Academic Year: 2019-2020

Challenges of Ethiopian Food Security: The Case of Food

Taboos and Preferences

By: Alex Minichele Sewenet

Promoter: Prof. dr. ir. Marijke D'Haese

Co-promoters: Chinedu Obi & Fatemeh Taheri

Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the joint academic degree of International Master of Science in Rural Development from Ghent University (Belgium), Agrocampus Ouest (France), Humboldt University of Berlin (Germany), Slovak University of Agriculture in Nitra (Slovakia), University of Pisa (Italy) and University of Córdoba (Spain) in collaboration with Can Tho University (Vietnam), China Agricultural University (China), Escuela Superior Politécnica del Litoral (Ecuador), Nanjing Agricultural University (China), University of Agricultural Science Bengaluru (India), University of Pretoria (South-Africa) and University of Arkansas (United States of America)

This thesis was elaborated and defended at Faculty of Bioscience Engineering within the framework of the European Erasmus Mundus Joint Master Degree “International Master of Science in Rural Development " (Course N° 2015 - 1700 / 001 - 001)

Certification

This is an unpublished M.Sc. thesis and is not prepared for further distribution. The author and the promoter give the permission to use this thesis for consultation and to copy parts of

it for personal use. Every other use is subject to the copyright laws, more specifically the source must be extensively specified when using results from this thesis.

The Promoter The Author

Prof. dr. ir. Marijke D'Haese Alex Minichele Sewenet

Thesis online access release

I hereby authorize the IMRD secretariat to make this thesis available online on the IMRD website

The Author

Alex Minichele Sewenet

i ABSTRACT

Food norms are embodied in all essential components of food security. However, its adverse economic influence is under-researched in developing countries. Hence, the objective of this study is to investigate the impacts of food taboos and preferences (FTP) on food security in Ethiopia, one of the world’s most food-insecure nations with strict food norms. This exploratory study employed a qualitative research design, with semi-structured in-depth interviews as the main method of data collection and qualitative content analysis as the main method of data analysis. Primary data were collected from 11 key informants of multidisciplinary backgrounds such as stakeholders, experts, and decision-makers. The study is also reinforced with pertinent secondary sources. The findings revealed that FTP in Ethiopia have caused the underutilization of edible resources. Manifestations include complete food prohibitions and religious and secular normative restrictions. Besides, during Orthodox Christian (OC) and Muslim fasting days the overall food supply chain undergoes economic turbulence. Particularly, the economic challenge among OC fasting leads to (1) a decrease in consumption and supply of non-vegan foods, (2) the temporary closure of butcher and dairy shops, (3) an increase in the demand and price of vegan foods, and (4) an overall reduction in consumption and economic transactions. Moreover, the tradition of animal consecration at home made many Ethiopians independent of supermarkets, groceries, and other licensed meat shops. In turn, this impedes the country’s endeavor of attracting local and foreign private investors in the entire food sector. It also alienates people from access to food labels, meat quality controls, price, size, and choice advantages, all of which are essential for better, adaptive, and stable food utilization. The results discovered in this thesis enrich our general understanding of the power and role of food norms in economic systems. Particularly, the study sheds light on the indispensable need to systematically and meticulously consider the subject in policies and programs aiming to end food insecurity.

Keywords: food security; food taboos; food preference; mainstream food norms, religion; culture; Ethiopia.

ii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am indebted to VLIR-UOS for the generous financial help. Without this, I would not have made it through this privileged international MSc degree.

I am also grateful to my promoter Prof. Marijke D'Haese and my tutors Mr. Chinedu Obi and Mrs. Fatemeh Taheri for their professional guidance, motivation, and friendly advice from the beginning to the end of this thesis.

My special gratitude also extends to my family and friends for their unconditional love and support at all time.

Alex Minichele Sewenet August 2020

iii

ACRONYMS

AASTU: Addis Ababa Science and Technology University AAU: Addis Ababa University

ADLI: Agricultural Development Led Industrialization COVID-19: Corona Virus Disease 2019

CSA: Central Statistics Agency of Ethiopia EBI: The Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute

EOTC: The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church FAO: Food and Agricultural Organization

FTP: Food Taboos and Preferences GDP: Gross Domestic Product GHI: Global Hunger Index

IFAD: International Fund for Agricultural Development

NBE: National Bank of Ethiopia OC: Orthodox Christian

OCs: Orthodox Christians

SDG: Sustainable Development Goals UN: United Nations

UNDP: United Nations Development Programme UNICEF: United Nations Children's Fund

US: United States

WB: World Bank

WFP: World Food Programme WHO: World Health Organization

iv

DEDICATION

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ... i

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... ii

ACRONYMS ... iii

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ... 6

1.1. Background of the Study ... 6

1.2. Problem Statement ... 8

1.3. Research Questions ... 10

1.4. Significances of the Study ... 11

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW ... 12

2.1. Conceptual Definitions ... 12

2.1.1. Food Security ... 12

2.1.2. Culture ... 13

2.1.3. Religion ... 14

2.1.4. Food Taboos and Preferences ... 14

2.2. Theoretical Framework ... 16

2.3. The Ethiopian Economy and Food Security ... 19

CHAPTER THREE: STUDY AREA AND RESEARCH METHODS ... 21

3.1. Study Area: Sociocultural and Religious Overview ... 21

3.2. Research Design ... 22

3.2.1. Research Methods ... 22

3.2.2. The Selection of Samples ... 23

3.2.3. Data Collection and Analysis ... 23

3.3. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Thesis ... 24

CHAPTER FOUR: PRESENTATION OF FINDINGS... 25

4.1. Characteristics of Interviewees ... 25

4.2. The Features and Foundations of the Ethiopian Food Norms ... 26

4.3. The Mainstream Food Taboos and Preferences ... 31

4.4. The Impacts of food Taboos and Preferences on Food Security ... 34

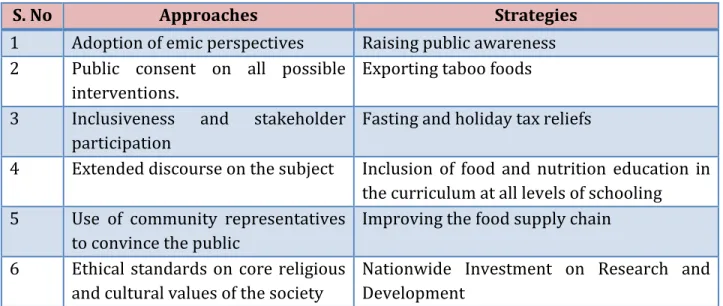

4.5. How to Improve the Adverse Economic Impacts of Food Taboos and Preferences ... 41

4.6. Prospects of Food Taboos and Preferences in Ethiopia ... 44

CHAPTER FIVE: DISCUSSIONS ... 46

5.1. Discussions ... 46

CHAPTER SIX: CONCLUSIONS AND AVENUES OF FURTHER STUDY ... 52

6.1. Conclusions ... 52

6.2. Limitations and Avenues of Further Study ... 54

6

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background of the Study

Food norms are written and unwritten standards that govern people’s economic behavior (Alonso, Cockx, & Swinnen, 2017). They instruct individuals of a society about the dos and don’ts concerning production, distribution, and consumption of food. Written food norms are part of laws and enforced by the state through the law enforcement agencies (Clinard & Meier, 2011). Whereas, unwritten food norms are handled through informal social control mechanisms (Chekroun, 2018). An example of informal social control is the use of positive and negative sanctions by kin or wider society as admiration and social exclusion for conformists and deviants, respectively (Clinard & Meier, 2011). Within this context, food taboos and preferences (FTP) are specific components of food norms (Alonso et al., 2017). Consecutively, they refer to the prohibition of a particular food or drink from consumption and the selection of what is most important from the socially recognized food (Smith, 2008; Meyer-Rochow, 2009).

FTP are neither absolute nor static (Alonso et al., 2017). They constantly change depending on society’s demand, research findings, change in people’s awareness, and adaptation (Onuorah & Ayo, 2003). In many Western societies, for instance, people used to consider entomophagyas unpleasant or taboo (Schuurmans, 2014). However, today this attitude is gradually changing following the growing and consistent research findings of the health, environment, and sustainability benefits of insect diets (Schulz, 2020). Furthermore, FTP are the outcomes of religious and secular factors (HLPE, 2017). Therefore, they differ across societies and so does their impacts on countries’ food security vary (Alonso et al., 2017; HLPE, 2017).

Food security is comprehended based on four major components, namely food availability, access, utilization, and stability (FAO, 2008). According to Alonso et al. (2017), all these constituents are overwhelmingly impacted by food taboos and preferences. These impacts, on the one hand, can be both positive and negative, though this thesis focused on the latter. On the other hand, they tend to be more powerful and overt in societies with strong social norms. In this regard, Ethiopia serves as an illustrative case within this thesis, being one of the world’s most food-insecure nations with persistent food norms. The strict nonscientific

7

FTP that are deeply rooted in the country’s religious, cultural, and traditional beliefs are believed to have adverse impacts on its food security (Seleshe, Jo, & Lee, 2014; Hopf, 2017), thus further worsening the prevailing food insecurity of the country.

For over three decades, Ethiopia has been extensively quoted across the world as an instance of chronic food insecurity (Cheru, Christopher, & Oqubay, 2019). This seems to be due to the 1984-85 ravage famine, which killed and internally displaced 1.2 and 2.5 million people respectively (Gill, 2010). However, since the end of the 1990s, the country has managed to become one of the fastest economically growing nations in the world with an average 8 percent GDP boost (Cheru et al., 2019). The effort has paid off in the country and reduced its Global Hunger Index (GHI) by a total of 26.8 within 18 years, 2000-2018 (WFP & CSA, 2019). But the progress is not left without criticism. Particularly, Cheru et al. (2019) argue that the success gained at the macroeconomic level is not properly trickling-down to reach the destitute and help them break the vicious circle of poverty (Cheru et al., 2019). Hence, the country has remained among the top 20 globally food-insecure nations (WFP & CSA, 2019). Thus, the Ethiopian government has endorsed a set of national strategic policies to become among the lower-middle-income countries by 2025 (WB, 2019) and to achieve the “no poverty” and “zero hunger” goals of the Agenda 2030 (UN, 2015), which involves sustainable food security (WB, 2019).

Fundamental to national food security yet often overlooked by concerned authorities are food norms (Alonso et al., 2017). As FAO (2019) exposed, nonscientific based normative food restrictions are among the reasons for the poor utilization of the existing nutritional plant and animal species in some African countries. In fact, countries with rich biodiversity have a potential comparative advantage of food availability and access over others with more limited resources (FAO, 2019a). However, the presence of rich animal and plant species does not necessarily mean more food. The case of Ethiopia is a good illustration. Ethiopia is among the top-ranked most biodiverse African countries (EBI, 2014; FAO, 2019a). The comprehensive weather conditions, which range from tropical to cool zones and elevation as high as Mt Ras Dejen, 4533 meters above sea level, and as deep as the Denakil Depression, 116 meters below sea level (Crummey & Mehretu, 2019), have made the country a home for 6000 plant, 861 bird, 200 fish, 201 reptile, 1225 arthropod, 63 amphibian, and 284 wild mammal species (EBI, 2014). Some wild animals and insects are

8

not properly registered yet. However, the number of animals and plants species recognized in the mainstream food culture are extremely limited for reasons related to religion, lack of awareness, and belief-based FTP (Seleshe, Jo, & Lee, 2014; Hopf, 2017).

In the fight against food insecurity in Ethiopia, the core political and economic bottlenecks and the way forward have been debated for decades in academic and non-academic discourses (Cheru et al., 2019). Therefore, this thesis deviates from this widely argued conventional outlooks and instead focused on investigating one of the least uncovered but equally important drivers of food security, namely food norms (Alonso et al., 2017; HLPE, 2017; Olum, Okello-uma, Tumuhimbise, Taylor, & Ongeng, 2017). Specifically, this thesis addresses the impacts of culturally and religiously based FTP on Ethiopian food security.

1.2. Problem Statement

Scientific based FTP are positively recommended from health and sustainability perspectives (Meyer-Rochow, 2009; Onuorah & Ayo, 2003; Smith, 2008). However, those FTP that depend on non-scientific roots, which are widespread in Ethiopia, are thought to have some adverse implications on food security (Seleshe et al., 2014; Hopf, 2017; Rogers, 2020). Just to mention a few, taken-for-granted food taboos and preferences can cause unconsulted food bans, poor dietary choices, and inconsistencies on production and consumption patterns which are all related to the main components of food security (Alonso et al., 2017). For example in Ethiopia, fasting is a dominant religious ritual that significantly affects the overall food demand and supply chains, food choices, and the frequency of daily calorie intakes (D’Haene, Desiere, D’Haese, Verbeke, & Schoors, 2019). After all, fasting constitutes a major reason that Ethiopians belong to one of the most vegetarian people in the world (Rogers, 2020). This is because fasting imposes strict rules on what and when to eat. However, the particulars vary depending on the specific guides of each religion, in this case OC and Islam.

For Ethiopian OC, fasting goes accompanied with abstinence from consumption and selective food proscription (Belwal & Tafesse, 2010; D’Haene, Desiere, D’Haese, Verbeke, & Schoors, 2019). The practice has been in force since the 4th century when Christianity was introduced in Ethiopia (Belwal & Tafesse, 2010; Esler, 2019). The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (EOTC) defines fasting as a sacred sacrament whereby the believers get

9

spiritually connected and seek salvation through reducing physical comfort as per Saint Paul’s Biblical guidance to “chastise the body and bring it under subjection” (1 Cor. 9:27 King James Version). During these days, believers abstain from taking any food and drink before 3.00 pm, after which their diet includes only vegan food (Belwal & Tafesse, 2010; D’Haene et al., 2019). In other words, during the fasting days, the consumption of any type of meat, including fish and animal products like egg and dairy, is strictly prohibited. The fasting counts at least half of the days in a year, although the exact number of days depends on who practice them, laymen or clergy (Belwal & Tafesse, 2010; D’Haene et al., 2019; Rogers, 2020). Unlike OC, fasting in Islam is not food-specific (Sadeghirad, Motaghipisheh, Kolahdooz, Zahedi, & Haghdoost, 2012). Instead, it is manifested by a willful renounce of any types of foods, drinks, smokes, and sexual activities from sunrise to sunset during each fasting day (Sadeghirad et al., 2012; Abaïdia, Daab, & Bouzid, 2020). Ramadan, a tribute to Nebyu Muhammad’s first revelation, is the most popular one-month fasting and practiced by all healthy and non-traveling adult Muslims worldwide (Sadeghirad et al., 2012; Abaïdia et al., 2020).

Numerical evidence on how many OCs and Muslims adhere to fasting in Ethiopia is incomplete. Nonetheless, the centuries-old footprints of the two religions on the overall social structure of the country in combination with the large number of followers have made the effect of fasting to appear explicitly on the production and consumption of some food items (Seleshe et al., 2014; Hopf, 2017; Esler, 2019). A recent national quantitative study by D’Haene et al. (2019) revealed that OC fasting has an adverse impact on milk consumption and production patterns. Not only OCs but also the followers of other religions are impacted, due to a spillover effect described in the study. Another similar study by Belwal and Tafesse (2010) came up with the same results on biscuit production and consumption.

Additionally, there is evolving evidence in academic literature (e.g. Christian et al., 2007; Maliwichi-Nyirenda & Maliwichi, 2017) that demonstrates how granted FTP in different societies can affect food security by constraining people to get essential micronutrients. For instance, in some rural areas of Ethiopia, pregnant women have no free dietary choice due to belief-based food taboos (Zepro, 2012; Zerfu, Umeta, & Baye, 2016; Mohammed, Taye, Larijani, & Esmaillzadeh, 2019). Particularly, in the central Ethiopia rural Arsi district,

10

pregnant women limit the consumption of green leafy vegetables and dairy products (Zerfu et al., 2016). In their belief, this food taboo reduces possible childbirth complications and pains through losing weight during pregnancy. However, the practice is neither encouraged nor enacted by the law. Similar studies on the impacts of food taboos among pregnant women are also conducted in Nigeria (Abidoye & Akinpelumi, 2010), Ghana (Aikins, 2014), Malawi (Maliwichi-Nyirenda & Maliwichi, 2017), and Nepal (Christian et al., 2007). Some of these research findings (e.g. Christian et al., 2007; Maliwichi-Nyirenda & Maliwichi, 2017) showed that the existing belief-based food taboos might be detrimental to the health of both the pregnant women and fetuses. This is because the taboos can prevent them from getting the proper proteins and other micronutrients.

The points covered in this section are just a few examples to emphasize the importance of the topic under discussion. However, the details on the adverse impacts of nonscientifically based FTP on food security are commonly given less attention in academic and non-academic studies in developing countries. In Ethiopia, the few existing studies related to the topic are neither exhaustive nor taking food security sufficiently into account. They mainly focused on the impacts of OC fasting on the production and consumption of certain food items such as milk (D’Haene et al., 2019), biscuit (Belwal & Tafesse, 2010), and meat (Seleshe et al., 2014). Furthermore, policy cycles aiming to enhance food security are more biased towards the technology, market, and political subjects than the food norms (Alonso et al., 2017). Therefore, this study addressed the aforementioned literature gap by investigating the adverse impact of nonscientifically based FTP on food security through collecting evidence from Ethiopia.

1.3. Research Questions

This thesis primarily intends to investigate the Ethiopian FTP and enhances our understanding of how these food norms affect the country’s overall food security expressed in terms of food availability, access, utilization, and stability. Precisely, the thesis addressed the following research questions.

▪ What are the core features and foundations of the prevailing Ethiopian mainstream food norms?

11

▪ What are the adverse impacts of food taboos and preferences on Ethiopian food security?

▪ What are the possible approaches and strategies of improving the adverse economic impacts of food taboos and preferences for the common good?

▪ What are the prospects of the mainstream food taboos and preferences?

1.4. Significances of the Study

Food norms have indescribable impacts on humans’ food patterns (Alonso et al., 2017; HLPE, 2017). The impacts are embodied in all fundamental economic activities from production to consumption (WFP, 2009). Yet, food norms have been hardly considered in the analysis of economic development in general and food security in particular (Alonso et al., 2017). Hence, the study contributes to the efforts to balance the long-standing disciplinary bias on the subject and thereby fills the existing literature gap.

In 2018, “more than 820 million people in the world are still hungry” and an even increasing figure is forecasted for 2030, which puts more pressure on achieving the “zero hunger” Sustainable Development Goal (SDG)(FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, & WHO, 2019). The lion’s share of people in hunger lives in Africa, South America, and West Asia (FAO et al., 2019), where religious and other secular cultural beliefs have a strong base in people’s livelihood (Todaro & Smith, 2015). In this context, this thesis provides valuable clues on policy measures to be taken to mitigate food insecurity concerning the food norms.

12

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. Conceptual Definitions

In this section, the study’s key concepts, namely food security, culture, religion, food taboos and preferences are conceptualized to avoid possible confusions and subjective interpretations.

2.1.1. Food Security

The meaning of food security unfolds more prominently in the international dialogue during the 1970s, although there were already some concerns and discussions about the subject in the 1940s (Maxwell, 1996). Initially, only few variables such as production and supply were used to operationalize the concept (Maxwell, 1996). However, through time the meaning of food security started to expand and became multi-dimensional. The breakthrough for the contemporary comprehensive definition of food security, the one adopted in this thesis, goes back to the World Food Summit of 1996. In the meeting, it is put forward that “food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” (World Food Summit, 1996). Based on this definition, food security comprises four essential components; food availability, access, utilization, and stability of food (FAO, 2008). Besides, humans’ ways of life or cultures, which are expressed in the form of food norms impacts each of the four components of food security (Alonso et al., 2017).

Food availability refers to whether people have sufficient and nutritious food to eat, gained either through their own production or external sources (WFP, 2009). It is particularly concerned with the production, distribution, and exchange of food items. Likewise, individuals’ and households’ ability to acquire a healthy and nutritious diet is related to food access (World Food Summit, 1996; WFP, 2009). Food availability does not necessarily guarantee accessibility nor does accessibility ensure utilization (WFP, 2009). After all, affordability, allocation, and cultural factors also affect accessibility and utilization.

Food security is maintained when the source of the food is stable. As shown in Figure 2.1, food stability affects all other components of food security. Hence, the attainment of one or

13

two of the food security components does not ensure an individual or a group to declare food security. Instead, all the four components have to be successfully maintained (World Food Summit, 1996; FAO, 2008; WFP, 2009).

Figure 2.1: A framework illustrating the relationship between the four components of food security (Napoli, 2011/12)

2.1.2. Culture

This study adopts the anthropological and sociological meaning of culture. Accordingly, culture is “people’s ways of life” (Giddens, 2002). Otherwise stated, it refers to the shared patterns of knowledge that individuals acquire from society (Tylor, 1871). As summarized from the works of anthropologists and sociologists (e.g., Tylor, 1871; Giddens, 2002; Macionis & Gerber, 2011), the best approach to comprehend culture is to review its core features. Firstly, culture is acquired and shared. Thus, it must be learned and nurtured from the society. Individuals learn culture from a combination of agents, particularly from family, school, peers-groups, mass media, and religious institutions through a lifetime process of socialization. The same applies to food taboos and preferences. It is a nurtured and shared cultural habit. Secondly, culture can be material or non-material. Food taboos, preferences,

14

knowledge, norms, values, etcetera are non-material culture whereas churches, for instance, are material. Thirdly, culture is symbolic. As such, it reflects the communal agreement of societies. In other words, societies create a particular culture and give meaning to it. In turn, the attached meaning is adhered back by the societies. Lastly, as societies’ demands constantly change, their lifestyles are also adaptive and dynamic. The magnitude of cultural change may vary, yet no culture is static (Macionis & Gerber, 2011). Consequently, societies can adjust their food norms if required by changing circumstances. Generally, culture in this study represents all the material and non-material components of societies that are acquired, symbolic, and dynamic ( Tylor, 1871; Giddens, 2002; Macionis & Gerber, 2011). Part of this is the concept of mainstream food norms, which is used extensively throughout this thesis. It represents those food norms which are explicitly practiced by the majority of Ethiopians.

2.1.3. Religion

Durkheim (1912/1961) in his classic book, “the elementary forms of the religious life”, has made the meaning of religion clear. It is also found convenient for our contextual usage. According to him, “a religion is a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say, things set apart and forbidden beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community called a Church, all those who adhere to them". Additionally, many of the religious discourses raised in this study are viewed from the Ethiopian OC and Islam religions’ perspectives.

2.1.4. Food Taboos and Preferences

The conceptual definitions of FTP adopted in this thesis are not different from their conventional meanings. Food taboos are socially or religiously based norms or laws that prohibit people to consume certain types of food (Meyer-Rochow, 2009). For the purpose of this study, temporary food prohibition that results from fasting and other normative restrictions are also considered and included in the definition. Conversely, food preference is the choice of a particular food or drink over others based on norms or laws (Smith, 2008). Otherwise stated, it is the selection of what is most important from the available and socially recognized foods. Though academic studies on the impacts of FTP on food security

15

are inadequate, the existing few are covered in section 1.2 and the core points are presented in table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Summary of the potential impacts of taken-for-granted FTP on food security

Nonsci en ti fi c ba sed FTP ma y ca u se f or:

Prohibition of easily available nutritious plant and animal species. For example, in many countries across the world entomophagy is taboo though healthy and sustainable and can be easily farmed in their nearby environment (Schuurmans, 2014; Napoli, 2011/12).

Unhealthy and unsustainable food choices. Food preference is a universal culture, (Smith, 2008). In every society, individuals and/or groups chose certain food and drink over the others. This is practiced with or without the knowledge of the health and environmental consequence. Nonscientific based food choice increases the chance of exposure to unhealthy diet (Alonso et al., 2017).

Poor food utilization. People across societies prepare and cook the same food in different forms and techniques. This has implications on food micronutrient, time of food preparation, size of calorie intake, health matters arising from a food quality, etcetera that are important variables in food security (Alonso et al., 2017). Constraining a specific group of people, often pregnant women and its fetuses from getting essential micronutrients (Christian et al., 2007; Maliwichi-Nyirenda & Maliwichi, 2017).

Hinder production and consumption of certain food and drink. For example, OC fasting in Ethiopia creates a significant reduction in milk and biscuit production and consumption (Belwal & Tafesse, 2010; D’Haene et al., 2019).

16

2.2. Theoretical Framework

A clear understanding of the impacts of FTP on food security requires the investigation of pertinent cultural and religious bases of the practice, as shown in Figure 2.2 symbol “A” and “B”. This investigation comprised the interviewing of key informants and the review of the relevant secondary sources. Incorporating the foundations of the practice in the study enhances the validity of research and promotes the identification of the study variables. In this regard, the dependent and independent variables of the thesis are food security and food taboos and preferences, respectively. Policies and programs of secular or religious institutions, which affect both FTP and food security, are the intervening variables of the study. These are displayed in Figure 2.2 symbols “A”, “B”, and “C.”

The answers to the research questions of this thesis demand the examination of the broader socio-economic, religious, and historical contexts of the country (Alonso et al., 2017; HLPE, 2017). From a sociological perspective, social structure which comprises food norms, is a patterned system of arrangements, including institutions and organizations, that regulates human actions and interactions (Schaefer, 2019). It involves all the major social institutions, namely family, religion, politics, economy, and education. Social structure also defines the norms and values of a particular society and regulates individuals’ and groups’ day-to-day performance (Schaefer, 2019). Therefore, the scrutiny of the existing social structure provides clear emic insights to comprehend the features and foundations of the Ethiopian mainstream FTP and their adverse impacts on the food security of the country. FTP and food security impact each other (Alonso et al., 2017; HLPE, 2017; Olum et al., 2017). After all, it is a general economic principle that demand determines the production of a particular food (Meyer-Rochow, 2009). In other words, producers are always inspired consumers to invest their capital in the production of an item if consumers respond positively. Hence, prohibited or low demanded food products are less likely to be produced (Meyer-Rochow, 2009). This mechanism directly impacts food security. Conversely, in times of extreme hunger and hardship, food norms can be desecrated (Schuurmans, 2014; HLPE, 2017). Individuals and groups use all available means as a response to survival. Societies may strive for temporary or enduring revision of food norms (Schuurmans, 2014; HLPE, 2017).

17

Worldwide, the search for sustainable food sources is persistent (Nutreco, 2012; FAO, 2013). Population size increases unprecedentedly and so does the search for additional foods. So far, people have relied on their ingenuity to curve the negative economic consequences of uncontrolled population growth (Todaro & Smith, 2015). The introduction of the green revolution in the mid-20th century, for example, has challenged population pessimist perspectives, or at least for a while (Todaro & Smith, 2015). Yet, the further boosting of food production through the conventional farm-intensification method is constrained, due to an acute shortage of resources and doubts on the method’s sustainability (Ritzer, 2011). The approach has been heavily criticized for causing a devastating impact on the environment and biodiversity. Hence, the quest for other sustainable dietary options is still at the forefront of global agendas (Nutreco, 2012; Mccouch, Bramel, Buckler, & Burke, 2013; HLPE, 2017). The effort goes to the extent of revising food norms. Some animals, insects, and plants which were previously defined as “disgusting” by the food norms of some societies have now started to get paramount attention (Schuurmans, 2014). This clearly illustrates the impact of food security on the broader social structure, including food taboos and preferences, as presented in Figure 2.2.

18

19

2.3. The Ethiopian Economy and Food Security

Agriculture is the engine of Ethiopia’s economy and it has a substantial spillover effect on other sectors (Cheru et al., 2019). In 2015-16, agriculture in Ethiopia contributed 36.7 percent of the national GDP, 72.7 percent of the total employment, and 90 percent of the total export (WFP & CSA, 2019). Moreover, the sector is characterized by low productivity, the dominance of family-based subsistence farmers, labor-intensive farming, high dependency on rain, and exposure to the adverse impacts of the reoccurring drought of the region (Cheru et al., 2019; WFP & CSA, 2019).

Since the beginning of the 1990s, the Ethiopian government has shown immense interest in the Asian based developmental state philosophy (Clapham, 2018). In line with this philosophy, the Ethiopian government is in control of major economic assets, including land, and plays a pivotal role in the main economic activities (Cheru et al., 2019). However, private sectors are not completely banned, as was the case under the socialist Derge Regime (1974-1987). Instead, the government encourages private sectors to engage in different economic activities, albeit few giant national projects like telecom and national aviation industries remain under the sole control of the state (Clapham, 2018; Cheru et al., 2019).

Agricultural Development Led Industrialization (ADLI) is the national economic policy targeting the countryside. It is based on the logic that a higher efficiency and effectiveness of agriculture are the safe ways for the country’s transition to industrialization. Indeed, from developed countries’ experience, technology and capital supported agricultural productivity facilitates rural transformation (Bhandari & Ghimire, 2016). In the long run, this process involves a decrease of agriculture as a factor of income and agriculture’s contribution to the national GDP, compared to industry and service sector economic activities (Arendonk, 2015). This process also holds a gradual decline in the number of people engaged in the agricultural sector (Dennis & Talan, 2007). The idea has also been discussed in the Arthur Lewis structural model, where the process is noted as an ideal opportunity to get idle labor which can in turn be used to fill the labor gap in other sectors (Todaro & Smith, 2015). However, its pertinence in developing countries has been doubted, due to a number of contextual factors (Todaro & Smith, 2015).

20

In the year 2000, more than half of the Ethiopian population used to live below the international standard poverty line of $1.90 per day (WB, 2016; Cheru et al., 2019; WFP & CSA, 2019). However, the promising macro-economic growth achieved for the last two decades has helped the country to steadily decrease this poverty figure (Cheru et al., 2019). In 2016, the percentage of food-insecure households and individuals were 20.5 and 25.5 of the total population, respectively (WFP & CSA, 2019). Despite the gradual achievement, the current national food insecurity figure remains high enough by the international standard to show the critical nature of food insecurity challenge in Ethiopia (UNDP, 2018; WFP & CSA, 2019).

21

CHAPTER THREE: STUDY AREA AND RESEARCH METHODS

3.1. Study Area: Sociocultural and Religious Overview

Ethiopia, the study site around which this thesis revolves, is also known as “land of origins.” The country is a landlocked and located in the Horn of Africa, bordering Kenya in the South, Eretria in the North, Somali in the East, Djibouti in Northeast, South Sudan in the West and Sudan in Northeast. It has a total land size of 1.1 million square kilometer and diverse geographic and climatic conditions (WFP & CSA, 2019). As of 2020, the country has a total of 114.5 million people with a 2.57 percent population growth rate, making it the second most populous nation of the African continent after Nigeria (Worldometer, 2020). Ethiopia has around eighty different ethnic groups although over 60 percent is only from the two largest ethnic groups, namely Oromo and Amhara (Adamu, 2013). Almost all ethnic groups have their own legally recognized language that they use as a mother tongue, while Amharic is the federal government’s working language.

Religion has a strong public support base in Ethiopia (Esler, 2019). Article 11 of the Ethiopian Constitution stipulates the separation of state and religion. Hence, the country is officially a secular state. Citizens are thus granted the constitutional right to religious choice, though informal pressure among family members and closer kin to perpetuate the religion of their parents is common among all religious categories. According to the Central Statistics Agency of Ethiopia (CSA, 2010), 97 percent of the Ethiopians associate themselves with one of the main religious categories, namely OC (43.5 percent), Islam (34 percent), and Protestant (18.5 percent) and Catholic Christians (1 percent). Introduced in the 4th and 7th centuries respectively, OC and Islam have played paramount roles in the state formation (Adamu, 2013). Especially, the EOTC has a strong influence on the overall socio-economic and political culture of the county. As Esler (2019) described, it is hardly possible to comprehend the Ethiopian overall history, culture, and social institutions independent of the EOTC. The Church used to function complementarily with the state for centuries until the first secular government was established in 1974 (Adamu, 2013; Esler, 2019).

22

Ethiopia is a historically rich and culturally diverse country. Sub-cultures are very common among the different ethnic groups (Adamu, 2013; Hopf, 2017). Group life is highly valued, which goes at the expense of individualism. In fact, strong solidarity is essential to people’s livelihood strategy in the country. in relation with this social cohesion, norms are very powerful, particularly in the countryside (Hopf, 2017). Religion is plays a catalyst role in ensuring that people are still connected to each other and adhered to the shared core spiritual values. So, in practice, there are no clear cut boundaries between religious and non-religious lifestyles (Esler, 2019). After all, many of the country’s secular cultural components originate from EOTC influence (Hopf, 2017; Esler, 2019). There are many religious and secular rituals and holidays the people attend and express their religious and/or secular value, honor, and sentiment (Esler, 2019; Hopf, 2017). The country’s ability to maintain its sovereignty during colonial times has granted an opportunity to safeguard many of its indigenous knowledge (Adamu, 2013; Hopf, 2017).

3.2. Research Design

3.2.1. Research Methods

Almost all the research questions depicted in section 1.3 demand an understanding and description of thoughts, experiences, and concepts. Also, the topic of the thesis is tangled to the society’s socio-cultural and religious variables. Accordingly, it requires rich data to properly address the thesis’ ultimate objective. In a study of the aforesaid features, as (Taylor, Bogdan, & DeVault, 2016; Flick, 2018) stated, qualitative research is more appropriate than quantitative study.

Therefore, this exploratory study employed a cross-sectional qualitative research design, with semi-structured in-depth interviews as the main method of data collection. Cross-sectional design, means that the data are collected at a single point in time (Payne & Payne, 2004). Hence, this research did not examine the over-time changes of the subject, as is the case in longitudinal studies. Specifically, in-depth interviews were used because of the relative flexibility of the method (Wertz, Charmaz, McMullen, Anderson, & McSpadden, 2011). In-depth interviewing enabled both the researcher and interviewees to thoroughly

23

discuss the themes in one-to-one interviews (Rubin & Rubin, 2004). In addition, the study was supplemented with pertinent research findings and reports cited from academic books, journal articles, web-pages, and governmental and non-governmental reports. Reliable information and research findings obtained from these sources were combined with the primary data to substantiate and enhance the analysis and discussions.

3.2.2. The Selection of Samples

Primary data were collected from 11 key informants who are different stakeholders, experts, and decision-makers that can properly judge the ongoing issues. The selection of the samples was done by the researcher in between December 13, 2019 to January 25, 2020. To identify the right units of analysis, all the key informants were purposively selected based on professional experience, educational background, and international exposure criteria. Because Ethiopian food norms are related to religion, culture, history, and traditional belief (Belwal & Tafesse, 2010; Hopf, 2017: Esler, 2019), the samples were chosen from various multidisciplinary backgrounds, see table 4.1. All the key informants were from Ethiopian origin and the majority used to live in the national capital, Addis Ababa. The sample size was determined based on the level of data saturation, though a balance is made to include key informants from all the aforesaid selection criteria.

3.2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

The detailed primary data were collected virtually from mid-February 2020 to the end of May 2020. Prior to the in-depth interviews, the researcher had prepared an interview guide to maintain the flow of the interviews and avoid missing points. Besides, during the in-depth interviews, a probing technique was used for clarifications and further elaboration of the subject under discussion. For convenience, the interviews with the key informants were administered in Amharic, which was the language of choice of the key informants. On average, the in-depth interviews with each key informant took around 50 minutes. Later, the interview results were thematically sorted in English based on the saved audio records and notes. Finally, the arranged data were analyzed and discussed based on a qualitative content analysis technique.

24

3.3. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Thesis

As part of the global community, I have been in one of the most life-threatening situations of our time due to the pandemic caused by COVID-19. Since the start of the lockdown in Belgium, March 2020, I was in intense frustration and depression resulting from panicking, loneliness, and concerns about post-COVID-19 economic and social crises. The thesis could have been more interesting without this challenge though all the necessary actions are taken to maintain its basic quality.

Some of the preplanned research methods and the approach of data collection were readjusted due to COVID-19. Initially, Focus Group Discussion (FGD) was part of the plan along with in-depth interview research method. However, it was not performed. To fill the gap, additional supplementary pertinent literature sources were reviewed and included in the thesis.

Furthermore, the intended face-to-face interviews with key informants were rearranged into one-to-one virtual communications. This was done via WhatsApp, Skype, and Messenger calls.

25

CHAPTER FOUR: PRESENTATION OF FINDINGS

4.1. Characteristics of Interviewees

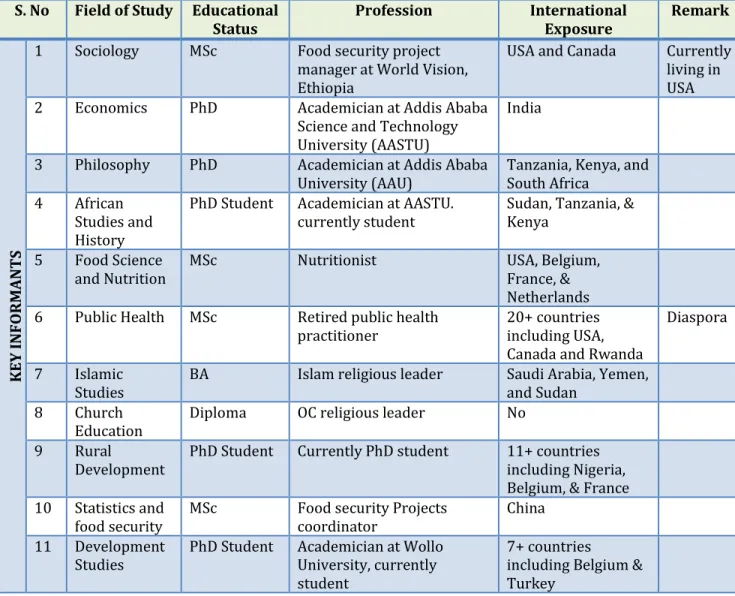

The key informants or research participants were selected from interdisciplinary backgrounds such as economics, sociology, African studies (history), philosophy, nutrition, development studies, rural development, and food security. Four from the key informants are currently working in Ethiopian public higher education institutions such as Wollo University, Addis Ababa University, and Addis Ababa Science and Technology University. In addition, two religious leaders, one from OC and one from Islam, are among the key informants.

Table 4.1: The characteristics of the key informants or interviewees

S. No Field of Study Educational

Status Profession International Exposure Remark

KEY

INFO

RM

A

NTS

1 Sociology MSc Food security project

manager at World Vision, Ethiopia

USA and Canada Currently

living in USA

2 Economics PhD Academician at Addis Ababa

Science and Technology University (AASTU)

India

3 Philosophy PhD Academician at Addis Ababa

University (AAU) Tanzania, Kenya, and South Africa

4 African

Studies and History

PhD Student Academician at AASTU.

currently student Sudan, Tanzania, & Kenya

5 Food Science

and Nutrition MSc Nutritionist USA, Belgium, France, &

Netherlands

6 Public Health MSc Retired public health

practitioner 20+ countries including USA, Canada and Rwanda

Diaspora

7 Islamic

Studies BA Islam religious leader Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and Sudan

8 Church

Education Diploma OC religious leader No

9 Rural

Development PhD Student Currently PhD student 11+ countries including Nigeria, Belgium, & France 10 Statistics and

food security MSc Food security Projects coordinator China

11 Development

Studies PhD Student Academician at Wollo University, currently student

7+ countries

including Belgium & Turkey

26

4.2. The Features and Foundations of the Ethiopian Food Norms

From the virtual one-to-one in-depth interview, all key informants conferred the existence of diverse food norms in Ethiopia that are manifested in the forms of eating habits, food preparations, food taboos, food choice, food preparation, etcetera. According to them, some of these food norms among different ethnic groups contradict each other. In substantiating this claim, the sociologist key informant said about the food taboo differences among ethnic groups: “camel meat is very common and socially honored food among the Ethiopian Somalis and Afar. However, it is taboo in other parts of the country.” In relation to the topic, the economist key informant added: “the Gumuze and Gambela people eat different wild plants and animals which are not common among the wider public in other parts of the country.” Evidently, Ethiopia is a diverse country and the variation in food norms is also clearly addressed in existing literature (e.g., WFP & CSA, 2019).

Conversely, all the key informants disclosed the presence of mainstream food norms, uniformly practiced by the majority of Ethiopians. According to the historian key informant, “the mainstream food norms prevail in wide areas, though dominantly among the people in the North, Center, and major cities of the country, including in the national capital, Addis Ababa.” Verified examples put forward by the key informants to illustrate the widely practiced food norms regarding food consumption among most Ethiopians are the use of hand for meal and food sharing.

Ethiopians are known for using a hand for eating (Chandra, 2018). It is one of the widely practiced mainstream food norms passed through generations. As a rule of thumb, neither the left hand nor the use of two hands is allowed. So people only use the right hand. The use of the left hand for eating is defined impolite in multiple societies, and so also in Ethiopia (Alhassan, 2018). However, a few deviants exist mainly for circumstantial reasons, such as physical disabilities. The use of hands for eating is practiced by Ethiopians with honor and integrity at home, and in public cafeterias, restaurants, and hotels. As the key informants revealed, washing hands both before and after a meal is also part of the tradition, although not practiced by all people. Especially in the countryside, people may not adhere to it because they lack access to water and have limited awareness on the health detriments, according to the sociologist key informant.

27

Figure 4.1: using hand in eating Ethiopian cuisine (Jeffrey, 2019)

The other common food tradition in Ethiopia is the social character of sharing a meal (FAO, 2011). Ethiopians share food in a communal plate covered with injera, the flatbread Ethiopian food made from staple cereals, most often from teff, through a fermentation process (FAO, 2011). Thus, family members, peers, and kin often eat together, sitting around the table. Sharing with strangers is common during holidays and social gatherings, such as weddings and funerals. During the meal, gursha (feeding each other with hand) is an expression of love and friendship.

Figure 4.2: Ethiopians sharing meal in a communal plate at Yoda Abyssinia restaurant, Addis Ababa (Tyson, 2020)

28

As Seleshe et al (2014) described, the Ethiopian mainstream food norms are strict and specific, in the sense that they are unambiguous and have a strong acceptance and governing powers. Many sources of food, for example, from animals, such as pigs, wild animals, birds, numerous seafood, horses, donkeys, insects, etcetera, are available in the country but are strictly prohibited by the mainstream food norms (Seleshe et al., 2014). Likewise, an assistant Professor in AAU, Department of Philosophy said “the existing food habits are indigenous and have tight normative guidelines. They are also stable and many people hardly deviate from the already defined normative restrictions.” These features of the mainstream food norms are revealed consistently by almost all the interviewees without contradiction. In answering why the mainstream food norms are strict, the key informants have provided different but complementary causal factors.

The first and the most widely mentioned reason is the historic and continued influence of religion in the overall ways of life of Ethiopians. According to many key informants, mainstream food norms cannot be viewed independently of the EOTC. For them, it is where many of the food norms’ rationalities and strengths are embedded. For example, pork, and donkey and horse meat is a strict taboo in Ethiopia because of the EOTC and Islam religious bans. As mentioned in section 1.2 and 3.1, Christianity in Ethiopia is a centuries-old practice. The nation is one of the oldest in the world in adopting Christianity (Esler, 2019). Since its first adoption in the fourth century, the EOTC and the state functioned together (Adamu, 2013; Esler, 2019). The first secular government of Ethiopia was established with the socialist Derge Regime in 1974 (Adamu, 2013; Esler, 2019). Before 1974, the top-down state apparatus was used by the EOTC to reach people and implement the Church’s commandments, including comprehensive food norms, such as the tradition of fasting. According to the historian, sociologist, and OC religious leader key informants, this prolonged influence of EOTC in Ethiopia has made the food norms to be institutionalized and extended its influence even among non-OC followers. Besides, the EOTC fully adheres to the Old Biblical Testament which is not the case in some other Christian Churches, thereby affecting on food norms. As the OC religious leader key informant formulated it:-

The Old Testament Biblical verses regarding food are still binding in EOTC. But, this is not the case for some Christian Churches which emerged in later years as a result of differences in Biblical interpretations. Unlike the EOTC, the new Christian Churches do not put religious

29

restrictions on food. They believe that the food commandments in the Old Testament are no more binding with the revision in the New Testament.

The second reason, which is related to the first, is the strong piety of the people, specifically in relation to fasting. As covered in section 3.1, around 97 percent of all Ethiopians (63 percent Christians and 34 percent Muslims) are believers (CSA, 2010). Although quantitative studies on the degree of religiosity of the people in Ethiopia are largely absent, many key informants have expressed the religiosity of the people in the strongest possible terms. “Religion is everything for the majority of Ethiopians. It is inexpressibly integrated into people’s thoughts and daily actions. Whatever comes from the religious institutions, many believers take it for granted”, said one of the academician key informants at AAU.

Figure 4.3: Ethiopian OCs (on the left) and Muslims (on the right) attending Meskel, the finding of the true cross, and Ed al-Adha religious festivals, respectively, in Addis Ababa

(Negesse, 2017)

Three key informants explained the distinctive feature of Ethiopian food norms in relation to the country’s unique historical context, which is the third explanatory factor. With regard to colonialism, Ethiopian history differs from many other African countries (Adamu, 2013). One of the consequences of colonialism is foreign cultural imposition (Ranger, 1993; Rutazibwa & Shilliam, 2018; Mudimbe, 2020). The forced expansion of the lifestyles of the colonial metropoles went at the expense of indigenous languages, ways of life, and beliefs of many pre-colonial African societies (Ranger, 1993; Rutazibwa & Shilliam, 2018; Mudimbe, 2020). However, this is not the case in Ethiopia. After all, Ethiopia has never been officially

30

colonized and the country was only briefly occupied by Italian invaders (Adamu, 2013; Hopf, 2017). Among other reasons, this sovereignty has contributed to maintaining the long-lasting indigenous food norms. The historian key informant clarified it as follows:-

Ethiopia has neither been colonized nor exposed to direct foreign cultural impositions in its history, except the five years Italian occupation. This has enabled many of its indigenous knowledge, religious, and traditional lifestyles including food taboos and preferences to perpetuate for long and remain institutionalized.

The last reason is associated with the dominance of rurality, taken-for-granted beliefs, and the low literacy rate of adults in the country. Around 85 percent of Ethiopians live in the countryside with little exposure to science and modern life (WFP & CSA, 2019). People are highly dependent on granted traditional beliefs and religious thoughts to determine about their food habits. As the health practitioner key informant

explained:-In conditions where people have limited exposure and knowledge on healthy diets and proper utilization of available foods; they depend on the traditional ways of doing things. This is practical among Ethiopians in the countryside. Their knowhow concerning what to eat, how to cook, and what to improve emanates from religious and ancestral knowledge passed through generations.

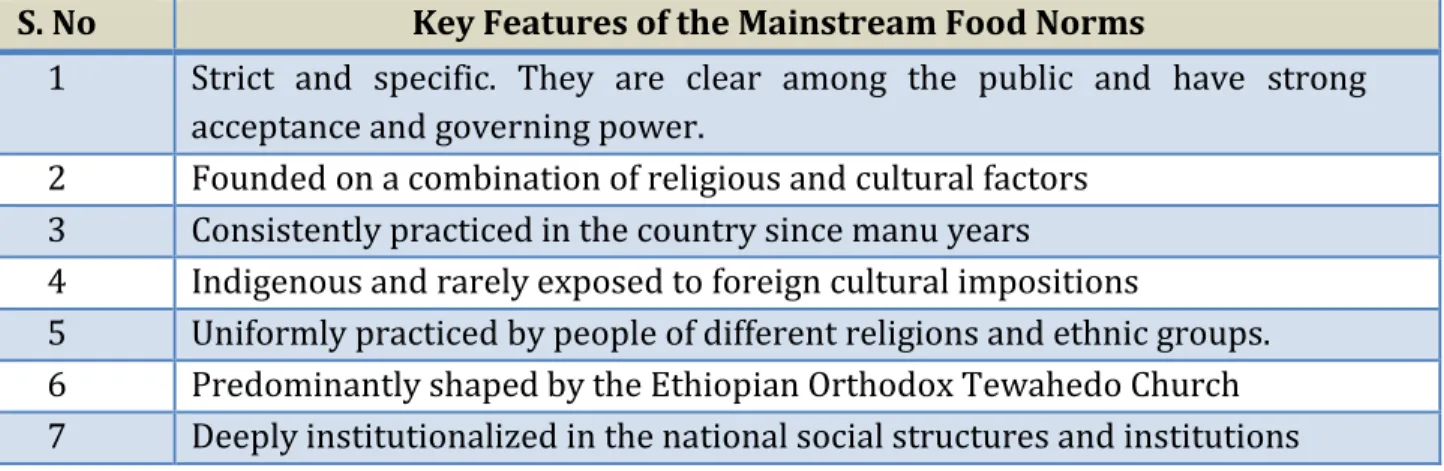

Table 4.2: Summary of the basic features of the Ethiopian mainstream food norms S. No Key Features of the Mainstream Food Norms

1 Strict and specific. They are clear among the public and have strong acceptance and governing power.

2 Founded on a combination of religious and cultural factors 3 Consistently practiced in the country since manu years

4 Indigenous and rarely exposed to foreign cultural impositions

5 Uniformly practiced by people of different religions and ethnic groups. 6 Predominantly shaped by the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church 7 Deeply institutionalized in the national social structures and institutions

31

4.3. The Mainstream Food Taboos and Preferences

4.3.1. Food Taboos

From the evidence collected, it is clear that within the mainstream Ethiopian food norms, food prohibitions or taboos are expressed in different forms. The first and most common are unconditional food taboos. These taboos represent those foods, which are completely banned from the country’s mainstream food menu through existing norms for religious or secular reasons. Examples include pork, donkey and horse meat, and seafood except fish. A second type are conditional food taboos. According to the key informants some foods can remain in the taboo lists unless they fit into the religiously and/or culturally defined normative standards. One notable example is the need to pray before slaughtering edible animals. “Religiously permitted animals have to be consecrated based on the religion’s tradition to be part of the diet. Otherwise, they remain in the taboo food lists”, said the OC and Muslim religious leader key informants. Consequently, Ethiopian OCs and Muslims do not share meat-related dishes. Alternatively, the vast majority of Ethiopians prefers to buy living animals and bless them in their homes. In a further clarification the sociologist key informant said:-

Buying chicken, sheep, and goat meat in supermarkets or other groceries is considered an act of dishonoring the tradition, especially in the countryside. Eatable animals have to be blessed at home. It is one of the most valued rituals of meat consumption among Ethiopians.

Fasting based abstinence is the third type. During Ethiopian OC and Muslim fasting days, what to eat and when to eat are precisely defined by the dogmas of each of the religion as described in section 1.2. For instance, OCs fast at least half of the days in a year, fragmented in different days and seasons. This includes almost every Wednesday and Friday, and the 55 consecutive days of Lent fasting before Easter. During all these and other fasting days, OC believers abstain from taking any food or drink before 3.00 pm, after which their diet includes only vegan food (Belwal & Tafesse, 2010; D’Haene et al., 2019). Similarly, during Ramadan, (Ethiopian) adult and healthy Muslims abstain from foods, drinks, smokes, and sexual activities from sunrise to sunset for one month (Sadeghirad et al., 2012; Abaïdia, Daab, & Bouzid, 2020). Ramadan is the most popular one-month fasting and practiced by all healthy and non-traveling adult Muslims worldwide, including Ethiopian Muslims

32

(Sadeghirad et al., 2012; Abaïdia et al., 2020). According to the OC and Muslim religious leader key informants, deviation from these spiritually defined fasting in both religions is equally as condemned as eating taboo foods.

4.3.2. Food Preferences

From the interview, it is found that religion, culture, and commonly held public perceptions mark the boundary between taboo and non-taboo foods. Scientific or health-based perspectives have limited influence on people’s food preferences. Alien and taboo foods are hardly seen on any of the mainstream food menus. The exceptions are a few high-class hotels and restaurants, which have international customers and thus offer foreign foods and cuisines that are not indigenous and often unfamiliar to the majority of Ethiopians. The interviewee from rural development discipline underlined:-

Many people are scared to move beyond the psychologically and culturally drawn mainstream food wall. Food venture and scientific analysis of the nutritional content of the food are not common among the general public. The exceptions are some Ethiopian Diasporas, few educated people, and sick people with medically defined food prescriptions.

From the socially recognized food lists, people’s daily choices are made based on palatability, accessibility, and income levels. As the sociologist key informant describes it:-

If not constrained by economic limitations, the consumption of meat with alcoholic drinks is the dream food choice for most Ethiopians. Consumption of meat is an expression of high economic and social class which is an extension of centuries-old Ethiopian royal families’ food choices. Conversely, the poor are pushed to different types of staple vegan foods such as grains, cereals, pulses, and some vegetables and fruits.

According to the diaspora key informant, “the rich-poor food categorization in Ethiopia is in favor of the poor. The poor eat healthy organic vegan food, which are scientifically recommended, whereas the rich mostly consume meat, dairy products, and too many alcoholic drinks.” The relatively low price of vegan food compared to non-vegan foods in the country has made the rich-poor food classification to appear as described above. “The cause for the high price of meat and dairy products in the country is the acute shortage of supply,” said the economist key informant.

33

As noticed from the interviewees’ response, seasons, stereotypes, lack of awareness, and misconceptions are also among the factors which influence food preferences. It is also noted that summer and spring are relatively the most challenging seasons for many subsistent farmers in Ethiopia. They face chronic food shortages and have very limited food choices. Conversely, in autumn and winter after the farmers start to collect the fruits of their harvest, they have relatively diversified diet.

Furthermore, since a long time, stereotypes and beliefs have been preventing Ethiopians from the consumption of certain types of edible plant and animal species, as revealed by five research participants. According to the sociologist key informant:-

People in the South are heavily dependent on different types of tubers, leaves, and other plant species. This is the result of the rich biodiversity of the region and the easy accessibility of the plants. But, eating of some of these vegan foods has been negatively stereotyped, though the labeling is decreasing gradually.

In addition to this point, the nutrition key informant said: “still today some people in the North associate goat meat with bad spirits which can cause sickness.”

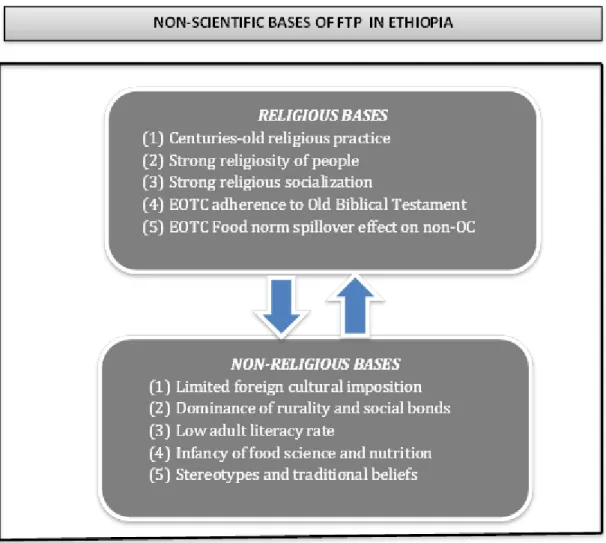

Based on the theoretical framework developed in section 2.2, the foundations of the Ethiopian mainstream FTP are summarized in Figure 4.1 below.

34

Figure 4.4: Religious and non-religious bases of Ethiopian FTP

4.4. The Impacts of food Taboos and Preferences on Food Security

The interviewees were asked to describe and explain the adverse impacts of the prevailing FTP on the country’s food security. I begin the analysis from the response of the economist key informant who stated the following about fasting: “the core concept of fasting is abstinence from food and drinks. In a basic economic view, if there is no consumption, there will not be production. Hence, the entire food supply chain from production to consumption will be adversely impacted.”

OC fasting is food-specific (see section 1.2). It bans meats and other foods of animal origin. Thus, during fasting days, the consumption of prohibited foods and drinks significantly drops in many parts of the country. The subject is consistently discussed in detail by some scholarly studies (e.g., Belwal & Tafesse, 2010; Seleshe et al., 2014; Hopf, 2017; D’Haene et

35

al., 2019). According to the key informants, to maintain the profit, some companies limit the production of less demanded foods and drinks. Others divert their businesses to vegan food. Elaborating on the situation, the key informants in Addis Ababa University stated:-

During OC fasting days, many local and village butchery and dairy shops and some restaurants temporarily close until the fasting is over. Some others divert to the provision of vegan products. Non-fasting people including the followers of other religions would have very limited access for the band foods due to shortage of supply. OC owned shops who fail to adhere to the church’s command can lose customers in non-fasting days as part of the public informal social control sanctions.

Some key informants do not confine the adverse economic implication of fasting to the reduction of consumption. “The booms and busts on the consumption of certain products can have a discouraging effect on the country’s attempt of attracting local and foreign investors in the sector,” said the economist key informant. He also added that the economic consequences of OC fasting can be worse on easily perishable products like meat, milk, butter, yogurt, and others. According to FAO (2019b), with over “57 million cattle, 30 million sheep and 23 million goats, and 57 million chicken, as well as camels, equines and a small number of pigs”, Ethiopia is among the top-ranked African countries in livestock population. However, the meat and dairy supply-chains are very poor and not developing (FAO, 2019b; Abebe, Zelalem, Mitiku, & Yousuf, 2020). The sector is not a preferred business by local and foreign investors. “Throughout Ethiopia, including the urban regions like Addis Ababa, dairy is mainly distributed and consumed in a traditional way” (Soethoudt, Riet, Sertse, & Groot, 2013). Among other reasons, this is due to the market constraints that are often caused by fasting-induced inconsistencies in demand and supply (D’Haene et al., 2019). The few existing dairy and meat prosing plants in the country are largely concentrated in the national capital, Addis Ababa (Abebe et al., 2020).

Likewise, the impact of OC fasting on the price and supply of substitutive vegan foods has also been conferred by the research participants. According to the economist key informant, “the price of vegan foods increases as a result of high demand during OC fasting days. The demand increases because vegan foods are the major substitutive of non-vegan fasting foods. Hence, a shortage of supply in vegan foods is created, and this is a common experience in many parts of the country.” From the sociologist key informant viewpoint, OC

36

fasting has also a spillover effect on the consumption of some vegan foods, particularly on alcoholic drinks. As he puts it, “many people in Ethiopia drink alcohol after they eat protein-rich foods, commonly meat. Thus, the consumption of alcohol goes down during OC fasting.” The fasting wave of influence can go broader. As the diaspora key informants stated, “economic sectors are interdependent. When one sector is affected, there is a high possibility to see ripple effects on other sectors.”

Muslims’ fasting has also economic outcomes. According to the interviewees, it encounters a decline in business transactions but in a different form than stated for OC fasting. The details are explained by a key informant in AAU of the department of philosophy:-

Muslims’ fasting is followed by abstinence from all form of foods and drinks for half of the hours of each fasting day, from sunrise to sunset. This reduces consumption. Although shops remain open there is some unevenness in opening and closing hours among Muslim owned businesses.

Fasting is one of the religious rituals, supposed to be practiced on the individual believer’s free will. However, the result of this study reveals the existence of strong informal societal pressures on non-fasting OCs and Muslims. It is reported by all research participants that many of the informal pressure comes from family, peers, neighbors, and church leaders. “This is one of the manifestations of the strong value of religion and social bond among people in the country,” said the sociologist key informant.

Abstinence from food and drinks for some hours is part of religious commitment during fasting days. The interviewees have provided contrasting views on its socio-economic and health implications. While the OC religious leader key informant said, fasting gives people spiritual and psychological satisfaction and inspires them for work; a nutritionist expert came up with a different view. According to her:-

To my knowledge, elderly people, some children, pregnant women, and people with preexisting medical cases also involve in fasting. These are people who need special dietary care. I also know some people who ignore their medical prescriptions during fasting days, exposing themselves to poor health conditions.