CUSTOMER ENGAGEMENT IN THE

WORLD OF SMART SERVICE

SYSTEMS:

THE ROLE OF PRIVACY, SECURITY, INTRUSIVENESS AND TRUST

Word count: 13 641

Tine Van der Perre

Student number : 01605548

Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Katrien Verleye Co-supervisor: Drs. Bieke Henkens

Master’s Dissertation submitted to obtain the degree of:

Master of Science in Business Economics: Corporate Finance

CONFIDENTIALITY AGREEMENT

PERMISSION

I declare that the content of this Master’s Dissertation may be consulted and/or reproduced, provided that the source is referenced.

Student’s name: Tine Van der Perre

ABSTRACT

Purpose - Smart products and smart services are globally gaining attention, thanks to their vast

potential to change the competitive landscape. To fully grasp these new opportunities companies must stimulate customer engagement, given that it has essential benefits through which the company can be one step ahead of its competitors. However, creating a strong customer engagement basis will be challenging because concerns and risks accompany smart products and services. Previous literature shows some indications that trust-building could be a possible tool for companies to reduce these negative side effects of smartness. However, there is no empirical evidence of this effect in the existing smart product and service literature. Therefore, the objective of this research is to investigate how intrusiveness, security, privacy, and trust will impact the smartness – customer engagement relationship.

Design/methodology/approach - Drawing on the psychological ownership theory, the

information boundary theory and the personalisation privacy paradox we developed a conceptual framework, which was tested by conducting a scenario-based survey in Belgium. Next, we provided a confirmatory factor analysis followed by a verification of the realism and successfulness of respectively our scenarios and manipulations. Last, we analysed our data using the Hayes process analysis.

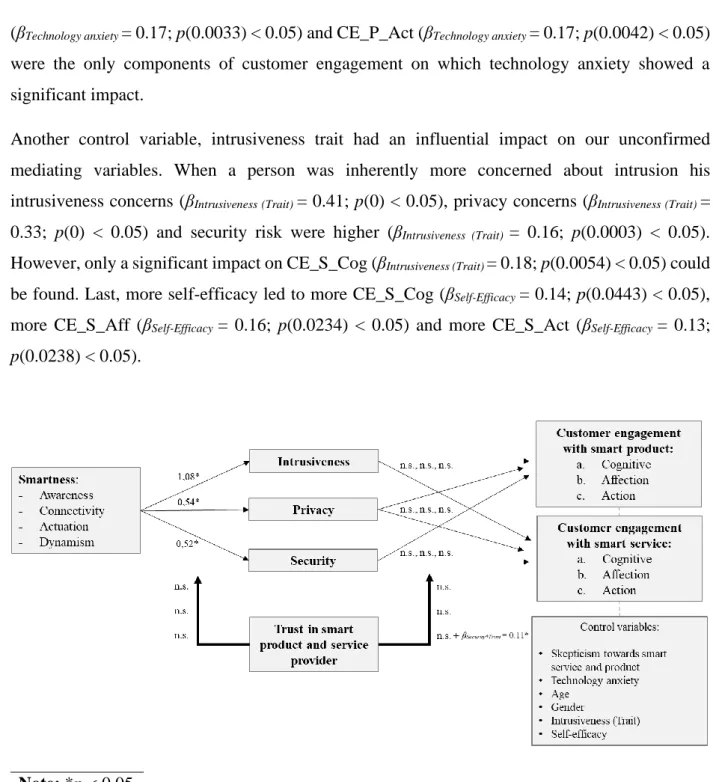

Findings – Privacy concerns, intrusiveness concerns and security risks were positively influenced

by smartness, but did not impact customer engagement. They are thus partial mediators. Surprisingly, trust qualified as mediator instead of the predicted moderator effect. As a result, only trust could explain the positive relationship between smartness and customer engagement. Last, age and scepticism seemed to be the most relevant external factors. Younger people show more engagement compared to older people. Meanwhile, fewer scepticism results in more customer engagement.

Value - Managers must find a balance between smartness, and accepted intrusion and privacy to

make the customers feel at ease while using their products and services. Further, our research shows some indications that trust-building will play an essential role in smart service systems. By establishing a bond of trust, managers can stimulate customer engagement, which would strengthen their competitive position.

FOREWORD

This master dissertation is written in the context of my education, corporate finance at the university of Ghent. I could not have established this project on my own, therefore I would like to thank all the people who helped me during this assignment.

First, I would like to express my appreciation to both my supervisors Prof. Dr. Verleye and Drs. Henkens for their support and guidance during this assignment. Thanks to their feedback and positive contributions I was able to successfully finish this master dissertation.

Second, I would like to thank all my friends and family, who encouraged me during this period. Their feedback and patience resulted in additional value.

Further, I am especially grateful for all the respondents, who took their time to complete the survey. Last, this master dissertation was written during the outbreak of Covid-19. However, this did not impact the results of my thesis. Both my survey and the feedback conversations with my supervisors were done online, respecting the social distancing rules.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ... II FOREWORD ... III TABLE OF CONTENTS ... IV LIST OF USED ABBREVIATIONS ... V LIST OF TABLES ... VI LIST OF FIGURES ... VI

1. INTRODUCTION ... 1

2. LITERATURE REVIEW ... 4

2.1. SMART PRODUCTS AND SERVICES... 4

2.2. CUSTOMER ENGAGEMENT... 7

3. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK ... 9

3.1. THE MEDIATING ROLE OF PERCEIVED INTRUSIVENESS ... 9

3.2. PRIVACY CONCERNS AS A MEDIATOR BETWEEN SMARTNESS AND CUSTOMER ENGAGEMENT ... 12

3.3. SECURITY RISK AS AN EXPLANATORY VARIABLE ... 14

3.4. TRUST IN THE SERVICE PROVIDER AS A MODERATOR ... 16

3.5. CONTROL VARIABLES ... 19

4. METHODOLOGY AND RESEARCH DESIGN ...21

4.1. CONTEXT AND SCENARIOS ... 21

4.2. MEASUREMENT ... 22

4.3. DATA COLLECTION AND SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICS ... 23

4.4. QUALITY OF THE CONSTRUCTS ... 24

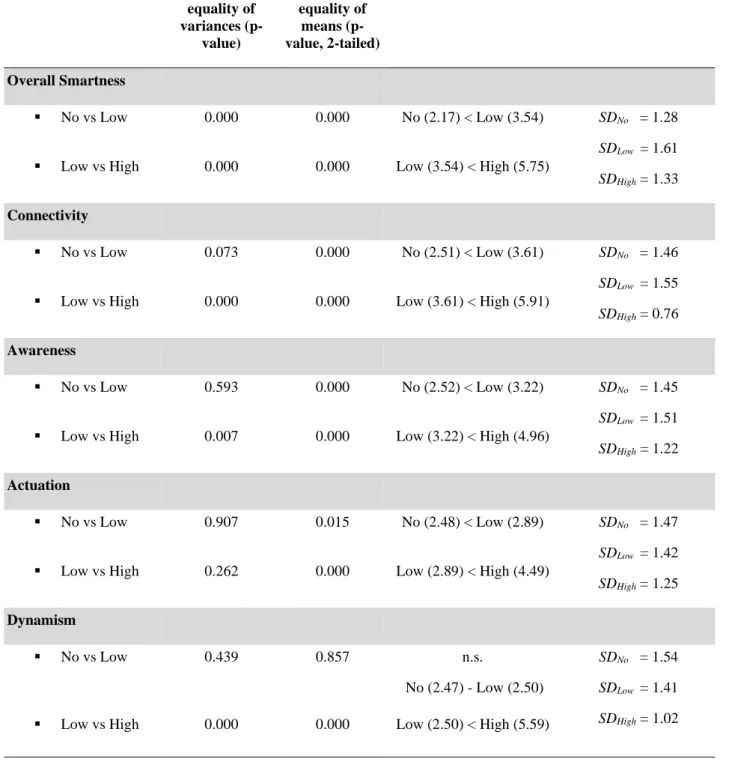

4.5. SCENARIO REALISM AND MANIPULATION CHECK ... 27

4.6. RESEARCH MODEL: HYPOTHESIS TESTING ... 29

5. DISCUSSION ...33

5.1. THEORETICAL CONTRIBUTION ... 33

5.2. MANAGERIAL CONTRIBUTIONS ... 36

5.3. LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH ... 36

6. CONCLUSION ...38 REFERENCES ... VII APPENDICES ... XIII APPENDIX A: SCENARIOS ... XIII APPENDIX B: SURVEY STRUCTURE ... XIV APPENDIX C: SCALES AND TRANSLATION ... XXVI APPENDIX D: FACTOR ANALYSIS ...XXXII

LIST OF USED ABBREVIATIONS

CE Customer engagement

CE_P_Cog The cognitive aspect of customer engagement with smart product CE_P_Aff The affection aspect of customer engagement with smart product CE_P_Act The action aspect of customer engagement with smart product CE_S_Cog The cognitive aspect of customer engagement with smart service CE_S_Aff The affection aspect of customer engagement with smart service CE_S_Act The action aspect of customer engagement with smart service IBT Information boundary theory

IoT Internet of things KMO Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin PO Psychological ownership VIF Variance Inflation Factor

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Literature definitions of smart services ... 4

Table 2: Overview of smartness literature ... 6

Table 3: Dimension of engagement by Hollebeek et al. (2014, p.6) ... 8

Table 4: Descriptive statistics... 23

Table 5: Correlation Matrix ... 26

Table 6: Manipulation outcome ... 28

Table 7: Regression coefficients ... 32

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Conceptual framework ... 91. INTRODUCTION

In recent years a third technological wave has emerged. This has led to embedded sensors in, and more connectivity of everyday products. This connectivity is mostly associated with the Internet of Things, which is a term for several objects or products that are all connected to the internet, a place where they can exchange data with each other (Porter & Heppelmann, 2014). However, also new opportunities to build products with incorporated smartness have gained attention (Rijsdijk, Hultink, & Diamantopoulos, 2007). Global smart home revenues are forecasted to be 141.2 billion US dollars (Statista, 2020a). In most countries the market is evolving past the early-adopter stage, which shows the success of the smart home market (Statista, 2020a). Smartness reflects the intelligence of a product and is measured by four essential smartness characteristics: awareness, connectivity, actuation and dynamism (Henkens, Verleye, & Larivière, 2020). These characteristics allow us to differentiate smart products and services from traditional offerings. Smart services are services delivered through smart products, which are everyday products that have been enhanced through smart technology (e.g. software, sensors). The smart services are found in various sectors such as hospitality, tourism, healthcare, entertainment and public sectors (Kabadayi, Ali, Choi, Joosten, & Lu, 2019; Kowalczuk, 2018; Lytras & Visvizi, 2018; Wiegard & Breitner, 2019; Yang, Yu, Zo, & Choi, 2016; Yang, Lee, & Zo, 2017). According to the forecasts of Statista (2020b), global smart home devices sales will grow to 1.940 million units by 2023, which makes it an important market.

Smartness creates new possibilities for products and their services (Beverungen, Müller, Matzner, Mendling, & vom Brocke, 2019; Wünderlich, Wangenheim, & Bitner, 2013). As a result, it is reshaping the competitive landscape in specific industries (Porter & Heppelmann, 2014). Research has primely focused on adoption, initial resistance or acceptance, which is situated ex-ante purchase (Chouk & Mani, 2019; Hubert et al., 2019; Mani & Chouk, 2017; Yang et al., 2017; Yuen, Wang, Ma, & Wong, 2019). However, companies whose primary goal is getting the customers to buy their products will not succeed in these new competitive markets. Between one type of smart offering, the core product characteristics are somewhat homogeneous, creating indifferent customers and more intense competition. To take advantage and profit from the third technological wave companies must develop smart products and services that stimulate engagement, which in turn result in various positive outcomes such as commitment, emotional connection with the brand and loyalty (Brodie, Hollebeek, Jurić, & Ilić, 2011). In this way, positively engaged customers will become promotors for the company’s product, which

strengthens the competitive position (Vivek, Beatty, & Morgan, 2012). Further, this customer engagement will positively influence firm performance, which creates value for the company (Kumar & Pansari, 2016).

However, creating this positive customer relationship will be challenging, because smart products and services also have some disadvantages. In the era of big data, all these smart offerings could gather and exploit a lot of information about the customer, resulting in privacy and security concerns (Schroeck, Shockley, Smart, Romero-Morales, & Tufano, 2012). Previous studies acknowledge that privacy and security will become a challenge for smart products and services (Kowalczuk, 2018; Wuenderlich et al., 2015). Lytras and Visvizi (2018) their study on smart cities showed that 70% of the concerns were related to security and protection (45%), and data concerns (25%). Another study carried out by Accenture (2016) found that 47% of the customers indicated, having security and privacy concerns about Internet of Things devices. Next, almost 18% ended their usage due to these concerns. Second, smart products have sensors, which can detect different types of input such as audio, location and video (Hoffman & Novak, 2018). Prior research indicated that some of these sensors are perceived intruding (Balta-Ozkan, Davidson, Bicket, & Whitmarsh, 2013; Townsend, Knoefel, & Goubran, 2011). Further, intrusion itself impacts the resistance to smart products (Mani & Chouk, 2017). Therefore, smart service providers need to understand the source of these intrusive feelings.

In these concerns and risks, trust can play an important moderating role. Smartness creates uncertainties, which do not stop after adoption, but stay present in the stage afterwards (Accenture, 2016; Lytras & Visvizi, 2018). Pavlou (2003) argues that trust can take away some of this uncertainty by reducing the behaviour uncertainty related to the service provider. This vital role of trust is shown by AlHogail (2018), who remarked that it affects the behaviour intention of a customer to adopt. Establishing a bond of trust between the customer and the smart product and service can result in a smoother implementation of smart offerings, creating enormous potential for the market.

It is unknow how intrusiveness, security, privacy, and trust will impact the smartness- engagement relationship. Drawing on the psychological ownership theory, the information boundary theory and the personalisation privacy paradox we will fill in this gap by providing an answer to the following research question: How is the relationship between smartness and customer engagement affected by intrusiveness, privacy, security, and trust? We will examine this relation by conducting a scenario-based survey in Belgium in the context of a digital assistant and its service.

By addressing this research question, this inquiry contributes to the existing literature on smart products and services in four ways. First, in the majority of the literature, the smartness of intelligent products and services is described as a positive evolution (Porter & Heppelmann, 2014; Rijsdijk et al., 2007). However, with our research, we adopt a more holistic perspective and also investigate possible drawbacks of smartness increases: the emerging and relevant concerns of privacy, intrusiveness and security risk. As such, moving the smart product and service literature beyond a dominating one-sided perspectives of the advantages of ever smarter products and services. Second, by adding the well-know, but impactful concept of trust, we try to provide a possible solution to moderate the potential negative consequences of smartness on engagement. By applying the concept of trust in a smart service context, we contribute to the existing literature of trust-building. Third, by studying a long-term engagement perspective, we fill in the academic gap that exists after the adoption of smart products and services. This allows us to progress on the literature beyond adoption. Finally, we examine the dynamic between the smart service provider, the intelligent product and the customer. This multi-actor perspective allows us to gain insights in the world of smart service systems. From a managerial perspective, this research will indicate the role of trust-building and provide managers with useful knowledge on how to design products with the right type of smartness to conquer this relatively new market and stimulate customer engagement

The remaining part of this master dissertation is divided into five sections. First, in the literature review, we briefly discuss the concepts of smart products and services as well as customer engagement. Further, we provide an overview of the existing research in a smart product and service context. In our second section, we develop a conceptual framework with corresponding hypotheses. In the third section, we outline our methodology and report our results. In the following section, we will discuss our main findings. We divided the major section in three subsections: theoretical contributions, managerial contributions, and limitations and future research. In the last and final section, we summarise our most important conclusions.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. SMART PRODUCTS AND SERVICES

Smart products, or also called intelligent products, are physical objects that enable various smart services (Beverungen et al., 2019). A smartwatch, for example, makes it possible to connect and control your smartphone, allowing you to receive messages and text other people (Yang et al., 2016). Other examples of smart products can be found in Table 2 of this paper.

Further, smart services use smart products as “boundary objects that integrate resources and activities of the involved actors for mutual benefit” (Beverungen et al., 2019, p.12). Based on the various definitions found in the literature (see Table 1), we defined smart services as services that are delivered through smart products, which means that they use the input provided by the involved actors and collected by the smart product to deliver their service.

For example, the smart meter is the boundary object for smart energy suppliers and governments. While customers get feedback on their energy usages, smart energy suppliers can optimise their tariffs. The government, on the other hand, gains insights into the electricity usage of its citizens, which will allow them to create better policies (Buchanan, Banks, Preston, & Russo, 2016).

Table 1: Literature definitions of smart services

Author(s) Definition

Beverungen et al. (2019, p.12)

Smart service is the application of specialized competences, through deeds, processes, and performances that are enabled by smart products.

Smart service systems are service systems in which smart products are boundary-objects that integrate resources and activities of the involved actors for mutual benefit Anke (2019, p.21) Smart services are therefore service systems, which enable value co-creation between

service provider and beneficiary through the joint performance of service activities Kabadayi et al. (2019,

p.330)

Smart services are personalized and pro-active services that are enabled by the integrated technology and intelligent use of data that can anticipate and fulfill customer needs at specific times and/or locations based on changing customer feedback and circumstances.

Mani and Chouk (2018, p.781)

Smart services are those services that use IoT devices to provide services to customers.

A smart offering, which consists of a smart service and a smart product, uses integrated technology to collect and analyse data to create (often personalised) experiences (Kabadayi et al., 2019; Porter & Heppelmann, 2014). Based on their characteristics and connection with IoT, smart products can distinguish themselves from traditional products. Therefore, the delivered service is more innovative (Mani & Chouk, 2018).

According to Rijsdijk et al. (2007), there can be six characteristics of smart products: autonomy, ability to learn, reactivity, ability to cooperate, humanlike interaction and personality. However, following Rijsdijk et al. (2007), it is not required for an intelligent product to meet all of the six dimensions.

On the other hand, in our study, we follow the approach of Henkens et al. (2020), who reduced the dimensions to four core smartness characteristics: awareness, connectivity, actuation and dynamism. In contrast to Rijsdijk et al. (2007), it is a necessity for a smart product to meet all of the proposed smartness characteristics. We will explain the definitions of Henkens et al. (2020) by using the example of the digital assistant. Through the sensors embedded in the smart product, the digital assistant can gather information about itself and its environment (awareness). Further, thanks to the implementation of IoT, the digital assistant can communicate with the customer, the service provider and various devices (connectivity) (Hoffman & Novak, 2018). The third characteristic, namely actuation, enables via a computational process the possibility for the device to act and decide without the intervention of the customer. This means that the digital assistant can search for answers to the proposed questions without the intervention of a human. Alternatively, it could also choose a restaurant and make an appointment for the user. Last, a digital assistant continuously interacts with his actors. The product analyses the collected data to learn and adapt, resulting in more accurate and personalised search results (dynamism). Given that the digital assistant meets all the smartness characteristics, it is considered smart. However, not all smart offerings are equally smart, since the four smartness characteristics can vary along a continuum from low to high (Henkens et al., 2020). Further the four characteristics are inherently linked to each other. As an example, more awareness enables the possibility for more information gathering and thus more dynamism. Due to the possible variation of the different parameters, different levels of smartness emerge, which in turn create corresponding levels of consequences (e.g. intrusion, trust, security risk).

Table 2: Overview of smartness literature

Author(s) Goal Context Method Theory

Hubert et al. (2019) Develop a comprehensive adoption model Smart home technology Quantitative survey Scenario-based approach Technology acceptance model (TAM)

Innovation diffusion theory (IDT)

Perceived risk theory (PRT) Yang et al.

(2017)

Develop a comprehensive research model for the user’s acceptance of smart home services Smart home services in Korea Quantitative survey Scenario-based approach

An extension of the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) Perceived behaviour control (PBC) Technology acceptance model (TAM) Yuen et al. (2019) Determine the factors which influence a user intention to use smart lockers Smart lockers in China

Quantitative survey Resource matching theory Perceived value theory Transactions cost economics theory

Mani & Chouk (2017)

Examine the factors that influence customer resistance to smart products Smartwatch in France Qualitative survey Quantitative survey

The theory of reasoned action

Theoretical framework of Ram and Sheth (1989) Mani & Chouk

(2018) Examine to what extent the psychological, functional, and individual barriers impact consumer resistance to smart services Smart bank services in France Quantitative survey Scenario-based approach

Extension of the theoretical framework of Ram and Sheth (1989)

Chouk & Mani (2019)

Examine factors which reduce and promote resistance to smart services

Smart bank services in France

Quantitative survey Theoretical framework of Ram and Sheth (1989)

Rijsdijk et al. (2007) Developing procedure to measure the concept of intelligent products and verify its impact on satisfaction Various intelligent products (e.g. personal digital assistants) in The Netherlands Analysing interview transcripts Literature review on the abilities of intelligent products Quantitative survey N.A. Kabadayi et al. (2019) Provide a definition and comprehensive conceptualization of the smart service experience Smart service experience in hospitality and tourism services

Conceptual paper N.A.

Balta-Ozkan et al. (2013) Explore social barriers to the adoption of smart homes Smart homes in the United Kingdom Qualitative research (workshops, interviews) N.A.

2.2. CUSTOMER ENGAGEMENT

Customer engagement (CE) is a psychological state that emerges if a “customer co-creates experiences with a focal object in focal service relationships” (Brodie et al., 2011, p.260). It can vary each time the context changes. Therefore it is a dynamic and iterative process. Further, CE is a central and multidimensional (e.g. cognitive, emotional and behavioural) concept in the nomological network, with various antecedents and/or consequences (e.g. involvement, loyalty, trust). Last, customer engagement is a tool that can help to govern the service relationships (Brodie et al., 2011).

Although we follow the definition of Brodie et al. (2011), who described customer engagement as a positive and multidimensional concept, Vivek, Beatty, Dalela and Morgan (2014) remark that not every study shares this vision of a positive and multidimensional concept.

First, Do, Rahman and Robinson (2019) provided research on negative customer engagement, which can emerge from negative experiences with the service provider or product, and ultimately result in disengagement. With our study, we will try to give managerial insight to prevent and/or reduce this destructive form of engagement.

Second, not every study is based on multiple dimensions. Although, the multidimensional perspective was mainly used, over 40% defined engagement as a unidimensional concept (e.g. behaviour, emotional or cognitive) (Brodie et al., 2011). One of them is van Doorn et al. (2010), who refers to customer engagement as a unidimensional concept, based on the customer’s behaviour. However, in line with Brodie et al. (2011), we argue that a unidimensional concept cannot capture the full capacity of engagement. Therefore, we will follow a multidimensional approach.

The multidimensional concept exists out of three dimensions of customer engagement, which are provided by Hollebeek, Glynn and Brodie (2014). The cognitive processing explains the reasoning behind the interaction. It reflects how the customer is stimulated to think about the smart product or service. Further, affection reflects the emotional part (e.g. positive or negative feelings). Last, the activation component indicates the invested energy time and effort of the customer in the smart product or service, which is a reflection of the customer’s behaviour.

Table 3: Dimension of engagement by Hollebeek et al. (2014, p.6) Dimensions of

engagement

Definition

Cognitive processing A consumer's level of brand-related thought processing and elaboration in a particular consumer/brand interaction.

Affection A consumer's degree of positive brand-related affect in a particular consumer/brand interaction.

Activation A consumer's level of energy, effort and time spent on a brand in a particular consumer/brand interaction.

Customer engagement manifests itself in the context of smart products and services by playing a role in the interaction that happens between the customer and the various actors of the smart service system. Depending on the context, the number of actors can vary. However, each smart service system has at the minimum one creator of the product (e.g. Google, Amazon, Apple) and one smart service provider (e.g. government, utility company) with a smart product as boundary-object, that can interact with at least one smart service customer (Beverungen et al., 2019). Smart services and their smart products co-create smart service experiences and benefits with the customer (Anke, 2019). Customers invest their resources in terms of emotional, cognitive and behaviour responses to interact and connect with different actors such as the smart service provider and the smart products. They hereby co-create experiences (Kabadayi et al., 2019).

As mentioned before, smart technologies will be more present in our future daily lives (Wünderlich et al., 2015). Along with these, challenges of intrusiveness, privacy concerns, and security risk will arise (Lytras & Visvizi, 2018; Townsend et al., 2011; Wuenderlich et al., 2015). Leaving managers and companies, who want to thrive in these markets no other choice than to understand the challenges and by doing so, try to overcome them. The feelings of intrusion, privacy concerns and security risk might not end after the adoption. Therefore, it is needed to look beyond purchase, which is reflected in engagement (Vivek et al., 2012). Once managers understand how smartness impacts the interaction between the customer and the various actors of the smart service, they will be able to develop smart products and services that will stimulate the interest, feelings and behaviour of customers. Hereby creating future promotors for their smart product and services (Vivek et al., 2012). To help managers in this process, we will provide an answer to the following question: How is the relationship between smartness and customer engagement affected by intrusiveness, privacy, security, and trust?

3. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

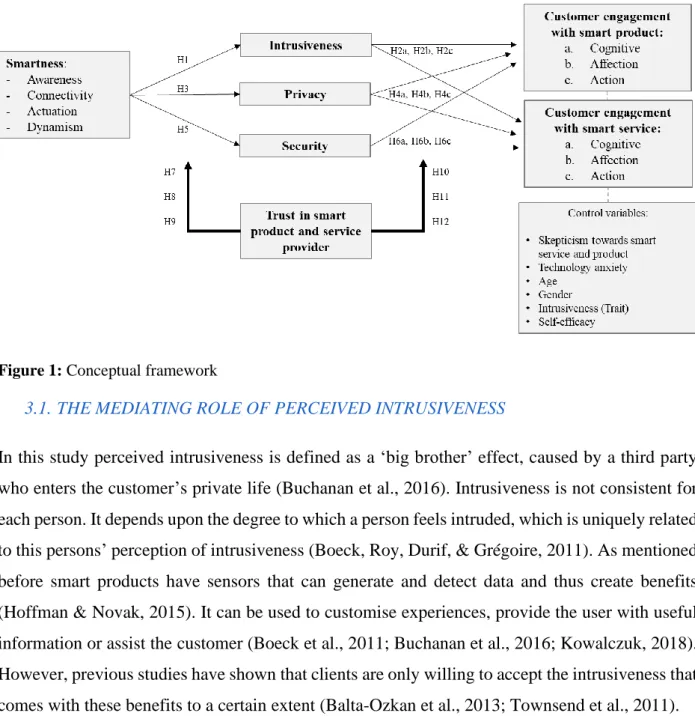

In this section we will discuss three main concepts and one moderating effect through which we will measure the impact of smartness on customer engagement with smart offerings. These concepts include intrusiveness, privacy, security as mediators and trust as the moderator. Drawing on the psychological ownership theory, the information boundary theory and the personalisation privacy paradox, we develop the following conceptual model (see Figure 1) and corresponding hypotheses.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework

3.1. THE MEDIATING ROLE OF PERCEIVED INTRUSIVENESS

In this study perceived intrusiveness is defined as a ‘big brother’ effect, caused by a third party who enters the customer’s private life (Buchanan et al., 2016). Intrusiveness is not consistent for each person. It depends upon the degree to which a person feels intruded, which is uniquely related to this persons’ perception of intrusiveness (Boeck, Roy, Durif, & Grégoire, 2011). As mentioned before smart products have sensors that can generate and detect data and thus create benefits (Hoffman & Novak, 2015). It can be used to customise experiences, provide the user with useful information or assist the customer (Boeck et al., 2011; Buchanan et al., 2016; Kowalczuk, 2018). However, previous studies have shown that clients are only willing to accept the intrusiveness that comes with these benefits to a certain extent (Balta-Ozkan et al., 2013; Townsend et al., 2011).

By increasing the degree of smartness to enable more accurate smart services, customers will lose a certain level of control over their smart product. Although the customer is the legitimate owner of the smart object, the reduction of perceived ownership caused by increased smartness changes one’s perception over the object. The individual will perceive the smart offering as an intruding object and service, which leads to an increase in the customer’s perceived intrusiveness concerns.

H1: The degree of smartness will have a positive impact on the

intrusiveness concerns of a customer.

Given that previous research on self-service technology innovations highlighted the impact of control on perceived risks and adoption intention we argue that an explanation could be found in the psychological ownership (PO) theory (Lee & Allaway, 2002). The psychological ownership (PO) theory reflects the perceived possession over an object. Pierce, Kostova and Dirks (2001) noted that actors feel like the object or so-called target is “theirs”. Further, they argued that the existence of psychological ownership emerges from three main factors: efficacy and effectance, self-identity, and having a place. However, more important is how the feeling of ownership gets formed. First, Pierce et al. (2001) argued that control plays an important role. Whenever a person feels like he is in control of the object (material or immaterial), it becomes part of himself. More control over the object should thus result in a higher level of perceived ownership. If we translate this to a smart offering less smartness in the form of awareness, connectivity, actuation and dynamism will result in a higher level of control by the customer and thus a higher level of perceived ownership and vice versa.

Following the definition of the four smartness characteristics, we come to an explanation (Henkens et al., 2020). Lower awareness, connectivity, actuation and dynamism result in respectively: fewer sensors, which can gather information about the environment (and thus the customer) and itself, which gives the customer some control regarding the amount and type (e.g. text, audio, visual) of information that is being gathered; lower interaction between the different actors, which means that the customer has more control over where the shared information goes; less actuation of the device, which increases the control of the customers since the devices will not be able to act without the intervention of the customer; a device which has little knowledge about the customer preferences and habits, which results in more control for the customer over his private life. This increase in the customer’s control will result in more perceived ownership. However, the smart market is creating products that score higher on the four smartness characteristics, which is found to be concerning (Buchanan et al., 2016). Since the degree of control over the object will be

reduced when smartness increases, the degree of perceived ownership will negatively be affected (Pierce et al., 2001).

Second, Pierce et al. (2001) mentioned that the more intimately a person knows the object, the more he or she feels ownership, even though this person is not the real owner of the object. Last, this feeling of ownership also occurs when a person invests time, energy, effort and attention into the object. From this sense of ownership responsibilities and rights towards the object emerge along with certain behaviour and feelings (Pierce et al., 2001).

Previous research found that intrusiveness concerns positively influence customer resistance to smart services (Chouk & Mani, 2019). If this form of intrusion already has a negative impact on the attitude towards usage, it can be assumed that this negativity will also be present in the further stage of engagement. Further, Jaakkola and Alexander (2014) argued that a sense of ownership is a key driver for the behavioural aspect of customer engagement. This led us to believe that a possible explanation could be found in the combination of the Psychological ownership theory and the Information Boundary Theory (IBT) (Pierce et al., 2001; Stanton & Stam, 2003).

Previous research by Stanton and Stam (2003) on worker privacy developed the first steps to the information boundary theory. At the core of this theory, you have respectively “boundary opening” and “boundary closure”, which is the revealing or the withholding of information (Stanton & Stam, 2003). If an external party does not respect these boundaries, it could result in intrusiveness concerns. As mentioned by Stanton and Stam (2003), subjects do not openly accept information technology due to the possible exposure of valuable personal information. Based on a risk-control analysis the individual must decide whether or not the demanded information is acceptable and worth sharing. If the individual finds the disclosed information to be (un)acceptable he or she will not (will) perceive intrusion and thereby have a lower (higher) level of concerns. This will result in boundary opening (closure), where the information is (not) being shared with the other party (Xu, Dinev, Smith, & Hart, 2008).

To decide the desired level of engagement, the customer does a risk-control analysis to determine how much information he or she is willing to reveal while using his/her smart product and service. Hereby the cognitive component of customer engagement becomes stimulated. The service provider must respect these predetermined boundaries. Otherwise, the perceived intrusion will result in boundary closure. In this “protective” stage the customer will withhold personal information to prevent negative outcomes (Stanton & Stam, 2003). This will affect the activation aspect of engagement. Further, due to the lack of control over the smart object the user feels less

ownership. This will lead to certain negative behaviour and feelings (e.g. intrusion) (Cichy, Salge, & Kohli, 2014; Pierce et al., 2001). This feeling of intrusion, could then negatively impact the emotional feelings towards the smart product and service, which impacts the positive affection side of customer engagement.

H2a: Perceived customer intrusiveness has a positive impact on

the cognitive aspect of a customer’s engagement with smart product and service.

H2b: Perceived customer intrusiveness has a negative impact on

the affection aspect of a customer’s engagement with smart product and service.

H2c: Perceived customer intrusiveness has a negative impact on

the action aspect of a customer’s engagement with smart product and service.

3.2. PRIVACY CONCERNS AS A MEDIATOR BETWEEN SMARTNESS AND CUSTOMER ENGAGEMENT

“Whenever an appliance is described as being ‘smart’, it’s vulnerable” (Hypponen & Nyman, 2017, p.6). It is this risk and vulnerability that worries customers to use smart services (Hubert et al., 2019). Privacy concerns in the context of this study can be seen as the concern that the service provider who has access to one’s personal data (e.g. financial data, geographical location or internet search history) will abuse his privilege by providing this information to interested third parties.

The typical architecture of smart devices can impact privacy concerns differently compared to traditional devices (Bugeja, Jacobsson, & Davidsson, 2017). Therefore, another degree of smartness will result in another level of privacy concerns. Following the PO theory, customers who feel that the private data is “theirs”, will want some level of control over this data (Pierce et al., 2001). However, given certain characteristics of smart offerings, this control is compromised. After all, an increase in smartness results in more sensors, which can capture private data such as conversations (awareness). More connected actors, who can potentially share this information (connectivity). More ability of the device to decide what it should do with this data (actuation). And lastly, an increase in the knowledge of service providers on the preferences and habits of the

customer (dynamism) (Henkens et al., 2020). Since the customer suffers from loss of control over his/her personal data, caused by more smartness, privacy concerns will emerge.

H3: The degree of smartness will have a positive impact on the

perceived privacy concerns of a customer.

As remarked by other researchers “one piece of innocent data” does not have a strong impact on the customer’s privacy (Balta-Ozkan et al., 2013). However, the collection of all data can be used to generate a complete image of the customer’s life, resulting in serious privacy implications (Smith, Milberg, & Burke, 1996).

Prior studies of Dinev et al., (2008) and Dinev and Hart (2006) found that users were afraid that their sensitive data would be found or abused by a third party or unauthorised individuals. Therefore, they were not willing to provide personal information. Although this study was performed in a short-term transactional context, it still shows some value for long term implications. If costumers are not willing to share their data in the short-term, it is questionable that they will in the long run. Further, the study of Keith, Thompson, Hale, Lowry and Greer (2013) on mobile devices and their apps concluded that first, privacy concerns positively impact perceived privacy risk and second, that the perceived privacy risk reduces the individual's intent to disclose information. This has an impact on the customer’s behaviour. Last, recent research done by Wiegard and Breitner (2019) on smart services in healthcare found that when customers perceive privacy risk, they will perceive the offering as less valuable, which in its term reduces the intention to use.

The impact of privacy concerns on engagement can thus be a result of the personalisation privacy paradox and the PO theory. First, the personalisation privacy paradox plays a role in the customer’s cognitive process. Privacy concerns stimulate the customer to think, and evaluate on whether the benefits of more personation and accuracy outweigh the risk of losing personal data to unauthorised persons. The reasoning originally comes from the privacy paradox theory. In this theory, a privacy calculus is made to determine whether are not the benefits outweigh the risks of sharing data. Within smart offerings this calculus often weights the personalisation against the reduction of privacy, known as the personalisation privacy paradox (J. M. Lee & Rha, 2016). In core, the theory is based on rational people. However, bounded rationality impacts the decision process. Consumers must base their decisions on incomplete information and limited time and cognitive ability. This results in the use of simplified, heuristic models, which create room for

errors. Therefore, the intended behaviour might not reflect in the actual behaviour (Barth & de Jong, 2017; Gerber, Gerber, & Volkamer, 2018).

H4a: Perceived privacy concerns have a positive impact on the

cognitive aspect of a customer’s engagement with smart product and service.

The emotions of the customer also get impacted by privacy concerns. If the smart offering cannot guarantee the control and thus perceived ownership over the customer’s personal data, the occurred privacy concerns will be accompanied by frustrations and stress (Cichy et al., 2014). This has a negative impact on customer engagement affection.

H4b: Perceived privacy concerns have a negative impact on the

affection aspect of a customer’s engagement with smart product and service.

Last, Gerber et al. (2018) argued that control impacts privacy concerns. When given control over the disclosure and processing of data, the customer has less perceived privacy concerns. As a result, the consumer feels more open to share information. On the contrary, when control is taken away (which is the case with higher smartness), higher perceived privacy concerns will result in less openly sharing of information. As a result of privacy concerns, boundary closure will occur, which in turn will negatively impact the behaviour and thus action component of engagement.

H4c: Perceived privacy concerns have a negative impact on the

action aspect of a customer’s engagement with smart product and service.

3.3. SECURITY RISK AS AN EXPLANATORY VARIABLE

Most of the private data is stored in clouds to get analysed. It is the job of service providers to protect this database against hackers and leaks. Hacks and leaks can be situated at various levels. The devices, the communication line (between the various devices and services) and the software program created by the service provider must all be protected or encrypted (Bugeja et al., 2017). It is essential that each level is as strongly protected as the others because the weakest link defines the strength of your entire security system (Balta-Ozkan et al., 2013).

Sometimes this weakest link can be an employee of your company. Recently over 1.000 Google recordings were leaked by a language reviewer to the Belgian broadcaster VRT, of which 153

were recorded without the build-in activation phrase (Langley, 2019, July 11). The leaks included confidential phone calls, bedroom chatter, verbal quarrels and parents talking to their children (BBC News, 2019, July 12).

Security is not just the responsibility of the service provider or its employees. For some part of the security the service provider is not responsible, namely ‘the people problems’ (Hypponen & Nyman, 2017). When customers are not changing default passwords or accidentally giving out sensitive private information to phishers, the services provider cannot be held responsible. Therefore, customers also have a role in the protection of their data.

While regular devices do not connect with different actors, smart offerings do. The higher the connectivity, the more links inside your security system that you need to protect. This decrease of control over security creates more potential for hacks and leaks. Further, more awareness results in more sensors, who gather information about the customer and his environment. These sensors can be hacked and are thus a risk for the customer. Next, when a smart offering is hacked, its actuation component can be controlled by the hacker to perform unwanted actions. Last, the dynamic part could reveal personal preferences, locations, contact and habits to hackers, which contributes to the security risk of the customer (Henkens et al., 2020). Therefore, we suggest the following hypothesis:

H5: The degree of smartness will have a positive impact on the

perceived security risk

Previous studies, which can found in Table 2, have shown that perceived security risk impacts the adoption of smart services. First, Mani and Chouk (2018) found that security risk is a functional risk barrier that positively affects customer’s resistance to smart services. Second, Chouk and Mani (2019) found that risk plays an important role in the acceptance of smart service applications. Further, the study of Hubert et al. (2019) concluded that perceived security risk negatively influences perceived usefulness via perceived overall risk.

On the other hand, the study on smart lockers by Yuen et al. (2019) found that more and better security (and thus low risk) results in more perceived value, which in its term increases the intention to use the smart product.

The psychological ownership theory can explain the link between perceived security risk and engagement. The customer feels strong ownership towards his data. However, he/she has little to no control over it, since the security of the data lies in the hands of the service provider. This

conflict, in combination with the high need for personal control over their data can result in dysfunctional behaviours such as frustration, stress and the rejection of sharing information (Pierce et al., 2001). This feeling then further impacts the affection characteristic of engagement. Next, following the IBT and the personalisation privacy paradox the risk of losing data due to inadequate security might outweigh the benefit of personalisation, which will result in boundary closure and thus reduce the willingness to share information (e.g. stimulation of cognitive and negative impact on activation).

H6a: Perceived security risk has a positive impact on the cognitive

aspect of a customer’s engagement with smart product and service.

H6b: Perceived security risk has a negative impact on the cognitive

aspect of a customer’s engagement with smart product and service.

H6c: Perceived security risk has a negative impact on the cognitive

aspect of a customer’s engagement with smart product and service.

3.4. TRUST IN THE SERVICE PROVIDER AS A MODERATOR

Mayer, Davis and Schoorman (1995, p.712) defined trust as “ the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party”. Critical in this definition is that trusting the other party means having some willingness to be vulnerable, since the customer has no control or ability to monitor the actions of the other party. This reflects that the custom has something at risk, something that can be lost (Mayer et al., 1995). Although trust means letting go of control, it also gives some control to the customer, since it reduces behaviour uncertainty (Pavlou, 2003). This is partly reflected in the definition of trust by Brodie et al. (2011, p.261): “consumer-perceived security/reliability in brand interactions and the belief that the brand acts in consumers’ best interests”. When you trust your service provider that he will act in your best interest, it will feel as if he will behave the way you would do, resulting in more certainty. These definitions stress the three characteristics of trustworthiness in a trustee: ability, benevolence and integrity (Mayer et al., 1995).

First, ability reflects the expectations that the competences of the trustee are sufficient to do the required task. Since a trustee can be skilled in sector X, but not in Y, the trust will differ according to the domain. Second, when a trustee is considered benevolent, the trustor (e.g. customer) believes that the trustee wants to do something good for him/her besides making a profit. Last, integrity describes the principles of a trustee, which are accepted by the trustor. When a service provider does what was promised and has a strong sense of justice he will score high on integrity (Mayer et al., 1995).

Based on the mentioned definitions and characteristics of trust we propose the following definition that fits the context of our study. First, trust is the customer’s confidence that his or her vulnerable data gathered by smart offerings will be secure in the cloud of his/her provider. Second, it is the belief that the provider is skilled to deliver useful personalised content to the customer in exchange for valuable personal data (ability and vulnerability). Last, it reflects the expectation of the customer that his/her private data will solely be used by the service provider to generate optimal and personalised content (benevolence and integrity).

It is important to remark that trust in smart meters or cities can have different dimensions than trust in smart hotel services. This all depends on the context of the smart product and service application (Harwood & Garry, 2017). Second, comparable with e-commerce, the transactions and usage of smart offerings are uncertain and involve risk. In these uncertain environments, trust plays a crucial role (Pavlou, 2003; Schoenbachler & Gordon, 2002). AlHogail (2018) explained that in this uncertainty risk and vulnerability trust becomes a vital component, since it affects the behaviour intention of a customer to adopt an IoT driven service or product. Last, the qualitative research of Lau, Zimmerman and Schaub (2018) found that customers feel less concerned about their privacy when there is trust in the company.

An example of the crucial role of trust is demonstrated in recent research by Yang et al. (2017). They found that trust positively affects the attitude, the perceived behaviour control and the subjective norm (options or suggestions from people who influence the customer’s behaviour) of smart home services, which in turn positively impacted the intention to use. Another research on smart grids argues that trust reduces scepticism and increases more positive project outcomes (Gangale, Mengolini, & Onyeji, 2013). Therefore, we assume that trust will play a positive role in the further stage of engagement. Third, Brodie et al. (2011) noted that trust could both be an antecedent (in the case of existing customers) as a consequence (in the case of new customers) of engagement. Last, trust could be a mechanism that regulates the relationship between the service

provider and the customer, leading to benevolence and integrity (e.g. non-opportunistic behaviour) (Vivek et al., 2012). Given all these findings, we believe that trust needs to be taken into consideration in our research.

As mentioned above we, suggest that the degree of smartness is negatively related to issues such as the amount of control a customer has over his data storage and security. Taking into account the psychological ownership theory, this lack of control over the uncertain situations will evoke intrusiveness concerns, privacy concerns and security risk. However, according to Pavlou (2003), these behaviour uncertainties can be reduced by trust since it gives the customer some sense of control over the uncertain transactions. If we adopt this to the PO theory, the increase of control given by trust will reduce the positive effect that the degree of smartness has on intrusiveness concerns, privacy concerns and security risk. Therefore, we suggest the following hypotheses with trust as a moderator:

H7: The effect that the degree of smartness has on intrusiveness

concerns will be weaker when the customer has trust in the smart product and service.

H8: The effect that the degree of smartness has on privacy

concerns will be weaker when the customer has trust in the smart product and service.

H9: The effect that the degree of smartness has on security risk

will be weaker when the customer has trust in the smart product and service.

On the other hand, trust can also have a moderating effect on the relationship between intrusiveness concerns, privacy concerns, security risk and customer engagement with smart offerings. Stanton and Stam (2003) remarked the importance of trust in the information boundary theory. Trust makes voluntary sharing of information more convenient, resulting in a strong impact on boundary opening. This is consistent with the findings of Schoenbachler and Gordon (2002), who found that trust positively influences a user’s willingness to provide information in the computer/ home electronics industry. Since trust facilitates boundary opening and thus the willingness to share information, it will reduce the negative impact that intrusiveness concerns, privacy concerns and security risk have on the activation aspect of customer engagement. Further, from a PO theory, the increase of control given by trust will reduce dysfunctional behaviours such as frustration, stress

and thereby weaken the effect that intrusiveness concerns, privacy concerns and security risk have on the affection aspect of customer engagement. Last, the relationship between intrusiveness concerns, privacy concerns and security risk on the cognitive aspect of customer engagement will be weakened. After all trust impacts the personalisation privacy calculus, since it takes away some uncertainty and thus some risk. This results in a lower need for the customer to actively think and learn about the risks and concerns of smart products and their services. Therefore, we suggest the following hypotheses:

H10: The effect that intrusiveness concerns have on customer

engagement (all aspects) with smart product and service will be weaker when the customer has trust in the smart product and service.

H11: The effect that privacy concerns have on customer

engagement (all aspects) with smart product and service will be weaker when the customer has trust in the smart product and service.

H12: The effect that security risk has on customer engagement (all

aspects) with smart product and service will be weaker when the customer has trust in the smart product and service.

3.5. CONTROL VARIABLES

Customer’s answers could be influenced by his/her demographics, personality and traits. Therefore, it is important to control for these variables to see how they impact their choices and their willingness to engage in smart services and products.

First, some people are not educated in smart technologies. Due to the lack of knowledge, potential customers can be more sceptical towards IoT applications (Huijts, Molin, & Steg, 2012). This sceptically could result in more perceived security risks and government surveillance, which would lead to higher resistance and thus less engagement in smart speakers (Chouk & Mani, 2019). Therefore, we will control for scepticism towards smart services and product.

Second, certain demographics can play a role. Recent research on mobile banking found that the odds of young people adopting these services were higher than the odds of more mature people (Laukkanen, 2016). Since mobile banking also includes some uncertainty and vulnerability

comparable to smart offerings, it is doubtful that older people will engage in smart services and products. Therefore, we will control for age. Further, gender can also influence the open-mindedness toward smart technology. While Mani and Chouk (2018) found that women are more resistant to IoT devices, Yang et al. (2017) found the opposite. If they are not even willing to try the device, it will be very unlikely that they are interested in engagement. We will code this variable as followed: 1= Man, 0= Woman.

Even though Mani and Chouk (2018) found an insignificant impact of technology anxiety on the resistance of smart products, we will control for technology anxiety to see whether or not the customer feels any discomfort and insecurity surrounding technological changes. While some people tend to be optimistic about the IoT and smart products, others have pessimistic views towards this embedded technology. Therefore, technology readiness plays an important role in the intention to use a smart product (Caputo, Scuotto, Carayannis, & Cillo, 2018). Lin and Hsieh (2006) found that technology readiness is influenced by two positive and two negative dimensions, respectively optimism and innovativeness, and discomfort and insecurity. Further, they found that technology readiness led to positive behavioural intentions, which is related to a customer’s firm loyalty and positive recommendations (Lin & Hsieh, 2006). These are all signs that an engaged customer would show.

Fourth, as mentioned by Boeck et al. (2011), intrusion depends on a person’s own perception of intrusiveness. Some people might thus have a higher feeling of intrusion due to their personality traits. Given that we expect intrusiveness to have a negative impact on engagement, controlling for intrusion traits could provide users with useful insights.

Last, we should control for self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is the extent to which a person believes in his or her ability to use a certain product/service, which in our case will be a smart product/service (Mani & Chouk, 2017). As mentioned by Dabholkar and Bagozzi (2002), self-efficacy could influence behaviour intentions, which in turn impact the decision to use technologies. Mani and Chouk (2017) argued that the negative impact of self-efficacy on consumer resistance is related to the customer’s confidence. The more confidence he or she has about his or her ability to understand and use a product, the less resistant they will be. Therefore, self-efficacy could have a positive influence on engagement.

4. METHODOLOGY AND RESEARCH DESIGN

4.1. CONTEXT AND SCENARIOS

To capture how an increase in smartness impacts our mediators, moderator, and customer engagement components, we had to manipulate the smartness based upon the four characteristics by means of scenarios. We gradually increased the awareness, actuation, connectivity and dynamism of the smart offering. This resulted in three scenarios: no smartness (control scenario), low smartness and high smartness. While low smartness refers to low awareness, actuation, connectivity and dynamism, high smartness reflects high awareness, actuation, connectivity and dynamism. Further, at the beginning of our survey, we randomly exposed each participant to one of the three scenarios, which were provided by Henkens et al. (2020) and adapted to the context of our study. This was done out of the expectation that the smart product and service might not be broadly used in Belgium. Each scenario was translated to Dutch for our Belgian respondents (see Appendix A).

For the smart product, we chose the digital assistant because its market is a booming market with a variety of possibilities. You can make phone calls, buy products, schedule meetings, check the weather, ask for jokes, control other smart devices, or listen to music. The market is expected to generate a global revenue of 35.5 billion U.S. dollars by 2025, therefore making in a multifunctional tool with great potential (Statista, 2020c). Following the vision of Wuenderlich et al. (2015), we expect that in the years to come smart assistants will become more present in the daily lives of Belgian people. To be ahead of this upcoming market penetration we would like to provide managers with sufficient knowledge to grasp the future digital assistants’ market potential. Different brands such as Amazon, Google and Apple understand the possibilities of this market and have already invested in digital assistant and their services. Digital assistants are products that can help customers with managing and enjoying their lives (Kowalczuk, 2018). Before using the digital assistant, customers must install respectively the Alexa, the Google home, or the Siri application to be able to connect their smartphone or other products to the device. Further, for optimal user experience, additional data such as financial data, home address, and personal contact numbers are asked. Each time a user wants to activate the service of the device, a build-in activation phrase such as ‘hey Google’ is needed. Thanks to the voice recognition tools, the assistant can analyse the user’s question and respond with a fitting answer. After several times of

using the device, the assistant will know your vocabulary usage or your preferences, resulting in more accurate results.

The digital assistant is not a stand-alone product. It is connected with various other smart products such as a smart tv, a smart fridge or smart lightning. These products have their own smart service, which is offered by a smart service provider such as Google, Amazon or Apple. The services can create entertainment or help customers to manage their lives. In our study, we used a domestic smart service called ‘domotics’. This simplified smart service includes a smart vacuum cleaner and other tools to help the customer with their household chores.

4.2. MEASUREMENT

We translated our questionnaire to make it understandable for our Belgian respondents. The structure of our survey was as followed. First, the respondents were asked to evaluate the realism of the scenario, followed by several questions concerning the smartness of the digital assistant. Second, the participants’ perceived concerns, risks and trust were measured. Next, we asked them to evaluate some statements about their engagement towards smart service (home automatisation) and smart products (digital assistant). Afterwards, we proposed some questions to measure the participants’ general mindset, traits and behaviour. We finished our survey by asking for demographic data (see Appendix B).

To measure our dependant and independent variables, we used scales from various researches. Afterwards, we adapted some of these scales to match our digital assistant context (see Appendix C). All scales, except for age and gender, were measured using a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7).

First, we used the scales of Van Vaerenbergh, Vermeir and Larivière (2013) and Dabholkar and Bagozzi (2002) to measure the realism of the proposed scenarios. Second, to measure smartness we use the scale of Henkens et al., (2020), which is based on the scales of Rijsdijk et al. (2007). Third, we adapted the scales of Hsu and Lin (2016), Hollebeek et al. (2014) and Islam, Rahman and Hollebeek (2017) to measure customer engagement. Fourth, perceived intrusiveness was measure using van Doorn and Hoekstra (2013), Edwards, Li and Lee (2002) and Gutierrez, O’Leary, Rana, Dwivedi and Calle (2019). Fifth, perceived privacy concerns were measured using the scale of Xu et al. (2008). Sixth, we used an adapted scale of Yang et al. (2017) to measure trust in the service provider and the digital assistant. Next, perceived security risk was measured using the scales of Kim, Tao, Shin and Kim (2010). Since this scale measures the opposite of risk, we

will recode this variable later on. For technology anxiety, we used the sales of Mani and Chouk (2018). Finally, scepticism towards smart product and services, and self-efficacy were respectively measured using the scales of Chouk and Mani (2019), and Dabholkar and Bagozzi (2002), Curran & Meuter (2005) and Mani and Chouk (2017).

4.3. DATA COLLECTION AND SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICS

We collected the data in April 2020. The survey was initially pretested by five Belgian respondents of our target group, ages 21, 21, 23, 30 and 50. This led to a revision of the survey structure and some modifications to the translation of the scales. We reached a total of 1118 respondents. However, after removing the participants that did not complete the survey our sample size existed out of 533 respondents. Further, we controlled for the attentiveness of our participants by asking them once to select ‘Helemaal niet akkoord’. We removed all respondents who did not select the correct answer. In our final survey sample 483 respondents remained. They were assigned to ‘no-smartness’ (control scenario), ‘low-‘no-smartness’ and ‘high ‘no-smartness’ which recorded respectively 147, 157 and 179 respondents. 58.8% percent of the respondents were women, the other 41.2% percent were men. Their ages ranged from 18 to 72, with an average age of 32.36 and a standard deviation of 13.28. In general, our sample generally existed out of participants with the following personal traits: low technology anxiety, high self-efficacy, low to neutral scepticism. Further, the inherent intrusiveness trait was well-represented in all three categories.

Table 4: Descriptive statistics

Categories* Frequencies Percentage (%) Mean Median

Age 32.36 26.00 18-25 241 49,90% 26-35 87 18,01% 36-45 50 10,35% 46-55 68 14,08% 55< 37 7,66% Technology anxiety 2.68 2.33 Low 339 70.18% Neutral 97 20.08% High 47 9.74% Self-efficacy 5.16 5.50 Low 46 9.53% Neutral 107 22.15%

Table 4: Continued

Categories* Frequencies Percentage (%) Mean Median

High 330 68.32% Scepticism 3.41 3.33 Low 208 43.10% Neutral 220 45.51% High 55 11.39% Intrusiveness (Trait) 3.89 4.00 Low 169 34.99% Neutral 177 36.65% High 137 28.36%

Note: * Low: ≤ 3, Neutral: 3 < X < 5, High: 5 ≤ X

4.4. QUALITY OF THE CONSTRUCTS

To prepare our data for analysis we recoded all components of security and the third component of self-efficacy (self-efficacy_3). This resulted in a scale that is the opposite of security (e.g. security risk) and a consistent self-efficacy scale.

To confirm the convergent validity and the reliability of all our adapted scales we performed a confirmatory factor analysis (Principal axis factoring, Oblimin). Based on the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) criteria, every variable except for self-efficacy was mediocre (0.600) or higher (Kaiser & Rice, 1974). Further, the Bartlett sphericity test was significant for all our factors. Next, we followed the Kaiser-Guttman criterion, which states that all the factors must have an initial eigenvalue greater than one. Last, we controlled if every factor loading in the factor matrix was higher than 0.500 (Osborne & Costello, 2004). All factors except Trust_3 (0.499) and self-efficacy_3 (0.050) were fine. Although it is recommended to keep three items for each factor, we followed the strict criteria and removed Trust_3 and self_efficacy_3. This resulted in a KMO of 0.500, which is not ideal.

To verify the reliability of the factors, a reliability analysis was performed. After removing the above-mentioned items of trust and self-efficacy we found Cronbach’s Alpha ranging from 0.731 to 0.947, which means that they are all good or excellent (see Appendix D) (Hair, Black, Babin & Anderson, 2014).

Afterwards, we controlled for multicollinearity. First, the Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) of all of our independent variables ranged from 1.048 to 2.097. They were lower than the common

cut-off point of 10, and smaller than the stricter threshold of 3.33 (De Pelsmacker & Van Kenhove, 2014; Hair et al., 2014). Second, we looked at the correlation matrix for any signs of abnormal correlations. As can be seen in Table 5, we notice that there are significant correlations between the various customer engagement variables, which are higher than 0.500 (De Pelsmacker & Van Kenhove, 2014). This is not unusual since all variables measure the same construct, namely customer engagement. Further, a smart product is nearly always linked with a specific smart service, which makes it more difficult for a customer to separate the two constructs from each other. This could be an explanation of why CE product variables correlate highly with CE service variables.

Next, we remark that our four key variables (e.g. Intrusiveness, Security, Privacy and Trust) show some intercorrelations with each other (see bold). Although these concepts are theoretically different from each other, in practice, they are somewhat intertwined. For example, if you are worried about the security of your system, it is not uncommon that you will also be concerned about data privacy etc.

Additionally, the higher correlation between technology anxiety and self-efficacy can potentially be explained by the fact that if a person has anxiety of technology, he/she will not often use technological products or services. This will result in lower self-efficacy. Last, we found no abnormalities in the sign of the other intercorrelations.

One might argue that only two of our three expected mediators showed a positive correlation with the cognitive aspect of customer engagement. As a result of the emerging concerns, customers must think about the smart product or service to determine how it can further affect their usage. This leads to an increase in the cognitive aspect of engagement. On the other hand, security risk showed an insignificant, negative correlation with the cognitive aspects. We know that more risks can negatively influence perceived usefulness (Hubert et al., 2019). The reduced usefulness could further result in lower interest and thus lower cognitive stimulation. This explains the negative sign.

In summary, there are some small signs of multicollinearity (e.g. 2< VIFs). Further, our correlation matrix shows some intercorrelations above the preferred 0.500 (De Pelsmacker & Van Kenhove, 2014). To reduce this slight indication of multicollinearity we use centralised data in our Hayes regression.