Acta Derm Venereol 92

European Guideline on Chronic Pruritus

In cooperation with the European Dermatology Forum (EDF) and the European Academy of

Dermatology and Venereology (EADV)

Elke WEISShAAr1, Jacek C. SzEpIEToWSkI2, Ulf DArSoW3, Laurent MISEry4, Joanna WALLENgrEN5, Thomas METTANg6, Uwe gIELEr7, Torello LoTTI8, Julien LAMbErT9, peter MAISEL10, Markus STrEIT11, Malcolm W. grEAVES12, Andrew CArMI-ChAEL13, Erwin TSChAChLEr14, Johannes rINg3 and Sonja STäNDEr15

1Department of Clinical Social Medicine, Environmental and Occupational Dermatology, Ruprecht-Karls-University Heidelberg, Germany, 2Department

of Dermatology, Venereology and Allergology, Wroclaw Medical University, Poland, 3Department of Dermatology and Allergy Biederstein, Technical

Uni-versity München and ZAUM - Center for Allergy and Environment, Munich, Germany, 4Department of Dermatology, University Hospital Brest, France, 5Department of Dermatology, Lund University, Sweden, 6German Clinic for Diagnostics, Nephrology, Wiesbaden, 7Department of Psychosomatic

Dermato-logy, Clinic for Psychosomatic Medicine, University of Giessen, Giessen, Germany, 8Department of Dermatology, University of Florence, Italy, 9

Depart-ment of Dermatology, University of Antwerpen, Belgium, 10Department of General Medicine, University Hospital Muenster, Germany, 11Department of

Dermatology, Kantonsspital Aarau, Switzerland, 12Department of Dermatology, St. Thomas Hospital Lambeth, London, 13Department of Dermatology,

James Cook University Hospital Middlesbrough, UK, 14Department of Dermatology, Medical University Vienna, Austria and 15Department of

Dermato-logy, Competence Center for Pruritus, University Hospital Muenster, Germany

Abbreviations and Explanations

AD: Atopic dermatitis

AEp: Atopic eruption of pregnancy Cgrp: Calcitonin gene-related peptide CkD: Chronic kidney disease

Cp: Chronic pruritus (longer than 6 weeks) DIF: Direct immunofluorescence

ICp: Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy IFSI: International Forum on the Study of Itch IIF: Indirect immunofluorescence

IL: Interleukin

Itch: Synonymous with pruritus

NSAID: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs pAr: proteinase-activated receptor

Corresponding addresses: Sonja Ständer M.D., Competence Center Chronic Pruritus, Department of Dermatology, University Hospital Münster, Von-Esmarch-Str. 58, DE-48149 Münster, Germany. E-mail: sonja.staender@uni-muenster.de

Elke Weisshaar M.D., Department of Clinical Social Medicine, Occupational and Environmental Dermatology, Ruprecht-Karls-University Heidelberg, Thibautstr. 3, DE-69115 Heidelberg, Germany. E-mail: elke.weisshaar@med.uni-heidelberg.de

pbC: primary biliary cirrhosis

pEp: polymorphic eruption of pregnancy pg: pemphigoid gestationis

pN: prurigo nodularis

pruritus: A skin sensation which elicits the urge to scratch pUo: pruritus of unknown origin

pTh: parathyroid hormone pV: polycythaemia vera

rCT: randomised controlled trials

SSrI: Selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors Trp: Transient receptor potential

UV: Ultraviolet

1. The challenge of writing this guideline 3

2. Definitions and clinical classification 3

3. Epidemiology of chronic pruritus 3

4. The clinical picture of chronic pruritus 4

4.1 pruritus in diseased conditions 4

4.1.1 Pruritus in inflamed skin and non-inflamed skin 4

4.1.2 pruritus in kidney disease 4

4.1.3 pruritus in hepatic diseases 4

4.1.4 pruritus in metabolic and endocrine diseases 4

4.1.5 pruritus in malignancies 4

4.1.6 pruritus in infectious diseases 4

4.1.7 pruritus in neurological diseases 5

4.1.8 Drug induced chronic pruritus 5

4.2 Specific patient populations 5

4.2.1 Chronic pruritus in the elderly 5

4.2.2 Chronic pruritus in pregnancy 6

4.2.3 Chronic pruritus in children 6

5. Diagnostic management 6

5.1 patient’s history, examination and clinical characteristics of pruritus 6

5.2 Diagnostic algorithm and Diagnostics 7

6. Therapy 7

6.1 general principles 7

6.2 Causative therapy and etiology specific treatment 9

6.3. Symptomatic therapy: topical 10

6.3.1 Local anaesthetics 10

6.3.2 glucocorticosteroids 11

6.3.3. Capsaicin 11

6.3.4. Cannabinoid receptor agonists 12

6.3.5 Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus 12

6.3.6 Acetylsalicylic Acid 12

6.3.8 zinc, Menthol and Camphor 12

6.3.9 Mast cell inhibitors 12

6.4 Systemic therapy 13

6.4.1 Antihistamines 13

6.4.2 Mast cell inhibitors 13

6.4.3 glucocorticosteroids 13

6.4.4 opioid receptor agonists and antagonists 14

6.4.5 gabapentin and pregabalin 14

6.4.6 Antidepressants 14

6.4.7 Serotonin receptor antagonists 14

6.4.8 Thalidomide 15

6.4.9 Leukotriene receptor antagonist, TNF antagonists 15

6.4.10 Cyclosporin A 15

6.4.11 Aprepitant 15

6.5 UV phototherapy 15

6.6 psychosomatic therapy (relaxation techniques and psychotherapy) 16 7. Key summary of discussion concerning country-specific procedures 16

1. ThE ChALLENgE oF WrITINg ThIS gUIDELINE Chronic pruritus (Cp) is a frequent symptom in the general population and in many skin and systemic diseases (1). Its frequency demonstrates a high burden and an impaired quality of life. This guideline addres-ses a symptom and not a disease. As a consequence of the diversity of possible underlying diseases, no single therapy concept can be recommended. Each form of pruritus has to be considered individually. There is still a significant lack of randomised controlled trials (RCT), that can be explained by the diversity and complexity of this symptom, multifactorial aetiologies of pruri-tus and the lack of well-defined outcome measures. To complicate matters, rCT exist for some types of pruritus, but with conflicting results. However, new therapies for improved medical care have been sug-gested. In addition, many expert recommendations are provided. The health care system in many countries and their social economic situation with constantly reducing financial resources increases the need for guidelines. These recommendations are based on a con-sensus of participating countries, while also allowing for country-specific treatment modalities, and health care structures. Furthermore, it should be appreciated that some topical and systemic therapies can only be prescribed “off-label” and require informed consent. If such “off-label” therapies cannot be initiated in the physician’s office, cooperation with a specialised centre for pruritus might be helpful.

This guideline addresses all medical disciplines that work with patients suffering from Cp. This includes also entities defined by chronic scratch lesions such as prurigo nodularis and lichen simplex. The guidelines are not only focussed on dermatology.

2. DEFINITIoNS AND CLINICAL CLASSIFICATIoN The definitions presented in this guideline are based on a consensus among the European participants; however, some of them have provoked controversy. Most of the contributors accept pruritus and itch to be synonymous. A practical distinction is that between acute pruritus and chronic forms (lasting six weeks or longer). pruritus/ itch is a sensation that provokes the desire to scratch. According to the International Forum on the Study of Itch (IFSI), CP is defined as pruritus lasting 6 weeks or longer (2). Following the IFSI, the term “pruritus sine materia” will not be used in this guideline (3). In patients with no identified underlying disease, the term “pruritus of unknown origin” or “pruritus of un-determined origin” (pUo) is used. The term “pruritus of unknown aetiology” should be avoided as in most clinically well-defined forms of pruritus the mecha-nism is unknown (e.g. chronic kidney disease (CkD) associated pruritus). This guideline addresses patients

presenting with Cp of different, including unknown, origin. If the underlying cause is detected, disease-specific guidelines should be consulted (e.g. atopic dermatitis (AD), cholestatic pruritus) (4–6).

According to the IFSI classification, the aetiology of CP is classified as I “dermatological”, II “systemic”, III “neurological”, IV “somatoform”, V “mixed origin” and VI “others” (2). The IFSI classification comprises a clinical distinction of patients with pruritus on primarily diseased/inflamed skin, pruritus on normal skin and pru-ritus with chronic secondary scratch lesions.

Somatoform pruritus is defined as pruritus where psy-chiatric and psychosomatic factors play a critical role in the initiation, intensity, aggravation or persistence of the pruritus. It is best diagnosed using positive and negative diagnostic criteria (5).

3. EpIDEMIoLogy oF ChroNIC prUrITUS Data on the prevalence of Cp is very limited. The prevalence of Cp seems to increase with age (7), but epidemiological studies are missing. It is estimated that about 60% of the elderly (≥ 65 years of age) suf-fer from mild to severe occasional pruritus each week (8), entitled senile pruritus or pruritus in the elderly. A population-based cross-sectional study in 19,000 adults showed that about 8–9% of the general popula-tion experienced acute pruritus, which was a dominant symptom across all age groups (9). Moreover, it was re-vealed that pruritus is strongly associated with chronic pain (10). recent surveys indicate a point-prevalence of Cp to be around 13.5% in the general adult population (11) and 16.8% in employees seeking detection cancer screenings (12). The 12-month prevalence of Cp was 16.4% and its lifetime prevalence 22.0% in a german population-based cross-sectional study (11). All these data suggest a higher prevalence of Cp in the general population than previously reported (11).

Cp may be due to both dermatological and systemic diseases. however, the origin of pruritus is unknown in 8–15% of affected patients (1). The frequency of pruritus among patients with a primary rash depends on the skin disease. For example, pruritus is present in all patients with AD and urticaria (13), and about 80% of psoriatic patients (14, 15). Systemic diseases such as primary biliary cirrhosis (pbC) and CkD are asso-ciated with Cp in 80–100% and 40–70%, respectively (16). In patients with hodgkin’s lymphoma, pruritus is a frequent symptom, occurring in more than 30% of patients with hodgkin’s disease.

only few studies have addressed the frequency of pruritus in primary care. According to the Australian bEACh program, a continuous national study of ge-neral practice activity, pruritus was the presenting complaint for 0.6% of consultations, excluding perianal, periorbital or auricular pruritus (17). In britain, the

fourth national study of morbidity statistics from general practice (18) was conducted in 1991/1992 with 502,493 patients (1% sample of England and Wales), resulting in 468,042 person-years-at-risk. pruritus and related conditions was present in 1.04% of consultations (male 0.73%, female 1.33%). on Crete, where patients with cutaneous disorders mostly present to hospitals rather than to primary care, pUo was diagnosed in 6.3% of 3,715 patients in 2003 (19).

4. ThE CLINICAL pICTUrE oF ChroNIC prUrITUS

4.1. Pruritus in diseased conditions

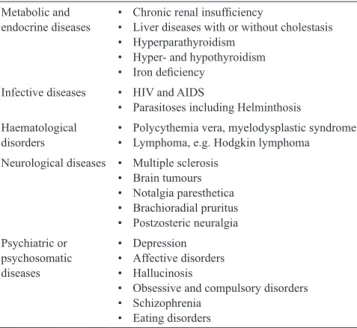

4.1.1. Pruritus in inflamed and non-inflamed skin. Cp

may occur as a common symptom in patients with dermatoses with primary skin lesions and systemic diseases without primary skin lesions. In systemic diseases, the skin may appear normal or have skin lesions induced by scratching or rubbing. In this case, a diagnosis might be difficult to establish. Systemic diseases frequently accompanied by pruritus are sum-marised in Table I. In some cases, pruritus may precede the diagnosis of the underlying disease by years. In the past years, several mechanisms of pruritus on inflamed and normal skin have been identified (see original version of EDF guideline, www.euroderm.org). In the following paragraphs some frequent patient populations and systemic diseases inducing Cp are presented.

4.1.2. Pruritus in kidney disease. The

pathophysio-logy of CkD-associated pruritus is unknown. Im-plicated mechanisms have included direct metabolic factors like increased concentrations of divalent ions (calcium, magnesium), parathyroid hormone (pTh), histamine and tryptase, dysfunction of peripheral or central nerves, the involvement of opioid receptors

(µ- and κ-receptors) and xerosis cutis (dry skin) have been suggested as likely candidates (20–28). New data point to a possible role of microinflammation that is quite frequent in uraemia (20, 29).

4.1.3. Pruritus in hepatic diseases. In patients with

cho-lestasis due to mechanical obstruction, metabolic disor-ders or inflammatory diseases, CP is a frequent symptom (30). It may be quite severe and can even precede the diagnosis of e.g. pbC by years (31). In patients with infective liver disease (hepatitis b or C) or toxic liver disease (e.g. alcohol-induced), pruritus is less frequent. hepatic pruritus is often generalised, affecting palms and soles in a characteristic way (32). one hypothesis for the mechanism of hepatic pruritus suggests that high opioid tone influences neurotransmission (30). Success-ful treatment with µ-receptor opioid antagonists such as nalmefene supports this hypothesis (33). It has recently been shown that increased serum autotaxin levels (en-zyme that metabolizes lysophosphatidylcholine (LpC) into lysophosphatidic acid (LpA)) and thereby increased LPA levels are specific for pruritus of cholestasis, but not for other forms of systemic pruritus (34). rifampicin significantly reduced itch intensity and ATX activity in pruritic patients. The beneficial antipruritic action of rifampicin may be explained partly by pregnane X receptor (PXR)-dependent transcription inhibition of ATX expression (34).

4.1.4. Pruritus in metabolic and endocrine diseases. In

endocrine disorders as hyperthyroidism and diabetes mel-litus, less than 10% of patients report pruritus (35, 36). In patients with hypothyroidism, pruritus is most probably driven by xerosis of the skin. patients with primary hy-perparathyroidism do complain about itch in a substantial number of cases (37). The pathophysiology of pruritus in primary hyperparathyroidism is not known. These pa-tients often experience a lack of vitamin D and minerals (e.g. zinc, etc.) which probably contributes to Cp.

Iron deficiency is frequently associated with pruritus (38). The mechanism for this is unknown. Iron overload as in hemochromatosis may lead to Cp (39, 40).

4.1.5. Pruritus in malignancy. Several malignant

dis-orders including tumours, bone marrow diseases and lymphoproliferative disorders may be accompanied by pruritus. In addition to toxic products generated by the tumour itself, allergic reactions to compounds released, and a direct affection on the brain or nerves (in brain tumours) may be the underlying mechanism (8, 41). In polycythemia vera (pV), more than 50% of patients suffer from pruritus (42, 43). Aquagenic pruritus with pinching sensations after contact with water is a charac-teristic but not necessary feature. It has been suggested that high levels of histamine released by the augmented numbers of basophilic granulocytes might trigger the itch (44). For pV this seems to be most pronounced in patients showing the JAk2 617V mutation (45).

Table I. Systemic diseases that can induce pruritus (examples)

Metabolic and

endocrine diseases • • Chronic renal insufficiency Liver diseases with or without cholestasis hyperparathyroidism

•

hyper- and hypothyroidism •

Iron deficiency •

Infective diseases • hIV and AIDS

parasitoses including helminthosis •

haematological

disorders • • polycythemia vera, myelodysplastic syndromeLymphoma, e.g. hodgkin lymphoma Neurological diseases • Multiple sclerosis

brain tumours • Notalgia paresthetica • brachioradial pruritus • postzosteric neuralgia • psychiatric or psychosomatic diseases Depression • Affective disorders • hallucinosis •

obsessive and compulsory disorders •

Schizophrenia •

Eating disorders •

pruritus in hodgkin’s disease often starts on the legs and is most severe at night, but generalised pruritus soon ensues. Several factors such as secretion of leukopepti-dases and bradykinine, histamine release and high IgE levels with cutaneous depositions may contribute to pruritus in lymphoma (46). patients with carcinoid syn-drome may experience pruritus in addition to flushing, diarrhoea and cardiac symptoms (47).

4.1.6. Pruritus in infectious diseases. Some generalised

infections are accompanied by pruritus. Above all, pa-tients infected with hIV may develop a pruritic papular eruption or eosinophilic folliculitis. These entities are easily diagnosed by inspection and histology of the skin and have a high positive predictive value (48, 49).

Whether toxocara infections lead to pruritus in a substantial number of patients remains to be confirmed (50).

4.1.7. Pruritus in neurological diseases. Multiple

scle-rosis, brain infarction and brain tumours are rarely ac-companied by pruritus (51, 52). Localised pruritus sug-gests a neurological origin such as compression of the peripheral or central afferences. This neuropathic origin of localised Cp can be found e.g. in postzosteric pruritus, notalgia paraesthetica and brachioradial pruritus, where an underlying spinal damage is likely (53–56).

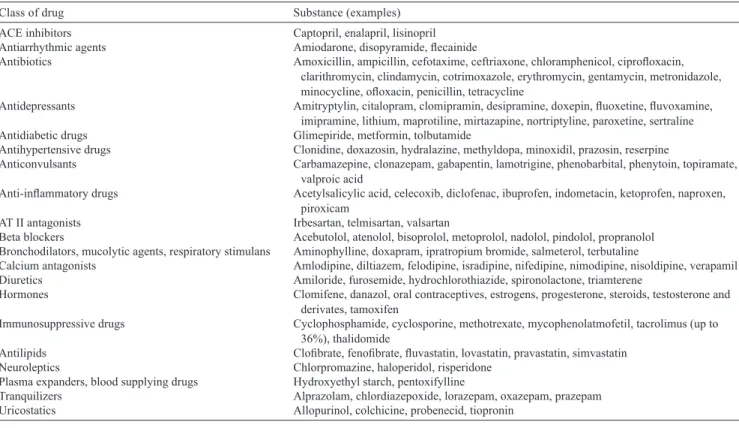

4.1.8. Drug induced chronic pruritus. Almost every drug

may induce pruritus by various pathomechanisms (Table II) (57). Some may cause urticarial or morbilliform

ras-hes presenting with acute pruritus. Furthermore, drug-induced hepatoxicity or cholestasis as well as drugs leading to xerosis or phototoxicity may produce Cp on normal skin (58). hydroxyethyl starch, a compound used for fluid restoration, can induce chronic generalised or localised pruritus (59).

4.2. Specific patient populations

4.2.1. Chronic pruritus in the elderly. only a small

number of studies have investigated pruritus in the elderly. They are characterised by selection bias and differing end points (pruritic skin disease or itch). An American study of cutaneous complaints in the elderly identified pruritus as the most frequent, accounting for 29% of all complaints (60). A Turkish study in 4,099 elderly patients found that pruritus was the commonest skin symptom with 11.5% affected. Women were more frequently affected (12.0%) than men (11.2%). patients older than 85 years showed the highest prevalence (19.5%) and pruritus was present more frequently in winter months (12.8%) (61). In a Thai study, pruritic diseases were the most common skin complaint (41%) among the elderly, while xerosis was identified as the most frequent ailment (38.9%) in a total of 149 elderly patients (62). The exact mechanisms of Cp in the el-derly are unknown. pathophysiological changes of the aged skin, decreased function of the stratum corneum, xerosis cutis, co-morbidities and polypharmacy may all contribute to its aetiology (63).

Table II. Drugs that may induce or maintain chronic pruritus (without a rash)

Class of drug Substance (examples)

ACE inhibitors Captopril, enalapril, lisinopril

Antiarrhythmic agents Amiodarone, disopyramide, flecainide

Antibiotics Amoxicillin, ampicillin, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin,

clarithromycin, clindamycin, cotrimoxazole, erythromycin, gentamycin, metronidazole, minocycline, ofloxacin, penicillin, tetracycline

Antidepressants Amitryptylin, citalopram, clomipramin, desipramine, doxepin, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, imipramine, lithium, maprotiline, mirtazapine, nortriptyline, paroxetine, sertraline

Antidiabetic drugs glimepiride, metformin, tolbutamide

Antihypertensive drugs Clonidine, doxazosin, hydralazine, methyldopa, minoxidil, prazosin, reserpine

Anticonvulsants Carbamazepine, clonazepam, gabapentin, lamotrigine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, topiramate, valproic acid

Anti-inflammatory drugs Acetylsalicylic acid, celecoxib, diclofenac, ibuprofen, indometacin, ketoprofen, naproxen, piroxicam

AT II antagonists Irbesartan, telmisartan, valsartan

beta blockers Acebutolol, atenolol, bisoprolol, metoprolol, nadolol, pindolol, propranolol

bronchodilators, mucolytic agents, respiratory stimulans Aminophylline, doxapram, ipratropium bromide, salmeterol, terbutaline

Calcium antagonists Amlodipine, diltiazem, felodipine, isradipine, nifedipine, nimodipine, nisoldipine, verapamil

Diuretics Amiloride, furosemide, hydrochlorothiazide, spironolactone, triamterene

hormones Clomifene, danazol, oral contraceptives, estrogens, progesterone, steroids, testosterone and

derivates, tamoxifen

Immunosuppressive drugs Cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, methotrexate, mycophenolatmofetil, tacrolimus (up to 36%), thalidomide

Antilipids Clofibrate, fenofibrate, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, simvastatin

Neuroleptics Chlorpromazine, haloperidol, risperidone

plasma expanders, blood supplying drugs hydroxyethyl starch, pentoxifylline

Tranquilizers Alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, lorazepam, oxazepam, prazepam

4.2.2. Chronic pruritus in pregnancy. There are no

epidemiological studies assessing the prevalence of Cp in pregnancy. pruritus is the leading dermatological symptom in pregnancy estimated to occur in about 18% of pregnancies (64). pruritus is the leading symptom of the specific dermatoses of pregnancy such as poly-morphic eruption of pregnancy (pEp), pemphigoid gestationis (pg), intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICp), atopic eruption of pregnancy (AEp), but may also occur in other dermatoses coinciding by chance with pregnancy or in pre-existing dermatoses (64–67). pEp is one the most common gestational dermatoses, affecting about one in 160 pregnancies. While pg, pEp and ICp characteristically present in late pregnancy, AEp starts in 75% of cases before the third trimester (1, 65, 68).

ICp is characterised by severe pruritus without any primary skin lesions, but secondary skin lesions occur due to scratching. It is more prevalent among native Indians in Chile (27.6%) and bolivia (13.8%) depending on ethnic predisposition and dietary factors (68, 69). ICp has decreased in both countries, e.g. to 14% in Chile. ICp is more common in women of advanced maternal age, multiple gestations, personal history of cholestasis on oral contraceptives and during winter months. Scan-dinavian and baltic countries are also more affected (1–2%). In Western Europe and North America, ICp is observed in in 0.4–1% of pregnancies (68–70).

The use of topical and systemic treatments depends on the underlying aetiology of pruritus and the stage and status of the skin. because of potential effects on the foetus, the treatment of pruritus in pregnancy requires prudent consideration of whether the severity of the un-derlying disease warrants treatment and selection of the safest treatments available. Systemic treatments such as systemic glucocorticosteroids, a restricted number of antihistamines and ultraviolet phototherapy, e.g. UVA, may be necessary in severe and generalised forms of Cp in pregnancy.

4.2.3. Chronic pruritus in children. There are no

epi-demiological studies assessing the prevalence of Cp in children (1, 64). Differential diagnosis of Cp in children has a wide spectrum (64) but is dominated by AD. The cumulative prevalence of AD is between 5 to 22% in developed countries. The german Atopic Dermatitis Intervention Study (gADIS) showed a sig-nificant correlation between the pruritus intensity and severity of AD and sleeplessness (71, 72). A Norwegian cross-sectional questionnaire-based population study in adolescents revealed a pruritus prevalence of 8.8%. pruritus was associated with mental distress, gender, sociodemographic factors, asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis and eczema (73). Itching of mild to moderate severity may occur in acne (74, 75).

There are no studies about systemic causes of Cp among children. It must be assumed that systemic cau-ses in children are mostly based on genetic diseacau-ses or

systemic diseases, e.g. biliary atresia or hypoplasia, fa-milial hyperbilirubinemia syndromes, polycystic kidney disease. Drug-induced pruritus without any specific skin symptoms appears to be rare in children (1). Common medications associated with Cp in adults play a minor role in children due to limited use at that age.

When considering treatment, the physician must remember that topically applied drugs may cause intoxication due to the different body volume/body surface area rate. In addition, the licensed age for the drug must be taken into account. Low- (class 1, 2) to medium-strength (class 3) glucocorticosteroids may be applied in children. Topical immunomodulators are used for AD and pruritus in children ≥ 2 years, but in some European countries e.g. pimecrolimus is licensed for use in children > 3 months. Topical capsaicin is not used in children < 10 years. The dosages of systemic drugs need to be adapted in children. Ultraviolet phototherapy should be performed with caution due to possible long-term photodamage of the skin.

5. DIAgNoSTIC MANAgEMENT

5.1. Patient’s history, examination and clinical characteristics of pruritus

The collection of the patient’s history and a thorough clinical examination are crucial at the first visit, as it forms an assessment of their pruritus including inten-sity, onset, time course, quality, localisation, triggering factors and the patient’s theory of causality. Attention should be paid to incidents preceding or accompanying the onset of pruritus (e.g. pruritus following bathing). It is also important to consider the methods used to relieve pruritus, e.g. brushes. This helps with the interpretation of clinical findings such as the absence of secondary skin lesions in the mid-back known as the “butterfly sign” that indicates that the patient cannot reach this area by hand and is thus unable to scratch it. It is also important to ask about preexisting diseases, allergies, atopic diathesis and drug intake (Table II). A great deal of helpful information can be obtained using questionn-aires. There are no definite clinical findings related to specific pruritic diseases (76), but awareness of the following anamnestic aspects and clinical findings may help with the diagnosis of the cause of pruritus:

When several family members are affected, scabies •

or other parasites should be considered.

The relationship between pruritus and special acti-•

vities is important: pruritus during physical activity is suggestive of cholinergic pruritus. It is common in patients with atopic eczema and mild forms of cholinergic pruritus. pruritus provoked by skin cooling after bathing should prompt consideration of aquagenic pruritus. It may be associated with or precede pV or myelodysplastic syndrome, and

screening for these diseases should be performed intermittently.

Nocturnal generalised pruritus associated with chills, •

fatigue, tiredness and “b” symptoms (weight loss, fever and nocturnal sweating) raises the possibility of hodgkin’s disease.

Somatoform pruritus rarely disturbs sleep; most •

other pruritic diseases cause nocturnal wakening. Seasonal pruritus frequently presents as “winter itch”, •

which may also be the manifestation of pruritus in the elderly due to xerosis cutis and asteatotic eczema. A patient’s history should always include all current and recent medications, infusions, and blood transfusions. Se-vere pruritus can lead to considerable psychological dist-ress. This should not be underestimated by the physician and should be addressed directly. Cp can be accompanied by behavioural/adjustment disorder and a withdrawal from social and work life (77). In these cases, psychosomatic counselling is required. Cp with excoriations sometimes progressing to self-mutilation can be caused by psychia-tric disease such as delusional parasitosis. Such patients need psychiatric examination and if necessary treatment. A solely psychological cause of pruritus should not be diagnosed without psychiatric examination.

Examination of patients with Cp includes a thorough inspection of the entire skin including mucous membra-nes, scalp, hair, nails, and anogenital region. The distri-bution of primary and secondary skin lesions should be recorded together with skin signs of systemic disease. general physical examination should include palpation of the liver, kidneys, spleen, and lymph nodes.

There is no standardised method of documenting pruritus. The sensation of pruritus is subject to much inter- and intra-individual variation due to tiredness, anxiety, stress. Questionnaires deliver self-reported information regarding various aspects of Cp. So far, no structured questionnaire exists, but the questionnaire should consider the patients’ perspective, the medical doctors’ perspective and needs of various measurements of clinical trials. Several different questionnaires in dif-ferent languages for difdif-ferent pruritic diseases have been developed, but so far no definite questionnaires exist. Additional tools are needed to better assess the different dimensions of Cp and better tailor management. With this goal in mind, a special interest group (SIg) was initiated by members of the IFSI to determine which of the various psychometric properties of Cp question naires offer the greatest utility in the evaluation of Cp (78). The intensity of pruritus is usually assessed by scales such as the visual analogue scale (VAS) or the numeric rating scale (79, 80). When using a VAS, the scale ranges from 0–10 and is graphically presented as a bar chart. howe-ver, these methods often fail to consider the frequency of itch attacks over the course of a day. For patients with severe pUo, it can be helpful to keep a diary in order to allow for clearer attribution of the symptoms.

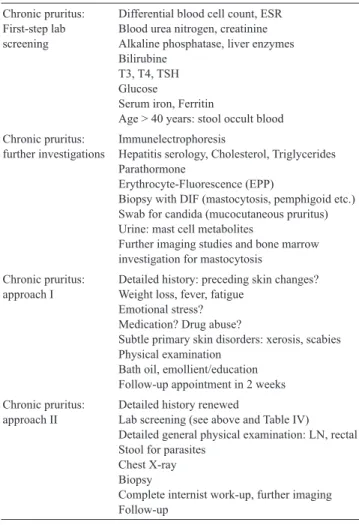

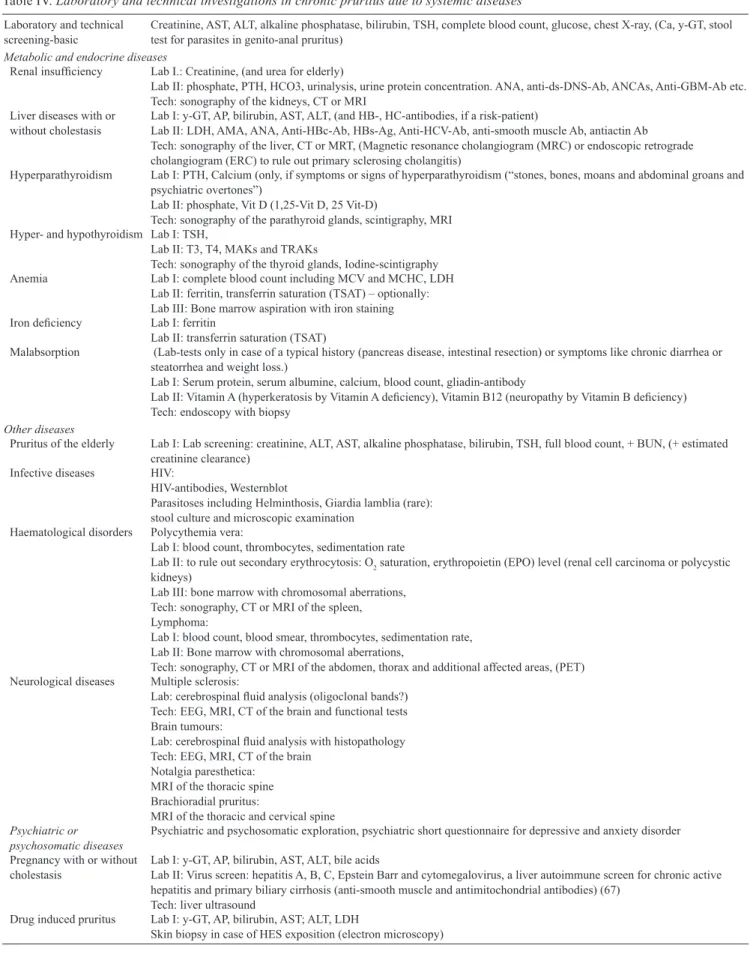

5.2. Diagnostic algorithm and diagnostics

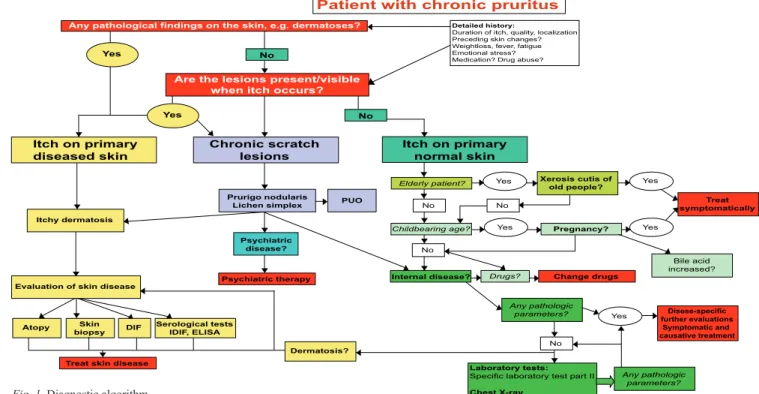

Laboratory screening, clinical and technical approaches and investigations are summarised in Table III and IV. All this helps to follow a diagnostic algorithm (Fig. 1). 6. ThErApy

6.1. General principles

In the patient with Cp it is important to establish an individual therapy regimen according to their age, pre-existing diseases, medications, quality and intensity of pruritus. Most importantly, elderly patients, pregnant women and children need special attention. As the care of patients with Cp often extends over a long period, with initial uncertainty about the origin of their pruritus, frus-tration regarding the failure of past therapies and general psychological stress frequently occurs. The diagnostic procedures and therapy should be discussed with the patient in order to achieve best possible concordance and compliance. It must be remembered that some therapies are not licensed for Cp and can only be prescribed “off-label”. This requires separate informed consent.

Table III. Diagnostics: laboratory screening, diverse approaches

and investigations Chronic pruritus: First-step lab screening

Differential blood cell count, ESr blood urea nitrogen, creatinine Alkaline phosphatase, liver enzymes bilirubine

T3, T4, TSh glucose

Serum iron, Ferritin

Age > 40 years: stool occult blood Chronic pruritus:

further investigations Immunelectrophoresishepatitis serology, Cholesterol, Triglycerides parathormone

Erythrocyte-Fluorescence (Epp)

biopsy with DIF (mastocytosis, pemphigoid etc.) Swab for candida (mucocutaneous pruritus) Urine: mast cell metabolites

Further imaging studies and bone marrow investigation for mastocytosis

Chronic pruritus:

approach I Detailed history: preceding skin changes?Weight loss, fever, fatigue Emotional stress?

Medication? Drug abuse?

Subtle primary skin disorders: xerosis, scabies physical examination

bath oil, emollient/education Follow-up appointment in 2 weeks Chronic pruritus:

approach II Detailed history renewedLab screening (see above and Table IV) Detailed general physical examination: LN, rectal Stool for parasites

Chest X-ray biopsy

Complete internist work-up, further imaging Follow-up

Table IV. Laboratory and technical investigations in chronic pruritus due to systemic diseases

Laboratory and technical

screening-basic Creatinine, AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, TSH, complete blood count, glucose, chest X-ray, (Ca, y-GT, stool test for parasites in genito-anal pruritus) Metabolic and endocrine diseases

Renal insufficiency Lab I.: Creatinine, (and urea for elderly)

Lab II: phosphate, pTh, hCo3, urinalysis, urine protein concentration. ANA, anti-ds-DNS-Ab, ANCAs, Anti-gbM-Ab etc. Tech: sonography of the kidneys, CT or MrI

Liver diseases with or

without cholestasis Lab I: y-gT, Ap, bilirubin, AST, ALT, (and hb-, hC-antibodies, if a risk-patient)Lab II: LDh, AMA, ANA, Anti-hbc-Ab, hbs-Ag, Anti-hCV-Ab, anti-smooth muscle Ab, antiactin Ab Tech: sonography of the liver, CT or MrT, (Magnetic resonance cholangiogram (MrC) or endoscopic retrograde cholangiogram (ErC) to rule out primary sclerosing cholangitis)

hyperparathyroidism Lab I: pTh, Calcium (only, if symptoms or signs of hyperparathyroidism (“stones, bones, moans and abdominal groans and psychiatric overtones”)

Lab II: phosphate, Vit D (1,25-Vit D, 25 Vit-D)

Tech: sonography of the parathyroid glands, scintigraphy, MrI hyper- and hypothyroidism Lab I: TSh,

Lab II: T3, T4, MAks and TrAks

Tech: sonography of the thyroid glands, Iodine-scintigraphy

Anemia Lab I: complete blood count including MCV and MChC, LDh

Lab II: ferritin, transferrin saturation (TSAT) – optionally: Lab III: bone marrow aspiration with iron staining Iron deficiency Lab I: ferritin

Lab II: transferrin saturation (TSAT)

Malabsorption (Lab-tests only in case of a typical history (pancreas disease, intestinal resection) or symptoms like chronic diarrhea or steatorrhea and weight loss.)

Lab I: Serum protein, serum albumine, calcium, blood count, gliadin-antibody

Lab II: Vitamin A (hyperkeratosis by Vitamin A deficiency), Vitamin B12 (neuropathy by Vitamin B deficiency) Tech: endoscopy with biopsy

Other diseases

pruritus of the elderly Lab I: Lab screening: creatinine, ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, TSh, full blood count, + bUN, (+ estimated creatinine clearance)

Infective diseases hIV:

hIV-antibodies, Westernblot

parasitoses including helminthosis, giardia lamblia (rare): stool culture and microscopic examination

haematological disorders polycythemia vera:

Lab I: blood count, thrombocytes, sedimentation rate

Lab II: to rule out secondary erythrocytosis: o2 saturation, erythropoietin (Epo) level (renal cell carcinoma or polycystic

kidneys)

Lab III: bone marrow with chromosomal aberrations, Tech: sonography, CT or MrI of the spleen, Lymphoma:

Lab I: blood count, blood smear, thrombocytes, sedimentation rate, Lab II: bone marrow with chromosomal aberrations,

Tech: sonography, CT or MrI of the abdomen, thorax and additional affected areas, (pET) Neurological diseases Multiple sclerosis:

Lab: cerebrospinal fluid analysis (oligoclonal bands?) Tech: EEg, MrI, CT of the brain and functional tests brain tumours:

Lab: cerebrospinal fluid analysis with histopathology Tech: EEg, MrI, CT of the brain

Notalgia paresthetica: MrI of the thoracic spine brachioradial pruritus:

MrI of the thoracic and cervical spine Psychiatric or

psychosomatic diseases psychiatric and psychosomatic exploration, psychiatric short questionnaire for depressive and anxiety disorder pregnancy with or without

cholestasis Lab I: y-gT, Ap, bilirubin, AST, ALT, bile acidsLab II: Virus screen: hepatitis A, b, C, Epstein barr and cytomegalovirus, a liver autoimmune screen for chronic active hepatitis and primary biliary cirrhosis (anti-smooth muscle and antimitochondrial antibodies) (67)

Tech: liver ultrasound

Drug induced pruritus Lab I: y-gT, Ap, bilirubin, AST; ALT, LDh

First, the patient should be informed about general pruritus-relieving measures (Table V). They include simple and helpful measures such as wet and cold wraps, application of lotio alba, etc. Application of short-time localised heat has shown promising itch-relieving results in case reports and an experimental study (81). prior to further symptomatic therapy, the patient should be subject to a careful diagnostic evaluation and therapy given for any underlying disease (see Tables III, IV). If pruritus still persists, combined or consecutive step-by-step sympto-matic treatment is necessary (Table VI). pharmacologic interventions for specific pruritic diseases, e.g. urticaria should be performed according to the guideline of the spe-cific disease and the field’s Cochrane Group (82, 83).

6.2. Causative therapy and aetiology specific treatment

Cp can be addressed by treating the underlying disease. Therapeutic measures include specific treatments of underlying dermatoses, avoidance of contact allergens, discontinuation of implicated drugs, specific internal, neurological and psychiatric therapies, surgical tre-atment of an underlying tumour or transplantation of organs. Normally, there is sudden relief of pruritus when the underlying disease improves, e.g. when hodgkin’s disease responds to chemotherapy or when a patient with pbC has been transplanted. For some underlying diseases, specific treatments have proven to be success-ful in relieving pruritus, even if the underlying disease is

▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼

Patient with chronic pruritus

Any pathological findings on the skin, e.g. dermatoses? Yes

Yes

No

Are the lesions present/visible when itch occurs?

No

Detailed history:

Duration of itch, quality, localization Preceding skin changes? Weightloss, fever, fatigue Emotional stress? Medication? Drug abuse?

Itch on primary

diseased skin Chronic scratchlesions Itch on primarynormal skin

Itchy dermatosis

Evaluation of skin disease

Atopy biopsySkin DIF Serological testsIDIF, ELISA

Dermatosis? Treat skin disease

Prurigo nodularis

Lichen simplex PUO

Psychiatric disease? Psychiatric therapy Elderly patient? Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No Xerosis cutis of old people?

Childbearing age? Pregnancy?

Bile acid increased?

Drugs? Change drugs

Treat symptomatically Disese-specific further evaluations Symptomatic and causative treatment Internal disease? Any pathologic parameters? Any pathologic parameters? Laboratory tests:

Specific laboratory test part II Chest X-ray ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ No ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼

Fig. 1. Diagnostic algorithm.

Table V. General measures for treating chronic pruritus

Avoidance of Factors that foster dryness of the skin, as e.g. dry climate, heat (e.g. sauna), alcoholic compresses, ice packs, frequent washing and bathing

Contact with irritant substances (e.g. compresses with rivanol, chamomile, tea-tree oil) Very hot and spicy food, large amounts of hot drinks and alcohol

Excitement, strain, negative stress

In atopic patients: avoidance of aerogen allergens (e.g. house dust and house dust mites) which may aggravate pruritus Application of Mild, non-alcaline soaps, moisturizing syndets and shower/bathing oils

Luke-warm water, bathing time not exceeding 20 min

In patients with dermatoses: after contact with water, the skin should be dabbed dry without rubbing, because damaged and inflamed skin might worsen

Soft clothing permeable to air, e.g. cotton, silver-based textiles Skin moisturizer on a daily basis especially after showering and bathing

Topicals with symptomatic relief especially for pruritus at night: creams/lotions/sprays with e.g. urea, campher, menthol, polidocanol, tannin preparations

Wet, cooling or fat-moist-wrappings, wrappings with black tea, short and lukewarm showers relaxation techniques Autogenic training, relaxation therapy, psychosocial education

Education Coping with the vicious circle of itch–scratch–itch

not treated. Aetiology specific treatments act on a known or hypothetically assumed pathogenesis of pruritus in underlying diseases. For only a few of these treatments evidence of efficacy can be found in controlled studies. Treatments for CP in specific diseases are presented in Tables VII–XI. When deciding the choice of treatment, consideration should be given to the level of evidence, side-effects, practicability, costs, availability of a treat-ment and individual factors such as patient’s age.

6.3. Symptomatic therapy: topical

6.3.1. Local anaesthetics. Local anaesthetics act via

different groups of skin receptors. They can be used for pain, dysaesthesia and pruritus. benzocaine, lidocaine, pramoxine as well as a mixture of prilocaine and lidocai-ne are widely used topically, but have only a short-term effect. In experimental studies, the antipruritic effect of local anaesthetics is limited in diseased skin, e.g. AD (84, 85). Successful application in the treatment of

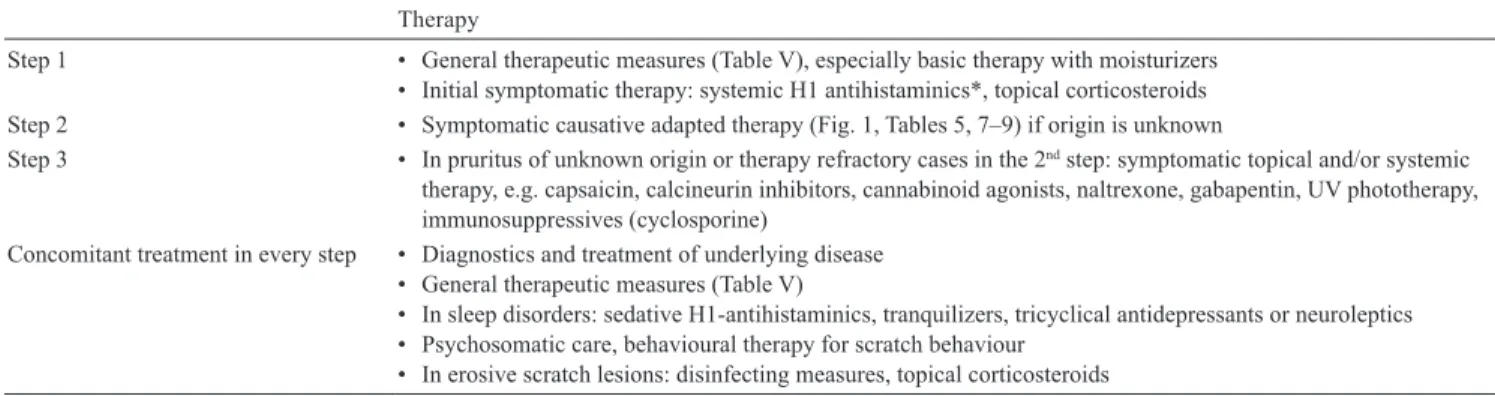

loca-Table VI. Stepwise symptomatic-therapeutic approach in chronic pruritus (> 6 weeks)

Therapy

Step 1 • general therapeutic measures (Table V), especially basic therapy with moisturizers Initial symptomatic therapy: systemic h1 antihistaminics*, topical corticosteroids •

Step 2 • Symptomatic causative adapted therapy (Fig. 1, Tables 5, 7–9) if origin is unknown

Step 3 • In pruritus of unknown origin or therapy refractory cases in the 2nd step: symptomatic topical and/or systemic

therapy, e.g. capsaicin, calcineurin inhibitors, cannabinoid agonists, naltrexone, gabapentin, UV phototherapy, immunosuppressives (cyclosporine)

Concomitant treatment in every step • Diagnostics and treatment of underlying disease general therapeutic measures (Table V) •

In sleep disorders: sedative h1-antihistaminics, tranquilizers, tricyclical antidepressants or neuroleptics •

psychosomatic care, behavioural therapy for scratch behaviour •

In erosive scratch lesions: disinfecting measures, topical corticosteroids •

*There is no evidence for the following diagnoses: cholestatic pruritus, nephrogenic pruritus

Table VII. Therapeutic options in chronic kidney disease-associated

pruritus

Antipruritic effects confirmed in controlled studies Activated charcoal 6 g/day (41)

•

gabapentin 300 mg 3

• ×/week postdialysis (170)

gamma-linolenic acid cream 3

• ×/day (261)

Capsaicin 3–5

• ×/day (98, 99)

UVb phototherapy (237) •

Acupuncture at the Quchi (LI11) acupoint (262) •

Nalfurafine intravenously postdialysis (25) •

Thalidomide 100 mg/day (211) •

Equivocal effects in controlled studies Naltrexone 50 mg/day (26, 27) •

ondansetron 8 mg orally or i.v. (202, 203) • Antipruritic effects confirmed in case reports Cholestyramine (41) • Tacrolimus ointment 2 • ×/day (124, 125)

Cream containing structured physiological lipids with • endocannabinoids (110) Mirtazapine (179) • Cromolyn sodium (151) • Erythropoetin 36 IU/kg 3 • ×/week (263) Lidocaine 200 mg i.v./day (41) • ketotifen 1–2 mg/day (150) •

Table VIII. Therapeutic options in hepatic and cholestatic

pruritus

Antipruritic effects confirmed in controlled studies

Cholestyramine 4–16 g/day (not in primarily biliary cirrhosis!) (31) •

Ursodesoxycholic acid 13–15 mg/kg/day (264) •

rifampicin 300–600 mg/day (265) (kremer, van Dijk 2012) • Naltrexone 50 mg/day (159, 266) • Naloxone 0.2 µg/kg/min (156) • Nalmefene 20 mg 2 • ×/day (157) Sertraline 75–100 mg/day (187) • Thalidomide 100 mg/day (267) •

Equivocal effects in controlled studies

ondansetron 4 mg or 8 mg i.v. or 8 mg orally (189, 190, 195, 196) • Antipruritic effects confirmed in case reports phenobarbital 2–5 mg/kg/day (268) • Stanozolol 5 mg/day (269) •

phototherapy: UVA, UVb (270) • Bright light therapy (10.000 Lux) reflected toward the eyes up to 60 • min twice/day (271) Etanercept 25 mg sc. 2 • ×/week (272) plasma perfusion (270) •

Extracorporeal albumin dialysis with Molecular Adsorbent •

recirculating System (MArS) (273–278) Liver transplantation (279)

•

Table IX. Antipruritic therapy of atopic dermatitis*

Antipruritic effects confirmed in controlled studies glucocorticosteroids (topical and oral) • Cyclosporin A • Leukotriene antagonists (e.g. zafirlukast) • Interferon-gamma, i.c. • Tacrolimus ointment (2 • ×/day) pimecrolimus cream (2 • ×/day) Doxepin 5% cream (2 • ×/day) (131, 132) Equivocal results:

Antihistamines (topical and systemic) • Naltrexon 50 mg/day (281) • Mycophenolatemofetil • Antipruritic effects confirmed in case reports Antipruritic effects confirmed in case reports: • Macrolide antibiotics • Immunoglobuline, i.v. • UVA1-/UVb 311-Therapie • Capsaicin (3–5 • ×/day)

lised forms of pruritus such as notalgia paraesthetica has been reported (85, 86). When treating larger skin areas, polidocanol 2–10% in different galenic formulations can be used, frequently in combination with 3% urea. There are no controlled clinical trials investigating the antipruritic effects of local anaesthetics.

Expert recommendation: Short term application of

topical local anaesthetics can be recommended as an additional therapy. The risk of sensitization can be considered as low.

6.3.2. Glucocorticosteroids. pruritus experimentally

induced by histamine was significantly suppressed by topical hydrocortisone when compared to placebo (87). All other clinical studies apply to an underlying inflammatory dermatosis in which ”pruritus” was one parameter amongst many. Clinical experience shows that topical glucocorticosteroids can be effective if itch is the consequence of an inflammatory dermatosis. Use of topical glucocorticosteroids to treat the symptom of pruritus is not advised in the absence of an inflam-matory dermatosis. Topical glucocorticosteroids with a favourable side-effect profile (e.g. fluticasonpropionate, methylprednisolon-aceponate or mometasonfuorate)

are to be preferred (88, 89). In some cases the anti-inflammatory effect of glucocorticosteroids is helpful, but insufficient to completely abolish pruritus (90).

Expert recommendation: Initial short-term application

of topical glucocorticosteroids can be recommended in CP associated with an inflammatory dermatosis, but should not be used as long-term treatment or in the absence of a primary rash.

6.3.3. Capsaicin. Capsaicin

(trans-8-metyl-N-vanillyl-6-nonenamide) is the pungent agent of chilli peppers and is used as a pain-relieving medication (91). Topical application of capsaicin activates sensory C-fibres to release neurotransmitters inducing dose-dependent erythema and burning. After repeated applications of capsaicin, the burning fades due to tachyphylaxis and retraction of epidermal nerve fibres (91). However, pruritus reoccurs some weeks after discontinuation of therapy indicating no permanent degeneration of the nerve fibres (92).

The greater the initial dose of capsaicin and the more frequent the applications, the sooner the desensitization will appear and pruritus disappear. Severe initial burning may be a side-effect of topical application. Cooling of the skin can also reduce the capsaicin-evoked burning. More unusual adverse effects of capsaicin include cough or sneezing due to inhalation of capsaicin from the skin or from the jar and its effect on sensory nerve fibres in the mucous membranes (91). It appears that such adverse effects are less bothersome for patients with severe pruritus compared to patients with slight pruritus (unpublished observations). A lower con-centration of capsaicin and less frequent applications will induce tachyphylaxis later but may give a better compliance. The concentration of capsaicin varies in different studies, but 0.025% capsaicin is tolerated well by most patients. If capsaicin is not available in this concentration as a standard drug it can be produced using a lipophilic vehicle. Capsaicin is also well soluble in alcohol; capsaicin 0.025% in spir dil can be used to treat itchy scalp (not published). A weaker concentration of 0.006% capsaicin is recommended for intertriginous skin e.g. pruritus ani (93).

Topical capsaicin’s effects have been confirmed in controlled clinical trials for different pain syndromes and neuropathy as well as notalgia paraesthetica (94), brachioradial pruritus (95), pruritic psoriasis (96, 97) and haemodialysis-related pruritus (98, 99). Case re-ports and case series described effects in hydroxyethyl starch-induced pruritus (100, 101), prurigo nodularis (100, 102–104), lichen simplex (100, 103), nummular eczema (100), aquagenic pruritus (105) and pUVA-associated pruritus (106).

Expert recommendation: Capsaicin can be effective in

localised forms of Cp, but patient compliance due to side-effects can restrict usage.

Table X. Therapeutic options in polycythaemia vera

Effects confirmed in case reports paroxetine 20 mg/day (42, 181) • hydroxyzine (42) • Fluoxetine 10 mg/day (181) • Aspirin (282) • Cimetidine 900 mg/day (283, 284) • pizotifen 0.5 mg 3 • ×/day (285) Cholestyramine (286) • Ultraviolet b phototherapy (241) • photochemotherapy (pUVA) (287, 288) •

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (289) •

Interferon-alpha (290–293) •

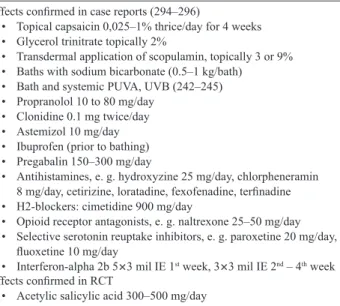

Table XI. Therapeutic options in aquagenic pruritus

Effects confirmed in case reports (294–296)

Topical capsaicin 0,025–1% thrice/day for 4 weeks •

glycerol trinitrate topically 2% •

Transdermal application of scopulamin, topically 3 or 9% •

baths with sodium bicarbonate (0.5–1 kg/bath) •

bath and systemic pUVA, UVb (242–245) • propranolol 10 to 80 mg/day • Clonidine 0.1 mg twice/day • Astemizol 10 mg/day •

Ibuprofen (prior to bathing) •

pregabalin 150–300 mg/day •

Antihistamines, e. g. hydroxyzine 25 mg/day, chlorpheneramin •

8 mg/day, cetirizine, loratadine, fexofenadine, terfinadine h2-blockers: cimetidine 900 mg/day

•

opioid receptor antagonists, e. g. naltrexone 25–50 mg/day •

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, e. g. paroxetine 20 mg/day, •

fluoxetine 10 mg/day Interferon-alpha 2b 5

• × 3 mil IE 1st week, 3 × 3 mil IE 2nd – 4th week

Effects confirmed in RCT

Acetylic salicylic acid 300–500 mg/day •

6.3.4. Cannabinoid receptor agonists. Topical

canna-binoid receptor agonists are a new development since 2003 and appear to have antipruritic and analgesic properties. Experimentally induced pain, pruritus and erythema could be reduced by application of a topical cannabinoid agonist (107, 108). one cosmetic product containing the cannabinoid receptor and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR-α) agonist, N-palmitoylethanolamine, is currently on the market. In (non-vehicle controlled) clinical trials and case series, it proved to have antipruritic effects in prurigo, AD, CkD-associated pruritus and pUo (109–111) as well as analgetic effects in postzosteric neuralgia (112).

Expert recommendation: Cannabinoid receptor agonists

can be effective in the treatment of localised pruritus.

6.3.5. Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus. The effects of

tacro-limus and pimecrotacro-limus on pruritus are mediated both through their immunological and neuronal properties (113). paradoxically, while they can induce transient pruritus at the beginning of treatment, in the medium-term they may provide an alternative treatment for many causes of pruritus. They are very effective against pruritus in AD (114). Furthermore, tacrolimus ointment is more effective at reducing pruritus when compared with ve-hicle and pimecrolimus cream (114). Clinical trials have shown benefit of both pimecrolimus and tacrolimus in seborrhoeic dermatitis, genital lichen sclerosus, inter-triginous psoriasis and cutaneous lupus erythematosus and – only for tacrolimus – in resistant idiopathic pruritus ani (115–122). In other diseases, the available data are limited to small case series, or individual cases e.g. hand eczema (pimecrolimus), rosacea (tacrolimus), graft-ver-sus-host disease (tacrolimus), vulval pruritus (tacrolimus) or Netherton’s syndrome (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus). Topical tacrolimus has been shown anecdotally to be ef-fective in pruritus associated with systemic diseases such as PBC (123) and chronic renal insufficiency (124, 125). However, these observations have not been confirmed in a controlled study on CkD-associated pruritus (126, 127). both substances can be used to treat localised forms of Cp such as genital pruritus (128).

Expert recommendation: Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus

are effective in localised forms of Cp.

6.3.6 Acetylsalicylic acid. Topical acetylsalicylic acid

(acetylsalicylic acid/dichlormethane solution) has been described to have antipruritic effects in occasional patients with lichen simplex (129). however, this be-neficial effect could not be confirmed in experimentally induced itch with histamine (130).

Expert recommendation: Due to the lack of studies,

topical acetylsalicylic acid can currently not be recom-mended for Cp.

6.3.7. Doxepin. The tricyclic antidepressant doxepin

showed antipruritic effects when applied as a 5% cream

in double-blind studies for treatment of AD (131), lichen simplex, nummular dermatitis and contact der-matitis (132). Topical doxepin therapy is not licensed and not used in any European country except for the UK (Xepin©) (133–135).

Expert recommendation: Due to the increased risk of

contact allergy, especially when the treatment exceeds 8 days, topical doxepin cannot be recommended.

6.3.8. Zinc, menthol and camphor. Although zinc oxide

has been used in dermatology for over 100 years due to its anti-inflammatory, antiseptic and anti-pruritic properties and its safety, there is only scarce literature on its effects. prescriptions of zinc are frequent, with concentrations varying from 10 to 50% in creams, lini-ments, lotions, ointments and pastes that are useful in the treatment of pruritus, especially for localised forms of pruritus, in children as well as in adults (136).

Menthol is an alcohol obtained from mint oils, or prepared synthetically. Applied to the skin and mucous membranes, menthol dilates blood vessels, causing a sensation of coldness, followed by an analgesic effect (136). Menthol is used in dusting powders, liniments, lotions and ointments in concentrations from 1–10% (136). Menthol binds to the TrpM8 receptor (137) that belongs to the same Trp family of excitatory ion channels as TrpV1, the capsaicin receptor. These two receptors have been shown to co-exist occasionally in the same primary afferent neurons and promote ther-mosensations at a wide range of temperatures: 8–28°C and > 50ºC, respectively (137). Short-term application of such medications in Cp in combination with other topical or systemic therapies can be recommended.

Camphor is an essential oil containing terpenes, it is soluble in alcohol (136). Applied to the skin it cau-ses a sensation of warmth that is followed by a mild degree of anaesthesia (136). Camphor has been used in dermatology for decades in liniments, lotions and ointments in concentrations from 2–20%. It has been shown to specifically activate another constituent of the Trp ion channel family, namely TrpV3 (138). recently, camphor was demonstrated to activate cap-saicin receptor, TrpV1, while menthol also activates the camphor receptor, TRPV3. These findings illustrate the complexity of sensory perception and explain the efficacy of ointments containing both menthol and camphor (136).

Expert recommendation: Short term application of

cam-phor, menthol and zinc in Cp in combination with other topical or systemic therapies can be recommended.

6.3.9. Mast cell inhibitors. In a multi-center,

double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, application of a 3% hydro-gel formulation of tiacrilast against vehicle in AD led to no significant improvement of pruritus (139). Pruritus in AD responds to topical sodium cromoglycate (140), that was proved by a recent placebo-controlled study (141).

Expert recommendation: There is limited evidence to

re-commend the use of topical mast cell inhibitors for Cp.

6.4. Systemic therapy

6.4.1. Antihistamines. Antihistamines are the most

wi-dely used systemic antipruritic drugs in dermatology. Most antihistamines that have been tried in pruritus belong to the h1 type. First generation antihistamines, such as chlorpheniramine, clemastine, cyproheptadine, diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, and promethazine are known to bind not only to h1-receptors but also to mus-carinic, α-adrenergic, dopamine or serotonin receptors and have a central sedative effect. Due to side effects, the application of sedative antihistamines is nowadays limited. Second generation antihistamines like cetiri-zine, levocetericetiri-zine, loratadine, desloratadine, ebastine, fexofenadine and rupafine have minimal activity on non-histaminic receptors, little sedative effect, and a longer duration of action compared to the first genera-tion (142). Non-sedative h1-receptor antagonists offer an effective reduction of pruritus in diseases associated with increased mast cell degranulation like urticaria or mastocytosis (142). however, the doses required to alleviating pruritus in urticaria often amount to up to four times the licensed dose (143). higher doses of the second generation antihistamines enhance their sopo-rific side effects (142), which may contribute to their efficacy. A recent case series suggest that updosing of antihistamines may also be beneficial in CP (144).

Systemic h1-antihistamines are often employed to combat itch in AD, but only sedative antihistamines have shown some benefit, mainly by improving sleep (145). hydroxyzine is the most commonly used antihistaminic of the first generation showing sedative, anxiolytic and antipruritic activities. In adult patients it is recommended as an antipruritic agent in the dosage 75–100 mg/day. In children the effective dose is 1–2.5 mg/kg/day. In a controlled study, addition of hydroxyzine resulted in a 750-fold increase in the dose of histamine required to elicit itch. There was a five-fold increase following both cyproheptadine and placebo and a ten-fold increase fol-lowing diphenhydramine (146). In addition, hydroxyzine was significantly more effective in reducing histamine-induced pruritus than neuroleptics, like thiothixene, chlorpromazine and thioridazine (147).

In addition, antihistamines are widely used as first-line drugs for treatment of Cp associated with different systemic diseases such as chronic renal failure, cho-lestasis, hematopoetic diseases and thyroid disorders. however, conventional doses of antihistamines in the treatment of pruritus in internal diseases have not proven to be effective (142).

Although identified in human skin, H2-receptors play a minor role in pruritus and h2-receptor antagonists alone have no antipruritic effect (145, 148). A

com-bination of h2-antihistamines and h1- antihistamines has been used in treatment of pruritus in small trials but the results are conflicting (145, 148). A combination of h1-antihistamine with a leukotriene antagonist has been reported to alleviate pruritus in chronic urticaria (149).

Expert recommendation: Antihistamines are effective

in treating Cp in urticaria. Antihistamines are of some value for itch in AD and Cp of diverse origin. As there is limited evidence of antipruritic effects of non-sedating antihistamines in AD, pV and Cp of diverse origin, sedating antihistamines can be recommended to be applied during night time for sleep improvement. Hydroxyzine is the first choice of the majority of phy-sicians trying to control Cp but its sedative effect may contraindicate its use in the elderly.

6.4.2. Mast cell inhibitors. ketotifen, a mast cell

sta-bilizer, showed antipruritic effects in single patients with CkD-associated pruritus (150). Two patients with CkD-associated pruritus (151) and hodgkin’s lym-phoma (152) showed a significant antipruritic effect with the mast cell stabilizer cromoglicic acid.

Expert recommendation: There is insufficient evidence

to recommend the systemic use of mast cell inhibitors for Cp.

6.4.3. Glucocorticosteroids. There are no studies

in-vestigating the efficacy of the exclusive use of systemic glucocorticosteroids in Cp. In clinical experience, pruri-tus ceases within approximately 30 min of i.v. glucocor-ticosteroids in the treatment of urticaria or drug-induced exanthema. Likewise, in AD, allergic contact dermatitis, dyshidrosis and bullous pemphigoid, rapid reduction of pruritus is observed, which can be explained by the high anti-inflammatory potency of glucocorticosteroids. Thus, while systemic glucocorticosteroids should not be considered as an antipruritic drug for long-term therapy, short-term use is possible in cases of severe pruritus, but should not be prescribed for a period of more than two weeks (153) because of severe side-effects.

prednisone is the most commonly selected oral cor-ticosteroid initially at a daily dose that can range from 2.5–100 mg daily or more, usually starting in a dose of 30–40 mg daily. In exceptional cases, i.v. methylpred-nisolone is used at a dose of 500 mg/day to 1 g/day, because of its high potency and low sodium-retaining activity. It is important to remember that the dosage should be tapered in accordance with the severity of pruritus. before discontinuing systemic therapy one may change to topical corticosteroid therapy. Corticosteroids should be used with caution in children and the elderly as well as in patients with relevant metabolic disorders such as diabetes.

Expert recommendation: Systemic corticosteroids can

be used as short-term treatment in severe cases of Cp, but should not be used for longer than 2 weeks.

6.4.4. Opioid receptor agonists and antagonists.

Experi-mental and clinical observations have demonstrated that pruritus can be evoked or intensified by endogenous or exogenous µ-opioids (154). This phenomenon can be explained by activation of spinal opioid receptors, mainly κ-opioid receptors. reversing this effect with µ-opioid antagonists thus leads to an inhibition of pruritus (112). The opposite is true for κ-opioids. Their binding to κ-opioid receptors leads to inhibition of pruritus (155).

Several clinical studies have demonstrated that dif-ferent µ-opioid receptor antagonists may significantly diminish pruritus (30, 33, 156–160). In double-blind RCT, µ-opioid receptor antagonists such as nalmefine, naloxone and naltrexone have exhibited high antipruritic potency. For example, pruritus in chronic urticaria, AD, and cholestatic pruritus has shown therapeutic response to nalmefene (10 mg twice daily) and naltrexone (50– 100 mg /day) (161, 162). Controlled studies have also been performed in patients with CkD-associated pruri-tus (26, 27, 163). Results were variable from significant reduction of pruritus to no response. Case reports have demonstrated efficacy in prurigo nodularis, macular amyloidosis, lichen amyloidosis, pruritus in mycosis fungoides, psoriasis vulgaris, aquagenic pruritus, hy-droxylethyl starch-induced pruritus and pUo.

Nalfurafine, a preferential κ-opioid receptor agonist, was investigated in CkD-associated Cp in two large RTCs (25, 164). Both trials demonstrated significant clinical benefit of nalfurafine in patients with uremic pruritus (155) within the first seven days of treatment. The drug is currently licensed in Japan only.

Expert recommendation: opioid receptor antagonists

may be effective in cholestatic pruritus and AD but their side-effect profile needs to be considered. Nalfurafine can be applied in Japanese patients with uremic pruritus.

6.4.5. Gabapentin and pregabalin. gabapentin is an

antiepileptic drug, also used in neuropathic disorders causing pain or pruritus (165). The mechanisms of action of gabapentin, a 1-amino-methyl-cyclo-hexane acetic acid and a structural analogue of the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) remain unclear. It is used in postherpetic neuralgia (166), especially with paroxysmal pain or pruritus. Anec-dotal indications are brachioradial pruritus (167) and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (168). pilot studies have been performed for the treatment of pruritus caused by burns and wound healing in children demonstrating antipruritic effects of gabapentin (169). Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trials were performed for CkD-associated pruritus (170) and cholestatic pruritus (171). gabapentin was safe and effective for treating CkD-associated pruritus (172, 173). pregaba-lin is similar to gabapentin and a more recent drug. Its use has been suggested in a case of cetuximab-related pruritus and aquagenic pruritus (174, 175). A recent

controlled trial demonstrated a significant antipruritic effect of pregabalin in patients on haemodialysis within one month (176).

Expert recommendation: gabapentin and pregabalin

can be recommended in the treatment of CkD-associ-ated pruritus and neuropathic Cp.

6.4.6. Antidepressants. psychoemotional factors are

known to modulate the ‘itch threshold.’ Under certain circumstances, they can trigger or enhance Cp (177). Itch is a strong stressor and can elicit psychiatric disease and psychological distress. Depressive disorders are present in about 10% of patients with Cp (77). Con-sequently, depressive symptoms are treated in these patients, and some antidepressants also exert an effect on pruritus through their pharmacological action on serotonin and histamine. SSrIs, such as paroxetine, can have an antipruritic effect on patients with pV, psycho-genic or paraneoplastic pruritus and other patients with chronic pUo (178). Antidepressants, like mirtazapine (179) and especially doxepin (180) have been effective in urticaria, AD and hIV-related pruritus.

The SSrI paroxetine (20 mg/day) has exhibited antipruritic effects in pruritus due to pV (181), para-neoplastic pruritus (182, 183) and psychiatric disease (184). In two patients, pruritus was induced by dis-continuation of paroxetine treatment for depression (185). A rCT in pruritus of non-dermatologic origin confirmed the antipruritic effect of paroxetine (178). In a two-armed proof-of-concept study with paroxetine and fluvoxamine, patients with CP of dermatological origin reported significant antipruritic effect (186). Sertralin proved efficacy in cholestatic pruritus as demonstrated in a rCT (187). As severe cardiac side effects have been described, especially in elderly, this therapy should be used with caution. A psychosomatic/psychiatric exa-mination before starting the treatment is recommended because of its stimulative effects.

Expert recommendation: SSrIs can be recommended

for the treatment of somatoform pruritus, paraneoplastic Cp, pUo and cholestatic pruritus. Mirtazapine can be recommended in Cp of AD.

6.4.7. Serotonin receptor antagonists. Due to the

patho-physiological significance of serotonin in different diseases such as kidney and liver diseases, serotonin receptor antagonists (of the 5-hT3 type) such as ondan-setron (8 mg 1–3/day), topiondan-setron (5 mg/day) and gra-nisetron (1 mg/day) have been used anecdotally to treat pruritus (188–194). Contradictory or negative results have been reported in partly controlled studies using ondansetron for cholestatic pruritus (188, 195, 196) and opioid-induced pruritus (197–199). An antipruritic effect was reported for ondansetron in CkD-associated pruritus (200). However, this could not be confirmed in subsequent controlled studies (201–203) later on.