platform for the blue park

Designing product-service systems: a boat sharing

Academic year 2019-2020

Master of Science in de industriële wetenschappen: industrieel ontwerpen Master's dissertation submitted in order to obtain the academic degree of

(Eurometropolis)

Supervisors: Dr. Francesca Ostuzzi, mevr. Catherine Christiaens

Student number: 01605209

2

3

The author gives permission to make this master dissertation available for consultation and to copy parts of this master dissertation for personal use.

In all cases of other use, the copyright terms have to be respected, in particular with regard to the obligation to state explicitly the source when quoting results from this master dissertation.

4

Preamble

The 13th of March, measures were taken by the Belgian Federal government in response to the rising cases of

Covid-19, limiting all non-essential movements. The situation made it unjustifiable to have physical contacts with others or even cross national borders and thus had some impacts on this thesis.

The initial goal of this work was to see how a boat sharing system could help battle pollution at the waterways of the Blauwe Ruit, the region of interest shaped by the rivers the Leie, the Deûle and two canals

entering the Schelde. The idea was to set up this system between two points along one of the streams outlining this area, execute a test for several weeks, analyse if this would have a positive impact and improve flaws brought up by the test.

First off, the continuation of a set of observations around the Blue Park had to be cancelled. These were meant to confirm the need and possibility (i.e. a testing location) to clean the waters at the Blauwe Ruit, but the

early results gathered became – statistically speaking – irrelevant due to the small amount of data gathered. Secondly, the locations considered for a possible setup were suddenly unreachable, due to the restrictions on non-essential movements – at that moment still in force – which made it nearly impossible to compare those locations, let alone construct an installation for the system test.

A change in focus of the thesis seemed appropriate, as physical testing would not be possible anytime soon. In consultation with the internal promoter, the focus would shift to designing the sharing aspect, whereas the cleaning of the local environment would be considered a conceivable, positive implementation. The

consequence of this, however, was that the project was thrown back from the testing phase to the research phase, and time ran eventually short.

5

Acknowledgements

Without the support of various people, the result of this thesis wouldn’t have been nearly as good as what is presented here. I would like to thank these magnificent individuals here.

First of all, my promoters, Francesca Ostuzzi, Marnix Rummens and Catherine Christiaens for presenting the opportunity to get my hands dirty in this challenging subject and the unrelenting belief in a successful

outcome.

Marnix and the team behind Buda vzw put great effort in helping me out with the logistics, materials, space, muscles and brains required to set up the test in December, to carry out a great brainstorm session and bring me in contact with others. Marnix’ creativity knows no borders, to the point where he could have done the whole boat sharing system all by himself, if he wouldn’t have been busy with so many other things.

Francesca always knows what to do, keeps you on track, supports you in the inevitable moments of distress (or the ‘dark night of the soul’, as she would jokingly say) and is always open for conversation – even postponing her lunch break in urgent situations. After a consultation, you could have been criticised on your work on different levels, and still, you would walk away with a smile. She guides the project with genuine concern in the wellbeing of her master students and that of the project. She understands you. Do I need to say more? I could not have wished for a better promoter and I’m sure many other students agree.

I cannot be more grateful for Catherine and her colleagues from the Eurometropole Lille-Kortrijk-Tournai, who took up the task of external promoter and thus worked out the problem of the sudden absence of a promoter at the end of the first semester. I will forever appreciate Catherine’s support before and during the Corona-period, responding to my mails with utter enthusiasm. Despite the increased workload and amount of online meetings she experienced, Catherine would always remain herself during chats, and that alone could make my day.

A big thank you to Ben and Tobias for the support during the circular bootcamp. The ideas and enthusiasm provided there were the jump-start I needed to fully go for the project. Without the persuasion and design skills of Tobias or without the focus and encouragement of Ben, the results of those four days wouldn’t have been half as interesting, looking back on it now.

Of course I would like to thank Diederik Cordonni and his team too, who did a fantastic job organising the bootcamp mentioned before. I would gladly participate again next time!

The participants of the brainstorm session and the co-design sessions: in particular Danny Raveau, for sharing his experiences as a kayaker, his open-minded spirit and the patience exercised when lending his kayak and other material to me. The same is true for Jolle Desloover and his watercycles.

6

Abstract [EN]:

Designing product-service systems: a boat sharing

platform for the Blue Park

On different locations spread over Europe, numerous neglected boats can be found, unable to

find a new home, although they could be reused given some maintenance. To avoid such

situations, this thesis offers a more sustainable alternative: a sharing platform where small,

non-motorized boats like kayaks and canoes are shared among its users to stimulate boat

owners to maintain their property again.

Sharing existing boats instead of purchasing new vehicles is an example of how

product-service-systems can have a positive impact on the ecological level and where the focus lies on

satisfaction rather than the product itself. The sharing economy understood this message and

offers since several years services that can be considered advantageous to both providers and

users and where assets such as cars, tools en books are shared, although immaterial properties

such as knowledge and experience are offered too. These platforms are able to distinguish

themselves from initiatives that are not part of the sharing sector by the positive message

conveyed, the new possibilities created and a low cost structure (as they don’t have to purchase

those assets).

The goal of this thesis is the design of such a platform for the Blue Park, a natural area

consisting of large parts of France, Wallonia and Flanders. The first step in the process is to

look at the sharing economy landscape to determine the position of the boat sharing platform

herein and how the system will roughly look like. Thereafter, this rough model will be further

detailed with the help of a group of potential users in online sessions.

This approach results in a

flourishing business model depicting the business and a system map

considering the different steps for a correct functioning. The map is complemented by an

application as a visual prototype of the system. Furthermore, a device is proposed to securely

close the boats offered on the platform.

The result is a system comparable with the rental of electric scooters, although the vehicles

offered here are not owned by the company, but consist of unused boats of providers on the

platform. A combination of a ‘dynamic lock’ and a GPS-tracker are proposed to secure the

boats, with the respective objectives to (un)lock the boat and display the current location.

Further research consists of the comparison between the system and its competitors on a

sustainable level through a

life cycle assessment, an actual installation of the system in the Blue

Park and the possibility to implement a system that aims to clean the environment with the

help of the users of the platform.

7

Abstract [NL]:

Het ontwerpen van product-service systems: een

deelplatform voor boten in het Blauwe Park

Op verschillende plaatsen verspreid over Europa bevinden zich talloze verwaarloosde boten

die geen nieuwe thuis meer vinden, hoewel ze, mits wat onderhoud best zouden kunnen

hergebruikt worden. Om zulke situaties te vermijden, biedt deze thesis een duurzamer

alternatief aan, namelijk een deelplatform waarop niet-gemotoriseerde, kleine boten zoals

kajaks en kano’s gedeeld worden onder gebruikers zodat eigenaars terug aangemoedigd worden

om hun eigendom te onderhouden.

Het delen van bestaande boten in de plaats van nieuwe te kopen is een voorbeeld van hoe

product-service-systems een positieve impact kunnen hebben op een ecologisch niveau en waarbij

de focus ligt op tevredenheid en niet zozeer op het product zelf. De deeleconomie had deze

boodschap begrepen en biedt al enkele jaren voordelige diensten aan waarbij zaken zoals

auto’s, gereedschap en boeken worden gedeeld, maar ook niet-materiële eigendommen zoals

kennis en ervaring. Deze platformen kunnen zichzelf onderscheiden van niet-deel initiatieven

door een positieve boodschap, de nieuwe mogelijkheden die gecreëerd worden en een

lage-kostenstructuur (aangezien ze deze eigendommen niet zelf moeten aankopen).

Het doel van deze thesis is het ontwerpen van dit platform voor het Blauwe Park, een

natuurlijk gebied dat zich verspreidt over grote gebieden van Frankrijk, Wallonië en

Vlaanderen. Eerst wordt een blik geworpen op het landschap van de deeleconomie om te

bepalen welke positie het bootdeelplatform hierin zal nemen en hoe het systeem er ruwweg zal

uitzien. Daarna wordt dit ruw werk verder gedetailleerd met de hulp van een groep potentiële

gebruikers in online sessies.

Deze aanpak resulteert in een

flourishing business model dat het bedrijfsmodel weergeeft, een

systeemkaart die de verschillende stappen voor een correcte werking beschouwt en een

applicatie als visueel prototype van dit systeem. Verder wordt er aangegeven welk soort

systeem voor de boten te sluiten aangewezen is.

Het resultaat is een systeem dat vergelijkbaar is met het ontlenen van elektrische steps, hoewel

hier de voertuigen geen eigendom zijn van het bedrijf, maar ongebruikte boten van aanbieders

op het platform. Er wordt voorgesteld om de boten te beveiligen via een combinatie van een

‘dynamisch slot’ dat via een smartphone kan ontgrendeld worden en een GPS-zendertje die de

huidige locatie aangeeft. Verder onderzoek bestaat uit het vergelijken van het systeem met zijn

concurrenten op vlak van duurzaamheid via een

life cycle assessment, een werkelijke installatie in

het Blauwe Park en de mogelijkheid om een systeem te implementeren waarbij de omgeving

schoongemaakt wordt door de gebruikers van het platform.

8

Designing Product-Services Systems: a Boat

Sharing Platform for the Blue Park

Sander Ameel

Supervisor(s): dr. Francesca Ostuzzi

Abstract – This work seeks to give an understanding how a boat sharing platform for the Blue Park can be constructed. The subject arises from a greater need for Sustainable Product-Service Systems (SPSS), in this case offering a response to a large amount of neglected boats in the European waterways. A conceptual framework is provided, consisting of a (Flourishing) Business Model, a systemic map determining the outcomes of different situations and a digital application to visualize the system to potential users. On top of that, a conceptual security system for the boats is proposed. The framework is a result of a top-down analysis of existing benchmarks in the sharing economy and a bottom-up approach implementing user input and needs into a larger system.

Keywords – Boat Sharing Systems, UX Design, PSS

I. INTRODUCTION

Although the subject recently came up (Verelst, 2019), the problem imposed by neglected boats is not a new phenomenon. In different harbours and waterways, and on quaysides over Europe, numerous boats lie rotting for years from now. The vehicles disturb the gentle view on the environment, pollute the waters and are a danger to other active users of those waterways. It is estimated that in the Netherlands, 25 000 boats linger around, while in France and the UK, the number of abandoned boats rise to about 50 000 each (Verelst, 2019). As the cost to dispose or recycle the boat is considerably higher than the intrinsic value of the boat, the owners of these boats generally do not take steps to bring the boat back in an – admitted, low – value chain, but don’t maintain it either. They might have inherited the boat without experience with it or grown tired of it and there is thus little incentive to take care of the boat.

This leads to an accumulation of boats in concentrated areas which will all one day become saturated. However, the process of decomposition, burning or recycling isn’t sustainable either: the composite hull is only partially recycled, the process is quite resource-intensive and purchasing virgin components is still more financially attractive.

Boat sharing could provide a solution, as it offers owners an opportunity to reuse the boat, get more value out of it and eventually trigger to maintain the vehicle better. Additionally, sharing can avoid the impact of boat production, as the system user’s wish for a boat trip is fulfilled without the step of purchasing the vehicle.

Such systems do already exist for motorized boats, but are still not that environmental-friendly due to the extra usage of fuel. The cost of transportation can be logically reduced by providing non-motorized boats, with the side note that the additional maintenance inherent to the system cannot be avoided, although it is certainly a better solution than neglecting the boat up to the point of disposal.

II. STATE OF THE ART

A. Sustainable Product Service Systems

The term Product Service Systems (PSS) is used to describe the systemic approach taken by companies, institutions and other providers in the process of fulfilling the need of its clients, considering a whole service with a strong emphasis on delivering satisfaction rather than a product (E. Manzini & Vezzoli, 2003). However, not all PSS are sustainable Product Service Systems (SPSS).

Manzini & Vezzoli discern three main characteristics that, among other potential strategies, can lead to SPSS. Adding

value to the product life cycle, providing final results to the customer and enabling platforms to the customer.

‘Enabling of platforms’ is the strategy this work will adopt, under the form of a sharing platform.

B. Sharing economy in literature

Sharing Economy is a relatively new phenomenon in the global economy. Many initiatives took off before or at the start of the millennium, but it became really known for the protests against Uber in June 2014 (Tran, 2014). Around that period, the European Commission issued a considerable amount of researches to investigate these ‘new’ competitors (a.o. Daveiro & Vaughan, 2016; Goudin, 2016; Hausemer et al., 2017; TNS Political & Social, 2016).

The benefits of collaborative platforms as reported by their users are described in a report of TNS Political & Social: They indicate a more conveniently organized access to services is the main benefit offered by such platforms to 41% of respondents who have heard or visited them. The advantage of being cheaper (33%), the ability to exchange goods instead of purchasing (25%) and the ability to use of new or different services (24%) too speak in favour of collaborative platforms (TNS Political & Social, 2016, p. 4).

On the flipside, respondents in the same report indicate information is generally lacking. They do not know who is responsible or are disappointed when services or goods do not meet the expectations (total: 85%). Trust is the second most important issue, with 28% of the respondents not trusting internet transactions in general and 27% not trusting the provider or seller. (TNS Political & Social, 2016, p. 4).

On a macro-level, reusing assets provides a reduction in emissions from production and waste, changes the consumption habits of its users and offers new opportunities to companies to become creative with existing assets. Sharing systems have their downsides too, as providing a longer lifespan also results in a higher cost of maintenance and additional emissions created by transporting assets between peers (Gertsakis & Lewis, 2003).

9

Trust is the keyword, finds Rachel Botsman, one of the renowned supporters of collaborative consumption. Trusting the idea, the company and the other is necessary to make the system work, and to overcome that threshold, three important steps must be taken (Botsman, 2017).

First, there is understanding: trying to make the unfamiliar sound, look or feel more familiar. Botsman gives the example of Airbnb, where director of research Judd Antin says: “What we observe when new guests come to the site is that they don’t typically go to the educational materials … Instead, they go straight to the search box and they search for places in their hometown because it’s a place they know, right?” (Botsman, 2017, para. 8).

Next comes the potential gain, the benefit for the peer when they participate in the platform. This can consist of both financial and social value.

The last step is seeing other unexpected users embrace the platform. Early adopters are a good start for a platform, but if one would not expect these people to use it too, the threshold to step in oneself becomes suddenly very low.

Reputation systems are often seen as the innovation created by the sharing economy (Friedman, 2014, para. 4). Botsman even sees those systems as another way to build trust and a currency to be used in the sharing economy landscape (Botsman, 2012). Tom Slee, author of the book What’s Yours

is Mine: Against the Sharing Economy, is more sceptical. He

sees reputation systems assess things like friendliness, cleanliness and punctuality, but not the aspects that should really be measured, such as a sufficient fire safety system in a building.

C. Shared transport

In his book Service Network Design of Bike Sharing

Systems, Patrick vogel describes the different network aspects

applied in shared vehicle systems. “The model of provision” implies whether vehicles are accessible from a specific location (station) or can be found anywhere in a designated area (Vogel, 2016, p. 20). The two terms used in this context are respectively the station-based and the free-floating model. The “different degrees of spatial flexibility”, then determine whether the car has to be returned to its original location (round-trip car sharing) or can be left anywhere within the system (one-way car sharing), be it to a station or in a specific area (Vogel, 2016, p. 20).

The question if these shared transport methods are sustainable or not depends largely on the circumstances. As ‘sustainable’ is a relative term, it is important to compare it to other systems that are supplementary to it (Ostuzzi, 2018). For example, the most sustainable option to choose among taking the bus or driving a car to go abroad depends on the amount of passengers, the route taken and the model of both vehicles, together with the advancement of ‘green energy’ – if at least one of them would be able to use it.

III. METHODOLOGY

The goal of this paper is to research and develop a potential Sustainable Product Service System (SPSS) design, proclaiming the sustainable values of a sharing transportation system consisting of boats. The environment considered to set up such a system is the Blauwe Ruit, a transnational area shaped by the rivers the Leie, the Deûle, the Canal of Roubaix and the Canal of Spiere-Helkijn. It is a tranquil environment in the Blue Park with cycling routes next to the water. Certain

sailing routes are used by inland waterway vessels and cross large cities such as Kortrijk and Lille.

The methodology consists of two large parts: the development of a broad, but general system based on benchmarks, and the detailing of that design based on the input of its potential stakeholders. In other words, the benchmarking is a top-down process, where a broad perspective on sharing platforms is used to model a rough system’s aspects (top-down), whereas the details of this system are determined by the stakeholders in that system (bottom-up).

Figure 1: Venn-diagram depicting the boat sharing platform and its stakeholders within the sharing economy landscape. The blue arrows indicate the approaches taken in this work. Image created by the author in Adobe Illustrator.

The business model and system map resulting from this process are eventually assessed with a SWOT-analysis.

IV. METHODS

A. Benchmarking

In the first stage of the process, a matrix was constructed from the research on sharing economy and the information found about six different companies in this field. To determine which parameters should be included to assess the six benchmarks on, a relational wordcloud was made with the keywords from literature and from experiences with boat systems built up through earlier research. This was meant to bring order to the large amount of data provided and sort out the important parts.

Figure 2: Relational wordcloud of parameters about sharing systems and shared transport. Image created by the author in Kumu.

Top-down

10

Through iteration on this cloud of words, four main keywords remained: Organization, System, Value and

Transportation. Under Organization, aspects such as the

business model, financial position, customer service, pricing and stakeholders of the company would be assessed. The

System implies all aspects that help the company provide its

services. This includes the technology used, information provided, a design for trust, safety, accessibility and the service itself with all services supporting it. Value considers all positive and negative consequences resulting from the system for the environment, the company, platform users and other players in the field. Lastly, Transportation explores what vehicle sharing model is adopted and if it is linked to other means of transport.

As said before, these previous terms are used as parameters in a comparative matrix for the benchmarks. The data – the ‘answers’ of the company to these parameters – is thus provided by the benchmarks, the six companies considered.

This matrix is then used as inspirational source to model a flourishing business model canvas (FMC) (Jones & Upward, 2014) and a systemic map. Both will have ‘gaps’ in their models, which are meant to be completed in a bottom-up manner.

Figure 3: Representation of the process to use the ‘answers’ of one parameter to model the FMC (top right) and the system map (bottom right). Image created by the author in Adobe Illustrator.

B. Co-design sessions

The co-design sessions are the first step in the bottom-up approach: participants of these sessions would discuss possible implementations in the sharing system, and give feedback on established aspects of the preliminary system (the business model and the systemic map) designed with the comparative matrix. The sessions are in nature online discussions in which visual representations of the platform guide the participants in their decisions. A role-play is adapted where each participant is either User or Provider and is expected to respond to questions from that perspective, although they are explicitly told their own perspective is certainly welcome, even if it would deviate from their role’s perspective. The purpose hereof is to initiate a discussion and view different perspectives despite the low number of participants in the sessions (each time two, plus the moderator). The moderator takes up the role of Platform.

The method used is similar to online focus groups. As Bruce Hanington would describe it, focus groups are “a qualitative method often used by market researchers to gauge the opinions, feelings, and attitudes from a group of carefully recruited participants about a product, service, marketing campaign, or a brand” (Hanington, 2019, p. 118). A moderator tries to trigger a reaction from the participants and guides the conversation. However, where a focus group is

mainly an exploratory method, the co-design sessions are meant to be both exploratory and generative: participants give their opinions about the proposed ideas, but are also encouraged to suggest their own.

The two major aspects (‘gaps’) of the preliminary system to assess in the sessions are the relationship between peers and the means of locking the boats. The first gap considers two possibilities, a peer-to-peer (P2P) and a peer-to-vehicle (P2V) system. The term ‘a peer-to-vehicle system’ does not quite exist in current literature. In this context, its purpose is to have a comprehensible term that describes a system where someone is able to rent out a provider’s boat, without that person being physically present in the moment of the exchange. This is opposed to a P2P system, where the tenant must make an appointment with the owner to unlock the boat.

The second gap, the means of locking the boats, distinguishes four possibilities to protect the offered vehicles from theft: a classic (cable) lock, a GPS-tracker, a ‘smart lock’ and a ‘dynamic lock’. These last two concepts are introduced to offer a possibility to open and close a boat without being able to do so again by remembering the numerical code.

The concept of the smart lock is explained in fig. 4. The design is inspired by the system to unlock a shopping cart where a coin is inserted, to receive it back only when locking the cart again. Here, the value of the boat would be too large to use a simple coin and thus the idea rose to use the smartphone of the tenant instead. The phone would be locked in a casing, then the app checks for access to the boat and if so, the system unlocks. The phone remains encased until the lock is closed again.

Figure 4: The unlocking process of the ‘smart lock’. Image created by the author in Adobe Illustrator.

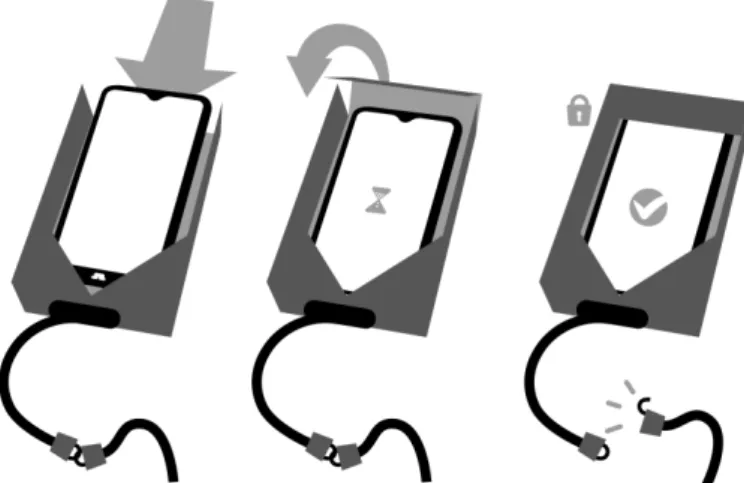

The other proposed concept is the dynamic lock, shown in fig. 5. The lock would use near-field-communication (NFC) to implement a unique, dynamic code (thus the name), transferrable from the smartphone to the lock. To unlock, the device needs this code, which is given upon booking by the app. Closing again works the other way around, where the lock would send a confirmation to the app. Whereas the smart lock is shortly charged by the phone, charging the internal battery here would be realized by an (integrated) solar panel.

11

Figure 5: A code sent to the ‘dynamic lock’ through NFC. Image created by the author in Adobe Illustrator.

The other locking systems should be quite obvious: the GPS-tracker is meant to be installed in the boat of the provider and this way, the platform is able to check if a moving boat was booked or not. It also helps to find the boat back when stolen. The classic lock works with a number code or key. The main issue here is that once the code is known or the key obtained, anyone can use it again without booking and there is no system that triggers the tenant to close it again. To avoid these problems, a P2P system would be necessary, where at least there is a possibility to build a bond between peers to avoid theft.

C. Survey

Conducted on a warm spring day, this survey would ask to people in and around the waterline of Ghent if they would participate in a boat sharing system. The respondents’ replies to this question (yes or no) are registered using field notes, together with their age and whether they own a boat themselves. Although not really building up the system design, the results could strengthen – or weaken – the position of the business model with this quantitative data.

D. System finalization

The results from the co-design sessions and the survey enable a final system design, resulting in a business model, a system map and the necessary tools. These tools consist of an app and a security system for the boat. A SWOT analysis is applied by the author to assess the final system. It is generally used to examine the strengths (internal positive points), weaknesses ( internal negative points), opportunities (external positive points) and threats (external negative points) of a new business concept (Poelaert, 2014).

V. RESULTS

A. Benchmarking

The companies Peerby BlaBlaCar, Share2Use, GetAround, Barqo and Bird were considered as the six benchmarks. They are, except for Bird, all players in the sharing economy. The reason why Bird is considered here is for its service of e-scooters: it uses a ‘P2V’ model where scooters are unlocked with a smartphone and the scooters can be left anywhere (free-floating model). Another choice that might seem remarkable is Peerby, a tool sharing platform: it does not have much to do with transportation, but offers a unique system to match supply and demand, starting from the peer who did the request. On top of that, it provides the possibility to share tools for free. The other platforms are chosen for their link

with boats (Barqo) and more generally their differences in the vehicle sharing model applied.

The different ‘answers’ to each parameter were summarized and decided on by the author. Then, with this information, the preliminary FMC, system map and app were constructed, with some parts not yet complete. As described in the methodology of the co-design sessions, the most important choices left open were the P2P / P2V model and the locking system. Other aspects the participants’ opinions would have to help decide are, among others, the deposit that should be paid up front, the registration process, the information available and the insurance regulation.

B. Co-design sessions

Three co-design sessions were held with each time two participants and the author as moderator. The first session included two design students of the same education program as the author: Industrial Design Engineering at UGent, Campus Kortrijk, and the second session was with two retirees. The last one comprised a representative of

Designregio Kortrijk and someone who owns different kinds

of boats and has experience with being a provider on sharing platforms.

In general, the participants’ preferences were given to the P2V system with a dynamic lock. In all cases, the ease of use was usually the deciding factor.

The participants who took up the role of Owner all indicate the various preparations necessary to let another peer use their boat, make them dissociate with the P2P system: it is too time-consuming compared to the value received and it is not possible to be available at any time. Users don’t want to depend on the owner either and would rather be able to use the boat without much trouble. The two students and one of the retirees indicated they would like to be able to contact the owner in case something goes wrong or just for additional information. This form of communication could even be two-sided, where the Provider would receive a confirmation message of a successful rental.

Each of the five participants who did not own a boat found the idea of giving up their smartphone quite undesirable. Being unable to take pictures of the trip or make an emergency call seems too much of a drawback to rent a boat through this system. Another important thing is that upon reservation of multiple boats, the tenant has to have multiple phones for each boat to unlock them, and this can be considerably problematic when booking boats for children. The dynamic lock is in their opinion just as secure as the smart lock, but more user-friendly. The one owner, however, found the idea of a value-exchange quite compelling, seeing how much people are attached to their smartphones. He did not see the dynamic lock as equally secure, because once the lock is opened, the tenant could block or delete their account and get away with the boat while paying only a fraction of the boat’s value. In the best case, the smart lock is accompanied by the tracker to ascertain the location when it drifts away or gets stolen.

All participants except the representative of Designregio

Kortrijk see the tracker as a good or necessary addition to the

other lock of their choice to increase security, with one of the students stating “it should offer additional redundancy”. The decision of the participants for the smart or dynamic lock was largely based on their rental system of preference (P2V), as they all found the classic lock sufficient for a P2P-system.

12

C. Survey

104 respondents were found willing to answer the simple question “Would you participate in a platform where you can rent out someone else’s boat?”. Only two did not have their age registered.

The negative responses are relatively low: only 22 do so (21,1%), mentioning it might be too complex, that they would rather use a classic rental service, share it only with friends or are just not that interested in boats.

Figure 6: The number of respondents (boat owners or not) with their responses to the question: “Would you participate in a platform where you can rent out someone else’s boat?”. Graph created by the author.

Some of the respondents who answered positively, bring up some conditions that are important to them to participate: the most frequently heard remark is that it should be cheaper (often not specified to what it should compare, although in some cases mentioning the boat rental they used at that moment), immediately followed by the ease of use.

Among the boat owners, the balance tends to tilt to using the platform while providing your own boat, with 13 respondents (12,5%) found willing to do so. It is important to note that people who own a rubber boat are generally willing to participate, although not as provider, as they think their boat won’t last long due to the extra usage created by the platform. Some of them mention they would instead offer another, less fragile boat if they had one. Another owner answered a boat is too personal, while someone else would do it if there is a deposit, an amount to be paid up front, included. A comparison based on the age category was considered to see who is more inclined to use the system and therefore what the major target group of the platform could be. Fig. 7 gives an overview of the results, with each age category’s answers in percentages to make a proper comparison (the larger part of respondents were aged between 19-25 and 26-35 – resp. 30 and 38 respondents).

Figure 7: The percentage of respondents in each age category responding positively or negatively to the question: “Would you participate in a platform where you can rent out someone else’s boat?”. The last age category contains (two) respondents whose age was not registered. Graph created by the author.

What stands out in this figure are the negative replies by respondents aged 56 or more. However, the sample size of this subset of respondents is insufficient to speak of significant results: only three individuals fall in this category and none of them owned a boat.

This is more or less the same case in the category 18 or younger, where not a single one of the nine respondents owned a boat, although the answers are more equally distributed between ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

In the category 36-45 (10 respondents), the idea finds only approval, although the two boat owners would not offer their own boat. Respondents aged 19-25 and 26-35 give very similar answers, with only 20% and 13% (resp.) stating they would not use such a platform. For boat owners aged 19-25, the responses are evenly distributed between providing and not providing (each four respondents). Important to note is the fact that all individuals choosing to not offer their own boat possessed a rubber boat and stated it would wear to fast. Only one individual would not participate in such a platform at all.

In the category 26-35, more or less the same trend appears, although slightly more boat owners were willing to offer their own boat (13% or five individuals, compared to 11% or four individuals using but not providing) and no boat owner would not use the platform in this age category.

Finally, in the category 46-55 (12 respondents), the majority of boat owners willing to offer their own boat can be found. Important to note: this is only true percentage based. Three out of four boat owners replied in this way, the other answered to use the platform but not provide a boat. There is quite some acceptance of the idea, with only one in four respondents (25%) stating they would not use such a platform.

D. System finalization

Fig. 8 shows gives the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats inherent to the system, as seen by the author.

13

Figure 8: SWOT-analysis of the boat sharing system. Image created by the author in Adobe Illustrator.

VI. DISCUSSION

A. The final system

The final business model and system map are based on the P2V model, as it is the one preferred by all participants of the co-design sessions.

Figure 9: The final business model of the boat sharing system as displayed on the flourishing business model canvas. Image created by the author in Adobe Illustrator.

Figure 10: System map of the boat sharing system. Image created by the author in Miro.

The system is in its essence a matching platform where Users can book boats offered by Providers through a list or a map. Providers offer their boat by providing photos, information and a location to the app Payments would be handled through a payment processor, insurance is included in the fee for Users and in a classic insurance for the Provider.

The business model works with fees to keep the system healthy, as used by many other businesses in the sharing sector. It further uses up-front deposits to discourage misbehaviour and relieve the insurance partner as much as possible. Deposits are returned to the owner in some weeks after unsubscribing, given there is no report sent to the platform that involves one of the boats rented before that period. Other important resources are the open waterways and input from the community. This input can be through surveys conducted by the platform, but also by problem reports sent by users. For example, when a boat does not meet the expectations, the User can send a photo of the current situation and the platform employees will compare that photo with the photo(s) provided by the owner.

Bookings are decided to be without reservation times, in that sense that a booking is always for one day but the time spent on the boat is registered through the app. The main disadvantage considered is that only one User can book a boat in advance per day. This does not outweigh the advantages though, being less stressful to return the boat on time, room for being late or early, a better understanding if a boat is missing instead of too late and no conflicts possible with other tenants who booked after you.

Its major costs are the staff (to maintain a good service) and the production and distribution of the locking devices. The lifecycle of these devices is expected to have the highest environmental impact.

The choice for a P2V model makes the classic locking system obsolete, but no straightforward choice is present among the others. The tracker is able to find the boat back when lost or stolen, but cannot lock tools and does not guarantee a correct closing of the boat. The ‘smart lock’ does not require continuous charging and does lock both tools and vehicle, but requires for each boat a phone and is less favoured by the participants of the co-design sessions, as they cannot use their phone in the same way. The last one, the ‘dynamic lock’ does not require to lock a smartphone in it, allows one phone to open multiple boats and still does the same things as the ‘smart lock’. It does however require charging with solar panels and is less favoured by the one boat owner in the sessions. In any case, one of the last two locks in combination with the tracker would be the preferred option of the participants, but implies a double cost to the platform.

Partnerships with the Eurometropole, the Vlaamse

Waterwegen and local institutions are important to ensure

legal sailing, provide important ‘landing spots’ and see how both can benefit each other’s work.

The platform offers transparency to its users. For example, when a price point is suggested to the Provider, the calculation information is shown, such as average prices of other providers, taxes and the estimated cost to maintain the vehicle. In turn, the app asks some transparency too: Providers must upload official documents of the boat to make an estimate on the value for the insurance and take photos of the original state of the boat. Users should take pictures of the boat before the start and again at the end of the rental, to be used by the platform in case of damage or theft.

14

Finally, the mission of the platform is creating more sustainable transport behaviours and making the waters (of the

Blauwe Ruit) accessible to as many as possible. B. SWOT-analysis

The SWOT-analysis shows one of the greatest strengths of the platform is its positive message about a better usage of boats, which helps to attract peers. However, to convince them to participate, the ease of use is the most important factor. In this perspective, the dynamic lock is the best choice, as it offers a fast and secure way to access and lock boats.

Ease of use was often mentioned in the survey too, but a lower price is the most heard remark. The low operation cost of the platform could help to keep prices low, but much will depend on the local supply of boats.

The platform could have strong competition from other boat rental services, who might try to undermine the sustainable character and offer a more personal service than the platform’s. However, cooperation with those competitors might be necessary on one issue: providing safety jackets to peers. Both User and Provider are reluctant to provide one, as in general, having to look for your own tools is seen as a drawback by the participants of the co-design sessions.

The platform further has to account for high initial losses in the start-up phase, as the platform will be relatively unknown, high costs will manifest in the development of the platform and the production and distribution of the lock too.

Safety is an evident issue in these matters, yet, at what price? An insurance provider must be found willing to cover the risks – theft, injury, damage, etc. – presented by this system, and if so, will impose its own conditions, having an influence on both the price and the system model. The deposit paid before being able to book is seen by the participants as a good way to discourage peers from stealing the boat or its tools on their first rental, although the GPS-tracker makes the system even more attractive to boat owners to offer their boat. The amount must be balanced between ‘high enough to discourage thieves’ and ‘low enough not to scare off potential tenants’.

To end with a positive note, the platform receives high acceptance in the conducted survey. This can be the basis for a solid launch of the system. Once the community has sufficiently grown, the platform should be able to make profit and start new projects: to strengthen the community even further, ways to connect with other boat providers can be implemented such as organized events or possibilities to (offer) repair. A last opportunity could imply to include tools to clean the environments of the waterways, so tenants can give nature a hand (in exchange for benefits on the platform).

VII. CONCLUSION &FUTURE WORK

This paper should have managed to give a good understanding how a boat sharing platform can be worked out. Although the result is eventually not specifically designed for the Blue Park, it could certainly work there too, or at least at certain places. The top-down and bottom-up methodology resulted in a Flourishing Business Model Canvas and a systemic map guiding the different situations. Yet, some ‘gaps’ still have to be filled in with further research, such as the design of the locking system, a working digital application and specific numbers to determine prices, deposits, fees, insurance, etc. Future work could consist of a real-life implementation of the system with tests to assess the

user-friendliness of the platform and the consequences of this installation on its environment. Next, a more systematic approach could be taken to trigger peers to clean the waters at the Blauwe Ruit, i.e. by providing a reduction in price and enough trash cans to support the behaviour. The proposed security system is the ‘dynamic lock in combination with a GPS-tracker, although with some design tweaks, the ‘smart lock’ could eventually be a better solution. More input from potential providers might be necessary too. However, it is acknowledged that the platform will continuously try to improve itself after realization and thus the system will never be finished.

As shown already in the literature review, it is not at all easy to predict whether this system will have a positive impact on a sustainable level as PSS. This would require a lifecycle assessment considering the behaviour of its users, the additional maintenance caused by an extensive usage, and most of all, the production, distribution and other stages in the life cycle of the lock and tracker.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper was made possible thanks to the support of the Eurometropole Lille-Kortrijk-Tournai and UGent Campus Kortrijk.

REFERENCES

Botsman, R. (2012). The currency of the new economy is

trust. TED Global.

https://www.ted.com/talks/rachel_botsman_the_currenc y_of_the_new_economy_is_trust/transcript#t-86262 Botsman, R. (2017, December 8). The three steps of building

trust in new ideas and businesses.

https://ideas.ted.com/the-three-steps-of-building-trust-in-new-ideas-and-businesses/

Daveiro, R., & Vaughan, R. (2016). Assessing the size and presence of the collaborative economy in Europe. In

PwC UK.

http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/16952/attach ments/1/translations

Friedman, T. L. (2014). And Now for a Bit of Good News . . .

The New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/20/opinion/sunday/th omas-l-friedman-and-now-for-a-bit-of-good-news.html Gertsakis, J., & Lewis, H. (2003). Sustainability and the

Waste Management Hierarchy. A Discussion Paper on

the Waste Management Hierarchy and Its Relationship to Sustainability, March, 16.

http://www.ecorecycle.vic.gov.au/resources/documents/

TZW_-_Sustainability_and_the_Waste_Hierarchy_(2003).pdf Goudin, P. (2016). The Cost of Non- Europe in the Sharing

Economy. In European Parliamentary Research Service (Issue January). https://doi.org/10.2861/26238

Hanington, B. (2019). Universal Methods of Design Expanded

and Revised: 125 Ways to Research Complex Problems, Develop Innovative Ideas, and Design Effective

Solutions. Rockport Publishers.

https://books.google.be/books?id=BYTPDwAAQBAJ& lpg=PP1&dq=Universal Methods of Design Expanded and Revised&hl=nl&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false Hausemer, P., Rzepecka, J., Dragulin, M., Vitiello, S., Rabuel,

L., Nunu, M., Diaz, A. R., Psaila, E., Fiorentini, S., Gysen, S., Meeusen, T., Quaschning, S., Dunne, A.,

15

Grinevich, V., Baines, L., & Huber, F. (2017).

Exploratory study of consumer issues in online peer-to-peer platform markets. In European Commission (Issue May).

http://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/just/item-detail.cfm?item_id=77704

Jones, P., & Upward, A. (2014). Caring for the future : The

systemic design of flourishing enterprises. 15–17.

Manzini, E., & Vezzoli, C. (2003). A strategic design approach to develop sustainable product service systems: Examples taken from the “environmentally friendly innovation” Italian prize. Journal of Cleaner

Production, 11(8 SPEC.), 851–857.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-6526(02)00153-1 Ostuzzi, F. (2018). Sustainability - Module of the course

Cybernetica en systeemgericht ontwerpen.

Poelaert, L. (2014). Bedrijfskunde - De essentie. Garant Uitgevers.

Slee, T. (2017). What’s Yours is Mine: Against the Sharing

Economy. OR Books. https://doi.org/10.237/j.ctv62hf03

TNS Political & Social. (2016). Flash Eurobarometer 438 -

The use of collaborative platforms.

https://ec.europa.eu/COMMFrontOffice/publicopinion/i ndex.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/instruments/FLASH/ surveyKy/2112

Tran, M. (2014). Taxi drivers in European capitals strike over Uber – as it happened. The Guardian.

https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/jun/11/taxi-drivers-strike-uber-london-live-updates

Verelst, V. (2019, December 9). Duizenden verwaarloosde

polyester boten veroorzaken groeiende afvalberg.

https://www.vrt.be/vrtnws/nl/2019/12/03/geen-bestemming-voor-duizenden-oude-polyester-boten/ Vogel, P. (2016). Service Network Design of Bike Sharing

Systems. Springer International Publishing.

16

17

Designing Product-Services Systems:

A Boat Sharing Platform

for the Blue Park

18

Table of content

Preamble ... 4

Acknowledgements ... 5

Abstract [EN]: ... 6

Designing product-service systems: a boat sharing platform for the Blue Park ... 6

Abstract [NL]: ... 7

Het ontwerpen van product-service systems: een deelplatform voor boten in het Blauwe Park .... 7

A Boat Sharing Platform for the Blue Park ... 17

Table of content ... 18

Glossary of terms ... 20

Intro ... 22

Objective ... 24

Observations at the Blauwe Ruit ... 26

Method ... 26 Results - Observations ... 27 Results – Interviews ... 29 Discussion ... 29 PSS: Sharing systems ... 30 Literature on Sharing ... 32 Methodology ... 45

The design spiral methodology ... 45

Top-down, bottom-up ... 46

The preliminary system mapping process ... 48

The first steps in building the matrix ... 48

Selection of benchmarks ... 50

Building up with the matrix ... 51

Process example ... 54

Assessment of the preliminary system ... 58

Co-design sessions ... 58

Blueprints for the sessions: Online focus groups ... 58

Goal ... 59

Co-design sessions explained ... 60

Classic (number) lock... 65

Tracker ... 65

Smart lock ... 66

Dynamic lock ... 66

Diving into the cases ... 67

19

Complementary survey ... 71

Approach ... 71

Results ... 72

Construction of the app ... 75

Discussion ... 77

Closing ... 83

Conclusion ... 83

Future work ... 84

Back matter: Pre-Corona Research ... 85

Initial strategy / methodology... 85

Interviews ... 86

Protopitch boostcamp ... 87

Aim for comprehension ... 87

Proposed concept ... 87

Soiree Circulair: networking ... 88

Prototyping ... 88 Feedback ... 89 Reflection ... 89 Brainstorm session ... 90 Setup ... 90 Results ... 91 Discussion ... 95 Physical test ... 96 Objective... 96 Setup ... 96 Results ... 97 Discussion ... 99 Morphological Chart ... 100

Updating the methodology ... 100

Construction of the chart ... 100

Use of the Chart ... 101

‘The two extremes’ ... 102

The station-based model ... 102

The free-floating model ... 104

Discussion ... 106

20

Glossary of terms

“Boat”

Any vehicle that floats and can be used to sail on the water. In this thesis, the term is narrowed down to non-motorized, small vehicles including (but not limited to) kayaks, canoes, water cycles, rowing boats, etc. Vehicles not included (but again not limited to the following) are (sailing) yachts, inland waterway vessels, container ships, cruises, motorized pleasure vessels, jet-skis, etc. Any large motorized water vehicles will be referred to as ‘ship’, except in the extracts reviewed from literature.

Early adopter

According to Cambridge Dictionary, an early adopter is “someone who is one of the first people to start using a new product, especially a new piece of technology.” 1

Sharing Economy vs. sharing economy vs. collaborative consumption vs. peer-to-peer economy In order to avoid confusion about these terms, I’ll try to – instead of giving one definition – explain how the terms should be understood and distinguished from each other in this paper.

Sharing Economy, with capital letters, can be seen as the group of organizations that

consider themselves part of the movement with the same name. Instead of this term, I’ll use the non-capitalized version of it in the manuscript, sharing economy, with the meaning

of anything that can be considered as an organization offering the efficient use and redistribution of assets (goods, knowledge, skills). These organizations range from public libraries to companies such as Kickstarter2.

Collaborative Consumption is used to emphasize the difference with traditional consumption,

where consumption happens between (or inside) networks of people instead of a centralized institution (resp.). Peer-to-peer (P2P) economy does not necessarily have

something to do with sharing things but is again used to differentiate with Business-to-Business (B2B) or Business-to-Business-to-Consumer (B2C) transactions. Peer-to-Peer transactions are characterized by a certain personal exchange where you have to trust the other (e.g. purchasing second-hand household appliances on a flea market). Both explanations are mainly based on Rachel Botsman’s article The Sharing Economy Lacks A Shared Defenition

(Botsman, 2013).

1 Link: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/early-adopter last accessed 16/08/20 2 Kickstarter promotes crowdfunding campaigns on its platform to help ‘kick-start’ creative projects. Link: https://www.kickstarter.com/ last accessed 16/08/20

21 Waste Management Hierarchy

Also called the 5R’s, 6R’s, 7R’s or even 8R’s – depending on the source – of the Circular Economy. The terms are generally shown in a triangle (it has some similarities with the food triangle, such as the base part being most preferable and the top least) and the hierarchy consists– from base to top – of Refuse, Reduce, Reuse, (Repair,) Recycle, (energy Recovery,) and finally, Rubbish (a.o. Gertsakis & Lewis, 2003). Repair can be seen as a way of recycling

(literally bringing a product back in its cycle) and Recovery as a slightly different form of disposal. Other sources add ‘Rethink’, ‘Rehome’ and ‘Replant’ to the list, but these are already covered by other terms or seem too specific for the broad Circular Economy. For additional information on waste management or Circular Economy in general, please visit the website of Vlaanderen Circulair3.

3 Vlaanderen Circulair or Circular Flanders supports initiatives in the Circular Economy and connects them with other institutions, governments and companies in Flanders. Circular Flanders is embedded in the operations of the OVAM (the Public Waste Agency of Flanders).

The infographic named Goals and Strategies for circular purchasing on the Infographics page builds further on the Waste Management Hierarchy providing several examples, although more specific towards companies’ purchasing strategies.

Link: https://vlaanderen-circulair.be/nl last accessed 16/08/20

Refuse

Reduce

Reuse

Recycle

Recover

DisposalFigure 1: The Waste Management Hierarchy. Figure created by the author.

22

Intro

In December 2019, a crew of VRT4 reporters investigated the problem of neglected boats in

and around the waterways of Flanders and its neighbours (Verelst, 2019). In their article, they estimated the amount of abandoned boats in France and the UK at about 50 000 boats each. For the Netherlands, this would be 25 000. Belgium has no specific numbers, but “you don’t have to search long for neglected boats without a future. They lie in marinas, sailing clubs or simply on the inland waterways, all with so-called ‘overdue maintenance’”5 (Verelst, 2019, para. 4). The

main issue is that these – mainly polyester – boats cost generally more to remove and dismantle than the boat is worth, and thus remain where they are. The rotting boats do not only accumulate to a large amount of waste, they gradually pollute the water, are rarely recycled (France3Bretagne, 2020) and endanger the safety of other vessels (Verelst, 2019).

Until this day, the polyester hulls of the boats are burned – if they’re eventually taken out of the water, dismantled and transported – in domestic waste facilities in Belgium (Verelst, 2019). In France, the APER (Association for Eco-Responsible Pleasure sailing)6 is assigned to recycle the

polyester and other parts.

4 The Flemish Radio – and Television broadcast organisation is a public service broadcaster funded by the Flemish government.

Link: https://www.vrt.be/nl/ last accessed 07/07/20 5 Translated from Dutch

6 Abbreviation translated from French. The APER’s main objective was only transformed to its current one in 2018 and is the single official, non-commercial institution for the treatment of waste materials originated from pleasure or sports vessels in France. It is a pioneer on the European continent.

23

Going circular

According to the Waste Management Hierarchy, recycling is more preferable than burning. However in this case, recycling the composite hull is less interesting: APER admits on its website that separating the matrix-material and fibres is quite resource-intensive (which makes the process less sustainable compared to immediate burning) and those components are relatively inexpensive resources (which makes it financially unattractive) (Verelst, 2019).

The Waste Management Hierarchy provides another solution: what if these boats would be reused instead of being dismantled? Since a lack of time and a reluctant use of resources to

maintain the boat seems to be the main cause of the problem, making others use it might be an incentive towards good maintenance.

Boat sharing does already exist for motorized boats7, but raises the question if the system does

not cause more environmental harm due to the extra usage of fuel. In general, re-usage requires

additional transportation and maintenance (Gertsakis & Lewis, 2003), factors that cannot be overlooked. By stepping away from the motor part, the cost of transportation can be heavily

reduced – unless another motorized vehicle would be used to transport boats – and for the general purposes of this study, it is more interesting to examine the possible implementation of such a system, rather than assessing the existing services.

And indeed, more frequent maintenance will be necessary due to the higher usage, but this can help to enlarge the lifespan of the vehicle and can be compensated by potential income received through the renting system.

7 Sharing companies like GoBoat or Barqo offer their sharing platforms in different countries and help potential tenants and owners find each other.

24

Objective

This master thesis in Industrial Design Engineering (UGent, Campus Kortrijk) aims to provide an understanding of what elements are necessary to set up a sharing system service of non-motorized boats. These ‘elements’ are essentially all components crucial to a sharing platform, a business model, a Product Service System.

The originator of this master thesis, Buda Kortrijk8, aimed to stimulate a sense of sustainability

and connectedness in its home city by proposing to design a water transportation system – trying to trigger the local communities to embrace the sharing economy and eventually close the plastic loop in Kortrijk.

However, due to a change in promotership (and the changes related to the Covid-19 crisis, described in the preamble), the focus shifted to a more general development of a boat sharing system with the support of the transnational organization Eurometropole

Lille-Kortrijk-Tournai9.

8 Buda Kortrijk aims to make Buda island a hotspot for activity and creativity and is located in BK6

(Broelkaai 6), which they established as a co-working space and where numerous different events have taken place. Since January 2020, the organization has been taken over by the city of Kortrijk.

Link: https://buda-eiland.be/ last accessed 13/08/20

9 The Eurometropole not only aims to bring harmony on the institutional levels, it also offers walking tours, manages cycling routes and organizes cross-border activities to help the transnational community level. Links: https://eurometropolis.eu/ and https://www.blauweruimte.eu/ last accessed 13/08/20

25

The Eurometropole manages a large natural area of 3.589 km², called ‘het Blauwe Park’ or the blue park. It is largely determined by the rivers the Leie, Deûle and two canals with a connection

to the Schelde. Here, the organization manages a cycling route of 90 km right next to the waters: both the area and the cycling route are called ‘the Blauwe Ruit’, with the name originating from

the diamond-shape that is created by the rivers and canals mentioned earlier (fig. 2).

Their mission for the blue park is to highlight the beautiful environment and to make it accessible to everyone. Therefore, the idea of a shared water transportation system caught their interest.

Figure 2: Territory of the blue park / Blauwe Park, encompassing large parts of France, Wallonia and Flanders. Source: blauweruimte.eu/studies.

The structure of this paper has been constructed as such that the reader will first read through the larger part that describes the research, methodology etc., up to the discussion, essential to the outcome of this manuscript (p. 26 - 84.). Then, in the part that follows, the research, methods and results conducted before the implementation of the corona measures are listed (p. 85 - 106). Not working completely ‘chronologically’ is meant to increase comprehension, as some processes described in the ‘back matter’ do not quite contribute to the outcome of this paper. However, in the ‘essential report’, references are occasionally made to this earlier work. One part that actually took place before the corona-measures will still be included in the essential report – see the next

pages – to familiarize the reader with the Blauwe Ruit.

26

Observations at the Blauwe Ruit

These observations conducted at the Blauwe Ruit at the start of March were initially meant to

research the social and environmental factors that play there, to eventually use this data to setup a boat sharing system and tackle the potential waste problem. Now, it serves to give an impression to the reader about the environment the system is subject to.

More specifically, two main questions had to be answered.

First, is there a need and a possibility to tackle (plastic) waste? If so, where?

Secondly, is a water transportation system a good ‘instrument’ to tackle this problem?

Method

In an attempt to answer these questions, interviews are taken and observations made at the cycling routes of the Blauwe Ruit. More specifically, the observations consist of photographs and

videos taken at places where there is a lot of waste or (im)possibilities to install a water transport (e.g. sluices, slopes, traffic…). The matters learned with the test in December should help to guide the observations. The interviews are meant to see if the observations match the perception of people (Is there more waste than there is to the eye? Are people aware of the waste in their waterways?) and to hear their opinions on a shared water transportation system to tackle the problem.

The test has been divided into two parts: in the first part, the cycling route is followed leading from Lille to Kortrijk, following the Deûle and the Leie. In the second part, the canals of Roubaix, Spiere-Helkijn, Bossuit-Kortrijk and a small part of the Schelde would be observed. Observations would take place along the whole route, but for the interviews it was expected that most of them would happen in Lille, as the largest city on the way (except maybe for Kortrijk) and where a large part is surrounded by the Deûle. Other interviews would depend on chance encounters.

Questions were prepared (in French) for the interview, but were not strictly followed in the interview itself: this is because the questions were not read from the paper, to make the conversation feel more natural. There is no need to write things down on paper, as the whole conversation is recorded.

27 In short, the preparation follows this general structure:

1) Introduction of the author and his project.

2) Asking permission: Is it possible to ask some questions? Do you mind if this conversation is recorded?

3) The perception of waste: Do you think the waterways are clean? Does the city do enough to handle the pollution?

4) The water transportation system: Do you think a shared water transportation system could help fight pollution?

5) Show appreciation for their time.

Results - Observations

Due to the Corona precautions, It was not possible to do the second part of the observations, as crossing the border to Lille-Flandres was prohibited at a certain point and contacts with others strongly advised against. Still, the results from the first part are interesting.

From the observations can be learned there is quite some traffic on the Leie and the Deûle, with frequently passing inland waterway vessels. Four sluices help those boats to cross the two rivers. Interesting to notice is that some parts of the Leie (and the Deûle in lesser extent) have side arms where these boats do not pass. These smaller arms are not only easier to enter or leave for smaller boats, but also contain their part of plastic, in one case – in the neighbourhood of Comines – even more than the larger rivers. If the reader looks closely at fig. 3, they could see the waste lying on the riverbed where the moorhens took the opportunity to made their nest.

The rivers themselves might be more difficult to enter, as the borders are mostly steep slopes with a rocky

underground or just flat, horizontal steel to keep the borders from collapsing. The major possibilities were provided in the form of wooden docks at (or at some distance from) the marinas on the Deûle. For the Leie,

Figure 3: An accumulation of waste on a riverbed near a cycler’s bridge in Comines.

28

only in Wervik, near the Balokken – a natural reserve – there was a gentle slope on both sides of the river to allow easy access to boats.

Figure 4 & 5: A gentle slope on both sides of the river the Leie (between Wervik and Menen) vs. a rocky, steep border in Quesnoy-sur-Deule. Photos taken by the author.

There was not quite a pattern to see in the amount or location of plastic waste, with the Deûle equally dirty as the Leie, except Kortrijk is remarkably clean. This was of course a one-day observation, and based on a snapshot, it is impossible to tell if these places are always equally dirty, but the experiences during the time working at Buda confirm that the part of the Leie floating through Kortrijk is quite clean.

The pieces of plastic waste ranged from floating bottles, pieces of foam at the borders, small pieces of plastic (broken plastic cups, bottle caps, pieces of plastic bags…) at a nesting place of moorhens, a boat with its nose almost above the water near Lille, pieces of plastic wire nets from planted bushes near the water, debris floating in a whirlpool at the entrance of a sluice and plastic

packaging under bridges. Figure 6: A plastic bottle floating near the marina of

29

Results – Interviews

In total, three interviews were recorded.

In those interviews, all three were clear that the water streams are not clean and that education and awareness are most important in these matters. In Lille, the two persons interviewed there mentioned both the enormous amount of things that were dumped in the Deûle, most of all bicycles, pieces of wrecks and fences, which are occasionally dredged by fishermen. The man mentioned that plastic is also thrown into the river, but less. Both seemed to perceive the waste in the waters more as a danger for people – ships on the water, people diving into the water - rather than the environment.

This is in contrast to the man in Quesnoy-sur-Deûle, who is a kayaker himself and considers it his duty – and that of every other watersporter – to clean the waters when that’s possible.

He can of course only collect waste floating on or lying at the borders of the river and says it is mostly waste that belonged to some daily product (like a bottle of water). He organizes about once a year a large cleaning event where the whole community of Quesnoy-sur-Deûle can participate in and says it is necessary, but without their own efforts through daily kayaking, it would not be enough. He seems more concerned about the whole environment, mentioning the plastic soup, eating fish with plastic in it and areas threatened by plastic alone.

In general, the interviewees can appreciate the idea of a shared system to battle waste, but as mentioned before, they think it won’t be enough, that one should deal with the source of pollution first. The man in Quesnoy-sur-Deûle adds that – in his experience – it won’t be

necessary to let someone clean the waters every day, once a week should be sufficient. He can see it happen, but cannot quite guess if the system would really “attract more people” to take a kayak. The people in Lille confirm this somewhat by saying they would rather take their bicycle than a boat, where the lady would even add that one has to walk then from their boat to the point they want to be, losing a lot of time.

Discussion

The first round of observations gave a good view on where plastic is more prevalent than others, with the cities on the regional borders having most plastic waste, and the surroundings of

Quesnoy-sur-Deule the most clean waters – due to the presence of the kayak club and its commitments towards the Deûle. The location near Comines seemed interesting to setup the system, and this together with locations at the canal of Roubaix and de L’espierres (who were recommended by the Eurometropole). However, Covid-19 made an abrupt change in these plans and the execution was never realized.

And although the interviewees were not quite convinced a sharing system would trigger cleaning actions, it seems like this paper would have had to prove it can.