FINANCIAL

PERFORMANCE

EVALUATION OF COOPERATIVES AND

INVESTOR OWNED FIRMS IN BELGIUM.

Word count: <16.561>

Student number : 01601645

Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Jos Meir

Master’s Dissertation submitted to obtain the degree of:

Master in Business Economics: Corporate Finance

Academic year: 2019-2020i

Confidentiality Agreement

PERMISSION

I declare that the content of this Master’s Dissertation may be consulted and/or reproduced, provided that the source is referenced.

ii

Content

Confidentiality Agreement ... i Abbreviations ... iv List of tables ... v List of images ... v Abstract ... vi Preface ... vi 1. Introduction ... 1 2. Definition of a cooperative ... 2 2.1. Previous literature ... 2 2.2. ICA ... 3 3. Types of cooperatives ... 5 3.1. Enterprise cooperatives ... 5 3.2. Worker cooperatives ... 63.3. Consumer cooperatives and Community cooperatives ... 7

3.3.1. The consumer cooperative ... 7

3.3.2. Community cooperatives ... 8 3.4. Multi-stakeholders cooperatives... 8 3.4.1. Stakeholders ... 8 3.4.2. Stakeholder theory ... 9 3.4.3. Multi-stakeholder cooperatives ... 9 3.5. Social enterprises ... 10

3.6. The European Cooperative Society (SCE) ... 11

4. The cooperative history until today ... 12

4.1. Establishment of the Cooperative movement ... 12

4.2. The cooperative history in Belgium ... 13

4.3. The current legislation on cooperatives ... 15

5. Comparison with other organisation forms ... 15

5.1. Other cooperative forms ... 15

5.1.1. Partnership ... 16

5.1.2. A multi-stakeholder initiative ... 16

5.1.3. Non-profit organisation ... 16

5.2. IOF ... 17

5.3. Comparison cooperative with IOF in previous literature ... 17

6. Research ... 24

iii

6.1.1. Profitability ... 25

6.1.2. Leverage ... 25

6.1.3. Solvency ... 25

6.1.4. Liquidity ... 26

6.1.5. Expected relationship ratios ... 26

6.2. Data ... 26

6.3. Ratio analysis ... 29

6.3.1. Calculation of the ratios ... 29

6.3.2. Tests for comparing the financial performance ... 31

6.3.3. Descriptive statistics ... 32

6.3.4. Application of the Mann-Whitney U test ... 32

6.3.5. Interpretation of the output ... 36

6.3.6. General benchmarks for the financial ratios ... 37

7. Conclusion ... 38

8. Theoretical and practical contributions ... 39

8.1. The theoretical contributions ... 39

8.2. The practical contributions... 40

9. Limitations ... 40

10. Sources ... 42

11. Appendix ... 50

11.1. Table 6: Nace-Bel Classification ... 50

11.2. Table 8: Normality check (the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) ... 52

iv

Abbreviations

IOF = investor owned firms

ICA = International Co-operative Alliance

USDA = United States Department of Agricutlutre CVBA = Cooperative company with limited liability CVOA = Cooperative company with unlimited liability

CVOHA = Cooperative company with unlimited, joint and several liability BV(BA) = Limited liability company (Ltd.)

CVA = Limited partnership with share capital NV = Public limited company (PLC)

SO = Social purpose

VSO = Company with social purpose MSIs = Multi-stakeholder initatives COOP = Cooperative

v

List of tables

Table 1: Characteristics of the CVBA and CVO(H)A

Table 2: Financial ratio comparison between IOFs and Cooperatives

Table 3: Comparison of cooperatives and IOFs in the fruit and vegetable and the dairy industry Table 4: Comparison of financial ratios between cooperatives and IOFs in the dairy industry Table 5: Expected relationships on the researched ratios

Table 6: NaceBel Classification Table 7: Calculation researched ratios

Table 8: Normality check: the Kolmogorov-Smirnovtest

Table 9: T-test for equality of means (and the Levene’s test for equality of variances) Table 10: Median values of calculated ratios

Table 11: Output Mann-Whitney U test

Table 12: Direction and significance levels of the deviation found between IOFs and cooperatives

List of images

Image 1: Conventional business Image 2: worker cooperative Image 3: The stakeholder model Image 4: Spectrum of Practitioners

vi

Abstract

This study researches the potential differences in financial performance between IOFs (investor owned firms) and cooperatives. Using a list of recognised cooperatives by the Belgian government from 2019, a sample of data for 462 cooperatives is formed. These companies were mostly active in agriculture, forestry and fishing, wholesale and retail trade (including repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles), professional, scientific and technical activities, and administrative and support service activities. A sample of 462 IOFs was created, matched on industry activity and balance sheet totals. Both where compared on the performance criteria: profitability, liquidity, leverage and solvency. Cooperatives perform worse on profitability and similar or worse on solvability. The liquidity position of cooperatives is similar or better compared to IOFs, but this is not true for every separate industry. On the leverage of the companies, no conclusive results were found.

Preface

This master’s dissertation was written in the period in which the pandemic Covid-19 affected the economy. However, in this desertation, only data from 2018 and a list of companies constructed in 2019 were used. None of the research used in the literature review or data used in the research has been affected by this pandemic. Thus, this master’s dissertation and its results were not influenced by this situation.

I would like to thank Frédéric Dufays, assistant professor from the department of Work and Organsiation Studies from the KuLeuven, for helping me with looking into possible research questions concerning financial performance of cooperatives, and for assisting me in the literature review done on this topic. I would also like to thank Bart Van Gysel from Febecoop and Alain Schovaert from Coopkracht for taking the time to provide me with information about cooperatives in general and information about the working of cooperatives in Begium. Lastly, I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Jos Meir, active in the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration at the UGent, for the assistance troughout this whole process.

1

1. Introduction

Belgian corporate law was reformed in 2019 (Xerius, n.d.) to, among other things, ensure that the flexibility previously exclusive to cooperatives, is now also granted to the organisational form BV (Bruloot, De Wulf, & Maresceau, 2018). According to Bruloot et al., this adjustment allows the cooperation to keep their recognition in return for compliance with certain norms. The draft bill, which establishes the code of companies and associations and which also contains various clauses, does indeed state that the goal of this reform is to give the cooperative organisation form their original individuality, being their cooperative mindset, back (Draft bill concerning het wetboek van vennootschappen en verenigingen en houdende diverse bepalingen).

In the past year, initiatives such as Luminus Wind Together, North Sea Wind and Eco2050 have come in the news frequently (Vermorgen, 2019; Steel, 2019; Adriaen, 2019). These are all typical examples of a certain organisational form, namely the multi-stakeholder cooperative. All the corporations named above are initiatives that collect money which is invested in wind energy (Luminus, n.d.; North Sea Wind, n.d.; Eco2050, n.d.). These organisations aim to create sustainable energy sources with the financial help of Belgian citizens.

Both Luminus Wind Together and North Sea Wind are initiatives that are founded by IOFs (EDF Luminus Wind Together, 2018; North Sea Wind, 2019). Luminus Wind Together is founded by Luminus, Windvision windfarm Leuze-en-Hainaut and Windfarm Bièvre (EDF Luminus Wind Together, 2018). North Sea Wind is founded by Parkwind, Colruyt, Korys Investments and PMV (North Sea Wind, 2019). This made us question as to why these companies did not see these initiatives as an investment project, instead choosing to found a separate company with a different legal statue, being the cooperative statute. Both founding entities could have raised money from citizens in another way, without founding a cooperative.

Looking closer into the subject of cooperatives, a debate came to light. Willems (2016) argues that these IOFs found cooperatives because it is an easily founded corporate structure for raising money, while the structure can also be easily made undone. From the 2019 reform onwards, this flexibility will be granted to BV’s as well. However, Willems (2016) says that these IOFs also opt to found cooperatives in order to attract more investments from citizens.

If IOFs believe that the cooperative statute is a better fit for raising money because of its attractiveness, this begs the questions whether this attractiveness also has an influence on the financial performance of such a cooperative. This brought us to the research question of this paper: How do cooperatives perform, measured by financial ratios, compared to IOFs in Belgium?

2 By looking into the profitability, leverage, liquidity and solvency ratios of cooperatives and IOFs, this research will try to provide insight in the underlying differences of the cooperative mindset and look into the financial performance differences that exist between these cooperatives and the IOFs.

2. Definition of a cooperative

2.1. Previous literature

Soboh, Lansink, Giesen and van Dijk (2009) define a cooperative as an organisation that is user-owned and -controlled and in which the owners benefit in proportion to their use. Because the members own and control at the same time, they can decide what happens with assets, are entitled to the net income, and bear the risks, all at the same time (Soboh, Lansink, Giesen, & van Dijk, 2009). They state that the objective of a cooperation is to create stability and optimal growth conditions.

Soboh et al. (2009) did an extensive literature review on agricultural marketing cooperatives and found that most cooperatives try to do one or more of the following: pay high prices to members (maximise the profit of the members), pay dividends (maximise return to patronage), maximise the profit of the organisation, maximise the turnover, and maximise each party’s proportion of the profit. They say that “cooperatives are successful if they provide service to their members in excess of what they can achieve individually or outside of the cooperative” (Soboh et al., 2009).

Sosnick (as cited in Soboh et al., 2009) says that there are three forms of cooperatives that are traditionally recognised in literature. These are “vertical integration of otherwise autonomous firms”, “independent business enterprises” and “coalition of firms”. The first two forms assign one objective to the cooperative, while the last forms assign multiple objectives to the cooperative (Sosnick, as cited in Soboh et al., 2009). He says that the objective assigned to “vertical integration of otherwise autonomous firms” is to manage a marketing program for the members and the objective assigned to the “independent business enterprises” is maximising the benefit to the owners. Garoyan (1983) argues that all of these concepts are true and useful. However, none of these concepts give a complete representation. Sosnick (as cited in Garoyan, 1983) argues that combining these concepts does not provide a complete representation either.

Parliament, Lerman and Fulton (1990) state that cooperatives are organisations that are owned by their members and whose goal it is to serve these members. They state that a noteworthy characteristic is that the cooperative divides profits according to the patronage (for example the amount that you purchased) instead of according to the contribution of capital. They say that “In addition to the business activity, the cooperation also provides goods and services for which no market values are available”, for example member education (Parliament, Lerman, & Fulton, 1990).

3 Helmberger and Hoos (1962) say that microeconomic theory splits economic agents into 3 categories: consumers, firms and resources. However, this fails to classify the cooperative association correctly (Helmberger & Hoos, 1962). They say that a broader interpretation within organisational theory is more appropriate when looking at cooperatives.

Fairbairn, Bold, Fulton, Ketilson and Ish (as cited in Majee, & Hoyt, 2011) define cooperatives as “associations of people who have combined their resources of capital and labor to capture greater or different benefits from an enterprise than if the business were undertaken individually”.

2.2. ICA

The international Co-operative Alliance, also called ICA, is a non-governemental organisation that was founded in 1895 (ICA,n.d.). ICA (n.d.) “unites, represents and serves cooperatives worldwide” and they have 1.2 bilion members in their community. Currently, ICA has 312 member organisations, of which 98 are located in America, 67 in Europe, 36 in Africa and 108 in Asia-Pacific (ICA, n.d.). The mission of ICA is to “advocate the interests and success of cooperatives, providing a global voice and forum for knowledge, expertise and co-ordinated action” (ICA, n.d.). Advocating the cooperatives’ interests and succes mainly happens through efforts to establish a political, legal and regulatory environment that is supportive of these companies, and that enables them to fulfill their goals (ICA, n.d.).

The international Co-operative Alliance defines a cooperative as follows: “A cooperative is an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprise” (ICA, n.d.). They also describe cooperatives as “enterprises based on values and principles” and they argue that the main priority is fairness and equality (ICA,n.d.).

Cera points out that, in the mentioned ICA definition of a cooperative, it seems that members have at least three relationships with the cooperative organisation. According to Cera, the first relationship members have with the company is of a transactional nature: the members are the users (client/supplier/employee/citizen) of the services of the organisation. In other words, the members are the people that have a certain need, which is fulfilled by the company. The second relationship mentioned by Cera is the investment relationship. The members are not only the users of the services, they also provide the capital necessary to found the company. Finally, the third relationship between member and organisation is one of control: the members are both managing the company, and controlling what is happening in the company (Cera, n.d.). Barton (as cited by Cera, n.d.) speaks of a unique ‘user-benefit, user-owned, user-control’ organisational model. According to Cera, this makes sure that there is a focus on goals maximalisation, namely providing the shareholders with the best service possible (Cera, n.d.).

4 ICA also provides 7 basic principles of cooperatives . These principles are the following:

1. volutary and open membership

Cooperatives are voluntary organisations, open to all persons able to use their services and willing to accept the responsibilities of membership, without gender, social, racial, political or religious discrimination.

2. democratic member control

Cooperatives are democratic organisations controlled by their members, who actively participate in setting their policies and making decisions. Men and women serving as elected representatives are accountable to the membership. In primary cooperatives members have equal voting rights (one member, one vote) and cooperatives at other levels are also organised in a democratic manner.

3. member economic participation

Members contribute equitably to, and democratically control, the capital of their cooperative. At least part of that capital is usually the common property of the cooperative. Members usually receive limited compensation, if any, on capital subscribed as a condition of membership. Members allocate surpluses for any or all of the following purposes: developing their cooperative, possibly by setting up reserves, part of which at least would be indivisible; benefiting members in proportion to their transactions with the cooperative; and supporting other activities approved by the membership.

4. autonomy and independence

Cooperatives are autonomous, self-help organisations controlled by their members. If they enter into agreements with other organisations, including governments, or raise capital from external sources, they do so on terms that ensure democratic control by their members and maintain their cooperative autonomy.

5. education, training, and information

Cooperatives provide education and training for their members, elected representatives, managers, and employees so they can contribute effectively to the development of their co-operatives. They inform the general public - particularly young people and opinion leaders - about the nature and benefits of co-operation.

6. cooperating amoung cooperatives

Cooperatives serve their members most effectively and strengthen the cooperative movement by working together through local, national, regional and international structures.

5 7. concern for community

Cooperatives work for the sustainable development of their communities through policies approved by their members. (ICA, n.d.)

These are a clustering of the good practices, and thus no static element (Hollebecq & Jacobs, 2019). Hollebecq and Jacobs (2019) emphasize that the point of these principles is to serve as a guideline, and they should be interpreted and translated into each individual organisational context.

The U.S. department of agriculture (USDA) provides “leadership on food, agriculture, natural resources, rural development, nutrition, and related issues based on public policy, the best available science, and effective management”. Ortmann and King mention (2007) that the United States Department of Agriculture in 1987 defined cooperatives using only the first three principles, which in essence are “the three principles of user ownership, user control and user benefit”. Next to these three main principles, Frederick (1997) also talks about three other related practices that some cooperatives apply to further differentiate themselves as a cooperative. These are “the patronage refund system”, “limited return on equity capital” and “cooperation among cooperatives” (Frederick, 1997). In essence, the patronage refund refers to cooperatives in which producers cooperate and in which the people who produce most get the largest share of the earnings, after all the costs have been paid. The limited return on equity capital means that there are no high dividend pay outs (Frederic, 1997). The cooperation among cooperatives corresponds to principle six. The principles of the USDA and ICA are based on the same fundamentals, however the USDA principles focuses on giving a definition while the ICA principles focus on giving guidance (Reynolds, 2014).

3. Types of cooperatives

ICA classifies cooperatives in 4 main groups: worker cooperatives, enterprise cooperatives, citizen - and consumer cooperatives, and multi-stakeholder cooperatives (Cera, n.d.). Carson (1977) states that, for a huge part, the differences in cooperations lies in who controls the board of directors.

Belgian law also has the organisation form ‘social enterprise’, which is a specific type of cooperation that conforms to more norms than a regular cooperative. This can be found in the ‘wetboek van vennootschappen en verenigingen’ in art.8:5, § 1.

European law has also created a special type of cooperative, the European Cooperative Society (ECS), in order to facilitate a more international cooperation (European Commision, n.d.).

3.1. Enterprise cooperatives

Lee and Mulford (1990) define these kinds of enterprises for Japan. They look into small enterprises engaged in manufacturing, wholesale, retail or providing services. These enterprises exist prior to

6 becoming members of the cooperative (Lee & Mulford, 1990). Thus, it is the prior company that becomes the member, not an individual. Lee and Mulford (1990) state that each member, when part of the cooperative, continues their own management and ownership and the company can easily leave the cooperation at any time. It is not a joint venture or a merger of companies.

This is an organisational form that unites self-employed workers with the goal to cooperate on one or more activities of their value chain/business operations, with the result of taking on a stronger position in the market (Cera, n.d.).

A special form of this type of cooperative is called the producer cooperative (Cera, n.d.). Cera says that these cooperatives often are producers that market their products together.

Fici (2013) writes that producer cooperatives are founded because parties (that become members of the organisation) wanted to supply goods or services. The goods or services are supplied by the members to the organisation “in order to transform, process, market or sell [them]” (Fici, 2013).

3.2. Worker cooperatives

A worker cooperative is also called a producer co-operative or a worker-managed firm (Carson, 1977). Carson (1977) states that the members of this type of firm are the employees of the company, while the management consist out of “elected representatives of at least some of its employees”.

Pérotin (2014) says that in these organisations, the business is run by its employees. According to Pérotin, recent research has shown that these kind of companies “are present in most industries, are not always less capital intensive and tend to be larger on average than their conventional counterpart, and survive at least as well” (Pérotin, 2014).

Mikami states that these types of organisations are owned by the workers of the company (2003). He explains that the workers use their own labour to produce goods/services that they then sell to consumers (Mikami, 2003).

Fici (2013) states that the goal of a worker cooperative is to employ the members of the organisation. The members are thus “individuals interested in working” (Fici, 2013).

ICA (n.d.) defines this type of organisation as one that “applies the principle of democracy to the legal structure of the workplace”. ICA explain this with the help of image 1 and 2.

7 Image 1: Conventional business Image 2: worker cooperative

Source: ICA (n.d.) source: ICA (n.d.)

In a conventional business, the amount of control an investor has is divided based on capital invested (ICA, n.d.). ICA explains that in a worker cooperative, this is based on the fact that the member delivers work for the company. Thus, in a worker cooperative, profits and losses are divided among the employees based on the hours that they work, or the gross pay they receive from the company (ICA, n.d.).

3.3. Consumer cooperatives and Community cooperatives

3.3.1. The consumer cooperative

Cason (1977) states that the members of a consumer cooperative - also called a consumer-managed firm - are the retail customers. The management consists of “elected representatives of at least some of its retail customers”. The management makes decisions about i.a. price and production of products and services (Carson, 1977).

The consumer cooperative is an organisation that is managed in the interest of the client of the organisation, being the consumer (Enke, 1945). Enke (1945) says the consumer cooperative is “expected to achieve economic efficiency while simultaneously serving important private interest”. He argues that this type of organisation is good for the economic welfare and should therefore get more attention from the legislature.

Mikami also says that the owners of this type of company are the consumers themselves (2003). They are the users of the product provided by the company, and on top of this they also need to hire workers for the company to operate (Mikami, 2003).

Fici (2013) states that this type of enterprise is formed by “persons interested in obtaining certain goods or services”. The activity of this enterprise is to provide these goods or services to the members (Fici, 2013).

8

3.3.2. Community cooperatives

Mori (2014) states that all owners of these cooperatives are citizens. Two other characteristics are that they “provide or manage community goods, and warrant non-discriminatory access to them” (Mori, 2014). In this category, Mori (2014) speaks about the first electric cooperative “sociatà cooperative per l’illuminazione elettrica” in Italy. Mori identifies these kinds of companies as “monopoly providers of a general-interest service and catered to whole communities, members and non-members alike” (Mori, 2014).

In their work about a telecommunication community cooperative, Finquelievich and Kisilevsky (2005) identify this kind of company as “an autonomous association of individuals, who join forces to respond to common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned enterprise, democratically governed and managed”.

The members of these organisations are citizens of a community (Cera, n.d.). Cera states that these members produce and consume the delivered product/service. A well-known example of these kinds of enterprises, according to Cera, is the energy cooperation. It is an advanced form of the consumer cooperation, because the members are also the producers of the good/service (Cera, n.d.).

3.4. Multi-stakeholders cooperatives

3.4.1. Stakeholders

Freeman (2010) defines stakeholders as “any group or individual who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization’s objectives”.

Clarkson (1995) says that “stakeholders are persons or groups that have, or claim, ownership rights, or interests in a corporation and in its activities, past, present or future”. It is the transactions that were made by the corporation that lead to these stakeholders making a claim (Clarkson, 1995). Clarkson says that these claims can be “legal or moral, individual or collective”. Clarkson discusses two groups of stakeholders, namely primary stakeholders and secondary stakeholders. The primary stakeholders are the ones that are needed to survive as a company (shareholders, investors, employees, customers, suppliers and the public stakeholder group). The secondary stakeholders are those “who influence or affect, or are influenced or affected by, the corporation, but they are not engaged in transaction with the corporation and are not essential for its survival” (media, special interest groups) (Clarkson, 1995). Pearce (1982) says that stakeholders, also called claimants, expect or even demand the company to satisfy their claims. He specifies two groups of stakeholders. The inside claimants are executive officers, the board of directors, stockholders and employees. The outside claimants are customers, suppliers, governments, unions, competitors, local committees and the general public. Every stakeholder has a different claim, for example: stockholders claim a return on the investment they

9 made, customers want to receive the goods or services that they pay for, and so on (Pearce, 1982). According to Hill and Jones (1992) these claims are legitimate because of the exchange relationship they have. Customers pay, so in exchange they have a legitimate claim to a product of service from the company.

Turner and Zolin (2012) argue that larger projects also have more stakeholders that judge the outcome of the project.

3.4.2. Stakeholder theory

Donaldson and Preston (1995) state that the stakeholder theory defines a corporation as the combination of cooperative and competitive interest (from the different stakeholders) that all have an intrinsic value. It is said that when a company manages all the different interests (managing meaning giving simultaneous attention to these interests), the company will be successful (Donaldson & Preston, 1995). They illustrate the stakeholder model in image 3.

Image 3: The stakeholder model

Source: Donaldson &Preston (1995)

3.4.3. Multi-stakeholder cooperatives

A multi-stakeholder cooperative is an organisation that has members who belong to at least two different stakeholder groups (Leviten-Reid & Fairbairn, 2011). Leviten-Reid and Fairbarin (2011) continue by saying that in this kind of organisation, all stakeholder groups manage the cooperation together, and will thus decide together on the distribution of the profit among these several groups. Furthermore, they say that it is widely accepted in academic research that multi-stakeholder cooperatives don’t work because of the expensive decision-making structure. However, Leviten-Reid and Fairbairn (2011) argue against this commonly accepted assumption by referring to empirical evidence which proves that multi-stakeholder cooperatives are in fact able to “govern themselves successfully and peruse shared goals.”

10 Münkner (2004) defines a multi-stakeholder cooperative as a cooperative witch has a heterogeneous pool of members (Münkner,2004).

Lund (as cited in Gonzalez, 2017) describes multi-stakeholder cooperatives as followed:

MSCs are coops [abbreviation of cooperatives] that formally allow for governance by representatives of two or more “stakeholder” groups within the same organization, including consumers, producers, workers, volunteers or general community supporters […] The common mission that is the central organizing principle of a multi- stakeholder cooperative is also often more broad than the kind of mission statement needed to capture the interests of only a single stakeholder group, and will generally reflect the interdependence of interests of the multiple partners. Lund (as cited in Gonzalez, 2017)

3.5. Social enterprises

A cooperative has to comply with the conditions mentioned in section 4.3. In Belgium, a cooperative can become a recognized social enterprise if it fulfills three additional conditions mentioned in art. 8:5 § 1 in the ‘wetboek van vennootschappen en verenigingen’.

The first condition is that the main goal of the organization is to, in the common interest, have a positive societal impact on people, the environment or society. The second condition is that any capital gain paid to the shareholder, in whatever form, cannot be higher than the interest rate determined by the king as per execution of the law of the 20th of July 1955 regarding the National Counsel for

Cooperation, Social Entrepreneurship and Agricultural Holding, applied on the, by the shareholders actual deposited amount of, shares. This rule is sanctioned by nullity. The third condition is that, if liquidation occurs, the money remaining after balance sheet payoff is given to a cause closely related to the original goal of the company.

The European Commission (n.d.) defines the social enterprise in as:

Those for who the social or societal objective of the common good is the reason for the commercial activity, often in the form of a high level of social innovation. Those whose profits are mainly reinvested to achieve this social objective. Those where the method of organization or the ownership system reflects the enterprise's mission, using democratic or participatory principles or focusing on social justice. (The European Commission, n.d.)

It is mentioned that many of these social enterprises take the organizational form of a social cooperative (European commission, n.d.).

The social enterprise is a form of hybrid organization (Alter, 2007). Alter defines this hybrid organization as an organization that is located between two extremes. On the one side of the spectrum, you have the for-profit organization and on the other side of the spectrum you find the

non-11 profit organization (Alter, 2007). This spectrum also helps define the goals, methods and destination of the profit made by a hybrid organization. This spectrum of practitioners is showed in image 4.

Image 4: Spectrum of Practitioners

Source: Alter (2007)

The social enterprise in particular is defined as “any business venture created for a social purpose – mitigating/reducing a social problem or a market failure – and to generate social value while operating with the financial discipline, innovation and determination of a private sector business.” (Alter, 2007).

Dart (2004) states that the social enterprise is different from a non-profit organisation. Johnson (as cited in Dart, 2004) writes something similar to Alter (2007). He mentions that “they blur boundaries between nonprofit and forprofit”, and also notes that the activities of the organisation are a mix from the non-profit organisation and the for-profit organisation.

3.6. The European Cooperative Society (SCE)

This is a legal form of organisation that the European commission created in order to “facilitate cooperatives' cross-border and trans-national activities” (European commission, n.d.). The European Commission requires that the members of this type of organisation are residents from at least two different European countries.

This legal form exists since 22 of July 2003 and was created by the EU legislation with the intention to make cross-border activities of cooperatives easier (Fici, 2013).

The regulation concerning the SCE, taken effect on the 22the of July 2003 goes as follows:

A European cooperative society (hereinafter referred to as "SCE") should have as its principal object the satisfaction of its members' needs and/or the development of their economic and/or social activities, in compliance with the following principles: its activities should be conducted for the mutual benefit of the members so that each member benefits from the activities of the SCE in accordance with his/her participation; members of the SCE should also

12 be customers, employees or suppliers or should be otherwise involved in the activities of the SCE; control should be vested equally in members, although weighted voting may be allowed, in order to reflect each member's contribution to the SCE; there should be limited interest on loan and share capital; profits should be distributed according to business done with the SCE or retained to meet the needs of members; there should be no artificial restrictions on membership; net assets and reserves should be distributed on winding-up according to the principle of disinterested distribution, that is to say to another cooperative body pursuing similar aims or general interest purposes. (Verord.Raad. nr. 1435/2003, 2003 July 22 concerning het statuut voor een Europese Coöperatieve Vennootschap (SCE))

Although the law was only published in 2003, the groundworks started in 1954 (Chomel, 2004). The SCE is closely connected with the development of the European company statute (Snaith, 2006). Fici (2013) even calls it “the cooperative equivalent to the European company (SE)”.

Ibáñez (2011) states that this law cannot be seen as independent from the national law of each member state. All matters that are not regulated by this law, are following the national law of the member state (Ibáñez,2011). Ibáñez (2011) states that this makes the regulation very complex and “creates coordination problems between European and national laws”.

The SCE has limited liability and can have “a variable number of members and share capital” (Snaith, 2006).

As this is a European organisational form, the Belgian law reform had no impact on this (Liantis, 2019). It is thus still an organisational form that can be taken on by enterprises in Belgium, if they meet the requirements.

4. The cooperative history until today

4.1. Establishment of the Cooperative movement

Mentioned in most academic literature as the beginning of the cooperative movement is Rochdale (Van Opstal, 2010; Holyoake as cited in Mori, 2014; Barton as cited in Kyriakopoulos, 2000; Fici, 2013). In these papers, Rochdale is described as a group of artisans from the United Kingdom who founded a cooperative in 1844 in order to realize lower prices for certain victuals. This is said to be the first successful consumer cooperation. Hilson, Neunsinger and Patmore (2019) go as far as calling Rochdale “the prototype of the modern co-operative society”. However, Birchall (1994) speaks about a cooperative farm named Jumbo, founded in 1851 near Rochdale, as the start of this cooperative movement.

13 In 1860, the artisans involved in the cooperative movement in Rochdale established cooperative principles, on which the ICA principles mentioned in section 2.2. are inspired (Barton as cited in Kyriakopoulos, 2000; Hilson, Neunsinger, & Patmore, 2019; Reynolds, 2014).

The principles of the USDA are also based on these exact same principles (Reynolds, 2014). Birchall (1994) mentions that the Rochdale principles are: ‘open membership’, ‘democratic control’, ‘distribution of surplus in proportion to trade’, ‘payment of limited interest on capital’, ‘political and religious neutrality’, ‘cash trading’ and ‘promotion of education’.

Frederick (1997) argues that, although Rochdale was a very important pioneer, it was not the first. Frederick (1997) and Majee & Hoyt (2011) say that the cooperative movement starts with a fire insurance company, founded by Benjamin Franklin in 1752 in the US.

Alter (2007) claims that this movement starts with Robert Owen in the mid-1800s. It would have started in the cotton mills of New Lanark in Scotland. In these mills, the idea of a good work environment and education was introduced for the employees (Alter, 2007). He states that it’s in this context that the first cooperative store opened. The idea of ‘villages of cooperation’ was also formed, with the goal of lifting employees out of poverty by making them self-governing (Alter, 2007). To summarize, although different origins are mentioned, the cooperative movement started in the period of 1750-1850. Rochdale is most often mentioned as the starting point of the cooperative movement. The vast majority of academic literature acknowledges the artisans of Rochdale as the first ones to define cooperative principles. These principles continue to have a great influence on the cooperatives as we know them today.

4.2. The cooperative history in Belgium

The Belgian cooperative history is marked by some important key events.

In 1873 the Belgian law developed a statute ‘cooperative enterprise’ (Van Opstal, 2010). The law goes as follows: The cooperative enterprise is an enterprise that is comprised out of a variable amount of shareholders with a variable contribution and of which the shares cannot be transferred to third parties (Fabecoop, 2017; art. 141, § 1 WvK 1935 November 30).

In 1955, the national council for the cooperative was founded and since 1962, this institution can recognise companies as cooperatives if they fulfil certain requirements (Van Opstal, 2010). These requirements are: voluntary accession, equality of shares, equality or limitation of the voting rights of company members on the general meeting (maximum 10%), appointment of commissioners and of the board of directors by the general meeting of company members, a moderate interstate that is limited to the registered capital, the unsalaried mandate of the managers, a rebate to the company

14 members of maximum 6% and providing in the needs of the company members (Coates & Van Opstal, 2010). The national council is an advisory body that was founded to spread the cooperative principles and to safeguard the ideal of the cooperation (FOD economie, 2020).

On the 20th of July in 1991, the law split the uniform statute of cooperative enterprise up into two

different variations, namely the CVBA an CVOHA (Braeckmans, 1996; Van Opstal, 2012). On the 29th of

July in 1993, a minor change was implemented as a reaction to the criticism this law received (Braeckmans, 1996). The CVBA is the abbreviation for the cooperative enterprise with limited liability and the CVOHA is the abbreviation for the cooperative enterprise with unlimited, joint and several liability (Gielis & Ruysschaert, 2018). On the 7th of May in 1999 the law changed the CVOHA to CVOA

(which is the abbreviation for the cooperative enterprise with unlimited liability) (Van Eeckhoute, 2000). The characteristics of the CVBA and the CVO(H)A can be found in table 1.

Table 1: Characteristics of the CVBA and CVO(H)A

CVBA CVO(H)A

Memorandum of

association Authentic act Authentic act or underhanded deed

Number of partners Minimum 3 Minimum 3

Liability Limited Unlimited, joint and several

Minimum amount of

capital needed 18.550 euros n/a

The paying-up 6.200 euros n/a

The paying-up per

share in cash Minimum 25% n/a

Contribution in kind Accepted if there is a report from an

auditor No need for a report from an auditor The paying-up per

share contribution in kind

The paying-up needs to be completed within the first 5 years n/a

Financial plan Mandatory n/a

Shares registered Registered

Share transfer Transfer among partners: unbound Transfer to third parties: like stated in the statutes

Transfer among partners: unbound Transfer to third parties: like stated in the statutes

Amount of managers Minimal 1 Minimal 1

Source: Gielis & Ruysschaert (2018); Ghesquière, Everaert, & De Groote (2017)

In 2019, company law was reformed. Part of this reform concerned co-operative type of organizations, as the reform abolished the CVOA. Since there was no longer a need to distinguish between the CVOA and CVBA, the notation was shortened to CV. (Bruloot, de Wulf, & Marsceau, 2018). The CVOA and CVBA were often used by companies because of the statutory flexibility that came with this form of organization (Bruloot et al., 2018). In the reform they made sure that only real cooperatives can belong to this organization form and that the statutory flexibility will also become a characteristic of the BV

15 (Bruloot et al., 2018). The current law on the cooperatives, that became valid with this reform, is mentioned in section 4.3.

Although the social enterprise is defined as a special type of cooperative in section 3.5, before this reform in 2019, they were subject to a different law. Thus, instead of being a special form of a cooperative, the social mindset was shown by adding a suffix ‘SO’ (social purpose) to each commercial company (Pijls, 2007). As such the organisation became a BVBA SO (limited liability company with a social purpose), CVA SO (limited partnership with share capital with a social purpose), CVBA SO (cooperative enterprise with limited liability with a social purpose), NV SO (public limited company with a social purpose), and so on. This former law was introduced in 1995 and was made for the enterprises with a social purpose, called the VSO (Vanaroye, 2015).

4.3. The current legislation on cooperatives

The current Belgian law defines cooperative organisations in book 6, article 6:1 § 1 of the companies and Associations Code as followed: The cooperative organisation has as primary goal to fulfill the needs of her shareholders or third interested parties and/or develop their economic and social activities, i.a. by entering into agreements with them for the delivering of goods, providing of servies or the carring out of works withing the context of the activities that the cooperative carrys out or lets others carries out for them. The cooperative organisation can also have as goal the fulfilling of the needs of her shareholders or the needs of her perent company and those shareholders or the needs of therd intrested parties, and this may or may not be fullfilled with intervention of the subsidiaries. The cooperation can also has as goals to foster economic and/or social activities trough a participation in one or more other organisations (Art. 6:1, § 1 WVV 2019 march 23 concerning Wetboek van vennootschappen en verenigingen).

Hollebecq and Jacobs (2019) state that it was the intention of the legislator to make the definition resemble the one that ICA proposes, but that it is nearly impossible to translate the ICA principles into mandatory law. They also state that de definition is inspired by European law (Hollebecq & Jacobs, 2019).

The European Commission (n.d.) defines cooperatives as “an autonomous association of persons united to meet common economic, social, and cultural goals. They achieve their objectives through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprise”.

5. Comparison with other organisation forms

5.1. Other cooperative forms

Although cooperatively working together and the associated social goals are often discussed in academic literature, not all these papers are about cooperatives. The subject can also be a partnership,

16 a non-profit organisation or a multi-stakeholder initiative. For a better understanding of the cooperative organisation, these other organisational forms will be explained in this section.

5.1.1. Partnership

Flanders investment & trade defines a partnership as two or more co-owners that together conduct a business activity, with the motive of making a profit. Juridically, this is seen as a group of individuals instead of one entity (Flanders investment & trade, n.d.). Every partner must report his share in the profit individually in his own tax declaration (Flanders investment & trade, n.d.).

Mohr and Spekman (1994) define partnerships as “purposive strategic relationships between independent firms who share compatible goals, strive for mutual benefit, and acknowledge a high level of mutual interdependence”. By forming this partnership, they not only hope to accomplish goals that are hard to fulfill on their own, but they also aim to create a competitive advantage by working together (Mohr & Spekman, 1994).

5.1.2. A multi-stakeholder initiative

Multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) are frameworks for the interaction of businesses, non-profit organisations and sometimes other stakeholders (Federal institute for sustainable development, 2018). These frameworks make it possible to address mutual (wicked) problems. These initiatives “may facilitate dialogue across stakeholder groups, promote cross-sector learning, or develop standards for corporate conduct” (Federal institute for sustainable development, 2018).

These MSIs build on the stakeholder theory, mentioned in section 3.4.2 (Moog, Spicer, & Böhm, 2015). But instead of having corporate managers make this consideration, these initiatives bring corporate, and non-corporate stakeholders together as equals (Moog et al., 2015). According to Moog et al. (2015) this creates a space for dialog, debate and results in soft regulation (e.g. standard-settings, social reporting, certification…).

Dentoni and Bitzer (2015) say that MSIs are “voluntary and self-regulatory agreements” between shareholders that are created as a reaction to the arise of wicked problems (e.g. climate change, biodiversity loss…).

5.1.3. Non-profit organisation

Non-profit organisations are organised, private entities that do not distribute profit, are self-governing and are “non-compulsory in nature” (Salamon & Anheier as cited in Goulet & Frank, 2002). Drucker (1995) say that the non-profit institution has as product ‘a changed human being’ and calls these institutions ‘human-change agents’. Examples of products of these types of organisations are cured patients, a child that gets education, and so on (Drucker, 1995).

17 Groot and Helden (1993) state that adding value to an ideal or societal goal is the raison d’être of these companies.

These organisations have no profit motive and their activity delivers a high value to the society (Groot & Helden, 1993). This is different from cooperatives, as Puusa, Mönkkönen and Varis (2013) note that cooperatives have a dual nature. This duality consists of aiming to make a profit, while simultaneously trying to accomplish more humanistic goals (Puusa, Mönkkönen, & Varis, 2013).

According to Dart (2004) “social enterprises differ from the traditional understanding of the non-profit organisation in terms of strategy, structure, norms, and values and represents a radical innovation in the nonprofit sector.”

5.2. IOF

The cooperative organisation statute exists next to different statutes. The most common statutes in Belgium are the BV and the NV. These are firms that are investor owned and are thus called investor owned firms (IOFs).

As mentioned before, a big difference between the cooperative and the IOF was the flexibility of the statute. This was often why founders opted for the CVOA or the CVBA (Bruloot et al., 2018). With the reform of the legislation in 2019, this changed. The flexibility was no longer only reserved for the cooperative (Bruloot et al., 2018). Another big change is that the cooperative statute can no longer be chosen if you do not have the cooperative mindset (Draft bill concerning het wetboek van vennootschappen en verenigingen en houdende diverse bepalingen).

Bauwens, Gotchev and Holstenkamp (2016) state that the difference between an IOF and a cooperation is the ownership. The owners in a cooperation are the members or users of the cooperation while the owners of an IOF are the investors (Bauwens, Gotchev, & Hostenkamp, 2016).

5.3. Comparison cooperative with IOF in previous literature

In this paper, the difference in financial results between the IOFs and the cooperatives will be examined. To start, this section summarizes results of previous literature. All these papers are focused on the agricultural industry, as this is where most research has been conducted.

In the paper ‘Performance measurement of the agricultural marketing cooperatives: the gap between theory and practice’ from Soboh, Lansink, Giesen and van Dijk (2009), the literature on the performance of these type of organisations is summerised. They did this reaserch because, according to the authors, there is a big gap between theory and empirical research.

Sosnick (as cited in Sohob, Lansink, Giesen, & van Dijk, 2009) says that theoretical literature finds that cooperatives are divided into three classes. As explained before, these are: “a vertically integrated

18 firm”, “an independent business enterprise” and “a coalition of firms”. The first two forms assign one objective to the cooperative, while the last form assigns multiple objectives to the cooperative (Sosnick, as cited in Soboh et al., 2009).

Empirical literature only looks into cooperatives as profit-maximising organisations (Sohob et al., 2009). Thus Sohob et al. (2009) see cooperatives as “independent firms that do not explicitly address members’ objectives”. This neglect of the other approaches can be explained by the absence of the needed data, the absence of interest from the economists or the absence of ways to theoretically approach these other views (Soboh et al., 2009). Soboh et al. (2009) also say that “using frameworks of vertical integration and coalition of firms is impossible due to lack of data”. They conclude that, until now, research on these kinds of firms have failed to address the dual nature of cooperatives.

Although this dual nature is neglected when financial ratios are used to evaluate cooperatives, they can give an indication of the firm’s position (Soboh et al., 2009). Soboh et al. (2009) made an overview of studies that compare cooperatives with IOFs, for certain financial ratios. Tis overview is structured in table 2.

Chen et al., Hardesty and Salgia, and Lerman and parliament are often cited papers that are mentioned in table 2. These three studies are now discussed in more detail.

‘Growth of Large Cooperatives and Proprietary Firms in the US Food Sector’ by Chen et al. (1985) researches the difference in growth between cooperatives and proprietary firms. The dataset was comprised of 32 cooperatives and 35 proprietary corporations active in the food industry (SIC codes 202, 203, 204, 207, 515) (Chen et al., 1985). The cooperatives and proprietary corporations in the sample were matched based on the functions they perform (Chen, et al., 1985). The research analysed data from 1975 to 1980. They looked at the explaining power of profitability, diversification, mergers and acquisitions, advertising, leverage and initial firm size on the growth of the company. They found that cooperatives grew more, but the variables they investigated did not explain the major share of this difference. Related to the research done in this paper, Chen et al. (1985) found that cooperatives on average where much more highly levered then proprietary firms and that cooperatives are on average less profitable than proprietary firms (as mentioned table 2).

19 Table 2: Financial ratio comparison between IOFs and Cooperatives

Financial ratio Result Study Sector Country Data

period Leverage COOP < IOF Schrader et al.

(1985)

Dairy, grain, farm supply

USA 1979-1983

COOP > IOF Chen, Babb, Schrader (1985)

Dairy USA 1983

COOP > IOF Venieris (1989) * Wine Greece 1985 No sign.

difference

Lerman and

Parliament (1990)

Dairy, fruit and vegetable

processing

USA 1976-1987

COOP < IOF Hardesty and Salgia (2004)

Dairy, farm supplies, fruit and vegetables, grain USA 1991-2002 Efficiency (Asset turnover) No sign. difference Schrader et al. (1985)

Dairy, grain, farm supply

USA 1979-983

COOP > IOF Hardesty and Salgia (2004)

Dairy USA 1991-2002

Profitability COOP < IOF Chen, Babb, Schrader (1985)

Dairy USA 1983

COOP < IOF Venieris (1989) * wine Greece 1985 COOP < IOF Natta and Vlachvei

(2007)

Dairy Greece 1990-2001

COOP < IOF Schrader et al. (1985)

Dairy, grain, farm supply USA 1979-1983 No sign. difference Lerman and Parliament (1990)

Dairy, Fruit and vegetable

processing

USA 1976-1987

Liquidity COOP > IOF Venieris (1989) * wine Greece 1985 Sign. = significant

COOP = cooperative

20 ‘Comparative financial performance of agricultural cooperatives and investor-owned firms’ from Hardesty and Salgia (2004) researched whether claims of cooperatives destroying value and the doubt about the viability of agricultural cooperatives were justified. They researched this by comparing financial ratios from cooperatives and IOFs in the agricultural business. More specifically, they looked into 41 cooperatives that where active in either the dairy, farm supply, fruit and vegetable or grain sector. Hardesty and Salgia (2004) matched the IOFs based on industry and used aggregated financial variables for those industries, reported by the Risk management association. The ratios were calculated from these aggregated variables (Hardesty & Salgia, 2004). They point out that using these aggregated variables instead of the data from individual companies is a big shortcoming, but that it was the only possibility to obtain the data needed for the research. The data was analysed for the period 1991 until 2002 and the companies were active in California, Oregon and Washington (Hardesty & Salgia, 2004). Although financial ratios have their limitations, they claim that “the theoretically sound approaches are impractical to use because of data limitations” and state that the important stakeholders of cooperatives look more to these ratios. As mentioned in table 2, the cooperatives had a lower leverage in all industries and higher efficiency in three of the four industries compared to the IOFs. Looking into the profitability and liquidity, they found more complex results. Concerning profitability, the grain cooperatives performed better than the matched IOFs on all ratios, but this outperformance decreased over time (Hardesty & Salgia, 2004). The profitability in the other industries was less consistent over all the measured ratios. Concerning liquidity, cooperatives in the dairy industry and in the fruit and vegetable industry had a lower current ratio than the matched IOFs (Hardesty & Salgia, 2004). The cooperatives in the grain industry started off with a lower liquidity, but improved over time compared to the IOFs. Hardesty and Salgia (2004) found that the cooperatives in the farm supply industry had a higher current ratio than the matched IOFs but their advantage has decreased over time. They conclude that there are no consisted differences between IOFs and cooperatives concerning financial performance, with exception of the lower leverage. They also conclude that “cooperatives had the strongest relative financial performance in the grain sector” and that the claims of cooperatives destroying value do not hold in this analysis.

The paper ‘Comparative Performance of Cooperatives and Investor-owned Firms in US Food Industries’ by Lerman and Parliament (1990) is mentioned in the literature review of Sohob et al. (2009) and in the literature review of Hardesty and Salgia (2004). They state that cooperatives have different objectives than IOFs because cooperatives “aim to provide a service to their members patrons” while IOFs focus on generating return on investment (Lerman & Parliament, 1990). This different objective stems from the main goal of cooperatives being to correct market failures (Lerman & Parliament, 1990). They researched if “the difference in objectives between cooperatives and investor-owned

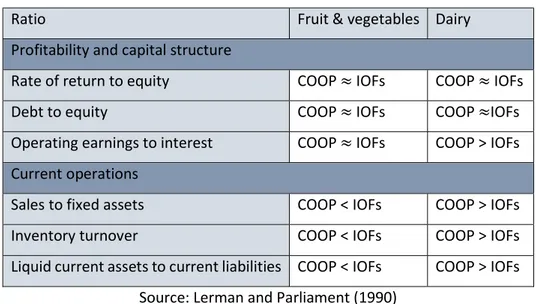

21 firms outweighs the effect of the similarities in business functions” by comparing the financial performances of both using financial ratios. They looked into companies active in the diary and fruit and vegetable processing sector in the US form 1976 through 1987. Lerman and Parliament (1990) only look into small firms, which means the firms have an asset size between 10 million dollar and 100 million dollars. This is done to control for the size effect (explained later in this section). They compared data from 18 cooperatives, which they collected from audited annual reports, with industry median financial ratios for IOFs that where reported by the Robert Morris Association in the annual statement studies. As showed in table 2, Lerman and Parliament (1990) did not find a significant difference between both groups in terms of the leverage and profitability ratios. They made a more detailed overview of the results, shown in table 3.

Table 3: Comparison of cooperatives and IOFs in the fruit and vegetable and the dairy industry

Ratio Fruit & vegetables Dairy

Profitability and capital structure

Rate of return to equity COOP ≈ IOFs COOP ≈ IOFs

Debt to equity COOP ≈ IOFs COOP ≈IOFs

Operating earnings to interest COOP ≈ IOFs COOP > IOFs Current operations

Sales to fixed assets COOP < IOFs COOP > IOFs Inventory turnover COOP < IOFs COOP > IOFs Liquid current assets to current liabilities COOP < IOFs COOP > IOFs

Source: Lerman and Parliament (1990)

If cooperatives and IOFs are mentioned to perform differently on a ratio in table 3, this difference is significant on the 0,05 significance level (Lerman & Parliament, 1990). They found that in the fruit and vegetable industry, cooperatives have a lower performance than IOFs on the sales to fixed assets ratio. However, through the years, these cooperatives started to use their assets more to generate sales (Lerman & Parliament, 1990). This makes Lerman and Parliament (1990) conclude that the overinvestment issue for these cooperatives has diminished. The lower liquid current assets to current liabilities (quick ratio) of the fruit and vegetable processing cooperatives are explained by the companies having a lower amount of accounts receivable compared to the IOFs, which may signal that cooperatives experience more restrictive credit terms (Lerman & Parliament, 1990). Lerman and Parliament (1990) conclude that by comparing these cooperatives with the IOFs, they did not find strong evidence in support of the hypotheses that cooperatives would have a lower profitability, higher borrowing and overinvestment in fixed assets and inventories. They also suggest that this conclusion

22 may show that the standards that are set in financial analyses in the business community forced cooperatives to adopt the same goals as IOFs.

Soboh et al. (2009) listed more papers that looked into the performance of agricultural marketing cooperatives that are not mentioned in table 2. In the following section, the results of two important papers of those listed, are discussed.

‘Performance of cooperatives and IOFs in the dairy industry’, written by Parliament, Lerman and Fulton (1990), looked into the difference between IOFs and cooperatives in this industry. They believe that the characteristics of a cooperative are sufficiently different from those of an IOF to “suggest that cooperatives may peruse different objectives” than those an IOF pursues. Their research looked into the dairy industry in the USA in the data period 1971-1987 and they applied financial ratios to compare cooperatives and IOFs. Their findings are summarised in table 4.

Table 4: Comparison of financial ratios between cooperatives and IOFs in the dairy industry Financial ratio Result

Leverage COOP < IOF Liquidity COOP > IOF Efficiency COOP > IOF Solvency COOP > IOF

Profitability Not significant difference Source: Parliament et al. (1990)

In his paper ‘Economic and financial performance of cooperatives and IOFs: an empirical study’, Gentzoglanis (1997) argues that because of the “changing economic and financial structure of cooperatives” the evaluation of their performance became possible with “traditional economic and financial tools”. Before, this was difficult because cooperatives offer non-market services, meaning that it is difficult to put a price on these services. He applied financial ratios comparing cooperatives with IOFs in the dairy industry in Canada on a dataset ranging from 1986 until 1991. Gentzoglanis did not find a significant difference between cooperatives and IOFs regarding profitability, productivity and the use of new technologies. On this ground, he states that the cooperative and IOF are comparable in terms of economic and financial performance (Gentzoglanis, 1997).

There are some papers that are not mentioned in the literature review of Sohob et al. that provide some interesting results as well.

Garoyan (1983) states that the organisation and practices of a cooperative are now more resembling those of an IOF. It is mentioned that managers who first managed an IOF and then a cooperative apply

23 the same practices, and the cooperatives operate in an economy that has the same traits as the one in which the IOF operates (Garoyan, 1983).

Sexton and Iskow (1993) wrote the paper ‘What Do We Know About the Economic Efficiency of Cooperatives: an Evaluative Survey’ in which they researched if the criticism that cooperatives received, because they were claimed to be less efficient than for-profit firms, was justified. In the paper of Sohob et al. (2009) mentioned above, research on the performance of cooperatives was conducted by applying economic efficiency techniques or ratio analysis. In this paper, Sexton and Iskow also divide research into papers who measure performance based on economic efficiency techniques and those based on financial ratios. Sexton and Iskow (1993) point out some criticism for both approaches. For the financial ratio analysis, they say that there is a “lack of solid foundation in economic theory” (Sexton & Iskow, 1993). By looking into research done, based on these two approaches, they conclude that there is not a lot of credible evidence that supports the claims of cooperatives being less efficient than IOFs. Sexton and Iskow (1993) add that “evidence to support a contrary perception is, however, also limited”.

In this overview of literature it can be seen that, depending on the research, different results are found. Parliament, Lerma and Fulton (1990) state that “this could be due to differences in methodology, industries analyzed and asset size of the sample firm”. Venieris (as cited in Gentzoglanis, 1997) mentions that the results they found were influenced by the fact that the cooperatives in Greece can borrow at lower interest rates from the government while IOFs in Greece have to borrow at the market interest, which creates a lower capital cost for the cooperatives compared to the IOFs. This shows that governmental interference also influences the performance on certain financial ratios. Gentzoglanis (1997) argues that similarities to another paper are probably explained by - among other things - similar government regulation, the economic environments that resemble one-another and the proximity of the countries in which research took place. In this paper it is also mentioned that different borrowing conditions between different kinds of companies and the fiscal policy of a country can influence profitability (Venieris, as cited by Gentzoglanis, 1997). Because different conditions may create different outcomes in performance criteria, this study is going to do a similar analysis on Belgian companies, to obtain a conclusion tailored to the Belgian situation.

Another paper of Lerman and Parliament (1989) called ‘Industry and Size Effects in Agricultural Cooperatives’ looks into these financial ratios but, instead of comparing with IOFs, they compare between different cooperatives. They use financial ratios because they believe it reflects “the effect of strategic decisions” and that it reveals the differences they want to examine. They looked into 43 cooperatives in the period 1970-1987. They researched if the size of the cooperative or the industry in

24 which the cooperative is active influences ratio performance. They did this research because of the many (previously mentioned) inconsistencies with theoretical hypothesis in other papers. They found that the size of the cooperative had effect on the profitability, efficiency and liquidity. Large cooperatives were more efficient, had less liquidity, and had a lower profitability compared to small cooperatives (Lerman & Parliament, 1989). They also found that there was an industry effect on all the median financial ratios (leverage, efficiency, liquidity and profitability). They looked into the dairy-, supply-, food- and grain cooperatives. The dairy cooperatives seemed to be the strongest performers based on the financial ratio analysis (Lerman & Parliament, 1989). This could however be the case because of the government that guarantees milk prices and thus this result could be the case because of indirect government support (Lerman & Parliament, 1989). Because of the findings in this research, Lerman and Parliament (1989) advise cooperatives to limit themselves to traditional activities. On top of that, they found a remarkable trend. The profitability of all the cooperatives declined over time (Lerman & Parliament, 1989). Gentzoglanis (1997) mentioned that the “appropriate levels for financial ratios depend to a large part upon the risk characteristic of the industrial sector in which the firm operates” and thus says that “financial ratio analysis is industry-specific”. Because of the findings of the industry effect, we will also look into the most important industries for cooperatives separately and see how they differ from IOFs that operate in that same industry.

6. Research

6.1. Hypothesis

Different results on financial ratios are expected because of the different goals cooperatives have compared to IOFs, as discussed before. They have different principles, which are expected to lead to different behaviour with regards to these financial decisions. The hypotheses made in the following paragraphs are in accordance to those made in most papers listed above, that compared cooperatives with IOFs based on financial ratios (Leraman & Parliament, 1990; Gentzoglanis,1997; Parliament et al., 1990).

Moral hazard plays a key role in how cooperatives are expected to perform on these financial ratios. Before stating the expected performance on each financial category, a short explanation of moral hazard is given.

Moral hazard stems from a principal-agent problem (Grossman & Hart, 1992). This concerns a situation where people take part in risk sharing and in which one person (the agent) can take an action which will affect another person (the principle) (Grossman & Hart, 1992). The individually taken actions affect “the probability distribution of the outcome” (Hölmstrom, 1979). An often-used example is the one of insurance (Grossman & Hart, 1992). For example, after taking out insurance on a car, a person will