THE PERSPECTIVE OF DUTCH PHARMACISTS ON FALL

PREVENTION AND MULTIDISCIPLINARY

COLLABORATION

Elke De Vriese

A Master dissertation for the study program Master Pharmaceutical Care

THE PERSPECTIVE OF DUTCH PHARMACISTS ON FALL

PREVENTION AND MULTIDISCIPLINARY

COLLABORATION

Elke De Vriese

A Master dissertation for the study program Master Pharmaceutical Care

COPYRIGHT

"The author and the promoters give the authorization to consult and to copy parts of this thesis for personal use only. Any other use is limited by the laws of copyright, especially concerning the obligation to refer to the source whenever results from this thesis are cited."

DATUM

Promotor Author

ABSTRACT

INLEIDING: De wereldpopulatie lijdt onder een vergrijzing. Met de snelgroeiende populatie ouderen neemt ook het aantal valincidenten toe. De rol die de apotheker kan spelen om valincidenten te vermijden is breed. Multidisciplinaire samenwerking tussen zorgverleners, waaronder ook de apotheker, wordt sterk aangeraden om valpreventie aan te pakken. Echter in hoeverre stemt de literatuur overeen met de realiteit?

OBJECTIEVEN: Het doel van de studie was te onderzoeken wat de visie is van de apothekers gesitueerd in Nederland op hun rol in valpreventie. Daarnaast wou de studie ook uitklaren op welke manier apothekers denken over een multidisciplinaire samenwerking om valincidenten tegen te gaan.

METHODE: Tijdens vijf KNMP (Koninklijke Nederlandse Maatschappij ter bevordering der Pharmacie) bijeenkomsten verspreid over Nederland, werd er aan de aanwezige apothekers enquêtes uitgedeeld en gevraagd om mee te doen aan een Mentimeter poll. Data werd verzameld en geanalyseerd in SPSS (versie 25). Beschrijvende data, zoals frequenties en gemiddelden, werden berekend. Ook correlaties werden onderzocht. Open vragen werden geanalyseerd in Excel.

RESULTATEN: Ten eerste, scoorden de apothekers hun vermogen om aandacht te besteden aan valpreventie hoog, in tegenstelling tot hun effectieve bijdrage. Taken voor aan de balie zoals folders uitdelen of proactief vragen naar valincidenten, werden slechts zelden uitgevoerd. Ook de assistenten werden nog onvoldoende betrokken. Valpreventie was te ongekend of nog geen prioriteit in de apotheek. De apothekers hadden nood aan meer multidisciplinaire samenwerking, financiële compensatie en tijd/personeel. Echter gaven de apothekers aan dat ze tijdens medicatiebeoordelingen controleerden of de patiënt het afgelopen jaar gevallen was en of er gevaarlijke medicatie wordt ingenomen.

Ten tweede, had 22.7% van de apothekers al multidisciplinaire afspraken gemaakt. Ze benoemden vaak de huisarts als de belangrijkste zorgverlener. De rolverdeling bevatte wie de leiding heeft, wie signaleert en hoe een zorgplan er moest uitzien.

CONCLUSIE: Uit de resultaten kon geconcludeerd worden dat de apothekers gesitueerd in Nederland graag zouden betrokken worden in valpreventie. Met uitzondering van de medicatie reviews, was valpreventie echter nog niet structureel georganiseerd in de apotheek. Alhoewel ze het allen eens waren dat samenwerking de sleutel is tot betere valpreventie zorg, had slechts een minderheid al multidisciplinaire afspraken gemaakt met andere zorgverleners. Verder onderzoek is nodig om te achterhalen wat hiervoor de oorzaken zouden kunnen zijn en waar ze nood aan hebben om samenwerking te verbeteren.

SUMMARY

INTRODUCTION: The world is suffering from an ageing population. With the fast-growing elderly population, the number of fall incidents is increasing. The role of the pharmacist to avoid fall accidents is extensive. To address fall prevention, multidisciplinary collaboration between healthcare providers including the pharmacist is strongly recommended. However, to what extent does literature correspond to the reality?

OBJECTIVES: The aim of the study was to investigate the vision of Dutch pharmacists on their role in fall prevention. In addition, the study aimed to clarify how pharmacists think about a multidisciplinary collaboration to prevent fall incidents.

METHODS: During five KNMP (Koninklijke Nederlandse Maatschappij ter bevordering der Pharmacie) meetings on fall prevention, surveys were handed out to the participating pharmacists. A Mentimeter poll was also used to gauge their opinions. Data was collected and analysed in a SPSS file. Descriptive data, such as frequencies and means, and correlations were calculated. Open questions were analysed in Excel.

RESULTS: Firstly, the pharmacists scored their ability to contribute to fall prevention high, in contrast with their actual involvement. Task to conduct at the desk, such as handing out folders or proactively ask about fall incidents, were only rarely carried out. Fall prevention was too unknown or wasn’t considered as a priority yet. Also, the pharmacy technicians weren’t sufficiently involved. The pharmacists requested more multidisciplinary collaboration, financial compensation and time/staff. Only during medication reviews, they checked whether the patient had fallen the last year and if dangerous medication was prescribed.

Secondly, 22.7% of the pharmacists had already made multidisciplinary agreements. They often reached out to the physician. The agreements clarified who should be the leader, who should identify high risk patients and how the treatment plan should look like.

CONCLUSION: Overall, the pharmacists situated in the Netherlands considered fall prevention as one of their tasks. Apart from during a medication review, attention to fall prevention was not structurally embedded. Although they all agreed that collaboration is the key to a better fall prevention care, only a minority had already made multidisciplinary agreements. Future research is needed to investigate what causes this lack of collaboration and what needs to be done to improve it.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First of all, I would like to show my gratitude to my supervisors Daphne Philbert and Ellen Koster for sharing their experience and knowledge. This assignment couldn’t be completed without your exceptional effort and advice. I would also like to thank you for your encouraging words which guided me through this process.

Also, I should not forget to thank Marle Gemmeke for her advice and for allowing me the opportunity to contribute to her research project.

Next, I would like to thank my colleague student Eline A. Rodijk. Besides offering a listening ear and support, she explained valuable Dutch traditions to me.

Furthermore, I would like to show my appreciation to my family and friends for their constant source of inspiration and endless patience with me during these unpredictable times. Especially, I would like to thank my parents for supporting me to go on Erasmus (although briefly) and for making it feasible.

I would also like to express my gratitude to Prof. Boussery and Prof. Bouvy for enabling this experience.

Finally, I’m grateful to the members of the KNMP for making it possible to highlight the importance of our research during their meetings. I would like to thank them for their warmly welcome and helping hand.

PREAMBULE

Het doel van deze Master thesis was om te onderzoeken hoe apothekers staan tegenover samenwerking met andere zorgverleners op vlak van valpreventie. Uit enquêtes die werden verdeeld onder apothekers aanwezig op vijf verschillende KNMP-meetings, viel het op dat weinigen al multidisciplinaire afspraken hadden gemaakt. Nochtans wordt dit in de literatuur sterk aangeraden.

De bedoeling was om interviews met apothekers af te nemen om zo te kunnen achterhalen wat de voornaamste redenen zijn voor een gebrek aan collaboratie. Hiervoor werd een interviewhandleiding opgesteld. Echter, in afwachting van de goedkeuring van de Institutional Review Board voor een interview-onderzoek brak het coronavirus uit in Europa. Aangezien de apothekers tijdens deze pandemie extra belast werden, volgde de beslissing om de interviews uit te stellen. De focus werd dan verlegd naar het verder uitdiepen van de resultaten van de enquêtes en de Mentimeter poll. Deze poll van 9 stellingen werd door het FARM-OP researchteam tijdens hun presentatie op de KNMP-meeting gebruikt. Daarnaast werden de doelstellingen iets ruimer genomen. Naast een kijk op samenwerking, werd de algemene visie van de apothekers op valpreventie ook meer belicht. Zodoende diende deze onderzoekstage meer als een inleidende en ruimere kijk op het thema valpreventie.

In het hoofdstuk methode wordt nog aangegeven hoe de opbouw, uitvoering en korte analyse van de interviews zou verlopen zijn. In de appendix kan ook de oorspronkelijke handleiding van het interview teruggevonden worden.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1. ISSUE OF FALLING... 1

1.1.1. Ageing of the world’s population ... 1

1.1.2. Incidence of falling ... 1

1.1.3. Consequences of a fall ... 2

1.2. RISK FACTORS ... 3

1.2.1. Biological factors ... 3

1.2.2. Behavioural factors ... 4

1.2.3. Environment related factors ... 4

1.2.4. Medication effects ... 4

1.3. FRIDS ... 5

1.4. INTERVENTIONS TO REDUCE FALL RISK... 6

1.5. ROLE OF THE PHARMACIST IN FALL PREVENTION... 7

1.5.1. Implementation of fall prevention in the pharmacy ... 7

1.5.2. Education of the patient ... 7

1.5.3. Medication review ... 8

1.5.4. Home-based medication review... 8

1.5.5. Education of the physicians ... 8

1.5.6. Follow-up after discharge ... 9

1.6. MULTIDISCIPLINARY FALL PREVENTION APPROACH ... 9

1.7. REASON FOR THIS STUDY ... 10

2. OBJECTIVES ... 11 3. METHODS... 12 3.1. STUDY DESIGN ... 12 3.2. PARTICIPANTS ... 12 3.3. DATA COLLECTION ... 12 3.3.1. Mentimeter poll ... 12 3.3.2. Surveys ... 13 3.3.3. Interviews ... 13 3.4. DATA ANALYSIS ... 14 4. RESULTS ... 15 4.1. MENTIMETER POLL ... 15 4.1.1. Study population ... 15

4.1.2. Pharmacist’s vision on their role in fall prevention ... 15

4.2. SURVEYS ... 16

4.2.1. Study population ... 16

4.2.2. Tasks for the pharmacists... 17

4.2.3. Pharmacist’s vision on fall prevention tasks ... 18

4.2.4. Tasks for the pharmacy technician ... 19

4.2.5. Pharmacist’s vision on collaboration ... 20

4.2.6. The future ... 21

5. DISCUSSION ... 23

5.1. GENERAL DISCUSSION ... 23

5.2. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS... 25

5.3. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CLINICAL PRACTICE AND FUTURE RESEARCH ... 26

5.3.1. Clinical practice ... 26 5.3.2. Future research ... 27 6. CONCLUSION ... 28 7. REFERENCES ... 29 8. APPENDIX ... 32 8.1. FRIDS ... 32

8.2. STUDIES ON PHARMACISTS’ ROLE IN FALL PREVENTION ... 33

8.3. MENTIMETER POLL STATEMENTS ... 34

8.4. THE FARM-OP SURVEY IN DUTCH ... 34

8.5. INTERVIEW QUESTIONNAIRE ... 38

8.5.1. Intro ... 38

8.5.2. Informatie/deprescribing valgevaarlijke geneesmiddelen ... 38

8.5.3. Samenwerking ... 38

8.5.4. Aanvullende opmerkingen ... 39

8.5.5. Afsluiting ... 39

8.6. RESULTS ... 40

8.6.1. Proportion tables ‘During medication review I pay attention to fall prevention.’ ... 40

8.6.2. Topics for during medication review ... 44

8.6.3. Tasks for the pharmacy technician ... 44

LIST OF ABBREVATIONS ANOVA: ANalysis Of VAriances

ApIOS: Apotheker in Opleiding tot Openbaar Apotheker Specialist EU: Eerste Uitgifte

FARM-OP: FAlls-Related Medication use in Older Patients FOMM Study: Four Or More Medicines Study

FRID: Fall Risk Increased Drug FTO: FarmacoTherapeutisch Overleg

KNMP: Koninklijke Nederlandse Maatschappij ter bevordering der Pharmacie MDO: MultiDisciplinair Overleg

POH: Praktijk Ondersteuner Huisartsen SEH: SpoedEisende Hulp

SPSS: Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

START: Screening Tool to Alert doctors to Right Treatment STOPP: Screening Tool of Older Person’s Prescriptions TU: Tweede Uitgifte

1

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. ISSUE OF FALLING

1.1.1. Ageing of the world’s population

The world’s population is ageing (see Figure 1.1). People are living to older age mainly due to medical developments and improvements within the healthcare sector. The prognosis is that worldwide by 2050, 1 out of 6 people will be over 65 (16%), coming from 1 out of 11 in 2019 (9%).(1) The community is rapidly expanding with older people who are expected and/or have a preference to live at home. Most of them suffer from chronic diseases requiring complex healthcare and multiple drugs which put them sometimes even more in danger. The ageing of the population puts massive pressure on nearly all sectors of the society, including healthcare and social security/welfare amongst others.(1)(2)

1.1.2. Incidence of falling

Older people are more susceptible to falling, resulting in injuries of which they potentially never fully recover. Worldwide approximately 28-35% of people aged 65 or higher fall each year. For people over 70, the percentage of fall occurrences is even higher: 32-42%. People living in nursing homes fall more often than those living at home.(2)

According to a review of Veiligheid.nl, 34% of all the people in the Netherlands aged 65 or higher fall at least once a year. In 2018, 108 000 people were hospitalised following a fall accident at home. The incidence of SEH visits after a fall accident is illustrated in Figure 1.2. That same year, 4 396 elderly people died as a result of a fall. This accounts for 89% of all fatal accidents among the elderly. It’s expected is that by 2050, the number of hospital admissions due to injuries after a fall in the Netherlands will increase by more than 47% (160 000).(3) The same tendency can be seen in Belgium. Incidence reviews show that 24 to 40% of people over 65 living independently fall at least once a year, and 21 to 45% of them repeatedly.(4)

Figure 1.1 The Dutch population pyramid per 1000 citizens of 1953, 2009 and 2050. References: AOW economielokaal.nl

2

1.1.3. Consequences of a fall

It’s clear that the ageing population along with the increasing number of falls create a major healthcare challenge. The financial pressure on both the patient and society is extensive. In the Netherlands, the medical costs in 2018 of falls for people aged >65 treated in the emergency department and/or admitted to the hospital, was estimated at 960 million euros.(3)

Furthermore, the consequences of a fall for the person itself are not to be taken lightly. First, there are the physical complications. The top three most common injuries are hip fractures (17%), light brain damage (11%) and wrist fractures (8%).(3) Hip fractures are typical for women. Men mostly suffer from a head injury due to the fact that they fall more often from a certain height (for example when climbing a ladder). These injuries have a direct impact on the daily life. Moreover, they can cause premature death. The Netherlands reported in 2018, 14 deaths per 10 000 citizens of 65 or older.(3) In Belgium, it is demonstrated that the mortality risk in the first three months after a fall resulting in a hip fracture for a woman or man of >65 is respectively 5 or 8 times higher than estimated. Not only during those three months, but also the coming years the health situation of the patient may deteriorate faster due to the increased fragility caused by a fall.(4)

Along with the physical impact, people who have experienced a fall can also suffer emotionally and psychologically. It is reported that a fall results in fear and loss of confidence. They start to avoid certain activities and isolate themselves. Therefore, they become less mobile and have difficulties to live independently as such ending up in an inevitable negative spiral.(3)

Figure 1.2 Incidence of emergency unit visits in the Netherlands after a private fall accident in 2018. References: Letsels. Cijfers en Context. SEH-bezoeken. Volksgezondheidenzorg.info

3

1.2. RISK FACTORS

To understand which initiatives to prevent fall incidents are effective, it is important to know why the elderly are so vulnerable. Very often, it’s not just one factor but a combination which causes them to fall. It’s also very difficult to determine which factor has the upper hand.

1.2.1. Biological factors

As people get older, they undergo many different biological changes that can contribute to an increased risk. For example, the vessels get stiffer and the heart wall thickens. This has a great impact on the regulation of the blood pressure. That’s why many older patients suffer from orthostatic hypotension resulting in dizziness when standing up too fast. It can also occur postprandial or after urinating. The emerging dizziness puts them in danger of falling.(5)

Next, the elderly suffer from mobility and balance impairments due the loss of muscle strength and/or joint malfunctions that come with ageing. Moreover, ageing of the feet resulting into complications such as ingrown nails,callosity, ulcers or blisters amplifies mobility disorders.(4)(6) The elderly also struggle to manage their postural control which is essential to maintain balance during static and dynamic activities in line with changes in tasks and environment.(4) The control relies on the proper functioning of three systems, that is knowing to decrease with ageing, namely the proprioceptive sensory, vestibular and visual system. Consequently, dizziness symptoms increase especially due to the loss of vision.(7) This includes changes in depth perception, contrast sensitivity and development of disorders such as cataract, glaucoma and diabetes retinopathy.(4)

Also, the cognitive functioning of a patient has an impact on the regulation of balance. Due to conditions such as dementia, depression or delirium, they are not capable to correctly evaluate activities or situations and are oblivious to the risks. Such mental illnesses can result in reduced attention to the surroundings, decreased physical activity with further deterioration of the muscles and the use of psychotropic medication that are considered dangerous for older adults.(4)(6)

Furthermore, changes in the sleeping pattern can enhance the risk of falling. The sleep structure of the elderly alters because their biological clock changes due to ageing. They have difficulties to fall asleep and are easily interrupted by surrounding noises. Pain, nocturia and stress which is common among the elderly, can also amplify sleeping problems. In addition, sleep apnoea is quite frequent in the older population. As a result, they become sleepy during the day and have a hard time to concentrate, which puts them in danger of falling. Despite the fact that it’s a natural development, mental conditions or diseases as well as certain drugs can play a contributing factor.(4)(8)

4

Finally, diseases such as Parkinson, arthritis, stroke, diabetes and so on add an extra burden through disease-specific impairments. To give an example, osteoporosis puts the patient at greater risk of fractures after a fall due to the loss of bone density. Spine fractures due to these density impairments consequently alternates the patient’s posture and possibly worsens balance regulation.(4)(6)(7)

1.2.2. Behavioural factors

Some older people show risk behaviour. This includes rushing, inattentiveness during walks or repeatedly performing actions such as standing up, sitting down or bending over. On the other hand, inactivity also poses a risk. As mentioned before, the muscles need to be supported to ensure balance and mobility. Besides activity, an optimal nutrition state is crucial for muscle strength and fall prevention. Especially the concentration of vitamin D and calcium needs to be in control because of its role in bone and kidney function. Finally, fear of falling puts the patient at danger, whether they have fallen before or not. As mentioned before, they will restrict or avoid exercise, isolate themselves and this may eventually wear them out.(4)(6)(7)

1.2.3. Environment related factors

Next to clinical factors, living conditions are at least as important. Along with others,loose carpets, uneven or slippery floors, pets, insufficient lighting and lack of stair railings are considered high risk factors. Besides the home setting, the elderly should be aware of dangerous situations in the environment too. For example, poorly maintained walking pavements and lighting facilities result in more fall incidents by the elderly.(4)(6)(7)

1.2.4. Medication effects

Due to co-morbidities, the elderly require many different types of medication. Despite the sometimes appropriate need for all these pills, polypharmacy is often the cause of complications as fall incidents.(7) Drugs can significantly influence each other leading to alarming interactions. An example is the enhancement of side effects such as dizziness that leads to fall incidents. Changes in pharmacodynamic and kinetic characteristics due to ageing, for instance loss of body fat mass or the amount of blood proteins, can also result in even more unexpected adverse effects. Next, due to the complexity of some medication schedules, the elderly can get confused of the correct intake and consequently intoxicate themselves or the opposite. As well as the use of different medication, being prescribed by multiple physicians and consulting different pharmacists increases the risk of falling.(4)(6)(7) Which drugs are considered of high risk will be highlighted in the next chapter.

All of the above illustrates that older people are running a higher risk due to many different factors. It is only reasonable that the prevention must be covered by many different healthcare providers, one of which is the pharmacist. The most relevant factor that can be modified by the pharmacist are the FRIDs.

5

1.3. FRIDS

Medication that is identified as dangerous, is categorised as a FRID, a fall risk–increasing drug. It’s important to point out that an all-inclusive list has not yet been developed and results of studies aren’t always consistent. For example, the use of statins was associated with a protective effect, even though a major adverse effect is loss of muscle strength and balance.(9) Even more, some studies did not find statistically significant correlation between certain drugs and increased number of falls. Although data is limited, most of them concluded that caution is still recommended. To get better results, studies should design a clear definition of the outcome falling according to Seppala LJ et al. Not only the pharmacological subgroups, but also the influence of duration and dosage should be investigated.(10)

Table 8.1 (see Appendix 8.1) contains an overview of the drugs that are associated with a higher risk by researchers. Although it’s common knowledge that the following drugs are alarming, a large proportion of the older population takes them especially after a previous fall. According to a systematic review the prevalence ranged from 65 to 93%.(11) Drugs are classified as FRID if they cause dizziness, sedation, concentration problems, cognitive or mobility impairments, ataxia or cardiovascular side effects such as bradycardia or orthostatic hypotension. Table 1.1 present the most common side effects causing the elderly to fall and some examples of the responsible drugs.(4)(7)(12)

Table 1.1 Dangerous side effects with examples of potential high-risk drugs a

SIDE EFFECT MEDICATION

Agitation Antidepressants, caffeine, neuroleptics, stimulants

Arrhythmias Antiarrhythmics

Bradycardia Beta blockers

Cognitive impairment Benzodiazepines, narcotics, neuroleptics, anticholinergic drugs

Dizziness Antidepressant, antiepileptics, benzodiazepines, narcotics, neuroleptics Extrapyramidal Antipsychotics

Orthostatic hypotension Antihypertensive drugs, antipsychotics Gait abnormalities Antidepressants, neuroleptics

Postural disturbances Antiepileptics, benzodiazepines, neuroleptics

Sedation Antidepressants, antiepileptics, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, narcotics, neuroleptics

Syncope Beta blockers, nitrates, vasodilators

Visual disturbances Anticholinergic drugs, antiepileptics, neuroleptics

6

1.4. INTERVENTIONS TO REDUCE FALL RISK

Before one should consider fall prevention interventions, it is necessary to determine if the patient is indeed at risk. Therefore, guidelines suggest an easy risk screening tool every healthcare provider can initiate. The patient should be asked these two questions:

1. Have you fallen in the last 12 months?

2. Do you have trouble with moving, walking or keeping your balance?

Depending on the answers, the patient should or should not be included in a fall risk analysis. During this analysis, the patient is asked more detailed questions including each risk factor listed above.(6) Finally, preventive strategies are to be implemented to improve the quality of life. A recap of these interventions can be found in Table 1.2. As shown before, falling is a multifactorial problem and for each individual different interventions are beneficial. Moreover, different combinations of the intervention listed below were investigated all resulting in a positive effect on the number of fall occurrences.(18)(19)(20)(21)

Table 1.2 The fall prevention interventions a

INTERVENTION EXAMPLES RISK FACTOR

Physical activity Multicomponent exercises,

Thai Chi

Muscle strength, mobility, flexibility, endurance

Annual visit optician Glasses, contact lenses Loss of vision

Walking aids

Sticks, tripods, quadruped, walking frames with or without wheels, rollators or

crutches

Mobility and balance Vitamin D supplementation Promoting outdoor activities Optimal nutrition state

Medication reviews Especially FRIDs Optimal medication usage

and polypharmacy Living condition modifications

by occupational therapist

Remove or change loose floor mats, paint the edges of steps, clean frequently,

install grab bars and stair rails and improve lighting where needed

Environmental factors

Optimal footwear Anti-slip Ageing of the feet

Brain teasers Meditation Sleep problems, cognitive

functioning, fear of falling Behavioural awareness Not standing up to fast, walking Risk behaviour, dizziness

7

It has been shown that the implementation of fall prevention interventions has to deal with a couple of barriers. First, researchers addressed practical aspects including cost, accessibility and time. The lack of financial reimbursement and the additional paperwork prevented successful implementation of fall preventive counselling. Secondly, the perception of the community was an influencing factor. To give an example: walking aids were used to portray some sort of status, but now they are related to a sign of age and frailty. That is why many elderlies felt judged. Moreover, some were embarrassed to participate in exercises such as Tai Chi. Some even considered the advice of a healthcare provider as insulting.(22) These barriers could be an explanation as to why the approach of the physician towards patients over 65 years showing signs of dizziness, was still too passive. According to Stam et al, the most common interventions were wait-and-see and advising. The results also showed that referrals were rare and describing FRIDs was deficient.(23)

1.5. ROLE OF THE PHARMACIST IN FALL PREVENTION

1.5.1. Implementation of fall prevention in the pharmacy

To promote fall prevention, the pharmacy is the ideal setting. Because of the low social barrier, the pharmacist is in an ideal position to screen, assist and follow-up patients with a higher risk of falling. Not only are they accessible, they are widely distributed in the community, have ideal opening hours and interact frequently with the same patients. Similar healthcare programs have already been successfully implemented via the pharmacy, for example spreading awareness on alcohol abuse and smoking.(24) Australian researchers organised a workshop on fall prevention for pharmacists providing them with tools including brochures, a fall prevention DVD and Dossett Administration Aid or lessons on how to do a Med check (quick medication review at the desk). The workshop successfully encouraged the pharmacists to initiate fall prevention in their pharmacy.(25)

1.5.2. Education of the patient

Consequently, the pharmacist should be able to inform, advise, motivate and refer older patients. They should initiate a conversation with the patient, not only concerning their medication use or therapy compliance, but also life in general. This includes questions like how they are walking, if they are still active, what they eat on daily basis, if their pain level is acceptable, how many times they are awake during the night etc. Once sufficient amount of information is collected from these conversations, the pharmacist can start with educating the patient on how to minimize their individual risks. For example, they can suggest physical therapy, home hazard assessments or gait and balance training if they show signs of mobility impairments.(24)(26)(27)

8

1.5.3. Medication review

As mentioned before, numerous drugs have been suspected of contributing to fall incidents. Logically, the best intervention is not to prescribe a FRID in the first place. A helpful tool, Medication Appropriateness Index, was developed to assist the physician in making the right choice of medication for the older patient. Secondly, the START/STOPP criteria is gaining popularity amongst the healthcare providers. Besides the importance of prescribing appropriately, the medicines that are already used have to be checked frequently, especially by the pharmacist during medication reviews. They have the expertise to assess drug efficacy and adverse effects caused by duplicates or drug interactions. So, during medication reviews the healthcare provider should determine if certain FRIDs are used and if it’s possible to minimize them. If feasible, an immediate cease is desirable. On the other hand, tapering is often the more proper way to avoid adverse effects.(28)(29) This is for example the case for benzodiazepines.(7) As reported by Gillespie et al., a withdrawal of psychotropic drugs led to a reduction in number of fall accidents.(20) Besides the success of reducing fall incidents, the withdrawal of FRIDs achieved a significant cost saving according to Van Der Velde et al.(30) However, if stopping is not possible, choosing a better alternative or dosage reduction is also suitable.(18) In this way drug regimens can appropriately be simplified during one face-to-face consultation.(31)

1.5.4. Home-based medication review

Some studies investigated if a home-based visit would be productive to manage the patient’s disease and medication use.(32) Besides the cost, it took a lot of effort and time of the pharmacist to schedule the home visit. Also, the safety of the pharmacist was difficult to guarantee. On the other hand, a home visit provided a holistic image of the patient’s medication use, including prescriptions, OTC or alternative medication use. Unnecessary or expired medicines were removed on advice of the pharmacist. They also checked the storage conditions and made recommendations. In addition the whole family was included in the discussion and the pharmacist had a better view on the living conditions, which led to a better understanding of the patient’s mindset.(33)

1.5.5. Education of the physicians

The pharmacist has the unique skill to engage a discussion with the prescribing physicians. They can function as a guide to better therapeutic choices. As well as the skills, they have the expertise to educate other healthcare professionals regarding the appropriate usage of medication.(26)(34) The ideal setting for this is a FTO (‘Farmacotherapeutisch Overleg’), which is a collaborative meeting. In local or regional groups the pharmacists and physicians come to an agreement regarding the prescription and dispensing of medicines so that the patients are optimally advised.(35)

9

1.5.6. Follow-up after discharge

Finally, the pharmacist also has a role to play once a fall has occurred. Falls among the elderly lead to an admission in a hospital every 5 minutes. For a lot of them it doesn’t end with one visit, so an in-dept follow-up by the pharmacist could be a valuable intervention. Pharmacist in charge of guiding patients discharged from the hospital after a fall, should share their impressions with the physician. He or she is then capable to identify the risk and make adjustments if needed.(26)(36)

All these different kind of options for the pharmacist to address fall prevention are derived from results or recommendations of investigations. In Table 8.2 a recap of examples of these studies can be found with their original objective and results (see Appendix 8.2 Table 8.2). Just like many other studies, they have their limitations which needs to be kept in mind.

1.6. MULTIDISCIPLINARY FALL PREVENTION APPROACH

As previous chapters illustrated, falling is a multifactorial condition underlining the need for collaboration between the different healthcare providers involved in the care for older patients. Even though the pharmacist can provide critical information on medication, especially FRIDs, they should not be alone in this. An optician should check the vision annually, the physiotherapist can recommend physical activities, the dietitian can develop an optimal diet with sufficient vitamins and calcium intake, the occupational therapist can implement home hazard modifications and so on. Research concluded that a multifactorial fall risk assessment by an interdisciplinary team is indeed proven to be effective.(20)(37) The results of another study showed that not only was there a direct improvement in quality of life of the patient, the members of the team also stated that it was easier to set up a healthcare plan for further care. Nevertheless, they indicated that it took a lot of time and commitment. They concluded that conducting a multidisciplinary healthcare team requires a clear definition of the roles and responsibilities.(38)

Some ambitious researchers even designed inventive ways to improve communication. For example, through an electronic medication record, information of fall incidents was collected and shared between the pharmacist and physician. They were capable to alert each other through the device and the message included an evidence-based guidance to alter the drug regimen efficiently. The physicians stated that their care was altered due to the fact that the messages were personalised.(39)A Texas study designed a protocol to improve collaboration on secondary stroke and fall prevention through the use of an iPad. By applying telephone-guided interaction, the caregivers don’t have to meet physically with each other and the patient, but would still be able to provide adequate healthcare.(40)

10

To assist the pharmacist in multidisciplinary collaboration, the KNMP, the Royal Dutch Pharmacists Association, designed a module.(41) The goal of this module is to optimise communication and collaboration between the primary care providers. The guideline starts off with forming a core team with members of diverse backgrounds and assigning a coordinator. Preparations must be made, including an inventory of which fall prevention programs and organisations are already present in the region. Subsequently, concrete goals must be set and a plan on how they want to achieve them. It is important that every member knows their role and responsibility. The different tasks that need to be distributed are amongst others identifying high risk patients, selecting the main practitioner, setting up and supervising a treatment plan. In order to eventually implement the plan, the members must decide whether there is a need for further training and if the essential resources such as time and money are guaranteed. At last, in addition to the correct implementation, there has to be an efficient way to evaluate the results and maintain the successes.(41)

1.7. REASON FOR THIS STUDY

As research has shown, the ageing of the population along with the increasing number of falls is a worldwide problem. Therefore, the need for implementation of preventive methods are necessary to provide proper and affordable healthcare. Many have dedicated their time to investigate the effectiveness of current interventions or suggested other ways to improve healthcare regarding fall prevention. A lot of organisations have also developed tools based on scientific proof, for example the simple risk analysis by Veiligheid.nl or the module for collaboration by KNMP. But have they achieved their goal?

The reason for this study is to gain insight into how pharmacists think about fall prevention and the services they could provide according to studies and organisations. In the literature, there was a lack of interest in the opinion of the pharmacists themselves. To improve guidelines and modules and enhance the motivation of the pharmacists, it’s essential to communicate what’s proven to be effective and what isn’t working, to know what they already do and for which aspects they need more guidance. In addition, collaboration seems to be crucial for efficient healthcare such as fall prevention, but how does the pharmacists feel about this?

11

2. OBJECTIVES

The first aim of this study was to investigate what Dutch pharmacists think of their role in fall prevention. To provide this information the following questions were aimed to be answered.

• What tasks can the pharmacists conduct? • How frequently are these tasks carried out? • How do they feel regarding these tasks?

• What do they think of the role for the pharmacy technician? • What do they need in order to do more on fall prevention? • How do they envision the future?

Secondly, the purpose of this study was to determine if pharmacists collaborate with other healthcare providers to prevent falls among the elderly. This also included more information on what the difficulties are with regards to collaboration in (primary) care and what the pharmacists think would be helpful to enhance collaboration in a fall prevention program.

12

3. METHODS

3.1. STUDY DESIGN

A mixed methods study was conducted, consisting of an online Mentimeter poll used during a presentation for pharmacists, a survey and a (phone) interview with community pharmacists carried out by two students. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) from the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences of Utrecht University.

3.2. PARTICIPANTS

The Mentimeter statements and surveys were filled out by participants (pharmacists) during five different KNMP gatherings that took place in Dordrecht, Leende, Bunnik, Zwolle and Oostzaan about fall prevention. Each gathering was attended by circa 100 pharmacists. The aim of these meetings was to highlight the importance of fall prevention among the pharmacists and discuss examples of interventions to prevent fall incidents.

On the last page of the survey, the pharmacists were asked to participate in an interview. Unfortunately, the moment permission was granted to start with the interviews, the corona virus broke out in Europe. So, the planned interviews could not be carried out. The participating pharmacists would have received an e-mail with additional information about the study and with a proposal to make an appointment for the interview. If they hadn’t answered on the e-mail within a week, they would have been contacted by phone. The aim was to conduct around 10 interviews per student, so 20 interviews in total.

3.3. DATA COLLECTION 3.3.1. Mentimeter poll

During the meetings, the pharmacists in the audience had to score 9 different statements on a scale from 1 to 10 by using their phone. The topics included if the pharmacists think they should play a role in fall prevention and if they do, how frequently they pay attention to fall prevention during and outside of medication reviews, if they have enough knowledge on the FRIDs, how to recognize high risk patients and if they have enough time to focus on this topic fall prevention (see Appendix 8.3). The scores were immediately presented live to be able to interact with the attendants and seek an explanation. At the end of the Mentimeter presentation, the pharmacists were asked if their answers could be used for further data analysis (informed consent). Every participant who answered negatively, was later deleted from the dataset in the SPSS file.

13

3.3.2. Surveys

A survey, written in Dutch, was set up (see Appendix 8.4). Multiple times during the KNMP gatherings, the pharmacists were encouraged to fill them out. Furthermore, an online version of the survey was also brought to the attention via the UPPER (Utrecht Pharmacy Practice network for Education and Research) newsletter of February 2020 and on the website of KNMP. The survey questions were used to collect information on the vision of the pharmacists on fall prevention by the use of ranking statements, open sections for clarification, open and multiple-choice questions. The ranking statement used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree or 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, 5 = always). The topics included the carried-out services on fall prevention, the indication of these actions, which tools they need, if they had worked together with other healthcare providers, what they think of a FTO or a guideline to manage medication regimen and how they see the role of the pharmacist and pharmacy technician. To ensure the privacy of the pharmacists who filled out the surveys, personal information asked at last page of the survey was separated from the rest of the survey and stored as informed consent form at a different location.After a period of 4 weeks of data collection (start of the gatherings plus one week after the last gathering), all information was clustered in a SPSS-file (version 25) to be analysed.

3.3.3. Interviews

Based on the results of the surveys, a more specified interview with open-ended questions would have been set up. However, due to the corona virus pandemic it wasn’t possible to conduct these interviews in the foreseen timeframe. The following procedure would have been the chosen one. The two research students prepared a topic list but would have been free to change the sequence and/or the questions themselves. The semi-structured interview guide consisted of two main topics, meaning the tools they need to help them with deprescribing FRIDs investigated by another student and the multidisciplinary collaboration on fall prevention (see Appendix 8.5). Before the start of data collection, the students would have rehearsed the interviews to clarify the content and length. Depending on the preferences of the participant, they would have been interviewed face-to-face or by phone. Before the start of each interview, participants would have been made aware of the study procedures. The conversations would have been audiotaped. The interviewer would have stated that the tapes would only be consulted by members of the research team. After the study was completed, the audiotapes would have been deleted. Participants would have been given the opportunity to receive a copy of the transcript so they could adjust or provide clarification of the text fragments. Verbal consent would have been obtained. Every interview should have been completed during a timeframe of 20-30 minutes.

14

3.4. DATA ANALYSIS

All collected data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25). Descriptive data of the Mentimeter poll were calculated, including means with standard deviations.As well as for the Mentimeter poll, descriptive data was calculated for the surveys, including frequencies and means with standard deviations. Associations between male and female, between different age classes, between different groups of years of experience and between owner and partner pharmacist were analysed using Pearson Chi Square test. Open questions were briefly read through to determine overarching themes. Every answer was then investigated to determine which themes it included, so multiple options were possible.

The interviews would have been transcribed verbatim and coded by the use of NVivo qualitative data analysis software (version 12). Before the analysis, a coding tree was developed based on information gathered during the meetings. A first thorough reading of the transcripts would have been useful to optimise the coding tree even more.

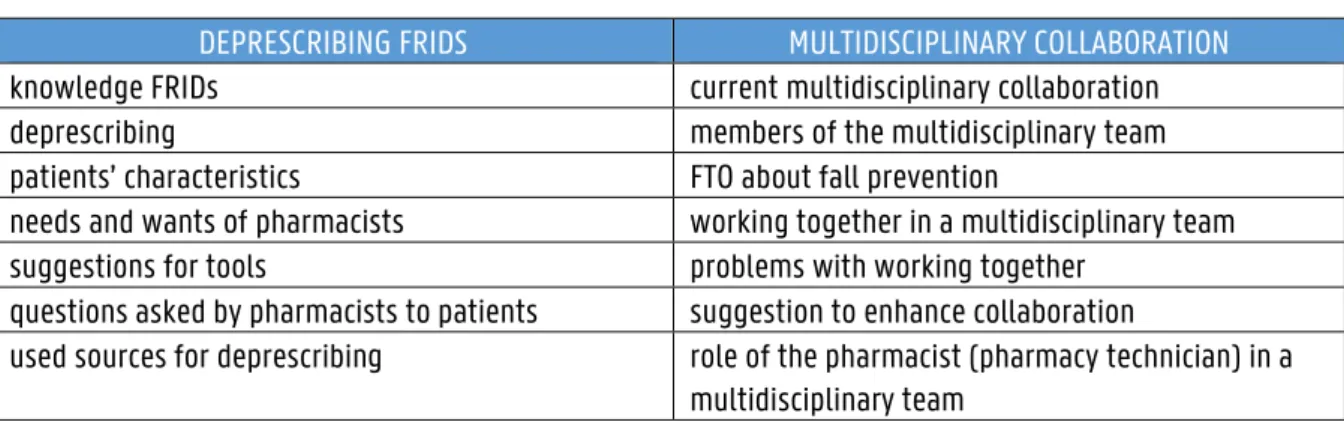

Table 3.1 The coding tree for Nvivo

The first three transcripts would have been coded by both students. They would have been free to add more codes (open-coding). Then, the students would have discussed the discrepancies and developed a newly updated coding tree. They would have included a third researcher to obtain maximum objectivity. Once approval would have been received, the students would have coded the first three transcripts again and the remaining transcripts by the use of this advanced coding tree. Later the results of all the transcripts would have been shared between the students.

The transcripts would have been divided into two groups. The first one would have included all the pharmacists who had worked together with other healthcare providers, the other group would have consisted of pharmacists that mentioned they haven’t worked in a team. Same opinions would have been clustered and used to identify overarching themes. Different opinions would have been used to compare answers on these overarching themes. Descriptive quotes and a word cloud would have been used as illustration.

DEPRESCRIBING FRIDS MULTIDISCIPLINARY COLLABORATION

knowledge FRIDs current multidisciplinary collaboration

deprescribing members of the multidisciplinary team

patients’ characteristics FTO about fall prevention

needs and wants of pharmacists working together in a multidisciplinary team

suggestions for tools problems with working together

questions asked by pharmacists to patients suggestion to enhance collaboration

used sources for deprescribing role of the pharmacist (pharmacy technician) in a multidisciplinary team

15

4. RESULTS

4.1. MENTIMETER POLL 4.1.1. Study population

The Mentimeter poll was filled out by 391 pharmacists during the presentation. Out of this group, 81.3% (n = 318) indicated that their answers could be used for data analysis.

4.1.2. Pharmacist’s vision on their role in fall prevention

The first two statements of the Mentimeter poll ‘The community pharmacist can play a role in fall prevention.’ (n = 295) and ‘At the moment I contribute to fall prevention.’ (n = 293) had an average score of respectively 7.99 (SD 2.37) and 3.62 (SD 2.84). For statement one, 88.5% scored equal or higher than 6, but only 26.3% did the same for statement two.

The third and fourth statement ‘During a medication review I pay attention to fall prevention.’ (n = 288) and ‘Besides medication reviews I pay attention to fall prevention.’ (n = 293) had an average score of respectively 7.33 (SD 3.04) and 2.86 (SD 2.68). For statement three, 77.8% scored equal or higher than 6, but only 16.7% did the same for statement four. The scores are gathered in a boxplot (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 Boxplot of statement 1-4 of the Mentimeter poll regarding pharmacist’s vision on their role in fall prevention.

16

4.2. SURVEYS

4.2.1. Study population

The survey was filled out by 203 pharmacists who attended the KNMP gatherings and by 2 pharmacists who used the online version. The main characteristics are described in Table 4.1 including age, gender, years of experience and type of pharmacist. Five pharmacists didn’t fill out the characteristics. The average age was 44 and more female pharmacists filled out the survey (65.0%). The average years of experience was 18.6. The pharmacists were mostly owners of a pharmacy or/and community pharmacist specialist, which indicates that they succeeded a 3-year specialisation as community pharmacist funded by the KNMP.

Table 4.1 Characteristics of the pharmacists

Characteristics Mean (SD) %(n)

Age (n = 200) 44 (11)

Gender (n = 200) Female 65.0% (130)

Years of experience Mean 18.6 (10.5)

≤10 years 29.7% (59)

11-20 years 29.2% (58)

21-30 years 27.1% (54)

≥31 years 14.1% (28)

Type (n = 195) Owner pharmacist 69.7% (136)

Owner partner pharmacist 20.0% (39)

Community pharmacist specialist a

61.5% (120)

ApIOS b 2.6% (5)

Community pharmacist 3.6% (7)

a finished a 3-year specialisation as community pharmacist funded by the KNMP b still following a 3-year specialisation as community pharmacist funded by the KNMP

17

4.2.2. Tasks for the pharmacists

In order of highest proportions, 60.5% (n = 124) of the pharmacists stated to never hand out folders, 35.8% (n = 73) to sometimes give lifestyle advice, 41.2% (n = 84) to rarely start a conservation about the risk factors, 41.7% (n = 85) to rarely proactively ask if the patient falls, 37.7% (n = 77) to often give suggestions for medication adjustments during reviews, 40.0% (n = 82) to sometimes refer a patient to another healthcare provider and 46.6% (n = 95) to always check if the patient have previously suffered from a fall during a medication review (see Figure 4.2). The most frequently asked questions during these medication reviews were ‘Fallen in the last 12 months?’ (62.1%, n = 72) and ‘Do you use high risk medication?’ (52.6%, n = 61) (see Appendix 8.6 Figure 8.1). Of the participating pharmacists, 52.4% (n = 99/189) would have performed these tasks if another healthcare provider pointed out that a patient sometimes falls.

5.9% 8.3% 3.9% 23.0% 25.0% 9.3% 60.5% 8.3% 20.5% 5.4% 41.7% 41.2% 21.6% 21.0% 15.2% 40.0% 25.0% 28.9% 29.9% 35.8% 10.7% 24.0% 23.4% 37.7% 4.4% 3.9% 27.0% 7.3% 46.6% 7.8% 27.9% 2.0% 6.4% 0.5% 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

During medication reviews, I check if patients have fallen before.(n = 204)

I refer a patient to another healthcare provider(general practitioner, physical therapist) if I know that a patient

sometimes falls.(n = 205)

I give suggestions for adjustments during medication reviews if I know that a patient sometimes falls.(n =

204)

I proactively ask patients if they ever fall (at the desk or during a phone call).(n = 204)

I start a conversation with the patients and investigate together the risk factors.(n = 204)

I give (lifestyle) advice if I know that patients sometimes fall.(n = 204)

I hand out folders or other patient information if I know that patients sometimes fall.(n = 205)

Percentage (%)

How frequently do you perform the following tasks?

Never Rarely Sometimes Often Always

18

Significantly more female pharmacists than male pharmacists always checked if a patient has fallen before during a medication review (57.4% vs 30.0%, p < 0.001). Significantly more younger pharmacists always checked during a medication review than the older generation (mean age never vs always 51 vs 42 years, p = 0.006). Significantly more owner pharmacists always checked during a medication review than partner pharmacists (51.5% vs 41.7%, p = 0.003). No significant differences were seen between different years of experience (mean of experience in years never vs always 24.2 vs 16.8 years). The proportions can be found in the appendix (see Appendix 8.6 table 3-6).

4.2.3. Pharmacist’s vision on fall prevention tasks

In order of highest proportions, 42.5% (n = 79) of the pharmacists stated to disagree with having difficulties to start a conversation with the patient about the increased risk of medicines, 37.6% (n = 70) to feel neutral on recognizing patients with a high risk and 39.5% (n = 73) to strongly agree with giving educational material to the patientsif available (see Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3 The answers to the question ‘To what extent do you agree with the following statements about fall prevention?’ 1.6% 3.8% 19.9% 4.9% 25.3% 42.5% 18.9% 37.6% 25.8% 35.1% 26.3% 9.7% 39.5% 7.0% 2.2% 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

If I had educational materials about fall prevention for patients, I would pass this on to the patients. (n = 185) I have difficulties recognizing patients with a high risk

of falling. (n = 186)

I have difficulties to start a conversation with the patient about the increased risk of falling the

medicines can cause. (n = 186)

Percentage (%)

To what extent do you agree with the following statements about fall

prevention?

19

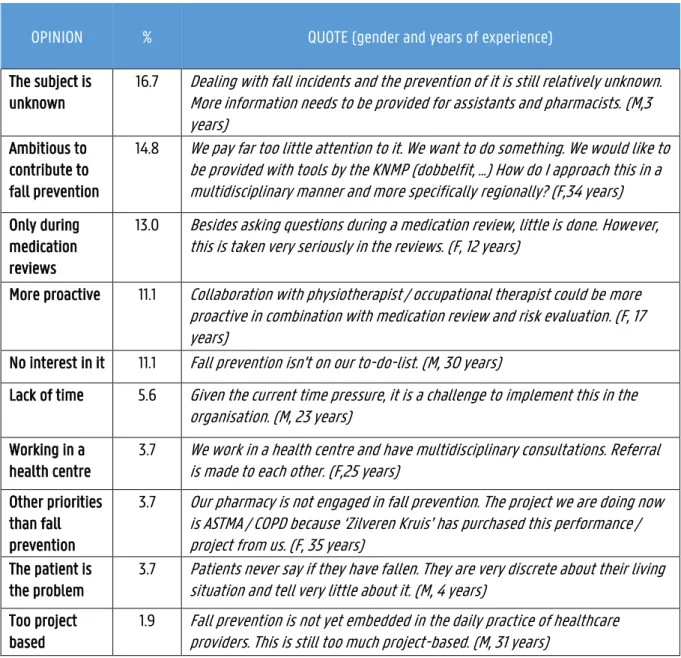

The following quotes give an illustrative insight into how the pharmacists think of their tasks regarding fall prevention. In order of highest proportions, 16.7% (n = 9) of the answers included a statement on the lack of knowledge and 14.8% (n = 8) of the answers showed that the pharmacists are ambitious (see Table 4.2).

Table 4.2 Illustrative opinions of the pharmacists on fall prevention (n = 54)

OPINION % QUOTE (gender and years of experience)

The subject is unknown

16.7 Dealing with fall incidents and the prevention of it is still relatively unknown. More information needs to be provided for assistants and pharmacists. (M,3 years)

Ambitious to contribute to fall prevention

14.8 We pay far too little attention to it. We want to do something. We would like to be provided with tools by the KNMP (dobbelfit, ...) How do I approach this in a multidisciplinary manner and more specifically regionally? (F,34 years) Only during

medication reviews

13.0 Besides asking questions during a medication review, little is done. However, this is taken very seriously in the reviews. (F, 12 years)

More proactive 11.1 Collaboration with physiotherapist / occupational therapist could be more proactive in combination with medication review and risk evaluation. (F, 17 years)

No interest in it 11.1 Fall prevention isn't on our to-do-list. (M, 30 years)

Lack of time 5.6 Given the current time pressure, it is a challenge to implement this in the organisation. (M, 23 years)

Working in a health centre

3.7 We work in a health centre and have multidisciplinary consultations. Referral is made to each other. (F,25 years)

Other priorities than fall prevention

3.7 Our pharmacy is not engaged in fall prevention. The project we are doing now is ASTMA / COPD because ‘Zilveren Kruis’ has purchased this performance / project from us. (F, 35 years)

The patient is the problem

3.7 Patients never say if they have fallen. They are very discrete about their living situation and tell very little about it. (M, 4 years)

Too project based

1.9 Fall prevention is not yet embedded in the daily practice of healthcare providers. This is still too much project-based. (M, 31 years)

4.2.4. Tasks for the pharmacy technician

The majority of the pharmacists had not specified if they would pass on tasks to their pharmacy technician (56.8%, n = 104/183). The pharmacists who did, expected a screening (76.6%, n = 53) and an advising role (24.7%, n = 19) from their pharmacy technician. Four of them specifically mentioned the 2 risk questions set up by Veiligheid.nl (see Appendix 8.6 Figure 8.2).

20

4.2.5. Pharmacist’s vision on collaboration

The majority of the pharmacists had not collaborated with other healthcare providers (77.2%, n = 146/189) in terms of fall prevention. The pharmacists who did, specified with whom they collaborated. The answers in decreasing order were the physician (88.4%, n = 38), the physiotherapist (41.9%, n = 18), the home care taker (39.5%, n = 17), the geriatric specialist (23.3%, n = 10), the dietician (9.3%, n = 4), the geriatrician (4.7%, n = 2) and other (16.3%, n = 7). These other included occupational therapist (n = 2), psychologist (n = 1), social team (n = 3), optician (n = 1), POH geriatrician (n = 1) and district nurse (n = 1).

There were no significant differences between yes- and no-responders to the questions if they made multidisciplinary agreements with regards to gender, age, years of experience and type of pharmacist. The proportion can be found in the appendix (see Appendix 8.6 Table 7-10).

The following quotes give a good insight into how the pharmacists work together. In order of highest proportions, the topics on which they came to an agreement were 37.5% (n = 9) on setting up a plan to help high risk patients and 33.3% (n = 8) on who has to signal for a high-risk patient (see Table 4.3).

Table 4.3 Illustrative opinions of the pharmacists on multidisciplinary agreements (n = 24)

AGREEMENT % QUOTE (gender and years of experience)

How should a treatment plan look like?

37.5 If someone is identified with an increased risk of falling, they will be referred to a physiotherapist or occupational therapist to figure out what they need. The person is then referred to the right person. (F, 5 years) Who is responsible to

signal/screen for a high-risk patient?

33.3 The home care identifies whether patients are at risk of falling and reports this to us or the physician. In the event of a fall, the physician will consider whether it could be valuable to do a review. (F, 10 years) What are the agreements

regarding medication use?

29.2 Standardly add calcium/vit D for the elderly. Discontinue statins if patient is > 80 years. (M, 20 years)

Who is in charge of the treatment?

20.8 The physicians are in charge, everyone refers to them. Physician hands out tasks/consults other healthcare providers. (F, 5 years)

In what setting do the health care providers meet?

16.7 MDO organized x times a year. (M, 7 years)

What's the role of the pharmacist?

12.5 Physio informs the physician and pharmacist when a fall occurs. Pharmacist conducts a polypharmacy conversation. (M, 8 years)

21

In regard of multidisciplinary collaboration, the survey gauges the pharmacists’ thoughts on FTO. In order of highest proportions, 36.2% (n = 67) stated to think neutral of a FTO and 44.6% (n = 82) to agree with the need of more material (see Figure 4.4).

4.2.6. The future

To enhance their involvement in fall prevention, 190 pharmacists answered in increasing order to be in need of an service training, a protocol to support the withdrawal of dangerous drugs, information material, in-service training for the pharmacy technician, more time, compensation and multidisciplinary collaboration (see Figure 4.5). Multiple options were possible. In order of highest proportions, 57.0% (n = 106/186) of the pharmacists stated to agree with paying attention to fall prevention on a daily basis.

The following quotes give a good insight into what they are looking for in order to do more regarding fall prevention. The gender and years of experience are mentioned.

Pharmacist 1: “Collaboration is essential, consultation costs time / money that currently is not facilitated. Digital information material for patients.” (M, 30 years)

Pharmacist 2: “Feedback from hospitals / doctors if the patient has fallen. Due to lack of time and resources, it’s sometimes not possible to do so. A fee can compensate for this.” (F, 8 years)

Pharmacist 3: “Cooperation of general practitioners is a major problem in our neighbourhood. They do not see prevention as an important task (prevention = 0th line, not primary care).” (M, 1 year)

Pharmacist 4: “As healthcare provider, we wait and see who takes the initiative. Locally physiotherapists pick it up.” (M, 31 years)

Figure 4.4 The answers to the question ‘What do the pharmacists think of a FTO?’

7.0%, 13 16.2%, 30 36.2%, 67 30.3%, 56 10.3%, 19 7.1%, 13 8.7%, 16 20.7%, 38 44.6%, 82 19.0%, 35 0 20 40 60 80 100

Strongly disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly agree

Am

oun

t (%,

n

)

What do the pharmacists think of a FTO?

A FTO on falling has high priority in my / our pharmacy? (n = 185) I need material for a FTO on falling. (n = 184)

22

Figure 4.5 The answers to the question ‘What do you need to do more on fall prevention.’

36.8% (n = 70) 51.1% (n = 97) 58.9% (n = 112) 63.2% (n = 120) 67.4% (n = 128) 72.1% (n = 137) 73.7% (n = 140) 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

In-service training/more knowledge A protocol / guideline to withdraw of dangerous drugs

Information material for patients In-service training for assistants More time (more staff) Compensation of health insurance companies

More multidisciplinary collaboration

Percent of Cases (%)

What do you need to do more on fall prevention?

a(n = 190)

23

5. DISCUSSION

5.1. GENERAL DISCUSSION

This study aimed to investigate the vision of pharmacists in the Netherlands on fall prevention and multidisciplinary collaboration. Overall, pharmacists in this study considered fall prevention as one of their tasks, but they also mentioned difficulties to execute such services. Only during medication reviews they paid attention to fall prevention and the impact of medication on it. Although they all agreed that collaboration is the key to a better fall prevention program for the elderly, only a minority made multidisciplinary agreements.

The results showed that pharmacists scored their interest in fall prevention very high. So, the pharmacists included in this study supported the need for more involvement of their profession in fall prevention. According to other studies, pharmacists saw their roles evolve even further. They saw themselves as the ideal person to assess risk factors and provide recommendations regarding medication and life habits. Especially, they mentioned that they should manage vitamin D and calcium supplementation.(24)

However, the results of this study showed that performing fall prevention activities in the Netherlands has only just started and the pharmacists’ actual participation is low. Rarely did the pharmacists engage a conversation or proactively asked about experiencing a fall or risk factors. Also, many indicated that they never handed out folders, yet they would like to if they knew where to find (free) information material. Similar input came out of an earlier study in Quebec showing that the pharmacists, though interested in changing their role, only occasionally paid attention to fall prevention and usually not longer than 10 minutes per patient.(24)

A possible explanation why the current engagement of the pharmacists in this study in fall prevention was minimal, was the fact that pharmacists were unfamiliar with the subject and needed more guidance to structurally embed fall prevention care. Comparable to other studies, there was a shortage of time, tools, education, coordination and financial reimbursement.(24) Others also reasoned there was a lack of confidence and adequate counselling space to provide such public health services.(42)

Furthermore, results of this study showed that fall prevention wasn’t considered a priority in contrast with other projects, such as asthma treatment. It was mostly addressed project-wise rather than structurally or proactively embedded, for example by organizing a fall prevention week. Other studies reasoned similarly that other healthcare programs, such as cardiovascular prevention, diabetes counselling or smoking cessation were more essential than fall prevention.(24)

24

On a positive note, during medication reviews, the pharmacists in this study always checked for a fall history and recommended adjustments for the medication regimen. They disagreed with having difficulties to start a conversation with the patient regarding the possible high risk of the prescribed medication. Literature showed that pharmacists as expert of the drugs are crucial in medication management to prevent falls due to their high priority recommendations.(31)(43) Despite the clear efforts of the pharmacists the results are still mediocre regarding the effectiveness of this kind of pharmaceutical care to prevent fall incidents. Only a small decrease in discontinuing high risk drugs or fall incidents were reported.(28)(29) This minimal success was also not in proportion to the time and effort.(44)

Some pharmacists of this study mentioned patients were hesitated to share their fall history and physicians were difficult to motivate. In other studies, one of the reasons why only a few older patients effectively had their medication adjusted was due to the reluctance of both the patient and the prescriber. The physicians had difficulties to handle multimorbidity and predicting the consequences for their sometimes fragile patients.(21)(44) The reluctance of the prescriber or patient and the time-consuming job of reviewing medication regimen, could be an additional explanation for the disappointing outcome of performed activities in this study. This shows the importance of open communication and enhancing collaboration between pharmacist and physician to make the effort of medication review count. A potential solution to this could be that the pharmacist, together with the physician, screen the patients for whom a medication review would be warranted or who would be open towards adjustments.(44)

Despite the relatively neutral interest in a FTO, pharmacists in this study checked a multidisciplinary collaboration as their biggest need to fully manage fall prevention. This is in line with other studies that concluded collaboration is beneficial due to providing a holistic image of the patient and uplifting the motivation of the parties involved.(45) However, up to this day, only a minority of the pharmacists of this study had already made multidisciplinary agreements. Plus, they would only occasionally refer a patient to another healthcare provider or perform fall prevention tasks if someone else pointed out that a patient sometimes falls. Several pharmacists mentioned the lack of motivation of the physicians andthat everyone seemed to be waiting until someone else takes the initiative to start a collaboration. This underlines again the need for better cooperation between different healthcare professions. A study conducted in Quebec also came to the same conclusion and showed that there is a lack of knowledge of external existing organisations and guidance to whom the pharmacists could refer to.(24)

25

The pharmacists of this study who did come to multidisciplinary agreements with other healthcare providers, primarily selected the physician, the physiotherapist and/or the home care nurse as team members. A similar top three to perform fall prevention services was chosen by the regional public healthcare officers of the Quebec study: the physician, pharmacist and nurse.(24) So, it’s seemed that those professions should be the focus and the initiators to start organising a multidisciplinary fall prevention program in the setting of primary care.

The following key success factors were identified looking at the agreements the few pharmacists of this study made with other healthcare providers: good communication, a clear role division and treatment plan. For example, the physician had the lead while the physiotherapist was accountable for the counselling of the patient. Some indicated that a MDO or FTO was the ideal setting to come together and discuss the progress. The pharmacists who were active in a health centre reasoned that collaboration was easy due to close encounter with the attendant healthcare providers. These results were in line with the conclusion of Bollen et al that there are three pillars for the cooperation to be successful, namely a regular communication, a clear role division and a close co-location.(46)

5.2. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

A major strength of this study was the relatively high response rate, 205 pharmacists to be exact. Because the survey was handed out during five different KNMP-meetings located around the country, a widespread population was approached.

Another strength was the open sections included in the survey. The pharmacists were free to explain their opinions in their own words in contrast with the ranking statements and multiple-choice questions. Because it was a written survey by which they were assured it would be analysed anonymously, no one could steer the answers of the pharmacists or influence their opinion compared to a verbal interview. Moreover, they were less inclined to give socially acceptable answers.

A possible limitation of the study is the bias in the selection of the pharmacists. The sample was drawn out of a group of pharmacists who voluntarily attended a gathering about fall prevention. Furthermore, two types of attendants could be seen. On one hand there were the more experienced pharmacists and on the other hand the ones with little to no experience who came to gain a first impression. Perhaps the more experienced pharmacists filled out these surveys, because of their familiarity with the subject. This could overestimate the results. However, due to the fact that still both types were present, the representation of the pharmacists’ population could be better than expected.