FEMALE-LED PARTIES AND POLITICAL

GENDER STEREOTYPES:

INVESTIGATING THE IMPACT OF THE PARTY CHAIR’S GENDER ON

THE PERCEIVED IDEOLOGICAL POSITIONING OF POLITICAL

PARTIES IN FLANDERS

Aantal woorden: 24 996

Emma Boone

Stamnummer: 01404792Promotor: dr. Robin Devroe

Masterproef voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van: Master of Science in de Bestuurskunde en het Publiek Management Academiejaar: 2019 - 2020

PERMISSION

I declare that the content of this Master’s Dissertation may be consulted and/or

reproduced, provided that the source is referenced.

Student’s name: Emma Boone

Signature: Emma Boone

Preamble for master’s dissertations impacted by the

corona measures

As the COVID-19 virus insidiously seeped into our lives, it left a mark all around the globe, affecting millions and necessitating a degree of flexibility that has been unseen in recent years. Flexibility is also what was required of me to successfully complete this master’s thesis. For the sake of transparency, it is worth mentioning the nature of the adaptations that were made to this research.

Overall, the impact of the coronavirus outbreak on this master’s thesis has been limited to the data collection process. Initially, I had planned to collect the data for this research by attending certain lectures in person and asking students to fill out my online survey during those lectures. Unfortunately, the cancellation of all on-campus classes due to the rapid transmission of the COVID-19 virus in Belgium made this impossible. In consultation with my supervisor, Dr Robin Devroe, a new plan of action was decided on that entailed asking students to participate in the survey via the Ufora student platform of Ghent University. In keeping with this new approach, several professors were contacted with the request to share the link to the online survey with their students via the respective Ufora course pages. Preference was given to this platform as opposed to social media channels as members of the former platform are almost certainly students who are currently enrolled at Ghent University. The same degree of certainty cannot be applied to social media channels.

While it was quite difficult and time-consuming to find a sufficient number of respondents, eventually a satisfactory amount of data was collected. More details on the data collection process can be found in chapter 2 of this master’s thesis.

With regard to the remaining parts of this research, these could be carried out without any deviations from the original plan.

This preamble is drawn up in consultation between the student and the supervisor and is approved by both.

Summary in the official language of instruction (Dutch)

Heel wat onderzoek toont aan dat kiezers op basis van gender onder andere conclusies trekken over de politieke oriëntatie van politici, waarbij vrouwelijke politici vaak linkser worden ingeschat (Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993). Toch is er zo goed als niets geweten over hoe dergelijke ideologische genderstereotypen partijen met vrouwelijke partijvoorzitters beïnvloeden. Deze masterproef vormt een aanzet om deze leemte in de literatuur rond politieke genderstereotypering op te vullen. Concreet wordt nagegaan of Vlaamse universiteitsstudenten vrouwelijke partijvoorzitters en hun partijen linkser inschatten dan mannelijke partijvoorzitters en hun partijen. Daarnaast wordt ook onderzocht of het gender, de politieke interesse, en de politieke oriëntatie van studenten hun ideologische beoordeling van partijen met een vrouwelijke voorzitter beïnvloeden.

Om een antwoord te formuleren op bovenstaande onderzoeksvragen wordt een experimenteel onderzoeksopzet gehanteerd, waarbij via een online survey aan 200 Vlaamse studenten van de Universiteit Gent telkens twee van de zes mogelijke experimentele condities volledig gerandomiseerd wordt voorgelegd. De conditiemogelijkheden zijn een centrum, linkse of rechtse partij met telkens ofwel een vrouwelijke ofwel een mannelijke partijvoorzitter.

Uit de resultaten blijkt dat Vlaamse universiteitsstudenten wel degelijk ideologische genderstereotypes hanteren, maar enkel bij hun ideologische beoordeling van vrouwelijke centrumvoorzitters en hun partijen, en dat alleen het gender van studenten mogelijks een impact heeft op hun ideologische beoordeling van partijen onder vrouwelijk voorzitterschap. Het feit dat enkel vrouwelijke centrumvoorzitters en hun partijen significant linkser beoordeeld worden lijkt er enerzijds op te wijzen dat vooral zij te kampen krijgen met ideologische genderstereotypering. Anderzijds lijkt de afwezigheid van enig significant effect voor de linkse en rechtse partijvoorzitters en hun partijen ook aan te geven dat Vlaamse universiteitsstudenten enkel terugvallen op ideologische genderstereotypes in contexten waarin weinig concrete beleidsstandpunten bekendgemaakt worden (Pedersen et al., 2019). Dit zou willen zeggen dat vrouwelijke centrumvoorzitters en hun partijen gender-gerelateerde ideologische mispercepties zouden kunnen voorkomen door duidelijk te communiceren over hun beleidsstandpunten. Verder geven de resultaten ook weer dat mannelijke studenten in vergelijking met vrouwelijke studenten partijen onder vrouwelijk voorzitterschap linkser inschatten, alhoewel dit verband met enige voorzichtigheid benaderd moet worden aangezien het enkel significant is bij p ≤ 0.1.

Acknowledgements

Completing a master’s thesis in the middle of a global pandemic was quite the whirlwind. Indeed, finishing this concluding piece to my academic journey was a laborious process characterised by many moments of inspiration and enthusiasm, alternated with the inevitable moments of self-doubt and frustration. Luckily, I had many people who offered me a helping hand along the way, and they deserve a special thank you.

Firstly, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my thesis adviser Dr Robin Devroe, who helped me steer this research in the right direction. I could always count on her guidance and insightful feedback whenever I needed it. Furthermore, she also assisted me in my search for a sufficient number of respondents, as the suddenly implemented corona virus measures necessitated a new data collection approach.

Secondly, I would like to thank the following people for agreeing to share the link to my online survey with their students: Prof. Dr Thijs Van de Graaf, Ms Kaat Teerlinck, Prof. Dr Klaas Willems, Prof. Dr Mieke Van Houtte, Prof. Dr Bram Wauters, and Dr Tine Scheijnen. Without their cooperation, I would not have been able to successfully conduct my research.

Last but most certainly not least, I would like to thank my parents, boyfriend, and friends for their love and unwavering support, which were especially crucial during these turbulent times. I would not have been able to complete this master’s thesis without them. Thank you.

Table of contents

INTRODUCTION ... 1

CHAPTER 1: THEORETICAL BACKGROUND ... 5

1. WOMEN’S (UNDER)REPRESENTATION IN POLITICS ... 5

1.1 Defining the concept of representation ... 5

1.1.1 The four dimensions of representation ... 5

1.1.1.1 Formalistic representation ... 5

1.1.1.2 Descriptive representation ... 6

1.1.1.3 Substantive representation ... 7

1.1.1.4 Symbolic representation ... 7

1.1.2 The integrated nature of representation ... 8

1.2 The power of descriptive representation for women in politics ... 8

1.3 The difficult path towards women’s political recruitment ... 11

1.3.1 Hurdle one: finding the necessary resources and ambition ... 12

1.3.2 Hurdle two: being selected by the party gatekeepers ... 13

1.3.3 Hurdle three: getting elected ... 15

2. THE ISSUE OF POLITICAL GENDER STEREOTYPES ... 16

2.1 Defining the concept of political gender stereotypes ... 16

2.1.1 Stereotyping ... 16

2.1.2 Gender stereotyping ... 17

2.1.3 Political gender stereotyping ... 18

2.1.3.1 Gender-trait or issue competence stereotypes ... 18

2.1.3.2 Gender-belief or ideological position stereotypes ... 19

2.1.3.3 A quick glance at research on the prevalence of political gender stereotypes ... 20

2.2 Factors influencing the impact of political gender stereotypes ... 22

2.2.1 The electoral system ... 22

2.2.2 Individual characteristics of the candidate ... 23

2.2.2.1 Physical appearance ... 23

2.2.2.2 Partisanship ... 24

2.2.3 Individual characteristics of the voter ... 25

2.2.3.1 Social categorization theory ... 25

2.2.3.2 Exposure theory ... 28

3. PERCEIVING POLITICAL PARTIES’ IDEOLOGIES THROUGH A GENDERED LENS ... 29

3.1 The (in)stability of citizens’ party ideology perceptions ... 29

3.2 The influential role of the party leader ... 30

3.2.1 The party leader: a powerful figure in the political landscape ... 30

3.2.1.1 A closer look at party leadership in Belgium ... 31

3.3 The party leader’s gender and citizens’ party ideology perceptions ... 33

CHAPTER 2: THE RESEARCH ... 35

1. SITUATING THE RESEARCH AIMS, RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES ... 35

2. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY ... 38

2.1 Data collection: the experimental survey design ... 38

2.1.1 Survey part 1: background information on the participants ... 40

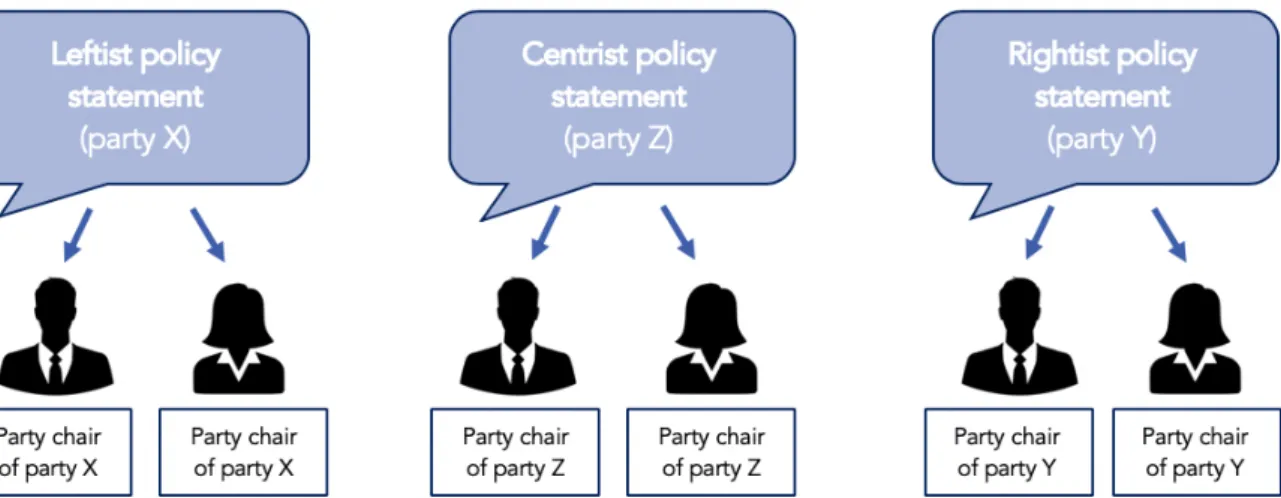

2.1.2 Survey part 2: the political party treatments ... 41

2.1.3 Survey part 3: the treatment questions ... 44

2.2 The research population and sample ... 45

2.3 Data analysis: independent samples t-tests and multiple regression ... 48

CHAPTER 3: RESULTS ... 52

1. RESEARCH QUESTION 1: EXPLORING THE PRESENCE OF IDEOLOGICAL POSITION STEREOTYPES ... 52

1.1 Ideological position stereotypes about female party leaders ... 52

1.1.1 Analysis on an aggregated level ... 52

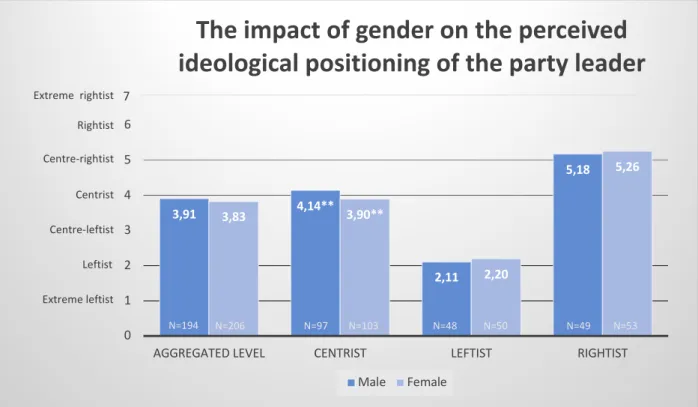

1.1.2 Analyses per ideological party profile ... 53

1.2 Ideological position stereotypes about female-led political parties ... 54

1.2.1 Analysis on an aggregated level ... 55

1.2.2 Analyses per ideological party profile ... 55

2. RESEARCH QUESTION 2: VOTER CHARACTERISTICS AND IDEOLOGICAL POSITION STEREOTYPES ... 57

2.1 The influence of voters’ gender ... 57

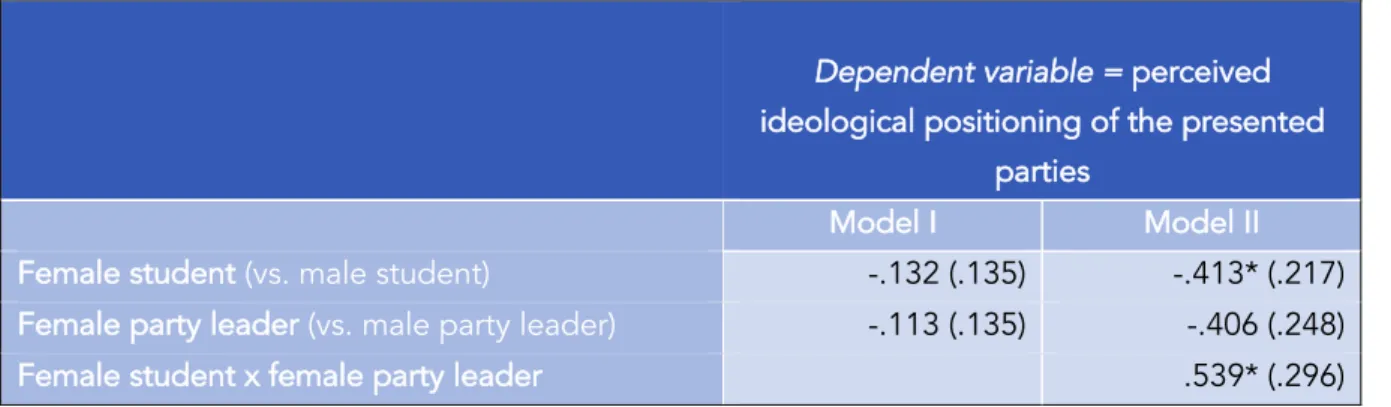

2.1.1 Analysis on an aggregated level ... 57

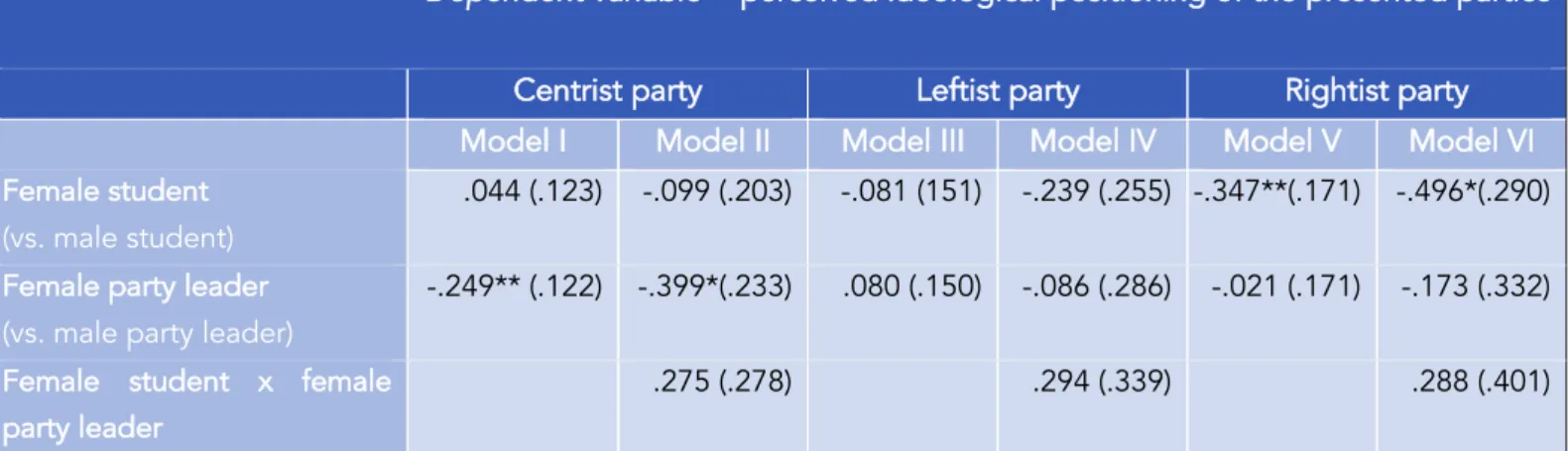

2.1.2 Analyses per ideological party profile ... 59

2.2 The influence of voters’ political interest ... 61

2.2.1 Analysis on an aggregated level ... 61

2.2.2 Analyses per ideological party profile ... 62

2.3 The influence of voters’ political orientations ... 64

2.3.1 Analysis on an aggregated level ... 64

2.3.2 Analyses per ideological party profile ... 65

CHAPTER 4: DISCUSSION ... 67

CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSION ... 74 BIBLIOGRAPHY ... I APPENDIX 1: THE ONLINE SURVEY ... XIII APPENDIX 2: OUTPUT STATISTICAL ANALYSES ... XXXVI

List of tables and figures

List of tables

TABLE 1:REGRESSION MODEL PREDICTING THE PERCEIVED IDEOLOGICAL POSITIONING OF THE PARTIES BASED ON STUDENTS’ GENDER, THE PARTY LEADER’S GENDER, AND THE INTERACTION BETWEEN STUDENTS’ AND THE PARTY LEADER’S GENDER (*P≤0.1,

**P≤0.05,***P≤0.01). ... 58 TABLE 2:REGRESSION MODEL PREDICTING THE PERCEIVED IDEOLOGICAL POSITIONING OF CENTRIST, LEFTIST, AND RIGHTIST PARTIES

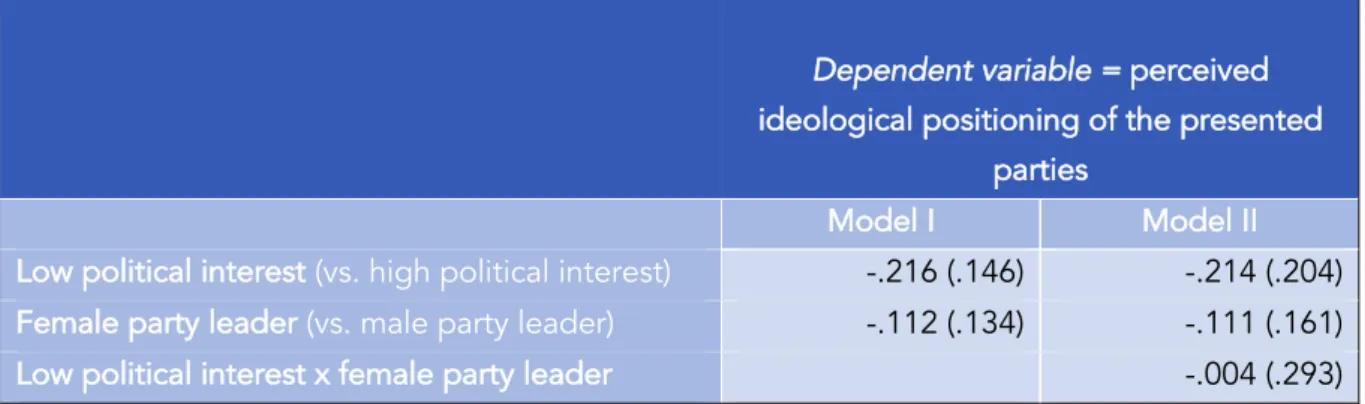

BASED ON STUDENTS’ GENDER, PARTY LEADER’S GENDER, AND THE INTERACTION BETWEEN STUDENTS’ AND THE PARTY LEADER’S GENDER (*P≤0.1,**P≤0.05,***P≤0.01). ... 60 TABLE 3:REGRESSION MODEL PREDICTING THE PERCEIVED IDEOLOGICAL POSITIONING OF PARTIES BASED ON STUDENTS’ POLITICAL

INTEREST, THE PARTY LEADER’S GENDER, AND THE INTERACTION BETWEEN POLITICAL INTEREST AND THE PARTY LEADER’S GENDER

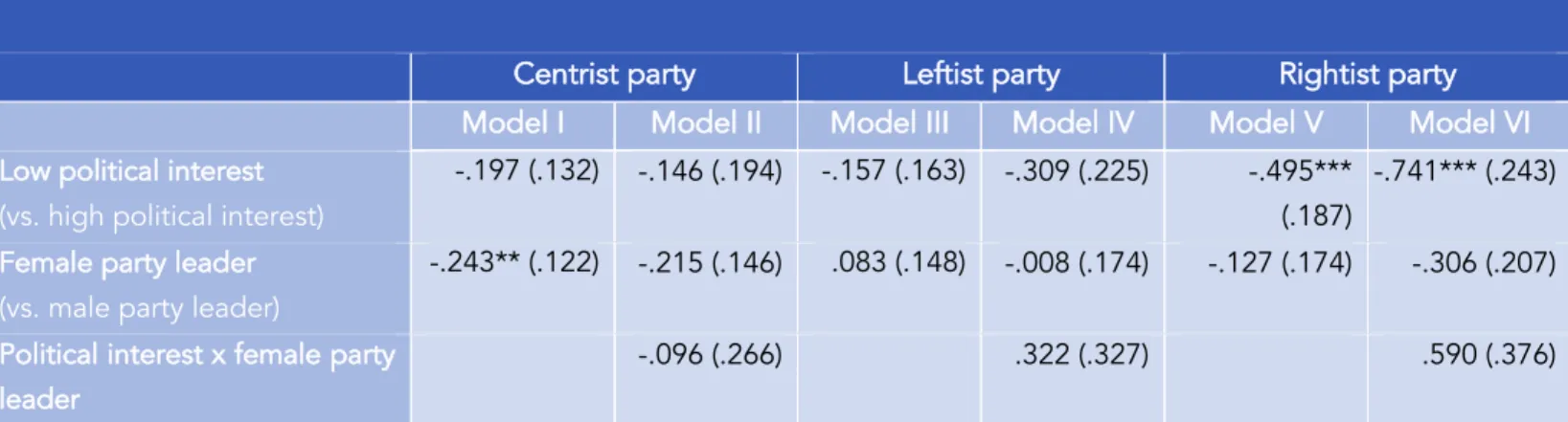

(*P≤0.1,**P≤0.05,***P≤0.01). ... 61 TABLE 4:REGRESSION MODEL PREDICTING THE PERCEIVED IDEOLOGICAL POSITIONING OF CENTRIST, LEFTIST, AND RIGHTIST PARTIES

BASED ON STUDENTS’ POLITICAL INTEREST, THE PARTY LEADER’S GENDER, AND THE INTERACTION BETWEEN POLITICAL INTEREST AND THE PARTY LEADER’S GENDER (*P≤0.1,**P≤0.05,***P≤0.01). ... 62 TABLE 5:REGRESSION MODEL PREDICTING THE PERCEIVED IDEOLOGICAL POSITIONING OF PARTIES BASED ON STUDENTS’ POLITICAL

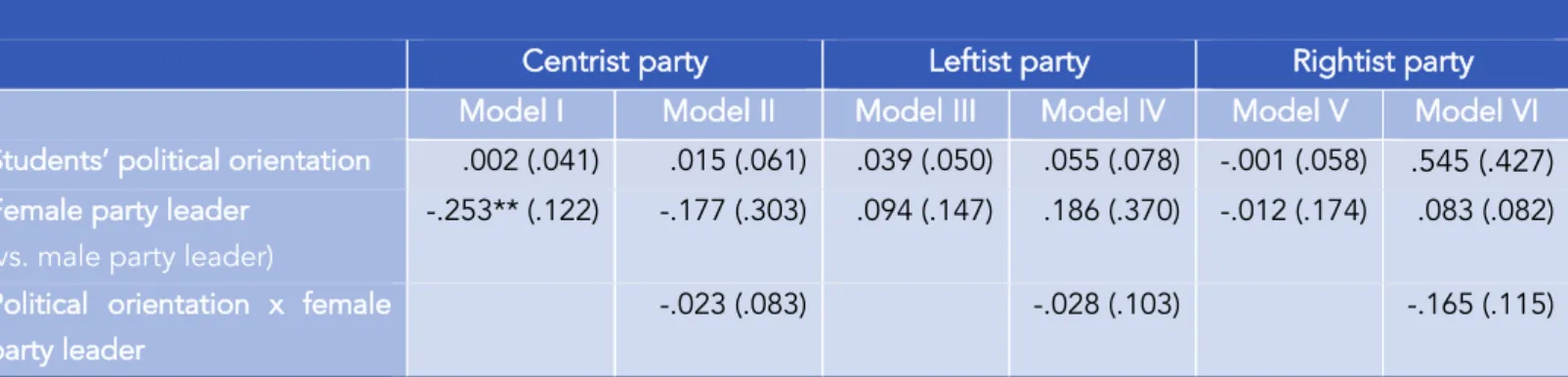

ORIENTATIONS, THE PARTY LEADER’S GENDER, AND THE INTERACTION BETWEEN STUDENTS’ POLITICAL ORIENTATIONS AND THE PARTY LEADER’S GENDER (*P≤0.1,**P≤0.05,***P≤0.01). ... 65 TABLE 6:REGRESSION MODEL PREDICTING THE PERCEIVED IDEOLOGICAL POSITIONING OF CENTRIST, LEFTIST, AND RIGHTIST PARTIES

BASED ON STUDENTS’ POLITICAL ORIENTATIONS, THE PARTY LEADER’S GENDER, AND THE INTERACTION BETWEEN STUDENTS’ POLITICAL ORIENTATIONS AND THE PARTY LEADER’S GENDER (*P≤0.1,**P≤0.05,***P≤0.01). ... 65

List of figures

FIGURE 1:THE POLITICAL RECRUITMENT PROCESS.ADAPTED FROM MATLAND,R.E.(2005).ENHANCING WOMEN’S POLITICAL PARTICIPATION:LEGISLATIVE RECRUITMENT AND ELECTORAL SYSTEMS.IN J.BALLINGTON &A.KARAM (EDS.),WOMEN IN PARLIAMENT:BEYOND NUMBERS (P.94).STOCKHOLM:INTERNATIONAL IDEA. ... 12

FIGURE 2:GRAPHIC OVERVIEW OF THE DIFFERENT EXPERIMENTAL TREATMENT CONDITIONS. ... 42 FIGURE 3:SCHEMATIC OVERVIEW OF THE TESTED HYPOTHESES. ... 48 FIGURE 4:AVERAGE SCORES FOR THE PERCEIVED IDEOLOGICAL POSITIONING OF MALE AND FEMALE PARTY LEADERS ON A SCALE

RANGING FROM EXTREME LEFTIST TO EXTREME RIGHTIST (*P≤0.1,**P≤0.05,***P≤0.01). ... 54 FIGURE 5:AVERAGE SCORES FOR THE PERCEIVED IDEOLOGICAL POSITIONING OF MALE- AND FEMALE-LED PARTIES ON A SCALE RANGING FROM EXTREME LEFTIST TO EXTREME RIGHTIST (*P≤0.1,**P≤0.05,***P≤0.01). ... 56

INTRODUCTION

Over the years, women’s gradual entrance into politics has instigated significant change in the political arena. Once excluded from the all-male political scene, women have since claimed their rightful place at the table and are progressively strengthening their presence in politics by vying for party leadership positions, as well as prime ministerial and presidential mandates (O’Brien, 2015, 2019).

Notwithstanding this general increase in the number of female politicians, the overall gains in women’s representation remain nevertheless minimal (Gelb & Palley, 2009; O’Brien, 2019). On a global scale, women currently hold a mere 24.9% of seats in parliament (UN Women & Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2020), which constitutes an increase of only 6.1% compared to the number of seats held in 2010 (UN Women & Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2010). Gender parity in political participation, thus, continues to be the exception rather than the rule (Gelb & Palley, 2009; O’Brien, 2019). In fact, no more than roughly 14 countries in the world presently have a government in which at least half of the ministers are women. Moving up the hierarchical ladder, female representation becomes even more scarce, with only 6.2% female heads of government and 6.6% female heads of state in 2020 (UN Women & Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2020). These numbers seem to indicate that, to this day, female politicians are still not competing on an equal footing with their male counterparts.

The persistent underrepresentation of women in politics is not inconsequential. It diminishes the degree to which political parties and institutions resemble and reflect societal diversity and, consequently, casts doubt on their representativeness and their ability to promote the interests of those who they ought to represent (Celis et al., 2010; Devroe et al., 2019; Pitkin, 1972). Indeed, in accordance with the politics of presence theory put forward by Phillips (1995), it is often argued that the interests of different social groups are best articulated by members belonging to that same group, as representatives’ personal characteristics are believed to affect their life experiences and the issues they prioritize (Devroe et al., 2019; Paolino, 1995; Phillips, 1995; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005). This implies that the composition of political parties and

institutions may influence the contents of political debates as well as the actual policy-making process (Devroe et al., 2019).

Previous research aimed at untangling the issue of women’s political underrepresentation has found that women face various barriers when trying to enter and thrive in the world of politics (Celis & Meier, 2006; Matland, 2005). One of these barriers is political gender stereotyping. Considering that voters often do not possess the necessary time, resources or motivation to thoroughly inform themselves about every election candidate, they rely on heuristics such as gender to facilitate their choice (Devroe & Wauters, 2018). In doing so, voters subconsciously make biased assessments about a candidate’s beliefs and traits, which, in the case of sex, often occurs to the detriment of female politicians (Devroe & Wauters, 2018). Several studies have demonstrated that the attribution of stereotypical ‘womanly’ characteristics (e.g. compassionate, warm, sensitive, nurturing, willing to compromise, etc.) to female politicians can lead voters to believe that women are more leftist (so-called ideological position stereotypes), or less competent (so-called issue competence stereotypes) unless for issues that can be linked to the traditional domain of the family, such as health care or education (Alexander & Andersen, 1993; Devroe, 2019; Dolan, 2014a; Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993; O’Brien, 2019).

While the prevalence of political gender stereotyping has been extensively studied in the United States, research on its presence in other parts of the world remains rather limited (Devroe & Wauters, 2018). Considering that the occurrence and extent of political gender bias is highly dependent on contextual factors, it is important to expand the scope of the research to other countries (Devroe, 2019; Inglehart et al., 2002; Matland, 2005).

Furthermore, thus far comparatively little attention has been dedicated to the impact of political gender stereotypes on female party leaders in particular (O’Brien, 2015, 2019). Nevertheless, party leaders play a highly important role in the political scene, even more so in particracies such as Belgium (Devroe et al., 2019). Their popularity, or lack thereof, can be a determining factor in their party’s electoral success and their decisions constitute the basis for the formation, sustainment, and removal of government (Bittner, 2011; O’Brien, 2015). In addition, they shape party policy and commonly fill the most prestigious posts available to the party, often including the position of prime minister though not always (e.g. Belgium) (O’Brien, 2015).

Moreover, the relatively few scholars that have examined the influence of political gender bias towards female party leaders have mainly focussed on issue competence stereotypes, while ideological position stereotypes have received far less attention, especially the implications of such stereotype reliance for the party (Devroe, 2019; O’Brien, 2015, 2019; Yarkoney-Sorek et al., 2016). To my knowledge, only O’Brien (2019) has researched the link between a party leader’s gender and voters’ perceived ideological positioning of that party. Using public opinion data from 35 countries, her findings demonstrate that female-led parties are viewed as more moderate (i.e. less leftist or rightist) than their male-led counterparts.

The possibility of such gender-biased ideological misperceptions about female-led parties certainly warrants further investigation, especially considering the importance of voters’ party ideology perceptions for both voters and political parties (O’Brien, 2019). Indeed, for representative democracy to function properly, it is critical that voters can accurately assess parties’ political ideologies so that they are able to shape government policy by voting for the party that will defend their political values and interests best (Adams et al., 2011; Devos, 2016; O’Brien, 2019). Considering their influence on vote choice, citizens’ party ideology perceptions are, accordingly, also important to political parties, as they can affect a party’s electoral success (Adams et al., 2011, 2014; Dalton & McAllister, 2015; Fernandez-Vazquez & Somer-Topcu, 2019). Thus, depending on the image a party wants to create for itself, ideological gender stereotypes about female party leaders and their parties could lead to female party leadership being preferred in some situations, but passed over for male party leadership in others (O’Brien, 2019).

So as to help bridge the aforementioned gaps in literature, this research will examine political gender bias towards party leaders in Flanders, the Dutch-speaking and largest area of Belgium. More specifically, this study investigates whether the party chair’s gender affects the way in which Flemish university students perceive the ideological positioning of political parties by employing an experimental survey research design. Based on Devroe and Wauters’ (2018) recent study in which Flemish female politicians were found to be regarded as more leftist by voters, it is hypothesized that female-led parties will also be perceived as more leftist than their male-led counterparts, irrespective of their actual ideological positions.

It should be noted that Flanders constitutes a highly interesting context in which to study the presence of political gender stereotyping, considering that it possesses situational factors that allow for a rather gender-neutral political scene compared to certain other countries such as the United States, where the vast majority of research on political gender stereotypes has been conducted. Indeed, being part of Belgium, Flanders has a proportional representation (PR) electoral system as well as gender quota regulations, both of which enhance women’s chances in the political sphere (Devroe, 2019; Matland, 2005). In addition, there is no overconcentration of female politicians among left-wing parties (Devroe, 2019). Instead, women are fairly evenly distributed over the different political parties, making it less likely that they will automatically be associated with a left-wing ideology (Devroe, 2019; Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993). While the aforementioned factors hold true for Belgium in its entirety, this study will solely focus on Flanders considering the limited scope of this master’s thesis and the differences in the electoral setting (e.g. smaller districts and different political culture) of Wallonia, the French-speaking and second largest area in Belgium (Devroe, 2019).

This master’s thesis starts out by providing the theoretical framework for this study in chapter 1. The chapter commences with a section on the general underrepresentation of women in politics, in which the concept of representation is elaborated on and linked to women’s political presence. The subsequent sections then tackle the issue of political gender stereotyping. A definition for the concept is provided, and various factors influencing its occurrence are discussed before considering the role of party leadership for voters’ ideological perceptions.

Subsequently, chapters 2 through 5 focus on the research itself with the design and methodology discussed in chapter 2. Firstly, the research questions and hypotheses are considered. Secondly, the methodology is elaborated on, providing details on the participants, the survey, the data collection and the data processing. Next, chapter 3 provides an overview of the results and chapter 4 discusses the interpretation of those results as well as the limitations to the study and future research avenues. Lastly, chapter 5 concludes the research by reiterating the main findings of the study.

Chapter 1:

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

1. Women’s (under)representation in politics

1.1 Defining the concept of representation

In her seminal work ‘The Concept of Representation’, Pitkin (1972) defines representation broadly as “the making present in some sense of something which is nevertheless not present literally or in fact” (Pitkin, 1972, pp. 8–9). Applied to a political context, representation thus refers to “the making present” of citizens’ voices (i.e. their interests, beliefs, concerns, etc.) in the political decision-making process by means of an intermediary, that is a representative or a group of representatives (Celis et al., 2010; Pitkin, 1972).

While defining representation in this manner provides a basic understanding of the concept, it is not enough to capture all of its facets. Indeed, the aforementioned definition leaves certain questions unanswered as it does not, for instance, clarify what makes this intermediary ‘representative’, why his or her actions and presence can be considered a form of ‘representation’, and what being a representative actually entails (Celis et al., 2010; Devos, 2016). In order to gain a deeper insight into the concept of representation it is necessary to elaborate on its four dimensions as distinguished by Pitkin (1972): formalistic, descriptive, substantive, and symbolic representation (Celis et al., 2010; Devos, 2016; Pitkin, 1972). Furthermore, it is important to note that although Pitkin (1972) identifies these four components of representation as being different from one another, she also heavily emphasizes their interconnectedness (Pitkin, 1972; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005).

1.1.1 The four dimensions of representation

1.1.1.1 Formalistic representationFormalistic representation refers to the institutional procedures, structures and rules through which representatives are appointed or removed (Devos, 2016; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005). A central component of this dimension is the binding agreement, limited in time and scope, that is made between the representative and the represented (Celis et al., 2010; Devos, 2016). By

virtue of this agreement, the represented grant the representative the authorization to act in their name, for which the latter is held accountable (Celis et al., 2010). Therefore, any action carried out by the representative after the agreement has been concluded, is considered to be ‘formalistically representative’ (Devos, 2016). However, this does not mean that representatives can do whatever they please without any repercussions. They remain responsible for their actions, and the agreement or mandate that provides them with the necessary legitimacy to act as a representative can be terminated (Devos, 2016). Formalistic representation is, thus, comprised of two main elements: (1) authorization or the process by which citizens allow a person, group, institution or organisation to act on their behalf, and (2) accountability or the mechanisms citizens can use to hold a representative accountable (Celis et al., 2010; Devos, 2016).

As a consequence, elections constitute an important step in the process of formalistic representation (Celis et al., 2010; Devos, 2016). Indeed, elections allow for both authorization and accountability to occur, as they not only provide general information on citizens’ preferences but also legitimise certain representatives and possibly rob others of that same legitimacy (Devos, 2016). Therefore, elections constitute the starting and end point of the binding agreement between the representative(s) and the represented (Celis et al., 2010; Devos, 2016).

1.1.1.2 Descriptive representation

Descriptive representation is concerned with the degree to which a representative and the people he or she ought to represent have certain characteristics in common, such as gender, level of education, class, ethnicity, et cetera (Celis et al., 2010; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005). Within this dimension, representatives are considered representative due to the similarities they bear with the represented, not due to their actions (Devos, 2016). Descriptive representation, thus, occurs when the body of representatives mirrors the composition of society (Devos, 2016; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005). This is considered to be an important dimension of the larger concept of representation, as it is deemed to ensure that representatives act in a manner that is similar to the way in which the represented would act (Celis et al., 2010; Devos, 2016; Mansbridge, 1999). Furthermore, descriptive representation is also of symbolic value, since societal groups that are part of the representative body are politically recognized, which, in turn, can create greater involvement and confidence in the political system (Celis et al., 2010; Devroe, 2019).

1.1.1.3 Substantive representation

Substantive representation occurs when representatives act in the interest of the represented in a way that is responsive to them (Devroe, 2019; Pitkin, 1972; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005). Whereas descriptive representation is, for instance, concerned with whether or not the number of women in parliament is reflective of the total number of women in society, substantive representation relates to whether these female representatives actually look after women’s interests (Devos, 2016). Consequently, substantive representation is often referred to as policy responsiveness, that is the extent to which representatives implement policies and enact laws that are responsive to citizens’ needs and demands (Devroe, 2019; Eulau & Karps, 1977; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005).

Various scholars, including Pitkin, posit that the substantive dimension is the most important aspect of representation. They argue that it is not necessarily who representatives are that matters most, but rather what they do to represent citizens (Devos, 2016; Pitkin, 1972; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005). Nevertheless, this assertion does not remain uncontested. Wahlke (1971), for instance, contends that policy responsiveness is sometimes too heavily emphasized considering that citizens generally have few coherent policy beliefs and legislators are not fully aware of citizens’ policy preferences apart from exceptional cases (Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005; Wahlke, 1971).

1.1.1.4 Symbolic representation

Similar to descriptive representation, symbolic representation refers to the degree to which representatives stand for the citizens they ought to represent, although here emphasis is placed on symbols or symbolization rather than on shared characteristics between the representatives and the represented (Devroe, 2019; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005). A flag or a king can, for instance, personify a people or nation when symbolic qualities are attributed to this object or person (Devos, 2016; Pitkin, 1972; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005). What matters within this dimension is the feelings or attitudes evoked by the symbol, not the symbol itself (Pitkin, 1972; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005). Consequently, symbolic representation relates to the way in which representatives are perceived and evaluated by the represented. It captures the extent to which representatives are accepted by the represented (Devos, 2016). Who these representatives

are and which actions they perform are not considered within this aspect of representation (Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005).

1.1.2 The integrated nature of representation

Even though the aforementioned dimensions are often distinguished from one another when conceptualizing the meaning of representation, it is important to emphasize that these four facets are nevertheless interconnected (Devroe, 2019; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005). In her authoritative exposition on representation, Pitkin (1972) questions the representative quality of institutions that subsume merely one or even a few dimensions but lack others (Pitkin, 1972; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005). A legislature should, for instance, not be deemed representative solely because it mirrors the diverse composition of the represented, nor because citizens approve of it. Similarly, a benevolent dictatorship should not be viewed as representative merely because the dictator in question carries out policies that are responsive to citizens’ needs and demands (Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005). Consequently, institutions should only be considered representative when they reach some minimum on every dimension of representation (Devroe, 2019; Pitkin, 1972; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005).

Furthermore, a substantial amount of literature supports the existence of causal connections amongst the different dimensions of representation (Bratton, 2005; Celis et al., 2010; Pitkin, 1972; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005). Formalistic representation, for instance, was found to promote descriptive representation, facilitate policy responsiveness, and improve citizens’ confidence in representative institutions (Celis et al., 2010; Celis & Meier, 2006; Matland, 2005; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005). Additionally, empirical findings have demonstrated that descriptive representation enhances both symbolic and substantive representation (Bratton, 2005; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005; Wängnerud, 2009). In other words, the four dimensions of representation are not stand-alone types of representation that operate entirely independently from one another. Consequently, representation should be viewed as an integrated and multidimensional concept (Pitkin, 1972; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005).

1.2 The power of descriptive representation for women in politics

While acknowledging the multifaceted nature of representation, the subject of this master’s thesis is most closely aligned with the descriptive dimension. This dimension is considered to be the

keystone of women’s representation and is sometimes even described as the “glue” that binds the four dimensions of representation together (Devroe, 2019, p. 24; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005, p. 423). There is a variety of reasons why many scholars emphasize the importance of descriptive representation.

As previously mentioned (see supra 1.1.2), descriptive representation has a positive impact on symbolic representation. Indeed, the percentage of female legislators is a principal determinant of women’s confidence in the legislature (Bayer & Mishler, 2005). Moreover, Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler (2005), and Karp and Banducci (2008) found that men’s confidence in the legislature is just as affected by female underrepresentation as women’s. This implies that women’s descriptive representation leads to greater perceived legitimacy amongst both men and women, which, in turn, facilitates the proper functioning and stability of the political system (Devroe, 2019; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005). In addition, the positive impact of descriptive representation on symbolic representation was found to accelerate as the percentage of female representatives increased (Karp & Banducci, 2008; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005).

Furthermore, the inclusion of female representatives facilitates the adoption of laws and policies that promote female interests (Celis et al., 2010; Devroe, 2019; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005). In her influential work ‘The Politics of Presence’, Phillips (1995) posits that “different groups have different kinds of interests, and that, failing more equitable distribution of political office between different groups, there is little basis for believing that public policy will be equitable between all” (Phillips, 1995, p. 145). Phillips’ (1995) theory, thus, suggests a relationship between the descriptive and substantive dimension of representation. Indeed, women are considered to be better equipped to promote female interests, since female politicians share, to a certain degree, the experiences of other women (Devroe, 2019; Mansbridge, 1999; Phillips, 1995; Wängnerud, 2009).

Empirical findings corroborate the relationship between descriptive and substantive representation, indicating that the presence of female representatives can positively affect the promotion of female interests (Bratton, 2005; Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005; Wängnerud, 2009). This positive impact has, again, been found to accelerate as the percentage of women augments (Schwindt-Bayer & Mishler, 2005). Nevertheless, it should be noted that there are various political,

social, and individual factors that can interfere with policy responsiveness (Celis et al., 2010; Reingold, 2000). Therefore, while having more female representatives increases the likelihood that more attention will go to the promotion of women’s interests, it is not a guarantee (Celis et al., 2010).

However, it is not only important that women are descriptively represented in the legislature. Their presence in the upper echelons of politics is just as crucial, including the upper echelons of political parties (O’Brien, 2015). In fact, women’s presence among the party elite can actually enhance the general representation of female politicians (O’Brien, 2015). It can, for instance, increase the odds of female candidates being nominated by the party gatekeeper(s) (i.e. the person or people responsible for candidate recruitment), and can raise the likelihood that a party will adopt affirmative action policies such as gender quotas (Caul, 2001; Cheng & Tavits, 2011; Kittilson, 2006, 2011; O’Brien, 2015).

Additionally, descriptive representation of underrepresented societal groups in (top) political positions is also believed to contribute to their emancipation (Devroe, 2019). Through this type of representation, these groups become politically recognized, signalling to society that their demands and concerns matter and that they are equally competent and deserving to be in power as more dominant groups (Celis et al., 2010; Devroe, 2019; Mansbridge, 1999). In addition, it might encourage members of such groups to vie for (top) political positions themselves (O’Brien, 2015).

Despite the importance of the descriptive dimension for women’s representation and other societal groups that are currently underrepresented in politics (e.g. ethnic minorities), its significance should nevertheless remain nuanced. Firstly, too strong of an emphasis on social identities can emphasize group differences in society in such a way that it can hamper social cohesion or social alliance, as it can lead citizens and politicians to look more at what sets them apart than at what binds them together (Phillips, 1995; Young, 2000). Secondly, focussing too strongly on descriptive characteristics such as gender or race can result in essentialism (Mansbridge, 1999; Wängnerud, 2009). This refers to the assumption that a single trait or nature binds every person who shares that trait together into a group that has common interests, thus ignoring differences within the group and reducing all group members to a common essence

(Mansbridge, 1999; Young, 2000). Women, for instance, do not all share identical interests and do not think in exactly the same manner (Phillips, 1995). There is more to a woman’s identity than merely being female, which can lead to different interests, experiences, and opinions (Mansbridge, 1999; Young, 2000). However, advocating for women’s representation in politics does not automatically have to imply that one is stripping women of all other layers of their identity. Instead, many advocates merely recognize that women share, to a certain extent, similar experiences that only other members of the group can understand with the same immediacy (Young, 2000).

1.3 The difficult path towards women’s political recruitment

Despite gradual improvements, the world of politics remains heavily dominated by men (RoSa vzw, 2019; UN Women & Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2020). In order to understand the continuous underrepresentation of female politicians, it is necessary to take a closer look at the political recruitment process, as this plays a crucial role in the descriptive representation of women and other marginalized groups in the political sphere (Celis & Meier, 2006; Matland, 2005; Norris, 2006).

The political recruitment process refers to the process that takes individuals from being eligible to take part in the elections to being elected as representatives, and is commonly conceptualised as a four-stage model influenced by demand and supply factors (Devos, 2016; Devroe, 2019; Matland, 2005; Norris, 1997; Norris & Lovenduski, 1993). As illustrated in Figure 1, four phases can be distinguished within the recruitment process: 1) a large number of citizens meet the legal requirements for candidacy and are, consequently, eligible to stand for elected office, 2) a smaller group of eligible citizens aspires to pursue candidacies for elected office, 3) an even smaller number of aspirants are nominated by a party and become official candidates, and eventually 4) only a select number of candidates are actually elected to political office (Celis & Meier, 2006; Devroe, 2019; Matland, 2005).

Figure 1: The political recruitment process. Adapted from Matland, R.E. (2005). Enhancing Women’s Political Participation: Legislative Recruitment and Electoral Systems. In J. Ballington & A. Karam (Eds.), Women in Parliament: Beyond Numbers (p. 94). Stockholm: International IDEA.

Each stage contains certain individual and structural factors that influence the supply of aspirants wanting to pursue elected office, and the demands of the so-called ‘gatekeepers’ (be it voters, party members, political leaders or financial supporters) who (s)elect the party candidates (Celis & Meier, 2006; Norris, 1997). It is these supply and demand factors that greatly affect the descriptive (under)representation of female politicians, with the number of women generally decreasing more rapidly with each transition to a new phase (Devroe, 2019).

1.3.1 Hurdle one: finding the necessary resources and ambition

Although typically the vast majority of citizens are eligible to stand for elected office, not everyone has the desire to pursue a career in politics. Generally, two key factors are required for people to go from simply being eligible to being an aspiring candidate: ambition and resources (Devroe, 2019; Matland, 2005; Norris & Lovenduski, 1995). Already at this stage of the political recruitment process, men appear to have an advantage over women, as male aspirants usually outnumber female aspirants (Matland, 2005). In other words, men seem to be more likely than women to possess the required resources and motivation. There are various underlying factors that can be put forward to contextualise this disparity.

Firstly, men are generally more motivated to enter the world of politics due to ingrained patterns of traditional gender and political socialization (Celis & Meier, 2006; Devroe, 2019; Lawless et al., 2010; Matland, 2005). Indeed, in virtually all cultures, men are socialized to view themselves as legitimate actors in the political sphere, which often results in greater levels of political interest

and ambition than women (Matland, 2005). This can partly be ascribed to traditional sex-role socialization, which perpetuates the notion that women are the primary caretaker of the household and that, therefore, their familial role as a mother outweighs their professional one (Celis & Meier, 2006; Devroe, 2019; Lawless et al., 2010). In addition, women tend to be less politically socialized than men, meaning that they are generally not as familiarised with political values, qualities, knowledge, and characteristics (Celis & Meier, 2006; Lawless et al., 2010). The separation between the public and the private sphere, conservative views on male and female roles in society, and the conceptualization of politics all contribute to this issue (Celis & Meier, 2006). It is not surprising that many women who do decide to go into politics come from politically active households where they were privy to political values and knowledge from a young age (Celis & Meier, 2006; Lawless et al., 2010).

By the same token, men’s traditional position in society also allows for easier access to certain resources that are needed to launch and sustain a career in politics, such as time, money, and experience (Devroe, 2019; Matland, 2005). Especially female politicians often indicate that finding a balance between their familial, political, and, if applicable, other professional responsibilities can be very taxing and time-consuming (Celis & Meier, 2006). Consequently, many women simply do not find the time to become an active and prominent member in the political scene, particularly when they have young children (Celis & Meier, 2006; Devroe, 2019). In addition, women have a quantitatively and qualitatively weaker position on the labour market (e.g. less job security, fewer executive positions held, higher rates of part-time employment, etc.), which can impede financial independence and the acquisition of a valuable professional skillset, both of which are deemed advantageous for a successful career in politics (Celis & Meier, 2006). Nevertheless, women’s mere presence in the labour market can already mitigate some hindering factors, as it allows them to become part of networks and organisations such as trade unions, which can increase their exposure to political discussions and involvement and, subsequently, can help foster their political interest and engagement (Devroe, 2019; Norris & Lovenduski, 1993).

1.3.2 Hurdle two: being selected by the party gatekeepers

Once citizens find the necessary resources and motivation to embark on a career in politics, a second obstacle presents itself: the party gatekeepers (Matland, 2005). This so-called “selectorate” has the decision authority over the selection of candidates (Devos, 2016, p. 204).

The position of the gatekeepers within the party and their exact number depends on the degree of participation and the centralised or decentralised nature of the nomination procedure (Devos, 2016; Matland, 2005). At this stage, yet again, women appear to operate under more challenging circumstances as they generally receive less support from the party elite than their male colleagues (Devroe, 2019; Murray et al., 2012; Vanlangenakker et al., 2013; Wauters et al., 2014).

There are various factors that can either enhance or hamper the selection of female aspirants. A (de)centralised nomination procedure as well as the number of people involved in the selection process can, for instance, influence the number of selected female candidates (Celis & Meier, 2006; Devroe, 2019; Rahat et al., 2008). A centralised selection procedure is sometimes deemed to offer women more opportunities, since it can facilitate the implementation of measures aiming to undermine male political dominance (Celis & Meier, 2006). Furthermore, Rahat, Hazan and Katz (2008) found that a high degree of inclusivity in the nomination procedure can be detrimental to women’s representation.

Another aspect of the nomination procedure that may influence women’s chances is whether the selection system is patronage-oriented or bureaucratic (Matland, 2005). Bureaucratic systems are characterised by clear, detailed, and standardized rules that are dutifully enforced irrespective of who is in power (Matland, 2005). This is in contrast to patronage systems, where loyalty to those in power is expected, and rules are less transparent and often circumvented (Matland, 2005). Bureaucratic selection systems, especially those that have regulations such as quotas in place to ensure women’s representation, are considerably more advantageous to female politicians (Celis & Meier, 2006; Matland, 2005). Nevertheless, it should be noted that it can take a substantial amount of time before the benefits from adopting gender quotas can be reaped (Wauters et al., 2014). In addition, while quotas may facilitate women’s entrance into politics, they do not necessarily promote the longevity of women’s political careers (Vanlangenakker et al., 2013). Be that as it may, having a bureaucratic nomination procedure with clear and open rules does provide female candidates with the opportunity to devise strategies that might allow them to use those rules to their advantage (Matland, 2005).

Moreover, party ideology may also play a significant role in the selection of female aspirants. Right-wing conservative parties are less likely to be concerned with establishing gender parity

within their party, considering that they are more prone to hold on to traditional gender roles and/or they often do not agree with intervening practices such as quotas in favour of underrepresented groups (Celis & Meier, 2006). In contrast, left-wing parties tend to select more women as they generally show greater commitment to promoting the interests of the disadvantaged (Celis & Meier, 2006; Devroe, 2019; Erzeel & Caluwaerts, 2015; Norris, 1997). Additionally, these parties’ voters are often more sensitive to issues of gender inequality, not in the least because a large proportion of them are women (Devroe, 2019; Erzeel & Caluwaerts, 2015; Inglehart & Norris, 2000).

Lastly, the selection criteria employed by party gatekeepers, although seldomly made explicit, often work in favour of male aspirants (Celis & Meier, 2006). One of the most strongly considered criteria among aspirants is their track record in the party and in the constituency (Matland, 2005). Thus, party participation and visibility in the community through, for instance, filling a leadership position in a civil society organisation or holding public office are all very desirable qualities in the eyes of party gatekeepers (Celis & Meier, 2006; Matland, 2005). However, since men are more likely to be incumbents or community leaders, applying such yardsticks often disadvantage female aspirants (Celis & Meier, 2006; Matland, 2005).

1.3.3 Hurdle three: getting elected

Finally, the last hurdle candidates need to jump in order to secure their spot in the political scene is convincing citizens to cast a vote in their favour. Therefore, women’s success rate at this stage largely depends on whether or not female politicians receive fewer votes due to voter bias. Relatively recent studies demonstrated that when certain systemic factors are controlled for (such as list position, campaign expenses, media coverage, incumbency, and party affiliation) voters do not appear to discriminate against female candidates (Black & Erickson, 2003; Devroe, 2019; Wauters et al., 2010). In fact, they may even prefer women over men in such controlled situations (Black & Erickson, 2003; Murray, 2008). These findings seem to point towards systemic bias rather than voter bias as the underlying cause for women’s underrepresentation in politics (Murray, 2008; Wauters et al., 2010).

Nevertheless, voter bias, particularly in the form of gender stereotypes, has been shown to affect citizens’ perception of female politicians, which does have the potential to directly or indirectly

impact women’s opportunities in the political sphere (Alexander & Andersen, 1993; Devroe, 2019; Devroe & Wauters, 2018; Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993; O’Brien, 2015, 2019). As political gender stereotyping constitutes the focus of this master’s thesis, the following section will be entirely dedicated to the nature and consequences of this phenomenon.

2. The issue of political gender stereotypes

2.1 Defining the concept of political gender stereotypes

In order to fully grasp the nature of political gender stereotypes, it is necessary to first briefly consider the meaning of stereotyping and gender stereotyping. Therefore, these two concepts will be explored before elaborating on political gender stereotyping specifically.

2.1.1 Stereotyping

Stereotypes in general can be defined as “beliefs about the characteristics, attributes, and behaviours of members of certain groups” (Hilton & von Hippel, 1996, p. 240). Consequently, stereotyping occurs when people who encounter a member of a certain group assume that that individual shares the characteristics that are stereotypically associated with that group (Dolan, 2014a; Fiske & Neuberg, 1990). This category-based impression formation constitutes the essence of stereotyping (Devroe, 2019).

Stereotypic thinking can serve a variety of purposes reflecting a range of motivational and cognitive processes (Hilton & von Hippel, 1996). A common explanation for the occurrence of stereotyping is, for instance, that it can facilitate information processing by allowing the perceiver to turn to previously stored knowledge rather than having to assimilate new information (Berinsky & Mendelberg, 2005; Dolan, 2014a; Hilton & von Hippel, 1996). The use of stereotypes can also be incited by environmental factors, such as group conflicts, social roles, and differences in power, or they can be employed to justify the status quo (Hilton & von Hippel, 1996). Therefore, the exact function of stereotyping is dependent on the context in which it takes place (Bauer, 2018; Hilton & von Hippel, 1996).

Any form of stereotyping, whether it is centred around gender, ethnicity, age, or any other characteristic, can be quite problematic as it commonly overgeneralises the identity of a (sub)group and can conjure up resistance to accept information that challenges the stereotype (Devroe, 2019; Hilton & von Hippel, 1996).

2.1.2 Gender stereotyping

Gender stereotypes pertain to “beliefs about what women and men are like, what abilities they possess, and what behaviours and activities are appropriate for each” (Dolan, 2014a, p. 22). Gender stereotypes are believed to be among the most persistent and pervasive stereotypes held by people, partly because gender is a very salient feature that is easily and quickly discerned upon seeing someone or even simply upon reading or hearing someone’s name (Devroe, 2019; Dolan, 2014a). Moreover, a person’s sex is a socially relevant category that plays a central role in various aspects of life, which is thought to give particular power to stereotypical beliefs about men and women (Dolan, 2014a).

Gender stereotyping results in the attribution of distinctive and often opposing characteristics to men and women. Feminine stereotypes characterise women as being kind, warm, passive, nurturing, caregiving, emotional, compassionate, gentle, loyal, and moral, whereas masculine stereotypes portray men as being aggressive, tough, assertive, decisive, ambitious, analytical, competitive, independent, controlling, rational, and a good leader (Alexander & Andersen, 1993; Bauer, 2018; Devroe, 2019; Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993).

These different attributes are often summarized into two dimensions: the communal and the agentic dimension (Bauer, 2018; Devroe, 2019; Eagly, 1987). The communal dimension is commonly associated with women, as it emphasizes a concern for the welfare of others, which is believed to manifest itself more strongly in women (Devroe, 2019; Eagly, 1987). Conversely, men are typically associated with the agentic dimension because it embodies a controlling and assertive tendency that is thought to be displayed most strongly by men (Devroe, 2019; Eagly, 1987).

Social psychologists have put forward different theories to explain the origin and content of gender stereotypes (Dolan, 2014a). Eagly (1987) considers the division of labour between the

sexes as the wellspring of stereotypes about the traits and abilities of men and women. Without elaborating on the underlying cause(s) of the gendered division of labour, she posits that it shapes gender roles in such a way that men are expected to behave agentically and women communally. In other words, the assignment of a disproportionate share of domestic work to women and the tendency for women and men to carry out different forms of paid employment leads to distinctive gender role expectations and stereotypes (Celis & Meier, 2006; Devroe, 2019; Eagly, 1987). Other work emphasizes the status differences that are derived from the different gender roles, which can cause women to be assigned lower levels of social status than men (Dolan, 2014a; Wood & Karten, 1986). Lastly, differences in power can also constitute a basis for gender stereotypes (Dolan, 2014a). In short, women’s and men’s different positions in the world can translate into stereotypical beliefs about both sexes (Dolan, 2014a).

2.1.3 Political gender stereotyping

Political gender stereotyping can be defined as “the gender-based ascription of different traits, behaviours, or political beliefs to male and female politicians” (Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993, p. 120). Thus, political gender stereotypes are gender stereotypes that are applied to and can affect the political scene (Devroe, 2019; Dolan, 2014a; Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993). Voters have been shown to rely on heuristics such as gender when evaluating political candidates, as they often do not possess the necessary time, resources or motivation to thoroughly inform themselves about every competing candidate (Devroe & Wauters, 2018; Dolan, 2014a; Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993). This provides voters with a mental shortcut, allowing them to extend prior beliefs about group members to individuals (Dolan, 2014a; Hilton & von Hippel, 1996). Considering the stereotypical notion that women are communal and men are agentic (see supra section 2.1.2), this can create different expectations for and evaluations of male and female politicians (Devroe, 2019; Dolan, 2014a).

2.1.3.1 Gender-trait or issue competence stereotypes

Following Huddy and Terkildsen’s (1993) influential work, two different varieties of political gender stereotypes are oftentimes distinguished from one another: those centred around traits and those centred around beliefs (Devroe, 2019; Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993). The so-called “trait approach” posits that voters have gender-linked assumptions about a candidate’s personality traits, and that these beliefs create the expectation that women and men have different areas of issue expertise

(Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993, p. 121). According to this approach, female politicians would, for instance, be considered more competent to tackle health care issues rather than military matters (Devroe, 2019; Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993).

Such stereotypical views could affect women’s opportunities in the political sphere, both in terms of the type of positions they are able to secure and in terms of the number of votes they are able to gain, considering that perceived competency has been found to be a central criterion in voters’ evaluation of political candidates (Audrey et al., 2010; Devroe & Wauters, 2018).

In accordance with Devroe’s (2019) research, the trait approach will be further referred to as ‘issue competence stereotypes’.

2.1.3.2 Gender-belief or ideological position stereotypes

The “belief approach” is the second type of political gender stereotyping identified by Huddy & Terkildsen (1993, p. 121). It postulates that voters expect women to be more liberal (in the American sense of the word) and Democratic than men (Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993, p. 121). Translated to a European context, this approach implies that women would be considered more leftist (Devroe, 2019). Therefore, these gender-belief stereotypes will be further referred to as ‘ideological position stereotypes’, following Devroe’s (2019) example.

The underlying logic behind the belief approach is that due to gender-trait stereotypes (see supra section 2.1.3.1) women are believed to be better suited to deal with compassion or communal issues, which are, in turn, typically considered to be best handled by left-wing parties as a result of party stereotypes (Devroe, 2019; Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993; Winter, 2010). Thus, Huddy and Terkildsen’s (1993) reasoning suggests that despite being differentiated from one another, issue competence and ideological position stereotypes are nevertheless interconnected. In addition, it also implies an overlap between feminine stereotypes and stereotypes about left-wing parties (Bauer, 2018; Dolan, 2014a; Winter, 2010).

Furthermore, ideological position stereotypes can also be linked to a generally higher share of female politicians among left-wing parties compared to right-wing parties, which especially holds true in majoritarian electoral systems such as that of the USA, where the majority of research on

political gender stereotyping has been conducted (Celis & Meier, 2006; Devroe, 2019). As previously mentioned (see supra section 1.3.2), leftist parties tend to select more female candidates since they are generally more committed to promoting women’s interests, not in the least because their voters are typically more sensitive to issues of (gender) inequality (Celis & Meier, 2006; Devroe, 2019; Erzeel & Caluwaerts, 2015).

2.1.3.3 A quick glance at research on the prevalence of political gender stereotypes The existence of political gender stereotyping among voters has been extensively researched in the United States (Alexander & Andersen, 1993; Bauer, 2015, 2018; Dolan, 2014a, 2014b; Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993; Winter, 2010). Broadly, this large body of work suggests that voters do, in fact, tend to hold stereotypical views on male and female political candidates. Voters have been found to ascribe more stereotypical ‘womanly’ traits to female politicians and more stereotypical ‘manly’ traits to male politicians (Alexander & Andersen, 1993; Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993; Kahn, 1996; Lawless, 2004; Leeper, 1991; Sapiro, 1981a), although Schneider & Bos (2014) refute this idea and propound that female politicians are a subtype of women, similar to female professionals, and, consequently, constitute their own stereotypical category. In addition, several findings have pointed towards the presence of issue competence stereotypes in voters’ evaluations of political candidates, with women typically being deemed more competent to tackle communal issues such as childcare, health care, and education, and men being considered better equipped to deal with agentic matters such as military, trade, agriculture, and taxes (Alexander & Andersen, 1993; Dolan, 2010, 2014a; Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993; Sapiro, 1981a). Furthermore, several studies on ideological position stereotypes found that female candidates tend to be viewed as more liberal (in the American sense of the word) (Alexander & Andersen, 1993; Dolan, 2014a; Huddy & Terkildsen, 1993; Koch, 2000, 2002; M. L. McDermott, 1997; Mcdermott, 1998; Schneider & Bos, 2016).

While ample research in the USA has affirmed the notion that political gender stereotypes are present among voters and have the potential to influence their assessments of male and female politicians, research conducted outside of the American context has been comparatively much scarcer (Devroe, 2019). Nevertheless, the relatively limited studies that have been carried out in different contexts generally do appear to confirm the existence and potential impact of political gender stereotypes outside of the United States. For instance, despite the country’s progressive

political culture, Matland’s (1994) study in Norway yielded results in support of issue competence stereotypes, as politicians were deemed more qualified to handle certain policy areas based on their gender. Herrick and Sapieva’s (1998) findings demonstrated an even stronger impact of issue competence stereotypes on voters’ evaluations of candidates in Kazakhstan, where female politicians were found to be perceived as less competent in virtually every policy area taken into consideration. A more recent, comparative study performed by Yarkoney-Sorek, Geva and Taylor-Robinson (2016) in Costa Rica and Israel indicated rather gender-neutral attitudes in Costa Rica and gender-biased attitudes in Israel. Female politicians’ abilities in Costa Rica were not deemed to be inferior to those of male politicians. In fact, women were rated more favourably when statistically significant differences between both genders were observed. Conversely, female politicians in Israel were evaluated less favourably than their male counterparts.

Especially relevant to the focus of this master’s thesis are Devroe and Wauters’ (2018) findings from Flanders (Belgium), which demonstrated rather minor differences in perceived issue competence between Flemish male and female candidates but large differences in perceived ideology. Indeed, Flemish female politicians were deemed to be more leftist than their male colleagues for virtually all policy domains that were taken into consideration. These results indicate that issue competence and ideological position stereotypes are not necessarily interconnected packages and can occur independently from one another (Devroe & Wauters, 2018).

Notwithstanding the aforementioned studies and findings, the impact of political gender stereotypes should be approached with the necessary nuance. Recent scholarship has established that the link between a candidate’s gender and the subsequent activation of political gender stereotypes and biased voter perceptions might not be as straightforward as it may appear at first glance (Bauer, 2015, 2018; Brooks, 2011, 2013; Dolan, 2014a). Indeed, the degree of stereotype reliance has been shown to not be uniform across all individuals, which suggests that (political gender) stereotyping might not be as automatic and embedded as one may assume (Bauer, 2015; Dolan, 2014a). This could potentially neutralise the impact of political gender stereotypes in the political scene, as the actions of those who hold heavily gender-biased beliefs may be counterbalanced by the actions of individuals who do not hold such beliefs (Dolan, 2014a).

Moreover, the lack of uniformity in stereotype reliance among individuals also implies that political gender stereotyping is a contextually dependent process with various factors affecting how and whether individuals use stereotypical views to form judgements (Bauer, 2018; Dolan, 2014a). For instance, the presence of individuating information about a candidate’s personal background and policy positions has been shown to affect the degree to which voters rely on political gender stereotypes, and can in some cases even dissipate their impact (Alexander & Andersen, 1993; Bauer, 2015, 2018; Brooks, 2013; Carnes & Lupu, 2016; Devroe, 2019; Dolan, 2014a; Fiske & Neuberg, 1990; Pedersen et al., 2019; Sapiro, 1981b). In addition, the effect of political gender stereotypes on voters’ evaluations of politicians has also been linked to several environmental factors, such as the level of terrorism threat (Holman et al., 2016; Lawless, 2004) and the way in which candidates are portrayed in the media (Brooks, 2011; Dolan, 2014a; Kahn, 1996). Lastly, voter characteristics such as a voter’s gender, age, and political orientation have also been argued to influence stereotype reliance (Bauer, 2015; Devroe, 2020; Erzeel & Caluwaerts, 2015). Consequently, it is important to keep these contextual factors in mind when researching political gender stereotypes (Devroe, 2019; Dolan, 2014a).

2.2 Factors influencing the impact of political gender stereotypes

As was gathered from the research overview presented in section 2.1.3.3 above, the question of whether and to what extent voters may rely on gender-biased beliefs when evaluating politicians depends on various contextual factors. Since it is important to take these factors into consideration when examining political gender stereotyping, several such contextual elements that are relevant to this study will be discussed in the following sections.

2.2.1 The electoral system

It has often been argued that political gender stereotype reliance is more likely to occur in plurality or majority systems compared to proportional representation (PR) systems because the latter generally creates a more fruitful environment for female politicians (Celis & Meier, 2006; Devroe, 2019; Matland, 2005; Yarkoney-Sorek et al., 2016). It is well established that PR systems can facilitate the nomination of female candidates. PR systems with sizeable district magnitudes and higher electoral thresholds, in particular, are believed to increase women’s chances to thrive in the world of politics, as these features imply that a party can expect to win several seats in a district and, therefore, will be more encouraged to “balance its ticket” (Matland, 2005, p. 101). Indeed,

establishing a balance between male and female candidates can allow parties to attract a larger voter audience and can prevent internal party conflicts (Matland, 2005). Consequently, the greater gender balance among competing candidates typically leads to a higher share of elected women and can also result in a more balanced representation across parties compared to plurality or majority systems (Devroe, 2019; Matland, 2005).

Subsequently, this higher number of elected female politicians and the generally more equal distribution of women across different parties can indirectly affect the degree to which voters hold and apply political gender stereotypes (Devroe, 2019). A larger share of women in (top) political positions increases citizens’ exposure to gender-equal information (Devroe, 2019). Based on exposure theory (see infra section 2.2.3.2), this can stimulate voters to adopt more gender-neutral attitudes towards women in politics (Devroe, 2019; Jennings, 2006). In addition, a fairly even distribution of women among different parties as opposed to an overconcentration of them in left-wing parties, which is quite common in majority systems (e.g. USA), makes it less likely that voters will hold ideological position stereotypes about female politicians (Devroe, 2019).

However, it should be noted that while PR systems do create more favourable conditions for female candidates, a PR system on its own is clearly not enough to create gender parity in the political sphere (Yarkoney-Sorek et al., 2016). After all, this type of electoral system predates the nomination and election of notable numbers of women (Yarkoney-Sorek et al., 2016). Moreover, PR elections for congress or parliament are not necessarily strongly correlated with women’s representation in party leadership or other top-level posts (Yarkoney-Sorek et al., 2016). The case could be made that parties appear to be encouraged to nominate more women for legislature, as this can work in their favour, but that they are more hesitant to allow women into the inner circles of power (Yarkoney-Sorek et al., 2016).

2.2.2 Individual characteristics of the candidate

2.2.2.1 Physical appearanceThe physical appearance of a political candidate, particularly his or her facial features, has been shown to affect voters’ perception of that candidate as well as voting behaviour (Chiao et al., 2008; Lammers et al., 2009). Lammers et al (2009), for instance, found that the prototypicality, or lack thereof, of a presidential candidate’s looks influences issue competence stereotyping. Voters