FORWARD GUIDANCE: AN

EVALUATION OF ITS

EFFECTIVENESS

Aantal woorden: <15,237>Jerôme Denys

Stamnummer: 01606492Promotor: Prof. Dr. Selien De Schryder

Masterproef voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van:

Master of Science in de Handelswetenschappen

Afstudeerrichting: Finance en Risicomanagement

PERMISSION

I declare that the content of this Master’s Dissertation may be consulted and/or reproduced, provided that the source is referenced.

Name student: Jerôme Denys

Preamble

I was able to conduct my research as originally planned. There were no steps that could not be carried out because of the corona crisis.

This preamble is drawn up in consultation between the student and the supervisor and is approved by both.

i

Summary

What is left to do when a considerable decline in aggregate demand and economic activity rob a central bank from its conventional monetary policy tools to turn this situation around? One of the remaining options is ‘Forward Guidance’. Merely by communicating its intended policy stance, strategy and economic outlook, a central bank tries to mitigate the negative effects of an economic crisis, let the public believe in extra monetary accommodation, increase current economic activity, … This thesis covers all aspects of this unconventional monetary policy tool, to give an insight of its mechanism and complexity. An overview of the existing literature on the effectiveness of Forward Guidance, as well as an empirical analysis of the effects on inflation expectations of market participants in the Euro Area is given. I find that although Forward Guidance is a seemingly simple concept, it depends on many different factors to reach its desired effect. Forward Guidance can have a significant impact on asset prices and the financial markets, but the evidence on its ability to steer the real economy suggests a less powerful effect. This is in line with the results of the empirical analysis, which shows that although a significant positive effect was measured on inflation expectations during a period of a binding effective lower bound (ELB), this effect was relatively small. I conclude that Forward Guidance is definitely more than just a transparency device and can play a meaningful role as monetary policy tool during an economic crisis, as well as in more prosperous times.

ii

Foreword

This thesis is about the effectiveness of Forward Guidance, a non-conventional monetary policy tool. This subject had me interested because of the great tension between its implied simplicity on the one hand, and the possible large effects it can cause on the other hand. Furthermore, the subject of monetary economy wasn’t covered in an extensive way during my courses in the last three and a half years, so I was eager to introduce myself to its concepts and theories.

During the writing of this thesis a learned a lot about monetary economy in general and Forward Guidance in particular and tried to provide an understandable, enjoyable and informative reading experience for anyone who wishes to educate themselves on the subject of Forward Guidance.

I sincerely would like to express my gratitude towards Prof. Dr. De Schryder for giving me the opportunity to write this thesis and the provided guidance and feedback throughout the writing of this thesis.

Jerôme Denys 27/05/2020

iii

Summary ... i

Foreword ...ii

List of Abbreviations ... iv

List of Tables and Figures ... v

Introduction ... 1

The complexity of Forward Guidance ... 2

Types and forms ... 2

Motives for Forward Guidance ... 3

Heterogenous beliefs ... 6

The lift-off ... 8

Forward Guidance Puzzle ... 10

Literature review ... 12

Effect on financial markets and its expectations ... 12

Effect on the real economy and its expectations ... 17

Empirical Analysis ... 19 Introduction ... 19 Identification approach ... 20 Method ... 21 Results ... 24 Conclusion ... 26 Reference List ... vi

Attachment 2.1: Intraday OIS rates for different maturities on April 21, 2009 in Canada. Attachment 2.2: Intraday US dollar OIS rates for different maturities on August 9, 2011. Attachment 2.3: Intraday US dollar OIS rates on January 25, 2012.

Attachment 2.4: Market expectations of the forward path of the repo rate in Sweden on the monetary policy update of the Riksbank.

Attachment 3.1: List of all Monetary Policy Announcement days by the ECB between December 15, 2016 and December 31, 2019. Together with the most significant changes in language and statements about Forward Guidance and inflation.

Attachment 3.2

:

Gretl output of the White’s Test conducted for the 2-year horizon sample. Attachment 3.3: Gretl output of the White’s Test conducted for the 10-year horizon sample.iv

List of Abbreviations

BEIR: Breakeven Inflation Rates Bp: basis points

CET: Central European Time

CDU: Christlich Demokratische Union CPI: Consumer Price Index

DSGE: Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium e.g.: exempli gratia (‘for example’)

ECB: European Central Bank ELB: Effective Lower Bound ESI: Economic Surprise Index Et al.: et alii (‘and others’)

FOMC: Federal Open Market Committee GDP: Gross Domestic Product

i.e.: id est (‘that is’)

OLS: Ordinary Least Squares

PCE: Personal Consumption Expenditures QE: Quantitative Easing

SPD: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands SPF: Survey of Professional Forecasters

v

List of Tables and Figures

Figure 1: The forward breakeven inflation rates from Germany for a 2-year horizon.

Figure 2: The forward breakeven inflation rates from Germany for a 10-year horizon.

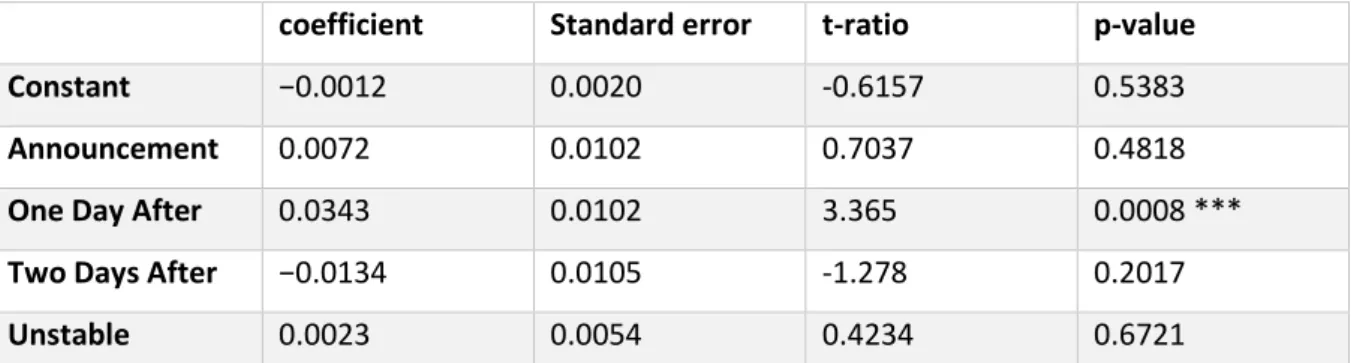

Table 1: Output from the OLS regression with the first differences from the forward breakeven inflation rates at a 2-year horizon as dependent variable.

Table 2: Output from the OLS regression with the first differences from the forward breakeven inflation rates at a 10-year horizon as dependent variable.

1

Introduction

Most central banks conduct monetary policy to prevent an excessive level of inflation or deflation and keep an as high as possible sustainable level of employment (others may target a specific exchange rate). A central bank has three standard monetary policy tools to achieve this: open market operations, the discount rate and the reserve requirements. Besides these three tools, they also have alternative monetary policy tools at their disposal, of which Quantitative Easing (QE) and Forward Guidance are most well-known. In this thesis the focus lays on the latter.

Formal Federal Reserve chairman Bernanke suggested that transparency enhances the efficacy of monetary policy conditions by anchoring long-term expectations of the inflation rate, encouraging market participants to anticipate policy and thus improve economic and financial conditions by providing (hopefully) useful insights about its reaction function (Bernanke, 2017). The most modern tool for central bank transparency is Forward Guidance. The original description of Forward Guidance by Eggertson & Woodford (2003) was that it is a tool to lower long-term interest rates through the commitment to low future spot rates and the expectations hypothesis.

“Forward Guidance are explicit statements made by a central bank about the outlook for future policy, in addition to its announcements about the immediate policy actions that it is undertaking” (Woodford, 2012, p. 2). Forward Guidance thus implies communication of the central bank about her monetary policy decisions and economic outlook and has been around for many years. Filardo & Hofmann (2014) for example stated that Forward Guidance is not new and that central banks published qualitative descriptions of their interest rate policies to inform the public since the 1990s. In the late 1990s, central banks of small economies like the Czech Republic, Iceland, Israel, New Zealand, Norway and Sweden adopted a form of quantitative Forward Guidance by regularly forecasting the path of future interest rates.

Although Forward Guidance has been around for years, it became more widely used in the years after the Global Financial Crisis. The main reason for this is that conventional monetary policy tools became less useful during and after that period. An important factor in this was the binding conditions of the ELB. The ELB implies that a central bank lowers its target interest rate to (almost) zero to stimulate the economy. A simplified definition of the policy interest rate is the nominal rate central banks charge commercial banks for lending money. Because these commercial banks will ultimately pass this interest rate to their clients (households and businesses) and/or adjust their availability of credit, it affects spending and investment decisions made by market participants. A lower target rate, compared to the neutral value at which the economy is in equilibrium, will lead in principle to economic growth, but also to higher inflation (this is called an accommodative monetary policy

2 stance). Raising the target rate will cause an opposite effect (this is called a restrictive monetary policy stance). During the Global Financial Crisis, which started in 2008, central banks reached the ELB and were no longer able to provide extra monetary stimulus through lowering the policy interest rates. The scenario where conventional monetary policy becomes ineffective and can no longer stimulate economic activity by lowering its policy rate is known as a liquidity trap. Alternative procedures, like Forward Guidance, often become necessary in an ELB environment.

This paper proceeds as follows. Section 1 presents the different aspects and the complexity of Forward Guidance. Section 2 gives an overview of the existing literature on Forward Guidance’s effectiveness. Section 3 offers an empirical analysis of the effect of Forward Guidance on inflation expectations. Finally, some brief concluding remarks are provided in section 4.

The complexity of Forward Guidance

In this section I provide an overview of the complexity of Forward Guidance. The different types and forms, different motives, the heterogenous beliefs surrounding Forward Guidance, the lift-off from the ELB and the Forward Guidance Puzzle are the topics covered in this section.

Types and forms

All communication by a central bank about its economic outlook and future policy path can in fact be labelled as Forward Guidance, but there is a distinction between explicit and implicit Forward Guidance. Explicit Forward Guidance is communication only through official statements and has been used extensively by the Federal Reserve since 2008 (Del Negro, Giannoni, & Patterson, 2012). Implicit Forward Guidance is all communication by central bank officials that provides information about future policy and/or economic outlook, for example speeches or unofficial statements. Even other policy tools, like QE, can be seen as some form of Forward Guidance. Bauer & Rudebusch (2013) present evidence of the so-called “Signalling Theory” of QE that suggests that when the central bank uses QE, it expresses its commitment to keep a lower policy interest rate in the future.

Furthermore, three forms of explicit Forward Guidance can be distinguished. Filardo & Hofmann (2014) have named these forms respectively qualitative, calendar-based and threshold-based (or state-threshold-based) Forward Guidance and describe them as follows. Forward Guidance is qualitative when “it does not provide detailed quantitative information about the path of the policy rate or the envisaged time frame (e.g. “the policy rate will be maintained for an extended period”)”

3 (Filardo & Hofmann, 2014, p.40). It is calendar-based when “the guidance applies to a clearly specified time horizon (e.g. “the policy rate will be kept at the current level for x years”)” (Filardo & Hofmann, 2014, p.40). The third form, threshold-based Forward Guidance, is used when “the guidance is linked to specific quantitative economic thresholds (e.g. “the policy rate will not be raised at least until the unemployment rate has fallen below y%”)” (Filardo & Hofmann, 2014, p.40). Filardo & Hofmann (2014) state that each type offers pros and cons. Qualitative Forward Guidance can be very vague, but at the same time it allows the central bank to have some more freedom in making decisions in the future and it does not force policy committee members to reach a consensus. The latter can be very important, because in many cases different policymakers have different opinions and the qualitative Forward Guidance allows them to capture these different opinions in one statement without having to reach a consensus on a specific date or threshold. Calendar-based Forward Guidance is more explicit and therefore also more binding, but it also expresses a greater commitment. Early termination or extension could harm the credibility of the central bank, because her policy could be seen as time inconsistent. Threshold-based Forward Guidance is a more conditional and complex form than the other two, as these thresholds often are based on the evolution of complex economic concepts, but it is less affected by possible time inconsistency.

Motives for Forward Guidance

Eggertsson (2008) states that the end of the Great Depression was caused by a shift in expectations about monetary policy in the future. As the policy actions of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt shifted the expectations from “contractionary” to “expansionary”, the expectations of higher future income and higher future inflation lowered real interest rates and raised permanent income, consequently stimulating aggregate demand.

Monetary policy steers the economy, and ultimately price-setting, by affecting intermediate and medium-term interest rates. These interests indeed shape the conditions most relevant for durable consumption and investment. The expectations theory suggests that longer-term interest rates reflect the expectations of short-term interest rates (which the central bank controls) and returns are equalised across the term structure (excluding term premia). Praet (2017) argues that because of this theory the central bank can effectively influence the decisions that matter the most for economic activity, not by changing the short-term interest rates, but by changing expectations about the future path of these interest rates. The longer-term interest rates tend to follow the shift in short-term interest rates in the same direction, when this new level of short-term interest rates is perceived as persistent. This statement gives Forward Guidance great value as a monetary policy tool.

4 Praet (2017) continues with explaining how market participants form their expectations and says that they do so by trying to recognise a pattern in the monetary policy decisions made by the central bank. As all these decisions together are the reflection of the strategy chosen by the central bank to respond to new shocks with and try to maintain a path of price stability and sustainable growth. Praet (2017) distinguishes two interlinked parts in the mechanism of how market participants expect future monetary policy: the interpretation of the response strategy of the policymakers and the perception of how the policy-makers asses the current and future economic conditions. Forward Guidance intervenes in both parts of this mechanism as it can have an Odyssean as well as a Delphic component (see infra for more explanation about these concepts).

Since market participants form their expectations based on previously shown central bank behaviour, Forward Guidance becomes more important in times of greater uncertainty and crisis. Because then it becomes impossible to form their expectations based on previously displayed behaviour, as these times ask for unprecedented measures, and the risk of misinterpretation of their policy becomes greater (Woodford, 2013). Woodford (2013) argues that in a period wherein the ELB is a binding constraint on conventional monetary policy tools, expectations about the policy after this period have an even greater effect on near-term aggregate demand and economic activity, than it would have in a period in which conventional tools would be available.

Haberis, Harrison & Waldron(2017) argue that the use of Forward Guidance at the ELB has two motives. The first one has nothing to do with stimulating the economy (although this could be a by-product) and is about making policy more effective by trying to get the expectations of market participants in line with the intentions of the policymakers. This could be seen as a clarification of the reaction function, which is useful in times with increased uncertainty like during the Great Recession. Second, the central bank tries to stimulate the economy by promising lower rates in the future and a deviation (rather than a clarification) from its reaction function.

The board of governors of the Federal Reserve System (2015) stated the following: “When central banks provide forward guidance, individuals and businesses will use this information in making decisions about spending and investments. Thus, forward guidance about future policy can influence financial and economic conditions today.” Woodford (2012) also declares that variables such as the level of the Federal Funds Rate (on which the FOMC ordinarily takes a decision during their regular meetings) are not of such a great importance when trying to influence economic decision such as spending, investing, hiring and price-setting. Expectations about future policy and economic outlook are of a much greater importance and a critical aspect of the way in which monetary policy decisions try to affect these economic decisions made by market participants. Expectations namely affect the longer-term real interest rates. The ability of Forward Guidance to change long-term interest rates depends on its ability to change the expectations of the path of short-term interest rates. This can be

5 done by changing this path by extending the horizon of the period concerned by its Forward Guidance. When the ELB becomes binding, this can only be done by extending the time that its policy rate will remain at this ELB (Woodford, 2012). The time-dependent Forward Guidance of the FOMC in 2008, when it changed ‘for some time’ to ‘for an extended period’ in its announcements, is a clear example of this extension of the horizon (Kool & Thornton,2015). This is why, even when a central bank is constrained by the ELB, it should still remain possible to develop an accommodative monetary policy stance for the economy. Theory even implies that expectations about the future should matter even more in a scenario like this (Woodford, 2012).

Woodford (2012) argues that Forward Guidance should be able to affect the expectations about the future monetary policy path for two reasons. First, because the intentions of a central bank are not always easy for people to understand and explicit unambiguous Forward Guidance should resolve this problem. This is especially important when policymakers are constrained by the ELB and want the effects of the expectations of a looser policy in the future to mitigate the effects of relatively high short-term real rates now. A second reason is that Forward Guidance facilitates a commitment towards her displayed policy. And what better way to do this than publicly stating this commitment in such a manner that it is almost impossible to ignore this commitment later when making decisions? Existing literature, such as Filardo & Hofmann (2014), states that commitment is one of the factors that makes Forward Guidance effective. The public must believe the central bank will not renege on her promises for Forward Guidance to have an impact. The case of the Bank of Canada’s announcement (see infra) in which the word ‘commitment’ is clearly mentioned a few times is evidence of this.

Other important factors of the effectiveness of Forward Guidance are clear communication to and interpretation by the public in a right way. Overly complex communication could cause different interpretations of the policy intentions and lead to continuous discussions with the public and media about its wording and technical details (Filardo & Hofmann, 2014). Besides this, there is also the risk that the public interprets the promise to keep policy interest rates lower in the future as a weak economic outlook from the central bank, instead of as an accommodative policy stance, and reduces instead of increases their spending and investments. Furthermore, Woodford (2012) argues that Forward Guidance of a central bank that regularly makes statements about her policy rate in the future has a less significant effect than when this Forward Guidance is given outside of a particular routine. An explanation for this is that these kinds of statements are considered to be more policy-intention

revealing. These kinds of statements are known to have a greater effect on the expectations of market

participants than statements that are considered to be more economic-outlook revealing. This is because market participants believe that policy decisions are made using superior information that only central banks have at their disposal. Woodford (2012) also states that central banks should be aware of the fact that policymakers should give thought to how they intend to approach policy

6 decisions in the future. So that the policy they want people to expect and anticipate can also be put in effect without reneging on their previously made commitments, while also focusing on how they can make this history-dependent decision-making visible to market participants. Otherwise the central banks’ credibility could be harmed, and future decisions would have a smaller impact, since market participants won’t give much credit and attention to monetary policy announcements.

Heterogenous beliefs

The FOMC has never been clear about the purpose of its Forward Guidance. It never told the public whether it was purely a transparency device or a monetary policy tool to display a more accommodative policy stance for the future (and hopefully achieve more accommodation today) (Plosser, 2014). This is an important element of the heterogeneous beliefs and views about policy announcements and the mixed results in our later discussion of the empirical evidence of Forward Guidance effectiveness in the existing literature.

When central bankers announce that they will keep the policy rate at the ELB longer than market participants would have anticipated, this can have two different effects. On the one hand, it could be interpreted as a monetary stimulus and lower the expectations of the actual policy rate. This lower rate stimulates economic activity and puts upward pressure on the inflation rate. On the other hand, it could be interpreted as negative news about the state of the economy and therefore lower economic activity (Andrade et al., 2019). Thus, how Forward Guidance is perceived by market participants is a very important factor for its effectiveness and the type of impact it makes.

Woodford (2012) also pointed out this uncertainty about the cause of the change in the future Federal Funds Rate forecast by the private sector. It could be because market participants believe that the central bank’s reaction function has changed (the goal of Forward Guidance), but it could also be because market participants believe that the central bank has superior information about the economic outlook that is expected to determine the monetary policy.

Campbell et al. (2012) builds further upon this finding of Woodford (2012). He introduced the terminology of Odyssean1 and Delphic2 Forward Guidance. Odyssean Forward Guidance publicly commits the policymakers to a future policy, while Delphic Forward Guidance merely displays forecasts of economic variables and likely future actions based on the central bank’s potentially superior information. Delphic Forward Guidance presumably would enhance the economic conditions by

1 Named after Odysseus who committed to staying on the ship by having himself bound to the mast. 2 Named after the classic oracle.

7 reducing the market participants’ uncertainty, while Odyssean Forward Guidance tries to do this by changing expectations in the desired way that fits its intended future policy (Andrade et al., 2019).

Praet (2017) describes Odyssean Forward Guidance as communication about the parameters of its reaction function and goals of its monetary policy. He says that it is Odyssean to the extent that this communication relates to the mandates and statutes of the central bank, as by communicating in relation to these mandates and statutes it commits itself to never neglect these. Delphic Forward Guidance is described by Praet (2017) as communication about the perception of the current and future economic conditions and reveals a conditional expected monetary policy path.

The challenge of Odyssean Forward Guidance for the central banks is to follow through with her earlier announced policy path (and let market participants believe that they will do so) and not fall in the trap of the earlier mentioned time-inconsistent Forward Guidance, even when all beneficial effects look absent because the economic conditions have changed and ask for a different approach now. Policymakers should not only look at the present circumstances and ignore all beneficial effects of the anticipation on past economic conditions. If there is a lack of a real enforcement mechanism to make sure that policymakers follow through, they completely rely on their reputation to make their commitment(s) credible (Campbell et al., 2012).

Andrade et al. (2019) argues that market participants can agree on the future path of the interest rate but disagree on the fact whether there will be extra accommodation by not immediately raising the policy interest rate from the ELB as soon as economic conditions would allow this. On the one hand, some people see the promise of low policy interest rates as a sign of a bad economic outlook, while on the other hand some other people see it as a promise for future accommodative monetary policy. Hence the Delphic agents believe in a bad economic outlook and spend less, while Odyssean agents in contrast believe in a better economic outlook and future accommodation and spend more. This heterogeneity in beliefs constrains the power of Forward Guidance at the ELB, even when all agents agree that the policy rate will remain at zero, because the different beliefs offset each other’s economic impact (Andrade et al., 2019). This party explains the evidence in the later discussion of the existing literature that Forward Guidance is powerful in lowering expected future interest rates but has a much smaller macroeconomic impact.

Solutions for the problems that these heterogeneous beliefs bring with them when a central bank uses Odyssean Forward Guidance are given by Andrade et al. (2019). One way is to make separate announcements about its future policy and its view on economic conditions. This should have a positive effect on the credibility, as it enhances the clarity of communication and shows a form of commitment. Woodford (2012) has a similar view: ex-post reneging on their policy stance would “cause an embarrassment” (to borrow his exact words) for the policymakers. Another way is regularly communicating its economic outlook and trying to let agents believe in a shorter ELB period than the

8 policy’s horizon, to raise their optimism about the future and increase economic activity today. These two methods are still easily vulnerable for being mistaken as Delphic. This is why the following option is probably the most effective. This is using QE as a commitment device towards providing the extra accommodation announced in the Forward Guidance, as “putting your money where your mouth is” (as Andrade et al. (2019) describes it) is a very effective way to increase your credibility as a central bank using Forward Guidance. This finding is in line with the so-called ‘Signalling Theory’ of QE mentioned earlier.

The lift-off

Woodford (2012) argues that the most desirable form of Forward Guidance during a period when the ELB is a binding constraint on conventional monetary policy is to communicate that the ELB will be maintained longer than necessary without making unconditional promises about the date on which this ‘lift-off’ from the lower bound will happen, since this completely depends on economic developments. Woodford (2012) cautions about the probability of misinterpretation of such policy. If, for example, this lift-off date is announced to move further into the future because of a weaker economic outlook, without implying a change of reaction function and intention to keep the policy rate low longer than necessary and market participants interpret this as a simple inference of the reaction function, this would have a contractionary effect. Because instead of the belief that real incomes will be greater as a consequence of keeping policy rates lower longer than necessary, market participants will fear a lower real income at that time than was expected prior to the announcement. Consequently, the people’s willingness to spend will decline instead of increase.

Akkaya et al. (2015) argues that all types of Forward Guidance are most effective when “lift-off” is near. Because this is when central banks’ policymakers are most uncomfortable to make additional commitments towards future accommodation and this has a great positive effect on the credibility of her possible commitments.

Eggertson & Woodford (2003) provide a theoretical formula based on the output gap and price level to decide the date for lift-off from the lower bound. The theoretical optimal criterion on which the formula is based is indeed also based on an optimal understanding of the public, which can be a problem when put into practice.

A central bank can also decide to start raising her policy rate when one or more criterions (thresholds) are met, instead of on a certain date. An example of this is the “7/3 Threshold Rule” proposed by President Charles Evans of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago and analysed in the work of Campbell et al. (2012). It is a threshold rule that ensured maintaining low interest rates when the

9 economy would start expanding, while also providing safeguards against developments that could jeopardize the Federal Reserve’s price stability mandate. This proposal states that it would maintain the policy rate at its lower bound until the unemployment rate would decrease under 7 percent and the expected medium-term inflation rate would rise above 3 percent. A statement that is easy to understand for the public and containes both parts of the legislative mandate of the Federal Reserve. It also still has a connection to the theory of Eggertson & Woodford (2003) since the unemployment rate can be seen as a proxy for the output gap. But it also misses an important factor of this optimal policy commitment, namely the promise to subsequently compensate for target misses caused by the binding lower bound. Campbell et al. (2012) provides empirical evidence for concluding that the risk of Odyssean Forward Guidance jeopardizing the price stability mandate of the Federal Reserve can be managed by using conditional Forward Guidance such as the “7/3 Threshold Rule”.

Woodford (2012) argues that a better form of this kind of threshold-based Forward Guidance is to use the trend of the pre-lower bound period as the threshold for a lift-off from this lower bound. As this should make clear that the policy rate will not immediately be taken from her lower bound as soon as the reaction function would allow this. This would give an incentive for market participants to belief in easier future monetary policy than first anticipated, consequently increasing the willingness to spend and ease financial conditions today. Woodford (2012) suggests that an unusual policy stance has more credibility when it uses a threshold that is based on a trend from before the lower bound was reached, since this makes market participants believe that these unconventional measures will not cause, for example, inflation to rise to extremely high levels and that the policy isn’t purely forward-looking. This period of maintaining the policy rate low longer than it normally would to alter market participants’ expectations of the policy rate and, consequently, short-term interest rates generally, and thus make Forward Guidance more effective (have a larger impact on long-term interest rates) was later called the ‘Woodford-period’ by Kool & Thornton (2015) among others.

Communicating a simple rule that relates the instrument of Forward Guidance (the duration of extra accommodation before lifting the policy rate from the ELB) to the ELB duration and the magnitude of the financial disruption, is what Bilbiie (2019) suggests in his work on optimal Forward Guidance using the following formula:

Half of (LT duration × disruption)

The length of the period of the extra monetary accommodation should be half as long as the length of the duration of the liquidity trap times the financial disruption. The latter is calculated as a ratio of the average natural rate of interest during the liquidity trap and during ‘normal times’. Of course, at the announcement at the beginning of the ELB period should the central bank only express its commitment

10 to this rule. When the liquidity trap is over, it can communicate the exact duration of extra accommodation until lift-off. After this, the central bank should return immediately to its optimal policy as if it was completely back to ‘normal times’ (Bilbiie, 2019). This Forward Guidance rule combines the best of the two worlds, by combining the advantages of time-contingent and state-contingent Forward Guidance. It is easy to communicate and understand, which has a positive effect on its credibility.

Evidence of the Forward Guidance’s influence on the expectations of market participants about lift-off from the ELB was given by Swanson & Williams (2012). They show that the Blue Chip Survey of Professional Forecasters’ median responses to the question how many quarters it would take until the FOMC would raise the federal funds rate target above 25 bp (the ELB at that time) shows that after the “for some time” announcement in 2008 the response jumped to 4 quarters and kept fluctuating between 3 and 4 for some time. After the “mid-2013” announcement in 2011 the response jumped to 7 or more and continued at that level. This implies a clear effect of the FOMC’s Forward Guidance on lift-off expectations and a belief of market participants in the credibility of the FOMC’s assessment and communication.

Forward Guidance Puzzle

The work of Eggertson & Woodford (2003) showed that promises about future interest rates can be very powerful in New Keynesian models. Monetary policy decisions are usually based on a particular rule or reaction function that indicates whether the policy interest rate should be raised or lowered. For example, the Taylor Rule (a widely-used policy rule) suggests a lowering or increase of the policy interest rate dependent on the levels of (expected) inflation and gross domestic product relative to their trend. An economic shock that causes the policy rate to hit the ELB can cause a lot of deflation and a deep recession according to the liquidity trap theory. But Eggertson & Woodford (2013) proclaims that making promises about keeping the policy rate at this lower bound longer than a normal Taylor Rule or any other reaction function would suggest, can resolve this negative economic impact by changing expectations of market participants and longer-term interest rates.

Carlstrom, Fuerst, & Paustian (2012), however, found that the workhorse model of Smets & Wouters (2007) would predict an explosion of inflation and output if it were announced that the ELB would be maintained for the coming eight to nine quarters. A period that is not unrealistic if you look at the Forward Guidance announcements of the Federal Reserve in the past. Del Negro et al. (2012) called this surprisingly large reaction the “Forward Guidance Puzzle” and argued that it resulted from many features of the New Keynesian DSGE models, especially the lack of discounting of future

11 economic outcomes. To counter the puzzle, Del Negro et al. (2012) proposed implementing a “perpetual youth structure” into the models, i.e. implementing a constant probability of the agent dying each period, to make policy announcements far in the future less impactful. This “perpetual youth structure” causes an increase in realism and results in letting statements about the future have a smaller effect than when it is assumed that agents have an infinite life.

Furthermore, McKay, Nakamura, & Steinsson (2016) argued that the base of the Forward Guidance Puzzle problem is the absence of income risk and borrowing constraints. Announcements about the current short rate or the short rate 5 years ahead, both had the same effect on current consumption. When adding borrowing constraints and an uninsurable income risk, the power of Forward Guidance substantially decreases as a consequence of this implemented precautionary savings effect.

New Keynesian models assume that market participants develop rational expectations and have common knowledge about the state of the economy and the relevant news when used to conduct research on the effectiveness of Forward Guidance. Therefore, it is assumed that not only everybody is aware and attentive of the Forward Guidance, but also that nobody doubts the awareness, attentiveness and ability to respond of the other agents. Consequently, there is no doubt surrounding the expectations of market participants about how inflation and income will adjust to Forward Guidance. Angeletos & Lian (2018) argue that by removing this assumption of common knowledge and perfect understanding of the beliefs and future actions of others and by thus introducing a higher-order uncertainty into these models, the Forward Guidance Puzzle mitigates.

Haberis, Harrison, & Waldron (2017) similarly stress the existence of a paradox hidden in the Forward Guidance Puzzle. These authors attribute the strong effect of the promise to keep interest rates low in the future on the current economic activity to two factors. On the one hand, a strong link between expected future policy rates and economic activity today. On the other hand, the belief of market participants that policymakers will not renege on this promise when the benefits of keeping the policy rate low decrease. The paradox says that the stronger the link in the first factor (the stronger the expectations channel), the less likely it is that market participants will believe the promise. This conflict is not considered in a New Keynesian Model. When you would relax this perfect credibility assumption, a Forward Guidance Puzzle possibly may no longer exist.

It is important to acknowledge the existence of this phenomenon when interpreting results of research on the effectiveness of Forward Guidance by a New Keynesian Model.

12

Literature review

This section contains the findings of the existing literature on the effect of Forward Guidance on the financial markets, as well as on macroeconomic variables and expectations.

Effect on financial markets and its expectations

“The effectiveness of changes in central-bank targets for overnight rates in affecting spending decisions (and, hence, ultimately pricing and employment decisions) is wholly dependent upon the impact of such actions upon other financial market prices, such as longer-term interest rates, equity prices, and exchange rates. These are plausibly linked to short-term interest rates most directly affected by central bank actions, but it is the expected future path of short-term rates over coming months and even years that should matter for the determination of these other asset prices… “(Woodford, 2001, p. 308)

Gurkaynak, Sack, & Swanson (2004 & 2005) introduced new terminology in the research on the effectiveness of Forward Guidance. They stated that every policy statement has two factors: the ‘Path Factor’ and the ‘Target Factor’. The target factor is equal to the change in the forecast for the current federal funds rate, while the path factor is equal to the change in the forecast for the federal funds rate in the future. If macroeconomic news, like FOMC statements, would have no effect on the financial market and expectations (which would make Forward Guidance useless), there should be no variation in either factor. If only the revelation of the current target rate would be relevant (which would also make Forward Guidance useless), then all variation should be caused by the target factor. Gurkaynak et al. (2004) found that the changes in asset prices caused by monetary policy announcements are not characterized by a single factor, but by the path and target factor.

A starting point for Gurkaynak et al. (2004) was a remarkable event that happened on January 28, 2004: the largest reactions of 2- and 5-year treasury yields in the latest 14 years were recorded. Even more remarkable was that this was caused by a monetary policy announcement in which the FOMC did not change its federal funds target rate, moreover market participants had even expected it to be this way, but only changed their language used in the announcement. So, it is more important to see what they said that day instead of what they did (compared to previous announcements). In this announcement they replaced the sentence “policy accommodation can be maintained for a considerable period” with “the Committee believes it can be patient in removing its policy accommodation”. This change in language was perceived by the financial markets as a sign of sooner monetary tightening than they had previously expected (Gurkaynak et al., 2004). Gurkaynak et al.

13 (2004) found the following results. A 1 percent tightening in the federal funds rate (target factor), ceteris paribus, causes a decline of 4.3% in the S&P500 index. 2-, 5- and 10-years Treasury yields increased with 47, 27 and 12 basis points (bp), respectively. The path factor has a greater impact on the long-term yields. A 1 percent innovation of the factor leads to an increase of 5- and 10-years Treasury yields with 36 and 27 bp, respectively. Gurkaynak et al. (2005) found that regarding variation in medium- and long-term Treasury yields, the path factor explains three to ten times more than the target factor, as the target factor has greater impact on shorter-term interest rates. An explanation for this is that FOMC statements also convey information about medium-and longer-term economic outlook, besides their information about future policy. When looking at the effects on stock prices, the surprising result is that here the path factor has a much smaller effect on its changes than the target factor. Gurkaynak et al. (2003) explains this: it is known that policy announcements can have a great positive path factor and that Treasury yields react substantially to good news about future macroeconomic conditions.

Campbell et al. (2012) later extended the work of Gurkaynak et al. (2004 & 2005) and confirmed these results. They also found that the path factor had significant effects on the financial market, more specifically on corporate bond yields (this was in line with the findings of Gürkaynak et al. (2005): they had discovered significant impacts of the path factor on Treasury yields). Gurkaynak et al.’s (2005) research on the effect of Forward Guidance on futures contract prices showed that despite the seemingly great complexity of monetary policy, the target and path factor accounts for 90% of the changes in these futures contract prices, meaning that FOMC statements have a significant impact on the expectations of market participants about future policy through changing its current federal funds rate as well as the statement itself and the (change of) language used in this statement. The results of Campbell et al. (2012) show that Forward Guidance had a large effect on asset prices in the pre-crisis period (1990-2007).

Andrade et al. (2019) in his turn continued the work of Campbell et al. (2012) for more recent data. They conducted research on the responses of the Survey for Professional Forecasters (SPF)3 during three important periods of Forward Guidance at the Federal Reserve. Their “open-ended” period at the ELB, their “date-based” period and “state-based” period during 2008Q4-2011Q2, 2011Q3-2012Q3 and 2012Q4-2013Q2, respectively. One of their findings was that date-based Forward Guidance heavily decreased the disagreement about future short-term and medium-term (1 and 2 years) interest rates to an all-time-low. During this period, optimists (people who had revisions of inflation and consumption growth above the average across all forecasters) as well as pessimists (people who had revision of inflation and consumption growth below average) forecasted a decline of

14 interest rates. Optimists believed that the lower interest rates implied a more accommodative policy stance, while pessimists saw it as a sign of weak economic conditions. This ambiguity in views about the commitment ability and motivation of the central bank is a peculiar outcome of times where the policy rate is at the ELB, because only in these times the central bank has an incentive to deviate from her usual reaction function.

Akkaya, Gurkaynak, Kısacıkoğlu, & Wright (2015) added a new element to the monetary policy announcements besides the target and path factor: “the uncertainty surprise factor”. Since monetary policy announcements not only affect the expectations about the future path of policy, but also the uncertainty surrounding the expectations of this path. This surprise is measured by the change in options-implied volatility of futures contracts. Akkaya et al. (2015) investigated the effects of the path factor and this uncertainty surprise factor on asset prices (S&P returns and dollar exchange rates). The target factor was not included since the sample was from a period in which the ELB had become binding. These two factors were estimated to both have a negative effect on stock prices, so the equity market is boosted by a lower futures-implied path and less options-implied volatility of futures contracts. On the other hand, path surprises (a lower futures-implied path) seem to imply a weaker dollar, while the uncertainty factor doesn’t have a significant effect on exchange rates. Other findings were that Forward Guidance affects yields by changing the expected future path of policy as well as by changing term premia.

Altavilla et al. (2019) conducted research on asset price and yield changes on monetary policy event days in the Euro Area. With the help of their Euro Area-Monetary Policy Database with intraday data and thanks to the special process of monetary policy announcements used in the Euro Area4 they discovered that target factor surprises mainly affect the short end of the yield curve, while Forward Guidance is the main driver of changes in the medium- to longer-term (2 to 5 years) end of the yield curve. Altavilla et al. (2019) noted that results of research on the effect of Forward Guidance on stock prices can produce insignificant results due to the heterogenous nature of how market participants perceive the monetary policy statements. As earlier mentioned, the promise to keep policy interest rates lower in the future can be perceived as future accommodative policy or as a worse economic outlook than previously anticipated. Causing stock prices to rise or decline, respectively.

Moessner (2015) states that the use of explicit Forward Guidance by the FOMC had a significant effect on real yields of 2 to 5 years ahead. This effect was strengthened by the use of QE measures, but more important is that even without this signalling channel of QE, Forward Guidance already had an average effect of 17 bp per announcement on real yields.

4 Thanks to the distinction between a press release and press conference, it is much easier to distinguish the

15 To give an example of when Forward Guidance did give the market participants a belief of change in the central bank’s reaction function, I present the case study of Woodford (2012). On April 21, 2009 the Bank of Canada announced the following:

“The Bank of Canada today announced that it is lowering its target for the overnight rate by one-quarter of a percentage point to 1/4 per cent, which the Bank judges to be the ELB for that rate.... With monetary policy now operating at the ELB for the overnight policy rate, it is appropriate to provide more explicit guidance than is usual regarding its future path so as to influence rates at longer maturities. Conditional on the outlook for inflation, the target overnight rate can be expected to remain at its current level until the end of the second quarter of 2010 in order to achieve the inflation target.”

This is a clear case of using explicit Forward Guidance. The statement had an almost instantaneous effect on expectations about the future path of the policy rate. This effect is displayed in attachment 2.1 by the change in Overnight Interest-rate Swap (OIS) contracts. Woodford (2012) notices that all OIS rates for all maturities fall significantly after the announcement. Two maybe even more important effects are that the longer maturities fall more than the shorter ones and the results also flatten out. This implies that expectations for early 2010 fall even more than nearer short-term ones and that uncertainty about the upcoming path for this year has significantly been reduced (which then also reduces the term premium). Besides this, Woodford (2012) also discovered that the forward rates implied by the term structure of OIS rates for the Canadian dollar and the US dollar did not move in the same way following the announcement. The forward rate for the Canadian dollar drops by 10 to 15 bp, while the one for the US dollar does not have a similar decline. This reflects a change in expectations about the Bank of Canada’s future policy, instead of a change in economic outlook (which would also affect the US). One could conclude that this was an example of interest-rate expectations being changed by explicit Forward Guidance with a clearly communicated commitment and a belief of market participants in change of reaction function5.

Other empirical evidence given by Woodford (2012) concerns FOMC announcements since reaching the ELB on December 16, 2008. The communication back then was that this level of federal funds rate target would be maintained “for some time.” In its statement on March 18, 2009 this was changed to “for an extended period.” On August 9, 2011 a more drastic approach was adopted by stating: “The Committee currently anticipates that economic conditions ... are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels of the federal funds rate at least through mid-2013.” Finally, on January 25, 2012 it was even further strengthened to “… at least through late 2014.” Each of these statements caused an immediate decline in OIS rates and thus led to a lower expected path of the federal funds

16 rate. But the most meaningful results were those from the last two announcements, since in these announcements, unlike the other two, the statements did not contain any news about changing the current federal funds rate target (as in 2008) or other important policy changes (as in 2009). Attachments 2.2 and 2.3 show the intraday data of these statements and show an immediate drop of OIS rates, even though the current target remained unchanged. This can be interpreted as a change in expectations about the future path of the funds rate, resulting from explicit Forward Guidance. Moreover, Woodford (2012) also showed the effect of Forward Guidance surprises on expectations by indicating that in attachments 2.2 and 2.3 the OIS rates with maturities of which the time span was already covered in the previous announcement, weren’t affected by the strengthening of the new statements.

Since February 2007 the Swedish Riksbank has been publishing forecasts of their future policy rate path. This data is particularly interesting because it has since then also been announcing on more than one occasion that its policy rate would remain fixed for a specific period of time. On April 21, 2009 the Swedish Riksbank implemented a cut of the policy rate to 50 bp and announced that “the repo rate is expected to remain at a low level until the beginning of 2011” together with a monetary policy update displayed in attachment 2.4. The intention of lowering the expected path rates, i.e. to lower longer-term interest rates, did not materialize. One reason for this is that market participants had expected an even larger decrease of the policy rate. Though the main reason seems to have been that market participants had made their own ‘version’ of the Riksbank’s Forward Guidance. First of all, they did not believe that the policy rate would fall to 50 bp, since this had never happened before. Second, the Riksbank did not treat the 50 bp level as her ELB clearly enough in its announcement, while she probably should have done so, as Filardo & Hofmann (2014) among others state that clear communication is an important factor for Forward Guidance effectiveness. The announcement did not mention anything about a lower bound and even mentioned “some probability of further cuts in the future.” In contrast, they did announce that the policy rate was about to reach her lower limit and that traditional monetary policy wasn’t an option anymore and even cautioned that this could have negative effects on the financial markets. But it is still easy to see how all this could have been interpreted as an intention to not lower the policy rate below 50 bp. This is a clear example of the importance of credibility and understandable communication when using Forward Guidance. Perhaps it did also not have the desired effect, because they did not announce how they would make monetary policy decisions in the future, which made them even less credible (Svensson, 2010).

Del Negro et al. (2012) found during their research on the “Forward Guidance Puzzle” that Forward Guidance has a significant influence on the financial market. Nominal rates declined substantially after the August 2011 and January 2012 announcements. Treasury yields, risk premia and exchange rates were all significantly affected by the announcements during the days following the

17 different statements. Although not always in the same directions as a consequence of changing language and its following heterogenous views (Odyssean and Delphic) of market participants. The QE measures in the last episode are also a factor in these sometimes-different results regarding the same assets. Although the Forward Guidance in all three events seems very much the same, the subtle differences and changes in language (together with the presence of QE) cause very different reactions on the financial markets. But when looking at these differences together with the changes in macroeconomic expectations of each event, they become much more understandable.

Kool &Thornton (2015) contributes to the existing literature by investigating the effectiveness of Forward Guidance from the central banks of New Zealand, Norway, Sweden and the United States. They investigated whether the short-term and long-term interest rates were more predictable and whether there was in increased convergence in the forecasts about these interest rates among individuals. The results provided mixed support for the use of Forward Guidance and its efficacy. They find that only for New Zealand forecasting of the short-term interest rate improved, but evidence for long-term rates was weak. When they used samples of countries that didn’t use Forward Guidance at that time as a benchmark, the results were even less definitive. The most significant result in favour of the use of Forward Guidance was a significant and great convergence of forecasts in New Zealand, Norway and Sweden.

Effect on the real economy and its expectations

Campbell et al. (2012) showed that changes in expectations about macroeconomic variables in a pre-crisis period (1990-2007) were significantly affected by Forward Guidance as the short-term expectations were dominated by the target factor, but the path factor accounted mostly for the changes in longer-term expectations. With significance at the 5% level, the forecasts up to 4 quarters ahead of the unemployment rate and inflation rate were affected to an extent of approximately 25 bp. The results of the sample after the Financial Crisis (2007-2011), although not statistically significant anymore, were in line with the results of the pre-crisis sample.

Evans & Justiniano (2012) are both advocates of the in the previous chapter mentioned “7/3 Rule” and did research and the effects of the “late 2014” statement made in 2012 that said that the FOMC “currently anticipates that economic conditions … are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate at least through late 2014”. According to Evans & Justiniano (2012) this statement could be interpreted by the public as Odyssean or Delphic Forward Guidance. Their results, using the Chicago Fed’s New Keynesian DSGE model for forecasting, showed that the “late-2014” statement increased core inflation very close to the inflation objective. However, the unemployment

18 rate decreased substantially, but still seemed fairly high relative to any mandated goal of sustainable employment made by the FOMC. In their forecasts the inflation or unemployment level didn’t breach any of the threshold of the “7/3 Rule”, arguing that this rule is capable of providing additional monetary policy accommodation using Odyssean Forward Guidance.

Moessner (2015) did research on the effect of Forward Guidance on forward breakeven inflation rates derived from TIPS and conventional US Treasury bonds to measure the change of inflation expectations caused by Forward Guidance on horizons from 2 to 10 years. The result was a small, but statistically significant at the 5% level, effect of on average 6 to 7 bp on horizons from 6 to 8 years per announcement. This was strengthened to 5 to 10 bp on average in periods with QE announcements.

After the financial crisis in 2008, the FOMC has tried to stimulate the economy by giving information about their economic outlook, as well as by promising future accommodative monetary policy. Since then every stimulatory effect caused by the information about their economic outlook has ben overshadowed by the stimulatory effects caused by the promise of accommodative monetary policy in the future. Consumer and firms reacted heavily to this promise and, leading to an increasing aggregate demand and inflationary pressure (Smith & Becker ,2015). Smith & Becker (2015) show that Forward Guidance containing these promises about future accommodative monetary policy had effects on macroeconomic variables like growth in payrolls and changes in PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditures) price level similar to effects caused by changes in the federal funds rate in previous periods without Forward Guidance and the presence of the ELB. A remarkable finding, since Forward Guidance simultaneously had a much smaller effect on interest rates compared to previously measured effects caused by changes in the federal funds rate. Smith & Becker (2015) gives three explanations for this paradox. First, Forward Guidance alters mainly long-term expected rates and less so near-term rates. Second, Forward Guidance changes interest rates expectations at a much further horizon than conventional measures do. Third, the Forward Guidance effects were strengthened by QE measures, as the expansion of a central bank’s balance sheet signals the commitment to maintain a low policy rate target in the future. Using a sample from 2008-2014 Smith & Becker (2015) discovered Forward Guidance shocks had a peak effect on payroll changes and inflation between 18 to 24 months. Inflation could increase with 0.1 percent in this period following a Forward Guidance shock. Forward Guidance also affects expectations on a much longer horizon than conventional monetary policy measures do, and it decreases the slope of the expected funds rate curve. This means that the expected funds rate falls more in the longer-term than in the nearer term. Conventional measures are known to do the opposite and increase this curve.

The changes in expectations of macroeconomic variables differ substantially across events in the work of Del Negro et al. (2012). They investigated three different monetary policy announcement

19 days in 2011/12 and their effect on the expectations about GDP growth and CPI Inflation. The difference in results and the statistically insignificance make sense when keeping the existence of Odyssean and Delphic views in mind and the different language used in the three statements. The August 2011 lowered expectations about GDP growth, while the September 2012 statement raised GDP growth expectations. Del Negro et al. (2012) states that the statement in August 2011 was interpreted as Delphic and was seen as revealing negative news about the economic outlook, while the September 2012 statement was interpreted as Odyssean and seen as a commitment to more monetary accommodation. Their conclusion was that Forward Guidance had, on average, a positive effect on inflation and GDP.

Empirical Analysis

Introduction

The previous section provides evidence that financial markets react significantly to monetary policy announcements and its Forward Guidance. Most of the evidence is from the US and the Forward Guidance implemented by the Federal Reserve. Altavilla et al. (2019), however, show that these findings also apply to the Eurozone and the Forward Guidance provided by the European Central Bank (ECB). But the research on the effects on the real economy and its expectations is much more limited, hence in this analysis I focus on the effect on the real economy, in particular the inflation expectations of market participants.

A commitment of the central bank to create inflation in the future can be a powerful way of stimulating economic activity during a period of a binding ELB (Eggertson & Woodford, 2003). Furthermore, Forward Guidance at the ELB, if credible and monetary policy accommodation is expected, can increase aggregate consumption. However, there is also the risk that market participants would interpret this future accommodative monetary policy stance as an indicator of a current weak economy, which would decrease inflation expectations and aggregate consumption (Wiederholt, 2015). D’Acunto, Hoang & Weber (2015) also found a positive relation between inflation expectations and the willingness to buy durable consumer goods.

So, the ultimate goal of this analysis is to assess the ability of the ECB’s Forward Guidance to increase inflation expectations by letting market participants believe in additional future monetary accommodation when policy rates have hit the ELB. To the best of my knowledge, the research on the effect of Forward Guidance on inflation expectations and in particular on Breakeven Inflation rates (BEIR) is very limited.

20 The ECB tries to achieve price stability by using conventional and unconventional monetary policy tools to steer financial markets and influence employment and the level of activity in the Eurozone. As mentioned before, Forward Guidance has been widely used since the Financial Crisis of 2008-2009 but it has gained importance since 2016 as the ECB’s policy rate, known as the rate on main refinancing operations (MRO), has been put at 0.00% since March 16, 2016. As the conventional measures became less useful then, the focus shifted towards unconventional measures like Forward Guidance and QE.

Identification approach

Monetary Policy Announcements by the ECB follow a particular procedure. Information about their decisions regarding the interest rates and information about their economic outlook and policy are given at two separate moments. On the day of a monetary policy announcement, the ECB publishes a press release at 13.45 Central European Time (CET) and gives a press conference later that day at 14.30 CET. The press release provides a brief summary of the policy decisions made by the ECB Governing Council without any detailed explanation. Up to March 2016 the press release mentioned only the decisions about the policy rates and whether further measures would be announced during the press conference (without saying what these measures were). Since March 2016 the press release also contains the content of the decisions about non-conventional measures, but still without any detailed explanation. The press conference always starts with an ‘Introductory Statement’, which is often perceived by market participants as revealing the future path of monetary policy (Altavilla et al., 2019). The rest of the press conference is about giving explanation about her decisions and ends with a question-and-answer session.

Altavilla et al. (2019) shows that this procedure made it possible to easily distinguish the different factors that have an effect on financial markets. In the press release window, changes in yields and stock prices are mainly caused by the target factor, which reflect the changes caused by the change in policy target rate. This target factor is almost completely absent in the press conference, since there is nothing new revealed about the policy target rate, that wasn’t already revealed in the press release, in this press conference. The changes in yields and stock prices during the press conference window are instead mainly caused by the path or Forward Guidance factor, together with QE. Note that the fact that these two factors, Forward Guidance and QE, are both in the press conference window does not matter when making conclusions about the press conference’s effect. As the ‘Signalling Theory’ (Bauer & Rudebusch, 2014) suggests that QE is simply a commitment device for Forward Guidance, one could follow the theory that there is no need to separate these two factors

21 when making conclusions about the effect of Forward Guidance and that it suffices to acknowledge that QE has a stimulating effect on the effectiveness of Forward Guidance.

Following the empirical evidence from Altavilla et al. (2019) and the reasoning in Bauer & Rudebusch (2014), we make the assumption in our empirical analysis outlined below that all changes in inflation expectations following the Governing Council’s meetings are caused by Forward Guidance. The sample period runs from the end of 2016 until the end of 2019 in which 24 official monetary policy announcements have been made by the ECB. Throughout this whole period, the ELB was binding, which made all the press releases very much the same. There were no surprises regarding the policy interest rate changes, since these all stayed the same during this whole period. The fact that the press releases did not have any significant surprises, consequently made the press conference and thus the Forward Guidance more important. Our assumptions are therefore consistent with Akkaya et al.’s (2015) argument that a target factor is completely absent during a period at which the policy rate is at its ELB. So, even though using daily data, which makes it not possible to distinguish between the target and Forward Guidance factor, the presence of a binding ELB during the whole sample period lets us assume that all changes were caused by the Forward Guidance factor.

Method

The goal is to assess whether the monetary policy announcements in the sample period had any significant effect on the inflation expectations using an event-study methodology. Data from Germany is used for two reasons. The first is that my measure of inflation expectations, forward BEIR, is simply not available to me at the level of the Eurozone. Second, Winkelmann, Bibinger & Linzert (2016) and Altavilla et al. (2019) among others have proven that German data is a good and correct proxy to use to examine the effects of monetary policy announcements and Forward Guidance from the ECB, since it is a core country with a strong economy and stable government. We start from a daily (business days) sample running from December 15, 2016 until December 31, 2019.6 The econometric model can be represented by the following equation:

𝑦𝑡𝑚− 𝑦𝑡−1𝑚 = 𝑐 + 𝑎1∗ 𝐷(𝑑𝑡) + 𝑎2∗ 𝐷(𝑑𝑡+1) + 𝑎3∗ 𝐷(𝑑𝑡+2) + 𝑎4∗ 𝐷(𝑢𝑡) + ∑(𝑏𝑗 11

𝑗=1

∗ 𝑆𝑢𝑟𝑝𝑟𝑖𝑠𝑒𝑡,𝑗) + 𝜀𝑡