THE

DETERMINANTS

OF

CASH

HOLDINGS: EVIDENCE FROM EU

FIRMS

Word count: 22,145Enak Segers

Student number: 01607180Lars Ampoorter

Student number: 01600234Supervisor: Prof. dr. Rudy Aernoudt

Master’s Dissertation submitted to obtain the degree of:

Master of Science in Business Economics

THE

DETERMINANTS

OF

CASH

HOLDINGS: EVIDENCE FROM EU

FIRMS

Word count: 22,145Enak Segers

Student number: 01607180Lars Ampoorter

Student number: 01600234Supervisor: Prof. dr. Rudy Aernoudt

Master’s Dissertation submitted to obtain the degree of:

Master of Science in Business Economics

1

Preamble

Over the duration of the thesis, several complications surfaced. We argue that stiff communication, due to the coronavirus, was one of the most prominent problems. When writing a duo-thesis, it is necessary to maintain good communication. Given the quarantine measures, however, we were not able to physically work together. In contrast, video calling and working on different screens was the new normal, which led to numerous misinterpretations and misunderstandings and, in general, a considerable loss in efficiency. Moreover, these measures also implied a stiff communication with our promotor. In fact, we experienced that receiving physical feedback, rather than feedback via mail, is way more valuable. Lastly, regarding the qualitative study, we noted that several companies were not available for working together since they had to use all their resources to reduce the negative impact of the coronavirus. However, the coronavirus was not the only thing that caused us setbacks. For instance, we made several learning mistakes in all aspect of the assignment, that inevitably led to some loss of time, given that this was our first real thesis. Moreover, due to the limited time frame of our main data source Orbis, we had to reduce the scope of our study to 2010-2018. In addition, we eventually decreased the scope to 2013-2018 since we had to use 2010, 2011 and 2012 as a reference for the variable business risk.

2

Permission

We declare that the content of this Master’s Dissertation may be consulted and/or reproduced, provided that the source is referenced.

3

Foreword

First of all we would like to thank our thesis promotor, Rudy Aernoudt, of the Faculty of Business Administration and Economics at the University of Ghent. During the development of our master’s dissertation, we were able to reach out to professor Aernoudt when necessary. He provided us with very insightful comments regarding the topic cash holdings. We also want to thank our parents, due to their emotional and financial support we had the best four years of our life.

4

Table of contents

Preamble ... 1 Permission ... 2 Foreword ... 3 Abbreviations ... 6Figures and tables ... 7

1. Introduction ... 8

2. Literature review ... 11

2.1. Motives of cash holdings ... 11

2.2. Firm-specific determinants... 12

2.2.1. Trade-off theory ... 12

2.2.2. Pecking-order theory ... 15

2.2.3. The free cashflow theory ... 16

2.3. Country-specific determinants ... 18

2.3.1. Investor protection & Legal environment ... 18

2.3.2. National culture ... 21

2.3.3. Ownership and control ... 23

2.4. Hypotheses development ... 24

3. Data ... 30

3.1. Sampling ... 30

3.2. Variables ... 32

3.2.1. Dependent variable ... 32

3.2.2. Independent firm-specific variables ... 32

3.2.3. Independent country-specific variables ... 34

3.2.4. Control variables ... 37

3.3. Summary of the measurements ... 38

3.4. Descriptive statistics ... 39 3.4.1. Cash holdings ... 39 3.4.2. Independent variables ... 40 3.4.3. Industry... 43 4. Empirical results ... 44 4.1. Methodology ... 44

4.1.1. Pooled OLS Regression ... 44

5

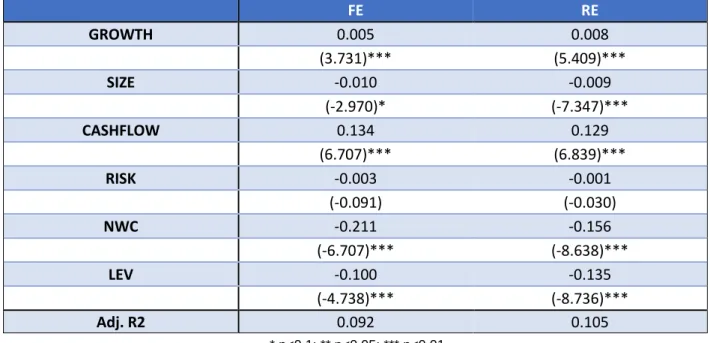

4.1.3. Fixed-effects and random-effects model ... 46

4.1.4. Assumptions tests ... 47

4.2. Firm-specific determinants results ... 48

4.2.1. Pooled OLS regression ... 48

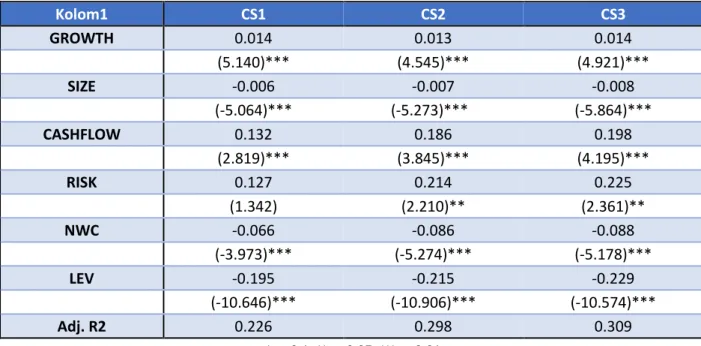

4.2.2. Cross-sectional regression using means ... 51

4.2.3. Fixed-effects and Random-effects model ... 52

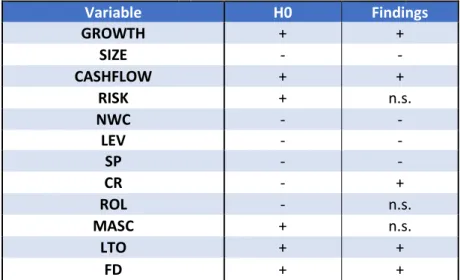

4.2.4. Summary of the results of the different models of the different models ... 53

4.3. Firm-specific and country-specific determinants results ... 55

4.4. Controlling the results for financial development ... 59

4.5. Economic relevance... 63

5. Qualitative research ... 65

5.1. Company and Industry overview... 65

5.2. Results ... 66

6. Conclusion ... 70

7. Limitations ... 73

Bibliography ... x

Attachments ... xiv

Attachment 1: Calculation of cashflow magnitude ... xiv

Attachment 2: The factors and sub-factors of the WJP rule of law index (1/2) ... xv

Attachment 2: The factors and sub-factors of the WJP rule of law index (2/2) ... xvi

Attachment 3: Cash holdings descriptives per country ... xvii

Attachment 4: Summary statistics of the FD index ... xviii

Attachment 5: Descriptives of the independent variables per country ... xix

Attachment 6: Correlation matrix (SPSS) ... xx

Attachment 7: Variance inflation factors (VIFs) (SPSS) ... xxi

Attachment 8: Breusch-Pagan test (heteroskedasticity test) (R) ... xxi

Attachment 9: Durbin-Watson test (autocorrelation test) (SPSS) ... xxii

Attachment 10: Hausman test (R) ... xxii

6

Abbreviations

CASH Cash holdings

CR Creditor rights

CS Cross-sectional

D-W Durbin-Watson

ECB European Central Bank

EMU European and Monetary Union

EU European Union

FCFT The free cashflow theory

FD(I) Financial development (index)

FE Fixed-effects

GROWTH Growth opportunity set

IMF International Monetary Fund

LEV Leverage

LTO Long-term orientation

MAS Masculinity

MBT Market-to-book ratio

NACE Nomenclature of Economic Activities

NPV Net present value

NWC Net working capital

OLS Ordinary Least Squares

PLC Public listed company

RE Random-effects

RISK Business risk

ROL Rule of law

RP Reorganization proceedings index

SIZE Firm size

SP Shareholder protection

VIF Variance inflation factor

WJP World Justice Project

7

Figures and tables

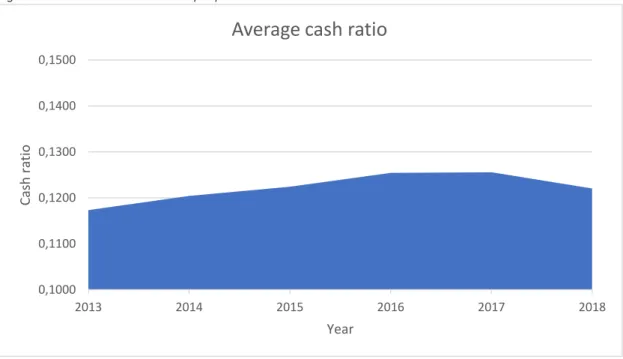

Figure 1: Cash ratio over the sample period ..………. 32

Table 1: overview firm-specific hypotheses from the different theoretical models ... 24

Table 2: Overview findings firm-specific determinants on cash holdings ... 24

Table 3: Overview findings country-specific determinants on cash holdings ... 29

Table 4: Industry classifications ... 31

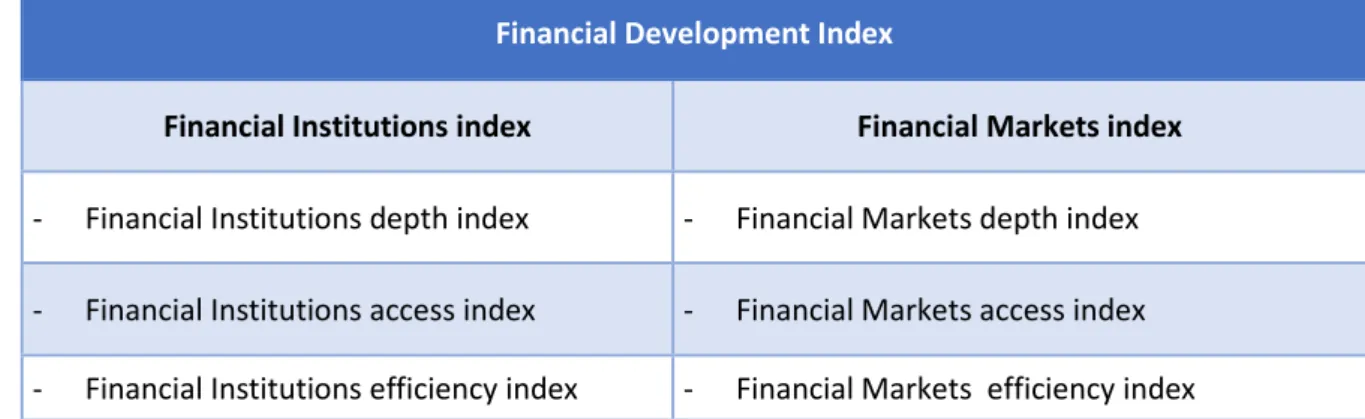

Table 5: Financial Development Index ... 37

Table 6: Summary of measurements ... 38

Table 7: Descriptives of the dependent and independent variables ... 42

Table 8: Descriptives of cash holdings per industry ... 43

Table 9: Results of the OLS regression models for firm-specific determinants ... 50

Table 10: Results of the cross-sectional regression models for firm-specific determinants ... 51

Table 11: Results of the fixed- and random-effects models for firm-specific determinants ... 52

Table 12: Overview of the results of the regression analysis models for firm-specific determinants . 54 Table 13: Overview of the results of the regression analysis models for firm-specific determinants and country-specific determinants ... 58

Table 14: Overview of the results of the regression analysis models for firm-specific determinants and country-specific determinants, while controlling for FD ... 61

Table 15: Overview of the hypotheses and the results ... 62

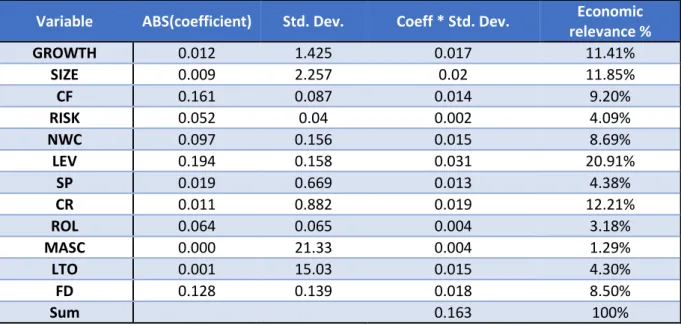

Table 16: Pooled OLS regression (OLS3) economic relevance ... 64

Table 17: Cross-sectional regression (CS2) economic relevance ... 64

Table 18: Fixed-effects model (FE) economic relevance ... 64

Table 19: descriptives of the NACE Rev 2 code 2120, Lundbeck and UCB ... 66

Table 20: overview of the hypotheses, quantitative and qualitative results ... 69

Table 21: Calculation of cashflow magnitude ... xiv

Table 22: The factors and sub-factors of the WJP rule of law index ... xv

Table 23: Cash holdings descriptives per country ... xvii

Table 24: Summary statistics of the FD Index ... xviii

Table 25: Descriptives of the independent variables per country ... xix

Table 26: Correlation Matrix ... xx

Table 27: Variance Inflation Factors ... xxi

Table 28: Breusch-Pagan test ... xxi

Table 29: Durbin-Watson test ... xxii

Table 30: Hausman Test ... xxii

8

1. Introduction

He that cannot pay, let him pray. Although this English proverb is 400 years old, it still carries a valuable message given that many firms fail due to illiquidity and cashflow problems in particular. Consequently, one may argue that sufficient cash holdings are a fundamental aspect of a firm’s day-to-day activities and a key factor in developing a long-term sustainable business. Moreover, academic literature regarding firms’ cash holdings points out that, over the course of time, companies hold significantly more cash, which highlights the increasing importance of the notion cash holdings. For instance, Bates, Kahle & Stulz. (2009) report that the cash holdings of US firms doubled over a period from 1980 to 2006, i.e. by 10,5% to 23,2%. Moreover, the ECB claims that, in previous years, non-financial companies significantly increased their cash holdings. In addition, they state that “in order to properly assess this development, which has been relatively widespread across sectors, the underlying forces explaining this increase need to be examined” (ECB, monthly bulletin rapport march 2008, p. 50). Subsequently, the following question emerged among scholars: ‘Why do companies hold cash?’. This question still intrigues scholars, since certain questions remain unanswered, which in turn leads to different streams of thought. Furthermore, this topic may also be perceived as contestable, since in a world with perfect capital markets, firms would not have the urge to hold cash, as companies would be able to effortlessly raise external capital in order to finance new projects. However, this does not reflect the reality, as financial markets are characterized by financial frictions, information asymmetry and transaction costs. Consequently, scholars attempt to determine the different factors that justify the considerable amount of cash held by companies.

There are three theoretical models that facilitate researchers in investigating the firm-specific factors that have an impact on cash holdings. According to the first theory, the trade-off theory, companies ascertain their optimal level of cash by simply balancing the benefits and costs of holding cash. Benefits, such as lower financial distress and lower costs of raising external finance are weighed against the main disadvantage, the opportunity costs, considering that the return on liquid assets is lower compared to the foregone investment opportunities (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004). Second, the pecking-order theory is based on the notion that asymmetric information exists between managers and outside investors. In order to minimize the information asymmetry costs, firms should finance their projects with internal resources first, followed by debt and, if necessary, they can issue equity (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004; Myers & Maljuf, 1984). This is also referred to as the hierarchy of financing sources. Moreover, the pecking-order theory argues that companies do not have an optimal level of cash, since cash functions merely as a buffer between firms’ retained earnings and their investment needs. Finally, the free cashflow theory is grounded on the notion that certain firms hold more cash than necessary, which increases corporate managers’ discretionary power regarding firms’ investment

9 policy (Jensen, 1986). Subsequently, excessive cash can incite corporate managers in pursuing growth opportunities, even when NPV is negative, which may cause erosion of shareholder value. The aforementioned three theoretical models propose certain indicators that might explain a company’s decision to hold more or less cash.

The majority of studies concerning this subject are conducted on United States firms e.g. (Bates et al., 2009; D’Mello, Krishnaswami & Larkin, 2008; Han & Qui, 2007; Harford, Mansi & Maxwell, 2008; Kim, Mauer & Sherman, 1998; Opler, Pinkowitz, Stulz & Williamson, 1999). Moreover, the conducted studies in the US find little support that the free cashflow theory, i.e. the agency theory, is an explanation for holding cash. However, Dittmar & Smith (2003) argue that since the United States is a common law country, shareholders are well protected and can enforce managers to return excess cash to shareholders. Hence, in a country such as the United States, the variation in agency costs is too low to establish a significant impact on cash holdings (Hilgen, 2015). Subsequently, weak evidence related to agency cost theory prompted researchers to use international data samples. Moreover, Dittmar et al. (2003) can be considered a pioneer in the study of the determinants of a company's cash holdings across different countries. Dittmar et al. (2003) compiled an international sample of approximately 11.000 firms from 45 countries around the world and find evidence that companies in countries with poor shareholder protection hold up to twice as much cash than companies in a well-protected shareholder environment. Consequently, their empirical evidence is consistent with “the conjecture that investors in countries with poor shareholder protection cannot force managers to disgorge excessive cash balances” (Dittmar et al., 2003, p.111). Note that the coverage of literature with regard to this topic is still relatively scarce, however, there are certain prominent papers that further examine the determinants of firms’ cash holdings across different nations e.g. (Ozkan & Ozkan, 2004; Guney, Ozkan & Ozkan, 2007, Pinkowitz & Williamson, 2001; Ferreira & Vilela, 2004). For instance, Ozkan & Ozkan (2004) conducted a study based on non-financial UK firms, Guney et al. (2007) carried out a study based on French, German, Japan and UK firms. Moreover, Ferreira & Vilela conducted a study on publicly listed firms in the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU).

It should be noted that the sample period of Ferreira & Vilela’s paper (2004) ranges from 1987 to 2000, therefore preceding the establishment of the European Union. Furthermore, apart from the study of Ferreira & Vilela (2004), we find few quality publications that study the cash holdings of European firms. Since this master’s dissertation examines a sample from 2013 to 2018 and takes in to account the EU countries, it can be considered as a valuable contribution to the extant literature. In addition, this paper focusses mainly on the following firm-specific determinants, which are proven to be significan: growth opportunity set, leverage, firm size, net working capital (NWC), cashflow magnitude and business risk. Next, we complement our study with country-specific determinants. First, we include shareholder protection, creditor protection and rule of law to use as a proxy for legal

10 environment and investor protection. Second, we investigate whether different cultural values across various countries can explain corporate managers’ cash holding behavior. Given that, Chang & Noorbakhsh (pg. 324, 2009) argue that “Dittmar et al. (2003) and other researchers who used ratings of corporate governance systems as proxy variables to support agency theory did not consider the fact

that investors may develop different perceptions of agency relationship across dissimilar cultures”. The remainder of this master’s dissertation is structured as follows: In section 2 we discuss the

different theories and formulate our hypotheses accordingly. In section 3 we discuss our sample and data. In section 4 we discuss the methodology and present our regression results. In section 5 we conduct a concise qualitative research. In section 6, the conclusion, we formulate an answer to our research question: Why do listed companies hold cash?. Finally, we discuss the limitations of this master’s dissertation.

11

2. Literature review

In this literature review, the extant literature about cash holdings is discussed. We start by examining the main motives of firms to hold cash and the accompanied advantages and disadvantages. Subsequently, we address the different components that constitute cash holdings by means of three theoretical models, namely the pecking-order theory, trade-off theory and free cashflow theory. It can be argued that these theories perceive the impact of some firm specific determinants on cash holdings in a different way. Next, we discuss the impact of country-specific determinants on cash holdings. This subsection is divided in two groups. First, we examine the impact of the investor protection and legal environment, which consists of shareholder protection, creditor rights, rule of law and ownership & control (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004). Second, we investigate whether different cultural values across various countries can explain corporate managers’ cash holding behavior. Finally, we develop our hypotheses regarding the aforementioned topics based on the distinctive predictions made by the three theoretical models and the extant academic findings.

2.1. Motives of cash holdings

Cash holdings are a vital component in corporations’ financial policy. It ensures that companies can pay their obligations, short term liabilities and execute their daily operations (Hilgen, 2015). The majority of extant literature defines cash holdings as cash and cash equivalents (Opler et al., 1999). Cash equivalents, e.g. marketable securities, can be easily converted into cash and are therefore perceived as highly liquid assets. In a perfect world with efficient financial markets, firms would not have the urge to hold sufficient amounts of liquid assets, as companies would be able to effortlessly raise external capital. However, this is not the case in reality due to the fact that financial frictions, transaction costs and information asymmetry occur on financial markets, which in turn motivated scholars to identify the different factors that justify the considerable amount of cash held by companies. Consequently, there are some theories that attempt to explain the differences in cash holdings across companies. Ozkan & Ozkan (2004) point out that the transaction cost and precautionary motive are the two most widely used motives for cash holdings. Keynes (1936, p.177) defines the transaction costs motive as “the need for cash for the current transactions of personal and business exchanges”. Moreover, Opler et al. (1999) argue the transaction costs motive is based on the assumption that there are fixed and variable costs associated with raising external finance. More specifically, firms that are expected to incur large fixed transaction costs when raising external capital, accumulate more cash in the form of a buffer (Opler et al., 1999). Furthermore, the precautionary motive emphasizes the costs that emerge from agency problems, information asymmetry and

12 foregone investments, i.e. opportunity costs. (Ozkan & Ozkan, 2004). Therefore, companies are encouraged to keep (more) cash, so that they have sufficient funds when external financing is not available or too costly due to the aforementioned costs.

2.2. Firm-specific determinants

Based on the previously mentioned motives, Hilgen (2015) points out that one can derive three main categories with separate fundamental theoretical assumptions regarding the cash holdings of a firm. The first category embodies transaction costs, the second category copes with information asymmetry and agency cost of debt, the last category addresses agency problems between managers and their shareholder. In existing academic literature, authors define the aforementioned categories by means of different theoretical models. For example, Ferreira & Vilela (2004) define the three categories utilizing the following distinct theoretical theories: trade-off theory, pecking-order theory and the free cashflow theory. In comparison, Opler et al. (1999) theoretical section is based on the subsequent components: transaction cost model, the financing theory, agency costs and information asymmetry. In addition, Ozkan & Ozkan (2004) use also different categorizations in their theoretical section. “Thus, it can be argued that the lack of a clear taxonomy with regard to the theories hampers the comparison of the results found by several authors.” (Hilgen, 2015, p. 5).

We prefer the three theoretical models suggested by Ferreira & Vilela (2004). It allows us to make a structured and comprehensive overview concerning the distinctive predictions made by the different theories and therefore helps us in formulating our hypotheses.

2.2.1. Trade-off theory

The trade-off theory argues that maximization of shareholders wealth is the main task of a corporation manager. In doing so, firms must determine their optimal cash position by balancing the marginal benefits with the marginal costs of holding cash (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004; Opler et al., 1999). In this subsection, we discuss the advantages that result from holding cash, followed by the disadvantages, according to this theory. First, cash reduces the probability of financial distress and bankruptcy, since cash buffers may offer security when facing (unexpected) contingencies. Next, cash holdings allow firms to pursue their investment policy, even when they are financially constrained. Consequently, corporations do not have to relinquish profitable investment opportunities, when financially constraint (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004). Lastly, firms hold a cash buffer to minimize the costs of raising funds, since Opler et al. (1999) point out that both the liquidation of assets and the acquiring of external capital are costly. Consequently, cash can be perceived as a cushion between firms’ internal

13 resources and the use of external financing. In contrast, the main disadvantage is the opportunity cost. Miller & Orr (1966) portray this problem as a trade-off between the cost of insufficient cash and lower interest returns. This is due to the fact that the return on liquid assets is lower compared to the foregone investment opportunities. The firm-specific determinants, identified by the trade-off theory, will be reviewed below.

(i) Growth opportunity set

Due to costly external financing, firms with a lack of internal funds might be forced to forego certain profitable opportunities (Hilgen, 2015). Hence, one may expect that firms hold sufficient internal funds to prevent them from missing out on these valuable growth opportunities. Consequently, high-growth firms hold more cash since the costs of running out of internal funds is greater for them (Opler et al., 1999; Ozkan & Ozkan, 2004). Furthermore, academic literature points out that when companies face financial distress, the intangible assets on the balance sheet (e.g. investment opportunities) perish (Kim et al., 2011). Hence, companies with high growth opportunities will hold more cash to avert financial distress and to pursue valuable growth opportunities when they present themselves.

(ii) Business risk

According to Ozkan & Ozkan (2004), corporations with high cashflow volatility are more likely to endure cash deficits when facing unforeseen cashflow downturns. In addition, Minton & Schrand (1999) indicate that firms that experience these cash deficits ultimately forego profitable investment opportunities. In order to prevent financial distress and refraining from investments, companies with high cashflow variability need to maintain a larger cash buffer. Hence, one can expect a positive relation between cash holdings and cashflow variability.

(iii) Size

According to the Millar & Orr model (1966) large corporations encounter economies of scale regarding cash management. Consequently, large firms will hold less cash compared to smaller firms. Furthermore, it is believed that large firms are, in general, more diversified. This may result in a lower likelihood of financial distress and bankruptcy (Rajan & Zingales, 1995). Moreover, it is also argued that raising external funds is easier and cheaper for large companies, due to less information asymmetry, lower costs of raising external capital and more accessible capital markets (Fazzari & Petersen, 1993; Kim et al., 1998). Thus, in line with the trade-off theory, one may expect a negative relation with cash holdings

14 (iv) Cashflow magnitude

Kim et al. (1998, p.348) argue that “cashflows can be perceived as substitutes for cash, as they provide a ready financial source to meet operating expenditures and maturing liabilities.” Hence, companies with high cashflow can afford to hold less cash. Consequently, one may expect a negative relation between cashflows and cash holdings.

(v) Net working capital

Net working capital can be considered as a substitute for cash and cash equivalents. This is due to the fact that net working capital is perceived as highly liquid and thus can easily be converted into cash (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004). In addition, Ozkan & Ozkan (2004) point out that non-cash liquid assets can be converted more easily and cheaper than other assets. For instance, a firm, in need of cash, can easily liquidate their accounts receivable thru factoring or securization (Opler et al., 1999). Hence, one can expect a negative relationship between net working capital and cash holdings.

(vi) Leverage

Ferreira & Vilela (2004, p.299) point out that leverage enhances the likelihood of bankruptcy due to the pressure that rigid amortization plans put on the firm treasury management. In addition, Han & Qiu (2007) suggest that high levered firms accumulate more cash in order to pay its obligations (e.g. future debt payments). Thus, in line with the trade-off theory, high levered companies hoard cash with the aim of reducing the likelihood of financial distress. In contrast, the degree to which companies are levered indicate how easily firms can raise external funds (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004). Consequently, high levered firms might effortlessly raise external capital, which encourages them in holding less cash. Hence, the predictions concerning the relation between leverage and cash holdings are ambiguous (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004).

(vii) Dividend payments

We do not include this firm-specific determinant in our research due to insufficient and incorrect data. However, we believe that including the variable dividend payment in our literature review gives a more comprehensive view of the notion cash holdings. According to academic literature, firms who return part of their earnings in the form of dividends are able to raise funds at a relatively low cost. This is due to the fact that these companies can lower or cut their dividends in order to raise funds (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004). However, keep in mind that lowering or cutting dividends may have a detrimental effect on the firm’s share price. Moreover, firms who do not offer dividend payments, need to raise external finance, which is more costly. Hence, one can expect that firms who pay dividends hold less

15 cash. Note that the majority of the researchers that examine the influence of dividend payments on cash holdings report a negative relation.

2.2.2. Pecking-order theory

The central assumption of the pecking-order theory is grounded on the notion that asymmetric information exists between managers (e.g. insiders) and outside investors. This is due to the fact that corporate managers possess more information about the firm and its investment opportunities than potential external investors. Consequently, it is more difficult for outside investors to, for instance, estimate the real value of firms’ investment opportunities, which results in higher costs for the firm when raising external capital (Myers & Maljuf, 1984). Hence, according to the pecking-order theory, companies prefer internal funding above external funding. However, when companies lack internal funds, they prefer debt funding over equity funding, this is also referred to as the hierarchy of financing sources. Myers & Maljuf (1984) indicate that this theory applies, in particular, on high-growth companies, considering that high growth companies may have to forego more valuable investment opportunities when experiencing cash deficits than firms with low growth opportunities. In addition, according to the pecking-order theory, companies do not have an optimal level of cash. Myers & Maljuf (1984) point out that cash functions as a buffer between firms’ retained earnings and their investment needs. Hence, when companies have insufficient retained earnings to fund their current investments, they use the accrued cash holdings, thereafter, they turn to debt and, if necessary, they issue equity (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004, p.300).

(i) Growth opportunity set

Companies that dispose of a large set of valuable growth opportunities are expected to hoard more cash. This is due to the fact that cash deficits cause firms to forego growth opportunities (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004). Furthermore, it is worthwhile to mention that, although this prediction is in line with that one of the trade-off theory, the two theories interpret it slightly differently (Hilgen, 2015). Regarding the trade-off point of view, firms hold more cash due to costly external finance, i.e. transaction costs model. The explanation of the pecking-order theory focusses on the disability of raising external funding due to asymmetric information, i.e. precautionary motive.

(ii) Leverage

In line with the pecking-order theory, companies prefer to fund investments with retained earnings. However, when the cost of investments exceeds retained earnings, companies first finance themselves with debt, according to the hierarchy of financing sources. Consequently, when costs of investments

16 surpass retained earnings, cash holdings decrease and firms’ debt increases (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004). Hence, one can expect a negative relationship between cash holdings and the degree to which firms are levered.

(iii) Size

The pecking-order theory suggests that large firms have been more successful. As a result, larger companies should have more cash, after controlling for investment (Opler et al., 1999, p.14).

(iv) Cashflow magnitude

According to the hierarchy of financing sources, firms prefer to fund their investments with internal resources. Hence, firms with high cashflows will hold more cash in order to fund future investments. In addition, Opler et al. (1999) argue that companies that experience high cashflows, reserve part of these earnings in the form of a cash buffer. Subsequently, firms can use the buffer in times of financial difficulties or to fund their investments. Hence, one can expect a positive relation between cashflow and firms’ cash holdings.

2.2.3. The free cashflow theory

The free cashflow theory (FCFT) or agency theory is based on the assumption of agency problems between corporate managers and shareholders. Jensen (1986) points out that managers do not always act in the best interests of shareholders and therefore do not maximize shareholders’ wealth, as the trade-off theory predicts. Subsequently, the FCFT is grounded on the notion that certain firms hold more cash than necessary, i.e. excessive cash. Jensen (1986) indicates that managers experience a larger stimulus to accumulate cash, which increases their discretionary power regarding the firm’s investment policy. Moreover, corporate managers that have sufficient cash holdings do not have to submit themselves to the outside scrutiny when raising external funds. Hence, excessive cash can incite corporate managers in pursuing growth opportunities, even when NPV is negative, or paying unreasonably high management fees. Consequently, one may derive that, although excessive cash has advantages for managers, it harms shareholder’s wealth.

(i) Growth opportunity set

Opler et al. (1999) indicate that entrenched corporate managers, in a firm with poor growth opportunities, tend to hold more cash in order to finance their growth projects, even when the NPV of these investments is negative, since it would be difficult to raise external capital to finance their investment program. Subsequently, the investment policy of these entrenched managers may result

17 in the destruction of shareholder value (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004). Hence, one may expect a negative relation between cash holdings androwth opportunity set.

(ii) Leverage

According Ferreira & Vilela (2004), managers in low levered companies are less subject to monitoring because they experience less regulations and requirements imposed by creditors. Consequently, managers obtain a larger discretionary power over the use of internal resources. However, once the managers are in charge of the internal funds, they must think of ways to put the money to work and hence invest in poor growth opportunities when good growth projects are not available (Opler et al., 1999). This may cause erosion of shareholder value. However, the use of leverage might resolve this agency problem, considering that debt covenants and requirements enforced by creditors function as a discipling force on management’s actions, and in turn, lower manager’s discretionary power of the use of internal resources (Hilgen, 2015; Kim, Kim & Woods, 2011). Hence, a negative relation between leverage and cash holdings may be expected.

(iii) Size

Ferreira & Vilela (2004) argue that larger firms tend to have a less concentrated ownership structure, which engenders superior managerial discretion. In addition, Opler et al. (1999, p.12) assume that “firms with anti-takeover amendments are more likely to hold excess cash”. Subsequently, they argue that size is a takeover deterrent since the bidder needs more financial resources to acquire a larger firm. Hence, in line with the free cashflow theory, one can assume that corporate managers of large firms dispose of a larger discretionary power regarding firms’ financial and investment policies, which in turn leads to larger cash holdings (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004).

18

2.3. Country-specific determinants

Alongside firm-specific determinants, country-specific determinants such as shareholder protection, creditor rights, rule of law and national culture dimensions might also impact the cash holdings incentives of firms (Guney et al., 2007). The aforementioned country characteristics are essential to understand the corporate finance practices in the various countries that we include in our study and will therefore be discussed in this section.

2.3.1. Investor protection & Legal environment

Guney (2007) defines agency problems as conflicts of interests between managers and shareholders or outside investors. As already mentioned, the agency theory suggests that managers do not always act in the best interests of shareholders and thus do not maximize shareholders wealth. Moreover, the FCFT is grounded on the notion that certain firms hold more cash than necessary, i.e. excessive cash. Jensen (1986) argues that this due to the fact that managers experience a greater stimulus to accumulate cash, which increases their discretionary power over the firm’s use of internal resources. “Having the cash, however, management must find ways to spend it, and hence chooses poor projects when good projects are not available” (Opler et al., pg.12, 1999), which harms shareholder’s wealth.

The above-mentioned agency problems are central to the free cashflow theory (Jensen, 1986). This theory obtained, contrary to the pecking-order theory and trade-off model, rather weak support based on extant studies. However, the majority of these studies are conducted on United States firms. Dittmar & Smith (2003) argue that since the United States is a common law country, the shareholders are well protected and can enforce managers to return excessive cash to shareholders (Hilgen, 2015). Hence, in a country such as the United States the variation in agency costs is too low to establish a significant impact on cash holdings (Hilgen, 2015). Dittmar et al. (2003) therefore compiled an international sample of approximately 11.000 firms from 45 countries around the world. They find evidence that companies in countries with poor shareholder protection hold up to twice as much cash than companies in a well-protected shareholder environment. Moreover, Ferreira & Vilela (2004) argue that the intensity of managerial agency costs differs to the extent that outside investors are protected, which means that both shareholder protection and creditor protection affect firms’ cash holdings. Furthermore, Ferreira & Vilela (2004) claim that the legal environment, i.e. law and order tradition of a country, enhances a country’s investor protection. Hence, it seems interesting to research the effects of investor protection and legal environment on cash holdings. In this paper, investor protection and legal environment consist of shareholder protection, creditor rights and rule of law, this is in line with Ferreira & Vilela (2004).

19 (i) Shareholder protection

According to Guney et al. (2007), the cost of raising external capital differs to the extent that shareholders are protected as this impacts the ability of firms to obtain external capital. For instance, in countries where shareholders are poorly protected, the anticipated agency costs are higher, resulting in limited external financing (Guney et al., 2007). Since corporations reside in an environment where external funds are limited, they pile up a significant amount of cash. Hence, one might argue that firms’ high cash balances are partly due to costly external financing, i.e. disability of raising funds, which is in line with the precautionary motive. However, Dittmar et al. (2003) and Ferreira & Vilela (2004) argue that this interpretation of the negative relation is rather benign. Dittmar et al. (2003) claim that corporate managers in countries with poor shareholder protection hold more cash, since shareholders cannot oblige them to upstream (excessive) cash to shareholders. Consequently, corporate managers are incentivized to accumulate cash, which enhances their discretionary power over firms’ investment policy, as a consequence, corporate managers are able to make decisions disregarding the interests of shareholders. (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004; Dittmar et al, 2003). In conclusion, Dittmar et al. (2003), Ferreira & Vilela (2004) and Guney et al. (2007) predict a negative relationship between corporations’ cash holdings and the extent to which their shareholders are protected. Both Dittmar et al. (2003) and Ferreira & Vilela (2004) support this assumption with empirical evidence. In contrast, Guney et al. (2007) find a positive relation between corporations’ cash holdings and the extent to which their shareholders are protected. This outcome implies that firms in countries where shareholders are well protected, hold more cash (Guney et al., 2007). However, they cannot explain this result.

(ii) Creditor protection

Ferreira & Vilela (2004) point out that investor protection consists of both shareholder protection and creditor protection. As we mentioned above, they predict a negative relations between corporations’ cash holdings and the extent to which their shareholders are protected. In addition, they also predict a negative relation between firms’ cash holdings and the degree to which creditors are protected. The rationale behind this hypothesis corresponds to that of shareholder protection. In particular, the presence of strong creditor protection may enhance debt covenants and - requirements enforced by creditors, which serves as a discipline force on management’s actions. Consequently, this may lead to lower managers’ discretionary power over the use of internal funds and their investment policy and, in turn, to lower cash holdings. They, again, support their hypothesis with empirical evidence. In contrast, Guney et al. (2007) distinguish between shareholder and creditor protection. Guney et al. (2007) argue that the presence of strong creditors, i.e. high creditor protection, can increase the likelihood of bankruptcy when facing financial distress. Consequently, in line with the precautionary

20 motive, corporate managers hold more cash in order to reduce the bankruptcy threat. However, they cannot support their hypothesis with empirical evidence.

(iii) Rule of Law

The variable rule of law embodies the legal environment of a country. Ferreira & Vilela (2004) argue that high tradition for law and order contributes to better investor protection and thus lower managerial agency costs. As a result, managers will not have the incentive to accumulate cash in order to gain discretionary power over firms’ investment policy (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004). Consequently, they expect a negative relation between corporations’ cash holdings and the countries’ tradition for law and order. This means that countries where tradition for law and order is poor, firms are expected to hold more cash. Ferreira & Vilela (2004) can support their assumption with empirical evidence. Moreover, their results with regard to the protection of shareholders, the protection of creditors and the rule of law support the free cashflow theory, given that the FCFT states that the incentive for managers to collect cash is higher when investor protection is low.

21

2.3.2. National culture

In addition to legal environment and investor protection, we implement another influential country-specific determinant, namely national culture. This is due to the fact that recent literature, like Chen, Dou, Rhee, Truong & Veeraraghaven, (2015) and Chang & Noorbakhsh (2009), claim that certain economic phenomena cannot be successfully examined if cultural values and environments are not taken into account.

Chen et al. (2015) and Chang & Noorbakhsh (2009) studied the effect of national culture on cash holdings. They claim that culture values and - environment where the companies reside, matter in explaining corporations’ cash holdings. For instance, Chang & Noorbakhsh (2009) indicate that although countries may have a similar level of investor protection, managers/investors may perceive the agency problems differently. Hence, the differences regarding the previously mentioned perceptions may be caused by different cultural environments and values (Chang & Noorbakhsh, 2009 and Hilgen, 2015). Hofstede (1980, p.25) defines culture as “the collective programming of the mind distinguishing the members of one group or category of people from others”. Hofstede, initially, ascertained four cultural dimensions, i.e. uncertainty avoidance, power distance, masculinity and individualism, based on the data he collected. In past decades, this framework has been a widely used proxy for analyzing the impact of cultural values on companies and decision making. (Chang & Noorbakhsh, 2009). Furthermore, Hofstede later implemented a fifth and sixth dimension, namely long-term orientation and indulgence. In this paper we can only include masculinity and long-term orientation, due to the fact that the other relevant culture dimensions experience too high correlations with other explanatory variables in our study (see section 4)

(i) Masculinity

According to Hofstede (1980), the cultural dimension masculinity (MAS) establishes a difference between “tough” and “tender” cultures. He points out that countries, dominated by masculinity, represent a society where achievements, profit, decisiveness and high rewards for success are of high importance. In a masculine society, corporations tend to be more competitive and profit driven. As a result, managers in a masculine culture need to be “assertive”, “competitive”, ambitious” “performance driven” and “decisive” (Chang & Noorbakhsk, 2009). In line with the free cashflow theory, managers in masculine societies are therefore expected to enhance discretionary power over firms’ internal funds and investment policy, with the aim to achieve abnormally high ROI. It is expected that such managers prefer to have enough cash/liquidity at hand, so they do not have to submit themselves to the outside scrutiny when raising external funds (Chang & Noorakhsh, 2009). Furthermore, the quest for extraordinary high rates of return, accompanied with little shareholder supervision, may result in squandering cash on value-reducing and risky growth projects (Chang &

22 Noorbakhsh, 2009). This behaviour is, however, tolerated in a highly masculine society. Therefore, Chang & Noorbakhsh (2009) expect that in highly masculine societies decisions regarding the management of firms' cash holdings will coincide, for a large extent, with the free cashflow theory (Chang & Noorbakhsh, 2009). Hence, one can expect a positive relationship between cash holdings and the score on the masculinity index.

(ii) Long-term orientation

Hofstede (1991) implemented, based on a Chinese value survey, an additional cultural dimension,

namely term orientation. According to Hofstede (1991), countries that score low on the long-term orientation (LTO) index are more conservative regarding their “traditions”, “norms” and perceive changes in societies with distrust. In contrast, countries that score high on the previous mentioned index possess more of a pragmatic state of mind. In these societies values such as perseverance, thrift, effort and risk-averse attitude towards failure are extremely important. According to Chang & Noorbakhsh (2009), managers in a high LTO environment focus on long term value creation and thus evaluate investment opportunities based on a sustainable and long-term profitability instead of short-term rates of return. In addition, investors also prefer sustainable, long short-term value creation, instead of short-term rate of returns. Chang & Noorbakhsh (2009) also indicate that corporate managers in this environment possess, as previously mentioned, a risk-averse attitude towards failure. As a result, managers tend to be very careful regarding risky investments, bankruptcy threats and financial distress. Furthermore, Newman & Nollen (1996, p.759) prove that “management practices, consistent with a long-term cultural orientation include providing long-term employment”, which implies that in order to be able to offer long-term security to employees, firms must preserve larger cash holdings to support this (Chang & Noorbakhsh, 2009). Hence, one can expect a positive relationship between cash holdings and the score on the long-term orientation index.

23

2.3.3. Ownership and control

In this paper we do not examine the impact of ownership and control on corporate cash holdings, due to insufficient data. However, we believe that including ownership and control in this literature review gives a more comprehensive overview regarding the notion cash holdings. According to La Porta & Lopez-de-Silanes (1998, 1999), corporations’ ownership structure is less concentrated in countries with high shareholder protection. In addition, Guney et al. (2007) point out that the ownership structure might have an impact on agency problems. They suggest that it is possible to reduce agency problems when corporate managers are being monitored by investors. For an average shareholder, however, the cost of monitoring managers will most likely surpass the benefits (Grossman and Hart, 1988). In comparison, large shareholders, who have a claim on large fractions of the firm, are more equipped to monitor managers more effectively and therefore, for large shareholders the benefits surpass the costs. (Guney et al., 2007). Hence, corporations with highly concentrated shareholders are more able to manage the agency problems, resulting in lower agency costs and thus lower external financing costs. As a result, managers do not have the incentive to accumulate cash. Ferreira & Vilela (2004) and Guney et al. (2007) back this assumption up with empirical evidence.

24

2.4. Hypotheses development

In this subsection, we formulate our hypotheses based on the distinctive predictions made by the trade-off theory, pecking-order theory and the free cashflow theory concerning the following firm-specific determinants: growth opportunity set, business risk, size, cashflow magnitude, working capital and leverage. Furthermore, we develop our hypotheses concerning the following country-specific determinants: shareholder protection, creditor rights, rule of law, long-term orientation and masculinity based on the extant academic findings, which we discussed earlier.

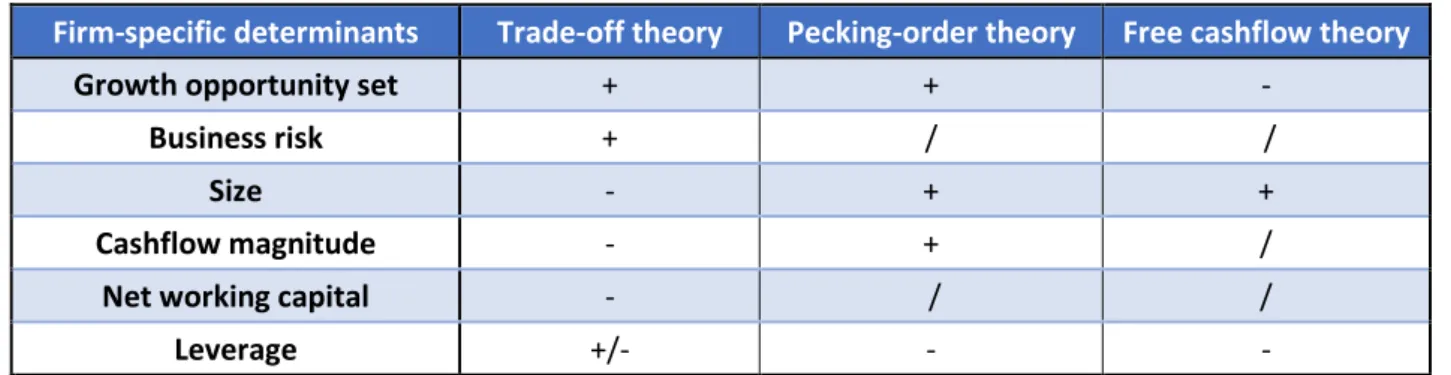

Table 1: overview firm-specific hypotheses from the different theoretical models

Firm-specific determinants Trade-off theory Pecking-order theory Free cashflow theory

Growth opportunity set + + -

Business risk + / /

Size - + +

Cashflow magnitude - + /

Net working capital - / /

Leverage +/- - -

Table 1 depicts the relationships between the firm-specific determinants and cash holdings, based on the three theoretical models. A ‘+’ indicates a positive relationship, whereas a ‘-‘ indicates a negative relationship. ‘/’ implies that the model does not make an assumption on the relation. Source: Ferreira & Vilela (2004)

Table 2: Overview findings firm-specific determinants on cash holdings

Firm-specific determinants Ferreira & Vilela (2004) Opler et al. (1999) Drobetz & Grüninger (2007) Kim et al. (2011) Ozkan & Ozkan (2004) Guney et al. (2007) Growth opportunity set + + n.s. + + + Business risk - + + / n.s. + Size - - - - n.s. - Cashflow magnitude + + + n.s. + + NWC - - - + Leverage - - - n.s. - +/-

Table 2 depicts the findings of authors who studied the relationship between firm-specific determinants and cash holdings. A ‘+’ indicates a positive relationship, whereas a ‘-‘ indicates negative relationship. The label ‘n.s.’ means no significant relationship and ‘/’ implies that the authors did not include the variable in their study. Source Hilgen

25 (i) Growth opportunity set

Both the pecking-order theory and trade-off theory impute a positive relationship between cash holdings and growth opportunity set. We mentioned earlier that these two theories interpret the underlying relation in a slightly different way. More specifically, according to the trade-off theory, companies hold more cash due to costly external capital, whereas companies, in line with the pecking-order theory, might not be able to obtain external capital due to asymmetric information. In contrast, the free cashflow theory assumes that entrenched managers with large discretionary power, hold more cash in order to finance their poor growth projects, even when NPV of the projects is negative (Opler et al, 1999). Since the trade-off theory and the pecking-order theory outweigh the free cashflow theory, we assume that:

Hypothesis 1: Cash holdings are positively related to growth opportunities

(ii) Business risk

Concerning the determinant business risk in table 1, we notice that solely the trade-off theory predicts a relation between business risk and cash holdings. According to the trade-off theory, corporations with high cashflow volatility are more likely to endure cash deficits, when facing unforeseen cashflow deterioration (Ozkan & Ozkan, 2004). Subsequently, in order to prevent financial distress and refraining from investments, companies with high cashflow variability hold a larger cash buffer. Moreover, we notice that the findings of the authors are ambiguous, therefore we formulate our hypothesis based on the trade-off theory. Hence, we assume that:

Hypothesis 2: Cash holdings are positively related to business risk

(iii) Size

Both the pecking-order theory and free cashflow theory suggest a positive relation between cash holdings and the size of the firm, whereas the trade-off theory posits a negative relation. The pecking-order theory suggests that large firms have been more successful and as a result have more cash than smaller companies. In addition, the free cashflow theory suggests that larger firms tend to have a less concentrated ownership structure, which enhances managers’ discretionary power regarding firms’ financial and investment policies, leading to larger cash holdings( Ferreira & Vilela, 2004). In contrast, the trade-off theory argues that large corporations, among other things, encounter economies of scale when it comes to cash management and thus hold less cash compared to smaller firms (Miller & Orr, 1966). If we look at table 1, we should assume a positive relation between firms’ size and cash

26 holdings, as from a theoretical perspective the free cashflow theory and the pecking-order theory outbalance the trade-off theory. However, when looking at table 2, we notice that the majority of scholars report a negative relation between leverage and cash holdings. Hence, we assume that: Hypothesis 3: Cash holdings are negatively related to firms’ size

(iv) Cashflow magnitude

Regarding the determinant cashflow magnitude in table 1, we notice that the trade-off theory and the pecking-order theory contradict each other. According to the trade-off theory, companies with high cashflow can afford to hold less cash. In contrast, the pecking-order theory argues that companies that experience increased cashflow will reserve part of these earnings in the form of a cash buffer, considering that, in line with the hierarchy of financing sources, firms prefer to fund their investments with internal resources (Opler et al.,1999). Considering that the rationale of the pecking-order theory seems more plausible and that authors support the pecking-order theory’s prediction with empirical evidence, we assume that:

Hypothesis 4: Cash holdings are positively related to the cashflow magnitude

(v) Net working capital

Concerning the determinant net working capital in table 1, we notice that solely the trade-off theory predicts a relation between working capital and cash holdings. In line with the trade-off theory, NWC can be considered as a substitute for cash and cash equivalents, due to the fact that NWC is perceived as highly liquid and thus can easily be converted into cash (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004). Moreover, the findings of the authors unanimously support the trade-off theory’s prediction, hence we assume that:

Hypothesis 5: Cash holdings are negatively related to net working capital

(vi) Leverage

The pecking-order theory and the free cashflow theory assume a negative impact of leverage on cash holdings. Furthermore, the trade-off theory’s predictions regarding the relation between leverage and cash holdings are ambiguous. The ambiguity regarding the trade-off theory’s predictions is due to two different streams of thought within this theory. First, high levered firms accumulate more cash in order to pay its obligations and to reduce the likelihood of financial distress (Han & Qui, 2007). Second, the

27 extent to which companies are levered indicates how easily firms can raise external funds and thus one might expect that high levered firms can effortlessly raise external capital, which encourages them in holding less cash (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004). In addition, the pecking-order theory underlines the importance of the hierarchy of financing sources. For instance, when the costs of investment exceed retained earnings, firms’ cash holdings decrease and their debt level rises, since debt is the second favored source of funding according to the aforementioned hierarchy (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004). Lastly, the free cashflow theory suggests that managers in low levered companies are less subject to monitoring, which enhances their discretionary power over the use of internal funds and leads to larger cash holdings (Ferreira & Vilela, 2004). In conclusion, when looking at table 2, the majority of authors support the negative relation with empirical evidence. Hence, we assume that:

Hypothesis 6: Cash holdings are negatively related to leverage

(vii) Shareholder protection

The majority of the existing academic literature which we discussed earlier imputes a negative relation with cash holdings. However, scholars interpret the negative relation slightly different. Guney et al. (2007) argue that in countries where shareholders are poorly protected, the anticipated agency costs, which impacts the ability for firms to raise external capital and hence results in limited external financing. In contrast, Ferreira & Vilela (2004) argue that corporate managers are incentivized to accumulate cash, which enhances their discretionary power over the firm’s investment policy. Note that we follow the second flow of thought. Furthermore, the majority of the authors who examined the relation between shareholder protection and cash holdings ascertained a negative relation. Hence, we assume that cash holdings are negatively related to shareholder protection.

Hypothesis 7: Cash holdings are negatively related to shareholder protection

(viii) Creditor rights

There are two streams of thought regarding the notion creditor rights. First, Ferreira & Vilela (2004) point out that investor protection consists of shareholder protection and creditor protection and that the rationale behind the hypothesis of creditor rights corresponds to that of shareholder protection. In particular, the presence of strong creditor protection may enhance debt covenants and requirements enforced by creditors, which function as a discipling force on management’s actions. Consequently, this may lead to lower manager’s discretionary power over the use of internal funds and their investment policy. As a result, firms in such an environment will hold less cash. The second

28 flow of thought distinguishes between shareholder and creditor protection. Guney et al. (2007) presume that firms in countries with high creditor protection build up larger cash holdings, due to the fact that high creditor protection can augment the likelihood of bankruptcy when facing financial distress. However, when looking at table 2, one can see that empirical evidence supports Ferreira & Vilela’s (2004) prediction. Consequently, we assume that:

Hypothesis 8: Cash holdings are negatively related to creditor rights

(ix) Rule of Law

Ferreira & Vilela (2004) argue that high tradition for law and order contributes to better investor protection and thus lower managerial agency costs. As a result, managers will not have the incentive to accumulate cash in order to gain discretionary power over the firm’s investment policy. Furthermore, they can support their assumption with empirical evidence. Hence, we assume that: Hypothesis 9: Cash holdings are negatively related to the rule of law

(x) Masculinity

Hofstede (1980) points out that countries, dominated by masculinity, represent a society where achievements, profit, decisiveness and high rewards for success are paramount. Moreover, in line with the free cashflow theory, managers in masculine societies are therefore expected to enhance discretionary power over the firm’s internal funds and investment policy. Consequently, it is expected that corporate managers prefer to have enough liquidity at hand (Chang & Noorakhsh, 2009). In addition, the extant academic literature regarding the impact national culture has on cash holdings is very scarce. Chang & Noorbakhsh (2009) and Chen et al. (2015) are the most prominent authors who study the impact of national culture on cash holdings. However, only Chang & Noorbakhsh (2009) include the cultural dimensions masculinity and long-term orientation in their study. Consequently, we will formulate our hypothesis based on the empirical evidence found by Chang & Noorbakhsh (2009). Therefore, we assume that:

29 (xi) Long-term orientation

According to Chang & Noorbakhsh (2009), managers in a high LTO environment focus on long-term value creation and, thus, evaluate investment opportunities based on a sustainable and long-term profitability and not on short-long-term rates of return. Moreover, investors also prefer sustainable, long term value creation, instead of short-term rate of returns. In addition, it is also suggested that corporate managers in this environment have a risk-averse attitude towards failure. As a result, managers tend to be very careful regarding risky investments, bankruptcy threats and financial distress. In addition, Chang & Noorbakhsh (2009) can support their, predicted, positive relation with empirical evidence. Hence, we assume that:

Hypothesis 11: Cash holdings are positively related to long-term orientation

Table 3: Overview findings country-specific determinants on cash holdings

Country-specific determinants Ferreira & Vilela (2004) Guney et al. (2007) Dittmar et al. (2007) Chang and Noorbakhsh (2009) Shareholder protection - + - / Creditor rights - - / / Rule of Law - / / / Masculinity / / / + Long-term orientation / / / +

Table 3 shows the findings of authors who studied the relationship between country-specific determinants and cash holdings. A ‘+’ indicates a positive relationship, whereas a ‘-‘ indicates negative relationship. The label ‘/’

30

3. Data

3.1. Sampling

For this master thesis we consult the database Orbis from Bureau Van Dijk. Orbis is the ultimate source for retrieving firm-specific data from companies worldwide. Since this study requires detailed financial numbers, we decided to observe publicly listed firms as they entail the most information. In contrast to Ferreira and Vilela (2004) who researched EMU countries at the end of the 20th century, our

research has a broader scope, namely the subsequent EU countries: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, The Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and United Kingdom. Note that we deliberately chose to include the United Kingdom since it was part of the EU during the sample period of this paper, which ranges from 2013 to 2018. This paper’s dataset includes survivors and non-survivors that appeared on Orbis at any time in the sample period.

Next, when collecting our sample, we excluded

• (i) financial firms, with NACE rev 2 code: 35 & 36 • (ii) utilities, with NACE rev 2 code: 64, 65 & 66 • (iii) public services with NACE rev 2 code: 84 & 85

In particular, we exclude the financial firms from the sample since their inventories contain marketable securities that are included in their cash and cash equivalents (Opler et al., 1999). Furthermore, financial firms are obliged to meet certain statutory capital requirements (e.g. common equity tier 1). In addition, it is conventional for financial firms to be highly levered, although a high leverage ratio does not mean the same for financial companies as it does for non-financial companies, where high leverage suggests a higher probability of financial distress. (Fama & French, 1992). We also eliminate the utility sector from our sample since Opler et al. (1999) point out that the cash holdings of these firms can be subject to state supervision. Furthermore, we also require firms to have available accounts for all the variables, over the whole sampling period. If this is not the case, they are eliminated from the sample. Lastly, note that, although Orbis is perceived as a qualitative database, we eliminated multiple companies from the sample that are characterized by irregularities (e.g. negative cash ratio, negative total assets).

As a result, we dispose over 1013 firms with each 6-year observations, which brings the total to 6078 observations. Moreover, one can note that the data both has a cross-sectional dimension and a time-series dimension. This is referred to as panel data (or longitudinal data). The cross-sectional dimension manifests itself as observations that are being made across multiple firms at a single point

31 in time. The time series dimension is represented by repetitive measurements of the same firm. The major advantage of panel data consists of having a lot of observations, while it also controls for individual heterogeneity (Hilgen, 2015). In addition, Woolridge (2002) points out that panel datasets are more appropriate to study complex and dynamic models as it reveals how units change over time, compared to cross-sectional regression. In contrast, panel data is often submissive to missing observations. For instance, we deal with missing observations in this particular dataset when firms go private, merge or go bankrupt.

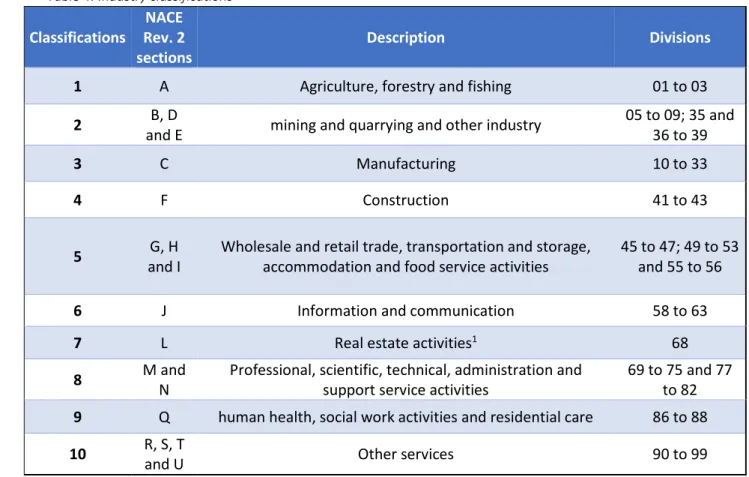

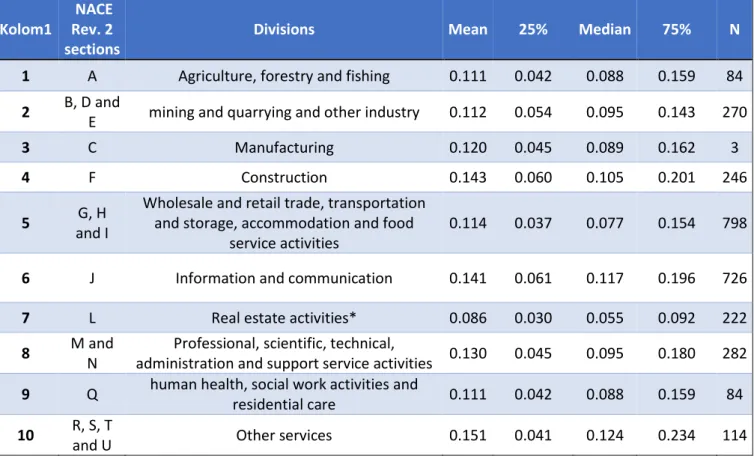

Table 4 displays the different industry classifications that we use in this paper. This classification is based on the ‘high-level SNA/ISIC aggregation A*10/11’ from Eurostat. However, we excluded section K as this consists of finance and insurance activities. In addition, we also excluded section O and P, since these sections entail public administration and defense, compulsory social security and education.

Table 4: Industry classifications

Classifications

NACE Rev. 2 sections

Description Divisions

1 A Agriculture, forestry and fishing 01 to 03

2 B, D

and E mining and quarrying and other industry

05 to 09; 35 and 36 to 39 3 C Manufacturing 10 to 33 4 F Construction 41 to 43 5 G, H and I

Wholesale and retail trade, transportation and storage, accommodation and food service activities

45 to 47; 49 to 53 and 55 to 56

6 J Information and communication 58 to 63

7 L Real estate activities1 68

8 M and

N

Professional, scientific, technical, administration and support service activities

69 to 75 and 77 to 82 9 Q human health, social work activities and residential care 86 to 88 10 R, S, T

and U Other services 90 to 99

32

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. Dependent variable

The aim of this paper is to analyze the determinants of cash holdings. Therefore, we employ cash holdings as dependent variable and the firm-specific determinants, proposed by the three theoretical models, as independent firm-specific variables. In addition, we also include country-specific determinants as independent variables in order to provide a more comprehensive overview regarding the notion cash holding.

(i) Cash holdings

We define cash holdings as the sum of cash and cash equivalents, which is a common accounting term. Afterwards, this sum is divided by total assets. The outcome, also known as the cash ratio, measures the percentage of companies’ assets that are held in the form of cash and cash equivalents. The used formula is in line with academic literature (Kim et al., 1998; Ozkan & Ozkan, 2004).

3.2.2. Independent firm-specific variables

(i) Growth opportunity set

We use the market-to-book (MBT) ratio as a proxy for a company’s growth opportunity set. The ratio is calculated by dividing a firm’s market value per share end) to its book value per share (year-end). Since growth opportunities are not incorporated in the balance sheet, one can expect that a larger growth opportunity set increases the firm’s market value in relation to its book value (Hilgen, 2015; Ferreira & Vilela, 2004).

(ii) Firm size

In line with academic literature, we define firm size as the natural logarithm of the book value of the firm’s total assets (Kim et al., 1998; Ferreira & Vilela, 2004 and Opler et al., 1999). The natural logarithm is used to reduce the spread of the balance sheet values of the observations in the database resulting in smaller differences between the size of the firms (Blondelle, 2018, p. 24).

(iii) Cashflow magnitude

The cashflow ratio is measured as net income plus depreciation and divided by total assets. This formula is in line with Ozkan & Ozkan (2004). The calculation used by Orbis to determine a company’s cashflow, can be retrieved in Attachment 1, table 21.

33 (iv) Business risk

As a proxy for business risk, we use the cashflows of the last three years in order to measure the standard deviation of cashflows. Subsequently, we divide the outcome to total assets. This formula is in line with Ozkan & Ozkan (2004).

(v) Net working capital

Net working capital can be thought of as a substitute for cash and cash equivalents as it is highly liquid and thus can easily be converted into cash. We calculate the NWC ratio as accounts receivable + inventory – accounts payable divided by total assets

(vi) Leverage

The variable leverage is measured by dividing total debt, i.e. sum of short-term debt plus long-term debt, to total assets. This measurement is in line with Ferreira and Vilela, (2004), Ozkan en Ozkan, (2004), Kim et al., (1998).