiting hours although this did not stem from the policy. Currently, there are several frameworks for visiting hours in the healthcare sector (Cooper et al., 2008). This could possibly cause patients and/or family caregivers to be confused (Bélanger et al., 2017).

Finally, the findings within this study indicated that family caregivers experienced a good collaboration with nurses. However the sub-analysis showed that the average score for 'influence on decisions' is lower than the average scores for 'trust in nursing care' and 'accessible nurse’. This could imply that the surveyed family caregivers felt that they had less or limited influence on the decisions that were made. This could be an important area of concern because shared decision-making is seen as one of the components of FCC (Heydari et al., 2020). Family caregivers would like to be actively engaged in the process of decision-making (Kydonaki et al., 2020; Mackie et al., 2019). They want to make shared decisions to ensure that the provided care meets the needs of his or her hospitalised family member (Glose, 2020). This involvement or influence on decision-making can be strengthened by providing valuable information or knowledge, documenting information and adequate communication (Glose, 2020; Lindhardt et al., 2008; Mackie et al., 2019).

Strengths and limitations

This research contains some strengths. First, a consecutive sample was used to recruit patients and family caregivers. Second, this research included nurses, family caregivers and patients, providing a more complete picture of the involvement of family caregivers in the care of their older relative and the attitude towards OVP in a geriatric ward.

Next, this research is not without limitations. First, not all questionnaires (the BAVIQ, the care tasks questionnaire, the satisfaction questionnaire and the single items) were validated within this study. These questionnaires did have face validity. Second, this study excluded patients younger than 75 years. Therefore, it is possible that not all geriatric patients were included in the study as age is not a defining factor of the geriatric profile (Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre, 2015). Third, a Fisher’s exact test was used to analyse the data of the care tasks because combining answer options was not an option. Finally, the researchers helped the patients complete the questionnaires which can lead to a risk of researchers bias. The researchers tried to minimise this risk of bias by using an instrument that visualised the answer options for the patients.

Recommendations for further research

First of all, there is a need for more validated and reliable questionnaires in Dutch within this research domain. Secondly, it can be interesting to conduct interviews with the various stakeholders, followed by organizing focus groups separately. Afterwards, joint focus groups can be organised where all stakeholders are present. This can be done in order to obtain the different visions, attitudes and perceptions towards performing care tasks and OVP. When there is a clear overview of the perspectives of the different stakeholders, it can be examined how a successful implementation project on FCC or OVP can be set up. This can be a first step towards development of a research protocol, which can then possibly be implemented in a geriatric hospital ward.

Relevance for practice

This study is of importance because it is expected that there will be a shift from formal care to informal care where the family caregiver will take care of his or her sick relative (Hagedoorn et al., 2017). This shift can be enhanced by the shortage of qualified nurses (Anker-Hansen, Skovdahl, McCormack, & Tonnessen, 2018). Subsequently, the care that the family caregiver 'has to' provide for a sick relative becomes increasingly complex as the hospital stay becomes shorter and shorter (Hagedoorn et al., 2017). It would not be possible to meet the needs of elderly patients without the help of family caregivers (Feinberg, 2014). Therefore, nurses will need to interact and participate with family caregivers and for that they need confidence and proper communication skills. Currently, communication between family caregivers and nurses still fails too often (Bélanger, Bourbonnais, Bernier, & Benoit, 2016; Mackie et al., 2019). Therefore communication skills of nurses towards family caregivers can be improved (Bhalla, Suri, Kaur, & Kaur, 2014; Hagedoorn et al., 2017; Mackie et al., 2019), which can lead to a better understanding of FCC (Coyne et al., 2011). They need to practice how to effectively communicate with family caregivers, how to involve them into care and how to educate them (Coyne et al., 2011). Overall, it is of utmost importance that nurses and future nurses start to feel competent about the FCC-principles. Therefore, they need more education and training (Coyne et al., 2011).

CONCLUSION

This study gives insight into the care tasks that family caregivers may, can and are willing to perform during a hospital admission, the attitude towards OVP in a geriatric hospital setting and the experienced collaboration of family caregivers with geriatric nurses. Most patients would let their family caregiver perform a large part of the listed care tasks without a nurse being present. The majority of family caregivers would want to participate in many caregiving activities with a nurse or without a nurse, but they were more reluctant to perform intimate care tasks. Nurses had a more dynamic perspective towards the listed care tasks that family caregivers can perform. Furthermore, family caregivers had a better attitude towards open visiting hours than nurses and patients. Overall they experienced a good collaboration with the geriatric nurses. On the subscale 'influence on decisions' a lower score was found compared to the subscales 'trust in nursing care' and 'accessible nurse'. Finally, the family caregivers were more satisfied with the provided care than the patients. Further research needs to concentrate on (i) the development of validated and reliable questionnaires in Dutch within this research domain, (ii) the different visions, attitudes and perceptions towards OVP and performing care tasks through interviews and focus groups and (iii) how a successful implementation project on OVP or FCC can be set up.

REFERENCES

Anker-Hansen, C., Skovdahl, K., McCormack, B., & Tonnessen, S. (2018). The third person in the room: The needs of care partners of older people in home care services - A systematic review from a person-centred perspective. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(7-8), e1309-e1326. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14205

Art. 160, GECOÖRDINEERDE WET van 10 mei 2015 betreffende de uitoefening van de gezondheidszorgberoepen, Belgisch staatsblad, 30 april 2014, 35172.

Auslander, G. K. (2011). Family caregivers of hospitalized adults in Israel: a point-prevalence survey and exploration of tasks and motives. Research in

Nursing & Health, 34(3), 204-217. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20430

Bélanger, L., Bourbonnais, A., Bernier, R., & Benoit, M. (2016). Communication between nurses and family caregivers of hospitalised older persons: A literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26, 609-619. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/jocn.13516

Bélanger, L., Bussières, S., Rainville, F., Coulombe, M., & Desmartis, M. (2017). Hospital visiting policies - impacts on patients, families and staff: A review of the literature to inform decision making. Journal of Hospital

Administration 6(6), 51-62. https://doi.org/10.5430/jha.v6n6p51

Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre. (2015). Comprehensive geriatric care in

hospitals: The role of inpatient geriatric consultation teams. Retrieved from

https://kce.fgov.be/sites/default/files/atoms/files/KCE_245Cs_geriatric_ca re_in_hospitals_Synthesis.pdf

Berti, D., Ferdinande, P., & Moons, P. (2007). Beliefs and attitudes of intensive care nurses toward visits and open visiting policy. Intensive Care

Medicine, 33(6), 1060-1065. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-007-0599-x

Bhalla, A., Suri, V., Kaur, P., & Kaur, S. (2014). Involvement of the family members in caring of patients an acute care setting. Journal of

Postgraduate Medicine, 60(4), 382-385.

https://doi.org/10.4103/0022-3859.143962

Boltz, M., Resnick, B., Chippendale, T., & Galvin, J. (2014). Testing a family-centered intervention to promote functional and cognitive recovery in hospitalized older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society,

62(12), 2398-2407. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13139

Bookman, A., & Harrington, M. (2007). Family caregivers: a shadow workforce in the geriatric health care system? Journal of Health Politics, Policy and

Law, 32(6), 1005-1041. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-2007-040

Bridges, J., Collins, P., Flatley, M., Hope, J., & Young, A. (2020). Older people's experiences in acute care settings: Systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 102, 89-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103469

Brodaty, H., & Donkin, M. (2009). Family caregivers of people with dementia.

Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(2), 217-228.

Ciufo, D., Hader, R., & Holly, C. (2011). A comprehensive systematic review of visitation models in adult critical care units within the context of patient- and family-centred care. International Journal of Evidence-Based

Healthcare, 9(4), 362-387. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-1609. 2011.00229.x

Collins, L. G., & Swartz, K. (2011). Caregiver care. American Family Physician,

83(11), 1309-1317.

Cooper, L., Gray, H., Adam, J., Brown, D., McLaughlin, P., & Watson, J. (2008). Open all hours: a qualitative exploration of open visiting in a hospice.

International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 14(7), 334-341. https://doi.org/

10.12968/ijpn.2008.14.7.30619

Coyne, I., O'Neill, C., Murphy, M., Costello, T., & O'Shea, R. (2011). What does family-centred care mean to nurses and how do they think it could be enhanced in practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(12), 2561-2573. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05768.x

Ellis, P. (2018). The benefits and drawbacks of open and restricted visiting hours.

Nursing Times, 114(12), 18-20.

Engström, B., Uusitalo, A., & Engström, A. (2011). Relatives' involvement in nursing care: a qualitative study describing critical care nurses' experiences. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 27(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2010.11.004

Feinberg, L. F. (2014). Moving toward person- and family-centered care. Public

Policy & Aging Report, 24(3), 97-101. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppar/pru027

Garrouste-Orgeas, M., Willems, V., Timsit, J. F., Diaw, F., Brochon, S., Vesin, A., ... Misset, B. (2010). Opinions of families, staff, and patients about family participation in care in intensive care units. Journal of Critical Care, 25(4), 634-640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.03.001

Glose, S. (2020). Family caregiving during the hospitalization of an older relative.

Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 46(3), 45-50. https://doi.org/10.3928/

00989134-20200129-04

Hagedoorn, E. I., Paans, W., Jaarsma, T., Keers, J. C., van der Schans, C., & Luttik, M. L. (2017). Aspects of family caregiving as addressed in planned discussions between nurses, patients with chronic diseases and family caregivers: a qualitative content analysis. BMC Nursing, 16, 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-017-0231-5

Hagedoorn, E. I., Paans, W., Jaarsma, T., Keers, J. C., van der Schans, C. P., Luttik, M. L. A., & Krijnen, W. P. (2019). Psychometric evaluation of a revised family collaboration scale. Geriatric Nursing (New York, N.Y.),

40(5), 463-472. htpps://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2019.02.003

Hardin, S. R. (2012). Engaging families to participate in care of older critical care patients. Critical Care Nurse, 32(3), 35-40. https://doi.org/10.4037/ ccn2012407

Heck, R. H., Thomas, S., & Tabata, L. (2012). Multilevel modeling of categorical

Hetland, B., Hickman, R., McAndrew, N., & Daly, B. (2017). Factors influencing active family engagement in care among critical care nurses. AACN

Advanced Critical Care, 28(2), 160-170. https://doi.org/10.4037/

aacnacc2017118

Hetland, B., McAndrew, N., Perazzo, J., & Hickman, R. (2018). A qualitative study of factors that influence active family involvement with patient care in the ICU: Survey of critical care nurses. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing,

44, 67-75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2017.08.008

Heydari, A., Sharifi, M., & Moghaddam, A. B. (2020). Family participation in the care of older adult patients admitted to the intensive care unit: A scoping review. Geriatric Nursing (New York, N.Y.). https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.gerinurse.2020.01.020

Hurst, H., Griffiths, J., Hunt, C., & Martinez, E. (2019). A realist evaluation of the implementation of open visiting in an acute care setting for older people.

BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 867. https://doi.org10.1186/

s12913-019-4653-5

Jaeger, T. F. (2008). Categorical data analysis: Away from ANOVAs (transformation or not) and towards logit mixed models. Journal of Memory

and Language, 59(4), 434-446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2007.11.007

Kelley, R., Godfrey, M., & Young, J. (2019). The impacts of family involvement on general hospital care experiences for people living with dementia: An ethnographic study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 96, 72-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.04.004

Khaleghparast, S., Joolaee, S., Maleki, M., Peyrovi, H., Ghanbari, B., & Bahrani, N. (2017). Patients' and families' satisfaction with visiting policies in cardiac intensive care units. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 36(3), 202-207. https://doi.org/:10.1097/dcc.0000000000000247

Kokorelias, K. M., Gignac, M. A. M., Naglie, G., & Cameron, J. I. (2019). Towards a universal model of family centered care: a scoping review. BMC Health

Services Research, 19(1), 564.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4394-5

Kydonaki, K., Kean, S., & Tocher, J. (2020). Family INvolvement in inTensive care: A qualitative exploration of critically ill patients, their families and critical care nurses (INpuT study). Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(7-8), 1115-1128. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15175

Laitinen-Junkkari, P., Merilainen, P., & Sinkkonen, S. (2001). Informal caregivers' participation in elderly-patient care: an interrupted time-series study.

International Journal of Nursing Practice, 7(3), 199-213. https://doi.org/

10.1046/j.1440-172x.2001.00274.x

Lindhardt, T., Nyberg, P., & Hallberg, I. R. (2008). Collaboration between relatives of elderly patients and nurses and its relation to satisfaction with the hospital care trajectory. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 22(4), 507-519. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00558.x

Liput, S. A., Kane-Gill, S. L., Seybert, A. L., & Smithburger, P. L. (2016). A review of the perceptions of healthcare providers and family Members toward family involvement in active adult patient care in the ICU. Critical Care

Medicine, 44(6), 1191-1197. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm. 0000000000001641

Mackie, B. R., Mitchell, M., & Marshall, A. P. (2019). Patient and family members' perceptions of family participation in care on acute care wards.

Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 33(2), 359-370. https://doi.org/

10.1111/scs.12631

McConnell, B., & Moroney, T. (2015). Involving relatives in ICU patient care: critical care nursing challenges. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(7-8), 991-998. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12755

Monroe, M., & Wofford, L. (2017). Open visitation and nurse job satisfaction: An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(23-24), 4868-4876. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13919

Moyle, W., Bramble, M., Bauer, M., Smyth, W., & Beattie, E. (2016). 'They rush you and push you too much ... and you can't really get any good response off them': A qualitative examination of family involvement in care of people with dementia in acute care. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 35(2), E30-34. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12251

Nationaal Verbond van Katholieke Vlaamse Verpleegkundigen en Vroedvrouwen [NVKVV]. (2015). Wetgeving - Beroepsuitoefening. Retrieved from https://www.nvkvv.be/page?pge=51&ssn=&lng=1

Nayeri, N. D., Gholizadeh, L., Mohammadi, E., & Yazdi, K. (2015). Family involvement in the care of hospitalized elderly patients. Journal of Applied

Gerontology 34(6), 779-796. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464813483211

Pena, S. B., & Diogo, M. J. (2009). Nursing team expectations and caregivers' activities in elderly-patient hospital care. Revista da Escola de

Enfermagem da USP, 43(2), 350-360.

https://doi.org/10.1590/s0080-62342009000200014

Riffin, C., Van Ness, P. H., Wolff, J. L., & Fried, T. (2017). Family and other unpaid caregivers and older adults with and without dementia and disability.

Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(8), 1821-1828. https://

doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14910

Shulkin, D., O'Keefe, T., Visconi, D., Robinson, A., Rooke, A. S., & Neigher, W. (2014). Eliminating visiting hour restrictions in hospitals. Journal for

Healthcare Quality 36(6), 54-57. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhq.12035

Twisk, J. W. R. (2016). Inleiding in de toegepaste biostatistiek (4 ed. Vol. 4). Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

Wilkins, V. M., Bruce, M. L., & Sirey, J. A. (2009). Caregiving tasks and training interest of family caregivers of medically ill homebound older adults.

Journal of Aging and Health, 21(3), 528-542. https://doi.org/