CAREER COMPETENCES AND

CAREER OUTCOMES

A critical analysis of concepts and

complex relationships

CAREER COMPETENCES AND CAREER

OUTCOMES

A critical analysis of concepts and complex

relationships

Heidi Knipprath & Katleen De Rick

Promotor: Katleen De Rick

Research paper SSL/2013.07/4.3

Leuven, 30 september 2013

●●●●●

Het Steunpunt Studie- en Schoolloopbanen is een samenwerkingsverband van KU Leuven, UGent, VUB, Lessius Hogeschool en HUB.

Gelieve naar deze publicatie te verwijzen als volgt:

Knipprath H. & De Rick K. (2013), Career competences and career outcomes, Steunpunt Studie- en Schoolloopbanen, Leuven.

Voor meer informatie over deze publicatie heidi.knipprath@kuleuven.be; katleen.derick@kuleuven.be

Deze publicatie kwam tot stand met de steun van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap, Programma Steunpunten voor Beleidsrelevant Onderzoek.

In deze publicatie wordt de mening van de auteur weergegeven en niet die van de Vlaamse overheid. De Vlaamse overheid is niet aansprakelijk voor het gebruik dat kan worden gemaakt van de opgenomen gegevens.

D/typ het jaartal/4718/typ het depotnummer – ISBN typ het ISBN nummer © typ het jaartalSTEUNPUNT STUDIE- EN SCHOOLLOOPBANEN

p.a. Secretariaat Steunpunt Studie- en Schoolloopbanen HIVA - Onderzoeksinstituut voor Arbeid en Samenleving Parkstraat 47 bus 5300, BE 3000 Leuven

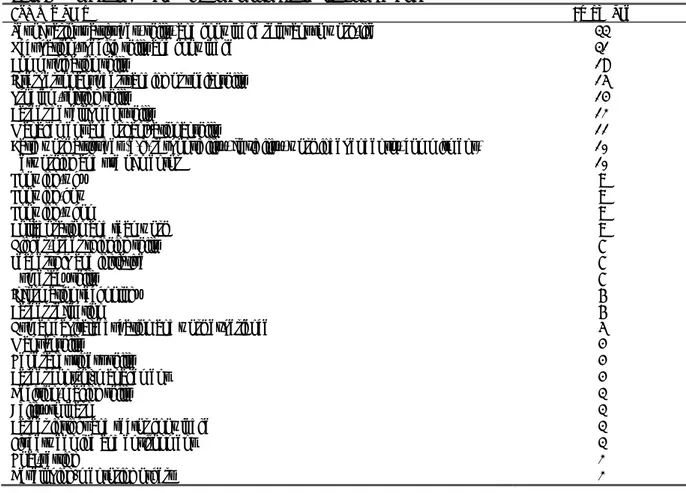

Contents

Beleidssamenvatting

vii

Introduction

1

1.

Why career competences are important

3

1.1

Introduction

3

1.2

The ‘new’ career era

3

1.3

Policy makers’ response to the new career era

6

1.4

Research questions

7

1.5

Research methodology

8

2.

What are career competences?

11

2.1

Introduction

11

2.2

The career competences literature

11

2.3

Establishing a framework by integrating the competences and the three knowing’s

14

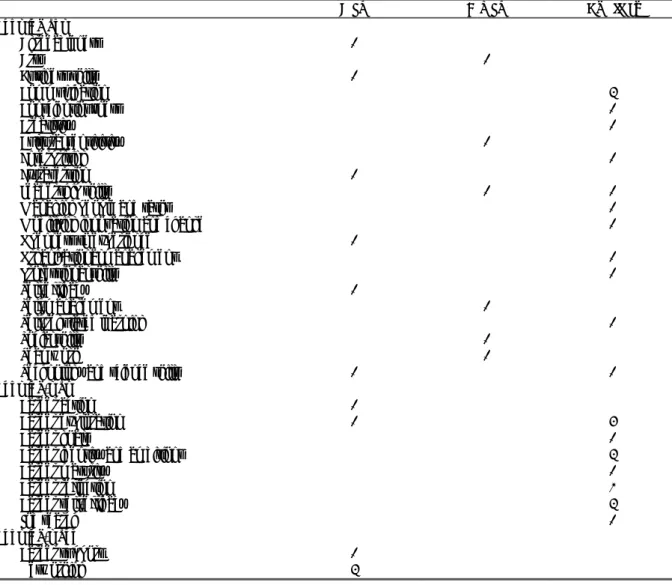

3.

What influences the acquirement, requirement, and use of career competences?

19

3.1

Introduction

19

3.2

Individual characteristics

19

3.2.1

Age

19

3.2.2

Gender

21

3.2.3

Socio-economic background

24

3.2.4

Ethnicity

25

3.2.5

Marital status

26

3.2.6

Other individual characteristics

26

3.3

Initial and continuing education

26

3.3.1

Secondary education

26

3.3.2

Tertiary education

28

3.4

The employment context

31

3.4.1

Type of industry, occupation, sector, and size of firm

31

3.4.2

Work environment, job characteristics and (un)employment

32

3.5

Structural factors

34

3.6

Conclusion

35

4.

The impact of career competences on career outcomes

39

4.1

Introduction

39

4.2

Objective career success

39

4.2.1

Income

39

4.2.2

Job status

41

4.2.3

Career advancement

41

4.2.4

(Re)employment 42

4.3

Subjective career success

43

4.3.1

Perceived career success and marketability

43

4.3.2

Career satisfaction

43

4.3.3

Job satisfaction

44

5.

The interrelatedness of career competences

47

5.1

Introduction

47

5.2

The impact of knowing-how competences

47

5.2.1

On knowing-how competences

47

5.2.2

On knowing-whom competences

48

5.2.3

On knowing-why competences

48

5.3

The impact of knowing-why competences

50

5.3.1

On knowing-how competences

50

5.3.2

On knowing-whom competences

52

5.3.3

On knowing-why competences

52

5.4

The impact of knowing-whom competences

56

5.4.1

On knowing-how competences

56

5.4.2

On knowing-whom competences

56

5.4.3

On knowing-why competences

56

5.5

Conclusion

57

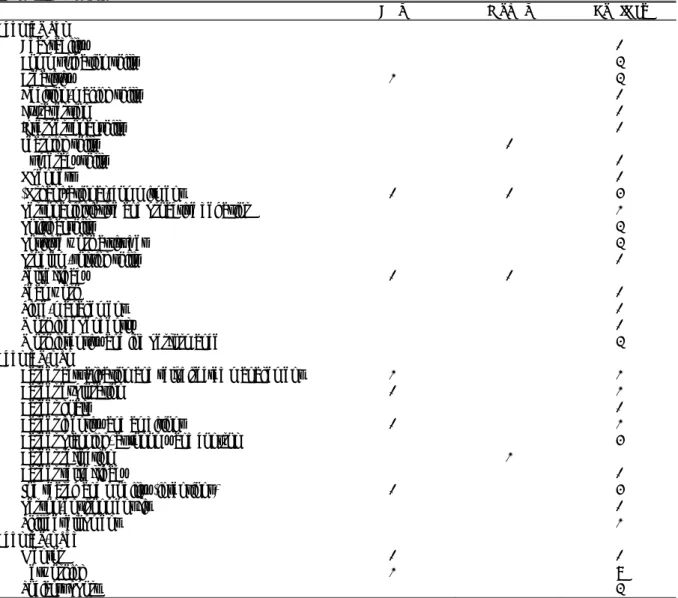

6.

National and international databases

61

6.1

Introduction

61

6.2

PIAAC

61

6.3

REFLEX

62

6.4

Data of the Occupational Careers in Flanders Survey

62

6.5

SONAR

63

6.6

Conclusion

63

7.

Discussion

65

7.1

Introduction

65

7.2

Summary and discussion

65

7.2.1

What sorts of competences are necessary for one’s work-life according to the

research literature?

65

7.2.2

What factors influence the acquirement or use of career competences?

66

7.2.3

Does lifelong learning stimulate the development of career competences?

69

7.2.4

What impact do career competences have on career outcomes?

70

7.2.5

Do structural factors influence the relationship between career competences,

lifelong learning, and career outcomes?

71

7.2.6

Which (inter)national databases enable quantitative and cross-national comparative

research into the development and impact of career competences?

71

7.3

New research directions

71

Annexes

75

Beleidssamenvatting

Soms lijkt het wel of werkgevers steen en been klagen over zowel vroegtijdige als gekwalificeerde

schoolverlaters. Jongvolwassenen zouden, wanneer ze de arbeidsmarkt betreden, onvoldoende

beschikken over de juiste competenties - een set van vaardigheden, attitudes, en kennis - om aan de

slag te gaan. Opvallend tijdens deze waterval van klachten is dat werkgevers zich vooral richten op

zogenaamde generieke vaardigheden zoals organisatie- en communicatievaardigheden. Op een

zelfde manier verklaren beleidsmakers en onderwijsexperts reeds drie decennia lang dat generieke

vaardigheden zoals communicatie- en organisatievaardigheden, sociale vaardigheden, verschillende

vormen van geletterdheid, maar ook metacognitieve vaardigheden belangrijk zijn om te slagen in de

loopbaan en in het leven in het algemeen. Grondleggers van nieuwe loopbaantheorieën hebben het

op hun beurt over loopbaancompetenties die nodig zijn om in een economisch veranderlijke en

technologisch snel evoluerende maatschappij te overleven en een succesvolle loopbaan uit te

bouwen. Het individu zou vooral flexibel en mobiel moeten zijn, competenties moeten hebben die in

verschillende contexten gebruikt kunnen worden, en bereid moeten zijn om steeds bij te leren.

Om duidelijkheid te scheppen over welke loopbaancompetenties in de praktijk precies relevant zijn,

op welke manier ze verworven worden, en in welke mate ze effectief leiden tot een succesvolle

loopbaan in uiteenlopende sectoren en industrieën, hebben we diepgaande analyses uitgevoerd op

basis van empirische studies in verschillende disciplines met de volgende resultaten:

(1) Ondanks de uiteenlopende definities en operationalisaties van loopbaancompetenties door de

onderzoeksliteratuur heen, kunnen we over het algemeen stellen dat er volgens de

onderzoeksliteratuur eensgezindheid bestaat in verschillende landen en in verschillende sectoren

over welke competenties nodig zijn tijdens de arbeidsloopbaan. De competenties kunnen ingedeeld

worden in drie categorieën: (1) generieke en beroepsspecifieke competenties; (2) competenties om

een eigen loopbaan te ontwikkelen; (3) het ontwikkelen en gebruiken van netwerken en steuning

zowel op het werk als daarbuiten.

(2) Individuele achtergrondkenmerken lijken weinig effect te hebben op loopbaancompetenties, in

tegenstelling tot wat men vaak vaststelt in de onderzoeksliteratuur over leerprestaties van

schoolkinderen. Met name socio-economische achtergrond blijkt verrassend genoeg geen effect te

hebben, hoewel de impact ervan op loopbaancompetenties zeer sporadisch werd gemeten. Wanneer

socio-economische achtergrond gemeten wordt, net als etnische achtergrond, dan wordt het vaak

gemeten op basis van kleine en/of homogene steekproeven. Ook de impact van structurele factoren

zoals economisch beleid, onderwijssysteemkenmerken, etc. werd nog niet grondig onderzocht in

voorgaande empirische studies.

(3) De schoolloopbaan en de werkcontext hebben een duidelijk effect op loopbaancompetenties uit

de eerste twee categorieën. Tijdens de schoolloopbaan zorgt een effectief onderwijsprogramma niet

alleen voor de ontwikkeling van loopbaancompetenties, maar zijn ook loopbaanbegeleiding,

werkplekleren, en extra-curriculaire activiteiten erg belangrijk. Ook leeractiviteiten na de initiële

schoolloopbaan, met name het volgen van ‘on-the-job’ trainingen en het informele leren op de

werkvloer met behulp van een mentor, en een open en faciliterende werkomgeving zijn gunstig om

bijkomende competenties te ontwikkelen of te onderhouden. Maar, er bestaat ook empirisch bewijs

dat generieke competenties en sommige competenties voor loopbaanontwikkeling niet zo generiek

zijn als wordt gedacht en dat er duidelijke verschillen bestaan naargelang het beroep en de

arbeidsmarktpositie (bv. inkomen, rang, sector).

(4) De ontwikkeling en gebruik van loopbaancompetenties gaan wel degelijk samen met gunstige

loopbaanuitkomsten, zowel vanuit het oogpunt van het individu bekeken, als vanuit objectieve

criteria bekeken die vooral voor het beleid van belang zijn, zijnde de transitie naar de arbeidsmarkt,

het vinden van werk, en het verwerven van een gunstige arbeidsmarktpositie. Maar, slechts één

derde van de studies over de impact van loopbaancompetenties is longitudinaal, en er moet enige

voorzichtigheid geboden worden met het interpreteren van causale relaties.

(5) Ten slotte heeft diepgaande analyse aan het licht gebracht dat inzicht verkrijgen in de

ontwikkeling en de effecten van loopbaancompetenties niet alleen bemoeilijkt wordt door

cross-sectionele datasets en uiteenlopende en deels overlappende operationalisaties van competenties in

de literatuur, maar ook door complexe relaties tussen de loopbaancompetenties onderling. Enerzijds

zien we dat de relaties tussen competenties voor loopbaanontwikkeling uit elkaar getrokken en in

zekere mate op een tijdslijn gezet kunnen worden waarbij over het algemeen actie volgt na reflectie.

Anderzijds zien we dat relaties tussen loopbaancompetenties onderling wederzijds kunnen zijn. Een

voorbeeld daarvan is de invloed van generieke competenties op het aanwenden van netwerken en

steun, terwijl steun op zijn beurt de ontwikkeling van generieke competenties kan bewerkstelligen.

Ons onderzoek heeft niet alleen nieuwe inzichten voortgebracht en aangetoond dat de realiteit van

ontwikkeling en de impact van loopbaancompetenties complex is. Er zijn ook belangrijke

onderzoekshiaten naar voren gekomen die ingevuld moeten worden in verder zelf uit te voeren

empirisch onderzoek. Met behulp van deze nieuwe onderzoeken, kunnen nieuwe knelpunten

ontdekt worden die relevant zijn voor het beleid. De eerstvolgende vragen die we trachten te

beantwoorden met behulp van grootschalige databestanden naar aanleiding van onze diepgaande

analyses zijn:

(1) In welke mate beïnvloeden de verschillende operationalisaties van loopbaancompetenties het

doen van valide uitspraken over de relatie tussen loopbaancompetenties en andere factoren? Met

andere woorden, leveren de verschillende indicatoren voor loopbaancompetenties, zijnde

competentiegebruik, competentieniveau volgens het individu, en competentieniveau volgens

peilingen, verschillende resultaten op?

(2) In welke mate beïnvloeden achtergrondkenmerken het verwerven en het gebruik van

loopbaancompetenties. Is er sprake van sociale of etnische ongelijkheid in verwerving en gebruik?

Kan leren, tijdens de initiële schoolloopbaan of erna via levenslang leren, het effect van

achtergrondkenmerken verzachten?

(3) Op welke manier verschillen loopbaancompetenties over beroepen heen en leiden deze

verschillen tot verschillende loopbanen?

Onderzoeksvraag (1) is vooral relevant om de onderzoeksresultaten op basis van onderzoeksvraag (2)

en (3) op een correcte manier te kunnen interpreteren.

Introduction

Changes in the economic environment, technological advancements, and demographic changes led

to a transformation of the labor market, shattering notions of job security. In order to survive in this

changing and unpredictable environment, new career theories argue that individuals need to be

flexible and willing to be mobile during one’s career. In addition, individuals need to define their own

needs and career goals. Moreover, they need to continuously develop themselves to pursue these

goals. In order to be able to adjust to changes and attain one’s goals, one does not only need to learn

a life long, but also to acquire career competences which are transferable across different settings.

New career theorists use concepts such as a boundaryless mindset (i.e. the ability to cross

psychological and physical boundaries) and a self-directed protean attitude (i.e. the ability to develop

and pursue one’s career goals) to describe career competences one needs in the new career era.

Likewise, policymakers and educators worldwide have discussed and developed since the 1980s a set

of competences essential to workers’ effective participation in work, but also to adult life in general.

They too emphasize the importance of the transferability of competences, a set of knowledge, skills,

and attitudes, to perform well in (working) life, but they also emphasize that every individual should

acquire these competences.

Policymakers’ and educators’ lists of transferable or generic competences suggest that having a

boundaryless mindset and being able to develop and pursue one’s career goals are not sufficient to

be successful in working life. However, from the new career theorists’ perspective it is clear that their

list of generic competences is not exhaustive either. Therefore, the question needs to be raised what

competences are exactly needed in working life to be employed and to develop a successful career.

In addition, to what extent can career competences be learned through initial education, continuing

education, and lifelong learning activities? What other (structural) factors influence the acquirement

and use of career competences? And finally, do career competences indeed have a positive impact

on one’s career and to what extent?

In this report, we analyze in-depth which competences are necessary in working life according to the

research literature in various disciplines and research performed in various industries and sectors,

from the medical health sector, IT sector, engineering, teaching professions, to the manufacturing

sector. We integrate our findings into a conceptual framework of career competences. In addition,

we use this framework to find factors that influence the acquirement and use of these competences

based on a meta-analysis of the research literature and investigate to what extent these career

competences really have an impact according to empirical evidence. In order to evaluate the impact

of career competences in one’s work life, we use various objective career and subjective career

outcome criteria. Although new career theorists advocate the use of subjective career success

indicators that are idiosyncratic to the person, based on the individual’s own evaluation of his or her

career (Arthur, Khapova & Wilderom, 2005), we argue that the question whether the use and

acquirement of career competences lead to a higher probability of employment is equally important,

as seen from the policymakers’ perspective.

Our in-depth study provides many insights into the complex reality of required career competences

in different sectors and into the interrelatedness of these competences. However, our in-depth study

also reveals various research gaps that need to be filled to understand fully the acquirement and

impact of career competences among various subgroups and to capture areas where policy is

needed.

The structure of the report is organized as follows. In chapter 1, we introduce new career theories

and the response of policymakers on the emergence of the new career era. Next, we introduce our

research questions and research methodology. In chapter 2, we develop a conceptual framework of

career competences. In chapter 3 we discuss the impact of various factors on the development and

use of career competences including individual background characteristics, initial and continuing

education, and the employment context. In chapter 4 we investigate the impact of career

competences on career outcomes. In chapter 5 we address the complex reality of career

competences, as some career competences also appear to have an impact on the acquirement and

use of other career competences. In chapter 6 we evaluate various large-scale (inter)national

databases in order to decide which database can help to address new research gaps and research

questions. In the final chapter, we summarize and discuss our findings and suggest new research

directions.

1. Why career competences are important

1.1

Introduction

We briefly introduce in the first two sections how researchers and policymakers have responded to

major global changes and the emergence of the new career era. In the two remainder sections we

introduce our research questions and research methodology.

1.2 The ‘new’ career era

Major global changes since the late 1970s have influenced the individual’s working life and career (Lo

Presti, 2009). Firstly, changes in the economic environment and unpredictability shattered notions of

cradle-to-grave job security. The individual worker is urged now to adapt to a new flexible world of

work with less security and more contractualised, short-term employment relationships

(Chudzikowski, 2012; Hall, 2004; Mirvis & Hall, 1994; Smith, 2010). Secondly, changes in social

structures and family patterns encouraged the individual worker to strive for a balance between

work and family or other personal interests (cf. Hall, 1976; Lo Presti, 2009). Subsequently, career

paths have become less stable, linear, and progressive, and the individual worker has become

responsible for his or her career development (Lo Presti, 2009). Thirdly, emergence of the

‘information age’ and ‘knowledge-based’ society requires flexible workers with the capacity to

process information and to solve complex workplace problems, but also workers with the willingness

to continuously learn and develop (Maclean & Ordonez, 2007). In order to adapt to this new world of

work, people are being requested by the economy, industry, and society to have ‘new’ knowledge,

skills, and dispositions (Williams, 2005: p. 34).

In conjunction with these worldwide changes in the economic environment and societies,

researchers developed new career theories. In 1976, Hall (1976) introduced the concept ‘protean

career’, referring to the Greek mythological figure Proteus, who continuously changed his shape.

Until that time classical theories on career development were dominant. In Careers in organizations

Hall (1976) wrote that more employees are coming to see their working life as a variable or protean

career.

‘The protean career is a process which the person, not the organization, is managing. It consists of all of the person’s varied experiences in education, training, work in several organizations, changes in occupational ï, etc. The protean person’s own personal career choices and search for self-fulfillment are the unifying or integrative elements in his or her life. The criterion of success is internal (psychological success), not external.’ (p. 201)

To ensure self-fulfillment, professional growth, and career satisfaction (i.e. psychological success) in a

protean career, the individual worker is willing or obliged to make career choices and transitions

leading to a higher degree of mobility than in the case of traditional careers. In contrast, in the

traditional career the individual worker commits him- or herself to a career ladder in an organization

and is more passive in terms of career management. Subsequently, performance in traditional

careers is judged by means of objective criteria such as position level within the organization and

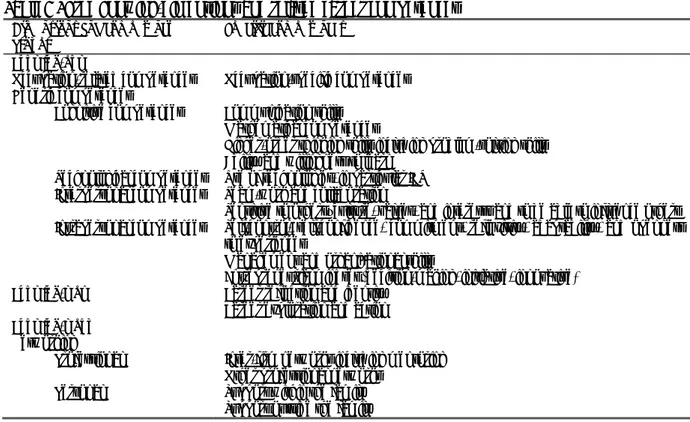

salary (Hall, 1976, 2004; see table 1).

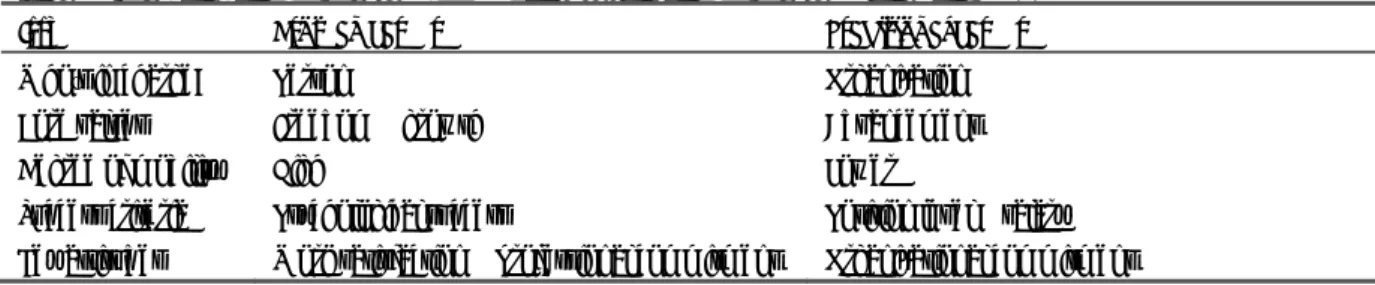

Table 1 Protean career profile versus traditional career profile (Hall, 1976, 2004)

Issue Protean career Traditional career

Who’s in charge? Person Organization

Core values Freedom & growth Advancement

Degree of mobility High Lower

Success criteria Psychological success Position level & salary Key attitudes Work satisfaction & professional commitment Organizational commitment

As a protean worker has greater responsibility for his or her choices and career opportunities, he or

she needs a high level of self-awareness and adaptability (Hall, 1976; Hall & Moss, 1998). Adaptability

enables the person to respond to new demands from and changes in the environment, whereas

self-awareness or self-knowledge enables the person to define his or her own values and (career) goals.

Adaptability and self-awareness are called ‘meta-competencies’ by Hall and Moss (1998), since they

are the skills required to know how to change in one’s work to pursue new opportunities and how to

continue to learn (cf. Hall, 1976). In other words, the protean career is a continuous learning process

(Hall & Moss, 1998). In 2006, Briscoe and Hall (2006) re-acknowledge the need of these

meta-competencies and define the protean career attitude necessary to pursue a protean career. The

protean career attitude consists of being driven by one’s personal values to measure and guide one’s

career priorities and career success (i.e. psychological success). In addition, the protean career

attitude consists of self-directedness in personal career management, having the ability to be

adaptive in terms of performance and learning demands of the career (Briscoe & Hall, 2006).

Eighteen years after the publication of Hall’s Careers in organizations (Hall, 1976), a special issue of

the Journal of Organizational Behavior put forward a new career concept: ‘boundaryless career’

(Arthur, 1994; Bird, 1994; DeFilippi & Arthur, 1994; Mirvis & Hall, 1994). Although this new concept

at the beginning looked rather similar to the concept of protean career, both concepts evolved

distinctly in the area of career studies. In the special issue of the Journal of Organizational Behavior,

Arthur (1994) wrote that ‘the boundaryless career is the antonym of the ‘bounded’ or ‘organizational

career’’ (p. 296), implying that a career does not only move across the boundaries of separate

employers, but also across psychological boundaries allowing the individual worker to reject or

postpone career opportunities for personal or family reasons. In other words, similar to a protean

career path a boundaryless career path is no longer linear or sequential but spiral allowing

interruptions and moving sideways between different jobs and organizations. In addition, the

boundaryless career is sustained by extra-organizational networks and information which allow the

individual to discover and pursue new career opportunities. In this same issue, DeFilippi and Arthur

(1994) describe the competences needed to pursue a successful boundaryless career (table 2). For

both bounded and boundaryless careers, the career competences are knowing-how, knowing-who,

and knowing-why. However, they have different meanings depending on the career path. A bounded

career is characterized by a career identity based on the employment context (knowing-why), the

accumulation of employment-specialized know-how (knowing-how), and the development of

networks that are intra-organizational, hierarchic, and employer-prescribed (knowing-who). The

boundaryless career is characterized by an employer-independent career identity (knowing-why), the

accumulation of employment flexible know-how (knowing-how), and the development of networks

that are inter-organizational, non-hierarchic, and worker-enacted (knowing-who; DeFilippi & Arthur,

1994; see table 2). In other words, competences necessary to successful career development in the

new career era are transferable across organizations or jobs and imply a career identity and networks

not bounded to the current employer. Moreover, these career competences are interdependent

(DeFilippi & Arthur, 1994). Lacking one of the career competences characteristic for boundaryless

careers may constrain the acquirement or utilization of another competence. For example, when

career identity is highly bound to the current employer, the person may underutilize his or her social

networks to identify and exploit career opportunities (DeFillipi & Arthur, 1994).

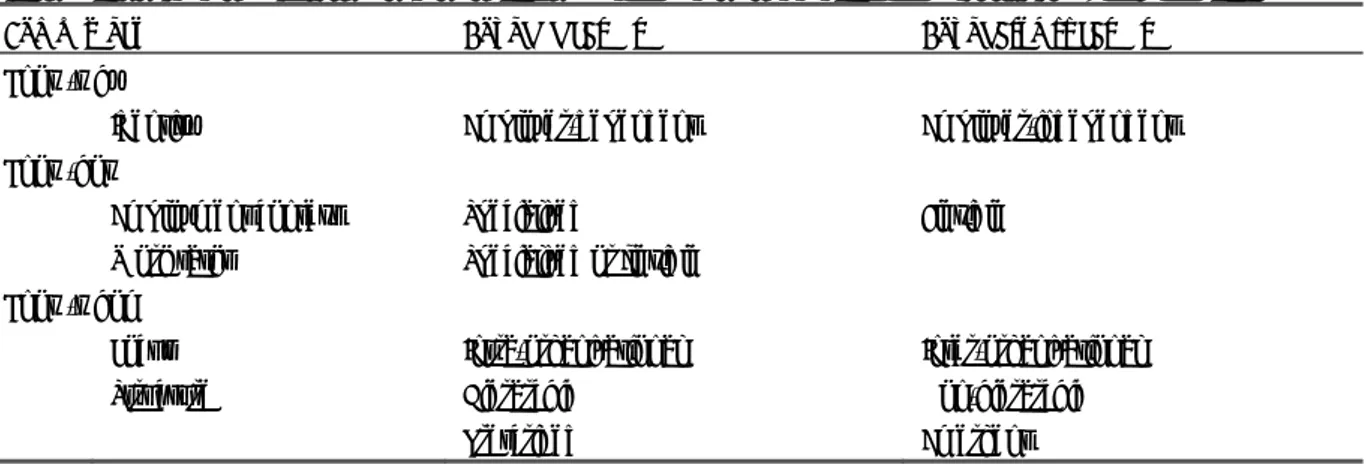

Table 2 Competency profiles of boundaryless versus bounded careers (DeFilippi & Arthur, 1994)

Competency Bounded career Boundaryless career

Know-why

Identity Employer-dependent Employer-independent

Know-how

Employment context Specialized Flexible

Work tasks Specialized or flexible Know-whom

Locus Intra-organizational Inter-organizational

Structure Hierarchic Non-hierarchic

Prescribed Emergent

In response to calls for greater clarity and further conceptualization of the boundaryless career and

its distinction from the concept of the protean career, Sullivan and Arthur (2006) built a boundaryless

career model on two axes: physical and psychological mobility. Physical mobility is the actual

movement between jobs, firms, and countries. Psychological mobility is ‘the capacity to move as

seen through the mind of the career actor’ (Sullivan and Arthur, 2006: p. 21) and more difficult to

measure. One example of crossing psychological boundaries could be behaving against the odds by

refusing promotion to spend more time with one’s family (Sullivan and Arthur, 2006: p. 21). Similarly,

Briscoe, Hall, and Frautschy DeMuth (2006) and Briscoe et al. (2012) speak of a ‘boundaryless

mindset’, being able to explore opportunities and relationships.

Briscoe and Hall (2006) acknowledge that the reality of work life experiences cannot be dichotomized

simplistically by career metaphors, being one as ‘boundaryless’ or not, or ‘protean’ or not, and that

more sophisticated constructs are needed to capture the diversity of today’s careers. Moreover,

recent studies indicate that although the two concepts have been used almost synonymously,

boundaryless and protean careers or orientations are distinct concepts. Workers can exhibit various

characteristics of the protean career while at the same time not exhibiting characteristics of the

boundaryless mindset (Briscoe and Hall, 2006). Furthermore, Vansteenkiste, Verbruggen, and Sels

(2013) warned that career attitudes or competences, for example psychological mobility, do not

necessarily associate with positive career outcomes in every context or subpopulation. They also

point to the necessity of taking structure and not only agency factors into account to fully grasp

career outcomes. In other words, the protean career attitude (value-driven and self-directed career

management) and the boundaryless mindset (mobility) are likely not enough to explain career

success in every context. Other career competences explicitly mentioned by DeFilippi and Arthur

(1994), such as knowing-who and knowing-how, as well as other (structural) factors need to be taken

into account to explain the chance to get a job and attain career success (cf. Forrier & Sels, 2003).

Although both metaphors increased in popularity among researchers during the last decade,

research on the development of career competences and the impact of career competences on

career outcomes is still in its infancy.

1.3 Policy makers’ response to the new career era

Although research on career competences in the new career era is in its infancy, policy makers,

educators, and employers worldwide have discussed and developed since the 1980s a set of

competences essential to workers’ effective participation in work, but also to adult life more

generally (Australian Education Council, Mayer Committee, 1992; OECD, 2013; Williams, 2005). To

address those competences, various terms have been used across countries with a varying degree of

emphasis on employment-related and socially relevant skills (NCVER, 2003; see table 3). In Australia,

the Mayer Committee report (Australian Education Council, Mayer Committee, 1992) had a large

impact on the establishment of key competences for the workforce and educational policy

(Cushnahan & Tafe, 2009; NCVER, 2003; Williams, 2005). Similar developments occurred in the 1990s

in the United Kingdom and the United States (NCVER, 2003; Turner, 2002; Williams, 2005). In the

United Kingdom, the Key Skills National Qualification was developed, and in the United States the

Secretary’s Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills (SCANS) Project was launched, including

workforce participation as well as personal fulfillment and community involvement objectives

(NCVER 2003; OECD, 2013). In addition, the OECD established the Definition and Selection of

Competencies (DeSeCo) project, involving academics as well as experts, in 1998 (Williams, 2005). The

project classified the competences necessary in the changing environment in three broad categories:

(1) use tools interactively (e.g. language, technology); (2) interact in heterogeneous groups; and (3)

act autonomously (OECD, 2005). The National Center for Vocational Education Research in Australia

summarized the features of the various definitions applied in schemes of skills necessary for work life

and adult life in general and concluded that many schemes include a wide variety of skills, such as

basic skills, people-related skills, and conceptual skills (NCVER, 2003; see table 4). After this

publication of NCVER (2003) of common features, new frameworks have been continuously

published by policy makers covering similar competences for similar purposes (DEEWR, 2012;

European Commission, 2007; cf. OECD, 2013).

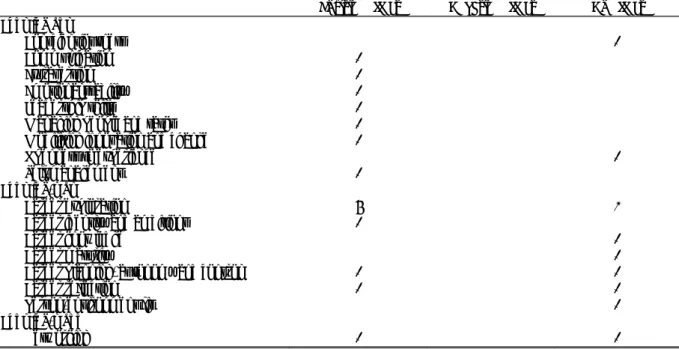

Table 3 Terms used in various countries to describe employment related and socially relevant skills

(NCVER, 2003)

Country Skills

United Kingdom Core skills, key skills, common skills New Zealand Essential skills

Australia Key competencies, employability skills, generic skills

Canada Employability skills

United States Basic skills, necessary skills, workplace know-how Singapore Critical enabling skills

France Transferable skills

Germany Key qualifications

Switzerland Trans-disciplinary goals

Denmark Process independent qualifications

Table 4 Common features of the various listings of skills (NCVER, 2003)

Common features of various listings of ‘generic’ skills

Basic/fundamental skills: e.g. literacy, using numbers, using technology

People-related skills: e.g. communication, interpersonal, teamwork, customer-service skills

Conceptual/thinking skills: e.g. collecting and organising information, problem-solving, planning and organising, learning-to-learn skills, thinking innovatively and creatively, systems thinking

Personal skills and attributes: e.g. being responsible, resourceful, flexible, able to manage own time, having self-esteem Skills related to the business world: e.g. innovation skills, enterprise skills

Skills related to the community: e.g. civic or citizenship knowledge and skills

At first glance the common features defined by the National Center for Vocational Education

Research (NCVER, 2003) for skills necessary for work life in the new career era and adult life in

general do not look like the career competences mentioned in the career theories of the protean and

boundaryless careers. Moreover, it is not clear which skills are (exclusively) related to employment

and which skills are (exclusively) socially relevant. However, it is reasonable to argue that many of

these features are implicitly implied by the previously mentioned career competences. For example,

one can reason that people-related skills are necessary to develop and sustain networks, whereas

personal skills such as self-management and flexibility are necessary to realize self-directedness and

mobility. In this way, it is reasonable to argue that this list of ‘generic’ skills and the previously

defined career competences in part overlap.

1.4 Research questions

Research on the development of career competences and the impact of career competences on

career outcomes is still in its infancy. The previously discussed studies indicate that there is a need to

consider more in depth what career competences are. For now, it seems not realistic to narrow

competences which are necessary to develop a successful career path in the new career era to a

protean attitude or a boundaryless mindset. The National Center for Vocational Education Research

(NCVER, 2003) summarized additional competences that are necessary for work-life and adult life

according to policymakers, but it is not clear whether the competences in their list are all equally

important for work life in particular. In addition, some researchers argue that career competences

vary according to work context, cultural context, and subpopulations (Briscoe & Hall, 2006; Duberley

& Cohen, 2010; Eby, Butts & Lockwood, 2003; Vansteenkiste, Verbruggen & Sels, 2013). These

observations reflect the need to define more explicitly what sorts of competences are necessary to

attain career success (in different contexts). Moreover, when defining career competences and their

impact on career outcomes, it is necessary to expand the scope of outcome measurements beyond

subjective career success indicators. Psychological success, i.e. subjective career success, is

considered to be the most important outcome of the protean or boundaryless career (cf. Arthur,

Khapova & Wilderom, 2005), but other career success indicators, i.e. objective career success

indicators, are important too. A protean attitude or a boundaryless mindset, and other career

competences, may help the individual to engage in certain behaviors that result in positive work

outcomes (cf. Briscoe et al., 2012; Vansteenkiste, Verbruggen & Sels, 2013). Getting a job, the quality

of the job, and sustaining employment in changing environments are too important indicators of

career success from policymakers’ perspective.

Besides the question what competences exactly are necessary to get a job, to sustain employment

and to attain career satisfaction in a changing environment, the question how these competences

are developed needs to be raised. According to Briscoe et al. (2012) the protean attitude and

boundaryless mindset can be taught and learned. But how are these and other relevant career

competences being developed? Does lifelong learning, on the initiative of the individual, or organized

by the employer, influence career competences development? Is there evidence of structural factors

influencing the development of career competences? And do these competences have a different

impact dependent on the career outcome taken into consideration? In sum, the following research

questions are raised:

(1) What sorts of competences are necessary for one’s work life or career according to the research

literature? How are these career competences being defined?

(2) What factors influence the acquirement of career competences? Does lifelong learning stimulate

the development of career competences?

(3) What impact do career competences have on career outcomes?

(4) Do structural factors influence the relationship between career competences, lifelong learning,

and career outcomes?

(5) Which (inter)national databases enable quantitative and cross-national comparative research into

the development and impact of career competences?

1.5 Research methodology

The research questions are answered by means of an in-depth analysis and review of empirical

studies on competences relevant for one’s work life or career. We used numerous keywords to find

studies relevant to our research in two consequent phases. The aim of the first phase was to find

studies that clarified which competences are necessary for work-life in various disciplines and

industries. A large number of studies found in this first phase do not only describe the necessary

career competences, but also studied the factors influencing the acquirement and use of career

competences and the impact of career competences. The aim of the second phase was to find

additional studies on the explanatory factors and impact of career competences by focusing on

specific competences found in the first phase and by using other labels that appeared to be

associated with career competences.

During the first phase, we used the obvious keyword ‘career competences’ to find literature on

competences relevant for one’s work life or career, but also career development competences,

employability competences, vocational competences, professional competences, occupational

competences, work-related competences, workplace competences, work competences, job-related

competences, job competences, work-based competences, job-based competences, and career

capital. In addition, the keyword ‘competences’ was also substituted by the keywords ‘competence’,’

competency’, ‘competencies’, and ‘skills’.

1We decided not to limit our search to the keyword ‘career

competences’, because we assumed that many other studies might exist dealing with competences

necessary for one’s career but labeling these competences differently.

During the second phase, we used terms and labels that emerged from the first phase reflecting the

various competences relevant for one’s career and other keywords such as boundaryless career,

generic skills, etc.

2in combination with the following keywords: effect, affect, impact, influence,

determinant, factor, learning, training, adult education, career, employability, review, and

meta-analysis. The last two keywords were used to reduce the number of records, when a particular

competence appeared to have been studied extensively already and many systematic reviews

3exist

with regard to that competence. This was especially the case when using ERIC and in the case of

keywords such as creativity, communication skills, mentoring, etc.

The keywords were applied in two databases: ERIC and Web of Knowledge. We used no time

constraint with regard to the starting point and searched for relevant literature until mid-2013. In the

1 We did not use all terms listed in table 3 in the first phase, because many of these terms can also be used for issues related to adult life in general. Using terms such as ‘key competencies’ without any combinations with other keywords in the first phase would result into a large bulk of literature not necessarily relevant to the definition of competences necessary for one’s career in particular. We did use these terms in the second phase in combinations with other keywords to decrease the number of irrelevant references.

2 With NVIVO we checked how often particular competences and items appeared in the long list of competences as a result of the first phase of our search process (see table b1.1.1., annexe 1) and to what extent similar competences could be grouped into one category as they appeared to be synonymous. In this way, we limited the number of potential new keywords to be used in the second phase. This method helped us to be efficient in terms of time-management, but as a result we cannot claim that our literature review is exhaustive. The keywords we used in the second phase are: ability to learn, (career) adaptability, agentic capital, ambition, analytical skills, analytical thinking, basic skills, boundaryless career, business skills, career actualization, career advancement skills, career control, career exploration, career goal (setting), career identity, career identification, career insight, career management, career motivation, career planning, career reflection, career (sector) knowledge, career strategy, collaboration, collaborative (skills), common skills, communication skills, computer literacy, computing skills, conceptual thinking, conscientiousness, core skills, creative (thinking), critical thinking, cultural capital, decision making, domestic capital, economic capital, emotional intelligence, enthusiasm, entrepreneurial skills, essential skills, expert capital, expertise, general skills, generic skills, group working skills, hard skills, higher order thinking skills, human capital, human relations, information literacy, information technology skills, initiative, interactive skills, interpersonal skills, job autonomy, job basics, job complexity, job knowledge, job preparation, key competences, knowing-how, knowing-whom, knowing-why, leadership skills, literacy skills, management skills, manual skills, math skills, mentor, modern career, new career, physical mobility, psychological mobility, network capital, networking abilities/skills, numeracy skills, organizational skills, personal qualities, skills, characteristics or traits, (person-environment or person-job) fit, political skills, post-corporate career, problem-solving skills, protean career, reading skills, reflection, reflective thinking, responsibility, confidence, directedness, self-management, self-planning, self-regulated learning, social capital, social relations, social skills, soft skills, team-building, team work skills, technical skills, time management skills, transferable skills, transitional career, verbal skills, work ethic, work exploration, work habits, and writing skills.

3 We only took systematic reviews or meta-analyses into account. A few reviews were found but were not the result of a systematic procedure. In that case, we excluded these studies form our own review process.

first phase, we also checked the databases PsycINFO and EconLit, but we concluded that these

databases do not introduce a significant amount of studies not being covered by ERIC and Web of

Knowledge. In contrast, Web of Knowledge and ERIC each produced a distinctive set of references.

The following selection criteria were used to decide whether papers and study reports are relevant:

(1) the studies are accessible for the international audience and peer-reviewed; (2) the studies are

written completely in English; (3) the studies define competences relevant for one’s work life or

investigate the determinants or impact of career competences on the basis of empirical methods; (4)

the studies focus on secondary or vocational education, tertiary education, and adult education

when transition from education to labor market becomes relevant. In other words, we excluded

studies that focused on preschool, primary, and to some extent middle school children, because

issues of transition to the labor market and career guidance become only relevant from the end of

lower secondary education on. In addition, we preferred not to interfere with the large bulk of

research literature on learning achievement of school children that happens at the primary and

secondary school level, not directly relevant to our primary research goals. We also excluded studies

conducted in very specific contexts, for example among people with severe disabilities or in remote

areas. Furthermore, we decided that the studies needed to be based on empirical methods.

Therefore, we excluded opinion papers. Eighty seven studies or papers were selected from

approximately 1280 records originally produced in the first phase and 132 papers from

approximately 40000 records produced in the second phase. Although originally many records

appeared on the basis of our selected combinations of keywords, we do not claim that our search

results in the second phase are exhaustive. Due to time constraints we refrained from using

synonyms of the chosen keywords as much as possible. Using as many synonyms as possible for each

competence would result into a literature review for each competence separately, which proved to

be too ambitious and is beyond the scope of our research objectives. In addition, we did not explicitly

search for evidence of the impact and determinants of lifelong learning activities in the second phase

of our research. As will be seen in chapter 2, controlling one’s learning actions and participation in

lifelong learning to pursue one’s career is an important career competence. However, we already

performed several studies on the determinants and effects of various lifelong learning activities,

including one review (Knipprath & De Rick, 2011a, 2011b; Knipprath & De Rick, 2012). We will briefly

refer to the research results in previous studies in chapter 7. In addition, we did not apply a snowball

method to search for additional references, because we concluded that the added value of additional

records found through this method would be moderate considering the time needed to screen those

additional records. The studies that were chosen to be reviewed in this report, are presented in

annex A.

2. What are career competences?

2.1 Introduction

The objective of the first phase of our research was to find studies that clarify which competences

(i.e. a set of skills, attitudes, and knowledge) are necessary for work life. Eighty studies were found.

Below we describe the characteristics of the studies found in the first phase and the competences

that were most frequently mentioned (section 2.2). In section 2.3 we integrate our findings within

the framework of DeFilippi and Arthur (1994).

2.2 The career competences literature

In table 5, the number of the studies retained in the first phase of the research literature review

study and the labels being used in the literature are presented. Thirteen studies were found to be

using the term ‘career competences’ literally. However, researchers use other names too to study

competences necessary for one’s career. Professional competences, employability skills, career

capital, and job skills or job competences have been mentioned in multiple studies. Most studies are

conducted after the 1980’s (figure 1), in particular since the start of the 21

stcentury. And the number

of studies seems to continue to rise. The studies deal with competences for specific occupations,

including teachers, engineers, managers, caretakers, physicians, lodging and food service jobs,

personnel directors, school administrators, information system jobs, call center jobs, librarians, etc.,

or cover a variety of occupations (see also appendix A, table B1.1.1). Twenty three studies describe

career competences on the basis of a survey, literature review study and/or expert groups. The

remaining sixty five studies describe career competences, but also study factors related to career

competences. These studies are mostly quantitative in nature.

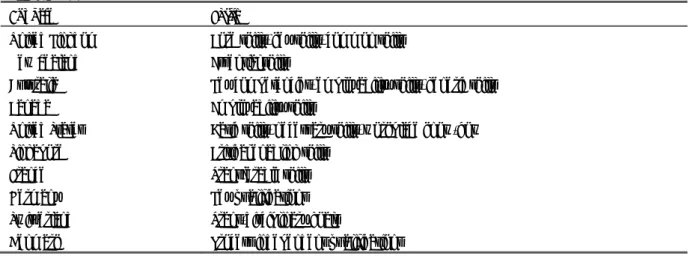

Table 5 Number of studies focusing on career-related competences and the various labels being used

to identify career-related competences

Frequency Professional competences 15 Career competences 14 Employability skills 12 Job skills 10 Professional skills 6 Career capital 5 Job competences 4 Workplace skills 3 Work skills 2 Workplace competences 2 Work-related skills 2 Vocational competences 2

Career development skills 2

Work-related competences 1

Work competences 1

Vocational skills 1

Professional and career development skills 1

Occupational skills 1

Job or workplace skills 1

Employability or job-related skills 1

Work-based competences 1

Figure 1 Number of empirical studies found on competences relevant for one’s work-life on a time

line

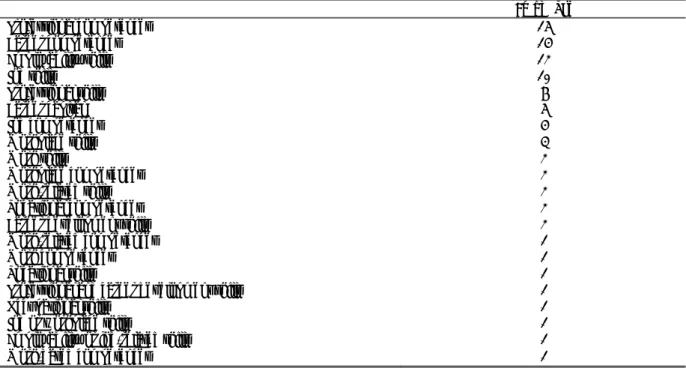

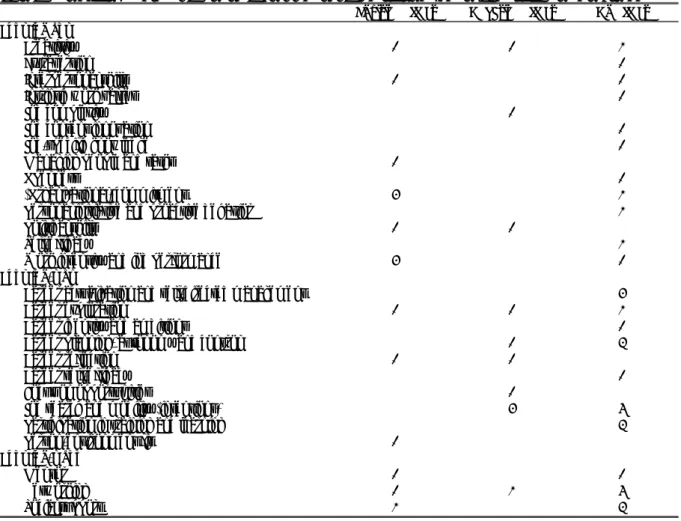

Table 6 gives an overview of the competences most frequently linked by researchers to work-life.

The number represents the number of studies that mention these competences. Competences

mentioned in less than two studies are being excluded. The competences are neither exhaustive nor

exclusive. There is for example a considerable overlap between the three knowing-dimensions of

DeFilippi and Arthur (1994), knowing-how, knowing-why, and knowing-whom, on one side, and other

competences on the other side. Moreover, some studies measure competences by items that are

attributed by other studies to other competences. For example, one study considers ‘finding support’

a characteristic of interpersonal relationships (Hackett, Betz & Doty, 1985), whereas another study

treats this trait as a characteristic of domestic capital or knowing-whom (Duberley & Cohen, 2010). In

other words, table 6 gives only a rough but interesting picture of what sorts of competences are

necessary to one’s work–life according to the literature.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

Table 6 Number of studies that mention particular competences

Competences Frequency

Set of various attitudes, skills, and knowledge relevant to work-life 33

Occupation-specific skills and knowledge 31

Communication skills 18

Interpersonal understanding or social skills 15

Problem-solving skills 14

Career development skills 12

Management and organizational skills 11

Basic work attitudes (e.g. responsibility, flexibility, work independently, commitment) 10

Networking and use of mentor 10

Knowing-why 9

Knowing-how 9

Knowing-whom 9

Collaboration and teamwork 9

Higher-order thinking skills 7

Leadership and initiative 7

Numeracy skills 7

Information technology 6

Career reflection 6

Human capital: education and work experience 5

Manual skills 4

General business skills 4

Career control/management 4

Decision-making skills 3

Ability to learn 3

Career insight and sector knowledge 3

Fit between job and environment 3

Goal-setting 2

Developing/mentoring others 2

Based on table 6, we can group the competences found in the literature into four categories. Firstly,

occupation-specific skills or technical know-how necessary for particular occupations are frequently

mentioned. Various professions including information system specialists, global managers, personnel

directors, engineers, social workers, teachers, women scientists, nurses, etc. were subject of these

studies to define technical (and other) skills (e.g. De Juanas Oliva et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2010;

Russinova et al., 2011). Secondly, a large group of dimensions reflect competences that are more

likely to be applicable across various occupations such as communication skills, numeracy, teamwork,

problem-solving skills, work attitudes, etc. (e.g. Barker, 2000; Hämeen-Anttila, Saano & Vainio, 2010).

These competences reflect the generic skills found in many policy documents relevant for one’s

work-life and adult life in general (see table 4 in chapter 1). Thirdly, a considerable amount of studies

mentions competences important to manage one’s career: career development, career reflection,

but also networking, and the three knowing’s (e.g. Cappellen & Janssens, 2008; Kong, Cheung &

Song, 2012a, 2012b; Kuijpers & Meijers, 2012). Finally, 33 studies belong to the category ‘Set of

various attitudes, skills, and knowledge relevant to work-life’. These studies are grouped into this

category, because they mention competences that overlap with two or more competences

mentioned elsewhere in table 6. For example, some studies group various skills together such as

cooperation, communication skills, leadership skills, flexibility, time-management, etc. into one

competence (e.g. Miller & Miller, 1971; Paranto & Kelkar, 2000; Rainsbury et al. 2002), whereas

many other studies treat these competences separately (e.g. Cairns, 1996; Green, 2012; Hassall et al.,

2003). Other studies only mention a list of items without attempting to categorize them into clearly

defined competences (e.g. Barker, 2000; Hämeen-Anttila, Saano & Vainio, 2010). These studies were

also attributed to the category ‘set of various attitudes, skills, and knowledge’.

2.3 Establishing a framework by integrating the competences

and the three knowing’s

Based on the literature review study we have identified a variety of competences relevant for one’s

work life or career (table 6). Nine studies (e.g. Cappellen & Janssens; Kong, Cheung & Song, 2012a,

2012b) use explicitly the framework of DeFilippi and Arthur (1994) to define career competences.

Other studies do not use the framework explicitly, but mention competences that can be directly

linked to the framework of the three knowing’s, such as networking (knowing-whom), career

reflection (knowing-why), and various skills or human capital acquired through education and

experience (knowing-how). In order to create structure in a long list of career-related competences

and to produce a conceptual framework useful for studying the determinants and impact of career

competences (development) later on, we use the three knowing’s of DeFilipi and Arhthur (1994). The

three knowing’s were originally broadly defined by their authors (see chapter 1). In table 7, we

present more explicitly the various competences that can be attributed to the three knowing’s,

based on our findings.

Table 7 Three knowing-dimensions and related career competences

Dimensions and competency groups

Specific competences

Knowing-how

Occupation-related competences Occupation-specific competences Generic competences

Cognitive competences Communication skills

Mathematical competences

Higher-order thinking skills including problem-solving skills Ability and willingness to learn

Technological competences Use of technologies, in particular ICT Interpersonal competences Team-work and collaboration

Sensitive to others’ culture, values, and interests and to be able to influence others Intrapersonal competences Self-control, self-confidence, commitment, reflexivity, adaptability, and openness

to experiences

Management and organizational skills

Entrepreneurial mindset (decision-making, initiative, innovative)

Knowing-why Career reflection and identity

Career exploration and action

Knowing-whom

Networking

Professional Inter-firm networks including mentoring Other professional networks

Personal Support within the family Support outside the family