TO WHAT EXTENT DO SEARCH

STRATEGIES ADD TO

DIFFERENCES IN EARLY LABOUR

MARKET OUTCOMES?

TO WHAT EXTENT DO SEARCH

STRATEGIES ADD TO DIFFERENCES IN

EARLY LABOUR MARKET OUTCOMES?

Walter Van Trier & Dieter Verhaest

Research paper SSL/2014.23/4.2

Leuven, 30 juni 2016

Het Steunpunt Studie- en Schoolloopbanen is een samenwerkingsverband van KU Leuven, UGent, VUB, Lessius Hogeschool en HUB.

Gelieve naar deze publicatie te verwijzen als volgt:

Van Trier W. & Verhaest D. (2014). To what extent do search strategies add to differences in early

labour market outcomes? Leuven: Steunpunt Studie- en Schoolloopbanen.

Voor meer informatie over deze publicatie dieter.verhaest@kuleuven.be; walter.vantrier@gep.kuleuven.be

Deze publicatie kwam tot stand met de steun van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap, Programma Steunpunten voor Beleidsrelevant Onderzoek.

In deze publicatie wordt de mening van de auteur weergegeven en niet die van de Vlaamse overheid. De Vlaamse overheid is niet aansprakelijk voor het gebruik dat kan worden gemaakt van de opgenomen gegevens.

© 2014 STEUNPUNT STUDIE- EN SCHOOLLOOPBANEN

p.a. Secretariaat Steunpunt Studie- en Schoolloopbanen HIVA - Onderzoeksinstituut voor Arbeid en Samenleving Parkstraat 47 bus 5300, BE 3000 Leuven

Beleidssamenvatting

Het belang van een succesvolle transitie van school naar werk is voldoende gedocumenteerd. Naast het onmiddellijke negatieve effect op het welzijn van jongeren, riskeert een slechte start van de arbeidsloopbaan permanente kwetsuren te veroorzaken die resulteren in een hoger risico op werkloosheid, lagere lonen en een lagere kwaliteit van jobs op een later punt in de carrière (Kletzer and Fairlie, 2003; Gregg and Tominey, 2005; Luijkx and Wolbers, 2009; Cockx and Picchio, 2013; Ghirelli, 2015). Vandaar het belang om te begrijpen wat het verschil in succes van het transitieproces veroorzaakt of welke mechanismen jongeren sorteren in verschillende soorten jobs in het begin van hun arbeidsloopbaan.

Zoals opgemerkt door Kerckhoff (2001) gebruikt het gros van de overgang van school-naar-werk literatuur zich op een conceptueel kader, gebaseerd op de zogeheten ‘origins/destinations’ metafoor. Men focust op de rol van individuele karakteristieken (zoals gender, etnische en sociale afkomst en onderwijsniveau) bij het verlaten van het Onderwijs om de karakteristieken van de arbeidsmarktpositie (kort) na intrede te verklaren. Globaal genomen stelt men daarbij vast dat de transitie minder succesvol is voor jongeren met lagere onderwijsniveaus, voor jongeren met een niet-westerse afkomst en voor jongeren uit lagere sociale klassen (Rees, 1986; Ryan, 2001). Hoewel deze vaststellingen suggereren dat een breed gamma van mechanismen een rol speelt, zoals verschillen in menselijk of sociaal kapitaal en discriminatie, is er weinig geweten over wat er gebeurt in de ruimte tussen het verlaten van het onderwijs en de start van de eerste job. De periode van de overgang zelf is nog altijd in grote mate een black box.

Dit rapport poogt om meer licht te werpen op wat er gebeurt tussen het ogenblik waarop jongeren het onderwijs (voor de eerste keer) verlaten en het ogenblik waarop ze hun eerste baan starten. Een belangrijke aanleiding om iets meer aandacht te geven aan wat er in deze tussenliggende periode plaats vindt, is het bestaan van een brede algemene literatuur over de effectiviteit van de verschillende zoekkanalen en verschillen in zoekgedrag. Zelfs als de evidentie over welke strategieën het meest effectief zijn niet eenduidig is, vinden de meeste studies over zoekstrategieën dat deze strategieën wel degelijk minstens gedeeltelijk van belang zijn voor het verklaren van arbeidsmarktsucces van volwassen werkzoekenden (Addison and Portugal, 2002; Thomsen and Wittich, 2010). Vandaar dat wij in dit rapport onderzoeken of en in welke mate toegang en gebruik

van verschillende zoekstrategieën al dan niet bijdraagt tot ongelijkheden in het succes waarmee jongeren die het onderwijs voor de eerste keer verlaten de overgang naar de arbeidsmarkt maken. Dit rapport beantwoordt drie vragen:

a) In welke mate gebruiken jongeren met verschillende karakteristieken verschillende zoekstrategieën?

b) In welke mate vinden jongeren met verschillende karakteristieken hun eerste job via verschillende zoekkanalen?

c) In welke mate zijn verschillen in arbeidsmarktuitkomsten kort na de transitie toe te schrijven aan verschillen in de gebruikte zoekstrategieën en vindkanalen?

Voor de analyses maken we gebruik van de SONAR-gegevensbank, die gegevens bevat over Vlaamse jongeren die de arbeidsmarkt hebben betreden gedurende de periode 1994-2004. Deze gegevens laten ons toe om te differentiëren tussen breed gamma van zoek- en vindkanalen, waarvan jongeren kunnen gebruik maken bij het zoeken naar en vinden van een eerste baan. Sommige van deze kanalen hebben tot hiertoe weinig aandacht gekregen in de literatuur over de resultaten zoekgedrag. Deze gegevens bevatten ook informatie over andere aspecten van zoekgedrag, zoals reservatiegedrag, intensiteit van het zoekgedrag, beginpunt van de zoekactiviteit of de mate waarin men tijdens de schoolloopbaan informatie over de arbeidsmarkt kreeg. Deze bijkomende informatie laat ons bijgevolg toe om een bredere kijk te krijgen op de verschillen in zoekstrategieën. Bovendien laten deze gegevens ons ook toe om enkele gedragskarakteristieken op te nemen, zoals de neiging om jobs aan te nemen. Deze karakteristieken ontbreken veelal in studies die exclusief focussen op de zoek- en vindkanalen zelf. Voor wat betreft het beoordelen van het succes van de overgang van school naar werk gebruiken we naast de snelheid waarmee een jongere zijn of haar eerste baan vindt ook op indicatoren voor de kwaliteit van de job (de duur van de eerste job, de status van de job en de arbeidstevredenheid) en op indicatoren voor de mate van overeenstemming tussen de opleiding en de eerste baan.

Zoals het geval is in de internationale literatuur blijkt uit onze analyses dat de manier waarop jongeren de overgang van school naar werk doormaken ook in Vlaanderen leidt tot substantiële ongelijkheden

in arbeidsmarktuitkomsten. Globaal genomen vinden we dat mannen1, jongeren met een westerse

1 Dit zijn resultaten na controle voor andere kenmerken en voor schoolverlaters die instroomden gedurende de periode

1994-2004. Recente gegevens op basis van de schoolverlaters VDAB (2015) tonen aan dat vrouwelijke schoolverlaters tegenwoordig gemiddeld beter scoren dan mannen. Daar waar in 2015 13,8% van de mannen een jaar na het verlaten van het onderwijs zonder job zat was dit voor de vrouwen slechts 9,7%. Factoren die deze verandering kunnen verklaren zijn onder meer een relatieve toename van het belang van de dienstensector en de relatieve toename in scholarisatie onder vrouwen (waar in deze globale VDAB cijfers niet voor gecontroleerd is).

achtergrond, hoger opgeleiden, jongeren met betere studieresultaten en schoolverlaters met werkervaring via stages of leertijd de overgang naar de arbeidsmarkt met meer succes maken dan hun tegenpolen. Zij vinden niet alleen sneller een eerste baan, deze baan is veelal ook van een hogere kwaliteit, want van langere duur, van hogere sociale status of gepaard gaand met meer arbeidstevredenheid. Bovendien vinden we dat mannelijke schoolverlaters, jongeren met betere studieresultaten en jongeren met werkervaring minder risico lopen op een mismatch. Conform aan de literatuur vinden we minder eenduidige resultaten voor de invloed van sociale achtergrond en sociaal kapitaal. Zo vinden we geen verband tussen sociale achtergrond en de duur van de overgangsperiode naar de eerste baan, maar we vinden wel dat schoolverlaters met hoger opgeleide ouders relatief meer terecht komen in jobs met een hogere socio-economische status.

In welke mate zijn deze verschillen in arbeidsmarktuitkomsten toe te schrijven aan de verschillen in zoekstrategieën van jongeren met verschillende karakteristieken?

Een eerste belangrijke vaststelling is dat hoe men naar een eerste baan zoekt en hoe men die vindt inderdaad van belang is voor een succesrijke overgang naar de arbeidsmarkt. Een eerste eenvoudige indicatie hiervan is het verschil tussen zoeken via een kanaal en vinden via een kanaal. De jongeren uit onze steekproef geven aan vooral naar hun eerste baan gezocht te hebben via de VDAB (57%), krantenadvertenties (54%) en spontane sollicitaties (54%). Daarna volgen persoonlijke relaties (42%) en uitzendkantoren (38%). Slechts 13% van de jongeren geeft aan gezocht te hebben via de school of onderwijsinstelling. 40% zegt een andere methode gebruikt te hebben. De meeste jongeren gebruiken meer dan één zoekkanaal. Het gemiddelde aantal opgegeven zoekkanalen is 2,9. Maar niet alle zoekkanalen zijn even effectief. Van de jongeren die zochten via uitzendkantoren vindt 33% een eerste baan via dat kanaal. Hetzelfde geldt voor wie zoekt via persoonlijke relaties. Van wie zocht via school vindt 21% een baan via dat kanaal. In het geval van spontane sollicitaties gaat het om 23%, bij krantenadvertenties om 15% en bij de VDAB om 12%. Men moet uiteraard voorzichtig zijn met een dergelijke effectiviteitsmaatstaf. Hij houdt bijvoorbeeld geen rekening met de invloed van eventuele verschillen in aanwervingspraktijken in verschillende segmenten van de arbeidsmarkt, maar deze gegevens ondersteunen in ieder geval de idee dat de verschillende manier waarop jongeren gebruik maken van wat hen ter beschikking staat bij het zoeken naar een eerste baan een zekere ‘structurerende capaciteit’ (Kerckhoff) heeft naast en boven hun onderwijskarakteristieken, sociale achtergrond en andere persoonlijke karakteristieken.

Twee meer specifieke vaststelling hebben betrekking op aspecten van het zoekgedrag zelf.

Wie minder kieskeurig is of, anders gezegd, meer geneigd om om het even welke job aan te nemen vindt sneller een eerste baan. Maar twee zaken vallen hierbij op. ten eerste, terwijl

geringere kieskeurigheid een positief effect heeft op het vinden van een eerste baan via de meeste zoekkanalen, is dat niet het geval voor het vinden van een eerste baan via de VDAB. Dit suggereert dat dit kanaal een specifieke rol speelt in de koppeling van vraag en aanbod op de arbeidsmarkt. Omwille van de relatie met het uitkeringssysteem en vormen van actief arbeidsmarktbeleid heeft dit kanaal wellicht een meer ‘dwingend’ karakter van de andere kanalen, waardoor het meer in staat is om eerder terughoudende jongeren te ‘overtuigen’ een baan aan te nemen. Ten tweede, minder kieskeurige jongeren vinden wel sneller toegang tot de arbeidsmarkt, maar geeft geen voordeel inzake de kwaliteit van de job. Integendeel, minder kieskeurig zijn heeft een negatieve invloed op de socio-economische status. Deze vaststelling bevestigt resultaten uit de internationale literatuur, die suggereren dat er een trade-off bestaat tussen snelle integratie op de arbeidsmarkt en kwaliteit van de eerste baan. Jongeren die op school meer informatie hebben gekregen over de arbeidsmarkt doen het substantieel beter. Zij gebruiken meer zoekkanalen en vinden ook sneller een eerste baan. Dit effect verschilt weliswaar aanzienlijk wanneer we kijken naar de specifieke kanalen waarlangs jongeren hun eerste baan vinden. Zo heeft meer informatie krijgen tijdens de schoolloopbaan geen significant effect op de snelheid waarmee iemand een eerste job vindt via de VDAB of via een uitzendkantoor.

Een opvallende vaststelling met betrekking tot de relatie tussen het kanaal waarlangs men de eerste baan vindt en de kwaliteit van de job betreft jongeren die hun eerste baan vinden via uitzendkantoren. Dat zij deze eerste job sneller verlaten dan jobs gevonden via andere kanalen is uiteraard niet verrassend. Jobs die men vindt via uitzendkantoren zijn immers per definitie tijdelijk en meestal van korte duur. Niettemin valt op dat deze jobs ook minder scoren op de twee andere indicatoren van jobkwaliteit: ze hebben een lagere socio-economische status en ze leveren minder arbeidstevredenheid dan jobs gevonden via om het even welk ander kanaal. Twee belangrijke opmerkingen volgen hieruit. Ten eerste, de belangrijkste vraag in dit verband is wellicht wat er gebeurt met deze jongeren nadat ze hun eerste (tijdelijke) baan hebben verlaten. Hoe verloopt hun verdere arbeidsloopbaan? Ten tweede, en hiermee verband houdend, wat is de status van eerste jobs die gevonden worden via uitzendkantoren? Gaat het om jobs die men aanvaardt uit noodzaak of om jobs die men in feite beschouwt als een verdergezette zoekperiode? Onderzoek over dit punt lijkt aangewezen.

Gegeven de mogelijkheid van een verband tussen alternatieve zoekstrategieën en arbeidsmarktuitkomsten is de vaststelling dat jongeren met verschillende karakteristieken ook verschillende strategieën hanteren belangrijk. Bijvoorbeeld, we vinden dat hoger opgeleide jongeren

kieskeuriger zijn en minder geneigd om om het even welke baan aan te nemen. Verder vinden we een meer intensief zoekgedrag bij vrouwelijke schoolverlaters, jongeren met een westerse achtergrond, hoger opgeleiden en schoolverlaters die geen achterstand oplopen. We vinden ook verschillen inzake het gebruikte zoekkanaal. Hoger opgeleiden zoeken meer via spontane sollicitaties en via de school, terwijl jongeren met de minder goede schoolresultaten meer via uitzendkantoren lijken te zoeken. Tenslotte vinden we ook substantiële verschillen in de kans op het vinden van een eerste job bij het bekijken van de verschillende kanalen. Jongeren met een niet-westerse achtergrond vinden hun baan relatief sneller via de school. Weinig verrassend is dat ook het geval voor jongeren werkervaring opgedaan op school. Bovendien vinden jongeren uit deze laatste groep ook sneller een baan via vroegere werkgevers of via spontane sollicitaties.

Globaal genomen betekenen deze resultaten we dus dat verschillen in zoekstrategie inderdaad bijdragen tot ongelijkheden in arbeidsmarktuitkomsten tussen groepen die verschillende strategieën gebruiken. Onze resultaten suggereren, bijvoorbeeld, dat onze vrouwelijke schoolverlaters hun eerste baan nog minder snel zouden hebben gevonden dan het geval is indien ze dezelfde zoekstrategie zouden hebben gehanteerd als hun mannelijke tegenhangers en hun ‘handicap’ niet gedeeltelijk zouden hebben gecompenseerd door meer intensief te zoeken. Iets gelijkaardigs vinden we voor wie minder goede studieresultaten kan voorleggen. Zij lijken hun minder goede arbeidskansen – in termen van snelheid waarmee zij een job en het risico op een mismatch – gedeeltelijk te compenseren door meer intens te zoeken, al doen ze dit vooral via kanalen die meer frequent leiden tot mismatches. Omgekeerd lijken hoger opgeleiden (volledige) mismatches te vermijden omdat ze toegang hebben tot kanalen die minder frequent resulteren in mismatches. Tenslotte lijken zoekstrategieën tenminste gedeeltelijk een verklaring te bieden voor verschillen in arbeidsmarktuitkomsten tussen wie wel en wie geen werkervaring via stages verwierf. Hoewel onze resultaten suggereren dat wie wel in dat geval is zelfs sneller een baan zou hebben gevonden indien ze (nog) intenser zochten, vinden we ook dat de kwaliteit van hun eerste baan minder goed zou zijn geweest indien ze geen toegang zouden hebben gehad tot in dat opzicht ‘succesvolle’ kanalen, zoals de school of spontane sollicitaties.

De bovenstaande vaststelling zijn interessant en belangrijk. Maar tegelijk is ook duidelijk dat de ongelijkheden inzake arbeidsmarktuitkomsten waarmee jongeren bij de overgang van school naar werk worden geconfronteerd zeker niet volledig en wellicht ook niet voor het grootste deel verklaard kunnen worden door verschillen in zoekstrategieën. Een goed voorbeeld betreft de schoolverlaters met een niet-westerse achtergrond. Zij zijn slechter af zowel inzake de snelheid waarmee ze hun eerste job vinden als inzake de kwaliteit van hun eerste job en dit blijft het geval ook na controle voor de verschillen in zoekstrategie. Een ander voorbeeld betreft de al dikwijls vastgestelde relatie tussen

onderwijsniveau en arbeidsmarktuitkomsten. Al bij al suggereert dit dat verschillen in zoekgedrag en zoekstrategie bij de overgang van school naar werk belangrijker zijn voor het verklaren van ongelijkheid binnen groepen dan voor het verklaren van verschillen tussen groepen. Voor het verklaren van dit laatste en grootste deel van de ongelijkheden lijken andere mechanismen, zoals menselijk kapitaal, signalen of discriminatie, beter geschikt. Zelfs als, zoals hierboven aangegeven, jongeren beter informeren over de arbeidsmarkt tijdens de onderwijsloopbaan en zorgen voor meer begeleiding bij de intrede op de arbeidsmarkt nuttig zijn om hun arbeidskansen te verbeteren dan nog lijken andere structurele beleidsingrepen in het domein van onderwijs en arbeidsmarkt nodig om ongelijkheid inzake arbeidsuitkomsten tussen groepen te weg te werken.

Het is ook evident dat meer onderzoek nodig om tot meer definitieve conclusies te komen over de manier waarop zoekstrategieën van belang zijn bij het verklaren van arbeidsmarktuitkomsten. Zoals aangegeven in het literatuuroverzicht in dit rapport is het internationale onderzoek op dit vlak uitermate schaars, inzonderheid waar het de specifieke groep van schoolverlaters betreft. Voor wat onze eigen analyses betreft is het duidelijk dat onze gegevens de nodige beperkingen kennen. De Sonar-gegevensbank bevat, bijvoorbeeld, geen gegevens over de volgorde waarin jongeren eventueel de verschillende zoekkanalen gebruiken. We weten ook niet of hun eerste baan ook de eerste baan is die hen werd aangeboden dan wel of ze voor die eerste baan andere banen hebben afgewezen. Daarnaast is het ook zo dat de variabelen die wij gebruiken om sociaal kapitaal te indiceren slechts een erg beperkt deel capteert van de vele dimensies die men in de internationale literatuur vindt opgesomd. Tenslotte zou onderzoek dat gebruik maakt van meer geavanceerd econometrische technieken welkom zijn om meer duidelijkheid te brengen inzake de causale relaties van verbanden die in onze en andere analyses empirisch werden vastgesteld.

Table of contents

Beleidssamenvatting v

Table of contents xi

1. Introduction 1

2. Previous literature 3

2.1 Inequalities in the transition from education to work 3

2.2 The importance of job search strategies 5

2.3 Job search strategies of first time education-leavers 6

3. Data and methodology 9

3.1 Searching for a job 9

3.2 Finding a job 11

3.3 Finding a ‘good’ job 12

4. Results 15

4.1 Descriptive results and search channel effectiveness 15

4.2 Job search behaviour 16

4.2.1 Which characteristics influence search behavior in general? 16

4.2.2 What determines the use of a particular search channel ? 20

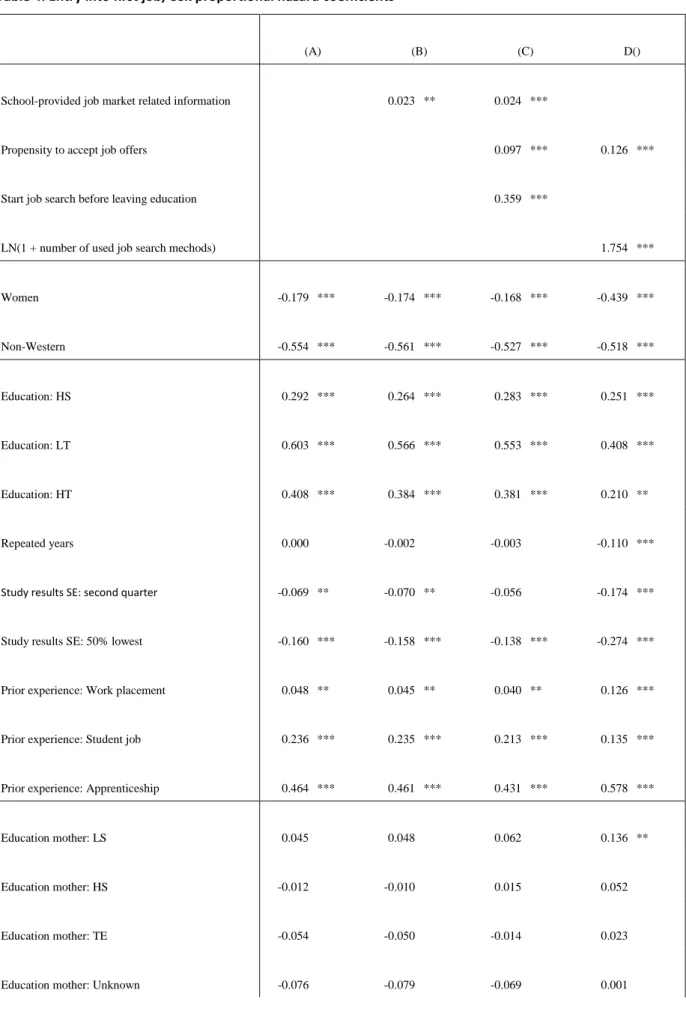

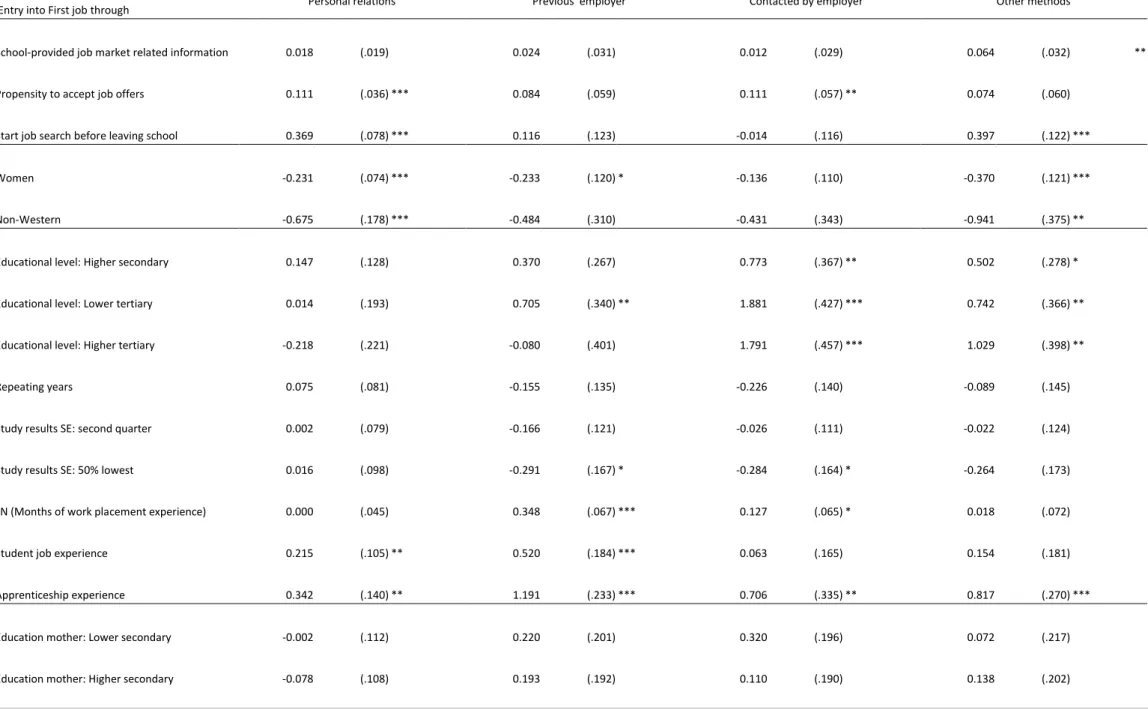

4.3 Job finding rates 23

4.3.1 General job finding rates 23

4.3.2 Channel-specific finding rates 26

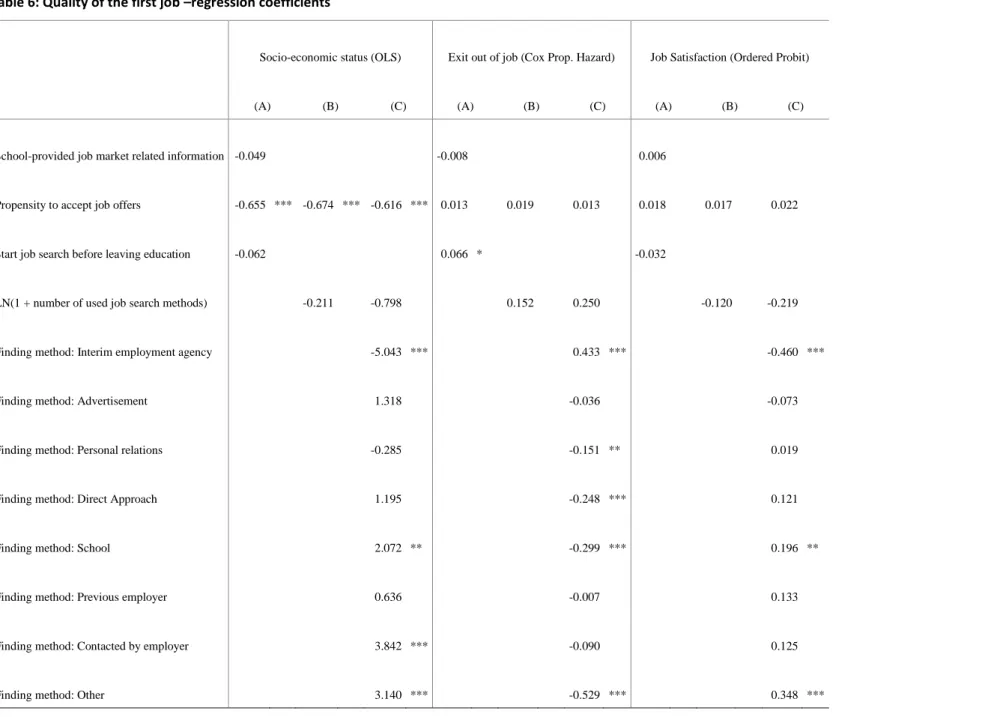

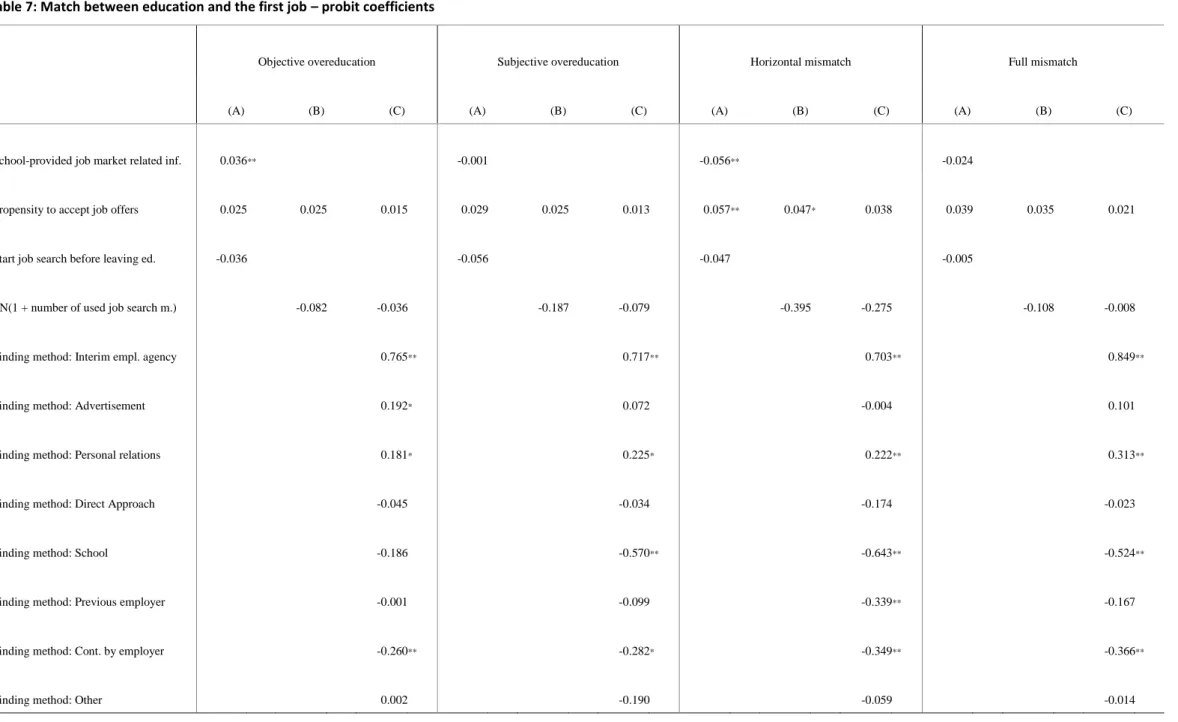

4.4 Job search outcomes 32

4.4.1 Job quality indicators 32

4.4.2 Mismatch indicators 37

5. Discussion and conclusion 43

5.1 Individual characteristics and labour market outcomes 43

5.2 Search strategies and labour market outcomes 43

5.3 Differences in search strategies across groups with different characteristics 44

1. Introduction

The importance of a successful transition from education to work is well established. Apart from the immediate negative effect on the well-being of young people, bad starts may also generate more permanent scarring effects resulting in higher unemployment risks, lower wages and lower-quality jobs at later points in the career (Kletzer and Fairlie, 2003; Gregg and Tominey, 2005; Luijkx and Wolbers, 2009; Cockx and Picchio, 2013; Ghirelli, 2015). Hence, the importance of understanding what determines the differences in success of the transition process or which mechanisms sort young people into different kinds of jobs at the beginning of their employment career.

As noted by Kerckhoff (2001), most of the school-to-work-transition literature relies for its conceptual framework on the ‘origins/destinations’ metaphor. It focuses on the role of individual characteristics (such as gender, ethnic, social and educational background) at the moment of leaving education to explain the labour market position of young people (shortly) after the transition. It is usually found that the transition is less successful for individuals with lower levels of education, for ethnic minorities or for youth from lower social classes (Rees, 1986; Ryan, 2001). Although these results suggest that a broad range of mechanisms, such as differences in human or social capital as well as discrimination may matter, what happens in the space between leaving education and entering the world of work is still very much a black-box.

This paper contributes to the literature attempting to shed light on what happens between the moment of leaving the educational system (for the first time) and the moment of starting a first job. An important reason to look a bit more closely at the content of the black box is the existence of a relatively large general literature on the effectiveness of different job search strategies. Even if the evidence is mixed on which strategies are most effective, most studies find that job search strategies do matter for labour market success (Addison and Portugal, 2002; Thomsen and Wittich, 2010). Hence, this paper investigates whether and to what extent access to and usage of different search strategies contribute to the observed inequalities in early market success across individuals with different educational careers, social backgrounds or ascribed characteristics.

To do so we ask three questions:

a) To what extent do young people with different characteristics use different search strategies? b) To what extent do young people with different characteristics find their first job through different

c) To what extent are differences in labour market outcomes after the initial transition from school to work affected by differences in search strategies and finding channels?

Our analysis uses data on Flemish first time education leavers. These data allow us to differentiate between a broad range of search and finding channels available to young people when looking for their first job, some of which have received less attention in the literature on job search effectiveness. They also contain information on several factors influencing job search behaviour, like reservation wages, job search intensity, job search timing and access to job search related courses at school, and, thus, allows us to get a broad picture of differences in job search strategies. In addition to allowing us to look into who uses which strategies, our data also enable us to include some behavioural characteristics, such as one’s propensity to accept jobs or the extent to which one start looking at a job before the end of education. These characteristics are often not included in studies focussing more exclusively on the search and finding channels themselves. The success of the transition from education to work is assessed in terms of the speed of the transition to the first job, the quality of the first job (job duration, job status and job satisfaction) and the match of the first job with the educational qualifications.

The remainder is structured as follows. After some comments on previous literature on inequalities in the transition from education to work and on the role of different search strategies in the next section, section 3 elaborates on the data and the methodology used. Section 4 presents the results of the estimations. Before making some concluding remarks and giving suggestions for further research, section 5 discusses our main findings.

2. Previous literature

2.1 Inequalities in the transition from education to work

There exists a relative large literature on inequalities in the transition from education to work. Much of this literature focuses on differences in early labour maket outcomes related to the different national institutional settings in which the transition from education to the labour market is embedded (Ryan, 2001; Blossfeld et al., 2005; Muller and Gangl, 2003). More specifically, analyzing data from the EU LFS 2000 ad hoc module on school-to-work transitions, Wolbers (2007) shows that the results indicate that the speed, the stability and the quality of the labour market entry process are indeed affected by national differences in employment protection legislation as well as in the vocational specificity of the education system.

However, this does not mean that within the different national settings individual characteristics do not matter. In his review of the school-to-work literature, Ryan (2001) mentioned race and educational background as factors that are consistently found to be important predictors of differences in youth joblessness and unemployment. Gangl (2003), for instance, found that, in most European countries, young individuals without qualification face substantially higher unemployment risks than those with an upper secondary degree which on their turn face higher unemployment risks than tertiary education degree holders. But not only the level of education matters since apprentices were found to perform better than other secondary education graduates in most countries. Also many other studies confirm that individuals with an apprenticeship have shorter transition durations (Bratberg and Nilsen, 2000). Another factor often mentioned is gender, even if the differences in unemployment are often weak (Ryan, 2001). In a more recent analysis of the transition from education to work in Europe, Mills and Präg (2014) concluded that young men and women transit to their first job equally fast in the first months after leaving education, but that after this time the differences between men and women continue to diverge with men having a higher likelihood to find a first job. They also noted that for both genders education has a protective effect in that the length of the transition period is negatively related to the level of education, but that women integrate slower than men at each educational level. Finally, also the role of social background and social capital in explaining differences in youth unemployment or joblessness has attracted substantial attention in the literature. However, evidence on a direct effect is rather mixed. For instance, Iannelli and Smyth (2008) found the relationship between the level of education of the parents and employment chances of young

workers for some but not all countries to be completely explained by differences in young workers’ level of education. Many of these conclusions have also been confirmed for Belgium or Flanders. Vanoverberghe et al. (2008) for instance found that the speed of the transition from education to work in Flanders is positively related to the level of education, gender, ethnic background and prior work experience.

Along with the speed of the transition process, also the quality of the job matters when evaluating the success of labour market entry. In general, factors that affect the duration of unemployment among labour market entrants also affect the quality of their jobs. The relationship between education, gender or ethnic background and earnings is well established in the literature (Altonji and Blank, 1999; Psacharopoulos and Patrinos, 2004). But the school to work transition literature has also identified substantial inequalities between educational and ethnic groups in terms of many other job quality dimensions, such as occupational status (Gangl, 2003), the duration of the first job (Bratberg and Nilsen, 2000), job satisfaction (Verhofstadt et al., 2007), or the likelihood to have a permanent contract (Verhofstadt et al., 2008). In terms of gender and social background, results are again more mixed, although Iannelli and Smyth (2008) found social background to matter for young individuals’ occupational status in most European countries.

A specific part of the literature assesses the successfulness of the transition process rather in terms of the realized match between one’s education and job. If solely looked at from this angle, more years of education may even prove to be detrimental, although the evidence differs across countries and regions. For Flanders, for instance, labour market entrants with an upper secondary education or university degree are found to face higher risks of being overeducated in their first jobs than those with a lower secondary or lower tertiary education degree (Verhaest and Omey, 2003). But also other educational characteristics, such as the vocational orientation of the program and study results matter. Labour market entrants from apprenticeship or other vocationally oriented programs are often found to realize better educational matches (Giret, 2011; Verhaest and van der Velden, 2003). Also, individuals with better grades or study marks usually realize better educational matches (Büchel & Pollmann-Schult, 2004; Verhaest et al., 2011). Finally, while the findings with respect to gender, ethnic and social background are not fully conclusive, several studies found lower incidences of mismatches early in the career among males (Verhaest and van der Velden, 2013), non-natives (Rafferty, 2012) and among individuals with lower educated parents (Opheim, 2007; Verhaest and Omey, 2010).

2.2 The importance of job search strategies

Despite the extensive literature on the differences in labour market outcomes experienced by school leavers, neither the comparative literature focusing on differences relating to institutional framework in which the transition takes place nor the analyses of the impact of individual characteristics within each of the national settings give much attention to potential the role of the available job search methods or to job strategies in explaining the differences.

Yet, in economics as well as in sociology, there exists an extensive empirical literature on the use and effectiveness of different job search methods, originating in the work of Rees (1966) following Stigler (1962) (but see also: McCall, 1970) in the case of economics and starting with the seminal work of Granovetter (1974) in the case of sociology. Both these literatures conceptualize the search process, basically, as a problem of gathering information and conceive of the channels through which jobs are searched for and found as information networks. The basic intuition behind this approach is that different search channels are characterized by differences in the cost (in time, effort and money) born by those who are looking for jobs as well as by differences in the quality of the information (about the availability as well as about the characteristics of jobs) provided by the channels. The main contention looked at in this early literature was the claim that informal search methods were more effective than formal ones, i.e. resulting in finding jobs more quickly as well as in providing for better jobs (mostly evaluated in terms of wages) and better matches (mostly operationalized in terms of job satisfaction). From a practical point of view, the bulk of the research following this approach focuses either on the relative effectiveness of social networks (Adnett, 1987; Montgomery, 1991) or on the performance of the official employment office (Osberg, 1993). As a result, most analysis take (one of) these two main search or finding channels as their starting point, reducing the typology used in many cases to a mere bi-polar distinction between informal methods, m.m. the public employment office, versus other methods. When more elaborate typologies are used, most typologies rely on empirical generalizations or on a simple reordering of the answer categories used in surveys (Jones, 1989; Forsé, 1997; Osberg, 1993) rather than on theory-informed constructs.

Despite the extensive literature on the relative effect of social capital or social networks, m.m. formal search channels, published in recent decades, the overall result of this literature is not really clear cut and has led to quite critical examinations of the concept of social capital as well as of the way it is used in empirical analysis (Mouw, 2003 and 2006). At best, the message gathered from the empirical research is the stylized fact that using informal search methods results in finding a job relatively faster,

but that the results in terms of labour market outcomes (wages, job satisfaction) are rather mixed (Marsden and Gorman, 2001; Ioannides and Datcher Loury, 2004; Bentolila et al., 2010).

Several reasons, like lack of consistency in the way core variables are operationalized and measured, focusing on different groups of labour market participants or neglecting the difference between search and finding channels, can be put forward to account for these mixed results. Probably more importantly, in many cases typologies are used that put within one category or type channels that, to us, seem quite different with respect to how they function in mediating between job seekers en employers. For instance, it happens frequently that the type ‘intermediaries’ contains both temp agencies and the public employment office or that the type ‘social networks’ lumps together ‘families, relatives and friends’, ‘schools’, ‘training programs’ and ‘prior work experience places’. All in all, the points raised above echo the critical remarks voiced already four decades ago by Graham L. Reid (1972: 490-493) when commenting on the lack of consistency in the results of research on job-search methods. In fact, Reid wrote, our data suggest “that the division of the methods into formal and informal categories is not particularly helpful and that the concept of ‘a job-search method’ is much more complicated than this convenient label suggests.”

2.3 Job search strategies of first time education-leavers

From the perspective of this paper, it is also important to note that most analyses of the differential use and effectiveness of search strategies concern adult job seekers or that, when focusing on younger cohorts, no distinction is made between young people looking for a job in general and the more specific case of school leavers or first time labour market entrants. It can be argued, however, that search strategies of the latter category might differ from those of adults because of two important characteristics. First, first time school leavers (or entrants) are unavoidably outsiders without any or with only a limited labour market experience. Apart from the limited knowledge of labour market practices and jobs, this results in much uncertainty about their ‘personal value in the labour market’ as well for themselves as for the potential employer. Contrary to the markets in which most job seekers operate, the market in which first time entrants look for jobs (or get hired), therefore, is likely to have the particular characteristics of an ‘inscrutable’ market (Gambetta, 1994). Second, typical for first time leavers is that all of them arrive on the labour market in a limited span of time, i.e. in the span of a few weeks of months after the end of the academic year. They arrive, one could say, ‘in bulk’. The main consequence is that employers have a broad range of candidates to choose from and that young people, when looking for their first job, are likely to be well aware of the competition of their peers as well as of the possible competition of leavers from an adjoining level of education or field of

study. The combination of both characteristics – ‘inscrutable market’ and ’arriving in bulk’ – may give way to a specific dynamic to searching and finding a job in this particular market.

Detailed empirical analyses of job search strategies of first time education-leavers are scarce. A good illustration is provided by the reports of the CHEERS program, based on international survey on the labour market position of higher education graduates one and five years after graduation. Despite the availability of data on search and finding channels, the chapters on the transition process do not contain an analysis neither of the characteristics of the graduates nor of the de labour market outcomes associated with the use of different search and finding methods. Only descriptive tables with the frequencies of the different channels used in the different countries are provided, showing that which channels higher education graduates use to search for and to find their first job differs greatly by country with replying to advertisements and contacting employers being overall the most used method (Allen and van der Velden, 2007; Schomburg and Teichler, 2006).

Looking into the characteristics related to the use of different channels by Norwegian graduates, Try (2005) found advertisements to be the most used search method. Groups being more exposed to unemployment or lower educational levels used relatively more the public employment service, whereas graduates with parents with a higher educational level or living in neighbourhoods with higer average educational level used relatively more informal methods. Based on data of school-leavers surveys in Ukraine and Croatia, Kogan et al. (2013) found that, contrary to education drop outs, young people with higher educational levels are less likely to use personal contacts. Employment during education does not seem to influence the choice of the search channel an neither do grades once controlled for other educational characteristics. Also, socio-economic background plays only a marginal role. With respect to labour market outcomes, they found different results for both countries. In Ukraine, relying on personal contacts does not lead to finding one’s first job quicker or finding a better or better matched job. In Croatia, on the contrary, young job seekers relying on personal contacts while searching for employment have higher chances of a quick job entry, however, at the price of higher risks of a lower job status and a worse match of their educational level and occupation. The latter finding is in line with Bentolita et al. (2010), showing that, based on American as well as on European data, finding a first job through personal contacts resulted in a wage discount of about 2,5 – 3.5%, even after controlling for long list of personal characteristics, including measures of cognitive ability and of economic and family background. Bentalilo et al. conclude that these empirical results support the hypothesis of a trade-off between quicker job finding and lower wages and is consistent with the theoretical prediction that social contacts can distort workers’ occupational choices and induce mismatch.

Four recent contributions to the literature focus more specifically on the match between education and jobs. Focusing on the difference between monetary and non-monetary outcomes in the early part of the career, Franzen and Hangarter (2006) found that, in Switserland, finding a job via personal contacts does not lead to better monetary results, but appears to lead to better non-monetary outcomes in terms of a better link between education and type of work. Hence, also finding support for the hypothesis of a trade-off. According to Kucel and Byrne (2008), in Ireland, applying for jobs through specialized private employment agencies, replying to employers’ advertisements and even search methods not specifically listed in the questionnaire secure a better education-job match than those found relying on personal contacts. Only finding a job via the public employment service leads to worse results than personal contacts. Blasquez and Mora (2010) found that Spanish graduates finding their first job through university career office were least likely to be overeducated, whereas a greater probability to be overeducated was associated with the use of advertisements, personal networks, public entry examinations and agencies. In line with the finding by Blasquez and Mora (2010), Carroll and Tani (2015) found that, using Australian data, finding a job via a university-based methods was associated with a reduced probability of over-education compared to advertisements, whereas finding a job through contact networks does not offer a benefit in terms of over-education probability relative to advertisements.

Apart from being a relatively better channel for finding better matched jobs, educational institutions seem also to affect labour market outcomes positively in other ways related to the search strategies of young people. Vanoverberghe et al. (2008) also find the speed of the transition to be positively related to search intensity. Interestingly, they also find a small but significant positive effect of the provision of information about job search strategies in schools. Analysing the effects on labour market outcomes of high school leavers in the US, Crawford et al. (1997) shows that the impact of school-provided labour market information may be broader than shortening the transition period. Although which high school a student attends to seems to influence differences in annual earnings, the only characteristics accounting for these differences they can identify are transmitting labour market information to students and substantial work-for-pay experience while in high school translates.

3. Data and methodology

The empirical analysis in this paper uses the so-called SONAR-data – containing data on the transition from school to work for samples from Flemish youngsters born in the years 1976 and 1978. Both cohorts consist of about 3000 individuals, interviewed initially about their transition from school to work at age 23. In both cases, a follow-up survey was conducted at age 26, with respective response rates of 68.3% en 71.2%. The survey consisted of an extensive questioning of the educational and early labour market career, providing detailed information on the individuals’ human capital, the duration of the transition and the characteristics of the first standard job. With respect to this first job, also information was gathered regarding the used search channels and the channel that resulted in a finding a job. At the time of the last survey in which they participated (i.e. at age 23 or age 26), part of the individuals in the overall sample were still student and had never had a standard job. Hence, our working sample is restricted to 5163. These individuals entered the labour market during the period 1994-2004. For more information regarding the data collection process, we refer to SONAR (2003).

3.1 Searching for a job

With respect to searching, respondents were asked whether they searched for a job2 and, if so, to

report all the job search channels they used when trying to find their first standard job. They could choose among a detailed list of methods, provided by the interviewer. To make the analysis manageable, the detailed categories are reduced to seven broad categories: public employment service, interim employment office, advertisements, personal relations, direct approach, the school, and other methods. To answer our first research question, we estimate the determinants of using

each job search channel by means of a multivariate probit model1. In that way, we take into account

that the decision to use various job search methods might be taken simultaneously.

Along with the used job search channels, four more variables related to one’s job search behaviour are analysed. A first variable is the extent to which the school provided job market related information. This information is derived from a survey question with respect to six job-search related activities that

might have taken place during secondary and higher education3. This variable counts the number of

2 683 employed individuals indicated never to have searched for a job.

3 To indicate to which school-provided activities they were exposed to, respondents could tick any of the items in the

following list: (1) learning to write motivation letters and resumes, (2) providing information about the public employment service, (3) providing information about employers, temporary employment agencies and recruitment agencies, (4)

activities a young person was exposed to and is analysed by means of an ordered probit regression. A second variable measures the individuals’ propensity to accept job offers and is based on the following question in the survey at age 23: “Do you totally disagree, rather disagree, rather agree or totally agree, that it is better to take any job instead of staying unemployed”. The third variable indicates when the individual started his job search. In the school-to-work transition literature, it is standard to use the time between the school leaving date and the start of the first job to measure the first search period. Yet, this neglects that some school leavers start their job search much earlier (see Vanoverberghe et al., 2008). We account for this and analyse the determinants of starting job search prior to leaving school. This variable is measured by a dummy variable which is coded one if this is the case. One last variable is an indicator for job search intensity and is measured by the number of job search channels being used (ranging from 0 to 7). These variables are either analysed by (ordered) probit regression or by means of a Poisson model.

For the analysis of the determinants of job search behaviour, we focus on variables that have attracted much attention in the school-to-work transition literature such as gender, ethnicity, human capital and social capital. We measure human capital by means of several variables: level of education (three dummies), whether the individual had repeating years during his educational career (one dummy), self-assessed study results in the final year of secondary education (two dummies), number of months of work experience by means of work placement, whether the school leaver had participated at least one month in a student job (one dummy) and whether he or she had participated in an apprenticeship (one dummy). As indicators for social capital, we use the occupational level of the father (three dummies, with jobless as reference), the educational level of the mother (three dummies), the number of brothers and sisters, living with a partner, membership of a club or organization (one dummy) and leadership in a club or organization (one dummy). As further controls, we include dummies for the region of residence (four dummies), having a child (one dummy), cohort (one dummy), year of labour market entry (ten dummies) and whether the individual left school in June (one dummy).

Different from many other studies in the literature, the observed job search behaviour in this study is not related to a fixed time interval. The questions regarding the used job search channels apply to the full transition period, which differs in length across individuals. This should be controlled for to make a correct assessment of the job search behaviour of individuals with different characteristics. So, the log of the length of the transition period is included as an additional explanatory variable in the

providing information about job advertisements, (5) providing information about job fairs, and (6) providing information about becoming self-employed.

analysis on the (number of) job search channels. This variable is measured as the number of months between the school leaving date and the start of the first job or – if still without job – the date of the last interview. Since job search behaviour is an evident determinant of the length of the transition process, endogeneity problems are likely to be severe. To correct for this, we apply the ‘two-stage conditional maximum likelihood’ procedure (cf. Rivers and Vuong, 1988; Wooldridge, 1997). This procedure estimates the endogenous variable in the first stage. The estimated error term of this regression is then included as additional control variable in the second-stage probit and poisson

equations2. For identification purposes, we include two extra variables as instruments in the first-stage

equation. The first variable is the log of the potential observed length of the transition period. Since not all individuals already entered their first job by the time of their last interview, this variable explains part of the variation in the observed length of the transition period. The second variable is the aforementioned variable that measures the individuals’ propensity to accept job offers. It seems reasonable to assume that this variable is only indirectly related to the use of the various search

channels through its impact on the length of the transition period3.

In addition, the variables measuring the provision of job search related information during education as well as the variable measuring the start of job search are added as explanatory variables for the (number of) job search channels. When analysing of the start of the job search process, we add the provision of job search related information and the propensity to accept jobs as explanatory variables. Finally, in the case of the propensity to accept jobs, only the job search related information variables are added as explanatory factor.

3.2 Finding a job

Individuals were also asked to report through which channel the first job was found. No information is available about the arrival rate of job offers or whether prior to accepting the first registered job other job offers were rejected. In addition to the detailed list of methods used to determinate which job search channels were used, we included two more items: ‘finding a job through employment with a previous employer’ and ‘being contacted by the employer himself’. Hence, we distinguish nine broad categories when considering the successful search channel or finding channel.

To investigate which individual characteristics determine the success of the various job search methods, many studies estimate a multinomial logit or probit model (e.g. Weber and Mahringer, 2008). Yet, this modelling approach does not take into account the duration of the job search or transition period. So, we follow the approach of Addison and Portugal (2002) and estimate cause-specific Cox proportional hazard functions. More cause-specifically, we model the conditional probability of

exiting the joblessness period after leaving school through a particular job finding method.

Additionally, we also report estimates of the unconditional probability to enter into the first job4.

The included explanatory and control variables in these duration models are the same as those in the analysis of the (number of) used job search methods. Two exceptions are the duration of the transition period, which is evidently excluded, and the propensity to accept jobs, which is now included. As we do not condition on the used job search methods, the estimated effects of the various individual characteristics represent their reduced-form effects. These effects consist of direct effects on the job finding rate and of indirect effects through their impact on job search behaviour. To investigate the extent to which search intensity affects job finding rates, we estimate a second specification of the conditional probability to enter into the first job, controlling for the log of the number of search channels. Here also, the two-stage residual inclusion approach is applied to account for possible

endogeneity bias5. Two variables are excluded in this specification to improve identification: the

extent to which the individual received school provided job market related information and whether the individual started her or his job search prior to leaving school. It seems likely that both variables

only influence the transition rate through their impact on job search behaviour6.

3.3 Finding a ‘good’ job

Although in empirical studies ‘wages’ and ‘job satisfaction’ are commonly used as the main indicators for job quality, the literature on school-to-work transitions as well as the literature on job search methods also makes use of several other indicators of job quality. The SONAR-data contain a vast array of possible interesting indicators, like whether the respondent was vertically or horizontally mismatched, whether the first job provided the opportunity to acquire additional skills or whether the job was stressful.

In a first analysis, this paper focuses on the following three outcomes: duration of the first job, occupational status and job satisfaction. In the SONAR-data, job changes are defined to be changes in the employer and/or tasks to be executed. Occupations are coded following the Dutch Standard classification of occupations, which can be translated to the International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status. With respect to job satisfaction, we make use of the following survey question: “During the early phase of your first job, how satisfied were you with your job?”. Respondents were asked to answer on a scale from 1 (very unsatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). The duration of the first job, occupational status and job satisfaction are analyzed by means of Cox proportional hazard regression, OLS, and ordered probit regression, respectively. For each outcome, two specifications are estimated. In a first specification, we include the same explanatory and control variables as when analyzing the

job finding rates. In a second specification, we also include dummies for the job finding channels. In this way, we get an idea of the extent to which the finding channel explains differences in quality regarding the first job across individuals with alternative characteristics.

In a second analysis, given that entering the labour market overeducated or in a job not matching the field of study may signal problems young people eventually experience further on in their career, we focus on so-called educational mismatch as an important indicator of the efficiency of the matching process. We consider four different mismatch indicators. For overeducation (or vertical educational mismatch), we use both an objective and a subjective measure. The former measure is based on a comparison between the educational level of the school leaver and the functional level of the job as defined by the aforementioned Standard classification of occupations standard classification of

Occupations of Statistics Netherlands4. Subjective overeducation is derived from the answer to the

following question ‘Do you have a level of education which is according to your opinion too high, too low or appropriate for the job?’ Field of study mismatch (or horizontal educational mismatch) is measured by the answer to the question ‘Is the content of your job in line with your field of study?’ Respondents were able to answer with ‘Completely’, ‘More or less’ and ‘Not at All’. Finally, we use a ‘full mismatch’ indicator combining objective overeducation and field of study mismatch. Each of these mismatch indicators is analysed by means of binary probit models. The two specifications estimated are the same as those with respect to the other job quality indicators.

4 For more information regarding the measurement of overeducation relying on the SONAR data, we refer to Verhaest and

4. Results

After providing some descriptive results and looking at the effectiveness of the different channels, this section reports on the results of the four analyses conducted.

4.1 Descriptive results and search channel effectiveness

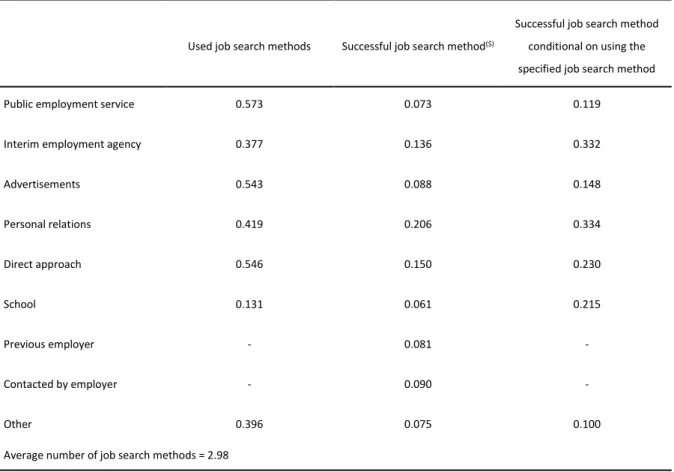

Table 1 reports some descriptive statistics regarding the channels Flemish first time education leavers use to search for (column 1) and find (column 2) their first job. It also provides (column 3) a commonly used measure for the ‘effectiveness’ or ‘penetration rate’ (Reid, 1972) of the different channels, i.e. the proportion of young people finding their job through a particular channel, conditional on having used that channel when searching.

Table 1: Job search methods and their success, descriptive statistics

Used job search methods Successful job search method($)

Successful job search method conditional on using the specified job search method

Public employment service 0.573 0.073 0.119

Interim employment agency 0.377 0.136 0.332

Advertisements 0.543 0.088 0.148 Personal relations 0.419 0.206 0.334 Direct approach 0.546 0.150 0.230 School 0.131 0.061 0.215 Previous employer - 0.081 - Contacted by employer - 0.090 - Other 0.396 0.075 0.100

Average number of job search methods = 2.98

($) 3.9% of the selected sample didn’t manage to find a job by the end of the last survey. Data source: SONAR c76 (23), SONAR c76 (26),

SONAR c78 (23), SONAR c78 (26), own calculations (N = 5163)

search method to find a first job (57.3%), immediately followed by the direct approach (54.6%) and advertisements (54.6%). Also frequently used are personal relations (41.9%) and interim employment agencies (37.7%). Far less commonly used as a search channel when looking for the first job is the school (13.1%). It is evident that most individuals used more than one channel. To find the first job, the average number of channels used was 2.9.

As shown in table 1, personal relations are by far the most successful search channel to find a first job (20.6%). Also quite successful are the direct approach (15.0%) and interim employment agencies (13.6%). The frequencies of the other channels are much lower, never exceeding 10%. Since some search channels are more used than others, we also report their conditional success rate. According to this indicator, personal relations (33.4%), interim employment agencies (33.2%) and the direct approach (23.0%) are, again, found to be the relatively successful ones. The conditional success rates of the public employment service (11.9%) and other methods (10.0%) are much lower. Only the school performs substantially different on the basis of this alternative indicator. Whereas this channel has the lowest overall success rate (6.1%), its conditional success rate (21.5%) is comparable to that of the direct approach.

Note, however, that both the overall and the conditional success rate are ex-post measures and do not correct for the differential use made of them as recruitment channels in different parts of the labour market.

4.2 Job search behaviour

In a first analysis, we look at search behavior in general. More specifically, we explore which characteristics of our first time education leavers impact on four variables indicative of potential differences in search strategy: their choosiness or propensity to accept a job, their exposure to school initiated job search courses, whether they started searching for a job before leaving education and the number of search channels used when looking for their first job. In a second analysis, we look at which characteristics of the young people themselves as well as of their search strategy influence the use of each of the search channels.

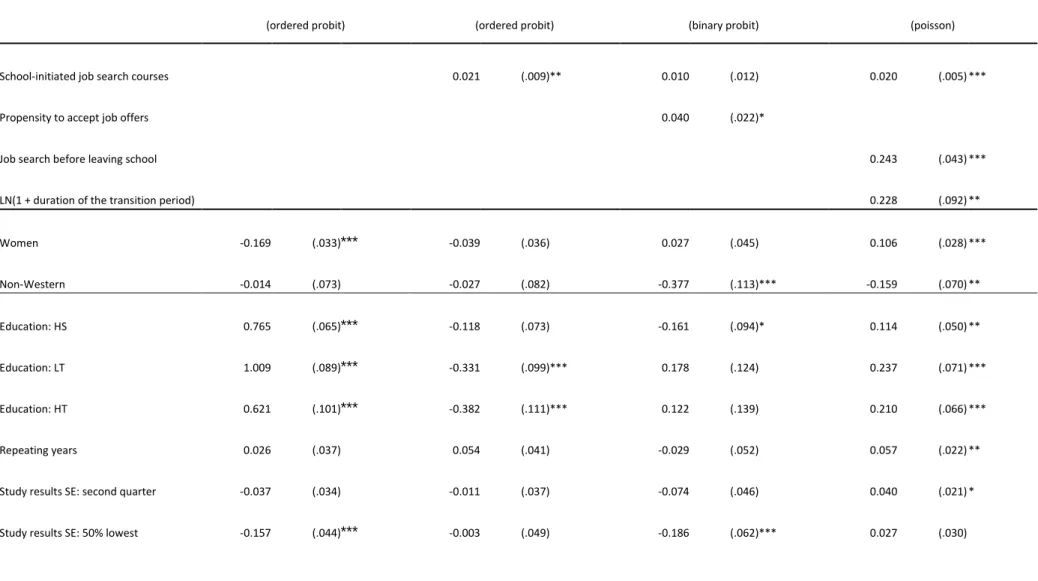

4.2.1 Which characteristics influence search behavior in general?

As shown in Table 2 (last column), having benefitted from school initiated job search courses, starting to search for a job before leaving school and having a longer search period are all three positively related to the number of channels used. With respect to personal characteristics we see that young

women use significantly more but young people with a non-Western background significantly less search channels. Young people having experienced work placement as part of their educational track use significantly less search channels.

Having left education with a tertiary degree has a significant negative effect on the propensity to accept jobs, but a positive effect on the number of search channels used.

Different forms of work experience during the educational career seem to have different effects on different items. Having held student jobs only has a strongly significant positive effect on starting to look early for a first job and has a less strongly significant effect on the number of search channels used, but does not have a significant effect on the propensity to accept jobs. Young people having been involved in apprenticeships have a strongly significant positive effect on starting to look for a first job early, but also on the propensity to accept jobs. Having experienced a work placement significantly influences negatively the number of search channels used.

Table 2: Job search behaviour

Variable Job search courses Propensity to accept job offers Start job search < leaving school Number of used job search channels

(ordered probit) (ordered probit) (binary probit) (poisson)

School-initiated job search courses 0.021 (.009) ** 0.010 (.012) 0.020 (.005) ***

Propensity to accept job offers 0.040 (.022) *

Job search before leaving school 0.243 (.043) ***

LN(1 + duration of the transition period) 0.228 (.092) **

Women -0.169 (.033) *** -0.039 (.036) 0.027 (.045) 0.106 (.028) *** Non-Western -0.014 (.073) -0.027 (.082) -0.377 (.113) *** -0.159 (.070) ** Education: HS 0.765 (.065) *** -0.118 (.073) -0.161 (.094) * 0.114 (.050) ** Education: LT 1.009 (.089) *** -0.331 (.099) *** 0.178 (.124) 0.237 (.071) *** Education: HT 0.621 (.101) *** -0.382 (.111) *** 0.122 (.139) 0.210 (.066) *** Repeating years 0.026 (.037) 0.054 (.041) -0.029 (.052) 0.057 (.022) **

Study results SE: second quarter -0.037 (.034) -0.011 (.037) -0.074 (.046) 0.040 (.021) *

Prior experience: Work placement 0.081 (.019) *** 0.036 (.021) * 0.025 (.026) -0.029 (.012) **

Prior experience: Student job 0.047 (.049) 0.081 (.051) 0.176 (.065) *** 0.066 (.037) *

Prior experience: Apprenticeship -0.001 (.072) 0.235 (.081) *** 0.211 (.100) ** 0.063 (.069)

Education mother: LS -0.061 (.052) -0.040 (.058) -0.010 (.072) -0.018 (.031)

Education mother: HS -0.044 (.050) -0.094 (.055) * -0.068 (.068) -0.013 (.029)

Education mother: TE -0.113 (.057) ** -0.110 (.062) * -0.133 (.078) * -0.026 (.034)

Education mother: Unknown -0.004 (.060) -0.018 (.068) -0.172 (.087) ** -0.044 (.037)

Job level father: elementary or lower 0.052 (.061) 0.003 (.066) 0.062 (.083) 0.060 (.036) *

Job level father: medium 0.085 (.060) 0.031 (.065) -0.036 (.082) -0.007 (.036)

Job level father: higher or scientific 0.047 (.065) -0.006 (.070) -0.108 (.088) -0.007 (.038)

Job level father: unknown 0.105 (.076) 0.029 (.083) -0.078 (.104) -0.043 (.045)

Number of brothers and sisters 0.001 (.012) -0.009 (.013) -0.039 (.017) ** -0.009 (.007)

Member of a club 0.017 (.036) 0.054 (.040) 0.028 (.215) 0.046 (.023) **

Taking responsibility in a club -0.057 (.041) -0.047 (.044) 0.149 (.076) * -0.010 (.025)

Data source: SONAR c76 (23), SONAR c76 (26), SONAR c78 (23), SONAR c78 (26), own calculations; *: p < 0.10, **: p < 0.05, ***: p < 0.01; N = 4363. Also included, but not reported: intercept, residual of first stage-regression for number of used job search methods (models B and C) and dummies for having children (1 dummy), cohabiting with partner (1), region (4), birth year (1), leaving education in June (1) and year of labour market entry (10).

4.2.2 What determines the use of a particular search channel ?

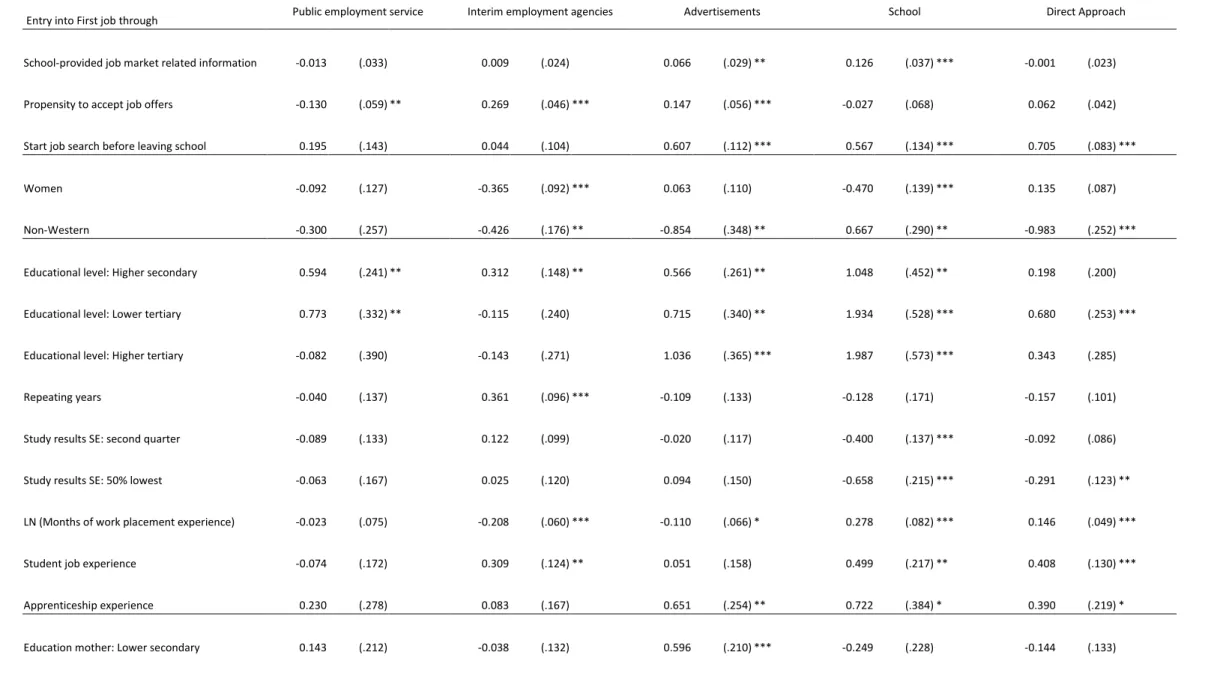

Table 3A presents the results of the analysis of the determinants of the use of the particular search channels.

Of the job-search behavior related variables, starting to look for a job before leaving school has the clearest effect on the use of search channels. Young people started to search early make significantly more use of all the search channels with the exception of the interim employment agencies than young people who started to look only after leaving school. Those who experienced more school-provided labour market information search significantly more via advertisements, the school, personal relations and via other methods. Those young people whose transition takes longer search significantly more via the public employment service, advertisement or the school.

Women make significantly more than man use of the public employment service, interim employment

agencies, advertisement and a direct approach. Young people with a non-western social background make significantly less use of the public employment service and personal relations when looking for a job.

Human capital variables play an important role with respect to which search channel is used or

available. School leavers with a higher educational level look for their first job significantly more via the school, a direct approach, advertisements and significantly less via interim employment agencies. Those having repeated years as well as those with worse educational results use significantly more interim employment agencies and personal relations. Of the indicators of work experience only the amount of time spent in work placement clearly predicts a differential use of search channels. The longer the work placement experience the less one uses the public employment service, interim employment agencies or advertisement and the more one uses personal relations. Job student experience as well as apprenticeships do not seem to make a significant difference in the use of search channels.

With respect to social background no clear pattern of influence can be seen. Regarding social capital, being member of a club or organization predicts using significantly more the school and personal relations as a search channel.

Table 3A: Job search methods use and their determinants, multivariate probit coefficients and standard errors (in parentheses)

Variable Employment service Interim employment

agency Advertisements School Personal Relations Direct approach Others

School-provided job market related inf. 0.005 (.012) 0.017 (.012) 0.035 (.012) *** 0.074 (.016) *** 0.020 (.012) * 0.007 (.012) 0.039 (.012) ***

LN(1 + duration of the transition) 0.470 (.215) ** 0.025 (.215) 0.416 (.210) ** 0.471 (.283) * 0.305 (.211) 0.034 (.210) 0.139 (.214)

Start job search before leaving school 0.214 (.100) ** -0.044 (.100) 0.368 (.098) *** 0.547 (.131) *** 0.336 (.099) *** 0.451 (.098) *** 0.399 (.100) ***

Women 0.275 (.063) *** 0.157 (.064) ** 0.169 (.062) *** 0.114 (.082) -0.021 (.062) 0.214 (.062) *** 0.113 (.063) *

Non-Western -0.346 (.160) ** 0.068 (.158) -0.214 (.157) -0.167 (.216) -0.412 (.159) ** -0.192 (.156) -0.022 (.159)

Educational level: Higher secondary 0.212 (.113) * -0.124 (.112) 0.150 (.111) 0.673 (.191) *** 0.156 (.111) 0.185 (.110) * 0.090 (.114)

Educational level: Lower tertiary 0.243 (.162) -0.487 (.162) *** 0.261 (.159) 1.545 (.248) *** 0.223 (.160) 0.346 (.159) ** 0.444 (.163) ***

Educational level: Higher tertiary 0.001 (.149) -0.472 (.149) *** 0.384 (.146) *** 1.189 (.236) *** 0.098 (.147) 0.398 (.146) *** 0.671 (.150) ***

Repeating years 0.077 (.049) 0.162 (.049) *** -0.001 (.048) -0.004 (.068) 0.141 (.049) *** 0.029 (.048) 0.067 (.050)

Study results SE: 25%-50% best 0.068 (.047) 0.075 (.048) 0.070 (.046) -0.042 (.060) 0.076 (.046) 0.079 (.046) * -0.007 (.047)

Study results SE: 50% lowest 0.072 (.068) 0.134 (.067) ** 0.016 (.066) -0.135 (.091) 0.077 (.066) 0.065 (.066) -0.034 (.068)

LN (Months of work placement exp.) -0.061 (.028) ** -0.137 (.029) *** -0.095 (.028) *** 0.035 (.037) 0.058 (.028) ** 0.023 (.028) -0.090 (.028) ***

Education mother: Lower secondary -0.013 (.069) -0.030 (.068) 0.024 (.068) -0.171 (.094) * -0.019 (.069) -0.030 (.068) 0.038 (.070)

Education mother: Higher secondary -0.012 (.066) -0.092 (.065) 0.008 (.065) -0.133 (.088) 0.091 (.066) -0.081 (.065) 0.071 (.067)

Education mother: Tertiary -0.031 (.076) -0.113 (.076) 0.028 (.075) -0.224 (.101) ** 0.087 (.076) -0.098 (.075) 0.069 (.077)

Education mother: Unknown -0.032 (.085) -0.093 (.083) -0.102 (.082) 0.016 (.113) -0.016 (.083) -0.090 (.083) 0.054 (.085)

Job level father: elementary or lower 0.142 (.080) * 0.030 (.079) 0.106 (.078) 0.174 (.118) 0.196 (.080) ** -0.067 (.079) -0.005 (.081)

Job level father: medium 0.004 (.080) -0.114 (.079) -0.026 (.078) 0.256 (.116) ** 0.128 (.080) -0.150 (.079) * -0.057 (.081)

Job level father: higher or scientific -0.121 (.084) -0.156 (.085) * -0.017 (.084) 0.218 (.120) * 0.155 (.085) * -0.045 (.084) -0.020 (.085)

Job level father: unknown -0.113 (.099) -0.095 (.099) -0.005 (.098) 0.132 (.139) 0.058 (.099) -0.194 (.098) ** -0.108 (.100)

Number of brothers and sisters -0.006 (.016) -0.005 (.015) -0.028 (.015) * 0.015 (.021) -0.008 (.015) -0.006 (.015) -0.020 (.016)

Member of a club or organization 0.047 (.052) 0.008 (.052) 0.052 (.051) 0.156 (.069) ** 0.097 (.051) * -0.031 (.051) 0.071 (.052)

Taking responsibility in a club or organ. 0.018 (.057) -0.066 (.058) -0.068 (.056) 0.032 (.072) -0.004 (.056) 0.085 (.056) -0.057 (.057)

Data source: SONAR c76 (23)., SONAR c76 (26), SONAR c78 (23), SONAR c78 (26), own calculations; *: p < 0.10. **: p < 0.05. ***: p < 0.01; N = 4363