EFFECTS OF EUROPEAN BANK

BAIL-INS

EVENT STUDY ANAYLSIS

Aantal woorden/ Word count: 15.776Alex Nollet

Studentennummer/ Student number : 01503322

Promotor/ Supervisor: Prof. dr. Rudi Vander Vennet Commissioner: Nicolas Soenen

Masterproef voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van: Master’s Dissertation submitted to obtain the degree of:

Master of Science in Business Engineering: Finance

Deze pagina is niet beschikbaar omdat ze persoonsgegevens bevat.

Universiteitsbibliotheek Gent, 2021.

This page is not available because it contains personal information.

Ghent University, Library, 2021.

Foreword

This dissertation marks the final step of my five years studying at Ghent University. This dissertation analyses how stock returns and CDS spread changes of European banks reacted to five different resolution cases during the 2013-2017 period. It focuses on how markets reacted to the switch from bailout to bail-in, while also addressing possible contagion effects. Furthermore, an attempt is made to uncover the drivers of these reactions. The COVID-19 measures did not affect this thesis.

During the process of writing this dissertation, I gained new insights into financial mar-kets and the banking sector. Furthermore, it was the first experience of doing my own research, which has taught me many new things. This challenge of writing this disserta-tion could not have been successfully completed without the help of some people. For this reason, I would like to take the time to express my gratitude towards those people.

First, I would like to thank my promotor, Rudi Vander Vennet. His enthusiastic style of teaching filled with relevant news articles fed my interest in financial markets and the financial system. Furthermore, he gave me the opportunity to conduct research in this field.

Second, I would like to thank Nicolas Soenen. His guidance was critical to the success of this dissertation. Despite the circumstances, he was readily available to discuss and steer my efforts in the right direction.

Next up, I would like to thank the other professors and the supporting staff of Ghent University. Over the course of five years, they have provided me with many valuable memories and insights.

Finally, I would like to thank my parents and friends for supporting me along the way.

Alex Nollet May 2020

Contents

1 Introduction 1

2 BRRD in a nutshell 2

2.1 Implementation of the BRRD . . . 2

2.2 Recovery and resolution . . . 3

2.3 Tools and powers of the resolution authority . . . 3

3 Literature review 6 3.1 The positive and negative effects of bailing out banks . . . 6

3.2 The positive and negative effects of bailing in banks . . . 10

3.3 Market discipline and its effects on financial instruments . . . 13

4 Events 15 4.1 Netherlands: SNS Reaal . . . 16

4.2 Cyprus: Laiki . . . 17

4.3 Portugal: Espirito Santo . . . 18

4.4 Spain: Banco Popular . . . 18

4.5 Italy: Monte Paschi Di Siena . . . 19

5 Data 20 5.1 CDS data . . . 20

5.2 Stock data . . . 22

5.3 Bank specific characteristics . . . 23

6 Methodology 24 6.1 Event study methodology . . . 26

7 Results 31

7.1 SNS REAAL . . . 31

7.2 Cyprus: Laiki bank . . . 34

7.3 Banco Espirito Santo . . . 35

7.4 Banco Popular . . . 37

7.5 Banco Monte Dei Paschi di Siena . . . 38

8 Conclusion 40 A Appendix 46 A.1 CDS spread changes distribution . . . 46

A.2 Stock returns distribution . . . 46

A.3 CDS Spread SCAR . . . 46

A.4 Stock returns SCAR . . . 54

List of abbreviations

AMV Asset Management Vehicle AR Abnormal return

EBA European Banking Authority ECB European Central Bank BES Banco Espirito Santo

BRRD Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive CAR Cumulative abnormal return

CDS Credit default swap CET1 Common Equity Tier 1 FSB Financial Stability Board GDP Gross domestic product

GIIPS Greece, Italy, Ireland, Portugal and Spain

G-SIFI Globally Systematically Important Financial Institutions MPS Banco Monte dei Paschi di Siena

NR Normal Returns

OLS Ordinary Least Square PONV Point of non-viability RA Resolution Authority ROE Return on equity

SRM Single Resolution Mechanism SSM Single Supervisory Mechanism TBTF Too-Big-To-Fail

List of Figures

2.1 bail-in procedure . . . 5

3.1 Doomloop . . . 9

5.1 CDS Spread changes distributions . . . 21

List of Tables

5.1 Bank Specific Characteristics 2013 . . . 25

5.2 Bank Specific Characteristics 2014 . . . 25

5.3 Bank Specific Characteristics 2017 . . . 25

7.1 Stock reactions SNS Reaal: t-values . . . 32

7.2 CDS reactions SNS Reaal: t-values . . . 33

7.3 Stock reactions Laiki: t-values . . . 34

7.4 CDS reactions Laiki: t-values . . . 35

7.5 Stock reactions BES: t-values . . . 36

7.6 CDS reactions BES: t-values . . . 36

7.7 Stock reactions Banco Popular: t-values . . . 37

7.8 CDS reactions Banco Popular: t-values . . . 38

7.9 Stock reactions MPS: t-values . . . 39

7.10 CDS reaction MPS: t-values . . . 40

A.1 SNS Reaal: individual CDS SCAR test . . . 46

A.2 Event Laiki: individual CDS SCAR test . . . 48

A.3 Event Banco Espirito Santo: individual CDS SCAR test . . . 49

A.4 Event Banco Popular: individual CDS SCAR test . . . 51

A.5 Event Monte dei Paschi di Siena: individual CDS SCAR test . . . 53

A.6 Event SNS Reaal: individual Stock SCAR test . . . 55

A.7 Event Laiki: individual Stock SCAR test . . . 56

A.8 Event BES: individual Stock SCAR test . . . 58

A.9 Event Banco Popular: individual Stock SCAR test . . . 60

A.10 Event MPS: individual Stock SCAR test . . . 62

A.11 SNS Reaal | Full-Sample | [-5;+5] . . . 66

A.13 SNS Reaal | Full-Sample | [-1;+1] . . . 68

A.14 SNS Reaal | Full-Sample | [0] . . . 69

A.15 Laiki | Full-Sample | [-5;+5] . . . 70

A.16 Laiki | Full-Sample | [-2;+2] . . . 71

A.17 Laiki | Full-Sample | [-1;+1] . . . 72

A.18 Laiki | Full-Sample | [0] . . . 73

A.19 Banco Espirito Santo | Full-Sample | [-5;+5] . . . 74

A.20 Banco Espirito Santo | Full-Sample | [-2;+2] . . . 75

A.21 Banco Espirito Santo | Full-Sample | [-1;+1] . . . 76

A.22 Banco Espirito Santo | Full-Sample | [0] . . . 77

A.23 Banco Popular | Full-Sample | [-5;+5] . . . 78

A.24 Banco Popular | Full-Sample | [-2;+2] . . . 79

A.25 Banco Popular | Full-Sample | [-1;+1] . . . 80

A.26 Banco Popular | Full-Sample | [0] . . . 81

A.27 Monte dei Paschi di Siena | Full-Sample | [-5;+5] . . . 82

A.28 Monte dei Paschi di Siena | Full-Sample | [-2;+2] . . . 83

A.29 Monte dei Paschi di Siena | Full-Sample | [-1;+1] . . . 84

1

Introduction

During the financial crisis, one acronym gained a lot of attention, TBTF, or Too-Big-To-Fail. The idea that some banks are so interconnected with the financial system that a possible bankruptcy of these banks could endanger the whole financial system. This threat could in turn have devastating effects on the real economy. To avoid these neg-ative effects governments intervened by using taxpayers’ money to bailout these TBTF banks. In the financial crisis, every European country bailed out banks, and some banks were even completely nationalized [Lintner et al., 2016]. This restored confidence in the financial system, but at a high cost. Sovereign debt rose significantly, hampering fiscal policy leeway in these countries. The most extreme case of this problem was Ireland, where debt to GDP rose from 23,9% to 119,9% between 2007 and 2012. These sharp rises in government debt could then, in turn, raise doubt about the repayments and re-financing of this debt. Interest rates spiked, which in turn weakened balances of banks who held a large proportion of their home country’s sovereign debt. This feedback loop was later coined the doom-loop because of its dangerous effects. This TBTF problem and the solution of bailing out these institutions have perverse effects. A study by [Völz and Wedow, 2011] found that implicit government guarantees caused a negative rela-tion between CDS-spread (a risk measure) and the size of financial institurela-tions. This cheaper funding creates an incentive for banks to become systematically important. During a crisis, these banks would need to be bailed out because of their TBTF status. When banks become too large they often take on more risk. This increased risk taking is called Moral Hazard, banks have the wrong incentives and if something goes wrong, someone else, the government, will pay. To avoid these problems of TBTF and moral hazard new regulation was set in place to avoid these bail-outs and the taxpayers rage it caused.

A new regulation was designed to avoid the problems of TBTF, Moral Hazard, and the feedback loop between sovereigns and financial institutions. In Europe, the crisis had shown that national supervision could not cope with the complications of complex cross-border institutions. Therefore a banking union was designed at the European level. Supervisions for large financial institutions would be covered by the ECB under the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM). The resolution and recovery of banks would be dealt with by the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) and the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD). The final pillar of the European banking union, a deposit guarantee scheme, is still not agreed upon.

This thesis will focus on the BRRD its effects on financial markets. More specifically the effects of the new bail-in mechanism. Are the problems of bail outs resolved by the new regulation? How do banks that are systemically important react to this new regulation? Have the implicit government guarantees been removed or lowered? Have Moral Haz-ard problems been addressed? What are the effects during a bail-in procedure on the bank’s CDS spread and its stock market return? More importantly are there contagion effects in place that threaten financial stability? To answer these questions, five cases will be examined by using an event study methodology.

The thesis is structured as follows: in section 3 the most important aspects of the BRRD will be explained. This should give more insight into the objectives of the new regulation. In section 4 the literature on this topic will be explored. The expectations of the new regulation and the studies which have already been done will be reviewed. Section 4 will give an overview of the cases that will be analysed. Furthermore, predictions will be made about the effects of the different cases. In section 5 the data used in this thesis will be discussed. Section 6 the methodology of this thesis is explained. Section 7 will discuss the results of the research. Finally, section 8 will conclude this dissertation.

2

BRRD in a nutshell

In this section, a brief overview will be given about the aspects of the Bank Resolution and Recovery Directive that are relevant to the scope of this dissertation. Firstly the implementation of the BRRD will be discussed. Secondly, the difference between re-covery and resolution will be explained. Afterwards, an overview of the main tools and powers that the resolution authority has at its disposal will be given.

2.1

Implementation of the BRRD

The BRRD is broadly based on the key principles of the FSB. Which is usually seen as the gold standard for resolution regimes[Coleman et al., 2018]. The key principles described 12 attributes that future resolution regimes should have in order to ensure an effective resolution of banks, without threatening the critical functions of the banks, and without the use of taxpayer’s money. However, the text still leaves an opening for public support as a last resort to ensure financial stability. It is stressed that this should be a temporary solution [Financial Stability Board, 2014]. The key principles were also the basis for other resolution regimes in the world, including the resolution mechanism of the USA [Avgouleas and Goodhart, 2015].

These key principles were transformed into European law through the BRRD. The di-rective was signed on 15 May 2014 by the European Parliament and the European Council [The European Parliament and The Council, 2014]. It is important to note that the definition of a directive entails that the BRRD still needed to be converted into the national law of the European member states. The BRRD is only a minimum set of requirements. National lawmakers could go beyond these rules, which could create di-vergences between member states [Coleman et al., 2018]. In this thesis, we won’t take these possible divergences into account because it is outside of the scope. It should be noted that these differences could be significant and further research should look into these discrepancies and their possible effects. The scope of the BRRD covers all EU credit institutions and large investment firms, EU based parent and intermediate finan-cial holding companies, and subsidiaries of EU parent credit institutions or investment firms of financial holding companies [Lintner et al., 2016]. This implies that BRRD’s scope reaches beyond the borders of the EU, which creates cross-jurisdictions issues. These were later addressed by amendments to the BRRD.

2.2

Recovery and resolution

An important concept, concerning the BRRD, is the distinction between the recovery of a bank and the resolution of a bank. The recovery is defined as the period when the going-concern principle still applies. The bank can still carry on its business, but should take steps to improve its financial conditions and return to “business-as-usual”. These steps are discussed in a recovery plan, that has been drawn up by the financial institution before problems occur. This plan needs to be approved by the supervisor. Many banks have been recovered during the 2008-2017 period. However, this thesis wants to make an inquiry about the effects of the bail-in mechanism, which is a power granted to the resolution authority (RA). Therefore the topic of recovery and its effect will not be analysed in this thesis.

2.3

Tools and powers of the resolution authority

The resolution of banks is the period after the point of non-viability (PONV), where a recovery is no longer an option. After this point, the resolution authority takes control and draws up a resolution plan and exercise it. To trigger the resolution of a firm by the relevant authorities, 3 conditions need to be met.

1. The bank should be deemed likely to fail (without the prospect of improvement) or failing.

2. No private solution is available

3. The resolution is in the public interest.

A thorough explanation of these criteria can be found in [Lintner et al., 2016]. When the PONV is triggered, the Resolution Authority obtains the power to execute a resolution plan, so it can orderly resolve the financial institution. For this successful resolution, the BRRD foresees five tools that the RA can use in its resolution plan.

1. Sale of business

2. Bridge bank

3. Asset separation

4. Bail-in

5. Government stabilisation

The first three tools are called transfer tools. The Sale of Business tool gives the RA the power to sell shares, assets, rights, or liabilities of the firm under resolution. This is normally the quickest and most efficient solution. The assets are transferred on com-mercial terms, which means the going-concern principle is applied. However, the RA only has limited time to find the right buyers. The bridge bank tool creates a new legal entity (often called the good bank) and transfers the “good” assets and liabilities to this bank. This ensures that the critical functions can be executed while the bank is being resolved. This newly created bank is controlled by the RA for a period of two years. Dur-ing this period a private solution must be searched for. This could be a the sale of the whole bank or parts. Residual parts should be wound down under normal insolvency procedures. The last transfer tool, the asset separation tool, can transfer ”bad” assets, rights, and liabilities to a temporary asset management vehicle (AMV). This tool does not safeguard the critical functions, therefore, it should be used in combination with the sale of business, bridge bank or bail-in tool. This tool allows that parts of the bank in trouble can be wound down in an organized way. Furthermore, this AMV allows the RA to buy time and sell assets when conditions improve. These tools have all been used during the financial crisis. The bail-in tool, however, is the new tool that Resolu-tion Authorities can use. This tool is the main tool to prevent bailouts and its negative effects. It gives the RA the power to convert certain liabilities into equity or writing down the principal amount of the liabilities. This ensures that the capital buffer requirements of Basel III are met. All liabilities that are not excluded specifically from the bail-in pro-cedure can be converted or written down. Uncovered deposits can also be bailed-in. Only covered deposits are excluded. However, in exceptional circumstances, the RA

can exclude other liabilities that were not specifically excluded in the BRRD. To decide which liabilities are bailed in first, a hierarchical structure was defined. Firstly, equities are bailed-in. If these instruments are not sufficient to restore the capital buffers subor-dinated debt can be bailed-in. If more capital is needed unsecured senior debt can also be bailed-in. Finally, if extra capital is still needed unsecured deposits can be bailed-in. This process is called the bail-in waterfall. An example of this procedure can be found below.

Figure 2.1: bail-in procedure [Lintner et al., 2016]

The last tool at the RA its disposal is the government stabilisation tool. This tool is, however, a last resort and can only be applied if certain conditions are met. The goal of the BRRD is to prevent the mistakes from the 2008 financial crisis, namely bailing out financial institutions and its issues of moral hazard and TBTF. Therefore the bail-in mechanism was implemented. In exceptional circumstances, if the stability of the financial system is in danger, public money can be used to recapitalize banks. The RA can seek public finance in the form of temporary public equity support or temporary public ownership. The emphasis on temporary support and ownership should be noted.

Additionally, the RA has some general powers at its disposal when a resolution is trig-gered. The general powers are specified in Article 63 of the BRRD. These powers allow

the RA to execute the resolution plan and implement the resolution tools. Therefore they are equally important as the tools themselves [Lintner et al., 2016]. One example of a general power is that the RA can appoint a special manager to replace the manage-ment of the firm. This special manager is under the control of the RA and executes the resolution plan. Furthermore, he takes over shareholder powers. This special manager can maximum stay for one year. A full list powers is beyond the scope of this thesis but can be found in the Worldbank guidebook [Lintner et al., 2016].

3

Literature review

In this section, the literature on the effects of bail-ins versus bailouts will be discussed. This section starts by addressing the issues of moral hazard, TBTF, and the doom loop that should have been solved by the BRRD and its bail-in mechanism. Secondly, we will look into the criticism of the BRRD concerning systemic crises and other negative effects. Finally, we will look into the case studies that already have been made, con-cerning market discipline and the effects on different financial instruments.

3.1

The positive and negative effects of bailing out banks

To prevent a systemic crisis in the banking industry, governments all around the world used taxpayers’ money to recapitalize banks. These implicit government guarantees led to moral hazard problems in the banking industry [Völz and Wedow, 2011], [Av-gouleas and Goodhart, 2015],[Banque de France, 2012]. Banks had an incentive to grow their balance sheet, so they became Too-Big-To-Fail. They took excessive risks and if things eventually did go wrong governments stepped in to prevent a systemic crisis in the banking sector. Banks even became so big, some authors spoke of Too-Big-To-Rescue [Völz and Wedow, 2011]. The use of taxpayers’ money to rescue banks caused an uproar among the public and thus regulation was developed to adhere to these problems. The BRRD together with other regulations such as Basel III should incentivise investors (in a broad sense) to take risks into account when investing or borrowing money to financial institutions. This in turn, through market discipline, should incentivise banks to be more prudent in their risk-taking activities. There is evidence that this market discipline is working [Völz and Wedow, 2011], [Barth and Schnabel, 2015], [Giuliana et al., 2018], [Lewrick et al., 2019]. However, this focus on bail-in rather than bail out could threaten financial stability if too much hope is placed on this new mechanism [Dewatripont, 2014], [De Grauwe, 2013]).

hazard issues, caused by bailouts and financial instability issues, caused by bail-in. This financial instability can occur because of a fire sale of stocks from other financial institutions when there is uncertainty about the resolution of the bank in trouble. This, in turn, would hamper the bail-in of subsequent institutions because of the lower equity base that can be bailed-in. This point will be addressed more in detail later in this review. The bailout does not suffer from those issues because it allows for a swift resolution of the bank, which is seen as a positive effect for bailing out institutions.

Dewatripont further states solutions for the problems of each resolution mechanism. For the negative impacts of the bailout mechanism, moral hazard, and the use of taxpayers’ money, he states that it could be contained by punishing banks if they get bailed out by the government.[Dewatripont, 2014]. He proposes measures like, firing management and wiping out shareholders. Secondly, the financial instability that bail-ins cause could be solved by ensuring banks that have sufficiently long-term liabilities. These long-term liabilities are “stuck”, they are illiquid and cannot be sold easily. This would prevent a fire sale of these instruments and the bail-in basis of subsequent resolutions would not be affected. Therefore, contagion to other banks through a bank-run or fire sale is contained. Financial stability would not be at risk.

[?] also looks into the moral hazard issue of bailouts, but he challenges the conven-tional view that public intervention should be limited. He also points to the trade-off between financial stability and moral hazard. According to his research, the implicit government guarantees do not always induce banks to excessive risk-taking and could even increase financial stability, thus the recent focus on limiting these interventions could harm the financial system.

These views are contested by [Völz and Wedow, 2011], they found a negative corre-lation between the size of a bank and its CDS spread. More concretely they found the following result: ”A 1 percentage point increase in size reduces the CDS spread

of a bank by about 2 basis points.” This relationship could limit the market discipline

on bank’s management. Furthermore, a bank could increase its size to gain better fi-nancing options. This creates incentives for banks to become TBTF and hence be a threat to financial stability. The reason for this relationship is the implicit government guarantee for large systemic banks. [Völz and Wedow, 2011] argues that a framework for orderly resolution could limit the impact of systematically important banks. This is exactly the objective of the BRRD. The author, however, warns that a no-bailout guar-antee is not credible when bank failures threaten financial stability. This point is also made by [Avgouleas and Goodhart, 2015] and [Barth and Schnabel, 2015].

This implicit government guarantee has been researched by [Neuberg et al., 2016]. They found that the implicit probability of government intervention declined from 40% to 20%. They concluded that the implicit guarantee has fallen after the financial crisis, but remains relevant. This is in line with the BRRD’s specification of government stabi-lization tool, which allows governments to bail out banks under specific circumstances [Lintner et al., 2016]. The market is convinced that governments will step in under these circumstances. This is also in line with the point made by [Völz and Wedow, 2011],[Avgouleas and Goodhart, 2015] and [Barth and Schnabel, 2015]that a no-bail-in guarantee is not credible when financial stability is threatened.

This brings us to the next issue the BRRD tries to solve, namely the doom-loop. This process is described by [Banque de France, 2012] and [Acharya et al., 2011]. [Banque de France, 2012] argue that the doom-loop can be understood as the interplay be-tween two debt overhang problems. The first debt overhang problem is the under-capitalization of banks after the financial crisis. The second debt overhang problem is related to sovereign debt and is related to the crowding-out phenomenon. If finan-cial stability is threatened, by under-capitalized banks, governments are incentivised to step in in order to calm down markets. This happened in the 2007-2008 financial crisis, when 29 banks were bailed out globally [Lintner et al., 2016]. This restored financial sta-bility but raised sovereign debt. This increased debt crowded out private investments, which slowed down economic growth. This crowding out occurs because governments and private companies compete to raise funds from the same pool of investors. When government debt is deemed riskier, the financing cost and/or demand could rise. Ham-pering the financing of private companies, especially banks who need lots of financing. This in turn could lead to reduced investments or bankruptcies, thus reduced economic growth. Furthermore, due to the high levels of sovereign debt, the creditworthiness of governments was questioned. This evolution sparked the euro crisis. Doubts about the repayment ability of countries like Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal and Ireland (GIIPS) began to rise. Credit rating agencies lowered the credit ratings of some European gov-ernments, and in turn lowered the credit rating of banks located in the affected country. This is due to the credit rating agencies’ sovereign-ceiling policy; This policy states that, under usual conditions, private companies can not have a higher credit rating than the government. [Borensztein et al., 2007] found that sovereign ratings still were a signif-icant determinant for corporate ratings, even after controlling for country specific and firm specific indicators. These lowered sovereign ratings subsequently raised interest rates and decreased the prices of sovereign bonds. This affected both the asset side as the liability side of banks. The former through the home bias of banks, a sizeable sovereign debt holding. The latter through the government interventions of banks. Fur-thermore, the funding costs of banks rose because of the lowered ratings due to the

sovereign-ceiling policy, which was an additional effect for liability side.

The doom-loop mechanism was also described by [Acharya et al., 2011]. To finance a bailout governments can increase taxation or dilute existing bondholders. The in-creased taxation could lead to reduced incentives to make investments. These lowered investments would in turn lead to a lower economic growth. The dilution of existing bondholders leads to a deterioration of creditworthiness. Both these methods show the negative effects of bailouts to the sovereign’s creditworthiness. This deterioration feeds back to the financial sector through bond holdings of sovereign debt, which can be siz-able due to the home bias. [Acharya et al., 2011] found a significant co-movement between bank CDS and sovereign CDS spread post-bailout. The mechanism of the doom-loop is illustrated below.

Figure 3.1: Doomloop Own work

Research from [Covi and Eydam, 2018] found that the doom loop decreased in magni-tude after the implementation of the BRRD. Furthermore, he found evidence that the de-creased effect is explained by the new resolution scheme. Additionally, the spillovers, which were statistically significant before the BRRD, became statistically insignificant after the implementation. This research shows that the BRRD, until now, has achieved its goal to limit government intervention.

As stated above, the bailout mechanism can quickly restore financial stability. [Veronesi and Zingales, 2009] studied the effects of the U.s. government intervention during the

2008 financial crisis. They state that a market intervention, like bailouts, should solve market failures. This would not just redistribute value from the taxpayers to financial institutions, but create value. For example, a bailout could prevents a bank run, which would create value for the financial sector and society. The study found a net positive benefit of 84 billion dollar to 107 billion dollar. This was mainly due to a reduction of default probability for financial institutions.

Additionally, policies to unambiguously bailout banks in adverse macroeconomic con-ditions could be beneficial to the banking sector. This point was made by [Cordella and Yeyati, 2003]. The authors agree that bailouts create moral hazard issues, but like [?] argue that these are overstated. Bailouts also create a positive value effect. This value effect is the result of reduced probability of default and a higher charter value, the value at stake in case of bankruptcy. This higher value incentivises banks to choose safer assets to protect the higher charter value. This reduced risk-taking would be greater than the increased risk-taking caused by moral hazard.

3.2

The positive and negative effects of bailing in banks

Most research shows that the BRRD has solved the problems for which it was imple-mented, namely moral hazard [Giuliana et al., 2018], [Lewrick et al., 2019], TBTF, and the doom loop [Neuberg et al., 2016], [Barth and Schnabel, 2015]. Most authors agree that bail-ins would work in the event of an idiosyncratic problem [Avgouleas and Good-hart, 2015], the main question remains whether bail-in will work if a systemic crisis occurs. In this section, we will discuss the main critiques against the BRRD and the bail-in mechanism. We will start with the critique against the mechanism itself. Fur-thermore, we will discuss the bail-in mechanism during a systemic crisis. Finally, other potential negative effects will be discussed.

De Grauwe believes the wrong cost-benefit analysis has been made when policymak-ers chose to shift towards bail-in.[De Grauwe, 2013]. He focuses on the effects of bail-ins on unsecured deposits and argues that bank runs will become more prevalent. His reasoning can be summarized as follows: Deposit holders will fear being bailed in, which would increase the systemic risk by increasing the chance of bank runs. Further-more, if deposits get touched by the bail-in of a financial institution this could result in an economic depression. Some persons or small businesses might get disproportion-ately hurt. Depositors at other banks might withdraw their money if the deposit holder of another bank gets bailed in. This would cause widespread contagion to other fi-nancial institutions and a systemic crisis. This series of events is in De Grauwe his vision clearly not preferable to bailing out banks, in order to restore confidence. A note

should be made to these arguments of [De Grauwe, 2013], namely that he assumes unsecured deposit holders will be touched when banks are bailed-in. Unsecured de-posits are however the latest step of the bail-in waterfall. This said it is not unlikely that deposits will be touched. This happened in the Cypriot case of Laiki Bank, which is described by [World Bank, 2016] and [Dübel, 2013] and will be studied in this thesis. The credibility of the bail-in mechanism should be guarded with great precaution.

[Persaud, 2016] goes a step further and states that bail-ins will never work because bail-in instruments are quoted on market prices. “Financial crises are the result of a

market failure. Using market prices to protect us against market failure was and is always going to fail.” If prices of financial instruments start to decline because of a

bail-in, investors will possibly switch to a risk-averse state. Uncertainty will rise causing investors to sell their assets, thus starting a fire sale and a downwards spiral of prices, if no counterparty is found. These declining prices will undermine the stability of banks and the bail-in basis. This point is also made by [Lintner et al., 2016] and [Avgouleas and Goodhart, 2015]. The timing of the bail-in event is essential for an orderly resolution. Additionally, investors could search for institutions with the same characteristics as the bank in resolution and sell its bail-in able instruments, thus undermining the stability of that bank and the entire banking system. [Persaud, 2016] argues that policymakers should use the tested method of recapitalization, bad banks, and even nationalization of the failing bank. These options would be more favourable for the taxpayer than bailing in the bank.

Others, however, state that the bail-in mechanism is superior to the bailout mecha-nism.[Thole, 2014] states that moral hazard issues are dominant to the potential sys-temic effects of bail-ins. He argues that the syssys-temic risks are overstated [Ayotte and Skeel, 2010] also makes the point that bailout contradicts the principle of liability. There-fore the bail-in mechanism is superior to the bailout mechanism. According to [Thole, 2014] the comparison between bail-in and normal bankruptcy laws is more interest-ing. Thole states that other authors point out that bankruptcy laws are not adequate for financial institutions, because of the constant flow of money and the systemic risk it creates if the flow stops. However, he argues that a special bankruptcy proceeding is needed for financial institutions. The BRRD is such a special proceeding.

Other authors are less optimistic. [Avgouleas and Goodhart, 2016] states that bail-ins would work if the reasons for the failure are idiosyncratic. This point was also made by [Persaud, 2016]. These authors believe that during a systemic crisis, the bail-in mechanism is inadequate for the resolution of banks. In this case, the use of public funds would still be needed to prevent a meltdown of the financial system. If the bail-in

mechanism is not credible, issues of moral hazard and TBTF would still be significant and thus considered.

To be credible the bail-in mechanism should meet four conditions [Avgouleas and Good-hart, 2015]. These conditions are timing, market confidence, the extent of restructuring required, and accurate determination of losses. The timing deals with when the RA decides to bail-in the bank. When are institutions likely to fail or failing? If this deci-sion is made too early, the estimation of the full extent of potential losses might not be possible. Hence it would be impossible to know how much bail-inable instruments should be converted into equity or written down. Too less would lead to consecutive bail-in rounds, therefore eroding the credibility of the mechanism. A surge in uncer-tainty would follow and other banks might be drawn into the mess. If the decision to bail-in a bank is made too late, investors might have already anticipated a bail-in. They will already have sold their bail-inable instrument, if possible, leading to lower prices and less money to bail-in [Avgouleas and Goodhart, 2015]. Therefore the timing of the point of non-viability is essential for a good and credible bail-in.

The accurate determination of losses and the extent of the restructuring are important issues. In the past, these losses were always underestimated [Avgouleas and Good-hart, 2015], which lead to consecutive rounds of bailouts to recapitalize banks. Now, these inaccurate estimations could lead to consecutive bail-in rounds. This could lead to a deterioration of market confidence in the bail-in mechanism. Furthermore, if the credibility of the bail-in mechanism is questioned, contagion to other banks would be likely, thus creating a systemic crisis where the government would need to intervene. The same point can be made for the extent of the restructuring. Again if the restructur-ing does not solve the problems of the failrestructur-ing institution it could undermine the market confidence and thus the credibility of the bail-in mechanism.

Goodhart also sees other reasons why bail-ins might not work or be more costly than bail-outs. The main reasons being that bail-ins might be slower than bail-outs. This slower process might give time to investors to flee and for uncertainty to creep into the financial system. The same point was also made by [Dewatripont, 2014]. Furthermore, bail-ins could be more contagious than bailouts. This heightened contagion risk is the result of destructive incentives from deposit holders and financial institutions. Deposit holders’ money is only partially secured by a deposit guarantee scheme. All deposits above this threshold can be bailed-in, thus creating an incentive for a bank run. This point was already discussed above by [De Grauwe, 2013]. Goodhart even states that even if deposit holders were completely excluded from the bail-in, contagion would still arise because of financial institutions themselves. These financial counter-parties of

a bailed-in bank could easily run and have every incentive to do so. This would also cause equity and bondholders to flee, thus driving down prices and increasing interest. This would increase funding costs for the troubled institution, which has a pro-cyclical character. It would not be possible to refinance the debt, thus a credit crunch would occur. This would, in turn, deepen the downturn, and put the solvency of other banks at risk. Bailout, in contrast, prevents this because taxpayers can not flee. Institutions can be quickly resolved, thus preventing a systemic crisis and contagion. This heightened contagion could prove to be detrimental to the new bail-in process.

Finally [Avgouleas and Goodhart, 2015] states that in the end, individuals are the ones that will get hit by a crisis and not some abstract institutions. bail-ins will cause a few to lose a lot, while bailouts cause everyone to lose a little bit. The shape of the next financial crisis will certainly be different. The question begs itself whether it is nobler to let pensioners and individual depositors suffer the next financial crisis or to let all taxpayers share an equal amount of suffering. If people have the feeling that their pensions are at risk, political consequences will be high.

These above described negative effects of the bail-in mechanism need to be balanced with the positive effects of bail-ins. Bail-ins solve the issue of moral hazard, which are more important than systemic stability concerns according to [Thole, 2014]. They break the doom-loop by avoiding government intervention and its use of taxpayers’ money. Furthermore the bail-in mechanism adheres to the liability principle [Ayotte and Skeel, 2010]. Finally, the interest of the public is specifically analysed when decisions to bail-in banks are made.

3.3

Market discipline and its effects on financial

instru-ments

The authors above mainly discussed the theoretical possible consequences of the new bail-in mechanism. Empirical research has also done to estimate the actual conse-quences of the new bail-in mechanism. This section will review the studies that have been done on market discipline when the new bail-in mechanism was announced. Fur-thermore, the event studies, on recent bail-in events, that have been done will be re-viewed. These papers will act as the foundation for the research done in this disserta-tion, especially the paper of [Dübel, 2013] which describes the different bail-in events that have already taken place. These events were however mostly hybrid bail-ins.

market-implied probability of government intervention declined after the implementa-tion of the BRRD. Both authors used CDS data to estimate the implicit government guarantee. [Barth and Schnabel, 2015] found that before the financial crisis, investors did not include much individual bank risks in CDS-spreads. However, the crisis sparked a strong effect of the financial strength of an institution on its CDS-spread. The crisis served as a wake-up call. The research does not link this effect to the BRRD but ex-plains this change in CDS-spreads by the uncertainty of the true solvency of banks during the financial crisis. [Neuberg et al., 2016] used two different CDS contracts to estimate the implied probability of government intervention. A new CDS contract was made because of the bail-in regulation. This created a situation where both the old and the new contract were simultaneously traded on the financial market. The difference in CDS-spread between these two contracts could then be interpreted as the implied probability of government intervention. This probability declined during the 2014-2016 period. According to [Neuberg et al., 2016] this can be linked to new bail-in regulation. Additionally, the authors found that the likelihood of bail-in was associated with the sys-temic importance of banks and idiosyncratic risks. This finding is consistent with the theory of [Avgouleas and Goodhart, 2016].

Other authors looked at bond prices instead of looking at CDS-spreads. [Giuliana et al., 2018] used the difference in yield between unsecured (bail-inable) and secured bonds (non-bail-inable) bonds to research market discipline. He found that bail-in events in-creased the market discipline, however, the effect was found to be weak. This would mean that investors incorporate the risk of bank failures in their pricing of unsecured bonds. [Lewrick et al., 2019] also researched the market discipline effects of the BRRD by using senior bail-in bonds and similar bonds that can not be bailed-in. In this way, they could also estimate the bail-in premium. They found that the bail-in premium was higher for riskier banks, which implies that there is market discipline present. Further-more, they found that the premium was pro-cyclical. When market-wide credit risks lower, these premiums decline as well. Banks use this pro-cyclical character to time the issuance of bail-inable debt. [Nuevo, 2019] used the spread between banks subor-dinated bonds and senior unsecured bonds. No significant increase of the spread after the implementation of the BRRD was found. Nor evidence of heightened risk percep-tions of investors was found.

A description of the case studies upon which this thesis will focus can be found at [Dübel, 2013] and [World Bank, 2016] These authors describe several cases of bank restructuring. However, not all cases they describe have used the bail-in rules. [World Bank, 2016] explicitly states that these cases, before the BRRD was implemented, can not be used to infer conclusions about the effectiveness of the new rules. Few event

studies have been made. As far as I know, only [Schäfer et al., 2016] used the cases of [Dübel, 2013] to research the CDS spreads during these events. The study found that during these events spreads widened and stock prices fell. The reaction depended on the fiscal strength of the sovereign and political spillovers. It should be noted that [Schäfer et al., 2016] used many bail-in cases before the BRRD implementation. There-fore his conclusions can not be used to infer the effectiveness of the new resolutions scheme. In the result section of this dissertation, the results of [Schäfer et al., 2016] will be compared with the obtained results from this dissertation’s event studies of the same cases.

The current body of literature mainly focused on the theoretical discussion of the TBTF effect and its linked problems of moral hazard and the doom loop. Some event studies have been done, but mainly on events before the BRRD was in place. Little research has been made about contagion effects to other banks, nor has the literature addressed more recent cases. This is an important gap in the literature, certainly, because the main critique against this new bail-in mechanism is directed towards a possible heightened systemic risk and financial instability. Therefore these possible contagion effects should be researched. In this respect, it is important to note that this thesis will discuss potential contagion resulting from bail-in events and not if the bail-in mechanism would work in a full-blown systemic crisis. This was impossible because thus far no such event took place after the crisis of 2008. However, the current COVID-19 crisis might test the financial system and its robustness. This thesis will research the effect on CDS spreads and stock returns during certain bail-in cases. Furthermore, we will research the cases that have used the BRRD. There are however only a limited number of cases that comply with this condition. Therefore the results should be treated with caution.

4

Events

This thesis will empirically analyse five different events concerning the resolution of banks. Three of these events occurred before the BRRD rules were applied. The other two events applied the BRRD rules. This section will give an overview of these cases and make predictions about their outcome. These predictions will be tested in by using an event study methodology. This overview is largely based upon the work of [World Bank, 2016] and [Dübel, 2013] for the cases before the BRRD was implemented and on own research for the cases after the implementation of the BRRD.

4.1

Netherlands: SNS Reaal

SNS Reaal was one of the four largest financial institutions in the Netherlands. Their insurance division got hit in 2008 because of the great financial crisis. The government lent SNS Reaal 750 million euros to reinforce its position. However, in 2012 the mort-gage portfolio of SNS Reaal was expected to have losses between 1,4 and 2,1 billion euros. The auditor of SNS Reaal said in a statement that it was unsure if SNS Reaal was able to comply with the capital requirements of Basel. These results were meant to be published in February of 2013. However, negative news started a bank run on deposits and led to a huge drop in the share price. The Dutch central bank declared that SNS Reaal did not meet their capital requirements and when their deadline expired to solve the issue, the bank was nationalized by the Dutch government.

This happened on February the 1st of 2013, therefore this data has been used as the event date in the event study analysis. Shareholders and junior bondholders were bailed-in for around 1,9 billion euros. Furthermore, the state injected 3,7 billion to re-capitalize the bank. Senior bondholders were not bailed in. This would not have been the case if BRRD rules were present. Which might have prevented the use of public money. The Dutch finance minister later declared that senior bondholders were not bailed-in because of financial stability reasons.

Because of the swift resolution of the bank, financial stability was not threatened. There-fore, it is expected that this case will not have a contagion effect on other European banks. Most of the capital was still provided by the government. Furthermore, the Dutch low debt/GDP level allowed the government to use public money without an ele-vated risk perception. This event was in many respects a continuation of the previous policy of bailouts. Nevertheless, shareholders and junior bondholders were bailed-in. Additionally, the case occurred when the SRM was being debated. Finally as pointed out by [Schäfer et al., 2016] the Dutch finance minister, Jeroen Dijselbloem, was just appointed as president of the Eurogroup. These reasons make it an interesting case to analyse. Generally, it is expected that this event would not have affected bail-out probability, thus a higher levels of CDS spreads are not expected for other European banks. Nor is it expected that stock returns of other banks had an abnormal reaction to this event.

4.2

Cyprus: Laiki

The second event that will be analysed is the resolution of Laiki, a Cypriot bank. The event happened during the negotiation of the BRRD in March 2013. It marked a turning point in the resolution of banks. The past solutions of full-scale bailouts were replaced with partly bailout and partly bail-in. For the first time, uninsured deposits of retail in-vestors were bailed in. This proposal by the Eurogroup on March 16, 2013, caused international criticism. The Cypriot’s parliament rejected this proposal, which caused huge amounts of uncertainty. The banking system was shut down for two weeks. Dur-ing this period the deal was renegotiated and eventually on the 25th of March a new resolution plan was announced. Laiki would still be resolved by bailing in shareholders, bondholders and, for the first time, uninsured retail depositors. Other assets of Laiki were transferred to the Bank of Cyprus. To avoid a bank run after this resolution, capi-tal controls were implemented. These capicapi-tal control measures were relaxed in phases and were things returned to normal circumstances 2 years later. The 16th of March will be used as the event date for our event analysis.

This case showed the importance of a swift resolution like we have discussed in the literature review above. [Dübel, 2013] suggest that a tighter capital control of junior bondholders would have been preferable. This implies that a larger bail-in basis could have been used in this case, thus limiting the haircut of retail depositors. The delay caused by the rejection of the Cypriot parliament caused huge economic costs. The [World Bank, 2016] concludes that if BRRD mechanisms were present a bailout, thus the use of public money might have been avoided.

We expect a large reaction across European banks during the event date because it was a turning point in the resolution policy for financial institutions. This proposal by the Eurogroup confirmed the policy switch from bailouts to bail-ins. Therefore, this case should have led to lower bailout expectations. Thus, leading to a higher CDS spreads of European banks because of newly incorporated risks. It is expected that this effect should be greater for Globally Systemic Important Financial Institutions (G-SIFI), because of the Too-Big-Too-Fail issue discussed in the literature review. There is an incentive for governments to quickly inject public money into large financial institutions to prevent a systemic financial crisis. Secondly, we expect a higher reaction for banks that are not well-capitalized. A bank’s capital is a buffer for unexpected losses, hence the higher this buffer, the lower the probability of default. Thirdly, it’s expected countries with a high debt/GDP ratio might not be able to bail out banks, even if they wished to do so. This could create lower bail-out expectations hence a higher CDS spread. Finally, stock returns would show the opposite effect of CDS spreads, therefore it is expected

to see negative stock returns of other European banks. These predictions will be tested by using an event study methodology.

4.3

Portugal: Espirito Santo

Banco Espirito Santo was the third-largest bank in Portugal, therefore it had a large role in the national economy and financial system [World Bank, 2016]. The bank expe-rienced its first troubles when in July 2014 it released its financial results for the first half of 2014. Banco Espirito Santo (BES) reported unexpected losses of 1,5 billion euros. These losses directly affected the capital buffer, which fell below the minimum require-ments set out by the Basel regulation. This negative news was sharply reflected in the share price, which dropped to 12 cents. This caused a suspension of trading activities on the 1st of August 2014. On August 3, 2014, the national bank of Portugal applied resolution measures to BES. This date will be used as the event date for this case. The bank was split up between a good and bad bank. Healthy assets were transferred to the good bank, called Novo Banco. This made sure that the financial stability of the system was not threatened. Depositors were not bailed-in and key activities were not interrupted. It should be noted that the bail-in tool was not used, because the national law of Portugal did not yet implement the BRRD into national law. The only resolution tools available in the national law of Portugal were the sale of business tool and the bridge institution tool.

This was the first case after the BRRD was approved, however, it was not yet converted into Portuguese law. However, [World Bank, 2016] states that the national regime of Portugal was very similar to the BRRD rules. Lowered bailout expectations probably had already been incorporated into prices after the Laiki case. Therefore, no large changes in CDS spread or stock prices are expected.

4.4

Spain: Banco Popular

On 6th June of 2017 Banco popular was deemed failing or likely to fail by the authorities. This event happened while the BRRD was already converted into national law and thus could provide us with relevant insights. the 6th of June will be used as our event date in the event study.

Banco popular’s positions were already under pressure for several months. After the EBA stress tests of 2016, a capital increase of 2,5 billion euros was done to comply

with the rules. In the adverse scenario of the EBA stress test [EBA, 2016]. the CET1 ratio of the bank dropped to 7.01%. The bank’s strategy was changed to solidify its position. It started to look for raising new capital or selling the bank to a competitor. A sudden deterioration caused liquidity problems and authorities declared the bank likely to fail on the 6th of June 2017, this date is used as the event date. This happened amid a sale process with Santander. The single resolution board decided to apply two tools: The sale of business and the bail-in tool. Shares and additional tier 1 instruments were written down. Tier two instruments were converted in shares

Because the bank was already in the midst of a sale process, the sale of business was fast-tracked. Santander, the buyer, already analysed the books of Banco Popular during previous talks. Later the bank was sold to Santander for 1 euro.

No large reaction is expected in the CDS market nor in the stock market. The sale process was already started by Santander before the PONV decision. This ensured a fast resolution, hence financial stability was not in danger.

4.5

Italy: Monte Paschi Di Siena

The case of Monte Paschi Di Siena (MPS) is a special one because it could be seen as a bailout disguised as a bail-in. On the 4th of July 2017, the European Parliament approved a precautionary recapitalisation of MPS. The amount of 8,1 billion euros in-cluded a conversion of junior bondholders of 4,3 billion and a capital injection of 3,9 billion euros of the Italian government. Furthermore, the Italian government foresaw 1.5 billion euros to compensate retail investors that bought junior debt of MPS. The use of the precautionary capitalisation measure was quite controversial. This use of public money can only be applied if at least 8% of all liabilities have been bailed in. Addition-ally, the capitalisation should remedy a systemic threat. Some authors (Taking Bail-in Seriously) argue that MPS is not a systemic bank and therefore should not be able to apply for a precautionary capitalization. These authors make the case that this mea-sure could potentially undermine the credibility of the BRRD. Namely, it could reflect that in certain circumstances the BRRD rules will be bent to allow the injection of public money. This completely overrules the point of the BRRD, to avoid the use of taxpayers money. The authors argue that the ECB should have triggered the resolution of the bank and thus started the bail-in waterfall. This to send a strong signal to the markets [Götz et al., 2017].

other cases, namely a lowering of CDS spread among other European banks and a rise in stock returns. The use of the precautionary capitalization and the bending of the BRRD rules could lead to a higher bail-out probability. This effect would be greater for Globally Systemic Important Institutions who would be more prone to government interventions. Banks with a low CET1 ratio could also benefit from lower CDS spreads.

5

Data

In this section, the data that has been used to empirically analyse the resolution cases will be discussed. First, the CDS data will be discussed. Second, stock price data will be discussed. Finally, the bank-specific characteristics will be discussed.

5.1

CDS data

CDS data was used in the event study to estimate the impact of the different cases dur-ing the 2013-2017 period. To obtain the date, a CDS database, which consisted of 69 European banks was used. It should be noted that in this sample there are also banks from Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. Furthermore, no Greece banks are present in this sample. A full list of the banks can be found in the appendix.

This CDS data obtained from the database consisted of CDS spreads. Therefore, the data needed to be converted into changes in the CDS spread. This was calculated as follows:

CDSt− CDSt−1

The data was already in amounts of basis point, hence it was not necessary to divide this number to obtain returns.

The number of banks’ CDS data that has been used in different cases can differ. This is due to the rise of new banks and the fall of existing banks during the 2013-2017 period. For example, Novo Banco was created during the resolution of Banco Poplar in 2017. Evidently, there is no CDS data for earlier periods. The opposite is also true. For example, Banco Popular has been resolved in 2017, therefore there is no CDS data available after the resolution. An overview of the banks used during each event can be found in the appendix.

As market index, the DS Europe 5-Year Credit Default Swap Index is used to estimate the market model.

In figure 5.1 the distributions of the daily CDS spread changes is illustrated. In the blue we see the distribution during the estimation window, while in the red we see the distribution of the changes during the event window.

5.2

Stock data

Concerning the stock data, a sample of 79 European banks was used. Again, this number could vary from for each event, because of the same reasons discussed above in the CDS data. An overview of the banks used in each event can be found in the appendix. The stock data obtained from the database was the daily closing price of European banking stocks total return indices.

This daily price data needed to be converted into daily returns. Therefore, the following formula was used:

ln(Pt/Pt−1)

The logarithmic returns were calculated instead of using ordinary returns. This has certain advantages and is common in academic research because of its properties. The stock prices were total return indices, thus taking into account dividends that have been paid out. These indices give a better view on the return obtained by investing in these banks compared to daily stock closing prices. To estimate the market model used in our event study, we used the EUROSTOCK 50 total return index. This complies with a broad market index that a market model requires.

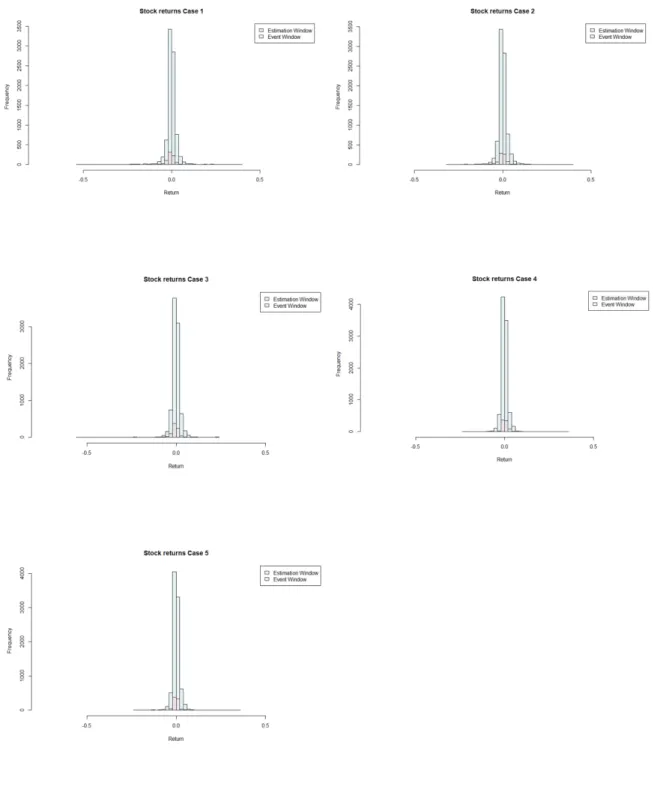

In figure 5.2 we see the distributions of the daily stock returns of each event. In blue the returns during the estimation window are illustrated. In red the returns during the event window are given.

Figure 5.2: Stock Return distributions

5.3

Bank specific characteristics

In order to estimate the impact of banks specific ratios, the SNL database was con-sulted. Data was retrieved for the period 2006-2019. This data was available in yearly and quarterly data. The quarterly data would have been preferable because of its more precise timing, which could have led to improved forecasts. However, the quarterly

data had more missing values. Therefore, the yearly data was used to construct, a more, complete database.

Five ratios were calculated in order to estimate their impact. These ratios each reflect another risk element in the banking sector. First, to gauge the capital risk the amount of common equity tier 1 was divided by the risk-weighted assets.

CET 1/RW A

This is the main capital requirement of Basel 3 and is, therefore, one of the most im-portant ratios. Second, the return on equity (ROE) is calculated as follows:

pretax income/equity

The database used had no data about post-tax income, which is normally used to cal-culate ROE. Therefore, the pretax income was used. The advantage of this approach is that differences in tax legislation are neglected. However, these differences might be important for investors. ROE can be interpreted as a general measure of performance of financial institutions. Third, the interest risk is determined as follows:

loans/deposits

. A number above 100% reflects a situation where interest risk is significant. Fourth, the efficiency of operations is captured by dividing the following ratio:

operational costs/operational income

. Finally, the credit risk is captured by

problem loans/gross loans

To capture the impact of the sovereign debt on the probability of bailout, The ECB his website was consulted for the Debt/GDP ratios of each country. The ratios of Norway and Switzerland were found on their respective national bank’s website. Additionally, the FSB’s website was consulted to make dummy variables for the Globally Systemic Important Banks for each year.

Table 5.1: Bank Specific Characteristics 2013

Statistic N Mean St. Dev. Min Pctl(25) Pctl(75) Max CET1/RWA 62 0.142 0.114 0.066 0.109 0.145 0.982 Loan/Deposit 62 2.679 10.375 0.660 1.102 1.580 80.289 NPL/TOTAL LOANS 62 0.075 0.074 0.003 0.025 0.099 0.400 ROE 62 0.012 0.126 −0.376 −0.032 0.089 0.181 COST/INCOME 62 0.653 0.350 −1.494 0.543 0.735 1.583 Sovereign debt 62 0.908 0.290 0.290 0.787 1.163 1.324 GSIF 62 0.258 0.441 0 0 0.8 1 GIIPS 62 0.328 0.473 0.000 0.000 1.000 1.000

Table 5.2: Bank Specific Characteristics 2014

Statistic N Mean St. Dev. Min Pctl(25) Pctl(75) Max CET1/RWA 62 0.143 0.115 0.050 0.107 0.146 0.998 Loan/Deposit 62 2.957 12.946 0.682 1.098 1.535 102.382 NPL/TOTAL LOANS 62 0.068 0.064 0.003 0.022 0.096 0.294 ROE 62 0.003 0.246 −1.341 0.003 0.098 0.195 COST/INCOME 62 0.550 0.842 −5.664 0.539 0.731 1.742 Sovereign debt 62 0.902 0.286 0.290 0.787 1.055 1.324 GSIF 62 0.258 0.441 0 0 0.8 1 GIIPS 62 0.323 0.471 0 0 1 1

Table 5.3: Bank Specific Characteristics 2017

Statistic N Mean St. Dev. Min Pctl(25) Pctl(75) Max CET1/RWA 55 0.197 0.369 0.100 0.123 0.158 2.870 Loan/Deposit 55 1.221 0.354 0.668 0.971 1.452 2.199 NPL/TOTAL LOANS 55 0.060 0.076 0.003 0.015 0.068 0.343 ROE 55 0.070 0.113 −0.409 0.042 0.124 0.212 COST/INCOME 55 0.688 0.317 0.395 0.551 0.710 2.596 Sovereign debt 55 0.865 0.294 0.355 0.653 0.986 1.341 GSIF 55 0.273 0.449 0 0 1 1 GIIPS 55 0.345 0.480 0 0 1 1

6

Methodology

In this section, the methodology applied to empirically analyze the different bail-in events will be discussed. These methods will allow us to draw conclusions about these events with respect to their market reaction, both on the CDS and stock market. Addition-ally, these reactions will be regressed on bank-specific ratios to determine the under-lying drivers of these market reactions. Firstly, the event study methodology will be explained. Afterwards the same will be done for the regression methodology.

6.1

Event study methodology

The event study is largely based upon the work of [Mackinlay, 1997]. In his paper, he describes a step by step approach to conducting event studies. The approach uses daily financial data to study the abnormal return of an event on the value of assets dur-ing the event date. For example, one could study earndur-ing announcements of different companies at different moments, and by aggregating this data across securities study the impact of earning announcements. To study anticipatory effects and post-event ef-fects, abnormal returns are usually aggregated across time, which results in cumulative abnormal returns. In this case the event window comprises multiple days. In this thesis, five different events will be analysed, therefore we will apply this step by step approach for each event individually. For each event, the cumulative abnormal returns of each security will be studied during the exact same event window. This causes completely overlapping event windows, a phenomenon called clustering, which causes problems when aggregating across securities. This issue and the solution this thesis applied will be discussed below. The method of [Mackinlay, 1997] assumes that the market is efficient and returns are normally distributed. Therefore this thesis uses the same assumptions. However, these assumptions are heavily debated in academia.

The first step in the event study methodology is to define the events to be studied. This thesis will study different bail-in cases. five events were defined:

1. SNS Reaal

2. Laiki Bank

3. Banco Espirito Santo

4. Banco Popular

For each case, an event data and an event window should be determined. The following dates for each event were chosen:

1. 1st of February, 2013: the bank was nationalized

2. 18th of March, 2013: the proposal by the Eurogroup

3. 4th of August, 2014: the resolution of BES

4. 6th of June 2017: bank declared likely to fail

5. 4th of July 2017: European Commission has approved Italy’s plan

If the decision was made during the weekend, the event date is the following first trading day. The event windows’ width (amount of days) was varied to check the robustness of the findings. The largest event window is 5 days before the event day until 5 days after the event days. The smallest event window that was used is the event day itself without other days included. Furthermore, the sample of firms to investigate should be determined. This was discussed in the section above.

To estimate the events impact on certain assets an abnormal return should be calcu-lated. This is defined by [Mackinlay, 1997] as follows: “The abnormal return is the actual ex-post return of the security over the event windows minus the normal return of the firm over the event window.” The formula of these returns can be found below:

ARi,τ = Ri,τ − E(Ri,τ|Xτ)

To be able to calculate these abnormal returns, we should first estimate the normal returns. [Mackinlay, 1997] discussed several methods to estimate these returns. The most common method is the market model. This estimation method has been applied to both the stock market data and CDS data. These normal returns are estimated within the estimation window. This is the period before the first day of the event window. We have opted for an estimation window of 120 trading days.

The market model of the CDS data was estimated by an Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regression in R. The daily changes in CDS spreads of each individual firm were re-gressed on the daily CDS spread changes in the DS Europe 5-Year Credit Default Swap Index, as discussed in the previous chapter. The following formula was used:

Ri,t = α + βiRm,t+ εi,t

with Rit and Rmt the period t changes in CDS spread of bank i and the DS Europe

5-Year Credit Default Swap Index

The market model of the stock data was estimated by applying the same method as described above. The individual logarithmic stock returns were regressed on the daily logarithmic market returns. The EUROSTOCK 50 was used as the market index.

After the estimation of the market model, we can use this model to calculate the esti-mated normal returns during the event window by inserting the market returns in the model.

N Ri,τ = ˆαi+ ˆβiRm,τ

Now that we have estimated the normal returns, the abnormal returns can be estimated by using formula:

ARi,τ = Ri,τ − ˆαi+ ˆβiRm,τ

These abnormal returns should, however, be aggregated in order to draw meaningful conclusions about the events that we study. These aggregations can be done across two dimensions, namely across time and securities. This aggregation across securities poses a serious problem in our study. This aggregation assumes that the event win-dows of these different securities do not overlap. However, in this thesis, we study five different cases. For every single case, the event windows completely overlap for each security. Therefore, we can not assume that these abnormal returns will be indepen-dent of each other, thus we can not aggregate them across securities. This problem is called clustering, a problem which we will address later in this thesis. First, we will focus on the aggregation across time.

Aggregating securities through time means that we calculate the sum of each day’s abnormal return of the event window. As stated previously, this windows’ width was varied. The resulting returns from aggregating the securities through time will be called Cumulative abnormal returns (CAR) These CARs can be calculated by using the fol-lowing formula: CARi(τ1, τ2) = τ2 X τ =τ1 ARi,τ

The asymptotic variance of CAR is σ2

i(τ1, τ2) = (τ2 − τ1 + 1)σε i2 with σ2ε i the variance of

the residuals of the market model.

These CARs show us the cumulative effect that an event had during the different event windows. The CAR of the smallest event window equals the abnormal return during the event day. The significance of each individual security’s CAR was tested for each

event. This by applying the following test statistic:

d

SCARi,τ = CARi,τ/ˆσi,τ

This test statistic is called the standard t-statistic or standardized CAR(SCAR) [Pyn-nönen, 2005] The null hypothesis is that the cumulative abnormal returns do not sig-nificantly vary from a mean of zero. If this null hypothesis can be rejected, it can be interpreted as evidence of an abnormal reaction caused by the specific case. We have tested our null hypotheses by using a two-sided test on a 5% significance level. The null hypothesis has a t-distribution with the following amount degrees of freedom equal to the number of days in estimation period - 2. 2 degrees of freedom are subtracted, because of the estimation of alfa and beta. The results of these tests can be found in the appendix and will be discussed in the following section.

As discussed above, we can not easily aggregate abnormal returns across securities because of clustering issues. If there is clustering and the abnormal returns are not independent across securities, a low cross-correlation could cause over-rejection of the null hypothesis. To circumvent this problem of clustering, [Kolari and Pynnönen, 2010] proposes a modified test statistic to take into account these cross-correlations. We have applied this modified test statistic in order to aggregate the returns across securities. This method will now briefly be discussed.

The method of [Kolari and Pynnönen, 2010] works with standardized abnormal returns but can easily be adjusted to work with standardized cumulative returns. The calculation of the SCAR’s has already been discussed above. To aggregate the SCARs across securities we take the average of all the individual SCAR

SCAR = 1/n

n

X

i=1

SCARi

Furthermore, the variance of the SCARs needs to be calculated. This can be estimated by using the following formula s2 = 1/(n− 1)Pn

i=1(SCARi− SCAR. This is a biased

estimator of the variance when there are return correlations. Therefore this variance needs to be adjusted accordingly. [Kolari and Pynnönen, 2010] suggests the following formula:

with ˆr the average of the sample cross-correlations of the estimation period residuals. The variance of the mean standard cumulative abnormal return can be estimated by using the following formula:

![Figure 2.1: bail-in procedure [Lintner et al., 2016]](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5doknet/3293286.22081/15.892.243.648.315.728/figure-bail-in-procedure-lintner-et-al.webp)

![Table 7.1: Stock reactions SNS Reaal: t-values [-5;+5] [-2;+2] [-1;+1] [0] Full Sample 0.706 0.256 0.520 −0.691 GIIPS −1.037 −1.554 −0.539 −1.397 Non-GIPPS 1.097 0.891 1.091 −0.141 G-SIF 0.016 −0.047 0.144 −0.709 Non-G-SIF 0.533 0.209 0.394 −0.325 Note: *p](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5doknet/3293286.22081/42.892.237.657.261.406/table-stock-reactions-reaal-values-sample-giips-gipps.webp)

![Table 7.2: CDS reactions SNS Reaal: t-values [-5;+5] [-2;+2] [-1;+1] [0] Full Sample 1.631 0.728 1.021 0.375 GIIPS 1.718 0.982 0.837 0.558 Non-GIPPS 1.391 0.531 0.964 0.281 G-SIF 1.152 0.490 0.894 0.335 Non-G-SIF 1.197 0.574 0.729 0.258 Highest CET1/RWA 1.](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5doknet/3293286.22081/43.892.204.689.208.534/table-reactions-reaal-values-sample-giips-gipps-highest.webp)

![Table 7.3: Stock reactions Laiki: t-values [-5;+5] [-2;+2] [-1;+1] [0] Full Sample −1.533 −1.131 −0.988 −1.125 GIIPS −1.014 −0.601 −0.814 −0.461 Non-GIPPS −0.994 −0.849 −0.525 −0.951 G-SIF −1.868 −1.602 −2.074 ∗ −1.982 ∗ Non-G-SIF −0.722 −0.474 −0.324 −0.4](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5doknet/3293286.22081/44.892.222.665.637.785/table-stock-reactions-laiki-values-sample-giips-gipps.webp)

![Table 7.4: CDS reactions Laiki: t-values [-5;+5] [-2;+2] [-1;+1] [0] Full Sample 1.420 0.509 1.272 0.956 GIIPS 1.301 0.774 1.408 1.379 Non-GIPPS 1.178 0.355 0.995 0.633 G-SIF 2.06 ∗ 0.831 1.332 1.147 Non-G-SIF 0.828 0.274 0.736 0.491 Highest CET1/RWA 1.525](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5doknet/3293286.22081/45.892.210.687.136.461/table-reactions-laiki-values-sample-giips-gipps-highest.webp)

![Table 7.5: Stock reactions BES: t-values [-5;+5] [-2;+2] [-1;+1] [0] Full Sample −0.644 −0.998 −0.357 0.411 GIIPS −1.018 −1.079 −0.805 0.578 Non-GIPPS 0.116 −0.223 0.292 0.143 G-SIF 0.250 0.089 0.304 0.686 Non-G-SIF −0.596 −0.891 −0.437 0.174 Note: *p<0](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5doknet/3293286.22081/46.892.241.652.142.292/table-stock-reactions-values-sample-giips-gipps-note.webp)

![Table 7.9: Stock reactions MPS: t-values [-5;+5] [-2;+2] [-1;+1] [0] Full Sample 2.796 ∗ 2.332 ∗ 1.400 1.266 GIIPS 2.933 ∗ 1.728 0.836 1.185 Non-GIPPS 1.746 1.656 1.221 0.759 G-SIF 4.379 ∗ 4.117 ∗ 2.108 ∗ 0.833 Non-G-SIF 1.392 1.189 0.733 0.753 Note: *p<](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5doknet/3293286.22081/49.892.248.645.421.567/table-stock-reactions-values-full-sample-giips-gipps.webp)