Experienced parenting in a clinical

group of adolescent boys with conduct

disorder

Differences between age of onset and callous-unemotional traits

Word count: 11,777Karen Reyniers

Student number: 01202824Supervisor(s): Dr. Olivier F. Colins

A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Educational Sciences – Clinical Orthopedagogy and Disability Studies

Preamble concerning COVID-19

The COVID-19 outbreak had no significant impact on this thesis.

Table of Contents

Preamble concerning COVID-19 ... 2

Table of Contents ... 3

Abstract ... 4

Ervaren ouderschap in een klinische groep adolescente jongens met normoverschrijdende gedragsstoornis – Verschillen in beginleeftijd en beperkte prosociale emoties ... 5

Introduction ... 6

Methodology ... 9

Participants and procedure ... 9

Instruments ... 9

Data-analysis ... 10

Results ... 11

Descriptive statistics ... 11

Correlation between age of onset and CU traits ... 12

ANOVA harsh/warm parenting ... 12

ANOVA warm parenting mother / father ... 14

ANOVA harsh parenting mother / father ... 15

Discussion ... 16 Limitations ... 19 Strengths ... 19 Conclusion ... 20 Acknowledgements ... 21 References ... 22 List of acronyms ... 26 List of Tables ... 26 List of Figures ... 26 Attachments ... 27

Attachment 1: DSM 5 criteria Conduct Disorder ... 27

Attachment 2: DSM-IV criteria Conduct Disorder ... 29

Attachment 3: List of reference questionnaires for parenting ... 30

Abstract

Objective: Research on the link between parenting, conduct disorder (CD), and callous-unemotional traits (CU) has already been widely conducted with inconsistent results. Moreover, most studies focus on one way of subtyping CD when looking at that relation. The present study wanted to incorporate both ways of subtyping CD currently used in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). The first aim was to determine how many boys staying in a youth correctional facility have childhood onset CD and adolescent onset CD. Secondly, a possible correlation between age of onset of CD and the presence of CU traits was investigated. Using the two ways of subtyping CD, the participants were split into four groups (childhood onset CD without CU, childhood onset CD with CU, adolescent onset CD without CU, and adolescent onset CD with CU). Lastly, and most importantly, differences between experienced parenting were investigated between the four groups.

Method: The participants were 133 boys staying in a Flemish youth detention centre. All data was gathered using self-report. The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL) was used to determine if the boys had CD, while the Clinical Assessment of Prosocial Emotions (CAPE) gave information on the presence or absence of CU traits. The questionnaire developed for the Odysseus project was used to visualise the experienced parenting aspect. Using statistical analysis, answers to the research questions were formulated.

Results: More boys showed adolescent onset CD than childhood onset CD. The majority of the participants had CU traits. No correlation was found between the age of onset and the presence of CU traits. Regarding experienced parenting, significant results were found for warm parenting of the mother and harsh parenting of the father.

Conclusion: Using both ways of subtyping CD adds value in investigating variation in parenting with results showing differences in experienced parenting between the four groups. Furthermore, this study supported the evidence suggesting different influences between the mother and father figure. Future research could benefit in making the distinction between the two.

Ervaren ouderschap in een klinische groep adolescente jongens met

normoverschrijdende gedragsstoornis – Verschillen in beginleeftijd en

beperkte prosociale emoties

De coronacrisis heeft de inhoud of uitwerking van deze masterproef niet beïnvloed.

Verschillende studies hebben de correlatie tussen ouderschap, normoverschrijdende gedragsstoornissen (CD) en de aanwezigheid van beperkte prosociale emoties (CU traits) reeds onderzocht. Hoewel de resultaten van die studies niet altijd consistent zijn, bouwt deze thesis verder op de hypothese dat er verschillen in ouderschap merkbaar zijn tussen verschillende groepen van jongens met CD. De meeste studies in dit onderzoeksgebied beperkten zich tot een vorm van subtypering van CD, met een grote focus op de aan- of afwezigheid van CU traits. Deze studie combineert de twee vormen van subtypering die momenteel in de Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, Vijfde Editie (DSM 5) vermeld worden, namelijk de beginleeftijd van CD en de aan- of afwezigheid van CU traits. Voor deze studie zijn 133 jongens geïnterviewd en hebben ze vragenlijsten ingevuld. Alle jongens verbleven in een van de Vlaamse gemeenschapsinstellingen.

Het doel van deze studie was enerzijds om te onderzoeken hoeveel jongens een normoverschrijdende gedragsstoornis hadden, beginnend in de kindertijd (voor de leeftijd van 10 jaar al minstens 1 symptoom vertoonden) en hoeveel een begin in de adolescentie kenden (geen symptomen voor de leeftijd van 10 jaar). Hiervoor werd gebruik gemaakt van de Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL). Verder werd ook onderzocht hoeveel jongeren beperkte prosociale emoties vertoonden. De Clinical Assessment of Prosocial Emotions (CAPE) werd gebruikt om die aanwezigheid te bepalen. Daarna werd onderzocht of er een correlatie was tussen de beginleeftijd en de aan- of afwezigheid van CU traits. Als laatste werd de jongeren gevraagd een door een doctoraatsstudente ontwikkelde vragenlijst in te vullen rond ouderschap. Hierbij werd gepeild naar op welke manier zij hun ouders ervaren hebben, met de opsplitsing in warm en hard ouderschap. Om verschillen in ouderschap te onderzoeken werden de jongens opgedeeld in 4 groepen, jongens met een begin van CD in de kindertijd zonder CU traits, diegenen met een begin van CD in de kindertijd met CU traits, jongens met een begin in de adolescentie zonder CU traits en jongens met een begin in de adolescentie met CU traits.

Door middel van statistische analyse werd duidelijk dat er meer jongens waren met een beginleeftijd in de adolescentie. Over de gehele groep waren er ook meer jongens die CU traits hadden. Er werd geen significante correlatie gevonden tussen beginleeftijd en aanwezigheid van CU traits. Wanneer verschillen in ouderschap onderzocht werden, bleek dat er significante verschillen waren voor warm ouderschap van de moeder en hard ouderschap van de vader.

Het is een meerwaarde om de groep jongeren met CD op te splitsen door beide vormen van subtypering in 4 groepen. Resultaten toonden dat de gevonden verschillen niet over alle groepen dezelfde waren. Deze studie vond verschillen in significantie van ouderschap tussen de vader- en de moederfiguur. Verder onderzoek rond ouderschap binnen de groep jongeren met CD kan er baat bij hebben om die opsplitsing tussen vader en moeder steeds mee te nemen in analyses.

Introduction

Children with conduct disorder (CD) have great difficulty following rules, showing empathy, and respecting the rights of others. Their behaviour is often not socially acceptable and they are frequently viewed as delinquent children (American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 2018). In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) CD is classified as one of the disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders. A full list of CD criteria can be found in Attachment 1: DSM-5 Criteria Conduct Disorder.

Conduct disorder can be divided into subtypes in different ways. In literature, the following subtypes have received a considerable amount of attention: subtyping based on age of onset; subtyping based on comorbidity with other psychopathologies; based on callous-unemotional traits; and lastly based on reactive or proactive aggression (Fanti, 2018). This study will focus on the two ways of subtyping currently included in the DSM-5, age of onset and the presence/absence of CU traits (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). One way of subtyping is to look at the age of onset. Childhood-onset CD, characterized by childhood behavioural problems before the age of 10, has the highest risk of persistent delinquent behaviour in adulthood (Pardini & Frick, 2013). A family history of antisocial personality disorder or alcoholism can exacerbate the risk of developing childhood-onset CD (Silberg, Moore, & Rutter, 2015). This could mean that youth are experiencing difficulties in acquiring the right social skills and internalizing the rules for socially acceptable behaviour. The group of youth with childhood-onset CD however is smaller than the group with adolescent-onset CD (Moore, et al., 2017).

A larger group of youth with CD only begins showing symptoms during adolescence (adolescent-limited), after the age of 10. The cause of the latter, in contrast with childhood-onset CD is better found in poor monitoring of rebellious teenagers. Evidence suggests that many youths with adolescent-limited CD still partake in criminal behaviour during adulthood. This is in contradiction to the hypothesis that, during the transition in adulthood they would adopt prosocial behaviour (Pardini & Frick, 2013). Adolescent-limited CD could be confusing and it is better to refer to this group as having adolescent-onset CD (Sentse, et al., 2017).

In the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Regier, et al., 2013), the CD diagnosis has been included with a ‘limited prosocial emotions’ specifier (LPE) to designate those who show significant levels of callous and unemotional (CU) traits. These limited prosocial emotions include a lack of remorse, lack of concern about performances in important activities, lack of empathy, and shallow affect (Pardini & Frick, 2013). It was thought this specifier would define a severe antisocial group of CD, but research so far has not been conclusive. Some evidence for the specifier’s usefulness has been found. In the study of Jambroes et al. (2016), however, only differences were found in the group of early onset CD with LPE and without LPE for proactive and reactive aggression. No differences were found for rule-breaking behaviour or internalizing problems (Jambroes, et al., 2016). Research by Colins (2016) also indicated that in a clinical context the usefulness of the LPE specifier is limited, considering the CD diagnosis by itself is more clinically useful without linking it to the presence or absence of the LPE specifier. A recent study showed that practical usefulness of group differences is sparse (Colins, et al., 2020).

Frick (2009) however showed that youth with conduct problems and CU traits differ significantly from other youth with conduct problems and without CU traits on different levels. Youth with high levels of CU show a lack of concern regarding performance, absence of concern for the feelings of others, shallow or superficial expression of emotions, and low guilt and remorse. Youth with high levels of CU traits also show a more severe, aggressive, and stable pattern of antisocial behaviour (Frick & White, 2008). This includes a reduced sensitivity to punishment and higher reward focused aggression (Wagner, et al., 2015).

The development of CU traits can be seen as a complex interaction between genetics and environment. Research has proven that there is a strong heritable factor present (Waller & Hyde, 2018; Pisano, et al., 2017; Waller & Hyde, 2017). The Gene x Environment interaction posits that children have a certain genetic susceptibility in developing for instance conduct problems, but it is the interaction with the environment, parenting among others, that will either stimulate the genetic susceptibility or mute it (Pluess & Belsky, 2011). Parenting is therefore an important, environmental factor that can either exacerbate or buffer genetic vulnerability in developing CU traits (Pisano, et al., 2017; Waller, et al., 2018; Clark & Frick, 2018; Fanti, et al., 2017; Waller & Hyde, 2017). When talking about parenting and parenting styles, studies have been dominated by Baumrind’s conceptualisation since the 1970s. The two basic dimensions of parenting styles were remarkably similar between different researchers. The underlying dimensions in the research of Symonds (1939), Baldwin (1955), Schaefer (1959), Sears et al. (1957) and Becker (1964) all come down to warmth/hostility and control/permissiveness. It was Baumrind however in 1966 who would come with an integrated theoretical model of conceptualisation of parenting style (Darling & Steinberg, 1993). She specified one broad parenting function, control, which was no longer organised linearly. Instead there could be three qualitatively different types of parental control distinguished: permissive, authoritarian, and authoritative. Permissive parenting scored the lowest on control, while authoritarian scored the highest. She also posited that parenting styles can be changed to how open the children are to parent’s efforts to socialize them (Darling & Steinberg, 1993).

The dimension of warmth/hostility plays an important role within the CU traits. When a child scores high on CU traits, this child often exhibits conduct problems (CP). Maternal involvement and positive parenting practises can facilitate that, despite high CU traits, the child does not display CP (Wall, et al., 2016). Positive parenting can also reduce the level of conduct problems in youth with high CU traits. A possible explanation is the reduced sensitivity to punishment that characterizes CU traits, making children less susceptible to punishment and more susceptible to positive reinforcements (Clark & Frick, 2018).

When looking at interaction between parenting and the level of CU traits, Wagner et al. (2019) investigated the influence of parenting in infancy to possibly predict high CU levels or CD in childhood. Using data from the Family Life Project, they found that maternal sensitivity in infancy predicts lower levels of callous-unemotional traits and conduct problems. Maternal harsh intrusion on the other hand predicted higher levels of CU behaviours. Nevertheless, no links were found between maternal harshness in infancy and conduct problems in the first grade (Wagner, et al., 2019). Pasalich et al. (2016) found that CU traits are more strongly associated with the affective quality of the child relationship and warmth. Harsh discipline and parent-child coercive circles appear to be more strongly associated with conduct problems (Pasalich, et al., 2016). When combining these two findings it could be hypothesized that harsh intrusion, and/or negative parenting styles do not have a strong influence on the emergence of aggression or defiance, but rather on the emergence of CU-related constructs such as lower sensitivity to punishment or lack of conscience (Wagner, et al., 2019).

According to Pisano, et al. (2017) positive parenting can buffer the risks of developing high CU traits and can even decrease CU levels. Especially maternal warmth is often correlated with lower levels of CU traits (Masi, et al., 2018).

In contrast to these findings, Muratoni, et al. (2016) did not find that higher levels of parental involvement or lower levels of harsh parenting predicted a decrease of CU during development. Low level of parental involvement and lower levels of socioeconomic status (SES) were related, however, to elevated levels of CU traits at the baseline (Muratoni, et al., 2016).

Fanti, et al. (2017) found that a negative family environment might even be associated with increased levels and stability of CU traits. The group with high stable levels of CU traits showed more negative family, school, and peer relations. While their parents scored high on distress and low on parental involvement (Fanti, et al., 2017). Waller, et al. (2018) concluded that parental harshness is associated with both CU traits and child aggression. Lower parental warmth was only related to the levels of CU traits (Waller, et al., 2018).

The link between parenting and CU traits however is not unidirectional. Harsh parenting can predict higher CU traits. High CU traits can cause negative modifications in parenting as well (Fanti, et al., 2017; Pisano, et al., 2017). According to Muratori, et al. (2016), this bidirectional relationship is only present in positive parenting. Lower levels of positive parenting can predict higher levels of CU traits. These higher levels can then predict lower levels of positive parenting. Negative parenting however did not have a similar relationship (Muratori, et al., 2016).

This growing body of evidence linking parenting to CU traits disproves the notion that CU traits develop uniquely under heritable genetic influence (Waller, et al., 2018).

In this thesis the emphasis will be on the correlation between age of onset, CU traits, and parenting. The first step is determining how many participants have childhood-onset CD (CO CD) and how many have adolescent-onset CD (AO CD). Next the presence of CU traits will be investigated. It is hypothesized that statistically significantly more youth with CO CD should have CU traits than youth with AO CD (Dandreaux & Frick, 2009).

Next, based on youth self-report, it will be checked if there are any noteworthy variations in parenting experienced by the participants. For this step, all participants were split into four groups, CO CD without CU traits (CO-CU), CO CD with CU traits (CO+CU), AO CD without CU traits (AO-CU), and AO CD with CU traits (AO+CU). First differences between the groups on harsh or warm parenting will be investigated. Next, harsh and warm parenting will be scrutinized in both the mother and the father figure, to explore whether differences can be contributed to either of them.

It will be studied if the group of CO CD experienced more harsh parenting relative to the group of AO CD. Additionally, it could be expected that the groups of CO+CU and AO+CU experienced more harsh parenting than the group of CO-CU and AO-CU.

Methodology

Participants and procedure

The sample consists of 16 to 17 year old boys that are staying in two different youth detention centres (YDC) in Flanders, Belgium. The participants were interviewed during their stay in the YDC by two PhD students, working within the Odysseus project of Dr. Colins. The first step into recruiting boys to participate was an official consent of the psychologist working at the YDC. All boys could participate in the study once the psychologist had approved their participation. Other exclusion criteria were a lack of knowledge of Dutch, acute psychosis and/or posing an acute danger to themselves or others. Participants were given an active informed consent to sign, while their parents were informed via a passive informed consent, stating that their son would participate in the study. When parents did not want their son to take part, they had to contact the PhD-students through email or telephone. If the participant signed the informed consent, he was interviewed and asked to complete a self-report questionnaire.

In total 152 boys were interviewed in the period between August 2019 and February 2020. The interviews of 139 boys were analysed on presence of CD and CU traits. For this thesis only boys with CD, according to DSM-IV criteria, were included (n=133).

Of those 133 participants, 75.2% were born in Belgium (n=100), 18.8% were born in another European country (n=25) with France (n=3), The Netherlands (n=8), Russia (n=4) and Slovakia (n=3) being the most common countries. Finally, 2.3% was born in Africa (n=3), 2.3% in Central- or South America (n=3), and 1.4% was born in Asia (n=2).

Considering the parenting component in the analysis, living arrangements of the participants before being placed in institutional care is an interesting boundary condition. Nine boys (6.8%) lived with only their father, while 56 boys (42.1%) stayed with their mother; 37 boys (27.8%) stayed with both their mother and father; 13 boys (9.8%) lived sometimes with their mother and sometimes with their father; while 18 boys (13.5%) stayed neither with their mother nor their father.

Instruments

The first instrument used in the present study is the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL) (Kaufman, et al., K-SADS-PL, version 1.0, 1996), translated in Dutch by Reichart, et al. (2001). The K-SADS is a semi-structured diagnostic interview designed to gather information on current and previous episodes of psychopathology in children according to the DSM-III-R and DSM-IV criteria (Reichart, et al., 2001). This interview has been updated according to the DSM-5 criteria in English (Kaufman, et al., 2016), but no Dutch translation is yet available. Many different affective disorders can be diagnosed with the K-SADS, but in this study the focus is only on CD diagnosis. Therefore, only that part of the interview was conducted. In theory both the child and parent(s) should be interviewed but considering that all participants are currently residing in a YDC, only the participants were interviewed and not the parent(s). The information given by the participants was supplemented with file information from among others the youth courts, social workers, and the psychologist.

Although the Dutch translation has not yet been examined on psychometric qualities (Nederlands Jeugdinstituut, 2020), the English version has, concluding reliable and valid diagnoses (Kaufman, et al., 1997).

The Clinical Assessment of Prosocial Emotions: Version 1.1 (CAPE) is a clinical assessment tool of CU traits in people between the ages of 3 and 21 (Frick, 2013). The CAPE has both a self-report interview and an informant interview. In this study the Flemish/Dutch translation was used. Considering the living arrangements of the participants only the self-report interview was used. This information was again supplemented with available file information.

A first promising study regarding the clinical utility of the CAPE 1.1 showed evidence of construct validity and criterion validity, although further research is warranted (Hawes, et al., 2019). Similar Spanish research showed adequate interrater agreement and internal consistency (Molinuevo, et al., 2020).

For the parenting aspect, the questionnaire developed for the Odysseus project was used. The questionnaire has 32 items that gauge harsh and warm parenting both from mother and father and is based on good practices of other questionnaires researching parenting, such as the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire, Child-to-Parent Conflict Tactics Scales, Positive Parental Affect, Hostile Parenting Scale. A full list of reference questionnaires can be found in attachment 3. The 32 items can be split in four groups of eight items, each representing one of the following categories: harsh parenting of the mother (P1-P8), warm parenting of the mother (P9-P16), harsh parenting of the father (P17-P24), and warm parenting of the father (P25-P32). The full questionnaire can be found in attachment 4. Considering that it is a newly developed questionnaire, no information on psychometric qualities is available.

Data-analysis

A frequency table was used to determine how many participants have childhood-onset (CO) CD and how many have adolescent-onset (AO) CD.

To evaluate if there was a significant relation between age of onset and presence of CU traits, a binary logistic regression was used. Age of onset was the dependent variable. Regression was opted considering it gives more information on influence than a correlation. At the same time the participants were split into four groups, two groups in CO CD, one without CU traits (CO–CU) and one with CU traits (CO+CU). The same groups were formed in the AO CD group (AO–CU and AO+CU).

To examine the parenting component of the study, first two new parenting variables were determined, Harsh Parenting (HP) and Warm Parenting (WP), by taking the sum of all items that referred to respectively harsh parenting or warm parenting. To investigate if between the four groups of participants differences in experienced parenting were noticeable, an ANOVA analysis was conducted. Post hoc test of Tukey was used to see between which groups differences were statistically significant. If there was no homogeneity of variances, the Games-Howell post hoc test was used.

In the final step HP and WP were split in 4 new variables, being Harsh Parenting Mother (HPM), Harsh Parenting Father (HPF), Warm Parenting Mother (WPM), and Warm Parenting Father (WPF). The same way of ANOVA analysing was used to explore where the groups experienced significant differences in parenting. All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 26 (IBM, 2019).

Results

Descriptive statistics

As mentioned before, only boys that have CD according to the K-SADS were included in this study. Of those 133 boys, 56 or 42.1% had childhood onset CD. The other 77 or 57.9% had adolescent onset CD. When looking at the number of boys with CU traits, the CAPE results showed that 70 boys or 52.6% had CU traits, while 63 boys or 47.4% did not show CU traits.

Combining those two counts, as done in Table 1, shows the four distinct participant groups in this study. There were no missing values in these variables.

Table 1

Cross table: age of onset of CD and presence of CU traits

What is the age of onset of CD? Total

childhood onset adolescent onset Does the participant have CU traits? No Count 24 39 63

% within What is the age of onset CD?

42,9% 50,6% 47,4%

Yes Count 32 38 70

% within What is the age of onset CD?

57,1% 49,4% 52,6%

Total Count 56 77 133

% within What is the age of onset CD?

100,0% 100,0% 100,0%

To analyse the results from the parenting questionnaire, the sum of scores relating to warm or harsh parenting was used. The computed variable Warm Parenting had a minimum score of 17 and a maximum score of 80 (µ=52.29, σ=17.79). Harsh Parenting had a minimum and maximum score of 11 and 80 (µ=34.37, σ=14.37). Both Warm and Harsh Parenting had a total of n=131.

Looking specifically at the mother figure, 130 boys completed the questionnaire, with a minimum and maximum score for warm parenting of 11 and 40 (µ=30.53, σ=7.77). For harsh parenting of the mother the scores are as follows: minimum of 8 and a maximum of 40 (µ=34.37, σ=14.37).

Focusing on the father figure, 113 boys completed the questionnaire, excluding 20 missing values. For warm parenting of the father there was a minimum score of 8 and a maximum score of 40 (µ=25.50, σ=10.97). For harsh parenting of the father the minimum score was 8 and the maximum score was 40 (µ=19.41, σ=9.58)

Missing values in the parenting variables are due to the participants not knowing their (biological) mother and/or father or not having a stable mother and/or father figure.

Correlation between age of onset and CU traits

Logistic regression was used to investigate the correlation between age of onset of CD and the presence of CU traits. No significant correlation was found between the variables with a p-value = 0.374, df =1, and χ²=0.791. In this study, age of onset of CD has no significant influence on the presence of CU traits.

ANOVA harsh/warm parenting

Although no significant relation was found between age of onset of CD and presence of CU traits, the participants will be split into the four groups (AO/CO +/- CU traits) during the ANOVA analysis. In the first ANOVA analysis differences are sought between experienced harsh and/or warm parenting. Considering the non-significant test of homogeneity of variances (p=0.944 for harsh parenting, p=0.052 for warm parenting), equal variances are assumed. Therefore, Tukey will be used in the post hoc tests. Considering the narrowly non-significant test for warm parenting, a Games-Howell post hoc test will also be conducted.

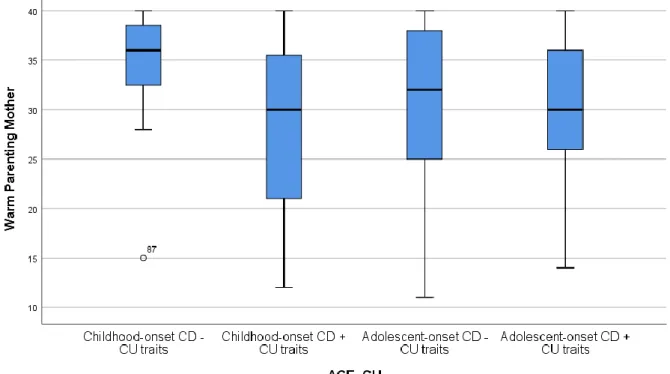

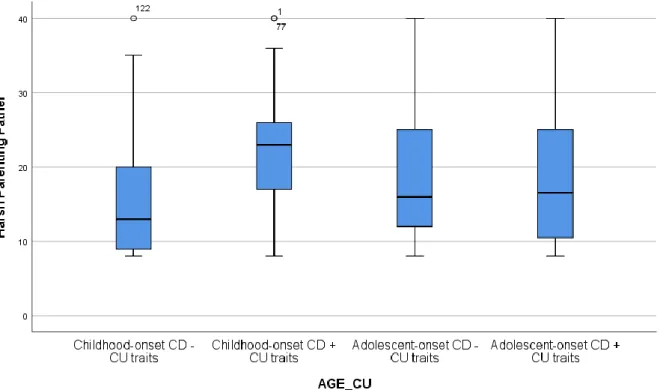

For warm parenting there are significant differences between the 4 groups with a p-value of 0.013 (SS=3313, df=3, F=3.709). Harsh parenting has a non-significant p-value of 0.101 (SS=1281, df=3, F=2.121). Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the distribution of scores on respectively warm and harsh parenting.

Tukey Post hoc testing showed that reported differences in warm parenting are significant between the group of CO–CU traits and CO+CU traits (mean difference=15.27, σ=4.717, p=0.008). Although not significant, differences are notable between CO–CU traits and AO–CU traits (mean difference=11.318, σ=4.559, p=0.067). Between the other groups p-values exceeded 0.25.

The Games-Howell post hoc test still showed significant results for differences between the CO-CU and CO+CU groups (mean difference=15.270, σ=3.908, p=0.001). Additionally, the results for CO-CU and AO-CU, also became significant (mean difference=11.318, σ=4.043, p=0.034). Results between other groups stayed non-significant.

Looking at the Tukey post hoc tests of harsh parenting there are no significant differences between any of the groups. Differences are most noticeable between CO+CU and AO–CU (p=0.105), CO+CU and AO+CU (p=0.208), and between CO–CU and CO+CU (p=0.267).

ANOVA warm parenting mother / father

Considering significant scores on warm parenting, the next step was to investigate if a difference can be found in warm parenting of the mother or warm parenting of the father. For warm parenting of the father, equal variances can be assumed due to p=0.857 on the test of homogeneity of variances. Therefore, Tukey is used in the post hoc testing. The test shows significant results for warm parenting of the mother (p=0.001), hence the use of Games-Howell in post hoc testing.

For warm parenting of the father there are no significant differences between the four groups with a p-value of 0.114 (SS=713, df=3, F=2.031). Warm parenting of the mother, however, has a significant p-value of 0.011 (SS=660, df=3, F=3.890).

Figure 3 shows the distribution of the scores on warm parenting of the mother over the four participant groups. This shows remarkable differences between CO–CU and the other groups. Post hoc testing confirms that there is a significant difference between CO–CU and CO+CU (mean difference=7.041, σ=1.970, p=0.004). Furthermore, between CO–CU and AO+CU there is also a significant result (mean difference=4.519, σ=1.572, p=0.029). Lastly between CO-CU and AO-CU, the difference is not significant (mean difference=4.283, σ=1.807, p=0.094). This shows that over the four groups, boys in the group of CO-CU experienced more warm parenting of the mother. Results between the other groups exceed p=0.5.

Post hoc testing for warm parenting of the father showed no significant results.

ANOVA harsh parenting mother / father

Although there was no significant result found in the general harsh parenting ANOVA, it is worth investigating if significant differences can be found when splitting the variable in the mother and father. Equal variances can be assumed both for harsh parenting of the mother (p=0.679) and harsh parenting of the father (p=0.626). During post hoc testing Tukey is used.

The ANOVA analysis yielded no significant results, nor for harsh parenting of the mother (p=0.337, SS=174.684, df=3, F=1.137), nor for harsh parenting of the father (p=0.077, SS=624, df=3, F=2.346). Considering the relatively close non-significance of harsh parenting of the father, post hoc testing was conducted, showing a narrow significant difference between CO-CU and CO+CU (mean difference=-6.975, σ=2.661, p=0.049), indicating that boys in the CO-CU group experienced less harsh parenting of the father compared to boys in the CO+CU group. All other post hoc tests were non-significant (p>0.35). Figure 4 shows a consistent distribution with the post hoc tests, showing relatively lower scores for CO-CU compared to CO+CU.

Discussion

The aim of this thesis was threefold. The first was to determine how many boys have CO CD and how many have AO CD. The prevalence of CD in general in this participant group was 95.5% (133 out of 139), while in the general population prevalence is estimated around 3% (Fairchild, et al., 2019). Results showed that 42.1% of the participants had CO CD, despite the assumption that the group of CO CD would be significantly smaller than the group with AO CD (Moore, et al., 2017). An Indian study with a clinical population also revealed that 85.7% of boys had CO CD (Jayaprakash, et al., 2014), consistent with the higher prevalence of CO CD in the present study. Research by Dandreaux and Frick (2009) with a clinical population also showed that more youth had CO CD than AO CD (Dandreaux & Frick, 2009), questioning the hypothesis that more youth suffer from AO CD rather than CO CD. It is possible that in a clinical population, with generally a more severe behavioural pattern and more persistent delinquent behaviour (Pardini & Frick, 2013), youth with CO CD are overrepresented. Considering that youth with CO CD show a more severe and persistent pattern of behavioural problems (Johnson, et al., 2015), this is not entirely unexpected.

Looking at the presence of CU traits according to the CAPE, 52.6% of boys have CU traits according to the CAPE. With prevalence numbers ranging between 12% to 46% (Fanti, 2018), the participants in the present study scored slightly higher. Youth with CU traits often show a more severe pattern of conduct problems than youth without CU traits. Boys placed in YDC have, in most cases, committed crimes (Agentschap Opgroeien, sd), so it can be argued that they display a more severe pattern of rule breaking behaviour regardless of the presence of CU traits. This pattern could also be allocated to the presence of CU traits.

Secondly, a correlation between age of onset of CD and presence of CU traits was predicted, in which youth with CO CD would have significantly more CU traits than AO CD. This study revealed no significant relation between the two. This in contradiction with the notion that CU traits are observed more in youth with CO CD (Dandreaux & Frick, 2009; Urben, et al., 2017). Although both studies did find their participants in a similar setting, age restrictions, group sizes and/or sex of the participants differ from this study. The Swiss study included both criminal law, civil law, and voluntary placements (Urben, et al., 2017), while the study of Dandreaux & Frick (2009) included participants following an outpatient treatment. Differences in the selection criteria could result in different results. A second analysis with more participants of the Flemish YCD might yield more significant results.

Finally, this study evaluated the levels of experienced parenting compared to the age of onset of CD and the presence of CU traits. Consistent with the studies of Masi et al. (2018) and Wagner et al. (2017), warm parenting differed between the four groups, with post hoc testing showing that especially between CO-CU and CO+CU differences were significant, showing youth with CO-CU reported significantly more warm parenting than CO+CU. Contrary to those studies it cannot be said for certain that warm parenting causes less CU traits, only that there is a difference in experienced parenting.

While most studies tried to get objective information on parenting (Wagner, et al., 2019; Masi, et al., 2018), this study focused only on experienced parenting by the participants. Research by Wagner et al. (2015) concentrated on the child’s representation of the family, with results indicating that greater dysfunctional family representation was significantly associated with higher CU behaviours, but not with more conduct

traits (Wagner, et al., 2015). How youth portray their families and how they experienced parenting, can give valuable information in the complex development of CD and CU traits.

As mentioned before, several studies look at the influence of parenting on CD and CU traits. In contradiction to the present study, not all of them differentiate between the mother and father (e.g. Clark & Frick, 2018; Fanti, et al., 2017; Muratoni, et al., 2016; Pasalich, et al., 2016). This leaves room for doubt as to whether parenting actually differs for these youths. The results of the present study specify that only warm parenting of the mother and harsh parenting of the father are significant, proving the value of distinguishing between the mother and the father.

Some studies do emphasize the importance of the mother figure in the development of CD and/or CU traits (Masi, et al., 2018; Wagner, et al., 2019). When warm parenting was split between mother and father figure, it became clear that significant differences were only found in experienced parenting of the mother. Youth with CO-CU reported more maternal warmth than youth with CO+CU and AO+CU. For the father figure no significant differences were reported, meaning all groups experienced a similar level of paternal warmth. While the studies are consistent, the method of gathering information differs between the present study and the study of Wagner et al. (2019). In the latter study maternal harshness was measured using a video recording in the home setting, while the present study exclusively relies on youth self-report. Moreover, these studies relied on how parenting in early life could or could not predict later conduct problems or CU traits. Research by Clark, et al. (2011) also found that maternal warmth was negatively correlated to conduct problems, but only in boys with high CU traits. This indicates that boys high on CU traits would show less behavioural problems if maternal warmth is high (Pasalich, et al., 2011). This somewhat contradicts the result of the present study that youth with CO+CU reported lower levels of warm parenting of the mother compared to CO-CU.

Lastly, differences in harsh parenting were investigated, with a narrow significant result for harsh parenting between the CO-CU and CO+CU. Further analysis revealed that harsh parenting of the father was narrowly significant, indicating that youth with CO+CU reported more harsh parenting of the father than CO-CU. Looking at the results, the differences between the groups are more significant for the mother figure than for the father figure. Studies making the difference between maternal and paternal parenting, often yielded similar results as in the present study, where the mother effects were larger than the father effects. A possible explanation could be that the mother in general spends more time with children (Bornovalova, et al., 2013). Looking at the data in the present study, more boys had a relatively stable mother figure. There were more missing values in the paternal part of the parenting questionnaire, indicating the absence of a stable father figure and supporting the notion that a mother spends more time with her children. Traditionally, stereotypical gender roles imply that the mother is responsible for raising the children and focuses on care while the father provides for the family and focuses on play (Pleck, 1979; Lamb, 2000). Especially in the last two decades however focus has shifted to acknowledge the importance of coparenting and father involvement (Pruett, et al., 2019). It would be too strong a statement to attribute differences only to a lack of presence of the father. Some studies with more longitudinal data started gathering data at young ages, both about behaviour and about parenting (Clark & Frick, 2018; Pasalich, et al. 2011; Pasalich, et al., 2016). Data about parenting was both gathered by parental observation and questionnaires, since the children were too young to question. Consistent with Pasalich, et al. (2016) the present study shows that warm parenting, especially by the mother, differs between the groups with or without CU traits, indicating that differences in young children could be maintained into adolescence. This indicates that the focus of research should not necessarily be on punitive

Although influence of parenting has been widely researched in relation to CD and CU traits (eg Masi, et al., 2018; Pisano, et al., 2017; Wall, et al., 2016; Waller & Hyde, 2018; Wagner, et al., 2015), caution in interpreting these results is necessary. Due to the use of cross-sectional data in this study, no statements can be made on the directivity of the differences. Do parents change their way of parenting because of the behaviour of their child or does the child develop certain behavioural issues due to the way of parenting? Studies have found evidences for both directions (Fanti, et al., 2017; Muratoni, et al., 2017; Pisano, et al., 2017). Additionally, it must be considered that any influence on a child’s behaviour is dependent on the child itself. Some children will be more susceptible to parental influences than others (Glenn, 2019) and there is ample evidence to suggest a certain level of genetic predisposition (Fairchild, et al., 2019). There is no way to predict whether or not an individual will develop CD or CU traits based on parenting circumstances considering the strong Gene x Environment interplay, nor is it possible to predict how parenting will change in the presence of CD and/or CU traits. Pretending to be able to do so, can have detrimental consequences both for the parents and the children.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study. First, most data were gathered using youth-self report. Additionally, file information was added when necessary and could nuance the information given by the participants. Considering all participants were staying in YDC, contacting and interviewing parents was not possible. When using youth self-report it is important to consider that the participants can give an altered version of reality and that they can give an alternate version of the truth. To minimize the self-report bias, file information was also used in making final determinations on the presence of CD and/or CU traits.

Secondly, the parenting questionnaire is newly developed. Although no research has been done on reliability or validity, it is based on good practises.

Thirdly, this study uses cross-sectional data. As mentioned before, the correlation between parenting and CU traits and/or CD is not unidirectional (Fanti, et al., 2017; Muratori, et al., 2016; Pisano, et al., 2017). Cross-sectional data does not allow to investigate continuity or discontinuity or the directionality of the associations. Significant differences can be found, but no conclusion on the causality can be made.

Fourthly, subtyping CD based on age of onset is not ideal. There is still a great diversity within the groups of childhood onset or adolescent onset CD (Pardini & Frick, 2013). Furthermore, the clinical usefulness of the limited prosocial emotions (LPE) specifier has also not yet been definitively proven. Recent research only found limited usefulness (Colins, et al., 2020; Colins, 2016; Jambroes, et al., 2016).

Lastly, this thesis focused on CU traits alone while recent research has widened the look on CU traits and has started to include CU traits into youth psychopathy (Colins, et al., 2018; Fanti, et al., 2018; Frogner, et al., 2018). Youth psychopathy is constructed using three factors, one of which is CU traits, the other two are impulsivity and grandiosity (Fanti, et al., 2018). Youth with high and stable levels of CD and CU often also show high levels of those other two psychopathic traits (grandiose-deceitfulness, need for stimulation, and impulsivity) (Klingzell, et al., 2016).

Strengths

The first strength of the present study is the use of a clinical population. By using the YDC to find participants, a high number of candidates fulfilled the conditions to be included in this study. Considering the low prevalence of CD in the general population, a clinical population provided a much higher prevalence in the sample, resulting in a high number of participants. Additionally, when dividing the total group of participants in the smaller groups according to age of onset and the presence of CU traits, the four groups had relatively similar numbers.

Although separately subtyping CD based on age of onset or CU traits only showed limited clinical usefulness, combining the two and creating four groups led to further insights in the relation between parenting, CD, and CU traits.

Next, youth self-report was used in order to gather data on parenting. Although this did not yield objective data on parenting, it did provide information on how the boys experienced parenting. Considering that some boys could be more susceptible to the influence of parenting than others (Glenn, 2019), objective data cannot indicate how the boys experienced it. While objective data could show harsh or warm parenting, it could have

Lastly, in analysing the differences in parenting, the present study differentiates between maternal and paternal parenting. Results show that significant differences between harsh or warm parenting could only be found when distinguishing between the mother and the father.

Conclusion

This study adds to the growing body of evidence linking parenting, CD, and CU traits. Although this study cannot comment on the direction of the interaction, it is clear that there are significant differences in experienced parenting between CO+/-CU and AO+/- CU. This indicates that further research into the differences between those four groups can yield important information in identifying and supporting both youth with CD (and CU) and their parents. A longitudinal study could try to discern in which direction the interaction is most significant.

Future research can focus on using both ways of subtyping, age of onset and presence of CU traits, to investigate if the combination of subtypes creates discernible groups within the population of youth with CD. The present study supports the notion that differences can be found between some of the four groups. Future studies can benefit from investigating differences between the mother and father figure, when looking at parenting in relation to CD and/or CU. The present study proved that warm or harsh parenting is not necessarily significant for both the mother and the father. In taking the two together into one variable, important information could be lost.

It would be interesting to see if the results of the present study can be replicated in a larger group of boys and if research with adolescent girls generates similar results. Additionally, the present study focused on a clinical group of boys, it would be interesting to investigate if a group of boys or girls with CD that do not reside within a YDC show similar trends and results in regard to parenting.

Acknowledgements

Writing this thesis has been a challenging but rewarding project. It was an opportunity to explore in depth my interest in behavioural problems, to learn how to critically look at results, and to try and find new possibilities. I would not have been able to finish this thesis, if it were not for the encouragements I got from supervisors, friends, and family. Some of them deserve a special mention for their support.

I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Olivier F. Colins, for the opportunity to work with the data collected in his Odysseus project and his guidance throughout the process.

I’m grateful to my thesis advisor, Cedric Reculé, for his patience, support, and trust in me. Your feedback helped me dive deeper and stay critical throughout the writing process.

I have greatly appreciated the support of Athina Bisback in the statistical part of this thesis.

I would like to recognize both Cedric Reculé and Athina Bisback for travelling to the youth detention centres and gathering the data used in this thesis. Without this, there would be none.

A special thanks to my brother, Pieter, for always being available to brainstorm, listen to my ideas and help me structure them. Your patience is truly appreciated.

Furthermore, I would like to thank my parents for the opportunity to let me continue studying to get my Master Degree. Without your support I would not be where I am today.

References

Agentschap Opgroeien. (sd). Gemeenschapsinstelling. Consulted on May 15, 2020, van Jeugdhulp: https://www.jeugdhulp.be/organisaties/gemeenschapsinstelling

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. (2018). Conduct Disorder. Consulted on May 16th, 2019, van

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry:

https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Conduct-Disorder-033.aspx

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.

Bergman, H., Maayan, N., Kirkham, A., Adams, C., & Soares-Weiser, K. (2015). Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS) for diagnosing schizophrenia in children and adolescents with psychotic symptoms. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011733 Bornovalova, M., Blazei, R., Malone, S., McGue, M., & Iacono, W. (2013). Disentangling the Relative Contribution of

Parental Antisociality and Family Discord to Child Disruptive Disorders. Personality Disorders, 4(3), 239-246. doi:10.1037/a0028607

Clark, J., & Frick, P. (2018). Positive Parenting and Callous-Unemotional Traits: Their Association With School Behavior Problems in Young Children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 47(Sup 1), S242-S254. doi:10.1080/15374416.2016.1253016

Colins, O. (2016). The clinical usefulness of the DSM-5 specifier for conduct disorder outside of a research context. Law

and Human Behavior, 40(3), 310-318. doi:10.1037/lhb0000173

Colins, O., Andershed, H., Salekin, R., & Fanti, K. (2018). Comparing Different Approaches for Subtyping Children with Conduct Problems: Callous-Unemotional Traits Only Versus the Multidimensional Psychopathy Construct.

Journal of psychopathology and behavioral assessment, 40(1), 6-15. doi:10.1007/s10862-018-9653-y

Colins, O., Van Damme, L., Hendriks, A., & Georgiou, G. (2020). The DSM-5 with Limited Prosocial Emotions Specifier for Conduct Disorder: a Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. doi:10.1007/s10862-020-09799-3

Cooke, D., & Michie, C. (2001). Refining the Construct of Psychopathy: Towards a Hierarchical Model. Psychological

Assessment, 13(2), 171-188. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.13.2.171

Dandreaux, D., & Frick, P. (2009). Developmental Pathways to Conduct Problems: A Further Test of the Childhood and Adolescent-Onset Distinction. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 375-385. doi:10.1007/s10802-008-9261-5

Darling, N., & Steinberg, L. (1993). Parenting Style as Context: An Integrative Model. Psychological Bulletin, 487-496. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487

Fairchild, G., Hawes, D., Frick, P., Copeland, W., Odgers, C., Franke, B., . . . De Brito, S. (2019). Conduct disorder.

Nature Reviews: Disease Primers, 5(1). doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0095-y

Fanti, K. (2018). Understanding heterogeneity in conduct disorder: A review of psychophysiological studies.

Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 4-20. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.09.022

Fanti, K., Colins, O., Andershed, H., & Sikki, M. (2017). Stability and Change in Callous-Unemotional Traits: Longitudinal Associations With Potential Individual and Contextual Risk and Protective Factors. American Journal of

Orthopsychiatry, 87(1), 62-75. doi:10.1037/ort0000143

Callous-Frick, P. (2009). Extending the Construct of Psychopathy to Youth: Implications for Understanding, Diagnosing and Treating Antisocial Children and Adolescents. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 803-812. doi:10.1177/070674370905401203

Frick, P. (2013). Clinical Assessment of Prosocial Emotions: Version 1.1 (CAPE 1.1). Opgehaald van https://sites01.lsu.edu/faculty/pfricklab/wp-content/uploads/sites/100/2015/11/CAPE-Manual.pdf

Frick, P., & White, S. (2008). Research Review: The importance of callous-unemotional traits for developmental models of aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(4), 359-375. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01862.x

Frogner, L., Andershed, A., & Andershed, H. (2018). Psychopathic Personality Works Better than CU Traits for Predicting Fearlessness and ADHD Symptoms among Children with Conduct Problems. Journal of psychopathology and

behavioral assessment, 40(1), 26-39. doi:10.1007/s10862-018-9651-0

Glenn, A. (2019). Early life predictors of callous-unemotional and psychopathic traits. Infant Mental Health Journal, 40, 39-53. doi:10.1002/imhj.21757

Hawes, D., Kimonis, E., Diaz, A., Frick, P., & Dadds, M. (2019, December). The Clinical Assessment of Prosocial Emotions (CAPE 1.1): A multi-informant validation study. Psychological Assessment, 32(4), 348-357. doi:10.1037/pas0000792

IBM. (2019, April 9). IBM SPSS Statistics 26 Documentation. Consulted on April 15, 2020, van IBM: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/ibm-spss-statistics-26-documentation

Jambroes, T., Jansen, L., Vermeiren, R., Doreleijers, T., Colins, O., & Popma, A. (2016). The clinical usefulness of the new LPE specifier for subtyping adolescents with conduct disorder in the DSM 5. European Child & Adolescent

Psychiatry, 891-902. doi:10.1007/s00787-015-0812-3

Jayaprakash, R., Rajamohanan, K., & Anil, P. (2014). Determinants of symptom profile and severity of conduct disorder in a tertiary level pediatric care set up: A pilot study. Indian Jounal of Psychiatry, 56(4), 330-336. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.146511

Johnson, V., Kemp, A., Heard, R., Lennings, C., & Hickie, I. (2015). Childhood- versus Adolescent-Onset Antisocial Youth with Conduct Disorder: Psychiatric Illness, Neuropsychological and Psychosocial Function. PloS one, 10(4), e0121627. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121627

Kaufman, J., Birmaher, B., Axelson, D., Perepletchikova, F., Brent, D., & Ryan, N. (2016, November). K-SADS-PL

DSM-5. Consulted on May 5, 2020, van Kennedy Krieger Institute:

https://www.kennedykrieger.org/sites/default/files/library/documents/faculty/ksads-dsm-5-screener.pdf

Kaufman, J., Birmaher, B., Brent, D., Rao, U., & Ryan, N. (1996, October). K-SADS-PL, version 1.0. Consulted on May 5, 2020, van http://www.icctc.org/PMM%20Handouts/Kiddie-SADS.pdf

Kaufman, J., Birmaher, B., Brent, D., Rao, U., Flynn, C., Moreci, P., . . . Ryan, N. (1997). Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children- Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): Initial Reliability and Validity Data. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(7), 980-988. doi:10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021

Klingzell, I., Fanti, K., Colins, O., Frogner, L., Andershed, A.-K., & Andershed, H. (2016). Early Childhood Trajectories of Conduct Problems and Callous-Unemotional Traits: The Role of Fearlessness and Psychopathic Personality Dimensions. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 47, 236-247. doi:10.1007/s10578-015-0560-0

Lamb, M. (2000). The History of Research on Father Involvement. Marriage & Family Review, 29(2-3), 23-42. doi:10.1300/J002v29n02_03

Lee, S. (2018). Multidimensionality of Youth Psychopathic Traits: Validation and Future Directions. Journal of

Masi, G., Pisano, S., Brovedani, P., Maccaferri, G., Manfredi, A., Milone, A., . . . Muratori, P. (2018). Trajectories of callous-unemotional traits from childhood to adolescents in referred youth with a disruptive behavior disorder who received intensive multimodal therapy in childhood. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment(14), 2287-2296.

Molinuevo, B., Martínez-Membrives, E., Pera-Guardiola, V., Requena, A., Torrent, N., Bonillo, A., . . . Frick, P. (2020). Psychometric Properties of the Clinical Assessment of Prosocial Emotions: Version 1.1 (CAPE 1.1) in Young Males Who Were Incarcerated. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 47(5), 547-563. doi:10.1177/0093854819892931 Moore, A. A., Silberg, J. L., Roberson-Nay, R., & Mezuk, B. (2017). Life course persistent and adolescence limited conduct disorder in a nationally representative US sample: prevalence, predictors and outcomes. Social

Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 4, 435-443. doi:10.1007/s00127-017-1337-5

Muratoni, P., Lochman, J., Manfredi, A., Milone, A., Nocentini, A., Pisano, S., & Masi, G. (2016). Callous unemotional traits in children with disruptive behavior disorder: Predictors of developmental trajectories ans adolescent outcomes. Psychiatry Research, 236, 35-41. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.003

Muratori, P., Lochman, J., Lai, E., Milone, A., Nocentini, A., Pisano, S., . . . Masi, G. (2016). Which dimension of parenting predicts the change of callous unemotional traits in children with disruptive behavior disorder? Comprehensive

Psychiatry, 69, 202-210. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.06.002

Nederlands Jeugdinstituut. (2020). Kiddie-SADS-lifetime versie (K-SADS-PL). Consulted on May 5, 2020, van Nederlands Jeugdinstituut: https://www.nji.nl/nl/Databank/Databank-Instrumenten/Zoek-een-instrument/Kiddie-SADS-lifetime-versie-(K-SADS-PL)

Oxford, M., Cavell, T., & Hughes, J. (2003). Callous/Unemotional Traits Moderate the Relationship Between Ineffective Parenting and Child Externalizins Problems: A Partial Replication and Extension. Journal of Clinical Child and

Adolescent Psychology, 32(4), 577-585. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_10

Pardini , D., & Frick, P. (2013). Multiple Developmental Pathways to Conduct Disorder: Current Conceptualizations and Clinical Implications. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry = Journal de

l'Academie canadienne de psychiatrie de l'enfant et de l'adolescent, 22(1), 20-25.

Pasalich, D., Dadds, M., Hawes, D., & Brennan, J. (2011). Do callous-unemotional traits moderate the relative importance of parental coercion versus warmth in child conduct problems? An observational study. Journal of Child

Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(12), 1308-1315. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02435x

Pasalich, D., Witkiewitz, K., McMahon, R., & Pinderhughes, E. (2016). Indirect Effects of the Fast Track Intervention on Conduct Disorder Symptoms and Callous-Unemotional Traits: Distinct Pathways Involving Discipline and Warmth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(3), 587-597. doi:10.1007/s10802-015-0059-y

Pisano, S., Muratori, P., Gorga, C., Levantini, V., Iuliano, R., Catone, G., . . . Masi, G. (2017). Conduct disorders and psychopathy in children and adolescents: aetiology, clinical presentation and treatment strategies of callous-unemotional traits. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 43(84). doi:10.1186s/s13052-017-0404-6

Pleck, J. (1979). Men's Family Work: Three Perspectives and Some New Data. The Family Coordinator, 28(4), 481-488. doi:10.2307/583508

Pluess, M., & Belsky, J. (2011). Prenatal programming of postnatal plasticity. Development and Psychopathology, 23(1), 29-38. doi:10.1017/S0954579410000623

Pruett, M., Cowan, P., Cowan, C., Gillette, P., & Pruett, K. (2019). Supporting Father Involvement: An Intervention With

Community and Child Welfare–Referred Couples. Family Relations, 68, 51-67.

doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12352

Ray, J. (2018). Developmental patterns of psychopathic personality traits and the influence of social factors among a sample of serious juvenile offenders. Journal of Criminal Justice, 58, 67-77. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2018.07.004

Reichart, C., Wals, M., & Hillegers, M. (2001). Schema voor onderzoek van affectieve stoornissen en schizofrenie bij jongeren van 6 tot 18 jaar. Altrecht: AZR-Sophia.

Ridder, K. A., & Kosson, D. (2018). Investigating the Components of Psychopathic Traits in Youth Offenders. Journal of

Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 40, 60-68. doi:10.1007/s10862-018-9654-x

Sentse, M., Kretschmer, T., de Haan, A., & Prinzie, P. (2017). Conduct Problem Trajectories Between Age 4 and 17 and Their Association with Behavioral Adjustment in Emerging Adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 1633-1642. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0476-4

Silberg, J., Moore, A., & Rutter, M. (2015). Age of onset and the subclassification of conduct/dissocial disorder. Journal

of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 56(7), 826-833. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12353

Urben, S., Stéphan, P., Habersaat, S., Francescotti, E., Fegert, J., Schmeck, K., . . . Schmid, M. (2017). Examination of the importance of age of onset, callous-unemotional traits and anger dysregulation in youths with antisocial behaviors. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 26, 87-97. doi:10.1007/s00787-016-0878-6

Vaughn, M., Salas-Wright, C., DeLisi, M., & Qian, Z. (2015). The antisocial family tree: family histories of behavior problems in antisocial personality in the United States. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50, 821-831. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0987-9

Wagner, N., Mills-Koonce, R., Willoughby, M., Cox, M., & Family Life Project Key Investigators. (2019). Parenting and Cortisol in Infancy Interactively Predict Conduct Problems and Callous-Unemotional Behaviors in Childhood.

Child Development, 9(1), 279-297. doi:10.1111/cdev.12900

Wagner, N., Mills-Koonce, W., Willoughby, M., Zvara, B., Cox, M., & the Family Life Project Key. (2015). Parenting and children's representations of family predict disruptive and callous-unemotional behaviors. Developmental

Psychology Journal, 51(7), 935-948. doi:10.1037/a0039353

Wall, T., Frick, P., Fanti, K., Kimonis, E., & Lordos, A. (2016). Factors differentiating callous-unemotional children with and without conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(8), 976-983. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12569

Waller, R., & Hyde, L. (2017). Callous-Unemotional Behaviors in Early Childhood: Measurement, Meaning, and the Influence of Parenting. Child Development Perspectives, 11(2), 120-126. doi:10.1111/cdep.12222

Waller, R., & Hyde, L. (2018). Callous-Unemotional Behaviors in Early Childhood: The Development of Empathy and Prosociality Gone Awry. Current Opinion in Psychology, 20, 11-16. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.037

Waller, R., Gardner, F., Shaw, D., Dishion, T., Wilson, M., & Hyde, L. (2015). Callous-unemotional behavior and early-childhood onset of behavior problems: the role of parental harshness and warmth. Journal of Clinical Child and

Adolescent Psychology, 44(4), 655-667. doi:10.1080/15374416.2014.886252

Waller, R., Hyde, L., Klump, K., & Burt, S. (2018). Parenting Is an Environmental Predictor of Callous-Unemotional Traits and Aggression: A Monozygotic Twin Differences Study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and

Adolescent Psychiatry, 57(12), 955-963.

Waller, R., Wagner, N., Barstead, M., Subar, A., Petersen, J., Hyde, J., & Hyde, L. (2020). A meta-analysis of the associations between callous-unemotional traits and empathy, prosociality, and guilt. Clinical Psychology

List of acronyms

AO CD – Adolescent onset CDAO-CU – Adolescent onset CD without CU traits AO+CU – Adolescent onset CD with CU traits CAPE – Clinical Assessment of Prosocial Emotions CD – Conduct Disorder

CO CD – Childhood Onset CD

CO-CU – Childhood onset CD without CU traits CO+CU – Childhood onset CD with CU traits CP – Conduct problems

CU – Callous-unemotional traits

DSM-IV – Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition DSM-5 – Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition

K-SADS-PL – Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime version

LPE – Limited prosocial emotions YDC – Youth detention centre

List of Tables

Table 1. Cross table: age of onset of CD and presence of CU traits

List of Figures

Figure 1. Distribution of scores on warm parenting over four participant groups (CO-CU, CO+CU, AO-CU, AO+CU)

Figure 2. Distribution of scores on harsh parenting over four participant groups (CO-CU, CO+CU, AO-CU, AO+CU)

Figure 3. Distribution of scores on warm parenting mother over four participant groups (CO-CU, CO+CU, AO-CU, AO+CU)

Figure 4. Distribution of scores on harsh parenting father over the four participant groups (CO-CU, CO+CU, AO-CU, AO+CU)

Attachments

Attachment 1: DSM 5 criteria Conduct Disorder

A. A repetitive and persistent pattern of behaviour in which the basic rights of others or major age appropriate societal norms or rules are violated, as manifested by the presence of at least three of the following 15 criteria in the past 12 months from any of the categories below, with at least one criterion present in the past 6 months:

Aggression to People and Animals

1. Often bullies, threatens, or intimidates others. 2. Often initiates physical fights.

3. Has used a weapon that can cause serious physical harm to others (e.g., a bat, brick, broken bottle, knife, gun).

4. Has been physically cruel to people. 5. Has been physically cruel to animals.

6. Has stolen while confronting a victim (e.g., mugging, purse snatching, extortion, armed robbery).

7. Has forced someone into sexual activity. Destruction of Property

8. Has deliberately engaged in fire setting with the intention of causing serious damage. 9. Has deliberately destroyed others’ property (other than by fire setting).

Deceitfulness or Theft

10. Has broken into someone else’s house, building, or car.

11. Often lies to obtain goods or favours or to avoid obligations (i.e., “cons” others). 12. Has stolen items of nontrivial value without confronting a victim (e.g., shoplifting, but

without breaking and entering; forgery). Serious Violations of Rules

13. Often stays out at night despite parental prohibitions, beginning before age 13 years. 14. Has run away from home overnight at least twice while living in the parental or parental

surrogate home, or once without returning for a lengthy period. 15. Is often truant from school, beginning before age 13 years.

B. The disturbance in behaviour causes clinically significant impairment in social, academic, or occupational functioning.

C. If the individual is age 18 years or older, criteria are not met for antisocial personality disorder. Specify whether:

312.81 (F91.1) Childhood-onset type: Individuals show at least one symptom characteristic of conduct disorder prior to age 10 years

312.82 (F91.2) Adolescent-onset type: Individuals show no symptom characteristic of conduct disorder prior to age 10 years.

312.89 (F91.9) Unspecified onset: Criteria for a diagnosis of conduct disorder are met, but there is not enough information available to determine whether the onset of the first symptom was before or after age 10 years.

Specify if:

With limited prosocial emotions: To qualify for this specifier, an individual must have displayed at least two of the following characteristics persistently over at least 12 months and in multiple relationships and settings. These characteristics reflect the individual’s typical pattern of interpersonal and emotional functioning over this period and not just occasional occurrences in some situations. Thus, to assess the criteria for the specifier, multiple information sources are necessary. In addition to the individual’s self-report, it is necessary to consider reports by others who have known the individual for extended periods of time (e.g., parents, teachers, co-workers, extended family members, peers).

Lack of remorse or guilt: Does not feel bad or guilty when he or she does something wrong

(exclude remorse when expressed only when caught and/or facing punishment). The individual shows a general lack of concern about the negative consequences of his or her actions. For example, the individual is not remorseful after hurting someone or does not care about the consequences of breaking rules.

Callous—lack of empathy: Disregards and is unconcerned about the feelings of others. The

individual is described as cold and uncaring. The person appears more concerned about the effects of his or her actions on himself or herself, rather than their effects on others, even when they result in substantial harm to others.

Unconcerned about performance: Does not show concern about poor/problematic

performance at school, at work, or in other important activities. The individual does not put forth the effort necessary to perform well, even when expectations are clear, and typically blames others for his or her poor performance.

Shallow or deficient affect: Does not express feelings or show emotions to others, except in

ways that seem shallow, insincere, or superficial (e.g., actions contradict the emotion displayed; can turn emotions “on” or “off” quickly) or when emotional expressions are used for gain (e.g., emotions displayed to manipulate or intimidate others).