(DE)CONSTRUCTING FAIR TRADE

Aantal woorden: 24472Stamnummer: 01200468

Promoter: Prof. Dr. Brent Bleys

Masterproef voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van: Master in de algemene economie

CONFIDENTIALITY AGREEMENT

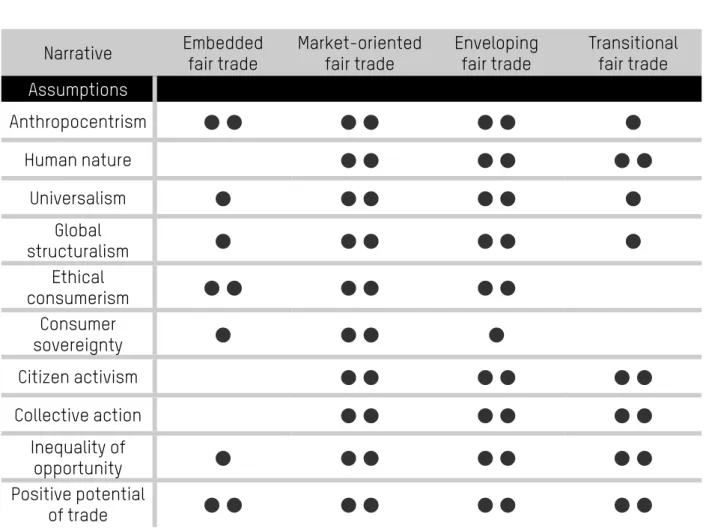

Permission

I declare that the content of this Master’s Dissertation may be consulted and/or reproduced, provided that the source is referenced.

Masterproef voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van

Master in de algemene economie

In samenwerking met

Fair Trade Advocacy Office

ABSTRACT

This research provides a holistic description of the Fair Trade philosophy and its movement. Such an overview was up until now absent in the research body on Fair Trade. Remarkably, numerous articles have already been written evaluating the impact of the fair trade movement without a full understanding of Fair Trade, leading to an overall underestimation of the movement’s performance. Through the use of narrative research, Fair Trade is (de)constructed, recognizing its unifying characteristics while also acknowledging the diversity of the movement. To that end, Fair Trade is stripped to its assumptions, values and theories of change. Additionally, four archetypical narratives are formulated, representing diverging interpretations of the Fair Trade philosophy.

It is concluded that Fair Trade for the most part has a broad and critical view on the global trade system. At the same time, it presents multiple strategies to effectuate change. Certain iterations challenge the current status quo while others seem to perpetuate it. This diversity partially explains the movement’s resilience in managing to survive and thrive in different ideological and cultural contexts.

SAMENVATTING

Dit onderzoek biedt een holistische beschrijving van de fairtradefilosofie en haar beweging. Een dergelijk overzicht ontbrak tot nu toe in het onderzoek over fair trade. Opmerkelijk genoeg is reeds veel onderzoek uitgevoerd waarin de impact van de fairtradebeweging wordt geëvalueerd zonder dat fair trade in zijn volledigheid wordt benaderd, wat leidde tot een onderschatting van de impact van de beweging.

Op basis van narratief onderzoek wordt fair trade ge(de)construeerd, waarbij zowel de eenheid als de diversiteit van de beweging wordt erkend. Daartoe worden de assumpties, waarden en veranderingstheorieën van de fairtradefilosofie beschreven. Daarnaast worden vier archetypische narratieven opgesteld die een inzicht geven in de uiteenlopende interpretaties van de fairtradefilosofie. We concluderen dat fair trade een brede en kritische kijk heeft op het mondiale handelssysteem. Tegelijkertijd presenteert de beweging meerdere strategieën om wijzigingen aan te brengen in dat voornoemd systeem. Sommige interpretaties stellen de huidige status-quo ter discussie, terwijl andere deze eerder lijken te bestendigen. Deze diversiteit verklaart voor een deel de veerkracht van de beweging waardoor het in staat is te overleven en zelfs te gedijen in verschillende ideologische en culturele contexten.

FOREWORD

This research is a reflection of my six-year long journey into Fair Trade. I started out as a volunteer: cleaning, stocking, selling, campaigning and educating for Oxfam-Wereldwinkel Gent-Centrum. As my interest in trade began to grow, I wrote my first thesis in European Union-studies on environmental provisions in European Union trade policy. After a voluntary internship at Oxfam-Wereldwinkels working on competition policy, monitoring instruments and trade agreements, I got the opportunity to work for the Fair Trade Advocacy Office. I currently am policy and advocacy officer at Oxfam België-Belgique. Along the way I met many people who influenced my thinking on Fair Trade.

I have to thank the team at Oxfam-Wereldwinkel Gent-Centrum for their warm welcome into the world of Fair Trade. Ferdi De Ville, Deborah Martens, Jan Orbie provided me with the academic basis for conducting research on (fair) trade, for which I am very grateful. I also ought to thank the (former) staff of the Fair Trade Advocacy Office Peter Möhringer, Fabienne Yver and the interns who were present at that time who helped me develop my ideas on Fair Trade. I owe a debt of gratitude especially to Sergi Corbalán (executive director of the Fair Trade Advocacy Office) who mentored me, and without whom this research would not have been possible. His views on Fair Trade still inspire me today. Furthermore, I would like to thank my close colleagues Stefaan Calmeyn, Helga Duhou, Thomas Mels, Sarah Vaes, Bart Van Besien and Tom Ysewijn for welcoming me to their team and the numerous insightful talks we had on Fair Trade.

Many thanks to Thomas Vanlerberghe for proofreading my work.

Finally, I have to thank my parents Ronny Matthysen and Hildegard van Looveren for their enduring support during my scholar years and Celien Vermeiren for listening to me go on and on about Fair Trade. That could not have been easy.

This thesis is dedicated to fair trade coffee, the fuel without which it would not have been possible writing a thesis while at the same time being full time employed.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1. Introduction to the research subject ...1

1.1. Fair Trade as a philosophy ...1

1.2. Fair Trade and similar signifiers ...2

Part 1 Research Design ...4

Chapter 2. Problem statement and research objective ...5

2.1. Problem statement ...5

2.1.1. Research questions...5

2.1.2. Delineation ...5

2.2. Research objective ...6

2.2.1. Scientific relevance ...6

2.2.2. Societal relevance ...8

Chapter 3. Methodology and operationalization ...9

3.1. Operationalization ...9

3.1.1. Working definition of Fair Trade ...9

3.1.2. The three building blocks of Fair Trade ...11

3.2. Methodology ...12

3.2.1. Research paradigm: constructivism ...12

3.2.2. Research method: narrative research ...13

3.2.3. Data collection methods: document analysis and interviews ...13

3.2.4. Data analysis method: Hernadi’s hermeneutic triad ...15

3.2.5. Data reporting: research outline ...16

Chapter 4. Research context and literature study ...17

4.1. Fair Trade research categories ...17

4.2. Some examples ...18

Part 2 Deconstructing Fair Trade ...23

Chapter 5. Fair Trade’s descriptive assumptions ...24

5.1. Classification of the assumptions ...24

5.2. Description of the foundational assumptions ...26

5.2.1. Anthropocentrism ...26

5.2.2. Human nature ...27

5.3. Description of catalytic assumptions ...28

5.3.1. Universalism ...28

5.3.2. Global structuralism ...28

5.4. Description of the operational assumptions ...29

5.4.1. Ethical consumerism ...29

5.4.2. Consumer sovereignty ...30

5.4.3. Citizen activism ...31

5.4.4. Collective action ...32

5.5. Description of topical assumptions ...34

5.5.1. Inequality of opportunity ...34

5.5.2. Positive potential of trade ...34

5.6. Summary ...35

Chapter 6. Fair Trade’s prescriptive values ...37

6.1. Classification of the values ...37

6.2. Description of the values ...37

6.2.1. Primary value of the fair trade value system: justice ...37

6.2.2. Secondary values of the fair trade value system ...38

6.2.3. Tertiary values of the fair trade value system ...40

Chapter 7. Fair Trade’s programmatic theories of change ...41

7.1. Classification of the theories of change ...41

7.1.1. A value-based approach to programmatic theories ...41

7.1.2. Commonalities of the theories of change ...42

7.1.3. Differences between the theories of change ...42

7.2. Description of the theories of change ...43

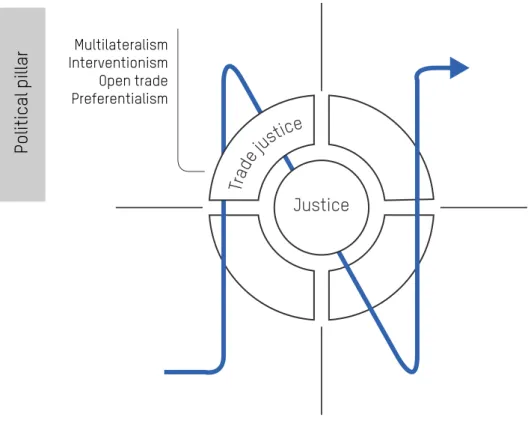

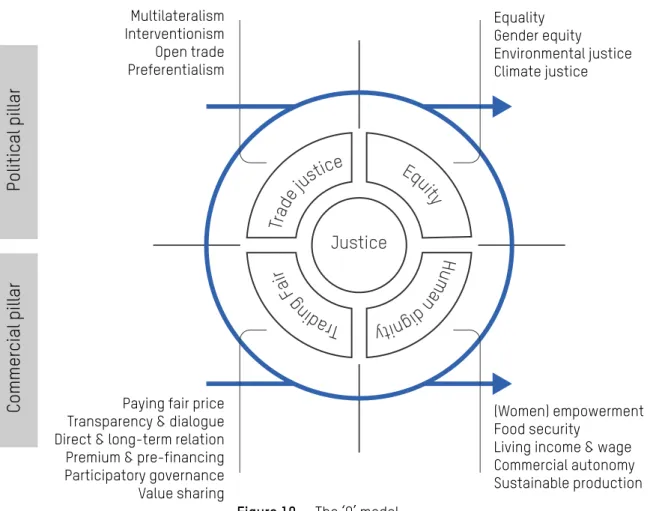

7.2.1. The ‘=’ model ...43

7.2.2. The ‘inverted Z’ model ...45

7.2.3. The ‘N’ model ...47

7.2.4. The ‘U’ model ...50

Part 3 Constructing Fair Trade ...53

Chapter 8. The embedded fair trade narrative ...55

8.1. Setting: Neoliberal hegemony ...55

8.2. Conflict and character: The quadruple thank-you ...55

8.3. Plot: Business as usual...57

Chapter 9. The market-oriented fair trade narrative ...58

9.1. Setting: Hostile environment ...58

9.2. Conflict and character: Hand in Hand instead of the Invisible Hand ...59

9.3. Plot: A business alternative ...60

Chapter 10. The enveloping fair trade narrative ...61

10.1. Setting: Policy playground ...61

10.2. Conflict and character: A political struggle ...62

10.3. Plot: A political alternative ...63

Chapter 11. The transitional fair trade narrative ...64

11.1. Setting: Inherent contradictions ...64

11.2. Conflict and character: War of position ...65

11.3. Plot: A political inevitability ...66

ABBREVIATIONS

CSO Civil Society Organization EFTA European Fair Trade Association FI Fairtrade International

FLO Fairtrade Labelling Organizations (FLO) International e.V. IFAT International Federation for Alternative Trade

NEWS! Network of European World Shops NFO National Fairtrade Organization NGO Non-governmental organization SPP Símbolo de Pequeños Productores WFTO World Fair Trade Organization

OVERVIEW OF TABLES

Table 1. Overview of the nature of Fair Trade’s building blocks ...11

Table 2. Overview of Hernandi’s hermeneutic triad ...16

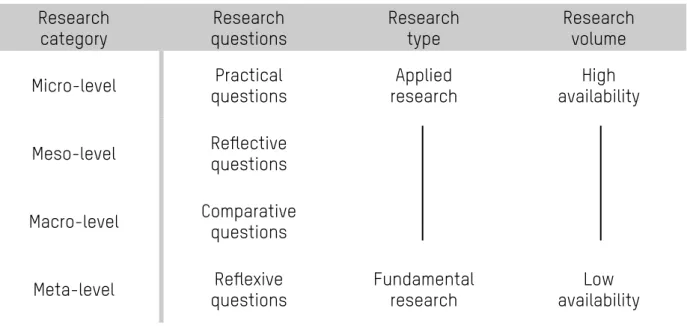

Table 3. Overview of the research body on Fair Trade ...17

Table 4. Overview of the research body on conceptualizing Fair Trade ...19

Table 5. Overview of the position of each narrative on the assumptions ...67

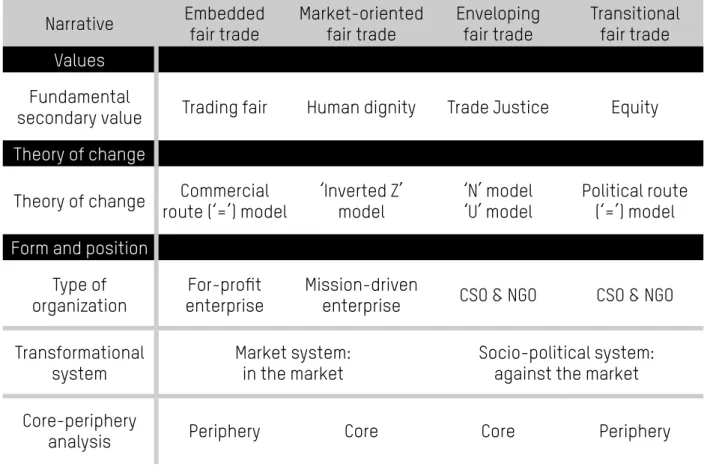

Table 6. Overview of the values, theories of change and characteristics of each

narrative ...68

OVERVIEW OF BOXES

Box 1. The FINE-definition of Fair Trade ...10

Box 2. The two-pronged approach of product mainstreaming ...46

Box 3. The two-pronged approach of policy mainstreaming ...48

OVERVIEW OF FIGURES

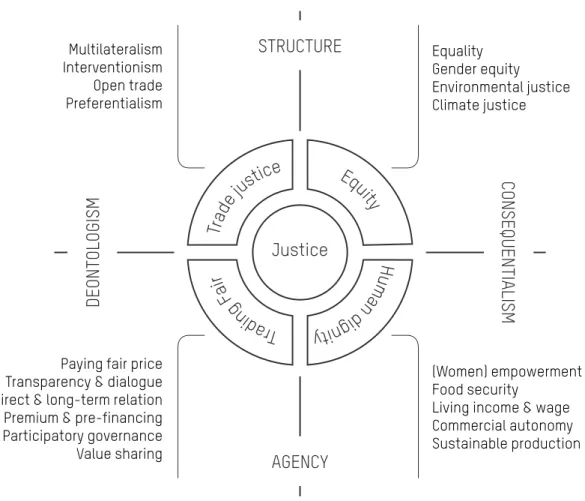

Figure 1. Visual representation of the assumptions of Fair Trade ...25

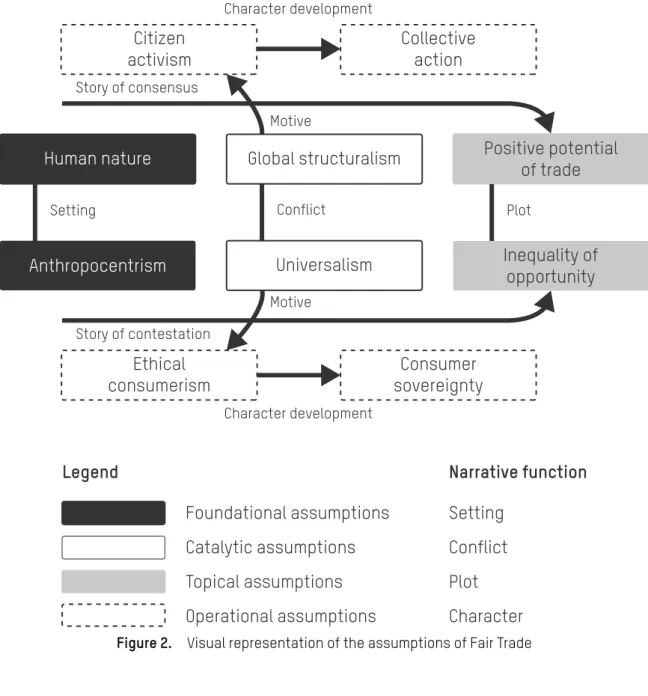

Figure 2. Visual representation of the assumptions of Fair Trade ...36

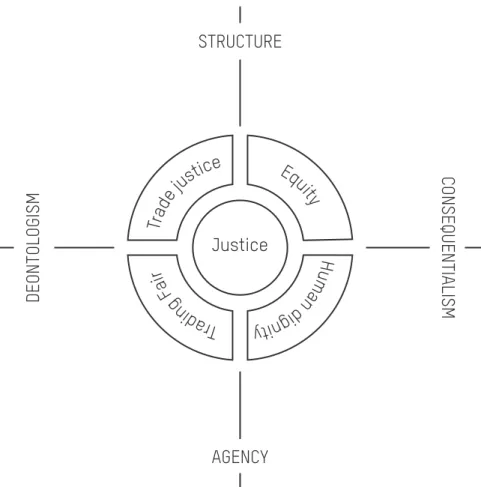

Figure 3. The primary value of the fair trade value system: justice ...38

Figure 4. Secondary values of the fair trade value system ...40

Figure 5. Tertiary values of the fair trade value system ...41

Figure 6. The ‘=’ model ...43

Figure 7. The ‘inverted Z’ model ...45

Figure 8. The ‘N’ model ...47

Figure 9. The ‘U’ model ...50

ChApTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO ThE RESEARCh SUBJECT

The subject of this thesis is Fair Trade. The sheer simplicity of this statement conceals many conceptual complexities (Miller, 2007, p. 253; A. M. Smith, 2013, p. 54) which will be clarified here. Firstly, Fair Trade is narrowed down to the philosophy held and expressed by the fair trade movement. Secondly, ‘Fair Trade’ is distinguished from morphologically related signifiers.

1.1. FAIR TRADE AS A phILOSOphY

Scholars have had difficulties understanding Fair Trade. This is illustrated by the many signifiers that have been used to refer to the concept: meta-narrative (Le Mare, 2007, p. 69), common fair trade principles and procedures (Raynolds, 2000, p. 301), comprehensive concept of control (Staricco, 2019, p. 96), the essence of Fair Trade (Horodecka & Sliwinska, 2019) or the fair-trade concept (Renard, 2005, p. 420; A. M. Smith, 2013, p. 53). These authors often leave the question unanswered what their signifier exactly entails, as defining it would lead any scholar down a rabbit hole away from their research objectives.

To keep things intelligible, Fair Trade will henceforth be approached as a philosophy: a more or less coherent cognitive framework of ideas on the world (worldview) that acts as a guiding principle for behavior. Of course, many such philosophies exist that cover trade and its relation to fairness. Observe the excerpt below.

In Mr Trump’s mind the most important path to better jobs and faster growth is

through fairer trade deals. Though he claims he is a free-trader, provided the

rules are fair, his outlook is squarely that of an economic nationalist. Trade is fair

when trade flows are balanced. Firms should be rewarded for investing at home

and punished for investing abroad (“Why Trumponomics won’t make America

great again”, The Economist, 2017 May 13).

This paragraph outlines roughly two accounts of fair trade: the nationalist account (held by US President Donald Trump) and a free trade account (held by the writer).

However, this thesis is exclusively concerned with the philosophy held and communicated by the fair trade movement. This means that ‘Trade’ is limited to the (inter)national exchange of goods (and services) in the market context (excluding for example children trading marbles for pogs). ‘Fair’ is limited to the morality of aforementioned ‘Trade’ with a specific focus on participating parties with lower (bargaining) power than others (excluding for example the morality of trading on the stock market).

While the fair trade movement is united by its philosophy, different interpretations of this philosophy exist, leading to a fair trade spectrum. These variations are approached as narratives in this thesis. Chapter three elaborates on both the concept of Fair Trade as a philosophy and the concept of narratives from a methodological standpoint.

1.2. FAIR TRADE AND SIMILAR SIGNIFIERS

The previous sections narrowed the concept Fair Trade down to the philosophy held and communicated by the fair trade movement. This however leaves ample room for confusion as other signifiers such as ‘Fairtrade’ and ‘fair trade’ are used in parallel. Therefore, it is necessary to distinguish their meaning. The signifier ‘Fairtrade’ (one word, capitalized) is used almost exclusively in reference to Fairtrade International1 (Dragusanu et al., 2014; Fisher, 2009, p. 985). Terms as Fairtrade standards, Fairtrade

label or Fairtrade Organizations are therefore all related to the operations and activities of Fairtrade International. However, this signifier is also used by other fair trade actors. For example, Fair Trade Original changed their brand name and company name to Fairtrade Original in 20182. Similarly, the

organization behind the Oxfam Fair Trade brand is officially registered as Oxfam Fairtrade. Finally, many producer groups within the movement use Fairtrade in their name: Sisaket Fairtrade Farmer Group (Thailand), Davnor Fairtrade Coco Farmers (Philippines) or Fairtrade Pineapple Growers’ Group (Thailand).

1 Fairtrade International (FI), officially the Fairtrade Labelling Organizations (FLO) International e.V., is an organization occupied with “connect[ing] disadvantaged producers and consumers, promote fairer trading conditions and empower producers to combat poverty, strengthen their position and take more control over their lives” (Fairtrade International, 2020). They are best known for labeling products guaranteeing that they were produced under the conditions stipulated in the Fairtrade standards.

2 The Stichting Fair Trade Original was however not dissolved in 2018. Instead, it became the sole shareholder of Fairtrade Original Besloten Vennootschap. The idea behind the name change was to differentiate from the Fairtrade label by focusing on the term Original, which became more prominent in the logo (E. van de Glind, personal communication, March 23, 2020).

The signifier ‘Fair Trade’ (two words, capitalized) refers to a wide range of ideas held by different actors in the fair trade movement (Le Mare, 2007, p. 71), nevertheless being all varieties of the same philosophy (Dragusanu et al., 2014, p. 218; Valiente-Riedl, 2013, pp. 2–3). These ideas are at least to some extend aligned with the ten principles of Fair Trade as defined by the World Fair Trade Organization3. That is why the signifier ‘Fair Trade’ is sometimes used in reference to this network

organization.

The signifier ‘fair trade’ (two words, not capitalized) is an open compound word which meaning is dependent on context in which it is used. It can thus be used in reference to the fair trade movement (Fisher, 2009, p. 985; Tallontire & Nelson, 2013, p. 28; Valiente-Riedl, 2013, pp. 2–3) but also in reference to other statements relating to fairness and trade (Horodecka & Sliwinska, 2019, p. 17; Le Mare, 2007, p. 71). Deriving meaning from context is therefore key, as was done above with the nationalist and free-trade account.

Lexically, Fairtrade can be interpreted as the hyponym of Fair Trade, which on its turn is a hyponym of fair trade. All three concepts were thus discussed in order of increased abstraction4.

In this thesis ‘Fair Trade’ is used when referring to the philosophy but ‘fair trade’ is preferred when used in combination with another word (for example ‘fair trade product’), with the exception of the word ‘philosophy’.

3 The World Fair Trade Organization (WFTO), formerly the International Federation for Alternative Trade (IFAT), is a network organization that promotes Fair Trade, makes sure producer voices are heard and advocates their interests (World Fair Trade Organization, 2014).

4 Some authors limit the scope of the term ‘fair trade’ to the actions of the fair trade movement (Fisher, 2009; Valiente-Riedl, 2013, pp. 2–3). This denotation changes the linear order of abstraction to: Fairtrade, fair trade,

pART 1

ChApTER 2. pROBLEM STATEMENT AND RESEARCh OBJECTIVE

2.1. pROBLEM STATEMENT

2.1.1. Research questions

This research is concerned with answering the following question: “What narratives on the Fair Trade philosophy are held and communicated by actors in the fair trade movement today?”

In seeking to answer this question, two secondary research questions should be looked at: (1) “What constitutes the Fair Trade philosophy?” and (2) “What constitutes the fair trade movement?” When inserted in the framework of narratives, the first question relates to the content of the story while the second question relates to the narrator.

Part two of this research looks into the building blocks of the Fair Trade philosophy and thus aims to answer the first secondary question. Part three will use these building blocks to construct archetypical narratives. As these narratives are specific to certain actors within the fair trade movement, an idea can be given of the constituents of the fair trade movement.

2.1.2. Delineation

The description of the research subject already delineated the research topic to some extent. Firstly, the research topic was limited to Fair Trade as the philosophy held by the fair trade movement. This excluded other accounts of trade in the context of fairness like neoliberal free trade or nationalistic protectionism. This also excluded broader interpretations of fair trade as exchanges beyond commercial transaction within the structured (global) marketplace like barter trade or emotional exchanges.

Secondly, it was stated that the research subject is interpreted as being broader than Fairtrade, which is a specific interpretation of Fair Trade. This delineation implies that it is presumed that (1) there is an overarching Fair Trade philosophy and (2) that different alterations exist of this philosophy, stipulating that fair trade is a dynamic (A. M. Smith, 2013, p. 53) and socially constructed concept (Béji-Bécheur et al., 2008, p. 44). This also entails that this research does not aim to offer a conclusive definition of Fair Trade. However, a working definition will be constructed in chapter three as a practical reference in the context of the research question.

Composing the main research question and the secondary research questions also entailed limiting the research topic to some extent.

Firstly, this research limits itself to narratives on the Fair Trade philosophy. This excludes describing individual actions taken by specific fair trade actors in much detail, for example campaigning, marketing, advocating or educating. Conversely, ideas held by the fair trade movement as a whole will be studied in more detail. This research thus keeps to the abstract level of analysis.

Secondly, the usage of the phrase ‘actors in the fair trade movement’ implies that while retaining a level of abstraction, this research will not approach the fair trade movement as a monolithic block. Contrarily, it will recognize the diversity of ideas and actors that are present in the movement. Thirdly, this research is limited to the current state of play, reflected by the excerpt ‘the fair trade movement today’. To fair trade scholars it is clear that the Fair Trade philosophy changed over time (Anderson, 2015; Jaffee et al., 2004; Will Low & Davenport, 2006; William Low & Davenport, 2005; Tallontire, 2009; Tallontire & Nelson, 2013; van Dam, 2018). However, this will be ignored for the larger part of this thesis due to resource constraints.

2.2. RESEARCh OBJECTIVE

2.2.1. Scientific relevance

Shortcomings in existing research

A large part of the research body on Fair Trade has been dedicated to the micro-level (practical question on specific fair trade operations and their impact on consumers and producers) (Nicholls, 2010, p. 241). While research on the meso-level (reflective questions on the governance and history of the fair trade movement) and macro-level (comparative questions on Fair Trade and its relation to fair trade) has increased in the last decade, it is mainly research on the meta-level (reflexive questions on Fair Trade) that has been lagging behind. These four categories will be further discussed in chapter four. Furthermore, attempts to explore the Fair Trade concept often result in partial or anachronistic accounts (A. M. Smith, 2013, p. 54). More than once, this is due to the exclusion of certain actors or practices present in the movement (neglecting the diversity of the movement) or by focusing on certain cleavages within the movement (neglecting the unity of the movement). Indeed, the aphorism ‘unity in diversity’ explains the movement very well (Gendron et al., 2009, p. 64; Huybrechts, 2010, p. 210; Nicholls, 2010; Wilkinson, 2007, p. 220).

Finally, meta-research on Fair Trade has been split between idealist (Fair Trade as a social construct) and materialist approaches (Fair Trade as actors and practices). While idealist approaches are appropriate to examine how meaning is constructed, their practical application is often limited or even unclear. Conversely, materialist approaches tend to be more accessible by practitioners, notwithstanding at the cost of unduly homogenization of the Fair Trade discourse (A. M. Smith, 2013, p. 54), illustrated by the extensive use of the almost two decades-old FINE definition of Fair Trade (see box 1, chapter three).

This research aims to address all of the above shortcomings. It looks into the Fair Trade philosophy (meta-level) by connecting ideational aspects (Fair Trade philosophy) with their materialist manifestations (narratives of actors about their actions)5. In the process, Fair Trade was interpreted

holistically without being focused on certain cleavages. The theoretical model especially developed for this purpose is a new and innovative technique for analyzing Fair Trade in a holistic fashion.

Contributions to the Fair Trade research field (and beyond)

On a functional level, this research provides answers to the questions “What constitutes the Fair Trade philosophy?” and “What constitutes the fair trade movement?” These are often left unanswered -or at least partially- by fair trade scholars.

The answers to the questions above are nevertheless necessary when conducting impact assessments on the fair trade movement. As they were missing before many such attempts failed to capture the complete impact of the movement. This led to a lack in comprehensive and macro-level impact analyzes of the movement (Horodecka & Sliwinska, 2019, p. 9; Nicholls, 2010, p. 241) and an underestimation in the overall impact of the movement. The model presented here can be used as a basis for such an assessment.

Additionally, it can also be utilized for describing regional or historical interpretations of Fair Trade. While historical and regional aspects are largely ignored in this thesis, the model lends itself to carry out such research. Furthermore, it lays the basis for a more moderate analysis of the cleavages that exist within the movement, recognizing the existing unity, and paying special attention to possible synergies and dysergies.

Finally, the theoretical model developed for the purpose of this research could be applied beyond the realm of Fair Trade. However, the model yet has to prove its worth when being applied to other social philosophies or political ideologies.

2.2.2. Societal relevance

The fair trade movement is fundamentally diverse. As demonstrated above, many authors struggled with this heterogeneity when trying to understand Fair Trade. On the other hand, practitioners and individuals close to the fair trade movement all have an implicit understanding of what Fair Trade is about (de Schutter et al., 2001, p. 24).

Within these personal views on Fair Trade there is often talk of a schism or discord. Authentic fair trade is contrasted with unauthentic fair trade, effective fair trade with ineffective fair trade, political fair trade with commercial fair trade or northern fair trade with southern fair trade. At the same time, elements of inseparableness are stressed, pointing to the fact there is but one fair trade movement. What unites the fair trade movement? What makes it so diverse? These questions drove the collaboration between the researcher and the Fair Trade Advocacy Office. This research is thus part of the capacity-building and thought-leadership workstream of the Fair Trade Advocacy Office and based on research conducted in the first part of 2019. It was translated into a series of three webinars organized by the Fair Trade Advocacy Office in the second part of 2019. They ultimately led to the development of the ideas put forward in this thesis.

The webinars reached an audience of more than 100 participants actively involved in the fair trade movement or otherwise preoccupied with Fair Trade in an academic capacity. The accompanying guide had more than 120 unique reads on issuu.com, excluding readers that received the guide through e-mail.

While the research presented here seems quite fundamental in nature, its direct societal relevance lies particularly in increasing the understanding of Fair Trade. After all, the efficiency of narratives as vehicles of a social philosophy can be improved if organizations are (1) fully familiar with their own philosophy and (2) if the utilized narratives closely match the philosophy and underlying values. Additionally, it can inform strategic discussion of fair trade actors as it provides an overview of the different pathways to change. Finally, collective reflections on the fair trade assumptions can instigate broader changes in the Fair Trade philosophy. This was illustrated by a webinar hosted by the Fair Trade Advocacy Office in April 2020 which reflected on the anthropocentric basis of Fair Trade, using the series of three webinars as a starting point.

Moreover, this research could indirectly create social benefits as it provides a framework for applied research. Firstly, it could be used as a framework to estimate the overall impact and thus effectiveness of the Fair trade movement. Secondly, it could be utilized to expose possible synergies or even dysergies within the movement when the theories of change are explored in a diametrically fashion. However, as stated above, the framework has yet to prove its worth regarding this objective.

ChApTER 3. METhODOLOGY AND OpERATIONALIZATION

3.1. OpERATIONALIZATION

3.1.1. Working definition of Fair Trade

This research is built around the definition of ideology of Heywood (1998, pp. 10–11): “a more or less coherent set of ideas that provides the basis for organized political action, whether this is intended to preserve, modify or overthrow the existing system of power. All ideologies therefore (a) offer an account of the existing order, usually in the form of a ‘world-view’, (b) advance a model of a desired future, a vision of the ‘good society’, and (c) explain how political change can and should be brought about – how to get from (a) to (b)”.

This is not to say that Fair Trade is a political ideology. Indeed, Fair Trade would be considered far too narrow to be a political ideology. Ideologies usually have broad and well-developed positions about most issues captured by the public opinion. It can then be argued that Fair Trade is a proto-ideology or a single-issue ideology. This however would be inaccurate too because certain fair trade practices go well beyond the political or state realm (Raynolds, 2012, p. 276).

Above-mentioned conceptual problem can be addressed in two ways. Either by expanding the definition of an ideology well beyond the political realm. Or by stating that Fair Trade is a social philosophy with the same analytical structure as political ideologies.

This research favors the second solution to avoid confusion with a political ideology. Fair Trade (philosophy) will thus, through a small alteration of Heywood’s definition (Heywood, 1998, pp. 10– 11), be defined as: a more or less coherent cognitive framework of ideas on the world (worldview) that provides the basis for organized action, whether this is intended to modify or overthrow the existing system of power. Fair Trade therefore (a) offers an account of the existing order (descriptive assumptions), (b) advance a model of a desired future (prescriptive values), and (c) explain how change can and should be brought about (programmatic theories) – how to get from (a) to (b).

As stated in chapter one, constructing a definition of Fair Trade is not the aim here. However, a working definition is necessary to clearly outline what the research subject is. Key fair trade organizations convened two separate times for drafting an official definition of Fair Trade, commonly referred to as the FINE definition of Fair Trade (see box 1 below). This definition is not used here as it is primarily focused on describing the activities of the fair trade movement. It is thus unfit to look into the cognitive framework of ideas of Fair Trade (A. M. Smith, 2013, p.54).

Box 1. The FINE-definition of Fair Trade

The umbrella network FINE was established in 1996 as an informal platform for collaboration between Fairtrade Labelling Organizations (FLO) International, the International Federation for Alternative Trade (IFAT), the Network of European World Shops (NEWS!) and the European Fair Trade Association (EFTA) (Krier, 2001).

Recognizing that the fair trade movement was in need of a definition, FINE adopted the following definition in April 1999 (European Commission, 1999, p. 13; Krier, 2001, p. 5).

“Fair Trade is an alternative approach to conventional international trade. It

is a trading partnership which aims for sustainable development of excluded

and disadvantaged producers. It seeks to do this by providing better trading

conditions, by awareness raising and by campaigning.” (Krier, 2001, p. 5)

In October 2001 this definition was expanded by FINE. It reflects the welcoming of hired labor (workers), the focus on the Global South and the increased importance of political action.

“Fair Trade is a trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency and respect,

that seeks greater equity in international trade. It contributes to sustainable

development by offering better trading conditions to, and securing the rights of,

marginalized producers and workers – especially in the

[Global] South.”

“Fair Trade organisations (backed by consumers) are engaged actively in

supporting producers, awareness raising and in campaigning for changes in the

rules and practice of conventional international trade.” (European Fair Trade

Association et al., 2001)

From time to time, the second part is not mentioned by mistake. Nonetheless it is an integral part of the definition. Since 2001 no new updates have taken place.

3.1.2. The three building blocks of Fair Trade

Fair Trade has thus three building blocks: descriptive assumptions, prescriptive values, and programmatic theories.

Descriptive assumptions constitute the basic apparatus for adherents to empirically but subjectively analyze the object of interest. Often times these assumptions take the form of presuppositions. They are typically unquestionable6 for insiders. They offer a justification for actions taken by adherents.

Descriptive assumptions help to answer the question: “What are the characteristics of the object of interest, i.e. trade?”

Prescriptive values are objectives or goals to which adherents work. In extreme form they take the form of promises related to a utopian vision of the object of interest. They offer thus a normative analysis of the world. Together with descriptive assumptions they offer a justification for actions taken by adherents. Prescriptive values help to answer the question: “What should the characteristics of the object of interest be, i.e. trade?”

Programmatic theories of change consist of a coherent set of operational strategies, limited by the descriptive assumptions and aimed at actualizing the prescriptive values. This component is thus the mediator between descriptive assumptions and prescriptive values by offering a process analysis. For Fair Trade, the programmatic component can be subdivided into multiple strategies or routes. Programmatic theories offer an answer to the question: “How do we change the object of interest, i.e. trade?”

Building block

Nature

Analysis

Assumptions

Descriptive

Empirical analysis

Values

Prescriptive

Normative analysis

Theories of change

Programmatic

Process analysis

Table 1. Overview of the nature of Fair Trade’s building blocks

6 This unquestionability means that assumptions often are beyond question or doubt. This can have multiple reasons. A first reason may be that the adherent is simply not aware of the fact that he holds this assumption. A second reason could be that the adherent is aware that he holds this assumption but is unable to critically question it because he lacks the necessary knowledge. A third reason may be that the adherent is aware that he holds the assumption and is able to critically question it but chooses not to do so because otherwise his

3.2. METhODOLOGY

3.2.1. Research paradigm: constructivism

Philosophically speaking, this research adheres to constructivism. This has implications on the ontological, epistemological, axiological and methodological level.

On the ontological level, Fair Trade is understood as just one possible account of the trade reality. This was illustrated in chapter one. Therefore, Fair Trade is interpreted as a philosophy, existing simultaneously with other (competing) philosophies.

On the epistemological level, Fair Trade will be interpreted as a social construct (Béji-Bécheur et al., 2008, p. 44), that is, the product of a process of inter-subjective construction (A. M. Smith, 2013, p. 54). As narratives reflect the process of the social construction of meaning, they will be the preferred instrument of analysis.

On the level of axiological ethics, perspectivism is favored over the idea of absolute neutrality. Firstly, individual perspectivism means that the researcher acknowledges the existence of predispositions and biases. The advantage of taking up this viewpoint is that some predispositions can be identified beforehand. In this case a Western or Northern look on what Fair Trade ought to be and the negligence of gendered structures.7 This obligates the researcher to critically take into account personal

attributes when carrying out the research and reporting the results. Furthermore, it invites the readers to critically examine the results in light of the revealed predispositions. Secondly, collective perspectivism implies that the Fair Trade philosophy is held, valued and perpetuated by a community, i.e. the fair trade movement. This substantiates the idea that Fair Trade is a dynamic concept as it transforms along with the values of the members of its community.

On the methodological level, the research techniques described below find their basis in the hermeneutic tradition. Needless to say, this research is qualitative and exploratory in nature.

7 Both potential predispositions were countered by selecting a balanced group of respondents in terms of gender and location. Additionally, this thesis was aimed to be written in gender-neutral language.

3.2.2. Research method: narrative research

Definition of narrative

Based on elementary definitions (Genette, Prince and Abbott in: Ryan, 2007, p. 23) , a narrative will be defined as an account of reality (ontological constructivism) embodied by a normatively substantiated logical string of connected events [axiological constructivism], and (re)produced by a community [epistemological constructivism].

To put in layman’s terms and applied to the research subject, a narrative is a description of trade [ontological constructivism], expressed via stories on fairness [axiological constructivism], and told and retold by (actors in) the fair trade movement [epistemological constructivism].

This definition reveals that narratives are both a mode of knowing (description of trade), a mode

of communication (told and retold) (Czarniawska-Joerges, 2004, pp. 6–12), and a mode of symbolic structuring (stories on fairness) (Mumby, 1987, p. 118). In sum, organizations use narratives as

vehicles to convey and materialize the boundaries of their constructed social reality, i.e. social philosophies. Narratives are thus an instrument to disseminate world views.

For the purpose of this research, narratives are broken down into its traditional constituent units: a setting, a conflictual situation, characters and their development, and a plot (Ryan, 2007, p. 24). The beginning of chapter five elaborate more on these constituents, while applying them to the research subject.

Usage of narratives

Narratives are utilized throughout the research design (McAlpine, 2016, pp. 35–36). That is, they are used in the data collection phase, the data analysis phase, and the data reporting phase.

3.2.3. Data collection methods: document analysis and interviews

Given that narratives are “material instantiations of ideology” (Mumby, 1987, p. 118) it must be possible to distinguish the worldview of organizations by analyzing their narratives. Indeed, “unpacking narratives is useful because it reveals the different assumptions and worldviews that underpin the actions of different actors” (Tallontire & Nelson, 2013, p. 31). Therefore, narratives will be looked for in the data collection phase.

As narratives present themselves in written as well as in oral form (Squire, 2008) it is appropriate to adopt a set of research techniques that is able to capture both kinds of narratives.

Therefore, both document analysis and interviews will be used to reveal the narratives within the fair trade movement.

Document sampling

Documents were selected via purposive sampling on the basis of their relatedness to the research topic (quality of information) as well as the variety and abundance of ideas that they have integrated within them (quantity of information) (Mortelmans, 2013, pp. 153–154).

This research is based upon documents obtained from key organizations like Fairtrade International, Producer networks, National Fairtrade Organizations (NFOs), the World Fair Trade Organizations, SPP Global or other long time members of the fair trade movement. While most documents can be consulted online, some internal documents were obtained through personal conversations.

Apart from primary sources, existing scientific research and personal experiences as fair trade practitioner and consumer were also used as a source of data.

Respondent selection

The research population consists of a diverse set of organizations that are part of or closely related to the fair trade movement, i.e. adhering to some extent to the Fair Trade philosophy. Quite remarkably, a next to complete8 overview of this research population can be composed by combining the databases

of the different labeling and fair trade network organizations. In this research the databases of four fair trade umbrella organizations where used ECOCERT SA (Fair for Life), Fairtrade International, SPP Global and the World Fair Trade Organization.

The sampling frame consists of organizations that are mature enough to have developed a specific narrative on fair trade and be able to communicate it. Another excluding criterion is based on language. Due to limited resources and limited language skills of the researcher, only organizations that are able to communicate in Dutch, French or English will be included in the sampling frame. Luckily, most mature fair trade organizations are able to communicate in French or English.

8 Non-certified or non-guaranteed fair trade organisations exist. Consequently, these will not show up in the databases listed above. However, such cases are rather marginal.

Seven organizations where selected through theoretical sampling on the basis of their relatedness to one of the four narratives constructed in part four (quality of information) (Mortelmans, 2013, pp. 164–167). That is to say, specific theory confirming cases where sought to refine the constructed narratives. To guarantee qualitative high information different options of fair trade organizations where explored by (1) consulting web pages of the organizations and (2) through personal conversations with different key network actors in the fair trade movement. Within these organizations, respondents were selected who are involved in developing the strategic course of the organization vis-à-vis fair trade (quantity of information). Additional parameters like (1) geographical location (global North and global South) of the organization, (2) relatedness to a fair trade certification scheme (Fairtrade, WFTO GS, SPP or Fair for Life), (3) and gender of the respondent were used to obtain a more or less balanced set of respondents. All respondents are listed in annex 1, together with their values on above described parameters and their function titles.

Handling and processing the documents

All documents where categorized using the source managing software Zotero.

Conducting and processing the interviews

Due to the outbreak of COVID-19, all interviews were conducted over online platforms. The semi-structured topic-based interviews were built around the building blocks described in part two. However, ample room was left to allow for diverging viewpoints of respondents (Fraser, 2004, pp. 184–185; Mortelmans, 2013, pp. 231–233). The interviews were conducted in a conversational style as to create room for narratives to unfold themselves. The structure of the interviews can be found in annex 2.

While the usage of key interviews allowed for the collection of important data, the use of focus groups could have countered participant bias by including consumers and suppliers of an organization. Additionally, some contested narratives could have been identified this way. This was however not possible given the limited amount of resources.

3.2.4. Data analysis method: Hernadi’s hermeneutic triad

Narratives were reconstructed, deconstructed and constructed using Hernadi’s hermeneutic triad (Czarniawska-Joerges, 2004, pp. 60–61). Hernadi distinguished three conceptual ways of reading texts: explication, explanation and exploration.

Explication refers to interpreting texts with the aim to reveal their meaning. The result is a reconstruction of the essence by providing a translation without changing the meaning, i.e. reproducing the text. This process “implies humility on the part of the reader” (Czarniawska-Joerges, 2004, p. 60). In other words, the position of the reader is standing under the text.

Explanation refers to a critical reading with the aim of uncovering the motives or arguments behind the text (Czarniawska-Joerges, 2004, p. 60). The result is a deconstruction by inferring meaning through the original text. The position of the reader is standing over the text.

Exploration refers to the introduction of personal elements into the meaning of the text (Czarniawska-Joerges, 2004, p. 60). It results into a novel but related construction by an existential enactment of the original text. The position of the reader stands (partially) in for the original text (perspectivism).

Explication

Explanation

Exploration

Position of reader

Standing under

Standing over

Standing in for

Process

Reproductive

translation

Inferential detection

enactment

Existential

Result

Reconstruction

Deconstruction

Construction

Table 2. Overview of Hernandi’s hermeneutic triad

3.2.5. Data reporting: research outline

While all three kinds of reading (explication, explanation and exploration) are practiced simultaneously and synergies exist between them, the output or results will be reported broadly along the lines of these three kinds of reading.

Chapter four reconstructs existing literature on the Fair Trade philosophy. Part two (chapter five to seven) offers a deconstruction of the Fair Trade philosophy on the basis of document analysis complemented by academic articles on topics which are already examined. Part four (chapters eight to eleven) presents four constructed archetypical Fair Trade narratives on the basis of the interviews.

ChApTER 4. RESEARCh CONTEXT AND LITERATURE STUDY

Before diving into the existing literature dedicated to the Fair Trade philosophy, it is necessary to give an overview of available academic literature concerned with broader issues related to Fair Trade to offer some context.

4.1. FAIR TRADE RESEARCh CATEGORIES

The body of research on Fair Trade is vast and diverse. For analytical purposes, it can be subdivided into four levels.

The micro-level is concerned with practical questions related to the operations of the movement. For example: “What is the impact of certification on child labor practices?” The meso-level is occupied with reflective questions on the movement. For example: “How is the movement governed?” The macro-level is concerned with comparative questions. For example: “How does Fair Trade relate to free trade?” Finally, the meta-level is concerned with reflexive questions on Fair Trade. For example: “What is Fair Trade?”

Research

category

questions

Research

Research

type

Research

volume

Micro-level

questions

Practical

research

Applied

availability

High

Meso-level

Reflective

questions

Macro-level

Comparative

questions

Meta-level

questions

Reflexive

Fundamental

research

availability

Low

Table 3. Overview of the research body on Fair Trade4.2. SOME EXAMpLES

Research belonging the micro-level category is mainly concerned with ethical consumerism (Ladhari & Tchetgna, 2015; Taylor & Boasson, 2014) and the impact of fair trading relationships on producers, workers, women, and the environment (Le Mare, 2008; Lyon, 2010; Meemken et al., 2019; S. Smith, 2013; Terstappen et al., 2013)

Research on the meso-level is preoccupied with the governance of fair trade organizations and associated power relations, the history and overall impact of the fair trade movement, and internal issues of fairness (Anderson, 2015; Bacon, 2010; Béji-Bécheur et al., 2008; Clark & Hussey, 2015; Discetti et al., 2019; Hussey & Curnow, 2013; Mason & Doherty, 2016; Renard, 2005; Renard & Loconto, 2013).

Research belonging to the macro-level category tries to answer questions related to the position of Fair Trade in the wider economy, its relation to other worldviews, and the challenge its poses towards contemporary dominant societal and economic systems. (Bacon, 2015; Ehrlich, 2010; Fridell, 2006, 2010; Goodman, 2004; Nicholls, 2010; Raynolds, 2000; Rice, 2010)

Research on the meta-level has been conducted into two fields. On the one hand research has been done to improve methodologies for conducting research on Fair Trade (Becchetti et al., 2015; Hassoun, 2018; Horodecka & Sliwinska, 2019; Paul, 2005). On the other hand, scholars have been occupied with the ontological questions on Fair Trade and its movement.

This research is centered around ontological questions on the meta-level but presents at the same time a new theoretical model to analyze Fair Trade. The next chapter therefore explores the boundaries of current academic thinking on conceptualizing Fair Trade.

4.3. CONCEpTUALIZING FAIR TRADE

Scholars have contributed in many ways to the ontological questions regarding Fair Trade. Some preliminary distinguishing factors can be made.

A first distinction can be made between research aiming to provide a partial account of Fair Trade (describing certain elements) or a complete account of Fair Trade (describing holistically). A second distinction is that between research based on materialism (Fair Trade as actors and actions) and idealism (Fair Trade as an idea). A third distinction is related to the schisms or tensions within the fair trade movement. Two tensions especially emerge in academic literature: the tension between a Northern and a Southern interpretation of Fair Trade, and the tension between reformist and radical interpretations of Fair Trade. That is not to say that other divisions are not present in the movement and subsequently in research on the subject.

Article

partial or complete

First distinction:

account

Second distinction:

materialism or

idealism

Third distinction:

North-South tension

or reformist-radical

tension

Anderson

(2018)

Partial account

Materialism

Other

Fridell

(2006, 2007, 2010)

Complete account

Materialism

Reformist-Radical

Le Mare

(2007)

Complete account

Idealism

North-South

Moore

(2004)

Complete account

Materialism

Both

Smith

(2013)

Complete account

Idealism

Reformist-Radical

Staricco

(2019)

Partial account

Idealism

Both

Tallontire and Nelson

(2009, 2013)

Complete account

Materialism

Reformist-Radical

and others

VanderHoff Boersma

(2009)

Partial account

Materialism

Both

Walton

(2010)

Complete account

Materialism

Reformist-Radical

Anderson (2018) contributed to the understanding of Fair Trade by examining the concept of ‘ethical consumerism’ within the theory of change of Fairtrade International. He distinguishes four consumer narratives and places them within a historical context. In the current dominant narrative citizen-consumers are framed as actively working towards a better world.

Fridell makes the distinction between the ‘fair trade network’ and the ‘fair trade movement’. The former being “formal system of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that connects peasants and workers in the South with partners in the North through a system of fair trade rules” (Fridell, 2010, p. 458). The latter refers to a broader unofficial movement of “Southern governments, international organizations, and non-governmental organizations with the purpose of radically altering the international trade and development regime in the interest of poor nations in the South” (Fridell, 2007, p. 45). The author continues by subdividing the fair trade network into the shaped-advantage perspective (offset some negative impact of globalization), the alternative perspective (alternative model of globalization) and the decommodification perspective (challenging commodification of goods under capitalism) (Fridell, 2006). He claims that while the official goals line up with the alternative perspective, in practice only the shaped-advantage perspective is attained.

Le Mare (2007) aimed to describe Fair Trade by looking into the circuit of culture within the movement. While she reveals many aspects of Fair Trade, she does not structure them beyond the five moments of the framework of the circuit of culture9. The added value of her research is that: (1) the complexity

of Fair Trade is revealed by identifying different interpretations , while at the same time indicating that these “manifestations of Fair Trade are based on shared meanings and values, a meta-narrative constructed through the personal experience” (p. 71) of the people involved in Fair Trade; and (2) that it exposes how narratives are constructed within the fair trade movement.

Moore (2004) distinguishes two visions on Fair Trade: (1) “a working model of international trade that makes a difference” (p. 74) and (2) a radical vision that challenges the orthodoxy in business practice by providing an instrument to alter the current dominant economic model. He continues describing Fair Trade from a Southern producer perspective and a Northern trader and consumer perspective.

9 The circuit of culture theory states that cultural products (such as Fair Trade) are produced (given meaning) and constantly altered at five moments: representation, identity, production, consumption and regulation. For more info see the writings of Stuart Hall.

Smith (2013) provides an ontological account of Fair Trade by analyzing discourse (using theories of language) and practice (using the notion of ‘institutional facts’ in a historical context). In his research he aligns himself with the idea of Béji-Bécheur, Pedegral and Özçaglar-Toulouse that “fair trade is a socially constructed notion” (2008, p. 44). It builds further on the dichotomy between a ‘reformist Fair Trade’ (providing benefits to certain trade partners) and ‘radical Fair Trade’ (aiming to transform existing trade relationships). He concludes that certain historical events contributed to a more reformist interpretation of Fair Trade. The competing Fair for Life certification system can, according to him, contribute to this development or conversely, steer the meaning of Fair Trade towards more radical interpretations.

Staricco (2019) critically examines the Fairtrade worldview through the lens of a neo-Gramscian conceptual framework. Through a reconstruction of the Fairtrade concept of control he lays bare that (1) class struggles are reframed within a North/South dichotomy, (2) conflicting interests between capital and labor are presented as compatible, and (3) the problem of commodity fetishism10 within

the Fairtrade system itself is ignored. As a consequence, Fairtrade is doomed to be a failed reformist initiative.

Tallontire and Nelson, acknowledging the existence of diverging perspectives present in the fair trade movement, construct a two-axis model based on (1) a comprehensive and reductionist concept of development and (2) an instrumental and integrative perspective on the role of business (Tallontire, 2009). Using historically significant moments in the fair trade movement they explain that the movement shifted from a politicized position to a more institutionalized or even a managerialist position. Building upon this framework they later identified a pull towards a more pragmatist position accompanied by marginal attempts to return to a politicized position (Tallontire & Nelson, 2013). VanderHoff Boersma (2009), one of the founding fathers of fair trade certification, states that the original vision of Fair Trade as a ‘different type of market’ has been gradually pushed away by a ‘narrative based on poverty reduction’. He reexplores the Southern perspective by establishing some key principles: (1) effectiveness, (2) ecological sustainability, (3) social sustainability and (4) direct producer-consumer relations. He concludes by stating that fair trade governance structures should be democratized through the inclusion of producers. Additionally, the movement should strengthen its ties with other social movements in an attempt to challenge the dominant neoliberal trade regime.

10 “Commodity fetishism is the tendency of people to see the product of their labor in terms of relationships between things, rather than social relationships between people. In other words, people view the commodity only in terms of the characteristics of the final product while the process through which it was created remains

Walton (2010) aimed to construct a definition of Fair Trade by exploring different alternative conceptualizations and eliminating those which are “unpersuasive” or “cannot better the one already defended” (p. 431) Through this process he eliminates definitions as ‘Fair Trade as global market justice’, ‘Fair Trade as ethical consumerism’, ‘Fair Trade as a development initiative’, and ‘Fair Trade ‘in and against’ the market’. He concludes by defining “Fair Trade (…) as an attempt to offer interim global market justice in a non-ideal world.” (p. 443). It is argued here that Walton fails to acknowledge Fair Trade as en essentially contested concept, which leads to the fallacy of composition. Indeed, while it is true that his definition might be correct for some actors, it fails to include diverging visions on Fair Trade held by other actors.

pART 2

Deconstructing

Fair Trade

OVERVIEW: ThE FAIR TRADE phILOSOphY

The fair trade movement is diverse and heterogeneous (Staricco, 2019, p. 96). Nevertheless, it is clear that individuals and organizations involved in the fair trade movement, how diverse they may be, are connected by a single idea (Horodecka & Sliwinska, 2019, p. 21). As it is stated in the International Fair Trade Charter: “The Fair Trade movement is made up of individuals, organizations and networks that share a common vision of a world.” Or as it is put in words by the World Fair Trade Organization: “[Fair Trade] is not just a name and identity, it is an idea” (Sarcauga, 2014).

This common fair trade idea, or the Fair Trade philosophy as it is referred to here, can be broken down into the three building blocks described earlier. Each of the subsequent chapters cover one such building block.

ChApTER 5. FAIR TRADE’S DESCRIpTIVE ASSUMpTIONS

Descriptive assumptions constitute the basic apparatus for adherents to empirically but subjectively analyze the object of interest. In the case of Fair Trade this object of interest is the trade system and the behavior of all embedded actors. Descriptive assumptions help to answer the question: “What are the characteristics of the object of interest?”

5.1. CLASSIFICATION OF ThE ASSUMpTIONS

Ten different assumptions related to Fair Trade are distinguished. Most of the assumptions are disentangled further so to reveal all underlying components.

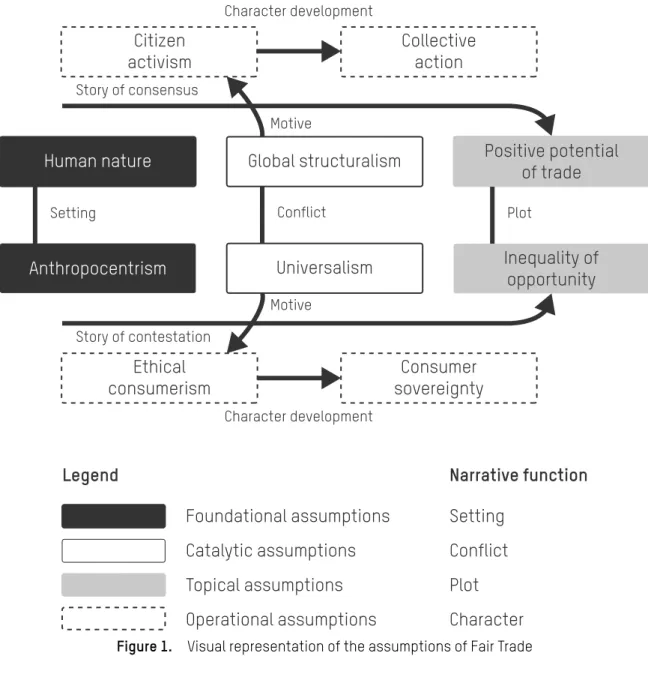

Before diving into each assumption separately, it is shown how these assumptions are related to each other and to the traditional constituent units of a narrative (Ryan, 2007, p. 24). The following figure provides visual support.

Figure 1.

Foundational assumptions

Catalytic assumptions

Topical assumptions

Operational assumptions

Legend

Human nature

Positive potential

of trade

Global structuralism

Anthropocentrism

Universalism

Inequality of

opportunity

Narrative function

Setting

Conflict

Plot

Character

Citizen

activism

Collective

action

Consumer

sovereignty

Ethical

consumerism

Setting Conflict Plot

Story of contestation Story of consensus Character development Character development Motive Motive

Visual representation of the assumptions of Fair Trade

The foundational assumptions (human nature and anthropocentrism) provide context to the rest of the assumptions. In other words, they offer information that influences all the different assumptions. They are the foundation on which Fair Trade is built. In terms of narratives: they provide the setting in which the story takes place.

The operational assumptions (citizen activism, collective action, ethical consumerism and consumer sovereignty) provide actants which are influenced by or influencing other assumptions. In other words, they are necessary to describe core processes carried out within the fair trade theory of change. In terms of narratives, they relate to the characters and their actions.

The catalytic assumptions (global structuralism and universalism) provide leverage to other assumptions. In other words, they are necessary to set the theories of change in Fair Trade in motion. In terms of narratives, they describe a conflict which provides the characters with a motive to act. Finally, the topical assumptions (positive potential of trade and inequality of opportunity) provide closure by relating everything back to the topic of interest: to trade fairly. In other words, they bald all assumptions together into a denouement. In terms of narratives, they form the plot of the story. It is the shortest possible answer to the question: “What is Fair Trade?”

The next paragraphs explore the different assumptions in more detail. The summary presented at the end of this chapter ties together the assumptions into a ‘story of consensus’ and a ‘story of contestation’.

Please note that this research does not aim to validate or invalidate the distinguished assumptions. It merely tries to identify, describe and relate them.

5.2. DESCRIpTION OF ThE FOUNDATIONAL ASSUMpTIONS

5.2.1. Anthropocentrism

The fair trade movement has its origins in the first part of the 20th century. The emergence of the movement thus predates the emanation of the environmental movement as it is known today. Therefore, Fair Trade is embedded in the idea that humans take up a prominent or privileged role in the natural world, i.e. the anthropocentrism assumption, as was commonly accepted by the dominant ideologies at that time (Will Low & Davenport, 2006, p. 316; William Low & Davenport, 2005, p. 144). This anthropocentric worldview has been challenged, and subsequently been adapted, in the last decades. “(…) there is now a far greater awareness in the movement of the need to engage with the discourse on sustainability and to embed ecocentric principles” (William Low & Davenport, 2005, p. 144). Slowly, Fair Trade seems to be slowly evolving towards an ecocentric approach, reconnecting with more holistic interpretations from the Global South (VanderHoff Boersma, 2009).

5.2.2. Human nature

Fair Trade upholds the idea that human individuals are essentially social beings and collaborative and altruistic in nature (Horodecka & Sliwinska, 2019, p. 26). This means they will be inclined to enter into social interaction. These interactions result in the creation of shared meaning. For Fair Trade, this meaning is mostly a set of moral guidelines aimed to promote harmonious cooperation (within a trade relationship).

While human individuals are inclined to engage in such behavior, this does not mean that harmonious cooperation will be the automatic outcome. Therefore, “fair trade looks to foster moral connectivities” (Goodman, 2004, pp. 905–906).

These research distinguishes two related assumptions on human nature.

1) The transactionalist assumption specifies that individuals have the natural inclination

to enter into social exchange. By entering into a transaction, individuals project their

own struggle of self-preservation upon other human individuals, recognizing and

accepting that others have the same aspirations as they have. This leads to mutual

understanding (Watson, 2007, p. 272). All participants of a transaction are modified by

the transaction itself, and by the environment in which it takes place.

2) The solidarity assumption asserts that from this mutual understanding the idea rises

that to maximize the achievement of all aspirations, it is only natural to collectivize

these aspirations. This is done by creating feelings of unity, group feelings or the

creation of aggregate purpose, irrespective of the distance between fair trade actors

(Watson, 2007).

Note that the vision of Fair Trade on human nature differs quite substantially from the Homo

Economicus vision that neoclassical economics (or neoliberalism) upholds (Read, 2009). Self-interest

is replaced by solidarity, competition by cooperation and economic exchange by social reciprocity (Horodecka & Sliwinska, 2019, p. 26).

5.3. DESCRIpTION OF CATALYTIC ASSUMpTIONS

5.3.1. Universalism

Fair Trade philosophy is founded on the idea that human individuals are entitled to a certain set of minimal rights. As Goodman (2004, pp. 905–906) describes it: “fair trade looks to foster moral connectivities by calling on a number of human universals in the creation of livelihoods that are both materially sufficient and meaningful”. What these set of minimal rights or human universalities entail exactly is not relevant at this stage.

1) The universal rights assumption states that human individuals bear natural rights.

As opposed to legal rights, acquirement of these rights is not dependent on a certain

cultural or socio-political environment. Being a human individual alone is enough to

claim these rights. They are thus universal and inalienable.

2) The universal enforcement assumption presumes that these rights are not universally

exercised. The fact that these rights cannot be repealed does not mean that humans

cannot be deprived of the execution of these rights. In other words, there is inequality

in outcome (Maseland & de Vaal, 2002, p. 255). According to the Fair Trade philosophy,

this passive state of universal rights is not uncommon and indeed, is the motivation

to change the current state of play.

The universal rights and universal enforcement assumptions are motives to take action. Indeed, many scholars point out that there is indeed a link between fair trade consumption and values like universalism (Béji-Bécheur et al., 2008; Cailleba & Casteran, 2010; de Ferran & Grunert, 2007; Doran, 2009, 2010; Ladhari & Tchetgna, 2015; Özçaglar-Toulouse et al., 2006).

5.3.2. Global structuralism

In its discourse, the fair trade movement holds up a mirror to the world economy, revealing that underneath the economic transactions of the globalized economy lies a complex network of human interactions. This network inevitably becomes more globalized, complex and interdependent. In the current economic system, these interactions are shaped by power structures that influence the outcome of transactions.

For conceptual clarity, this idea can also be split into two assumptions.

1) The globalism assumption states that, given the progressive collectivization of

aspirations (the solidarity assumption), the economic structure underpinning

human society can only become more connected and complex, up until the point it

encompasses the complete globe, as it is the case today.

2) The structuralist assumption asserts that human interactions are shaped by broader,

overarching structures (norms, conventions, power) that are determinative for the

outcome of these interactions (the transactionalist assumption). This implies that

when these structures are altered, the outcomes of all interactions subject to these

structures are altered too.

When applying the globalism and structuralist assumption to world trade, the notion of a trade regime or trade system encompassing and influencing all individual trade relationships is encountered. This global trade regime is more than the sum of its parts. Authors like McMichael (2009) examined this concept in more detail.

Fair Trade’s catalytic assumptions (universalism and global structuralism) make that it has a globalist, internationalist, cosmopolitan point of view as opposed to nationalist, localist or anti-globalist paradigms.

5.4. DESCRIpTION OF ThE OpERATIONAL ASSUMpTIONS

5.4.1. Ethical consumerism

Fair Trade relies heavily on the concept of ethical consumerism (Anderson, 2018). The assumption of ethical consumerism manifests itself in two ways within the fair trade discourse.

1) The ethical consumer assumption states there is a category of consumers in each

given market in which it operates who makes their consumption choices on the basis

of ethical considerations

11, beyond classical utility maximization (Anderson, 2018;

Horodecka & Sliwinska, 2019, p. 21).

11 Contrarily, scholars have identified a gap between the attitude and the behavior of ethical consumers (Caruana et al., 2015; Shaw et al., 2016). However, as stated earlier, it is not the purpose here to prove