ENTREPRENEURIAL

ECOSYSTEMS

AND BUSINESS ACCELERATORS IN

LATIN AMERICA

ANALYSIS OF THE BRAZILIAN, MEXICAN, AND CHILEAN

ENTREPRENEURIAL ECOSYSTEMS AND ROLE BUSINESS

ACCELERATORS

Aantal woorden / Word count: 24.467

Stamnummer / student number : 01600424

Promotor / supervisor: Prof. Dr. Katja Bringmann

Co-promotor / Co-supervisor: Prof. dr. Katrien De Langhe

Masterproef voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van:

Master’s Dissertation submitted to obtain the degree of:

Master in Business Economics: Corporate Finance

Academiejaar / Academic year: 2019-2020II

Foreword

Before you lies the dissertation “Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Business Accelerators in Latin America”, an analysis of the entrepreneurial ecosystems in Brazil, Mexico and Chile and the role of business accelerators within these entrepreneurial ecosystems. The dissertation has been written to fulfil the graduation requirements of the master of science in business economics (Corporate Finance).

The writing of this dissertation was a great learning experience and further sparked my interest in entrepreneurship. I enjoyed learning about these countries and their strengths and weaknesses. I am grateful that this dissertation has not been affected by the corona measures.

First of all, I want to thank my supervisor, Katja Bringmann, for valuable feedback and guidance during this process. I want to thank my family and friends for supporting me. A special thanks to my friend Sofie, who has helped me fine-tune this text. Also, to my father for debating issues with me and the guidance. I hope you enjoy reading.

Lenka Chavée

III

Table of contents

Foreword II

List of used abbreviations V

List of tables, charts and figures VI

1. Introduction 1

2. Literature review 3

2.1. Relevance within the emerging markets context 3

2.2. The entrepreneurial ecosystem 6

2.2.1. Defining entrepreneurial ecosystems 6

2.2.2. Key actors and inter-relations within the EE 8

2.3. Defining Business Accelerators 13

2.3.1. Definition 13

2.3.2. Context of emergence 13

2.3.3. Design elements 14

2.3.4. Design themes 16

2.4. The role of the business accelerator within the entrepreneurial ecosystem 19

3. Methodology 23

3.1. Choice of countries 23

3.2. Analysis of the entrepreneurial ecosystem 24

4. Country profiles 27

4.1. Brazil 27

4.2. Mexico 29

4.3. Chile 30

5. Analysis of determinants of the entrepreneurial ecosystem 32

5.1. Brazil 32

5.1.1. Regulatory framework 32

5.1.2. Market conditions 35

IV 5.1.4. Entrepreneurial capabilities 39 5.1.5. Entrepreneurship culture 40 5.1.6. Summary 41 5.2. Mexico 44 5.2.1. Regulatory framework 44 5.2.2. Market conditions 47 5.2.3. Access to finance 49 5.2.4. Entrepreneurial capabilities 51 5.2.5. Entrepreneurship culture 52 5.2.6. Summary 53 5.2.7. Insights interview 55 5.3. Chile 58 5.3.1. Regulatory framework 58 5.3.2. Market conditions 61 5.3.3. Access to finance 62 5.3.4. Entrepreneurial capabilities 64 5.3.5. Entrepreneurship culture 65 5.3.6. Summary 66

6. Role of the business accelerator in the Brazilian, Mexican and Chilean entrepreneurial

ecosystems 69

7. Discussion 74

8. Conclusion 77

9. Reference List VIII

10. Annex XVIII

10.1. Attachment 1.1: Database business accelerators XVIII

10.2. Attachment 1.2 : Adapted OECD framework XXI

V

List of used abbreviations

ALMO Andres Manuel López Obrador

ALMP Active Labor Market Policy

BIVA Bolsa Institucional de Valores

BMV Bolsa Mexicana de Valores

BNDES the National Bank for Economic and Social Development

CORFO Corporación de Fomento de la Producción de Chile

EE Entrepreneurial ecosystem

EIP Entrepreneurship Indicators Program

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GEM Global Entrepreneurship Monitor

INADEM National Entrepreneurship Institute

IPR Intellectual Property Rights

LAVCA Latin American Venture Capital Association

MERCOSUR Mercado Commun del Sur

NAFTA North American Free Trade Agreement

OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

PE Private Equity

RIF Régimen Incorporación Fiscal

SME Small- and Medium Enterprise

SOE State-Owned Enterprise

SSE Santiago Stock Exchange

USD United States Dollar

USMCA United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement

USTR The Office of the United States Trade Representatives

VC Venture Capital

VI

List of tables, charts and figures

Tables

Table 1: Key actors and inter-relationships within entrepreneurial ecosystems ... 9

Table 2:Design themes ... 17

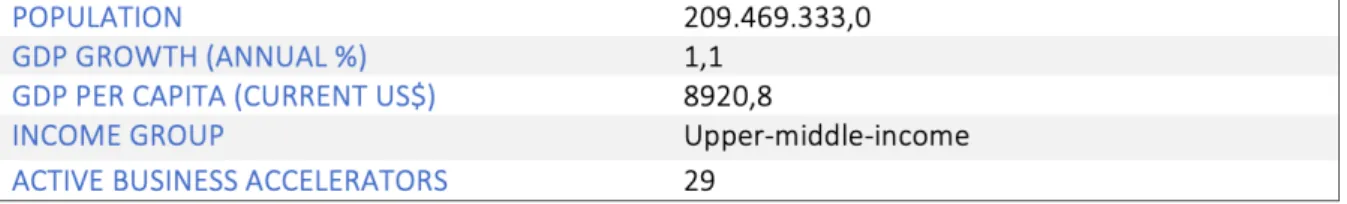

Table 3: Key figures Brazil ... 27

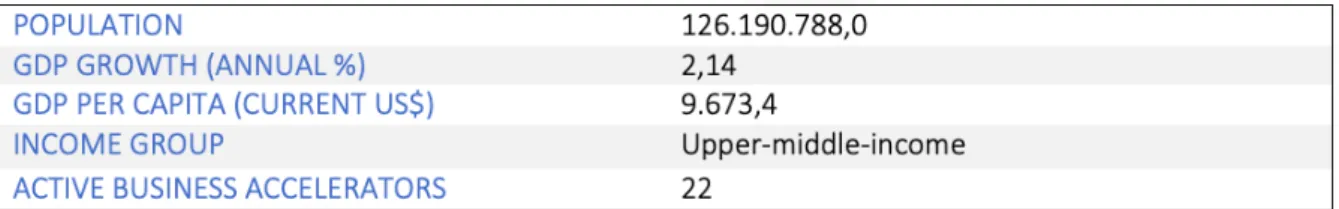

Table 4: Key figures Mexico ... 29

Table 5: Key figures Chile ... 30

Table 6: Summary Brazil ... 41

Table 7: Summary Mexico ... 53

Table 8: Key info interviewees ... 55

Table 9: Summary Chile ... 66

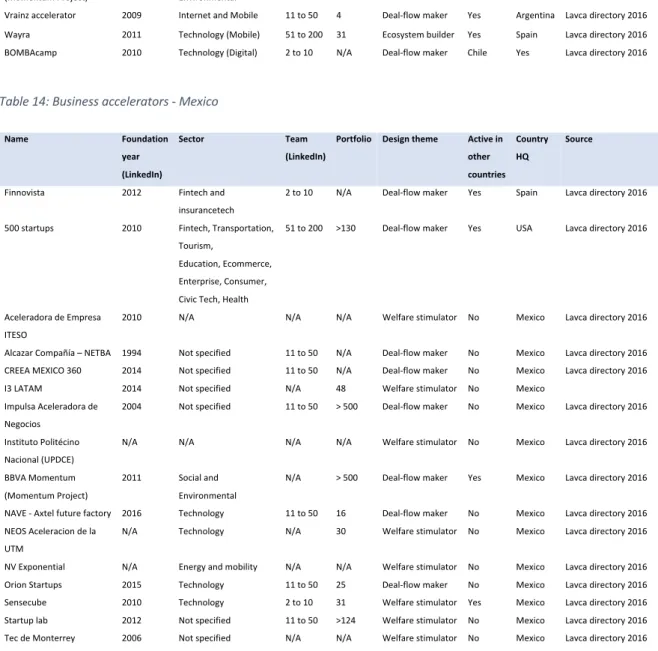

Table 10: Business accelerators - Argentina ... XVIII Table 11: Business accelerators - Brazil ... XVIII Table 12: Business accelerators - Chile ... XIX Table 13:Business accelerators - Colombia ... XX Table 14: Business accelerators - Mexico ... XX Table 15: Business accelerators - other Latin American countries ... XXI Charts Chart 1: Number of new business accelerators per year ... 14

Chart 2: Number of active business accelerators per country in Latin America ... 24

Chart 3: Design Themes Brazil ... 28

Chart 4: Design themes Mexico ... 29

Chart 5: Design themes Chile ... 31

Chart 6: Number of business accelerators founded per year ... XVIII Figures Figure 1: Structure of the literature review ... 3

Figure 2: Domains of the entrepreneurial ecosystem ... 7

VII

Figure 4:Conceptual framework Anchor tenant theory ... 19

Figure 5: Intermediary role of the business accelerator within the EE ... 20

Figure 6: OECD Framework ... 24

1

1. Introduction

Creating the next “Silicon Valley”. Over the past years this has become the major objective for policymakers, including Latin American ones. Boosting entrepreneurship has become a key pillar of sustainable economic growth. And high-growth startups have become key in this strategy to generate innovation and economic growth (Samila & Sorenson, 2011). Over the past decade startups and business accelerators have emerged all over the world. And this no different in Latin American emerging markets. Entrepreneurial activity is flourishing in Latin America. Especially bigger economies, like Mexico, Chile, and Brazil, developed flourishing entrepreneurial ecosystems. These economies use innovative entrepreneurship as a means to lift their economy to the next phase of development. It is well established that entrepreneurship contributes to economic development because it generates employment, innovation, and welfare (Schumpeter, 1934; Wennekers, Van Stel, Thurik, & Reynolds, 2005; Acs, Desai, & Hessels, 2008). Business accelerators play an important role in this process. They help startups grow and reach their potential. Moreover, they incite entrepreneurial activity growth, technological change, and innovation in the region (Colombelli, Paolucci, & Ughetto, 2019). Nevertheless, using entrepreneurship to boost the economy or creating thriving entrepreneurial ecosystems is a complicated process. In the past, many government have failed in creating thriving ecosystems by just implementing “best practices” or setting up business accelerators. Policymakers should look at what their region or entrepreneurial ecosystem needs (Hospers, Desrochers , & Sautet , 2009). And consider, that entrepreneurial activity depends on whole set determinants, ranging from the presence of knowledge centers to access to venture capital. But also, realize that the presence of business accelerators is not sufficient to create or sustain entrepreneurial activity, because the ecosystem wherein startups and business accelerators are active in impacts the dynamics of entrepreneurship. And the ecosystem is affected by the level of economic development and institutions. Therefore, it is important to analyze the nexus between business accelerators, entrepreneurial ecosystems, and emerging markets.

The aim of this dissertation is to analyze three Latin American entrepreneurial ecosystems wherein business accelerators are active and establish the role of business accelerators within these ecosystems. First, literature suggests that these ecosystems will differ from each other because every entrepreneurial ecosystem emerges under a different and unique set of conditions (Isenberg, 2016). Secondly, that the role

2 of business accelerators is dependent on the level of development of the ecosystem (Colombelli et al., 2019).

This analysis will be relevant for policymakers, who want to develop their economy. In this way, they can implement effective policy adapted to the needs and strengths of their economy. More importantly, for business accelerators, this analysis will be relevant to adapt their program design. They need to know what their participants need to grow their businesses in the ecosystem.

3

2. Literature review

2.1. Relevance within the emerging markets context

Over the last decades, some emerging markets, such as South-Korea, Israel, and Ireland, have successfully their transformed economies, both in terms of growth and institutional development. These countries succeeded in creating thriving entrepreneurial environments. In this way, they succeeded in developing their economies. In contrast, many Latin American countries are falling behind their peers. Like other emerging markets, Latin American countries have abundant natural recourses, large workforces, and have experienced high growth rates over the past decades. However, Latin American countries made less progress in terms of investment and saving rates, productivity growth, and innovation level. Moreover, poverty remains a major challenge. Therefore, the region has become less successful in improving their economies than other emerging markets (Blejier, 2006). Thus, Latin American countries seem to be stuck in their current stage of development.

It is generally agreed upon that entrepreneurship contributes to economic development because it generates employment, innovation, and welfare(Schumpeter, 1934; Wennekers et al., 2005; Acs et al., 2008). However, the impact of entrepreneurship differs between countries with different degrees of development. More importantly, the impact differs between countries with the same degree development, and even among regions within the same country (Autio, 2007). Therefore, even within Latin American countries with the same degree of development, the dynamics of entrepreneurship will be different. The

Emering Markets Entrepreneurial Ecosystems Business Accelerators

4 ecosystem in which entrepreneurs are active, affects the dynamics of entrepreneurship. This ecosystem is affected by the level of economic development and institutional context, which are in turn influenced by other determinants. Therefore, it is important to analyze the nexus between entrepreneurship, economic development, and institutions, in regions or countries. Insight in this nexus helps create an understanding of what induces or inhibits economic development (Acs et al., 2008).

This nexus can be analyzed by Porter’s theory. Porter defines economic development as “a process of successive upgrading, in which businesses and their supporting environments co-evolve, to foster increasingly sophisticated ways of producing and competing” (Porter, Sachs, & McArthur, 2002, p.17). Not only does economic development create economic stability, it also strengthens the quality of governance, increases innovative capabilities, develops the other competition modes, and so on. Key factors in the economic environment should change at the right time in order to develop. Economic development can stagnate due to a lack of improvement in certain factors. This means that countries can also get stuck between two phases of development. This theory argues that the competitiveness of a country can be divided into three stages of development: (1) factor-driven stage, (2) efficiency-driven stage, (3) innovation-driven stage; and transition phases between each of the different stages.

The first stage, the factor-driven stage, is characterized by the production of commodities or low value-added products and an unskilled workforce. Technology to produce these goods is imported and financed through foreign direct investment. So, these countries do not generate knowledge. Manufacturing is labor-intensive, focused on assembly, and barely integrated into the global value chains. Countries in this stage have high rates of non-agricultural self-employment, which is driven by necessity. These self-employed persons mostly have small manufacturing or service firms. In this stage, governments should provide economic and political stability, use the primary resources and workforce effectively, and attract foreign direct investment.

In the second stage, namely the efficiency-driven stage, firms are manufacturers or provide standard services. More sophisticated foreign technology is copied, and adopted, and increases domestic productivity. In other words, governments in this stage apply a more investment-based strategy, which associated with relying on large and older firms (Acemoglu, Zilibotti, & Aghion, 2006). Moreover, this stage is characterized by a decline in self-employment or entrepreneurial activity (Kuznets, 1973). A possible

5 explanation for this decline is the perception that workers can earn more when employed in a firm. In other words, as the capital stock increases, the returns of wage work will increase relative to self-employment. While Porter describes a decline of entrepreneurial activity in this stage, however, more recent research reveals a slow increase or stagnation of activity (Acs et al., 2008). Governments should improve the physical infrastructure and regulatory framework in this phase. As a result, the economy can be integrated into global value chains.

The final stage, driven stage, is the most difficult to reach. In order to reach the innovation-driven stage governments must actively foster innovation. They must encourage public and private investments in research and development, enhance the quality of tertiary education, open and deepen capital markets, and create a legal framework that supports high-growth innovative startups. This stage is characterized by a rise in entrepreneurial activity. Unlike the factor-driven stage, entrepreneurship is driven by opportunity and not by necessity. In this third stage, firms are more interactive and clusters between firms within the same industry are formed. This enables cooperation, intense competition, and flows of workers between firms (Porter et al., 2002).

Many Latin American economies are only in the efficiency-driven stage. The main problem of Latin American countries is the lack of opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. This is the result of policies focused on structural production efficiency as opposed to policies fostering innovation and entrepreneurship. Literature suggests two types of public policy. First, policy which reduces unemployment and necessity entrepreneurship. This in order to achieve the efficiency-driven stage, which involves economic and regulatory stability. Second, policy which promotes innovative entrepreneurship and aims to move towards the innovation-driven stage. In this way, new and better businesses are created, and not only isolated low-value ventures. In other words, governments should boost opportunity-driven entrepreneurship in Latin America (Acs & Amorós, 2008).

6

2.2. The entrepreneurial ecosystem

If a country wants to evolve to the innovation-driven stage of development, policymakers should foster innovative entrepreneurship. This not only by creating macro-economic stability, but also through a strong legal framework, open capital markets, high-quality education, and so on. So, if Latin American countries want to develop, they should consider the whole range factors and not focus on only one. Moreover, just implementing policies that were successful in another region is proven to be unsuccessful. Over the past years, many governments have attempted to create “the next Silicon Valley" by using this method but failed to do so . As a response to this phenomenon, the entrepreneurial ecosystem (EE) theory has emerged (Brown & Mason, 2014). According to this theory, the entrepreneurial ecosystem consists out of a complex set factors and actors, which can boost or constrain entrepreneurship, and interact with each other. Like Porters' theory, the EE theory underlines the importance of a holistic approach. One of these actors within the EE are business accelerators. They play a crucial role in the EE, especially during the development of the EE (Colombelli et al., 2019). This why it is important to first look at the context or the EE wherein business accelerators are active in Latin America. In this way, the strengths and dynamics of each EE are revealed (Isenberg, 2010; Spigel, 2017). More importantly, the role of business accelerators can be established within the EE. The role can be different in each EE because each EE will have a different set of factors, and dynamics that influence the role of business accelerators.

2.2.1. Defining entrepreneurial ecosystems

The best way to easily understand an EE is the biology metaphor. Biologists define ecosystems as a community of living organisms in conjunction with the nonliving components of their environment (things like air, water, and soil), interacting as a system (Wikipedia, sd-b). For example, if one of the components, for instance the soil, becomes more fertile more plants will grow. This will attract more bees. The presence of more bees will be beneficial for the birds, but will also stimulate the growth of plants. And maybe these birds will affect another component. So, the soil has an impact on the dynamics of the whole ecosystem, and not just on the plants. The biological metaphor represents the complex interactions and interdependencies that shape EEs. Moreover, it represents how the ecosystem constantly evolves and changes in a non-linear way (Isenberg, 2016; Brown & Mason, 2017).

As the EE theory is the most recent tool to analyze the existence of high-growth entrepreneurship within regions, there is no precise definition for an EE. Spigel (2017, p.49) defines EEs as “the union of localized

7 cultural outlooks, social networks, investment capital, universities, and active economic policies that create environments supportive of innovation-based ventures.” Brown and Mason (2014, p.5) define EEs as “a set of interconnected entrepreneurial actors, entrepreneurial organizations, institutions and entrepreneurial processes which formally and informally coalesce to connect, mediate and govern the performance within the local entrepreneurial environment.” These two definitions, as well as the available scientific literature, emphasize the interaction between the different component and the presence of characterizing components like investment capital, spin-off generators, universities and research organizations, a supportive entrepreneurial culture, a strong business infrastructure, support service/facilities, and public policies that incentivize venture creation (Neck, Meyer, Cohen, & Corbett, 2004; Cohen B. , 2006; Brown & Mason, 2014; Isenberg, 2016; Spigel, 2017)

Figure 2: Domains of the entrepreneurial ecosystem

The components can be divided into six generic domains: (1) Finance, (2) Policy, (3) Markets, (4) Human capital, (5) Supports, and (6) Culture. The components of each domain interact with each other in a complex manner. Moreover, each of these components can be favorable for entrepreneurship but cannot sustain it by itself. Nonetheless, not all of these components must be present, or fully developed, since every EE emerges under a different and unique set of conditions. Spigel (2017, p.56) states: "In ecosystems with dense relationships between attributes, this reproduction occurs by the interplay between a supportive entrepreneurial culture; networks of entrepreneurs, workers and investors; and effective public

8 organizations. In sparser ecosystems, one attribute drives the production of the other attributes, such as a large local market that creates multiple opportunities for entrepreneurs to exploit, grow, and profitably exit". Therefore, imposing generic causal paths, like many governments have done the past, is of limited value (Isenberg, 2010, 2016).

Although every EE has its unique set of conditions, one thing mostly many EEs have in common is spatial boundedness. Components of the EE are bound by geography but are not limited to a specific geographical boundary. EEs can develop at different geographical levels. These levels can range from a city to a regional focus and in rare cases a state/national focus. This is important because network formation and exchange of knowledge among different components are induced by close geographic proximity. Although the local context is important, the EE approach takes wider global linkages or global pipelines into account. Firms will try to engage with non-local partners to increase access to knowledge and assets that are not locally available. Especially in an early stage of development of EEs these ‘global pipelines’ play a crucial role (Bathelt, Malmberg, & Maskell, 2004)

2.2.2. Key actors and inter-relations within the EE

As mentioned in the previous section, the EE consists of different components, and these components interact with each other. In order to establish the role of business accelerators, we must take closer look at the key actors and relations within the EE. Moreover, for policymakers who want to foster entrepreneurship, it is useful to gain more insight into these actors and their roles. These key actors consist of entrepreneurial actors, entrepreneurial resource providers, entrepreneurial connectors, and entrepreneurial orientation (Brown & Mason, 2014; 2017). In the section that follows, we will discuss these key actors in this order.

9 Table 1: Key actors and inter-relationships within entrepreneurial ecosystems

Entrepreneurial actors

At the heart of the EE are the entrepreneurs (Isenberg, 2010; Brown & Mason, 2014). These can be entrepreneurs of startups but also well-established entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurs can also be active in or make use of incubators and accelerators. Interaction between these entrepreneurs is crucial. Not only can this interaction be a source of inspiration, this interaction can also directly help nurture or mentor the next generation of entrepreneurs. This process is called entrepreneurial recycling and drives the growth of EEs (Mason & Harrison, 2006). So, "entrepreneurship has a cumulative self-perpetuating effect on future levels of entrepreneurship" (Brown and Mason, 2017, p.18). Often, entrepreneurs retire once their company is sold. These entrepreneurs re-invest their capital gains and their knowledge. Others, however, will start new businesses - this type of entrepreneurs is also called serial entrepreneurs. Others will take on the role of a business angel, providing finance and advice through a position on the board of directors for new ventures. Other cashed-out entrepreneurs will become mentors or advisors of companies and accelerator programs, or engage in teaching activities. This process tends to be local because cashed-out entrepreneurs will identify investments through their personal and local networks. Moreover, if their investments are local they can use a more hands-on approach and minimize risk (Harrison, Mason, & Robson, 2010). Therefore,

10 past successes can realize critical injections back into the local ecosystem. So, success generates more success as this process is cumulative (Brown & Mason, 2017).

An important note is that the recycling process is driven by exits. In other words, the development of the public stock markets and a sufficiency in the available amounts of venture capital are crucial. Entrepreneurs need to grow their company to a point where they can generate enough wealth when they sell the company. To achieve this point, companies mostly need several financing rounds. When entrepreneurs can generate sufficient wealth, they can use their wealth and knowledge to re-invest into other ventures or to create new ventures. Underdevelopment of stock markets and insufficient amounts of venture capital can undermine the growth to this point. When businesses exit prematurely due to the inability to further raise capital, this will impact not only the wealth generated but also the knowledge of entrepreneurs. This scenario is common in weaker EEs (Brown & Mason, 2014).

Entrepreneurial resource providers

The presence of financial resources is crucial for the growth of startups (Cassar, 2004). Providers of finance include banks, venture capital firms, and business angels, but also alternatives such as crowdfunding and peer-to-peer lending (Bruton, Khavul, Siegel, & Wright, 2015). Not only the presence of sufficient seed capital is important but also the capital for later financing rounds. Ventures need a well-developed system that guides them through the different stages of financing. This is especially essential for young and technology-based ventures (North, Baldock, & Ullah, 2013). If local actors have connections with foreign funds that make larger and later-stage investments, the presence of venture capital firms is not essential since capital can be imported. This underlines the importance of well-functioning global pipelines, who provide access to markets and venture capital funds when they are not locally available.

Entrepreneurial connectors

For the growth of new ventures, not only access to finance is important but also access to networks The probability of survival and growth depends on network support (Brüderl & Preisendörfer, 1998). Informal and formal networks will help minimize insufficiencies, facilitate knowledge sharing, and develop the ecosystems' social capital (Ford & Sullivan, 2014). Innovative ecosystems consist of business clubs, startup networks, and network fora (Malecki, 2012).

11 Key individuals, known as dealmakers, foster, and orchestrate these networks. Dealmakers are the glue of the EE (Napier and Hansen, 2011, as cited in (Brown & Mason, 2017)). Dealmakers are “'individuals with valuable social capital, who have deep fiduciary ties within regional economies and act in the role of mediating relationship, making connections and facilitating new firm formation”(Feldman & Zoller, 2012, p.24).Sometimes these dealmakers are former entrepreneurs that mentor startups, invest in a variety of enterprises, and connect people in their network. Research suggests that dealmakers can have a positive influence on the recipient firms' employment and sales if they use their connections to 'make things happen' (Kemeny, Feldman, Ethridge, & Zoller, 2016).

Entrepreneurial culture

In addition to the presence of entrepreneurs, finance, and networks, the right entrepreneurial culture is crucial in EEs. Positive societal norms and attitudes towards entrepreneurship determine the success of an EE. in some societies, entrepreneurial intentions will be inhibited, because of the low social status of entrepreneurs, undervaluation of the contribution of entrepreneurs, and negative perception of failure (Isenberg, 2010). The latter is critical because failure can be a learning experience. In vibrant start-up communities when entrepreneurs fail, they are invited as advisors in other firms, venture capital firms, and business accelerators (Feld, 2012 as cited in Brown & Mason, 2014). These perceptions of entrepreneurship remain stable over time (Brown & Mason, 2014).

The key difference between entrepreneurship in the factor-driven stage and the innovation-driven stage is the driver for entrepreneurship. In the first stage of development, entrepreneurs start a business out of necessity. They are pushed into entrepreneurship because there are not sufficient jobs available. This is called necessity-driven entrepreneurship. In the last stage of development, entrepreneurs start a business to exploit a perceived opportunity. This is called opportunity-driven entrepreneurship. In this stage, there are sufficient jobs available, and the ecosystem has evolved in a way that there are high-value opportunities available. This type of entrepreneurship creates more value for the ecosystem than necessity-driven entrepreneurship. Therefore, developing economies can show higher levels of entrepreneurship than advanced economies. But the key difference between these economies is the quality and more importantly the ability to create economic value(Acs & Amorós, 2008; Brown & Mason, 2017; Bosma & Kelley, 2019). Nonetheless, a great number of opportunity-driven entrepreneurship, is still not a guarantee for a dynamic

12 and thriving ecosystem. In some ecosystems, there is a great number of opportunity-driven ventures but it is still difficult for these ventures to grow. Isenberg underlines that growth is the essence of entrepreneurship. In other words, to determine if EEs are thriving and dynamic, not the number of startups but their ability to grow matters (Isenberg, 2016).

13

2.3. Defining Business Accelerators

Business accelerators are actors within the EE. Moreover, they play a crucial rule in the development of EEs. To gain more insight into their role, we must not to only look at the dynamics of an EE but also at what defines business accelerators. In this section we will describe the design elements and themes of business accelerators that contribute to their role in the EE.

2.3.1. Definition

Generally speaking, business accelerators help nascent ventures define and build their first products, identify promising customer segments, and secure resources, such as capital and employees. Accelerators are “Limited-duration programs, lasting roughly three months, that help cohorts of ventures with the new venture process. They usually provide a small amount of seed capital, plus working space. They also offer a plethora of networking, educational, and mentorship opportunities, with both peer ventures and mentors, who might be successful entrepreneurs, program graduates, venture capitalists, angels investors, or even corporate executives. Finally, most programs end with a grand event, usually a "demo day" where ventures pitch to a large audience of qualified investors” (Cohen S. , 2013, p.19).

2.3.2. Context of emergence

In 2005 the first accelerator, Y Combinator, was launched in Boston. A year later, another accelerator was founded in Colorado. But it was only after the financial crisis of 2008, that the growth in U.S.-based accelerators took off, as did the number of startups, early-stage capital, and venture investment more broadly (Hathaway, 2016). The biggest factor driving this rise was the change of economics in startup life. Three major trends led to change in the entrepreneurial environment: :(1) cheaper technology, (2) cheaper customer acquisition, and (3) better forms of direct monetization. Moreover, changes in the investment market led to the rapid rise of accelerators. In the past decade, most of the profit of technology companies and other investors came from the acquisition market. In other words, multi-billion-dollar technology firms try to stay innovative by acquiring early-stage startups (Miller & Bound, 2011). Another possible explanation is that business accelerators have emerged as a response to the shortcomings of the previous generation of incubators. Each new generation adapts its design elements and theme to the current needs of entrepreneurs. The first generation of incubators only focused on providing physical and financial support. The next generation moved towards a focus on more intangible services, such as evaluating different market opportunities and access to networks. The newest generation has moved almost entirely away from

14 the first-generation services, towards more knowledge-intensive services (Bruneel, Ratinho, Clarysse, & Groen, 2012).

Chart 1: Number of new business accelerators per year

After the financial crisis of 2008, the number of business accelerators surged in the USA. During this period the first accelerators emerged in Latin America (Hathaway, 2016). In 2010 the Chilean government launched Start-Up Chile, which was considered the darling of the Latin American tech ecosystem. This was the “spark that ignited Latin America’s startup ecosystem,” and is often identified as the inspiration for government acceleration programs worldwide. In the past years, accelerator programs popped up all over Latin America to provide mentorship, investment network, and support for startups (Esperón, 2018). Recently, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico have developed themselves as real startup clusters (Tuna, 2019).

2.3.3. Design elements

In this section, we will describe those design elements that are relevant for our topic. More specifically, (1) program package, (2) Strategic focus, and (3) Alumni relations. These design elements will help business accelerators fulfill a specific role within the EE. Business accelerators must adjust their design to the needs and strengths of the EE.

15 Figure 3: Design elements and constructs

Program package

The program package consists of all services offered by the accelerator. The first element of the program package are well-elaborated and carefully planned mentoring services. The presence of these services constitutes the most critical distinction between accelerators and previous generation incubation models. The accelerators carefully pick out experienced entrepreneurs and match them to the startups, for example through speed dating or matchmaking events. These entrepreneurs act as mentors for startups and help them to define their business and connect them with their network. The package often includes training on a variety of topics such as finance, marketing, and management. Accelerators also offer counseling services in the form of 'weekly office hours' or evaluation moments to provide assistance when needed and to monitor the progress. They also offer a network of potential customers and investors. The accelerator organizes demo-days or investors' day, where startups can pitch their business plan to a large group of investors. This event usually takes place at the end of the limited-duration program. In addition to the investor network, accelerators offer a co-working space to encourage collaboration and peer-to-peer learning. Finally, the package includes investment opportunities offered by the accelerator itself. Some accelerators make small investments in their portfolio companies in exchange for equity (Cohen & Hochberg, 2014; Pauwels, Clarysse, Wright, & Van Hove, 2016).

16 Strategic focus

The second design element, strategic focus, deals with choices regarding industry, sector, and geographical focus. Business accelerators can focus on one specific industry, a sector, or a technology domain. Programs that take this approach are called specialists. Other programs have no vertical focus at all and are called generalists. The geographical focus concerns the choice of being locally or internationally active (Pauwels et al., 2016). Some business accelerators, like Startup Chile, focus on one specific region or country but allow "foreign" startups to participate on the condition that they set up shop in this region. So, having a local focus does not exclude international firms (Startup Chile, sd).

Alumni relations

The last element characterizing accelerator programs is the relationship with alumni. Most accelerators entertain close relations with graduates from their programs. Alumni are invited back to share their experiences with the new batch of startups and to alumni events. After several years, the accelerator develops a more elaborate network of alumni, that can be used as a possible source of mentors or investors. Pauwels et al. (2016, p.19) state that "Successful graduates are more likely to invest back into the community that supported them in the first place". This confirms the before mentioned self-perpetuating effect of entrepreneurship. Some programs even extend the provision of support services after the end of the program. When they invested in a startup, accelerators have an extra incentive to continue the support (Cohen & Hochberg, 2014; Pauwels et al., 2016).

2.3.4. Design themes

Business accelerators can be categorized into three generic design themes. The theme depends on the primary aim of the business accelerator or, in other words, on the role that the accelerator wants to fulfill. This aim is the result of the objectives of the accelerators’’ stakeholders, respectively corporations, investors, and government agencies within the EE. There are three types of design themes: (1) the ecosystem builder, (2) the deal-flow maker, and (3) the welfare stimulator. The implementation of design elements will be different for each of the themes because the design elements are adjusted to the aim of the accelerator.

17 Ecosystem builder

The accelerator programs, that fall under the theme of ecosystem builder, are mostly set up by large corporations, such as Microsoft and Google. These corporations aim to develop an ecosystem of customers and stakeholders around their company. These companies actively engage their own stakeholders in the accelerator program, for example, senior executives who screen potential program participants. Hence, only startups that enhance the development of the companies' ecosystem will be selected. These types of programs are often non-profit-oriented and mostly do not

Table 2:Design themes

18 offer a small amount of funding in exchange for an equity stake. This is an innovation strategy for many firms. Evidence shows that technology firms increase profitability through the acquisition market, so they are actively looking for startups (Miller & Bound, 2011).The added value of the program for startups is primarily the introduction to a network of potential customers. Hence, the network of the accelerators is almost exclusively oriented towards potential customers (Pauwels et al., 2016).

Deal-flow maker

The deal-flow maker accelerator has the objective to bridge the gap between early-stage ventures and investors. The programs are typically funded by investors, such as business angels and venture capital funds and aim to identify profitable investment opportunities for these investors. The accelerator makes an initial investment in exchange for a stake in equity. They also tend to favor startups that show more growth potential and allow for more follow-on capital investments. Active business angels are used as mentors, and for follow-up investments. These types of programs tend to favor startups in later stages of development, which have already obtained some seed-finance. Moreover, these programs often specialize in a specific industry. In this way, the accelerator team can cultivate the appropriate knowledge and expertise to identify and guide lucrative startups (Pauwels et al., 2016).

Welfare stimulator

The accelerator known as the welfare stimulator has as a purpose to stimulate entrepreneurial activity and economic growth within a specific region or technological domain. Often, their principal stakeholder is a government agency. These types of accelerators want to attract startups that fit within the vision of welfare creation. They also tend to select early-stage startups. For this reason, they usually offer a very elaborate training program, more than the other two types of accelerators. The mentors of welfare stimulators are more involved and use a more hands-on approach. The business model for most welfare stimulators is rather ambiguous (Pauwels et al., 2016).

19

2.4. The role of the business accelerator within the entrepreneurial ecosystem

In the entrepreneurial ecosystem there is a multitude of players whom all interact with each other, but how do they relate to each other? And, more importantly, how do they relate to business accelerators? Literature on the governance of EE emphasizes the role of the "anchor tenant" within the network. The anchor tenant is defined as "the central player that actively spurs economic growth, technological change, and innovation in the area, and around which groups of different organizations begin to gather" (Colombelli et al., 2019, p. 508). This role can be fulfilled by local universities, public research organizations, or by one or more key firms. (Colombelli et al., 2019). These organizations can either act directly or indirectly through an accelerator. If they act indirectly, the organizations can choose the design theme appropriate for their objective.

Figure 4:Conceptual framework Anchor tenant theory

Source: Colombelli, Paolucci, & Ughetto (2019)

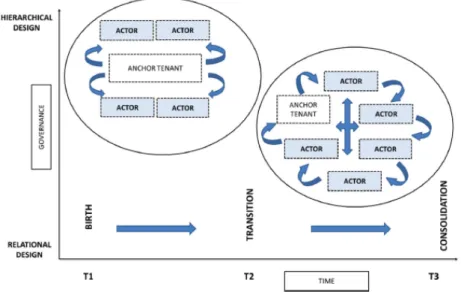

The position of the anchor tenant in the ecosystem changes as the ecosystem develops. Colombelli’s theoretical framework suggests three phases of the EE: (1) the birth phase, (2) the transition phase, and (3) the consolidation phase. These three phases can be linked to the transition from the efficiency-driven stage to the innovation-driven stage of development of the economy. During the birth phase, which refers to the emergence of the EE, the anchor tenant is seen as a change agent or catalyst. This agent fosters and orchestrates the network, and their role is sustained by the trust that different multiple organizations place in them. Research theorizes that the anchor tenant initiates the emergence and governs the

20 entrepreneurial ecosystem. Other players, who support entrepreneurship, will gather around the anchor tenant. These players are governmental organizations, with the task to foster entrepreneurship for example through tax benefits and investment in public funds. These other players can also be the before mentioned entrepreneurial actors, connectors, and resource providers. Together, they form the “entrepreneurial support network”(Kemeny et al., 2016). This formation of institutions around the central player is crucial for the survival of the EE as it bridges the gap between the production and commercialization of new knowledge. "Once the ecosystem has been created, its adaptive capacity to the local conditions progressively increases, and its governance evolves towards a more horizontal and relational design, where multiple actors interact without a structural function being exerted by a central player (Colombelli et al., 2019, p. 509)". The linkages between the actors become stronger as the EE transitions to the consolidation phase. In other words, the position of the anchor tenant becomes less central as the EE evolves towards its final stage.

Business accelerators fulfill this central role within the network, particularly in Latin America where EEs have not achieved the consolidation phase or innovation-driven phase. Business accelerators act as an intermediary between startups, government, investors, customers, and educational institutions. Mason and Brown (2017) refer to their role as that of “dealmakers” who connect different actors and are the glue of the EE. The different design elements of business accelerators enable them to play this role. A case study Figure 5: Intermediary role of the business accelerator within the EE

21 of Turin’s entrepreneurial ecosystem identified IP3, an incubator created by Italian government institutions, as the anchor tenant. According to the study, IP3 acted as the main driver of the emergence and expansion of the EE (Colombelli et al., 2019).

Startups, Business accelerators, and Investors

Research reveals that startups are not able to attract investment consistent with their needs without the help of business accelerators, even if they themselves have sufficient skills and experience. This is because investors in emerging market settings believe it is more difficult to find deals of good quality. The main challenge in these markets is not the quality of entrepreneurs, but the perceptions about their ability and capacity (Roberts & Kempner, 2017).

Business accelerators help startups navigate their way through the different stages of funding, known as the funding escalator, by educating them on the different types of investment and legalities and putting them in touch with the right investors. Research reveals that access to a network of potential investors and the opportunity to meet them face-to-face, is challenging for first-time entrepreneurs and is identified as a major benefit. Additionally, startups are selected as a 'promising startup' by a group of professionals and this perceived by investors as an indicator of quality (Miller & Bound, 2011).

Evidence shows that business accelerators have a positive impact on finance. Regions in which accelerators are active exhibit more seed and early-stage financing activity and this activity is not restricted to accelerated startups but spills over to non-accelerated ventures as well (Fedher & Hochberg, 2014).

Startups, Business accelerators, and Government institutions

Policymakers aim to enhance the entrepreneurial activity in their regions. Mason and Brown (2014, 2017) argue that the government should focus on the creation of quality startups with growth potential. They suggest two approaches: (1) provide intensive support and mentoring to entrepreneurs during all stages of the startup (pre-startup, startup, post-startup) (Roper & Hart, 2013) and (2) support nascent ventures through incubation programs, which provide a workspace, access to finance and a network of investors and other ventures (Miller & Bound, 2011). As mentioned before, government intervention works better indirectly. Business accelerators are a way for governments to provide support to startups indirectly

22 through business accelerators. Either they can invest in one of the high-quality startups selected or they can set up an accelerator program. Using an accelerator as an intermediary combines the two suggested approaches.

By funding a few accelerators or investing in some startups, the process of entrepreneurial recycling can be incited. This means that the current level of entrepreneurship will generate higher levels of entrepreneurship. In other words, success generates more success.

Startups, Business accelerators, and other Entrepreneurs

One might think that the most valuable and appealing part of participating in an accelerator program would be the funding, yet it is rarely rated as the most important feature by entrepreneurs who participated in an accelerator program. Accelerators give startups access to a network of people in the industry and thus to high-quality feedback on their product and company. This feature is seen by many entrepreneurs as the most difficult to come by without the help of an accelerator (Miller & Bound, 2011).

Business accelerators generate local buzz because by their many networking event grants entrepreneurs, alumni of the program, and other stakeholders the opportunity to meet face-to-face and exchange valuable information. Accelerator programs can induce entrepreneurial recycling for two reasons. First, because they help startups with the financing process. This increases the chances of entrepreneurs selling or exiting the company with sufficient wealth to re-invest. Research reveals that successful graduates are more likely to invest in the community that supported them (Pauwels et al, 2016) and that this process tends to be local (Mason and Brown, 2014, 2017). The second reason is that alumni are role models for starting entrepreneurs. Through mentoring services, alumni can share their experiences and other valuable knowledge with applicants.

23

3. Methodology

3.1. Choice of countries

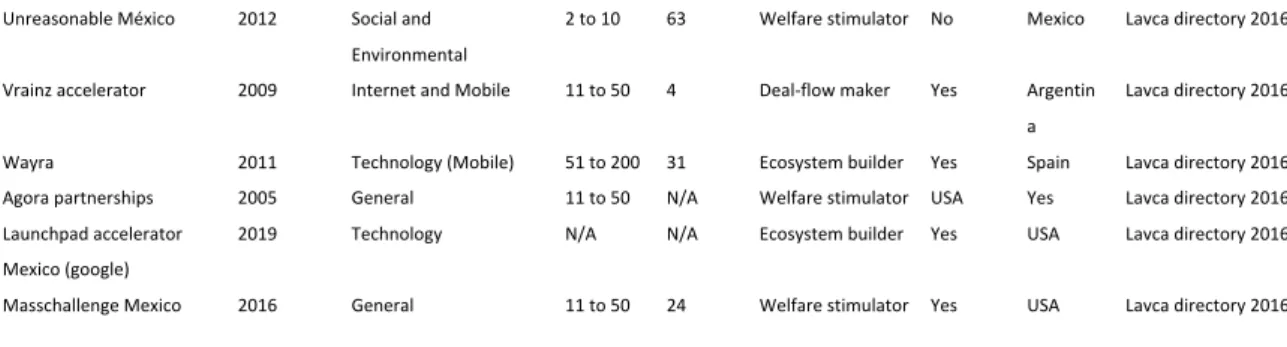

This dissertation will take the entrepreneurial ecosystems of three Latin American countries as case studies. The research question I aim to answer is "In what type of Latin American entrepreneurial ecosystems are business accelerators active?" Thus, it will be useful to analyze ecosystems in which business accelerators are active. To determine the number of active business accelerators, data was collected from two databases: the LAVCA directory 2016 and Contxto Database. The first directory belongs to the Association for Private Capital Investment in Latin America, LAVCA. This is a non-profit organization dedicated to supporting the growth of private capital in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAVCA, sd). The latter is a database from a website specialized in tech, startup, and venture capital news (CONTXTO, sd). By comparing these two databases, I was able to make a list of potential business accelerators per country. The full database can be found in Attachment 1.1: Database business accelerators.

After compelling the list, I checked if these accelerators complied with the definition given in the literature review and if they were still active as business accelerators. I also determined their sector, team size, portfolio size, design theme, and activity in other Latin American countries. By looking at the websites of the accelerator’s website, LinkedIn account, and other social media activity (e.g. Facebook and Twitter) I determined all these categories. However, discerning if a business accelerator complied with the definition was difficult because some programs or ventures call themselves a business accelerator, while in reality they are more an incubator, an education program for entrepreneurs or they do not have all the design elements mentioned in the literature review. An additional challenge was determining the design theme because, as mentioned before hybrid themes are possible. So, I chose to take the goal of the program as the determining factor. Moreover, it is important to note that the number found is an approximate the reality because there is a possibility that the databases are incomplete. Nonetheless, my findings are consistent with data on the startup hubs in Latin America (Tuna, 2019; BizLatinHub, 2019).

24 Chart 2: Number of active business accelerators per country in Latin America

3.2. Analysis of the entrepreneurial ecosystem

In what follows, I will analyze the entrepreneurial ecosystems of three Latin American countries: Brazil, Mexico, and Chile. These three countries have developing economies and have the most entrepreneurial activity of Latin America. In this respect, this dissertation will be a case study of the three similar countries or ecosystems, in terms of size of the economy and development, and in which the most accelerators are active. The aim of this case study will be a comprehensive description of the entrepreneurial ecosystem, in order to understand the complex dynamics of each ecosystem.

Figure 6: OECD Framework

25 In the previous chapter, I described the entrepreneurial ecosystem theory in detail. This theory focuses on six domains: policy, finance, culture, supports, human capital, and markets. The OECD, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, followed this line of thought but focused on the point of view of policymakers. The EIP, Entrepreneurship Indicators Program of the OECD, developed a framework that identifies three flows: (1) determinants, (2) entrepreneurial performance, and (3) impact. These three flows are linked to one another and are important for the assessment and formulation of policy. These determinants are categorized into 6 pillars, that are largely consistent with the 6 domains of the entrepreneurial ecosystem theory. The determinants all measure a different aspects of entrepreneurship (Arruda, Nogueira, & Costa, 2013). Moreover, this framework considers a whole range of quantitative indicators for these determinants. However, this list should not be considered as exhaustive since it depends on the availability of data(OECD, 2011, 2017a). So, this framework will be used as a guide for the analysis of the entrepreneurial ecosystem, in accordance with the study of the Arruda et al. (2013) on the Brazilian entrepreneurial ecosystem. Similar to this study, the OECD quantitative indicators will be gathered and complemented with qualitative data on the underlying drivers, such as policy and surveys. Moreover, like in the study by Arruda et al., the OECD framework will be adapted, as not all data is available. New indicators, based on the ones of the OECD framework and the particular context of Latin American countries, were added to the adapted OECD framework. The adapted OECD framework with the new indicators can be found in Annex 10.2. For example, Mexico and Brazil are two countries that experience high levels of corruption and violence, which directly impacts entrepreneurial activity (Ríos, 2018). For this reason, the rule of law index was included. Another example is the quality of universities because a high quality of education is necessary to diversify the economy (Boulton & Lucas, 2008). Moreover, the indicator if the bankruptcy regulation is debtor or creditor friendly was added, because regulation that does not excessively penalize business failure can generate more innovative entrepreneurship and attract more talented individuals. Too little safeguards for creditors reduce the supply of credit (McGowan, Andrews, & Millot, 2017) Also, indicators measuring the economic development of the country were added, for example, necessity-driven entrepreneurship and main goods of export and import. In this way, the development of the ecosystem can be determined.

In this way, this analysis follows Kathleen Eisenhardt’s research method for case studies. Eisenhardt argues that case studies include quantitative and qualitative data that can be collected from multiple sources. This method of gathering data from multiple sources in case studies is appropriate for complex processes, like

26 the processes in the ecosystem and hard to measure constructs, like entrepreneurship (Gehman, et al., 2018). To gain more insight into the determinants of the entrepreneurial ecosystem, I will use this method and gather data from different sources, such as databases, reports, surveys, and news articles. Most of these sources are from the OECD because the framework includes many determinants that are studied by the OECD. Chile and Mexico are both members of the OECD, while Brazil is not. This is why, some determinants for Brazil will be missing (for example, product market regulation).

27

4. Country profiles

In this chapter, the general context of the environment wherein Latin American business accelerators are active in will be analyzed. In this way, insight in the underlying political, economic, and social drivers of the entrepreneurial ecosystem can be attained. Moreover, the type accelerators of the composed database will be analyzed by the design theme, geographical and industrial focus, team size and year of establishment. This will give an indication of the role accelerators play in the environment. The three countries in Latin America with the most active business accelerators, Brazil, Mexico, and Chile, will be analyzed.

4.1. Brazil

Table 3: Key figures BrazilBrazil has the largest Latin American economy in terms of GDP, Gross Domestic Product (current USD, United States Dollar). The country counts for more than half of Latin American startups (LAVCA, 2019c) and has the most, 29, active business accelerators. Brazil experienced between 2003 and 2014 significant growth in terms of economic growth, as well as social progress. In these 10 years, more than 29 million were lifted out of poverty, inequality declined and the average growth of GDP was approximate 3,5%. However, the growth rate has slowed down between 2011 and 2014, and in 2015 and 2016 the country experienced an economic crisis. This crisis was induced by the falling commodity prices, the inability of the government to reform the fiscal system, and money laundering investigation ‘operation car wash’. The latter is known as one of the largest corruption scandals the world has seen. It caused the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff in 2016 and led to a power shift from the Workers Party to the far-right party of Jair Bolsonaro at the end of 2018 (Londoño & Darlington, 2018). These factors undermined consumer and investor confidence. As of 2017, Brazil experienced modest growth, but this already stagnated because of a weak labor market, uncertainty amongst investors due to the elections, and a national strike of truckers (World Bank, 2019e). After the victory of Bolsonaro the stock markets experienced a boost. This because

28 the new president, is a strong free-market proponent and wants to reform Brazil with a pro-business agenda, which might be good news for many businesses and entrepreneurs in Brazil (Rodrigues, 2019). Even though Brazil has experienced a recession and a lot of political turbulence in the last decade, startup activity has boomed. At this point, Brazil has become the startup hub of Latin America. As mentioned before, the country counts the most startups and active business accelerators in Latin America. In 2018 the number of Brazilian venture capital deals accounted for more than half of all venture capital deals in LATAM (LAVCA, 2019b). Almost 50 percent of large companies’ investments are invested in Brazil, because of its productivity and improved business environment. The federal government actively supports entrepreneurial activity through a federal program developed by the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MCTI) called ‘Startup Brazil’. The goal of this program is to support innovative technology-oriented startups and connect them with business accelerators (BizLatinHub, 2019; Crunchbase, sd).

According to my data, Brazil counts 29 active business accelerators, where more than half are deal-flow makers and almost all are focused on technology. Approximate 60 percent of the business accelerators are only active Brazil. Important to note is that this does not exclude foreign startups from entering the program. Four out of five business accelerators have a team smaller than 50 persons. All, except two, were founded before 2014, the start of the recession in Brazil. The two exceptions were founded in 2018 when the economy was recovering. 21%

62% 17%

Ecosystem builder Deal-flow maker Welfare stimulator

29

4.2. Mexico

Table 4: Key figures MexicoMexico is the 2nd largest economy after Brazil and has the most competitive economy after Chile in Latin America (World Bank, 2018b; Schwab, 2019). Mexico is the 12th largest exporter in the world because the country shifted its production away from raw materials to manufactured products that are well integrated into the global value chains. Approximately 80% of these manufactured goods are exported to foreign markets, and most of them go to neighboring country USA. It is important to note, that the share of value-added remains below the share of peers. Mexico has developed strong macroeconomic institutions, that makes the economy more resilient for headwinds. This macroeconomic stability encourages investment and trade in Mexico and made the Mexican peso the most highly traded emerging market currency. The World Bank identifies the numerous trade agreements, advantageous geographic location, and growing domestic market as key strengths. Despite the many strengths, Mexico still struggles with high rates of perceived corruption, increasing violence of drug cartels, and rising inequality (OECD, 2018a; Amadeo, 2019; World Bank, 2019e).

Mexico accounts for almost a fifth of all startups in Latin America. The country has evolved into a real startup hub and leads in the Fintech sector, the largest startup sector. Mexico has a large population, who just begun using mobile commerce and opening bank accounts for the first. This creates a great business potential for startups using financial innovation (BizLatinHub, 2019; LAVCA, 2019a). Mexico accounted for 20% of all Latin American venture capital investments in technology in 2018. The value of VC, Venture Capital, deals has risen 41%

50% 9%

Deal-flow maker Welfare stimulator Ecosystem builder

Chart 4: Design themes Mexico

30 by 120% compared to 2017 (LAVCA, 2019b). Mexico counts 22 active business accelerators. Unlike Brazil, halve of the accelerators have a welfare stimulator design theme. Nevertheless, the deal-flow maker theme is also present. Just like brazil, the ecosystem builder theme has the smallest share. The number of new business accelerators founded between 2009 and 2016 was approximately 2 per year and was very stable. This number fell Mexico, after 2016, to zero in the following years (see Chart 6: Number of business accelerators founded per year). The size of most accelerator teams is between 11 and 50 employees. Furthermore, 60% of business accelerators are only active in Mexico. These last two observations are similar to the Brazilian climate of accelerators.

4.3. Chile

Table 5: Key figures ChileAlthough, Chile is the fifth biggest economy in terms of GDP, it is the most competitive economy in Latin America (World Bank, sd-a; Schwab, 2019).Chile is just like Mexico part of the OECD. According to the World Bank the country is the best environment for business in the region (Doing Business, sd). Chile has a stable macro-economic environment, due to low inflation, low public debt, open markets, and strong financial markets. Unlike Brazil and Mexico, corruption is not an issue. It has one of the lowest perceived corruption levels of the region (LAVCA, 2017). Chile is also one of the fastest-growing economies in recent decades. Growth has slowed down since the social unrest. Between 2000 and 2017 Chile sustainably reduced poverty from 30% to 3,7%. The quality of life for many Chileans has significantly improved, but the income inequality remains high and persistent. In 2006, 2007 and 2015 multiple student protest took place against the inequality of the education system. Since the end of 2019, uprisings begun against the privatization of the education, health care, and pension system and opportunities on the labor market (Junes, 2019). So, inclusive growth is a major challenge for the Chilean government. In addition to the social unrest, the end of the commodity cycle and slower global trade have undermined growth and business confidence (OECD, 2018b; World Bank, 2020).

31 Chile accounts for 6% of all Latin American startups (LAVCA, 2019a). Although Chile counts only 10 business accelerators, it is home to a world-leading business accelerator, StartUp Chile. The Chilean government, through its development agency CORFO (Corporación de Fomento de la Producción de Chile), launched the first business accelerator in Latin America in 2010, during the global financial crisis. The aim was to change the entrepreneurial culture and to create an international startup hub. Later, in 2016 this objective altered to enhance socio-economic growth through startup activity. StartUp Chile supported more than 1600 startups from 85 countries and established Chile as a world-leading startup nation. It inspired other governments from over 50 countries, to set up similar business accelerators, including Brazil and Colombia (Moed, 2018; Aoe, 2019). Although, StartUp Chile is by far the largest accelerator in Chile, the country count 9 other accelerators. Based on my findings, all three design themes are equally prevalent. Half of the accelerators are only active in Chile, and the other halve are active in several countries. All, except one, have team smaller than 50 people. This last two findings are similar to the business accelerators in Mexico and Chile.

30%

40% 30%

Deal-flow maker Welfare stimulator Ecosystem builder

32

5. Analysis of determinants of the entrepreneurial ecosystem

In this chapter, I will analyze the determinants of the entrepreneurial ecosystem of Brazil, Mexico, and Chile by utilizing the adapted OECD framework. This analysis will provide insights into the different aspects that make every entrepreneurial ecosystem unique. The aim is to find key factors in each ecosystem that enable or inhibit entrepreneurial activity. Based on the entrepreneurial ecosystem theory described in the section Literature Review, we expect there to be similarities between the three countries and, more importantly, that each country will have its unique set of determinants that induces (or inhibits) entrepreneurial activity in the ecosystem. Departing from these findings will allow us to establish the role of business accelerators within the EE in the next chapter. Moreover, I expect to find that the three developing countries are in the efficiency-driven stage of development and show signs of policy conducive to innovative entrepreneurship.

5.1. Brazil

5.1.1. Regulatory framework

Administrative burden

In Brazil, the process of starting a business consists out of 11 steps with a total time of 13,5 days and with an average cost of 3,6% of income per capita or 220 USD.12 The number of steps entrepreneurs must undertake is still a lot, even for the region, and the total process time is long. The total cost is inexpensive for a Latin American country. However, the procedure, length, and cost differ in every state. Moreover, there is no minimum capital requirement to set up a Sociedade Limitada or a limited liability company. Brazil already improved the efficiency of the whole process greatly in 2018 by introducing a new online system for company registration, licensing, and employment notifications (World Bank, 2019a). Apart from the lengthy procedure, it is relatively easy to set up a business in Brazil.

Bankruptcy regulations

The time required to recover a debt is 4 years, the recovery rate is only 18,2%, and the cost required to recover debt is 12%. Brazilian insolvency procedures take longer than those of peers, while creditors

1 1,125.43BRL = 219,34 USD (XE, sd)

33 recover less. Only the cost of the procedure is less than the regional average. Moreover, the insolvency framework is strong, even stronger than in many OECD high income countries (World Bank, 2018a). Nevertheless, the last major bankruptcy reform was in 2005 (World Bank, 2019a). The reform included positive elements such as fast liquidation and protected reorganization. Additionally, a judicial reorganization and an alternative out-of-court proceeding were implemented. The problem with the current bankruptcy law is the limited number of safeguards for secured creditors. Creditors are often prevented from enforcing pre-petition guarantees or redeeming collateral. The law places labor and tax claims in a higher class above the claims of secured creditors. These labor and tax claims are excessive and generally leave few assets to repay creditors. Therefore, the recovery rate is so low. Moreover, this regulation causes Brazilian banks to charge some of the highest lending rates globally (The International Scene, 2004). As a consequence, entrepreneurs will have more difficulty obtaining bank loans, which induces credit problems in the EE.

Labor market regulations

Brazil ranks 105th out of 141 countries on labor-market efficiency according to the World Economic Forum (WEF) (Schwab, 2019). In 2017 the labor law was reformed. The reform introduced for example more flexible working hours and reduced restrictions on part-time work, and got rid of the mandatory payments to unions, regardless if an employee is a member. The reform benefits especially employers and small firms and made the labor law less rigid. Nevertheless, mandatory charges and taxes still cause high labor costs (Deloitte, sd-b). Also, Brazil scores poorly on hiring and firing practices in the World Competitiveness Index (Schwab, 2019). Despite the reforms, labor regulation remains a major concern for many startups (LAVCA, 2019a). So, regulations may prevent entrepreneurs from hiring employees. In other words, regulation inhibits entrepreneurs from expanding their businesses and generating prosperity in the Brazilian ecosystem.

Court and legal framework

In Brazil, every state arranges its own juridical system, in accordance with the states' constitution (Deloitte, sd-a). As such, the proceedings may differ between each of the 26 states. In São Paulo, Brazil's financial and cultural hub, it takes on average 731 days to enforce a contract. This average is better than the Latin American average, yet still, 140 days longer than in most OECD high-income countries. The legal costs,