1

EXILE AND IMPRISONMENT: CRIMINALISING

REPUBLICAN POLITICAL DISSIDENCE IN SPAIN

Masterproef neergelegd tot het behalen van

de graad van Master in de Criminologische Wetenschappen

door 01605851 Souvenir Gema

Academiejaar 2019-2020

Promotor :

Commissaris :

prof. dr. Petintseva Olga

Schapansky Evelyn

2

Abstract

The Spanish-Catalan conflict has reached heated peaks over the past years, in which Catalan politicians, artists, activists and citizens have been prosecuted, incarcerated and exiled. Academic research on the conflict largely encompasses law studies and the question concerning legality of the 2017 referendum on auto-determination of Catalonia. This research goes beyond strict questions of legality and provides a critical criminological contribution and emic perspective on the conflict as experienced by people on the front line by means of a participatory action research (PAR). Their heterogenous visions on possible solutions are presented. Research results expose an institutional will to intertwine civil disobedience and republican political dissidence with terrorism, rebellion and sedition, in which the Spanish state violates fundamental freedoms of expression and the right to protest. Despite the alarming political crisis, the EU has not interfered nor negotiated possible solutions, labelling the situation as an internal issue for the Iberian country.

3

Preface

This master’s thesis was conducted in order to obtain the degree in Criminological Sciences at Ghent University. I want to thank prof. dr. Olga Petintseva, my promoter, for showing interest in the topic and giving me feedback throughout the course of the inquiry. I also want to thank all the people in Catalonia and Brussels who participated in this process. Even though I would like to give individual credits in this preface, deontological considerations concerning anonymity do not allow me to do this. To all of you: Moltíssimes gràcies a tothom, no hauria estat possible sense vosaltres. Muchas gracias a

4

Content

Abstract ... 2 Preface ... 3 Content………4 1. Introduction ... 5 2. Theoretical Framework ... 62.1 Critical criminology and the culture of crime ... 6

2.2 Positionality and role of the critical researcher ... 7

3. Methodology ... 8

3.1 PAR versus Covid-19 ... 8

3.2 Practical aspects and data-analysis ... 9

4. Catalonia and Spain: a history of disagreement... 10

4.1 From civil war to dictatorship ... 10

4.2 Amnesty and oblivion ... 12

4.3 l’Estatut: catalyst for the revival of a new wave of separatism ... 13

4.4 Referendum of 1-O 2017 ... 14

4.5 Excesses of the Spanish impediment to uphold the 1-O referendum ... 16

4.6 Legality, legitimacy and critical views ... 17

5. Criminalising political dissidence ... 18

5.1 “If you see us running, run with us!” ... 18

5.2 Involvement in politically dissident groups ... 20

5.2.1 Police violence ... 22

5.2.2 Judicial charges ... 22

5.2.3 Opinions on the Spanish state ... 24

5.3 Auto-justifications: why keeping up the struggle? ... 26

5.4 Europe’s non-response and solutions to the conflict ... 27

6. Conclusion and discussion ... 31

Bibliography ... 34

Appendix ... 39

I. Press Release ... 39

II. Preambule: the impact of Covid-19 on methodological considerations ... 40

5

1. Introduction

“Resistance; if nothing else, it’s a gut-level refusal to bow down and submit. Resisto ergo sum. For anyone who identifies as “critical” or “progressive” or “radical,” this existentially visceral revolt seems an especially necessary stance—an approach usefully animating everyday interactions with authorities and authoritarians, legal or academic or otherwise. For that matter, critical criminology, as a whole, seems constituted around resistance, operating as an ongoing act of intellectual and political opposition to the criminal justice industrial complex and a scholarly subversion of those academics and academic structures that legitimize it.” (Ferrell, 2019)

As critical criminologist Jeff Ferrell (2019) states: “I resist, therefore I am”. It was inspired by Ferrell’s work on resistance – combined with a strong belief that legality does not equal legitimacy nor legitimacy equals legality – that I conducted this research. As a critical criminologist it is a duty to speak out against social injustices and to resist rigid authorities that instead of dialoguing, opt straight for excessive state repression. Referring to Ferrell (2019), resisting something or someone does not necessarily dismiss the person or institution the resistance is aimed at for the mere fact of having a different idea, however it subverts that person or institution for repressing, defining and controlling the other.

The goal of this master’s thesis is to shed a light on the emergence and subsequent criminalisation of political dissidence, civil disobedient movements and resistance in Catalonia, following the Spanish-Catalan conflict which has reached heated peaks over the past years resulting in prosecuted, exiled and imprisoned politicians and citizens. In concrete terms, it examines how everyday forms of resistance against authorities that are perceived as unjust are criminalised. Instead of focussing on Catalan political elites, the protagonists of this research are everyday people who find themselves in the midst of a political crisis, risking their freedom by speaking their minds. On a macro level, this research aims to expose processes through which powerholders in higher state structures criminalise pacific, non-violent civil movements by creating legal frameworks and a discourse in which repression and even violence against political opponents is justified.

Little academic research was found concerning contemporary political dissident movements engaging in civil disobedience in Catalonia. Research on the current conflict mainly came from the area of law studies and encompassed strict legal analyses of the legitimacy of the 2017 referendum on auto-determination, questioning whether this was legal or not. With this research I aim to contribute to the academic knowledge on the topic from a critical criminological perspective, freed from strict legal interpretations yet endorsing social justice.

6 Through participatory action research (PAR), this thesis aims to give a voice to people repressed in the conflict. Five research questions were formulated in order to sketch the criminalisation of Catalan republican political dissidence in contemporary Spain:

1. What is the socio-historical context which led to the current outburst?

2. How does the state react towards groups who endanger the established hegemony? 3. What are the effects of state repression?

4. What are the motives of those who engage in civil disobedient movements willingly, knowing the risk of possible prosecution?

5. How should the international community react towards the recent events according to those who feel repressed?

Several topics are tackled throughout this article, starting by the theoretical and methodological framework. Due to the importance of the historical context in order to understand the current conflict, a timeline is given in which essential historical events are highlighted. Once the historical context to the Spanish-Catalan issue has been outlined, the results of the empirical research are presented subdivided into various relevant topics. I subsequently proceed to auto-justifications of individual civil disobedience and participants’ perceptions on the international reaction to conclude with possible solutions to the conflict.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1 Critical criminology and the culture of crime

This inquiry was conducted parting from a critical-emancipatory paradigm. The critical emancipatory paradigm became closely associated with the Frankfurter School, where critical theory acquired a renewed potency as a philosophy employed to question modern society (Devetak, 2005). Critical criminological research entails a specific focus on power relations and inequalities, in this case bottom-up civil disobedience and republican political dissidence of Catalan society and top-down criminalisation of this civil disobedience by Spanish authorities. The essence of critical criminology can be compiled in eight principles: (1) The control and repression of crime is not neutral and thus a politically charged activity that protects the economic interests of those who hold power, (2) crime has no ontological reality, “crime” does not exist and actions that are labelled as crime are very diverse, (3) in studying crime, the critical criminologists’ focus lays on broad social injustices and structural inequalities, instead of the offender’s underlying pathologies, (4) attention must be given to the social reaction on crime and to power relations (Decorte, Jespers, Petintseva, & Tuteleers, 2016). Additionally, the labelling perspective takes a primordial place within critical criminology: (6) illusions and stereotypes about crime can be real in their consequences, this can be linked to the self-fulfilling

7 prophecy (7) certain labels such as “the criminal” produce stereotypes which hold the entire system together and (8) secondary harm emerging from interventions to control certain primary harms are often more serious than the initial harm itself (Young, 2002).

Critical criminology could best be perceived as an umbrella term encompassing many other perspectives which emerged from it. One of these sub-currents is cultural criminology, which aims to place crime and crime control in the cultural context (Hayward & Young, 2004). Talking about “culture” in cultural criminology suggests the search for meaning. Culture can be interpreted as those concepts which have a collective meaning and the collective identity of a particular society of whose national symbols legitimise a group identity (Dowling, 2019). In addition thereof, culture is an instrument which maintains public order in a society (Ferrell, Hayward, & Young, 2008). Important insights can be extracted about certain communities by analysing what is being criminalised and how crime is reacted to. The question thus is what the cultural significance of crime is and what it tells criminologists about a certain society, since crime is nothing but a normal expression giving meaning to society (Schuilenburg, Siegel, Staring, & Van Swaaningen, 2011; Dekeyser, 2012; Oude Breuil, 2011).

Lastly, it is important to address the conceptualisation of civil disobedience, standing for deliberately breaking the law and/or not following instructions ordered by a government by a certain group out of political reasons. It is a public action of collective protest, which is technically illegal, yet morally justified (Marcone, 2008). A central characteristic of any act of civil disobedience, is that it parts from a non-violence ideology. By acts of civil disobedience in a democratic constitution, a certain group opposes a legally established democratic authority (Rawls, 2013).

2.2 Positionality and role of the critical researcher

The critical researcher focuses on critically analysing social reality, exposing existing power relations and inequalities, how those are sustained and the consequences thereof. The critical researcher does not believe in a value-free social reality and takes sides. This critical position is not merely adopted with regard to the subject(s) of research, but also with regard to oneself and the own position within the inquiry, as critical criminology is characterised by its insistence on self-reflection (Devetak, 2005).

Self-reflection about my own role as a researcher was a continuous process during the inquiry that wasn’t precisely conflict-free. In this particular case, due to my own background being raised in a Catalan family I considered myself as an insider up to a certain level, thus doing research in a cultural entity of which I am a member of. A major benefit of conducting research in the own cultural group was the removal of any language barrier, knowledge on the topic and other historical and cultural aspects. However, having an insider position during interviews often led to certain assumptions of participants on my knowledge, resulting on a lack of elaboration on a topic without me asking for

8 further explanation. For example when addressing what being a CDR member entails in terms of goals and visions – which will be tackled later – because even though I am an insider in a certain way, I am not a CDR member nor participated in their activities before getting in touch with them. This emphasizes the importance of recognising that being an insider does not naturally leads to intimate knowledge on distinct situations and experiences of other members of the same cultural entity (Kanuha, 2000) and that the category of insider is quite complex and depending on personal factors (Meyers, 2019).

3. Methodology

3.1 PAR versus Covid-19

The nature of the research questions (supra p 6) led to a preference for qualitative methods. The best option to tackle this sociocultural conflict resulted to be a participatory action research (PAR) with an accompanying literature study. However, the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic had severe methodological consequences during the course of the inquiry. The original predefined and elaborated methodology, namely participatory action research (PAR), had to be stopped abruptly. A major restriction to the research is that two crucial aspects, namely observation and participation, were made impossible. However, initial observations had been made a few weeks before the lockdown. Nonetheless, these observations are limited as local field research in Catalonia had to be reduced to one week instead of approximately six weeks over a period of six months.

The idea behind conducting a participatory action research (PAR) was motivated by the need for an emic perspective and the creation of a clear image of circumstances and experiences of the involved participants. Being able to understand people from their own frames of reference is primordial in critical research (Taylor, Bogdan, & DeVault, 2015). PAR has been designated to address controversial issues, in this case the Spanish-Catalan conflict, partly due to the emphasis of this research method on participation and social change as part of the research process (Minkler, et al., 2002). Action research has no prescribed methodology and thus tends to be methodologically eclectic (Small, 1995). However, some requirements can be identified concerning the researcher’s role in PAR, such as the need for the researcher to participate into democratic processes and engage in morally committed action (Carr, 2011). Carr (2011) additionally states that the researcher actively works together with the participants of the study and by doing so recognises the goal of improving the situation of the repressed group. Therefore, action-oriented research is an approach of social research where the researcher tries to bring change in the established system while generating critical knowledge about it (Small, 1995).

Regardless of the circumstances, attempts were made to follow the proposed methodology as fully as possible. The critical emancipatory perspective was maintained and consequently the preference for

9 qualitative methodologies, resulting in a shift to semi-structured, in-depth interviews through online platforms. Depending on the participant, my own self-positioning and the specific information needed, the conducted interviews were doxastic, looking-glass interviews or combinations thereof. In doxastic interviews, the interviewer takes a listening role while mainly focussing on the interviewees’ experience practices, work, facts or events by non-directive questions trying to obtain long and elaborate answers, unlike during looking glass interviews in which the researcher has a dynamic position and is a peer (Petintseva, Faria, & Eski, 2020). Regardless of methodological changes, both dimensions of participation and observation were somewhat encountered by long-term contacts and updates of participants throughout the course of the inquiry and a small-scaled netnography. Netnography encompasses – amongst others – online participation, interviews, online observation and data scraping (Kozinets, 2019).

3.2 Practical aspects and data-analysis

The data-analysis was carried out through coding of transcribed interviews, livestream debates and through thorough analysis of field notes from initial observations dating from early 2020. Due to the change in methodology, interviews were conducted through channels of the participants' choice. All data were transcribed and encrypted and in case of the in-depth interviews with participants anonymised. The coding scheme consisted of thirteen codes, with each code pointing to relevant aspects for the research.

Regarding the participants themselves, there is a reasonable range in profiles and backgrounds. Ages vary between 20 to 65 years and the duration of the interviews varied between 41:30 and 76:22 minutes. Essential for the selection was the link of these people to various pro-independence groups. I interviewed four members of various politically dissident organisations, all of them with a link to the CDR (Committees of Defence of the Republic). Additionally, interviews were conducted with a European Commissioner specialised in Spanish history and historical memory and a cap de Mossos

d’Esquadra, a chief of the regional Catalan police force.

Despite the fact that finding participants was not a stumbling block initially, the shift in methodology caused a series of problems. A first implication emerged when reaching older participants, who did not always have the possibility to communicate through online platforms. Secondly, two respondents had agreed to meet face-to-face, but dropped out once the methodology changed. This can be explained by a certain distrust towards online methods, as they were prosecuted or under police investigation at the time.

The concise netnography was limited to two events, namely two livestream interviews followed by debates and Q&A’s organised by ANC England, the English branch of the Assemblea Nacional Catalana.

10 The protagonist of the first attended livestream was Adrià Carrasco, CDR member and exiled for two years in Brussels. The action that led Adrià to be prosecuted was the CDR action of cutting roads and barriers at toll gates in order to let the cars pass freely. This action was considered as terrorism by the Spanish authorities. The documentary “Dormir amb les sabates posades" (“sleeping with shoes on”) was analysed as an additional source material. This documentary was directed by Adrià Carrasco, Tamara Carrasco and their environment and thus gives an emic perspective on the events and their experiences with police and the justice system. The second attended livestream ‘Political repression in the Spanish regime’ was organised with Aamer Anwar, former rector of the University of Glasgow and lawyer of the exiled Catalan minister of Education Clara Ponsatí. Each of these online events and the documentary had a duration of about 50 minutes.

As mentioned above, initial observations were made in early 2020 and documented in field notes. The first observation was a manifestation in Barcelona and the second one concerns an assembly of a CDR group.

4. Catalonia and Spain: a history of disagreement

In order to understand the sociocultural context in which the Spanish-Catalan conflict has exploded, it is required to dig deeper into history. Although the cultural repression of various national minorities in Spain is not a recent phenomenon and these types of conflicts can be traced back to centuries ago, this chapter will focus on recent history. General Spanish history is presented, namely how the country got involved in a civil war followed by four decades of fascist dictatorship. Given that this inquiry focuses on the criminalisation of political dissidence in Catalonia, targeted repressive actions against the Catalan population will be addressed. Eventually, the country underwent a transition era to democracy in the late 1970s. A third important identified era entails the period from 2010 to the present day, probably the most active and visible phase of the Catalan uprising.

This first chapter provides an answer to two research questions, namely (1) what is the socio-historical context which led to the current outburst?, and (2) How does the state react towards groups who endanger the established hegemony?

4.1 From civil war to dictatorship

Spain experienced a very turbulent period between the 1920s and 1930s. In 1923, Primo de Rivera, a Spanish Falangist soldier, lead a coup which resulted in a military dictatorship until 1931 (Thomas, 2018). The Falangist ideology could best be understood as the Spanish interpretation of fascism, which perfectly fitted in the European political climate back then. European post-Darwinism was one of the ideologies on which fascism was built, not only in Spain, but in the rest of Europe during the first few

11 decades of the twentieth century. This ideology was characterised by a belief in radical eugenics, seeking to distinguish so-called superior races from inferior ones (Moreno Gómez, 2019).

After 1931, Spain entered the period known as the Second Spanish Republic. However, this newly installed democracy was quickly destabilised by another military coup in 1936, this time conducted by Francisco Franco. The coup of 1936 embodied the radical Falangist ideology, justifying war and sustaining the fascist ideas of population “cleansing ” (Moreno Gómez, 2019). Franco addressed these operations towards the “biologically inferior”: the poor, the republican and the national minorities. The coup resulted in the Spanish Civil War which lasted until 1939. Two major parties can be identified during the civil war. On one hand the Falangists led by Franco, characterised by a deep-rooted Catholicism, conservatism and nationalism, supported by Nazi Germany and the Italy of Mussolini. On the other side of the front were the republicans, socialists, anarchists, communists and especially the women associated to these parties, which had gained suffrage during the Second Republic (Baquero, 2019). These women suffered a so-called double repression, not only were they tortured, executed or incarcerated but an extremely patriarchal system was imposed on them under the popular slogan “the

boy will look at the world, the girl will look at the home” (Borraz, 2015). This side of the front, labelled

as “Los Rojos” (the red ones), was supported by the Soviet Union, Mexico and the International Brigades consisting of volunteers from elsewhere in Europe. Franco won the war resulting in a fascist dictatorship up until his death in 1975.

Once the dictatorship was established, a primordial aspect of the Francoist politics was securing the unity of Spain, under the idea of a “Spanification of the Iberian Peninsula”. From 1939, a series of orders was created against Catalonia and its culture and language, a so-called attempt to a cultural genocide (Batista i Roca, 2017). A part of the anti-Catalan politics was the eradication of the Generalitat

de Catalunya, the Catalan regional government and administration. Therefore, the democratically

elected Catalan president Lluís Companys was executed. Like thousands of others, Companys sought exile, which he found in France. In 1940, Companys was arrested by the Gestapo and extradited to the Francoist authorities, subsequently he was sentenced to death by a council of war generals of Franco’s army (Batista i Roca, 2017). He was executed in Montjuïc, Barcelona in 1940.

Briefly after the military coup, the política de prensa franquista, the political strategy of the regime, was installed and control was taken over all means of communication, introducing military censorship for all printed publications (Sinova, 2006). A consequence of Francoist politics was the repression of national minorities, such as Galicians, Basques and Catalans and the prohibition of these languages by means of burning books, outlawing them from being taught in schools, censoring music etc. Franco’s alleged linguistic vigilance, consisting of policemen, controlled public areas and arrested those who

12 were caught speaking minority languages (Tree, 2019). An important non-governmental organisation which, through civil disobedience, managed to keep alive both Catalan language and culture is Òmnium

Cultural. Historically, Òmnium Cultural was seen as a cultural institution through which Catalanism was

promoted and thus separatism and leftism. Dictatorial authorities reported Òmnium Cultural to be a breeding ground for Catalan intellectuals and thus the possible penetration of Catalan and republican ideology in society (Zanon i Pérez, 2015).

4.2 Amnesty and oblivion

After Franco’s death in 1975, Spain underwent a transition era, shifting from a totalitarian regime to a reborn democracy. However, certain aspects which characterised this transition do evoke critical questions on the extent to which this process aiming to turn Spain into a democracy was intertwined with the Francoist apparatus itself. This intertwinement starts with the mere fact that in a matter of days after Franco’s death, King Juan Carlos I de Borbón was enthroned, ensuring Spain could not return to the republic it once was. The appointment of Juan Carlos I was already settled before the dictator’s death, on July 22 1969, when Franco formally assigned him as his successor, consolidating the essence of Francoism being Catholicism, tradition, the failure of parliamentarism and republicanism (Rueda Laffond, 2013).

Democratic forces were particularly weak in the country after four decades of fascism and the newly voted Constitution of 1978 was conducted by post-Francoism itself (Tamarit Sumalla, 2014). This claim by Tamarit Sumalla becomes clear upon closer analysis of the transition era. Between 1975 and 1976 several reforms were developed in order to establish a future constitutional monarchy. The Francoist Courts and the ministers under Franco designed and approved the Law for Political Reform in 1976, a law aiming to install a transition to a democratic system (Tamarit Sumalla, 2014). This bill was presented to the public through a binding referendum. However, the opposition was confronted with a deadlock, resulting in abstention of a significant part of the population. An affirmative vote by the opposition meant accepting a project from which they were excluded during its preparation and thus accepting the legal mechanisms of Francoism and a system favouring and protecting Francoist forces (Pérez Ares, 2008). A negative vote was no appealing solution either since this would heavily disturb the newly initiated path towards a democracy (Pérez Ares, 2008). Eventually, the Law of Political Reform was approved.

Even though the crimes of Francoism after the military coup of July 17 1936 were already considered as acts prohibited by the ius in bello (Moreno Gómez, 2019), the transition was characterised by certain peculiarities such as the absence of any kind criminal proceedings and debugging practices against war criminals (Tamarit Sumalla, 2014). This made amnesty and oblivion two core elements of the process. The pre-constitutional Amnesty Law of 1977 was approved during the transition and remained in force

13 ever since (Baquero, 2019), resulting in Spain blocking any possibility of prosecuting war crimes and thus creating an impunity for Francoism, protecting the Francoist elite up until today. The United Nations consistently urges Spain to withdraw the 1977 Amnesty Law in order to bring justice to the victims of the regime (UN News, 2014), a topic that has not been addressed to this day.

A first step in condemning certain aspects of the Franco regime was the rectification of La Ley de la

Memoria Histórica (the Law of Historical Memory) in 2007. This law approved subsidies for all sorts of

activities concerning historical memory e.g. exhumations, documentaries and conferences. However, the law is limited and does not abolish amnesty. Additionally, it orders the withdrawal of Francoist symbolism, e.g. street names, which are still common in public spaces (Escudero Alday, 2018). The Law of Historical Memory was voted in the Parliament under the socialist government of Zapatero and was passed with the rejection of the main opposition, namely the conservative Partido Popular (PP), which did not accept any kind of questioning of the transition nor the explicit condemnation of the dictatorship (Tamarit Sumalla, 2014). Mariano Rajoy, member of the Partido Popular, succeeded Zapatero as the Prime Minister of Spain after PP won the elections in 2011. In 2012 the Office of Victims of the Civil War and exhumations was annulled by Rajoy and a year later, no state funds were granted to any of the projects supported by the 2007 law (Baquero, 2019). By doing this Rajoy ignored the UN recommendations on human rights of victims.

4.3 l’Estatut: catalyst for the revival of a new wave of separatism

Although Catalan separatism is not a new concept, the exponential expansion of this renewed political wave started after 2010. During the transition era until the early nineties, Catalan separatism was almost exclusively promoted by leftist and extreme leftist entities.

L’Estatut of 2006 and especially the criminalisation of l’Estatut in 2010, is considered to be the main

catalyst for the revival of a new wave of separatism in Catalonia and the associated Spanish-Catalan conflict, which had never ceased to exist in the first place but was merely simmered down due to the re-installed democracy. Every autonomous region in Spain has a Statute of Autonomy, recognised by the Spanish Constitution of 1978, which regulates certain economic and juridical matters in the relationship between the regional and the central governments. The Catalan Parliament approved and put in force a new Statute of Autonomy in 2006, replacing the previous one from 1979. Notwithstanding, in 2010 the Spanish Constitutional Court declared the 2006 Statute unconstitutional, leaving 14 articles without legal effect, including the recognition of Catalonia as a nation (Perales-García, 2016), since this contradicted the unbreakable unity of Spain which only recognised the sovereignty of Spanish people guaranteed by the Constitution of 1978. The consequence thereof was a series of massive civil mobilisations throughout Catalonia. These manifestations emerged in a bottom-up way, among which the biggest ones were organised by civil entities – thus not bound to

14 any political party – such as Assemblea Nacional Catalana (ANC) and Òmnium Cultural. It is to be noted that both presidents of these civil organisations, Jordi Sànchez and Jordi Cuixart are currently imprisoned (Van Gastel, 2019).

4.4 Referendum of 1-O 2017

The call for Catalan secession became an explicit political matter over the past decade, when former president of the Generalitat Artur Mas (Convergència I Unió) negotiated the possibility of a referendum with the – at that time conservative government of Mariano Rajoy (PP) – in an analogue format to the ongoing referendum for Scottish independence (Castelló, León-Solis, & O'Donnel, 2016). These attempts however were in vain. The Spanish government immediately blocked any possibility for a referendum. This refusal of dialogue on the matter was motivated by the non-compatibleness of Catalan independence with the Constitution of ’78, in which the unbreakable unity of Spain is ensured.

The blockage of the 2014 referendum lead to a bottom-up alternative instead, in which civil groups

Òmnium Cultural and Assemblea Nacional Catalana formally organised a non-binding referendum

simulation in 2014 (Barberà, 2020). Despite the outcome of the this popular consultation on the right to self-determination being in favour for independence, no further attempts to dialogue were considered by the Spanish government. Subsequently, former regional president Artur Mas was banned from executing public services and was punished with a criminal fine (Barberà, 2020).

This symbolical, popular consultation of 2014 is considered the preamble of the 2017 referendum on independence (Castelló, León-Solis, & O'Donnel, 2016), known to be the referendum of October 1st or

1-O. The period between 2014 to 2017 was characterised by rising political tensions between the regional and central government and mass mobilisations of Catalan civilians. Polarisation became more tangible. On one hand, the pro-independence camp accused the Spanish state of being undemocratic, invoking the right to self-determination. On the other hand, the Spanish state accused Catalonia of acting in unconstitutional manners. One of the many ways this discrepancy was visible was through media coverage and reporting on the 2014 Scottish referendum. Where pro-Catalan newspapers applauded the British state in its exercise of democracy, Spanish conservative newspapers, in this case El Mundo, ridiculed the British political system describing the Scottish referendum as the “greatest discredit to the democratic system in the EU” and “a lesson in

anti-democracy” (Castelló, León-Solis, & O'Donnel, 2016). Using this argument, by analogy, the Catalan

referendum was portrayed as anti-democratic by Spanish media.

After 2014, more votes were cast for a new and binding referendum. On September 6th 2017, the

Catalan Parliament passed a law enabling a new referendum. In this process, the Catalan Parliament explicitly embedded the upcoming referendum in several international treaties and in the Charter of

15 the United Nations invoking the right of peoples to self-determination (Turp, Caspersen, Qvortrup, & Welp, 2017). This law however was illegal and unilateral according to the Spanish state, which later suspended this law in the Constitutional Court (Castellà Andreu, 2019) under the recurring argument that the 1978 Constitution – drawn up by the Cortes Franquistas – enshrines the indissoluble unity of the Spanish Nation (Cetrà, Casanas-Adam, & Tàrrega, 2018). However, institutional disobedience took place and the Catalan Parliament carried on the referendum, in which the question presented to the voting public on the voting ballots in 2017 read as follows: “Do you want Catalonia to be an independent State in the form of a republic?” (Turp, Caspersen, Qvortrup, & Welp, 2017). With a turnout of 43%, the pro-independence side won with 92% of votes (Muro, 2018). The Spanish State responded forcefully to the continuation of the referendum after it had been declared illegal. This response did not only entail the deployment of 12.500 police forces from outside Catalonia (Garrote, 2018), but also criminal prosecutions of politicians, civilians and non-governmental organisations, banning and closing down websites and media promoting the YES-vote, raising international concerns on the right to exercise freedom of expression (ILOM, 2017). On October 27, the Catalan Parliament declared the independence of the Catalan Republic (Garrote, 2018), which was immediately revoked in a last attempt to dialogue with Madrid.

Prime Minister Rajoy (PP) refused any dialogue, declared that no referendum took place on October first (Garrote, 2018) and exerted article 155 of the Spanish Constitution through which Spanish authorities are entitled to impose direct rule over Catalonia (Ciacchi, 2017). On October 11, 2017 for the first time in Spanish history, article 155 was activated (Rovira, 2018). This article enables the Spanish State to enforce compliance upon an autonomous community when legislation is breached (Bossacoma & López Bofill, 2016), when it fails budgetary or financial obligations or when the autonomous community constitutes a risk against the general interests of Spain (Morales, 2018). Article 155 doesn’t abolish Catalan institutions, however it does permit a suspension of self-government (Bossacoma & López Bofill, 2016), temporarily centralising all power in Madrid.

After two years of custody, on October 14, 2019 the verdict was pronounced. Penalties for crimes of rebellion and sedition varied between nine and thirteen years. Six parliament members: Carme Forcadell, Josep Rull, Jordi Turull, Raül Romeva, Dolors Bassa and Joaquim Forn were convicted to prison varying from ten years and six months to twelve years. Catalan vice-president Oriol Junqueras got the highest sentence of thirteen years. The fact that the European Court ruled that Junqueras, should be freed since he was elected as Member of the European Parliament and thus had immunity, did not change the opinion of the Spanish Supreme Court, which refuses to recognise Junqueras as a European Parliamentarian (BELGA, 2020). Jordi Sánchez and Jordi Cuixart, leaders of Assemblea

16 Gastel, 2019). Several Catalan politicians are currently exiled in Belgium, Switzerland and Scotland, namely former president Carles Puigdemont, Antoni Comín, Lluís Puig, Meritxell Serret, Clara Ponsatí and Anna Gabriel. Not only politicians and leaders of civil organisations were prosecuted by the Spanish state in the context of the Spanish-Catalan conflict, but in addition several artists and activists are being prosecuted or convicted for crimes going from sedition to terrorism. Examples thereof are rappers Josep Valtònyc and Pablo Hasel and CDR members Tamara and Adrià Carrasco.

4.5 Excesses of the Spanish impediment to uphold the 1-O referendum

Unlike 2014, when the popular consultation was tolerated by the Spanish authorities, a whole different scenario took place on October 1st 2017. In order to impede the referendum, the Spanish Government

deployed forces of the Civil Guard and National Police from elsewhere in the national territory. Assigned commander in chief of the National Police, Civil Guards and the Mossos d’Esquadra during this operation to withhold people from voting, close schools and confiscate voting material was Diego Pérez de los Cobos. Running a background check on Pérez de los Cobos it quickly comes to surface that some question marks can be placed around his figure. During the transition era in the late seventies Pérez de los Cobos actively campaigned for the NO-vote on the Spanish Constitution of 1978 (Talegón , 2019). In 1981 he volunteered as a Civil Guard supporting the fascist military coup d’état of Tejero (Tree, 2019), when Lieutenant-Colonel of the Civil Guards Antonio Tejero Molina, joint with armed Civil Guards held the Spanish Congress of Deputies hostage during the investiture vote of the Spanish Prime Minister (Muñoz Bolaños, 2016). Lastly, in 1992 Pérez de los Cobos was charged for torture and acquitted in the case of Kepa Urra, a presumed ETA member (Talegón, 2019). Noting that this particular man was in charge of the entire police action on the day of the Catalan referendum on auto-determination, the critical question can be asked again to what extent the Spanish transition era was intertwined with the dictatorial apparatus and to what extent these excesses are still tangible today.

International NGO’s such as Amnesty International denounced Spain for police brutality committed on 1-O 2017. Besides the use of excessive force against passively resisting protesters and voters by National Police and Civil Guards, Amnesty International accused the police of using dangerous riot equipment and substandard rubber bullets (Amnesty International, 2017). Despite international outrage, politicians and the media in Spain sought to justify and normalise the police violence. Reyes (2020) analysed this normalisation discourse through critical discourse studies of the most read Spanish newspaper El País, in which he found that the normalisation of violence towards Catalan voters was constructed in several steps. El País created a discourse in which pro-referendum ideologies are criminalised, denying dialogue and subsequently emphasising the enshrined unity, normalising police violence in name of the Constitution and democracy since it should be the only acceptable option to proceed (Reyes, 2020). Simultaneously, the violent response from Spanish authorities led to a shift in

17 public discourse on the pro-referendum side, where the call for independence became a more fundamental call defending the right to vote (ILOM, 2017).

4.6 Legality, legitimacy and critical views

One raised issue was the lack of guarantees of this referendum in complying with international standards. This non-compliance is due to the lack of transparency and the anonymity in which preparations were done. The lack of transparency was motivated by the struggles and fear for repercussions by the central government, as observed by ILOM’s team of independent international election experts (ILOM, 2017). An additional concern was the implementation of the universal census, entailing that people could vote at the polling station of their choice, and thus not necessarily where they were registered (Cetrà, Casanas-Adam, & Tàrrega, 2018). A potential peril of this policy choice was the risk of people voting multiple times. However, by implementing the universal census, Catalan authorities anticipated on police interventions aiming to close polling stations, guaranteeing that people could still vote elsewhere. Nonetheless, ILOM (2017) did observe that despite circumstances the staff at polling stations tried to follow electoral procedures as much as possible.

Due to the low turnout of only 43% population and the non-existing democratic conditions in combination with hard police repression from Madrid, it is hard to recognise the referendum results as valid (Garrote, 2018). However, over two million people voted, meaning that a significant part of Catalan society supports independence and this exact popular support and citizen’s consent is a source of legitimacy (Muro, 2018). Whether the referendum was legal, legitimate and democratic is a hard confrontation between different political views on the status of Catalonia. Catalonia considers itself as a nation within Spain, as stated in the 2006 Estatut (Perales-García, 2016), Spain only recognises one unified Spanish nation, insinuating only the Spanish nation as a whole has the right to self-determination, excluding national minorities. Pro-referendum supporters recognise this fundamental right over strict and literal interpretations of what they consider a flawed Spanish Constitution (Cetrà, Casanas-Adam, & Tàrrega, 2018).

Not one politician of the leading parties was formally held accountable, nor lamented or addressed the authorities’ actions for the police brutality that occurred the day of the referendum, which left several hundreds of people injured (Reyes, 2020). Former Vice Prime Minister Soraya Sáenz de Santamaría (PP) applauded the professionalism of police forces in their compliance with the judicial mandate to impede the referendum (El Plural, 2019), denying that the used force against voters was disproportionate. Current Spanish king Felipe VI gave an exceptional television speech on the events in Catalonia two days after the referendum. During this television transmission, Felipe VI, formally accused the Catalan government of an inadmissible disloyalty in which the monarch labelled the referendum on self-determination illegal and anti-democratic (Pichel, 2017). However, from a critical

18 point of view, it may be questioned to what extent the king should rule on this, knowing that he was never elected in a democratic process in the first place – unlike the imprisoned and exiled politicians – and knowing that his father was enthroned by a dictator.

In strict legal terms the acts of the pro-independence camp could be seen as illegal, yet as acts of civil disobedience, in this case the opposition of the secessionist camp against a rigid Spanish government. The response of Spanish authorities is an example of top-down unlawful abuse of public power, in which legal restrictions were breached as well (Ciacchi, 2017).

5. Criminalising political dissidence

Keeping the historical context in mind, this part of the article provides insight on the criminalisation of political dissidence on a micro level, by analysing the individual narratives and experiences of people I closely worked with over the past few months.

5.1 “If you see us running, run with us!”

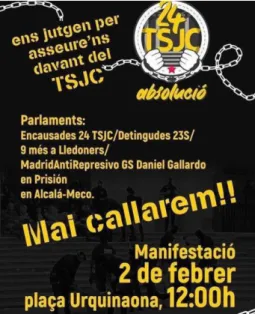

I travelled to Catalonia in February 2020. The goal was to observe actions and meetings organised by the pro-independence camp and to meet people who would want to share their stories and with whom I could go to activities for a longer period, with the initial PAR in mind. A few days before travelling to Catalonia a convocation for a manifestation was shared on several social media platforms (figure 1), following the criminal charges of two CDR women who held a sitting protest at the Supreme Court of Catalonia. The public prosecutor demanded two years of imprisonment. The manifestation itself was organised by different CDR groups.

The CDR, Comités de Defensa de la República, namely Defence Committees of the Republic, are a series of small scaled units on the level of villages, cities, neighbourhoods and communities all over Catalonia that are managed in an assembly manner (Barcelona, 2018), without a central management nor hierarchy. About 400 CDRs exist both inside and outside Catalonia (Esteve i Garcia, 2018). The CDR are a recent phenomenon whose origin can be situated in the anticipation of the referendum of the first of October 2017, when several CDRs were created in order to protect the masses from police violence, hiding ballot boxes and ensuring schools remained open to vote. Thus, the main objective of CDRs at the moment of their creation was securing the continuation of the referendum on Catalan independence, all parting from pacific mobilisation and a non-violence strategy, publicly calling for civil

19 disobedience. Common strategies within this non-violence ideology – recurring in their actions – are a position open for negotiation, publicly calling out injustices, direct action in the form of various protests, non-collaboration and assuming possible criminal consequences (Esteve i Garcia, 2018). However, the sudden visibility of CDRs caused a series of accusations from Spanish media linking CDRs with terrorism.

Initial observations of CDR groups held during the first week of February 2020 revealed that these groups contain a fairly heterogenous profile regarding to age, gender and political background. CDR groups are not linked to any political party, resulting in individual differences among the members concerning political preferences. Therefore, it is not evident to create a general profile of CDR groups. Each assembly is an independent entity and should be analysed individually.

I arrived early on the protest at Urquinaona square in Barcelona. As different CDR groups and people started to arrive, I went into the crowd and talked to attendants, asking if I could take pictures of the symbolisms they used to protest. Figure 2 shows a protester carrying numerous

symbolisms. From top to bottom: a barretina, the traditional Catalan headgear, a Vendetta mask, a shield representing Captain Catalonia, a gilet jaune as well as a kilt in solidarity with the Scottish independence movement. He poses next to a rubber bullet, which have been prohibited by the Catalan Parliament since 2014, but can still be used by the Nacional Police in case of operations in Catalonia (Ramos-Salvat, 2019; Redacció, 2013). Amnesty International (2017) found these bullets used by Spanish police forces during actions in Catalonia to be dangerous and substandard. Each rubber bullet had a short phrase written on it such as ‘dignity’ and ‘resist’. Other symbols used at the manifestation insinuated that the CDR movement profiles itself as a progressive movement e.g. people wearing feminist badges and carrying pride flags. I kept on walking around in the crowd talking to people, mentioning the fact that I’m a student writing a thesis on the criminalisation of political dissidence. Soon, a woman introduced me to important figures within the CDR movement. They were glad a student from abroad showed interest

Figure 3: protester

Figure 2 The estelada (independence flag) together with the rainbow flag

20 in their actions and were open in sharing information and contact details. The CDR member responsible for security informed me that this event had not been announced to the police forces, resulting in the right of police forces to arrest us. This however did not seem to scare anyone. I marked his words: “If you see us running, run with us”. The event, walking from Urquinaona square to the Superior Court of Justice of Catalonia proceeded calmly. People sang, played music, hung stickers saying “Fora el Borbó, Republica Catalana – CDR” (Away Bourbons – Catalan Republic!) and yelled slogans such as “Els carrers seran sempre nostres” (the streets will always be ours) and slogans directed at the police forces “No us mereixeu la senyera que porteu” (you don’t deserve the senyera – catalan flag – that you are wearing). Police forces were present. What surprised me was that they immediately sent heavily armored anti-riot police forces with shields, helmets, batons and armored cars. All this for what seemed to be a calm group. Everything proceeded peacefully that day.

The second observation took place in the week following the manifestation, where I attended a CDR meeting after being invited by people who were present at the manifestation. The local of this urban CDR group was all covered in protest material, political slogans and feminist slogans. The attendees themselves were both women and men of all ages, discussing the next actions they would organise. I was well-received and explained the purpose of my thesis. Initially, I would have participated to and observed their activities over a long period of time, yet due to Covid-19 the PAR methodology this was no longer viable.

5.2 Involvement in politically dissident groups

The Comités de Defensa de la República (CDR) are one of many groups active in the pro-independence movement. By the time CDRs were created in the anticipation of the 2017 referendum, most participants were already politically active, describing their entry in CDR as an obvious and natural step in order to ensure they could vote. Some participants were active in other movements besides the CDR, in which a distinction should be made between the three people in their twenties and the participant in his sixties, who had a differentiated background. Younger participants mentioned to be simultaneously active in CUP, ARRAN and La Forja. CUP (Candidatura d’Unitat Popular) is a Catalan, secessionist political party positioned on the far-left of the political spectrum. ARRAN and La Forja

Jovent Revolucionari are two quite similar organisations in the sense that these are political entities

for the leftist, secessionist youth which besides advocating for independence and socialism are also active in the feminist and ecological struggle across Catalonia (ARRAN, 2013; La Forja, 2020).

One aspect the above mentioned political entities have in commons is their leftist position on the political spectrum. However, it is important to stress that CDRs are not homogenous groups and political orientation can vary depending on the person and location. The four CDR participants, coming

21 from three different CDR assemblies did mention that urban groups tend to be rather leftist compared to CDR groups in rural locations, which tend to be more central or liberal on the spectrum.

The older participant, or – as he calls himself – ‘the historic militant’, has a differentiated life course. He started his political activism in the mid-seventies, known to be the most repressive era of the dictatorship along with the post-war era. He grew up under the influence of the anti-Francoist resistance and started his activism during his adolescence with the Catalan Revolutionary Youth, namely the youths of PSAN-P, a clandestinely operating pro-independence party. Later on he co-created the EAC (Excèrcit d’Alliberament Català/Catalan Liberation Army) and was involved in the MDT (Moviment de Defensa de la Terra/Territory Defence Movement), which wasn’t a political party but an inter-syndicate organisation which agglutinated several pro-independence parties and was a committee of solidarity with Catalan reprisals. In the early eighties he co-created and joined Terra

Lluire, the Catalan armed insurgency, strongly influenced by the ideas, structures and mechanisms of

ETA, the Basque ethnonational terrorist group. The creation of Terra Lliure traces back to the transition era (Chriswell, 2014) and the outrage over the 1977 Amnesty Law, which was applied to the atrocities of the Francoist regime, but not to the anti-Francoist Catalan resistance. Therefore, Terra Lliure was created in an attempt for a total break with the regime (Sastre, Musté, Benítez, & Rocamora, 2013).

“Think that in ’73 they murdered Puig Antich, they killed others on the street. The police were killing. They didn’t shoot rubber bullets back then, they fired real bullets. In 1975, two ETA companions and three FRAP companions were killed. The last deaths of the Franco regime. In ’78, Gustau Muñoz died in my arms. I mean… they killed him, he fell dead in front of me at only 16 years old. Then Jordi Martínez was killed in the same circumstances. I saw companions being killed and tortured at manifestations... I mean, this creates another type of conscience, a more extreme one. And then you believe… you felt young and at that time I was 17, 18 years old and I thought I would eat the world and well, you get involved in the armed insurgency in a natural way. And I said well I go to manifestations and from the moment they attack us, we strike back. And more with the youth and the anger you felt inside and all that... because it is a natural step, without any complications. Think that in each manifestation we had like 3 deaths back then. It's not like now eh.” (R4)

This participant joined the armed insurgency in the late seventies and was trained by the ETA in Basque Country. He was arrested after an action involving explosives, for which he spent about five years in prison during the eighties. He left Terra Lliure and engaged in a non-violent independence struggle instead. Terra Lliure ceased to exist in 1995 (Sastre, Musté, Benítez, & Rocamora, 2013), no armed Catalan secessionist group emerged ever since.

22

5.2.1 Police violence

All CDR members have experienced police violence, whether it was on 1-O or in the aftermath of the verdict in late 2019. Participants mentioned crowds being teargassed, beaten up with batons, police cars running over people, arbitrary arrests, not being informed where friends were taken by police forces, threats by policemen and rubber bullets being fired. One participant and his partner were hospitalised after being beaten with batons. Another participant mentioned a friend being beaten multiple times on the head, leading to a loss of consciousness and a hospitalisation, where it took over a day to know whether this person would lose his eye. Concerning the charges of policemen, only a small part was investigated and all of them have been acquitted. Additionally, the policeman who participated confirmed and condemned the actions of the National Police and Civil Guard.

“Yes, totally disproportionate. We (Mossos d’Esquadra: Catalan regional police) would never have done that ourselves. Not because we’re nicer or good, when we need to act we act. (…) But in this case, a referendum in which you knew the profile of people who would vote, was the perfect excuse for the police forces who came to do certain aggressions, some brutality.” (R6)

5.2.2 Judicial charges

People expressing republican political dissent in Spain are often target of prosecutions for crimes going from rebellion, to slandering the Crown to terrorism. Recent changes in Spanish Criminal Law contribute to this. Within this context it is important to mention the voting of La ley orgánica 4/2015

de protección de la seguridad ciudadana (LSC - the Law on Civil security), known as the Ley Mordaza,

(the gag law) which was passed in 2015. The discussion surrounding the controversial LSC stems from the question whether this law does indeed guarantee civil security or whether it is an instrument to silence masses, in which the LSC is seen as an attack on the right of freedom of expression and the right to manifest (Durán, 2018) since this law enables authorities to limit free speech, manifestations and the access to information on matters of public interest (Legaling, 2020). An additional problem is the application of a vague and recently extended anti-terrorism law, criminalising the glorification of terrorism and the lack of respect for the victims of terrorist acts in articles 571 to 577 of the Criminal Code (BOE, 2015), leaving a wide range of interpretation. A last recurring law used to criminalise political dissidents, among others rappers Pablo Hasel and Josep Valtònyc, is slandering and insulting the Crown, which is considered a crime by article 169.2 of the Spanish Criminal Code (Columbia University, 2018). A question that can be raised here is whether this law is an infringement of both the right of free speech and the principle of equality, since it protects one specific family over others. The following narratives about prosecution should thus be seen in the light of this legal climate.

One participant faced criminal charges after a small demonstration protesting the application of article 155 at the Superior Court of Justice of Catalonia. The goal was to denounce the Spanish Justice system

23 by putting chains around protesters in front of the stairs of the building. It was a peaceful protest with no violence of any kind. Fourteen of them were arrested that day in February 2018. They spent the night at the police station and were charged for crimes of (1) attack on state institutions, (2) public disorder, (3) disobedience to authority, and (4) and resistance to authority. They were sent to court the next day where they were released on bail. In September 2018 they found out the Public Prosecutor demanded two and a half years in prison. They did not collaborate with the judiciary initially, leading to another arrest, where about 150 police officers surrounded the participant and two others at a press conference. The day of the sentence they were acquitted.

“Well, we all expected it. Because the moment you are arrested and charged for so many things just for being there… you say… I mean, everything is political right? You see, there is a clear political will here to scare and repress people. So bottom line, we really expected it.” (R5)

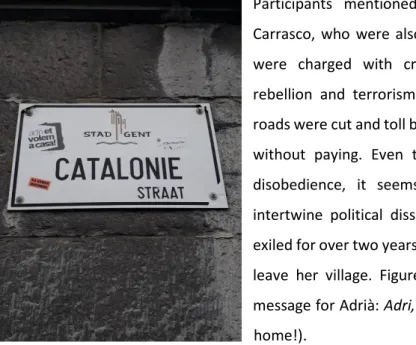

Participants mentioned the case of Tamara and Adrià Carrasco, who were also subjects of the netnography. They were charged with crimes of public disorder, sedition, rebellion and terrorism after a CDR mobilisation in which roads were cut and toll barriers were raised so cars could pass without paying. Even though this is a clear case of civil disobedience, it seems that the Spanish state tries to intertwine political dissent with terrorism. Adrià has been exiled for over two years in Brussels. Tamara is not allowed to leave her village. Figure 4 shows a sticker with a support message for Adrià: Adri, et volem a casa! (Adri, we want you home!).

A remark made by three participants was the case 23S. On the 23 of September 2019, nine CDR members were arrested and accused of terrorism and possession of explosives in the so-called ‘Judas Operation’. Seven out of the nine people spent over three months imprisoned in the Soto de Real prison in Madrid, under the FIES regiment, a closed high-security regime applied on terrorists and prisoners considered as extremely dangerous (Brandariz García, 2002). They were released after a few months due to a lack of solid evidence. Within the context of this case, the ‘historical militant’ mentioned having suffered an infamy in which the press blamed him of radicalising the nine CDR members, instructing them on armed insurgency matters like Terra Lliure. It did not took him long to prove the accusations were false, however, only a small note was published in that specific newspaper withdrawing their accusation. He claims the press directly targets and discredits him, seeking to

24 personally destroy him and find any reason to imprison him. The Judas Operation also investigated people for who participated in the Tsunami Democràtic (Lleonart Fernàndez, 2020), a series of actions where people occupied places, among others, the French border in the aftermath of the 2019 sentences. Concerning the occupation of the French border, those arrested on the French side got away with an administrative fine for public disorder. Those arrested on the Spanish side faced charges of terrorism.

Lastly, participants mentioned the cases of rappers Pablo Hasel and Josep Valtònyc. Both artist were convicted for crimes of slandering the crown and incitement to terrorism. Hasel was sentenced to two years and a day in prison (Pérez, 2018) and is the first artist to be incarcerated for criticising security forces and the monarchy for being corrupt since democracy was re-installed (El Tribuno, 2020). Valtònyc – whom I closely worked with in the context of previous research – was sentenced for the same crimes, yet he opted for exile and has been living in Brussels for over two years. His case was reviewed by the Court of First Instance in Ghent, which refused to extradite the artist and acquitted him (Souvenir, 2019).

5.2.3 Opinions on the Spanish state

One code used in the data analysis phase was 'opinions on the Spanish state'. Its purpose is to include what opinion people had about the workings of the central authorities when handling the Catalan case. Recurring terms are listed here.

¿Franco ha muerto? - Did Franco die?

All participants and by extent the people in the netnography stated that Franco, or at least Francoism is still very much alive in Spanish society and thus did not die. Participants tended to mention the 1977 Amnesty Law, stating that the lack of debugging practices back then resulted in the protection of Francoist elites and institutions nowadays.

Franco’s mythification can still be found in many domains, besides name plaques of squares and streets, Franco’s symbolism also occupies the form of sculptures, emblems and even football clubs such as the Villafranco Club de Fútbol (Baquero, 2015). Three participants addressed the existence of the Fundación Nacional Francisco Franco, the National Francisco Franco Foundation (FNFF) to substantiate their argument. They pointed out that the same concept, a state funded Hitler Foundation in Germany would be illegal. However, the FNFF in Spain is still a functioning and visibly powerful lobby group (Baquero, 2019) with a freely accessible media platform and website propagating Falangist ideas and glorifying the figure of Franco. Not only is the FNFF a legal lobby group, but it also received public funds from the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports between 2000 and 2004 under the

25 conservative government of Aznar (PP). The FNFF was awarded a total of 150.843, 82 euros in grants (Fundación Nacional Francisco Franco, 2018).

Imperialism

Aamer Anwar and one participant referred to Spain as a state that is still imperialistic.

“It just seems to me you only have to mention the word Catalonia and then all of a sudden any reason or common sense or rationale goes out of the window. It reverts automatically to the view of what general Franco would’ve thought of this time, as in use your baton and use your boots to crush these people. It’s like a colony (…) You know it’s a colony Catalonia. And of course they have tried everything possible to destroy that desire for independence, to destroy that desire for freedom. But it’s not gone away! And actually Spain, I’ve always believed that Spain, the best thing they could’ve done probably in the referendum was just to ignore it. Instead they used their old tactics. They sent the colonial occupying force, cause that’s what it looked like. You know, the great Armada sailing into the port of Barcelona to then teach the locals a lesson.” (Aamer Anwar)

Democracy?

Participants expressed their concerns with the lack of democracy and freedom of speech in Spain, often tracing the issue back to an incomplete transition. Some participants expressed the rather radical opinion that Spain is a dictatorial country. Other participants recognised an improvement compared to the past, but perceive Spain as a very imperfect democracy which falls short in certain areas. They referred to the '78 regime that is still in place today.

“I do not call it a democratic transition because of course, nothing was done. There was an amnesty, an amnesty was signed and those who were with Franco before, those who governed with Franco, overnight became democrats, but they did not change anything at the political level (…) Manuel Fraga was Minister of Information during Franco. And then he was one of those who wrote the Spanish Constitution in democracy, Manuel Fraga. Well, that man created the Popular Alliance, which became the Partido Popular.” (R3)

Double standards

Last recurring perceptions on the Spanish authorities concerned double standards and a lack of impartiality in the justice system. Participants mentioned a defective separation of powers and judges being politically motivated, referring to the gag law.

26

“So what strikes me the most about the gag law is the double measuring bar, right? That is, if, for example, I criticize some fascists, with the gag law, or very important people in Spain that I consider Francoists, if I insult them, I have problems in Spain (…) Is it the double measuring bar, right? Where is terrorism, where does it begin and where does it end? The problem with the gag law is that you don't really know how it works (…) When you think differently, that's when you're going to have problems in Spain. They do not like it.” (R3)

“Juan Carlos has 1.7 million briefcase and allegations of you know in propriety and… yet they chase Catalan politicians accusing them of embezzlement. They can’t actually pin anything down, we’ve never seen… for instance, they wanted to prosecute Clara for embezzlement. You know, and the same for the rest of the Catalan politicians. They’ve never been able to find any in propriety, they’ve never been able to find corruption. Yet for some reason if you’re a Spanish politician then you won’t go to jail. If you’re a former king, then where is the criminal investigations, where is the prosecutions? It seems to be double standards and hypocrisy.” (Aamer Anwar)

5.3 Auto-justifications: why keeping up the struggle?

This part addresses the fourth research question: What are the motives of those who engage in civil disobedient movements willingly, knowing the risk of possible prosecution?

“Because I thought that… besides thinking that my politicians, the politicians representing my county were imprisoned, I believed that they were imprisoning my ideas. They were imprisoning my way of being, my culture.” (R2)

What seemed to be the most important motivation for keeping up the struggle was the desire for independence and liberation itself. An opinion expressed by both a participant and Aamer Anwar, is that the Catalan question is no longer a mere question of independence, but rather a question on fundamental rights, free speech, democracy and the right to self-determination. According to them, the simple fact of something being constitutionally enshrined does not make it correct. Others mentioned an accumulated political discontent – generalised over various domains – that did not seem to fade anytime soon.

“It is a political conflict. What happens is that Spain has never made a proposal to convince people or to convince me or anyone who is pro-independence to stay in Spain. I don’t think any political project in Spain offers it to me. All I’ve received are beatings from police, arrests, arrests of people surrounding me, violations of our culture, language etcetera and violations of social rights and freedoms. They don’t offer us any project. How long will this last? (…) I hope that this will be resolved by voting in the end.” (R5)