Martin Godts

Student number: 19804004

Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Miriam Taverniers

A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the

degree of Master of Advanced Studies in Linguistics - Linguistics in a Comparative

Perspective.

Academic year: 2019 – 2020

ERGATIVE STRATEGIES OF FREQUENTLY USED VERBS

IN ENGLISH, GERMAN, FRENCH, DUTCH AND DANISH

Ergative strategies of frequently used verbs in English,

German, French, Dutch and Danish

A corpus based comparison

Martin Godts

word count 45864(*)

v29c / August 15, 2020

i

Acknowledgements

After I graduated in 1978 I got married, got a job, got children, a house and pretty much

everything else one can wish for.

After a varied and satisfying career I retired in 2019 and now I can fulfil my final dream : go

back to university and catch up with linguistics. Language is so fascinating!

This year has been great. I have enjoyed the courses so much, the university is still the place

to be.

I can only thank my wife, my mum, my children, my grandchildren for supporting me.

Especially my grandchildren take an interest in ‘opa’ going to school : I’m one of them now.

Studying, reading and researching was very satisfying. I went to bed with many authors,

reading their books and papers and waking up the next morning with fresh knowledge and

new ideas. During this period Covid19 struck. It has been on my mind for two and a half

months blocking my work. On May 31 I was able to resume the writing of this thesis.

My personal research led to new insights every day. This kept me going and wondering and

asking myself new questions about the processes involved in language specifically in the

context of this thesis, but also in general.

A special thanks to my promoter, professor Taverniers : she is a talented teacher and a great

guide. I also thank professor Van Peteghem : she is a great motivator. The same goes for

professor Davidse – I only met her once, but it was an awestriking and stimulating

experience. Thanks to the board of professors who read my first draft. Their constructive

comments have been a great help.

ii

Contents

Contents

Appendix 1 (including electronic documents) Appendix 2 List of Abbreviations List of Tables List of Figures Preface 1. Some information 2. Possible Issues Introduction Part 1 – Framework 1. Introduction

2. Verbs, subjects and objects

3. Transitive and intransitive use of verbs 4. Ambi-transitive verbs

5. The passive voice 6. Valency and transitivity 7. Transitivity and semantics

8. Cross-linguistic comparison of default forms of verbs in active and passive voice

9. The role of aspect

10. Ergative, middle and passive constructions 11. Ergativity

12. Ergativity cross-linguistically in German, French, Dutch and Danish 13. Summary of popular concurrent forms of ‘open’ (V+adj) per language 14. Other cross-linguistic approaches

15. To alternate or not? 16. To alternate

Part 2 – Data Collection

Section 2.1 Methodology 1. Introduction : corpora used

2. Establish a ranking of frequently used verbs in English

3. Establish a ranking of frequently used verbs in German, French, Dutch and Danish

4. Make the data on ergative verbs in English available

5. Match the main English ergative verbs with their translation equivalent in German, French, Dutch and Danish

6. Establish a cross-linguistic ranking of these verbs 7. Make a selection for analysis

Section 2.2 Selection

i

iii

iii

iv

vi

vii

1 2 4 6 7 8 9 9 10 11 12 14 15 17 19 20 21 23 24 26 26 27 28 28 29 29 30 31iii Part 3 – Research and analysis

Section 3.1 Methodology 1. Introduction

2. A first dataset is general, using general agents / media / patients 3. A second dataset is constructed, using frequently used mediums and

he/she as instigator

4. A third dataset uses obvious collocates, in this case mediums that show up about equally frequent as subject and as object in English 5. Translating the datasets

6. Data storage

7. Focus of the study and possible issues with machine translation 8. MS-Access proceedings

9. Introduction of aspect as part of the ergative strategy Section 3.2 Analysis and observations

3.2.1. Features per Language 1. English

2. German 3. French 4. Dutch 5. Danish

3.2.2. Cross linguistic Statistics 1. Basic strategies

2. Cross-linguistic labile strategies

3. Cross-linguistic anticausative strategies 4. Cross-linguistic resultative strategies

5. Cross-linguistic strategies matched with semantic clusters 3.2.3. Cross-linguistic Structural Interpretation

1. Structural Variation in Transitive clauses 2. Structural Variation in Intransitive clauses 3. Structural Variation in Alternations 3.2.4. Cross-linguistic Semantic Comparisons 1. {‘open’, ‘close’, ‘shut’} cluster

2. {‘begin’, ’start’, ’stop’, ’end’, ’finish’, ’continue’} cluster

3. {‘change’, ’turn’, ’develop’, ’increase’, ’improve’, ’decrease’} cluster 4. {‘break’, ‘crack’, ’rip’, ’split’, ’tear’, ’burn’} cluster

5. {‘play’, ‘run’, ‘move’, ‘download’} cluster 6. Overviews Part 4 – Conclusions References 35 35 35 36 36 38 38 40 40 45 48 49 49 53 56 59 62 65 65 66 67 68 69 70 70 77 88 91 91 93 96 99 103 105 108 112

iv

Appendix 1

Contents

Appendix (separate document)

1 Ergative verbs - McMillion’s List & Collins’s List

2 Selection - Cross-linguistic list of frequently used verbs linked to list of Ergative verbs / Including Ranking-Score

3 Pilot study based on Internet Verb Frequency Lists

4 Frequently used mediums

Extra (electronic documents) 1 eCorpora : MS-Access Database 2 AnaData2v2 : MS-Access Database

3 Dataset translations ANA3 : MS-Excel Worksheet 4 Rawdata eStrategies : MS-Excel Worksheet 5 Calc : MS-Excel Worksheet

Notice: All documents including the databases and the worksheets are available a) At this URL : MASTERPROEF MGODTS 2020 DATA ONLINE

b) https://1drv.ms/u/s!Ai7ZUc-IF2uIpHb7M2Xj7dhH1MU0?e=Vv8u9H

(or copy and paste link into your browser) c) Via e-mail to martin.godts@ugent.be

1 40 67 69

Appendix 2

Contents DatasetsDataset 1 : general, using general agents / media /patients

Dataset 2 : constructed, using frequently used mediums and he/she as instigator Dataset 3 : collocates, in this case mediums that show up about equally frequently as subject and as object in English.

Table – Edited Cross Linguistic overview of verbal entries in the eStrategies table Edited Table – Splitdata v2 (original table available in the MS-Access database AnaData2v2)

Comparative table - Structural Variation in Alternations

2 2 3 4 6 12 38

v

List of Abbreviations

A (A) AC AD Adj AP APA APC A/P APP ASP BA BAD BI BP BPP BPV BPS BNC C (C) (CP) D D1,D2 etc. DC E (E) EC EPP F FC G GC (HR) L LAB L1 L2 MT N NC NLA NMT NP np, non-periph O agent active voice anticausativebe + past participle : f(adj) adjective

adverbial phrase active simple past active present continuous voice syncretism

active present perfect (have) active simple present be + adjective be + adverb be + idiom phrase be + past participle active present perfect (be) se + BP

BP + PP

British National Corpus causative continuous (aspect) perfective Danish derivation Danish corpus English eternal, timeless English corpus

reflexive present perfect (have) French French corpus German German corpus repeated actions labile

labile alternation possible Native speakers Non-native speakers Machine Translation noun, Dutch Dutch corpus non-labile ergative neural machine translation noun phrase non-periphrastic object Codes: **** *** ** * Worksheets: COL-D COL-DEEPL COL-G COL-GOOGLE CON-D CON-DEEPL CON-G CON-GOOGLE GEN-D, GEN-DEEPL GEN-G, GEN-GOOGLE <- -> verb ‘verb’ tense ‘tense’ {…} f(…) ∩ main/major, 80-100% important, 50-80% less important, 20-50% 1 or a few, 5-20% Collocates-DeepL MT Collocates-DeepL MT Constructions-DeepL MT Constructions-Google MT Generalizations-DeepL MT Generalizations-Google MT precedence result verb in English meaning of verb tense in English equivalent tense set, collection function cross-section

vi OANC OTT OVT P p, periph (P) (PA) pAC PAS PAP PI pLAB PP PP PPV (PR) PSP (trans.) PSP (intrans.) PSV PV R (verb) R (strategy) RBP RSP S S (strategy) (S) SC SHT SP SPP SPS SPV SV strat V VP vp VTT

Open American National Corpus simple present (Dutch)

simple past (Dutch) patient

periphrastic passive voice past tense

prototypical AC alternation agentless passive alternation passive auxiliary + Past Participle verbal idiom

prototypical labile alternation prepositional phrase

present perfect + PP present perfect + VP present tense simple past + PP simple present passive simple past + VP phrasal verb root resultative

reflexive present perfect (be) reflexive simple present subject

suppletive simple (aspect) structural change ergative strategy switch s-passive

simple present + PP simple present + s-suffix simple present + VP suffixed verb strategy verb verb phrase verbal particle

vii

List of tables

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48Shares in WWW-content, L2 and L1 speakers as global percentages Unaccusative verbs and alternations

Comparison of agentive S + V Comparison of intransitive S + V Comparison of passive voice S + V

Comparison of be + adjective / adjective + N

Tense and aspect, examples and main T(ense)- and A(spect)-use Verbs in clause alternations according to Haspelmath (1993: 91-92)

Strategies in German, French and English according to Haspelmath (1993: 101) Corpora used in this study

Selection of English verbs, exemplary for the cross-linguistic meaning Ranking of cross-linguistic meanings as they appeared

Initial cross-linguistic dataset

Scores Quality of Translation from and to English Record-structure eStrategies table

Cross-linguistic overview of verbal entries in the eStrategies table # of Entries in eStrategies table

English dataset VPs from eStrategies table through QeSynonyms English query Summary of occurrence of VPs in English selection

Common English ergative strategies in this selection

German dataset VPs from eStrategies table through QeSynonyms German query Common German ergative strategies in this selection

French dataset VPs from eStrategies table through QeSynonyms French query Common French ergative strategies in this selection

Dutch dataset VPs from eStrategies table through QeSynonyms Dutch query Common Dutch ergative strategies in this selection

Danish dataset VPs from eStrategies table through QeSynonyms Danish query Common Danish ergative strategies in this selection

Basic ergative strategies as they occur cross-linguistically Be+f(adj) perfective alternatives cross-linguistically

Implementation of causative and anticausative alternations Meanings with cross-linguistic labile strategies in all languages Meanings with cross-linguistic labile strategies in four languages Meanings with cross-linguistic anticausative strategies

Meanings with cross-linguistic resultative strategies in most languages Summary of cross-linguistic strategies matched with semantic clusters Clause structure of the original English clauses

Summary of tense use in the transitive clauses of this research Overview of all VP occurrences in the transitive clauses

German ‘Reflexive’ Active Present Perfect with haven as auxiliary as observed in anticausative clauses

‘Active Present Perfect’ with ‘be’-VPs in anticausative intransitive clauses in German, French, Dutch and Danish

VPs in intransitive clauses in French with être as auxiliary and with and without se insertion Cross-linguistic ‘be + past participle’ : f(adj) aka passive simple present syncretism

‘Be’ + adjective/adverb occurrences in intransitive clauses Overview of all VP occurrences observed in intransitive clauses Cross-linguistic counts of potential ergative strategies

Frequently used mediums with ‘open’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘close’ across languages

viii 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73

Frequently used mediums with ‘shut’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘begin’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘start’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘stop’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘end’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘finish’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘continue’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘change’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘turn’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘develop’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘increase’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘improve’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘decrease’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘break’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘crack’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘rip’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘split’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘tear’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘burn’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘play’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘run’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘move’ across languages Frequently used mediums with ‘download’ across languages Translation equivalents correspondence ranking

Cross-cluster comparison of frequently used mediums in ergative alternations

List of Figures

1 2 3 4 5Western Europe, the cradle of the languages compared The lexicogrammar cline from Halliday 1994: 64 – fig. 2.6 Table Selection (Selectie) – Sample of Selection

Data streams between Data sources, corpora and selections Example of collocates retrieval using Sketch Engine

1

Preface

This is a functional and typological comparative study of lexical ergativity in English, German, French Dutch and Danish built around a selection of frequently used verbs and their translation equivalents across these languages. Essential in my approach is that I focus on the use and the cross-linguistic meanings of the verbs involved since lexical ergativity is primarily linked to meaning as Levin (1993) and Levin and Rappaport (1994) pointed out.

Any dictionary can exemplify that verbs by default generate specific, possibly multiple, meanings in relation to the collocates they are used with. In the context of lexical ergativity the medium, either functioning as subject or object to the verb, is the determining factor. Depending on their mutual grammatical and lexical restrictions and finetuned by the overall context, language users combining a verb with a medium, create one or more concrete or abstract meanings, either imaginable and understandable or cryptic and confusing and in both cases possibly, but not necessarily,

grammatically correct.

1. Some information

As commonly known, French is a Romance language and English, German, French and Dutch are Germanic languages. The countries where these languages are spoken form one contiguous area and at one time or another, often for longer periods in the last two millennia, two or more of these

2 countries used to be part of a larger kingdom or empire where people lived together, traded and waged wars with or against each other. In addition, they have shared languages, culture, history, religion and many other things. This area has had - and still has - a lot of language contact and since multilingualism is of all times, it is not uncommon to know at least the basics of all five languages, which is a prerequisite to endeavor a comparative linguistic study.

The importance of English as a first language is clear – this is where the UK and its present and former Commonwealth realms and the United States come in - but it is also the main second and foreign language of this planet. Hence it is no coincidence that this thesis is written in English. Neither is it a coincidence that I use English as an access to the features of the other languages because much more has been written in English on these features than in any other language. Additionally, internet data play an important role in this study and since it is obvious there is much more web contents in English than in any other language I choose to start from an extensive collection of English labile verbs in lexical ergative alternations, match these verbs with their

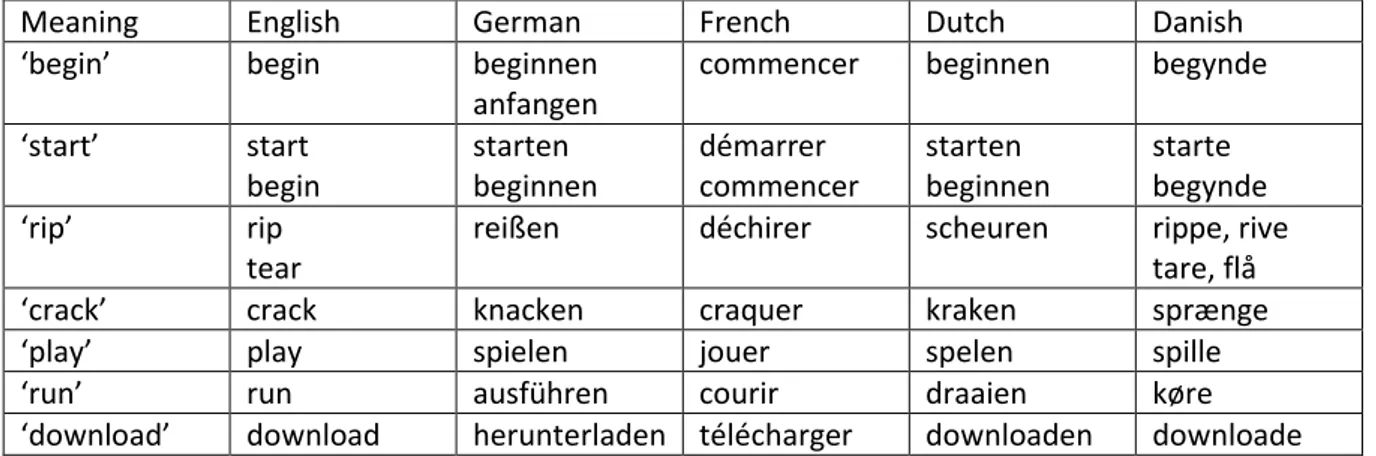

translation equivalents in the other languages and rank them cross-linguistically on the basis of their frequency of use in web-based corpora, in order to obtain a selection of about 25 common verb meanings that are potentially ergative.

These verbs are used in alternating clauses where each language is used in turn as source language to translate the clauses into the target languages and back. I compare the strategies that emerge and embed my observations through a comparative frequency analysis in a theory of ergative strategies as it will be developed in the next chapters, confirming and extending the status quaestionis on this topic. The goal of this comparative study is to describe ergative strategies, confirm linguistic features and make a personal analysis of lexical ergativity and adjacent concepts. In my conclusion I will plea to broaden the contemporary view on lexical ergativity to include strategies that emerge from translation equivalence and linguistic syncretism.

This research is one on the use of languages and consequently the data are collected from systems that are based on user input of many users and many written sources. Both the users and the sources comprise all levels and proficiencies of language. Nonetheless, most of it is acceptable language, at least for functional linguists who focus on the actual language use. In this respect, I am a linguistic miner, for I consider language a public tool to be combined with a repository of all kinds of linguistic resources.

2. Possible issues

Some background information and a broader perspective seems apt, especially because of possible issues with the methodology used.

There are parts of the world, where most people do not understand English, German, French, Dutch or Danish, but according to the records of Infoplease1, at least one of these languages is spoken in

70% of the countries in the world2, either as a first, a second or a foreign language. Add tourist

1 As retrieved from Infoplease, part of the FEN Learning family of educational and reference sites

https://www.infoplease.com/world/countries/languages-spoken-in-each-country-of-the-world on July 2 2020.

2 If you know just 9 languages, they will understand you in 90% of the countries: forget about Danish (even

most Danes speak English or German), but add Arabic, Russian, Spanish, Portuguese and Turkish. If you want to speak to as many people as possible, just learn these 8 languages: English, Mandarin Chinese, Hindi, Spanish, Arabic, Russian, Japanese and Swahili. This accounts for 56% of the world population. (my estimates on the basis of the data)

3 guides, business people and professors and you get 100%. English is spoken in half the countries of the world, French in 25% and German in 7% of the countries, Dutch and Danish are spoken in a handful of countries. SIL International3 has data on the global number of speakers and according to

their 2019 edition between 1.3 and 2 billion people speak4 English, depending on the criteria chosen.

Additionally, about 275 million people speak French and 130 million speak German, there are close to 30 million speakers of Dutch and approximately 6 million people speaking Danish.

In contrast, there are only about 380 million native English speakers, that is a little less than 5 % of the world population and French (80 million) and German (79 million) are each spoken natively by just 1% of the world. This implicates that at least 70% of English and French and 40% of German is not spoken natively. However, only about 17% of Dutch and less than 4 % of Danish is spoken by non-native speakers.

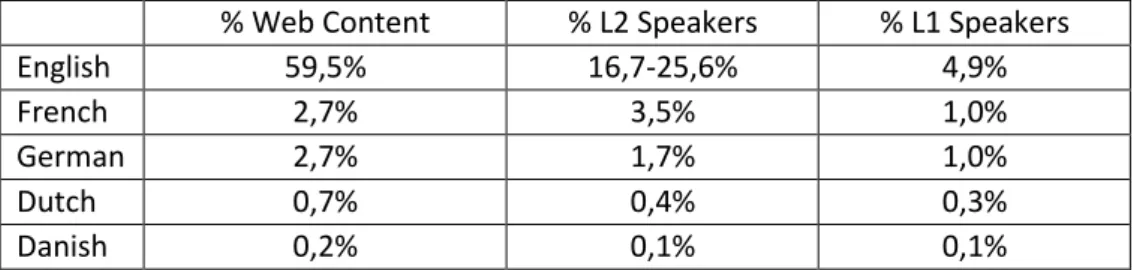

Finally, W3Tech.com has data on the content languages for websites5 and apparently 59.5% of all

content is in English, 2.7% is in German and 2.7% is in French, 0.7% is in Dutch and 0.2% is in Danish. The next table summarizes the main data retrieved:

Table 1 - Shares in WWW-content, L2 and L1 speakers as global percentages

% Web Content % L2 Speakers % L1 Speakers

English 59,5% 16,7-25,6% 4,9% French 2,7% 3,5% 1,0% German 2,7% 1,7% 1,0% Dutch 0,7% 0,4% 0,3% Danish 0,2% 0,1% 0,1% My observations are:

1. The percentage of English web content is disproportionate to the percentage of English L1s in the world.

2. There are many more English, French and German L2s than there are L1s. 3. Dutch and Danish are mainly used by L1s

4. The amount of web content in French and German corresponds with the number of L1s. 5. English is a “main” language. French and German are “important” languages and their L1s

each represent 1% of the world population. Dutch and Danish are “less important” on a world scale.

It is not part of this paper to interpret these data, but they illustrate a possible effect on my methodology since I use web-based corpora and machine translation on the basis of translated datasets. Table 1 illustrates that for English, French and German a substantial part of the data must have been provided by non-native speakers. There is no way to exclude second language or foreign language users but I explain in part 2, description of my methodology, how I deal with possible threats and biases.

3 As retrieved from Etnologue.com on July 2 2020.

4 And not everyone can read or write English or the other languages...

4

Introduction

On our first meeting, professor Taverniers inquired if I was acquainted with the concept of ergativity in English. I was not. She gave an example: John opened the door./ The door opened.

The object of the first sentence becomes the subject of the second sentence. It is as if the door now performs the action by itself… This type of alteration is quite common in English she said.

How would you say that in Dutch?

I tried, John opent de deur. De deur opent… I mused… No, that is not what we say… We say De deur

gaat open!

And in German? I tried again… John öffnet die Tür… I hesitated… Die Tür öffnet sich… Right!

I thought of French, Il ouvre la porte. / La porte s’ouvre , and Danish, Han åbner døren. Døren åbnes. At that moment, it struck me, that in the languages I know, in each of them we express this in a different way.

The seminar about ergativity was a real eye-opener since I had never been aware of this

phenomenon and it intrigued me. I discovered soon that a lot had been written about this topic in the last thirty years. In fact, it was one of the most studied alternations. As a consequence, my curiosity grew.

I developed this further in a course paper that focused on ten English verbs, which according to the literature were prototypical for this alternation. I used them in 10 common clauses and studied the translation equivalents in English, German, French, Dutch and Danish. Often, there were alternative translations, some preferred, others less frequent or uncommon. It also became clear to me, that the role of the object/subject – by that time I was talking about the “medium” -, was essential in allowing the alternations: one can easily say He opens the door / the door opens, but He opened the

bottles / The bottles opened seems not acceptable, or at least not without additional context or

phrase. The bottles opened in shipping would do in a certain, imaginable context. In other words, prototypical lexical ergativity seems to be restricted, not only to a limited number of verbs, mainly expressing a change of state, but also to a limited set of mediums that can function in this

configuration. Expanding the clause with a prepositional object might help somewhat, as exemplified above and in Collins Cobuild data concerning ergativity, where about half of the constructions include a prepositional object, but very soon one reaches the limits of the ergative configurability since with a lot of verbs, either originally transitive or intransitive, it is hard to find more than a few convincing examples of the alternate form with the same medium.

Studying alternations is a linguistic technique that can lead to new insights. Concerning the ergative alternation, also known as the causative-anticausative alternation, this might even mimic a common type of reasoning where one first describes an event including all participants and thereafter the resulting state omitting the actor-instigator to shift the focus to the medium-patient. The choices between expressing something in either a causative transitive way, an anticausative intransitive manner, as a perfective or resultative state or in an active dynamic fashion seem comparable purpose-driven thought strategies. Consciously or unconsciously we all attempt to use the right words in a fitting way in a specific situation.

5 In this dissertation I continue my research. The research questions I want to answer are these:

What are the main6 and alternative ergative strategies of English, German, French, Dutch and

Danish? How important/productive is each strategy in each language? How do they compare? How do they translate? How much (in)consistency does this involve? To what extent does meaning in a general or specific lexical context play a role? and Is there anything in this comparison that sheds new light on lexical ergativity?

In the first part I situate ergativity in terms of grammar, in order to sketch a clear picture of the grammar involved and develop a few cross-linguistic issues. In a second part I select the data for my comparison. In my methodology I use four corpora for English and two corpora for each other language via the Sketch-Engine interface. I determine which verbs that have ergative alternations in English are most frequently used in the languages of this research. To confirm their ergative use I match the English verbs with McMillion’s list (2006) and the list of the online Cobuild Dictionary (1996-2020). From this collection I select 25 verbal meanings and their translation equivalents in each language. The fact that the verbs are chosen on the basis of frequency does not guarantee the display of more ergative meanings. On the other hand, more use could also imply more possible mediums and contexts. Whatever the result, I am confident this approach has a potential to deliver new insights.

In a third part I build a datasheet collection with the verbs from the second part used in general clauses, constructed clauses and clauses with common collocates showing up in both transitive and intransitive clauses. In order to obtain reliable user data, I use three online translators (Google Translate, Bing Translation and DeepL) that make use of user input and NMT7 technology. I translate

back and forth between these systems in search of (in)consistencies. I import the data for further processing into a database management system and use relational query techniques to retrieve and analyze the data, confirming “typical” ergative strategies, but also eliciting particular alternative strategies. All this leads to a series of observations and conclusions concerning the ergative strategies in each language in our comparison. Additionally, I rank all strategies involved, interpret my observations and elaborate on the similarities and contrasts between the languages. In a final section I concentrate on the specific use of each cross-linguistic meaning and exemplify that a discussion of medium context, object properties and tense and aspect of the events, states or processes is relevant.

6 ‘Main’ in terms of frequency: I will first determine which verbs are mainly used cross-linguistically in an

ergative context. I will show how to build a cross-linguistic dataset of frequently used verbs.

6

Part one – Framework

1. Introduction

In this chapter I sketch the framework in which this research is embedded. I owe much to the insights of descriptive linguistics (Jespersen, Curme) , the approach of Comrie on aspect, the innovative system of functional linguistics (Halliday, Davidse, Taverniers), the ergative topology of Dixon, Haspelmath’s method of illuminating causative/inchoative alternations and his recent paper on depth of analysis, the data on English lability by McMillion and in Collins Cobuild Dictionary and ultimately the broadening view of Abraham on linguistic syncretism.

After the introduction of verbs in relation to objects and subjects, I zoom in on different types of transitive and intransitive clauses and alternations, involving transitivity, valency, voice, tense, aspect and semantics. I then frame the concept of ergativity as it will be applied cross-linguistically in this research and describe some other cross-linguistic approaches. Eventually, with Davidse, I explore and underwrite the arguments in favor of a semantic corpus-based approach of lexical ergativity.

The linguistic framework of this study starts with the Danish descriptive linguist Otto Jespersen (1860-1943) whose basic grammatical concepts concerning transitive and intransitive verbs form a first level in my approach.

In 1978, when I graduated from this university, transformational grammar was mainstream. I still think universal grammar is a challenging concept, but discovering aspects of systemic functional grammar opened up a new world that appeals to me because I can identify with Halliday’s key concepts. Halliday, a student of J.R. Firth, an English linguist and the first professor of general linguistics in Great Britain, owed him the idea that language is a system with a set of choices. Just like Firth (London School) and Malinowski (Prague School), Halliday puts context of situation central in his view of language. In addition, he claims his grammar is functional because it relates to language use. Besides, meaning in language consists of functional components and he goes on specifying that “each element in a language is explained by reference to its function in the total linguistic system”(Halliday 1994: xiii-xiv). In that respect, all grammars are functional, which sounds like de Saussure saying “Language is a system of interdependent terms in which the value of one term results solely from the simultaneous presence of the others.”(de Saussure 1915,1959: 114) Further, language consists of “levels” (Berry 1975) and one of these levels is the form of the language. This form consists of grammar and lexis.

Halliday (1961, 1994), who distinguishes 5 levels of descriptive analysis (phonic, phonological, grammatical, lexical and contextual), considers lexis and grammar as the two poles of a single cline, continuum or unity. In this continuum, grammar on one end is a closed system, general in meaning and general in its description of language structure, lexis on the other end consists of open sets, specific in their meaning due to the collocation of words in a stratum (or layer) of wording. (Halliday 1994: 64) – see figure from the same source on the next page:

7

Figure 2 – The lexicogrammar cline from Halliday 1994: 64 – fig 2.6

Additionally, lexical items can be classed as belonging to 8 word classes: noun, determiner, adjective, numeral, verb, preposition, adverb, conjunction and each class can consist of subclasses, e.g. noun {proper noun, common noun, pronoun} while grammar and grammatical rules continue to be important and form the core of the structure of both spoken and written language. However, it is accepted that the rules, especially in spoken grammar, may be variable to a certain extent. (Carter 1998: 51)

2. Verbs, subjects and objects

Jespersen (1933: 74-77) already refers to the complex relation between verbs, subjects and objects when he points out that some verbs denote actions, that others express some kind of “suffering” (ibid.: 74) on the part of the subject and that some other verbs can do both (1a-b).

(1a) He broke a twig. Verb denotes action.

(1b) He broke a leg. Verb denotes suffering.

Some verbs he thinks of as “double faced in a curious way” (ibid.: 74) e.g. ‘The garden swarms with bees.’ approximately meaning the same as ‘Bees swarm in the garden.’ In his view, subjects are “intimately” (ibid.: 75) connected with the verb and objects are too, but less intimately i.e. the connection is indirect, there is more distance. To find the subject of (2a), you just take the <verb> as it used in the clause and ask Who or What <verb>? (ibid.: 66, example 2b) while to find the object, you have to rephrase the question and include the subject in the question as an intermediate: Who

does <subject> <verb> ? (ibid.: 75, example 2c) or, in the case of a prepositional object functioning as

a temporal adverbial, include both the subject and the object as intermediates in the question and ask When <does> <subject><verb><object>? (ibid.: 75, example 2d)

(2a) He kisses his wife in the morning. (2b) Who kisses? He.

(2c) Who does he kiss? His wife.

(2d) When does he kiss his wife? In the morning.

He claims that with every other object the meaning of the verb can be different (ibid.: 75). Consequently, it is not possible to define the relation of verb and object in a simple way. To strengthen his claim he distinguishes various objects of result (3a-f) and also exemplifies verbs that can be used alternatively with an object or a prepositional phrase (4a-b).

(3a) John wrote a letter.

(3b) We picked flowers / a quarrel. (3c) I dreamt a curious dream.

(3d) He entered a house / his name in a list. (3e) He waited his turn / dinner.

8 (4a) We know him / of him.

(4b) We meet a person / in person / all claims / with him / with an accident. 3. Transitive and intransitive use of verbs

If a verb has an object, we call it transitive, otherwise it is intransitive. In English many verbs can be used both transitively and intransitively, which Jespersen (1933: 82-84) acknowledges “when the meaning of the object is evident from the context”(ibid.: 82, examples 5a-d ) in the awareness that “verbs of motion and change” (ibid.: 82) are often used in both senses (6a-b, 7a-b, 8a-b, 9a-b, 10a-b,11).

(5a) He plays the violin. Transitive

(5b) He plays well. Intransitive

(5c) He smokes cigars. Transitive

(5d) She does not smoke. Intransitive

(6a) He moves a stone. Transitive

(6b) The stone moves. Intransitive

(7a) She changes the subject. Transitive (7b) The fashion changes. Intransitive

(8a) He turned the leaf. Transitive

(8b) The current turns. Intransitive

(9a) We begin the play. Transitive

(9b) The play begins at eight. Intransitive (10a) They end the discussion. Transitive (10b) The meeting ends at ten. Intransitive (11) The soldiers burned everything Transitive

that would burn. Intransitive

Verbs that are used intransitively do this by themselves or “through an inward impulse” (ibid.: 82) e.g. ‘The stone rolled down the hill.’ is different from ‘The stone was rolled down the hill.’ Jespersen considered many of these verbs as causatives (ibid.: 83), which means that the transitive use was regarded as the original and the intransitive use was regarded as derived, but for some verbs it was not clear which use was original (ibid.: 83). He also pointed at verb pairs like set/sit and lay/lie (ibid.: 83) that could fulfill this transitive/intransitive alternation (12a-b, 13a-b), but still, sit could also be used transitively, and set could be used in an intransitive sense (14a-b). Some transitive verbs can also be used as anticausative intransitives (ibid.: 84) to express a property of the subject by means of “well” (15a-b) or anything descriptive (16a-b). We refer to them topically as middle constructions. (12a) He sets the baby on the floor. Transitive

(12b) He sits on a bench in the park Intransitive (13a) He lay the baby on the mattress. Transitive

(13b) He lay in the grass. Intransitive

(14a) He sits the baby on the stool. Transitive

9 (15a) His plays won’t act and his poems won’t sell. Intransitive, intransitive

(15b) None of the babies photographed well. Intransitive (16a) This paper reads like a novel. Intransitive

(16b) These words read easily. Intransitive

4. Ambi-transitive verbs

Ambi-transitive verbs have one or more transitive senses and one or more intransitive senses. O’Grady (1980:58) distinguishes “alternating intransitives” and “derived intransitives”. The first type can also be used transitively to “denote events, processes and [self-originating] changes of state” independent of an intervening agent. This is what Jespersen (1933: 82) calls verbs of motion and change. With the second type the transitive sense seems more basic as these verbs express events that need a participating agent, which is missing because the participant in the subject position is not the agent but “an agentive actualizer”: e.g. (15a-b , 16a-b) above. Keyser and Roeper (1984, 1992) call this first type ergatives and the second type middles.

5. The passive voice

In secondary school, we turned active constructions into passive constructions and vice versa using a simple technique on the basis of one conversion formula: verbtense <> betense + verbpast_participle e.g.

(17a-c). We were told that we could drop the by-clause with the original subject because the object of the active voice becomes the new subject of the passive voice, replacing the old one, making the original subject optional or redundant as a result of the shift of focus. Of course there is more to it than this, but these were the basics.

(17a) I see a dog. <> A dog is seen (by me). (17b) I saw a dog. <> A dog was seen (by me). (17c) I have seen a dog. <> A dog has been seen (by me).

Jespersen (1933: 85-88) also describes the passive and observes that we use passive voice when the subject of the active voice is either unknown (18a), not easy to state (18b), uninteresting (18c) or irrelevant (18d), and so in a majority of these cases we will not mention it.

(18a) She was killed in a car accident. (18b) I was tempted to kill him. (18c) The doctor was sent for. (18d) My bike was stolen.

He links transitive active voice with intransitive passive voice and explains this as follows, with regard to examples (19a-b): “Jim is ‘governed by’ or, as it may also be termed ‘the object of’ the preposition

at. [This may …] be analyzed in another way: laughed at may be called a transitive verb-phrase

having Jim as its object.” Thus it is clear how this active sentence can turn into a passive (Jespersen 1933: 87).

Moreover, also clauses with a [transitive verb + object + preposition] can be turned into the passive: e.g. (20a-b).

(19a) Everybody laughed at Jim. Transitive, active (19b) Jim was laughed at by everybody. Intransitive, passive (20a) I take good care of her. Transitive, active (20b) She is taken good care of. Intransitive, passive

10 6. Valency and transitivity

Dixon & Aikhenvald (2000: 2) say that in every language there is a major clause type, consisting of a predicate and a variable number of arguments. In fact, two clause types are universal: the

intransitive and the transitive clause. They differ in valency, a notion from chemistry coined in 1897 as a linguistic metaphor by the logician Charles Sanders Peirce8, referring to the number of

arguments controlled by a predicate. I focus on predicates that are lexical verbs controlling 1, 2 or sometimes 3 arguments as in (21a-c).

# arguments aka:

(21a) The door opens. 1 monovalent, monadic, intransitive (21b) She opens the door. 2 divalent, dyadic, transitive

(21c) He gave her the doorknob. 3 trivalent, triadic, ditransitive

These arguments can be either core or non-core (22a-d) and verbs can be classified on the basis of the clause types they occur in (Dixon & Aikhenvald 2002: 4). They can be strictly intransitive verbs (e.g. arrive), strictly transitive verbs (e.g. like) or ambitransitive verbs in two varieties, namely S=A “agentive ambitransitives” (e.g. follow, win) or S=O “patientive ambitransitives” (e.g. open, melt) (ibid.: 6, Mithun 20009).

(22a) The door (S) opens. (S) core: subject of an intransitive verb (22b) She (A) opens the door (P). (A) core: agent of a transitive verb

(P) core: patient of a transitive verb (22c) He is sitting (in the park) PP. (PP) non-core: oblique, optional

Valency can reduce or increase. A causative conversion is a prototypical increase (25a->b) and according to Dixon and Aikhenvald, “the basic semantic effect of a causative derivation is to

introduce an additional participant, the causer, which naturally has the syntactic effect of adding an argument” (Dixon and Aikhenvald 2000: 16).

(25a) The car (S) stops. active voice, intransitive, monovalent (25b) He (A) stops the car (P). active voice, transitive, divalent

On the other hand, passive voice is a prototypical reduction (ibid.: 7) (23a->b). When (23b) (A) is removed from the core and becomes an oblique, the clause becomes intransitive, since there is only one core argument left, namely the original (P) that has become (S).

(23a) I (A) open the door (P). active voice, transitive, divalent (23b) The door (S) is opened (by me). passive voice, intransitive, monovalent

Next to this prototypical passive, English also has an agentless passive (ibid.: 7) where the A is not stated, and another “valency-reducing derivation where the S of the derived verb corresponds to the underlying O, […without a…] marker (or implication of…) the underlying A” (ibid.: 7). This is an anticausative (24c), the inverse of a causative (24d) . Notice (24c), in contrast to (24a-b), comes into this state without the involvement of an A, in other words by itself or spontaneously.

(24a) The download was started (by John). Prototypical passive, optional oblique

8 As retrieved from en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Sanders_Peirce on July 12 2020. 9 In Dixon & Aikhenvald 2000, p84-113

11 (24b) The download was started. Agentless passive (‘by someone’ implied)

(24c) The download started. Anticausative, no A stated or implied. (24d) John started the download. Causative, A stated.

This is how the passive behaves in English. Siewierska (1984:255) concludes a survey of different types of passives in different languages saying many “so-called passives do not have a single property in common”. In this paper, different passives appear cross-linguistically as translation equivalents for English active ergative clauses. In order to explain their appearance, I look into the formation and functions of active and passive voice in the languages of this research.

7. Transitivity and semantics

Each language has its classes of verbs. Whether, or to what extent, a verb is transitive is linked to its semantics. Hopper and Thompson (1980) thought up 10 parameters to set up a transitivity scale. They found that a syntactically transitive verb that scores somewhere near the middle of the scale often allows a valency-decreasing derivation to intransitive while a syntactically intransitive verb that scores in the middle section, often allows a valency-increasing derivation to transitive use, and so “the meaning of a subclass of verbs will often incline it towards occurring with a certain kind of valency-changing derivation” (Hopper and Thompson 1980: 20) – e.g. (26a-b).

Comment:

(26a) The noise annoyed me. This verb typically has a human O.

(26b) I was annoyed by the noise. => Preference of Passive construction in discourse, promotion of O to the surface subject S.

There are two major classes or categories of verbs that also have likely derivations. Here I start from Anglophile linguistics, focusing on examples in English.

Unaccusative10 verbs describe an event, that happens spontaneously to a patient (27b,c) or is

instigated by and agent (27a). If they are transitive, they probably also take passive (27a > 27c) and/or an anticausative derivation (27a > 27b). If they are intransitive (27b), they probably can undergo a causative derivation (27b > 27a) e.g. meanings such as ‘break’, ‘change’, ‘move’, ‘turn’, ‘burn’, ‘open’. These verbs are part of my study.

(27a) John opens the file. transitive, causative derivation from (26b) (27b) The file opens. intransitive, anticausative derivation from (26a) (27c) The file is opened (by John). passive derivation from (26a)

Unergative verbs11 denote action, either intransitive in general terms or transitive in function of a

specific patient (28a-b). e.g. meanings such as ‘eat’, ‘sweep’, ‘polish’, ‘play (at)’, ‘cry (over)’, ‘speak (to)’. These verbs are not part of this study.

(28a) John reads a newspaper. transitive, specific patient

(28b) John reads. intransitive, action in general terms

10Hopper and Thompson (1980: 20) prefer ‘S=O ambitransitives’, patient-preserving or P-lability as a name for

these alternating verbs.

11 Hopper and Thompson (1980: 20) prefer ‘S=A ambitransitives’ or agent-preserving or A-lability as a name for

12 I think this terminology is quite confusing, at least it was confusing to me at first. Initially it was clear, that unergative and unaccusative are classes or categories of verbs. Unergative verbs are verbs with animate agent-subjects expressing voluntary actions, events or activities (28a-b). Unaccusative verbs are verbs with non-agent subjects and these verbs express involuntary actions, events of activities, either affecting animate or non-animate subjects (27b-c).

In English, unaccusative verbs often appear in an active antiintransitive / active causative-transitive alternation e.g. (27b/a). They can just as well emerge in a passive causative incausative-transitive / active causative-transitive alternation e.g. (27c/a). (27b/a) is also called an ergative alternation. (27c/a) is an active/passive syntactic conversion but in this paper there can be more to it if there is no by-clause. Let us visualize this:

Table 2 - Unaccusative verbs and alternations

unaccusative or ‘ergative’ verbs

Alternation: clause 1 clause 2

basic alternation intransitive transitive

+ also anticausative causative

+ also active active

+ not passive passive

It is crucial to notice that “ergative” in this table refers to lexical ergativity in accusative languages (like the ones of this research) as opposed to morpho-syntactic ergativity in ergative languages. This could be a source of confusion since unaccusative and ergative verbs exist in both types of languages but the implementations are different. If functional linguists, e.g. Halliday, Davidse, Taverniers say “ergative” they think “lexical ergativity”, if formal linguistic typologists e.g. Dixon, Dryer say “ergative” they think “morpho-syntactic ergativity”.

8. Cross-linguistic comparison of default forms of verbs in active and passive voice

Often examples of ergative alternations in grammars, papers and dissertations are given in simple present, sometimes in simple past and seldom in present perfect. This does make sense considering that, according to the data12 of Ginseng English Online School on the basis of Krámský’s (1969: 118)

verb form frequency research, 57% of all verbs in the corpus of his analysis, composed of spoken language, were in the simple present, compared to only 19.7% in the simple past, 8.7% in the simple future and 6% in the present perfect, all other tenses appearing less than 1.5%. Additionally, in academic and technical texts as much as 62.8% were in the simple present. However, only taking simple present into consideration could lead to missing out on important aspects in the use of ergative strategies as the implementations of aspect and tense differ in each language and thus translation equivalents may differ not only in lexis, but also in grammar. Therefore I will start my research with both simple present and present perfect tenses in English datasets and add other tenses and aspects in my comparison when they emerge in the translation in the other languages. To anticipate possible consequences, I continue now with a brief look at the verbs open and begin used in active agentive, active intransitive and passive forms and corresponding adjectival/adverbial derivations in all five languages.

13 Table 3 displays 3rd person singular translation equivalents for open and begin, comparing agentive

(incomplete13) clauses consisting of subject and verb in simple present, simple past and present

perfect tenses.

Table 3 - Comparison of agentive S + V

English German French Dutch Danish

3rd person sing. he/she er /sie il/elle hij/zij han/hun

simple present opens begins öffnet beginnt ouvre commence opent begint åbner begynder

simple past opened began öffnete begann a ouvert a commencé opende begon åbnede begyndte

present perfect has opened has begun hat geöffnet hat begonnen a ouvert a commencé heeft geopend is begonnen har åbnet er begyndt

French apparently prefers a perfect tense as an equivalent for English simple past since this tense is more frequently used in translations according to Google Translate. Cross-linguistically two different auxiliaries are used in the present perfect , namely equivalents of ‘have’ and equivalents of ‘be’. I deal with this in my research.

Table 4 compares intransitive clauses with ‘the door’ and ‘the process’ as mediums being chosen because they are, according to the collocate option of Sketch Engine as applied to the enTenTen15 corpus, among the most frequently used subject-collocates, the former with open, the latter with

begin.

Table 4 - Comparison of intransitive S + V

English German French Dutch Danish

3rd person sing. the door the process die Tür der Prozess la porte le processus de deur het proces døren processen

simple present opens begins geht auf beginnt s’ouvre commence gaat open begint åbnes begynder

simple past opened began öffnete sich begann s’ouvrit a commencé ging open begon gik op begyndte

present perfect has opened has begun

hat sich geöffnet hat begonnen s’est ouverte a commencé is opengegaan is begonnen er åbnet er begyndt

More strategies can be observed in the intransitives: use of reflexive clitics in French and German, periphrastic verbs in German, Dutch and Danish, labile verbs in all languages, Danish -s passive. In Table 5 the formation of passive voice is compared cross-linguistically using the same

subject/medium + verb combination as in table 3 in the same tenses. The default translations using

MT show quite some variation in the use of passive auxiliaries, yet all passives are built the same way, namely passive auxiliary in appropriate tense + past participle, with the exception of Danish

s-passive in simple present s-passive that can appear as an alternative for the more general be + past participle construction.

14

Table 5 - Comparison of passive voice S + V

English German French Dutch Danish

3rd person sing. the door the process die Tür der Prozess la porte le processus de deur het proces døren processen simple present is opened is begun wird geöffnet wird gestartet est ouverte est commencé wordt geopend is begonnen åbnes er startet

simple past was opened was begun wurde geöffnet wurde begonnen a été ouvert a commencé ging open was begonnen blev åbnet blev startet present perfect

has been opened has been begun

wurde geöffnet wurde begonnen a été ouvert a commencé is geopend is begonnen er åbnet er startet

Ergative readings are possible as pointed out by Abraham (2000, 2003). If no agent is expressed nor implied, passives can be read as active tense, especially if the [auxiliary be + past

participle]-implementation is the same in both voices. This is especially the case with verbs with reflexive force (Curme 1931) and verbs that have “inclinees”14 as their subject (Davidse 2011).

Additionally [be + adjective/adverb] can also identify as an alternative ergative strategy in all languages. Such intransitives express a resultative state. Table 6 offers an example of this use, plus an example of an [Adj + N] construction, which also refers to the same state, but now expressed by an adjective in a noun phrase configuration.

Table 6 - Comparison of be + adjective / adjective + N

English German French Dutch Danish

3rd person sing. the door

the war die Tür der Krieg la porte la guerre de deur de oorlog døren krigen

simple present is open is over ist offen ist vorbei est ouverte est finie is open is voorbij er åben er forbi

Adj + N een open deur eine offene Tür une porte ouverte een open deur en åben dør

Dixon & Aikhenvald (2000: 19) plea to first observe semantics and syntactic differences and relations in a context, as used, in order to see how they “interrelate and function” and only after that try to formulate how these contrasts are realized. This approach will be part of the final part of my methodology, where I go back to the verbs in the datasets in order to observe their actual functioning and to further examine their possibilities and restrictions.

9. The role of aspect

Not discussed so far is the role of aspect, which cannot be underestimated as each tense of each lexical verb, either referring to past, present or future time, also includes an element of aspect. Aspect refers to the internal temporal structure of states, events and processes as expressed by lexical verbs, verbal phrases or constructions and as such distinguishes the way we look at them. (Comrie 1976:3ff, after Holt 1943:6; Bybee 2003:157). As commonly known, each language has its own means of coding aspect, which have been researched, analyzed and subclassified by many linguists. Because an in-depth analysis of aspect or tense is not the focus of this research, I treat this in a simple, pragmatic and comparative way, in order to explain the initial choices of tense and aspect made in this research.

14 “Inclinees” refers to a semantic role in certain types of verbs that makes them ergative candidates. (Davidse

15 In the next paragraph, I introduce the following abbreviations related to aspect: (S) for single block of time, (C) for continuous aspect, (HR) for habitual or repeated actions, (CP) for completed, perfective situations, (P) for continuous actions over a period of time. Additionally I use the following

abbreviations related to tense: (PR) for present, (PA) for past, (E) for eternal, timeless. The arrow <- indicates precedence and -> refers to result.

English distinguishes four aspects15: simple, progressive, perfect, and perfect progressive, each of

them expressing an aspect of duration or flow of time of a state, event or process that takes place in a single block of time (S), continuously (C) or repeatedly (HR) (ibid. 11).

While the simple aspect describes facts or a general action, one that is neither continuous nor completed (CP), it is usually used to describe something that takes place habitually (HR). As opposed to the simple form, the progressive form expresses continuous actions that happen over a period of time (P) and almost always involves the auxiliary be followed by the present participle of the lexical verb. As to be expected, a perfect progressive form is a combination of the perfect and progressive aspects. Perfect progressive refers to the “completed portion of an ongoing action”(ibid. 11) (CP) and

is built by joining a perfective form of be (have been) with a present participle.

The following table classifies and exemplifies tense and aspect in the present and past tenses.

Table 7 – Tense and aspect, examples and main T(ense)- and A(spect)-Use

Example16 Tense Main T-Use Aspect Main A-Use

I wash the car. present (PR) and/or (E) simple (HR) or (S)

I am washing the car. (PR) progressive (C)

I have washed the car (PA) -> (PR) perfect (CP)

I have been washing the car. (PA) -> (PR) perfect progressive (C)(P)

I washed the car. past (PA) simple (S)

I was washing the car. (PA) progressive (C)

I had washed the car. (PA2)<- (PA1) perfect (CP)

I had been washing the car. (PA2)<- (PA1) perfect progressive (C)(P)(CP)

Highlighted: initial choice of tense and aspect in the English source data of this research.

10. Ergative, middle and passive constructions

All three have been mentioned in the previous paragraphs. What do ergative, middle and passive constructions have in common? What makes them different?

First of all, the subject in all three is not an agent. In the passive construction, the transitive agent may be retained, but this is not the case in the other constructions: compare (29a.1), (29b.1) and (29c.1). In a middle construction, a property or a characteristic of the verb is expressed, the construction is intransitive and does not have a transitive counterpart: compare (29b) and (29b.2). In the ergative construction, a transitive/intransitive alternation is possible, and the non-agentive subject of the intransitive clause can be moved to the object position in the transitive counterpart: compare (29c) and (29c.2).

15 As retrieved from https://www.lawlessenglish.com/learn-english/grammar/tense-aspect/ on July 11 2020 16 As retrieved from https://www.lawlessenglish.com/learn-english/grammar/tense-aspect/ on July 11 2020

16 1. by clause: agent

2. alternative clause

(29a) The man was eaten. 1. The man was eaten by a crocodile. passive 2. The crocodile ate the man. active (29b) The car drives easily. 1. *The car drives easily by the man. middle

2. *The man drives easily the car. no transitive counterpart (29c) The cake burned. 1. *The cake burned by the cook. ergative

2. The cook burned the cake. transitive counterpart Yang (1994: 77-78) points out there is also a syntactic difference concerning prepositional objects. A prepositional object in an active construction (30a) can become the subject in the passive

counterpart (30b), with the original agent retained, providing there is no direct object (30c). In middle constructions there is no such restriction. The original prepositional subject can become subject and the direct object can be retained (30d).

(30a) John has cut with the knife. active

(30b) The knife has been cut with by John. passive (30c) *The knife has been cut bread with by John passive

(30d) This knife cuts bread easily. middle

Yang (1994: 77-78) also points at 4 semantic differences between these 3 constructions:

1. Passive constructions focus on the active object but the relationship between the participants and the verb does not change whereas ergative and middle constructions do change this relationship (31a-c). Properly in (31a) still refers to the unmentioned agent and not the current subject. In (31b) and (31c) fast enough and easily refer to properties of the theme subject. Middles and passives resemble each other as in both cases there is an agent, either stated or implied while in ergative intransitives there is no agent at all.

(31a) The floor wasn’t swept properly. passive

(31b) The floor didn’t dry fast enough. ergative

(31c) This floor doesn’t sweep easily. middle

2. Ergative constructions generally can be paraphrased causatively and middles cannot (32a-b). In (32b) opens easily is a property of the door. It is not caused by John.

(32a) If the door opens, that’s because John opens it: John causes the door to open.

(32b) If this door opens easily, that’s because *John opens it easily: *John causes the door to open easily.

3. Some ergative constructions cannot be paraphrased causatively as they do not have a causer. They do it “all by themselves” (33). Keyser and Roeper (1984: 405) argue “all by itself” means “totally without external aid” and that would qualify as ergative or without agent.

17 4. A final difference between ergatives and middles is the use of adverbials: they are mandatory in middles and optional in ergatives (34a-d). Middles always characterize the activity while ergatives primarily report events and can optionally include how the event is performed.

(34a) The floor dried (quickly). ergative, adverb optional (34b) The door opens (easily). ergative, adverb optional (34c) Wooden floors sweep easily. middle, adverb required (34d) This type of door opens easily. middle, adverb required 11. Ergativity

According to Dixon (1994: 3) the term ergativity has been in use “at least since the late 1920s”. Ramer (1994: 1-2) traces the term back to notes of the anthropological scholars Haddon and Ray in 1893. They use it for a locative case as spoken in languages in British New Guinea (now a part of the Independent State of Papua New Guinea). It is first used in its modern sense in (or possibly) before 1902 by a “Pater Schmidt” referring to Haddon and Ray (1983), but according to Butt (2012: 198) Schmidt misinterpreted the term and assigned it to the agentive nominative subject case, thus coining the word. Trombetti (190317) used it like that too and attributed the term to Pater Schmidt.

Ultimately, Ray (190718) accepted this use and dropped the term.

The concept of ergativity has been defined and discussed by many authors. Anderson (1968), Lyons (1968) and Fillmore (1968) all used the term for the link between the subject of an intransitive sentence and the object of a transitive sentence. Plank (1979: 4) summarizes the basic idea, saying “ergative alignment identifies intransitive subjects and transitive direct objects, as opposed to transitive subjects”. Dixon (1979, 1994: 3) mainly deals with morphological ergativity in ergative-absolutive languages. In these languages the subject of the transitive clause (=A) appears in the marked ergative case and both the subject of the intransitive clause (=S) and the object of the transitive clause (=0) occur in the unmarked absolutive.

All the languages I work with in this paper are accusative languages. Ergativity in this context is different since these languages can show ergative syntax without ergative morphology. This is the case for English, German, French, Dutch and Danish and the initial examples in the introduction already showed this. This is a broader, lexical-semantic interpretation of the concept of ergativity. Dixon (1994: 20), for fear of a degradation of the term, argues against the use of the term ergativity for this purpose as thus every language has a causative construction.

This did not keep authors in different frameworks to use the term in this broader, lexical-semantic sense, as a shorter way to refer to this “lexical-semantic ergativity”. Besides, verbs allowing for an “ergative alternation” are termed “ergative verbs” while in English these verbs are often called “labile verbs” (Davidse 1992, Haspelmath 1993, Dixon 1994, McMillion 2006, McGregor 2009). This is more specific though, because labile verbs do not change their form in the ergative alternation as the same verb is used in both clauses. Others have suggested other names and it is important to include this here too, in order to avoid ambiguities and misunderstandings. There is a link between the presence or absence of ergativity, transitivity and causativity. In a previous section I elaborated on this. Now I will put things together in a lexical-semantic context.

17 Trombetti, Alfredo 1902−1903 Delle relazioni delle lingue caucasiche con le lingue camitosemitiche e con altri

gruppi. Giornale della Società Asiatica Italiana. Firenze.

18 Ray, Sidney. 1907. Reports of the Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to Terres Straits. Vol. III:Linguistics,

18 Haspelmath (1993: 90) studies verb pairs cross-linguistically and semantically in alternating clauses. The verbs in his selection are clearly “change of state” verbs. Each of his 31 verb pairs are analyzed in alternating clauses in 21 languages. One clause is always transitive with a verb with a causative meaning and a causing agent, the other clause is intransitive with the situation occurring

spontaneously and without causing agent. He names this alternation “inchoative/causative”. The inchoative clause and the passive of the causative clause have about the same meaning, but in the first no agent is involved, while in the second, the agent is at least implied (or could be mentioned in a by-clause).

Haspelmath (1993) discusses the typological side of the fore mentioned alternation and distinguishes three main types of inchoative/causative alternations or oppositions: causative, anticausative and non-directed. The non-directed alternations are further subdivided into labile, equipollent and suppletive (Haspelmath 1993: 91-92). The next table, inspired by his definitions, visualizes the characteristics and the differences:

Table 8 – Verbs in clause alternations according to Haspelmath (1993: 91-92)

clause alternation

verb 1 verb 2 means of derivation

causative inchoative/anticausative is basic causative derived

affix, auxiliary, stem modification anticausative causative is basic anticausative derived

equipollent stem + derivation 1 stem + derivation 2 different affix, auxiliary, stem

suppletive root 1 root 2 different root

labile same verb none

When causatively alternating verbs are used intransitively, they are referred to as anti-causatives or inchoatives because the intransitive variant describes a situation in which

the theme participant (for instance ‘the door’ in the door opened) undergoes a change of state, becoming, for example, “opened” (Schäfer 2009: 642) .

Summarized, the ergative or anti-causative/causative alternation is all about specific

intransitive/transitive alternating clauses where the subject of the intransitive clause can become the object of a transitive clause and vice versa, both clauses describing the same event with different syntax but in the same semantic context.

The main difference is that the transitive clause mentions the agent or force that instigates the event or action that has an effect on the object, referred to as “medium” in Systemic Functional Linguistics. In the intransitive clause this subject/medium is undergoer or patient (see 35a) who executes the event seemingly spontaneously without mention or implication of an agent/instigator (35b). A passive construction can be an alternative for this intransitive active clause, but it differs in that it implies an agent, understood, or mentioned in an optional phrase, by default (35c). This option is not available in the intransitive active variant (35d).

(35a) He opens the door. (35b) The door opens.

(35c) The door is opened (by him). (35d) *The door opens by him.