Cosmopolitanism in the European

Commission's speeches: the refugee crisis as

a turning point?

A conceptual content analysis

Academic dissertation Word count: 17.779

Pieter-Jan Herman

Student number: 01811587Supervisor(s): Prof. Dr. Hendrik Vos

Submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of EU-studies

Deze pagina is niet beschikbaar omdat ze persoonsgegevens bevat.

Universiteitsbibliotheek Gent, 2021.

This page is not available because it contains personal information.

Ghent University, Library, 2021.

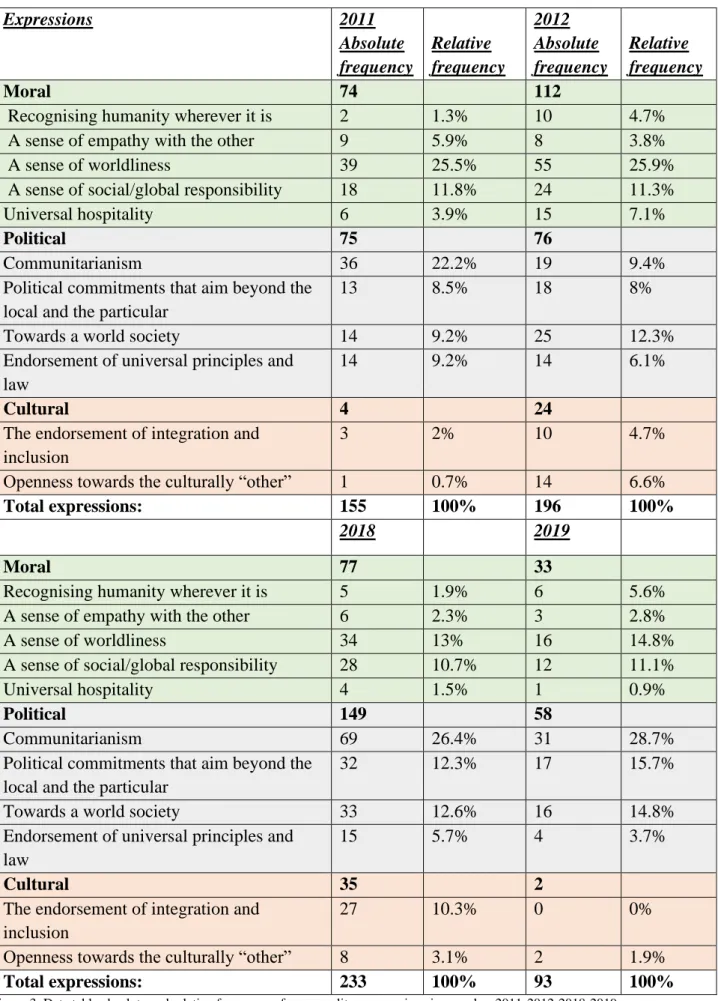

I. Abstract

This paper examines cosmopolitanism in the European Commission’s speeches in the context of the refugee crisis. In the theoretical framework it explores and deconstructs the term cosmopolitanism and describes the current academic debate on the subject. Next, it compares a total of 39 speeches from 2011-2012 and 2018-2019 using a conceptual content analysis to gain insight in the global stance of the Commission and potential changes regarding cosmopolitanism. The results show that the composition of cosmopolitan aspects changed from emphasising a morally based Commission towards a political and cultural cosmopolitan stance. Specifically the concepts of communitarianism, integration and inclusion, and concrete political action are much more apparent in the 2018-2019 speeches. Additionally, there’s less concepts of universal hospitality present post-crisis. The conclusion is that the Commission wants to emphasise cooperation, solidarity and concrete cosmopolitan action to tackle the problems of the refugee crisis.

Deze paper onderzoekt kosmopolitisme in speeches van de Europese Commissie in de context van de vluchtelingencrisis. We verkennen en operationaliseren de term kosmopolitisme en beschrijven het huidige academische debat in een literatuurstudie. Vervolgens vergelijken we 39 speeches uit 2011-2012 en 2018-2019 aan de hand van een conceptuele inhoudelijke analyse om inzicht te krijgen in de globale positie van de Commissie en mogelijke veranderingen van positie betreffend kosmopolitisme. We stellen vast dat de samenstelling van kosmopolitische elementen veranderde van een nadruk op morele kosmopolitische elementen naar politieke en culturele kosmopolitische elementen. Vooral concepten van communitarisme, integratie en inclusie, en concrete politieke actie zijn veel meer aanwezig in speeches van 2018-2019. Daarnaast zijn er ook minder concepten van universele gastvrijheid aanwezig in speeches na de crisis. We concluderen dat de Commissie in speeches van 2018-2019 meer nadruk wil leggen op samenwerking, solidariteit en concrete kosmopolitische actie om de problemen van de vluchtelingencrisis aan te pakken.

In a world torn asunder by multiple forms of strife, nothing seems more timely than to be reminded of our shared humanity and of the universal aspirations present in religious teachings and prominent philosophical traditions. (Dallmayr, 2003, p. 428)

II. Preface

Exploring numbers, databanks and graphs might leave us with better arguments and theory for understanding the world. From a personal perspective, a distance to the horrific realities of refugees on the ground remains. When writing, this tends to be forgotten. It’s only when reading names and stories that awareness arises. It’s then that we are reminded of what these innocent-looking numbers hide. The opening quote in this paper reminded me of that.

Dallmayr’s words jog the memory of our cosmopolitan commonalities. He refers to our search for philosophical truth, an attempt to remind us of the relativity and impact of human constructs in all dimensions of life. As truth comes in many forms, sometimes simultaneously, one truth does not always exclude the other. Science has an undeniable role in safeguarding these interactions. It sheds light. It’s a tool to build and rebuild constructs.

I would like to thank professor Hendrik Vos for his guidance through this interesting process. I would also like to thank my family for giving me the chance to keep studying in the last couple of year and for giving me the opportunity to explore my interests and passions. I would like to thank my mother, who’s invested a lot of her time in proofreading and motivating me throughout the process of writing this thesis.

III. Table of contents

I. Abstract ... 3

II. Preface... 5

III. Table of contents ... 6

IV. Introduction ... 7

A. Topic, objectives and study design ... 7

V. Theoretical Framework & literature ... 11

B. EU’s discourse... 11

C. Commission addressing migrants... 17

D. Theoretical framework ... 20 Taxomony cosmopolitanism ... 21 Indicators... 23 E. Research question ... 26 VI. Methodology ... 28 F. Data collection ... 30 G. Conceptualisation ... 32 H. Interpretation ... 37 General method ... 37 Concrete examples ... 38 Interpretation of ambiguities ... 39 VII. Results ... 41 VIII. Conclusion ... 44

IX. Limitations and further remarks... 47

X. References ... 49

IV. Introduction

A. Topic, objectives and study design

In the course of recent years, migration in the context of the refugee crisis has been the subject of heavy discussions on all kinds of platforms, institutions and public forums at every level of European societies. The debate is ranges from local pubs and governments to the highest political institutions in existence such as the United Nations and the European Union. Migration affects many of us and has become a key element in this last decade’s politics. Many political parties have taken a clear stance on the subject.

In 2012 and 2013, EU countries processed 373.550 and 464.510 asylum applications from non-EU citizens (Eurostat, 2019). In 2015, that number soared to a staggering 1.393.920 asylum applications. In 2018 and 2019, those numbers fell as Eurostat estimated 656.995 applications in 2018. Roberts, Murphy, and McKee (2016, p. 1) state that the number of refugees crossing borders to Europe is only a fraction of the total amount of registered refugees in the world who have been displaced. For example, approximately 2.1 million refugees were/are sheltered in Turkey, and 1.1 million are sheltered in the Lebanon. Nevertheless, these numbers illustrate a vast increase and influx of migrants to Europe in a short period of time in 2015.

Moreover, the stream of migrants to Europe had the highest death toll in any region in the world. Approximately 3771 deaths in the Mediterranean of a total of 4054 deaths in 2015 (International Organization for Migration, 2019) were due to drowning. Whereas the total amount of asylum applications decreased to 656.995 applications from non-EU citizens, the total number of deaths barely dropped in 2018 with 2299 deaths on a total of 4727 migrant deaths (International Organization for Migration, 2019). Roberts et al., (2016) state that the EU’s response to the crisis was lamentable and insufficient. On top of that, the suffering of most of these people didn’t end when they arrived in Europe where many had to endure bad living conditions as they lacked basic health care and decent shelter. These facts in themselves raise many questions.

In 2015 the term “refugee crisis” was first introduced to define the then ongoing situation. There’s some debate amongst scholars as to whether the EU refugee crisis should be approached and referred to as an actual “crisis”. Prem Kumar Rajaram, professor at the Department of Sociology and Social

Anthropology at the Hungarian Central European University writes that the crisis is fabricated and framed to enable more vertical and state-centred intervention by policy makers, which leads to the depoliticization of their situation:

By trying to place people outside of the political norm, the state legitimizes three types of action all centred on depoliticizing—a humanitarian approach centred on saving souls, a securitized approach where harm is legitimized (witness the deployment of antiterrorism forces at Hungary’s borders against unarmed people), and a technical or administrative approach to refugee status adjudication that prioritizes speedy, cost-effective, and deterring procedures while restricting the right to legal recourse including the right of appeal. (K. Rajaram, 2015)

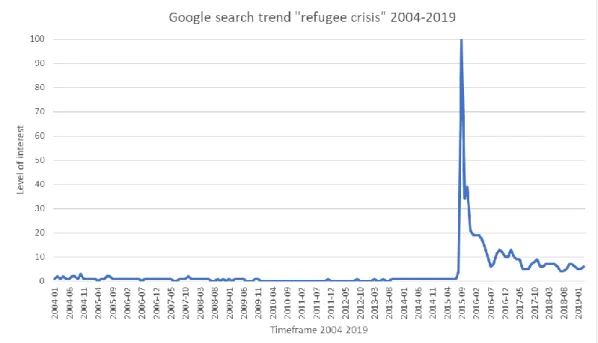

Figure 1. Data (Google Trends, n.d.)

What is certain is that nationalist and populist movements are gaining strength all over Europe. Radical right parties have had the biggest electoral successes since the Second World War (Mudde, 2016). Postelnicescu observes the return of politics of fear (Postelnicescu, 2017; Wodak & Krzyżanowski, 2017) quoting “in the face of fear, people want to feel safe; hence a leader who can promise security and protection is gathering the popular support” (Postelnicescu, 2016, p. 204). We find examples in the rise of Marine Le Pen in France, Orbán in Hungary and many more as extensively discussed by others before me.

Sociologist Anthony Smith (2003) points out that at the origin of the rise of nationalism is a natural response to the identity crisis that exists. Modernity has made certain traditions collapse. Along with the economic crisis (Ntampoudi, 2016) and now the refugee crisis, European countries endure problems of national identity. It’s in this vein that identity politics have become so important to right-winged parties, which partly explains their success. The form of modernity I speak of is called globalization. Our current globalized world is more interconnected than ever and has been the foundation for the biggest changes of the past decades. It can be seen as a reason for these new forms of nationalism to arise.

At the basis, academics define two poles, two extremes with nationalism on one side and cosmopolitanism on the other (Audi, 2009; Conversi, 2001; De Greiff, 2002). Conversi describes cosmopolitanism as a ”[. . .]common rationality which makes mankind predestined to share a common fate” (Conversi, 2001, p. 34). Cosmopolitanism entails a disposition of openness (Naous, 2006; Beck, 2006; Szerszynski & Urry, 2002; Skrbis & Woodward, 2004; Delanty, 2006; Nugent & Vincent, 2007; Lindell, 2014). Contrary to nationalism, cosmopolitanism goes beyond nation borders, it refers to world citizenship and the vision of a global democracy. Where nationalism is based on intranational traditions values and beliefs, cosmopolitanism advocates post-identity politics of overlapping interests and heterogenous publics to challenge that (Vertovec & Cohen, 2003). Some scholars like Martha Nussbaum refer to Stoic ideals of cosmopolitanism to be valuable ideals in ethic debates of today (Konstantakos, 2015). Although criticised, Naseem and Hyslop-Margison state that Nussbaum’s version cosmopolitanism “. . .its potential to reduce the growing global discord we currently confront“ (Ayaz Naseem & Hyslop-margison, 2006, p. 51). To date, little primary research has been done to examine this dichotomy at EU-level.

Lavanex (2001) states in “the Europeanization of Refugee Policies: Normative challenges and institutional legacies” that the debate on European integration and refugee policies has mainly been centred around the vertical aspect of state sovereignty and supranational governance and less on the substantive dimension (Lavanex, 2001). That substantive dimension is crucial, she says, in refugee politics because it cannot be justified by material interests. Because of that I’d like to dig into the substantive dimension of EU migration politics, more precisely the cosmopolitan aspect.

Given the stated facts, I’ve asked myself if a similar process could have been going on at the EU level. The European Union has always been a strong advocate of democratic values and human rights. Yet the refugee crisis has unveiled some of its weaknesses. The EU struggled to tackle these problems in

an effective way with bitter consequences such as the indirect death of thousands of migrants in the Mediterranean and the failure of the Dublin agreement (Postelnicescu, 2016). I am particularly interested in the global stance of the EU on this problem. Has that changed? How has the Commission expressed itself in the last decades? There were several roads to take from there. I could go and interview Commissioners, I could look into specific data, etc. Nevertheless I decided that speeches might be a lot easier to access and examine with the available methods.

I’ve concluded this research topic: To what extent did cosmopolitan values in the European Commission speeches change between 2011-2012 and 2018-2019 within the context of the “refugee crisis”?

As 2015 was a critical turning point, I’ve deliberately limited the scope of my thesis to these time frames. On the one hand it’s limited the amount of work to a realistically attainable goal, on the other hand this has enabled the comparison of a pre and post refugee crisis situation. I decided to analyse speeches as they are easily accessible on the Commission’s website. Speeches are well thought-out pieces of text aimed at big audiences. These speeches have specific goals and purposes. Therefore, examining them is really valuable.

The structure of this paper is straightforward. I will commence by defining and operationalising literature where I will explain the current discourse in the EU, cosmopolitanism and refugees. From the literature work I will conclude two more hypotheses (which you can find in chapter E. Research question), then I will explain my research method in more detail (data collection, method, conceptualisation) and finally I will lay down results and formulate conclusions.

V. Theoretical Framework & literature

B. EU’s discourse

In this chapter, I will shortly lay down the existing discourse concerning cosmopolitanism in the context of the refugee crisis in the European Union. Additionally, this chapter serves as the academic grounds from which I formulate my hypotheses (see chapter E. Research question).

Angela Merkel’s famous “Wir schaffen das” in 2015 illustrated the cosmopolitan stance of many European leaders. Europe was considered a “safe haven” and a “beacon of hope” (Naous, 2016) or in the words of Martin Fayulu “champions of values and democracy” (VRT, 2019). Naous claims that the EU has a cosmopolitan ideological position. Suvarierol & Düzgit (2011) follow that line of reasoning. They build an argument on the institutional motto, it being “unity in diversity”, the embracement of cultural diversity.

Less cosmopolitan?

Nevertheless Naous states that the EU might be obliged to act less cosmopolitan in the future. He writes that the EU has had a priority to keep “the Union together and keeping the internal market and free movement of citizens and for this reason fit aims at strengthening its external borders while implementing other security measures particularly for getting a better grip on irregular migration” (Naous, 2016, p. 37). Perkowski (2016, p. 333) writes that “responses to the recent ‘humanitarian crises’ have included a strengthening of Frontex operations, a greater focus on deportations, a new EU naval mission aimed at targeting ‘smugglers’, and the so-called ‘hotspot’ approach, in which security and asylum agencies co-operate in identifying and registering those newly arrived at entry points to the EU.” This concurs with the former statement. Adding to the argument, Chouliaraki and colleagues note “In the midst of the “crisis”, which saw European nations extending acts of solidarity to newcomers but “[. . .]eventually shutting their borders[. . .]” (Chouliaraki et al., 2017, p. 3).

The situation remains complex. On the one hand, the EU and its Member States are obligated under international law and EU Treaties to offer protection to asylum-seekers. But on the other hand, there are obligations under the same EU Treaties to guarantee the security and social cohesion of Member States’ societies. While the EU is helping Member States to deal with the

refugee crisis, diverging national interests have, until now, prevented further common decisions in this field. (European Parliament, n.d.-a)

Politicians that support the cosmopolitan outlook are seemingly under more and more pressure: “the arrival of increasing numbers of asylum seekers on the doorsteps of the First World has led to fierce political debate about asylum policies, often fuelled by parties of the far right” (J. Hatton & G Williamson, 2004, p. 3). A computer-assisted content analysis done by Greussing & Boomgaarden (2017) reveals that Austrian tabloids and quality media established narratives of “security threat” and “economisation” to be most prominent, humanitarian frames and background information on the refugees’ situation are paid attention to on a lesser extent. These frames coincide with an inward-looking EU and thus non-cosmopolitan behaviour.

The cosmopolitan stance has been heavily criticised. “capitulating to populist anti-immigration politicians, European Union leaders are pulling up the drawbridge to migrants fleeing war, famine and poverty in Africa and the Middle East” (Taylor, 2018). Journalists refer to “fortress Europe”. These right-winged, often nationalist or populist parties may have a lot of influence on the EU’s global stance concerning migrants. Wodak & Krzyżanowski (2017, pp. 1-2) talk of “[…]increased hostility and at best various reservations towards the incoming asylum seekers[…]” and “[…]the continuous exclusionary rhetoric of othering, fuelled by the resurgence of right-wing populist and nationalistic as well as nativist agendas in both Europe and beyond surely contributed to these debates”. In the Routledge Handbook on Politics of Migration in Europe, Susana Martínez Guillem and Ivana Cvetkovíc (2018) even state that this kind of explicit anti-immigration discourse has ceased to be the exclusive domain of far right political activists. They explain how centrist and even leftist political narratives have started to use similar anti-immigration arguments. Additionally they state that other elite discourse producers (academic publications, media,…) offer insight in the normalisation of the anti-immigrant stance. This normalisation of anti-immigrant stance reaches not only into the political fields but it also seems to affect other layers of society.

Skrbis and Woodward (2013, p. 30) touch the aspects of tension between cosmopolitanism and nationalism in their book “Cosmopolitanism, uses of the idea”. They state that “The question of how to reconcile cosmopolitan agenda and ambition with the reality of modern national citizenship is not a question of abstract principles. Instead, it is about the key political questions of our era: how can we reconcile broad cosmopolitan principles with existing governance regimes and economic structures; how can we combine cosmopolitan hope with reality which often militates against hopefulness?”. They

use the EU as the perfect example of that tension. The refugee crisis of 2015 has put a lot of pressure on the workings of the EU, which requires a cosmopolitan perspective of its member states, and on cosmopolitan principles in general. They say that “The current dilemmas of the EU go to the very core mantra throughout this book: the EU, not unlike cosmopolitanism itself, is a project, not an endpoint.” Skrbis and Woodward (2013) thus argue that the EU in itself is an ongoing cosmopolitan project which could naturally have its ups and downs.

Stevenson (2011, p. 114) states that “Europe, I would argue, is actually a site of ambivalence: it is the space of racism, fundamentalism and nationalism while also offering hope through ideas of human rights and democracy”. Furthermore, we can conclude that he in essence concurs with the view of the EU as a cosmopolitan project. Yet, as already stated, the heavily intertwined interests of both nationalist and supranational actors have slowed down the process towards a possible cosmopolitan ideal. Tupala (2019, p. 2) points out that “The EU has been actively developing its common and comprehensive migration policy since 1999 in the spirit of freedom, security and justice, and these principles still prevail. However, the refugee crisis of 2014/2015 acts as a watershed that led the EU to swiftly refocus its migration agenda, this time with a more robust approach on border management and stopping irregular migration” of which the last two clash directly with the cosmopolitan ideal. Kapartziani and Papathanasiou (2016) write about a “paralysed” EU since the refugee crisis. They not only state that the EU now fails to present the all-encompassing cosmopolitan ideal, they go further and talk of a significant breach. It has become an aggregate of blame games which seriously undermine the legitimacy of the European institutions. The EU that was envisaged many years ago by Schuman and Monet was very different. Its model of social plurality has come under immense pressure.

Further exploration of the boundaries of cosmopolitanism in EU institutions is explored by Suvarierol & Düzgit (2011). They present a strong case with the accession talks with Turkey. They examined the discourse of the Commission’s officials with regard to their own identity and compared this to their discourses on the Turkish elite. The borders of cosmopolitan Europe currently seem to stop at the border of Turkey. Their analysis is based on stereotypical depictions by Commissioners of Turkey and its society. Commissioners mention the “pride”, “arrogance” and “unreliability” of the Turkish elite. “A ‘nationalist’ nature of the interlocutors is essentialized and generalized through the construction of ‘a way of thinking’” (Suvarierol & Düzgit, 2011, p. 164).

Security discourse

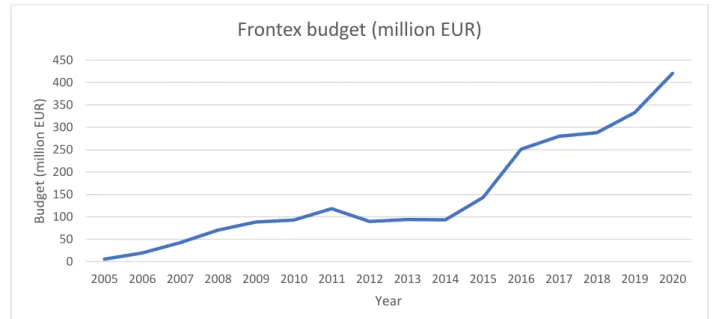

Security discourse coincides with the apparent changes in discourse. Before the 9/11 attacks and after the Second World War, the EU had become more open than ever. It abolished border security and created a so called customs union. However, the attacks on the World Trade Centre steered the dominant liberal EU discourse on borders in the opposite direction. This idea of open borders was suddenly replaced by a need for closed or more “secured” borders (Newman, 2006). It’s within this context that Frontex was brought into existence in 2004 and it’s within the context of the refugee crisis that the EU has kept strengthening Frontex’s capacities. Frontex’s main tasks are guaranteeing the security of the external EU borders through their own resources and coordination between the member states. It serves as a tool to answer the politics of fear. It is also a response to the growing security discourse. The graph below illustrates the sudden rise in budget for the EU’s main border guard agency.

Figure 2: Frontex budget (million EUR) data (Frontex, z.d.)

As securitisation in general gained importance, it got more and more associated with migration discourse/policy. The migration-security nexus takes into account the connection in policy, literature and discourse between the two fields. There’s a general consensus between authors on the gradual securitisation of EU immigration policies (Cvetkovic & Guillem, 2018, Huysmans 2009; Geddes, 2008; Van Munster, 2009). The question remains if this reflects in the EU’s discourse. Securitisation of policy would mean a.o., a further strengthening of borders preventing mobility; this directly conflicts with the cosmopolitan ideal of free movement and connectedness. Nevertheless there are several sides here. Some arguments support the idea that securitisation of discourse suggests that

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400 450 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Bu d ge t (m ill ion E U R) Year

migrants are seen as “threats”, which is considered the basis for securitisation of migration after 9/11 (Karyotis, 2007; Skleparis, 2011). There’s another side that perceives securitisation of migration from a moral cosmopolitan perspective as a way of preserving and enabling “human security” as in e.g. the saving of lives at sea (Huysmans, 2009) which is an interesting perspective. However most authors conclude that the securitisation and externalisation of migration policy has contributed to more deaths at sea and the strengthening of borders, which primarily opposes cosmopolitan values.

Perkowski (2016) observes that the recent movement of people (cfr. refugee crisis) has led to a general trend in discourse on migration specifically focussing on: mobilisation of security, humanitarianism and human rights. Perkowski observes that these three subjects rather than being opposed to one another share some commonalities. She states the figure of the citizen functions as an implicit “us” whereas that citizen is put against a certain “other”. That “other” being the “illegals”, “terrorists” in the context of security. Humanitarianism relies on the pitying of “victims” and human rights discourse relies on the construction of “victims, saviours and perpetrators” (Perkowski, 2016, p.332). Her point is unequivocally that the EU, and in this context Frontex, has had a more security centred approach towards migration.

From this, we retain that a serious friction between securitisation and cosmopolitanism exists and that it has heavily influenced the EU’s discourse, even more so after the crisis.

Dehumanisation

Bruneau, Kteily and Lausten (2018) conclude that flagrant dehumanisation of Muslim refugees is common among Europeans and that it is associated with anti-refugee behaviour. They emphasise the particular relevance to the refugee crisis. This implies an opposite point of view to the cosmopolitan connectedness to the “other”.

Furthermore, Inglis (2015, p. 737) observes, “the unprecedented refugee ‘problem’ stemming from mass migration from Syria and other locations has seriously undermined cooperation and solidarity between member-state governments, to the point that cross-border mobility in the Schengen area is being ever more restricted – a development mostly unthinkable just a few years ago”. Inglis observes how the typical Kantian cosmopolitan dream has come under severe strain. The basic principles of the EU as a post-Westphalian peace project or as a human rights centred “soft power” impose a far too sharp historical break between “then” and “now” (Fine, 2003; Inglis, 2015). The EU has not become

a pure “post-Westphalian” cosmopolitan project. He states that this post-national political entity has become another power-wielding political body through the use of its own supposedly universal cosmopolitan values. The EU uses this identity as a means to find sympathy for its project. Arguably, the Commission and other EU institutions have also used this to create “a pan-European culture”. However Inglis is sceptical as any identity exists only when juxtaposed against another. How does the cosmopolitan idea of “human dignity, the suffering of all regardless of nationality” within Europe persist within a context of dehumanisation? Inglis (2015) tackles these matters interestingly in his research paper “The clash of cosmopolitanisms”.

A divided European discourse

Neal (2009) and Ravn (2015) mention a gap in EU discourse. A gap that exists when leaders of member states address citizens on topics of European migration-and border policy. The communication between European institutions is often done within these circles or with specialists and advisors. Ravn refers to a “small public dimension”.

Furthermore, Favell & Hansen (2002) claim that on a national level policy makers try to avoid humanitarian NGO’s to please anti-immigration voters. These authors claim that there is a general problem with managing migration because there would be a system of multilevel governance. Member states don't want to relinquish their sovereignty (Lavanex, 2001).

Adding to that, Krastev (2017) even writes about a new “East-West Divide” in the European Union as both the East and the West have a completely different view on solidarity in the context of migration. Krastev writes that eastern Europe has a historical hostility towards migrants. Eastern Europeans remain unmoved. Central and eastern Europe (Krastev, 2017, p. 293) are “aware of the advantages but also of the dark sides of multiculturalism”. Krastev refers back to the late nineteenth century where western Europe shaped harmonious ethnic landscapes and where eastern and central European states were shaped within the disintegration of empires and processes of ethnic cleansing. These countries are now ethnically homogenous and turning back to a time of ethnic diversity would be back to a time of trouble.

In several ways cosmopolitanism is presented as an answer to some of these questions. The introduction already mentioned how Nussbaum’s version of cosmopolitanism could potentially reduce the “global discord” (Ayaz Naseem & Hyslop-margison, 2006, p. 51. It’s one of the leading names in

cosmopolitanism studies Ulrich Beck, who suggests a complete reformulation of the concept cosmopolitanism away from the “the cosmos” and “the globe” in such a way that it fits a new vision for the EU. It would no longer concern harmonisation and eliminating national differences, but on the contrary embracing them. He advocates a cosmopolitan Europe from below by the member states and governments in view of the growing apathy towards the European project. From a policy-making point of view, he explains the obvious drawbacks of EU’s majority voting principle in that it shows no concern for “otherness”. As majorities remain “majorities”, it creates conflict and it is a danger for cosmopolitan Europe. He advocates the use of consensus voting and European referenda within a “bottom-up” communication and participation concept (Beck & Grande, 2007; Pichler, 2008). While Beck has not further explored the impact in the field of discourse, he does attempt to open up new pathways or new ways of thinking for EU institutions to find solutions.

Conclusion

We conclude that most authors claim that an apparent change in the cosmopolitan discourse and policy of the European Union towards a more inward looking EU has taken place. This clashes with the cosmopolitan ideals and the EU as a cosmopolitan project. The purpose of this research is to get an insight as to how this reflects in the European Commission’s speeches specifically.

C. Commission addressing migrants

In this chapter, I will attempt to deliver some insight into how the European Commission addresses the different types of migrants. In addition, I will shed light on how the European Union has been handling the refugee crisis and discussions that go along with it.

Naous (2016) has depicted 4 common ways the EU addresses migrants in its communication to the outside world, whether that be its website, press releases, speeches or academic literature about the EU treating migration viz, refugees (European Commission, 2015), economic migrants, internal migrants and irregular migrants (European Commission, 2015).

A refugee is someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war or violence. A refugee has a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group. Most likely, they

cannot return home or are afraid to do so. War and ethnic, tribal and religious violence are leading causes of refugees fleeing their countries. (UNHCR, n.d.)

The European Union has addressed problems with concern to refugees regularly in speeches. The theme is very apparent as said earlier due to the enormous influx of migrants in 2015. Refugees have several different rights that are documented in for instance the Geneva convention and different UN resolutions. An example of that would be the “non-refoulement principle”, which was introduced in the Geneva convention. It prevents migrants being sent back to a third country when they are at risk of being persecuted or other serious harm. The non-refoulement principle is the cornerstone within asylum and migration law.

The terms migrant/refugee and crisis have often been referred to together. As said in the introduction, “refugee crisis” has been more occurrent than ever since 2015. "Migration crisis assumes multiple forms and is deployed for different goals: it can define and draw attention to a political issue; it can signal a new but incomplete film genre; while, in the last case, migration can be indicted as the root cause of a longstanding crisis, also in order to disavow the relevance of systemic inequalities such as institutional racism in the way housing priorities are set” (Gulliver, 2017; Dines, Montagna, & Vacchelli, 2018). This quote illustrates the difference between a migration crisis and a refugee crisis. The former refers to a broader concept that stretches beyond the 2015 refugee crisis. In this research I, will stick specifically to the context of the refugee crisis while also incorporating the way the EU addresses other types of migrants and leaving out any other societal discussions that might go along with migrants and a migrant crisis. In other words, I will focus on the overlap of the refugee crisis and other types of migrants that are often addressed together with refugees in speeches within the context of the refugee crisis.

The crisis has led to an atmosphere of tension and controversy fuelled by public opinion in the Member States. The EU was forced to take control of the chaotic situation and adopted its position in the form of the European Agenda on Migration. This document meant “[. . .]a political signpost of the EU’s activities in the migration area”, it “defined the EU priorities in this field, both concerning activities requiring ad hoc reaction and long-term plans. In another two years, the agenda was specified by means of various executive orders and developed in the shape of legislative proposals introducing modifications to the broadly understood European Union policy on migration.” (Trojanowska-Strzęboszewska, 2018, p. 171)

Another important element of discussion in EU migration politics is the Schengenzone. The Schengenzone is an area within Europe that consists of 26 countries that have signed the Schengen agreement. By signing this document, they agreed to gradually abolish border checks and allow for free movement of residents. 22 of those 26 countries are EU countries. This agreement has come under a lot of pressure since the refugee crisis. Pressure is on southern countries like Italy, Greece and Spain since that is where most refugees arrive. As soon as these refugees reach Europe, they move further inward. When refugees arrive in border countries like Italy they can apply for asylum in any of the EU countries in theory. In accordance with the Dublin agreement these applicants are to be spread among other EU countries. Precisely this is a big problem, most Eastern countries are unwilling to take any refugees and Western European countries aren’t taking many either. This is especially problematic because of the dehumanising conditions these refugees have to live in. The EU has been considered and thought itself to be very vocal about its democratic values and respect for human rights and both seem to clash with its apparent changing attitude towards migration.

The Dublin System covers issues of border control, asylum and irregular migration and is linked to the Schengen agreement. As said it manages the equal distribution of asylum seekers among EU countries. It’s also the EU’s main policy mechanism that assigns responsibility for asylum seekers to the member states through the principle of “country of first entry”. This system is heavily criticised as it creates a heavy burden for southern countries where most refugees enter the EU. Reforms for the Dublin system (Dublin IV) remain stuck in the Council of the EU’s decision making process as the member states cannot find any common ground. The Dublin system has flaws and the current proposals for reform do not bring any fundamental changes.

The Turkey-EU refugee deal has halted a big portion of the refugee stream. In an attempt to bring down the staggering amount of migrants entering Europe, the EU and Turkey agreed upon a deal to prevent migrants from coming to the EU by keeping them in Turkey. The EU provides 12.4 billion euros for the funding of migration projects outside of the EU, the bulk of that money goes to Turkey.. It also provides 15 billion for funding in the EU.

Furthermore, EU legislation does not yet allow for regulated arrival of asylum-seekers. The flows of migrants coming to Europe are mostly a mix of asylum-seekers and irregular migrants, which create difficulties of not being able to stop irregular migrants at EU borders. Current measures don’t reach much further than the Common European Asylum System (CEAS). In 2013, the EU attempted to harmonise asylum rules with the completion of the CEAS. The system was implemented to help

prevent intra-EU movement of migrants. Yet Member States are still responsible for processing asylum applications and the process seems too difficult to organise at EU-level. The EU has a system of “codecision and qualified majority voting” in the domain of immigration policy. Member States find it difficult to give up control over this domain and are able to block any decisions made (European Parliament, n.d.-b).

D. Theoretical framework

In this chapter, I will further decipher the term cosmopolitanism and lay down the basis for my research. There’s a lot of literature on this topic with diverse emphases. The concept is considered essentially contested, as often in social sciences, and thus I will limit myself to one specific interpretation.

Cosmopolitan comes from the Greek words Kosmo and politês, which mean world and state respectively (Kleingeld & Brown, 2013). The concept was first described by Aristotle, Plato and Socrates and brought back to life in the mid-90s by Martha Nussbaum’s essay on patriotism and cosmopolitanism (Skrbis, Kendall, & Woodward, 2004). Research into this concept has developed quite recently. “During this recent window, which has lasted a decade or more, researchers are working out – including clarifying and simplifying, but also deepening and complicating – the concept’s meanings, empirically and theoretically.” (Skrbis & Woodward, 2013, p. 14). This paper will prove meaningful in such a way that it contributes to the development of these theoretical structures.

There’s a wide variety of definitions and explanations. “Most contemporary commentators concur that cosmopolitanism – as a subjective outlook, attitude or practice – is associated with a conscious openness to the world and to cultural differences” (Skrbis, Kendall, & Woodward, 2004, p. 117). The term describes a global sense of community, a sense of transnational togetherness. Leading authors on the subject, Kleingeld and Brown describe it as “[. . .]is the idea that all human beings, regardless of their political affiliation, are (or can and should be) citizens in a single community” (Kleingeld & Brown, 2013, para. 1). The concept doesn’t lend itself to precise empirical work, it has a sense of vagueness and ambiguity. That is why I will devote a significant part to deconstructing the term in the chapter “taxomony cosmopolitanism”.

Taxomony cosmopolitanism

In their book “Cosmopolitanism: uses of the idea”, Woodward and Skrbis say the following:

The term cosmopolitanism is increasingly commonly used, yet it continues to escape easy definition. Philosophers and sociologists alike find it notoriously difficult not only to define the term but also to agree on just who befits the label “cosmopolitan”. We understand and are sympathetic to the definitional complexities around cosmopolitanism, but as sociologists we cannot accept that an agreement on the attributes of “cosmopolitanism” is so elusive that engagement becomes pointless. We suggest that there are four basic dimensions of cosmopolitanism that can easily be accepted: the cultural, political, ethical and methodological. (Skrbis & Woodward, 2013, p. 2)

Moreover, Delanty (2006) illustrates three broad forms of cosmopolitanism, viz. moral cosmopolitanism, political cosmopolitanism and cultural cosmopolitanism. This format is the one I will be using for my research and is supported by most scholars.

Moral cosmopolitanism is probably the most profoundly discussed form in academic literature and is first described in Stoic moral philosophy. It has a strong notion of universality; Nussbaum calls it moral universalism in her often discussed paper (Nussbaum & Cohen, 2002). It illustrates the strong connection of oneself to a universal community. Delanty speaks of another interpretation in “. . .liberal communitarian approaches to multiculturalism as in the idea of universal recognition of the moral integrity of all people” (Delanty, 2006, p. 28). This form of cosmopolitanism is “the worth of reason in each and every human being” (Vertovec & Cohen, 2003, p. 427). In this form, the cosmopolitan unconditionally recognises the moral connection to others, whether that other is your neighbour or someone on the other side of the world, no matter the context of that person.

Political cosmopolitanism relates to citizenship and democracy, and is derived from the works of Kant or more recently Stuart Hall and others. Delanty talks of a “transnational democracy beyond the nation-state” (Delanty, 2006, p. 29). In this notion of cosmopolitanism, globalisation plays an important part. Cosmopolitans here are the people that feel they belong to a bigger picture, beyond nation borders. These people feel a belonging to societies post globalisation and the structures, law and rights that these shared communities have. There are no more fixed boundaries. “It is in reconciling the universalistic rights of the individual with the need to protect minorities that the cosmopolitan moment

is most evident. In this context cosmopolitan citizenship is understood in terms of a cultural shift in collective identities to include the recognition of others.” (Delanty, 2006, p. 29).

Furthermore:

Cosmopolitan commitment is also a political commitment, which encourages us to appreciate and recognize difference, embed our politics in universal principles and commit ourselves to the dethronement of one’s unique cultural identity. This dimension extends into institutional and global domains when cosmopolitan political commitments aim beyond the local and particular and morph into institutionally committed cosmopolitan principles. At this global level cosmopolitanism refers to an ambition or project of supra-national state building, including regimes of global governance, and legal-institutional frameworks for regulating events and processes, which reach beyond any one nation.” (Skrbis & Woodward, 2013, p. 2)

The key to cultural cosmopolitanism is the notion of “societal pluralization”, as Delanty puts it. In current theory, we speak of heterogenous cultures with advanced networks, mobilities and even modernity itself. Delanty (2006) refers to the work of Manuel Castells’s networks as open flexible structures in his ground-breaking book “Sociology beyond societies”. Castells writes about societies being networks rather than fixed territories. Urry describes the “post-societal” era in sociology as a period in which we must forget the social rigidities and focus more on imaginative and virtual movements of objects, images, messages, ideas, etc (Urry, 2000a). It’s in this globalised context that cultures are redefined and shaped, fixed societies become redundant. Despite giving interesting new insights into cultural cosmopolitanism Delanty remains fairly modest about cultural cosmopolitanism because the web of complex networks, without some notion of an alternative (world) society, has little normative application in cosmopolitan practice.

Ulf Hannerz describes cultural cosmopolitanism as “[. . .]an openness toward divergent cultural experiences, a search for contrasts rather than uniformity, but not simply as a matter of appreciation. There was also the matter of competence: at one level a general readiness to make one’s way into other cultures; at another level, a cultivated skill in manoeuvring more or less expertly with one or more cultures besides one’s own” (Nugent & Vincent, 2007, p. 70). In cultural cosmopolitanism we recognise the “other”, we accept other cultures and other local ways of “being”.

Skrbis & Woodward (2013) talk of a fourth dimension being “methodological cosmopolitanism” referring to social analysis in academic work. Methodological cosmopolitanism connects to social science in such a way that it binds all levels of globalism to the local. It hopes to better harmonise social science to the workings of a global world. It is not really applicable to this primary and practical research. It would be more useful in secondary research.

Moreover, Kleingeld & Brown (2013) depict a similar classification with the same three categories and a forth “economic cosmopolitanism”. They say that “it is the view that one ought to cultivate a single global economic market with free trade and minimal political involvement” (Kleingeld & Brown, 2013, para. 1). But Kleingeld & Brown state that only few philosophers defend this category. It is mostly advocated by economists and politicians in richer countries (she refers to Friedman and Hayek). This will also not be of real interest to my research.

Indicators

It is important to stress the fact that I will limit myself to cosmopolitanism in the context of the refugee crisis and how European Commissioners address refugees. Several authors have attempted to define tangible indicators to enable specific content analysis on cosmopolitanism. Others have listed frameworks in their respective researches; I have used the work of Abraham Naous, Skrbis and Woodward, and Johan Lindell. Most of these authors suggest a three-dimensional format of cosmopolitanism as described earlier.

“In order to see cosmopolitanism as a useful analytical tool we suggested that it needs to be seen as a set of practices and dispositions, grounded in social structures” (Skrbis & Woodward, 2005, p. 3.

Starting with the framework of Johan Lindell (2014, p. 5-6):

Moral cosmopolitanism

- “the principle of cosmopolitan empathy” (Beck, 2006, p. 7) - “universal hospitality” (Kant, 1795)

- “learning to recognise humanity wherever it is” (Nussbaum, 1994) - “feeling global responsibility” (Nussbaum, 1997)

- “feeling pity and acting on images of distant suffering” (Chouliaraki 2006, 2013)

Political Cosmopolitanism

- “the capacity to create a shared normative culture” (Delanty, 2009, p. 87)

- “an awareness of global risks and the global ‘community of fate’” (Beck, 2006, p. 7) - “the impossibility of living in a world society without borders” (ibid)

- “awareness of the interconnectedness of different political communities (Held, 2010, p. 110) - “a recognition of 'collective fortunes' which require collective solutions” (ibid)

- “trust in supranational institutions” (Norris & Inglehart, 2009; Mau, 2010) - “willingness to expand political community (Pichler, 2009)

- “low degree of economic, cultural and institutional protectionism” (Roudometof, 2005, p. 126) - Desire to make the world more 'cosmopolitan', e.g., campaigning for human rights, to protect

against global poverty (Smith, 2007, p. 46;Van Hooft, 2007)

Cultural cosmopolitanism

- “the capacity of relativization of one’s own culture” (Delanty, 2009, p. 86; Gilroy, 2004, p. 75; Lindell, 2014, p. 6).

- “the capacity to create for a mutual evaluation of cultures of identities” (ibid).

- “the consumption of many places and environments” (Szerszynski & Urry, 2002; Lindell, 2014, p. 6).

- “a willingness to take risks by virtue of encountering the 'other'” (ibid).

- “curiosity about many places, peoples and cultures. An openness to and appreciation of other people and cultures (ibid).

- The ability to 'map' one's own society and its culture in terms of a historical geographical knowledge (ibid).

- “a curiosity of the culturally different” (Beck, 2006, p. 7; Lindell, 2014, p. 6)

- “all local ethnic religious and cosmopolitan cultures and traditions interpenetrate (ibid) - “transcultural 'code-switching' (Kendall, Woodward, & Skrbis, 2009; Lindell, 2014, p. 6)

- “inclusive valuing of the culturally other” (Kendall, Woodward, & Skrbis, 2009, p. 112-113; Lindell, 2014, p. 6)

- “celebration of difference” (Held, 2010 p. 112; Lindell, 2014, p. 6)

- “willingness to engage with the Other” (Norris & Inglehart, 2009; Hannerz, 1990; Appiah, 2006; Lindell, 2014, p. 6)

- “Not attached to local context of living, state or country and low degree of affiliation with local culture” (Roudometof, 2005, p. 26; Lindell, 2014, p. 6)

- Ironic distance to locality, nation, culture (Smith, 2007; Turner, 2002; Lindell, 2014, p. 6)

- The sensation of belonging to 'Greater society' or 'the world' (Schueth & O'Loughlin 2008; Pichler 2011; Lindell, 2014, p. 6)

Woodward & Skrbis (2013, p. 2-3) attribute the following indicators to define the different dimensions:

Moral cosmopolitanism:

- A sense of worldliness - Universal hospitality - Communitarianism

Political cosmopolitanism:

- Encouraging to appreciate and recognise difference - Embedding politics in universal principles

- Dethronement of one’s unique cultural identity

- political commitments that aim beyond the local and the particular - Regulating events beyond any one nation

Cultural cosmopolitanism:

- A disposition of openness

Naous (2016, p. 20) analysed Woodward and Skrbis’ framework and further improved it. He concluded the following framework:

Moral cosmopolitanism:

- Sense of worldliness - Sense of hospitality

- Sense of social responsibility - Sense of empathy with the “other”

Political cosmopolitanism

- Commitments aim beyond the local and particular - Moral political decisions on humanity

- Regulating events beyond any one nation - Communitarianism

Cultural cosmopolitanism

- Disposition of openness - Integration and inclusion

Adjectivisation

Normative appropriations of a concept are not necessarily a bad thing. We know all too well that good ideas often thrive when going through an imaginative reframing of what has always been thought of as impossible or unchangeable. Yet, this unfortunately also serves as an excuse for many a cosmopolitan theorist to use the concept as if it were an elastic cord which can be stretched in every possible direction. There’s been an explosion of literature on cosmopolitanism over the past 20 or so years and the discussion has been vibrant and exhilarating as well as frustratingly self-indulging. The idea has been subjected to an avalanche of unprecedented ‘adjectivisation’ which has added spin to the idea of cosmopolitanism, but which has not necessarily advanced our understanding of it. (Skrbis & Woodward, 2013, p. 4)

Skrbis and Woodward proclaim an “avalanche of adjectivisation” in the field of cosmopolitan studies. In other words cosmopolitanism has developed a wider range of meanings and a plenitude of nouns and adjectives (Pichler, 2008; Delanty, 2006; Szerszynski & Urry, 2002). When specifically determining the indicators, I have attempted to summarise certain terms of the same stems to cover as many different notions of those terms as possible.

E. Research question

As indicated in the introduction, this research is carried out within the context of the refugee crisis. It seeks to understand its influence on the European Commission’s communication. In addition it aims to deliver insights in the substantive dimension of EU refugee politics (Lavanex, 2001).

A lot has been written by both ends of the political poles ranging from the Commission either being too “weak” or too “intrusive” when it comes to refugee politics. The securitisation of migration and

externalisation may have had some influence on the downward trend of asylum applications but at the same time a record number of lives are lost at sea. The ridiculity of this must not be further explained. The European Union was envisaged (Kapartziani and Papathanasiou, 2016) as an essentially cosmopolitan project (Skrbis & Woodward, 2013; Suvarierol & Düzgit, 2011). But what still stands?

I formulated the following research question: To what extent did cosmopolitan values in the European Commission speeches change between 2011-2012 and 2018-2019 within the context of the “refugee crisis”?

I’ve conducted exploratory research into cosmopolitanism in academic literature. I determined that most authors expect the global cosmopolitan stance to have changed after the refugee crisis.

I also formulated two hypotheses on the basis of that research. More in-depth explanation can be found in the chapter “EU’s discourse”.

The following hypothesis:

- The European Commission’s speeches will overall be less cosmopolitan

Research suggested a less cosmopolitan EU (Cvetkovic & Guillem, 2018; Taylor, 2018; Tupala, 2019; Wodak & Krzyżanowski, 2017; Greussing & Boomgaarden, 2017; J. Hatton & G Williamson, 2004) and the Commission specifically (Naous, 2016; Kapartziani & Papathanasiou, 2016; Karyotis, 2007; Skleparis, 2011; Perkowski, 2016)

- The European Commission’s speeches will show less hospitality towards migrants

Chouliaraki refers to “shutting down borders” (J. Hatton & G Williamson, 2004; Chouliaraki et al., 2017; Wodak & Krzyżanowski, 2017). Besides academic sources, similar statements were made in qualitative media outlets e.g., Taylor (Politico) talks of “pulling up a

VI. Methodology

This study uses a conceptual content analysis approach to analyse speeches. Due to reasons I clarified in the introduction, I decided that I wanted to examine the European Commission’s speeches on their “degree” of cosmopolitanism. It is an empirically-driven (Joffe, 2012) method used by researchers to examine complex concepts. This qualitative method is very flexible in use (Jabareen, 2009). Content analysis allows one to reveal “evidence and patterns that are difficult to notice through casual observations” (Christie, 2007, p. 176). Conceptual content analysis, like other content analysis, is used to determine the presence of concepts within texts.

In other words, to be able to measure or quantify cosmopolitanism through conceptual content analysis we must deconstruct the term and define it as specifically as we can. This way we make sure all different aspects of the concept are covered. Mapping cosmopolitanism this way will help us to better understand it and therefore to have a more reliable theoretical foundation. Subsequently the different aspects are defined in concrete indicators. These indicators will help the coder identify the occurrence of the aspects of cosmopolitanism in the speeches (Sabharwal, Levine, & D’Agostino, 2016; Naous, 2016). Hence deconstructing cosmopolitanism into different indicators allows us to quantify their occurrences. This enables us to compare in time and measure certain changes that offer us interesting research material. In the next subchapter, I will clarify why I’ve chose the specific timeframes 2011-2012 and 2018-2019.

Furthermore, with regard to interpretation it must be noted that there’s a difference in the implicit and explicit meanings of certain parts of a text. In this research, I will look for the implicit meaning, which in rare cases can differ from its explicit meaning. This method is vulnerable to subjectivity as it leaves room for much interpretation. Because of that I will leave as much transparency as possible. In the chapter “interpretation”, I will lay down some more information on how I interpreted certain elements of speeches.

It is important to note that conceptualisation is a constant process of change and revaluation.

This way we attempt to reach a certain quality of conduct which is self-evident to a trustworthy research. From that perspective this method draws from Grounded Theory in many ways as it lends partly its inductive method and it also uses “sensitizing concepts” (Jabareen, 2009), which means that the framework changed during the data analysis. Besides, in normal conceptual analysis, the coding

process uses three phases of coding: open, axial and selective coding. The open coding process brings themes to the surface from inside the data (or “indicators”). Nevertheless I did not need to start from a tabula rasa in this paper. Much of the groundwork was done by other authors mentioned in the literature chapter. This meant that I could pass on quickly to the axial coding phase and the assessment of indicators by either merging or splitting them or even by adding new ones based on common sense or further empirical evidence. The third coding phase consisted of scanning previous codes and looking for further demarcation and precision (Neuman, 2007). In other words, the aggregated coding scheme (or framework) that is constructed through literature research was in turn influenced by qualitative data analysis. This resulted in the final coding scheme that can be found in chapter “conceptualisation”.

After finalising the coding scheme’s central structure I further adapted the explanation of the theoretical basis so that it would be more transparent. This would guarantee reliability of the explanation of the coding scheme (Joffe, 2012). I conducted an inter-coder reliability test using Cohen’s kappa method. A family member was asked to analyse 2019 speeches until we reached a kappa score of 0.77. The score varied between 0.5 and eventually 0.77 after explaining the coding scheme better and adjusting the explanation. Kappa values ought reach at least 0.6 and are preferably 0.7 or higher (Sabharwal, Levine, & D’Agostino, 2016; Munoz & Bangdiwala, 1997).

This way the coding was optimised for consistent application of the same codes to the same excerpts. In an ideal situation, a complete analysis of all speeches is made by a second coder, for obvious reasons.

Finally, after laying down the right indicators and revaluating them in practice, I gathered all data and examined their density and composition.

F. Data collection

The European Commission is the executive part of the EU. They initiate new legislation, they make sure Member States comply to the rules and handle day-to-day business. Additionally they lay out the strategic path the Union will take. Hence they are a trustworthy and representative entity to use speeches from. I choose to examine speeches since speeches are well-thought out pieces of texts. Speeches are strong communicative tools for Commissioners to inform, enthuse, encourage, persuade their publics. That public consists of both civilians and government officials.

The statistics shown in the introduction, combined with Eurobarometer studies and practical considerations, found strong arguments for the chosen timeframes. Qualitative speech analysis is time-consuming; for that practical reason analysing a full 10 years of speeches from 2010 to 2020 was not possible. I’ve limited myself to speeches from 1 January 2011 to 31 December 2012 and from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2019. I used the programme “Nvivo” to analyse the speeches. The purpose of this chosen timeframe was to get some insight in differences between a situation before the refugee crisis compared to the situation after. A two-year time frame allowed the gathering of enough speeches to have a representative number of samples to do any assessments. A total of 734 expressions were counted within the samples. Years 2014, 2015, 2016 were left out of the analysis as these were at the height of the refugee crisis. Year 2018 was the first year where asylum applications were somewhat stabilised at 600 000 (Eurostat, 2019). This is the year where the global political climate with concern to migration started to cool off a bit. The Eurobarometer analysis by the Foundation for European Progressive Studies illustrates this. There’s a big peak from 2014-2015 to 2016-2017 which shows that migration suddenly becomes the most important topic for EU citizens countries to face. The figure on the left shows the most important topics Austrian/EU citizens felt the country was facing in 2009-2018.

Figure 2. Reprinted from “European public opinion and migration: achieving common progressive narratives”, by Foundation for European Progressive Studies., 2019, p. 42.

I gathered speeches on the European Commission’s website through their search options and used their “advanced search” tool. I used keywords such as “SPEECH”, “2012” and “Migration”, “Migrants” or “Refugee”. I found 15 relevant speeches pre-crisis and 24 post-crisis. All pre-crisis speeches combined count 27169 words and 1232 sentences. The post-crisis speeches comprise a total of 23031 words and contain 1197 sentences. Both sample sizes contain approximately the same amount of sentences. I noticed the available speeches were more numerous and slightly shorter in 2018. On the other hand, 2019 yields the lowest amount of speeches; this illustrates the importance of having a slightly larger timeframe of two years compared to the analysis of just one year.

Data collection is a crucial part of this research because it plays an important role its reliability. I carefully filtered speeches by means of the following criteria:

Who wrote the speech?

- I choose to limit the scope of the research by only selecting speeches that were written by Commissioners.

In what year was the speech written?

- The speeches had to be written in 2011, 2012, 2018 or 2019. What is the subject of the speech?

- The speeches have to be exclusively focused on migration, whether labour migration, refugees or family reunification etc. I deliberately left out mixed speeches.

What form does the speech have?

- Furthermore the speeches had to be at least partially English. I did not include analysis on other languages. These parts are also left out in the word and sentence counts.

G. Conceptualisation

In the literature part I depicted several frameworks which I used as a basis to formulate the final framework, which consists of all different indicators that I’ve used for the research. We could argue that at the basis of the conceptualisation comes a general attitude of openness as described by other authors (Kendall et al., 2009; Skrbis & Woodward, 2011; Lindell, 2014). I attempted to find consistency throughout other author’s frameworks. Since “the matrix guiding the operationalisation of many indicators is not exhaustive” (Lindell, 2014, p. 5). In order to get a somewhat consistent framework I was required to merge some elements that are based on the same notions and to split up certain others. Any expression in the Commission’s speeches is recognised through the following indicators or the endorsement of any of these indicators.

Moral dimension Political dimension Cultural dimension

Recognising humanity wherever it is

Communitarianism The endorsement of integration and inclusion A sense of empathy with the

other

Political commitments that aim beyond the local and the particular

Openness towards the culturally “other”

A sense of worldliness Towards a world society A sense of social/global

responsibility

Endorsement of universal principles and law Universal hospitality

Starting in the moral dimension of cosmopolitanism, I ascertained a certain hierarchy of openness at the basis of the classification. In his framework, Johan Lindell refers to “learning to recognise humanity wherever it is” (Nussbaum, 1994) as part of an indicator for moral cosmopolitanism. This coincides with Naous’ indicator for political cosmopolitanism viz. Naous (2016, p. 21-22) writes “‘Moral political decisions on humanity’ include policies for increasing humanitarian aid where needed, working on voluntary humanitarian admission schemes, or any other decisions and resolutions that emphasise the importance of human safety, dignity and wellbeing.”. While I agree with this being an important indication of cosmopolitanism, I interpreted this to belong to the moral dimension like predetermined by Lindell. This is where Naous’ framework seems to be inconsistent as, following the same reasoning, he might also have added “political decisions on hospitality” in the political

dimension. Recognising humanity and acting on it politically are separate elements. When interpreting conceptions of cosmopolitanism in speeches, those speeches will often consist of both political action and recognition. The recognition part I interpret as moral cosmopolitanism; to me, the part of political action, belongs to the political dimension. In this domain I conclude, as Lindell and Nussbaum state, “recognising humanity wherever it is” as an important indicator for moral cosmopolitanism. In addition to this indicator Delanty recognises a capacity of “positive recognition of the other” in the cosmopolitan disposition. Urry (2000b) formulated this very much alike, as “a willingness to take risks by virtue of encountering the ‘other’”. All these elements belong to the idea of recognising humanity wherever it is. Acting on that “willingness” in concrete political action is covered in the political dimension. It must be said that Urry’s indicator refers to both a moral aspect, in the sense that the worth of the other person is valued as equal, and a cultural aspect which I’ll further explore in the cultural domain. The indicator “recognising humanity wherever it is” becomes very tangible when the worth of the other is recognised and affirmed.

Both Naous (2016) and Beck (2006) recognise a sense of empathy with the “other” as part of the wider cosmopolitan outlook. Chouliaraka defines this sense of empathy more specifically as a moral concern and emotion directed towards human suffering. Lindell sees Chouliaraka’s explanation as an indicator on itself but I will follow the more generally formulated argumentation given by Beck and Naous. Having a sense of empathy can bring about accompanying actions but those actions are no sine qua non. Empathy is shown in the ability of putting oneself in the shoes of the other. Other ways of empathy are shown in grief and compassion or hope towards refugees.

Woodward and Skrbis (2013), Naous (2016) talk of a sense of worldliness while Hansen (2009) writes of open-mindedness, both referring to a similar notion of moral cosmopolitanism we look for in the fourth indicator. Both terms refer to a relation of oneself to the outside world. A cosmopolitan person is worldly-wise and open-minded. This indicator emphasises being connected and open to different situations and events that happen in the world.

Having a sense of social responsibility (Naous, 2016) or global responsibility as Nussbaum (1994) puts it, is the fourth indicator for moral cosmopolitanism that will be used for this research. Since global responsibility covers a broader notion of responsibility that stretches beyond the human related form of social responsibility I will most likely find this type of responsibility in the EC’s speeches. Social responsibility is exerted when the European Commission expresses the importance of e.g.,