Does machine translation have an

impact on the perception of online

reviews?

AN EXPERIMENTAL STUDY

Word count: 17.442

Amaury Van Parys

Student number: 01604654Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Bernard De Clerck

A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Translation (Dutch – English – Spanish)

VERKLARING I.V.M. AUTEURSRECHT

De auteur en de promotor(en) geven de toelating deze studie als geheel voor consultatie beschikbaar te stellen voor persoonlijk gebruik. Elk ander gebruik valt onder de beperkingen van het auteursrecht, in het bijzonder met betrekking tot de verplichting de bron uitdrukkelijk te vermelden bij het aanhalen van gegevens uit deze studie.

PREAMBULE

Aan deze masterproef werd gedeeltelijk gewerkt tijdens de coronacrisis. Zoals de titel suggereert, gaan we in deze paper na wat de invloed is van automatische vertaling op de perceptie van online reviews. Daarvoor werd gebruikgemaakt van vier enquêtes. Voor de eerste drie versies hadden we al genoeg respondenten verzameld voor ons land in lockdown ging, maar de vierde survey moest nog worden verspreid. Dat bleek echter geen probleem te zijn, aangezien alle enquêtes digitaal werden afgenomen. Ook andere aspecten van het onderzoek hebben geen hinder ondervonden van de gevolgen van het coronavirus. We kunnen dus stellen dat de impact van deze gezondheidscrisis op het ontwikkelingsproces van deze masterproef vrij beperkt is gebleven.

Deze preambule werd in overleg tussen de student en de promotor opgesteld en door beiden goedgekeurd.

ABSTRACT

Online reviews have become a popular source of information that people consult to learn more about various products and services. Websites like Booking.com feature reviews written in a wide array of languages. To gain access to foreign language reviews, web users can rely on machine translation. In this context, it is interesting to examine whether this technology has an impact on review perception, especially when considering machine translation output is generally not as fluent as human-produced text. In this survey-based study, we investigate the impact of machine translation on credibility, reliability, professionality and other aspects of review perception by comparing (1) an error-free English review published on Booking.com, (2) a flawed Dutch automatic translation, (3) the same automatic translation presented as an original review and (4) an error-free post-edited version presented as an original review. This experimental set-up not only allows us to investigate the influence of machine translation, but also the impact of review language (English vs. Dutch). A total of 127 respondents provided usable data. Results show that the automatic translation is perceived more negatively than the original English version, but not more negatively than the Dutch post-edit. In addition, human-induced errors appear to be more harmful on perception than machine-human-induced errors. Finally, the impact of review language seems to be limited.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First and foremost, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my supervisor, Prof. Dr. Bernard De Clerck, who gave me a thorough introduction to the exciting world of academia over the course of the last two years. His guidance paved the way for the completion of both my Bachelor’s paper and my Master’s thesis. Mr. De Clerck helped me improve my academic writing skills, showed me how to successfully set up an experiment and taught me how to statistically analyse the results. He was always open to my suggestions and pushed me in the right direction when I was in doubt, giving me well-founded criticism and insightful advice. Unfortunately, our regular meetings could not continue after the outbreak of the coronavirus, but we managed to stay in touch via e-mail and Skype.

Of course, I should also thank my family and friends for their moral support these last few months. Writing this thesis was a challenging task, especially in the highly unusual circumstances we were all forced to live in due to the social distancing measures. Nonetheless, my relatives, friends and colleagues always encouraged me to keep going when I could not see the wood for the trees and helped me get my mind off things whenever I felt the need to take a break, either in real life or online.

Lastly, I want to thank all of our respondents for taking the time to fill out our survey. This thesis would obviously be incomplete without their help. A special mention goes out to the respondents who helped me spread the survey by sending it to others, ensuring that I could obtain the required response rate and saving me time and stress.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES ... 13

1 INTRODUCTION ... 15

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND ... 18

2.1 Electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) ... 18

2.1.1 The evolution from WOM to eWOM ... 18

2.1.2 The position of the online review ... 19

2.2 Machine translation ... 19

2.2.1 Types of machine translation ... 20

2.2.2 User perceptions of machine translation ... 22

2.3 Multilingualism on the Internet... 22

2.3.1 Review websites’ approach to foreign languages ... 23

2.3.2 Associations evoked by the English language ... 23

2.4 Review credibility ... 25

2.4.1 Information cues ... 25

2.4.2 Profile cues ... 27

2.4.3 Language proficiency ... 29

2.4.4 Additional factors: website reputation and hotel familiarity ... 30

2.4.5 Non-exhaustive overview ... 30

2.5 Hypotheses ... 32

3 METHODOLOGY ... 35

3.1 Design of the experiment ... 35

3.1.1 Selection of the vignette scenario ... 36

3.1.2 Stimuli ... 39

3.2 Participants and procedures ... 44

3.3 Measures ... 45

3.3.1 Constructs and semantic variables ... 46

3.3.2 Demographic variables and respondent features ... 48

3.3.3 Manipulation check ... 50 4 DATA ANALYSIS ... 51 4.1 Distribution analysis ... 51 4.2 Main effects ... 52 4.2.1 Original vs. MT ... 54 4.2.2 Post-edit vs. MT ... 56

4.2.3 Machine-induced errors vs. human-induced errors ... 58

4.2.5 Additional observations ... 62

4.3 A quick exploration of the other variables ... 63

4.3.1 Introduction ... 63

4.3.2 Analysis ... 64

5 DISCUSSION ... 66

5.1 Implications of the main findings ... 66

5.2 Validity of the measurement instruments ... 69

5.3 A note on homophily ... 70

6 CONCLUSION AND FURTHER RESEARCH ... 72

6.1 Conclusion ... 72

6.2 Limitations and suggestions for further research ... 74

BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 77

APPENDIX ... 82

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

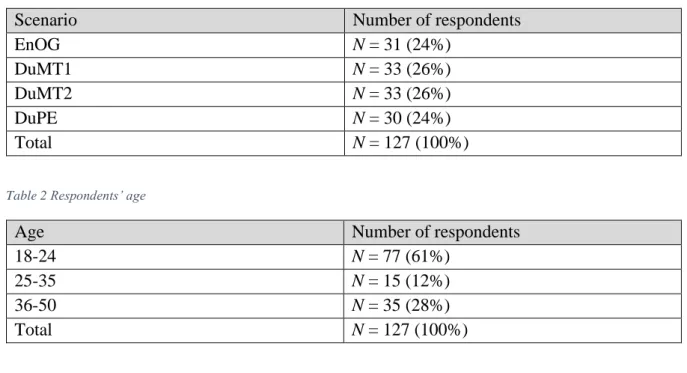

Table 1 Distribution of scenarios ... 44

Table 2 Respondents’ age ... 44

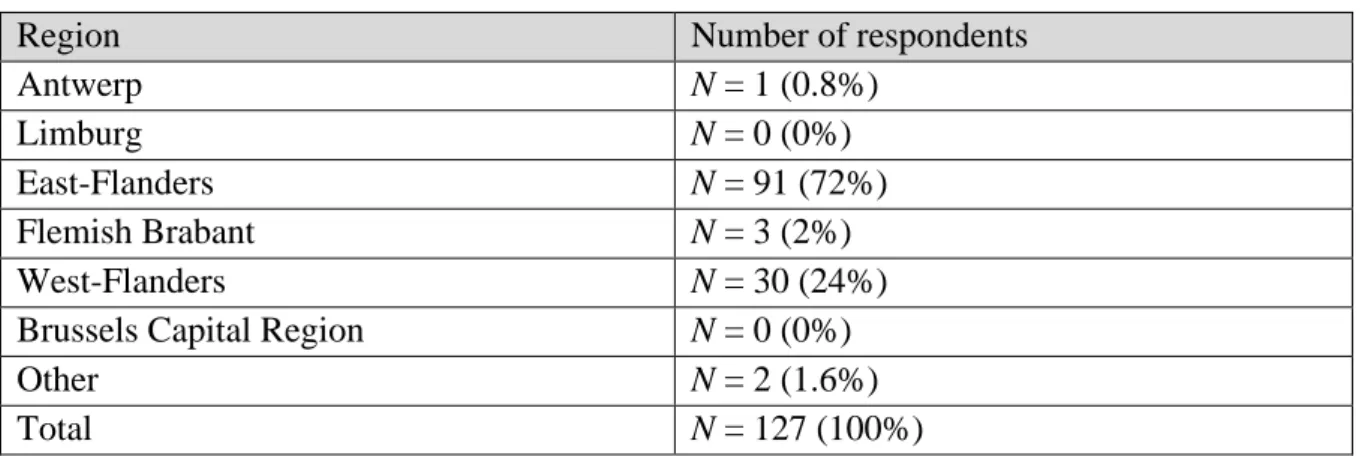

Table 3 Respondents’ region ... 45

Table 4 Respondents’ education ... 45

Table 5 Respondents currently enrolled in higher education ... 45

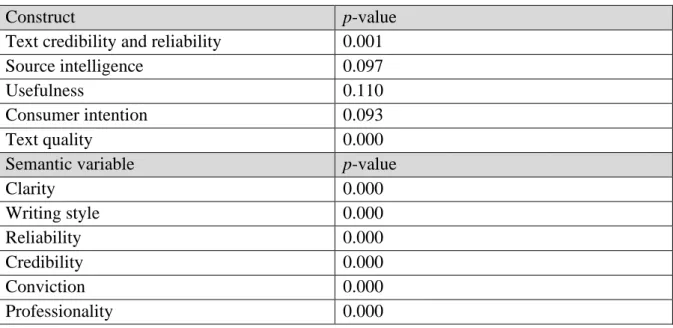

Table 6 Results Shapiro-Wilk test ... 52

Table 7 Results Mann-Whitney U test and t-test: EnOG-DuMT1 ... 54

Table 8 Construct means EnOG-DuMT1 ... 55

Table 9 Semantic variable means EnOG-DuMT1 ... 55

Table 10 Results Mann-Whitney U test and t-test: DuPE-DuMT1 ... 56

Table 11 Construct means DuPE-DuMT1 ... 57

Table 12 Semantic variable means DuPE-DuMT1 ... 57

Table 13 Results Mann-Whitney U test and t-test: DuMT1-DuMT2 ... 58

Table 14 Construct means DuMT1-DuMT2... 59

Table 15 Semantic variable means DuMT1-DuMT2 ... 59

Table 16 Results Mann-Whitney U test and t-test: EnOG-DuPE ... 60

Table 17 Construct means EnOG-DuPE... 61

Table 18 Semantic variable means EnOG-DuPE ... 61

Table 19 Results Mann-Whitney U test and t-test: EnOG-DuMT2 & DuPE-DuMT2 ... 62

Table 20 Construct means EnOG-DuMT2-DuPE ... 62

Table 21 Semantic variable means EnOG-DuMT2-DuPE ... 63

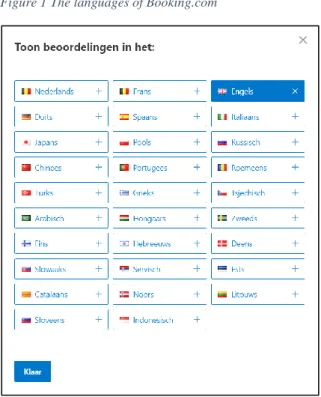

Figure 1 The languages of Booking.com ... 23

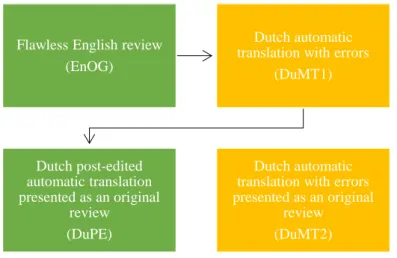

Figure 2 Process of creating the scenarios ... 36

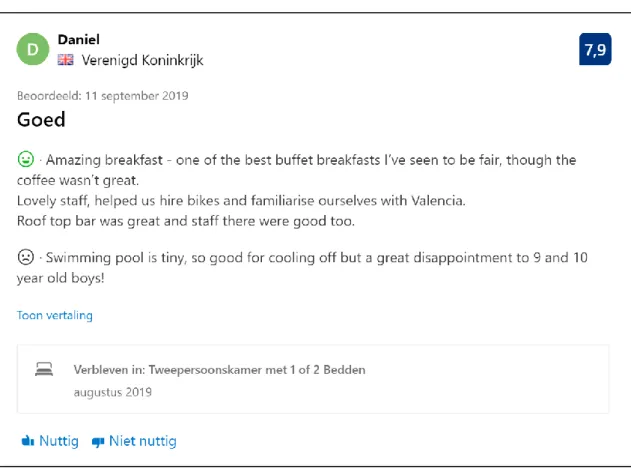

Figure 3 Original review retrieved from Booking.com ... 37

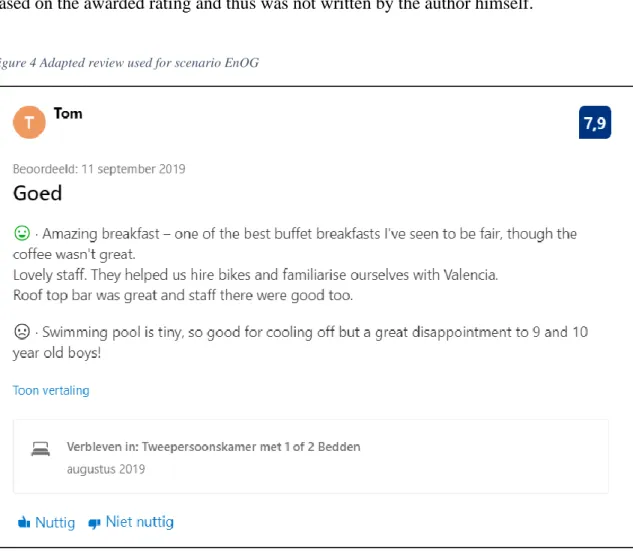

Figure 4 Adapted review used for scenario EnOG ... 40

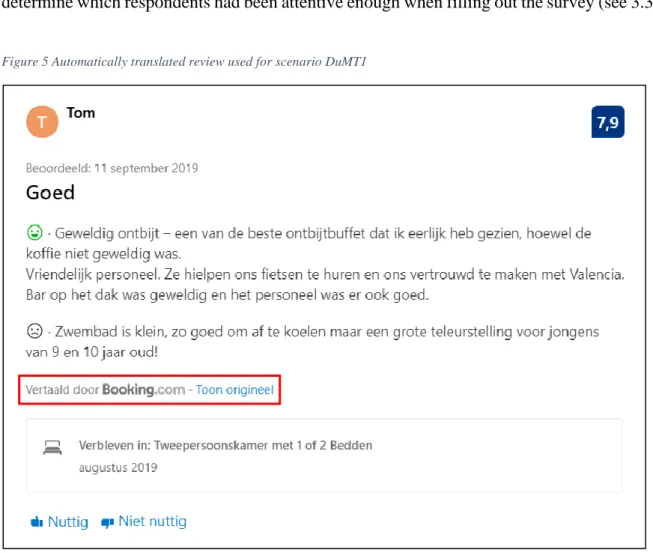

Figure 5 Automatically translated review used for scenario DuMT1 ... 41

Figure 6 Automatically translated review used for scenario DuMT2 ... 42

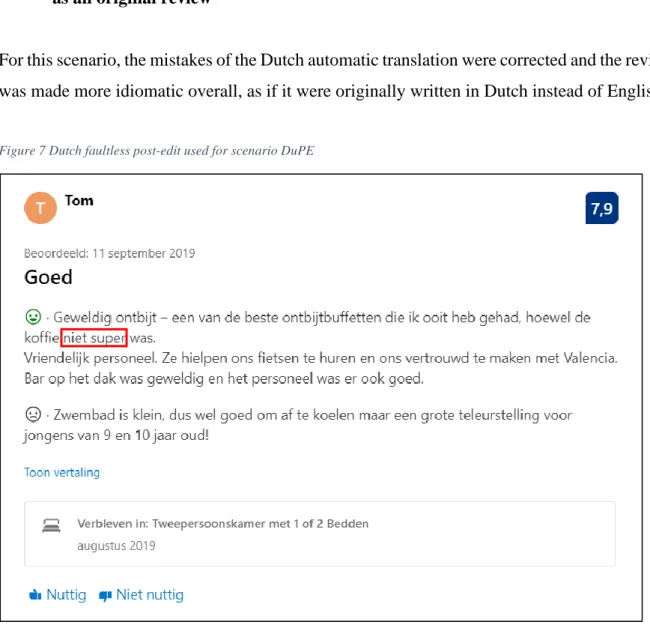

Figure 7 Dutch faultless post-edit used for scenario DuPE ... 43

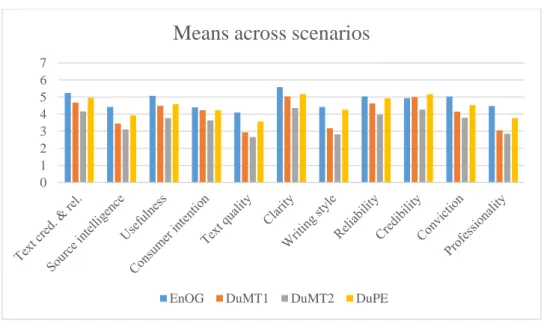

Figure 8 Means across scenarios... 53

Figure 9 Means EnOG-DuMT1 ... 54

Figure 10 Means DuPE-DuMT1 ... 56

Figure 11 Means DuMT1-DuMT2 ... 58

1 INTRODUCTION

In the globalized world we live in, online sharing of opinions and views has become very popular, leading to an avalanche of available information on different aspects of consumer goods and services on a wide range of review websites, with Booking.com and TripAdvisor as two of the more prototypical examples. At the same time, though, judging the credibility of online sources is becoming increasingly more difficult, most importantly due to their typically anonymous nature (Lee & Youn, 2009). Internet users often know virtually nothing about the reviewers on review websites, leaving them no choice but to base their judgement on other cues, including, but not limited to, profile picture, reviewer status and review valence (Xu, 2014). Never before have decisions depended so strongly on online reviews written by third parties that it has become imperative to investigate their credibility, in addition to other aspects of consumer perception. This paper aims to fill part of this research gap by examining an aspect in online reviewing that has hitherto been left underexplored: the effect of machine translation (MT) and the suboptimal quality of the target text as compared to 1) the original review, 2) the same review without any translation errors and 3) the same review with the translation errors presented as human-induced errors.

Machine translation is becoming increasingly more popular and many technological advances have been made in the field (Koponen, 2016). Many review websites, including Booking.com, give their users the option to automatically translate the reviews they want to engage with. However, it remains unclear how consumers perceive the quality of MT in an online environment. Does the quality of a flawed automatically translated review have an impact on reader perceptions (e.g. credibility, usefulness, professionality) as opposed to, for instance, the quality of the original review or the quality of a flawless review in the target language with the exact same content? Do machine-induced errors have the same effect as human-induced errors? In this paper, we aim to provide an answer to these questions by comparing a flawed Dutch machine-translated review to the English review it is based on and an error-free post-edited version presented as an original Dutch review, alongside a review with the same errors, though not presented as being induced by MT (see Section 3 for more information on how we did this). This study picks up on previous research conducted by Halsberghe (2018), Depovere (2018), Loete (2018) and Heirbaut (2019), who focussed on the effect of language errors on review credibility. However, rather than examining human-induced errors, we want to investigate the impact of errors induced by the limitations of MT in two settings (see Section 3): one in which

it is obvious that the errors are the result of MT and one in which the same errors are present without the MT framework (thereby suggesting that they are human-induced).

A second reason why we have chosen for the experimental set-up outlined above is that it allows us to examine the impact of review language on reader perceptions by comparing the original English review to the flawless Dutch post-edit (which is also presented as an original review; cf. supra). English is the most commonly used language on the World Wide Web (Bokor, 2018) and many reviewers, too, opt for English as the preferred language of choice to share their views and opinions with a target audience that is no longer restricted to speakers of the reviewer’s mother tongue. It could therefore be argued that due to the global appeal of the English language and the professional aura that may surround it, reviews may be seen as more credible or reliable. At the same time, Hale (2016) indicates that speakers of different languages perceive goods and services differently and it could therefore also be argued that readers who have a mother-tongue different from English prefer reviews written in their native language, presumably because they can identify more easily with the reviewer. We want to determine to what extent the same review elicits different perceptions depending on the language it is written in by comparing the two flawless reviews written in either English or Dutch. As the effect of review language on the perception of online reviews has not yet been investigated extensively, we hope this experimental set-up will allow some further insight.

The goals of this paper can be summarized in four research questions:

1. What is the effect of an automatically translated review with errors on perception as compared to the flawless English review it is based on?

2. What is the effect of an automatically translated review with errors on perception as compared to a flawless post-edit presented as an original Dutch review?

3. What is the effect of errors framed as the result of MT as compared to human-induced errors?

4. What is the influence of review language on perception (English vs. Dutch)?

The above-mentioned questions are answered based on the findings of an experiment set up to compare a set of four reviews, yielding (1) an original English error-free review, (2) the Dutch automatic translation presented as the product of MT, (3) the automatic translation without the MT context and (4) the Dutch error-free post-edited version presented as an original review. Each of these reviews report on the same hotel stay within a Booking.com web template.

The remainder of this thesis is structured as follows. First, a theoretical framework is provided in Section 2, which includes a discussion of online reviews as a genre and an introduction to machine translation, multilingualism on the Internet and the concept of review credibility. Furthermore, hypotheses to complement the four research questions are defined and substantiated. Section 3 elaborates upon the methodology of our experiment. The data are analysed in Section 4 and the results are discussed and compared in Section 5. Finally, the conclusions are presented in Section 6, in addition to suggestions for future investigation and some obvious limitations of this paper.

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

2.1 Electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM)

2.1.1 The evolution from WOM to eWOM

An important element in the decision-making process of consumers is word-of-mouth (WOM), i.e. ‘verbal consumer-to-consumer communication’ (Schindler & Bickart, 2005, p 35). As early as 1967, Arndt observed that exposure to favourable word-of-mouth causes an increase in consumers’ probability to purchase and vice versa. Especially people who are well-integrated in their social environment are susceptible to positive word-of-mouth, more so than less socially engaged people. With the rise of the Internet, a new type of WOM emerged that keeps gaining in popularity: electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) (Jeong & Jang, 2011).

It is essential that marketers understand the intricacies of eWOM communication in order to carry out a successful online marketing strategy (Park & Lee, 2009). Unlike traditional WOM, eWOM does not rely on physical cues and is text-based, which may negatively influence source credibility (Schindler & Bickart, 2005). What also sets eWOM apart from its predecessor is its frequently anonymous nature. In most eWOM situations, consumers can freely share their thoughts on certain products and experiences without having to reveal anything about their identity (Lee & Youn, 2009). In this regard, it is imperative to keep in mind that in both traditional and online consumer-to-consumer communication, the sender of a certain message will only influence the receiver’s attitude towards a product or an experience if the receiver trusts the sender (Xu, 2014). In traditional WOM, consumers learn about a product or an experience from an acquaintance with whom they have had past interaction, leading them to more easily accept the comments made. However, trust formation in most eWOM situations is more difficult, because, as stated above, eWOM communication often occurs anonymously. Due to a lack of past (real-life) interactions, web users will have to look for other cues to create an image of their online source, which will ultimately determine whether or not he or she is to be trusted. These credibility-related cues are further discussed in Section 2.4.

2.1.2 The position of the online review

Consumers can rely on a variety of different eWOM channels to search for product-related information in an online environment. However, online reviews may be considered the most prominent type of eWOM, as there is a growing need to share opinions on both products and services (Chen, Scott & Wang, 2011). Dickinger (2011) argues that user-generated content (UGC) is considered more trustworthy than say information distributed by mass media or official websites. As such, online reviews enable consumers to avoid negative products and experiences by improving their decision-making process overall (Filieri & McLeay, 2014). Research by Liu & Park (2015) has shown that consumers find online reviews especially useful when they are in the process of deciding whether to purchase an experiential product, such as a stay at a hotel or a restaurant visit. After all, assessing the quality of an intangible good is often not self-evident and reading others’ thoughts and comments may help consumers to visualize the experience and to form an opinion themselves.

A considerable number of the online reviews that are available to us fall into the category of travel reviews. The tourist industry has grown dramatically in recent decades1 and the

development of communication technologies and digital technologies in general has had a major influence on this expansion (Mariani, Baggio, Buhalis, & Longhi, 2014). Filieri, Alguezai & McLeay (2015) regard online travel reviews as a type of consumer-generated media that allows consumers to ‘bypass tour operators and agents’ (p 174-175). By consulting travel reviews, potential tourists can get in touch with a diverse group of consumers from a wide range of different cultural backgrounds. In this sense, it may be stated that the recent growth of tourist activities is partially due to the advent of review websites like Booking.com, which also further demonstrates the importance of the genre of online reviews as a whole.

2.2 Machine translation

Computing power keeps growing and so do the possibilities for machine translation. There is a wide range of computer-based tools that can help people to read and write texts in a foreign language (e.g. spellcheckers), but perhaps the most noticeable tool is web-based machine translation (Groves & Mundt, 2015). Examples of this technology not only include widely used

programmes like DeepL and Google Translate, but also translation tools designed specifically for certain websites. For instance, the integrated MT component of a travel website like Booking.com has more tourism-related data at its disposal than say Google Translate (Khalilov, 2017). The rising popularity of MT in recent years can be attributed to the technological advancements in the field, leading to an increase in available language pairs and improved quality of MT output (Koponen, 2016).

2.2.1 Types of machine translation

Daems & Macken (2019) define machine translation as the range of computer programmes that aim to translate text without human intervention. They regard machine translation as one of the most complicated domains in language technology. According to them, there are roughly three approaches to MT: rule-based systems (RBMT), statistical systems (SMT) and neural systems (NMT). In the case of rule-based MT, the earliest type of MT, dictionaries and grammar rules are used to create a set of linguistic data that allow the programme to understand a source text and to automatically transfer its meaning to the target language. Later, the statistical approach was adopted, which entails that extensive sets of both parallel and monolingual data are resorted to in order to train MT systems. A notable advantage with regards to the statistical approach is the fact that it can be used for any language combination as long as the necessary data are available. Despite these advancements, MT was still deemed incompetent by a considerable number of professional translators when SMT came into use due to the technology’s lack of real-world knowledge and contextual awareness (Doherty & Gaspari, 2013). As a response to the latter shortcoming, a new type of MT was developed: neural MT. What sets the neural approach apart from the purely statistical approach is that it includes an intrinsic encoder-decoder system which allows the programme to fully comprehend the linguistic context of the source text before generating the target text (OpenNMT, opennmt.net). Daems & Macken state that words in an NMT system are defined as vectors (or word embeddings), i.e. series of numbers in a multidimensional space. Semantically related words are positioned closely to one another in the vector space, whereas non-related words are not. These vectors can be regarded as semantic labels that allow the programme to interpret the statistical information it is based on more profoundly, which will ultimately cause a translation output of greater quality. In other words, NMT offers an important advantage in comparison to the previous two approaches, which led Google Translate, among other MT software

developers, to adopt the NMT approach. Given its position as most widely used MT method today, the automatically translated review investigated in this paper (i.e. scenario DuMT1, cf. infra) is the result of NMT. However, it should be noted that NMT is not perfect. While several grammatical issues from the other two approaches are resolved in NMT (e.g. problems with word order and congruence), there are still various other problems that are not. NMT output may at first glance look fluent and free from major mistakes, but it will often contain several inaccuracies (Nitzke, 2016). One of the problems typically associated with NMT according to Van Brussel, Tezcan & Macken (2018) is the higher possibility of semantically unrelated translations. In this regard, Daems & Macken (2019) mention the example of polysemic words, i.e. words with multiple meanings. The following is an example of an English polysemic word that was mistranslated by an NMT system (adopted from Van Brussel et al. (2018, p 3801)):

EN: … to build the first ever dynamic billboard to grace the streets of Glasgow. NL: … om het eerste dynamische billboard te bouwen om de straten van Glasgow te grazen.

Other issues addressed by Van Brussel et al. (2018) include the high recurrence of segments that should not have been translated (e.g. proper names) and the notion that 69% of accidental omissions do not get noticed in the post-editing stage. A substantial problem with regards to fluency and idiomaticity is the higher presence of unnecessary repetition in comparison to the source text. In addition to these issues, NMT can still produce several ungrammaticalities as well. In fact, the automatically translated review investigated in this paper contains errors that are grammatical in nature. An overview of these errors is provided in Section 3.1.2.

Although NMT is the most complex MT system to date and generally guarantees higher quality than RBMT and SMT, its outcome often is not perfect yet and human intervention is still necessary in most cases. The above-mentioned mistakes cited by Van Brussel et al. (2018) are specific to NMT and are usually difficult to comprehend or are easily overlooked (e.g. omissions, differences in meaning). Daems & Macken (2019) go on to posit that the entire NMT process is by no means transparent due to its reliance on word embeddings. Neural networks are completely based on numerical data, making it almost impossible to determine what went wrong exactly during the translation process.

2.2.2 User perceptions of machine translation

Martindale & Carpuat (2018) postulate that ‘while the overall quality of MT output is important, in practice the utility of MT also depends on the willingness of users to accept the technology’ (p 13). They emphasize the importance of trust and believe that it is an element of MT evaluation that has been wrongfully neglected: if users do not trust the MT tools that are available to them, they might be less likely to accept the translated message. Martindale & Carpuat conducted an experiment to determine how user trust is influenced by fluency (i.e. grammar, lexicon and style of a translation) and adequacy (i.e. the degree to which the original message is reflected in the target text). To this end, they created three scenarios: (1) a fluent and adequate translation, (2) a disfluent but adequate translation and (3) a so-called ‘misleading’ translation (i.e. fluent but inadequate). They discovered that respondents reacted more strongly to fluency errors than to adequacy errors and thus found the second translation – the disfluent yet adequate one – the least reliable. In other words, they attached more importance to a grammatically sound and idiomatic writing style than to the correct transfer of the message. Martindale & Carpuat therefore believe that developers of MT applications should pay extra attention to adequacy, fuelled by the finding that the respondents in their experiment seemed to place a high amount of trust in fluent, yet inadequately translated text. In this paper, we will examine whether the disfluency caused by an MT system leads to different perceptions when explicit reference to the technology is present as compared to a scenario where it is not.

2.3 Multilingualism on the Internet

During the Internet’s early years, digital content was almost exclusively produced in English, which meant that online multilingualism could not be investigated by scholars (Leppänen & Peuronen, 2012). Nowadays, the English language has lost its dominant position on the Internet and its hegemony has given way to language pluralism (Hale, 2016). This is reflected in, for instance, the wide range of languages offered on review websites. Nonetheless, English remains the preferred language for web content due to its global appeal, regardless of the rising popularity of other languages (Bokor, 2018).

2.3.1 Review websites’ approach to foreign languages

The influence of review language on the perception of online reviews has not been investigated to a great extent. However, research by Hale (2016) has shown that speakers of different languages assess products and experiences differently, which may also be reflected in ratings and reviews. He therefore argues that an average rating based on reviews in multiple languages could be deceptive and that reviews written in a language different from a reader’s mother tongue may lose their relevance.

Possibly as a reaction to this finding, Booking.com demotes foreign language reviews by letting them appear on separate pages, on which they are grouped per language. The reviews web users initially see are all written in their presumed native language. If they wish to consult reviews in another language, they have to navigate to a different page (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 The languages of Booking.com

2.3.2 Associations evoked by the English language

English is a lingua franca, a global language. The impact of the English language has been growing since the 19th century, but it rose considerably during the 1970s due to the United States’ position as a central economic power and the key technological achievements of Silicon

Valley (De Clerck, 2017). This also explains the initial hegemony of English on the Internet. In 2012, the European Commission conducted a survey to assess European citizens’ attitudes towards multilingualism (Eurobarometer 386). The results of this survey showed that 38% of Europeans claimed that they were capable of having a conversation in English, a figure which coincides with Belgium’s percentage at the time: also 38%. It may therefore be suggested that English is a widely understood language, especially across Europe.

As a considerable number of people is able to speak or at least understand English, it is often seen as the most neutral and inclusive language for online communication (Darics, De Clerck & Koller, 2019). Berezkina (2017, 2018) has found that the governments of Estonia and Norway have changed the presentation of their online content over the years, presumably with this idea in mind. Whereas originally, they aimed to offer a wide range of languages in response to the growing numbers of immigrants, their websites now only exist in a limited number of languages: the national language on the one hand and English on the other. In other words, Berezkina has revealed a linguistic homogenization of online content in the public sector.

The sense of neutrality that is attributed to English seems to be relied upon in advertising as well. The use of English is often considered a universal advertising technique (Kelly-Holmes, 2005; Kuppens, 2010; Gerritsen et al., 2007). As such, English slogans are frequently used in advertisements all over the world, e.g. Just do it2 or I’m lovin’ it3. In their theory of foreign

language display (FLD), Hornikx, Van Meurs & Hof (2013) claim that foreign languages evoke certain associations, which advertisers can use to their advantage to increase consumer consideration. In fact, the symbolic value that is attached to a foreign language message may be more impactful than the message itself. In this regard, Darics et al. (2019) refer to the slogan of German car manufacturer Volkswagen: Das Auto. They claim that it is not the meaning of the word that makes this slogan effective, i.e. the car, but rather the associations evoked by the German language. Each language evokes different associations. For instance, Hornikx, Van Meurs & Starren (2007) found that French tends to be associated with beauty and elegance, whereas German will often trigger associations of reliability and business. They believe these associations are frequently inspired by cultural stereotypes. However, English may be considered an exception to this tendency. After all, research suggests that in advertising

2 Nike (https://www.nike.com/be/nl) 3 McDonald’s (https://mcdonalds.be/nl)

contexts, English is generally not associated with English-speaking countries, such as the United Kingdom or the United States (Hartjes 2017; Hornikx, Van Meurs & Starren, 2005; Kelly-Holmes, 2005). Instead, the main association English evokes usually involves its status as a lingua franca and therefore its perceived sense of neutrality and inclusiveness. Possibly as a consequence, it may communicate the idea that an organization is modern, youthful and innovative, especially in the globalized world of today (Darics et al., 2019; Kuppens, 2010; Nortier, 2011). With this investigation, we aim to unravel whether the English language has a similar effect in an online reviewing context: is there a positive correlation between the use of English and a reviewer’s perceived credibility (among other aspects of review perception)?

2.4 Review credibility

Online reviews influence readers on different levels of perception, including perceived emotionality, professionality and intelligence, among others. However, one of the most important aspects in view of decision-making processes is perceived credibility. It is therefore of vital importance to provide an overview of what credibility entails and which aspects are involved in credibility assessments.

As mentioned above, credibility can suffer from the frequently anonymous nature of eWOM (Lee & Youn, 2009). In other words, readers are forced to trust reviewers based on a series of different characteristics specific to the review itself and its surroundings. In the following segment, several factors that are currently known to have an impact on review credibility are discussed and a non-exhaustive overview combining all of them is proposed (see 2.4.5).

2.4.1 Information cues

Cheung, Sia & Kuan (2012) describe four types of information cues that can impact review credibility, which vary across different levels of involvement and expertise. The central cue they present is argument quality, i.e. the ‘careful deliberation about the merits of the arguments presented’ (Cheung et al., 2012, p 621). They state that the higher the perceived quality of the arguments, the more credible a review becomes. However, other elements need to be taken into account when assessing review credibility as well – elements that are oriented towards the communication environment. Cheung et al. (2012) call these factors peripheral cues. The three

peripheral cues they identify are review consistency, review-sidedness and source credibility. Review consistency indicates to what extent the content of a review is consistent with the information presented in other reviews. Review-sidedness refers to either one-sidedness or two-sidedness. A one-sided review contains exclusively positive or exclusively negative arguments, whereas in a two-sided review, both positive and negative comments are made. Research by Jensen, Averbeck, Zhang and Wright (2013) suggests that two-sided reviews are more credible than their one-sided counterparts. They propose that ‘a small amount of negative information in an otherwise positive review appears to positively violate the expectations of reviewers’ (p 314). Lastly, source credibility is concerned with the credibility of an author and depends on more than the message itself. Ayeh, Au & Law (2013) describe it to have two dimensions: expertise, i.e. the extent to which an author is seen as a reliable source of information, and trustworthiness, i.e. the reader’s inclination to believe the presented information. Ismagilova, Slade, Rana & Dwivedi (2019) discern the same two characteristics and go on to posit that there is a third noteworthy aspect: homophily, which they describe as ‘the degree to which two or more individuals who interact are similar in certain attributes’ (p 3). They concluded that all three factors have a considerable influence on eWOM usefulness and credibility, but they regard homophily as the most crucial element, claiming that online consumers are naturally inclined to look for advice given by web users similar to them and therefore will find their content more credible – generally speaking. While not the main aim of this research, the potential impact of homophily will be indirectly assessed via a set of demographic variables, including gender, age and level of education (see 3.3.2).

A fifth type of information cue that Cheung et al. (2012) do not address directly is review valence, i.e. the polarity of a review (positive vs. negative). On average, exposure to online hotel reviews improves the probability for consumers to consider a stay at the reviewed hotel, no matter if the reviews are positive or negative (Vermeulen & Seegers, 2009). The mere fact that consumers are made more aware of a hotel’s existence appears to increase hotel consideration substantially. Still, it may be stated that review valence has a considerable effect on credibility. Kusumasondjaja, Shanka & Marchegiani (2012) probed into the impact of review polarity on travel consumers in relation to the reviewer’s identity and revealed that negative reviews are generally found to be more credible than positive reviews, especially when the reviewer is anonymous. Doh & Hwang (2009) even posit that a high number of positive reviews may actually damage the credibility of a certain company. In other words, a few negative messages will not critically harm an organisation if the majority of the available

information is positive. On a final note, it should be stated that the information cue ‘review polarity’ does not stand on its own and interacts with the other information cues, most notably review-sidedness. As established in the previous paragraph, the highest credibility rates are given to reviews that mention both positive and negative aspects, i.e. two-sided reviews (Jensen et al., 2013). The reviews discussed in this experiment are all two-sided, since we believe a neutral context is the best option for deducing the impact of machine translation and review language (see 3.1.1).

2.4.2 Profile cues

Profile cues can be described as the non-textual elements of a review that readers look for to reduce uncertainty about the reviewer. Although they do not constitute the review itself (i.e. the text written by the reviewer), they still determine its overall credibility to a considerable degree. Several studies (e.g. Park & Lee, 2009; Lim & Van Der Heide, 2014; Xu, 2014) have demonstrated the impact of profile cues on review credibility.

One of the first elements a reader will look for when judging the credibility of a reviewer is his or her profile picture. Xu (2014) found that the mere presence of a profile picture increases overall reviewer credibility. The specific impact may vary depending on the photo itself. This may be attributed to the so-called halo and horn effect, which was first described by psychologist Edward Thorndike as early as 1920. The term refers to a type of cognitive bias which entails that we tend to attribute positive or negative qualities to a person (or an object) based on only one characteristic (Cherry, 2020), in this case appearance of facial features. How someone’s physical appearance is perceived may thus partially determine how a review is evaluated. For this reason, we opted not to include a profile picture in this experiment, as its appreciation might skew the results – though it should be borne in mind that the absence of a profile picture may also trigger certain associations (see 3.1.1).

A reviewer’s gender may be another profile cue that can have repercussions for the reader’s decision-making process. Research by Depovere (2018) and Loete (2018) suggests that both men and women consider male reviewers to be more reliable, trustworthy and intelligent. In other words, male reviewers tend to be taken more seriously than their female counterparts. In a similar study conducted by Borghouts (2015), however, reviewer gender did not have the

same effect: both men and women preferred a reviewer of their own gender. It is therefore uncertain how reviewer gender influences online credibility. The influence of gender is further discussed in Section 3.3.2, in which we will elaborate upon the selection of a set of additional variables. Picking up on Depovere and Loete, another study was conducted to determine whether the effect on perception they demonstrated may also be attributed to reviewer name and the age associations it evokes (Van Parys, 2019). It was found that an author with a name that is common in the age category of 18 years or younger (e.g. ‘Lucas’) is considered less reliable than a reviewer who has a common name from the age group of 18-64. In other words, author name may increase or reduce credibility of an online review considerably based on age-related assumptions that may also impact perceived expertise and reliability.

According to Lim & Van Der Heide (2014) and Xu (2014), another impactful profile cue may be the author’s notoriety based on his or her number of ‘trusted members’ or friends, a factor which may in turn be related to the information cue ‘source credibility’ and its dimension of expertise (see also Cheung et al., 2012 and Ayeh et al., 2013; cf. supra). Xu found that this cue has a direct effect on perceived review credibility and influences both affective and cognitive trust dimensions. Lim & Van Der Heide suggest that the total number of reviews an author has posted is another element that may determine perceived notoriety. However, they also postulate that users and non-users of a review website may perceive a reviewer’s notoriety in different ways. They conducted an experiment to investigate the influence of website familiarity on review perception and concluded that people who are more familiar with the features of a website are more susceptible to be influenced by an author’s total number of friends and total number of previously written reviews. At the same time, non-users frequently do not notice these two profile cues or simply do not grant them any meaning, which implies that they cannot be influenced by them. In reaction to these findings, we included website familiarity as an additional variable in our experiment by asking the respondents to indicate whether they are familiar with the website we wish to investigate (i.e. Booking.com). On a final and more general note, it is also worth mentioning that we attempted to keep the influence of all potential profile cues as stable as possible (see 3.1.1 for more information on how we did this).

2.4.3 Language proficiency

Several studies have demonstrated that language proficiency can have a considerable effect on reader perceptions. The absence of grammatical errors (e.g. conjugational errors, d/t-errors, spelling mistakes) positively affects text appreciation (Jansen, 2010) and perceived author intelligence (Schloneger, 2016). This is no different with respect to online reviews, both with positive polarity (Heirbaut, 2019; Maesschalck, 2015) and negative polarity (Depovere, 2018; Halsberghe, 2018; Loete, 2018). In fact, the presence of ungrammaticalities has been shown to negatively impact a variety of different review-related aspects. Heirbaut (2019), for instance, concluded that one of the most severely affected factors within the context of online reviews is source intelligence. It is uncertain, however, whether machine-induced errors have the same effect as human-induced errors, as many people are aware of the limitations of MT and may therefore be more forgiving towards the mistakes it generates. Moreover, MT errors are often different in nature. As mentioned above, the most recently developed systems (i.e. neural MT systems) generally succeed in producing fluent, grammatically correct sentences, but sometimes fail to accurately transfer the meaning of the source segment, resulting in a potentially non-sensical translation (Daems & Macken, 2019; see 2.2). Nonetheless, MT may still produce ungrammatical constructions as well, as is exemplified by the automatic translation evaluated in this experiment (see 3.1.2).

Another aspect that needs mention to complete this overview – though less relevant for this paper – is the use of tussentaal, i.e. the Flemish intermediate variant between Dutch standard language and regional dialects. This is an additional language-related element that has been demonstrated to negatively affect reader perceptions (Depovere, 2018; Halsberghe, 2018; Heirbaut, 2019; Loete, 2018).

Whereas the negative correlation between the presence of language errors and review perception is clear, it is worth noting that online language (including the language in online reviews) may also contain other elements or patterns that diverge from standard language in different respects, the impact of which is less clear in terms of credibility assessment. In the literature, these features are often referred to as netspeak (i.e. ‘the set of peculiar discourse features identified in computer-mediated communication’, Barton & Lee, 2013, p 5) and include, for instance, a more economical approach to language use (e.g. dropping articles or

auxiliaries, cf. ‘the pool wasn’t great’) and more expressive language through pragmatic lengthening (as in ‘cooool’) and capitalization (as in ‘COOL’).

2.4.4 Additional factors: website reputation and hotel familiarity

A review’s credibility is not solely determined by information cues, profile cues and the author’s language proficiency. To provide an overview that is as comprehensive as possible, it is imperative to discuss two additional factors: website reputation and hotel familiarity.

Park & Lee (2009) discovered that a website’s reputation (established vs. unestablished) has a considerable impact on a review’s credibility. They conducted an experiment in which they concluded that the more reputable a review website is, the more inclined consumers will be to take its reviews into consideration. This is especially the case with respect to reviews discussing experience goods. In this regard, it should be noted that the reader perceptions of the reviews investigated in this paper may be influenced by the Booking.com web template we resorted to, as Booking.com is a well-established review website (see 3.1.1).

In the context of hotel reviews, review credibility may also be influenced by hotel familiarity. According to Vermeulen & Seegers (2009), there is a positive correlation between hotel familiarity and consumer consideration of hotel reviews. If the reader is familiar with the hotel in question, the author will come across as more credible. This factor cannot exert influence in our experiment, however, as the reviewer does not mention the name of the reviewed hotel.

2.4.5 Non-exhaustive overview

All the credibility-inducing factors discussed in this section can be summarized in the non-exhaustive overview presented on the following page. ‘Review valence’ can be considered an information cue, but it is included separately as we wanted to maintain the typology proposed by Cheung et al. (2012). We suggest that review language and the presence of errors which are presented as the outcome of MT may be two other influential factors, the effects of which we aim to study in this paper. Our investigation will determine whether these language-related aspects should be added to this overview.

• Review valence (Kusumasondjaja et al., 2012; Vermeulen & Seegers, 2009) • Information cues (Cheung et al., 2012)

o Argument quality

o Source credibility (reviewer status in Xu’s typology from 2014)

▪ Expertise (Ismagilova et al., 2019; Vermeulen & Seegers, 2009) ▪ Trustworthiness (Ismagilova et al., 2019)

▪ Homophily (Ismagilova et al., 2019) o Review consistency

o Review-sidedness

• Profile cues (partially determined by website familiarity; see Lim & Van Der Heide, 2014) o Profile picture (Xu, 2014)

o Author gender (Depovere, 2018; Loete, 2018) o Author name and age associations (Van Parys, 2019)

o Number of friends/trusted members (Lim & Van Der Heide, 2014; Xu, 2014) o Number of previously written reviews (Lim & Van Der Heide, 2014)

• Language proficiency

o Tussentaal (Depovere, 2018; Halsberghe, 2018; Heirbaut, 2019; Loete, 2018) o Expressive language through pragmatic lengthening and capitalization

(Halsberghe, 2018; Van Parys, 2019)

o Human-induced errors (Depovere, 2018; Halsberghe, 2018; Heirbaut, 2019; Loete, 2018)

o (MT errors within an MT context) • Website reputation (Park & Lee, 2009)

• Hotel familiarity (Vermeulen & Seegers, 2009) • (Review language: English vs. Dutch)

2.5 Hypotheses

Based on the findings of previous studies, hypotheses to complement the four research questions can be formulated.

1. What is the effect of an automatically translated review with errors on perception as compared to the flawless English review it is based on?

2. What is the effect of an automatically translated review with errors on perception as compared to a flawless post-edit presented as an original Dutch review?

Following Martindale & Carpuat’s (2018) findings on fluency errors (i.e. grammatical, lexical or stylistic errors) resulting from the restrictions of MT, we will postulate that consumer perception of online reviews will be negatively impacted by them. This is further supported by numerous studies illustrating the negative influence of human-induced language errors on review perception (e.g. Heirbaut, 2019; Maesschalck, 2015). It should be noted, however, that the degree to which MT errors have a negative effect may be different (see also Hypothesis 3).

Hypothesis 1: Automatically translated online reviews containing MT errors will negatively

affect perceptions as compared to the error-free original.

Hypothesis 2: Automatically translated online reviews containing MT errors will negatively

affect perceptions as compared to the error-free version in the same language.

3. What is the effect of errors framed as the result of MT as compared to human-induced errors?

As mentioned above, various studies have shown that human-induced language errors negatively influence review perception (e.g. Heirbaut, 2019; Maesschalck, 2015). Although MT outcome may contain language errors as well (Daems & Macken, 2019; Nitzke, 2016; Van Brussel et al. 2018), we believe that many web users are aware of the limitations of automatic translation – perhaps due to the ever-increasing presence of this technology today. They may therefore conclude that the original author of an automatically translated text is not responsible for potential ungrammaticalities or unidiomatic constructions, meaning that perceived source intelligence and consequently several other aspects of review perception might not be negatively affected. Furthermore, readers will often rely on MT when they do not master the

original language a particular text is written in. MT technology allows them to gain access to information that would otherwise be unavailable to them, which may be accompanied by a sense of forgiveness towards potential errors. At the same time, readers may be less forgiving if the review is written in a language that they do speak, resulting in lower levels of perceived credibility, professionality, conviction etc. In such a scenario, potential errors may be attributed to the reviewer’s sloppiness, imperfect writing style or lower language proficiency. Possibly, the reviewer is seen as a non-native speaker, which in turn may lead to a lower assessment fuelled by racism.

Hypothesis 3: Language errors have a lower negative impact when they are presented as the

outcome of machine translation, rather than the direct result of a reviewer’s writing process.

4. What is the influence of review language on perception (English vs. Dutch)?

Although reviews that are not written in a reader’s mother tongue may lose their relevance (Hale, 2016), English is often considered to be the most neutral and inclusive language for online communication (Darics et al., 2019). Research suggests that advertisements may benefit from the use of English due to its global appeal and its subsequent sense of neutrality (De Clerck, 2017; Hartjes, 2017; Kelly-Holmes, 2005). Dutch-speaking readers might be more susceptible to believe the comments made in an English review due to similar associations. We also propose that an English-speaking author may be perceived more positively as a consequence of the additional cultural insights he or she provides, in addition to the already existing intracultural perceptions in the minds of the readers, leading to a more objectified representation. In case the reviewer is seen as a non-native, his or her multilingual status may also have a positive effect on expert status and hence content-related aspects such as credibility, reliability and professionality4.

Nonetheless, we must emphasize that we only assume this will be the case in the particular setting we are investigating, as we believe that readers’ attitudes towards a review’s language may also depend on the reviewed location. One might presume that an English-language review

4 It should be noted, though, that neither the Brits nor the Americans have a very high status as refined connoisseurs

discussing an English-speaking location will be seen as more credible than a Dutch version and vice versa. As such, a Dutch review about a Flemish town like Ghent may be more impactful than an English review on the same topic. In our scenarios, however, the reviewer either writes in English or in Dutch, which implies that in both cases, he has no connection with the location (i.e. Valencia) or its official languages (i.e. Spanish or Valencian).

Hypothesis 4: Review language impacts the perception of online reviews in this particular

setting. An English review will be more impactful than a Dutch review due to the global appeal of the English language.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Design of the experiment

To assess whether machine translation and review language have an impact on reader perceptions of an online review, a between-subjects experimental factorial design was set up. There were four groups of respondents and each group was exposed to one of the four possible scenarios, i.e. they filled in one of the four corresponding surveys created for this experiment. 2 x 1 comparisons will be made across scenarios for the different groups of respondents based on language (English vs. Dutch), errors (presence vs. absence) and MT context (presence vs. absence). The following four scenarios were assessed:

• EnOG: a faultless English review written by a native speaker

• DuMT1: the automatically translated Dutch version with errors and an explicit

reference to MT via the ‘Translated by Booking.com’ message

• DuMT2: the same automatic translation presented as an original review (i.e.

without the ‘Translated by Booking.com’ message)

• DuPE: the manually post-edited faultless Dutch automatic translation, also

presented as an original review

For the first Dutch scenario (DuMT1), we worked with an unedited automatically translated review as produced by the Booking.com translation tool, including translation-induced errors and unidiomatic expressions. Via the instructions accompanying the experiment and a stimulus in the message template mimicked from the Booking.com website (i.e. the message ‘Translated by Booking.com’), respondents knew that they were dealing with an automatically translated version. We worked with the same translated review for the second Dutch scenario (DuMT2), but we left out the ‘Translated by Booking.com’ trigger, exposing respondents to a review that contains mistakes, though without the MT setting. For the final scenario (DuPE), the automatic translation was post-edited, resulting in a faultless Dutch text which was also presented as an original review. The process of creating the four scenarios is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Process of creating the scenarios

3.1.1 Selection of the vignette scenario

To maximize recognisability and empathy, we chose a review of a popular city-trip destination (Valencia) and a set of review topics that frequently recur in hotel reviews (e.g. size of the pool, rooms, breakfast service). Studies have shown that information cues, profile cues, language proficiency, website reputation and hotel familiarity can exert considerable influence on perceived credibility (see 2.4). The impact of these factors was kept as stable as possible across scenarios in various ways. For reasons of clarity, the review that was selected to serve as the basis for this experiment is presented below (see Figure 3).

Flawless English review (EnOG)

Dutch automatic translation with errors

(DuMT1) Dutch post-edited automatic translation presented as an original review (DuPE) Dutch automatic translation with errors presented as an original

review (DuMT2)

Figure 3 Original review retrieved from Booking.com

A first factor that was ruled out is hotel familiarity, since the respondents did not know which hotel the reviewer is describing. The review is balanced and is written in a way that is neither too overtly negative, nor too excessively positive. Within the scope of Cheung et al.’s information cues (2012), the review may be described as two-sided. The choice to select a review of this type is fuelled by research on online credibility which has found that highest credibility rates are given to balanced reviews that are not ‘extreme’ in the ways the views are presented (Jensen et al., 2013). If the intention is to test the impact of automatic translation and review language on aspects of review perception, we assume a more neutral context to be the best option for manipulation. The arguments themselves are well thought-out, as the writer bases his ideas on the experience itself. For instance, he refers to the so-called ‘amazing’ breakfast and the helpful staff. This implies that the information cue ‘argument quality’ is on a par with what a reader might expect from a respected review website like Booking.com.

The respondents were not able to access the reviewer’s profile and thus could not judge his competence by reading any of his previously written work. This minimizes the impact of perceived expert status, a factor which is related to the information cue ‘source credibility’ (Cheung et al., 2012). On a similar note, there are no other reviews available on the same topic

for the respondents to consider, which rules out the influence of the information cue ‘review consistency’. Instead, they were asked to judge a review that stands in isolation, a task which may be deemed unnatural. In a non-simulated environment, readers have a variety of reviews to take into consideration and not just one. Furthermore, the respondents of the scenario with the automatic translation that is presented as MT outcome (i.e. scenario DuMT1) did not click on the translation button themselves, but were asked to judge a predetermined review instead. In a more realistic setting, they would be presented with the original English review and would then decide for themselves whether they want to see the automatically translated version. This particular setting may have an impact on the respondents’ answers, as it does not fully represent the stages they go through in genuine review contexts.

Influence of profile cues, as put forward by Lim & Van Der Heide (2014), has also been kept stable as much as possible. To avoid any cultural associations and stereotypes that could affect overall perceptions, we decided to leave out the reviewer’s nationality. After all, the aim of this paper is not to investigate the influence of stereotypes, but the effect of machine translation and review language. The reviewer’s name was replaced for two reasons. On the one hand, ‘Daniel’ (without dieresis) may trigger associations with British names and thus cultural stereotypes. On the other hand, the Dutch equivalent ‘Daniël’ (with dieresis) might evoke age associations, which have been shown to impact perceived credibility (Van Parys, 2019). According to Flanders’ population register5 of 2019, the Dutch equivalent ‘Daniël’ (with

dieresis) is a common name among men who are 65 or older. The respondents might therefore assume that the reviewer pertains to that age group, which may in turn influence their attitude towards the review. After further consulting the register, we decided to use the name ‘Tom’ instead, a common name in most age groups in both Belgium (and the UK). Therefore, the results of the experiment cannot be attributed to age associations evoked by author name.

Although Booking.com offers its users the possibility to upload a profile picture, we opted to use Booking.com’s standard image for members who do not wish to use a photo, i.e. the initial of the reviewer’s name. As such, we avoided the possible impact of the aforementioned halo and horn effect based on a positive or negative appreciation of facial features and appearance (Thorndike, 1920; Cherry, 2020). Furthermore, the majority of Booking.com users choose not to use a profile picture, which makes the reviewer in this experiment no exception. The absence

of a profile picture may also influence reader perceptions, but the potential impact of this specific profile characteristic is stable across all four scenarios and there is no reason to assume that certain respondent groups will have stronger bias towards the initial than others.

On a final note, it should be borne in mind that the Booking.com lay-out we simulated is in itself an element that may influence reader perceptions. Booking.com is a respected review website and describes itself as ‘one of the world’s leading digital travel companies’ (Booking.com, 2020), which may trigger certain expectations regarding text quality. After all, Park & Lee (2009) have demonstrated that the eWOM effect is greater on established websites (see 2.4.4). However, as this trigger is constant across all scenarios, we expect the impact to be stable, although it does mean that templates of other review websites may yield different averages for the same manipulations with the scenarios. In other words, a replication of this study in a TripAdvisor context, for instance, may yield different results due to potentially different context associations. In this respect, it should also be noted that the automatic translations may be different, as the data used to train MT models vary from website to website (Khalilov, 2017).

3.1.2 Stimuli

This section gives an overview of the four scenarios and elaborates upon the methods used to create them. Errors in the machine translation output and the way we resolved them in the post-editing stage are discussed in detail.

• Scenario EnOG: a faultless English review written by a native speaker

As the versions of the review that are not the direct outcome of automatic translation could not contain any errors, we made one grammatical change to the original review for this scenario. The second sentence had to be reformulated, as the verb ‘helped’ does not have a subject and can thus be considered ungrammatical. The resulting construction splits the original sentence into two separate ones, providing the finite verb with a subject. We should also indicate that

the Dutch title ‘Goed’ was kept, as it is a general indication of quality provided by Booking.com based on the awarded rating and thus was not written by the author himself.

Figure 4 Adapted review used for scenario EnOG

It should be noted that we maintained elements that may be associated with netspeak, i.e. the set of specific linguistic features typically used in an online environment (Barton & Lee, 2013). As such, ‘roof top bar’ and ‘swimming pool’ are not preceded by an article and ‘lovely staff’ is presented as a sentence, although it is a noun phrase and thus does not contain a verb. While these omissions may be regarded as ungrammatical in the strict sense of the word, their substantially high frequency in online reviews may yield them a status as typical features of the genre. We therefore propose that in this online scenario, they are justified and add to the overall review experience.

• Scenario DuMT1: the Dutch automatic translation with errors and an MT frame The review was automatically translated to Dutch using Booking.com’s translation component. It is based on the neural approach to MT (Khalilov, 2017), which means that, similar to the

statistical approach, the model is trained on a considerable amount of parallel data. The instructions of our survey informed the respondents that the text was an automatic translation. They could also deduce this from the message directly below the review, stating that it was ‘Translated by Booking.com’. The message is highlighted in red in the screenshot below. We added the manipulation check question ‘Was this review an automatic translation?’ to determine which respondents had been attentive enough when filling out the survey (see 3.3.3).

Figure 5 Automatically translated review used for scenario DuMT1

The automatic translation contains several errors. The first error is grammatical in nature and concerns the use of the singular noun ‘ontbijtbuffet’ where a plural is needed. ‘One of the’ appears to be a problematic construction to translate for the Booking.com translation component. As is the case with its English counterpart, the Dutch ‘een van de’ must be followed by a plural noun, which is not the case in the machine-translated text. Consequently, the subsequent relative pronoun ‘dat’ should be changed to its plural form ‘die’. Another error is the misinterpretation of the English word ‘so’ in the final sentence. In the original review, it functions as a conjunction that expresses consequence. However, the MT system regards it as a premodifier of the adjective ‘good’, which is reflected in the Dutch output. This is a typical

example of a semantically unrelated translation caused by a polysemous word (‘so’). As mentioned above, polysemy is one of the factors that cause NMT systems to misinterpret the meaning of a source segment (Daems & Macken, 2019). A similar issue may be observed in the example we adopted from Van Brussel et al. (2019) on p 21.

• Scenario DuMT2: the Dutch automatic translation presented as an original review The vignette from the previous scenario was used for this scenario as well, the only difference being that the translation message is not present. In other words, the text is presented as if it were originally written in Dutch and the imperfect writing style may be seen as a consequence of the reviewer’s sloppiness, imperfect writing style or lower proficiency.

Figure 6 Automatically translated review used for scenario DuMT2

We decided to include this particular scenario to determine whether language mistakes that cannot be traced to MT (and thus will be presumed to be human-induced) are judged differently by readers than errors that are presented as inaccuracies of MT outcome (cf. the third research

question). A comparison between the results of this scenario and the results of the previous scenario (i.e. DuMT1) will allow us to do so (see Section 4).

• Scenario DuPE: the faultless post-edited Dutch automatic translation presented as an original review

For this scenario, the mistakes of the Dutch automatic translation were corrected and the review was made more idiomatic overall, as if it were originally written in Dutch instead of English.

Figure 7 Dutch faultless post-edit used for scenario DuPE

The above-mentioned errors were resolved, i.e. the singular ‘ontbijtbuffet’ and the misinterpretation of ‘so’. We also opted to change one additional (lexical) element. The author of the original review uses two different adjectives in the first sentence (‘amazing’ and ‘great’), but both were automatically translated as ‘geweldig’. We therefore chose to describe the coffee as ‘(niet) super’ instead of ‘(niet) geweldig’ (note the highlighted words in the picture above). We made this choice in an attempt to create a more idiomatic and fluent text and to reflect the writing style of the source text as accurately as possible.

In concordance with the original English version, netspeak features were kept to make the review seem more authentic and natural. For this reason, we did not add articles to ‘bar op het dak’ and ‘zwembad’ and we maintained the elliptical sentence ‘vriendelijk personeel’.

3.2 Participants and procedures

The survey (see 3.3) was distributed online – no physical copies were used. E-mail, Facebook

Messenger and, to a lesser extent, WhatsApp were used to ask potential respondents to

participate. A link to one of the four versions of the survey was then sent to those willing to cooperate. Background information in the informed consent was basic so as not to influence responses and was restricted to framing the survey as a UGhent-based investigation into communication on review websites.

A total number of 140 respondents filled out the questionnaire. After filtering out wrong answers to the attention check and the manipulation check6, we retained 127 respondents, of whom 48 identified as male (38%) and 79 as female (62%). This experiment was aimed at the demographic of people aged between eighteen and fifty years old. 81% of the respondents indicated familiarity with Booking.com. Tables 1-5 refer to the distribution of the scenarios and the respondents’ age, region and type of education.

Table 1 Distribution of scenarios

Scenario Number of respondents

EnOG N = 31 (24%)

DuMT1 N = 33 (26%)

DuMT2 N = 33 (26%)

DuPE N = 30 (24%)

Total N = 127 (100%)

Table 2 Respondents’ age

Age Number of respondents

18-24 N = 77 (61%)

25-35 N = 15 (12%)

36-50 N = 35 (28%)

Total N = 127 (100%)