ADHD AT WORK

THE MEDIATING INFLUENCE OF SELF-ESTEEM AND EXECUTIVE

FUNCTION ON OCCUPATIONAL OUTCOME.

Word count: 21.326

Sara Claes

Student number: 01504503

1st Master Bedrijfspsychologie en Personeelsbeleid

Promotor: Prof. Dr. Peter Vlerick

Co-promotor: Prof. Dr. Roeljan Wiersema

A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master Personnel Management and Industrial Psychology (Dutch: Bedrijfspsychologie en

Personeelsbeleid)

2 Preface

For me, writing and finalizing this thesis during the final years of my Psychology studies - main subject Personnel Management and Industrial Psychology - was the icing on the cake. Now, my years as a Psychology student have come to an end, and I can only look back with great delight. During this time I have learned a bunch of psychological constructs and theories about employees and their wellbeing, about work and the organization as a whole, topped with a thick layer of statistics and data-analysis. Writing this master thesis, I was able to integrate everything I learned during my journey, and to use and further strengthen my critical thinking skills. Moreover, the topic of my thesis perfectly fits my personal mission, namely “making the workplace a better place”. However, the icing - and the cake - are not the result of my labor alone. First of all, I would like to thank my promotor Prof. Dr. Peter Vlerick and co-promotor Prof. Dr. Roeljan Wiersema for their advice, support, and their rapid and clear responses to all my questions.

Second, I would like to thank all participants without whose contribution I wouldn’t have been able to finish this thesis.

Third, I would like to thank my partner for his endless support during my studies and especially during my thesis, from the very start, to propose this topic, until the very last letter.

Lastly, I would like to thank both my brother and my father, two other important men in my life, who always had my back, through every high and every low during these challenging years.

3 Preamble concerning COVID-19

Data collection and analysis of the master thesis were substantially affected by COVID-19. We aimed for a larger sample size, however since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of responses substantially dropped, even though data were collected by means of an online survey. Number of responses probably dropped since all events organized by the specialized support groups we were working with, were canceled. We decided to perform analysis with the data at hand. Part of the data-analysis might have suffered some power related issues due to the reduced sample size. This preamble was drawn up in consultation with both the student and the promoter and approved by both.

Data-verzameling en -analyse van de masterproef werden aanzienlijk beïnvloed door COVID-19. Een grotere steekproef werd nagestreefd, maar sinds het begin van de COVID-19-pandemie daalde het aantal reacties aanzienlijk, ook al werden de data verzameld door middel van een online enquête. Het aantal reacties is waarschijnlijk gedaald omdat alle evenementen die waren georganiseerd door de gespecialiseerde steungroepen waarmee we samenwerkten, werden geannuleerd. We hebben besloten om de analyses uit te voeren met de beschikbare gegevens. Een deel van de data-analyse heeft mogelijk te maken gehad met power-gerelateerde problemen vanwege de kleinere steekproefomvang. Deze preambule is in overleg met de student en de promotor opgesteld en door beiden goedgekeurd.

4 Abstract

ADHD has been shown to negatively impact occupational functioning. However, within the ADHD literature job satisfaction and work-related social competence are overlooked and underresearched. With the purpose of addressing this gap, this master thesis aims to gain insight in the potential relationships between ADHD and job satisfaction, work-related social competence and life satisfaction among employed ADHD adults. Alongside the effect of the condition itself, we also investigated the hypothesized mediating role of (organizational-based) self-esteem and executive functioning. Data were anonymously collected via an online survey (N=129).

In line with our hypotheses we found significantly negative correlations between ADHD and job satisfaction, work-related social competence and life satisfaction. Organizational-based self-esteem solely fully mediated the relation between ADHD symptomatology and social competence at work. Executive functioning, as assessed with a questionnaire, only fully mediated the relation between ADHD symptomatology and job satisfaction. No full mediating effects were found in the relation between ADHD and life satisfaction. Finally, results showed that high ADHD adults can better distinguish self-reported ADHD symptoms and executive function compared the adults with less ADHD symptomatology. Based on these results, practical implications are provided. In addition, we discuss the study strengths and limitations of and formulate some suggestions for future research.

5

ADHD heeft een negatieve invloed op het beroepsmatig functioneren. Binnen de ADHD-literatuur worden werktevredenheid en sociale competentie in de werkcontext echter over het hoofd gezien en wordt er onvoldoende onderzoek naar gedaan. Om deze kloof te dichten, beoogt deze masterproef inzicht te verwerven in de potentiële relaties tussen ADHD en werktevredenheid, sociale competentie op het werk en levenstevredenheid bij werkende volwassenen met ADHD. Naast het effect van de aandoening zelf, hebben we ook de veronderstelde mediërende rol van (organisatie-gebaseerd) zelfvertrouwen en executief functioneren onderzocht. Gegevens zijn anoniem verzameld via een online enquête (N = 129).

In lijn met onze hypothesen vonden we significant negatieve correlaties tussen ADHD en werktevredenheid, sociale competentie op het werk en tevredenheid met het leven. Organisatie-gebaseerd zelfvertrouwen medieerde slechts volledig de relatie tussen ADHD-symptomatologie en sociale competentie op het werk. Executief functioneren, zoals gemeten behulp van een vragenlijst, medieerde slechts de relatie tussen ADHD-symptomatologie en werktevredenheid volledig. Er werden geen volledige mediërende effecten gevonden in de relatie tussen ADHD en levenstevredenheid. Ten slotte toonden de resultaten aan dat volwassenen met hoge ADHD zelf gerapporteerde ADHD symptomen en executief functioneren beter kunnen onderscheiden in vergelijking met volwassenen met minder ADHD symptomen.

Op basis van deze resultaten worden praktische implicaties gegeven. Daarnaast bespreken we de sterktes en beperkingen van de studie en formuleren we enkele suggesties voor toekomstig onderzoek.

6 Table of contents

INTRODUCTION ... 7

ADHD IN OCCUPATIONAL SETTINGS ... 8

ADHD AND JOB SATISFACTION ... 9

ADHD AND (WORK-RELATED)SOCIAL COMPETENCE ... 11

ADHD AND LIFE SATISFACTION ... 13

ADHD AND SELF-ESTEEM ... 15

Self-esteem & Job satisfaction ... 17

Self-esteem & social competence at work ... 18

Self-esteem & life satisfaction ... 20

ADHD AND EXECUTIVE FUNCTIONING ... 20

Executive functions in ADHD ... 21

Executive Functions and Job Satisfaction ... 22

Executive Functions and Work-Related Social Competence ... 24

Executive Functions and Life satisfaction ... 25

METHODS ... 28

PROCEDURE AND SAMPLE ... 28

DATA ANALYSIS ... 28 Data screening. ... 28 Statistical analyses. ... 28 MEASURES ... 29 Study variables. ... 30 Adult ADHD. ... 30 Control variables. ... 33 Demographical variables. ... 35 RESULTS ... 35 DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS ... 35 Sample. ... 35 Study variables. ... 37 HYPOTHESIS TESTING ... 38

Mediating effect of (organizational-based) self-esteem. ... 38

Mediating role of executive function. ... 53

DISCUSSION ... 74

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS ... 74

Self-esteem - Mediating effect of (organizational-based) self-esteem. ... 74

Executive function - Mediating effect of executive function... 78

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS ... 81

STUDY STRENGTHS ... 82

STUDY LIMITATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH ... 83

CONCLUSION ... 85

7 Introduction

The persistent belief of ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder) solely being a childhood disorder, has gradually receded and has been replaced by the current understanding that ADHD can endure across the lifespan (Kooij et al., 2010). This has translated in more research focusing on adult ADHD in clinical and, recently, occupational settings. ADHD is a relatively common condition among workers. For instance, the World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health Survey Initiative has revealed that an average of 3.7% of the working people in Belgium met the criteria for adult ADHD registered in the DSM-IV (de Graaf et al., 2008). This is substantial as much research has shown the potential negative impact of ADHD in employees on their occupational functioning. However, to the best of our knowledge, no research in Belgium has investigated work-related outcomes among employees with ADHD. Therefore, ADHD in occupational settings will be the focus of this master thesis.

In the ADHD literature, an overlooked and underresearched outcome is job satisfaction. Nonetheless, job satisfaction is important for organizations to pursue in their employees, since it is related to other valuable occupational outcomes, such as job performance, organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), counterproductive work behavior and employee withdrawal (Bowling, 2014). Moreover, in the contemporary service economy, employees’ social functioning (e.g. work-related social competence) is becoming more and more worthwhile. For this reason, job satisfaction and social competence will be the occupational outcomes of interest in this master thesis. Alongside both work-related outcomes, this paper will also encompass life satisfaction. Although not directly work-related, we believe that life satisfaction is influenced by and has itself a considerable influence on one’s working life. In addition, with the purpose of better understanding the link between ADHD and job satisfaction, social competence, and life satisfaction, the potential mediating role of two variables (i.e. (organizational-based) self-esteem and executive functioning) will be investigated.

In the next section, we will analyze the existing scientific literature to clarify the introduced concepts and their interrelations. First, the relationship between ADHD and job satisfaction, social competence and life satisfaction will be explored. Second, the potential mediating variables (i.e. (organizational-based) self-esteem and executive functioning) will be examined. In addition, some remaining research gaps in the literature

8 will be revealed and hypotheses will be formulated. Finally, the conceptual models of this research paper will be presented.

ADHD in occupational settings

In the DSM-5, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder is characterized as a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that impacts one’s functioning and development. Behavioral manifestations of inattention are, for example, the absence of persistence, lack of sustained focus, wandering off task and being disorganized, which cannot be contributed to inadequate comprehension. Hyperactivity refers to excessive motor activity when it is not appropriate, or needless fidgeting, tapping or talkativeness. In adults, hyperactivity is often less behaviorally manifested, but rather involves a feeling of restlessness. Finally, impulsivity refers to hasty actions that occur without forethought, which can possibly harm the individual (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). For many years, ADHD was considered to be exclusively a childhood condition. This persistent belief has gradually receded and has been replaced by the current understanding that ADHD can endure across the lifespan. As a result, more research has begun to focus on adult ADHD in clinical, and recently, occupational settings. Indeed, ADHD is a relatively common condition among workers. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health Survey Initiative, for instance, an average of 3.7% of the working people in Belgium met the criteria for adult ADHD registered in the DSM-IV (De Graaf et al., 2008). This is substantial as a growing body of research illustrates that the condition of ADHD negatively impacts occupational functioning. For instance, Küpper et al.’s (2012) meta-analysis presents an overview of the negative effects of adult ADHD on work productivity and occupational health. The adverse effects of the condition of ADHD range from higher unemployment rates to reduced productivity over increased risk of accidents and higher absenteeism. Moreover, employers rate adults with ADHD as less adequate in fulfilling job demands, less likely to be working independently and less likely to cooperate well with supervisors (Weiss & Hechtman, 1993). When children with ADHD were followed into adulthood, they had a lower job status compared to controls, received lower job performance ratings from employers, and had a greater likelihood of dismissal from the job (Barkley et al., 2008). Biederman et al. (2008) further identified that adult ADHD was significantly related to educational and occupational

9 underachievement, especially relatively to expectations based on their intellectual potential. A similar conclusion was found by Gjervan et al. (2012).

ADHD and Job satisfaction

The negative impact of ADHD on occupational functioning is thus widespread. However, in the ADHD literature, job satisfaction is often overlooked as a work-related outcome. Hence, in this paper, we will examine the relationship between ADHD and job satisfaction.

Job satisfaction can be defined as an attitude that represents the extent to which a person likes or dislikes their job (Brief, 1998). Similar to other attitudes, job satisfaction encompasses both an affective and a cognitive component (Schleicher, Watt & Greguras, 2004). The former includes the emotions or feelings towards one’s job (e.g. feelings of excitement), whereas the latter incorporates one’s thoughts or beliefs about the job (e.g. beliefs that one’s job offers autonomy or variety). In the literature, two distinct approaches to operationalize job satisfaction are used: the global approach and the facet approach. Global job satisfaction focuses on the overall attitude of workers toward their jobs. The facet approach to job satisfaction, on the other hand, includes workers’ attitudes toward specific aspects of their job (e.g. work tasks, pay, supervision). Hence, the facet approach acknowledges that a worker can experience feelings of satisfaction with regard to some aspects of work, but, simultaneously, feelings of dissatisfaction with regard to other aspects (Bowling, 2014). In this paper job satisfaction will be operationalized in concordance with the global approach.

A study by Painter et al. (2008) investigated the effects of ADHD symptomatology on both intrinsic and extrinsic job satisfaction. Intrinsic job satisfaction was conceptualized as those aspects of work and the work environment that enable the individual to experience satisfaction because of his or her abilities. Extrinsic job satisfaction, on the other hand, referred to those aspects of work and the work environment that enable the individual to experience satisfaction because of the actions of others or policies. It appeared that lower levels of ADHD symptomatology were associated with higher extrinsic job satisfaction. The effects of ADHD symptoms on intrinsic job satisfaction were nonsignificant in this study.

10 Aside from the study of Painter et al. (2008) none other study has, as far as we know, studied the relation between ADHD and job satisfaction. Nevertheless, job satisfaction might be of interest to both researchers and practitioners since it is known to be related to other valuable occupational outcomes. For instance, a positive association between job satisfaction and job performance has repeatedly been found (Iaffaldano & Muchinsky, 1985; Judge, Thoresen, Bono, & Patton, 2001). Many researchers and lay people even believed this relation to be causal (Bowling, 2007). However, theoretical positions concerning this matter disagree: some argue that satisfaction causes performance, others suggest that performance causes satisfaction, and still others propose a bidirectional relationship (Bowling, 2014). Some evidence even suggests the relation to be spurious (Bowling, 2007). Albeit the opposing viewpoints, decades of research support the existence of a positive association between job satisfaction and job performance, in one way or another. Moreover, research has found a positive association between global job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) (Dalal, 2005; LePine, Erez & Johnson, 2002). OCB involves behaviors that are not explicitly stated in the job description, that are, however, meaningful to the organization as a whole or the individuals at work (Organ & Ryan, 1995). Thus, when employees engage in OCB, they are willing to go the extra mile. In addition, a meta-analysis of Dalal (2005) revealed a negative correlation between global job satisfaction and counterproductive work behavior (CWB), which refers to deviant behaviors intended to harm the organization as a whole or the people at work. Indeed, as the principle of reciprocity suggests, dissatisfied workers may engage in CWB as a way of revenge or compensation for the unpleasant work environment (Dalal, 2005). It can further be assumed that employees who are dissatisfied, are more likely to withdraw from work. Indeed, meta-analyses have found that global job satisfaction is negatively related to lateness (Koslowsky, Sagie, Krausz, & Singer, 1997), absenteeism (Farrell & Stamm, 1988), and turnover (Griffeth, Hom, & Gaertner, 2000). Finally, it has been found that job satisfaction is positively related to customer satisfaction (Mendoza & Maldonado, 2014). In sum, job satisfaction is related to various outcomes that managers seek in their employees.

Job satisfaction has received little attention in the ADHD literature. However, job satisfaction is as important as other work-related outcomes, such as job performance, absenteeism, and turnover. Hence, this paper aims to investigate the interrelation between

11 ADHD and job satisfaction. It can be assumed that those with ADHD experience lower job satisfaction. First, as described earlier, the condition of ADHD negatively impacts various occupational outcomes. Given that most, if not all, of these outcomes are related to job satisfaction, one could assume that job satisfaction is also decreased in those with ADHD. Second, there is evidence to suggest that ADHD is associated with occupational underattainment, relatively to their intellectual abilities (Biederman et al., 2008). This reduced occupational fulfillment might induce lower job satisfaction since job status is related to job satisfaction (Robie et al., 1998): the lower the job status, the lower job satisfaction. In line with this reasoning, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: ADHD is negatively related to job satisfaction.

ADHD and (Work-Related) Social Competence

In a study by Friedman et al. (2003) self-report measures were used to assess social and emotional competence in adults with ADHD. The results showed that solely social competence was diminished in those with ADHD compared with their non-ADHD counterparts. Therefore, the focus of this paper will be on social, rather than emotional competence in ADHD employees.

Social competence involves the skills that facilitate interpersonal interactions in the social environment. These skills encompass expression and control of verbal and nonverbal communication (Friedman et al., 2003). Research has shown that childhood ADHD is associated with social malfunctioning (Dupaul et al., 2001; Landau et al., 1998; Larson et al., 2007). Also, adolescents with ADHD experience a troublesome social functioning (e.g. problems with making friends, difficulties with cooperating and getting along with others) (Sacchetti et al., 2017). However, research concerning adults with ADHD is sparse. One study by Friedman et al. (2003) investigated social and emotional competence in adults with ADHD, using both self-report and behavioral measures. These authors found indeed that deficits in social and emotional competence were present in adults with ADHD. With regard to social functioning, the adults indicated that they view themselves as less socially skilled at regulating their social behavior. They also expressed greater concern regarding the appropriateness of their behavior in social situations and greater sensitivity toward violations of social norms than did their non-ADHD counterparts.

12 Employees’ social functioning is gaining importance in the contemporary service economy. As part of their daily work, employees in service activities have to interact with others, be it costumers, patients, students or children, which demands a certain degree of social skills. Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that the social competence of employees working in the services sector is the most powerful predictor of customer satisfaction (Kanning & Bergmann, 2006). In addition, as a result of increasing workplace complexity, today’s organizations depend more and more on teams to deal effectively with the challenging environment (Salas, Cooke & Rosen, 2008). Since teams are social entities, social competence is crucial for teams to work effectively. For instance, Morgeson, Reider, and Campion (2005) found that social competence predicted contextual performance in team settings. Moreover, a study of Meyer, Schermuly and Knauffeld (2016) revealed that team members who were part of a team with strong faultlines (i.e. hypothetical dividing lines that split a team into relatively homogenous subgroups), who fit in the larger subgroup in their team, and who displayed low levels of social competence, exhibited more social loafing. Adequate levels of social competence in team members are thus required to overcome such detrimental effects. Hence, the authors suggest that social competence could be a selection criterion when staffing positions in diverse teams. This has also been proposed outside team settings. For example, Jansen, Melchers & Kleinmann (2012) aimed to investigate whether the prediction of job performance could be improved via the use of a self-report inventory on social competence combined with personnel selection procedures such as assessment centers and structured interviews. Their results indicated positive correlations between social competence and performance on the job, in the assessment center and in the structured interview. Social competence further added incremental validity beyond the assessment center and interview performance and significantly contributed to the validity of the prediction of job performance. This illustrates that self-report inventories on social competence can be useful for personnel selection.

As said, research on social competence at work in adults with ADHD is scarce. This is unfortunate in view of the increasing value of social functioning in employees. After all, one can assume that a lack of social competence may constitute a greater problem in the workplace for ADHD patients than the classical symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity,

13 and impulsivity. Therefore, this paper will investigate the link between ADHD and social competence in the workplace.

Since there is evidence to suggest deficits in social functioning in children (Landau et al., 1998; Dupaul et al., 2001; Larson et al., 2007), adolescents (Sacchetti et al., 2017) and, limitedly, in adults with ADHD (Friedman et al., 2003), one can assume an inadequate level of social competence in ADHD adults. Second, as social competence refers to social skills encompassing the expression and control of verbal and nonverbal communication (Friedman et al., 2003) and as core symptoms of ADHD are hyperactivity and impulsivity, we expect that ADHD among employees might impede their social functioning, including their communication behavior at work. In line with this reasoning, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: ADHD is negatively related to social competence at work.

ADHD and Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction is one key indicator of Subjective Well-Being (SWB) or one’s overall happiness and, is composed of a cognitive assessment of satisfaction with life circumstances (Linley, Maltby, Wood, Osborne, & Hurling, 2009). Life satisfaction can be defined as the degree to which a person is pleased with their own life (Veenhoven, 1996). In scientific literature, two approaches to life satisfaction can be distinguished: a top-down and a bottom-up approach. In the top-down approach, life satisfaction is explained through stable traits. In other words, this approach assumes that some people have a certain propensity to be more satisfied with their lives. The bottom-up approach, on the other hand, believes life satisfaction is composed of satisfaction with multiple life domains, such as work, health, and leisure (Erdogan, Bauer, Truxillo, & Mansfield, 2012).

As stated in the DSM-5, the condition of ADHD in adults negatively affects social, academic and occupational functioning (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Considering these impairments in several domains of life, one can easily assume individuals with ADHD experience decreased life satisfaction. There is indeed evidence to suggest that the condition of ADHD is associated with lower satisfaction with life. For instance, in a sample of ADHD adults aged 50+, Lensing, Zeiner, Sandvik and Opjordsmoen (2015) found that the adults diagnosed with ADHD reported reduced satisfaction with life and lower quality of life. Mick, Faraone, Spencer, Zhang, and

14 Biederman (2008) documented similar results. Lastly, decreased satisfaction in adults with ADHD was also observed in a study by Hennig, Koglin, Schmidt, Petermann, and Brähler (2017). These authors further found this association was mediated by both social support and depressive symptoms.

Although not directly work-related, life satisfaction is still relevant in the workplace, since it is related to an array of occupational outcomes. For instance, the results of Jones (2006) suggest that life satisfaction has a stronger correlation with job performance compared to job satisfaction. Moreover, job and life satisfaction tend to be related to one another (Bowling, Eschleman & Wang, 2011). These authors further demonstrated that the causal relationship from subjective well-being (SWB) to job satisfaction was stronger than the causal relationship from job satisfaction to SWB. In addition, there is evidence to suggest that life satisfaction is related to commitment. In their meta-analysis, Erdogan et al. (2012) found an average correlation of .30 between life satisfaction and organizational commitment. The findings of a study of Iranian nurses further suggest that life satisfaction predicted commitment beyond working conditions (Vanaki & Vagharseyyedin, 2009). Furthermore, research suggests life satisfaction is related to withdrawal and turnover. For example, a negative correlation between life satisfaction and absenteeism has been reported (Murhpy, Duxbury, & Higgins, 2006; Shaw & Gupta, 2001). Von Bonsdorff, Huuhtanen, Tuomi, and Seitsamo (2010) further indicated that life satisfaction was negatively related to early retirement intentions, which is particularly relevant in the light of contemporary debates about the age of retirement. With regard to turnover, Shaw & Gupta (2001) found a negative correlation between life satisfaction and actual turnover. The results for life satisfaction’s relation to turnover intentions are, however, not clear. It can indeed be assumed that life satisfaction is related to turnover to the degree to which one’s job is the reason for the dissatisfaction with life (Erdogan et al., 2012).

In sum, there is evidence to suggest life satisfaction is influenced by and has itself an effect on one’s working life. Therefore, we believe it important to incorporate life satisfaction as a potential outcome variable in this paper. Considering the condition of ADHD has a negative impact on several areas of life, one can presume life satisfaction to be diminished in those with ADHD. Previous research has indeed repeatedly documented that ADHD is related to reduced satisfaction with life (Hennig et al., 2017; Lensing et al.,

15 2015; Mick et al., 2008). As this relation has not yet been studied in Belgium, and neither been studied in literature among employed ADHD adults, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: ADHD is negatively related to life satisfaction.

Next to studying three potential outcomes of ADHD in adults (cf. supra: Hypotheses 1,2 and 3), this study also analyses the potential mediating role of two variables ((organizational-based) self-esteem and executive functioning). Both mediators and their implied hypotheses will be described below.

ADHD and Self-esteem

Whereas the self-concept refers to the manner in which we view ourselves (i.e. “who am I?”), self-esteem refers to the evaluative component of the self-concept (Cook, Knight, Hume & Qureshi, 2014). Campbell and Lavallee (1993) identify self-esteem as “how I feel about who I am”. In addition, two contentious approaches towards self-esteem have been proposed in the literature: a unidimensional and a multidimensional approach (Cook et al., 2014). In the unidimensional approach, self-esteem is defined as an individual’s positive or negative attitude toward the self as a totality (Rosenberg, Schooler, Schoenbach & Rosenberg, 1995). Hence, the unidimensional approach defines self-esteem as stable and global. The multidimensional approach, on the other hand, emphasizes that self-esteem depends on the context. For instance, one may feel intelligent (high academic self-esteem), but may feel incompetent when interacting with others (low social self-esteem). Following the multidimensional approach, Heatherton and Polivy (1991) established a scale for assessing 3 aspects of self-esteem: performance self-esteem, appearance esteem, and social esteem. It seemed, however, that the specific esteem measures are intercorrelated, which means that people who tend to have high self-esteem in one area of life also tend to have high self-self-esteem in other areas (Larsen, Buss & Wismeijer, 2013). Although, the fact that the specific self-esteem measures are intercorrelated, suggests that global self-esteem is composed of one’s self-evaluations in several areas of life, both specific and global self-esteem measurements can be meaningful. Indeed, Rosenberg et al. (1995) argued that both approaches are neither equivalent nor interchangeable. Furthermore, these authors suggested that global and specific self-esteem measures clearly have different correlates. For instance, their

16 research indicated that global self-esteem tends to be associated with overall psychological well-being, whereas specific self-esteem appears to be more correlated with behavioral outcomes. Hence, this paper will encompass both a global and a specific self-esteem measure (i.e. organizational-based self-esteem).

Everyday experiences and interactions are fundamental to the development of self-esteem. These experiences make people believe they are lovable, competent, intelligent, or the contrary (Cook, Knight, Hume & Qureshi, 2014). As they grow up individuals with ADHD are, however, often confronted with negative messages concerning their abilities (Young et al. 2008) and they may experience adverse outcomes throughout their lives (Mannuzza & Klein 2000). It has been suggested that underachievement, alongside numerous negative experiences and negative messages about one’s abilities, as often experienced by individuals with ADHD, affects the development of self-esteem (Cook et al., 2014). In addition, the diagnosis of ADHD is stigmatized. For instance, individuals express less desire to interact with peers diagnosed with ADHD, compared to peers with minor medical problems or with no substantial weakness (e.g. perfectionism) (Canu, Newman, Morrow & Pope, 2008). Moreover, in a study by Thompson and Lefler (2016) in college students, it was found that the stigma towards ADHD was associated with the behavioral manifestations of ADHD, but not with the label itself. When the college students rated both ADHD and depression, it appeared that both were equally stigmatized. The stigma regarding ADHD can further hamper the development of self-esteem among those diagnosed with the disorder. Hence, individuals with ADHD often experience failure and negative social feedback. Such adverse encounters may provoke negative cognitions which may worsen problems through avoidance and decreased motivation. Furthermore, adults with ADHD often develop futile coping styles, in that they react to difficult or stressful situations with avoidance and procrastination (Knouse & Safran, 2010). Consequently, esteem is unlikely to improve, and, on top of that, low self-esteem will be reinforced because these individuals remain unable to cope, hence leading to continual disappointment (Newark & Stieglitz, 2010). In their meta-analysis, Cook et al. (2014) aimed to review the research regarding self-esteem among adults with ADHD. As regards to group differences, all reviewed studies found that adults with ADHD had reduced self-esteem compared to healthy controls. When controlling for demographic variables such as gender, IQ and socio-economic status, the effects persisted

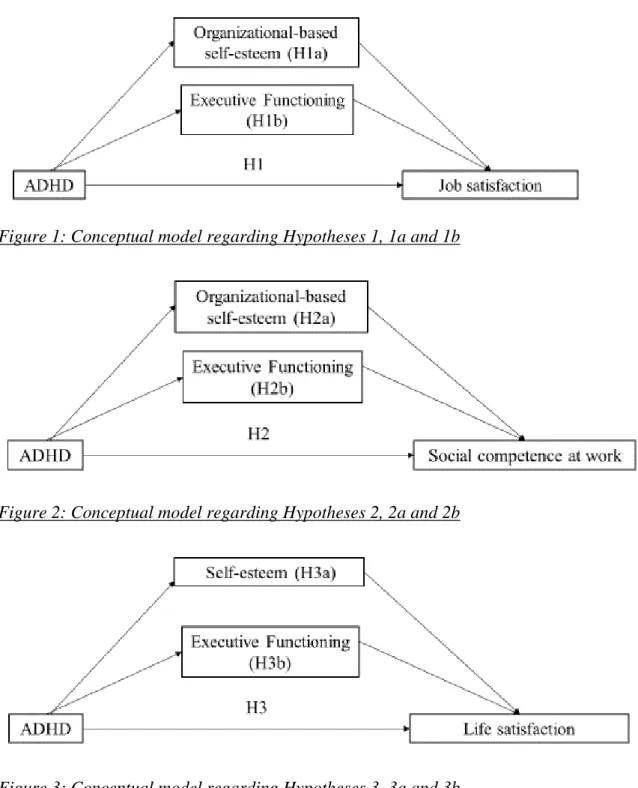

17 notwithstanding. Thus, one can assume that something inherent in the condition of ADHD correlates with reduced self-esteem (Cook et al., 2014). Furthermore, research has revealed the existence of a strong correlation between ADHD symptomatology and self-esteem (Dan and Raz 2012; Rucklidge and Kaplan 1997): as the current symptomatology of ADHD increased, self-esteem decreased. These results suggest that self-esteem at large and a lowered self-esteem among employed ADHD adults in particular, might be a psychological mechanism or explain the relation between ADHD and its outcomes. In the next section, we describe the potential mediating effect of reduced self-esteem on the outcome variables of this study, namely job satisfaction, social competence at work and life satisfaction (see Figures 1, 2 and 3).

Self-esteem & Job satisfaction

Previous research has indicated that self-esteem is positively related to job satisfaction (Judge & Bono, 2001). Longitudinal studies have even suggested that self-esteem predicts changes in job satisfaction (Judge, Bono, & Locke, 2000; Judge & Hurst, 2008). A study by Orth, Robins, and Widaman (2012) further demonstrated that self-esteem is rather a cause than a consequence of job satisfaction.

Beyond global self-esteem, theorists have argued that individuals develop a self-concept around work and, that their self-esteem is also determined by organizational experiences (Pierce & Gardner, 2004). Consequently, Pierce, Garder, Cumming, and Dunham (1989) introduced the concept of ‘organizational-based self-esteem’, which they describe as “the self-perceived value that individuals have of themselves as organization members acting within an organizational context” (p.625). It encompasses feelings and believes of worthiness, meaningfulness, and competence as a member of the organization. In short, organizational-based self-esteem refers to an attitude toward oneself as an organizational member. Pierce et al. (1989) further argued that organizational-based self-esteem is rooted in one’s experiences at work.

Job satisfaction has received some attention in research on organizational-based self-esteem. Akin to the relation with global self-esteem, Pierce et al. (1989) found a positive correlation between organizational-based self-esteem and job satisfaction. Evidence has repeatedly been provided for such interrelation (Gardner, Huang, Niu, Pierce & Lee, 2015; Gardner & Pierce, 2004; Ragins, Cotton & Miller, 2000; Van Dyne & Pierce, 2004).

18 In sum, a considerable body of evidence suggests that employees with high organizational-based self-esteem, tend to have higher job satisfaction. To the best of our knowledge, no research has explicitly focused on the relation between ADHD and organizational-based self-esteem. On the other hand, it is well documented that the condition of ADHD is often accompanied by reduced self-esteem (Cook et al., 2014). Similarly, we assume that organizational-based self-esteem will be diminished in those with ADHD. The condition of ADHD negatively affects occupational functioning. Such occupational impairment potentially reduces organizational-based self-esteem, as it is considered to be grounded in organizational experiences (Pierce et al., 1989). Based on previous research on the interrelation between organizational-based self-esteem and job satisfaction, we further assume that, due to decreased organizational-based self-esteem, individuals with ADHD will experience lower job satisfaction.

H1a: The negative effect of ADHD on job satisfaction is mediated by organizational-based self-esteem, such that ADHD is characterized by decreased organizational-organizational-based self-esteem, which in turn decreases job satisfaction.

Self-esteem & social competence at work

In this paper, we further aim to investigate the effect of self-esteem on social competence at work. It can indeed be assumed that social competence affects self-esteem, in that socially competent individuals experience greater social self-esteem, as a result of their mastery in social situations (Riggio, Throckmorton & DePaola, 1990). On the other hand, it can be suggested that self-esteem determines social competence. Those with greater self-esteem might be more effective in social interactions since they are not hampered by feelings of insignificance and incompetence.

A study by Riggio, Throckmorton & DePaola (1990) aimed to investigate the interrelations among a self-report measure of social competence (Social Skills Inventory (SSI)) and measures of esteem (Janis-Field esteem and Coopersmith self-esteem). These authors indeed found a positive correlation between self-reported social competence measures and both measures of self-esteem. Not only the total SSI score seems to be related to self-esteem, the three subscales for social competence (i.e. Social Expressivity, Social Sensitivity, and Social Control) are also individually significantly correlated to self-esteem. The results show that self-esteem is positively related to both Social Expressivity and Social Control and negatively to Social Sensitivity. These results

19 indicate that individuals with greater self-esteem are more expressive and able to engage others in social situations, are more capable of appropriate verbal behavior and self-representation in social encounters, and less concerned about governing their behavior in social situations. The relationship between social skills and self-esteem has, furthermore, been investigated among a sample of nurses (Losa-Iglesias, López López, Rodriguez Vazquez & Becerro de Bengoa-Vallejo, 2017). These authors focused on three social skills factors that are considered crucial to establishing a good clinician-patient relationship (i.e. self-expression in social situations, expressing of anger or displeasure, and saying “no” and cutting interactions). A significantly positive correlation was found between self-esteem and two of the social skills factors, namely self-expression in social situations, and saying “no” and cutting interactions. The results further indicate that all three social skills factors contribute to the prediction of nurses’ self-esteem. A study by Frone (2000) further found that employees with high self-esteem rapport less conflict with their coworkers compared to employees with low self-esteem. In addition, a study by LePine and Van Dyne (1998) demonstrated that individuals with high self-esteem are more willing to speak up in group. Such voice behavior is crucial to innovation and an organization’s long-term success.

In sum, previous research indicated a positive relation between self-esteem and social competence. In addition, there is some evidence to suggest social competence might contribute to the prediction of self-esteem. In this paper, we aim to contribute to the literature of social competence at work. Particularly, we aim to investigate whether work-related social competence can be predicted by organizational-based self-esteem in individuals with ADHD. There is evidence to suggest both social competence and self-esteem are reduced in those with ADHD. We assume that the reduction in organizational-based self-esteem can provide an explanation for the lack of social competence in ADHD adults. Indeed, when one feels incompetent and insignificant at work, one might be less appropriate and effective in social situations. Hence, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2a: the negative effect of ADHD on social competence at work is mediated by organizational-based self-esteem, such that organizational-based self-esteem is decreased in individuals with ADHD, which in turn decreases their social competence at work.

20 Self-esteem & life satisfaction

A considerable body of research has provided evidence for a positive association between self-esteem and life satisfaction. For instance, in an international study among college students in 31 countries, a significant correlation of .47 between self-esteem and life satisfaction was found. In fact, it appeared that self-esteem was the strongest predictor of life satisfaction (Diener & Diener, 1995). Similarly, self-esteem and life satisfaction emerged to be strongly correlated (r = .58) in a sample of older adults (Lyubormirsky, Tkach & DiMatteo, 2006), as well as in a sample of adolescents (r = .49) (Marcionetti & Rossier, 2016). In addition, a study by Shackelford (2001) among couples who had been recently married, indicated that self-esteem was significantly correlated with global, sexual and emotional satisfaction.

In sum, these results provide evidence for a strong interrelation between self-esteem and life satisfaction. In a literature review, Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, and Vohs (2003) further argue that individuals with high self-esteem exercise more self-regulatory strategies than individuals with low self-esteem and, that these strategies may determine their higher levels of reported life satisfaction. With regard to individuals with ADHD, we believe similar processes are at play. Indeed, individuals with ADHD often receive negative messages concerning their abilities (Young et al. 2008) and they may experience adverse outcomes throughout their lives (Mannuzza & Klein, 2000). Such adverse encounters may negatively impact self-esteem and provoke negative cognitions. Consequently, adults with ADHD often develop unhelpful coping styles (Knouse and Safran, 2010). Therefore, we aim to investigate the potential mediating effect of self-esteem in the relation between ADHD and reduced life satisfaction.

H3a: the negative effect of ADHD on life satisfaction is mediated by self-esteem, such that ADHD decreases self-esteem, which in turn decreases life satisfaction.

ADHD and Executive Functioning

Problems of attention have long been the focus of ADHD research as it was assumed to be the core deficit of the disorder (Douglas, 1999). This focus has gradually shifted towards executive functioning. There is evidence to suggest that executive functioning (EF) deficits may be an aspect of the disorder, although not yet recognized as a symptom of ADHD. It has further been suggested that the symptom dimensions of ADHD actually express dimensions of EF (Antshel, Hier & Barkley, 2014). Thus, research has shown

21 that the condition of ADHD is associated with impaired EF. The definition of executive functioning is somewhat contentious and theorists have defined EF in multiple manners. For instance, Welsh & Pennington (1988) offered the following definition of EF: “the ability to maintain an appropriate problem solving set for attainment of a future goal” (p.201). Lezak, Howieson, Loring & Hannay (2004) defined executive functions as “those capacities that enable a person to engage successfully in independent, purposive, self-serving behavior” (p.42).

Executive functions in ADHD

A growing body of research has provided evidence for an impairment of the EF in those with ADHD. In his theory, Barkley (1997) suggested behavioral inhibition to be the core deficit in ADHD. He further argued that this lack of self-stopping generates an accumulation of supplementary deficits in the other EFs. Indeed, the results of Nigg (2001) demonstrate that ADHD is related to behavioral inhibition impairment. Moreover, there is evidence to suggest that the condition of ADHD is not only associated with response inhibition deficiencies. It seems that ADHD is further characterized by a diminishment in nonverbal working memory, timing and foresight (Frazier, Demaree, & Youngstorm, 2004; Rapport et al. 2008). Alongside working memory deficiencies, an additional impairment associated with ADHD is delayed privatization of speech. Research has shown that decreased private speech can generate excessive talking, less verbal reflection before acting, less organized and rule-oriented self-speech, little influence of self-directed speech in controlling one’s own behavior, and difficulties following the rules and instructions given by others (Berk & Potts, 1991; Winsler, Diaz, Atencio, McCarthy, & Chabay, 2000). ADHD is further characterized by decreased emotional and motivational self-regulation. For instance, those with ADHD will display more impulsivity in their emotional expression when reacting to an event and less objectivity in response selection. In addition, those with ADHD lack social perspective taking, since they cannot delay their initial responses long enough (decreased behavioral inhibition). Moreover, when feeling strong emotions, individuals with ADHD experience more difficulties in self-soothing, and, when faced with an emotional trigger, they lack the ability to distract themselves and redirect their attention as to diminish the value of the provocative stimulus. Furthermore, individuals with ADHD are less able to construct more socially appropriate and moderate emotions that will be more beneficial for their

22 long-term wellbeing (Antshel et al, 2014). It has indeed been found that ADHD is related to impaired emotion-regulation (Christiansen, Hirch, Albert & Chavanon, 2019; Skirrow et al., 2014; Surman et al. 2011). It has further been suggested that the emotional dysregulation in individuals with ADHD contributes to common comorbidities of the disorder: depression and personality disorders (Christiansen et al., 2019). With regard to motivational self-regulation, it is well documented that those with ADHD depend more on their environment to determine their motivation compared to others (Barkley, 1997). Lastly, Barkley’s (1997) model further suggested that self-play is decreased in individuals with ADHD. Indeed, there is evidence to suggest a deficiency in verbal and nonverbal fluency, planning, problem-solving, and strategy development in those with ADHD

(Clark, Prior & Kinsella, 2000; Klorman et al., 1999). These results suggest that reduced executive functioning at large and a diminished executive functioning among employed ADHD adults in particular might be a psychological mechanism or explain the relation between ADHD and its outcomes.

In the next section, we describe the potential mediating effect of reduced executive functioning and how it might affect the outcome variables of this study, namely job satisfaction, work-related social competence, and life satisfaction (see Figures 1, 2 and 3).

Executive Functions and Job Satisfaction

Limited research has focused on ADHD and executive functioning in the workplace. One study of Barkley and Murphy (2010) has explicitly linked executive function measures to occupational outcomes. These authors found that executive function deficits contribute to occupational impairments experienced by those with ADHD. Moreover, they suggest that self-ratings of executive functioning may be more predictive for difficulties in past and current occupational functioning compared to EF tests (e.g. Stroop Color-Word Test or Wisconsin Card Sort Test). With regard to job satisfaction, two outcome measures seem relevant, namely “self-rated quality of work” and “percent jobs quit due to boredom”. The results show that these measures are predicted by Self-Motivation, which can be defined as one’s ability to work toward long-term goals or rewards, to sustain consistent effort, to work without supervision, and to exercise willpower (Allee-Smith, Winters, Drake & Joslin, 2013). Consistent with these results, Barkley and Fischer (2011) indicated that impairments in workplace functioning were better predicted by EF ratings

23 than EF tests. This study also illustrates that executive function deficits are related to occupational outcomes. We will consider the outcome variables “self-rated quality of work” and “percentage of jobs quit due to boredom” as relevant indicators for job satisfaction. A significantly positive correlation between “self-rated quality of work” and all 5 subscales of the Deficits in Executive Functioning Interview (DEFI) was found, which demonstrates that executive functioning is associated with occupational functioning. “Percentage of jobs quit due to boredom”, on the other hand, was only significantly positively correlated to the dimension of Self-Motivation. The authors further attempt to determine which of the DEFI scales made unique contributions to predicting the occupational outcomes. The results reveal that “self-rated work quality” can be predicted by both Self-Organization and Problem Solving, and Self-Motivation. However, solely Self-Motivation contributed to the prediction of “percentage of jobs quit due to boredom”.

In sum, there is evidence, however limited, to suggest that the executive functions are related to and can contribute to the prediction of occupational outcomes (Barkley & Fisher, 2011; Barkley & Murphy, 2010). Based on Barkley’s (1997) theory of executive functioning, it can indeed be assumed that occupational impairment in individuals with ADHD is related to executive function deficits. The definition of adult ADHD in the DSM-5 explicitly implies that the disorder results in academic, social and occupational impairments (APA, 2013). Hence, a theory, which attempts to explain the behavioral symptoms of ADHD, can contribute to a better understanding of workplace impairment. Consistent with previous research we assume that especially the aspect of “emoting and motivating to the self” is related to reduced job satisfaction in ADHD. As noted previously, ADHD is related to emotional dysregulation (Christiansen, Hirch, Albert & Chavanon, 2019; Skirrow et al., 2014; Surman et al. 2011). Hence, they will display greater difficulties in self-soothing when experiencing strong emotions (Antshel et al. 2014). Such difficulties can negatively impact job satisfaction since job satisfaction encompasses not only a cognitive but also an emotional component. Alongside difficulties in emotional self-control, the absence of motivational self-regulation might negatively affect job satisfaction as well. Individuals with ADHD will pursue immediate gratification over delayed gratification and rely heavily on their external environment to determine their motivation (Antshel, 2014). However, the workplace environment is often

24 characterized by delayed rewards: salary is only received once a month and the positive effects of completing assigned work are, in general, not always observable or tangible for the employee. Hence, based on theory and previous research, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1b: The negative effect of ADHD on job satisfaction is mediated by EF, such that EF is reduced in those with ADHD, which in turn decreases job satisfaction.

Executive Functions and Work-Related Social Competence

Research regarding social competence at work is sparse. However, the study by Barkley and Murphy (2010) encompasses an outcome variable referring to this matter, namely “percentage of jobs had in which one had trouble getting along with others”. The results show that this outcome is predicted by inhibition, which refers to aspects of impulsivity, foresight and hindsight, frustration tolerance and the ability to inhibit responses prior to considering their consequences (Allee-Smith et al., 2013). In addition, Barkly and Fischer (2011) investigated the link between executive functioning and trouble getting along with others at work. These authors found a significantly positive correlation with all dimensions of the DEFI scale. They further examined the unique contribution of the DEFI subscales to the prediction of occupational outcomes. With regard to “percentage of jobs characterized by trouble getting along with others”, it seems that solely Self-Organization and Problem-solving can significantly predict the outcome. This subscale refers to difficulty with order and sequencing, information processing accuracy and speed, learning, and problem-solving abilities (Allee-Smith et al., 2013).

Consistent with previous research, we assume a link between EF deficits and decreased social competence at work in those with ADHD. Based on Barkley’s (1997) theory of EF, there is a ground of belief for such association. First, self-control and the performance of the executive functions are rooted in behavioral inhibition, the core deficits in ADHD. Yet, the purpose of self-control and the executive functions is believed to be inherently social: humans engage in reciprocal social exchanges and alliance building as a means to their survival. Therefore, they must be able to both behold earlier interactions with others and prepare for such future interactions (Antshel et al., 2014). Hence, it is reasonable to assume EF deficits to have a negative effect on social functioning. Second, privatization of speech is often delayed in individuals with ADHD. There is evidence to suggest that decreased internalization of speech generates excessive talking, less verbal reflection

25 before acting, and difficulties following the rules and instructions given by others (Berk & Potts, 1991; Winsler, Diaz, Atencio, McCarthy, & Chabay, 2000). Such behavior can indeed be detrimental to social interaction. Third, individuals with ADHD experience difficulties in emotional self-regulation. Research has, for example, noted that adults with ADHD often experience mood instability in the form of irritability, swift changes in mood, hot temper and low frustration tolerance (Skirrow et al., 2014; Surman et al. 2011). Such emotional dysregulation can further negatively affect social functioning as those with ADHD will, for instance, display less objectivity in the selection of a response. Particularly in combination with a lack of behavioral inhibition, emotional self-regulation deficits might be disastrous to social interaction. For instance, since individuals with ADHD cannot delay their initial responses long enough, they lack social perspective taking. Furthermore, due to the absence of response inhibition, those with ADHD are less able to construct more socially appropriate and moderate emotional responses (Antshel et al., 2014). In this paper we assume that these processes are also at play for employed ADHD adults in the workplace. As the mediating role of executive functioning in the relation between ADHD and social competence at work has not yet been studied among employed ADHD adults and based on research and the theory of EF (Barkley, 1997) we formulate the following hypothesis:

H2b: The negative effect of ADHD on social competence at work is mediated by EF, such that EF is diminished in those with ADHD, which in turn decreases their social competence at work.

Executive Functions and Life satisfaction

Limited research investigated the potential effect of executive function deficits on the life satisfaction of individuals with ADHD. One study by Stern, Pollak, Bonne, Malik, and Maeir (2013) explicitly investigated the relationship between executive functions and quality of life in adults with ADHD. These authors found small to large significant correlations between adult ADHD Quality-of-Life Scale and five subscales of the BRIEF-A, a report measure of EF. Moreover, reported symptoms of ADHD and self-reported executive function deficits each uniquely contributed to quality of life in adults with ADHD. These results clearly indicate an effect of executive function deficits on quality of life in individuals diagnosed with ADHD. In addition, a study by Barkley and Murphy (2010) found a great contribution of executive function test to the prediction of

26 clinical SOFAS (Social Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale) rating, a measure of social, occupational and educational functioning. Since this measure encompasses major aspects of life, it might be indicative of one’s quality of life. Furthermore, in a study among adults with learning disabilities, Sharfi and Rosenblum (2016) found that quality of life was predicated by 3 subscales of the BRIEF-A, a self-report questionnaire that measures behavioral manifestations of executive functioning, namely Task Initiation, Emotional Control, and Time Management.

In sum, these results indicate the presence of a link between executive function deficits and reduced quality of life. Life satisfaction can be defined as the degree to which a person is pleased with their own life (Veenhoven, 1996). Hence, one’s life satisfaction will probably be based on one’s perceived quality of life. Considering this, one can assume executive function deficits to negatively affect life satisfaction. The executive functions are essential for future-directed behavior: it enables attention to the future and adequate preparedness for its arrival (Antshel et al., 2014). Hence, the executive functions empower us to deal with the obstacles of life. In addition, individuals with ADHD often experience difficulties with emotion regulation (Christiansen, Hirch, Albert & Chavanon, 2019; Skirrow et al., 2014; Surman et al. 2011). However, adequate emotion regulation strategies might counterbalance the negative effects of stressful events on life satisfaction (Ng, Huebner, Hills & Valois, 2018). Hence, the absence of such strategies in individuals with ADHD can undermine their life satisfaction. Furthermore, by means of mental representations and time management, the executive functions enable goal-accomplishment (Antshel et al., 2014). One could assume that the inability to reach one’s goals will negatively affect one’s life satisfaction. As the mediating role of executive functioning in the relation between ADHD and life satisfaction has not yet been studied among employed ADHD adults and based on theory and previous research, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3b: the negative effect of ADHD on life satisfaction is mediated by EF such that EF is reduced in those with ADHD, which in turn decreases life satisfaction.

27 An overview of our study hypotheses is depicted below (see Figures 1, 2 and 3).

Figure 1: Conceptual model regarding Hypotheses 1, 1a and 1b

Figure 2: Conceptual model regarding Hypotheses 2, 2a and 2b

28 Methods

Procedure and Sample

As we aimed to recruit a heterogenous sample of employees diagnosed with ADHD, we applied the following inclusion criteria for study participation: (1) being diagnosed with ADHD or (seriously) suspecting to have the condition, (2) being adult (18 years or older) and (3) paid employment at the time of study. No inclusion criteria for study participation regarding subjects’ number of working hours, job type, profession or industrial sector, etc. were set.

Recruitment of participants occurred in two phases. In a first step, specialized support groups working with ADHD adults (e.g. centrum ZitStil, Aandacht vzw) were contacted. Due to the low response rate obtained via these support groups, we consulted, in a second phase, social media communities directed at adults with ADHD. Members of these communities living in Belgium were individually contacted and requested to participate in the study if they met all mentioned inclusion criteria.

All data were collected via an anonymous online self-report survey. At the beginning of the survey we asked for participants’ consent and participation in the study occurred on a voluntary basis. This all resulted in a sample of 129 participants. Partial responses were automatically excluded.

Data analysis

Data screening.

5 responses, although complete, were registered as incomplete because the end-of-survey-message was not displayed to these participants. These responses were manually added to the dataset. Participants were forced to respond each item in the online survey and partial responses were automatically excluded from the dataset. Hence, missing values were no issue. Furthermore, before analysis, reverse items were recoded.

Statistical analyses.

All statistical procedures were conducted by means of the software package SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), version 25. The sample is described based on several variables for which we calculated, among others, the mean and standard deviation. We investigated the relations among the variables by estimating correlations.

29 The mediating effect of (organizational-based) self-esteem and executive function was investigated based on the method of Baron and Kenny. This method assesses the association between the independent variable (i.e. ADHD) and dependent variables (i.e. job satisfaction, social competence at work and life satisfaction) while allowing to identify an indirect effect of the ‘mediator’ (i.e. (organizational-based) self-esteem and executive function). In order to speak of a mediating effect, there should be significant relationships between the independent and dependent variables and between the mediator and both independent and dependent variables, after controlling for possible confounding variables. When accounting for the mediator, the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable should weaken (i.e. partial mediation) or disappear (i.e. complete mediation). To explore the direct and indirect effects between independent and dependent variables, we performed linear regression analyses. Due to small sample size, we were unable to perform these analyses using PROCESS. For all analyses we employed a level of significance of 0.05. Results were perceived significant when p-values were smaller than the 0.05 cutoff. Control variables were taken into account during statistical analyses.

Measures

For the purpose of this study, we conducted quantitative survey research. The survey was distributed by means of online channels (cf. supra) and consisted of 148 questions. Since the data were simply collected at one point in time, they are cross-sectional of nature. Data collection furthermore happened anonymously. However, respondents had the opportunity to win a small reward for their participation. Participation in this lottery was voluntary. Respondents who wished to participate, were asked for their email address. This information was immediately deleted from the data set upon analysis, so it could never be linked to one’s responses.

Before the survey was distributed, we verified its comprehensibility in a small sample (n=5) of working-age individuals with different educational backgrounds and of which one was diagnosed with ADHD. Based on their input, we further optimized some minor item wordings and instructions in the survey.

30 Study variables.

Adult ADHD.

The Dutch version of Kessler et al.’s (2005) Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS-v1.1) was used to measure the degree of ADHD symptomatology. This measure consists of 18 items with each item being answered on a 5-point Likert-scale (0 = never, 4 = very often). Participants are requested to respond in reference to the past 6 months. By means of this self-report scale, a dimensional symptom rating for both inattentiveness and hyperactivity/impulsivity can be obtained. A sample item is ‘How often do you feel overactive and forced to do things as if you were powered by a motor?’ (in Dutch: Hoe

vaak voelt u zich overactief en gedwongen om dingen te doen, alsof u door een motor wordt aangedreven?’). The coefficient alpha of reliability for this scale in our study was

.95, indicating an excellent internal consistency which allowed us to calculate a sum score combining the items of the scale which could range from 0 to 72. The higher the score, the more ADHD symptoms one experiences.

Executive functioning.

The Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function – Adult version (BRIEF-A) was used as an estimate of executive functioning (Huizinga & Smidts, 2010). This self-report measure consists of 70 items which are rated on a 3-point scale (1 = never, 2 = occasionally, 3 = often). The Dutch version of the BRIEF-A includes 9 subscales: response inhibition, shift, emotion regulation, self-monitoring, initiate, working memory, planning and organizing, task monitoring, and organization of materials). In table 1 a brief description of each subscale is provided. The BRIEF-A yields an overall score, the Global Executive Composite (GEC). In addition, 2 index scores can be derived: the Behavioral Regulation Index (BRI) and the Metacognitive Index (MI) (Adler et al., 2013).

In addition to the 9 subscales, the BRIEF-A distinguishes an infrequency subscale which consists of 5 items. This scale indicates whether a respondent endorsed items in an atypical fashion relative to the combined normative and clinical samples. According to this scale, we indeed saw some “atypical” responses, but after further analyzing the items of the scale it appeared that most of these infrequent responses were given to an item that could be endorsed in a socially desirable manner.

31 The overall coefficient alpha of reliability of the BRIEF-A scale in our study was .99. The internal consistency of the scale is thus excellent, enabling us to calculate the Global Executive Composite (GEC). We calculated this score by simply summing all the 70 items for each participant (infrequency scale was not included in the total score). A higher scored indicated worse executive function.

Table 1

Description of BRIEF Scales

Scale name Number

of items

Description

Inhibition 8 Inhibitory control and impulsivity; ability to resist impulses and the ability to stop one’s own behavior

Shift 6 Ability to switch with ease from one situation, activity, or aspect of a problem to another as the circumstances demand

Emotion control 10 Ability to modulate and control one’s emotional responses

Self-monitor 6 Aspects of social or interpersonal awareness; degree to which one is aware of the effect that his behavior has on others

Initiate 8 Ability to start a task or activity and to independently generate ideas, responses, or problem-solving strategies

Working memory 8 Capacity to hold information in mind with the purpose of completing a task, encoding information or generating goals, plans, and sequential steps to achieving goals

Planning / organizing 10 Ability to manage current and future-oriented task demands

Task monitor 6 Ability to keep track of one’s problem-solving success or failure, and to identify and correct mistakes during action

Organization of materials 8 Orderliness of work, living and storage spaces

Global self-esteem.

The survey encompassed the Dutch version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) (Franck, De Raedt, Barbez, & Rosseel, 2008). It contains 10 items and serves as a global measure of self-esteem. Items are scored on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 (strongly

disagree) and 3 (strongly agree). A sample item is ‘In general, I am satisfied with myself’

(in Dutch: ‘Over het algemeen ben ik tevreden met mezelf’). The coefficient alpha of reliability for this scale in our study is .92. Hence, the internal consistency of the scale is