Kaleidoscopic view on social

scientific global change research

in the Netherlands

Kaleidoscopic view on social

scientific global change research

in the Netherlands

Netherlands HDP Committee

August 2001

ISBN 90-6984-334-X

Kaleidoscopic view on social scientific global change research in the Netherlands

You can order this report (no charge) at:

Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Netherlands HDP Committee PO Box 19121 1000 GC Amsterdam The Netherlands tel. +31 20-5510712 fax. +31 20-6204941 e-mail: a.vollering@bureau.knaw.nl Secretariat: Ms. B.M.J. Peeters tel. +31 20-5510782 e-mail: bernadette.peeters@bureau.knaw.nl Ms. S. Wagenaar tel. +31 20-5510860 e-mail: suzanne.wagenaar@bureau.knaw.nl

Contents

Preface 5

LUCC Land use and land cover change

The relation between agriculture, land use and policy in Europe 8 Biodiversity as a social science research issue 12

IT Industrial transformation

Economic growth and the environment in a liberal world 16 From financial to sustainable profit 21

The transition to a low-emission energy supply system 26 The economics of H2O 29

GECHS Global environmental change and human security Modelling components of human security 38

Poverty, access to resources and conflict: Understanding poverty-related conflict form an entitlement perspective 50

Human health and the enviroment 65

Human perceptions and attitudes towards sustainable development in the Netherlands 87

Food security and human security in semi-arid regions: the impact of climate change on drylands, with a focus on West Africa 94

Sustainable management of the coastal area of SW Sulawesi, Indonesia 99 IDGEC Institutional dimensions of global environment change

Legal research on global environmental change of METRO 110

State of research concerning institutions and instruments to control global environmental change in the Netherlands: conference report 116

Preface

If one looks from a distance at the Netherlands, one sees a small, densely populated Western Euro-pean country. Most of its surface is below sea level, but thanks to the many dykes and dunes, most Dutch people manage to keep their feet dry. The Dutch are famous for adapting their lifestyles and surroundings (including the height and strength of their dykes) to major changes in local, regional and global circumstances. The motto of Zealand – one of the Dutch provinces engaged in a con-stant battle with the sea – is Luctor et emergo (Struggle and rise).

Recent scientific results have shown that both the environment and the climate are changing on a global scale, and that the pace of the changes is unprecedented. Although this is still to be scientifi-cally verified and elaborated in more detail, our planet and the societies living on its surface seem to be very sensitive to these changes. Problems of global change are perceived as becoming more and more urgent. However, there are still many unanswered questions. What will be the conse-quences of these changes? Which societies are the most vulnerable? Can these global changes be stopped, or even reversed? Is it too late to intervene?

Countries and societies are becoming increasingly involved in trying to answer these and other questions concerning major global changes. However, the social scientific knowledge base appears to be too narrow to provide answers to these questions, even though scientific discussions on global change issues are now more widespread than they were a few decades ago.

The International Human Dimensions Programme on Global Environmental Change (IHDP) has been participating in these scientific discussions since the middle of the 1990s. Within the scope of its four Science Projects (LUCC, IT, GECHS, IDGEC), IHDP is contributing to the construction of a more solid social scientific knowledge base.

The Netherlands HDP Committee became the national committee for IHDP research in the Nether-lands in September 1994, making it one of the oldest IHDP national committees. Since then it has been very active both in the Netherlands and in the context of IHDP. One of its aims is to influence national organisations – e.g. the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), as well as various university and government departments – in their decision-making regarding the funding of social scientific global change research in the Netherlands.

The Netherlands HDP Committee is proud to present you with this book. In the last few years, sev-eral IHDP Science Projects have made important progress. The Netherlands – based on its tradi-tionally strong position regarding the social scientific knowledge base (including the beta-gamma interface) – has contributed significantly to this progress.

This book reports on some of the Dutch global change social research activities currently being carried out in the context of the four IHDP Science Projects. The contributions it presents are very diverse as regards size, style, breadth and depth. They concern methodologies, case studies, theo-retical issues, systems analyses and so forth, thus providing a kaleidoscopic view on the social sci-entific global change research in the Netherlands. It should be noted, however, that the Netherlands HDP Committee does not purport to be providing a complete and extensive (or, for that matter, over-edited) review of all Dutch social science global change research.

I wish you much pleasure in reading this book. If you wish to contact the authors in order to dis-cuss the scientific aspects of their contribution(s), please don’t hesitate to do so. The contact ad-dress of the first author is given at the beginning of each chapter.

Professor J.B. Opschoor

Chair of the Netherlands HDP Committee August 2001

LUCC

The relation between agriculture, land use and policy in Europe

F.M. Brouwer

Head of the Research Unit Management of Natural Resources of the Agricultural Economics Re-search Institute (LEI), The Hague

Telephone number: +31-70-3358127 E-mail address: f.m.brouwer@lei.wag-ur.nl Target areas of research

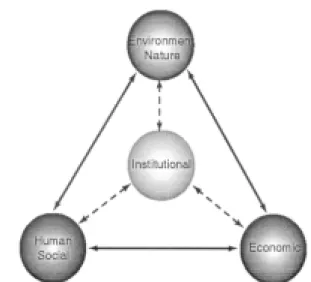

The research examines the economic, social and environmental integration into agricultural land-use changes in Europe, considering that agricultural production also sustains the various functions of the rural countryside (multifunctionality). Areas of expertise include:

1 Identification of key driving forces and pressures regarding the interaction between the eco-nomic, social and environmental cohesion of agriculture in the rural countryside. Conceptual and analytical work contributes to the establishment of a framework regarding the multiple functions of agriculture in the rural countryside. This framework will be the basis for the analy-sis aimed at identifying key driving forces and pressures regarding the interaction between agri-culture and water in the management of natural resources. The main factors, hampering the sustainable management of natural resources in agriculture are identified. Factors may derive from the physical, socio-economic and institutional structure in the context of which manage-ment decisions are made in agriculture.

2 Establishment of guidelines, indicators and a checklist for the sustainable management of the multiple functions of agriculture. Guidelines and indicators are formulated that are potentially suitable for the sustainable management of the multiple functions of agriculture. The aim is to develop a systematic approach for assessing the environmental, economic and societal impacts deriving from the observed driving forces and pressures in agricultural resource management. 3 Identification of actors, instruments and institutional setting that could promote the sustainable

management of the multiple functions of farming in the rural countryside. The policy challenge is to devise a set of activities that will promote the achievement of the sustainable management of the multiple functions of farming in the rural countryside of Europe.

4 Policy context with regard to multiple functions sustained by agriculture in the rural country-side. Policy measures are examined that promote the multiple functions of the rural countrycountry-side. Main trends in European agriculture

Agriculture is not a major economic activity in the European Union (EU). The agricultural sector contributes a few percent of GDP in most Member States. Agriculture, however, is a dominant user of land. More than three-quarters of the territory of the EU is agricultural or wooded land. Forests cover about a third of the total land area in the EU. In marked contrast to the situation in other parts of the world, a large proportion of the land area of Europe has been farmed for several millennia. An increasing range of environmental issues relate to two dominant trends in current agricultural land-use in Europe: intensification and specialization in some areas, and marginalization and aban-donment in others. Both processes involve a move away from the traditional forms of low-input, la-bour-intensive crop and livestock production.

Intensification and specialization

The development of capital-intensive and geographically specialized farming leads to problems for the landscape and biodiversity, and also for soil, water and air. Such farming systems are mainly applied to large-scale arable or horticultural production on the most fertile or accessible land and to intensive livestock breeding. These systems are also applied to dairy production in other areas, where very large numbers of stock are concentrated on relatively small areas of land. Intensifica-tion of producIntensifica-tion is mainly carried out in regions where agriculture is most productive. Some Eu-ropean regions have a competitive advantage over others as a result of better biophysical condi-tions, more rationalized farm structures and the integration of primary production with food processing industries or through well-equipped farm extension services.

Marginalization and abandonment

This tends to occur in remote areas or on less fertile land where traditional extensive agriculture is threatened by its inability to compete effectively with intensive production in other regions. In these areas, farm incomes are low and there are few incentives for young people to take over farms from the previous generation. As older farmers retire, land may be abandoned, leading to the loss of traditionally managed, semi-natural habitats and an increased risk of disasters such as fires, par-ticularly in arid regions.

Pressures on the environment brought about by intensification and abandonment

The spread of intensive methods on crop and livestock farms has led to a loss of biodiversity and increased pollution in many Member States. It has also increased the energy used in the sector and its contribution to major problems such as global warming due to greenhouse gases, the degrada-tion of river, sea and ground water, soil erosion and contaminadegrada-tion, and acid rain. In many southern Member States, the most significant change in land use in recent years was associated with the de-velopment of irrigated and highly intensive horticulture on flat areas of land.

At the same time, the area of marginal land in Europe that is threatened by abandonment and inad-equate management has increased, due to increased competition within the single European market and in the wider global economy. Abandonment, degradation and economic decline now threaten both the extreme north and south of Europe and especially those areas where harsh natural condi-tions, poor soils and remote locations increase the costs of agricultural production and rural populations are shrinking.

Land-use changes in EU Candidate countries

Major changes in the agricultural sector of Central and Eastern European Countries (CEECs) dur-ing the first years of transition induced substantial reductions in both agricultural production and the input of agrochemicals. This was linked to an extensification of land use, changes in farm struc-tures and farm management practices. Such developments have altered the relationship between agriculture and environment (including biodiversity/nature management). Reductions in the use of fertilizers and pesticides have contributed to enhanced water quality, and consequently may have supported biodiversity in areas with traditional low-input agriculture and nature areas (e.g. rivers and other wetlands) that are hydrologically linked to farmland. In contrast, the reduction in live-stock numbers has caused farmers to abandon their farmland, and large areas which have a high

na-ture value and are dependent on grazing are threatened. The nana-ture conservation value of more natural grassland in particular is reduced by the dominance of a few species and subsequent scrub invasion when mowing or grazing are discontinued. The current transition period and the orienta-tion towards a market economy may initiate a new period of highly intensive agriculture, and in-creased agricultural production may induce losses of areas with high nature value. The challenge therefore is to find ways to develop agriculture without losing the existing environmental value of agricultural land.

Declining trends in agricultural production might be affected by a combination of environmental, geographic, agricultural, socio-economic and political conditions. Such conditions could reduce the viability of farming. A combination of factors could cause the cessation of farming under an exist-ing land-use and socio-economic structure, and this usually leads to a change in land use or even land abandonment. The conversion to a more extensive management of land in intensive areas is generally beneficial to the environment, by reducing pressures on water and soils from agricultural sources. Water quality problems caused by nitrates and pesticides are ameliorated when land is farmed less intensively. However, in contrast, the major changes in agricultural management can also give rise to the marginalization and abandonment of agricultural land. This can induce a loss of valuable habitats and species diversity. In addition, soil erosion, wild fires and declining biodiversity are major concerns in some marginal areas.

Policy approaches to control pollution and strengthen the benefits of agriculture to the rural countryside

EU legislation takes a variety of forms, the two most relevant being Regulations and Directives. Regulations are the dominant form of legislation in agricultural policy but are much less prevalent in environmental policy. They are directly applicable as law in the Member States and allow na-tional authorities rather limited discretion to depart from the obligations set out in the text. In con-trast, Directives are the primary forms of legislation for most EU environmental policies aimed at achieving environmental quality objectives. They are binding as to the results to be achieved, but leave it to the Member States to choose the form or method to be used. Three approaches are cur-rently available to internalize the external effects of agricultural production into farming practices: – First, general mandatory environmental requirements in meeting the legal constraints, and the

application of minimum environmental conditions in agriculture that all farmers need to comply with.

– Second, support for agri-environment schemes and the creation of environmental conditions on agricultural support measures for farmers, delivering environmental ‘services’ on a voluntary basis.

– Third, specific environmental requirements that put a condition for direct payments. This is commonly called cross-compliance. The amount of income support is only reduced if a farmer fails to meet the relevant environmental and conservation conditions.

The above approaches should contribute to achieving better implementation of Community envi-ronmental legislation (e.g. the Nitrates Directive 91/676, Water Framework Directive) and nature conservation legislation (e.g. Birds Directive 79/409 and Habitats Directive 92/43).

Land-use patterns respond to a range of measures and strategies

An integrated approach is proposed in order to meet agricultural and environmental objectives. In addition to agricultural policy reforms, other strategies would also contribute to the integration of environmental objectives into agriculture and sustain land-use patterns. There are several tools for promoting sustainable agriculture and organic farming. There is a wide debate on the strategies pursued in order to establish sustainable agriculture. Such farming systems, including organic pro-duction, could exploit increasing market opportunities in the years to come, as demand for these products has increased during the past couple of years. However, the market for sustainable pro-duce would also require good infrastructure to manage supply and demand. In addition, quality as-surance schemes are being developed in the agrifood chain, and retailers and food processors are demanding better, audited farming systems in response to changed consumer demands. Such pri-vate-sector, producer-led environmental initiatives also induce changes in farming practices and subsequently alter land-use patterns.

References

Brouwer, F. and J. van der Straaten (eds.) Nature and Agriculture in the European Union: New per-spectives on policies that shape the European countryside. Cheltenham, Edward Elgar (forth-coming).

Brouwer, F., D. Baldock and C. la Chapelle (2001) ‘Agriculture and nature conservation in the can-didate countries: Perspectives in interaction’. The Hague, Agricultural Economics Research Insti-tute. Report prepared for the High Level Conference on EU Enlargement: The relation between agriculture and nature management.

Brouwer, F. and P. Lowe (eds.) (2000) CAP regimes and the European Countryside: Prospects for Integration between Agricultural, Regional and Environmental Policies. Wallingford, CABI Pub-lishing.

Biodiversity as a social science research issue

P. Nijkamp

Professor in economic geography and regional economics, Free University Amsterdam Telephone number: +31-20-4446091

E-mail address: pnijkamp@econ.vu.nl P.A. Nunes

Researcher at the department of regional economics, Free University Amsterdam J.C.J.M. van den Bergh

Professor in environmental economics, Free University Amsterdam

The quality of ecosystems has become a source of major concern, both globally and locally. In the Dutch IHDP Programme, various human and social factors are mentioned that impact on ecologi-cal processes and ecosystem functions, such as consumption patterns and institutional arrange-ments. In recent years, much attention has been given in the Netherlands to a multidisciplinary analysis of biodiversity.

Biological diversity is of critical importance for the stability of the earth’s ecosystem, as it forms the base for sustainable functions of natural systems. It also offers a great potential for human use (such as recreation or scientific research). Biodiversity may be highly dependent on specific geo-physical and climatological conditions. For example, European ecosystems encompass more than 2,500 habitat types and 215,000 species. It is generally accepted that biodiversity cannot easily be expressed in numbers, since it depends on the ecological structure of a whole area. In recent years, evidence has grown that human activities are adversely affecting the earth’s biological diversity, as a result of prevailing production and consumption patterns and of land-use changes. Consequently, biodiversity tends to become a scarce good, for which however a proper pricing system does not exist. In the past years, the economic valuation of living natural resources and also of biodiversity has undergone significant progress, but a framework for valuing biological variety has not yet been established. As well as the lack of a solid economic valuation mechanism for biological diversity, there is a serious lack of reliable and up-to-date information and monitoring systems with a suffi-cient geographical detail on biodiversity. Clearly, studies on biodiversity require a pluridisciplinary approach. The economic approach to biodiversity is, by definition, limited and partial in nature. Al-though various approaches deploy contingent valuation methods, it ought to be recognized that this class of methods, while certainly helpful in assessing the use value of biodiversity, has serious shortcomings in case of non-use values such as bequest and existence values.

Despite some flaws in economic valuation approaches to biodiversity, there is a need to go ahead in developing valuation tools as a result of complicated trade-offs in environmental policy analysis against the background of sustainable development initiatives and emerging policies which take ex-plicit account of the variety in the earth’s ecosystem. The current biodiversity conservation pro-grammes require for their implementation formidable amounts of money, which have to be traded-off against alternative uses. Although world-wide much progress has been made in identifying and prioritizing such programmes, innovative valuation strategies are still needed to generate additional

information in order to support the actions advocated in Agenda 21 of the 1992 UN Earth Summit Conference in Rio de Janeiro. Biodiversity conservation programme funds have, in general, a poor underpinning and are not based on solid and explicit choice mechanisms. The reasons for this are complex. They relate to insufficient information on a given biodiversity issue as well as on unde-fined property rights, high transaction costs, divergence between private and social costs, inappro-priate economic instruments and the bureaucratic inertia of relevant political institutions. Public authority choices concerning biodiversity preservation programmes should ideally be based on sound economic principles and information, such as fair market prices, benefits of specific biodiversity policies and cost-opportunities of alternative decisions.

There is a growing awareness that biodiversity conservation programmes may generate many social benefits but at high costs, in particular in terms of management and information gathering. Against this background, many efficiency problems and fair public funds allocation issues have been raised. Although general information about biodiversity programmes is available through the traditional policy channels, it is challenging to allocate and manage biodiversity funds adequately from the perspective of the non-market value of environmental resources. In order to obtain a balanced trade-off between programmes’ costs and benefits, it is necessary to optimize the use of the infor-mation available. It is, therefore, fortunate that the number of studies concerning monetary

biodiversity evaluation is quickly growing. Consequently, there is a need to develop adjusted meth-odologies and analysis instruments that can improve our understanding of economic biodiversity values and, concurrently, that would allow for a more accurate forecast of biodiversity values. Progress on improving methods for providing such economic information (particularly predictive information) will require a strong and dynamic interdisciplinary dialogue. At this level integrating modelling and monetary valuation can present important advantages for policy guidance, present-ing important interactions that can be classified as follows:

– Values estimated in a valuation study can be used as a parameter value in a model study. Ben-efits or value transfer (e.g. meta-analysis exercise) can be used to translate value estimates into other contexts, conditions, locations or temporal settings that do not allow for direct valuation in ‘primary studies’ (due to technical or financial constraints).

– Models can be used to generate values under particular scenarios. In particular, dynamic models can be used to generate a flow of benefits over time and to compute the net present value, which can serve as a value relating to a particular scenario of ecosystem change or management. – Models can be used to generate detailed scenarios that fit into valuation experiments. An input

scenario can describe a general environmental change, regional development or ecosystem man-agement. This can be fed into a model calculation, which in turn provides an output scenario with more detailed spatial or temporal information. The latter can then serve, for example, as a hypothetical scenario for valuation, which is presented to respondents in a certain format (graphs, tables, story, diagrams, pictures) so as to inform them about potential consequences of the general policy or exogenous change. Computer software can be used in such a process. – Spatially disaggregate models can aggregate monetary values defined at the level of a certain

spatial unit. This can support, for instance, a cost-benefit evaluation exercise at the total system level.

– The output of model and valuation studies can be compared. For instance, when studying a sce-nario for wetland transformation one can model the consequences in multiple dimensions (physical, ecological and costs/benefits), and aggregate these via a multi-criteria evaluation pro-cedure, with weights being set by a decision maker or a representative panel of stakeholders.

Al-ternatively, one can ask respondents to provide value estimates, such as a willingness to pay for not experiencing the change. If such information is available for multiple management sce-narios then rankings based on either approach can be compared.

Last but not least, economists need to be aware of the limitations of any proposed economic valua-tion exercise. Despite all research efforts in an integrated, multidisciplinary analysis, modelling and valuation, it should be recognized that not all biodiversity value types can be made explicit and not all explicit biodiversity value types can be measured in monetary terms.

A valuation study is a partial study characterized by strict temporal and spatial boundary. As Gowdy recently said ‘… although values of environmental services may be used to justify

biodiversity protection measures, it must be stressed that value constitutes a small portion of the to-tal biodiversity value…’. In other words, monetary estimates of biodiversity should at best be in-terpreted as conservative estimates and thus regarded in terms of lower bounds. Clearly, more valu-ation studies need to be pursued to improve the informvalu-ation available to decision makers about the nature, magnitude and value on the impacts of human activities on the overall level of biodiversity.

IT

Economic growth and the environment in a liberal world

S.M. de Bruyn

Senior consultant at CE Environmental Consultancy, Delft Telephone number: +31-15-2150126

Email address: bruyn@ce.nl Introduction

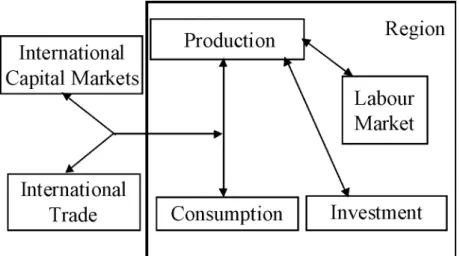

The aim of research on Industrial Transformation is, according to the Science Plan, “to understand complex society-environment interactions, identify driving forces for change, and explore develop-ment trajectories that have a significantly smaller burden on the environdevelop-ment.” One particular re-search area of interest concerns the relations between energy and material use, the associated waste products, technological change and economic performance. Can economic growth be sustainably delinked from its environmental impacts, and if so, what are the best strategies to achieve such a delinking?

Research into these areas has been undertaken at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam. This chapter describes this research, with which I have been involved with several others for the last eight years; it also indicates the new research that is currently being carried out at CE-Delft to identify possible options for a sustained delinking in a world characterized by globalization and liberalization. Does economic growth benefit the environment – or: do pigs drive cars?

Nobody has ever seriously investigated the question whether pigs drive cars. Yet, the number of pigs and the number of cars are highly correlated in, for example, the Netherlands. However, such a correlation does not allow for the conclusion that the demand for cars is driven by the growing number of pigs.

In the early 1990s, many authors found a correlation between environmental pressure and income. It was discovered that there are inverted U-shaped trends in the relationship between certain types of pollution (environmental pressure) and income (GDP). This phenomenon was labelled the ‘environmental Kuznets curve’ (EKC) and several authors have suggested that the EKC implies that economic growth benefits the environment. Such benefits could be realized due to positive in-come elasticities for cleaner consumer products, more tax inin-come for the government to finance environmental policies and the stimulation of technological development by economic growth. As a result, the trajectory of environmental pressure in relation to income per capita follows a bell-shaped trajectory, as given in Figure 1.

However, a detailed review of the empirical studies revealed that, effectively, only an inverted U-shaped correlation between some forms of pollution and income had been proved. Explanations were then forced upon this correlation ex-post. The research I undertook was aimed at unravelling the explanations for the decrease in some emissions, materials and energy in developed economies, and at examining whether economic growth could be identified as the main reason for this down-turn. In other words, it examined whether the relationship between income and pollution was dif-ferent from that between pigs and cars.

By applying several sophisticated econometrical tests to the data of environmental pressure and in-come in a number of developed economies, the research has revealed the following:

– The standard EKC results were obtained by assuming that the long-term relationship between income and pollution is stable over time and similar for various countries.

– Applying statistical tests to these two assumptions on the development of emissions of CO2, SO2 and NOx in four developed economies, showed that the relationship between emissions and income is not similar for these countries. Moreover, the inverted U-relationship between emissions and income is not stable over time. Hence the conclusion that economic growth ben-efits the environment is spurious and similar to the observation that pigs drive cars.

– The only stable relationship that could be established in this study implies that economic growth results in higher emissions. The observed decreases in pollution are realized by annual reductions that are exogenous to the estimated relationship between economic growth and change in emissions.

– An attempt was made to see whether such exogenous reductions could be endogenized by esti-mating a model between emissions, energy prices, income and economic growth. The estimates showed that energy prices seem to have a negligible influence on the reduction of emissions. The influence of economic growth, however, is highly significant and results in higher emis-sions. An economic growth of 1% results in an increase in emissions of 0.8 - 2.0%. This ‘push effect’ is counteracted by reductions in emissions, which depend on the level of income. Eco-nomic growth therefore has a long-term benefit by raising the level of incomes. However, this beneficial effect is very small and does not outweigh the initial increases in emissions due to economic growth. The conclusion is that emissions will decrease over time if the rate of eco-nomic growth is low.

– The observed reduction in emissions can be explained by the combined effects of technological changes (including end-of-pipe technologies) and changes in the structure of production. The study has found that the majority of emission reductions are the result of technological changes. These may have been enforced or encouraged by environmental policy. It has been shown that a higher level of income results in stricter environmental policies. Nevertheless, this effect is small and does not outweigh the burden of economic growth resulting from the higher con-sumption of materials and energy. Rates of economic growth above 2 to 2.5% will result in an increase in emissions of CO2 and NOx. For SO2 emissions higher growth rates are compatible with declining emissions. These results negate the EKC hypothesis.

– The technological changes in material and energy use follow a typical pattern. The relationship between throughput and income in the long run is N-shaped, similar to the inverted U-shaped curve but with a subsequent phase of rematerialization. The theory of ‘punctuated equilibria’, as applied in evolutionary economics, can provide an explanation for the N-shaped curve. In an equilibrium phase, economic growth results in a proportional increase in throughput but shocks – defined as drastic shifts in technological and organizational paradigms – may introduce a tem-porary phase of dematerialization. This will not continue for ever and the positive relationship between growth in incomes and throughput is likely to be restored, albeit at a lower level of throughput per unit of GDP. Statistically this implies that material use and emissions are not ‘co-integrated’ with income.

– The results of this study imply that the currently observed reductions in some types of emis-sions cannot be extrapolated directly into the future. The delinking of economic growth from environmental impacts should be considered as only temporary. Delinking as a permanent phe-nomenon has been rejected here on purely econometric grounds by testing for stability. A more intuitive explanation is that technological changes are important in the current phase of

delinking. With rising marginal costs of abatement, financial constraints will sooner or later be-come a bottleneck to further reductions. Emissions can then be expected to increase again at the same rate as economic growth, at least until a new breakthrough in technological and organiza-tional structures initiates another delinking phase.

A graphical representation of the main conclusions

The main conclusions of this research are that there is no stable inverted U-relationship between in-come and emissions, and that hence the conclusion that economic growth benefits the environment is spurious. The discovered relationship in this research implies that the relationship can be repre-sented by Figure 2.

This figure can also be found in the data. Figure 3 shows that the relationship between the change in SO2 emissions and economic growth is a positive one, despite the observed decreases in the emissions of SO2 in the 1980s. Similar figures can be made for other pollutants or for energy or material inputs, and for other times as well.

Opportunities for and threats to environmental policy in a liberal world

International organizations and national governments have embraced delinking as an environmen-tal policy goal. The results of this study indicate that the currently observed phase of delinking is temporary and will come to an end. This is not of much comfort to those who believed that our en-vironmental problems would solve themselves during the process of economic development. At the same time, the prospects for tightening environmental policy have been drastically narrowed over the last decades. As the usual command and control mechanisms oriented towards end-of-pipe solutions may not be appropriate to start a new stage of delinking, the question is what kind of policy instruments have to be formulated in order to take into account both the desire of societies to become sustainable and the world-wide development of globalization and liberalization. The aim of the project conducted at CE, ‘In Search of a Sustainable Liberal World’, is to study how a soci-ety that attaches great priority to sustainability could react to the virtually unavoidable trends re-garding liberalization, privatization and globalization. It deals with questions such as how trade and information flows contribute to enhancing the environment.

Ultimately, the search must lead to including and embedding environmental considerations in the economic decision-making process. This study has shown that the short-term negative environ-mental consequences of economic growth must be constantly compensated for by environenviron-mental policies. At present, a higher rate of economic growth does not automatically lead to stricter envi-ronmental policies. Hence, the economic system itself does not contain mechanisms that safeguard the environment automatically in the process of creating economic growth. This could probably be changed if it were possible to embed environmental aspects in the process of creating economic growth. One could think of internalizing all externalities as a first step. This would, in theory, im-ply that the price paid for environmental services rises when the economy grows and more environ-mental services are demanded. Linking the price of environenviron-mental services to demand (e.g. through a system of tradable permits) is an important first step in including environmental considerations in the process of economic growth. Alternative instruments can be made by using appropriate infor-mation technologies that provide consumers, traders and investors with environmental inforinfor-mation. Finally, one could consider indexing funds for environmental subsidies (e.g. encouragement of en-vironmentally benign technologies) to the rate of economic growth. By taking such measures, a higher economic growth rate would contain feedback mechanisms that could help safeguard the environment.

Details of the research in the first three sections of this chapter can be found in, expecially, S.M. de Bruyn, Economic Growth and the Environment: an empirical analysis, Kluwer Academic Publish-ers (it can be ordered via http://www.wkap.nl/book.htm/0-7923-6153-9). For more information on the last section of this chapter, please contact the author.

Selective bibliography

Bruyn, S.M. de, Opschoor J.B., 1997. ‘Developments in the throughput-income relationship: theo-retical and empirical observations’, Ecological Economics 20: 255-268.

Bruyn, S.M. de, 1997. Explaining the Environmental Kuznets Curve: Structural Change and International Agreements in Reducing Sulphur Emissions, Environment and Development Eco-nomics 2, pp. 485-503.

Bruyn, S.M. de, 1998. Dematerialisation and rematerialisation: two sides of the same coin. In: P. Vellinga, F. Berkhout and J. Gupta, Managing a Material World: Perspectives in Industrial Ecol-ogy. Kluwer Academic Publishers, p147-164.

Rothman, D.S., Bruyn, S.M. de, 1998. ‘Probing into the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis’, special editors of an edition of the journal of Ecological Economics, 25: see especially pp. 143-145 and 161-175.

Bruyn, S.M. de, Heintz, R.J., 1999. The Environmental Kuznets Curve Hypothesis. In: J.C.J.M. van den Bergh (ed.). Handbook of Environmental and Resource Economics. Edward Elgar, Chelten-ham, UK, and Northampton, MA, USA, Ch. 46.

Bruyn, S.M. de, 2000. Economic Growth and the Environment: an empirical analysis. Kluwer Aca-demic Publishers, 2000.

Anderberg, S., Olendrzynski, K., Prieler, S. and S.M. de Bruyn, 2000. Old sins: industrial metabo-lism, heavy metal pollution, and environmental transition in Central Europe. UN-Press, Tokyo. Bruyn, S.M. de, 2001. ‘Stages of Dematerialisation and Rematerialisation as a Challenge to Eco-Efficiency’ Okologisches Wirtshaften 3/1999, pp.15-17; an extended 15-page version of this arti-cle will appear as Ayres and Ayres: Handbook of Industrial Ecology, Edward Elgar.

From financial to sustainable profit

J.M. Cramer

Professor in environmental management, Erasmus University Rotterdam, and programmanager National Initiative for sustainable Development.

Telephone number: +31-26-3893844 E-mail address: jmcramer@xs4all.nl Introduction

Sustainable business practices are gradually becoming more and more widespread. This trend re-flects changing social attitudes towards the responsibilities of firms towards the societies in which they operate. More than before, firms are expected to account explicitly for all aspects of their per-formance, i.e. not just their financial results, but also their social and ecological performance. Openness and transparency are the new key words. This type of pressure is forcing an increasing number of firms to adopt ‘sustainable’ business practices, which means establishing a systematic link between their financial profitability and their ecological and social performance.

To enhance and support ‘sustainable business’ initiatives a big programme has been launched in the Netherlands under the title ‘From financial to sustainable profit’. This programme is being coordi-nated by the National Initiative for Sustainable Development (NIDO), established in 1999. The NIDO programme is closely related to the IHDP Science Project Industrial Transformation. NIDO is financed through special funds of the Dutch government. The foundation’s purpose is to structur-ally anchor sustainable initiatives in society. For this purpose, NIDO has introduced a process of cooperation between business, government, stakeholders (e.g. NGOs, financial institutions) and knowledge institutes. Within the framework of NIDO, several programmes have been set up, in-cluding the programme ‘From financial to sustainable profit’.

The starting point of the above-mentioned programme is a process-oriented approach in which no clear-cut results can be formulated in advance. The programme focuses on the interface between 26 participating companies and their stakeholders. Progress is made through learning in networks. The process is coordinated by change-agents that help to initiate the transformation to sustainable busi-ness. As soon as the initiative can be taken over by industry itself, NIDO will withdraw its active support. The programme, which started in May 2000, will run till December 2002. Within the pro-gramme two projects are being carried out: (1) measuring sustainable business and (2) marketing communication about sustainable business.

Research topics

Within the framework of the NIDO program ‘From financial to sustainable business’ the following four research topics are being elaborated together with the Dutch scientific community:

– Indicators for sustainable business

– The added value of sustainable business practices – The interaction between firms and external actors

Indicators for sustainable business

The first crucial step in the adoption of sustainable business practices is for firms to account for their performance in relation to all three Ps (People, Planet and Profit) (Elkington, 1997). And that’s no easy matter. Whilst international reporting standards for sustainable business are currently being developed, they are far from being finalized. So far, most progress has been made on the en-vironmental indicators. There are also all sorts of financial indicators which, unfortunately, do not give a full picture as it has not yet proved possible to factor into firms’ operating costs the adverse impact economic activities have on sustainable development. The least progress has been made on the social indicators. As a result, firms have no option but to use a patchwork of incomplete and in-compatible guidelines (Ranganathan, 1999).

It is vitally important that these guidelines be placed on a systematic footing and that maximum use be made of proven standards. Examples of the latter include the SA 8000 verification system for working conditions, the ISO 14001 environmental standard, and the AA1000 standard for im-proving the way in which firms report on the social and ethical aspects of their business. The OECD guidelines containing recommendations for the conduct of multinational enterprises (OECD, 2000), which were adopted in June 2000, represent a milestone on the road to creating an integrated package of measures. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI, 2000) goes one step further in the process of compiling detailed international guidelines. The GRI is the brainchild of CERES (Coalition of Environmentally Responsible Economies) acting in conjunction with UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme). The idea is that, by the year 2002, the GRI should have devel-oped a fully tested set of guidelines and will be in operation as a permanent, independent body. For the time being, opinions differ on the question whether a form of reporting based on financial, ecological and social indicators actually gives a truthful picture of corporate behaviour. After all, there may be a wide gap between the picture painted by indicators and the actual situation on the ground (Ghobadian et al., 1998; Schaefer and Harvey, 1998). Moreover, deciding which indicators should be used for the purpose of monitoring corporate behaviour as well as the relative weighting attached to each of these indicators remains a subjective matter. In spite of these reservations, it re-mains absolutely crucial that we try to devise an internationally standardized system of monitoring sustainable business practices. No form of effective benchmarking is possible without proper, inter-nationally accepted measuring and reporting systems (Krut and Munis, 1998).

The added value of sustainable business practices

The second research topic concerns the relationship between sustainable business practices and corporate profitability. This is an issue on which opinions are divided, not only among businesses themselves, but also among academics. Some commentators have claimed that there is a negative correlation, given that firms first need to incur costs that are not offset by any financial benefits. Not surprisingly, the application of the traditional measures of corporate performance (i.e. the RoS and the RoI), which are geared towards short-term profitability, suggests a negative correlation (Cordeiro and Sarkis, 1997). There is, however, another school of thought which states that sustain-able business is in fact beneficial to a firm’s financial performance (Bergakker et al., 1999). There are two key arguments in support of this theory. Firstly, the direct, explicit costs of doing sustain-able business are often low when compared with the substantial potential benefits (i.e. in terms of increased productivity and reduced third-party criticism of the firm in question). Secondly, sustain-able business practices may be seen as a form of superior management. This claim is supported by

the high correlation that is said to exist between a high score in Fortune’s good management index and a high score for sustainable business (as reflected by the league tables compiled by independ-ent sustainable business consultants such as Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini & Co, 1993).

As long as there is uncertainty as to the precise added value generated by sustainable business, firms will tend not to set their sights very high. For this reason, it is absolutely vital that research be conducted into the added value of sustainable business.

The interaction between firm and stakeholders

Given that sustainable business requires a systematic form of interaction between firms and their stakeholders, research in this particular field is becoming crucial. The principal concern of re-searchers today is to analyse the various roles and patterns of interaction among and within the various parties in a firm’s stakeholder network. Alongside the theory of a learning organization, the stakeholder perspective can also shed interesting light on these interactions. Gaining more insight into the influence (both potential and actual) exerted by stakeholders in the process of interaction with firms is of particular value in this respect. Firms are interested in this type of information as it helps them to decide which social needs are more urgent than others, whilst it tells the stakeholders themselves something about their position in the network, and hence their power.

One of the main distinctions made in the theories on stakeholders is that between primary and sec-ondary stakeholders (Clarkson, 1995). Secsec-ondary stakeholders are regarded as not being vital to a firm’s future, whereas primary stakeholders are. In practice, however, this distinction has been found to be too rough-and-ready. Consumer groups, for example, which are generally classified as secondary stakeholders, can easily jeopardize a firm’s continuity by organizing a boycott of its products. There is also a more refined way of ranking social needs in terms of their urgency, i.e., by classifying stakeholders on the basis of their distinguishing characteristics. Mitchell et al. (1997), for example, identified ‘the power and legitimacy represented by a group of stakeholders and the degree of urgency of their social needs’ as being the group’s most important features. Rowley (1997) takes a different perspective, based on the patterns of interaction between stakeholders. In fact, there is no reason why these two perspectives should be inconsistent with each other. What re-searchers have so far failed to agree on, however, is a list of characteristics or salient features that are most relevant in differentiating between stakeholders. This makes further research in this field of great relevance.

Integrating sustainable business practices into marketing communication strategies

The fourth and final research topic is concerned with the integration of sustainable business prac-tices into strategies for marketing communication. It is far from clear at present how firms can mar-ket and communicate their efforts in relation to the triple-P bottom line both accurately and trans-parently. At the same time, this aspect is of vital importance if they are to gain the confidence of consumers.

Research into integrating sustainable business practices into marketing communication strategies has not been given top priority to date. Should a firm seek to ensure that its efforts in relation to the triple-P bottom line are reflected in its positioning and corporate branding? And if so, how can one guarantee both transparency and reliability? As a result of a number of bad experiences in the past, firms are now very reluctant to promote a ‘socially responsible’ image of themselves. After all, any firm that tries openly to communicate its social and environmental virtues may find itself under

at-tack on a number of counts. For example, it may be accused of making unjustified claims

(Simintiras et al., 1994). Or it may be criticized for failing to have tackled certain social problems, or for certain effects it could not have foreseen. To give an example, the ‘trade not aid’ policy adopted by The Body Shop, which involved a pledge to assist Brazilian Indians by buying nuts only from them and not from any other source, was turned into an object of ridicule by sceptics. One of the accusations levelled at The Body Shop was that the amount of money involved was so small that it formed only a negligible part of the firm’s overall purchasing activities. Thus a com-pany which for many years had been regarded as the epitome of ethical trading found itself in trou-ble (Driessen and Verhallen, 1999).

Relatively little practical experience has been gained to date with integrated forms of marketing communication that take account of all three Ps (i.e. People, Planet and Profit). The predominant trend so far has been to market issues, such as the environment, and experiences with this have been mixed. Emphasizing the ecological benefits of a particular product in a niche market (for ex-ample, potatoes carrying the ‘Eco’ label) may be a good way of catching consumers’ attention. Generally speaking, however, environmental considerations are not the only factors consumers take into account when making purchasing decisions. Others, such as price, quality and ease of use, are often more important. Consumers are willing to buy environmentally-friendly products provided they score just as well as conventional products on these criteria (Ackerstein and Lemon, 1999). Peattie (1999) believes that conventional marketing strategies are just not up to the job of handling the issue of sustainable development. This is because, so he claims, such strategies are concerned solely with the current generation and not with future generations. Moreover, Peattie reckons that conventional marketing is preoccupied with the satisfaction of material needs and ignores social well-being. People have a huge range of disparate needs, some of which are in conflict with others. In other words, certain explicit material needs may be inconsistent with an inherent need for a healthy and active lifestyle, manageable stress levels or a high quality of future life. Marketing should be aimed at maximizing the quality of life, not at maximizing consumption in itself (Kotler, 1979). In other words, marketing should be geared not so much towards selling a particular product as towards the social values the product represents.

To an increasing degree, a firm’s reputation is determined by the values of the products and serv-ices it sells. We are witnessing a shift away from the ‘marketing of matter’ towards the ‘marketing of meaning’ (Mosmans, 1999). This implies that firms should no longer be listening to what people ask for in a material sense (i.e. products), but rather to their spiritual needs. Firms should be seek-ing to market brands that represent a particular philosophy, i.e. a body of views, attitudes, convic-tions, motivaconvic-tions, world views, etc. For example, consumers buying Max Havelaar products in Holland have the feeling that they are doing their bit to create a better world. Other consumers may be more attracted by the fierce anti-establishmentarianism of a brand such as Virgin.

In short, a number of recent marketing studies have already thrown up topics for future research that can play a role in embedding sustainable business practices in marketing communication strat-egies. What we are in fact talking about is a combination of qualitative marketing research aimed at identifying value priorities, changing paradigms and social trends on the one hand, and research into consumer preferences and lifestyles based on cultural and sociological trends on the other. The findings of this research should enable us to develop market propositions that are in line with the philosophy of sustainable business.

References

Ackerstein, D.S. and K.A. Lemon, Greening the Brand: Environmental Marketing Strategies and the American Consumer, in: M. Charter and M.J. Polonsky, Greener Marketing; A Global Per-spective on Greening Marketing Practice, Greenleaf Publishing, Sheffield, 1999, pp. 233-254. Bergakker, S. et al., Duurzaam beleggen: “Doing well by doing good”, Research Paper, Institute

for Research and Investment Services, Rabobank Nederland en Robeco Groep, Rotterdam, 4 January 1999.

Clarkson, M.B.E., A Stakeholder Framework for Analyzing and Evaluating Corporate Social Per-formance, Academy of Management Review, 20, No.1, 1995, pp. 92-117.

Cordeiro, J.J. and J. Sarkis, Environmental Proactivism and Firm Performance: Evidence from Se-curity Analyst Earnings Forecasts, Business Strategy and the Environment, 6, 1997, pp. 104-114. Driessen, P. and T. Verhallen, Groene Marketing; Marketing en Milieu Gaan Steeds Beter Samen,

in: P. Driessen (red.), Marketing en Milieu, Marketing Wijzer, Kluwer, Deventer, 1999, pp.11-33. Easterby-Smith, M. et al. (eds.), Organizational Learning and the Learning Organization;

Develop-ments in Theory and Practice, Sage, London, 1999.

Elkington, J., Cannibals with Forks; the Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business, Capstone,

Oxford, 1997.

Ghobadian, A. et al., Extending Linear Approaches to Mapping Corporate Environmental Behav-iour, Business Strategy and the Environment, 7, 1998, pp. 13-23.

Global Reporting Initiative, Sustainability Reporting Guidelines on Economic, Environmental and Social Performance, Global Reporting Initiative, Boston, 2000.

Kinder, P. D. et al. Investing for Good; Making Money while being Socially Responsible, Harper Business, New York, 1993.

Kotler, P., Axioms for Societal Marketing, in: G. Fisk et al. (eds.), Future Directions for Marketing, Marketing Science Institute, Boston, 1979, pp. 33-41.

Krut, R. and K. Munis, Sustainable Industrial Development: Benchmarking Environmental Policies and Reports, Greener Management International, 21, 1998, pp. 87-98.

Mitchell, R.K. et al., Toward a Theory of Stakeholder Identification and Salience: Defining the Principle of Who and What Really Counts, Academy of Management Review, 22, No.4, 1997, pp. 853-886.

Mosmans, A., Corporate Reputatie: Een Stand van Zaken, in: A. Mosmans (red.), Corporate Reputatie, Marketing Wijzer, Kluwer, Deventer, 1999, pp. 11-33.

OECD, The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, OECD, Paris, 2000.

Peattie, K., Rethinking Marketing: Shifting to a Greener Paradigm, in: M. Charter and M.J. Polonsky, Greener Marketing; A Global Perspective on Greening Marketing Practice, Greenleaf Publishing, Sheffield, 1999, pp. 57-70.

Ranganathan, J., Signs of Sustainability; Measuring Corporate Environmental and Social Perform-ance, in: M. Bennett and P. James, Sustainable Measures; Evaluation and Reporting of Environ-mental and Social Performance, Greenleaf Publishing, Sheffield, 1999, pp. 475-495.

Rowley, T.J., Moving Beyond Dyadic Ties: A Network Theory of Stakeholder Influences, Academy of Management Review, 22, No.4, 1997, pp. 887-910.

Schaefer, A. and B. Harvey, Stage models of Corporate ‘Greening’: A Critical Evaluation, Business Strategy and the Environment, 7, 1998, pp. 109-123.

Simintiras, A. C. et al., ‘Greening’ the Marketing Mix: A Review of the Literature and an Agenda for Future Research, in: M.J. Baker (ed.), Perspectives on Marketing Management, 4, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, 1994, pp. 1-25.

The transition to a low-emission energy supply system

A project of the International Centre for Integrative Studies (ICIS) and the Maastricht Economic Research Institute on Technology (MERIT) for the fourth National Environmental Policy Plan (NMP4) of the Netherlands

R. Kemp

Researcher at the Maastricht Economic Research institute on Innovation and Technology, Maastricht University

Telephone number: +31-43-3883864 E-mail address: r.kemp@merit.unimaas.nl

Project team: Jan Rotmans (project leader), René Kemp, Marjolein van Asselt, Frank Geels, Geert Verbong and Kirsten Molendijk

Introduction

Transitions are transformation processes in which society or a complex subsystem of society changes in a fundamental way over an extended period (more than one generation, i.e. 25 years or more). Transitions are interesting from a sustainability point of view because they constitute a pos-sible route to sustainability goals, besides the route of system optimization. Transitions offer the prospect of many environmental benefits, through the development of new systems that are inher-ently more environmentally benign. Transitions may produce sustainability benefits in the form of the preservation of natural capital, health protection and social well-being.

In this project, the researchers of ICIS and MERIT in collaboration with Frank Geels and Geert Verbong probed the concept of transition and developed the idea of transition management. This obviously is relevant within the context of IHDP’s Science Project on ‘Industrial’ Transformation. A transition refers to the process of change in which society or a complex sub-system of society gradually changes and moves towards a new equilibrium. The project resulted in a transition model and a method for managing transitions, i.e. transition management. The model was applied to the case of a transition to a low-emission energy supply system.

The transition model

The transition model, as a multilevel process, implies that changes only occur if the developments at one level follow on from the developments already taking place at the other levels. A transition is the result of the interaction between developments at the micro level of local practices and nov-elty creation within niches, the meso level of regimes and the macro level variables (the

sociotechnical & economic landscape). Within a transition there are containment factors and virtu-ous circles. Momentum is high during the take-off phase when niche developments, regime devel-opments and landscape develdevel-opments sustain each other, but gradually decreases during the stabilization phase.

The transition model (based on system theory and the multilevel model of sociotechnical change of Rip and Kemp) is viewed as a useful model for describing complex societal dynamics.

Managing transitions

During the project, the idea of transition management was worked out in collaboration with the NMP-4 team. Transition management consists of a deliberate attempt to bring about structural change in a stepwise manner. It tries to utilize existing dynamics and orient these dynamics to-wards transition goals chosen by society. The goals and policies to further the goals are constantly assessed and periodically adjusted in a development round. Through its focus on long-term ambi-tion and its attenambi-tion to dynamics, it aims to overcome the conflict between long-term ambiambi-tion and short-term concerns. This is done by evaluating existing and possible policy actions against two criteria: first, the immediate contribution to policy goals (for example in terms of kilotons of CO2 reduction and reduced vulnerability through climate change adaptation measures), and second, the contribution of the policies to the overall transition process. Learning, maintaining variety and in-stitutional change are thus important policy aims. Transition management breaks with the planning and implementation model and policies aimed at achieving particular outcomes. Transition man-agement is a form of process manman-agement against a set of goals set by society whose problem-solving capabilities are mobilized and translated into a transition programme, which is legitimized through the political process.

It should be noted that transition management does not exclude the use of control policies, such as the use of standards and emission trading, but helps to find additional instruments and arrange-ments that will contribute to the transition process. It offers an integrative framework for policy de-liberation and the choice of instruments and individual and collective action. It is believed that transition management will offer a basis for achieving more coherence and consistency in public policy and private action towards sustainability and will increase the chance that an actual transi-tion to more sustainable development modes in various functransi-tional domains will occur.

Transition management is based on a two-pronged strategy. It is aimed at both system improvement (improvement of an existing trajectory) and system innovation (representing a new trajectory of de-velopment). The role of government differs per transition phase. For example, in the

predevelopment stages there is a need for social experimentation and to create support for a transi-tion programme, the details of which should evolve with experience.

Transition management for energy

Ideas about transition management have been applied to energy supply. It has been found that the energy system based on the use of fossil fuels is not sustainable; however, the drivers for a transi-tion are weak. It is not at all clear who will provide guidance for realizing a transitransi-tion to an inno-vative, low-emission energy supply. Both the energy sector and experts point to the government as the lead actor. The government has taken action but in a rather myopic and partial way. In the field of renewable energy, the government has an extensive set of instruments, ranging from subsidies for clean energy technologies and long-range agreements about energy saving, to green certificates for renewable energy. However, the government’s policy has hardly been developed in other energy fields, such as the transport sector, the chemical industry and the heat supply. Government policies are also badly coordinated. Transition management could help to better coordinate public policy and legitimize policies. It could also mobilize problem-solving capacities in society. So, despite the limitations the national government has to face, it should play a key role in advancing the transition to a low-emission energy supply. The guiding role of the government should be twofold: it should be concerned with both the process and the contents (outcomes). An energy transition policy should contain the current climate policy, but should add something to it: a long-term vision, an impulse for system innovation, and greater coherence between the short-term and long-term policy and between micro and macro developments.

However, our analysis shows that it will not be easy to realize such a transition. Apart from the fact that the macro-scale factors should be favourable, it also requires a double role of the government. In process terms the government has to facilitate the transition process, whereas in terms of con-tents, it has to inspire the other social actors, by giving them direction. The guidance for the proc-ess of a transition will require a different form of participation, however, with new actors. Via a process of so-called niche participation, new players who are as yet insignificant but who may be-come important in the future can also bebe-come involved in the process. These actors may be brokers of renewable energy, communities for sustainable energy lifestyles or producers of new energy technologies. In organizing the transition process, the government could form an interdepartmental body or create an external entity of private and public decision makers responsible for transition management.

The research reported in this paper indicates that the transition concept can be used to structure complex societal dynamics, in such a way that it indicates levers for private and public action and legitimizes policy interventions for long-term change. Public support for a transition programme is very important. Without this the transition endeavour may come to a stop when results fail to mate-rialize quickly and setbacks are encountered. The programme should be broad and include reforms in education and science policy, as well as changes to technology policy, environmental policy and the pattern of interaction.

This study outlines the research agenda for transition management and a societal agenda for action. The final report and a project report on transitions (both in Dutch) can be downloaded from: http://www.icis.unimaas.nl/projects/nmp4/ and http://meritbbs.unimaas.nl/rkemp/

The economics of H

2O

P. Nijkamp

Professor in economic geography and regional economics, Free University Amsterdam Telephone number: +31-20-4446091

E-mail address: pnijkamp@econ.vu.nl J.M. Dalhuisen

Research assistant at the department of regional economics, Free University Amsterdam Introduction

One of the needs selected for the cities focus of the IHDP Science Plan on Industrial Transforma-tion is that for water. Water seems to be abundantly available, but the complex linkage with the car-bon cycle will bring changing precipitation patterns as a result of increased atmospheric concentra-tions of greenhouse gasses. The changing precipitation patterns, sewage, agricultural runoff and in-dustrial operations affect the water supply and have an increased impact on the hydrological cycle. The result of all this is a scarcity of water, not only in terms of quantity but also in terms of a cer-tain quality, which decreases the number of functions of water.

Water, because of its scarcity, has become subject to the normal economic market rules of supply and demand for scarce goods. Nevertheless, in most European countries, this scarcity is not re-flected in the price of water. There are even situations where water is considered a free good, simi-lar to air some decades ago. As can be expected, this often results in the over-consumption of wa-ter, which in economic terms results in inconceivably high inefficiency in its supply and use water. An illustrative example of these market failures is the fact that in Europe, losses due to leakage from the drinking water network amount to 10 – 75%.

The situation nowadays is changing; there is a real scarcity of water and a considerable number of issues concerning the supply of and demand for water have come to the fore. Cities like Seville and Athens are struggling to meet the demand for clean water, and Istanbul, with the current population growth and the current available water sources, will likely not be able to meet the needs of its in-habitants in ten years from now.

The World Water Forum, which recently was held in The Hague, greatly increased the interest in water issues. In many counties, including the Netherlands, the debate used to concentrate on the privatization of drinking water and the possible taxes on water use (Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal, 1999). However, these debates lacked a well-structured economic analysis of water man-agement and related decisions.

This chapter will focus on the various aspects of the economics of water. First, a general analysis will be made of water as a ‘normal’ economic good with different usage functions. Although many countries like the Netherlands certainly have to cope with water scarcity (in both a qualitative and a quantitative respect), in them the situation is not as threatening as it is, for example, for those living in the dessert. This is why this chapter will take a look at the demand and supply of water from an economic perspective. Also a comparison will be made between water as a specific good and a number of other ‘normal’ economic goods. Water, from an economic point of view, can be

consid-ered as a normal – and thus expensive – scarce good. Therefore, it is necessary to focus on the price of water as a key issue in policy-making. At the end of the chapter, a number of conclusions will be presented.

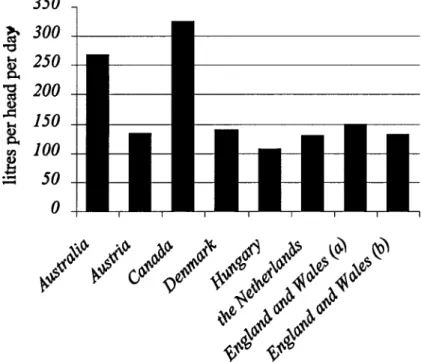

Demand for water

The drinking-water demand is rather complex and varies considerably from country to country. Figure 1 gives an impression of the water use per capita in a number of countries. A great number of studies on water have appeared in the economic literature. These studies can roughly be catego-rized as (a) those focused on the elasticity of water demand and (b) those focused on water demand forecasting. The rather remarkable outcomes of these studies were the rather low price elasticities of water demand. Despite the warnings about water shortages, the water consumer does not react to price changes. This often goes hand in hand with the political-economic statement that water is an essential good, and, thus, that the price should not be high. Also consumers are often of the opinion that the share of expenses of water in the household budget should not be too high. Because of the existence of public monopolies, it seems impossible to set a real market price. The pricing of water is determined by institutions, based on either a small symbolic fee or on full costs. However, the price is hardly ever based on the balance of supply and demand.

During the World Water Forum there was a plea for full cost pricing, although it appeared to be dif-ficult to fit this into the decision-making process. Nevertheless, it is important that water manage-ment be led by sound economic principles. Some examples might illustrate this. Cities in develop-ing countries (especially the slums) do not have a drinkdevelop-ing-water pipeline system because the costs