CAN POPULARITY SELL: HOW SHELF-BASED

SCARCITY AND UNCERTAINTY AFFECT THE

SALE OF SUSTAINABLE PRODUCTS

Word count: 19.803

Student number : 01508956

Promotor / supervisor: Prof. Dr. Maggie Geuens

Master’s Dissertation submitted to obtain the degree of:

Master in Business Economics: Marketing

III

PERMISSION

I declare that the content of this Master’s Dissertation may be consulted and/or reproduced, provided that the source is referenced.

V

Foreword

In front of you lies my master’s dissertation ‘Can popularity sell: How shelf-based scarcity and uncertainty affect the sale of sustainable products.’ This dissertation was written in the context of my education at the University of Ghent, in order to obtain my diploma in Business economics, with specification Marketing. The writing of this dissertation has been a real challenge and has tested me throughout different parts of the process. The current global pandemic has played an integral part here, as it made it more difficult to discuss with my promotor and has made the methodological part of this dissertation more difficult. I overcame these obstacles in the end. However, if not for the following people, it would have been a lot more difficult. Therefore, I would like to thank the following people who have stood by me and helped me along the road:

• Prof. Dr. Maggie Geuens of the faculty of Economics and Business Administration at Ghent University, for giving me the opportunity to research this interesting topic and for all the help and guidance during the writing of this dissertation. Her help and advice allowed me to continue during moments where I was stuck and felt like I did not know what to do further. Especially, her help during the final days has been greatly appreciated, as she made herself available for online meetings on short notice and gave great advice.

• Prof. Dr. Iris Vermeir of the faculty of Economics and Business Administration at Ghent University, who gave me additional insights and advice on my survey when prof. dr. Geuens was absent. The advice that was given allowed me to continue more quickly and launch the survey sooner than originally thought.

• Next to this, I would also like to thank all of the participants of the focus group and everyone who took the time to fill in my survey. The ten minutes they took out of their day for me, might look like nothing to them, however, it meant the world to me. Without them I would not be able to finish this dissertation.

• Finally, I would also like to thank my parents, my family and all of my friends who stood by me during this long process. Their ongoing support, kind words and advice kept me motivated to finish this dissertation.

VII

Table of content

Foreword ... V Table of content ... VII List of Tables... X List of figures ... XII

1. Introduction ... 1 2. Literature review ... 4 2.1. Sustainable consumption ... 4 2.2. Popularity cues ... 6 2.2.1. Nudging ... 6 2.2.2. Bandwagon effect/heuristic ... 8 2.2.3. Popularity cues ... 10

2.2.4. Factors influencing popularity cues ... 16

3. Experiment 1: Qualitative research ... 22

3.1. Methodology ... 22

3.2. Results ... 23

4. Experiment 2: Quantitative research ... 25

4.1. Problem and objective ... 25

4.1.1. Definining the problem ... 25

4.1.2. Objective... 26 4.2. Hypotheses ... 27 4.2.1. Product popularity ... 27 4.2.2. Perceived quality ... 28 4.2.3. Uncertainty ... 29 4.2.4. Perceived risk... 30 4.3. Methodology ... 31 4.4. Population ... 32 4.5. Results ... 33 4.5.1. Manipulation check ... 33 4.5.2. Popularity as a mediator ... 36

4.5.3. Serial mediation quality ... 38

4.5.4. Moderated mediation uncertainty ... 40

5. Discussion ... 43 6. Limitations ... 47 7. Conclusion ... 49 Bibliography ... XIII 8. Appendix ... XXIII 8.1. Focus group questions ... XXIII 8.2. Transcription focus group ... XXVII 8.3. Survey questions ...XXXIX 8.4. SPSS output ... LXXIII 8.4.1. Research population ... LXXIII 8.4.2. Anova manipulation check ... LXXVIII 8.4.3. Hypothesis 1: Mediation popularity ... LXXXVI 8.4.4. Hypothesis 2: Serial mediation (model 6) Perceived quality ... XCVIII 8.4.4. Hypothesis 3: Moderated mediation (model 7) Uncertainty ... CXIII 8.4.5. Hypothesis 4: Moderated mediation (model 7) Perceived risk ... CXXV

List of Tables

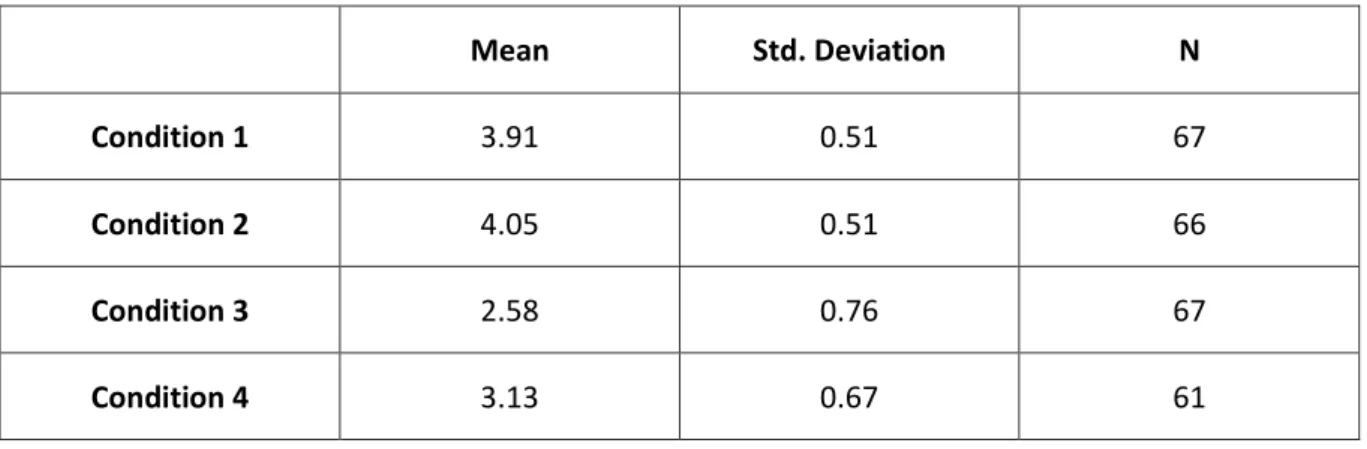

Table 1: One-Way Anova Condition and degree of filled shelves beef 34 Table 2: One-Way Anova Condition and degree of filled shelves veggie 35

List of figures

Figure 1: Visual representation of online popularity cues 13

Figure 2: Visual representation of shelf-based scarcity 15

Figure 3: Mediation effect of expected service quality on the relation between deal

popularity and purchase intention 17

Figure 4: Mediation model of product popularity on the relationship between

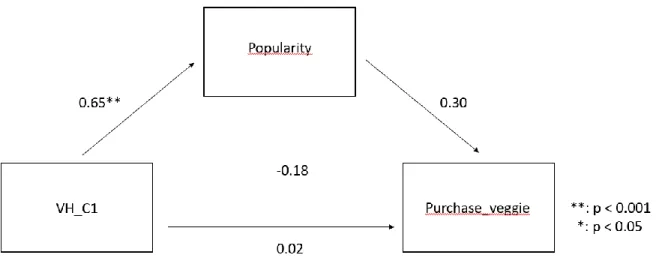

shelf-based scarcity and purchase intention of vegetarian burgers 37

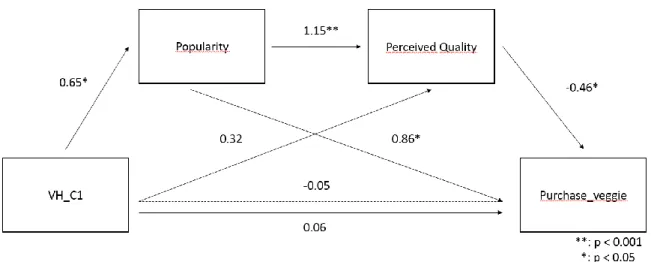

Figure 5: Serial mediation model of product popularity and perceived quality on the relationship between shelf-based scarcity and purchase intention of vegetarian

burgers 39

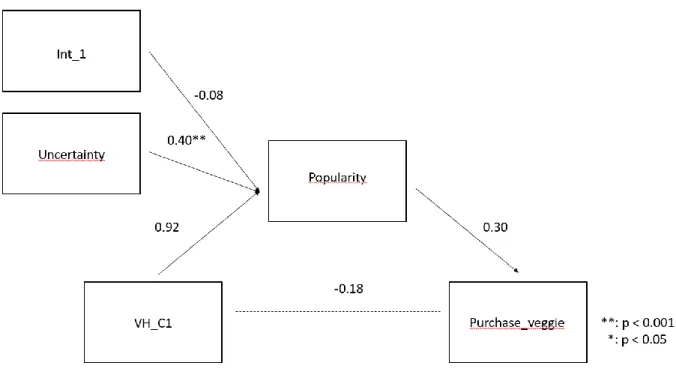

Figure 6: Moderated mediation model of product uncertainty and perceived quality on the relationship between shelf-based scarcity and purchase intention of vegetarian

1

1. Introduction

Nowadays, it is impossible to ignore the fact that our society as we know it is facing major problems on multiple levels. These problems range from socio-economic problems to conflicts that originate from contradictory ideologies who cannot seem to find common ground on everyday aspects. One of the, if not the, most talked about bottlenecks in the last couple of years is the fact that the world is facing major environmental changes or issues. In the scientific world there is consensus that now is the time to act. If no action is taken, scientists believe that climate change has a high probability of accelerating in the coming years. This will have major consequences, as it will launch a new era of increasingly powerful and extreme climate events, such as rises in the occurrence of extremely high or incredibly low temperatures. Moreover, the frequency of such events is likely to expand as well, which will lead to an increase in the vulnerability of natural ecosystems and humans in general (IPCC, n.d.). In general, it is believed that if people fail to address these problems or to adapt to a more sustainable way of living the consequences would prove to be dire, either in the short or long term (‘Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaption: special report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’, 2013).

A major contributor to the degradation of our climate has been the consumption and, consequently, also the production of meat. In actual numbers, the livestock sector accounts for approximately 14,5% of all human-caused greenhouse gasses that are polluting the environment. This means the production of meat actually puts great stress on our environment and adds up to its downfall (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations & Nations, 2013; Vandenbroele, Vermeir, Geuens, Slabbinck & Van Kerckhove, 2019). On top of the huge amounts of emissions of greenhouse gasses, the breeding of livestock has a huge influence in this equation. For example, to keep and breed livestock, incredible amounts of food, water and land are needed, making the industry highly energy-intensive (Gonzales-Garcia, Esteve-Llorens, Moxeira & Feijoo, 2018; Coucke, Vermeir, Slabbinck & Van Kerckhove, 2019). Although retailers play an important part in this, the overall problem stems from the everyday consumer and their consumption choices. Nonetheless, scientists agree that minor changes in a person’s everyday diet, could prove to be beneficial in the fight against environmental degradation in the long run. In order to achieve this, a shift towards sustainable or vegetarian food products could prove to be vital in this fight (Stehfest, Bouwman, van Duren, den Elzen, Eickhout & Kabat, 2009). However, the sales of these products are still lower in number than regular products. In Belgium, the

market share of the sustainable food market accounts for 6.6% of the total market. This can be considered quite a lot. However, improvements still need to be made in the future (‘Belgium shows 37% higher sales of sustainable vegetables’, n.d.).

Going to the store and choosing certain products can at times be described as a real burden, especially when those purchases involve products someone is not familiar with. A lot of our purchases can be considered as routine and are based on products people have been buying for years on end. At a certain point consumers find themselves choosing from products for which they have no strong (prior) preferences or knowledge. When facing such situations, the consumer can draw direct or indirect cues from the retail environment itself, on which he or she can eventually base their product choice (Parker & Lehmann 2011). In this case, the use of nudging can be used to steer consumer behaviour in a certain direction (Wilson, Buckley, Buckley & Bogomolova, 2016). Nudging can be considered as a useful method to influence consumer purchase choices in a rather predictable way, but without changing their economic incentives (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008). Previous literature has already shown its effectiveness to promote better alternatives or more sustainable alternatives (Wilson et al., 2016). Overall, there are a lot of different types of nudges. In this master dissertation the focus will lie on popularity cues and, more concrete, shelf-based scarcity.

Shelf-based scarcity or relative scarcity describes a situation where the shelves of a certain product become depleted by previous product demand, but no “out-of-stock” situation occurs (Gielens & Gijsbrechts, 2018). Previous evidence has shown that situations described by shelf-based scarcity could lead to the occurrence of bandwagon effects and, consequently, to increases in the sales of the relatively scarce product (Van Herpen, Pieters & Zeelenberg, 2009). Bandwagon effects refer to the blind crowd mentality of consumers that believe that when many others have purchased a product, it must be good for them as well (Chaiken, 1987). Consequently, it could lead to an increase in the sales of certain products. In conclusion, Parker & Lehmann (2011) stated that relative scarcity leads to inferences of superior product popularity, through the occurrence of the bandwagon effect, and eventually to a possible rise in the consumer’s purchase intention of a specific product. This relationship can also be manipulated by the retailer to artificially create such effects and shift attention towards certain types of products. This happens via the use of popularity cues.

The goal of this master’s dissertation is fourfold. First of all, the objective is to check if the use of shelf-based scarcity can affect the sales of different types of burgers. Secondly, I want to investigate the role of perceived product popularity in the relationship between shelf-based scarcity and purchase intention. Thirdly, I want to examine if the effect has a greater influence on vegetarian burgers, rather

3 than the regular burgers. Finally, several other variables, like ‘perceived quality’, are put into the equation and examined if they influence the effects of the relationship.

The remainder of this dissertation consists of several steps. To get a clear understanding of all the concepts and more insights in to the relationships between several variables we start off with a literature review. Here, I first address the problems of climate change, after which I continue to talk about nudging, bandwagon effects and popularity cues. To be more concrete, clear explanations of both online popularity cues as well as popularity cues in a retail environment are given. To top things of, several other variables who influence the effect of shelf-based scarcity on purchase intention are discussed. After the literature review, the first (qualitative) experiment is discussed. In the following steps, the different hypotheses are presented and discussed. In the next phase, the second (quantitative) experiment is being addressed. To finalize this master’s dissertation, the reader is presented with the results, a critical assessment of these results and other possible routes for further research are discussed.

2. Literature review

2.1. Sustainable consumption

Nowadays, sustainability has become a hot topic. For quite some time there has been a universal consensus that a shift in human behaviour is needed in order to reduce its environmental impact (Steg & Vlek, 2007). Concerning our meat production, we can conclude that this specific human activity has the largest impact on the environment (de Boer & Aiking, 2019). Not only does this industry produces a large amount of greenhouse gasses, it also requires a lot of land, water and feed to keep and breed the animals. Consequently, scientists believe it is fair to say that human meat consumption should be reduced in the near future (de Vries, van Middelaar & de Boer, 2015). To achieve this, two paths can be taken. Either the amount of the meat portions should be reduced in general or the transition to vegetarian options should be promoted, by making more vegetarian options available in-store (Vandenbroele et al., 2019; Coucke et al., 2019).

Nonetheless, it has become clear that changes must occur in order to reduce future threats to our environment. Scientists have already found clear evidence of rising temperatures in the atmosphere and oceans, as well as staggering reductions in the amount of ice covering the earth. The consequences of these occurrences contain, among others, drops to extremely cold temperatures, rises in exceptionally hot temperatures, rising sea levels and an increase in the amount of natural or global disasters in certain regions of the world (IPCC, 2015). If and when these trends would continue to occur, it will incline detrimental repercussions for our air, water, food and the fact of being free from diseases, which are considered as the four fundamental determinants for human health (WHO, 2011). Considering the magnitude and the gravity of the issue the IPCC (2015) recommended a strategy targeting multiple causes of this problem. For example, a shift from traditional meat consumption to a more sustainable consumption is required (Coucke et al., 2019). In this academic research paper, we will look at the transition from traditional meat (e.g. beef and pork) to vegetarian alternatives. In order to avoid catastrophic consequences, such as rising temperatures or sea levels, and to build towards a better future, our current consumption patterns will, thus, have to change to a more sustainable version of itself. Sustainable consumption has been identified as using goods and services in response to basic human needs and to bring a superior quality of living, all while minimizing its use of our natural resources, emissions of waste and pollutants and toxic materials over its life cycle. This in order not to jeopardize the needs of our future generations (Baker, 1996). Taking this into consideration, overall consumers are increasingly paying attention to the impact of their product

5 purchasing decisions on today’s environment (Auger, Devinney, Louviere, & Burke, 2008; Van Herpen, Van Nierop & Sloot, 2010). However, it should be noted that the fact that people state their concerns, does not mean they will translate this into actual sustainable behaviour. According to Young, Hwang, McDonald and Oates (2009) it is crucial to take into consideration the ‘attitude-behaviour’ gap. In other words, this means that certain individuals can display positive attitudes towards the environment on the one hand, but fail to capitalize on these attitudes by not engaging in actual sustainable behaviour, on the other hand (Gupta & Ogden, 2006). For example, Claudy, Michelsen and O’Driscoll (2010) stated that 80% of Ireland’s population was aware of the existence of photovoltaic panels (i.e. solar panels), however, evidence was found that only 0,1% of those people actually acquired the technology (Claudy, Peterson & O’Driscoll, 2013). Evidence of the existence of this attitude-behaviour gap has also been found in other areas of sustainable consumption. In the field of organic food consumption further confirmation of its existence has been found. Numbers showed that between 46 and 47% of the UK’s consumers held a generally favourable attitude towards organic food. However, the amount of consumers actually buying the products for different organic product ranges was found to be in between 4 to 10% (Hughner, McDonagh, Prothero, Schultz & Stanton, 2007; Young et al., 2009). The existence of this attitude-behaviour gap, meaning environmental attitudes do not always lead to environmental purchasing behaviour, has previously been accredited to different reasons, such as lack of reliability and validity in the measurements, differing levels concerning the specificity in attitude-behaviour measures, low correlations or even external variables (Mainieri, Barnett, Valdero, Unipan & Oskamp, 1997; Gupta & Ogden, 2006).

The actual transition to more sustainable consumption can be obtained,. for example, by means of nudging, which will eventually aim to discourage less sustainable alternatives and try to promote sustainable product choices. These environmentally friendly behaviours can be facilitated by certain acts or interventions of marketers (Tanner & Wölfing Kast, 2003). Following this, a lot of elements in an in-store environment have the possibility to affect the consumers’ options, including the way the products are positioned on the shelves, their visibility or even elements related to their packaging. It is believed that these types of interventions would allow consumers to make their in-store product purchase decisions more easily (Vermeer, Steenhuis & Seidell, 2010; Vandenbroele et al., 2019). In this particular master thesis the focus will lie on the use of visibility enhancements together with social influences in order to obtain a more sustainable consumption pattern. These two topics will be largely discussed later on.

2.2. Popularity cues

2.2.1. Nudging

A relatively new concept that has been wielded in several recent situations is the use of nudging. Nudging can be defined as ‘any addition to, or modification, of the environment that influences consumers in a predictable way, without changing economic incentives’. More specific, it alters the store environment by changing the presentation of options to consumers, which is referred to as their choice architecture. Nudging either consciously or subconsciously influences consumers without removing options or changing economic incentives (e.g. subsidies for solar panels). Considering this, it could be argued that nudging provides people with a less costly alternative than other, more educational measures (e.g. information campaignes). On top of this, nudging differs from other alternatives by being rather unobtrusive and triggering consumer responses without requiring that much cognitive effort (Thaler & Sunstein, 2008). Finally, nudging also makes itself stand out from the rest, because it does not impose restrictions of any kind and rather embraces the customer’s freedom to make its own decisions (Sunstein, 2017; Vandenbroele et al., 2019). Research by Blumenthal-Barby and Burroughts (2012) has provided academic literature with six different categories of nudges and choice architecture categories, which are: priming nudges, salience nudges, default nudges, incentive nudges, commitment and ego nudges and finally norms and messenger nudges. Although every nudge category has been put to use over time and eventually proven its value, this thesis will only discuss the most effective types, being priming and salience nudges.

Priming nudges can be regarded as subconscious cues, either physical, verbal or sensational, that are being applied to influence behaviour into a certain direction. In order to achieve these aforementioned changes in consumer behaviour, retailers can either manipulate visibility, accessibility or availability of the products, among other elements in the store environment (Wilson et al., 2016). The effectiveness of the use of priming nudges can be explained by the economic choice theory (Becker, 1965), which suggests that consumers make decisions that minimize time costs, have few barriers and require the least amount of mental or physical efforts. They make these decisions in order to save time and energy. For example, increased visibility of a product boosts consumer attention to the product, which will eventually positively affect the possibility of a certain alternative to be chosen (Wansink, 2015; Wilson et al, 2016). Next to this, (physical) availability refers to the quantity of options relative to other products (Sharp, 2010; Wilson et al., 2016). The underlying mechanism here suggests that, if availability is increased, the product will be easier to perceive and, therefore, be more accessible for potential consumption (Wilson et al., 2016). These are all examples of ‘visual cues’ and provide

7 retailers with a lot of potential to implement a redesigned in-store environment. The opportunity to improve a consumer’s likelihood of purchasing stems from the fact that such cues increase visibility or attract attention to products. Hence, human vision allows consumers to scan easily and quite fast, which allows them to absorb the environmental information immediately and increases possibility to act upon it (Byerly, Ricketts, Polasky, Ferraro, Balmford, Ficher, Palchack, Hammond Wagner & Schwartz, 2018; Coucke et al. 2019). Visual cues will prove to form the basis of the research hatch of this dissertation.

In addition, salience nudges have been used for quite a while as well. Salience nudges try to influence consumer behaviour by providing meaningful and relevant information to consumers. In this case, consumer reactions are elicited through emotional associations in response to these nudges (Blumenthal-Barby & Burroughts, 2012). The underlying mechanisms can be explained through the use of the ‘Associate Network Theory’ (Anderson & Bower, 1973; Wilson et al., 2016). The theory states that multiple pieces of information (e.g. experiences) are interconnected and shape up an individual’s memory. Furthermore, these little pieces have an emotional or practical meaning and can become intertwined when experienced simultaneously. Finally, repeated exposure to different types of information in an identical situation and emotions can strengthen these associations (Wilson et al. 2016). For example, Thorndike, Riis, Sonnenberg and Levy (2012) used traffic light labels in order to effectively colour-code food. As the colours already had strong associations from prior experiences, consumers were able to easily connect the meaning of the colours to food and beverage items that utilized the same colour-coding. Consequently, meaningful and relevant information was provided to the consumers. In the following chapter we will discuss a possible effect that can occur through the use of specific nudges.

According to earlier academic research, nudging is mainly utilized to promote ‘better alternatives’. For example, nudging can be as applied to increase purchases of healthier or environmentally friendly products, as already tested in a range of studies (Wilson et al., 2016; Coucke et al., 2019; Vandenbroele et al., 2019). For this particular masters dissertation the objective will be to enhance the purchase intentions of consumers for vegetarian alternatives (e.g. vegetarian burgers). This will be achieved by the use of a popularity cue, more specific, shelf-based scarcity. This concept will be thoroughly explained in the remainder of this literature review.

2.2.2. Bandwagon effect/heuristic

Product uncertainty, either in a brick-and-mortar store or an online environment, can be considered as a well-known attribute of our present consumer market. Moreover, considering the abundance of different products and alternatives, consumers have become unsure about the product’s different aspects, their value and other relevant features (Xue, Demirag, Chen & Yang, 2017). However, when uncertainties concerning the value of products arise, consumers will tend to their surroundings in order to forage information, that might help them to alleviate the previously present uncertainty in their decision making process (Fu & Sim, 2011). Following the ‘Elaboration Likelihood Model’ (ELM; Petty & Cacioppo, 1986), it had already been established that individuals process information to make decision in one of two ways: in a heuristic or a systematic manner. The systematic way will not be focused on in this this dissertation. In the case of consumer or individual uncertainty, heuristics will be employed to use and filter information from the surroundings. This uncertainty occurs because of the fact that the situation is marked by low-involvement and scarce cognitive resources. Thus, previous research has already shown that cognitive constraints lead to the use of heuristics, which are subsequently serving as mental shortcuts. These heuristics are utilized instead of full rational optimizations to reach decisions (Fu & Sim, 2011). Taking into account how heuristics can be used, one might ask how this phenomenon can be utilized for consumers who are seeking to make choices in a cluttered and uncertain environment, marked by an information overload. A theory that might provide an answer to the previous question, is that of the bandwagon effect or bandwagon heuristic (Sundar, 2008). In general, the bandwagon heuristic can be regarded as the ‘blind crowd mentality of individuals, who believe that if many others have accepted something, it is probably good for the individual itself as well’ (Chaiken, 1987). More particularly, this theory can be explained by the use of the economic theory of information cascade, the psycho-cognitive theories on information processing or by the observational learning theory. These theories demonstrate that choices who are being made by individuals who act first, eventually influence and inform the actions of the subsequent consumers. Concrete, this means customers follow the actions of their predecessors, regardless of their own information. This process occurs because consumers believe that consensus equals correctness or that, if and when a large group of consumers thinks a certain good or service is decent for them, the same conclusions can be made for the individual itself. Consequently, bandwagon effects can occur for a variety of reasons, but two main motives have been found in previous research. Firstly, the thought of ‘fitting-in’ with peers has been found to be crucial. Consumers might prefer to buy popular products, as this could induce inclusion of the individual in the majority group and give a sense of belonging and certain social status. Thus, the need for belonging and conformity goals become the driving power

9 behind this process (Van Herpen et al., 2009). Alongside the need to fit in with others, consumer might also prefer the more popular products, because these signal quality. The consumers use information that might indicate the product’s popularity to make inferences about the overall quality of said product (Kardes, Prosavac & Conley, 2004).

An important antecedent for the occurrence of bandwagon effects is uncertainty about the product’s quality. Individuals tend to rely on actions and proceedings of others to make assumptions about the quality of the product in situations where they only possess limited information or pre-knowledge about it. Taking into account all this information, we can, thus, conclude that when consumers encounter a wide variety of products from which they can choose and of which they lack private insight about its quality, they wind up making quality inferences from observable (in-store or online) information about their predecessors’ actions. (Bikhchandani, Hirshleifer & Welch, 1992; 1998; Fu & Sim, 2001; Xu & Fu, 2014). This informational uncertainty stems from two fundamental factors. First of all, one must consider the total amount of information consumers must seek, receive and eventually process when making their choices. Next to this, we need to take into account how familiar or knowledgeable the general audience is about the cultural background of the content that is being contemplated (Xu & Fu, 2014). In conclusion, product quality uncertainty stimulates an information cascade process among consumers, which eventually leads to a bandwagon effect. Now how can such a bandwagon effect be created, in order to increase the prominence of certain goods or services, one might ask. Previous research in the matter of online content has shown that mass audiences gravitate towards content that has already established some popularity, as individuals, for example, associate quantity of viewings with a higher quality of the appeal. Eventually, this process leads to a strong concentration in favour of the most popular choices (Neuman, Neuman & Marin, 1991; Xu & Fu, 2014). If and when these bandwagon effects appear, it means consumers buy products that others have already chosen before them. In this case, it can be noticed that from then on demand is being accelerated, as others buy the same products. When consumers believe that a larger amount of demand is evidence that more consumers value the product, they subsequently infer that the product itself must be of superior quality and more of the same product will end up being bought. In its turn, excess demand will lead to based scarcity or relative scarcity. Previous research on demand-based scarcity has already established that consumers prefer these wanted products as a substitute for the abundantly available products. Combining all these facts together, we can conclude that bandwagon effects are the cause of this accelerated demand (Van Herpen et al., 2009). It is believed that this relative scarcity leads to inferences that a product might be considered as more popular. Consequently, this popularity could lead to superior quality perceptions through the bandwagon effect and, finally, means an increase in purchase intentions (Parker & Lehmann, 2011). These effects can be

manipulated by retailers or producers, in order to manually create or indicate popularity, and are being referred to as ‘popularity cues’. These popularity cues will be widely discussed in the following sections of this thesis.

2.2.3. Popularity cues

In a marketing context, certain cues are being used to trigger the desired heuristics. Consumers who are not familiar with a certain product show a tendency towards extrinsic cues on which they can rely to form their product choices. In the case of this dissertation, bandwagon heuristics are cued by specific popularity metrics or indicators, which in their part insinuate social endorsement and confer a certain degree of quality credibility (Sundar, 2008; Fu & Sim, 2011). These cues are being referred to as ‘popularity cues’. In layman’s terms they can be viewed as promotional cues that indicate pervasive consumer interest in a product (Wu & Lee, 2016). It can be viewed as information on the relative frequency with which the product is chosen by a certain set of costumers (Tucker & Zhang, 2011). More concrete, popularity cues provide information to other consumers about general market preferences, which in their turn act as social norms that drive buying behaviour (Goldstein, Cialdini & Griskevicius, 2008). In an online purchasing environment, examples of popularity cues could be: “our best seller”, “this room was booked 4 times in the last hour” or maybe “90% of the people who clicked on this product bought it”. Two main reasons have been identified for the use of popularity features for the recommendation of products. Firstly, popularity is often used to embody crucial elements of the product. Secondly, it signifies that popularity of a product greatly influences other consumers’ purchase decisions, as already shown in the section above of the bandwagon effects. The focus of this dissertation will mainly lie on the second motive. Next to these, tree key dimensions need to be understood to be able to utilize popularity cues. The first aspect is whether or not consumers perceive the product as one of high value or quality or not. The second aspect addresses the frequency by which the product is purchased, regardless of its value. Lastly, the size of the strong-support group matters. These can also be considered as the early adopters (Kotler & Armstrong, 1991).

Several papers can be found in academic literature who already have addressed the use of popularity cues in order to increase purchase intention. For example, prior research by Coucke et al. (2019) used a similar approach in an in-store environment in order to increase consumption of poultry, instead of other meat products (pork, beef or lamb). They utilized visual cues to promote poultry, as it can be

11 considered a more environmentally friendly alternative than other meat products. Visual cues operated as popularity cues through their ability to increase the products availability and can be considered detrimental to consumers, as they often favour observation as the most meaningful way to gather information in certain situations. On top of this, the increased availability provided consumers with the impression of an elevated level of quality, as consumers are led on to believe that a considerable amount of stock equals product superiority (Wu & Lee, 2016; Steinhart, Kamins, Mazursky & Noy, 2014). A double nudge was imposed, whereby the size of the display area was enlarged, while simultaneously enhancing the quantity of the displayed products in the display area. The results of their field experiment revealed that imposing a double nudge effectively and significantly affected the sales of more sustainable meat products (i.e. poultry). Increasing visibility is not the only way to promote certain product alternatives. In strict contrast to an increased stock, other research opted to only fill their shelves partially to indicate popularity. In academic terms this technique or manipulation is referred to as ‘shelf-based’ scarcity (Van Herpen et al., 2009). Finally, academic research has found that the use of online popularity cues could prove itself to be useful as well (Fu & Sim, 2011). Next, both online popularity cues and shelf-based scarcity will be thoroughly discussed.

Online popularity cues

Popularity cues can not only be found in in-store environments. For some time now they have made their way into world of online shopping. To notify consumers, retailers have been known to display sales (and stock) level information. By wielding this approach they do not only indicate that the product is available at that exact moment, but consumers are also led to believe that it is more popular or wanted than other alternatives (Van Herpen et al., 2009).

Rapid expansion of the online marketplace throughout the last couple of years has led to a large amount of problems. Among these consequences, information asymmetry and trust issues stand out the most in this particular case. For example, e-commerce has led to a much larger separation of buyers and sellers than before. This phenomenon resulted in the fact that potential customers were not able to experience products in real-life like before. For this reason online consumers are exposed to a high degree of uncertainty stemming from these trust issues (Yoo, Jeon & Han, 2016). While purchasing products offline, consumers encounter a variety of cues when shopping (e.g. packaging ad price) and the goods can be observed almost instantaneously. Subsequently, online consumers are faced with

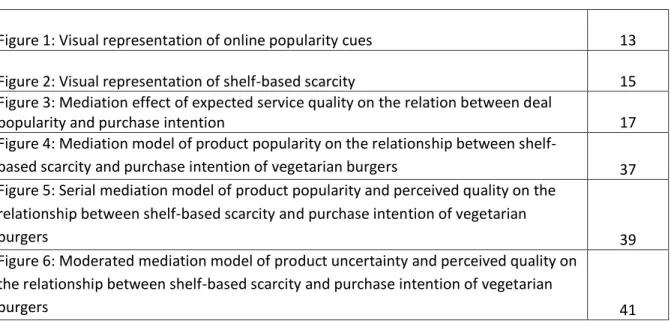

several barriers, which keep withholding them from seeing, touching or interacting with the products or services. Consequently, online customers tend to rely more on the scarce information and additional extrinsic cues that are present. Consumers engage in this process in search for quality cues before purchasing the desired products and services. This is where popularity cues find their purpose (He & Oppewal, 2018). Online popularity metrics can occur in a variety of forms. One of the most obvious varieties stems from the world of social media, where likes, shares and comments dictate how popular content is privileged over unpopular content. The information influences people’s opinions based on the content previously liked by their peers (Porten-Cheé, Haßler, Jost, Eilders, & Maurer, 2018). Fu and Sim (2011) argued that the amount of existing views, likes, shares and comments can be used as popularity cues and could be indicative of social endorsement and credibility. This process could subsequently create bandwagon effects that stimulate increases in viewership. We can also find such approaches in the context of online political campaigns. “IMDB” and other websites for reviewing movies often tend to use star-based cues or ratings in this context. Finally, websites like "booking.com" tend to use phrases like "only one room left" or "has been booked 5 times in the last hour" to indicate the aforementioned product popularity. Next to these, ratings or tags like "best seller" have been found to do the job as well. In Figure 1, there can be found a visual representation of these tools.

13 Parallel to the use of popularity cues in retail stores, uncertainty about the product has been proven to be detrimental in order to reach its full potential in an online environment. Other similarities can be drawn from the use of popularity cues in brick-and-mortar stores as well. First of all, online consumers are subject to the informational cascades theory or bandwagon effects when present in the marketplace. Online popularity information, therefore, has been found to be self-reinforcing, as it has the tendency to fortify trends, by persuading consumers to choose already popular products (Zhang, 2010). Academic literature by Yoo et al. (2016) confirmed this theory along with a long list of previous research on this topic. In their research, popularity cues were given in the form of a hit list. A hit list consists of a board displaying the most popular products along with their names, pictures and prices. They found that consumer purchase decisions were significantly affected by the hit list information and thus confirmed the existence of the reinforcement effects. To evaluate the effectiveness of product popularity claims on purchase intentions, results of Jeong and Kwon (2012), showed a positive, significant and direct effect between the two variables, similar to that of Yoo et al. (2016). Popularity claims came in the form of the following statement: “ What do customers ultimately buy after viewing this? 94% of them buy X USB flash drive”. When compared to the groups with a less meaningful and no popularity claim significant differences were found, thus confirming the theory.

Shelf-based scarcity

Nowadays, as already mentioned before, consumers find themselves in front of a variety of different products to fulfil and satisfy similar needs. In addition consumers’ choice and purchase decisions are hugely affected by a variety of factors (e.g. store layout) (Xue et al., 2017). Logically, this has some major implications for the producers of these goods and the retailers. In order to make the product stand out from the wave of alternatives that flood the everyday consumer on a daily basis, the modern retailer faces an extremely complex task. From their point of view, several actions can be taken to potentially shift demand within a certain product category to a more profitable or sustainable option. These measures can include price promotions, circulars or several other marketing tools. However, these mechanisms can all be associated with the incurrence of extra costs faced by these retailers, thus decreasing revenues and eventually their overall profit (Parker & Lehmann, 2011).

Prior research has recognized displayed shelf inventories as one, cheaper, factor that largely influences consumer decisions (Xue et al., 2017), meaning retailers could shift demand without the occurrence of

any additional stocking costs. This would be achieved by keeping (their most profitable) brands less fully stocked. The intervention can be achieved in two particular ways. First and foremost, the retailer could keep other brands fully stocked, while simultaneously not restocking the preferred brand as frequently as the others. Secondly, the same outcome could be generated by initially stocking the target brand only to a certain percentage (Parker & Lehmann, 2011). Why refer to measures regarding the shelves, people might ask. In a first instance, shelf space can be considered as the primary point of contact from a retailer with its customers. On top of this it is also believed to be one of the most, if not the most, valuable resources in a retail store to influence buying behaviour. Thus, shelf space is detrimental to successfully running a retail business (Xue et al., 2017). In contrast to previous research where they have often opted for a full stock, Van Herpen et al. (2009) chose to go the other way. Following this, they chose to only fill their shelves partially. Academics have referred to this technique as shelf-based scarcity or relative scarcity.

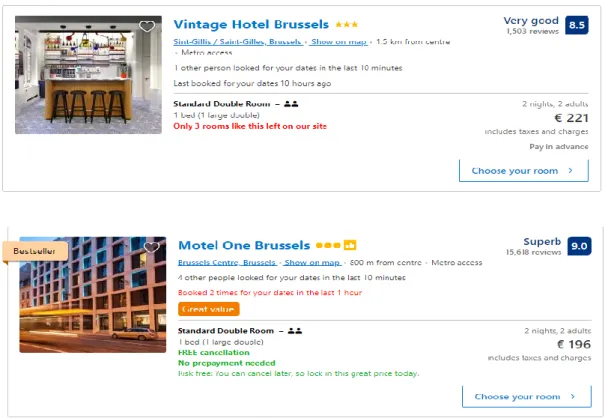

Shelf-based scarcity can be defined as a situation that occurs when an option’s stock level becomes depleted, but not “out of stock” (Gielens & Gijsbrechts, 2018). The concept of shelf-based scarcity can be observed in Figure 2, where, concerning wine bottles, one can notice that the wine on the left is relatively scarcer than the one on the right. Similar conclusions can be made concerning the other available products. Therefore, even when consumers do not directly observe the behaviour of others, but only the traces they leave behind, similar effects can be achieved by the retailers.

Until a certain point scarcity of products was only approached from the point of view of the ‘uniqueness theory’. The leading hypothesis, thus, stated that limited availability of scarce products implied the exclusivity of that product in contrast to abundant ones. Furthermore, consumers use this exclusiveness to express their own sense of uniqueness to others and to elevate their status. This desire stemmed from a personal need of people to be different than others. The use and possession of exclusive products aided to acquire this elevated status (Van Herpen et al., 2009). Consequently, snob effects could be achieved, where an increase in demand would be obtained by the mere fact that others are not consuming the same products (Leibenstein, 1950). However, academic research on this topic concluded that uniqueness of products did not always lead to the desired scarcity effects. The conclusion quickly came that a crucial distinction had to be made between absolute and relative scarcity. Whereas evidence of the relationship between scarcity and the uniqueness theory was found, new findings nuanced earlier research by saying that it was only true for scarcity in an absolute sense. Absolute scarcity meant the total number of products was limited in the entire market (i.e. supply restrictions). However, research found that products are not always scarce in its entirety, but that products were found to be unavailable at certain locations for a brief period of time. The cause of this type of scarcity was found to be the high demand for these products (i.e. excess demand) at those

15 certain locations and was specifically true for products who appealed to a wide audience and were less exclusive than others (Lynn, 1989). The focus of dissertation will lie on the use of relative scarcity to increase purchase intentions.

Besides the research of Van Herpen et al. (2009; 2014) and Parker and Lehmann (2011) the field of relative scarcity or shelf-based scarcity has been marked by a lack of relevant insights. Their results, however, showed that relative scarcity due to excess demand could result in bandwagon effects. Hence, evidence was found that products with high demand, meaning low product availability at the time being, lead to increases in sales. In this particular case low availability is signalled by excess demand. More concrete, evidence indicated that relative scarcity due to excess demand increased choice and the effect was found to be stronger when the level of depletion was higher (Van herpen et al., 2009). The sales of wine in a retail environment ended up providing a perfect example of this mechanism and, later, similar research also found traces of this relationship. When participants were given instructions to choose a bottle of wine for a party, results strongly supported a significant relationship between shelf-based scarcity, popularity and increases in interest with respect to their wine choice. The driving forces were found to be the need to belong or fit in, as mentioned in the section “Bandwagon effects”, in contrast to the need to stand out from others. In conclusion, evidence was found that shelf-based scarcity acted as a popularity cue, rendering the scarce wine more popular. Due to its popularity, bandwagon effects would occur, increasing the purchase intentions for the scarcer alternative (Parker & Lehmann, 2011).

Nonetheless, several nuances have to be made concerning the risks of relative scarcity. If and when consumers would notice the relative scarcity was intentionally created by the retailers, dissatisfaction and a significant backlash could arise among customers. Furthermore, full shelves offer a variety of benefits to the consumer. They provide an orderly appearance, which can be considered an important element of the shopping experience for some consumers, and reduce the risk of stock-outs. Finally, the use of related popularity cues that signal quality next to shelf-based scarcity needs to be closely monitored. In this case, research indicated that when other cues who signalled quality were present, the preferences for the scarcer alternative will be weakened. For example, when customers find out that the scarcer alternative has a lower sales ranking, then the positive impact of the relative scarcity on their choice will be reduced and less decisive for their final choice. In order for the retailer to decide whether or not to manipulate shelf-based scarcity, the costs, the use of related popularity cues that indicate quality, the likelihood that consumers will feel like they are being manipulated and the likelihood of a stock-out need to be taken into consideration. Finding the right balance proved to be a crucial exercise in order to achieve optimal effectiveness (Parker & Lehmann, 2011).

2.2.4. Factors influencing popularity cues

From the information mentioned above it is clear that a relationship between the use of popularity cues and consumer purchase decisions exists (Yoo et al., 2016). Nonetheless, academic research has often referred to indirect effects in this relationship instead of direct effects, meaning the effect of popularity cues on brand attitudes or purchasing behaviour is often influenced by third variables (Kao, Hill & Troshani, 2016). Some of these third variables, namely ‘perceived quality’, ‘uncertainty or product conspicuousness’, ‘perceived risk’ and ‘product price level’ will be discussed below.

Perceived quality

In today’s e-commerce environment consumers are being pushed to assess the trustworthiness of retailers and the overall quality of their products more than ever. On top of this, the evaluation process has to be undertaken in an environment that lacks many of the cues that are present in traditional

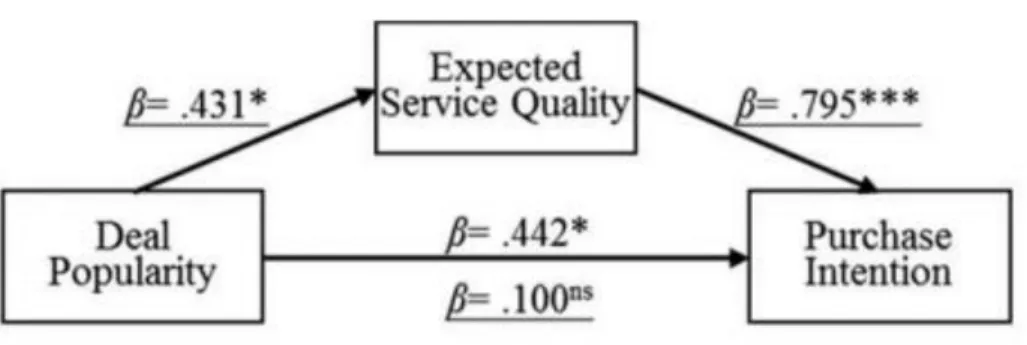

17 commercial transactions (e.g. feeling the product) (Flanagin, Metzger, Pure, Markov & Hartsell, 2014). As mentioned before, popularity cues were found to be a relevant answer in such situations. However, in some cases the effect of popularity on purchase intention was found not to be insignificant. The research of Kao et al., (2016) indicated there was no direct effect of deal popularity on consumer purchase intention. However, other interesting insights were found by including ‘expected service quality’ in the equation. On the one hand the study deducted that popularity was a significant predictor of expected service quality. On the other hand, a similar interaction was found between expected service quality and the purchase intention of the consumers. Thus, their results suggested an indirect effect of deal popularity on consumer purchase intention. In this case consumers tend to use popularity to make quality inferences on e-commerce websites, which in turn increases the likelihood of purchasing, as can be seen below in Figure 3. The presence of such popularity cues can therefore be advantageous for the buyer, by taking away uncertainty through the ratings. Next to this, it is of the highest importance for the retailers or producers as well, as higher ratings lead to higher website traffic and eventually sales (Flanagin et al., 2014).

Figure 3: Mediation effect of expected service quality on the relation between deal popularity and purchase intention (Kao et al., 2016)

Other academic research has found coinciding results. Similarly, results showed that online product ratings can be used as a product quality barometer, and that ,consequently, a larger level of perceived product quality leads to greater purchasing intentions among consumers. This meant that the use of higher average product ratings increased not only the perceived product quality, but the consumer purchase intentions after all. As results portrayed a positive relationship between perceived quality and purchase intentions, a mediational model was confirmed in conclusion. Product ratings seemed to affect purchase intentions by influencing the perceptions of the consumers regarding the quality of the desired products or services. As mentioned in section 2.1.3. (bandwagon effects) uncertain

consumers often truly believe others are better informed. They underestimate influences of situational factors and are convinced that greater demand arises from superior quality (Van Herpen et al., 2009). Not only does this mediation effect occur in online purchase environments, traces of its existence have also been found in traditional retail stores. Relative popularity remained a significant predictor of quality experienced and, consequently, mediated the relationship between relative scarcity and purchase intentions. In this context the amount of shelf space devoted to the product and the amount of emptied shelf due to prior purchases, concerning said product, sufficed as signals of popularity. The deduced popularity lead to derivations concerning increased quality and finally surpluses in demand (Van Herpen et al., 2009; 2014; Parker & Lehmann, 2011; Robinson, Brady, Lemon & Giebelhausen, 2016). We can conclude that it is possible for potential consumers to make inferences on quality, through the fact that shelf-based scarcity firstly evokes certain inferences that the scarcer alternatives are more popular. Furthermore, these popularity speculations lead to inferences that the scarcer alternative is of superior quality than other similar products (Parker & Lehmann, 2011). In traditional retail environments it would allow retailers to shift demand more easily at very low costs. For example, it could try to shift demand to more profitable brands. Paired with lower costs it could eventually imply higher profits (Parker & Lehmann, 2011).

However, some nuances have to be made. For example, the presence of a ceiling effect might be troublesome, indicating a reduced effect when ratings approach the upper boundaries of the scale (Flanagin et al., 2014).

Uncertainty

As mentioned above in section 2.1.2. uncertainty concerning the desired products has an important role in order for bandwagon effects to occur. Next to this, it is closely related to the aforementioned variable of perceived quality. In practice, it is often found that consumers have long and well-established preferences towards some products or brands. Therefore, no or little time is spent deciding on those products or brands. Frequently, the choices happen so fast that the customer hardly engages in any decision-making process. Accordingly, it was predicted that popularity cues would not affect the choices of consumers, if strong prior preferences for a certain brand or type of product would be present (Parker & Lehmann, 2011). Previous research, already indicated that familiar brands or products are more likely to be chosen as opposed to their unfamiliar alternatives (Erdem & Swait,

19 2004). In line with this, it has been found that when brand familiarity occurs, consumers are less reliant on quality cues in the store environment on which they can base their decisions. Even stronger, when strong brand familiarity or preference occurs, popularity and quality cues are rendered obsolete (Robinson et al., 2016). If consumers find themselves in situations where they are unfamiliar with certain products offered online, they tend to abandon the product knowledge they have themselves and rather look at traces of other consumers’ choices. The fact that the product is chosen more than others, according to the potential buyers’ deductions, could lead them to drawing conclusions of superior product quality. Eventually, this would ensure a more positive attitude towards the product or brand (Chiu, 2008; Yu, Hudders and Cauberghe, 2018).

Parker and Lehmann (2011) found evidence of this theory on the importance of uncertainty, popularity information and sales as well. Their study on motor oil showed that shelf-based scarcity significantly impacted those consumers who showed no strong prior preferences. As mentioned above, consumers with strong preferences were less affected by popularity cues. Accordingly, this meant that the impact of shelf-based scarcity would be the largest when the consumer had no prior preferences and had little knowledge on the product or brand that was available in-store. In their study concerning sales and stock level information on chocolate, He and Hoppewal (2018) discovered results along the same line. Their findings suggested that when brand familiarity was high, sales and stock level information had little effect on the choice of the consumers. It could be concluded that as familiarity increased, the influence of perceived popularity and quality in their decision process seemed to decrease. However, it should be noted that the influence of the popularity decreased. Nonetheless, it still had some positive results or effects with respect to the familiar brand (He & Oppewal, 2018). In conclusion, the perceived uncertainty (i.e. conspicuousness) moderated the relationship between popularity cues, via perceived quality (Yu et al., 2018). Overall it should be noted that uncertainty is highly important in order for popularity cues to be effective and that its effect is largely ignored when prior preferences are present (Parker & Lehmann, 2011).

Perceived risk

As mentioned above, when making purchase decisions, consumers are confronted with uncertainty concerning the consequences and outcomes of their decisions. For example, uncertainty can arise whether or not the consumer has chosen the right brand, vendor, product, alternative or even mode of purchase. All of these factors are highly contributing to the consumers’ perceived risk, which in its turn negatively influences their purchase intentions (Flanagin et al, 2014). Perceived risk can be translated as the nature and amount of risk that is being perceived by the consumer in contemplating a certain purchase decision (Cox and Rich, 1964). Consequently, the level of ambiguity and perceived risk in commercial transactions indicate the importance of commercial information that consumers believe to be credible. People might ask themselves how this perceived risk can be mitigated, in order to exert a positive impact on consumer behaviour.

In prior research, Higgins (1987) made a distinction between two types of individuals. On the on hand, he found promotion-focused individuals. On the other hand, he found the prevention-focused individuals. Prevention-focused individuals put more stress on the avoidance of losses and put more emphasis on safety. Consequently, the goals of these consumers align well with the theory as stated above. In order to minimalize risks while shopping, they could refer to popularity cues as signals, in order to argue that buying popular products is less risky. Once more, this would be due to the fact that many other consumers have bought it before them. Following this, it can be stated that consumers need more information to reduce the risks involved and thus both extrinsic and intrinsic cues are utilized (Kim & Min, 2014). Evidence of the fact that perceived risk is negatively correlated to purchase intentions has already been widely found. The role of popularity cues in this relationship, however, has not had that much attention yet.

In previous research the transmission of face-to-face WOM information was found to be highly effective in building and changing certain opinions on products (Herr, Kardes & Kim, 2011). More recently, Flanagin et al. (2014) examined the impact of the use of commercial product ratings in order to mitigate perceived risk. Their results confirmed that the ratings were regarded as product information or popularity information and that they contained a high degree of credibility, due to the fact the ratings co-varied with perceived quality and purchase intentions as mentioned in the section above. Because of the credibility of the information, perceived risk is being reduced and a subsequent mediation effect occurs between the ratings, perceived quality and finally consumer purchase intentions. This effect is also found to be stronger by people with high risk-aversion rather than those

21 who are less risk-averse, meaning popularity cues can be manipulated as a powerful risk reduction tool (Jeong & Kwon, 212).

Price

Next to the abovementioned variables, some other factors have also been found to be relevant factors influencing the effects of popularity cues. For example, the price of the products has been believed to have a certain influence on effectiveness of its use to increase purchase intentions (Robinson et al., 2016; Wu & Lee, 2016; Yoo et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2018). It was believed that price-sensitive consumers would give more importance to the information they would get from those who already purchased the desired product than price-insensitive consumers. Consequently, price-sensitive consumers would be more receptive to the effects of popularity cues on their purchase behaviour (Tucker & Zhang, 2011; Yoo et al, 2016). Evidence of this theory was presented by Yoo et al. (2016). Their results indicated that differences in prices resulted in different outcomes concerning the success of popularity cues, such as hit list information in their particular case. First of all the price was divided into three categories: low-price products, mid-low-price products and high low-price products. The relationship between the impact of hit list information and the different price tiers can be described as a U-shaped curve. The reason for this is that for low price products, consumers are believed to spend little time comparing products and make more routine choices than for mid-price products. Regarding high price-products hit list information had little effect as well. However, the reasoning completely differs. Here, consumers are less likely to be led by popularity information due to the fact that the buyers will rely on their own information and knowledge they poses about the product, instead of basing their choice on the purchase behaviour of others. In conclusion, popularity cues may present retailers with a good tool for mid-price products. For low- or high-price products, however, they are less useful as the lack of information could provide buyers with a high degree of post-purchase stress.

Although Yu et al. (2016), also found evidence of a moderation effect of the product price level, via perceived quality (indirect effect), on the relationship between popularity cues and brand attitude, their results suggested an obverse effect. First of all, as opposed to the research of Yoo et al. (2016), an significant effect was found for the mid-price level in fashion e-commerce. Next to this, a significantly positive effect was found for the high-price level and a negative effect was found for the low-price level. Therefore, there is reason to believe that it is important to consider the type of product in this relationship.

3. Experiment 1: Qualitative research

3.1. Methodology

After the literature review, the next step in this master thesis was to gather relevant insights of consumer behaviour concerning the topics of popularity, popular products and purchase intention. The research method that was used in order to assemble this information was a focus group. A focus group can be defined as a certain group of several individuals that have been selected and assembled by the researchers in order to comment and/or discuss on the topic that is being investigated. Furthermore, the participants do this from their own, personal experiences or a personal point-of-view (Powell, Single & Lloyd, 1996). The key characteristic of a focus group stems from its ability to generate all of the ideas, information and insights through the interactions between all of the participants. This key aspect is what makes this method stand out from other qualitative research methods, such as regular group interviews (Gibbs, 1997). The main purpose of the use of focus groups is to use the respondents’ feelings, attitudes, experiences, beliefs and, more importantly, reactions in such a manner that results are generated in a way that would not be feasible with the use of other methods. Once again, this advantage lies in the foundations on which focus groups are built, being the group interactions and social gathering of individuals (Morgan & Kreuger, 1993; Gibbs, 1997). Thus, focus groups have provided researchers with an excellent tool to be used at the earlier, exploratory stages of academic studies (Kreuger & Casey, 2014) and to generate hypotheses (Powell & Single., 1996). In this particular case a focus group was used to obtain such results.

In total, 8 people participated in the online focus group. The participants were chosen in such a manner that different types of people were involved and their views could be heard. From the 8 participants half of them were female and half were male. Next to this, 3 of the participants were employed, while the others were still studying, either at a university or collegiate level. This also means that 5 participants were under 25 years old, while the others ranged from 30 to 50 years old. The participants were asked several questions in line with the topic of popularity cues. On a side-note, it might be important to mention the respondents had no clue concerning the topic of discussion of the focus group, to avoid certain biases or premeditated answers. To begin with, they were shown several products, from which they had to choose. Depending on the question, shelf lay-outs were altered. For example, more shelf-space was given to one product or less products were depicted on the shelves of another one. Next to this, different product categories were used in different questions. Finally, the respondents were asked more general or associative questions, where they had to think of words or product characteristics they linked to “popular products”. Overall, interesting insights and ideas for

23 future examination were gathered from the discussion. The results of the focus group will be discussed below.

3.2. Results

In general, the focus group provided a lot of interesting insights for further investigation. In a first instance the participants were confronted with three different types of chocolate bars, displayed in three different shelves, as can be seen in Appendix 1. For the first question, the Snickers shelf was larger than the shelf of the other brands. This modification, however, had no effect on the brand of choice of the participants, as their brand of choice was solely based on their personal preferences. The size of the shelf and amount of products available had no influence. After this, the respondents were asked the same question, although the product and shelf layout had been altered. For instance, all three brands had the same shelf space, but the Tony’s Chocolonely shelf was less full, in order to indicate prior demand. In contrast to the first question, two out of the eight participants indicated opting for this brand. The reason for their change of choice came from the fact that this shelf was less full, which, according to them, indicated higher prior demand. Consequently, they were more inclined to opt for this specific chocolate bar. The remainder of the participants stuck with their first choice, as they felt prior demand had no impact on their product choice and their personal preference still was their main reason of choice. After this the participants were confronted with the same question. However, this time, the products changed from different types of chocolate bars to different types of products for cleaning cars, in order to confront the participants with products with whom they were less familiar and where prior brand preference would have been rare. Several interesting results were found here. First of all, considering this type of product, more participants (4/8) were inclined to select the product whose shelf was only half-filled and therefore suggested shelf-based scarcity. The main reason for their choice was that they based it on the buying behaviour of previous consumers and the fact that their knowledge of this type of product was particularly low. As numerous other consumers already purchased it, they deducted that the product had to be good, to put it in their words. Consequently, they were more willing to select this specific option. Therefore, it could be concluded that shelf-based scarcity had a positive effect on product choice in this particular case. Next to this, the uncertainty and lack of knowledge related to this type of products had a major impact as well. When the participants were asked to choose the chocolate bars their product choices were mainly based on

their previous product preferences. Some of them mentioned not being susceptible to these types of ‘cheap marketing tricks’. Others claimed that the products could have been laid out in such a manner to reach the desired outcome of increased sales. However, when confronted with unknown products, the same critical respondents hinted their final decision was guided by the popularity cue, they previously referred to as ineffective. Finally, it also became clear that product price or promotions could reduce the effects of shelf-based scarcity among uncertain products. After a vivid discussion, participants mentioned that when certain promotions would be in place, these would overrule their decision making process, as explained above. When looking at these results, it is hard not to notice some consistencies or similarities with some of the results that have been broadly discussed in the literature review.

After the specific questions where participants had to choose and discuss their product choices with each other, more general questions were asked. Next, the participants were asked which words or associations sprung to mind when thinking about popular products and how one could make it clear or imply to consumers that a certain product is more popular than its substitutes. It could be concluded that quality was the most prominent element of popular products according to these consumers. Other clear associations were also made along the line of top-of-mind awareness, superior price and user-friendliness. However, other interesting connections came to mind after internally discussing the topic. One participant noticed that popular products were not always the best products, but could just imply products that are being bought more often than others. Furthermore, one member also thought of the topic of hypes and people wanting to buy what others are buying. Concerning the manner how supermarkets could achieve such things, manipulation on the shelves was believed to have the biggest effect. For example, some people mentioned putting products at eye level. Next to this, the breadth and number of products in the shelves were also mentioned as viable options to indicate popularity. Next to this, on respondent brought up the topic of creating artificial scarcity. According to him more consumers would be inclined to buy these products due to a feeling of exclusivity. Banners would also be useful according to some participants. Finally, the group was asked in what type of situations the use of popularity cues could provide benefits. The general answers were that sustainability and the promotion of sustainable products were important at this moment and that the use of these types of products will be detrimental to a sustainable future. These main findings of the focus group, next to those of the literature review, will form the basis of our hypotheses for the quantitative hatch of this master thesis.