COMPARITIVE

MINDSET

IN

THE

SUPERMARKET: IMPACT OF GIVING

A CHOICE ON PURCHASES

Jarryt Hardy

Student number : 01306635

Promoter: Prof. Dr. Hendrik Slabbinck

Master thesis nominated to obtain the degree of:

Master of Complementary Studies in Business Economics: Business Economics

Confidentiality clause

Permission

Undersigned declares that the content of this master dissertation can be consulted and/or reproduced, if cited.

Samenvatting

Achtergrond: Het aankoopbeslissingsproces van de consument is een concept dat door

allerhande factoren wordt beïnvloed. Handige marketeers prikkelen deze processen nauwgezet opdat deze kunnen worden gestuurd in een gewenste richting. Onderzoek heeft aangetoond dat wanneer consumenten voor een keuze worden geplaatst, dit een ‘comparative mindset’ induceert die de aankoopintentie van een volgende beslissing zou verhogen. Hypothetisch, zouden we op deze manier consumenten ertoe kunnen aanzetten gezondere aankopen te verrichten in de supermarkt, wanneer deze voor een keuze worden geplaatst in de fruit- en groenten afdeling.

Methode: Het aankoopgedrag, met betrekking tot fruit en groenten, van deelnemers werd

beoordeeld door middel van een online enquête. Enkele deelnemers werden, alvorens fruit en groenten aan te kopen, voor een keuze gesteld, de overige deelnemers beschikten niet over deze mogelijkheid. De hoeveelheid aankopen en de mate waarin voor variatie werd gezocht, werden beschouwd.

Resultaten: De voorafgaande beslissing beïnvloedde de hoeveelheid aangekochte fruit en

groenten niet significant. Soortgelijke resultaten werden bevonden na het includeren van verschillende covariaten. Daarnaast, werd vastgesteld dat de relatie tussen de voorafgaande beslissing en de hoeveelheid aangekochte producten door leeftijd werd gemodereerd. Uiteindelijk werd vastgesteld dat de voorafgaande beslissing ook geen significante invloed had op de mate waarin de deelnemers zochten naar variatie in de aangekochte producten.

Besluit: Resultaten van het onderzoek leidden tot de vaststelling dat de voorafgaande

beslissing het gedrag van de deelnemer niet wist te beïnvloeden. Het gebruik van de ‘comparative mindset’ in de supermarkt is dan ook nog af te wachten. Verder onderzoek zal moeten uitwijzen of deze resultaten kunnen worden vastgesteld in een werkelijke context.

Preamble

Originally, we wanted determine whether pre-purchase decisions would have an impact on the amount of purchased products in a scenario that approaches reality. Therefore, it was intended to conduct the study in the consumer laboratory of the University of Ghent. Conducting the experiment in this setting would have made the applied manipulation more tangible and authentic. Unfortunately, the corona pandemic restricted us from conducting our research in the consumer laboratory and, therefore, hindered the course of this master dissertation.

The Corona pandemic urged us to reshape the experimental design and pushed us towards using an online questionnaire to collect the required data. No other pivotal changes were carried through due to the corona pandemic. Obviously, in order to transfer the manipulations to the participants, graphical tools needed to be used. Further, it was decided to hold on to the between-subject design, as we intended to do. Hence, we only had to miss the supermarket setting created in the laboratory. Although, it is believed that this small change in experimental design affected our outcomes, it is believed that we acted properly.

This preamble is drawn up in consultation between the student and the supervisor and is approved by both.

Contents

1 Preface ... 1

2 Literature study ... 3

2.1 Consumer purchase process ... 3

2.1.1 Needs awareness ... 4

2.1.2 Information search ... 4

2.1.3 Evaluation of alternatives... 5

2.1.4 Purchase decision ... 7

2.1.5 Post purchase ... 7

2.2 Goal directed activities ... 8

2.2.1 Deliberative ... 8

2.2.2 Non-deliberative... 10

2.3 Comparative mindset ... 11

2.3.1 conceptualization ... 11

2.3.2 Effects on customers’ behaviour ... 11

2.3.3 Actual purchase behaviour ... 14

3 Hypothesis ... 15 4 Methodology ... 17 4.1 Sample ... 17 4.2 Study design ... 17 4.3 Procedure ... 18 5 Results ... 20

5.1 Chronbach’s alpha and recoding ... 20

5.2 Manipulation check ... 20

5.3 Altered purchase behaviour through a comparative mindset ... 21

5.3.2 Effect on variety purchased products ... 26

5.3.3 Additional remarks ... 28

6 Discussion ... 29

7 Conclusion ... 34

8 Practical implications ... 35

9 Restrictions and rationale for future research ... 36

10 References ... 38

11 Appendix ... 41

11.1 Questionnaire ... 41

11.2 SPSS output ... 51

11.2.1 Boxplot analysis of the dataset ... 51

11.2.2 Descriptive statistics of the dataset ... 51

11.2.3 Cronbach’s alpha general health interest ... 51

11.2.4 Cronbach’s alpha attitude towards environment ... 52

11.2.5 Altered purchase behaviour on the amount of purchased products ... 53

11.2.6 Altered purchase behaviour on the amount of purchased sorts ... 58

11.2.7 Satisfaction measure for purchase across conditions ... 61 11.2.8 Correlation between satisfactory and the representativeness of the products 61

1

1 Preface

Daily, customers assail supermarkets to provide themselves with fundamental goods and additional needs. While shopping, customers endure various stimuli that alter the way they behave, without contemplating the consequences of these alterations. For decades, marketing research groups have been exploring the aspects and issues of consumers’ decision processes extensively. Several research groups have turned their attention to conceptualizing a particular process that causes customers to deviate their decision process and influence their purchase behaviour.

The conceptualization embodies the perception of a state of mind, triggered during the decision making stage in the customer’s buying process. Exposing consumers to choice-alternatives and decision-making situations induces a state of mind that alters the consumers’ behaviour. Among other, researchers demonstrated an increased willingness to purchase with consumers who were previously asked to choose between alternatives. Moreover, they have described that the willingness to purchase even was increased in domains that were not related to the prior decision making situations (Xu & Wyer, 2007, 2008).

When it comes to scrutinizing the consumers’ purchase behaviour, these insights are considered pioneering work. Yet, the conditions and outcomes of these concepts have not been explored entirely. Heretofore, researchers have created conditions that demonstrated and confirmed their hypotheses, concerning the stimulated state of mind, still these conditions seem to be too distant from real-life situations. No consumer evaluates the attributes crucial for partner selection and subsequently determines which cell phone to purchase. Hence, few to no studies have been conducted to put these concepts to practice. Therefore, we aimed to demonstrate the effectiveness of the state of mind in the consumers’ daily life. Particularly, we attempted to demonstrate the effects of the described state of mind while purchasing products through an online questionnaire.

Altering the consumers’ purchase behaviour lies at the base of a broad range of applications. The soaring increase in obesity prevalence, despite many public health efforts to improve nutrition, has taken research groups’ interest in its application to change customers’ health behaviour (Hollands et al., 2013). According to the world health organization (World health

2

organization, 2020, obesity and overweight), obesity rates worldwide have been tripled since the seventies. Furthermore, rates have increased irrespective of geographical locality, ethnicity or socioeconomic status (Chooi, Ding & Magkos, 2019). Environmental interventions, that require minimal conscious engagement and reach many customers simultaneously, such as reshaping choice architecture, are able to alter the customers’ behaviour in a predictable way (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009). For that reason, it is our intention to shift customers’ purchase intention towards healthier choices in their decision making process by means of these nudging techniques described by Thaler and Sunstein (2009). Hence, stimulating the considered state of mind, triggered during the decision making stage in the buying process, in supermarkets could potentially give an answer to the global obesity epidemic. In other words, subjecting customers to choice-alternatives in the fruit and vegetable department, for instance, could turn customers to tend their budget towards healthier alternatives and engage in a more varied diet.

3

2 Literature study

2.1 Consumer purchase process

In order to understand why the customers’ behaviour and purchase decisions are easily influenced and altered, we need to delve into how and why customers purchase. Basic and already widely known marketing models, such as the stimulus-response model, define the elements that influence the customer’s behaviour. Both environmental and marketing stimuli are known to influence the buyer’s characteristics and decision process. In turn, the buyer’s characteristics and decision processes make up the consumers’ purchase decision (Kotler, 2000, chapter 5). Our experiments do not require further detail concerning the buyer’s characteristics. However, gaining insight on the stages of the consumer’s decision process is required to disclose at what stage the purchase decision is altered due to the triggered comparative judgement mindset.

The consumers’ decision process is typically visualized as a five-stage model (Kotler, 2000, chapter 5). Customers consecutively and routinely run through the following stages: Starting with problem recognition, the consumer advances to information search, evaluation of alternatives, purchase decision and concludes its purchase with post-purchase behaviour, as depicted in Figure 1. Although this model has its flaws, described as a “box and arrow” model by Jacoby (2002), it captures the full range of considerations that arise, adequately enough for our experiments, when facing a purchase.

Figure 1: Five-stage model for the consumer decision process. Needs awareness Information search Evaluating alternatives Purchase Decision Post purchase

4 2.1.1 Needs awareness

The decision process is set off when customers generate an awareness concerning certain needs or problems. The identification of needs is fueled by both internal (such as feelings of hunger) as external (such as seeing a commercial on television) stimuli (Kotler, 2000, chapter 5). Whether we act to fulfill the recognized need depends on how the customer perceives and attempts to assess the discrepancy between what we have and what we need (Bray, 2008). Hence, marketing strategies that boost our willingness to purchase are applicable in the first stage of the buyer decision process and are already widely used.

2.1.2 Information search

Then, customers decide to search for information from different sources, which have generally been categorized into internal and external sources. Internal sources are information sources developed in memory, through prior experiences, stored in the minds of the consumers. External sources, on the other hand, are sources of information that are pushed towards the customers throughout their daily lives (Schmidt & Spreng, 1996).

The extent to which customers search or reach out for information is based on the amount of risk that is associated with the purchase. Customers tend to lower their perception of risk associated with the purchase by searching additional information (Cho & Lee, 2006). However, searching for additional information is on its turn associated with search efficiency. Blay, Kadous and Sawers (2012) demonstrated that the customers’ attitude towards the products, being either positive or negative, plays a crucial role in information processing. Blay et al. (2012) merged their research and stated that negative emotions cause a focusing of attention that improves search efficiency in high-risk settings and that positive emotions cause distraction in low-risk settings, diminishing search efficiency. Hence, whether the search efficiency of the customer enhances both depends on the perceived amount of risk and the perceived emotions that are associated with the product. Decision making processes that are used for supermarket shopping belong to those low-risk settings. Hence, in these settings consumers long for a limited amount of information that can be processed rapidly. Kalnikaite, Bird and Rogers (2013) have concluded that several mobile apps that are created to give information to customers about certain products were evaluated as inconvenient and too overwhelming. Therefore, it is crucial to not overwhelm customers with too much information, in order to influence their decisions, and to concentrate on simple information.

5

Research groups have questioned themselves, to what extent appropriate product information influences the customers’ decision making (Kalnikaite, Bird & Rogers, 2013; Todd, Rogers & Payne, 2011). Currently, supermarkets have turned to use nudging techniques to persuade customers to make decision they would not have made otherwise by means of information disclosure. Todd et al. (2011) examined new ways for displaying informational nudges to guide customers towards healthier decisions. For instance, providing simplified nutritional information to the customer about the products put into their shopping carts might alter customers’ behaviour. Depending on the products ‘fat content’ or ‘carbon footprint’, an augmented handle bar, built into the shopping cart, alters its color. For example, a green handle would indicate that the cart’s contents are below the predetermined target, while a red handle suggests that the cart’s contents have a too large ‘carbon footprint’. Riding a shopping cart with a red handle bar might persuade customers to choose healthier alternatives.

2.1.3 Evaluation of alternatives

Gathering information on products might somewhat steer costumers towards a certain preference. Yet, Consumers find themselves each day in situation where the magnitude of alternatives is immense and might feel themselves impeded to attain their final decision. Opposed to John Stuart Mill’s described homo economicus, customers are not rational actors who evaluate all relevant choice alternatives, who process information effectively, efficiently and without bias (Mill, 1836). Lyengar and Lepper (2000) refuted the homo economicus model by illustrating that customers do have difficulty with managing complex choices. Lyengar and Lepper (2000) displayed either an extensive choice (of 24 jams) tasting booth or a limited choice condition (of 6 jams) to study participants and subsequently pursued to determine their purchase behaviour. While 30% of the customers in the limited-choice condition purchased a jar of jam, only 3% of the customers in the extensive choice booth did. Thus, consumers initially exposed to limited choices were considerably more likely to purchase the product than consumers who had initially encountered a much larger set of options. Lyengar and Lepper (2000) further concluded that customers appeared to be more satisfied with their decisions and purchases when they were exposed to the limited choice taste booth. Limiting choice alternatives in retail stores could therefore be assumed as an efficient nudging tool. However,

6

enlarging choice alternatives increases the chances of offering a preference match to consumers, turning this into a question of balance (Johnson, Shu , Dellaert et al., 2012). Hence, evaluating multiple alternatives and establishing a preference is a rather complicated, cognitive process. But how do customers succeed to attain their final judgement. Numerous evaluation models have been described in scientific literature. According to Lancaster (1966), it is assumed that items can be represented by the values they take on their combined attributes. Consumers see each product as a bundle of attributes that distinct them from other products. Each attribute (such as price, quality, size et cetera) might influence the customer’s purchase behaviour. However, attributes of interest to consumers vary by product. Additionally, which product attributes consumers perceive as most relevant and the importance they attach to each of these attributes varies among customers. Timmermans (1993) further examined the behaviour of customers concerning the application of the alternative evaluation by ranking attributes. Timmermans has described an increasing choice complexity, often defined in terms of the number of alternatives and/or the number of attributes on which the alternatives are evaluated, was accompanied by an expanded search for information. Moreover, Timmermans also stated that the amount of considered attributes per alternative decreased, associated with a decrease in information used per alternative. Hence, as the complexity of choices increases customers tend to simplify their decision-making processes by relying on simple heuristics, leading to a more efficient decision rule. Multiple in-store nudging tools, based on the evaluation of alternatives, have been designed to steer customers towards certain products or brands. A cost-effective nudging approach that significantly alters customers’ purchase decision is visibility enhancement (Cadario & Chandon, 2018; Vandenbroele, Slabbinck, Van Kerckhove & Vermeir, 2019). Vandenbroele et

al. have observed increasing sales of products that were more visible in comparison with other

products. Although visibility enhancement is broadly used in retail stores, it is not specifically applied to steer customers towards healthier purchase decision. Differently, Carroll, Samek and Zepeda (2017) focused on a health nudge that steers customers to purchase fruits and vegetables, comparable to our research objective. Carroll et al. suggested that healthy food bundles ought to be an effective and inexpensive display strategy. Moreover, food bundles might reduce consumers’ cognitive load by simplifying the shopping process and eventually

7

promote increased purchase of fruits and vegetables. These effortless in-store alterations have proven that choice architecture might offer solutions for the increasing obesity rates. 2.1.4 Purchase decision

Once the customer expressed a preference among the choice-set, he creates an intention to buy the preferred product. Still, no definitive decision or actual purchase has taken place. Moreover, research has demonstrated that multiple determinants can still defer the purchase decision. First and foremost, unanticipated/situational delay conditions may occur (Kotler, 2000, chapter 5). For example, the customer might sustain a loss of income and will be, in all probability, limited to complete its purchase decision.

Several decisive delay items, as well as delay closure items, have been described by Greenleaf and Lehmann (1995) after questioning 59 students. Delay closure items are thorough reasons to stop the delay process and move on to an actual purchase. These items are related to the amount of time spend on the decision-making process. Predominant reasons for deferring a decision were: Other things had higher priority, needed more extensive comparison of alternative prices, too busy to devote time to the decision and avoid any regrets over having made the wrong decision. Delay closure items mentioned by the students were: found time to finalize the decision, tired of the shopping process, prices were lowered by market and an increased need for the product was perceived by the customer. Greenleaf & Lehmann, ultimately, identified a relation between the motives for deferring a purchase decision and the delay closure motives. As the delaying period enlarges, delay closure motives will pile up and intensify. Eventually, these will manage the customer to complete its purchase and terminate the purchase decision stage.

2.1.5 Post purchase

Once customers purchase a certain product, they move on to the final stage of the consumer purchasing process. Purchasing and subsequently consuming the product enables the customer to experience the benefits and perceived performance provided by the product. Furthermore, it enables the customer to judge whether the attributes of the product satisfy their needs. Does the product surpass the gap between the former position of the customer (before purchasing the product) and the current position of the customer? The confirmation or refutation of prior expectations, the difference between the expected and perceived

8

performance, shapes the degree of satisfaction a customer perceives (Kotler, 2000, chapter 5). Through cognitive evaluations, the product’s utility has a direct effect on the degree of satisfaction. Utility and appearance do not only affect satisfaction, but are also reasons for people to consider a product as treasured and make customers attached to the product (Mugge, Schifferstein & Schoormans, 2010). In turn, post purchase customer perceptions are able to alter the customers behaviour and post purchase actions. For example, displeasure associated with a certain product might incite consumers to change brands or even to return the product (Kotler, 2000, chapter 5).

2.2 Goal directed activities

2.2.1 Deliberative

In order to meet their believed needs, customers determine goals along the purchase decision process . Tversky and Shafir (1992) stated that choice situations require both a goal that is not satisfied and at least two alternatives to attain it. By this means, the decision process will be considered as a series of goal-directed activities. Cognitive and motor actions, called procedures, are typically carried out sequentially to pursue goals related to the purchase process. Procedures are developed through the customers’ experiences and become part of the customers’ declarative knowledge (Wyer & Xu, 2010). Procedures are used continually and are therefore easily translated into day-to-day situations. Since procedures are stored in memory, customers are able to deliberately retrieve and practice these within the course of goal-directed processing.

Yet, goal attainment cannot be considered a straightforward process. We must keep in mind the appearance of additional concepts, at different levels, associated with the initial goal. Vallacher and Wegner (1987) described actions in terms of superordinate and subordinate goals. Superordinate goal attainment involves the inducement of multiple subordinate goals that need to be attained in order to actualize the superordinate goal. For example, the superordinate goal of the customer “see a play” incites the customer to “ arrange tickets” and “get to the theater”. In turn, these subordinate goals might trigger other concepts that need to be attained on a different level, and so on. A series of subordinate concepts, considered in combination, constitutes a plan. Wyer and Xu (2010) displayed the conceptualization of the given example in what they call a plan-goal hierarchy (Figure2).

9

Figure 2: Plan-goal hierarchy (Wyer & Xu, 2010)

Obviously, repeating certain procedures increases the accessibility of the procedure within the customer’s memory. Therefore, customer’s tend to resort to frequently used procedures (Anderson, 1982). Additionally, it has been described that procedures that were applied more recently seem more convenient to the customer and will be used more often. The probability of using a certain procedure depends on the similarity of its features to those of the situation in which the procedure is applied (Shen & Wyer, 2010). This implies that applying particular concepts in a repetitive way in the course of the customer’s experience generates chronically accessible concepts that require little cognitive mediation. If two or more plans are potentially feasible, the one that comes to mind most easily is considered, and a decision is made to attain the subordinate goals that compose it (Zanna & Olson, 2012).

10 2.2.2 Non-deliberative

According to Gollwitzer and Moskowitz (1996), customers’ cognitive capabilities are limited. Customers are unlikely to be aware of all the goals required or triggered during the purchase process. Particularly, attaining subordinate goals (for example, dial number in our example of going to the theatre) require little if any cognitive deliberation. Hence, with practice, procedures gradually become automated and are performed non-deliberative. The performance of certain concepts by non-deliberative means through repetition has been conceptualized by a cause-effect relationship, “if [X], then [Y]” (Wyer, Xu & Shen, 2012). The conceptualization considers [X] to be a configuration of stimuli and [Y] to be a sequence of cognitive or motor responses that are activated and performed automatically when the conditions specified in [X] are met. [X] includes both behaviour concepts and specific situational concepts. These concepts can be activated without noticing all of the stimuli that compose its precondition. Furthermore, not all of the features of a precondition need to be present in order to activate the behaviour associated with it. Rather, if an overall assessment of the situation is sufficiently similar to the concept’s precondition, the cognitive or motor response sequence, associated with it, will be spontaneously activated and applied (Wyer, Xu & Shen, 2012). Hence, the cause-effect relationship imply that while shopping, remarkably many of our decision take place through non-deliberative ways.

It needs to be emphasized that pursuing goal-directed activities in a non-deliberative way is an outcome caused by the automaticity of the underlying procedures. The transition from algorithm-based performance to memory-based performance is driven by the accessibility of former solutions , in comparable conditions, from memory. According to Logan (1988) the choice process can be modelled in terms of a race between the memory and the algorithm. Hence, whether goal-directed activities are tackled by means of deliberative or non-deliberative procedures is determined by the one that yields the most efficient and quick solution. Undoubtedly, over practice, memory-based performance will obscure algorithm-based performance and regulate our purchase behaviour.

11

2.3 Comparative mindset

2.3.1 conceptualization

In the course of the purchase decision process, customers are unintentionally forced to compare relevant choice alternatives. Supermarkets have dozens of tea flavours of multiple brands in their racks that provoke customers to compare them. Information used to substantiate these judgements originate from a deliberative mind-set. Once activated, these mind-sets persist to influence reactions on subsequent activities. Here, it is crucial to notice that subordinate goals are more likely to induce cognitive processes related to other subordinate goals that follow it than those that precede it. The reverse is true only if the outcome of the activity directed toward a subordinated goal is unsatisfactory (Xu & Wyer, 2007). This has direct implications for the consumer behaviour and can be extrapolated to the consumer decision process. As described in 2.1, customers tend to consecutively and routinely run through the stages of the decision process. Whenever customers immediately end up in the stage of evaluating alternatives they might neglect the previous stages and carry on to purchasing the product (Xu & Wyer, 2008). Hence, considering how to pursue a goal presupposes that a decision to pursue it has already been made. In other words, deciding which product to buy may not activate cognitive processes about whether to buy a certain product, only if the outcome of the activity directed towards a subordinated goal is unsatisfactory.

To epitomize, any situation involving comparative judgements appears to activate a “which-to-buy” mindset and seems to influence subsequent purchase decisions. So, purchase decisions processes can be reapplied at a later, decision stage without engaging in earlier stages of processing at all. Hence, it is assumed that shopping is likely to trigger the comparative mindset and therefore is going to define the underlying incentives for why we buy certain products.

2.3.2 Effects on customers’ behaviour

Xu and Wyer (2007) started assessing the effects of comparative judgements on the customers’ intention to buy and succeeded to demonstrate a relationship between customers’ intention to buy a certain product and whether or not the customer was formerly subjected to choice decisions. In one condition, participants first decided whether they would

12

want to buy one of two alternatives or would rather buy none of the suggested options. Afterwards, they had to consider which of the products they preferred. In a second condition, participants first indicated which of the two products they preferred and then, having done so, indicated whether or not they would want to buy the product. Xu and Wyer (2007) observed that participants subjected to the second condition were generally more likely to make a purchase. Xu and Wyer’s research basically altered the order of our purchase decision sequence and measured the effects in our purchase patterns. Furthermore, they noticed that the participant’s perception of the choice alternatives seemed to be more favourable in comparison with participants subjected to the first condition. Hence, evidence concerning the appearance of a comparative judgement mindset that alters customers’ willingness to buy had been proven under these experimental measures.

Consecutively, it was supposed that inducing a comparative judgement mindset by setting preferences is likely to be carried over to other relevant decisions, even to purchases in other domains. For instance, it was expected that participants are more likely to purchase a specific vacation package if they previously stated their preferred computer than if they considered whether to make a purchase in in the first place. This implies that the process of making domain-specific judgements brings a more general comparative judgement procedure about. In line with the plan-goal hierarchy conceptualization, these general comparative procedure-related concepts are capable of inducing other concepts that may be applied in other situations to which they are applicable, these may be distinctive from those that induced the general procedure in the first place (Wyer & Xu, 2010).

The “which-to-buy” mindset has also proved to decrease the participants’ sensitivity to risk associated with choices in an unrelated domain. Moreover, the perception of evaluating more favourable attributes for the computers, considered earlier, is transmitted to consecutive decisions. Therefore, customers perceive the attributes for the vacation packages to be more favourable (Xu & Wyer, 2008). Vice versa, evaluating less favourable attributes generates the perception of attributes to be less favourable in the consecutive decision. Hence, the specific nature of the initial decision does appear to induce selective attention to attributes in a consecutive decision. Nevertheless, participants’ likelihood of making a purchase decision did not depend on this difference in attention. This might indicate that the induced mindset by

13

these judgements may overrule the perception of more unfavourable perceived attributes (Wyer & Xu,2010).

In the models discussed above, comparative judgements are made in different product domains, yet, the comparative mindset might be triggered through judgements in non-product domains as well. For example, Wyer and Xu (2010) worded propositions in such a way that they induced agreeable opinions of participants. Participants in a second condition were given propositions that generated disagreeable state of minds. Priming with one of the described conditions activated, respectively, a bolstering mindset and a counter arguing mindset. Consecutively, the bolstering mindset led participants to evaluate a vacation package more favourably than those that induced a counter arguing mindset. Hence, these conclusions are in line with Xu and Wyer (2008), yet the described mindsets were triggered by non-product domains. This substantiates the broadness of situations that might be governed by a certain mindset.

Further, triggering the comparative mindset through comparative processes are conceivable regardless of whether the comparisons are evaluative or descriptive. Whether participants reported their preferences for the computers in the first domain or whether they compared the computers with respect to physical attributes would not alter the participant’s willingness to buy the vacation packages significantly. Also, comparison assessments through similarity judgements are capable of inducing an analogous mindset. Stimulating customers to consider the similarity between computers might contribute to an enlarged likelihood of purchasing one of the vacation packages in the second domain (Xu & Wyer, 2008).

In short, processes that induce the comparative mindset can be aroused by situations that are different from purchase decisions. For instance, one research group, Xu and Wyer (2008), speculates that the consumption of material goods may be greater during The United States’ election years than in off-election years. An analysis of U.S. personal consumption expenditures between 1929 and 2002 revealed that the average expenditure during presidential-election years was 2.2% greater than the average expenditure in the years immediately before and after. They assume that subjecting citizens to political campaigns and that the accompanied expressing of political preference between two candidates triggers consumers to increase their willingness to purchase, in line with the effects of their conceptualization of the state of mind.

14

It goes without saying that the observed effects of the prospected experiments cannot be neglected. First and foremost, the results are assumed to give us more insight on the general purchase decision processes and the influences on these processes. It is believed that many more daily decision making situations might affect our purchase patterns drastically. Moreover, these insight might bring about new marketing techniques or strategies within supermarkets that are worth investigating.

2.3.3 Actual purchase behaviour

Several research groups have examined the establishment and outcomes of the comparative judgement mindset. Still, few studies have analysed whether comparative mindsets drive actual purchase behaviour outside the study’s hypothetical scenarios. Xu and Wyer (2008) informed participants that they could purchase some left-over chocolates at half-price upon leaving the experiment. Results demonstrated that participants in mindset conditions, induced during the experimental session, are more likely to purchase chocolates than participants in control conditions. Although the described scenario stimulated actual purchase behaviour, we cannot directly extrapolate these insights to our daily shopping practices. For that reason, actual purchase behaviour elicited through comparative judgements should be examined more thoroughly.

15

3 Hypothesis

Heretofore, various research groups have observed alterations in customers’ behaviour through a comparative mindset. Nevertheless, few to none of these groups have thoroughly examined the applications of the comparative mindset in the field of daily shopping decisions. Supermarkets embody an epicentre of choices and, for that reason, are most likely a catalyst for comparative mindset processes.

A first hypothesis was raised from the consideration that stating preferences is likely to be carried over to other relevant decisions. Therefore, it should be questioned whether little in-store choices are sufficient to induce a comparative mindset and alter the customers’ behaviour towards healthier decisions. Inducing a comparative mindset in the fruit and vegetable department might for that reason steer customers towards purchasing more fruits and/or vegetables. To ascertain the effects of the comparative mindset on in-store behaviour, the participants’ fruit and vegetable purchases were evaluated in one condition where they merely had the option to store their purchases in plastic bags. In a second condition, participants were required to store their purchases in ecological reusable bags and in a third condition, participants needed to choose between storing their purchases in ecological reusable bags or plastic bags. More and more consumers are aware of environmental changes and adjust their purchase decisions towards more ecological standards. Several supermarket chains have therefore decided to distribute only reusable bags. In order to counter this, we intended to evaluate if comparable outcomes can be observed when participants had to choose between bags with similar characteristics, both reusable, but different in size.

Choosing between alternatives should induce a comparative mindset and boost the willingness to purchase more vegetables and/or fruits. Therefore, we assumed that participants, who had to choose between alternatives (conditions three and four), are more likely to purchase more vegetables and/or fruit in comparison with participants in conditions one and two. The described considerations gave rise to the following hypotheses:

H1a: When consumers have to deal with a choice alternative decision, their purchased amount of fruits and vegetables will be larger than when they did not have to compare the alternatives.

16

H1b: When consumers have to decide whether to choose an ecological or plastic bag, they will purchase more fruits and vegetables than when they do not have to make that decision. H1c: When consumers have to decide between reusable bags that are different in size, they will purchase more fruits and vegetables than when they do not have to make that decision. Shukla, Banerjee and Adidam (2013) observed that older individuals were more influenced by the end-of-the-aisle display proneness. Accordingly, older customers might be more prone to choice architecture and other nudging techniques. It should be considered whether the impact of pre-purchase choices on the amount of purchased fruits and vegetables is moderated by age. The notion on the moderation effect of age is described in the following hypothesis:

H2: The Relationship between pre-purchase choice and the amount of purchased fruits and vegetables is strengthened by age.

Research groups, discussing the comparative mindset, have primarily addressed their research to assess the effects on the intention to purchase. Considering the remarkable versatility of the comparative mindset, it is curious to check whether our described manipulation is also sufficient to change other behavioural patterns of the customers. For instance, an interesting behavioural purchase aspect is whether participants tend to seek for variety. Giving the fact that fruits and vegetables are products where consumers are looking for a lot of variety, the comparative mindset might stimulate that behaviour. The assumption that the comparative mindset encourages customers to look for variety, brings the following hypotheses about: H3a: When consumers have to deal with choice alternatives they will increase their purchased amount of sorts of fruits and vegetables than when they do not have to compare those alternatives.

H3b: When consumers have to decide whether to choose an ecological or plastic bag, they will purchase more sorts of fruits and vegetables than when they do not have to make that decision.

H3c: When consumers have to decide between reusable bags that are different in size, they will purchase more sorts of fruits and vegetables than when they do not have to make that decision.

17

4 Methodology

4.1 SampleThree hundred and twenty-seven individuals were questioned through an online survey to evaluate their purchase behaviour. Participants were randomly and evenly distributed over four conditions. Randomly assigning the participants ensured that all differences between the conditions were reduced to chance differences. The following parameters were used to exclude participants from the dataset. Participants that did not complete the survey were removed from the study (16.56%), as they withheld important information, needed for analysing the data accurately. Participants that failed to surpass both attention check questions (Appendix 11.1) were as well excluded from the study (19.33%). Also, participants that indicated that they are vegetarian were removed from the dataset (2.15%), as they are, in general, more likely to purchase more vegetables and fruits (Haddad & Tanzman, 2003). Ultimately, some of the participants were removed from the study because of aberrant values noticed while analysing the dataset (Appendix 11.2.1). Boxplot analysis led to the removal of six additional participants. All other residual participants were admitted to the dataset and were used to examine the hypotheses.

The input of 195 participants between 16 and 68 years old (M = 28.72, SD = 11.05), of which 54.9% were men, was used to conduct further analysis (Appendix 11.2.2). Table 1 displays the distribution of the participant over the four conditions after cleaning the dataset. Removal of the participants that failed to surpass the attention check questions and that did not complete the survey, led to a radical reduction of the amount of relevant input. Nevertheless, the total amount of included participants was perceived to be acceptable to consider our hypotheses. Condition 1 Condition 2 Condition 3 Condition 4

Participants 55 40 43 57

Table 1: Distribution of the participants over the four conditions.

4.2 Study design

In order to attain to our research questions, a between-subject study was conducted on the impact of choice architecture in supermarkets on the customers’ purchase decision process. The between-subject study design was based on a single independent variable, pre-purchase

18

choice through type of bags, and included four different conditions. In the first condition, participants merely had the option to store their purchases in a plastic bag. In a second condition, participants were required to store their purchases in an ecological reusable bag. Consecutively, in a third condition, participants were faced with the choice between storing their purchases in an ecological reusable bag or plastic bag. In a fourth condition, participants were asked to choose between bags with similar characteristics, both reusable, but different in size.

Through an online survey (Appendix 11.1), participants were asked to purchase products for three consecutive days as they would do in real-life shopping situations. Participants were told that the purchases should be sufficient to meet the needs of four family members (participant included). Hence, it was designed to reflect the shopping decisions of a standard Belgian family. Obtained data (Appendix 11.2.2) showed that the average family size of the participants (M = 3.42, SD = 1.30) approached an assumed family size of four individuals. In order to counteract possible effects of price differences, participants were told that the displayed products had identical prices. Therefore, there was no rationale to display prices in the online survey.

4.3 Procedure

The online questionnaire (Appendix 11.1) started with introducing the participants to the overall purpose of the study. Participants were told that their input would be used to unravel the customers’ purchase decision and promote healthy purchase behaviour in supermarkets. Participants were told to act like they were in their local grocery store, in the fruit-and vegetable section. Participants were randomly distributed into the conditions and were told in which bag to store their purchases (condition one and two) or were told to choose between different types of bags (condition three and four). Subsequently, participants were shown pictures of five different vegetables (cauliflower, broccoli, bell pepper, chicory and zucchini) and five different fruits (apple, pear, banana, melon and mango). Participants were asked to purchase fruits and vegetables in order to meet the needs of four family members (participant included) for three consecutive days. They were asked to indicate which products and how many of them they would like to purchase. Afterwards, famine and perceived happiness were measured, using seven-point bipolar scales. General health interest of the participants was

19

evaluated, using a validated eight-item seven-point Likert scale, designed by Roininen, Lähteenmäki and Tuorila (1999). Further, the participant’s attitude towards the environment was measured by means of a validated twelve-item seven-point Likert scale (Kim et al., 2012). Participants were questioned on the topic of sociodemographic variables and reported their age, gender, family size and whether or not they are vegetarian. Eventually, in order to check whether the participants had perceived the manipulation attentively, participants in condition one and two were asked in which type of bag they stored their purchases and participants in condition three and four were asked between which type of bags they had to choose to store their purchases.

20

5 Results

5.1 Chronbach’s alpha and recoding

To assess whether the items, stated in the described scales of the questionnaire (general health interest and attitude towards the environment), form in its entirety a reliable scale, two Cronbach’s alpha-tests were performed.

General health interest was determined by dint of an eight-item seven-point Likert scale. Cronbach’s alpha-test showed the questionnaire to have an acceptable reliability, α = 0.86 (Appendix 11.2.3). Moreover, the measured data substantiated the retention of all eight items. Removing one of the items would have resulted in a decrease of the value for α. The same procedure was applied to determine the participants’ attitude towards the environment. Cronbach’s alpha-test of the twelve-item seven-point Likert scale was carried out and resulted in a α that equaled 0.81 (Appendix 11.2.4). No incentives were observed to remove one or multiple items, as the removal of an item would not increase the α significantly.

5.2 Manipulation check

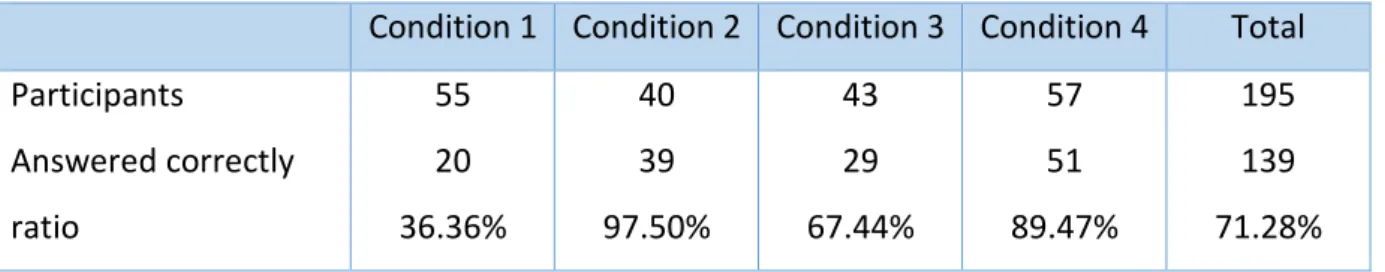

To determine whether the participants considered the manipulation unambiguously, a manipulation check was included in the questionnaire (Appendix 11.1). Overall, 71.28% of the participants managed to answer the manipulation check correctly. Remarkable, only 36.36% of the participants in condition one accomplished to answer the manipulation check appropriately. Further, Table 2 demonstrates that 97.50%, 67.44% and 89.47% participants in condition two, three and four, respectively, managed to answer the manipulation correctly. In consultation with the supervisor, the data of the participants who had failed to answer the manipulation check correctly were included in further analysis. This limitation of the research required to be scrutinized and is discussed in the discussion part.

Condition 1 Condition 2 Condition 3 Condition 4 Total Participants Answered correctly ratio 55 20 36.36% 40 39 97.50% 43 29 67.44% 57 51 89.47% 195 139 71.28%

21

5.3 Altered purchase behaviour through a comparative mindset

5.3.1 Effect on amount of products purchased

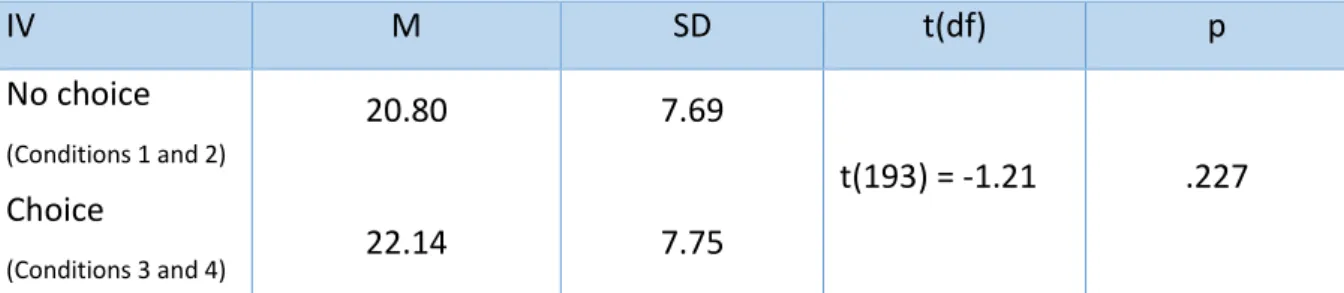

Literature had put us to question whether small in-store changes are sufficient to alter the customer’s behaviour and purchase decisions. In our experimental design, participants in condition three faced two alternatives, whether to store their purchases in a reusable or a plastic bag. Likewise, participants in condition four had to choose between two choice alternatives. Hypothesis H1a states that when consumers have to deal with an in-store choice decision, their purchased amount of fruits and vegetables will be larger than when they do not have to compare alternatives. Hence, it is of utter interest to consider the purchases made by participants in condition three and four in comparison with participants that did not have that opportunity to choose (conditions one and two). Thus, to refute or confirm hypothesis H1a, the purchases of participants in conditions one and two combined were compared with those of participants in conditions three and four combined by means of an independent samples T-test (Appendix 11.2.5.1).

IV M SD t(df) p No choice (Conditions 1 and 2) Choice (Conditions 3 and 4) 20.80 22.14 7.69 7.75 t(193) = -1.21 .227

Table 3: Independent samples T-test results for the amount of purchased fruits and vegetables. IV = independent variable, M = mean, SD = standard deviation, t(df) = t-test (degrees of freedom), p = probability value.

Table 3 demonstrates that the amount of purchased fruits and vegetables was not significantly higher when the participants had a pre-purchase choice decision to make (Mchoice = 22.14, SD = 7.75) relative to participants that did not have to make that decision (Mnochoice = 20.80, SD = 7.69; t(193) = -1.21, p = 0.227). Therefore, the independent samples T-test proved that hypothesis H1a should be refuted.

Although the independent samples T-test rejected hypothesis H1a, it is essential to conduct a pairwise comparison of the different conditions. An one-way ANOVA is used to determine whether there are any statistically significant differences between the means of the four conditions. Results for the one-way ANOVA-test are displayed in Table 4 and Table 5.

22 IV M F p Condition 1 Condition 2 Condition 3 Condition 4 19.55 22.53 22.28 22.04 1.66 .177

Table 4: One-way ANOVA results for the amount of fruits and vegetables purchased. A pairwise comparison of the four conditions. M = mean, F = F-Test, p = probability value.

Condition (I) Condition (J) Mean difference (I-J) p

1 2 -2.98 0.383 3 -2.73 0.495 4 -2.49 0.531 2 1 2.98 0.383 3 0.25 1.000 4 0.49 1.000 3 1 2.73 0.495 2 -0.25 1.000 4 0.24 1.000 4 1 2.49 0.531 2 -0.49 1.000 3 -0.24 1.000

Table 5: Bonferroni post-hoc test , pairwise comparison of the four conditions.

One-way ANOVA (Appendix 11.2.5.2) indicated that the amount of purchased fruits and vegetables did not significantly depend on the differences in the characteristics of the conditions (F(3,191) = 1.66, p = 0.177) (Table 4).

Specifically, the post-hoc test (Table 5) indicates that the amount of purchased fruits and vegetables was not significantly higher when the participants had to choose between the ecological and plastic bag (MCondition3 = 22.28) compared to participants in condition one (MCondition1 = 19.55, p = 0.495) or condition two (MCondition2 = 22.53, p = 1.000). Therefore, the one-way ANOVA demonstrated that hypothesis H1b must be refuted.

The post-hoc test (Table 5) also demonstrates that the amount of purchased fruits and vegetables was not significantly higher when the participants had to choose between reusable bags of different sizes (MCondition4 = 22.04) compared to participants in condition one (MCondition1 = 19.55, p = 0.531) or condition two (MCondition2 = 22.53, p = 1.000). Therefore, it must be concluded that hypothesis H1c should be rejected as well.

23 5.3.1.1 Covariates

In our experimental setup it is assumed that the number of purchased products are merely determined by the independent variable. Yet, it should be determined whether one or multiple covariates affect the dependent variable in a certain way. Covariance analysis (ANCOVA) was performed in order to reduce the variance error and to rule out potential effects on the dependent variable.

It could be reasoned that customers who care deeply about the environment tend to avoid high carbon footprint products, such as meat, and therefore turn to consume more fruits and vegetables. Therefore, the participants’ attitude towards the environment, measured by a twelve-item seven-point Likert scale (Appendix 11.1), was considered a first covariate that could alter the amount of purchased fruits and vegetables. The mean of the statements was measured to assess the participants’ attitude towards the environment. Descriptive statistics (M = 4.90, SD = 0.75) indicated that the observed population scored rather high on these statements (Appendix 11.2.5.3).

Participants’ general health interest was considered a second covariate that needed to be controlled for. Siegrist and van der Horst (2013) and Kriwy and Mecking (2012) stated that high health consciousness is accompanied by an increased consumption of fruits and vegetables. The mean of an eight-item seven-point Likert scale was used to describe the health interest for each participant. The participants mainly seemed to agree with the statements (M = 4.25, SD = 1.10) (Appendix 11.2.5.3).

Ultimately, the online questionnaire asked participants to what extent they were hungry while completing the questionnaire. Also, participants had to indicate how many hours there were between their last consumed meal and responding to the questionnaire. Both variables were positively correlated, merged into a principal component and used as a third covariate that needed to be controlled for.

The assumption of homogeneity of regression for all three covariates was met. (Appendix 11.2.5.4). ANCOVA (Appendix 11.2.5.5) was performed to control for the covariates and to check whether the non-significant differences still manifest themselves. Results for the ANCOVA are depicted in Table 6.

24 Variable F p Condition Mean_ENV Mean_GHI Mean_PC 1.39 0.11 8.26 0.71 0.247 0.740 0.005 0.401

Table 6: ANCOVA results for the amount of fruits and vegetables purchased, controlling for the environment covariate (ENV), the health interest covariate (GHI) and the component for hunger (PC).

Table 6 demonstrates that the amount of purchased fruits and vegetables did not significantly depend on the differences in the characteristics of the conditions, while controlling for the described covariates (F(3,188) = 1.39, p = 0.247). Incorporating the described covariate slightly drove the F-value towards one and the p-value farther away from statistical significance in comparison with the one-way ANOVA in 5.3.1 (F(3,190) = 1.66, p = 0.177). ANCOVA indicated that the participants’ general health interest significantly had an effect on the amount of fruits and vegetables purchased by the participants (F(1,190) = 8.26, p = 0.005).

5.3.1.2 Moderator effect of age

It is considered that the relationship between a pre-purchase decision and the amount of products purchased might depend on the age of the customer in question. The effect of the pre-purchase decisions on the amount of products purchased when changing age was assessed by means of a moderation analysis (Appendix 11.2.5.6). Hence, the participants that were exposed to the pre-purchase decision (both conditions three and four) were compared with those that did not have to compare the alternatives (both conditions one and two). In 5.3.1.1, ANCOVA demonstrated that the amount of purchased fruits and vegetables was influenced by the participant’s general health interest. Therefore, the moderation analysis included the general health interest variable, as a covariate (Appendix 11.2.5.6).

Variable B p LLCI ULCI

No choice vs. choice Age Condition*Age -5.20 -0.36 0.23 0.085 0.025 0.020 -11.13 -0.68 0.037 0.72 -0.05 0.423

Table 7: Moderation analysis for the effect of age on the amount of purchased fruits and vegetables. B = coefficient, p = probability value, LLCI = lower levels of confident interval, ULCI = upper level of confident interval.

25

Table 7 shows that the relationship between a pre-purchase decision and the amount of products purchased significantly depended on the customer’s age (B = 0.23, SE = 0.10, t(190) = 2.35, p = 0.020). The positive coefficient related to the interaction between the customer’s age and the manipulation (Table 7) indicated that age strengthens the main effect. Hence, moderation analysis confirmed hypothesis H2 that stated that the moderation effect of age strengthens the main effect of the pre-purchase decision on the amount of products purchased.

Figure 3: The impact of the pre-purchase choice decision on the amount of fruits and vegetables purchased under the influence of age. Mean –SD = 17.67, Mean = 28.72, Mean + SD = 39.76.

Figure 3 depicts that the effect of age on the relationship between the pre-purchase decision and the amount of purchased products increases as the participant’s age increases. Young participants (mean-SD = 17.67) that had to choose between the alternatives purchased less fruits and vegetables than young participants that did not. Yet, this difference in amount of purchased products was insignificant (B = -1.14, SE = 1.52, t(190) = -0.75, p = 0.453). Older participants (mean+SD = 39.76) that faced the pre-purchase decision purchased significantly more fruits and vegetables than older participants that did not face the alternatives (B = 3.94, SE = 1.53, t(190) = 2.58, p = 0.011). Additionally, floodlight analysis (Appendix 11.2.5.6) demonstrated that the influence of age is significant from the age of 32.32.

15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25

Mean - SD Mean Mean + SD

am o u n t o f F& V p u rc h ased Age

impact of pre-purchase choice on purchase behaviour under the influence of age

26 5.3.2 Effect on variety purchased products

The purchased sorts of vegetables and fruits were measured in order to determine whether presenting a pre-purchase choice could potentially alter the extent to which the participants seek for variety. Hence, adding up the purchased sorts (to the utmost of ten sorts of fruits and vegetables) would approximately represent the extent to which participants sought for variety. An independent samples T-test, comparing the combined measures for conditions three and four with the combined measures for participants in conditions one and two, was conducted to examine hypothesis 3a.

IV M SD t(df) p No choice (Conditions 1 and 2) Choice (Conditions 3 and 4) 6.99 6.86 2.07 2.02 t(193) = 0.44 .0.659

Table 8: Independent samples T-test results for the amount of purchased sorts of fruits and vegetables. IV = independent variable, M = mean, SD = standard deviation, t(df) = t-test (degrees of freedom), p = probability value.

Table 8 demonstrates that the amount of purchased sorts of fruits and vegetables was not significantly higher when the participants had a pre-purchase choice decision to make (Mchoice = 6.86, SD = 2.02) relative to participants that did not have to make that decision (Mnochoice = 6.99, SD = 2.07; t(193) = 0.44, p = 0.659) (Appendix 11.2.6.1). The independent samples T-test rejected hypothesis H3a.

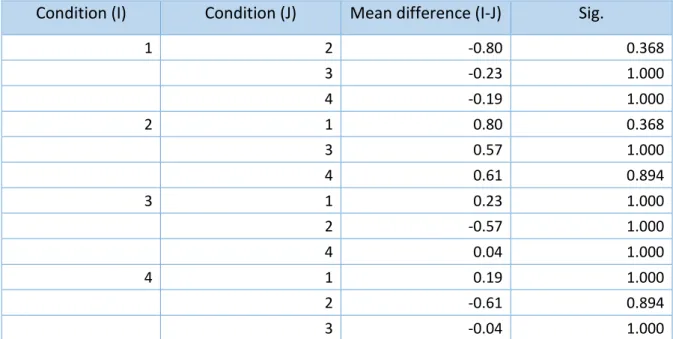

A pairwise comparison of the four conditions, by means of an one-way ANOVA, revealed potential differences in the means of the four conditions and was required to examine both hypotheses H3b and H3c. Results for the one-way ANOVA are depicted in Table 9 and Table 10. IV M F p Condition 1 Condition 2 Condition 3 Condition 4 6.65 7.45 6.88 6.84 1.25 .293

Table 9: One-way ANOVA results for the amount of purchased sorts of fruits and vegetables. A pairwise comparison of the four conditions. M = mean, F = F-Test, p = probability value.

27

Condition (I) Condition (J) Mean difference (I-J) Sig.

1 2 -0.80 0.368 3 -0.23 1.000 4 -0.19 1.000 2 1 0.80 0.368 3 0.57 1.000 4 0.61 0.894 3 1 0.23 1.000 2 -0.57 1.000 4 0.04 1.000 4 1 0.19 1.000 2 -0.61 0.894 3 -0.04 1.000

Table 10: Bonferroni post-hoc test , pairwise comparison of the four conditions.

One-way ANOVA (Appendix 11.2.6.2) showed that the amount of purchased sorts of fruits and vegetables did not significantly depend on the differences in the characteristics of the conditions (F(3,191) = 1.25, p = 0.293) (Table 9).

Specifically, the Bonferroni test (Table 10) indicates that the amount of purchased sorts of fruits and vegetables was not significantly higher when the participants had to choose between ecological and plastic bags (MCondition3 = 6.88) compared to participants in condition one (MCondition1 = 6.65, p = 1.000) or condition two (MCondition2 = 7.45, p = 1.000). The one-way ANOVA undoubtedly rejected hypothesis H3b.

Moreover, the post-hoc test (Table 10) illustrates that the amount of purchased sorts of fruits and vegetables was not significantly higher when the participants had to choose between reusable bags of different sizes (MCondition4 = 6.84) compared to participants in condition one (MCondition1 = 6.65, p = 1.000) or condition two (MCondition2 = 7.45, p = 0.894). Therefore, hypothesis H3c should be rejected as well.

5.3.2.1 Covariates

Covariates considered when examining the effects on the amount of purchased products (5.3.1.1) were re-examined here to consider significant differences among the means, when controlling for the covariates. The assumption of homogeneity of regression held for all three variables (Appendix 11.2.6.3).

28 Variable F p Condition Mean_ENV Mean_GHI Component 0.77 0.85 7.81 1.52 0.513 0.357 0.006 0.220

Table 11: ANCOVA results for the amout of purchased sorts, controlling for the environment covariate, general health interest covariate and hunger component covariate.

The ANCOVA showed that the amount of purchased sorts of fruits and vegetables did not significantly depend on the differences in the characteristics of the conditions, while controlling for the described covariates (F(3,188) = 0.77, p = 0.513). Similar to the effect of the participant’s health interest on the amount of purchased pieces, it was observed that the participants’ general health interest significantly had an effect on the amount of fruit and vegetable sorts purchased by the participants (F(1,190) = 7.81, p = 0.006).

5.3.3 Additional remarks

Participants that were randomly assigned to the third condition had to indicate whether they preferred to store their purchases in reusable or plastic bags. Frequency analysis demonstrated that 35 out of 43 participants (81.4%) indicated to use reusable bags. This goes in line with an overall high measured environmental awareness (M = 4.90, SD = 0.75).

Participants, in all four conditions, pointed out that their purchases brought about a satisfied sentiment (M = 5.39, SD = 1.56). ANOVA clarified that there were no significant differences observed between the different conditions (F(3,191) = 0.02, p = 0.996) (Appendix 11.2.7). Ultimately, participants indicated that they perceived the products to be representative for what they would purchase in real-life shopping situations (M = 5.21, SD = 1.35). Pearson correlation revealed that the level of satisfactory and the representative score were positively correlated. Participants that found the displayed products representative were, generally, more happy with their purchases (r = 0.26, p < 0.001).

29

6 Discussion

Several research groups have introduced the conceptualization of the comparative mindset and have authenticated its competence to alter an individual’s purchase behaviour (Xu & Wyer, 2007, 2008; Shen & Wyer, 2010). Still, that competence to affect one’s purchase behaviour had not been demonstrated in a real-life situational context. Therefore, the purpose of the experimental intentions described in this master dissertation was to demonstrate the significance of the effects of the comparative mindset for day-to-day shopping decisions. Small changes in the in-store choice architecture were examined to approach the comparative mindset.

The impact of pre-purchase decisions on the purchase behaviour was determined by means of an online questionnaire. One hundred and ninety-five individuals provided data related to their purchase behaviour in the fruit and vegetable aisles of a hypothetical supermarket. Participants were manipulated by allowing some of the participants to choose in which type of bag they preferred to store their purchases. Other participants were ordered to store their purchases in a specific type of bag and, thus, did not have the option to choose between two alternatives. The comparison of the shopping behaviour and the decision outcomes of the participants who were allowed to choose with the participants that did not, was the main point of attention in this master dissertation.

First and foremost, the amount of purchased pieces of fruits and vegetables did not differ significantly depending on the pre-purchase choice that had to be made by participants in both conditions three and four, rejecting hypothesis H1a. Further, the results, described in this dissertation, were not able to demonstrate significant differences between the amount of purchased products per condition. In other words, statistical analysis indicated that both hypotheses H1b and H1c needed to be rejected. Therefore, it is undeniable that the pre-purchase decision did not encourage customers to pre-purchase more products.

It should be noticed that our research did remarkably differ from Xu and Wyer’s (2007,2008) research. The research of Xu and Wyer (2007,2008) examined the intention to purchase a certain product, this differs remarkably from determining whether the comparative mindset alters quantitative measures of the concerned purchased product. Our aberrant outcomes in comparison with Xu an Wyer (2007,2008) do not refute previous findings and remarks

30

concerning the comparative mindset and its potential effects. In that respect, determining whether pre-purchase comparative judgements alter quantitative measures should be seen as a relevant next step in basic and translational research regarding the comparative mindset. Further, our results suggested that the amount of purchased sorts of fruits and vegetables did not differ significantly depending on the pre-purchase choice. Neither did the applied analysis indicate significant differences in the amount of purchased sorts of fruits and vegetables depending on the differences in the characteristics of the four conditions. These results urge us to conclude that hypotheses H3a, H3b and H3c needed to be rejected and that the comparative mindset did not stimulate participants to seek for variety.

Shen and Wyer (2010) demonstrated that when individuals were earlier urged to choose a different option of the same recurring choice alternatives, they would persist to search for different alternatives. Our results differ from Shen and Wyer, as we were not able to demonstrate an increased tendency to seek for variety. The number of purchased sorts did not significantly differ depending on having a pre-purchase choice. However, we need to make some additional remarks in order to nuance our aberrant results in comparison with other research groups.

In the first place, it should be questioned whether the applied manipulation was sufficient to induce a comparative mindset. Xu and Wyer (2008) demonstrated that when individuals have to state preferences among choice alternatives before contemplating a purchase decision between alternatives, the likelihood of choosing one of them increases, rather than rejecting them. It is assumed that our applied manipulation meets the requirements stated by Xu and Wyer (2008). However, it should be mentioned that just 71.28% of the participants managed to answer the manipulation check properly. Especially participants in condition one failed to answer the manipulation check correctly. Still, the unsuccessful manipulation check does not imply that the manipulation may have failed to influence the dependent variables. Nor does it suggest that participants did not attentively fill in the questionnaire because all of the included participants managed to answer both attention checks correctly. Remarks on the questionnaire elicited that participants might have interpreted the manipulation check as which bag they would have chosen when not being restricted by the experimental design, indicating that the manipulation check was misinterpreted by some of the participant. This