CONTROL OF TAENIA SOLIUM IN

ZAMBIA

GPS TRACKING OF FREE-RANGING PIGS TO DEFINE RING

TREATMENT

STRATEGIES

FOR

THE

CONTROL

OF

CYSTICERCOSIS

Word count: <19.790>Fien Coudenys

Student number: 01307036Supervisor: Prof. dr. Sarah Gabriël

Supervisor: Dr. Inge Van Damme

Local supervisor: Dr. Kabemba E. Mwape

A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Veterinary Medicine

CONFIDENTIAL

DO NOT COPY, DISTRIBUTE OR MAKE PUBLIC IN ANY WAY

This thesis contains confidential information proprietary to Ghent University or third parties. It is strictly forbidden to publish, cite or make public in any way this thesis or any part thereof without the express written permission by Ghent University. Under no circumstance this thesis may be communicated to or put at the disposal of third parties. Photocopying or duplicating it in any other way is strictly prohibited. Disregarding the confidential nature of this thesis may cause irremediable damage to Ghent University.

Ghent University, its employees and/or students, give no warranty that the information provided in this thesis is accurate or exhaustive, nor that the content of this thesis will not constitute or result in any infringement of third-party rights.

Ghent University, its employees and/or students do not accept any liability or responsibility for any use which may be made of the content or information given in the thesis, nor for any reliance which may be placed on any advice or information provided in this thesis.

Preamble

Preface

The basis of this research originates from my major interest in One Health, and my profound fascination for the continent of Africa. When I heard Prof. Dr. Sarah Gabriël enthusiastically talk about her ongoing project in Zambia during one of our classes, I knew I had to talk to her. Little did I know it would be the start of a wonderful journey and would spark my interest in science more than I thought possible.

I could not have achieved any of this without the support and help of some important people. Firstly, I would like to offer my special thanks to my promotors Prof. Dr. Sarah Gabriël, Dr. Inge Van Damme and Dr. Kabemba E. Mwape for believing in me and supporting me endlessly throughout this exciting opportunity. A special thank you to Prof. Dr. Sarah Gabriël for giving me the opportunity to experience field work in Zambia. You taught me a lot throughout the past year of working together and I will always look up to you. You continuously encouraged me to improve and made me enthusiastic about research. Thank you, Dr. Inge van Damme, for withstanding all my distress calls and e-mails. Without your patience and help with coding in RStudio, I would not have been able to process and achieve my results. Dr. Kabemba E. Mwape, a warm thank you for welcoming me on my very first day in Zambia and immediately making me feel at home.

Secondly, I wish to thank all whom I have had the pleasure to work with during my stay in Zambia. Thank you, Chiara, for spending days with me in the burning African sun looking for human stool. Thank you Chembe, Max, and all other field members for making my experience wonderful and memorable. Thank you to Zambia and all inhabitants whom I had the pleasure to meet for making me feel happier than ever.

Last but not least, I want to thank all those whom I love. Above all, my dear parents; thank you for always supporting my decisions, giving me the opportunity to fulfil my dream to become a veterinarian and travel throughout my studies. Most importantly, thank you for always believing in me. I am full of gratitude towards my sweet little brother, for bearing with me during my exams and his attempts to be silent (although he wasn’t always sincere). I am grateful for my friends, especially those I met in the past six years, sharing laughter and tears. Thank you for all the distractions and beautiful memories. I would never have had such an amazing student time if it wasn’t for you.

So, thank you to everyone mentioned above. Or as a Zambian would say: “Zikomo kwambiri”!

Table of contents

1 Summary 7

2 Literature study 9

2.1 Background 9

2.1.1 Morphology Taenia solium 9

2.1.2 Life cycle 10

2.1.3 Prevalence 11

2.1.4 Risk factors of transmission 12

2.1.5 Burden of the disease 12

2.1.6 Diagnosis 13

2.2 Control and prevention 14

2.2.1 Measures targeting pigs 14

2.2.2 Measures targeting humans 17

2.3 Preventive chemotherapy 18

2.3.1 Mass drug administration (MDA) 18

2.3.2 “Track and treat” 20

2.3.3 Focus group administration (FGA) 20

3 Objectives 23

4 Material and Methods 24

4.1 CYSTISTOP 24

4.2 Study site and population 25

4.2.1 Study area and population 25

4.2.2 Sample size 26

4.2.3 Study pigs 26

4.3 GPS tracking 27

4.3.1 Study design 27

4.3.2 GPS application on the pigs 27

4.4 Human defecation mapping 28

4.5 Mapping and statistical analysing 29

4.5.1 Download data from GPS devices and the EpiCollect5 application 29

4.5.2 Data cleaning 29

4.5.3 Data analyses 29

4.6 Ethical approval 30

5 Results and discussion 31

5.1 Pig population and roaming ranges 31

5.1.1 Pig population 31

5.1.2 Pig data cleaning 33

5.1.3 Pig roaming ranges results 34

5.2 Human population and open defecation sites 39 5.3 Pigs’ interactions with defecation sites 40

5.3.1 Contact with ODF sites within 50-meter radius (primary ODF area) 40 5.3.2 Contact with ODF sites outside 50-meter radius (secondary ODF area) 40

6 Conclusions and recommendations 44

7 References 46

List of abbreviations

Ab Antibody

Ag Antigen

CC Cysticercosis

EITB Enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot ELISA Enzyme-linked immuno sorbent assay FAO Food and Agriculture Organisation FGA Focus group administration

GPS Global Positioning System HCC Human cysticercosis MDA Mass drug administration NCC Neurocysticercosis

NCS Niclosamide

NTD Neglected Tropical Disease ODF Open Defecation

PCC Porcine cysticercosis PCR Polymerase chain reaction PZQ Praziquantel

SOP Standard Operating Procedure SSA Sub-Saharan Africa

STH Soil-transmitted helminths

TS Taeniasis

1 Summary

The cysticercosis/taeniasis zoonotic disease complex, caused by Taenia solium, is classified as the number one foodborne parasitic disease. T. solium causes porcine cysticercosis (PCC) in pigs and taeniasis (TS) and cysticercosis (CC) in humans. In humans, the cysticerci have a predilection for the central nervous system causing neurocysticercosis (NCC), which is, in endemic countries, responsible for the majority of acquired epilepsy. Multiple strategies to control the parasite have been described yet a standardised validated strategy is still lacking.

Ring treatment is one of the new strategies and a potential alternative to mass drug administration (MDA), implemented in Katete District in Zambia. Yet, the size of the ring needs to be determined for which pig movement plays a vital role. Currently, there is no data available regarding pig movement in sub Saharan Africa. Therefore, the main objective of this masters’ thesis is to evaluate pig roaming ranges in this area and contribute to defining ring treatment strategies for the control of cysticercosis.

Roaming ranges of 43 local pigs were collected by attaching GPS devices for a duration of three-to-four days in both rainy and dry season. Simultaneously during the visit, human open defecation (ODF) sites were mapped in the villages and contact between tracked pigs and ODF sites was assessed.

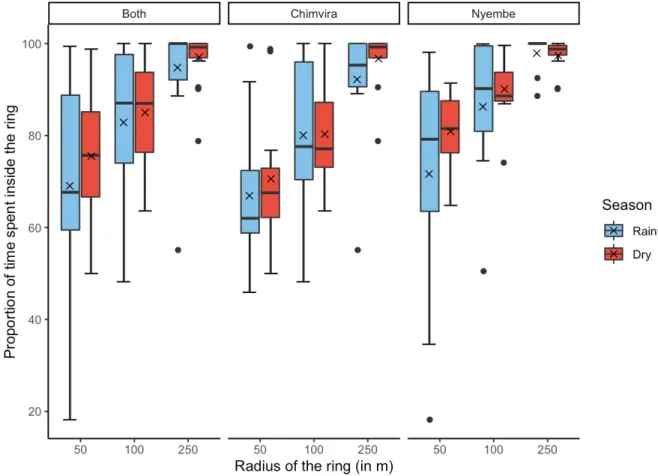

Major findings are that in both seasons, pigs spent most of their time inside their 50-meter radius (medians: 67.7% and 75.7% during rainy and dry season respectively), where open defecation is practiced. However, 23 out of 43 tracked pigs still spent some time outside their 250-meter radius. Pigs spent an average of 6.3 minutes per day in contact with ODF sites outside their 50-meter radius. However, it is important to be mindful that there are many restrictions to the ODF observations. Concluding, the most likely area of infection for pigs in this region is within 50-meter of their residences. Ideally, in order to implement a successful ring treatment strategy in any area, a large-scale study should be performed on pigs’ roaming behaviour and interaction with open defecation in that particular area.

Samenvatting

Het cysticercose/taeniasis zoönotisch complex, veroorzaakt door Taenia solium, is geclassificeerd als nummer één op de lijst van voedselgebonden parasitaire ziekten. T.

solium veroorzaakt porciene cysticercose (PCC) in varkens en taeniasis (TS) en

cysticercosis (CC) in mensen. De predilectieplaats voor cysticercen bij de mens is het centrale zenuwstelsel wat aanleiding geeft tot neurocysticercose (NCC). Dit is de belangrijkste oorzaak van verworven epilepsie in endemische landen. Meerdere controlestrategieën voor de parasiet zijn beschreven, maar een gestandaardiseerde en gevalideerde strategie ontbreekt nog.

Ring-behandeling is één van de nieuwe strategieën en een mogelijk alternatief voor massa behandelingen (MDA), geïmplementeerd in het Katete District in Zambia. Hiervoor moet echter de grootte van de ring bepaald worden, waarbij verplaatsingen van varkens een belangrijke rol spelen. Momenteel is nog geen informatie beschikbaar met betrekking tot de loopafstanden van varkens in sub Sahara Afrika. Bijgevolg is het hoofddoel van deze Masterproef om loopafstanden van varkens te observeren in deze regio en bij te dragen tot de bepaling van ring-behandelingsstrategieën in de controle van cysticercosis.

Loopafstanden van 43 lokale varkens werden bepaald door het aanbrengen van gps-toestellen gedurende een periode van drie tot vier dagen tijdens het regen- en droogseizoen. Gelijktijdig werden in de dorpen open defecatieplaatsen (ODF) van mensen in kaart gebracht en interactie tussen varkens en ODF plaatsen werd onderzocht.

De belangrijkste bevindingen waren dat varkens in beide seizoenen het grootste deel van hun tijd doorbrachten binnen hun straal van 50 meter (mediaan: 67,7% en 75,7% tijdens respectievelijk het regen- en droogseizoen), waar ook open defecatie plaatsvond. Echter spendeerden 23 van de 43 getraceerde varkens nog steeds enige tijd buiten een straal van 250 meter. Varkens spendeerden gemiddeld 6,3 minuten per dag in contact met ODF-plaatsen gelegen buiten hun 50-meter radius. Het is overigens wel belangrijk om te benadrukken dat er veel beperkingen zijn aan de ODF-waarnemingen. We kunnen concluderen dat het meest waarschijnlijke besmettingsgebied voor varkens in deze regio zich binnen de 50 meter van hun verblijfplaats bevindt. Om een succesvolle ring-behandelingsstrategie te implementeren in een gebied zou idealiter een grootschalige studie uitgevoerd moeten worden om de loopafstanden van varkens en de interactie met open defecatie in dat specifieke gebied te bepalen.

2 Literature study

2.1 Background

2.1.1 Morphology Taenia solium

Taenia solium is classified as a tapeworm, which is a flat, segmented worm that lives in the

small intestine of human. The adult tapeworm has a scolex (head) with four suckers and a rostellum with hooks, a neck and strobila, containing potentially more than a thousand proglottids (Fig. 1). With help of the suckers and hooks, the worm attaches to the mucosa of the small intestine. The proglottids mature and have different developmental stages. Proximal proglottids are immature, followed by mature proglottids and distal gravid proglottids filled with eggs. These eggs are being released through stool into the environment and can immediately infect potential intermediate hosts. However, these eggs are also extremely resistant in the environment (Garcia et al., 2003a; Flisser et al., 2005).

Figure 1. Representative structure of Taenia solium1

After ingesting T. solium eggs by the intermediate host, the larvae of the parasite migrate to tissues such as muscle and brain, which causes local infection resulting in small vesicles called cysticerci.

Cysticerci can be divided into three different stages. Early in the infection, a viable cyst appears. Later on, the cyst degenerates and a mixed inflammatory or granulomatous reaction is present in the surrounding tissues (Ingh et al., 2013). The final stage is observed when the cyst dies and a process of mineralization and resorption takes place resulting in a calcified nodule (Garcia and Del Brutto, 2000; Takayanagui and Odashima, 2006).

https://www.msdmanuals.com/professional/infectious-diseases/cestodes-2.1.2 Life cycle

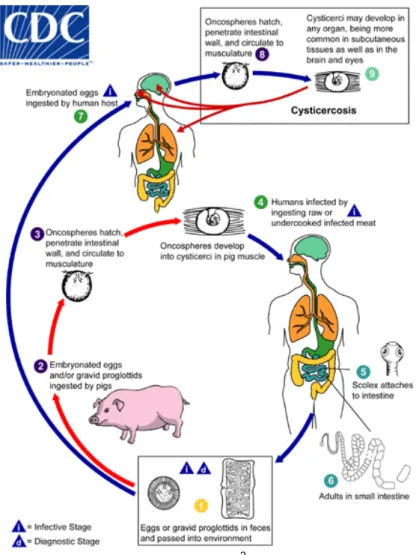

As the definite host, humans are the carrier of the adult tapeworm, which manifests in the intestine (known as taeniasis (TS)). This occurs when humans consume insufficiently heated pork infected with viable cysticerci. The larvae develop to adult tapeworms in the small intestine and approximately two to three months later gravid proglottids containing fertile eggs are being expelled through stool (Murrell et al., 2005). In rural areas where open human defecation is still common these eggs end up in the environment. Free ranging domestic pigs, the usual intermediate host, ingest these eggs/proglottids through coprophagic behaviour or by ingesting contaminated water/food. Once ingested, oncospheres will hatch in the intestine, invade the intestinal wall and subsequently enter the bloodstream. This allows them to migrate to multiple tissues and organs where they mature into cysticerci. This process takes approximately eight weeks, resulting in porcine cysticercosis (PCC). Humans can accidentally ingest T. solium eggs by faecal-oral contamination and become infected as an accidental intermediate host (human cysticercosis (HCC)) (Fig. 2). This infection causes pathology in different tissues, including the brain, causing neurocysticercosis (NCC), responsible for the majority of acquired epilepsy in endemic areas (Ndimubanzi et al., 2010).

Figure 2. Life cycle of Taenia solium2

2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013,

2.1.3 Prevalence

T. solium is endemic in low and middle-income countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), Asia

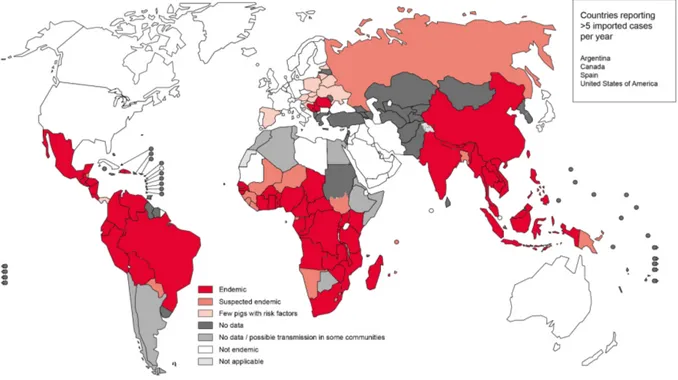

and Latin America (Fig. 3), but its occurrence has been increasingly reported in non-endemic areas such as the United States of America and Europe (Serpa and White, 2012; Fabiani and Bruschi, 2013; Trevisan et al., 2018). An increasing movement of people from endemic areas (both immigrants and travellers) in addition to a shift towards outdoor pig farming and (illegal) movements of infected pigs or pork is thought to be the reason for this increased prevalence in previously unaffected regions (Del Brutto, 2012a, 2012b). This could potentially cause an establishment of new endemic areas (Gabriël et al., 2015).

Based on a systematic review and meta-analyses, the estimated prevalence of circulating T.

solium antigens (Ag) in humans was 7.30% in SSA. This indicates an active infection with

HCC. In Latin America and Asia, the prevalence was 4.08% and 3.98% respectively. An estimated seroprevalence of T. solium antibodies (Ab) of 17.37% was found in SSA, 15.68% in Latin America and 13.03% in Asia. Apparent prevalence of taeniases ranged from 0 to 17.25% due to regional differences and variations in used research techniques (Coral-Almeida et al., 2015).

A study regarding PCC prevalence in the Eastern, Southern and Western provinces of Zambia showed a seroprevalence of 23.3% on antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Ag-ELISA). On tongue examination, 10.8% were positive (Sikasunge et al., 2008). Studies performed in the Eastern province of Zambia show a TS prevalence of 6.3-11.9% determined by copro-Ag ELISA. Seroprevalence of HCC was 5.8-14.5% based on antigen detection and 33.5-38.5% based on antibody detection (Mwape et al., 2012, 2013).

Figure 3. Endemicity of Taenia solium in 2015 according to WHO3

2.1.4 Risk factors of transmission

Pig to human transmission

Different risk factors are related to the transmission of T. solium to humans. Limited or absent carcass inspection at slaughter, lack of inspection at all levels of the market chain and consumption of inadequately cooked infected pork are significant risk factors for developing human TS (Mwanjali et al., 2013; Carabin et al., 2015).

Human to pig transmission

Risk factors for PC are free-range husbandry systems, contact with human faeces, access to contaminated food such as potato peels and the absence of latrines or use of completely open latrines (Sikasunge et al., 2007; Braae et al., 2015).

Human to human transmission

Low levels of personal hygiene, lack of access to a latrine, unsafe sources of water, lack of knowledge on disease transmission, contaminated vegetables and fruits or direct contact with a tapeworm carrier are known to be important risk factors for developing HCC (Mwanjali et al., 2013; Carabin et al., 2015). Another important risk factor is the lack of health seeking behaviour. People presented with symptoms often fail to seek treatment, both for infection with NCC and TS. This keeps presenting a danger not only to themselves but also their environment.

2.1.5 Burden of the disease

The cysticercosis/taeniasis zoonotic complex is, apart from a Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD), classified as the number one foodborne parasitic disease by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 2014 (FAO and WHO, 2014).

Symptoms of NCC include severe headache, blindness, convulsions and epileptic seizures, and can be fatal. Neurocysticercosis is estimated to cause 30% of all epilepsy cases in countries where the parasite is endemic, and worldwide around 2.8 million disability-adjusted-life-years (DALYs) per year are estimated to be related to cysticercosis (WHO, 2015).

T. solium has an economic impact as well. Cysticercosis reduces the market value of pigs

and makes pork unsafe to eat. The economic burden was assessed in terms of direct and indirect costs caused by NCC-associated epilepsy and potential losses due to porcine cysticercosis. The costs were due to hospitalisation, doctor visitations, drugs and pig losses. A study in Tanzania showed that approximately 5 million USD were spent due to NCC-associated epilepsy and nearly 3 million USD were potentially lost due to porcine cysticercosis (Trevisan et al., 2017). A more recent study by Trevisan et al. (2018) performed in Mozambique estimated a total annual costs due to T. solium cysticercosis of 90 thousand USD (72% linked to human cysticercosis and 28% to pig production losses respectively), however, it is necessary to add that these numbers are possibly an underestimation of the total burden.

2.1.6 Diagnosis

Human cysticercosis/neurocysticercosis

The most optimal test for serological diagnosis of HCC is the enzyme-linked immuno-electrotransfer blot (EITB, 98% sensitivity, 100% specificity) (Tsang et al., 1989). Also an Ag-ELISA (B158/B60 sero-Ag Ag-ELISA) can be used for the detection of HCC in serum (90% sensitivity, 98% specificity) (Brandt et al., 1992). Neuroimaging is necessary for the definite diagnosis of NCC. Computed tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) can provide information about number and location of lesions in the brains and their stage of evolution, but this is not always available in poor regions. In these regions serology, including EITB and antigen detection by ELISA is recommended as an additional major detection method (Gabriël et al., 2012).

Porcine cysticercosis

An easy diagnostic tool for detection of PCC in the field is tongue palpation. It is shown to have a high specificity (100%) but a very low sensitivity (21%) in identifying infected animals (Dorny et al., 2004), as such has been discarded as a potential tool for defining individual infection in favour of more sensitive serological tests. Tongue cysts are more likely to be observed in heavily infected pigs and not so much in mildly infected pigs (Sciutto et al., 1998), implying sensitivity is especially low in cases with low levels of infection. Meat inspection is also considered a possibility. It is specific, but the sensitivity is rather low when only a few cuts are made and cyst loads are low (Dorny et al., 2004). A study performed in Zambia to assess routine inspection methods for porcine cysticercosis showed tongue palpation only detected 16.1% of the cases, and meat inspection 38.7% (Phiri et al., 2006). Full-carcass dissections are considered the gold standard (Chembensofu et al., 2017). Presence of circulating cysticerci antigens can also be detected by the B158/B60 Ag-ELISA, having shown high sensitivities (68–91%) and specificities (67–95%) (Brandt et al., 1992; Dorny et al., 2004; Chembensofu et al., 2017). Cross-reaction of this Ag-ELISA with T.

hydatigena however, results in lower specificities due to false positives and a potential

overestimation of the PCC prevalence (Devleesschauwer et al., 2013; Chembensofu et al., 2017). EITB as a serological test for diagnosing PCC has also been described, but in comparison to the detection of HCC, showed a lower sensitivity (89%) and specificity (48%) (Jayashi et al., 2014). For the identification of suspected cysts, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be used (Gonzalez et al., 2006).

Taeniasis

TS might cause pruritis and proglottids in the faeces (Van De et al., 2014). Abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhoea and other gastrointestinal symptoms are possible, however, usually absent (Murrell et al., 2005).

Currently, microscopical examination of stool samples is the routine method for detection of

Taenia spp. eggs. It has shown to have a high genus specificity (99.9%) but a rather low

sensitivity (52.5%) and the test is not T. solium specific (Dorny et al., 2004). Immunodiagnostic methods such as copro-Ag ELISA and copro-PCR show higher sensitivity (84.5% and 82.7% respectively), although similar to coprological examination, cross-reaction between the antigens of T. solium and T. saginata is present in copro-Ag ELISA (Guezala et al., 2009).

2.2 Control and prevention

T. solium cysticercosis is considered to be a potentially eradicable disease (Schantz et al.,

1993), and recent results from an endemic area in Peru indicate that elimination is possible (Garcia et al., 2016). However, in developing countries such as Zambia, it has been proven to be hard to control cysticercosis. This is due amongst other to lacking financial resources, and much needed social and political acceptance and commitment.

Control options for T. solium can be grouped into measures targeting the intermediate host (pig) and measures targeting the definite host (human).

Measures targeting the intermediate host include improved meat inspection, changes in pig management (the confinement of pigs) and anthelmintic treatment with oxfendazole and/or vaccination of pigs with TSOL18 vaccine.

Measures aimed at the definite host include anthelmintic treatment with praziquantel/niclosamide/albendazole, education on disease transmission and prevention, change of culinary habits and improved sanitation (e.g. toilets, hand washing…).

2.2.1 Measures targeting pigs

Improved meat inspection

In many developing countries, inadequate or non-implemented regulations concerning meat inspection expose consumers to pathogens including zoonotic parasites such as T. solium. Lack of appropriate slaughtering facilities and presence of non-hygienic slaughtering places might cause meat products to deteriorate or become infected. This due to faecal contamination of pig carcasses and unsanitary defecating practices (Joshi et al., 2001). Several strategies including more hygienic slaughter conditions, better slaughter facilities and improved meat inspection in rural areas could play a role in the control of T. solium taeniasis/cysticercosis (Joshi et al., 2003).

A problem concerning meat inspection is that sensitivity to diagnose infection with PCC is very low (see 0), potentially resulting in a serious underestimation of the true prevalence of the infection and allowing the passage of infected carcasses into the food chain (Dorny et al., 2004; Chembensofu et al., 2017).

Teaching farmers how to inspect pig meat for cysticercosis could be an interesting measure to avoid highly infected pork to be traded or eaten after slaughtering pigs at home. Health education could play an important role by informing costumers about the risks related to consumption of infected pork. If consumers refuse to purchase (highly) infected pork, farmers might find motivation in changing management practices or detecting meat for PCC (Edia-Asuke et al., 2014). A study in Mozambique revealed that the majority of both farmers in the villages and pig traders on the markets knew how to detect the parasite using tongue and/or carcass inspection. Moreover, they pointed out that pig farmers and/or buyers select the low infected animals and exclude those who are positive by tongue inspection at village level (Pondja et al., 2010). Often, these heavily infected carcasses then get consumed by those farmers, who end up developing taeniasis and infecting their own pigs.

Processing of meat

Meat preparation also plays an important role as a threat to human health for several pathogens (e.g. moderately cooked meat, meat that is not well cleaned, dirty cooking appliances...). Different steps can be taken in the processing of pork in order to reduce the viability of T. solium cysticerci. Firstly, freezing pork for four days at -5 °C, three days at -15 °C or one day at -24 °C is an effective approach of killing cysticerci (Sotelo et al., 1986). Secondly, salt pickling of pork meat can be an applicable method of avoiding taeniasis infections in humans if the correct concentrations and time requirements are met (Rodriguez-Canul et al., 2002). Next, exposure to gamma radiation at certain doses can potentially reduce and eliminate cysticerci (Verster et al., 1976). At last, different studies demonstrate the importance of heating pork in order to successfully kill cysticerci (Gamble, 1997; Saini et al., 1997; Rodriguez-Canul et al., 2002).

Improved pig husbandry

Pigs are being held in a free-ranging system in many countries where T. solium taeniasis/cysticercosis is endemic. Free range is commonly practiced in small farms mainly in rural areas in Africa, Latin America and South East Asia. Pigs here are fed on grass, brewery, waste products and food leftovers, although most commonly are looking for feed themselves, meaning they are cheap in their nourishment. Besides, they also keep the environment around the households clean. By keeping pigs confined, the life cycle of the parasite could be interrupted since the pigs would not have any more access to human faeces, and therefor will not get infected with PCC (Lekule and Kyvsgaard, 2003).

A study by Thys et al. (2016) revealed that even though there are multiple health risks of free-range pig keeping, people are ready to take this risk for multiple socio-economic reasons. The main problems regarding confinement according to the farmers were related to feed shortage issues, especially during rainy season. Pig owners claimed that pigs were happier and less weak when free roaming, and pigs eating faeces was perceived as an efficient way of getting rid of dirt in the village. However, keeping pigs enclosed would allow a better control of pig feed, and would avoid transmission of diseases.

Although it would be expected that confined pigs have a lower seroprevalence of PCC in comparison to free-roaming pigs, Braae et al. (2014) proved no significant difference between both housing options. This suggests that other factors, such as feeding contaminate waste food or even human stool to pigs, have to be taken into account.

Thomas et al. (2013) studied free-ranging domestic pigs in Western Kenya. It was observed that pigs spent only a small amount of time interacting with the latrine area in their own homesteads (1.3%). However, every degree of contact with human faeces in or around a latrine is sufficient for transmission to occur. Additionally, the probability for pigs to come into contact with human faecal material elsewhere cannot be denied. Another identified problem is that not all homesteads have access to a latrine or not all accessible latrines are completely enclosed and therefor protected from scavenging animals.

Pig vaccination

Vaccination has been identified as a potential new strategy for elimination of T. solium based on a combined approach of chemotherapy of human tapeworm carriers and vaccination of all pigs at risk of infection (Lightowlers, 1999). Different vaccines have been developed in the past, but it is TSOL18 that has been most successful in experimental vaccine trials and field studies (Lightowlers, 2010). TSOL18 (Cysvaxâ) is registered in India and registration in other endemic countries is currently ongoing4.

A field trial in Cameroon revealed that application of TSOL18 vaccine together with a single dose treatment of pigs with oxfendazole achieved the complete elimination of active infection in vaccinated pigs, suggesting that this combined treatment in pigs may have the potential to control T. solium transmission in endemic areas (Assana et al., 2010). Difficulties with the TSOL18 vaccine are the need for a cold chain and finding an appropriate dosing schedule. A mathematical assessment was done by Lightowlers (2013) showing that a schedule of vaccination and treatment with oxfendazole at four-monthly intervals led to the best outcome (the absence of pigs with any cysts at the time of slaughter).

Anthelmintic treatment

Oxfendazole, a benzimidazole, has been proven to be the most effective anthelmintic against muscle cysts, causing no to little side effects (Johansen et al., 2017). The drug is not effective against brain cysts (Mkupasi et al., 2013), however, as pig brains are usually thoroughly cooked, this should not be an issue. Oxfendazole is the only effective, inexpensive, single dose therapy currently registered for the treatment of porcine cysticercosis (Gonzalez et al., 1996). A single dose of 30mg/kg has shown to be more than 95% effective in killing the cysts in the pig (Gonzalez et al., 1997, 1998). Currently, Paranthicâ (oxfendazole 10%) is the only registered anthelmintic for treating pigs with porcine cysticercosis in Morocco, although licencing processes are underway in Tanzania, Uganda, South Africa and West Africa (UEMOA region)4.

4 World Health Organisation, 2017,

2.2.2 Measures targeting humans

Health education

Health education campaigns have been shown to be effective in the prevention and control of many infectious diseases (Sarti and Rajshekhar, 2003) and are an important measure in the control of T. solium (Ngowi et al., 2008). A comprehensive study was carried out in a rural community in Mexico to evaluate the effect of health education as an intervention tool targeting T. solium. Statistically significant improvement concerning knowledge of the parasite occurred. On the other hand, less persistent were changes in behaviour related to transmission (Sarti et al., 1997).

A computer-based education tool “The Vicious Worm” has been designed to target stakeholders providing evidence-based knowledge about transmission, diagnosis, risk factors, prevention and control of T. solium cysticercosis (Johansen et al., 2014). A study revealed a good effect of this tool, showing a significant improvement regarding knowledge immediately after and two weeks after the health education. Besides, a positive attitude towards this tool was present. This outcome suggests it could be a useful health education tool, which should be further assessed and thereafter integrated in T. solium taeniasis/cysticercosis control (Ertel et al., 2015).

In Zambia, a preliminary assessment took place on knowledge uptake in primary school students using the computer based educational tool “The Vicious Worm”. Baseline knowledge (before using “The Vicious Worm” educational component) was assessed in “pre-questionnaires” and was quite high, with an average score of 62%. “Post-questionnaire”, an average score of 73% was obtained, showing this educational tool can be effective in regard to knowledge uptake (Hobbs et al., 2018). A follow-up questionnaire was administered 12 months after this original assessment to evaluate the impact of this tool on knowledge retention in the same primary school students. Increases were shown from “pre” to “follow-up” rounds, while in comparison to “post” data, “follow-“follow-up” scores had decreased. However, key messages for control were still retained by the students (Hobbs et al., 2019).

An increased T. solium knowledge can be obtained by implementing “The Vicious Worm” tool in both short- and long-term. However, it is important to keep in mind that increased knowledge does not always lead to behavioural changes (Sarti et al., 1997; Arlinghaus et al., 2018). Health education can be an effective control strategy leading to permanent outcomes, but requires active participation of the community (Sarti and Rajshekhar, 2003).

Improved sanitation

Key to the propagation of the T. solium lifecycle is the contact between pigs and contaminated human faeces. Open defecation is a very important risk factor for porcine cysticercosis. As long as pigs have access to contaminated human faeces, porcine cysticercosis will occur and the cycle will proceed. Use of well-constructed latrines and correct management of wastewater are highly important practices to prevent the intermediate host from becoming infected (Okello and Thomas, 2017). A study in rural Goa showed that individuals lacking in personal hygiene, such as non-usage of soap for hand washing after defecation, were twice at risk of becoming contaminated with cysticercosis, whilst this association was not seen with taeniasis (Vora et al., 2008). While in theory the key role of sanitation in the blocking of transmission is clear, the practical implementation is not always as straight forward because of different reasons. Thys et al. (2015) found that latrines were not built in every household due to convenient use of existing latrines in the neighbourhood,

privacy reasons and especially men were reluctant mainly because of social taboos concerning sharing of latrines with in-laws and grown-up children of the opposite gender.

Anthelmintic treatment

Praziquantel (PZQ) and niclosamide (NCS) are the safe and effective drugs of choice for the treatment of taeniasis. The efficacy of PZQ and NCS is around 95% and 77.9% respectively (Bustos et al., 2012).

PZQ has a taenicidal and cysticidal effect. The single dose of PZQ at 5-10 mg/kg used to treat T. solium TS may induce seizures in patients with unrecognised neurocysticercosis (Torres, 1989; Flisser et al., 1993). This is unlikely since the dose used for treatment of TS is low, however problems may occur during treatment for schistosomiasis where a dose of 40mg/kg is required (Braae et al., 2016).

NCS has a lower efficacy in comparison to PZQ, and only has a taenicidal effect. NCS does not cross the blood-brain barrier and since there is no cysticidal effect, it will not kill brain cysticerci and thereby cause an inflammatory reaction. Therefore it is safer to use (Garcia et al., 2003b).

Usage of triple doses of albendazole (400mg given over three consecutive days) or mebendazole (500mg given over three consecutive days) has been proven effective to cure all Taenia species (Steinmann et al., 2011), however is less practical to implement.

2.3 Preventive chemotherapy

Preventive chemotherapy (PC) of tapeworm carriers is an important intervention tool and involves the distribution of anthelmintic drugs to populations at risk. There are different ways to implement PC (Gabrielli et al., 2011; Thomas, 2015):

• Mass drug administration (MDA): treatment of the entire population of a predefined area at consistent intervals, regardless of clinical status.

• Selective chemotherapy (track and treat): treatment of suspected infected or positive tested individuals.

• Targeted chemotherapy (focus group administration): treatment of specific risk groups, irrespective of clinical status.

2.3.1 Mass drug administration (MDA)

MDA is based on the concept of preventive therapy, in which (sub)populations are offered treatment without individual diagnosis. It is a way to deliver safe and inexpensive necessary medicines and is mostly performed as treatment to every member of a defined population or every person living in a defined geographical area at approximately the same time and often at repeated intervals. Firstly, attempting to improve global health, MDA is administered in endemic areas to prevent and lighten symptoms and morbidity. Secondly, MDA is conducted to reduce transmission, hoping to improve global health. According to WHO, MDA is the recommended strategy to control or eliminate several NTDs such as soil-transmitted helminths (STH), Schistosomiasis, Lymphatic filariasis, Leishmaniasis, Onchocertiasis et al (Webster et al., 2014).

MDA can be administered as a stand-alone intervention or combined with other measures to control T. solium infections.

Several studies have demonstrated a reduction in taeniasis prevalence within two years, however the effect on HCC and PCC has been more variable (Thomas, 2015).

Allan et al. (1997) provided mass treatment of the human population with NCS in two rural villages in Guatemala where T. solium was endemic. A significant decrease of human taeniasis prevalence was noted 10 months after the treatment (35% before, 1% after). Similarly, the seroprevalence of antibodies to cysticercosis in pigs decreased (55% before, 7% after).

From 1991 to 1996, Sarti et al. (2000) performed a study in Mexico showing promising results regarding mass chemotherapy with a single dose of PZQ 5mg/kg as a measure to control taeniasis and cysticercosis. After treatment, a reduction of 53% and 56% for human TS was seen after six and 42 months respectively. Late-onset general seizures decreased 70% suggesting a decrease in human neurocysticercosis at 42 months. In conclusion, an impact of mass chemotherapy against TS to control CC both in short and long term was shown.

A study performed by Braae et al. (2017) showed a significant reduction in copro-Ag prevalence of TS obtained by combining “track and treat” of TS with school-based MDA with PZQ. It also demonstrated that annual MDA was significantly more effective in reducing taeniasis copro-Ag prevalence in comparison to a single MDA.

However, mass chemotherapy has its challenges. Although the studies mentioned above might sound promising, Kyvsgaard et al. (2007) demonstrated that by using a single MDA, infection rates quickly revert to pre-treatment level after an initial drop in occurrence of TS and PCC. This outcome leads to the recognition that mass treatment could play an important role in control programmes if followed by more long-term engagements (e.g. health education, pig vaccination, use of latrines etc.). Therefor it must be noted when applying this method in practice as a single control option, it will not be successful, predominantly due to the increased risk of reinfection through the pig intermediate host, as well as from the environment (Braae et al., 2017).

Additionally, it is necessary to consider the sustainability of using MDA as a treatment strategy. Since the prevalence is low in most endemic areas, unnecessary treatment of large amounts of people is performed. This amount expands the more the prevalence drops. Lastly, anthelmintic resistance has been increasingly observed in livestock and raises awareness of potential resistance towards drugs commonly used in MDA programs. There is no conclusive evidence of drug resistance among STH yet (for which e.g. mebendazole is used), but the possibility has to be taken into consideration (Vercruysse et al., 2011). For PZQ, widely used in MDA programmes against schistosomiasis, evidence of resistance remains controversial (Abaza, 2013; Vale et al., 2017). At the moment, limited drugs are available with regard to treating T. solium infections and extensive numbers of treatments are being carried out in MDA strategies, making existing control programs extremely vulnerable should anthelmintic resistance occur (Prichard et al., 2012; Vercruysse et al., 2012).

2.3.2 “Track and treat”

“Track and treat” implies testing individuals for cysticercosis or taeniasis and subsequently treating them. This is a hypothetical human-targeted intervention, however, this system is opposed due to the absence of a low cost and sensitive diagnostic test to use in the fields (Mwape and Gabriël, 2014).

Questionnaire based detection based on self-diagnosis of TS might be a potential tool for tracking and treating infected individuals (Flisser, 2006), however, more studies need to be performed in order to determine the success-rate of this tool.

A single intervention of human track and treat is considered the most effective, but it is still a hypothetical one. First, a more optimal diagnostic test will be necessary to identify tapeworm carriers.

2.3.3 Focus group administration (FGA)

FGA entails the identification of specific risk groups in a certain population, and treatment focussing on this specific risk group of individuals. It could for example be targeted at TS cases including close contacts or to TS cases within a certain risk area surrounding an infected pig (ring treatment, see below).

Pawlowski (1991) discussed why chemotherapy based on foci is not yet implemented adequately. A focus could be a T. solium-infected or suspected case, a household with recent case of epilepsy in family or cysticercosis in pigs, or a group of houses or a village with high rate of cysticercosis in pigs. All people with suspected T. solium taeniasis in a focus should be treated. The main problem is the identification of T. solium taeniasis foci. For example, TS could be associated with a certain age in one community but possibly not in another (Madinga et al., 2017). Significant spatial clustering of TS and PCC has been observed which suggests that identifying these foci is necessary (Raghava et al., 2010; Pray et al., 2017; Ng-Nguyen et al., 2018). To detect these risk groups, a time-consuming large-scale survey should take place every time an FGA is administered. Alternatively, in order to identify these foci, existing data from medical services regarding TS cases and late onset epilepsy patients could be used. On the other hand, tongue palpation or veterinary data based on high prevalence of PCC in small sites or farms that frequently supply pigs with PCC could also be used.

As a consequence, treatment should then be presented within these geographical focal points to all known or suspected carriers with the prospective to undertake an MDA program within high-risk populations within the foci (e.g. workers within the meat industry) (Pawlowski, 2008).

Ring treatment

This targeted approach is a type of FGA, based on the assumption that pig and human disease are spatially related and presumably found in close proximity to one another. It was developed as an alternative to mass anthelmintic treatment (Pray et al., 2017).

Targeted intervention in a defined geographic radius around infected pigs has recently been evaluated by O’Neal et al. (2014) in Peru. By tongue palpation, all pigs of the intervention village were surveyed for PCC every four months. Every time a heavily infected pig had been found, a focused ring screening and treatment of human (and pigs) within a 100-meter radius of these pigs was performed. A 41% reduction in seroincidence in the intervention village was detected after one year compared to baseline, while the seroincidence in the control village remained unchanged. At study end, the prevalence of taeniasis was nearly four times lower in the intervention village compared to the control village. This showed that this ring treatment strategy for T. solium within these high-risk foci might be an effective and practical control intervention in rural endemic settings.

Another study performed by O’Neal et al. (2012) revealed that inhabitants living within 100 meters of a tongue-positive pig had a prevalence of taeniasis that was more than eight times higher compared to inhabitants living outside this range.

A first study performed by Pray et al. (2016), also in Peru, showed that pigs spent a median average of 69.8% (IQR: 52.3 - 82.4) of their time within 50 meters of their homes and spent approximately 30 minutes per day interacting with human defecation areas inside these 50-meter rings. Outside this peri50-meter, pigs spent only seven minutes per day interacting with human stool. Pigs spent a median of 82.8% (IQR: 73.5-94.4) of their time roaming within 100 meters of their homes, however, considerable heterogeneity existed among pigs as the percentage of time spent inside this radius fluctuated between a minimum of 26% to a maximum of 99% for different pigs. Of the total time pigs spent interacting with open defecation, 93% happened within 100 meters of their residence.

A second study performed in Peru (Pray et al., 2017) stated that pigs were 4.56 times more likely to be infected with at least one cyst if they were residing less than 50 meters from a human infected with TS in comparison to those residing further than 50 meters away. Pigs living more than 50 meters from tapeworm carriers did not have significantly greater chances of PCC. However, the severity of cyst burden was not related with proximity to tapeworm carriers.

The articles stated above support the decision to treat humans and pigs based on their proximity to other infected individuals. Screening for taeniasis within a defined geographic radius around heavily infected pigs, followed by treatment of identified carriers, can reduce transmission of T. solium in rural endemic settings.

It is important to note that the studies mentioned above are based in Latin America; making it uncertain whether or not these findings are similar in Sub Saharan Africa. There is no previous data collected on pig roaming behaviour and ranges in this area, and therefore no proof that these results may be extrapolated to the situation in SSA.

The potential advantages of using ring treatment instead of MDA are the reduced unnecessary treatments, the higher likelihood of participation by the local people, a lower number of people that need testing and treatment and the prospect of reduced workload.

Ring treatment may require people to be tested before treatment, but could also be carried out, for example, based on tongue palpation of pigs where neighbouring people are subsequently being treated.

Alexander et al. (2011) analysed the cost-effectiveness of MDA versus selective treatment of taeniasis cases in India in 2008. Randomly selected compliant individuals were screened for taeniasis using copro-Ag ELISA and positive cases were treated with 2g NCS. The cost per treated case was determined and then applied for populations with different prevalence and compared to the cost per case treated utilising an MDA approach without pre-screening. The authors concluded that an MDA approach was the most cost-effective strategy at all levels of prevalence. Selective treatment of taeniasis cases might be more cost-effective if alternative identification procedures would be used.

Of all treatment strategies mentioned above, MDA is still mostly implemented due to inconveniences correlated with FGA and the “track and treat” approach. Nonetheless, it must be noted that MDA as a single control option will not be effective, mainly due to the high risk of reinfection via the intermediate host, as well as from the environment (Kyvsgaard et al., 2007; Braae et al., 2017). The persistence of taeniasis cases illustrates the need of a One-Health approach for effective control.

3 Objectives

Considering the limitations of mass drug administration (MDA), the alternative ring treatment strategy is currently being implemented as a system to control T. solium. The size of the ring (50 meters) used in the CYSTISTOP-project (see 4.1) has been determined based on Latin American conditions, which need to be verified in other settings.

Therefore, the main objective of this study is to contribute to the determination of the size of the ring in order to successfully eliminate new cases infected with TS and PCC (and prevent HCC infections) in the Katete District, Zambia.

In order to be able to do this, it is necessary to analyse the roaming ranges of pigs and define the open defecation areas to link pig movement to new positive individuals and their open defecation.

The specific objectives are:

• To observe the roaming range of rural pigs living in the participating communities using GPS tracking devices.

• To assess and map open human defecation areas.

• To observe and evaluate the presence of free roaming pigs in human open defecation areas.

• To evaluate differences regarding pigs’ roaming range and interaction with human open defecation areas in dry versus rainy season and assess whether there is a need to adjust the ring strategy depending on season or not.

4 Material and Methods

4.1 CYSTISTOP

In order to evaluate the best future strategy for elimination of T. solium in Sub Saharan Africa, a large-scale project named “CYSTISTOP” (collaboration between the University of Zambia, the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp and the University of Ghent) has been set up. This is a prospective community-based study, crucial in determining whether elimination on a short term (through integrated measures) or through long-term disease control (single measures) with possible elimination of T. solium in a highly endemic area in Zambia is cost-effective. This interventional field study consists of three study arms: A Control study arm (C), which implements a single control option, an Elimination study arm (E), which combines multiple control options, and a negative control study arm.

The intensive intervention period of the elimination study arm has been finalised and is now followed by an active monitoring phase. During this phase blood samples of pigs are collected every six months to detect new porcine cysticercosis infections. Simultaneously, human stool samples are collected and examined for taeniasis.

Besides taking samples, there are additional tools implemented to monitor and control the re-entry of tapeworm carriers/infected pigs. All new pigs entering the study area are treated with oxfendazole. Additionally, when a positive individual (pig or human) is detected during the six-monthly samplings, all humans and pigs living within a 50-meter radius of the positive individual are treated with niclosamide and oxfendazole, respectively (ring treatment). This allows monitoring of new incoming cases and helps maintaining the elimination status.

My master thesis is conducted in the framework of this CYSTISTOP-project and contributes to the assessment of the suitability of the 50-meter radius of the ring treatments. This treatment within the 50-meter radius has never been evaluated in this area and there is no previous data showing the effectiveness and accuracy of this limited ring treatment in order to effectively treat new T. solium infections.

In April 2019 researchers from the CYSTISTOP-project completed the first part of this research in Zambia in April, and I repeated this in October during a four-week student exchange between the Department of Veterinary Public Health and Food Safety (Ghent University, Belgium) and the Laboratory of Clinical studies (University of Zambia, Zambia), participating in the operational activities of the CYSTISTOP-project, through performing a field study in Zambia during the dry season. All collected data will be combined and analysed in this master thesis.

4.2 Study site and population

4.2.1 Study area and population

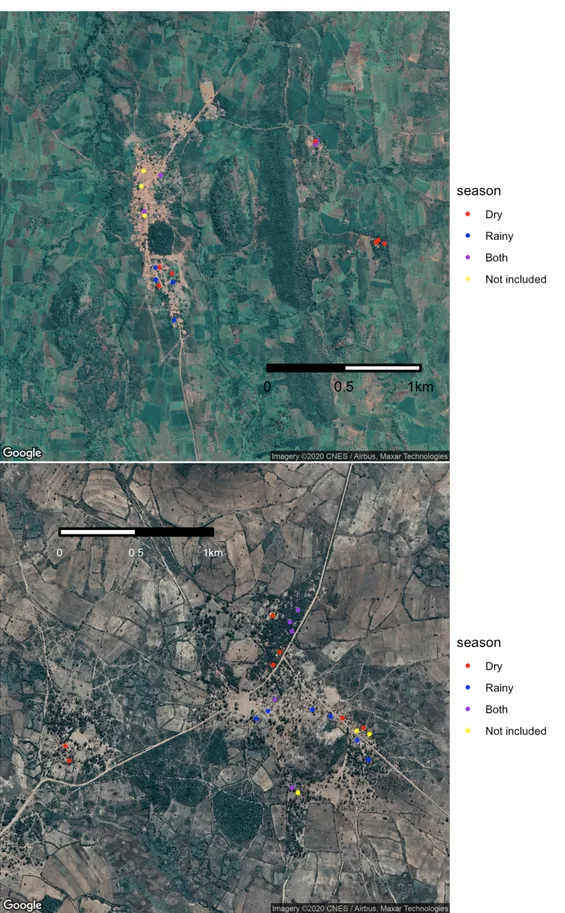

The study took place in two communities in the Katete district, in the Eastern Province of Zambia (Fig. 4). The Nyembe neighbourhood community was selected for the elimination study arm. This community consists of five villages, two farms and around 1210 people. The Chimvira neighbourhood community was selected for the control study arm and consists of 11 villages and around 1470 people.

Figure 4. Map of study site: Nyembe and Chimvira communities in Katete District, Eastern province

Zambia

The climate is tropical with two main seasons. The mean rainfall varies from 500 to 1200mm per year with temperatures above 20 °C most of the year. GPS tracking performed in the “rainy-season” took place in the study villages in April 2019, which is at the end of the rain season (November-April). “Dry-season” tracking took place in the same villages in October 2019, when dry season is coming to an end.

The number of pigs present is variable and difficult to determine precisely as there is a constant flow of pigs due to purchasing new pigs and selling others, slaughter for consumption, losses due to diseases and more.

In April 2019, Nyembe had 13 pig keeping households with eligible pigs (see 4.2.3) and Chimvira consisted of 14 pig keeping households that qualified. In October 2019, Nyembe consisted of 12 pig keeping households with eligible pigs and Chimvira had 14 suitable pig keeping households. The average number of eligible pigs per pig keeping household was 3.5 (range: 1 to 14).

Recent studies performed by Mwape et al. (2012, 2013) in this area indicated a human cysticercosis seroprevalence of 5.8-14.5% based on antigen detection, 33.5-38.5% based on antibody detection and a taeniasis prevalence of 6.3-11.9% determined by copro-Ag ELISA, ranking among the highest in the world. Chembensofu et al. (2017) found a high occurrence of porcine cysticercosis in this area. Fifty-six percent of all selected pigs had cysticerci on full

body carcass dissection. A prevalence of 53% was found by Ag-ELISA and 11% of all infected pigs could be diagnosed based on tongue palpation.

4.2.2 Sample size

Determined by the availability of GPS devices, a total number of 48 pigs (12 pigs per community per season) was chosen in order to explore differences in home-range areas by season. Considering the explorative nature of this study and the number of pig keeping households in the villages this was determined sufficient.

4.2.3 Study pigs

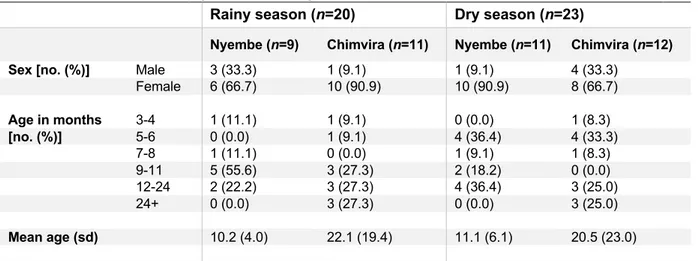

Pigs, of the local Nsenga breed, were mainly free ranging during their life span and typically kept by a smallholder or farmers (Table 1). Pigs could be confined for part of the day or year but were not housed or confined their entire life span. We attempted to enrol at least one pig from each village, thereby achieving adequate spatial representation of pigs throughout the villages. If multiple pigs were captured from one village, we mainly tried to include pigs originating from different pig keeping households, and preferably from a different sex and age category.

Inclusion criteria

• Free roaming, not enclosed in a corral during the day at the time of recruitment; • Owner willing to allow pig to participate in all aspects of the study;

• Living within the study villages; • Aged two months or older;

• Not late-term pregnant (in third trimester) or lactating sows.

Exclusion criteria

• Pig continuously enclosed;

• Owner unwilling for pig to participate in some or all aspects of the study; • Living outside of the study villages;

• Younger than two months of age;

• Late-term pregnant (in third trimester) or lactating sows.

Table 1. Overview pig characteristics

Species Porcine (Sus scrofa domesticus) Breed Local Nsenga breed

Source Owned by farmers and holders in Katete district Age 2-71 months at time of GPS applying

Gender Male or female

4.3 GPS tracking

4.3.1 Study design

Global Positioning System (GPS) devices were used to track pig roaming ranges in the two participating communities in the Katete district, in the Eastern Province of Zambia, in both rainy and dry season.

During both interventions, around 12 pigs were selected in both the Nyembe and respectively the Chimvira neighbourhood (representative for the population: different age groups and owners) and GPS tracking devices were attached. Their movements were tracked continuously during a three-to-four-day period using small GPS data loggers. After releasing the pigs, the GPS location was logged at 60-second intervals. During the tracking period the pigs got visually inspected from a distance on a daily base to ensure that the harnesses remained properly in place, and pigs were recaptured in order to adjust harnesses if found necessary. After collecting all necessary data, pigs were recaptured, and harnesses were removed. Data originating from the GPS device was imported (see 4.5.1) and harnesses were thoroughly washed and disinfected.

Pigs were given an individual code consisting of three parts:

1. Three letter abbreviation of the community (NYE for Nyembe, CHV for Chimvira); 2. Digit 2 followed by an underscore in case of tracking during dry season (e.g.

NYE2_), in case of tracking during rainy season no digit nor underscore was used;

3. Digits corresponding with the number of the GPS used on that specific pig (e.g. NYE2_3).

4.3.2 GPS application on the pigs

Pigs were restraint manually, standing upright, held by the ears and hind legs and restrained firmly. For very large or aggressive pigs that could not be restrained safely this way, a snout snare designed specifically for pigs was used. The soft cable loop of the snare got placed behind the teeth and tightened over the upper jaw. The snare operator kept tension on the snare and released it as soon as the operations were completed. Regardless of the method used to restrain the pig, the principle investigator, a veterinarian, continuously monitored the pigs for any signs of excess stress levels and released the pig if necessary.

Once eligible pigs were captured, a harness was applied. The harnesses were available in six different sizes (S to XXXL) and were made out of adjustable nylon made especially for swine. For application, the pig needed to stand in an upright position. The longest strap went behind the front legs and the shorter strap went in front of the front legs, with the square part of the harness in between the front legs. The GPS case was well placed on top of the pig before the harness was closed. The longest strap was closed first, making sure two fingers would still fit between the pig and the strap. Lastly, the shorter strap was closed correspondingly. The pigs’ ability to breath easily and have a free range of motion had to be assured (Fig. 5).

Subsequently, one “iGotU” portable GPS receiver (MobileAction Technology, New Taipei City, Taiwan) was turned on, placed in a waterproof case (HPRC 1100, Plaber, Vicenza, Italy) and secured to the nylon harness on the nape of the pig (Fig. 6). The total duration of attaching these devices was less than five minutes. For the full Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) on GPS tracking see Appendix I.

All information concerning pig identification, start and end times of GPS tracking, daily check-ups and other got recorded on “GPS-tracking of pigs – pig enrolment” files.

Figure 5. Side view (left) and top view (right) of correctly applied harness with GPS in waterproof case

Figure 6. GPS receiver secured inside waterproof case (left); correctly closed case (right)

4.4 Human defecation mapping

Human defecation areas were mapped with the help of local people with knowledge of common open defecation areas. Local community leaders surveyed inhabitants of every village on where the usual areas for open defecation were and pointed out known communal defecation sites. Household defecation practices were assessed and the EpiCollect5 application5 was used on tablets to GPS locate the indicated areas. The villages were

inspected (roads, communal areas, bushes…) and when human faeces were identified, the location was saved with the use of the EpiCollect5 application.

5 EpiCollect5 Data Collection User Guide, https://epicollect5.gitbook.io/epicollect5-user-guide/, last

4.5 Mapping and statistical analysing

4.5.1 Download data from GPS devices and the EpiCollect5 application

GPS devices

The data from the GPS tracking devices was imported on a computer using the software program @trip6. Then, the imported data was exported to CSV files and the data from @trip

was cleared. At last, the GPS tracking devices were reformatted.

EpiCollect5 application

The collected open defecation data saved in the EpiCollect5 application on the tablets used in the field was uploaded to the EpiCollect server every evening and later downloaded as CSV files.

4.5.2 Data cleaning

With regard to avoiding bias due to the chase and capture of pigs, the first hour and final 30 minutes of tracking time of each pig were removed, as well as points that were recorded before, during and after any necessary harness adjustments. If necessary, additional tracking time was removed corresponding with circumstances written down on the “GPS-tracking of pigs – pig enrolment” files, such as an accidental early start of tracking.

4.5.3 Data analyses

All collected data was analysed using @trip6, R version 3.6.27, Rstudio version 1.2.50338 and

Microsoft Office Excel version 16.369.

All information regarding tracked pigs (obtained from the “GPS-tracking of pigs – pig enrolment” files) was merged into Excel files.

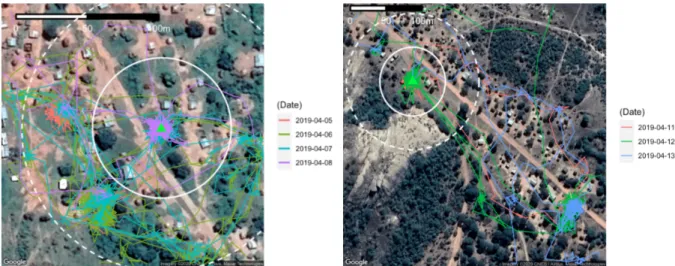

The data analysis was performed in R7. Firstly, all obtained tracking points were cleaned

individually per pig (see Data cleaning) and tracked time per pig was calculated. Then, since the home coordinates of pigs did not always correspond with the saved coordinates of the owners’ household, home coordinates of every tracked pig were determined individually by localising the central point of a circle with 10-meter radius where every pig spent most of its time. Thereafter, individual maps of GPS tracks were created for every pig and different sizes of rings were added. Afterwards, the number of revisits in every ring was determined and the proportion of time spent in every ring was calculated.

For determining the contact between pigs and ODF areas, all collected spots were mapped and an arbitrarily radius of eight meters around each tracked open defecations spot was created in R to define the OD site. Subsequently, analyses for every pig individually were performed to determine the proportion of time each pig spent in contact with ODF sites located in their 50- and 250-meter radiuses, and in total.

6 @trip, https://www.a-trip.com/, last consulted March 2020.

7 R Project for Statistical Computing, https://www.r-project.org/, last consulted March 2020.

8 RStudio Team (2019). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA URL

http://www.rstudio.com/, last consulted March 2020.

4.6 Ethical approval

Approval for the study was granted by the UNZA Biomedical Research and Ethics Committee (004-09-15, covering human and animal part); the Ethical Committee of the University of Antwerp, Belgium (B300201628043, EC UZA16/8/73, human part) and the Ross University School of Veterinary Medicine’s Institutional Review Board (human part). Every participant was informed about the objectives, the procedures and the potential risks and benefits of the intervention. Oral permission from all pig owners was obtained prior to handling pigs and applying GPS devices, and participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time in case they favoured to do so.

5 Results and discussion

5.1 Pig population and roaming ranges

5.1.1 Pig population

We enrolled a total of 48 pigs to GPS track, 24 in each season. Two pigs were excluded from the analysis because of (early) device loss (one pig from each community). Throughout the daily follow-up inspections in the rainy season, it was noted that three pigs in Nyembe were observed in their corrals. Analyses of their GPS data confirmed this observation (Fig. 7). Since free roaming was an eligibility criterion, these pigs were excluded.

Figure 7. GPS tracks for pig NYE14, NYE15 and NYE17. White circle represents a 5-meter radius,

black circle a 50-meter radius

This led to a final analytic sample of 43 pigs: 20 in the rainy season and 23 in the dry season. Of the 20 pigs tracked in the rainy season, none were tracked during the dry season. We were able to track a pig originating from the same household during both seasons for nine households (four in Nyembe, five in Chimvira). Although we attempted to avoid including pigs from the same household during a tracking, due to field circumstances, two pigs were originating from the same household in rainy season, and two pigs were originating from the same household during dry season. All other pigs enrolled were originating from different households. In the rainy season, 19 different pig keeping households had at least one pig that was successfully tracked out of 27 eligible pig keeping households and in the dry season, 22 out of 26 pig keeping households with eligible pigs had at least one pig that got tracked (Fig. 8).

A first important limitation of this study becomes clear when looking at the GPS tracks from the excluded study pigs mentioned above (Fig. 7), demonstrating imprecision in GPS points caused by signal disruption. All three of these pigs were originating from the same farm, and the size of this corral amounted approximately four meters in diameter, while GPS points of these enclosed pigs were logged in an area of 20 meters in diameter or more. This clearly leads to believe that there is a lot of disruption in the GPS signal and as a consequence, potentially reduces the accuracy of time spent within certain observed roaming ranges. However, major disruptions are less likely, and the obtained data is still a good indicator of pigs’ roaming behaviour in the included villages.

Figure 8. Satellite image of Nyembe (top) and Chimvira (bottom) locating all households (HHs) with pigs tracked. The blue dots represent HH with pigs tracked during rainy season and the red dots represent HH with pigs tracked during dry season. Purple dots represent HH with pigs tracked during both seasons and yellow dots represent eligible pig keeping households with no pigs tracked. Satellite images: Imagery © 2020 CNES/Airbus, Maxar Technologies.

All analyses performed below are based on the remaining 43 pigs that were considered eligible for this study and characteristics of these tracked pigs are summarised in Table 2.